Department of the Army Historical Summary: FY 1984

4

Reserve Forces

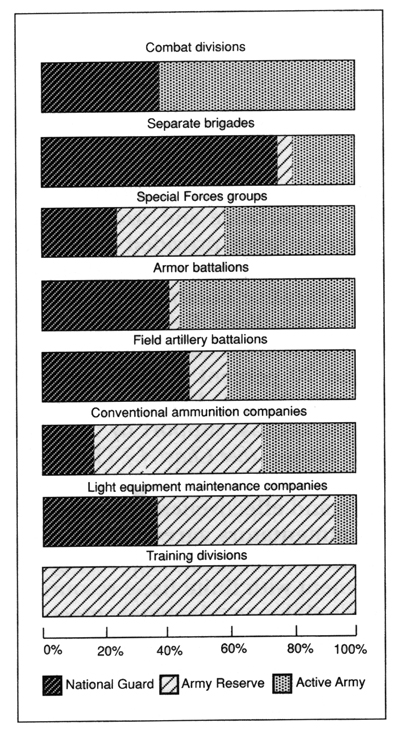

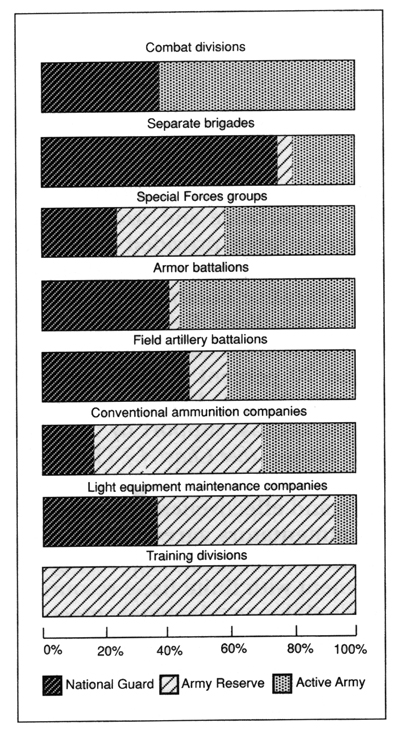

During the past year the Army National Guard and Army Reserve increased the importance and size of their contribution to the Total Army. Reserve units provided more than 50 percent of the active Army's initial combat logistical support, nine of the Army's projected twenty-five combat divisions, and a substantial portion of its infantry battalions, field artillery battalions, armored cavalry regiments, and aviation units. Approximately 46 percent of combat support and 70 percent of combat service support currently were provided by National Guard and Reserve units. Army planners will increase combat support by the reserve forces to 50 percent in the near future. (See Chart 4.) This substantial contribution remained a focal point of the debate among analysts over the organization, policy, and effectiveness of the total force.

While most commentators agreed, in theory, that the Total Army design was the best method of matching American military manpower requirement with finite fiscal resources, they disagreed over the total force's ability to adequately meet global and territorial defense commitments. Critics asserted that since reserve components trained for limited periods of time, used equipment often inferior to or incompatible with active Army units, experienced difficulty in rapidly mobilizing, and had little or no dedicated air and sealift capability to move them simultaneously with active forces, they could not be effectively or efficiently interchanged with active Army units. On the other hand, proponents insisted that the Army had made significant progress and was continuing to upgrade reserve forces to meet national commitments.

Army planners realized that the active Army could not meet major contingencies without reserve support and consequently, since 1980, have enhanced the reserve components' capabilities, missions, and readiness. Drill strength increased from 562,000 to more than 670,000, with full-time manning increasing over 35 percent. In FY 84 the reserve components received more than $900 million in new equipment and will receive $1.4 billion in FY 85 to modernize their aging equipment. In addition, planners diligently coordinated active Army and reserve units' training, war planning,

[93]

CHART 4 - PROPORTION OF ARMY RESERVE COMPONENTS IN TOTAL ARMY FORCES

Source: Reserve Forces Policy Board, Readiness Assessment of the Reserve Components, Fiscal Year 1982, Office of the Secretary of Defense, Washington, D.C., December 1982.

and exercises as the components worked together to strengthen cohesion for the Total Army.

During FY84, the Secretary of the Army and the Army Chief of Staff reaffirmed their commitments to expand the role of the reserve components in the Total Army. In his keynote speech at the annual meeting of the Association of the United States Army (AUSA) Secretary of the Army Marsh termed the increasing pre-

[94]

mium placed on the National Guard and the U.S. Army Reserve "probably the most profound change in the Army that has occurred over the last ten years."

The Army substantially strengthened the National Guard force structure in FY 84. On 25 August 1984, Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 35th (Santa Fe) Infantry Division (Mechanized) was reactivated and reorganized at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, after Army planners, in the FY 83 Army plan, identified the need for an additional heavy division. With the tradition of the 35th's outstanding World War 11 combat record to draw on, the division's major units were the 67th Infantry Brigade from Nebraska, the 69th Infantry Brigade from Kansas, and the 149th Armored Brigade from Kentucky. Existing nondivisional units will be converted and new elements established in Colorado, Kansas, Kentucky, Missouri, and Nebraska to fill out the division.

On 6 June 1984, at the D-day Commemoration in Washington, D.C., the Secretary of Defense announced that the 29th (Blue and Gray) Infantry Division (Light) would be activated in FY 86 to form the tenth National Guard division. Forty years earlier the 29th Division had stormed OMAHA Beach and gone on to distinguish itself in combat operations in northwest Europe. With initial establishment of headquarters at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, in October 1984, the 29th Division will eventually be composed of the 58th Infantry Brigade of Maryland and the 116th Infantry Brigade of Virginia.

The National Guard organized the 5th Battalion, 200th Air Defense Artillery (Roland), in New Mexico, making it the first all-weather air defense unit in the Total Army. Another unique unit, the 3d Battalion, 172d Infantry (Mountain), Vermont ARNG, was also organized with an authorized strength of 785. Furthermore, the National Guard Mountain School in Vermont trained its first class, and the Army increased the MTOE mountain infantry company enlisted strength from level three to level two. The National Guard also established two health professional detachments, one in Tennessee and the other in Connecticut. These units allowed health professionals to maintain their civilian practices with minimum disruption, while placing them in a military organization that can provide a trained and operating medical asset during mobilization.

The 155th Armored Brigade of Mississippi and the 3d Battalion, 141st Infantry, of Texas assumed roundout missions with the 1st Cavalry Division. These two actions increased the number of

[95]

brigades in roundout missions to five and battalions to seven. The National Guard reorganized the 256th Infantry Brigade, Louisiana ARNG, under a J-edition TOE to improve its capability as a roundout unit to the 5th Infantry Division. Likewise, the 2d Battalion, 136th Infantry, of Minnesota and the 3d Battalion, 141st Infantry, were reorganized for better roundout alignment with their respective active Army parent divisions. Two support hospitals were converted into evacuation hospitals and three combat support hospitals were reorganized into Mobile Army Surgical Hospitals.

The National Guard Bureau continued plans for the reorganization of eight state-operated training sites that doubled as mobilization bases. Such actions allow an efficient transition from peacetime to mobilization missions. The installation support unit established at each site during peacetime will manage training activities as well as plan for possible mobilization and deployment. The bureau also developed, validated, and submitted to Forces Command six mobilization Tables of Distribution and Allowances for State Area Commands (STARC). The bureau received twenty other mobilization TDAs for coordination and documentation during the year.

During FY 84, the National Guard Bureau successfully met the challenges posed by Army of Excellence initiatives and Army-directed force structure restrictions. The bureau remained within the dictated force structure constraints. It retained all existing units not scheduled for conversion and restructured those units that analysis classified as unnecessary. Unfortunately, the multiplicity of far-reaching actions produced serious shortfalls in authorized spaces.

As of 30 September 1984 the Army National Guard had the following major components. (See Table 6.)

TABLE 6 - ARMY NATIONAL GUARD MAJOR COMPONENTS

| 5 Infantry Divisions 1 Infantry Division (Mechanized) 2 Armored Divisions 1 Division Headquarters 10 Infantry Brigades (Separate) 8 Infantry Brigades (Mechanized) (Separate) 4 Armored Brigades (Separate) 4 Armored Cavalry Regiments 2 Special Forces Groups 1 Infantry Group (Arctic Region) 132 Separate Combat and Combat Support Battalions 18 Hospitals 760 Separate Companies and Detachments 289 Headquarters 1 |

[96]

TABLE 6 - ARMY NATIONAL GUARD MAJOR COMPONENTS - Continued

| MTOE | TFS | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 71 | GO2 | 17 | 54 |

| 61 | O63 | 59 | 2 |

| 157 | O54 | 157 | 0 |

1 Includes brigade and group headquarters for the various branches of the

Armed Forces.

2 Separate general officer headquarters.

3 Separate O6

headquarters.

4 Separate O5 headquarters.

As of 30 September 1984, the National Guard possessed the following percentages of various combat units of all Army forces. (See Table 7.)

TABLE 7 - ARMY NATIONAL GUARD COMBAT UNIT PERCENTAGES

| 36% of combat divisions 68% of separate brigades 29% of special forces groups 64% of infantry battalions 1 100% of infantry battalions (TLAT) 2 48% of infantry battalions (mechanized) 1 100% of infantry groups (scout) 43% of armored battalions 1 57% of armored cavalry regiments 50% of field artillery battalions 30% of aviation units |

1 Includes organic and separate battalions.

2 Infantry battalions that fire

the TOW antitank missile.

The Army Reserve made 215 unit changes to its force structure during FY 84: 59 activations, 14 inactivations, 101 reorganizations, and 41 authorized level of organization changes. (See Table 8.)

TABLE 8 - ARMY RESERVE FORGE STRUCTURE CHANGES

| Significant Activations:

|

1 Training Brigade 1 Medical Brigade 2 MASHs 1 Chemical Battalion 1 Signal Battalion 1 Chemical Company 1 Military Police Company 1 Maintenance Company 1 Transportation Company 6 Quartermaster Teams (water purification) |

[97]

TABLE 8 - ARMY RESERVE FORCE STRUCTURE CHANGES - Continued

| Significant Inactivations: |

2 Chemical Detachments (decon) 6 Engineer Detachments (water purification) 6 Military Police Platoons (hospital security) |

| Significant Reorganization: |

6 Station Hospitals (300 beds) 5 Medical Detachments (vet suc small) 4 Medical Detachments (vet suc large) 5 Ordnance Groups Ammo (DS/GS) 7 Ordnance HHC Battalions Ammo (DS/GS) 2 Ordnance Companies Ammo 5 Signal Companies 8 Military Police HHD Battalions 1 Military Police HHC Brigade 25 Military Police Detachments 4 Maintenance Companies 1 Transportation HHC Brigade 7 Transportation Companies |

The Army Reserve, per its projection in early FY 84, completed the transfer of the water purification mission from the Corps of Engineers to the Quartermaster Corps. It planned to increase the number and capability of roundout units in FY 85 as well as pursue an ambitious plan to add over 150 new support and service units (including chemical, maintenance, medical, and transportation) to its force structure over the next five years.

FORSCOM also activated the Fourth Army to reorganize and expand the Army's command and control capability in the mid-western United States. The Fourth Army directed reserve units stationed in Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, and Wisconsin. This activation and the reorganization of the Fifth and Sixth U.S. Armies will complete the reserve's revision of stateside command and control structure by January 1985. With these and other changes major reserve commanders will assume increased responsibility for the training and mobilization of their forces.

The Army Reserve, like the National Guard, provided a substantial portion of the Total Army's assets. This is depicted in Table 9.

[98]

TABLE 9 - RESERVE UNITS AS PERCENT OF TOTAL ARMY UNIT STRUCTURE

(Fiscal Year 1984)1

| Type of Unit | Percent of Army Structure |

|---|---|

| Training division | 100 |

| Training brigades | 100 |

| Military intelligence (strategic research and analysis) | 100 |

| Civil preparedness support detachments | 100 |

| Army Reserve schools | 100 |

| Maneuver area commands | 100 |

| Maneuver training commands | 100 |

| Railway units | 100 |

| Judge advocate general detachments | 98 |

| Civil affairs units | 97 |

| Psychological operations units | 89 |

| Smoke generator companies | 78 |

| Quartermaster petroleum, oil, and lubricant supply companies | 67 |

| Army hospitals | 65 |

| Terminal service/transfer companies | 61 |

| Services and supply capability | 59 |

| Pathfinder units | 55 |

| Conventional ammunition companies | 51 |

| Chemical decontamination companies/detachments | 46 |

| Quartermaster petroleum, oil, and lubricant operating companies | 45 |

| Watercraft units | 44 |

| Army medical units (other) 2 | 41 |

| Combat support aviation companies | 38 |

| QM engineer water supply, well drilling, purification units | 36 |

| Major logistical units 3 | 31 |

| Truck companies | 30 |

| Nondivisional bridge companies | 29 |

| Combat engineer battalions | 24 |

| Maintenance companies (direct support, general support, nondivisional) | 24 |

| Special forces groups | 22 |

| Separate combat brigades | 13 |

| Field artillery brigades, headquarters detachments | 9 |

| Field artillery battalions 2 | 9 |

| Infantry battalions 2 | 8 |

| Mechanized infantry battalions 2 | 2 |

| Armor battalions 2 | 2 |

1 Current structure as of January 1984.

2 Includes organic and separate elements.

3 Theater army area command/corps support command

headquarters company and material management center.

[99]

Strength and Personnel Management

Table 10 shows the breakdown of reserve component strength.

Army National Guard

The Army National Guard (ARNG) was one of three reserve components to reach or surpass Department of Defense-established end strength goals. Starting the fiscal year with an assigned strength of 417,791 (41,678 officers and 376,113 enlisted personnel), recruiting difficulties dropped strength to a low for the year of 413,499 in January 1984. Consequently the Guard launched a major recruiting effort that brought the end strength up to 434,702 (41,847 officers and 392,855 enlisted personnel) by the end of FY 84. Representing 100.3 percent of authorization, this was the highest strength ever attained by the Guard and surpassed its previous record set in FY 57. Average strength for the year was an unprecedented 416,521 and the net gain of 16,911 accessions represented a nearly 200 percent increase over FY 83. A major reason for the Guard's success was an aggressive recruiting program, established by the Chief of the National Guard Bureau and the Director and Deputy Director of the Army National Guard. The ARNG implemented weekly strength initiatives and emphasized strength objectives along with recommended actions in letters to the respective adjutants general. Other initiatives were developed to reduce non-ETS losses, to increase prior service enlisted accessions by 1,000 per month, and to raise career reenlistments by 15 percent.

At the beginning of the fiscal year, minority strength represented 26.6 percent of the total ARNG assigned strength. This declined to 26.4 percent by the close of the fiscal year. The 3,957 minority commissioned/warrant officers and 110,893 minority enlisted personnel present at the end of the fiscal year included a net gain of 7,751. The black officer strength remained at 4.5 percent of total officer strength, while the black enlisted strength increased to 18.5 percent of total enlisted strength. There were 1,883 black officers and 72,752 black enlisted personnel at the end of FY 84, an overall increase of 5,865. These figures represented 17.2 percent of total assigned strength.

The number of female personnel increased slightly during the fiscal year due to the significant number of women who had been serving in units later reclassified as male only. The loss of spaces in combat support units available to females impaired recruiting efforts and female strength decreased slightly to 5.2 percent of overall assigned

[100]

strength. This figure represented 2,073 commissioned/warrant officers and 20,465 enlisted personnel at the close of the fiscal year.

The inactive National Guard included 9,037 individuals (581 commissioned/warrant officers and 8,456 enlisted personnel) at the end of FY 84. They remained attached to their parent units for administrative accounting and were available for deployment when their parent units mobilized.

Enlisted personnel increased by 85,540 or 77.8 percent of the programmed objective. Prior service enlistments totaled 39,371 (78.7 percent of objective) and non-prior service enlistments were 46,169 (77.0 percent of objective). Of the total enlisted gains, 54 percent were non-prior service and 46 percent were prior service.

The quality of new recruits remained high and continued to be a major goal of the ARNG. The board surpassed the minimum recruiting standard for non-prior service high school graduates of 65 percent, which the Army established as the Total Army goal for FY 84. The percentage of high-school graduates and seniors peaked at 71.6 percent at the end of the third quarter and averaged 68.8 percent for the year. Although the Department of the Army and Congress established a ceiling of 20 percent for Test Score Category IV (scoring below the thirtieth percentile on the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery [ASVAB]) for the fiscal year, the ARNG continued its ceiling of 12 percent. Enlistment percentages in this category reached 8.5 percent-an increase over FY 83, but less than the 11.8 percent attained in FY 82. By the end of FY 84 only 6.9 percent of non-prior service enlistments fell into this category.

The ARNG, recognizing the necessity to control personnel losses, enhanced its retention program and reduced losses to a six-year low. Enlisted losses stayed below the programmed objective with an ETS loss rate of 4.8 percent, a non-ETS loss rate of 14.9 percent, and a total loss rate of 19.5 percent. The Guard added 67 Retention NCOs to the Full-Time Attrition/Retention Force to assist commanders in improving reenlistment rates. The first term extension rate was 56.6 percent; the career rate was 68 percent; and the year's total retention rate was 65.7 percent.

The Guard began a new program, the ARNG Family Program, in conjunction with the Year of the Army Family to support both mobilization readiness and to retain Guard personnel by assuring family support programs. The program received positive support from the field.

The commissioned and warrant officer strength totaled 41,847 for the fiscal year, representing 97.3 percent of the programmed objective of 43,000. Accessions from the Reserve Officers' Training

[101]

TABLE 10 - ARMY RESERVE COMPONENT PERSONNEL STRENGTHS

(End of Year/Month-in thousands)

|

Strengths |

FY 84 |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

FY 84 |

|||||||||||||||

| FY821 | FY831 | Oct 1 | Nov 1 | Dec 1 | Jan 1 | Feb 1 | Mar 1 | Apr 1 | May 1 | Jun 1 | Jul 2 | Aug 2 | Sep 2 | ||

|

Actual |

Program 3 | ||||||||||||||

| Selected Reserve Paid Strength Officer |

|||||||||||||||

| ARNG | 40 | 42 | 42 | 41 | 41 | 41 | 41 | 41 | 41 | 41 | 41 | 41 | 42 | 42 | 43 |

| USAR | 41 | 42 | 42 | 43 | 42 | 42 | 42 | 42 | 42 | 42 | 42 | 42 | 43 | 44 | 44 |

| Total | 81 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 83 | 83 | 83 | 83 | 83 | 83 | 83 | 84 | 84 | 86 | 87 |

| Enlisted | |||||||||||||||

| ARNG | 367 | 375 | 373 | 372 | 372 | 372 | 373 | 374 | 375 | 376 | 375 | 375 | 377 | 392 | 390 |

| USAR | 208 | 216 | 214 | 216 | 216 | 214 | 216 | 216 | 217 | 217 | 217 | 216 | 216 | 220 | 223 |

| Total | 575 | 591 | 588 | 588 | 588 | 586 | 588 | 590 | 592 | 593 | 591 | 591 | 593 | 612 | 613 |

| Aggregate | 656 | 675 | 672 | 672 | 671 | 669 | 672 | 673 | 674 | 676 | 674 | 674 | 678 | 698 | 700 |

| Individual Mobilization Augmentees (USAR only) 4 | |||||||||||||||

| Officer | 7.4 | 7.5 | 7.6 | 7.6 | 7.6 | 7.6 | 7.6 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 7.9 | 8.1 | 8.3 | 8.6 | 8.7 |

| Enlisted | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 2.0 |

| Aggregate | 7.8 | 8.1 | 8.2 | 8.2 | 8.3 | 8.4 | 8.4 | 8.5 | 8.9 | 9.1 | 9.4 | 9.8 | 10.4 | 10.8 | 10.7 |

[102]

|

Strengths |

FY 84 |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

FY 84 |

|||||||||||||||

| FY821 | FY831 | Oct 1 | Nov 1 | Dec 1 | Jan 1 | Feb 1 | Mar 1 | Apr 1 | May 1 | Jun 1 | Jul 2 | Aug 2 | Sep 2 | ||

|

Actual |

Program 3 | ||||||||||||||

| Individual Ready Reserve/Inactive National Guard Officer |

|||||||||||||||

| USAR | 45 | 45 | 45 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 42 | 42 | 42 |

| ARNG | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.0 |

| Enlisted | |||||||||||||||

| USAR | 174 | 201 | 206 | 207 | 208 | 210 | 213 | 216 | 217 | 218 | 221 | 225 | 233 | 235 | 213 |

| ARNG | 10.3 | 9.5 | 9.6 | 9.5 | 9.6 | 9.5 | 9.4 | 9.4 | 9.4 | 9.4 | 9.4 | 9.4 | 9.1 | 9.1 | 9.0 |

| Aggregate | 230 | 256 | 261 | 261 | 263 | 264 | 267 | 270 | 271 | 271 | 275 | 278 | 285 | 286 | 265 |

| Standby Reserve | |||||||||||||||

| Officer | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Enlisted | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | (*) | (*) | (*) | (*) | (*) | (*) | (*) | (*) | (*) | (*) | 0.1 |

| Aggregate | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| Total | 894 | 940 | 942 | 941 | 943 | 942 | 947 | 952 | 954 | 956 | 959 | 963 | 973 | 995 | 976 |

1 Source: DD-M-(M) 1147 and 1148. History (Official).

2

Unofficial-Preliminary.

3 FY 85 President's Budget-Preliminary (Submit).

4 FY 82

reflects transfer of IMAs to Selected Reserve.

NOTE: Columns may not add due to

rounding.

*Less than 50.

[103]

Corps (ROTC) reached 1,621 or 41.4 percent of total commissioned officer accessions. The Guard expected a rise of over 50 percent in the percentage of these accessions by FY 90, thereby making ROTC the largest single source for ARNG lieutenants. The State Officer Candidate Schools (SOCS) provided 1,236 accessions for 31.6 percent of commissioned accessions. The Guard believed that this percentage will decline to 23 percent in the future as a result of Army imposed SOCS accession constraints. The Guard will still use this source to provide enlisted personnel a method for achieving promotion, to supply officers to geographically remote areas of the United States, and to fulfill officer requirements for a possible mobilization.

Minority commissioned/warrant officer strength increased by 918 officers during the fiscal year and the 3,495 commissioned and 462 warrant officers represented 9.5 percent of the officer strength. The 1,883 black officers (1,737 commissioned, 146 warrant officers) made up 4.5 percent of the total officer strength. Female officer strength (1,946 commissioned and 126 warrant officers) totaled 5 percent of the officer force.

Although the Guard gained in overall basic branch officers strength, significant personnel shortages remained, particularly in specialties such as doctors, nurses, and chaplains. The Guard initiated intensive recruiting efforts in FY 84 to reduce these shortages.

The Guard's Officers Strength and Personnel Management programs redoubled their efforts to attain the professionally and educationally qualified leadership necessary for the Guard to fulfill its peace and wartime missions in the national security structure. Two significant actions were civilian education assistance programs and final coordination of the Reserve Officers Personnel Management Act (ROPMA). The latter will align reserve component officer management policies with those already in effect in the Regular Army.

The Army Vice Chief of Staff extended the Army's Continuing Education System to the reserve components to enable Guard officers to attain their mandatory educational requirements. Exact details and administration of the program remained unresolved. The Assistance for Military Professional Development program provided additional financial assistance to selected ARNG officers and SOCS candidates to assist them in achieving the increased educational requirements. This program provided as much as 75 percent of tuition as well as those laboratory fees for consumable materials used during classroom instruction and listed by the school at registration. At present the program parallels and later will amalgamate

[104]

with the Continuing Education System. Publication of the details of these two programs will appear in a circular in FY 85.

The ARNG established several civilian educational requirements for commissioned officers to increase the percentage of officers possessing baccalaureate or higher degrees above the current 53 percent. First, all commissioned officers must finish at least two years of college or equivalent by 1 October 1989. Second, all SOCS graduates must complete two years of college before appointment, beginning in 1989. Third, all officers appointed after 30 September 1983 must possess a baccalaureate degree prior to promotion to major. The ARNG established a warrant officer educational goal of an associate degree. During FY 84, 45 percent of the Guard's warrant officers met or surpassed this goal.

The Guard implemented its version of the Standard Installation/ Division Personnel Support Systems (SIDPERS) on 1 November 1984. SIDPERS-ARNG paralleled the active Army system and used Department of Defense standard data elements. It operated at the state level using changes supplied by unit or higher headquarters. With the introduction of more advanced equipment into both the active Army and ARNG SIDPERS, the Guard expected to receive computer assistance at battalion and unit level through the Tactical Army Combat Service Support Computer System.

Army Reserve

The Army Reserve increased by 8,874 to reach a total strength of 275,062 personnel at the end of the fiscal year. Although an improvement over past fiscal years, this figure was still nearly 12,600 below authorized strength or about 36,000 short of anticipated wartime requirements. All three categories of the Selected Reserve increased in strength with Individual Mobilization Augmentees (IMAs) rising by 25.1 percent to 10,847. Active Guard and Reserve programs expanded to 8,822 full-time reservists, and the troop program units added 4,362 personnel, which raised the trained in-unit strength to 80.5 percent of the wartime requirement. Approximately 30,000 of the troops carried on the rolls were undergoing training and were not suitable for deployment in case of mobilization. To counter this deficiency in deployable strength the Army Reserve established an "individual account" that will permit recruitment of as many as 10 percent more personnel than authorized. The reserve attributed much of the increase in strength to recruiting incentive programs that attracted over 15,000 high-quality soldiers for high-priority units as well as those recruits with com-

[105]

bat arms, military police, and medical skills. In addition, more than 78 percent of the reserve's non-prior service enlistees graduated from high school, well above the congressionally and DA mandated requirement.

Within the Total Army context the reserve supplies most of the post mobilization medical force, so the reserve emphasized the recruitment and retention of medical personnel during the fiscal year. The medical professional strength continued its significant growth from the previous year with physician strength at 62 percent, up from under 30 percent four years ago. The nurse strength reached 79 percent, an improvement from the 50 percent level of five years ago.

Female strength increased during the year and passed the 42,000 mark, an increase of 80 percent over the past five years. Women served in 87 percent of the units, in 80 percent of the enlisted skills, and in 95 percent of the officer skills. Minorities made up 13 percent of the officer strength and 34 percent of the enlisted strength.

The Army Reserve, in the past, always had fewer personnel serving in a full-time active duty capacity than other reserve components. In 1982, only 4 percent of its personnel were in this category. Noting a direct relationship between a unit's readiness and the number of full-time personnel, the reserve plans gradually to increase full-time strength to 10 percent of its force by the end of FY 89.

The Army established the U.S. Army Reserve Personnel Center (ARPERCEN) from elements of the U.S. Army Reserve Components Personnel and Administration Center (RCPAC). Collocated with RCPAC in St. Louis, Missouri, ARPERCEN will provide centralized command and control of Army Reserve, Individual Ready Reserve, and Standby Reserve, as well as provide for the personnel management of Individual Mobilization Augmentees and Active Guard and Reserve (AGR) personnel.

A significant problem facing the reserve components during fiscal year 1984 was the shortage of equipment, primarily that comparable to or the same as active Army equipment. Although the reserve components made improvements, much remained undone.

Army National Guard

During FY 84, the Army's massive modernization program caused a slight decrease in readiness when units converted to the J-

[106]

series of Modified Tables of Organization and Equipment (MTOE). This meant a state of unreadiness existed because AR 220-1, Unit Status Reporting, required that equipment readiness be based upon MTOE full wartime requirement. This unreadiness status affected reserve components more than active Army units since the former lacked many types of equipment. Headquarters, Department of the Army, eliminated this disparity from the Unit Reporting System by implementing an Instant Unreadiness Policy, which listed modernization items and related equipment as unreportable until fielded; gave the Chief of the National Guard the authority to declare certain materiel as unreportable under Unit Status Reporting for specified periods of time; and coordinated MTOE effective dates with the availability of resources. The Guard's Logistics Division published its first list of exempt items for unit status reporting in December 1983.

The ARNG also started the Redistribution From Army Materiel (REDFRAM) program to reduce equipment shortages. Under this program, the Guard identified and transferred equipment from low-priority, late-deploying units to higher priority units, thereby substantially improving the combat readiness of these earlier deploying units.

The Army National Guard filled the equipment needs of its units by using the Reserve Component Resource Priority List (RCRPL), which had eleven priority categories based upon Rapid Deployment Force-A (this is the highest level of readiness), NATO, and non-NATO war plan requirements. The Department of the Army ordered all Total Army components to use only the Department of the Army Master Priority List (DAMPL) as the guide. That list arranged units in an order of priority based upon arrival dates across all the war plans to which the units were assigned. The DAMPL program became effective 1 October 1984.

The ARNG planned on receiving 245 different items of equipment from the Army modernization information memorandum during FY 84. The scale of this modernization highlighted the capability of the Guard to handle the latest technology, and demonstrated an Army commitment to supply ARNG units with modern equipment to support their peacetime training and wartime missions. Further testimony to this commitment was the Army's decision to provide ARNG roundout units with the same equipment as the active parent units. Since 1982, the Army has issued Ml tanks, M60A3 tanks, Bradley fighting vehicles, and improved TOW antitank missiles to roundout units.

[107]

Equipment issued to National Guard units through normal supply channels in FY 83 was almost $100 million over the FY 82 level of $271 million. The ARNG accepted $611 million of equipment in FY 84, which included M939-series five-ton trucks, Ml tanks, M60A3 tanks, commercial utility cargo trucks, M198 howitzers, and TACFIRE computers. Fiscal year 1984 appropriations committed almost $1 billion for the procurement of ARNG equipment. Initial significant deliveries of this materiel will begin in fiscal years 1986 and 1987. Congress also provided dedicated funding to procure additional equipment such as five-ton trucks, armored personnel carriers, and tactical communications equipment. The Guard used nearby 50 percent of its dedicated funding from fiscal years 1983 and 1984 to improve communications at the division and corps level.

Although the organizational clothing and equipment improved, major challenges remained. Although Congress increased the operation and maintenance, ARNG (Operations and Maintenance, National Guard), budget request so that the Guard could increase procurement of chemical defense equipment, camouflage modules, cold weather clothing and equipment, tool and test sets, OMNG-funded medical equipment, and fire direction sets, the funding fell short of requirements and shortages of chemical defense equipment continued to plague the training and mobilization missions during FY 84.

Army Reserve

Like their counterparts in the Army National Guard, Army Reserve units did not meet prescribed readiness objectives because of a lack of sufficient modern, first line equipment. Serious shortages included heavy engineer, electronic, data processing, cryptologic, and communications equipment. The Army did apportion equipment on a first to fight, first to be equipped basis. Also, for the fourth consecutive year, Congress added funds to the Office of the Secretary of Defense budget earmarked for the sole use of the Army Reserve. The reserve used the extra $15 million granted in FY 84 to purchase communications and electronics equipment, as well as the means to transport and operate it.

Table 11 shows the status of reserve equipment as of 30 September 1984:

[108]

TABLE 11 - STATUS OF EQUIPMENT

| Value (In billions) | On Hand (Percent) | |

|---|---|---|

| Requirements (Mobilization) | $6.7 | 52 |

| Authorization | 4.7 | 74 |

| On-Hand Assets | 3.4 | |

| Mobilization Equipment Shortfall | 3.3 | |

| Peacetime Equipment Shortfall | 1.3 |

The Army Reserve received $150 million worth of major items of equipment during FY 84, more than double the $72 million of the previous fiscal year.

During FY 84, reserve units received four UH-60A Black Hawk helicopters to qualify mechanics and other maintenance personnel for repairing and maintaining the newest Army helicopter. In addition, the 101st Airmobile Division and the Army Reserve agreed that the 101st would exchange an aircraft requiring maintenance for a fully operational one from USAR stocks. This procedure enabled the reserve aircraft maintenance unit to perform a mission that met the wartime requirement, yet did not degrade either unit's readiness status. Reservists also had the satisfaction of seeing their work tested and the aircraft returned to the operational inventory because of their efforts. This idea was effective and adaptable to other equipment as well.

The Chief of Staff of the Army Award for Maintenance Excellence and the Chief, Army Reserve, Award for Excellence in Maintenance recognize those units that have the best maintenance program during the fiscal year and earn the highest score in areas such as training, innovation, readiness, management, and cost savings. The FY 84 winners were:

(a) Light Category:

Winner: 391st Engineer Company (Water Supply) Kalispell, Montana

Runner-up: 971st Medical Company (Clearing) Wichita, Kansas

(b) Intermediate Category:

Winner: 1011th Supply & Service Company (DS) Independence, Kansas

[109]

Runner-up: 163d Ordnance Company (Ammo) (DS/GS) (Conv) Santa Ana, California

(c) Heavy Category:

Winner: D Company, 411th Engineer Battalion Dydasco (USARC), Guam

Runner-up: HHC, 321st Engineer Battalion (CBT) Boise, Idaho

Reserve components require an infrastructure including offices, armories, logistical facilities, warehouses, and training areas to conduct their peacetime training for wartime missions. Such facilities require funding to buy, build, operate, and maintain.

Army National Guard

The National Guard received $67.6 million in new obligational authority for facilities and construction during FY 84. Nevertheless, a construction backlog of $825 million remained at the end of the fiscal year. One of the Guard's new management initiatives, stable annual investment for the renewal of systems, called for the assignment of priorities during budget cycles to emphasize facilities replacement projects. The Guard set a 2 percent replacement rate for all categories of facilities as its goal. The Guard awarded contracts for 98 major prior year and FY 84 projects worth $82 million and 141 minor projects totaling $14.8 million.

To meet the shortage of storage space required for the equipment and supplies of units scheduled for early deployment, the ARNG continued construction of new warehouses. Several units must deploy rapidly, so they cannot draw mobilization materiel from the normal supply system; they must maintain this mobilization materiel in warehouses close to the unit's station. This complication and the assignment of more early deployment missions to Guard units presented the Guard with a requirement for additional storage facilities.

Over the past several years, the backlog of maintenance and repair grew constantly. However, the Guard planned to reduce this to the congressionally mandated containment level of $15.2 million during fiscal year 1988 by requesting funds specifically for this in the FY 85 budget request, as well as by using the outyears program.

[110]

Army Reserve

The Army Reserve started construction of eight new replacement reserve centers and a maintenance facility, as well as modernizing and expanding ten existing centers. One of these projects gained national attention as several reserve medical units transferred from a run-down urban reserve center into a rehabilitated suburban school. The Kansas City government and the reserve derived mutual benefits from the trade. The municipal government received prime downtown development property, while the reserve quickly and inexpensively acquired a new center. In FY 85, the reserve planned to build 6 new centers and 2 field training ranges, as well as to expand 24 reserve centers.

A peacetime army must train for its wartime missions. The reserve components, meeting sixteen hours each month and two consecutive weeks during the year, have special challenges to achieve their readiness for wartime operations compared to active Army units. However, the Army staff, as well as the National Guard and Army Reserve leadership, worked diligently to increase the reserve components readiness posture through a well-planned training program to put the limited time available to best use.

Army National Guard

The National Guard Bureau established the ARNG Readiness Council in April 1984 as a quarterly forum to identify problems and recommend possible solutions. The Director, ARNG, chaired the council, which was composed of National Guard Bureau Army Directorate division chiefs and two selected state readiness officers from each CONUS Army area. The inaugural meeting was held in October 1984.

During the past several years, the Guard increased its training level to meet readiness goals for units as well as individuals. Beyond this effort, guardsmen concentrated on realistic training in a field environment duplicating combat conditions, command levels, and weapons availability insofar as possible. Therefore, the ARNG increased the level of unit training, including combined arms training at the National Training Center. Although the NTC offered the most realistic combined arms training, the Director of the Army National Guard, Maj. Gen. Herbert R. Temple, Jr., called

[111]

for the development of "local combined arms training areas to enhance this vital training element."

ARNG units participating in exercises received requisite training in combined arms operations and the implementation of mobilization plans usually unavailable in their annual training programs. The Army selected Guard units for training on the basis of their CAPSTONE alignment contingency mission. National Guard units took advantage of overseas deployment training to plan and exercise in their assigned contingency area with their wartime command unit. Beginning with 6 ARNG units in 1976, the program expanded to a scheduled 483 units and units cells in FY 85, serving in Europe, Korea, Panama, and Japan.

The National Guard Bureau designed a training strategy to prepare combat-ready components during peacetime. It used time, fuel, and ammunition to their fullest extent, while reducing wear and tear on equipment to the lowest possible level. The Guard used this strategy to employ more effectively its limited resources, thereby increasing unit readiness. The strategy, composed of three levels, coordinated training for units up to battalion level. The first level, for units up to platoon size, consisted of training devices used at the armory/garrison training area. The next step involved the construction, where necessary, of local training areas to train units through company level in combined arms live fire or MILES exercises. The final level consists of annual battalion and task force maneuvers, as well as combined arms live fire exercises conducted at major training areas.

The eastern ARNG aviation training site provided aircraft and tactical skill qualification training to 467 ARNG aviators during its first year of operation. The Guard also held four classes on Aviation Mishap Prevention and Orientation during the fiscal year. In addition, the ARNG implemented a new program standardizing the aircrew training requirements of units with similar missions within the total force. The Guard also started a program that standardized individual aviation training within the states.

Army Reserve

Army Reserve units and individuals underwent the same types of training as did those in the Army National Guard. CAPSTONE allowed units to concentrate their training on wartime missions. Emphasis was on readiness, as the 358th Civil Affairs Brigade (Norristown, Pennsylvania) demonstrated during Operation URGENT FURY The brigade and its CAPSTONE link, Headquarters, Com-

[112]

mander in Chief, Atlantic Command, worked together before, during, and following the Grenda operation. Prior association ensured that Headquarters, Atlantic Command, knew the unit to tap for civil affairs support on short notice. The first members of the brigade arrived on the island within three days of the call-up. However, the 358th Civil Affairs Brigade had exceeded CAPSTONE requirements before the Grenada operation. Besides exchanging standing operating procedures and making staff visits, the brigade assigned an officer to the command headquarters on a planning tour. Both organizations were familiar with each other and had strong personal ties in addition to the usual detailed and formal CAPSTONE relationships. Thus, the two organizations worked well together during Operation URGENT FURY.

The Army Reserve, like the National Guard, also employed Overseas Deployment Training to provide its units more realistic training. During FY 84 more than 485 units and unit cells deployed to overseas areas where they would most likely operate during wartime. In all, 6,707 reserve personnel participated in this program and the reserves planned to increase participation in FY 85. The reserves also supported growth in Overseas Deployment Training for SOUTHCOM and the Pacific. While most of the fourteen major exercises in which reserve and active Army units participated occurred in the United States, several were held overseas. These included REFORGER and WINTEX in Europe, YAMA SAKURA in Japan, and TEAM SPIRIT in Korea. Reserve units currently in the CAPSTONE program will increase their level of participation by close to 10 percent annually.

The Army Reserve initiated its Prior Service program in FY 84 to enhance unit readiness by decreasing the number of prior-service unqualified personnel in the assigned duty military occupational specialty (MOS). These prior-service trainees used unfilled TRADOC advanced individual training class seats, thus more efficiently taking advantage of training resources. Although the reserve allocated funding for 3,000 prior-service soldiers, only 1,436 actually took part during FY 84.

The Army Reserve recognized that its active duty reservists needed more training in their MOS and received additional funds in FY 84 for this. Moreover, the USAR asked for an increase in its FY 85 budget to accelerate this program.

The reserves emphasized physical fitness training, as did the other components of the Total Army. However, complete implementation of the reserve program awaited legislation that would resolve the insurance compensation and coverage problems with over-40 reservists. The reserve lacked medical and disability cover-

[113]

age for those personnel who possessed cardiovascular ailments that were discovered or aggravated during active duty physical training. Additionally, the units needed more medical screening personnel and equipment to identify these at-risk, over-40 personnel prior to their suffering injury and death.

Indicative of the high proficiency level of reservists was their showing at various competitions. The United States three-man teams finished 5th, 6th, 8th, 12th, 13th, and 15th at the 37th Annual Interallied Confederation of Reserve Officers (CIOR) Congress and military competitions held in Rome, Italy, from 20 to 28 July 1984. The U.S. novice team placed first in the novice categories while tying for first in overall marksmanship. The United States over-35 team finished second in its competition, while the United States captured first place in the first aid category. Thirtynine NATO-CIOR member nation teams participated, representing Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, Norway, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The following individuals turned in outstanding performances:

1. Maj. Jon Nealon-1st in pistol

2. 2d Lt. Larry Braaten-3d in pistol

3. Capt. Lyle Nelson-1st in submachine gun (tie)

4. Capt. Daniel Walker-3d in submachine gun (tie)

The USAR Shooting Team won the National .22-Caliber Pistol Team Championship and the National Infantry Rifle Team Championship at the United States International Shooting Championships. Out of 28 first places, the team won 12 as well as 30 of the 78 first, second, and third place medals. In addition, this event was used to select the United States Shooting Team, and seven reservists made the 22-member team. In the Olympics, reservists earned three of the six medals taken by the United States in marksmanship:

1. Capt. Edward Etzel-Gold Medal, English Matches

2. Sgt. Ruby Fox-Silver Medal, Ladies Sport Pistol

3. Capt. Wanda Jewell-Bronze medal, Ladies Standard Rifle

The public's contact with the reserve components differs from that of the active Army because the citizens often see the Guard and Army Reserve reserve in local settings assisting the civil authorities during natural disasters and civil disturbances. Further-

[114]

more, most members of the reserve components are local friends and neighbors seen daily out of uniform.

Army National Guard

Guardsmen responded to 391 call-ups in 49 states and territories, with 10,821 personnel working 107,550 man-days. Natural disasters accounted for 129 call-ups: 48 floods, 39 snow/ice storms, 22 tornadoes, 18 forest/range fires, 1 volcanic eruption, and 1 earthquake. Other emergencies included 93 medical evacuations, 62 search and rescue operations, 20 water hauls to areas affected by contamination, drought, or water systems under repair, 4 chemical spills/chemical fires, 3 power outages, and 72 miscellaneous missions.

The Guard also sent 501 personnel to assist civil authorities in eight civil disturbances in four states. These disturbances included civilian response to unpopular judicial decisions, as well as actions by dissatisfied copper mine workers and misconduct of a motorcycle gang. ARNG also planned and prepared for possible antinuclear demonstrations against several Army installations. Guardsmen also developed plans to maintain mail service in the event of a postal workers strike.

Almost 1,000 guardsmen from California and its neighboring states provided aviation and logistics aid to local authorities supporting the XXIII Olympiad in Los Angeles, California, in July and August.

Army Reserve

Army Reserve units, as well as individuals, responded to calls for assistance from civil authorities. Two representative cases involved water contamination in western Pennsylvania and an Avian flu epidemic on the East Coast.

Reserve water purification units provided potable water to the residents of McKeesport, Pennsylvania, in the late winter of 1984 when viral contaminants in the city's water supply made more than 300 people ill. The engineer units used this operation as a unit training exercise and remained on duty, under Department of the Army authority, until state agencies could assume the role.

During the year, an outbreak of Avian influenza on the East Coast threatened to destroy the region's chicken and turkey industry. Twelve reserve veterinarians volunteered their services to Army and civilian agencies to fight the epidemic. Their hard work was a significant factor in the eventual containment of the Avian influenza outbreak.

[115]

|

Go to: |

|

|

Last updated 8 March 2004 |