![]()

THE CIVIL WAR, 1863

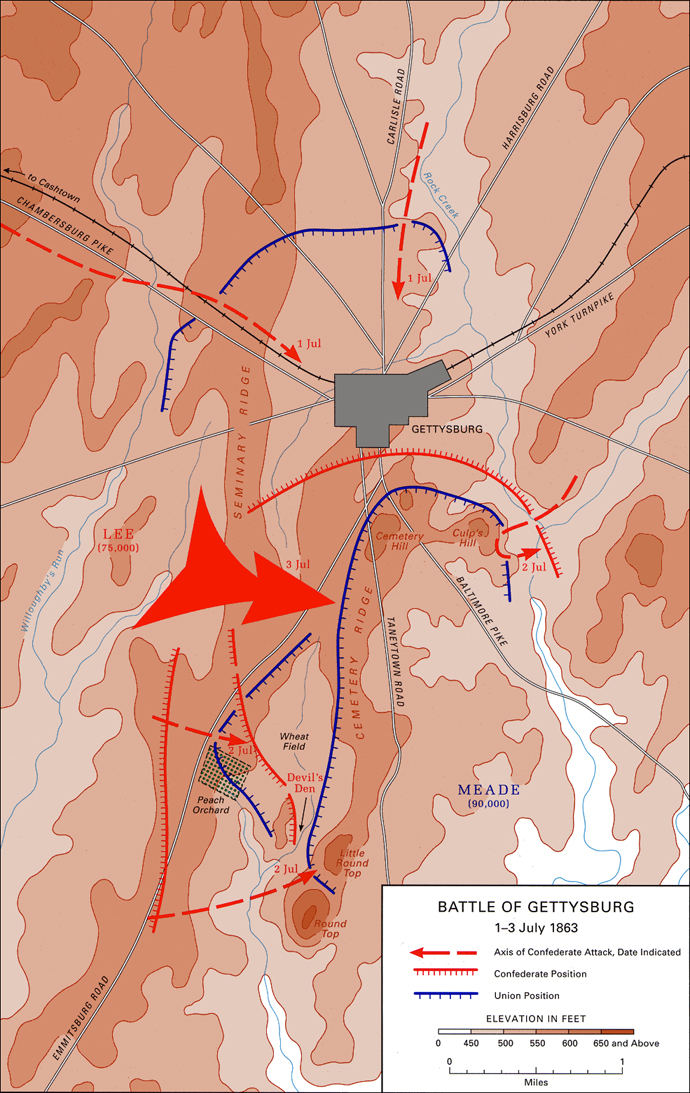

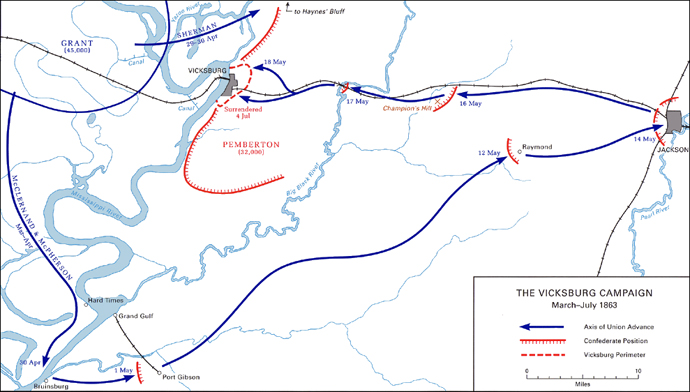

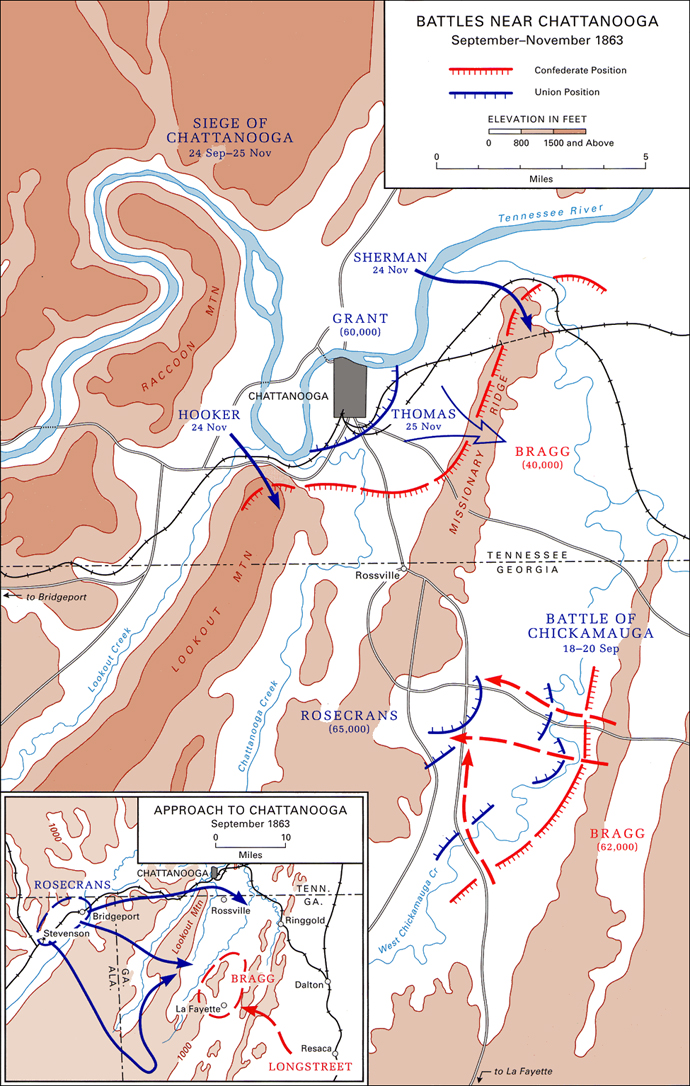

t the beginning of 1863 the Confederacy seemed to have a fair chance of ultimate success on the battlefield. But during this year three great campaigns would shape the outcome of the war in favor of the North. One would see the final solution to the control of the Mississippi River. A second, concurrent with the first, would break the back of any Confederate hopes for success by invasion of the North and recognition abroad. The third, slow and uncertain in its first phases, would result eventually in Union control of the strategic gateway to the South Atlantic region of the Confederacy—the last great stronghold of secession and the area in which the aims of military operations were as much focused on destroying the economic infrastructure of the South as defeating main-force rebel units.

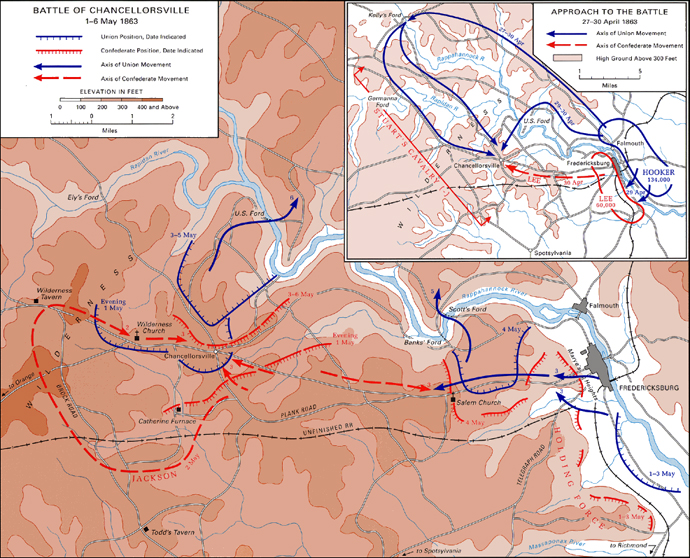

The East: Hooker Crosses the Rappahannock

The course of the war in the east in 1863 was dramatic and in many ways decisive. After the battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862, Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside’s Army of the Potomac went into winter quarters on the north bank of the Rappahannock, while the main body of General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia held Fredericksburg and guarded the railway line to Richmond. During January of the new year, Burnside’s subordinates intrigued against him and went out of channels to present their grievances to Congress and President Abraham Lincoln. When Burnside heard of this development, he asked that either he or most of the subordinate general officers be removed. The President, not pleased with either Burnside’s string of failures or his ultimatum, accepted the first alternative and on January 25, 1863, replaced Burnside with Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker. The new commander had won the sobriquet Fighting Joe from overly enthusiastic journalists because of his reputation as a hard-fighting division and corps commander. He was highly favored in Washington, but in appointing him the President wrote a fatherly letter in which he warned the general against rashness and overambi-