Department of the Army Historical Summary: FY 1976

VII.

Organization and Management

Changes resulting from the Army and Army staff reorganizations of 1973 and 1974 continued throughout 1976. Financial austerity forced further reorganizations and internal realignments to reduce the size of headquarters staffs and combat support operations. Politically sensitive issues were also responsible for organization and management changes.

The dramatic increase in the Army’s sale of arms to oil-rich countries in the politically and militarily volatile Middle East caused increasing congressional criticism. General Weyand visited the area to investigate the problem personally. On his return he ordered an intensive study, which led to the creation of a permanent Coordinator for Army Security Assistance under the Vice Chief of Staff on 8 October 1975. The Chief of Staff assigned to this position Maj. Gen. John A. Hoefling, formerly director of International Logistics in the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Logistics.

Replacing the Army’s piecemeal management of international security assistance, the new office became the center of a complex, sophisticated, and well-articulated network of relations with relevant agencies inside and outside the Army and the Department of Defense. General Hoefling worked directly with the Defense Security Assistance Agency, the Under Secretary of the Army, the Assistant Secretary for Installations and Logistics, the Army staff, and the major field commands. Corporate responsibility for policy rested with a steering group, cochaired by the Under Secretary of the Army and Vice Chief of Staff, which included representatives from all Army staff agencies and, when necessary, the major commands. The coordinator synchronized Army activities in security assistance.

In another significant change, the select committee was made paramount among Army staff committees involved in major policies and plans. When first created in March 1970, it was a forum where the Army staff could informally discuss and recommend various means of balancing Army programs more effectively with the financial resources available. Its authority was limited to areas where “major policy issues are not involved.” On 29 March 1976 the Chief of Staff formally designated the committee “as the Army Staff’s senior committee.” It would not only coordinate, but also integrate and “make decisions on all Army policy, program, and budget matters.” Its members were responsible

[69]

for anticipating critical problems, to include those related to the sale of arms abroad. A new Strategy Planning Committee, chaired by the Assistant Deputy Chief of Staff for Plans and Operations, would prepare necessary studies and recommendations for the select committee’s consideration. As in the past, it met only at the call of the chairman.

The Freedom of Information Act and the Privacy Act flooded the federal government with requests to investigate its records. Army agencies, anticipating the deluge, created special branches for handling these problems. A typical example was the creation in April 1976 of the Freedom of Information/Privacy Act Branch within the Office of the Inspector General and Auditor General. This new agency was responsible for handling all requests for Inspector General records throughout the Army.

Combining the Office of Information with the Office of Public Information in the Army Secretariat in July 1976 ended an awkward arrangement created in 1955. The same officer had served as Chief of Public Information in the Army Secretariat and as Chief of Information under the Chief of Staff. The new agency, designated the Office of the Chief of Public Affairs, led to corresponding changes of titles throughout the Army. The Army’s information offices now parallel those of the Navy, the Air Force, and the Office of the Secretary of Defense.

After the Army staff reorganization of 1974, The Adjutant General (TAG) was no longer responsible for military personnel management. He retained his traditional administrative responsibilities for preparing and publishing official Army publications, controlling paper work, preserving the Army’s records, and operating the Army’s headquarters and worldwide postal system. He also inherited a group of miscellaneous activities collectively designated as Personal Environment Systems. They included the Institute of Heraldry, casualty and cemeterial functions, retired activities, nonappropriated fund management, and morale services such as recreation and entertainment. All organizations with operational missions were grouped within a single field operating agency, The Adjutant General Center.

A functional realignment took place during 1976 to provide more effective management of these fragmented agencies. The Adjutant General’s Comptroller Office assumed responsibility for financial management functions, except for automatic data processing systems. These functions include budgeting, accounting, reviewing proposed programs and their accompanying economic analyses, manpower management, and internal audit. A special division deals with the financial management of nonappropriated funds.

The Personnel and Administrative Directorate provides general staff support services, including the mailroom and word processing center.

[70]

A Plans and Operations Directorate is responsible for public affairs, legislative activities, contingency and force planning, and management improvement studies and programs. It also acts as TAG’s Information Systems Office.

Within The Adjutant General Center, a Deputy Chief of Staff for Administrative Systems and a Deputy Chief of Staff for Personal Environment Systems supervise the activities of operating agencies in their own particular areas. The Administrative Management Directorate is responsible for records management activities described below and for microfilm and office equipment management and policies, including word processing centers. The Administrative Operations Directorate is responsible for all the other traditional Adjutant General’s administrative functions primarily associated with the preparation, production, and processing of paper work. The Personal Affairs Directorate oversees casualty, cemeterial, and retired activities, and the Morale Support Directorate is responsible for those programs formerly managed by separate community and recreation service agencies. The Personal Environment Systems Management Office concerns itself with managing nonappropriated fund and general resources for community service and morale support programs.

Congress ordered the U.S. Postal Service during 1976 to take over postal units within the continental United States, Hawaii, and Alaska—a transfer that will eliminate approximately 350 active Army and nearly 800 reserve unit postal spaces. During changeover negotiations, the Postal Service, however, indicated it could not, for the near future, provide adequate service in certain locations involving approximately 122 positions.

Since its creation in 1962 the Army Materiel Command (AMC) underwent constant reorganizations and realignments in its headquarters and numerous field commands. These conditions reflected a more fundamental problem, chronic dissatisfaction with the Army’s entire system for developing and fielding new weapons and equipment. A special Army Materiel Acquisition Review Committee on 1 April 1974 recommended sweeping organizational and management reforms. The Army staff has been monitoring these problem areas ever since. Transferring responsibility for procurement and production from the Deputy Chief of Staff for Logistics to a new Deputy Chief of Staff for Research, Development, and Acquisition was a helpful step. Another was a parallel reorganization of AMC field commands and AMC headquarters, which on 1 January 1976 became the Materiel Development and Readiness Command (DARCOM). Materiel development and materiel readiness are now the two major organizational elements within the command. The former is responsible for research and development, producer tests

[71]

and evaluation, and initial procurement of weapons and supporting equipment. The latter is responsible for buying, fielding, and maintaining these systems.

Nearly every proposed reorganization of the Army since World War II has stressed the necessity of decentralizing and shifting operations to the field, a proposal that headquarters staffs have generally resisted. The DARCOM reorganization is one more attempt to decentralize operations, partly by reducing the headquarters staff. As noted earlier, the command will also split the commodity commands into separate research and development and materiel readiness commands. The reorganization will involve the transfer of some functions among various installations.

Accordingly, during fiscal year 1976 the Tank-Automotive Command became the Tank-Automotive Research and Development Command and the Tank-Automotive Materiel Readiness Command. The Missile and the Armaments Commands were similarly divided. Realignment of the Electronics, Aviation, and Troop Transport Commands may also take place.

One of the Army Materiel Command’s major subcommands since its creation was the Test and Evaluation Command. Assigned to it were development test facilities of the former technical services and operational test boards of the combat arms. Placing the latter under a predominantly development command created controversy within the Army. The Materiel Acquisition Review Committee’s testing team recommended transferring these operational test boards from the Materiel Command to the Training and Doctrine Command. The Department of the Army approved the recommendation on 1 July 1975 and directed the transfer of five operational test boards: the Air Defense Board at Fort Bliss, Texas; the Airborne, Communications, and Electronics Board at Fort Bragg, North Carolina; the Armor and Engineer Board at Fort Knox, Kentucky; the Field Artillery Board at Fort Sill, Oklahoma; and the Infantry Board at Fort Benning, Georgia. Later the Aviation Board at Fort Rucker, Alabama, was transferred to the Training and Doctrine Command. At the same installation the Materiel Development and Readiness Command created an Aviation Development Test Activity.

Since the Materiel Development and Readiness Command is principally responsible for producing arms sold abroad, the creation of the Coordinator for Army Security Assistance led to changes in the command’s organization. In November 1975 the International Logistics Center at New Cumberland, Pennsylvania, the field agency responsible for direction of these operations in the major commodity commands, was placed under an International Logistics Command. Brig. Gen. Tom H. Brain, the director of International Logistics, DARCOM headquarters,

[72]

now wears a second hat and directs the activities of the International Logistics Center.

Continued reduction of funds and resources for the Army triggered another round of proposals, a follow-up to Project Concise begun in 1974, to close or reduce operations at various bases. How to accomplish these reductions without weakening the Army’s combat effectiveness was the critical issue. In April 1976 Secretary Hoffmann announced the initiation of eighteen realignment studies. Preliminary analysis by the Army staff indicated that approval of these proposals could result in the elimination of about 3,600 civilian positions and the conversion of about 1,400 military positions to combat roles. Eliminating the civilian positions might save $42 million annually. The studies emphasized reducing the number of small, single mission installations, consolidating school activities, and streamlining storage and maintenance operations. Each study assessed alternative courses of action and evaluated the effects each would have on local communities. Several of the studies considered functions and activities which civilian contractors might perform.

One of the earliest recommendations approved was to lease some port facilities at the Marine Ocean Terminal in Oakland, California, to private industry. By late fall 1976 the Army announced decisions on five other recommendations. Two dealt with the conversion of most base operations functions to contract at Stewart Army Sub-Post, New York, and Selfridge Air National Guard Base near Detroit, Michigan. Two other decisions rejected realignment proposals for the Savanna Army Ordnance Depot in northwest Illinois and Jefferson Proving Ground in southeast Indiana. In the fifth case, the Army announced the closure of housing facilities at Schilling Manor near Fort Riley, Kansas, as the preferred alternative, with the final decision to be made following review of congressional and public comments.

Two studies involved U.S. Army Security Agency installations at Arlington Hall Station in Arlington, Virginia, and the Vint Hill Farms Station, near Warrenton, Virginia. Decisions in these cases depend upon the reorganization of the Army intelligence community discussed in Chapter IV.

Decisions on the remaining ten base realignments had not been made by the end of fiscal year 1976. The need to conserve manpower, however, will keep attention fixed on these and other base reductions in the years ahead.

The Office of Management and Budget and the Department of Defense established new policies and procedures during the year for contracting out as many of the commercial- and industrial-type activities as can be justified on the basis of cost. As a matter of policy, the Army is now required to use higher factors in estimating its costs of operating

[73]

support activities and to compare these more realistic estimates with bids submitted by contractors.

The Deputy Chief of Staff for Logistics is responsible for monitoring the Army’s commercial- and industrial-type activities, of which there were 3,153 as of the end of the fiscal year. Of these, 1,574 were operated by the Army, 141 by contract, and 1,438 jointly by contractors and the Army. The capital investment was approximately $3.8 million and annual operating costs $2 million.

Management Information Systems

Computer hardware technology matured during the 1970’s, but the software associated with it did not advance as rapidly. Both are expensive, although software development costs are much greater in the long run. In the current inflationary environment the Office of Management and Budget and Congress have required detailed justification for purchasing or leasing computer equipment. They have also requested, when economically practical, that government agencies contract with private industry for performing computer functions. Since the military services are by far the largest users of automatic data processing systems (ADPS), the Office of Management and Budget and Congress are understandably scrutinizing their requests for developing, acquiring, and operating automatic data processing systems.

As Director of Management Information Systems in the Office, Chief of Staff, from July 1973 to July 1976, Maj. Gen. Richard L. Harris was responsible for the restructuring of the Army’s organization and management procedures for the design, purchase, and operation of automatic data processing systems. The Army in March 1976 revised and published Army Regulation 18-1 governing the objectives, responsibilities, policies, and procedures for Army management information systems and simplified the documentation and procedures for the systems as well. The Army also decentralized control over the data processing systems, in contrast to the tight controls needed before the Army reorganizations of 1973 and 1974 when the Assistant Vice Chief of Staff was urgently developing mutually compatible systems. In other changes the Army simplified the review of the management information systems by clarifying reporting requirements, eliminating some, and by reducing the volume of computer printouts through the use of microform equipment. Further, it clarified management relationships between nontactical and tactical data systems. A final change was to establish policies and procedures for the security of automatic data processing systems and for the protection of sensitive information as required by the Privacy Act of 1974.

[74]

During fiscal year 1976 the Management Informations Systems Directorate published an inventory defining the 343 separate information systems supporting Headquarters, Department of the Army. The Computer Systems Support and Evaluation Agency began a review of the terminals used at the twelve data processing installations that support Army headquarters. Those installations, as well as Army Headquarters Information Systems offices, were incorporated into groups for the exchange of information and the resolution of problems. The Information Systems offices are responsible for the management and control of the data processing systems assigned to their respective Army staff agency. In March 1976 a Management Assessment Board conducted an evaluation of the U.S. Army Management Systems Support Agency in the Pentagon. The board made thirty-one recommendations designed to improve the agency’s operating effectiveness.

Another regulation calls for a biennial review of recurring controlled management information requirements and automatic data processing products. The purpose is to eliminate unnecessary production of information, improve the effectiveness of what is produced, and reduce workload and costs.

The Army Software Conversion Center was established this past year as part of the U.S. Army Computer Systems Support and Evaluation Agency. The center will provide helpful information for saving time and money when data processing installations replace existing equipment. In a related program the Army was able to make use of $51 million worth of excess automatic data processing equipment during the year, including the transitional quarter. Improved management techniques at data processing installations saved $3.5 million. Work measurement improvements alone resulted in average savings of approximately $100,000 per installation.

One of the major tactical automatic data processing systems is the Combat Service Support System. It is a mobile system that supports the requirements of active Army divisions for administrative and logistical data. After successful tests in the 2d Armored, 1st Cavalry, and the 101st Airborne Divisions, the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Financial Management in July 1974 approved the extension of the system to all active divisions. By the end of fiscal year 1976, thirteen divisions were equipped with the new Combat Service Support System. The last three of sixteen projected divisions should receive the system next year.

The Adjutant General’s Office is responsible for developing a standard computer output microfiche system as an economical alternative to the paper used by the Army’s Base Operating Information System. The

[75]

General Services Administration will purchase the required equipment and services. Initial costs are estimated at $3 million, but the system is expected to pay for itself within three years. Savings on the paper involved in the Standard Army Installation Logistics Systems, the Standard Installation/Division Personnel System, and the Standard Army Financial System are estimated at $700,000 a year.

Another program administered by The Adjutant General’s Office to reduce paper work costs is the use of automated typing equipment in word processing centers. During the current year 226 new word processing centers costing $3.3 million were introduced, more than double the number (103) in 1975. One hundred forty-five spaces were eliminated at a saving of $1.6 million in personnel costs and an additional $160,000 in equipment. In setting up such new centers, however, the Army encountered difficulties caused by the rapid changes in word processing technology.

In summary, the Army in fiscal year 1976 continued to improve the use and management of computers in automating its business functions.

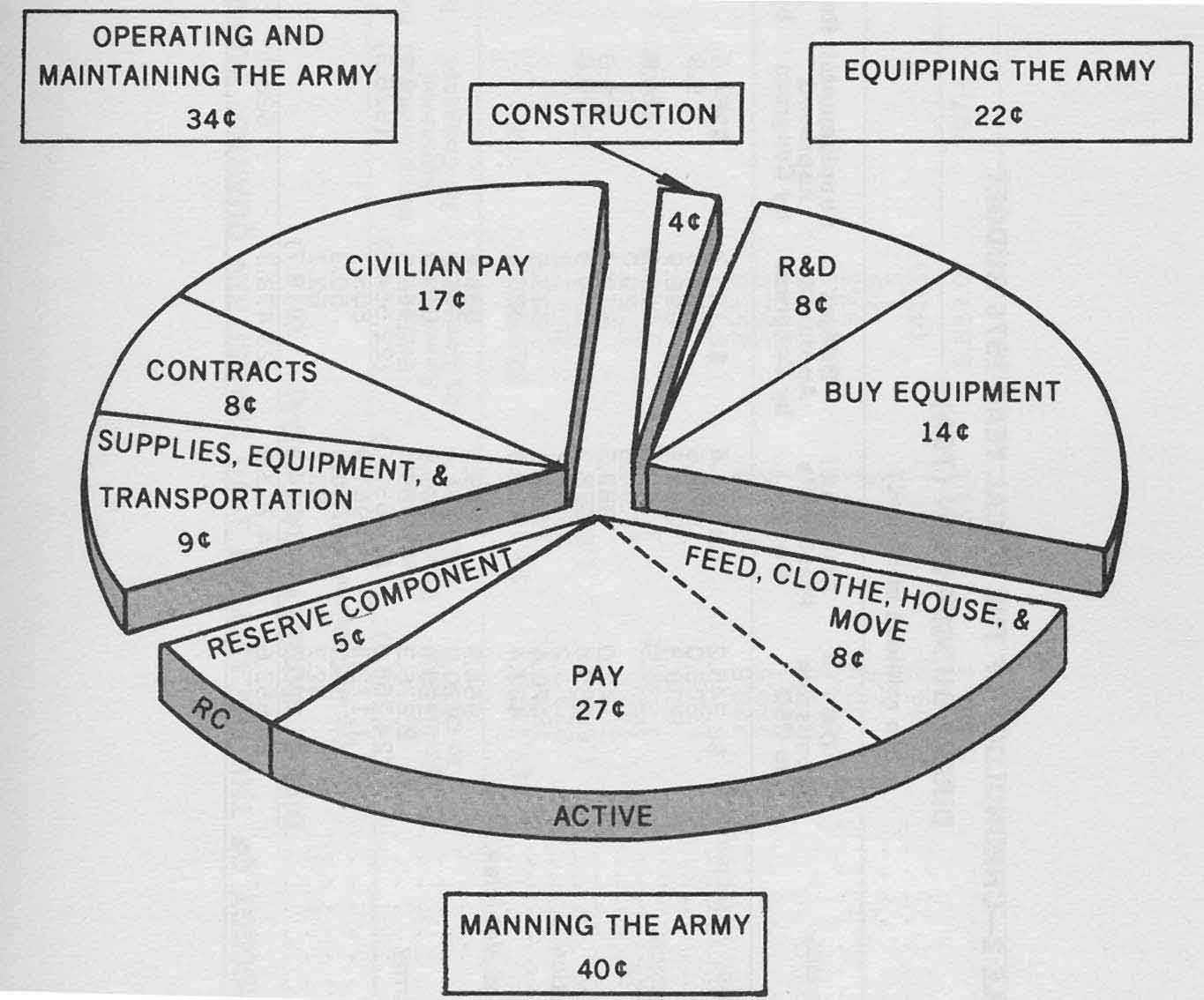

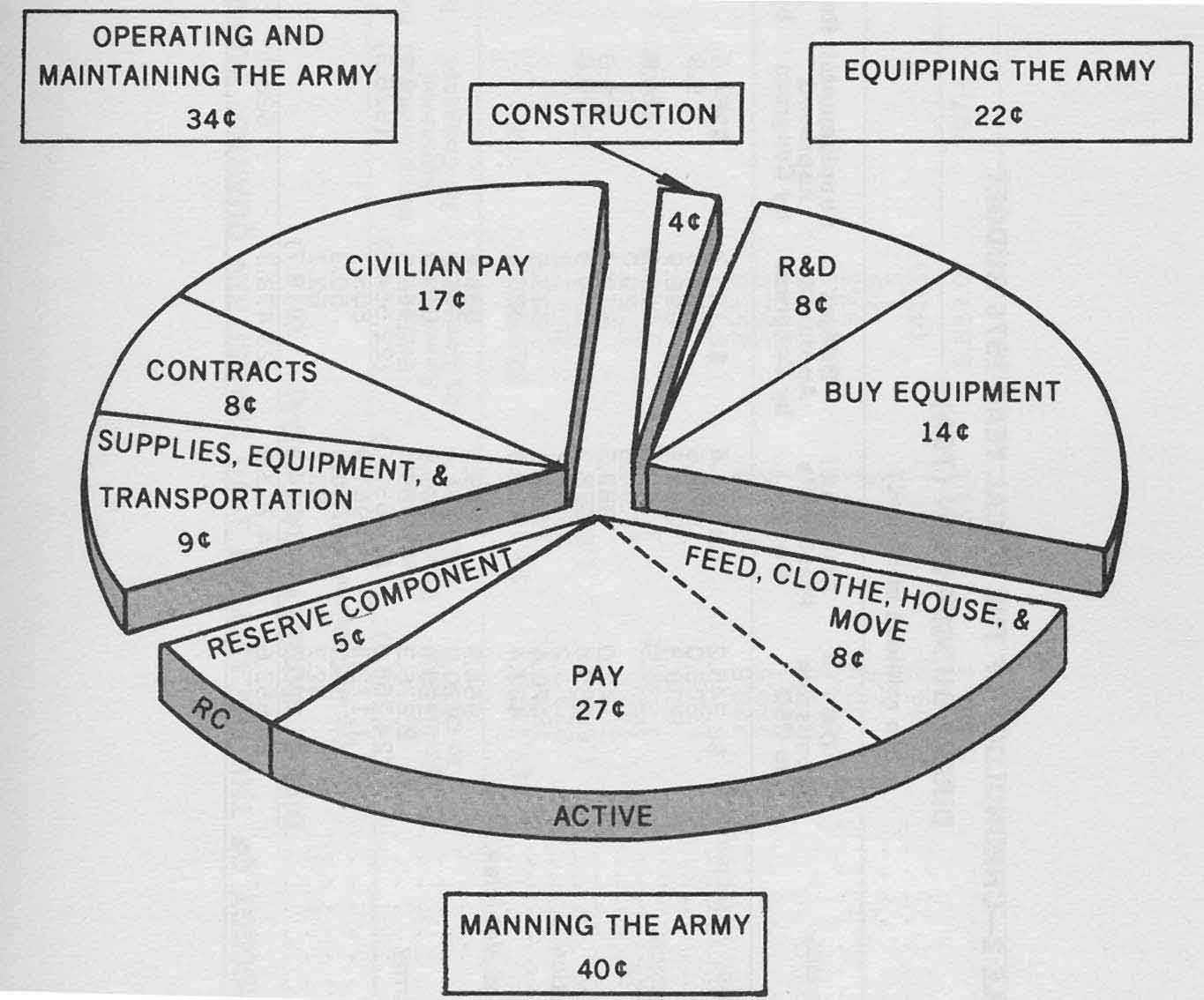

Congress authorized Army appropriations of $30 billion for the period 1 July 1975-30 September 1976. The fiscal year 1976 portion was $24 billion, an increase of 13 percent over the previous year’s; half of this increase represented inflation. Tables 2 and 3 show Army appropriations by major budget programs, which for convenience can be placed in four general categories: military manpower, equipping the Army, operation and maintenance, and military construction.

In the first category, military personnel appropriations were enough to expand combat forces to sixteen active divisions and to maintain an Army of 785,000. In the second category, Congress appropriated $3.2 billion for the development and procurement of weapons and supporting equipment, including those required by the three new divisions. Additional funds permitted replenishing stocks of equipment in the United States and overseas. Major weapons procured were the TOW (tube-launched, optically tracked, and wire-guided) and DRAGON antitank missiles, M60 tanks, and armored personnel carriers. In the case of operation and maintenance funding, inflation and budget restrictions in previous years had forced severe cutbacks in maintenance at installations and facilities serving both the active Army and the reserve components. The $8 billion appropriated this year will allow the Army to begin improving substandard maintenance conditions. In the fourth category, military construction, the budget was approximately $900 million.

[76]

Half of this was spent on military housing, hospitals, dental clinics, and community facilities on post.

Chart 1 shows how the Army’s dollar was spent in these four categories in fiscal year 1976.

CHART 1 — HOW THE ARMY DOLLAR WAS SPENT

IN FISCAL YEAR 1976

Before Robert S. McNamara became Secretary of Defense, the Army frequently did not provide adequate justification for its budget requests. During the 1960’s, however, Secretary McNamara directed the armed services to prepare detailed economic analyses to support their requests for new weapons systems and equipment, particularly expensive automatic data processing systems. He insisted that such analyses include cost-effective studies comparing alternative methods of accomplishing the same military or supporting missions. These analyses were to include not only the capital investment for developing and producing new weapons and equipment, but also the associated costs for training personnel in the operation and maintenance of them.

[77}

TABLE 2—CHRONOLOGY OF THE FISCAL YEAR 1976 BUDGET

DIRECT BUDGET PLAN (TOA)

(in millions of dollars)

|

Appropriation |

DA Submission to OSD |

Amended President’s Budget |

Budget Approved by Congress |

Supplemental Approved by Congress |

Reprograming Approved by Congress |

Total Approved by Congress |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Military Personnel, Army |

$8,345.2 |

$8,264.4 |

$8,185.3 |

$254.5 |

$-3.7 |

$8,436.1 |

|

Reserve Personnel, Army |

506.0 |

464.6 |

468.9 |

9.9 |

478.8 |

|

|

National Guard Personnel, Army |

736.3 |

697.3 |

696.9 |

-3.8 |

693.1 |

|

|

Operation & Maintenance, Army |

7,231.9 |

7,352.0 |

7,052.0 |

224.9 |

2.7 |

7,279.6 |

|

Army Stock Fund |

94.0 |

20.0 |

20.0 |

|||

|

Operation & Maintenance, Army Reserve |

342.0 |

332.3 |

310.7 |

9.0 |

3.8 |

323.5 |

|

Operation & Maintenance, Army National Guard |

690.8 |

678.2 |

649.9 |

20.8 |

670.7 |

|

|

National Board for the Promotion of Rifle Practice |

.2 |

.2 |

.2 |

.2 |

||

|

Aircraft Procurement, Army |

470.4 |

362.3 |

337.5 |

337.5 |

||

|

Missile Procurement, Army |

462.4 |

460.8 |

426.6 |

-5.9 |

420.7 |

|

|

Procurement of Weapons & Tracked Combat Vehicles, Army |

964.9 |

989.3 |

885.4 |

885.4 |

||

|

Procurement of Ammunition, Army |

964.9 |

989.3 |

885.4 |

37.3 |

682.5 |

|

|

Other Procurement, Army |

1,220.9 |

1,002.8 |

919.3 |

919.3 |

||

|

Research, Development, Test, & Evaluation, Army |

2,376.3 |

2,189.4 |

1,956.5 |

9.2 |

1,965.7 |

|

|

Subtotal, excluding Construction |

(24,268.3) |

(23,639.0) |

(22,554.5) |

(528.3) |

(30.4) |

(23,113.2) |

|

Military Construction, Army |

1,172.3 |

961.9 |

805.7 |

10.2 |

815.9 |

|

|

Military Construction, Army Reserve |

50.3 |

50.3 |

50.3 |

50.3 |

||

|

Military Construction, Army National Guard |

62.7 |

62.7 |

62.7 |

62.7 |

||

|

Subtotal, Construction Accounts |

(1,285.3) |

(1,074.9) |

(918.7) |

(10.2) |

(928.9) |

|

|

Total Direct Budget Plan (TOA) |

25,553.6 |

24,713.9 |

23,473.3 |

528.3 |

40.6 |

24,042.1 |

[78]

TABLE 3—CHRONOLOGY OF THE FISCAL YEAR 1976 TRANSITION

QUARTER BUDGET

DIRECT BUDGET PLAN (TOA)

(in millions of dollars)

|

Appropriation |

DA Submission to OSD |

Amended President’s Budget |

Budget Approved by Congress |

Supplemental Approved by Congress |

Reprograming Approved by Congress |

Total Approved by Congress |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Military Personnel, Army |

$2,137.3 |

$2,100.0 |

$2,066.1 |

$88.3 |

$2,154.4 |

|

|

Reserve Personnel, Army |

184.1 |

168.9 |

165.3 |

3.2 |

168.5 |

|

|

National Guard Personnel, Army |

229.7 |

225.3 |

209.1 |

7.0 |

216.0 |

|

|

Operation & Maintenance, Army |

1,862.9 |

1,883.7 |

1,779.0 |

92.4 |

1,871.4 |

|

|

Operation & Maintenance, Army Reserve |

109.7 |

98.2 |

91.1 |

4.0 |

95.1 |

|

|

Operation & Maintenance, Army National Guard |

188.5 |

183.4 |

173.3 |

9.4 |

182.7 |

|

|

National Board for the Promotion of Rifle Practice |

.072 |

.073 |

.093 |

.002 |

.095 |

|

|

Aircraft Procurement, Army |

87.3 |

59.4 |

59.4 |

59.4 |

||

|

Missile Procurement, Army |

138.3 |

56.5 |

42.6 |

42.6 |

||

|

Procurement of Weapons & Tracked Combat Vehicles, Army |

328.8 |

282.3 |

255.0 |

255.0 |

||

|

Procurement of Ammunition, Army |

269.5 |

271.2 |

252.8 |

252.8 |

||

|

Other Procurement, Army |

387.1 |

197.7 |

197.7 |

197.7 |

||

|

Research, Development, Test, & Evaluation, Army |

621.6 |

585.6 |

504.5 |

3.2 |

507.7 |

|

|

Subtotal, excluding Construction |

(6,544.8) |

(6,133.3) |

(5,795.9) |

(207.4) |

(6,003.3) |

|

|

Military Construction, Army |

35.5 |

37.1 |

37.1 |

37.1 |

||

|

Military Construction, Army Reserve |

2.5 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

||

|

Military Construction, Army National Guard |

1.5 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

||

|

Subtotal, Construction Accounts |

(39.5) |

(41.1) |

(41.1) |

(41.1) |

||

|

Total Direct Budget Plan (TOA) |

6,584.3 |

6,153.4 |

5,837.0 |

207.4 |

6,044.4 |

[79]

Over the past decade the Army gradually improved its methods for justifying acquisition of new weapons systems. The same was true of requests for automatic data processing equipment and other major capital investments and for comparing Army costs with potential contracts with private industry. The Army was weakest in program evaluation; that is, justifying and analyzing the costs of current programs. In some cases, there was no justification provided for costs associated with operation and maintenance (OMA) budget programs.

There were two principal reasons for these inadequate analyses. One was the low priority assigned to such economic analyses and program evaluation by the Army staff and major field commanders. The second was the shortage of economic analysts trained to prepare the sophistocated studies required. Those with the proper training and experience were generally placed in higher headquarters. Those at the installation level, where much of the money is spent, often lacked the necessary education.

The Comptroller’s Cost Analysis Directorate is responsible for monitoring and reviewing the Army’s economic analysis program. After examining the problems outlined above, this office wrote directives and regulations expressing in relatively simple terms the minimum essential elements required for a proper economic analysis. Army budget directives now include a requirement that appropriation and program directors in Army staff agencies and major commands make certain that properly prepared economic analyses accompany all budget requests. The Cost Analysis Directorate has no authority to approve or disapprove these budget requests. Its responsibility is to review the work done by economic analysts to determine whether they contain the essential elements required.

During the year, life-cycle cost estimates became more important in the acquisition of major Army materiel systems. The Cost Analysis Directorate prepared guides stating the essential standards for documenting these estimates. Their instructions called for uniform cost structures, cost elements, and definitions throughout the Army. In a simplified manner they also sought to illustrate the generic terms employed in estimating the research, development, capital investment, and operation and maintenance costs of any materiel system’s life cycle.

Every year military pay raises and inflation have made it necessary to completely revise the unit cost structures of the Army Force Cost Information System. A major improvement in the system’s data processing equipment now allows additions to or subtractions from its data bank without reworking the entire program. A second improvement permits computing the cost of equipment in constant rather than current dollars. Another change begun this year will estimate costs of thirteen proposed

[80]

weapons systems as if they already existed in combat units. Responsible planners will be able to incorporate such costs in evaluating their projects.

The Anti-Deficiency Act (31 U.S.C. 665) holds Army officials responsible for obligating or spending more funds than Congress appropriated for particular budget categories and subcategories. Other violations occur when funds spent exceed administrative limitations imposed on their use. Frequently Defense or Army directives also require permission from higher authority if obligations or expenditures on particular projects exceed a specified amount. Inflation in recent years has driven initial cost estimates above such limitations. Possible violations reported during fiscal year 1976 were double those for fiscal year 1975. Many of these involved minor construction projects.

To prevent such violations in the future, the Army now requires tighter auditing of accounts and publicizes the types of violations encountered. Financial management courses have been revised to include instruction on various types of fund limitations in simple, graphic terms for the benefit of managers at the installation level where most of the violations have occurred.

The Army’s Standard Finance System (STANFINS), an automated system used by installations to perform standardized financial and accounting functions for appropriated funds, expedites the processing and reporting of disbursement and collection transactions at all levels through the Finance and Accounting Center in Indianapolis. Developed in 1970 as part of the Army’s Base Operating Information System, the Standard Finance System is now in operation at 54 installations, 6 of which were added in fiscal year 1976, and in 8 major commands. It provides data used in planning, programing, and budgeting and also feeds accounting data to other services and to Defense agencies in the Washington area. During the year STANFINS data was transferred to microfiche, and an enormous amount of paper was saved.

The Department of the Army Management Review and Improvement Program was reexamined to insure that only those management improvement programs that pay dividends are promoted. This led to the establishment of an Army-wide Productivity Improvement Program to achieve the most in productivity growth and improve resource management. Responsibility for this program was assigned to the Office of Management Practices, Comptroller of the Army.

To help offset the pressures of declining military appropriations, the Department of Defense assigned a 2 percent productivity increase as the Army goal for fiscal year 1976. This goal was achieved in those areas where it was possible to establish a basis for measuring productivity. To increase efficiency further, the Army’s productivity measure-

[81]

ment was expanded to cover 19 percent of the military and 63 percent of its civilian work forces.

The Value Engineering Program contributes substantial dollar savings. Existing as a formal program in five major Army commands, it is concerned with the elimination or modification of anything that adds cost to an item, process, or procedure, but which is not necessary to its basic function. For example, at one ammunition plant, a threaded, metal plug used in the production of 105-mm. shells was replaced by an unthreaded, plastic plug for a first-year saving of $977,000. Within the five affected commands, sixty-nine value engineers work full time. Savings in 1976 from value engineering was $122.9 million, $16.5 million of which was derived from civilian contractors participating in the Army’s program. Value engineering techniques have been increasingly successful in the areas of research and development, procurement, production, construction, and maintenance.

Recognizing that new and improved capital equipment contributes between 40 and 60 percent of the productivity increase in the private sector, the Army started the Quick Return on Investment Program in 1974 to expedite the acquisition of selected equipment. Previously, capital investment opportunities had been lost because of long administrative delays encountered in the normal budget review process and competition from higher priority requirements. With this program, the Army has a streamlined method of obtaining investment funds for equipment and the prospect that it will pay for itself within two years after installation. From 1974 through September 1976 approximately $12 million worth of equipment was procured with the cost of items ranging from $1,000 to $100,000. Savings derived from the Quick Return on Investment Program have been used to meet other previously unfunded requirements at the installation level. The current annual return on investment for this program is approximately 160 percent and is expected to continue at this rate. Cumulative annual savings through this year were $19 million.

Despite the efforts of the Army to reduce the amount of paper work generated each year, staggering quantities continue to accumulate. The control, storage, disposition, and, in many cases, declassification of these records demand constant attention from records managers at all levels. During the past year the Army took a number of actions to strengthen its overall control of the linear miles of records produced since World War II.

One step was the establishment of The Adjutant General’s Record Management Committee in April 1976. Chaired by the chief of the Records Management Division, the committee provides supervision and coordination of all aspects of the records management program.

[82]

Another was a broad-gauged survey of over a hundred linear miles of records in the major Army commands by records management staff members. The main objective of the survey was to investigate management practices, the use of equipment and supplies, disposition and maintenance procedures, declassification programs, the effect of the Freedom of Information and Privacy Acts, and the use of word processing and micrographics in the field. Among the major problems uncovered by survey members was a tendency of the major command staff officials to divert their records managers to administrative and clerical duties. In these circumstances, they were unable to fulfill their primary roles. The survey also revealed that numerous requests submitted under the Freedom of Information and Privacy Acts occupied a considerable amount of the records manager’s time.

In the areas of records retirement and retention, the Army offered 45,000 linear feet to the National Archives; the bulk of this group consisted of files in the Washington National Records Center. Records management officials also carried out further analyses of the file series now considered as permanent in an effort to reduce the number in this category. If time limits can be placed on the retention of more types of records, problems of control, space, and administration can be greatly lessened.

A further means to save personnel and space was through the increased use of micrographics, a process which can reduce thousands of pages to a few small reels or cards. During the year, the Army provided training in micrographics to over three hundred people. At the Army Finance Center, thirty-four jobs were eliminated and an annual savings of $300,000 resulted from the use of the technique. Conversion to microfiche of 1.3 million case-documents of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology led to the retrieval of 2,500 square feet of critical space; in addition, the move improved administration of the files and permitted pathology researchers to have multiple access to the records.

In January 1976, a two-year program got under way to put official military personnel files on microfiche. As people are separated from the Army, their official microfiche file will be matched with their records jackets and their health records; the packet will then be retired to the National Archives and Records Service. Thus far, the new procedure has caused some difficulty, and interim arrangements had to be reached with the National Archives. A final agreement will be made after the Army decides whether the records jacket is to be changed or eliminated.

Another project to improve the administration of personnel files involved several Army agencies. At the U.S. Army Enlisted Records and Evaluation Center at Fort Benjamin Harrison, Indiana, there were about 125,000 partial records containing official documents of servicemen whose status was then unknown. In May 1975 the U.S. Army Reserve Com-

[83]

ponents Personnel and Administration Center at St. Louis agreed to accept a sample of 3,000 of these records to determine where they should be retained. As it turned out, the sample was representative of the group. By the end of the report year the Army had examined over 72,000 of these records, using both visual and computer-tape checks. The results showed that slightly more than 56 percent concerned persons who had been discharged and whose records belonged in the National Personnel Records Center of the General Services Administration; about 43 percent pertained to soldiers who still had statutory service obligations and, therefore, should be held by the Reserve Components Personnel and Administration Center; and less than half of one percent applied to personnel on active duty and belonged at Fort Benjamin Harrison. The relocation of these files at their proper sites and the separation of unobligated, obligated, and active duty records were major improvements in records holdings.

Although the war in Vietnam is several years past, the last segments of the records from that area did not arrive in Washington until this year. The Vietnam records now total about 32,000 linear feet and are kept at the Washington National Records Center.

In Thailand, a records crisis arose when Thai resistance to the presence of U.S. forces resulted in the imposition of a March 1976 deadline for the withdrawal of all troops. Since the Army had responsibility for all joint records in Thailand, an urgent program went into effect to evacuate them before the deadline. The plan called for processing and shipping the records first to Hawaii, where they would be screened; those to be retained would then be sent to Washington to be inventoried and transferred to the National Records Center. The Thailand Records Retrieval Team set up to carry out this task managed to process and ship out 2,000 linear feet by the end of the year and an additional 4,000 before the deadline approached. Fortunately, the Thai government granted the United States a four-month extension in March to complete its withdrawal. When the team finally departed in July, it had handled about 9,000 linear feet, some of which had been flown out by helicopter. By the end of the fiscal year, some 6,000 feet had reached Washington and about half of this total had been processed, inventoried, and transferred to the Washington National Records Center; another year will probably be required to handle the remaining Thai records.

A problem in storage space came up in April 1975, when the General Services Administration ordered the Army to close its records depository at Neosho, Missouri, on the grounds that it was not cost effective. Although the Army was able to relocate most of the records at Neosho in other depositories, it could not find room for the Army Finance and Accounting Center records. When the Veterans Administration took over

[84]

the Neosho facility, the Army had to work out an arrangement for retention of the finance files at the site on a prorated cost basis.

For several years, the Army, along with other government agencies, has been reviewing and declassifying as many of its voluminous records as possible. The task became more difficult during the past year because of reductions in the funds available to hire reserve personnel to carry out this time-consuming process. Accordingly, in April 1976 the Army reached an agreement with the National Archives under which the latter would perform the initial declassification review of Army documents in its possession. The Army declassification staff would then review all doubtful cases and prepare for the Secretary of the Army lists of documents to be excluded from declassification. Some idea of the volume in the exempted category may be drawn from the decision of the Secretary of the Army in December to continue classification of 11,000 documents, thirty or more years old, until a specified future date; most of the documents related to intelligence, cryptography, or operational plans relevant to current international affairs. Over 6,000 linear feet of records covering the 1946-54 period went through the review process, and, to date, over 30,000 of the 51,000 feet in this group have now been declassified. In May the Army launched a project to identify the volume of records in the 1955-64 decade, so that permanent retention and declassification schedules for documents to be retained more than thirty years may be considered. Thus far, the surveyors have identified over 20,000 linear feet at the Washington National Records Center that will require declassification review.

With more and more Army archival material declassified and now available to the public, and amendments to the Freedom of Information Act further easing public access to the records, the work load of requests steadily increased. Freedom of Information Act totals came to well over 18,700 for the fifteen months of fiscal year 1976, or well over 3,700 per quarter. By way of comparison, only 2,300 requests came in from mid-February to the end of June 1975.

In a related area, the Privacy Act of 1974 also imposed a heavier burden upon records management personnel. Although Army Regulation 340-21 became effective in September 1975 and included three hundred systems of records in use by the Army, by November it became apparent that not all systems were covered. An Army review led to publishing notices of two hundred more systems in the Federal Register, as required by law.

The Secretary of the Army established a Privacy Review Board to act on his behalf on requests for further review of any initial refusals to amend the records. Statistically, the first report, covering the September-December 1975 period, indicated that the Army received over 10,500

[85]

requests to determine the existence of records, 13,000 for access to records, and over 9,600 for amendment of records. There were no denials, appeals, or court actions.

Since all services are affected by the Privacy Act, the Interservice Training Review Organization has requested that they develop a joint curricula training program. When this is completed, all Defense personnel will be apprised of their responsibilities under the act.

To sum up, the Army has made some advances in the struggle to control the flood of documents in production, to establish stricter standards for permanent retention, and to make the records of the past more accessible to the public. Much, however, still remains to be done.

[86]

|

Go to: |

|

Last updated 7 September 2004 |