CHART 1

(Click on Image for Full-Size Resolution)

AGF Study, NO. 6: The Procurement and Branch Distribution of Officers

20

SUMMARY OF OFFICER PROCUREMENT

Officer procurement in the Ground Forces was marked by extreme fluctuations in the scope of the program. (These are reflected graphically in Chart I.) It was likewise marked by radical shifts in the branch distribution of officers. (See Table XI.)

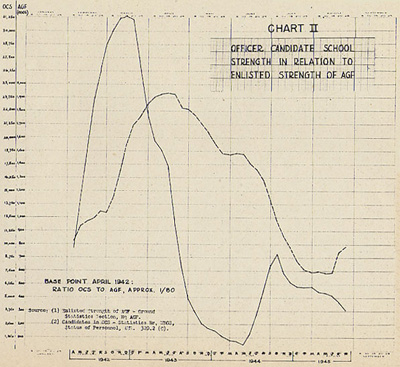

The officer candidate school program, the principal source of new officers during the AGF period, was chronically out of balance with its supporting foundation, the enlisted strength of the Army Ground Forces (See Chart II.) The following observations with respect to Chart II are pertinent: (1) During 1942 the rate of growth of the OCS population considerably exceeded the rate of growth of Army Ground Forces as a whole and officer candidate school reached its peak strength six months before Army Ground Forces. During this period difficulty in finding candidates was most pronounced and decline in quality most noticeable. (2) The officer candidate population declined further and more rapidly than AGF strength during 1943 and 1944. In a reversal of the trend of the previous year, candidates were available in abundance but they could not go to school. (3) As the strength of Army Ground Forces fell most sharply, with deployment of units overseas in 1944, the school population rose once more, with a repetition of the difficulties over quantity and quality encountered in 1942. (4) Only after September 1944 did the strength of officer candidate schools parallel closely the strength of Army Ground Forces. But by this time, AGF strength consisted almost entirely of recent inductees training as replacements, who were considered undesirable as officers.

It was important for several reasons to keep OCS enrollment and enlisted strength generally in balance. The quality of officers produced at officer candidate schools depended primarily on the degree of selectivity that could be exercised in choice of candidates. When, as in 1942 and 1944, OCS input rose high in proportion to the troop strength from which candidates were chosen, selectivity declined and poorly qualified men were sent to school. To maintain the requisite selectivity -- as well as to secure

[35]

candidates in adequate numbers -- it was necessary to go outside the Army to recruit candidates. When on the other hand OCS input fell to extremely low levels, as it did during the second half of 1943 and early 1944, much excellent officer material was wasted. In 1943 men remained in the ranks for lack of opportunity to go to school who were potentially better leaders than the average officer commissioned in 1942. During these periods men continued to be assigned to Army Ground Forces through Selective Service. Small quotas precluded enrollment of all but a minor fraction of new men qualified for officer candidate school. By the time the next great expansion of officer candidate schools took place most of these men were overseas or in alerted units and hence beyond reach. Formal qualifications for officer training often had less bearing on selection than the accident of induction date.

Quantity was almost as important as quality. Provision of officers in the desired quantity was likewise compromised by extreme fluctuations in OCS operations. Large quotas, such as were required by the expansions in 1942 and 1944, were beyond the power of the Ground Forces to fill, either because units were understrength or because units had been sent overseas. During the reverse phase of the cycle, when quotas were small, full use could not be made of regular accessions to AGF strength.

Training in the officer candidate schools suffered when OCS capacities fluctuated widely. The assembly of instructors and facilities for OCS training was a lengthy process; when rapid wholesale expansion was ordered existing facilities and staffs were spread thin and additional plant and instructors had to be thrown together in haste, to the detriment of instruction. Once an extensive plant and an experienced staff were functioning smoothly it was wasteful and inefficient to cut back OCS capacity, disperse staff, and close down facilities, only to repeat the process of hasty expansion a few months later.

Major shifts in the branch distribution of officer strength, most notable in the case of antiaircraft during 1943 and 1944, created undesirable effects. Such shifts were always preceded by surpluses in certain arms and acute shortages in others. The surpluses, being unusable, produced difficulties such as are traced above. The shortages required impromptu measures to augment officer strength in the arms affected, often by drastic increases in OCS capacity. Resolution of problems of surplus and shortage was usually sought in conversion programs. Conversion was in the long run an uneconomical process: much of the officers’ training and experience were wasted and school facilities and staffs were put to an uneconomical use. Large-scale conversion was symptomatic of poor management in officer procurement.

In the absence of a coherent long-range plan of officer procurement, the program was shaped largely by the influence of external conditions. In the light of the foregoing study, the most important of these appear to be the following. They are listed here to illustrate the types of factors that must be taken into account in organizing officer procurement.

1. The initial lack of an officer reserve -- of the regular and civilian components -- distributed by branch in proportion to the needs of mobilization. No armored, tank destroyer, or antiaircraft officers were initially available as such; establishments for training them had to be set up at the last minute. The reserve of infantry officers was far larger, in proportion to mobilization requirements, than the reserve of officers temporarily detailed in the newer "arms."

2. An unexpectedly and excessively rapid mobilization of new units during 1942. The need for men to fill units outran the supply available through Selective Service. Understrength units could furnish officer candidates only at risk to their own training and at expense of quality in OCS material.

[36]

| Capacity of Officer Candidate Schools CHART 1 (Click on Image for Full-Size Resolution) |

[37-38]

|

Officer Candidate School Strength in Relation to Enlisted Strength

of AGF (Click on Image for Full-Size Resolution) |

[39-40]

3. Deceleration of mobilization in late 1943. Deferment of units for which candidates were already in training or were scheduled to go to school resulted by early 1943 in a surplus of officers above actual Troop Basis needs. This surplus grew as planned activations were further curtailed and existing units were inactivated during 1943. Surplus led to curtailment of OCS production. This, in turn, diminished the opportunities for soldiers in the ground arms to obtain commissions, and, while raising the quality of officers produced, excluded from officer candidate school much excellent officer material.

4. Efficient planning required an anticipation of the need for officer replacements. Demands for officer replacements did not immediately supplant demands for officers in new units. The demand for replacements which would have resulted from the cross-channel invasion planned for the spring of 1943, then postponed for a year, did not materialize. The officer surplus which accumulated in 1943 could not be used efficiently because the date when demand for replacements on a large scale would set in could not be predicted, and it was uncertain how far the surplus of officers would go towards cushioning replacement demands on the OCS system. It was undesirable to add to the surplus by maintaining a substantial volume of OCS output. Conversion of OCS facilities to replacement production had to be delayed.

The need for replacements on the scale that eventually became necessary was not anticipated in time to avert a crisis in procurement during 1944. By June 1944, when theater demands for replacements were building up to their greatest peak, officer candidate schools had declined to their lowest output since 1941. Since no large outflow of officers from the schools could be expected until October and November, despite sudden heavy increases in enrollment in June and July, the immediate crisis had to be met by using up the surplus of officers, including those recently converted from other arms to infantry.

5. Late changes in the Troop Basis composition of ground arms strength. Heavy cutbacks in certain arms, especially antiaircraft, not only added to the growing surplus of officers, but had the more serious effect of throwing available officer strength out of balance with probable requirements. The conversion of officers in 1944 grew out of this situation.

6. Lack of a realistic plan for handling the ROTC. While ROTC candidates had to be sent to officer candidate school, under a minimum interpretation of their contracts, the plan governing their admission to officer candidate school had less the appearance of an integral part of the general procurement program than of a series of expedients designed to get the ROTC problem over with as quickly as possible. ROTC men were sent to officer candidate school when there was no genuine need for them. Requirements for officers were so low and pressure to commission the ROTC so high during late 1943 and early 1944 that OCS quotas were allotted almost entirely to the ROTC, soldiers getting very little chance at officer candidate school.

The difficulties listed above were created by shifts in strategic plans and in plans for the organization of the ground arms. Obviously the chances of war and changes in strategy will have to be taken into account in devising any wartime procurement system, and the best-laid plans will be upset by them to some degree. The influence of these external conditions might have been minimized had planning taken into account certain aspects of the procurement system that might have been foreseen and controlled. The most conspicuous defect in the procurement system was its inflexibility. It did not respond quickly to sudden changes in plans. When changed circumstances, such as the demand for replacements in 1944, required accelerated production, months elapsed between the decision to increase output and actual increase in officers available. When production had to be curtailed, as in 1943, months elapsed before the outpouring of candidates could be halted. In either case, crises of overproduction or

[41]

underproduction occurred in the meantime.

The inflexibility was in part inherent in the officer candidate system. To select, train, and prepare an officer for overseas use required a long period, variously estimated at 8 to 12 months. Once enrolled in large numbers, candidates would continue to graduate in large numbers until several months later, regardless of intervening changes in requirements. If current output was low it could not be increased in less than 8 to 12 months no matter how urgent the need for officers became. The inelasticity of the procurement system was to this extent unavoidable.

Some flexibility might have been secured under a less restricted organization of training. Officers were trained in the duties of a particular branch. When,as happened regularly after 1943, the branch distribution of officer strength was found to be out of balance with branch requirements, extensive retraining had to be undertaken. Conversion might have been more rapid, increasing the rate at which surplus officers became usable, if all officers had received identical basic training, specializing in branch duties only after need for officers in a particular branch arose. Such a system would have minimized the dislocations produced by changes in the organization of the ground forces and by the shift from a mobilization to a replacement basis in officer procurement.

Flexibility might also have been gained -- within the time limits imposed by the OCS system -- if resources of candidates had been immediately available when needed to increase output. When quotas were not filled, future output fell below the planned objective, prolonging the inevitable crisis. As long as the bulk of ground strength remained in the United States -- i.e., until early 1944 -- a procurement program which sought to satisfy world-wide requirements out of resources available in the Zone of Interior was feasible, especially while OCS quotas were relatively small. Increasing deployment of AGF strength overseas reduced manpower resources in the United States to levels incapable of supporting a program designed to produce officers to meet worldwide requirements, especially when, as in the second half of 1944, OCS quotas were greatly increased. An overall procurement program was then seen to be necessary.

Either ZI resources should have been tapped for material to meet ZI officer needs only, or Army-wide resources should have been laid under contribution for proportionate shares of the required officer material. The first course was not considered feasible. The second course when finally adapted was attended with difficulties that were not successfully overcome. Production of officers overseas, by direct appointment and by school training, remained low in relation to theater strength. Candidates were returned from inactive theaters in driblets too small to alleviate the shortage in the United States. The bulk of candidates continued to be recruited from the Army at home, with compromises in experience, training, interest, and ability directly comparable to those of late 1942. A procurement program of general scope was not worked out until late 1944. By its terms, overseas theaters after March 1945 were to receive a limited number of officers from the United States and to fill remaining needs from their own resources. Too late to be effective in the crisis of late 1944, this decision could not be implemented because the German offensive of December left most units in Europe grievously short of men, and fighting in Europe came to an end in May.

Given the inevitable delay in the reaction of the procurement system to changed demands it was essential that decisions to alter the size or composition of the officer corps be accurate and timely. Too often major decisions were based on partial information or were delayed while relevant information was compiled. The personnel accounting system, on which decisions had to be based, was inadequate for the tasks required of it. Planners had to know the number, branch distribution, location, and assignment of officers. Information on these points was fragmentary and uncertain. Different

[42]

sets of figures were used by the War Department and by Army Ground Forces in computing officer requirements; even within Headquarters, Army Ground Forces, general agreement on relevant statistical data was lacking. Overseas strength was especially difficult to account for accurately. Army Ground Forces could not check on the use to which replacements were put (although strongly suspecting that they were often used in unauthorized ways). It was impossible to determine whether theaters were understocked or overstocked with replacements. Not until June 1944 was a Strength Reporting and Accounting Office established in the War Department to put personnel accounting on a uniform basis.

A system of accounting for officer strength based on a classification by arms that had actually been superseded increased the confusion. Officers were commissioned in only four legally authorized arms; armored, antiaircraft, and tank destroyer officers were detailed from one of the four. Improvised procedures enabled Army Ground Forces to keep track of officers in all seven arms as long as they were in the United States, but once overseas they could be identified only with difficulty, for they appeared in strength returns under the branch in which commissioned rather than the branch in which serving. A reliable budget of officer strength was almost impossible.

[43]

Go to: |

|

|

|

Last updated 15 September 2005

|