Strategic Background

On 4 March 1864 Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge moved from Tennessee to take command of the Confederate Department of Western Virginia. This huge command consisted of nearly 18,000 square miles of rugged terrain. It included all of Virginia west of the Blue Ridge and south of Staunton; the southern part of modern West Virginia from Greenbriar County to Kentucky; and as much of the last state as was under Confederate control. The dynamic commander's mission was to defend along a 400-mile front to assure retention of the region's assets and resources for the Confederacy.

Breckinridge's district was of vital economic and strategic importance to the Confederate war effort. Wythe County at its center contained some of the largest lead mines in the South. Almost all the Confederacy's salt was produced in nearby Saltville. The upper Shenandoah Valley was a prime source of produce and livestock. These were essential to the sustenance of Robert E. Lee's army east of the Blue Ridge, poised to defend Richmond against an expected Federal onslaught. The region further contained important railroads running through Staunton or Lynchburg. The latter line, the Virginia and Tennessee, linked the two sections of the embattled Confederacy and were of great strategic significance. The presence of Federal raiders and a partially disaffected population compounded the difficulties in assuring the security of the district.

The point to which Confederate arms had declined by the spring of 1864 may be seen in Breckinridge's being given fewer than 5,000 troops to protect this important area. Colonel John McCausland's Brigade, 1,268 strong, was at New River Narrows while Brig. Gen. John Echols with 1,769 men was based at Monroe Draught. Breckinridge further inherited two poorly organized cavalry brigades with a combined strength of about 1,800. Two artillery batteries and a staff of couriers and signalers rounded out his forces. Other troops assigned to his command were on temporary duty elsewhere. Both Brig. Gen. Gabriel C. Wharton's infantry brigade and Brig. Gen. W. E. "Grumble" Jones' cavalry brigade were absent in Tennessee. One other unit, the 45th Virginia Infantry, was at Saltville, but at first was not under Breckinridge's jurisdiction.

Undaunted, the vigorous commander immediately embarked upon a 400-mile tour of his district to assess the situation for himself. This was the first time such a tour had been carried out by any senior official and in itself was a tonic for his troops and sympathetic civilians. He recognized manpower as his first concern. Within two weeks he increased the number of effectives through better organization, reduction of details and furloughs, and enforcement of desertion and absent-without-leave policies. By the end of March, he was able to organize an additional cavalry brigade, which he placed under the command of Brig. Gen. Albert Jenkins. His tour allowed him to gain a first-hand impression of the geographic vulnerabilities of his district. He thus revised old defense plans and prepared contingencies to cover all the possible avenues of approach to the district's vitals. Breckinridge's description of the scope of the problems facing him persuaded General Lee to order the return of Wharton's and Jones' brigades to the district and the transfer of the 45th Virginia to Breckinridge's control. He had these units in hand by mid-April, generally deployed to protect the assets of Wythe County.

The former politician worked to ease the tensions further between the government and the population. Richmond had become very high-handed in its procurement practices. The district commanders often had been directed to impress produce and goods with little compensation. Also, huge quantities had been sent east with little thought for the needs of Breckinridge's district. As a result, he often found hungry units amidst plenty, with many disenchanted farmers. He ended these practices by ordering fair requisitions and by telling Richmond that his district had priority before anything would be shipped out of it. This new policy marked another improvement in morale for the troops, while it stabilized relations with the civilian populace.

Breckinridge restored leadership and direction to his command just in time. He had barely returned to his headquarters in Dublin when he began to hear rumors of Federal activity. On 27 April-he learned that a Federal column under Brig. Gen. William Averell was gathering at Logan, West Virginia, with the apparent intent of moving on Wytheville. Another Federal force was massing under Brig. Gen. George Crook at Gauley Bridge, West Virginia, which threatened to strike the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad near Dublin. A third Federal column was concentrating farther north at Martinsburg, West Virginia, under Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel, obviously preparing to move up the Valley. Breckinridge knew he had just a few days to assess the situation and to make the correct strategic decision. He had to determine the Federal intentions, identify the greatest threat, and deploy against it to achieve mass at the decisive point. Events were to prove that he made a masterful analysis.

Before discussing Breckinridge's decision, a view of the Federal moves in their greater context is necessary. All the blue forces just mentioned were under the command of Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel who had assumed command of the U.S. Department of West Virginia on 10 March. His department's mission was part of a Federal strategy developed by newly appointed General-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant. General Grant recognized that superior Federal resources had not been used effectively hitherto and likened the Federal army to a balky team with each mule going in a different direction. He saw his job as getting that mule team to pull together.

One of Grant's aides described the situation as it was in March 1864: "Grant inherited mass confusion in the Federal command when we came to Washington. There were a score of discordant armies, half a score of contrary campaigns, confusion and uncertainty in the field, doubt and dejection and sometimes despondency at home. Battles whose object none could perceive, a war whose issues none could foretell. It was chaos itself."

An expression of this chaos was that at the time of Grant's assumption the Federals had 19 independent districts, 21 independent corps, and 1 independent army, along with 13 coastal enclaves working separately with the Navy. Grant said, "My primary mission is to achieve system and discipline and consolidate and coordinate these assets and to bring pressure to bear on the Confederacy so no longer could it take advantage of interior lines." Grant thus brought greater cohesiveness to the Northern war effort. He was the first Northern leader to be able to bring the Federal preponderance in strength to bear in a unified effort. He added new dimensions to the struggle by seeing the war as more than a simple military undertaking. He reasoned that in such a thing as an insurrection, the entire population in rebellion had to be persuaded of the folly of continuing the fight. To him the Southern ability and will to fight were as valid objectives as were the Confederate armies. He added economic, political, and psychological aspects to the war that hitherto had been missing. All of them revolved around his intentions to engineer a massive continental-scale assault to overwhelm the Confederacy. As he told Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, "All our armies are to move together toward one common center; and that is the destruction of the other's will to fight."

General Grant assigned General Meade's 100,000-man Army of the Potomac to attack General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia in eastern Virginia, destroy it, and capture Richmond. Meade's force would serve also as the strategic hinge for a great pivot through Georgia by Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman's army group. Each of these units had military, economic, and psychological objectives. Their strategic flanks were to be protected by other forces: Major General Nathaniel Banks was to sally from New Orleans against Mobile Bay. In the east, Maj. Gen. Benjamin R. Butler's Army of the James was to move from Fort Monroe to Bermuda Hundred against Richmond. Meade's western flank was to be secured by Franz Sigel's activities in the Valley. Sigel was to coordinate Crook's and Averell's moves against the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad and Wytheville and to prevent Confederate reinforcements from reaching Lee. Further, Sigel planned to lead a force up the Valley to resupply the raiders and to draw off Confederates from the threatened area.

The Valley was as important to the Federals as it was to the Confederates. A corresponding communications system graced its northern parts. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad and the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal were critically important strategic routes for the Federals. Huge efforts were expended throughout the war to provide security for them. The road net in the Valley was exceptionally good; it was based on the Valley Pike, macadamized since 1840, linked with an infrastructure of good secondary roads. Not only was the place a prosperous economic unit, but also its development accommodated high-speed movement. The Blue Ridge shielded the Valley from eastern Virginia; however, ample gaps allowed easy egress and entry. Its northeastern orientation made it a natural avenue of approach into Pennsylvania or the Washington-Baltimore area. One has only to recognize that Harpers Ferry is on a parallel with Baltimore to see the significance of this topography. Conversely, Federals in the Valley threatened Lee's strategic flank through New Market Gap as well as the strategic targets of the railroads and access to the Valley's bounty.

Sigel and Grant originally intended the main effort in the Valley to be Crook's and Averell's raids. His force at Martinsburg was to serve as a distraction, with the purpose of luring the Southern defenders away from the raiders. The plan called for a movement south only about as far as Cedar Creek, north of Strasburg. This would seem to threaten Staunton, possibly pulling away its defenders, while still enabling Sigel to protect the eastern half of his department. Sigel altered the plan when he learned that the only force confronting him seemed to be Brig. Gen. John D. Imboden's small Valley District Brigade. He decided to move at least as far south as Woodstock. This, he thought, would have a greater chance of pulling Confederate defenders out of southwestern Virginia, and he intended to go on the defensive at Woodstock while sending out strong patrols. Sigel felt the deeper penetration additionally would disrupt Confederate exploitation of the Valley's resources while increasing the threat to Lee's strategic flank.

Federal forces began coming into Martinsburg during April from all over northern Virginia, West Virginia, and Maryland. On 1 May Sigel deployed his Infantry to Winchester while his cavalry moved even farther south to Strasburg and Cedar Creek. The Federals were to remain in these locations until 9 May. In the meantime General Imboden based at Mt. Crawford began to react to the changing threat. He concentrated his forces in the vicinity of Woodstock and on 2 May called out the Augusta and Rockingham County reserves. He also sent word of the situation with a request for reinforcements to General Breckinridge.

Southern response was prompt and decisive. General Lee ordered Brig. Gen. John H. Morgan's Cavalry Brigade from Tennessee to Wytheville, thus giving Breckinridge a bit more depth. He added Imboden's forces and his Valley District to Breckinridge's jurisdiction, assuring unity of command. Lee also placed the VMI Corps of Cadets at his disposal. Breckinridge watched the situation develop and decided that Sigel posed the greatest strategic threat. Therefore, on 6 May he directed Generals Echols and Wharton to concentrate their forces at Staunton; this was achieved by 12 May in a complex logistical operation using road and rail movement and supply coordination. The troops averaged twenty-one miles a day on the march.

While this was going on, General Imboden continued to develop the situation. Captain John H. McNeil with sixty men staged a spectacular raid on the Piedmont, West Virginia, rail depot on 5 May. The Georges Creek railroad bridge, 7 big machine shops, 9 locomotives, 80 freight cars, and several miles of telegraph lines were destroyed. Another 3 full freight trains were destroyed at Bloomington. The purpose of this devastation was to make Sigel detach some of his strength away from his main body of troops to protect the B & 0. As a result, he did leave more troops guarding the railroad than he had planned originally. Further, he became so sensitive to the guerrilla threat that thereafter he deployed substantial portions of his strength to protect his trains.

One of his first reactions was to send Col. Jacob Higgins and 500 men from the 22d Pennsylvania and 15th New York Cavalry Regiments from Winchester to Moorefield to try to capture McNeil. Higgins set out on 6 May, the same day Breckinridge began to concentrate his forces. General Imboden learned of Higgins' expedition, and on 8 May he moved to counter it. Leaving the 62d Virginia Mounted Infantry in Woodstock, he headed for Moorefield with the 18th and 23d Virginia Cavalries. The next day, he ambushed Higgins at Lost River Gap near Moorefield and pursued the fleeing Federals north to Old Town, Maryland. When the pursuit ended on 10 May, Higgins' force was no longer a factor.

The same day as Higgins' disaster, Sigel moved his main body from Winchester to Cedar Creek, establishing his headquarters at Belle Grove Mansion. His approach compounded with bad news for Breckinridge. The force under Brig. Gen. Albert Jenkins that he had left to confront Crook's advance was defeated at Cloyd's Mountain. Jenkins was mortally wounded and captured; however, the fighting had been so severe that Crook was not to follow through on his full objectives. Averell's attack was similarly blunted at Crockett's Cove on 10 May by John H. Morgan-Breckinridge could not know this at the time. The situation impelled him late on 10 May to order the VMI cadets to join him at Staunton. They set out the next morning, reaching Staunton late on the twelfth, averaging about seventeen miles a day.

Meanwhile, on 11 May Sigel resumed his stately passage up the Valley. He reached Woodstock that night and there learned through telegrams captured at the local office that Breckinridge was concentrating his forces against Sigel's at Staunton. This was the first firm intelligence he had received to show that he was facing more than Imboden's little force. Imboden had returned on 12 May from his triumph against Higgins and had set up defensive positions at Rude's Hill between Mt. Jackson and New Market.

Sigel reacted to a guerrilla raid on his trains at Strasburg that day by sending out another cavalry force. Two hundred men from the 1st New York Cavalry (Lincoln) under Col. William Boyd departed in a driving rainstorm for Front Royal with instructions to screen the Federal eastern flank into the Page Valley, and then to rejoin the force farther south. This detachment is an example of Sigel's pedantic approach to the situation; what Boyd could achieve away from the main body is difficult to perceive. At the same time, his departure reduced Sigel's reconnaissance capability and the size of the force at his immediate disposal.

Sigel's scouts from the 22d Pennsylvania Cavalry brushed against Imboden's positions south of Mt. Jackson on the rainy morning of 13 May. While the desultory skirmishing went on, Boyd's column had moved from Front Royal east of the Blue Ridge and reentered the Valley through Thornton Gap to Luray. It destroyed Confederate supplies in storage there, along with several wagon trains, and headed for the New Market Gap. When the Federal column reached the Gap, troops could be seen moving on the Pike below, heading south through New Market. Colonel Boyd presumed that what he saw was the head of Sigel's column. Against the advice of several officers, he ordered his column forward into the Valley.

Imboden, maintaining his hold on Rude's Hill at 1600, was surprised to see the Federal cavalry coming through the Gap. He sent the 23d Virginia Cavalry dashing through the town to hold the bridge at Smith's Creek at the base of the Gap. Meanwhile, he led the 18th Virginia Cavalry farther south, then east to penetrate the Federals' rear. His maneuver succeeded beyond every expectation. The Federals were caught strung out as they tried to cross one of the creek's meanders, and they were decimated. Within minutes, Boyd's force ceased to exist. Twenty-five men were killed, seventy-five were captured, and the remainder became desperate fugitives wandering on Massanutten Mountain. Sigel had lost another substantial part of his force with no visible gains. While Imboden was performing so effectively, Breckinridge moved his force to Harrisonburg the next day, 14 May, he came fifteen miles farther north to Lacey's Springs.

Preliminary Moves

In the meantime, Imboden was becoming fully engaged. Major Timothy Quinn with 500 cavalrymen mainly from the 1st New York (Lincoln) Cavalry had bivouacked the night of 13 May at Edinburg. Early on the fourteenth, another rainy day, he brought his force through Mt. Jackson and repaired the bridge across the Shenandoah. By noon he had forced skirmishers from the 18th Virginia Cavalry across Meem's Bottom and over Rude's Hill. The intensity of the fighting increased south of the hill as the defenders launched several charges against the advancing enemy.

Meantime, about 1100 that day, Sigel sent Col. Augustus Moor from Woodstock with the 1st West Virginia and 34th Massachusetts Infantry Regiments and Snow's Maryland Battery. Moor added the 123d Ohio to his impromptu brigade at Edinburg-it had been sent forward earlier to support the cavalry. North of Edinburg, Moor encountered some 900 cavalry under Col. John E. Wynkoop (20th Pennsylvania, 15th New York, 1st New York Lincoln and Veteran, 21st New York and Ewing's West Virginia Battery). He ordered Wynkoop and his command forward to support Quinn. These reinforcements thwarted Imboden's charges, forcing him back into New Market by about 1600, and there his artillery halted the Federal advance briefly. At 1700, the Federal infantry came up after nearly seven hours of marching with only one ten-minute break. Its added presence forced Imboden to take up positions south of the town as darkness set in.

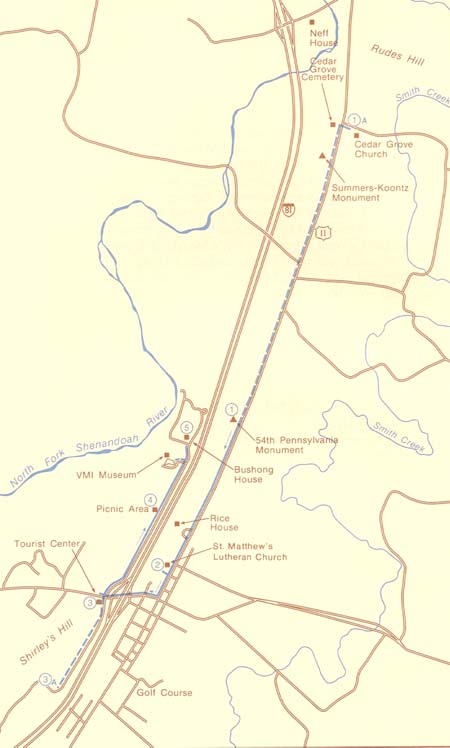

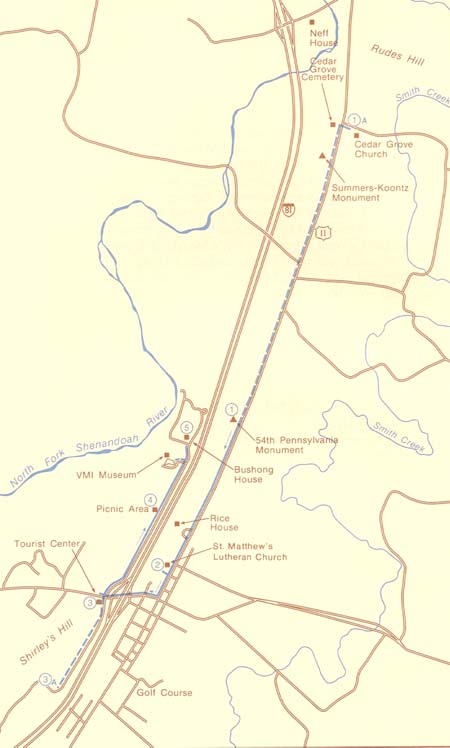

The first Confederate line was on the high ground west of New Market on a line adjacent to St. Matthew's Lutheran Church along the old River Road (now in part Breckinridge Street). The growing Federal strength caused Col. George S. Smith, commander of the 62d Virginia Mounted Infantry, to pull his men farther south to Shirley's Hill overlooking the New Market Valley. Smith placed Capt. John McClanahan's Battery (The Staunton Horse) on the hill and extended a thin line of infantry south of the town east to Smith's Creek.

The Federals established themselves in the town and in the position abandoned by Smith to the west. Two guns from Ewing's West Virginia Battery were placed on the extreme west of the line, while Snow's Maryland Battery was based near the Lutheran church. At 2000 Moor ordered the 1st West Virginia Infantry skirmishers to probe Smith's positions on Shirley's Hill. They were repulsed vigorously by Confederate pickets and their whole regiment advanced to support them, volleying in the direction of the Confederate positions. A second probe by the Mountaineers was repulsed at 2200, after which things became quiet and all contact was broken as Imboden pulled his men farther south. The closest support for Colonel Moor was the 18th Connecticut Regiment, sent to Edinburg from Woodstock by General Sigel earlier in the day. It bivouacked about a mile south of the town, fifteen miles in each direction from the larger Federal elements.

General Imboden had joined Breckinridge briefly at Lacey's Springs to explain the situation. Breckinridge decided to advance to good defensive positions south of New Market and to entice Sigel to attack him. Accordingly, he had his column moving at 0100 on the rainy morning of 15 May, the VMI cadets joining the column at 0130 after spending a gloomy night in the Mt. Tabor Church. The advance began to encounter Federal cavalry vedettes after going about six miles. These caused some delay but, more importantly, alerted Colonel Moor. Moor had his men standing to arms by 0300 and earlier had sent back word to Edinburg for the 18th Connecticut to advance. That unit began speed march so hastily about 0300 that it left Companies F and H on picket. These were drawn in at daylight and began a forced march without rest or food, running the last two miles. They arrived just in time to go into the battle at the moment of Breckinridge's attack.

By about 0600 Breckinridge's force had closed to a position just south of the county boundary (the Fairfax line). He held them there in a heavy rain for about two hours while he reconnoitered Colonel Moor's position. Then, after sunrise, he had the 18th Virginia Cavalry probe Moor's line, hoping this would precipitate a Federal attack on his prepared positions. Disappointed in this, he placed his artillery on Shirley's Hill to continue to harass the Federals and to develop the situation. By then, Colonel Moor had established his line firmly along the old River Road and around the Lutheran church. It continued to be anchored on the west by a section of Ewing's West Virginia horse gunners. East of them the line was filled by the exhausted 18th Connecticut, then the 123d Ohio, and the 1st West Virginia. Snow's Maryland Battery remained in the Lutheran cemetery, and the 34th Massachusetts briefly remained east of the Pike. Additional help was still far to the north. Brigadier General Jeremiah Sullivan left Woodstock at 0500 with the 12th West Virginia, the 54th Pennsylvania, and three batteries (von Kleiser's, Carlin's, and DuPont's). The 28th Ohio and 116th Ohio left Woodstock later at 0800 with the trains, at the me time that Sigel and his staff departed. Sigel could hear gunfire by the time he reached Edinburg, but when he caught up with Sullivan's force at Mt. Jackson he lingered for nearly an hour before continuing farther south.

Meanwhile, Breckinridge's and Moor's artillery continued to engage each other. Part of Snow's Battery had moved forward briefly until persuaded of the superiority of the Confederate positions on Shirley's Hill. Major General Julius Stahel, Sigel's cavalry chief, arrived on the scene about 0830 and, while assuming command, took exception to Moor's deployment. Perhaps he was alert to the need to close the gap between Sigel's components. His efforts, however, produced confusion and a growing sense among the troops that they were not being led well. A measure of this confusion may be seen in the experience of the 34th Massachusetts: The regiment was about to breakfast in its position east of the Lutheran church when it was ordered back to the Bushong House. Shortly after arriving, it was marched back to its starting position and ordered to send skirmishers out. No sooner was this accomplished than the unit was pulled back to an assembly area north of the present 54th Pennsylvania monument. Then it was moved westward into its final position on Bushong Hill, having marched about seven miles back and forth for no apparent purpose.

Battle Joined

By 1000 it was evident to Breckinridge that the Federals had

no intention of attacking him. Consequently, he decided to be the aggressor:

"I shall advance on him. We can attack and whip them here, and I'll do

it. " He ordered his lines forward to Shirley's Hill and maneuvered them

around to create the impression of greater strength. Finally, he aligned

them so as to appear to be

three strong battle lines, when in reality he had one line staggered in three echelons. Wharton's Brigade was in two lines: On the westernmost side was the 51st Virginia, then the 30th Virginia Battalion and Smith's 62d Virginia. To the right rear of this line was a smaller line composed of the 26th Virginia Battalion and the VMI cadets. Echols' Brigade was drawn up farther east by the Pike and south of the village. His 22d Virginia linked with the troops west of the Pike while the 23d Virginia Battalion extended east until it connected with Imboden's cavalry, which screened the area up to Smith's Creek.

After another hour of bombardment, Breckinridge's force began to move forward. The 30th Virginia preceded Wharton's Brigade as it dashed over the crest of Shirley's Hill and down into the New Market Valley. It was followed in the same informal manner by the veteran 51st and 62d Virginia. But no one had told the inexperienced cadets to proceed in open order. Consequently, they marched down the hill with the 26th Battalion in drill-field formation, providing an excellent target to the fully alerted Federal gunners and sustaining their first five casualties. Echols' Brigade pressed forward on the east, conforming to Wharton's movement.

The Federal line was set up as described earlier, except that von Kleiser's New York Battery later was to come up to a support position on the Pike a quarter-mile north of the Lutheran church. The 18th Connecticut had dashed up into the line about 1100, just as Breckinridge's skirmishers came over the hill. A drenching rain was falling, and the guns continued to duel. Hardtack was issued to the newly arrived troops, but the men could not finish it because of adjustments being made to their line. Companies A and B and, later, Company D of the 18th Connecticut were sent forward from the River Road to the southern brow of the hill to act as skirmishers. While they were doing this, about 1140 Breckinridge withdrew his guns off Shirley's Hill and sent them to a position just south of the village. The cadet gun section joined them there. Only Jackson's Battery remained on the hill to support Wharton's advance directly. While this was going on, about 1145 Sigel and Sullivan reached Rude's Hill. Sigel paused briefly to watch the battle, then galloped forward with his retinue. Sullivan remained with his brigade just south of Rude's Hill, awaiting orders.

The Confederate advance resumed about noon. Breckinridge had adjusted his line somewhat by bringing the 26th Virginia up to the west of the 51st Virginia and sending it down Indian Hollow, a small valley on the west running toward the Shenandoah. This left the VMI cadets as his only reserve. On the other flank, Imboden's cavalry probed gingerly through woods east of New Market and encountered Federal cavalry facing them. This discovery led Imboden to propose going east of Smith's Creek to attempt flanking the Federal position from that side. While he and Breckinridge were discussing the plan, Sigel finally arrived in the battle area escorted by Companies F and M of the Lincoln Cavalry. Sigel left his staff at Rice's House and rode forward to the battle line to see things for himself. He quickly decided that there was not time for all his forces in the rear to come forward to Moor's original line; consequently, he directed a withdrawal from the original line back to the high ground on Bushong's Hill. There his flanks would be protected by the Shenandoah's bluffs on the west and Smith's Creek on the east, and he stood a better chance of consolidating his force. Sigel immediately ordered Carlin's Battery to Bushong's Hill and von Kleiser's Battery up to support the withdrawing line. A few minutes later, he directed General Sullivan to bring up the rest of his infantry to the Bushong's Hill position. The literal-minded brigadier complied, leaving DuPont's Battery awaiting orders south of Rude's Hill.

Breckinridge's attack was in full force by this time. The 18th Connecticut skirmishers fell back on the rest of their regiment. The regiment soon extricated itself with some difficulty and fell back with the 123d Ohio to a line about 400 yards farther north, almost on a line with von Kleiser's position on the Pike. About 1230 Sigel ordered Snow's Battery and the 1St West Virginia to withdraw from New Market and to set up on Bushong's Hill, thus vacating the village completely. A half-hour cannonade ensued in the continuing rain. While that was going on, Imboden moved the 18th Virginia Cavalry and one section of McClanahan's artillery east of Smith's Creek. The 23d Virginia Battalion extended its line to the creek to fill in the gap his departure created. Imboden then moved north to a point where his guns could enfilade the Federal flank. This caused General Stahel to pull his cavalry slightly north, behind a ridge just to the north of the present Pennsylvania monument. Ewing's Battery, now back with the cavalry, engaged the Confederate guns to little mutual effect for the remainder of the day. Imboden then tried to carry out the second part of his task, which was to destroy the bridge over the Shenandoah at Mt. Jackson to block a Federal retreat. He found the water too high to cross to approach the bridge and rejoined Breckinridge at 1600, too late to contribute further to the battle.

The 18th Connecticut and 123d Ohio resisted briefly at their second position, allowing Sigel's final line to form. One of von Kleiser's guns was now disabled on the Pike and had to be abandoned when the battery withdrew. The two infantry regiments were fairly shattered by this time, although Company D of the 18th Connecticut attached itself to the 34th Massachusetts to continue the fight later. Breckinridge immediately pressed forward his guns massed on the east as the Federals withdrew. He used his artillery almost as an assault unit in itself, offsetting somewhat his numerical inferiority while helping to suppress some of the fire of the well-handled Federal artillery.

By about 1400, Sigel's final line was almost fully established. On the west overlooking the Shenandoah bluffs, Company C, 34th Massachusetts, provided support to part of a gun line extending along nearly half of the Federal front. Carlin's West Virginia Battery started on the bluff, and to its left was Snow's Maryland Battery, then von Kleiser's Battery of Napoleons. The 34th Massachusetts next took up the line, just about 350 yards due north of the Bushong farm; the 1st West Virginia was to its east. About 1420 the line was extended from the left flank of the 1st West Virginia to the Pike by the 54th Pennsylvania. It had jogged from Rude's Hill after marching from Woodstock with Sullivan earlier in the day. It was preceded on the field by the 12th West Virginia, which placed five companies behind the 34th Massachusetts and its remaining five about 200 yards behind Company C, 34th Massachusetts, on the Federal right flank. About 1430, Captain DuPont brought his battery up the Pike on his own initiative and held it about one quarter mile north of the line while he watched the situation develop.

About that time, the Confederate line had reached the Bushong enduring a growing hail of Federal fire. The 51st and 30th Virginia had become somewhat mixed in the advance. The eastern course of the Shenandoah River had squeezed the 26th Virginia eastward behind the 51st Virginia. At the same time, the topography on the western side of the Confederate line had protected the 26th and part of the 51st from much of the fury of the Federal fire. This was not the case for the portion of the 51st and elements of the 30th around the Bushong farm. They had reached the farm's northern fence line, but then were forced back to its southern side. The 62d Virginia on their right had advanced a hundred yards farther before being blasted back with 50 percent losses to a position on line east of the Bushong House. General Breckinridge reluctantly directed that the VMI cadets fill in the gap left by the 51st Virginia around the farmhouse. The cadets moved on both sides of the house to re-form their line in an orchard, and after climbing over a fence, they lay down and exchanged fire with the Federal line about 300 yards away.

The climax of the battle was fast approaching. General Sigel had noted the discomfiture of the Confederate line and ordered a counterattack, but unfortunately his orders were not clear and they were poorly executed piecemeal. First, about 1445, the Federal cavalry attempted to charge up the Pike. It rode virtually into the mouths of the guns Breckinridge had set up on the ridge southeast of the Federal line. The cavalry's position was worsened by the response of the Confederate infantry, which briefly faced the Pike on both sides of it, adding a wall of fire on each flank of the quickly decimated Federal horse. The troopers were repulsed with great loss in a matter of minutes. At about this time, a violent thunderstorm was adding to the confusion. Confederate fire continued to build on the Union line. Jackson's Battery was deployed southeast of the Bushong House and one company of the 26th Virginia inched close enough to focus accurate rifle fire on Snow's and Carlin's Federal artillerymen and their teams.

Meanwhile, about 1500 the second part of Sigel's charge was attempted, and each Federal regiment in fine lurched forward more or less on its own. The 34th Massachusetts advanced halfway to the Bushong House; however, the 1St West Virginia on its left moved forward barely 100 yards before it gave up. In pulling back, it exposed both the New Englanders and the 54th Pennsylvania on its left, which had gallantly pressed into the Confederates. While this was going on, the fire on the Federal guns became so galling that Sigel authorized their withdrawal. He could see the 28th and 116th Ohio, the train guards, drawing up in line of battle near the Cedar Grove Dunker church two miles north at the base of Rude's Hill, and he directed the guns there. The two Ohio regiments had run the four miles from Mt. Jackson. Snow got away with all his pieces; however, Carlin had to abandon two guns because of the loss of horses, and von Kleiser had to leave a second gun damaged by artillery fire. Carlin lost a third gun because it became irretrievably bogged down during the withdrawal.

This withdrawal of the Federal artillery was marked by a decrease in the volume of fire, and Breckinridge sensed his moment had come. A few minutes after 1500 he ordered a general advance. The 34th Massachusetts and 54th Pennsylvania continued to resist valiantly until all the guns that could be were withdrawn. These units then defended rearward until they came under the protection of Captain DuPont's Battery, which delayed skillfully by echelon of platoon back to Rude's Hill. The Confederate line swept over the Federal positions, with the cadets capturing von Kleiser's abandoned gun along with many men from the 34th Massachusetts. Breckinridge removed the cadets from the advance about 1520: "Well done Virginians, well done men." Then, impressed by DuPont's opposition and aware of the new Federal line forming at Rude's Hill, he halted his attack about 1600 to reorganize and resupply. The Confederate artillery, including the VMI section, continued to engage the Federal artillery for another hour.

The Federal main body pulled back across the Shenandoah by 1800, followed an hour later by DuPont and a cavalry escort, which burned the bridge. By the time Breckinridge had his victorious force in hand to renew the assault, his enemy had fled. Sigel was so eager to get away that he left his badly wounded in Mt. Jackson and marched the rest of his force through the night and next day until it reached Strasburg the following evening.

Aftermath

New Market unquestionably was what some historians have called the "most important secondary battle of the war." It temporarily unhinged Federal plans for the Valley, preserving its resources longer for the faltering Confederate war effort. Even more significantly, it secured the strategic flank of Robert E. Lee's forces, by then seventy-five miles to the east, locked in mortal combat with Grant's and Meade's men. It is not beyond reason to say that the battle extended the life of the Confederacy by nearly a year. This strategic success was one thing; the inspiring example of the VMI cadets was another. Theirs was one of several decisive contributions to the battle, the absence of any one of which would have been fatal to Confederate success. However, this group of young men averaging eighteen years of age were not hardened troops. They were called from their campus to fight for a cause in which they believed. They faced reality unflinchingly and gallantly carried out what was expected of them. Their performance had a lasting positive effect on Southern morale and still inspires their successors.

Breckinridge's masterful performance as both a department commander and tactical leader distinguished him as one of the best of many good Confederate generals. Success was possible at New Market because of his prompt assessment of the situation and the flexibility he had incorporated into his defense plans. His innovative tactical measures including the use of deception and the aggressive use of his artillery combined with his strong personal leadership to offset many disadvantages. His success was virtually assured by his willingness to accept the risks necessary for victory. Thus, his disregard of the odds and his gamble to hold nothing in reserve at the critical moment were proved fully justifiable.

Franz Sigel, on the other hand, was the antithesis of this great Southerner. He displayed excessive caution while failing to think through the purpose or value of many of his decisions. He burdened himself with excessively large trains requiring far too much manpower to guard. His disregard for unit integrity led him to send Colonel Moor forward with a mixed collection of units, few of which had worked together before. His lack of organization led to such things as Captain DuPont's being forgotten in the heat of battle while von Kleiser's short-range Napoleons were disadvantageously deployed. Sigel failed to use his staff, personally conducting minor-level reconnaissances and deployments. At the same time, he thought too much of strategy and not enough of tactics, completely ignoring the effect of his decisions on the physical condition of his men. His Chief of Staff, Col. David H. Strother, said of him, "There is no trace of cowardice in Gen. Sigel, as there was certainly none of generalship. Sigel has the air to me of a military pedagogue, given to technical shams and trifles of military art, but narrow minded and totally wanting in practical capacity." Most would agree with Colonel Strother's conclusion "We can afford to lose such a battle as New Market to get rid of such a mistake as Gen. Sigel."

For a moment New Market made it seem as if another Stonewall had come to the Valley. But, although further encouraging moments were experienced in the summer of 1864, the South was inevitably declining. The promise of New Market soon was buried in Federal generalship and numerical and materiel superiority. Thus, by the time of the battle's first anniversary, peace had come to the Valley on Federal terms. The examples of courage and dedication shown in the battle, however, will endure forever.