![]()

THE WINNING OF

INDEPENDENCE, 1777-1783

![]() he year 1777 was perhaps the most critical for the British. The issue, not necessarily understood clearly in London or America at the time, was whether the British could score such success in putting down the American revolt that the French would not dare enter

the war openly to aid the American rebels. Yet it was in this critical year that British plans were most confused and British operations most disjointed. The British campaign of 1777 therefore provides one of the most striking object lessons in American military history of the dangers of divided command.

he year 1777 was perhaps the most critical for the British. The issue, not necessarily understood clearly in London or America at the time, was whether the British could score such success in putting down the American revolt that the French would not dare enter

the war openly to aid the American rebels. Yet it was in this critical year that British plans were most confused and British operations most disjointed. The British campaign of 1777 therefore provides one of the most striking object lessons in American military history of the dangers of divided command.

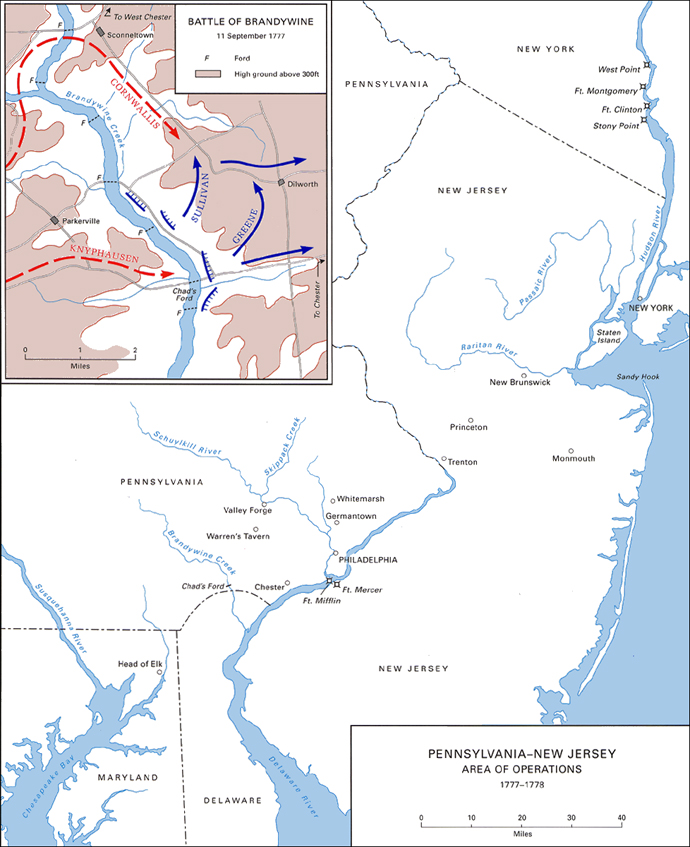

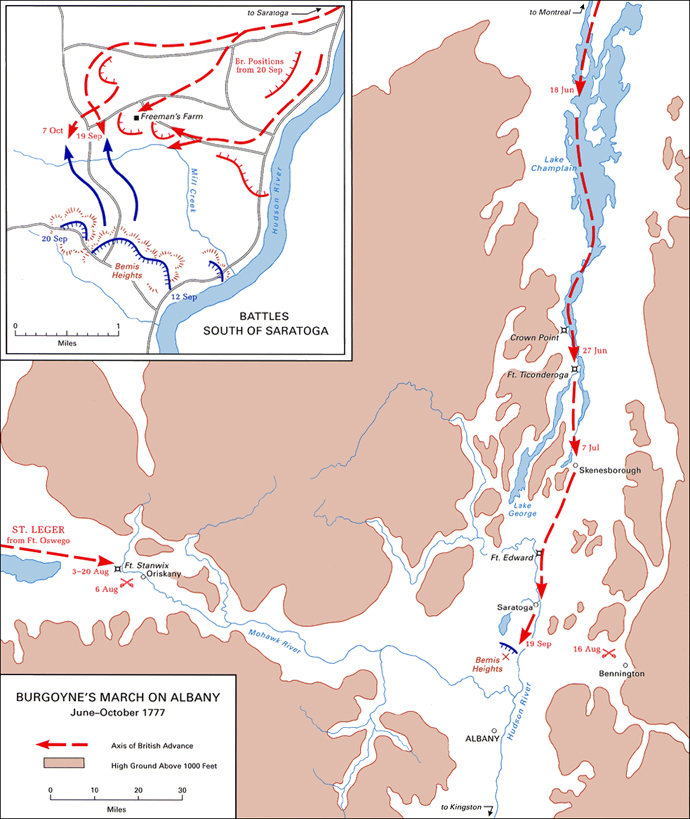

With secure bases at New York and Newport, Sir William Howe had a chance to get the early start in 1777 that had been denied him the previous year. His first plan, advanced on November 30, 1776, was probably the most comprehensive put forward by any British commander during the war. He proposed to maintain a small force of about 8,000 to contain Washington in New Jersey and 7,000 to garrison New York, while sending one column of 10,000 from Newport into New England and another column of 10,000 from New York up the Hudson to form a junction with a British force moving down from Canada. On the assumption that these moves would be successful by autumn, he would next capture Philadelphia, the rebel capital, then make the southern provinces the "objects of the winter." For this plan, Howe requested 35,000 men, 15,000 more effective troops than he had remaining at the end of the 1776 campaign. Lord George Germain, the Secretary of State responsible for strategic planning for the American theater, could promise Howe only 8,000 replacements. Even before receiving this news, but evidently influenced by Trenton and Princeton, Howe refined his plan and proposed to devote his main effort in 1777