AGF Study, No. 2: A Short History of the Army Ground Forces

CHAPTER II

THE INCEPTION AND MISSION OF THE ARMY GROUND FORCES

NB: The original charts included in this study are nearly in illegible in places —

the images included in is online version, unfortunately, reflect that condition.

In the reorganization of the War Department, effective 9 March 1942,[1] top control was concentrated in the War Department General Staff, which, relieved of the administration of all Zone of Interior functions, was reduced to modest size.[2] As stated officially, the primary purpose of the reorganization was to relieve the General Staff and the Chief of Staff of administrative duties, setting them free to devote themselves to their proper functions of planning and over-all supervision.[3] In this sense, the reorganization was a new attempt to meet what Secretary of War, Elihu Root, in 1902, had referred to as "the eternal issue of planning versus administration,"[4] and draw afresh and more firmly the line between them. Planning and supervision were to be exercised by the General Staff. All "operative functions" were delegated to the three new major commands at home and to the theater commanders abroad. It was hoped that the result would be to cut red tape and expedite administrative

[24]

action, as well as produce better planning. Each of the new commands was specifically enjoined to use "judicious shortcuts" "to expedite operations."[5] When directed to inspect the three new headquarters, The Inspector General was instructed to give special consideration to the "delegation downward of all practicable responsibility and authority and to the elimination of operating within the War Department and the Air, Ground and Services of Supply General Staffs." General McNarney said on 17 March, as the new scheme went into action: "...To reiterate once more, the purpose of the reorganization is to decentralize, giving officers in charge of activities greater powers of decision and responsibility for matters under their control."[6] "The second objective of the reorganization," as stated by Secretary Stimson, "was to give the Air Corps its proper place," recognizing "that this war is largely an air war." The view of the Air Chief was adopted that "the proper organization for the air forces" was to bring them "up from their previous status to exactly the same status as the ground forces."[7] In general, the

[25]

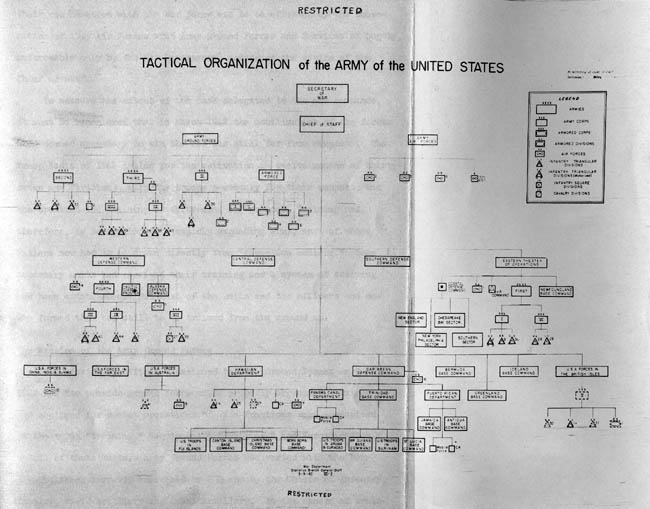

CHART 1: TACTICAL ORGANIZATION OF THE ARMY OF THE UNITED STATES, 9 MARCH 1942

problem of integrating other arms and services was to be solved by putting them under the command of Army Ground Forces and Services of Supply. Their coordination with the air force was to be effected by the cooperation of Army Air Forces with Army Ground Forces and Services of Supply, enforceable only by the War Department, acting on the advice of the Chief of Staff.[8]

To measure the extent of the task delegated to new commands, it must be remembered that in March 1942 the mobilization of the forces then deemed necessary to win the war was still far from complete. The Troop Basis of 1942 called for the activation in twelve months of thirty-seven new divisions, with the troops necessary for their support, and the creation and training of fifty-nine air groups. Training had, therefore, to be applied to a rapidly expanding army, most of whose fillers now had to be drawn directly from "reception centers." Some necessary units had received their training and a system of training had been established. But most of the units and the officers and men who formed them had still to be trained from the ground up.

The Mission of the Army Ground Forces

The mission specifically assigned to Army Ground Forces on 9 March 1942 was "to provide ground force units properly organized, trained and equipped for combat operations."[9] Its functions were summarized in the terms "training," "equipment," "doctrine," and "organization." In all of these matters Army Ground Forces was vested with the responsibilities formerly exercised by GHQ and by the Chiefs of Infantry, Cavalry, Field Artillery and Coast Artillery. In the sphere of training this meant that General McNair became responsible for the individual

[26]

training of officers and troops in those arms, in addition to the training of large tactical units which he had supervised as Chief of Staff of GHQ.

With regard to training, Army Ground Forces was to direct, supervise and recommend, on lines of policy approved by G-3 of the War Department with regard to doctrine, equipment and organization it was to "develop," "review," and "recommend." It was directed to make recommendations to the Chief of Staff regarding "tactical and training doctrine," "tables of organization and basic allowances," "the military characteristics of weapons and equipment," "operational changes needed in these," and to further "the orderly continuity and progressive development" of the arms combined in Army Ground Forces. Army Ground Forces, therefore, like the other two "major commands," had planning as well as operative or administrative responsibilities.

Such was the mission of the Army Ground Forces as stated in cold print. The interpretation which this mission would receive from its Commander, Lieutenant General Lesley J. McNair, had been foreshadowed by his administration of GHQ.

The mission of Army Ground Forces imposed responsibility for the organization and equipment, as well as the training, of the ground forces. In the period of GHQ the emphasis of General McNair had been on training. The primacy of this interest with him he had repeatedly emphasized.[10] It appeared in his personal correspondence as well as in his public acts. For example, in a letter to General Lear dated 19 January 1942 regarding his friend’s "desire for combat," he added in his own hand: "Training is

[27]

the word."[11] This stress was not relaxed.[12] Summing up the mission of Army Ground Forces at West Point on 5 May 1942, he said: "Briefly, it is to create ground force units and train them so that they are fit to fight."[13] The training of units, and their fitness to fight: this was the object on which the efforts of the Army Ground Forces were centered.

In his command of Army Ground Forces, as in his administration of GHQ, General McNair insistently manifested his sense of the need for prompt and concentrated effort. "We must hurry and keep on hurrying," he said to the Army after Pearl Harbor, rejoicing that the soldier would now know "that time is precious and the stakes are great."[14] This feeling dominated the AGF conception of priority in fundamentals. From the first and consistently it opposed projects which, however desirable, would divert time and energy from the speedy attainment of combat effectiveness. The note in General McNair’s handwriting: "What you say has merit, but it’s not our pigeon," was characteristic. He took this position even when the projects were proposed by the War Department itself, unless they came in the form of orders.[15] Like GHQ, Army Ground Forces

[28]

was characterized by a sense of the urgency of the military crisis.

General McNair pointed out that the situation, as well as the pace of events, required this economy of time and concentration of effort.[16] Since most of the training would have to be given in the United States, the forces trained by Army Ground Forces would be an untried army when committed to action.[17] The utmost in effort and also the utmost in realism was needed in training. "We want every man, in so far as it is humanly possible, to experience in training the things he will experience in battle," was his own statement of his aim in January 1943.[18] He also quickly saw that the shipping problem would reduce to a minimum the trained forces that could be delivered at the front and would make it necessary for them to travel light as well as train hard. "You must train," he charged his commanders on Armistice Day 1942, "so that our transports will carry record cargoes of fighting power."[19]

[29]

As Chief of Staff of GHQ and Commander of Amy Ground Forces, General McNair had directed a program of training framed in policies which the War Department had adopted in 1940. It had been decided that, for adequate training of the ground forces, a scheduled progression through individual, unit and combined arms training was necessary. General McNair’s conception of the fundamentals in such a program had been manifested in the record of GHQ. These included (1) combined arms training; (2) faith in the tactical unit as the best school of officers and men; (3) strong leadership; and (4) the all-round training and maximum general proficiency and soldierly fitness of the individual and the small unit.[20] His adherence to these objects as fundamental in the mission of Army Ground Forces will be abundantly illustrated in what follows:

In GHQ General McNair had acquired a unique experience in developing and conducting combined arms training, and the concept of merging four of the traditional combat arms was built into the very structure of Army Ground Forces as set up in March 1942. One of the main objects set for Army Ground Forces was to weld arms and units into fighting teams. "The complexities of modern warfare are so great," said General McNair in May 1942, "that military forces now are being organized more for the task in view than according to arms ... The picture today calls for a minimum of accent on the arms and the greatest possible attention to developing balanced fighting units."[21]

[30]

Intent on mobility and striking power, General McNair vigorously favored the exploitation of new mechanical means in warfare.[22] But he insisted with increasing emphasis on the danger to the effectiveness of the Army presented by over-specialization and reliance on machines. To meet this threat he called for closer coordination of specialized arms. "Both the Germans and the Japanese," he said in his West Point address, "have shown the way. We dare do no less, and we shall be smart to do more, in perfecting the task force idea, including not the ground forces alone, but the air forces as well."

With equal insistence he contended for the general proficiency of the soldier and the small unit as basic, and continually returned to his emphasis on training to produce the tough and versatile individual as well as tactical units welded by progressive training into fighting teams. The specialized training of individuals and the specialization of units he recognized as necessary, but he was opposed to carrying it to the point where it might endanger all-round soldierly fitness. He insisted that specialties be, to the utmost practicable degree, built into the soldier and the tactical unit, instead of being compartmentalized in experts and special types of units. To the young officers at Camp Davis who had just completed their training as antiaircraft specialists he said in October 1942: "High technique and the attendant gadgets are but means to an end—effect against the enemy. Do not allow yourself to become a technician only. Become first and last a

[31]

fighting man."[23] As for the special training of standard units he adhered to the rule he stated at Leavenworth in February 1942, that it should come after their regular training and be subordinated to it.[24] In January 1943 John T. Whitaker reported him as considering "task force maneuvers" "a glamorous phrase like the word ‘Commandos.’" "Hell, we rehearsed trench raids in the last war, only we didn’t call them ‘Commandos."’[25]

Behind such statements lay the conviction that the fundamentals of warfare are unchanged. "The principles underlying these new forms and operations are not new," he declared in November 1942. "All seek to bring superior power to bear against the enemy at the decisive time and place." This power he found still reducible to two forms: the delivery of fire and "the physical contact of men."[26] "War kills by fire as far as possible, but final victory against a determined enemy is by close combat."[27] In the search for the telling balance between men and machines in warfare as fought today General McNair’s faith was pinned on men. "Much is said these days," he remarked in November 1942, "about the technical and complicated equipment manned by a modern army ...

[32]

Nevertheless the fact remains that the most compelling need in this, as in past wars, is the front-line fighter and his leader ... Victories are won in the forward areas—by men with brains and fighting hearts, not by machines."

This conception of fundamentals and the need for giving it emphasis in the face of the spell cast by machines, and more particularly perhaps by air power, led him, although an artilleryman, to put increasing emphasis on infantry. He pointed out, in November 1943, that although "the Allies have a great and growing air superiority at every primary point of contact with the enemy, ... there has been no decision ... Defeat of the German and the Jap by sea and by air does not defeat them on land ... The decisive struggle on land is fought by the infantry and its supporting arms and services... The infantry’s position measures our progress along the road to victory."[28] A year before this he had said: "It is the Doughboy who will give the battle cry of victory."[29]

General McNair applied two keys to the problem of integrating the specialties required by modern warfare: the training of tactical units as battle teams, and the development of leadership.

The training of the tactical unit as a team of combined arms was a fundamental in the training program of the Army by which General McNair set great store. He regarded the tactical unit as the best school both of troops and their officers. He believed in having them trained, from the earliest practicable moment, as members of the big teams with which they were to go into combat. Of the Armored Command, which, as the Armored

[33]

Force, had developed a considerable independence, he said in 1944 that it "needed to join the Army," both for its own good and that of the Army’s high commanders.[30]

The second main key to integration he sought in leadership based on a broad conception of the responsibilities of command. He insisted that all the specialties of modern warfare are functions of command for which responsibility cannot be delegated. "The situation today, as I see it," he wrote to General Marshall in October 1941, "is not the same as in the World War, when divisions had merely to ‘go down the alley.’ Today the tempo of all operations is speeded tremendously, but the difficulty is that the upper story of our commanders is not speeded accordingly."[31] He therefore attached as much importance to finding and training strong and versatile leaders as to the production of tough and versatile soldiers.

"Leadership is the first essential of good training, as of battle itself," he declared.[32] He attributed the sagging of morale in 1941 and its improvement in 1942 to leadership. "Young men ought not to be discontented and when they are there is something wrong. There was something wrong. Our officers were incompetent and the men training under them knew it. I don’t believe that the change of morale came because of Pearl Harbor. It came because we trained sound, competent officers, and the men under them were the first to recognize that fact

[34]

and react."[33] In the Army Ground Forces Training Directive published 7 June 1943, in his list of the "fundamentals" confirmed as such by battle experience, the first item was "strong leadership."[34] In February 1944 he wrote: "Training helps, but the commander is still the keystone of the arch of battle effectiveness."[35]

The personal interest of General McNair in the new leaders whom the Army was developing is reflected in the warmth and directness of his addresses to graduating classes of young officers.[36] In these his conception of military leadership is set forth. One essential is knowledge. "No matter what your standards of leadership may be, you can expect no useful results unless you yourself know your job. Your knowledge and personal example must inspire as well as teach your men. I have seen too often in this emergency the two infallible signs of utter lack of leadership: reading from the book, and turning things over to the sergeant while the officer tries to look important."[37] But he put even more emphasis on inspiration, resourcefulness and drive. "A diploma,"

[35]

he said to the graduating class at Leavenworth in February 1942, "can start you, but it cannot propel you or carry you. You must be self-propelling, aided I hope by what you have learned here. If you can deliver, you need no diploma; if you cannot deliver, the diploma will not save you."[38] The essential quality of command, he told the graduating class at Belvoir in September 1942, is "the vital spark of leadership ... the intangible something that makes a unit bud and blossom into full effectiveness ... A military unit is a team, and its spark-plug must be its commander." "Your leadership, of course," he continued, "must be decisive and forceful. You yourself must know where you are going and how to get there. Then all must conform to your decision. Thunderous forms of handling men are obsolete. When one hears bellowing in the field, it probably marks, not a real leader, but one who has lost his temper when things go not too well. The art is in leading men, not driving them. Free men respond to leading but resent driving."[39] His views on leadership are summed up in his Armistice Day Address in 1942: "The leader must teach his troops thoroughly, correctly and interestingly ... He must do more—a vital something more. By his personality, enthusiasm and solid knowledge he must supply the spark which infuses his men with his spirit and carries them individually and collectively along with him."

[36]

General McNair sought leaders who were not only expert in command but not afraid to exercise it. This was for him one of the meanings of fearless leadership. The complementary quality was loyal compliance with orders. He himself embodied his conception of command in both aspects. As commander of the Army Ground Forces he expected and exercised positive leadership, but regarded it as his duty, once he had presented his views to higher authority, not to argue but to obey. The Army Ground Forces was operated by General McNair as a strictly military command.

Strength and Initial Organization

In numerical strength the Army Ground Forces was a large command. From 9 March 1942 until ______ it was the largest single command in the Army of the United States. Its total strength on 1 May 1942 was approximately 780,000. This figure more than doubled during 1942 and reached a peak of 2,200,000 on 1 July 1943. In addition to the 1,750,000 individuals under command of the Army Ground Forces on 1 January 1944, units with an enlisted strength of over 900,000 and many thousands of replacements, trained by Army Ground Forces, had by that date arrived in Ports of Embarkation for shipment overseas. All but the last two aggregates include the officers and enlisted men employed in conducting the training program of the Army Ground Forces but inasmuch as the trainers were, for the most part, themselves being prepared for combat, the figures given provide a fair, if approximate, measure of the numbers for whose organization, equipment and training for combat Army Ground Forces was responsible.[40] It was the biggest single training organization the United States had ever set up.

[37]

The means with which Army Ground Forces was provided for the discharge of its mission in March 1942 were as follows: a headquarters, with a supporting headquarters company, located in Washington; a Replacement and School Command; the Armored Force; a Tank Destroyer Command; an Antiaircraft Command; and, distributed, under these special commands, eight unit training centers; fourteen replacement training centers, and seven service schools and boards of the various arms of the ground forces. The tactical units initially placed under the command of General McNair consisted of two armies, the Second and Third, with headquarters at Memphis, Tennessee and Fort Sam Houston, Texas, and two separate corps, the II and VI, with headquarters at Jacksonville, Florida and Providence, Rhode Island. Service units supporting ground combat troops were assigned to the tactical commands of the Army Ground Forces, as required, by their tables of organization. Such assignment for training was essential to the development of larger tactical units as teams, and they received training in their service specialties as well as in tactical cooperation under the direction of Army Ground Forces.[41]

Organization of Developmental Functions

The organization of the Army Ground Forces reflected the two sides of its mission. One was the training of tactical units, from the platoon, battery, troop, and company up to the army, together with their supporting units, as fighting teams. This was consistently regarded by Army Ground Forces as its primary mission. The other comprised the developmental functions of the arms combined in Army Ground Forces.

[38]

Army Ground Forces was directed to develop the equipment, doctrine, organization and personnel of ground forces to the point of readiness for tactical employment in training and combat. The functions of the Chiefs of the four older branches now combined in Army Ground Forces—Infantry, Cavalry, Field Artillery and Coast Artillery—were assumed by General McNair. Their boards, schools, and replacement centers, together with those of the Armored Force and the budding Tank Destroyer Center, became a part of the organizational apparatus of his command.

The developmental activities of the Army Ground Forces, less those relating to personnel, were centered in the Requirements "Division" of the headquarters staff, a large and important section created for this purpose. Its functions embraced equipment, organization, and training literature (including visual aids to training). It was to develop equipment, provide tables of organization and tables of equipment (then called "tables of basic allowances"), and supervise the preparation of technical literature and visual aids for the arms and "special combat units" combined in the ground forces. More generally, Requirements was charged with "the promotion of the orderly continuity and progressive development of the several arms and for their coordination in the interest of Army Ground Forces as a whole."[42] It was thus the most conspicuous organizational expression of the combination of arms and services effected by the creation of a single command over the ground forces.

into the make-up of the Requirements Division as set up on 9 March went the materiel sections of the offices of the chiefs of arms absorbed

[39]

into Army Ground Forces, and the Developments Branch of G-3 of the War Department General Staff, to carry on the development of equipment; also the Publications Branch of G-3, to assist in preparing technical and training literature and visual aids. The Requirements Section was expected to work in close coordination with the Services of Supply. If a theater commander recommended modifications of a weapon, "these people get it right away," Colonel Harrison, of the Reorganization Committee, explained, in an exposition of the new staff organization, "they analyze it; they take it over personally to the Services of Supply man that works on that, and between the two of them they see what they can do about it, and they try to get that change made as rapidly as possible."[43] Close relations were maintained with the Development Branch of the Requirements Division, Services of Supply, which was charged with direction and supervision of engineering research and development;[44] in addition, officers of the Requirements Section, Army Ground Forces, were stationed at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, and Aberdeen, Maryland, for direct liaison with Signal and Ordnance, and with the National Inventors Council and the National Inventors Research Council; also, originally, at Camp Holabird, Maryland, with the Quartermaster Corps, later at Detroit, when the Automotive Center was separated from that Corps.[45]

[40]

The developmental activities of the Army Ground Forces "in the field" were carried on by boards, schools, and training camps located at the installations in which the interests of the various ground arms were concentrated. Some of these already had a past—the Infantry center at Fort Benning, Georgia, Cavalry at Fort Riley, Kansas, Field Artillery at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, Coast Artillery at Fort Monroe, Virginia, the Armored Force at Fort Knox, Kentucky. Two others, just taking shape, now received an ampler establishment: Antiaircraft, of which the board and service school were placed at Camp Davis, North Carolina, and the headquarters at Richmond, Virginia; Tank Destroyers, whose center was moved in February of 1942 from Fort George G. Meade, Maryland to Camp Hood, Texas, where a headquarters, board and service schools were subsequently established. Presently other special training agencies were set up as subordinate commands: the Amphibious Training Center, activated at Camp Edwards, Massachusetts, in May 1942, and moved in October to Carrabelle, Florida, the Airborne Command, the Desert Training Center at Camp Young, California, and the Mountain Training Center at Camp Hale, Colorado. [46]

The boards in the old and new installations of the ground arms became, in effect, field agencies and working parts of the Requirements Section of Headquarters, Army Ground Forces, for the service testing of weapons, ammunition and equipment. In the original organization of that section the boards of the four older arms, though not in Washington, were

[41]

CHART 2: CHAIN OF COMMAND, AGF, 9 MARCH 1942

CHART 3: CHAIN OF COMMAND, AGF, 1 SEPTEMBER 1942

integrated with that "Division" as a Service Boards Branch.[47] The boards of the newer centers and commands at the beginning operated through the headquarters of these commands. But the relationship with Headquarters, Army Ground Farces, with all the boards was close and became closer and more direct as time went by. Coordination of the boards with the agencies of the Services of Supply, particularly with Ordnance, Engineers and Signal Corps, was effected through the Requirements Section of Headquarters, Army Ground Forces, and also, after the staff reorganization on 12 July 1942, through the appropriate special sections of that staff.

The service schools of the older arms and of the newer combat specialties united in the Army Ground Forces served as field agencies of Army Ground Forces in the two other developmental functions which now became AGF responsibilities, namely, the development of doctrine and training literature, and the special training of personnel.

Acting in the first of these two capacities the schools formulated data for the revision of doctrine, and of technical and tactical literature and training aids. The special development of personnel was carried on at each of the centers by the service schools, including schools for officer candidates, and also by the replacement training centers of each arm or specialty.

These were widely scattered. In March 1942 there were replacement training centers for Infantry at Camp Croft, South Carolina, Camp Wheeler Georgia, Camp Wolters, Texas, and Camp Roberts, California; for Cavalry

[42]

at Fort Riley, Kansas; for Field Artillery at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, Fort Bragg, North Carolina, and Camp Roberts, California; for Coast Artillery at Fort Monroe, Virginia; for Antiaircraft Artillery at Fort Eustis, Virginia, Camp Wallace, Texas, and Camp Callam, California; and for Branch Immaterial training at Camp Robinson, Arkansas and Fort McClellan, Alabama.[48] Under the Army Ground Forces the immediate control of the schools and replacement training centers of the four older branches was given to a Replacement and School Command, located in Birmingham, Alabama. Those of the newer arms or specialties were made the responsibility of the command concerned. The Replacement Training Center of the Tank Destroyer Center was an exception. It was put under the control of the Replacement and School Command.[49]

The degree of activity and influence exercised in the formulation of doctrine and training aids by the intermediate commands and centers varied. In general, it may be said that the intermediate headquarters other than the Replacement and School Command, in other words, those of the new specialties, exerted at first a more positive influence, while the Replacement and School Command acted in such matters largely as a forwarding agency. As time went by, Headquarters, Army Ground Forces, came to exercise more and more initiative and influence over the whole of the field of development. After October 1942, that headquarters was authorized to determine the tactical doctrine and tables of organization and equipment even for service units assigned to the ground forces.[50]

[43]

CHART 4: RTC's, TC's and OCS's, 9 March 1942

The final distribution, under Headquarters, Army Ground Forces, of the developmental functions formerly exercised by the Chiefs of Branches will be fully apparent only when the headquarters organization of the Army Ground Forces and its evolution have been described.[51] Development of organization and equipment was coordinated in the Requirements Section of the headquarters staff. The development of tactical doctrine was primarily a function of G-3. The development of personnel headed up in G-1 and G-3: procurement and assignment in G-1; individual and special training in G-3—in appropriate divisions of those sections: Infantry, Cavalry, Armored, Amphibious, etc.

Organization for Tactical Training

The training of tactical units, and the basic training of inductees not assigned to replacement training centers, was conducted by the Army Ground Forces through the medium of armies and corps "as assigned," and in the divisions and non-divisional units of various types assigned these corps and armies. AGF directives went only to its training commands and to armies and separate corps. The further interposition of Headquarters, Army Ground Forces, took the form of inspections. GHQ troops and units had been assigned to GHQ for control and training; no such units or troops, except a headquarters company, were assigned to Army Ground Forces. GHQ had supervised the training of all of the four armies then in existence. To the Army Ground Forces were assigned only two of these: the Second, commanded by Lt. General Ben Lear, and the Third, commanded by Lt. General Walter Krueger. On 9 March the First and Fourth Armies were placed directly under the orders of the War

[44]

Department to garrison, respectively, the Eastern and Western Defense Commands.

After Pearl Harbor these two commands had been reinforced with units drawn from the Second and Third Armies, and placed under the orders of General DeWitt on the Pacific and General Drum on the Atlantic to counter potential invasions. Consequently, in March, there were no corps and only four divisions in the Second Army. In the Third Army were two corps and six divisions.[52] In the defense commands troops and units received only such training as was incidental to the alerted status of these commands, and as the emergency became less acute, units were shifted back to the Second and Third Armies and the separate corps to resume intensive training under the Army Ground Forces. The actual strength of the Second and Third Armies on 30 June 1942 was, respectively, 160,295 and 204,283, and of the separate corps 233,838. Expanded by the creation of new units and the transfer of units from the defense commands, the totals on 31 December 1942 were: Second Army, 401,239; Third Army, 330,785; Separate Corps, 223,209.[53] The Second and Third Armies were used by the Army Ground Forces to train the ground units stationed in the great interior area of the United States, particularly in the South.[54] For training those stationed in the coastal zones, Headquarters, Army Ground Forces used as its agents the separate corps, which were virtually small armies.

[45]

CHART 5: TACTICAL ORGANIZATION, AGF, 9 MARCH 1942

CHART 6: ORGANIZATION, HEADQUARTERS, AGF, 9 MARCH 1942

Organization of Headquarters, Army Ground Forces

The Committee on Reorganization gave the Army Ground Forces a headquarters staff of novel design.[55] It contained divisions echeloned at two levels—a policy level and an "operating" level. On the first were the familiar G-1, G-2, G-3, and G-4. To these four was annexed a Plans Division, whose duties mere to study and prepare "long-range plans and policies for the Ground Forces," and to coordinate "general plans prepared by the other staff divisions." At the "operating" level, instead of the customary special staff sections, were divisions designed to represent the operating or administrative functions of the Army Ground Forces, namely, Personnel, Operations, Training, Requirements, Transportation, Construction, Hospitalization and Evacuation, and Supply. Auxiliary to the general staff divisions were a Public Relations Division and a Statistics Division. The Special Staff was limited to the Adjutant General and a Budget and Fiscal Division.[56]

This organization did not work efficiently and was abandoned after three months of trial.[57] The staff organization adopted on 12 July 1942 was shaped on the familiar lines of general and special staff sections set forth in FM 101-5 for the guidance of staff officers with troops.[58]

[46]

The general sections were now specifically directed to supervise the execution of directives, in short, to "operate" as well as plan.[59] The remaining functions of detailed administration formerly entrusted to "operating divisions" were henceforth divided among the sections of the Special Staff.[60] Over-all planning for, and coordination of, the special staff was vested in G-4.[61]

Two features of the March organization were retained—the Plans Section and Requirements. In July, Requirements was raised to the level of a general staff section.

The G-3 Section, absorbing the Operations and the Training Divisions, emerged from the reorganization of the staff on 12 July 1942, as the central and largest section of the staff, as was appropriate in a command which regarded training as the core of its mission. Second in strength was Requirements whose functions were closely interwoven with those of G-3. These two sections comprised 50 per cent of the officer strength of the AGF headquarters staff.[62] Reading the directive regarding the July reorganization of the staff, one might suppose that, although Requirements

[47]

CHART 7: FUNCTIONAL CHART, HEADQUARTERS, AGF, 11 AUGUST 1942

was raised to the general staff level, it was subordinated to G-3, as far as primary responsibility for many matters of common interest was concerned.[63] Actually, in such matters, which included development of tactical doctrine and the preparation of training publications, visual training aids, and tables of organization for the ground arms, G-3 and Requirements acted as a single staff group. In the review, and after October 1942, in the determination of tactical doctrine and tables of organization and equipment for service units assigned to the Amy Ground Forces, G-4 and the special staff section concerned came into the same working unity. A proposal to change organization or modify doctrine might start in G-3, Requirements, G-4, or in one of the Special Staff Sections. One officer would then be given the ball and run it through for coordination, with a minimum of paperwork and time-consuming general "conferences"—an expeditious procedure feasible only in a small and closely-knit staff organization.

The functions of the other sections, general and special, were those fixed by custom and stated in FM 101-5, with such adaptations as were necessary to the mission of the Army Ground Forces as a command. They are defined in detail on chart on page opposite.

Headquarters, Army Ground Forces as a Working Organization

Such was the staff of the Army Ground Forces headquarters as charted. What Headquarters, Army Ground Forces was will appear more clearly in the history of what it did. But certain facts about it as a going concern may be mentioned at once.

[48]

It was a lean headquarters. Although General McNair was given the largest of the three new commands, his staff, as compared with those of the Army Air Forces and the Services of Supply, was conspicuously small. The strength of the three headquarters in commissioned officers on successive dates was as follows:

AGF |

AAF |

SOS (ASF) |

|

30 April 1942[64] |

212 |

885 |

4,177 |

31 December 1942[65] |

240 |

2,210 |

5,360 |

31 December 1943[66] |

270 |

2,595 |

7,227 |

30 April 1942

Officers |

Enlisted Men and Civilians |

Total |

|

AGF |

212 |

512 |

724 |

AAF |

885 |

3,309 |

4194 |

SOS (ASF) |

4,177 |

33,067 |

37,244 |

31 December 1943

Officers |

WO |

Enlisted Men and Civilians |

Total |

|

AGF |

270 |

53 |

911 |

1,234 |

AAF |

2,595 |

60 |

9,920 |

12,591 |

SOS (ASF) |

7,227 |

32 |

38,952 |

46,474 |

In December 1942 the authorized enlisted strength of Hq AGF was 763, the actual strength 665. Comparable figures for AAF and ASF are as follows:

Authorized |

Actual |

|

AAF |

4,041 |

4,454 |

ASF |

5,637 |

6,263 |

Minutes GS (S), 28 December 1942.

[49]

The compactness of his staff was a fact to which General McNair was accustomed to refer with satisfaction when welcoming newly assigned officers. The number of officers initially assigned was 161.[67] The headquarters was placed on an allotment basis. The first allotment provided for 239 officers, 657 enlisted men (402 for duty with the staff) and 188 civilians.[68] On 14 April the allotment of enlisted men was increased to 763 (410 for duty with the staff). At the end of 1942, although the strength of Army Ground Forces as a command had risen from 750,000 in June to an authorized 1,125,000 in December and many unforeseen responsibilities had developed, the commissioned strength of the headquarters staff had been increased only to 246. Thirty-two warrant officers had been assigned. The number of enlisted men on staff duty remained 410; the number of civilians was 203. A year later the corresponding numbers were 256 officers (plus 6 general officers) 50 warrant officers, 470 enlisted men, and 199 civilians. With one exception the civilians at Headquarters, Amy Ground Forces, were employed for administrative or clerical duties, and not in a consultative capacity.[69] The maximum strength of the headquarters, reached in _____19__, was _____________.[70] Overhead was kept to a minimum.

[50]

Headquarters, Army Ground Forces was not heavily loaded with rank. When the staff had shaken down into running order, it contained only seven general officers: a lieutenant general, a major general and five brigadier generals.[71] In January 1943, when an increase of strength in the grade of colonel was sought and the number of colonels raised from 51 to 65, it was pointed out that to bring the proportion into line with "the field," the number would have to be 100.[72] In November 1943 by order of the War Department another brigadier general was added to serve as Antiaircraft Artillery Liaison Officer,[73] bringing the total of general officers to eight.

The headquarters was located apart from the War Department and the headquarters of the other major commands in Washington. It had its offices on the Army War College post, on the point of land between the Potomac and Anacostia Rivers, where GHQ had been located. Minor alterations were made in the War College building and a temporary annex, "T-5," which had been planned to accommodate the anticipated expansion of GHQ, provided necessary additional space. Into this G-3, Requirements and the Special Staff Sections moved with the reorganization on 12 July 1942. Space

[51]

was allotted to the Army Ground Farces in the Pentagon, the vast office building of the War Department across the Potomac, which was being rushed to completion in the summer and fall of 1942. Into the Pentagon most of the staff of the Army Air Forces and the Services of Supply sooner or later moved. General McNair chose to keep his headquarters at the War College, retaining in the Pentagon only a suite of offices, occupied by a liaison officer.

By this decision the Army Ground Forces forwent advantages which the staffs of the other commands may have gained from such daily personal associations and immediate conferences with the War Department staff as were practicable in the intricate, highly organized mazes of the Pentagon, whose office population rose, by the end of 1943, to 27,874. But hurried decisions were not often required by the mission of the AGF staff, and for immediate communication telephones were on every desk. Against the disadvantages of a location apart from the War Department were to be weighed conditions favorable to more deliberation, and also a greater cohesiveness and mobility resulting from the daily associations of a small separate group.

Furthermore, location at the War College permitted an accentuation of the military character of the headquarters of Army Ground Forces. It is true that within the walls of the old Army War College Post, the colonnades of the houses in officers’ row, the golf course and tennis courts, and the elm arcades along the river carried over from War College days some of the atmosphere of a university campus. Nevertheless, Headquarters, Army Ground Forces, had external military features which the Munitions Building and the Pentagon lacked. The quarters of the commanding general and of ranking staff officers and the barracks

[52]

of the headquarters company were on the post. In the mornings the troops marched to the headquarters buildings, and on Saturday mornings the colors mere carried and passed in review. After the U.S. Military Band left the post 15 December 1942 and went overseas, the headquarters company improvised a band to provide the music for its marches. Although Headquarters, Army Ground Forces was located in Washington, its resemblance to an army headquarters was strong. Its relation with the field forces under its supervision was emphasized. It faced toward "the field."

The headquarters staff was homogeneous as well as small. The original staff was drawn from three sources: GHQ, the War Department General Staff, and the offices of the chiefs of the combat arms. Ninety-seven (60 percent) of the officers originally assigned had been working together under General McNair on the staff of GHQ; 40 were transferred to Headquarters, Army Ground Forces from G-3, War Department General Staff; 34 had been in the offices of the chiefs of arms.[74] 65 per cent of the original staff were Regular Army officers. The percentage on 31 December 1942 was 54,

[53]

on 31 December 1943, 48.[75] All of the colonels or, the staff were Regulars until January 1944, when four in the Officers Reserve Corps were included, one being assigned as a replacement, and three promoted to that grade from lieutenant colonels on duty with the staff.[76]

"Cohesion" was one of the objects sought in the July reorganization.[77] As the staff was small, it was unnecessary to multiply offices for the supervision of routine and General McNair opposed the establishment of what he called "a mass of paperwork and ritual."[78] The Secretariat, which performed the duty of processing headquarters memorandums, orders and directives for signature, was a little group administered by the Deputy Chief of Staff. Excessive specialization of staff functions was discouraged. General McNair, reviewing the work

[54]

of his staff two years later, emphasized the fact that the general staff sections were "charged with both policy and operations."[79] Staff officers were expected to coordinate their decisions by informal contact and hold administration by paperwork to a minimum. General McNair’s dictum on staff procedure was: "Papers are no good. You must translate papers into action."[80] It was reported that he would remove an officer for having a cluttered desk.[81] Whether he ever took such action or not, the custom of the headquarters exerted a pressure in favor of dispatch and economy in the transaction of business, and thrift and clearness of language in wording papers. The keynote was given by General McNair’s rapid "What does this mean?", "O.K. by me!" or "Not our pigeon," scribbled in pencil on papers crossing his desk, and by the terse, clear prose he himself wrote. His mordant letter of 1 January 1943 attacking excessive paperwork, itself a classic example of his style, applied to the field a headquarters rule.[82] One of General McNair’s fundamental principles was that "Training depends on sound directives followed by personal supervision."[83] In pursuance of his ideas the papers to which his own staff gave particular care were the headquarters directives.

[55]

Much importance was attached to having these sound and clear. Written reports were kept to a minimum. "Reports of training," wrote General McNair to his commanding generals, "are of doubtful value. Higher commanders should know the state of training sufficiently by inspections on the ground."[84] He himself and the members of his staff spent much of their time on inspections.

The spirit of the staff was one of solidarity and mutual helpfulness. General McNair was seldom seen in the headquarters out of his Office,[85] but his purposes were well known, and anyone who served on his staff will recognize the force continually exerted by its unwritten rule that whatever the General regarded as his business became everyone’s business, and, as such, was taken in hand with alacrity.

[56]

[1] Circular No. 59, WD, 2 March 1942. For the place of AGF in the tactical organization of the Army, see Chart opposite p. 25.

[2] The officer personnel of the War Department General Staff was reduced from 647 on 31 December 1941 to 204 on 31 March 1942. Table, 12 April 1943, prepared by Statistics Branch, General Staff.

[3] Statement of Secretary of War Stimson to the press, as reported by the New York Times, 5 March 1941. Also statement of General McNarney before the Senate Committee on Military Affairs, 6 March 1942, Hearing on S. 2092, 77th Congress, Second Session.

[4] Hearing before Senate Committee on Military Affairs, 17 December 1902. Discussions of the question will be found in the following: Historical Documents Relating to the Reorganization Plans of the War Department and to the Present National Defense Act, Hearings before the House Committee on Military Affairs, 69th Congress, 1927, Part I; Report of Committee No. l, 28 September 1934, Army War College Course, Terry Memo, Ibid, 1935-36; Report of Committee No. 3, Ibid., in AWC Records.

[5] Pars 5 c (15), 6 c (20), 7 e (17), WD Circular 59, 9 March 1942.

[6] (1) Memo for TIG, WDCSA 020(10 Mar 42), 10 March 1942, Subject: "Inspection of the War Department Organization"; (2) Minutes, General Council (S), 17 March 1942.

[7] Statement of Gen. McNarney before Senate Committee on Military Affairs, 6 March 1942. The result was to be accomplished by (1) making the Air Forces a separate command, and (2) giving the Air Corps a representation of 39 officers out of the 98 on the General Staff, distributed as follows: 20 of the 60 officers in the War Plans Division; half of the 38 officers in G-1, G-2, G-3, and G-4. Secretary Stimson’s statement, cites in note 3, p. 24 above. Gen. McNair summarized the effect of the reorganization as follows: "It may be stated generally that the reorganization accomplished two important ends: first, it relieved the War Department of a large part of its former burden; second, it enabled the War Department to direct the war effectively. Incidentally, the change placed the air forces in "the big picture more appropriately than had been the case previously." Address to the graduating class, West Point, 5 May 1942. Historical File, AGF.

[8] Pars 5 c (13) and 6 c (13), Circular 59, WD, 2 March 1942.

[9] Par 5 b, ibid.

[10] See History of GHQ, USA (S), especially Chap IV.

[11] Gen Lear’s personal correspondence with Gen McNair (C), Historical File, AGF.

[12] For example, in November 1943 he wrote: "In general I am not inclined to go into overseas theaters, but I am interested only in doctrine and all aspects of training in the United States." Memo Slip, CG to G-3, AGF, 3 November 1943. In 321/410 CAC (S).

[13] Address to the Graduating Class at West Point, 5 May 1942. Historical File, AGF.

[14] Christmas Broadcast to the Armed Forces, Blue Network, NBC, 24 December 1942. Historical File, AGF.

[15] (Blank)

[16] Interview with Virginia Pasley, Washington Times-Herald, 25 January 1943.

[17] General McNair did not wish the word "green" applied to the Army as trained for this war. He declared in May 1943 that the soldiers could well be indignant to be called "green troops" after such training as the 1st Division, for example, had received before it went into action in Africa. "On the other hand, of course, they hadn’t had battle experience ... and battle experience is something, as far as I can make out, which can’t be reproduced completely, in all its angles, in the training ground." Press Conference, 15 May 1943.

[18] Interview with James Cullinane, NEA Service Staff Correspondent; as published in the Lynn Telegram News, 10 January 1943.

[19] Armistice Day Address, broadcast over the Blue Network, NBC, 11 November 1942.

[20] History of GHQ, USA, (S), Chap IV.

[21] Address to the graduating class, West Point, 5 May 1942. Historical File, AGF.

[22] See Chaps V and VI, GHQ, USA, 1940-42 (S). See also, for a later statement of his outlook on this question, an interview with James Cullinane, as reported in the Lynn Telegram-News, 10 January 1943. Historical File, AGF.

[23] Address to the Antiaircraft Officer Candidate School, Camp Davis, N.C., 29 October 1942. Historical File, AGF.

[24] Address to the graduating class, Command and General Staff School, Ft. Leavenworth, Kansas, 14 February 1942. Historical File, AGF.

[25] John. T. Whitaker, "Lt. Gen. Lesley James McNair, in These Are the Generals (New York: Knopf, 1943), p. 134.

[26] Remarks on the Army Hour Program, NBC Network, 1 November 1942. Historical File.

[27] Broadcast over the NBC Network, 28 November 1943. Historical File.

[28] Ibid.

[29] See n. 26.

[30] Par 9 d, Memo for the ASW, 330.14/100 (S), 8 February 1944.

[31] Memo for Gen Marshall, 24 October 1941. In 322.98(S).

[32] Armistice Day Address to troops of AGF, broadcast over Blue Network, NBC, 11 November 1942.

[33] John T. Whitaker, "McNair," in These Are the Generals, pp. 133-4

[34] Par 2 (1), ltr Hq AGF 353.01/52(Tng Dir)GNGCT(6-7-43), 7 June 1943, Subject: "Supplement to Training Directive effective 1 November 1942."

[35] Memo for the ASW, 330.14/100 (S), 8 February 1944.

[36] Examples, in addition to those cited in the notes that follow are: Address at Graduation Ceremony, OCS, Tank Destroyer Center, Cp Hood, Tex, 21 January 1943; Address at Graduation Ceremony, OCS, Armored Force, Ft Knox, Ky, 21 November 1942. Historical File, AGF.

[37] "The Army Ground Forces," Address before the graduating class of the United States Military Academy, West Point, N.Y., 5 May 1942.

[38] Speech before the graduating class, C&GSS, Ft Leavenworth, Kan, 14 February 1942.

[39] Address before the graduating class, Engineer OCS, Ft Belvoir, Va, 30 September 1942.

[40] See Charts in "Army Ground Forces: Statistical Data," prepared by the Ground Statistics Section.

[41] The schools and other installations for the training of officers and enlisted men of the services were under the Services of Supply.

[42] Par 5 k (1), ltr Hq AGF 320.2/8(AGF)(6-24-42) 8 July 1942, Subject; "Organization of Army Ground Forces."

[43] Hearing of the Senate Committee on Military Affairs, 6 March 1942, p. 15.

[44] Par 3, memo for the ACofS, G-3, WDGS, 15 April 1942, Subject: "Creation of Additional Research and Development Agencies." In 334/5 AGF.

[45] The liaison officers with the Chemical Warfare Service, Army Air Forces, Navy and Marine Corps, provided for in the original plans of organization, were not appointed.

[46] Dates of activation were as follows: Airborne Command, 21 March 1942; Desert Training Center, l April 1942, Mountain Training Center, 27 August 1942. To compare the organization on 9 March and 1 September 1942, see first and second charts opposite.

[47] Ground Statistics Division, Blue Book, "Organization and Duties of Staff Divisions," 1 June 1942.

[48] See chart opposite.

[49] Tank Destroyer History (C), prepared under the direction of Hq AGF, Chap X, p. 2.

[50] This responsibility was finally assumed in January 1943, when the officers were provided. Interview with Col. L. H. Frasier, Chief of Organization Division, Rqts Section, 10 June 1944.

[51] See below, pp. 46 ff.

[52] See chart opposite p. 25.

[53] "Monthly Strength of the Army." Part I, AGO-MRB AG 320.2 QM-R, for dates indicated.

[54] See chart opposite.

[55] See chart opposite. The initial assignments of Chiefs of Divisions will be found in G.O. No. 2, Hq AGF, 9 March 1942. In 300.4 AGF(G.O.).

[56] Inspector General and Judge Advocate General Divisions were not activated by AGF.

[57] The reorganization was announced as "effective at 12:01 AM, 12 July 1942." Memo to all Staff Sections, 7 July 1942. In 020/73, B2. After a three months’ trial, the reorganization was approved by the War Department as final on 24 October 1942. Same file. The assignments of chiefs of the general and special staff sections will be found in G.O. No. 22, Hq AGF, 12 July 1942. In 300.4, AGF, G.O. A study of this reorganization will be found in Appendix I.

[58] (1) Staff Officers Field Manual, 1940 (with Change No. 1) 24 March 1942; (2) See Chart opposite p. 48.

[59] Par 4, ltr Hq AGF 320.2/8(AGF)(6-24-42)8 July 1942, Subject: "Organization of the Army Ground Forces."

[60] In other words, each special staff section was to deal with all functions pertaining to the service which the Section represented, as follows: "Supply, training, requirements, planning, personnel (for service units), construction (applies to Engineer Section only)." Par 2 e, Memo for the CofS, AGF from Col Winn, Chairman of Committee for Preparation of Plans for Reorganization, etc. 27 June 1942, Subject: "Personnel for Reorganization of Headquarters, Army Ground Forces." In 020/73 B2.

[61] Par 2 d, Memo for the CofS, AGF, signed Winn (Plans), 27 June 1942, Subject: "Personnel for Reorganization of Hq AGF." In 020/73 B2.

[62] Combined strength in July 1942. 121 out of 244. In February 1944: 134 out of 261. (1) Memo to Staff Sections, Hq AGF, 14 July 1942, Subject: "Tentative Allotment of Officers." In 320.2/146 AGF. (2) Staff Memo No. 4, Hq AGF, 23 February 1944. In 320.2/303 AGF.

[63] Par 5 i (8), (10), (11); k (2),(3),(4),(5),(7),(8), ltr HQ AGF 320.2/8(AGF)(6-24-42), 8 July 1942, Subject: "Organization of the Army Ground Forces."

[64] Comparison of Personnel Strengths before and after Reorganization, 9 March 1942. Inclosure (not classified) with Minutes General Council, WD (S), 19 May 1942.

[65] Table prepared by Statistics Branch, GS, 17 January 1944 (C), with Minutes General Council (S), 1 February 1943.

[66] Table prepared by Statistics Branch, GS, 17 January 1944 (C), with Minutes GC(S), 17 January 1944. The total strength of the three headquarters on 30 April 1942 and 31 December 1943 was as follows:

[67] This figure does not include the three general officers at Hq AGF, the CG, Maj Gen R. C. Moore; Chief of Rqt Div. and Brig Gen Mark W. Clark, CofS. Memo for the ACofS G-1, AGF from the Personnel Div, 11 March 1942, Subject: "Adjustment in the General Staff List." In 210.31/17 AGF.

[68] The number of civilians actually employed on 8 April 1942 was only 146. Ltr Hq AGF 320.2/31(AGF)GNPER, 9 April 1942, Subject: "Estimated Number of Employees in Headquarters, Army Ground Forces."

[69] The exception was Dr. Robert R. Palmer, brought from the History Department of Princeton University to be a member of the Historical Section.

[70] The sources for the figures in the foregoing paragraph maybe found in Appendix II.

[71] The reference date is December 1942, when the general officers were: Lt Gen McNair, Maj Gen R. C. Moore; Brig Gen Floyd L. Parks, who had succeeded Brig Gen Mark W. Clark as Chief of Staff on 29 June 1942; Brig Gen Alexander R. Bolling, ACofS G-1; Brig Gen John M. Lentz, ACofS, G-3; Brig Gen Willard S. Paul, ACofS, G-4; and Brig Gen William F. Dean, Ex of the Reqmts Sec.

[72] In making this remark G-1 pointed out that the current distribution of officers on Tables of Allotment was as follows:

Army (less AAF) |

AGF |

3.3% |

2.7% |

In 320.2/165 AGF |

[73] Roster of officers, by rank, Hq AGF, 31 December 1943. The appointment was directed by Memo 660.2(10 Nov 43)WDGCT for CG’s, AGF and ASF, 10 November 1943. In 210.31/17 (R).

[74] Figures compiled from (1) Special Order No. 59, WD, 7 March 1942; (2) Ltr GHQ 210.31/79(GHQ)-A (2-27-42) to TAG, 4 March 1942, Subject: "Reassignment of Officers," (Copy in 210.31/2 AGF); (3) Memo for the ACofS G-1, AGF from the Personnel Div, 11 March 1942, Subject: "Adjustment in the General Staff List," (in 320.2/17 AGF); (4) Files of G-3 and Reqmts Secs, Hq AGF.

The numbers drawn from the offices of the former Chiefs of Arms were as follows: Infantry 12, Field Artillery 10, Coast Artillery 7, Cavalry 5. During 1942 an effort was made to maintain the following proportions between the arms in staff assignments: Infantry 50%, Field Artillery 25%, Coast Artillery 15%, Cavalry 4%, others 6%. See Staff Memos, Subject: "Allotment of Officers." In 320.2 AGF. In November 1942, G-1 suggested that all officers except in AG, and the Special Staff Sections, plus the liaison officers in Requirements, be designated as Branch Immaterial (ibid., 23 November 1942), and thereafter Chiefs of Sections were informed that they would "be responsible that their respective allotments by grade and arm or service are not exceeded."

[75] The first figure is taken from the Personnel Roster, Hq AGF, 31 March 1942, 330.3 AGF; the others from Strength Returns for the dates named. The distribution by components was as follows:

31 March 1942 |

31 December 1942 |

31 December 1943 |

|

RA |

125 |

128 |

126 |

ORC |

59 |

75 |

80 |

NGUS |

9 |

15 |

17 |

AUS |

0 |

17 |

39 |

Total |

193 |

235 |

262 |

[76] Col C. C. Gregg, who joined 34 January, and Cots V.A. St. Onge, J. H. Banville, and A. L. Harding, promoted 22 January 1944. Roster, by rank, of officers, Hq AGF, 31 January 1944. Only two officers were commissioned from civilian life.

[77] "Increase in the size of this headquarters should be avoided in the interests of cohesion..." Par 1 e, Memo for the CofS, AGF from Col Winn., Chairman, Committee for Preparation of Plans for Reorganization of the Headquarters, 27 June 1942, Subject: "Personnel for Reorganization of Headquarters, AGF." In 020/73 B2.

[78] Memo for the CofS, USA, 17 March 1942, Subject: "War Department letter SP 320.2(2-22-42), 13 March 1942." Copy in 320.2/1914, with attached papers.

[79] Par 2, Memo for the CofS, USA from Gen McNair, 320.2/302 (AGF) GNDCG, 17 February 1944, Subject: "Organization of the Requirements Division."

[80] John T. Whitaker, "McNair," in These Are the Generals, p. 130.

[81] Ibid.

[82] Ltr Hq AGF 319.22/22 GN GCT to CG’s, 1 January 1943, Subject: "Conduct of Training."

[83] The letter directing the reorganization of July declared that "emphasis will be placed on supervision of directives from this headquarters." Par 4 c, ltr Hq AGF 320.2/8(AGF)(6-24-42), 8 July 1942, Subjects "Organization of the Army Ground Forces."

[84] Par 2 b, ltr Hq AGF 312.11/82(6-25-42)GNDCG, 25 June 1942, Subject: "Paperwork." In 319.22/1.

[85] He made a round of the headquarters once a year, on Christmas Eve. Whitaker was correct in his observation that General McNair was regarded with a kind of hero worship by his staff, though he was seldom seen by any but a few of its members, and was notably shy of publicity.

|

Go to: |

|

|

Last updated 3 May 2005

|