Department of the Army Historical Summary: FY 1984

3

Operational Forces

By necessity, the Army plans its force structure concomitantly with sustainment, mobilization, and training adjuncts. It must maintain current operational forces at a level that enables units to carry out the doctrine expounded in FM 100-5. This is accomplished by activating, inactivating, or realigning active Army units; readjusting the size and composition of the force structure; refining contingency plans; and maintaining personnel, unit, and materiel readiness. Underpinning these efforts are deployed forces around the world that serve as deterrents to enemy aggression and as a demonstration of American capability and credibility to defend our allies. Other areas of concern to the operational forces are chemical and nuclear activities and support to the civilian sector of our society.

Fiscal year 1984 marked a shift in the composition of the United States Army force structure. The Army refined many of the 16 active and 10 reserve component division designs through the Army of Excellence design initiatives to accommodate force structure needs within a constrained active Army end strength. These initiatives helped to develop a light division tailored for the low-intensity threat that the Army forecast into the twenty-first century, while retaining the capability to fight on the mid- to high-intensity battlefield when properly augmented. Light divisions, through their relative improvement in deployment, permit the timely application of combat power to stabilize or neutralize the situation at minimal force levels. In addition to the light infantry division, the Army of Excellence placed increased emphasis on providing the corps commanders with the means to conduct the AirLand Battle. This included shifting artillery, intelligence, and combat aviation assets from the division to the corps. The Army of Excellence recognized the efficiencies that could be gained from new and emerging technologies.

The Grenada rescue mission reemphasized the Army's need for a force capable of successfully handling similar low intensity operations because of the increasing frequency of these situations. Concomi-

[49]

tantly, Army leaders viewed units designed exclusively for mechanized and armor combat against Warsaw Pact armies as too rigid and too large to be transported quickly to the European theater in case of a NATO emergency. Therefore, the Army began refining force structure to reflect the current philosophy of employing lighter units to engage in counterterrorist and other low intensity actions.

The Army planned to activate the 10th Infantry Division (Light) in early 1984, with the 6th Infantry Division (Light) being activated in 1986. Meanwhile, the 7th Infantry Division (Light) continued its conversion into a light division. In addition, ten heavy divisions were being converted into the lighter Army of Excellence force structure organization. The 2d Armored Division finished its reorganization during the year, and the remainder of the heavy divisions, excluding certain aviation units, will complete reorganization by the end of fiscal year 1985. Secretary of the Army John O. Marsh, Jr., also announced the future activation of a seventeenth active Army division but did not specify a tentative date or a possible location.

Because of a renewed emphasis on low-intensity conflict, the Army expanded the Special Operations Forces (SOF). The Army activated Headquarters, 75th Ranger Regiment, in July and followed this action with the establishment of a third Ranger battalion at Fort Benning in October. Fort Lewis witnessed the activation of a fourth Special Forces group, the 1st Special Forces Group, in September. The Special Forces Group (SFG) headquarters and two battalions will be stationed at Fort Lewis, while a third will be stationed on Okinawa.

The establishment of the Fourth U.S. Army on 1 October 1984 at Fort Sheridan, Illinois, increased the number of CONUS armies to five. This ended a two-year program upgrading Army Reserve and National Guard units and improving supervisory channels.

The Army, confronted with strategic, operational, and tactical obligations at a time of manpower ceilings and scarcer resources, responded with modification to the composition and organization of its force structure to create an Army capable of meeting increasingly complex present and future responsibilities. General Mahaffey, DCSOPS, stated in "Structuring Force to Need" (Army, Oct 84) that "our national security policy, supporting military strategy, and the characteristics of those regions of vital interest to the United States collectively demand forces with greater balance, flexibility and deployability than those we currently possess." A balanced force covers four areas: forward-deployed and CONUS-based forces, active Army and reserve components, heavy and light units (types of forces), and

[50]

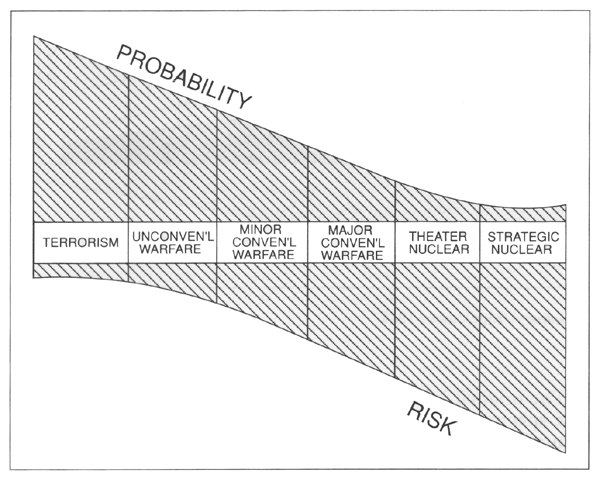

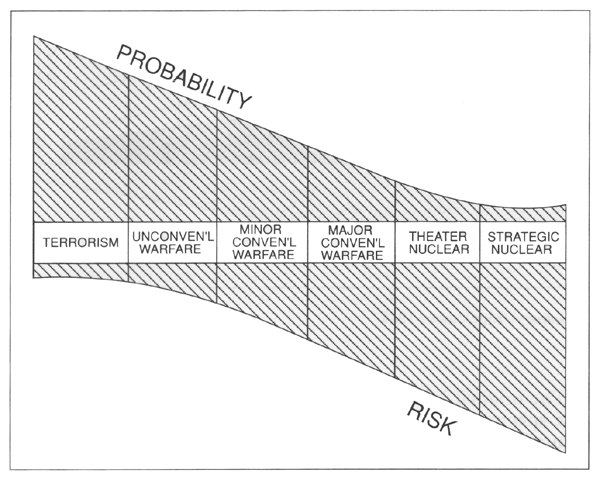

combat-versus-support forces (so called tooth-to-tail ratio). The balance is not designed for numerical equality of units in each respective area, but for a proper ratio that satisfactorily meets the varied strategic and operational requirements facing the Army. As a consequence, the Army changed its conflict model from a simplified and utilitarian one, as seen in Figure 1, to a more complex but more realistic model as shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 1 - SIMPLIFIED CONFLICT MODEL

[51]

FIGURE 2 - REALISTIC CONFLICT MODEL

Source: Army, October 1984.

The original model reflected a linear view of conflict with discrete spectrums of non-overlapping forms of warfare. The Army oriented its force structure and balance toward the conventional warfare sector, particularly with regard to the major threat, i.e., Soviet aggression in NATO. Thus Army forces became heavier in personnel, materiel, and weapon systems to meet treaty commitments in Europe.

The newer model demonstrated the potential overlap of all elements of the conflict spectrum, that, in turn, could conceivably lead to a minor terrorist incident escalating to nuclear war. Such a possibility led Army planners to conclude that the strategic nuclear deterrent concept remained valid. Moreover, a conventional war in Europe might escalate into a nuclear exchange, a threat that decreased the probability of major conventional warfare there. A third observation was that with few exceptions-such as the Iran-Iraq War, the Israeli Arab Wars, and the Korean War-low-intensity

[52]

warfare has characterized military operations since World War Il. Army leadership determined that the force structure needed to be rebalanced to meet requirements of the low to mid-intensity conflicts, including terrorist activities prevalent today, yet still maintain sufficient mechanized and armored forces to deter aggression in Europe, Southeast Asia, and Southwest Asia.

Equipment heavy forces are difficult to deploy in a timely manner from CONUS. Shortages of strategic air and sealift are factors in strategic forward deployment, either to deter aggression or to slow any initial enemy assault until CONUS-based reinforcements can be lifted to the threatened area. The Army increased the number of fight forces in the United States to provide rapidly deployable units either to support heavy units in Europe and Korea; to respond to aggression anywhere in the world, particularly in Southwest Asia; or to engage in short missions such as the rescue of students and protection of democracy in Grenada. Restructuring occurred without benefit of increased manpower ceilings and under intense congressional scrutiny.

Nevertheless, the Army chose to concentrate on the heavy-versus-light unit balance and began to implement a light division force structure. Active duty personnel ceiling strengths meant that the manning for new, light divisions and manpower to operate the newly fielded advanced weapon systems had to come from existing Army personnel resources. The Chief of Staff established a constant end strength of 780,000 for the active Army and mandated future increases in personnel for reserve components. This far-reaching decision necessitated a change in the organization of Division 86 units as well as the formation of light divisions to achieve the proper balance in the force structure for current operational capability.

During FY 84, the Army underwent a transition to balance the restructuring of the light forces against the modernization of heavy forces, while simultaneously maintaining their combat readiness. The formation of, or conversion to, light divisions was planned to minimize disruption to the ongoing improvement of the heavy divisions. The Army's goal was to field leaner and stronger divisions in a more mobile force.

Premised on the new AirLand Battle doctrine and integrating the lessons learned from field exercises in Honduras, the Army acted to improve and augment Special Operations Forces to fulfill important missions such as security assistance support, psychological warfare, intelligence, civic action, mobility, medical assistance, communications, and construction capabilities. Light divisions also had missions in the low- to mid-intensity levels of conflicts, so the

[53]

Army planned to complement the SOF improvements with light division development to increase combat capabilities. Along with slimming down heavy divisions, these actions with the SOF and light divisions demonstrated the Army's determination to enhance overall readiness to meet a variety of contingency operations.

In past wars the U.S. Army had time to mobilize forces gradually and to prepare for combat operations. Current simulations demonstrated that the Army would not enjoy the same grace period in a future war and would depend heavily on the peacetime readiness of units to deploy for combat as a major ingredient for success. Therefore, the Army chose a fully manned and trained combat force organized to handle a variety of contingencies worldwide, equipped with modern weapon systems properly maintained, and sustained by adequate materiel stocks and support facilities. Significant increases in defense expenditures during the last three years did improve dramatically the Army's level of readiness, but congressional decisions concerning resource constraints meant the Army judiciously and economically would have to balance the various elements of readiness (such as personnel, training, force structure, equipment, modernization, sustainment, and strategic mobility) to extract full value for each dollar spent.

Improved personnel readiness and increased personnel quality characterized the Army during the year. Gains in the number of high test-score recruits and the percentage of recruits with high school diplomas were especially noteworthy. Enlistment bonuses, the Army College Fund, and increased recruiting resources and expertise were instrumental in these gains. Higher levels of training along with lower levels of indiscipline further demonstrated personnel quality and stability. The New Manning System exerted a positive effect on cohesion and stability at the unit level during the year. Reserve component personnel readiness also improved during the period because of better recruiting procedures, improved incentives for reservists, and increased full-time, active duty manning.

The Army's individual and unit training programs during the year enhanced training readiness. New exercise ranges for the Abrams tank and Bradley fighting vehicle appeared in the United States and overseas as part of the FY84 funding for the $109 million range modernization program, nearly four times the comparable figure for 1982. Exercises by operational units at the NTC increased, allowing more objective assessments of unit training readiness concomitantly with improvement of unit leader proficiency and cohesion. Fiscal year 1984 also witnessed 962 reserve component units receiving overseas deployment training-quadrupling

[54]

the FY 81 level. This underlined the Army's increased reliance on reserve components in the Total Army concept. Army trainers promulgated the Standards in Training Commission (STRAC) strategies to establish minimum essential levels of live training ammunition required to attain and sustain specified levels of individual, crew, and unit weapons proficiency for the Total Army. The concepts, including training aids, simulations, and subcaliber firing devices, provided substantial savings in the cost of training and significant improvements in training readiness.

Equipment modernization programs begun in earlier fiscal years continued apace, and more technologically sophisticated, state of the art weapon systems and equipment entered the force. By the end of FY 84, 20 tank battalions had received the Ml tank; 6 mechanized infantry battalions had been equipped with the Bradley fighting vehicle system (BFVS); 3 multiple launch rocket system (MLRS) batteries were deployed; and 22 UH-60 Black Hawk helicopter companies were fielded. These were the major new weapons systems. Numerous other new or upgraded systems were added to the Army inventory to improve combat capabilities and readiness. Paradoxically, modernization temporarily degrades readiness because new weapon systems must have a break-in period to identify potential problems and to train personnel in the operation and maintenance of the modern equipment. Spare parts for the new items are usually in short supply compared with established systems. However, readiness does increase as personnel become more proficient in using and caring for these systems.

Of all elements constituting readiness, sustainment is the most apparent as an indicator of preparedness. The layman understands that, lacking sufficient levels of ammunition, fuel, spare parts, and other materiel, an army will grind to a halt in combat. According to Ambassador Robert W. Komer in an article in the Armed Forces Journal International (Dec 84), PRESSURE POINT 84, a JCS-sponsored and directed exercise, demonstrated that United States forces had sufficient materiel and ammunition stockpiled to fight one major war, in this case, Korea, for a limited time. The issue of DOD sustainment readiness remained highly controversial throughout the year as Congress, the press, the services, and commentators widely debated, analyzed, and discussed the Army's level of preparedness. Sustainment readiness costs a large amount of money to maintain reserve stocks. The Department of Defense mandated that the Army maintain a 60-day reserve of munitions. However, Dr. Richard Delauer, Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering (USDRE), stated that the emphasis on the newer, increased autho-

[55]

rized levels of ammunition stocks shortchanged other vital items of supply. As an example, he observed that if the Army met the 60-day goal it would still have "only two days of hospitals" (AFJ, Dec 84) . He noted further that if the requirement was reduced to a 55-day level, the Army would have $7 billion available for other purposes. To meet DOD-ordered stockpile requirements and to keep production facilities operating, the Army continued to purchase older munitions at several times the unit cost of newer, more effective ammunition, which could be manufactured on a large scale in the following year.

Another important issue was unit readiness. A unit that met the old 1979 standard 30-day level, heretofore classified as combat ready, suddenly fell to a marginally ready classification in 1984. At a 6 March press conference, General John W. Vessey, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, acknowledged that American forces in Europe had "43 days ammunition on the ground." (AFJ, Apr 84) Although various news accounts reported that many combat units lagged behind 1979 standards even after significant defense spending, it must be noted that many of these units were affected by the radical change in criteria used to measure readiness. General Vessey, in reply, stated that the increase in ammunition stockpiles was one indication that "by any common sense measure that American people can understand, the force is far readier that it was three years ago." (AFJ, Apr 84) He also pointed out that spending on munitions had tripled since 1980, increasing both Army and Air Force inventories by close to 20 percent. However, the Army still had significant shortfalls of secondary war reserve items, such as reparable components and consumable spare parts. Certain analysts, both within and outside DOD, blamed the shortfalls of pre-positioned stocks for rapid deployment forces, another sustainment readiness category, on congressional parsimony.

The Surveys and Investigations Staff of the House Appropriations Committee issued a report in 1983 decrying the UH-60 Black Hawk spare parts problems and alleging it had seriously impaired mission readiness. Mr. Joseph P. Cribbins, chief of the Army's Aviation Logistics Office, countered that aircraft readiness was at its highest level since the Vietnam War and that spare parts shortages for the UH-60 existed only during the early phases of fielding the new weapon. During FY 84, the helicopter had the highest peacetime readiness rates ever attained. The flying hour program will reach its plateau in 1988 and spare parts to support that level of operation are stated to be available in 1986.

In Europe, one problem with sustainment readiness concerned the preparedness of our NATO allies. Although U.S. forces do have

[56]

sufficient stockpiles to sustain a high-intensity, conventional European war, our allies lack this capability, thereby downgrading overall NATO combat preparedness. NATO allies' infrastructure spending on forward-storage sites for ground forces munitions has also been minimal. These two developments led Senator Sam Nunn (D-Ga.) to offer an amendment to withdraw American troops if our NATO allies did not increase war stocks and NATO infrastructure spending.

Overall, though, the Army made substantial improvements in sustainment readiness through additional funding for POMCUS, war reserve stocks, and depot maintenance. The improved stock levels of POMCUS materiel and equipment, for example, contributed to the general heightened preparedness by reducing wartime airlift requirements and deployment times.

Army planners expanded the role of reserve components in Total Army readiness by increasing National Guard and Army Reserve readiness. The Army issued over $400 million of new equipment to reserve and Guard units in FY 84 and committed over $1.4 billion worth for issue in FY 85. More demanding missions for reserve units meant a closer alignment with active component units through the CAPSTONE program. CAPSTONE placed increased priority on reserve forces' readiness to improve Total Army readiness by increasing the number of combat ready forces available to meet worldwide requirements and contingencies.

Critics observed that not all Army units needed to be at a high state of readiness, because many could not be deployed for weeks due to a shortage of airlift and sealift capability. Reserve units expected to be deployed quickly under the CAPSTONE program found this particularly true. Ambassador Komer, a former Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, pointed out that in FY 84 the United States had more active forces within CONUS than could be deployed in time for effective deterrence or defense in many areas of possible conflict. Although the Reagan administration did increase spending to acquire more strategic lift, even this procurement will still fall short of estimated minimum requirements for 1990. General improvements in overall Army readiness were degraded by an inability to deploy rapidly these improved forces as needed to meet contingencies.

Nowhere was this problem more acute than in Southwest Asia, where a lack of forward basing further complicated matters. A major cause of this significant strategic disadvantage was the reluctance of Persian Gulf governments to allow the United States to build permanent facilities and pre-position materiel and equipment. Another significant factor was low congressional funding for

[57]

the construction of forward bases, even in areas where the host country agreed. Again, ground forces stood ready but could not effectively respond to contingencies for lack of strategic mobility and, in this case, forward basing.

Initiatives or completion of several programs improved readiness management. One Army initiative was the development, after two years of work, of a method to measure changes in unit war-fighting capability over time. Called Measuring Improved Capability of Army Forces (MICAF), the system revealed that the Army's twenty-four divisions increased their war-fighting capability by 18 percent from FY 80 to FY 84 and by 6 percent in FY 84 alone. The Army also started an "ERG-A Fix" project, which identified units rated C-4 for equipment on hand and listed the minimum resources needed to raise the rating to C-3. The Army initiated several other readiness management projects during the fiscal year, including the Master Priority Integration (MPI) system, and the Logistics Readiness Rating Report (LR3). Although General Vessey stated that he was "never satisfied or comfortable" with the Army's readiness and that "we [the Army] are not inhibited by lack of room for improvement" (AFJ, Apr 84), he believed that the Army was a stronger and better equipped force in FY84 than at any other time in recent history. It also continued to work out solutions for improvements, such as spare parts and strategic mobility, that degraded the general combat readiness level of the Army's operational forces.

The major tenet of United States post World War II strategy was the deterrence of war. The military services played a major role in this by confronting would-be aggressors with a three-pronged threat: first, that the defenses would stop the aggressor; second, that hostilities could escalate in ways contrary to the aggressor's assumptions; and third, that the United States would retaliate against, and cause substantial damage to, the aggressor's national interests. The United States, with vital interests, commitments, and obligations in Western Europe, Southwest Asia, and East Asia, maintained large numbers of forward-deployed forces in these regions to support America's deterrence defense strategy. Indeed, forward basing has been a touch stone of our national defense policy since 1945. The Army's major role in these joint forward deployments was to provide a timely response and forward barrier to prevent the loss of territory that would be difficult to recover once lost to aggressors. During FY 84, 43 percent of the Army's active components were deployed overseas.

[58]

The United States also had alliances with various nations worldwide, but especially within the areas identified above, to preserve peace and freedom. Our allies' contributions did, to an extent, reduce the size of the American military and fiscal contribution overseas. Conversely, combined operations increased the need for training in interoperability, providing security assistance, and sharing technological advances. Alliances were vital because the United States and its allies, individually, could not match the quantitative superiority of the Soviet Union and its allies.

The NATO Alliance, a keystone of United States foreign policy, remained the principal arena for the Army's operational planning. FM 100-5, the embodiment of AirLand Battle doctrine, was principally written for combat operations within the NATO theater against Warsaw Pact aggression. The United States not only saw NATO as a primary security concern, but also as an area sharing its political, moral, and social values and ideals. To deter Warsaw Pact aggression and to protect these vital U.S. interests, the NATO Alliance fielded about 750,000 personnel stationed in Germany, including more than 200,000 soldiers of the U.S. Army.

The United States Army, Europe (USAREUR), had peacetime control over all American ground elements in central Europe, including the Berlin Brigade and the U.S. Army Southern European Task Force (SETAF), an airborne infantry battalion located in Italy, which is a part of the Allied Command Europe Mobile Force. USAREUR was responsible for manning, equipping, and training Army units under its control. During a crisis or war, the combat elements would be transferred to NATO command. However, USAREUR would continue its logistical and administrative support to these units.

During peacetime, Central (European) Army Group (CENTAG) acted as an international planning staff with no combat forces under its control. It developed and tested plans and procedures for the command and control of combat forces within the CENTAG area of responsibility. The arrangement differed markedly from past wars, when the United States and allies determined command and control responsibilities and procedures after the onset of war. The current arrangements capitalized on lessons learned from the past to improve interoperability and accelerate the transition from a peacetime to a wartime footing. This was especially critical given the potential speed and violence of a Warsaw Pact strike. CENTAG demonstrated through several tests and exercises that its plans and procedures were workable.

[59]

USAREUR forces within the Federal Republic of Germany totaled two corps-each composed of one armored division, one mechanized infantry division, and one armored regiment. Other maneuver units were three separate mechanized infantry brigades (one being disbanded), a separate field artillery brigade equipped with Pershing surface-to-surface missiles, and an air defense command. The Berlin Brigade and the SETAF airborne infantry battalion rounded out the combat forces. The 200,000-plus U.S. soldiers garrisoned in West Germany made the United States the second largest force following that of the Federal Republic of Germany's Bundeswehr.

By all measurements, the units in USAREUR attained their highest level of readiness since the United States withdrawal from Vietnam in 1972. Over the past several years improvements were noticeable in more frequent and more realistic training; heightened unit cohesion through the introduction of the New Manning System; and fielding of new or upgraded weapons systems. Equipment readiness, while showing improvement, continued to be a problem area as shortages of spare parts and qualified maintenance personnel existed. Nevertheless, the land forces under USAREUR control modernized their equipment and increased their level of combat readiness.

One aspect of USAREUR modernization was the wholesale replacement of armor assets as the Ml Abrams main battle tank as well as the Bradley M2 infantry and M3 cavalry fighting vehicles (CFVs) entered the force. The latter will give the United States a mobile, combined arms capability similar to that enjoyed by the Bundeswehr and Warsaw Pact armies. In addition, the introduction of the TOW-II significantly improved the antitank guided missile inventory. The MLRS (multiple launch rocket system) also appeared in U.S. units during the year, which greatly enhanced USAREUR's artillery firepower.

The NATO Alliance lacks enough deployed standing forces to defeat outright foreign aggression. The United States must, for instance, rely on a massive air and sealift of active and reserve units to reinforce Central Europe. The Supreme Allied Commander, Europe, Rapid Deployment Plan committed the U.S. to provide a ground force of 10 divisions within 10 days of mobilization. Four of these divisions were already in Germany, meaning that 6 must deploy from CONUS. In supporting this commitment, the United States Army stationed certain units in CONUS and stored their equipment and materiel in POMCUS sets in Europe. Four sets were already in place in Germany and two others, in the Benelux coun-

[60]

tries, were being filled. With one other site in North European Army Group, these two Benelux POMCUS sets support U.S. III Corps reinforcing units, while the remainder are dedicated to CENTAG reinforcements. NATO countries test this rapid deployment and use of POMCUS sets through several mobilization, deployment, and field training exercises annually. REFORGER and accompanying exercises were the major tests of the Army's plans and procedures.

The United States recognized that its strategic lift was insufficient to transport 10 divisions within 10 days. Five NATO allies (the Federal Republic of Germany, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg) were asked for logistical support in time of crisis. These allies agreed and produced bilateral agreements with the United States. The Federal Republic of Germany and the United States signed a Wartime Host-Nation Support (WHNS) Agreement in April 1982 that served as a model for future WRNS agreements such as the one signed by the Federal Republic of Germany and the United Kingdom in December 1983.

NATO was the primary focus of U.S. foreign and defense policies. This emphasis elevated certain aspects of our military relationship with our NATO allies into highly controversial issues. Such strategic topics as the TRIAD (strategic nuclear, theater nuclear, and conventional forces) defense strategy, flexible response, forward defense, burden sharing, and force goals were usually guaranteed to produce emotional responses. The past several years saw the dramatic rise of antinuclear advocates who, while primarily opposed to the commercial use of nuclear power, were also vocal against the nuclear arsenal. Representation on these groups was multinational, including those NATO countries committed to a defense of Central Europe, and complicated defense planning as they injected populist issues and political rhetoric into the equation.

The public debate on the risks of using nuclear weapons, sparked by these advocates, led NATO planners to reexamine methods for reducing NATO's dependence upon these weapons for defense and deterrence and for strengthening the conventional sector of NATO's defense to raise the nuclear threshold and reduce the likelihood of a nuclear exchange. However, this reassessment did not constitute an elimination of a reliance on tactical nuclear weapons to deter aggression.

The United States strategy of deterrence, based originally on U.S. nuclear superiority and subsequently on nuclear parity, was one ingredient that maintained peace in Europe for forty years. With the fielding of tactical nuclear weapons, the Army adopted a flexible response concept for defense, which allowed for three re-

[61]

sponses to enemy aggression: direct defense, deliberate escalation, and general nuclear response. An important aspect of NATO's flexible response strategy was the inherent option to escalate to first use of nuclear weapons if the first option failed. The point at which nuclear weapons are first used is the nuclear threshold.

The lynchpin of deterrence remained a nuclear arsenal that confronted the potential aggressor with unacceptable losses that negated any potential aggressor gains or might escalate to a full-scale nuclear exchange. Several high-ranking officers, including Lt. Gen. James. E Hollingsworth and General Bernard W Rogers, analyzed flexible response and found that the Army's position had eroded over the past twenty years. "To achieve credible deterrence," stated General Rogers, Supreme Allied Commander, Europe (SACEUR), "flexible response must be supported by adequate military capability for each leg of the triad forces it requires: . . . But today we find NATO's deterrence jeopardized because it has been surpassed by the Warsaw Pact in all three categories." (Defense 84, June)

During FY 84, according to General Rogers, the United States and the United Kingdom worked at improving the deterrent value of their strategic nuclear forces, the first part of the TRIAD defense strategy. While NATO also planned to deploy various intermediate-range nuclear missiles on the European continent to counter the Soviet buildup, concurrently NATO ministers conducted arms reduction talks with the Soviets aimed at redressing the balance of nuclear weapons. The allied ground-based inventory included 18 French surface-to-surface missiles and the 57 United States ground-launched cruise missiles (GLOM) and Pershing II missiles being fielded. The main targets for these weapons were the Soviet military forces in and beyond the Western Military Districts, which would reinforce first echelon units engaged in an offensive against NATO forces. Defense analysts believed that the threat of first-use nuclear weapons option would deter aggression by presenting incalculable risks to the aggressor. Until recently, NATO let the Warsaw Pact in the number of short-range nuclear warheads and delivery systems that made up the second part of NATO's TRIAD defense strategy. While the Soviets had several weapon systems that could use artillery nuclear warheads, they did not deploy them into forward areas of Eastern Europe. However, since 1975, the Soviets have deployed five new systems there. In FY 84, the Warsaw Pact fielded at least as many tactical nuclear-capable artillery tubes as the NATO forces. The Soviets also had a considerable advantage in missile-delivered warheads. On 3 July 1983, the cancellation by the U.S. Senate of the W-82 nuclear warhead for the U.S. 155-mm. howitzer

[62]

complicated the tactical nuclear equation. This artillery round was designed to modernize the United States tactical nuclear forces, and its abrogation indicated to NATO and Warsaw Pact ministers as well as military planners that Congress was moving away from a dependence upon nuclear forces for European deterrence. The October 1983 Montebello conference of NATO's Nuclear Planning Group of ministers called for a unilateral withdrawal of 1,400 nuclear weapons, mostly short-range systems, from the NATO inventory. This position also suggested a shift from a dependence upon nuclear deterrence to one based upon conventional forces without nuclear weapons as a possible threat.

President Reagan, among others, believed that U.S. and NATO conventional forces in Europe had to be modernized as well as increased in size and capability, but did not believe that conventional forces alone could completely replace the nuclear deterrent. In a 12 September 1984 letter to Congress, the President wrote that NATO had to "continue to maintain a credible nuclear deterrent." (Department of State Bulletin, Nov 84)

Recently, defense analysts have debated, discussed, and critiqued the effectiveness and capability of our conventional forces in Europe, in particular, and NATO's conventional force structure, in general, based upon concerns over these forces' ability to fulfill their missions under the flexible response and forward defense plans. Both proponents and critics of current force structure strength and organization compared NATO's resources and abilities against those of the Warsaw Pact. While the number of divisions and manpower strengths served as focal points, at least one analyst noted that although these figures remained fairly constant over the last several decades they concealed the massive increase in new equipment and consequent modernization of the Warsaw Pact ground forces.

General Rogers asserted that the Warsaw Pact was eliminating most of its deficiencies, especially in the field of logistics. The Warsaw Pact's level of sustainment was sufficient to maintain 90 divisions in combat operations for more than 60 days. NATO could not match Warsaw Pact forces on a one-to-one basis, but analysts and planners believed that allied technological superiority served as a force multiplier and evened the odds. Others, less sanguine, emphasized the massive increase in technologically sophisticated weaponry and equipment of Warsaw Pact forces to highlight their contention that the technological edge was thinner than previously thought.

General Rogers, SACEUR, repeatedly requested a bolstering of his conventional forces. He called on the U.S. Congress to strengthen the Army's forces as a model and incentive to our allies to do likewise

[63]

and to provide an additional deterrence based upon conventional forces. General Rogers pointed out that conventional forces needed to be "strong enough to give us high confidence that we can preserve the integrity of the Allied Command Europe's conventional defense by enough for NATO to make an orderly and deliberate consideration of escalatory responses to try to convince the aggressor to cease his attack." (Defense 84, June) The road to a credible conventional deterrence remained extremely long and difficult. A major recurring problem was sustainment. NATO lacked adequate manpower, war reserve materiel, and ammunition to maintain its combat power for a protracted length of time.

With the introduction of units employing new, advanced weapon systems needed to modernize the Army's conventional forces in Europe-to enhance the conventional deterrence-the personnel strength of USAREUR increased, since no personnel reductions were planned for other units. However, congressionally mandated manpower ceilings for European troop strength resulted in compromises. An initial decision was the deactivation of the 4th Brigade, 4th Infantry Division (Mechanized). Other units were considered for dual basing, which meant several units would be returned to the United States for stationing, while their associated equipment and materiel would remain in Europe. Though the stockage level of war reserve materiel increased during the year, it fell far short of meeting sustainment goals. The POMCUS equipment and materiel stockage rate proceeded slowly.

The U.S. Army also faced deficiencies in the detection of, protection from, and means to deter the use of chemical weapons, an area in which the Warsaw Pact forces enjoyed a distinct superiority. Although several NATO countries had acceptable defensive chemical capability, none equaled the wide range and capability possessed by the Warsaw Pact ground forces. Meanwhile, Congress, regarding the U.S. chemical weapon stockpile as sufficient, was reluctant to provide funds for improving or increasing the American offensive capability in such weapons. The stockpiled chemical weapons were nearing obsolescence because of deterioration in both the warhead and propellant.

General Rogers also identified other problem areas within Allied Command, Europe. These included intelligence operations, logistics systems, air defense, command and control, and the number of reserves available for mobilization. He had two main areas of concern. His first was to bring the forces already committed to NATO up to peacetime standards in equipment, sustainment, manning, training, and reinforcement capabilities. Second, he wanted to ac-

[64]

celerate the modernization of those forces to maintain NATO's vital technological superiority over Warsaw Pact forces.

Congress, as well as the news media, used figures such as those in Table 1 to criticize NATO allies for failing to pay their own way while enjoying U.S. protection. Proposals for the reduction of American troop strength in Europe if the allies did not substantially increase defense spending to the 3 percent level were heard in Congress. Senator Nunn proposed an amendment to the FY 85 defense authorization bill in June that would reduce the present 326,000 total DOD troop strength by 90,000 if the allies did not increase defense spending. The Senate, after a close vote (55-41) , tabled the amendment. Nunn's amendment very specifically called for improvements in NATO's conventional forces to improve their level of effectiveness above that of a "tripwire". If this was not done, the United States would decrease its ground forces to a "tripwire" level also. According to Nunn this meant bringing home 90,000 soldiers. To stop such a huge withdrawal of U.S. forces the NATO allies have to complete certain programs, which Nunn estimated would cost $6 billion over five years, to increase their ammunition stockpiles to the level announced as official NATO policy. The infrastructure program was highly successful during FY 84 as it handled very specific items, such as fixed installations or facilities needed for developing and using combat forces, and received improved funding from our NATO allies.

TABLE 1 - PERCENT CHANGES IN NATO SPENDING IN CONSTANT PRICES, 1971-1982

| Country | 1971-78 | 1977-78 | 1978-79 | 1979-80 | 1980-81 | 1981-82 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium | 4.75 | 6.7 | 4.5 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 0.2 |

| Canada | 2.72 | -0.2 | 0.9 | -0.9 | 5.1 | 3.0 |

| Denmark | 2.80 | 3.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.1 |

| France | 3.17 | 4.9 | 3.0 | 2.5 | 3.9 | 3.5 |

| Great Britain | 1.62 | -0.3 | 3.9 | 3.0 | 2.7 | 2.1 |

| Greece | 5.49 | -3.2 | 0.5 | -2.9 | -8.8 | 5.6 |

| Italy | 3.08 | 3.2 | 0.8 | 2.6 | 4.9 | -1.2 |

| Luxembourg | 6.28 | 7.9 | 1.4 | 3.5 | 16.3 | 7.1 |

| Netherlands | 3.28 | -5.3 | 3.5 | 3.9 | -1.5 | 2.3 |

| Non-U.S. NATO |

- |

2.1 | 2.7 | 2.2 | 2.6 | 2.2 |

| Norway | 2.99 | 7.7 | 2.8 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 2.5 |

| Portugal | -6.01 | 1.7 | 12.3 | 2.9 | 10.1 | 2.8 |

| Turkey | 7.80 | 0.0 | 2.1 | 2.6 | 2.0 | 3.1 |

| United States | -2.69 | 1.5 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 4.9 | 5.4 |

| West Germany | 2.91 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

Source: James R. Golden, "NATO Burden Sharing: Risks and Opportunities," The Washington Papers/96, Volume X, 1983, p. 51.

[65]

The United States and its NATO allies continued, during FY 84, to demonstrate a commitment to a strong deterrence and common defense. This was done in spite of criticism of their defense strategy (flexible response and deep strike based upon AirLand Battle); of the strength and capability of their conventional forces; and of perceived inequities in sharing the cost of their defense. While the forces were not as large as in the past, their capability had increased considerably over the past four years. However, with the economic problems then prevalent and predicted, that capability would increase slowly during the next several years. During the year NATO members worked diligently to solve the problems of interoperability and standardization of forces, weapons, and materiel. The U.S. Army considered the cooperative development of several weapon systems with European companies, and joint deployment of weapons systems such as MLRS were completed. However, Warsaw Pact capabilities also continued to increase. At the end of FY 84, Congress, the Army and its sister services, the news media, and other defense and foreign affairs specialists still debated, discussed, and offered plans to reverse the decline.

Post World War II Southwest Asia has been racked by conflicts and crises, and recent events-such as the Iran-Iraq war, internecine fighting in Lebanon, ongoing tensions between Israel and its neighbors, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and the rise of radical Islamic fundamentalist groups within several Arab countries-demonstrated a continuation of such trends. As one commentator remarked, "Today the region displays a wide and uneven range of economic and social development. It is marked by great ethnic, religious, and political diversity, reflecting its extraordinary history and capable of producing tensions which often result in armed conflict." (AFJ, Oct 84)

United States interests in Southwest Asia fell into three categories. The first was oil. Although the United States sharply reduced its dependence upon Arabian oil, our allies still depended on resources from this region. Second, the region's central location bridging Europe and Asia demanded that the United States extend its influence there to counter possible Soviet plans to expand. Finally, the United States continued to support the state of Israel and desired to ease or solve Arab-Israeli problems.

The United States had vital interests in Southwest Asia. Regional political stability as well as countering an increasingly more visible

[66]

Soviet influence were basic strategic goals. The downfall of the Shah of Iran and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, both in 1979, forced the United States and its allies to conclude that they lacked the military capability, either in place or rapidly available, to achieve either goal. Therefore, President Jimmy Cater, in March 1980, established the Rapid Deployment Joint Task- Force (RDJTF) to provide an immediately available capability to confront elements promoting instability. Interservice rivalries and assignment to a region already divided between two major commands (European and Pacific) plagued the RDJTF. To solve these problems and to improve the American military capability in Southwest Asia, President Reagan established the United States Central Command (USCENTCOM) on I January 1983 with its headquarters at MacDill Air Force Base, Florida. USCENTCOM assumed responsibility for an area encompassing Southwest Asia, and including Egypt, Ethiopia, Somali, Kenya, Sudan, Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. USCENTCOM's mission was based upon American interests in the region and assumptions planners made concerning events likely to occur or to continue in Southwest Asia. The primary mission was to deter any type of overt hostilities, to include a nuclear conflict or general warfare with the Soviet Union as well as any regional conflict. USCENTCOM also had the responsibility to protect the region's sources of oil and access to these resources, to confront and oppose the expansion of Soviet influence in the region, and to provide security for those nations in the region friendly to the United States. Furthermore, USCENTCOM worked to increase the area's economic development and its political stability. The primary mission was deterrence, which it sustained with political support, economic aid, combined exercises, security assistance, and training programs. If such assistance failed, then USCENTCOM, with JCS approval, could provide military support items, including advisers, tankers, reconnaissance planes, supplies, and equipment. If the President determined that this assistance too was unable to deter aggression, he could order USCENTCOM combat units into the region.

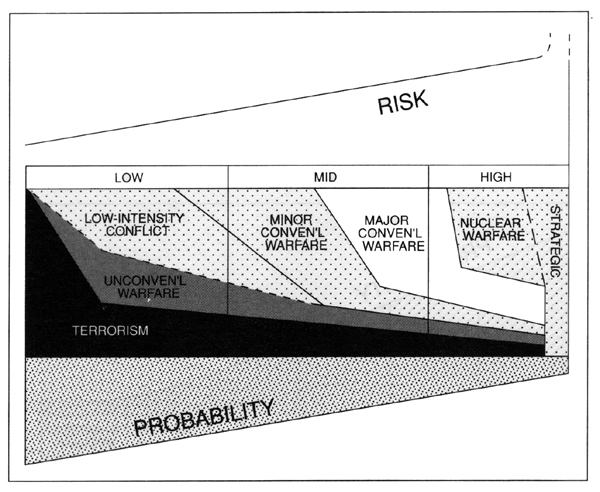

The combat and support elements of USCENTCOM were divided among the United States Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, and Special Operations Command, Central. (See Chart 3.) U.S. Army Rangers and Special Forces were included in the latter while all remaining U.S. Army forces were under the control of USARCENT (United States Army Forces, CENTCOM). USARCENT, under the command of the Third U.S. Army commander at Fort McPherson, Georgia, planned and controlled all operations of U.S. Army units assigned to the USCENTCOM theater. Army units assigned to the

[67]

CHART 3 - USCENTCOM ORGANIZATION

[68]

USCENTCOM were stationed in CONUS, except for a small forward headquarters element established in December 1983 and collocated afloat with the Middle East Force in the Persian Gulf and elements assigned to the Multinational Force and Observers (MFO) stationed in the Sinai Peninsula.

USCENTCOM's deterrent value rested on basing rights in the region. With all Southwest Asian countries extremely reluctant to allow basing within their territory and with all USCENTCOM forces, except a minuscule number of troops, located in CONUS the problem was apparent. Furthermore, the United States lacked sufficient air and sealift to transport the CONUS-based units and their equipment as well as simultaneously to move sustainment materiel to the region.

The Soviet military capability in the region included approximately thirty Army divisions stationed along the USSR's southern border and in Afghanistan. Except for the forces in Afghanistan and the nine divisions along the Soviet-Iran border, most Soviet forces were at peacetime TOE. They still enjoyed the main advantage of proximity to the heart of USCENTCOM's area of responsibility when compared to the extended 7,000-nautical-mile line of communication for American troops who would be airlifted to the region. Shipping, if available, did not reduce these staggering distances because the water route via the Suez Canal was 8,000 nautical miles, while that around the Cape of Good Hope was 12,000 nautical miles.

As the Soviet forces battle-tested their combined arms capabilities and operational doctrine in Afghanistan, USCENTCOM's Army units were just beginning to exercise and field-test AirLand Battle doctrine, as promulgated in FM 100-5. Soviet forces also possessed an advanced offensive and defensive chemical warfare capability, which was tested in most, if not all, Soviet field exercises and possibly employed operationally in Afghanistan. In contrast, the United States forces in USCENTCOM possessed no offensive and little defensive chemical capability. USCENTCOM, of course, was unable to match the Soviets' level of force-basing in the region.

Lt. Gen. Robert C. Kingston, well aware of the military threat posed by Soviet actions and troop positions in Southwest Asia, pointed out that the psychological threat of these forces and activities was often more important than actual threat of use or use of terrorism, especially when combined with Soviet-sponsored terrorism against countries friendly to the United States.

USCENTCOM forces, while forming the bulwark of security and United States strategy in Southwest Asia, received support from the military forces of the region's states. As part of its mission to improve

[69]

the defensive military stature of Southwest Asia, USCENTCOM worked to modernize and increase the size and capability of the military forces of those countries friendly to the United States through security assistance programs and training exercises such as BRIGHT STAR. U.S. Army units and the Army Corps of Engineers were heavily involved in both of these areas.

The Department of Defense planned to increase substantially the rapidly deployable forces available to its unified commands, including USCENTCOM. (See Table 2.) However, the expansion of available personnel from 222,000 to 440,000 would not raise the overall strength level of United States ground forces, establish additional units, or separate units from their present parent commands. The last stipulation had the potential to be especially troublesome for units committed to meet both NATO and USCENTCOM contingencies if crises or conflicts erupted simultaneously in both areas. Planners, at the close of FY 84, worked on solutions to this problem. Table 3 shows the anticipated increased funding for rapid deployment capabilities worldwide with USCENTCOM allocated a substantial portion.

The United States, through FY84, constructed or budgeted for support facilities worth over $1.1 billion in the region. Table 4 shows a breakdown of DOD construction funding for the rapid deployment infrastructure, which improved existing host nation facilities so that United States forces could be supported during a conflict or crisis. When the military construction program ends, it will provide storage areas for pre-positioned equipment, thus saving valuable air and sealift capacity. It also will allow support forces, especially engineer construction units, to be deployed later than planned, allowing for a faster response by combat units. Finally, it will enhance deterrence by demonstrating American commitment to our friends and allies in the region.

General Kingston, Commander in Chief, USCENTCOM, noted that his command was the only one of the unified commands with out headquarters located within the area of responsibility. This condition was a definite handicap to a timely response to conflict or crisis in the region. Kingston observed other significant and worrisome differences among his command, the European Command, and the Pacific Command. While the latter two had large force structures stationed within them, USCENTCOM had virtually none. The other commands also possessed established C 3 systems and substantial logistical networks, which USCENTCOM lacked. Finally, Kingston's command had no host nation support agreements or long-term alliances with states within his area of responsibility, as did the European and Pacific Commands.

[70]

TABLE 2 - PLANNED U.S. RAPIDLY DEPLOYABLE FORCES

| Fiscal Year 1984 | Fiscal Year 1989 | |

|---|---|---|

| Navy: | ||

| Aircraft carrier battle groups | 3 | 3 |

| Amphibious ready group1 | 1 | 1 |

| Air Force: | ||

| Tactical fighter wings 2 | 7 | 10 |

| Ground Forces: | ||

| Marine amphibious forces 3 | 1½ | 2 |

| Army combat divisions 4 | 3⅓ | 5 |

| Total personnel | 222,000 | 440,000 |

1 Typically consists of three to five amphibious ships

including an amphibious assault ship.

2 Each consists of approximately 72

aircraft.

3 Each consists of a ground combat division, a tactical

fighter wing, and sustaining support.

4 Each division consists of 16,000 to

18,000 soldiers.

Source: International Security Yearbook 1983/84, edited by Barry M. Blechman and Edward N. Luttwak, Georgetown University Center for Strategic and International Studies (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1984), p. 153.

TABLE 3 - RAPID DEPLOYMENT-RELATED PROGRAM COSTS

(In millions)

|

Fiscal Years |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1984 | 1985 | 1986 | 1987 | 1988 | 1984-88 | |

| SWA-specific | $622 | $805 | $893 | $1,204 | $852 | $4,376 |

| Other | 1,618 | 1,479 | 1,580 | 1,717 | 2,783 | 9,177 |

| Total | 2,240 | 2,284 | 2,473 | 2,921 | 3,635 | 13,553 |

TABLE 4 - MILITARY CONSTRUCTION FUNDING FOR RAPID DEPLOYMENT-RELATED FACILITIES 1

(In millions)

| Location | Fiscal Years 1980-1983 Appropriated |

|---|---|

| Egypt (Ras Banas) | $91 |

| Oman | 224 |

| Kenya | 58 |

| Somalia | 54 |

| Diego Garcia | 435 |

| Azores(Lajes) | 67 |

| Other locations | - |

| Total | 929 |

1 Does not include planning and design costs.

[71]

The picture was not, however, bleak when one compares the progress made over the course of four years. The formation of USCENTCOM provided the region's leadership with one major command to coordinate defense affairs and established a unified command to simplify the command and control procedures. The RDJTF and USCENTCOM worked diligently to improve the joint operations within the region by conducting major field exercises (e.g., BRIGHT STAR), which enhanced the general level of readiness. In addition, materiel was pre-positioned onboard ships in the region and overall air and sealift capabilities were improved.

USCENTCOM's commitment to protecting the security and stability of the region further enhanced the defense capabilities and cooperation between America's allies and nations friendly to America. Although USCENTCOM, at the end of FY 84, still faced many challenges, General Kingston believed that his command had the means to affect favorably the outcome of a regional crisis.

The Multinational Force and Observers

The Multinational Force and Observers (MFO), established on 2 August 1981 to supervise the implementation of the peace treaty between Egypt and Israel, did not, because of Soviet opposition, function as a part of the United Nations peacekeeping mission.

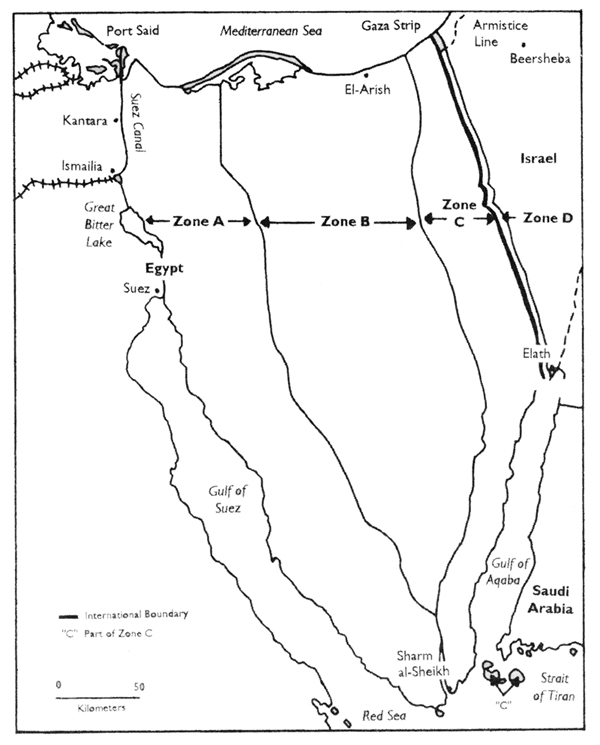

Composed of personnel from several different countries (see Table 5), the MFO's sole mission was to observe Egyptian and Israeli operations in the Sinai and to report any violations of the peace treaty to representatives of both nations. The MFO's area of operations was limited to Zone C and the international boundary. (See Map 1.) Members manned checkpoints and observation points and carried out reconnaissance patrols.

TABLE 5 - PERSONNEL STRENGTHS OF THE MFO

| Australia | 109 |

| Colombia | 502 |

| United Kingdom | 36 |

| Fiji | 500 |

| France | 35 |

| Italy | 88 |

| Netherlands | 102 |

| New Zealand | 35 |

| Norway | 4 |

| Uruguay | 75 |

| United States | 1,110 |

| Total | 2,596 |

[72]

MAP 1 - LIMITED-FORCE ZONES PROVIDED BY ISRAELI-EGYPTIAN PEACE TREATY

[73]

The United States contributed an infantry battalion (rotated semiannually between the 82d Airborne and 101st Airmobile Divisions), a logistic support unit, and a 34-man civilian observer unit to MFO. The Army battalion operated in the southern portion of Zone C. The logistic support unit, a combat service support element with 340 people assigned from numerous CONUS supply units, performed various logistical operations: 1) transporting cargo from ports to units; 2) running depots for all supply classes; 3) operating fuel points, a movement control center, medical dispensaries, and an Army post office and finance office for United States personnel; 4) hauling water and fuel; 5) supplying maintenance services; and 6) providing for the disposal of explosive ordnance. The Army, during this period, converted assignments to the logistics support unit from a TDY to a Permanent Change of Station status to provide needed continuity.

The U.S. Army forces in Sinai acted as a peacekeeping force whose political presence was more significant than its potential military effectiveness. These lightly armed units, the largest USCENTCOM force in-place, although providing valuable services to peace in the region and maintaining an American military presence, were not intended to serve as a bulwark against conflict or crisis in Southwest Asia.

PACOM, the Pacific Command, was responsible for an area of strategic significance not only to the United States but also to our NATO allies for several reasons. The Pacific rimland nations were an economic colossus that generated one-sixth of the total world trade and one-third of America's total trade. In fact, the trade between Asian/Pacific nations and the United States was larger than trade with Western Europe. European trade was also expanding rapidly in the region. While the protection of sea lanes of communication was important to the United States, maintenance of these LOCs was vital to our European allies, who depended upon raw materiels and finished goods imported from the PACOM region. Conversely our Asian/Pacific allies like Japan and Korea, as well as other Asian nations friendly to the U.S., depended upon Middle East oil transported over lengthy and vulnerable sea lanes. To support regional stability, the United States and its allies, both European and Asian, had an essential interest in supporting the independence of the region's countries, protecting their economic infrastructure, and keeping the sea lanes open to international commerce. In this basically maritime region, the U.S. Army had an active and important role. El-

[74]

ements of the seven largest armies of the world (People's Republic of China, USSR, Socialist Republic of Vietnam, India, United States, North Korea, and Republic of Korea) met in the PACOM area of responsibility, providing opportunities for local conflict or crisis which might potentially escalate into a war with United States and USSR involvement. During FY 84, the regional instability exemplified by the Socialist Republic of Vietnam's military operations in Cambodia was echoed by Communist insurgency in the Philippines, tension between the People's Republic of China and its southern and northern neighbors, and the continuing saber-rattling of the North Koreans.

For United States forces in PACOM, especially for those belonging to the Army, the area's immensity, over one-half of the earth's surface, was the significant planning factor. It was true that most of the area is ocean and thus of greater concern to the U.S. Navy. Deployment planners, however, faced great challenges in projecting power in the form of U.S. Army operations, because there were few personnel, little equipment, scarce materiel, and slender support assets located within the region close to possible areas of crisis or conflict. Therefore, the distances dictated a lift capability far in excess of that required to project similar-size forces in the same period of time to Europe. This was particularly true for transporting forces from one side of PACOM to the other. A C-141 transport plane required 24 hours to fly from California to Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean. Sealift by even the fastest ships took over 3 weeks to steam the same distance. This is an extreme example, but many forces would travel this route if they were needed in USCENTCOM. Although the distance and time for deployment to East Asia were shorter than to Southwest Asia, they still presented difficult obstacles in terms of distance to a timely and meaningful response by the United States to a crisis in that region.

Within this vast region, PACOM's primary area of concern is Northeast Asia, an area of political tensions, unresolved conflicts, tenuous diplomatic and military relationships, and propinquity to Soviet military strength. According to James A. Kelly, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense (East Asia and Pacific Affairs) "the dramatic increase of Soviet offensive power in Asia and in the Pacific and Indian Oceans is the most far-reaching military development of recent years. This assessment is valid despite America's preoccupation with Europe and the Middle East and despite the attention paid to the balance of strategic forces and the strategic uses of outer space." For the first time, wrote Kelly, "Soviet military forces in the Pacific . . . pose a significant direct threat to United States military forces, territory, and lines of communications." (Defense 84, January)

[75]

Soviet strategic, naval, and air forces posed a direct threat to PACOM nations as well as to the vital sea lanes upon which they and their trade partners depended. The Soviet military not only based their forces in PACOM's central area of concern, but also had access to two excellent ports in the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.

The United States forces in PACOM act primarily as a counterfoil to the expansion of Soviet influence, a bulwark against the Soviet military threat and intimidation, and a stabilizing influence for the region's multitudinous tensions. Currently, the United States has stopped the withdrawal of forces in overall PACOM force structure and increased the readiness, sustainment, and equipment modernization of U.S. units forward deployed in the region. While the United States recently raised funding for sustaining PACOM forces and enhancing their readiness, the force at that time was inadequate to fulfill its numerous missions without reinforcement from CONUS-based forces.

Almost all of U.S. Army forces in PACOM were dedicated to deterring aggression, mainly from the threat of North Korea. This mission has existed since the beginning of the Korean War. Most U.S. Army troops in PACOM were stationed in the Republic of Korea with close support from limited backup forces in Japan.

North Korea had the world's sixth largest army, but ranked only fortieth in population. In FY 84, the North Koreans outnumbered ROK/U.S. forces by more than 2 to 1 in armor and artillery, close to 4 to 1 in ships, and 2 to 1 in combat aircraft with almost one-half this military power located within 50 miles of the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). This quantitative advantage offset somewhat their qualitative disadvantage.

The U.S. 2d Infantry Division added vital infantry, armor, and artillery assets to Republic of Korea forces. Its deployment along the DMZ assured direct United States involvement if the North Koreans attacked across the zone. America nuclear capability added a deterrent factor that North Korea and the Soviet Union must consider. With combat operations under the control of the ROK-U.S. Combined Forces Command (CFC), United States participation was further assured. The Eighth Army would provide combat and combat service support as well as handle reinforcements to Korea before assignment to the CFC.

The 2d Division entered the final planning stages for converting mechanized and armor battalions into the Division 86 organization. In June 1984, the general support artillery battalion received a multiple-launch rocket battery. During the year, the division's armor forces traded in M48A5 tanks for newer M60A3s.

[76]

In addition over 180 new systems were added or programmed for the next several years. These included AH-1S TOW Cobra helicopters, M198 155-mm. towed howitzers (2d Division was the first overseas unit to receive these), and TACFIRE (Tactical Fire Control System). Furthermore, the division improved intelligence capabilities and enhanced range of command and control communications systems. Eventually all tactical communications equipment used by Republic of Korea and United States units will be compatible. The division also received manpower authorization increases to improve supervisory and "hard-skill" capabilities.

The Army increased funding to meet long-standing construction requirements and started a ten-year program to build, renovate, or upgrade facilities, some of which were built during the Korean War. Construction and modernization of barracks, dining halls, welfare and recreation facilities, and work areas will begin with field units. The Republic of Korea contributed to this program by building leased family housing and reducing the cost of electricity for United States dependents living off post.

One of the more significant actions taken during the fiscal year within Eighth Army to increase allied capabilities was the formation of the combined aviation force (CAF). Starting in September 1983, the 17th Aviation Group (Combat) conducted several airmobile and combat air assaults with aviation units of the Republic of Korea Army to develop procedures for a combined aviation force. Several factors pointed logically to the benefits to be gained from merging United States and Republic of Korea aviation resources. The 17th Aviation Group had a medium transport helicopter battalion with CH-47s and an assault helicopter battalion containing UH-60s and UH-1Hs. However, it lacked scout and observation helicopters as well as attack aircraft. The ROK Army maintained a substantial air assault and attack inventory, but required the lift capability of the CH-47 and UH-60. In addition, an examination of command, control, and communications (C3) as well as logistics assets found corresponding disparities that could be combined for greater effectiveness and efficiency. Another factor was the length of time it would take for aviation assets outside Korea to be deployed. During TEAM SPIRIT 84, the CAP successfully demonstrated its combined operational value to combined ROK-U.S. combat operations.

Although the Eighth Army made many improvements in readiness, sustainment, and combat capabilities, it still faced several problems. Although most experts on the Eighth Army agreed that modernization of the Army force stationed there was essential, they also emphasized that substantial shortages existed in stocks of am-

[77]

munition, war reserve materiel, and POL. Specifically, they noted that antitank and field artillery ammunition was far short of that needed to meet forward-defense requirements. They also pointed out that current lift capability was inadequate to deliver necessary sustainment items before they would be exhausted during a North Korean attack. The combat service support units within Eighth Army were sufficient to meet peacetime demands but needed force structure augmentation to handle their wartime assignments.

The 25th Infantry Division, stationed in Hawaii, continued its role as the Pacific Ground Force Reserve. The Army approved pre-positioned war reserve materiel stocks for the division during FY 84. This resource will significantly improve the division's readiness capability.

The United States countered the expansion of Soviet military forces and Soviet-supported governments in the Southern Command's (SOUTHCOM) area with a combination of military assistance and operational military forces. The U.S. Army played a major role in American policy in this region. The longest and largest role was as a planner and participant in several large-scale, multinational combined exercises in Honduras during the fiscal year. In addition, Special Forces advisers trained troops from El Salvador both in country and in Honduras.

In the midst of Honduran exercises AHUAB True I and AHUAS True II, American forces, predominantly U.S. Army units, executed an airborne/air assault operation against the island of Grenada on 25 October 1983. President Reagan ordered U.S. troops into combat in response to an "urgent, formal request from . . . the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) to assist in a joint effort to restore order and democracy on the island of Grenada." (Department of State Bulletin, Dec 83) He ordered elements of the 1st and 2d Battalions of the 75th Infantry Regiment (Ranger) and 82d Airborne Division "to protect innocent lives, including up to a thousand Americans .... to forestall further chaos . . . and to assist in the restoration of conditions of law and order and of governmental institutions." By the end of hostilities on 2 November, U.S. forces had safely evacuated 662 Americans and 92 foreign nationals, had restored order, and had begun the restoration of democratic institutions on the island. Indicative of the resistance are the statistics that United States personnel killed 24 Cuban and 45 Grenadian soldiers, wounded 29 Cuban and 337 Grenadian troops, and captured another 600 Cubans. American forces suffered 19 killed and 113

[78]

wounded in action. After 2 November all Army units, except a support element made up of XVIII Airborne Corps troops, returned to the United States. Those remaining behind maintained law and order until the reestablishment of local government authority. A more detailed account is included in Appendix B.

Nuclear, Biological, and Chemical Matters

Chemical, biological, or nuclear weapons use in warfare is considered unthinkable and abhorrent. Yet various belligerents have used all three types in the past, either as a limited means to an end or as a war-winning weapon. Because of the widespread use of chemical weapons in World War I and the limited use of biological and nuclear weapons in World War II, the United States must face the prospect that the next war may witness the reappearance of these weapons. The U.S. Army is the service responsible for most of the nuclear, biological, and chemical (NBC) research and remains the one most likely to become the major target of these weapons. Based upon its extensive work in NBC areas, the Army remained the executive agent for the programs designed for military use. Thus U.S. Army goals were to deter offensive use by aggressors, to protect personnel and equipment, and to enhance retaliatory capability. Most of the Army's actions were directed at the battlefield threat posed by the Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact allies.

The Soviets possessed an effective and efficient delivery system for chemical munitions deployed in-depth over a wide area of the battlefield. This capability was supported by the world's best trained chemical warfare force of between 50,000 and 120,000 troops. The Soviets had an extensive chemical research and development program, much of which appeared to be dedicated to offensive operations, as well as a large production base.

The United States decision unilaterally to cease production of chemical weapons in 1969 meant that the chemical warfare program deteriorated. The research, development, and acquisition base; the managerial expertise; and the training and doctrinal capability declined to an unacceptable level. In addition, the chemical ordnance manufactured before the end of production suffered from deterioration of the chemical agent, obsolescence of warheads, and lack of suitable delivery vehicles. During FY 84, the United States was in the midst of reversing this trend. General Wickham, Chief of Staff of the Army, during testimony on FY 85 DOD appropriations before the subcommittee on the Department of Defense, House Appropriations Committee, called chemical warfare the

[79]

Army's Achilles heel. He stated further that 70 to 90 percent of the country's chemical stockpile was "militarily useless" and that the United States needed "to move with alacrity in building a capability for retaliation so that we can deter chemical warfare."

The U.S. Army had a major role in improving those areas of the chemical warfare program that had deteriorated during the 1970s. Dr. Bill Richardson, Deputy Director of the U.S. Army Chemical Research and Development (R&D) Center, stated that "the biggest short-term challenge we face is fielding equipment as quickly as possible." ([ARDA] Army Research Development, and Acquisition, Mar/Apr 84.) With the Soviet use of chemical weapons in Southeast Asia and Afghanistan, the Army became aware of an increased chemical warfare threat and increased requested funding for technological work and production of binary weapons. Congress authorized the FY 84 program, but did not fund it and placed restrictions on the chemical program. One restriction eliminated additional United States stockpiling by requiring one currently serviceable shell destroyed for each new binary round manufactured. Furthermore, limitations allowed construction of production facilities and manufacture of weapons components but delayed final assembly of munitions until October 1985. The FY 85 Authorization Act asked funding for the same amount of retaliatory weapons as did the FY 84 Authorization Act but in a different manner. The U.S. Army requested only sufficient funds to begin production in the indefinite future. The authorization did not ask for all of the facilities, every component, or final assembly assets. Thus, Congress retained the prerogative to authorize and appropriate additional resources to obtain complete chemical munitions.

Another component of the U.S. Army's chemical program was the demilitarization of its unitary chemical munitions to eliminate those undeliverable, obsolete, and hazardous munitions in the Army's inventory. The Army's demilitarization program, made difficult by the combination of explosives, toxic chemicals, and contaminated components in one weapon, proved to be successful and safe. Since 1972 , the demilitarization program has rendered over 7,000 tons of chemical agents ineffective. At present, the Army plans to destroy all BZ , an obsolete incapacitating agent, all faulty chemical projectiles, and all rockets.

The 1984 defense appropriation bill required the Army to apprise Congress of its chemical defense readiness in Europe and measures needed to correct deficiencies (Senate Report 98-292, pp. 160-61) . The DCSOPS submitted a classified report assessing overall readiness and delineating equipment needs. The report

[80]

stated that while the Army had ameliorated its chemical defense posture, particularly for its European forces, a need existed to improve equipment, training, doctrine, and chemical force structure. Army leaders called also for a modernization of American chemical weapons for a viable deterrence.

The U.S. Army continued to improve NBC force design and supplement force structure to enhance its nuclear, biological, and chemical defense capability. Army planners augmented the NBC force structure with new chemical units and additional chemical specialists to provide field commanders smoke, NBC reconnaissance, and decontamination support as well as to strengthen NBC defense training. During FY 84, the Army introduced these Army 86 NBC enhancements into the Army of Excellence study. Plans were made to convert the heavy division chemical company into the new Division 86 configuration during FY 85. Meanwhile, the Army activated a decontamination team in Germany and increased the total number of active duty NBC specialists from 7,500 in FY 83 to 8,600 in FY 84.

The U.S. Army allocated $56 million in the FY 84 Operations and Maintenance, Army, program for procuring stock fund chemical defense equipment, such as NBC protective clothing, chemical agent detector kits, personal decontamination kits, and training aids, to improve training and readiness. In 1983, the Army adopted the battle dress overgarment (BDO), which combined camouflage with increased chemical protection, as the standard chemical protective overgarment. U.S. Army forces in Europe received their initial readiness issue of two sets of BDOs per soldier during FY 84.

Using $54 million of Other Procurement, Army, funds, the Army purchased NBC protective masks (M17A2 field, M24 aviator, M25 tanker), M17 lightweight decontamination systems (LDS), and modular collective protection for vehicles, shelters, and vans. The M17 LDS, designed to decontaminate vehicles and equipment rapidly with hot water applied at a high pressure, gave light division battalions and NBC companies an NBC decontamination capability. Simultaneously, the Army terminated the XM16 jet exhaust decon system UEDS) Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation program and redirected its efforts towards a more compact, less logistically burdensome system.

Faced with a highly probable use of chemical agents, the U.S. Army needed equipment to detect and identify these agents quickly. The Chemical R & D Center served as the proponent for detection equipment. The center replaced the M8 Chemical Agent Detector, which had a one- to two-minute response time, with the

[81]

significantly improved M8Al detector with a response time of three to five seconds.

The use of smoke on the battlefield is a well-known tactic. Researchers continued engineering development efforts on the XM76 infrared screening smoke grenade for use in armored vehicle smoke grenade launchers and the XM819 smoke screening cartridge to be fired from the 18-mm. United Kingdom mortar now being fielded by the U.S. Army. In January 1984, the Army conducted SMOKE WEEK VI, an exercise designed to evaluate the performance of new smoke materiel under snow and cold conditions.

Modernization of the Army's chemical munitions in FY 84 continued. The President's FY 84 Budget Request asked funding for future items whose manufacture necessitated planning and constructing facilities now to prepare for binary munition (155-mm. GB-2 artillery and BIGEYE VX bomb) production. The President, however, did not seek actual production authority, and Congress rejected the FY84 chemical modernization program. Nevertheless, the Army reorganized the binary program during the remainder of FY 84 to offset this delay and to prepare for the FY 85 budget request to Congress.