CHAPTER XXIV The Third Army Offensive When the 4th Armored tanks reached the Bastogne perimeter on 26 December, the contact between McAuliffe's command and the Third Army was dramatic and satisfying but none too secure.1 The road now opened from Assenois to Bastogne could be traversed under armed convoy, and for the moment the Germans in this sector were too demoralized by the speed and sharpness of the blow to react in any aggressive manner. The two main highways east and west of the Assenois corridor, however, still were barred by the Seventh Army and such small detachments as could be hurriedly stripped from the German circle around Bastogne. Continued access to Bastogne would have to be insured by widening the breach and securing the Arlon highway-and perhaps that from Neufchâteau as well-before the enemy could react to seal the puncture with his armor. (Map X) The main weight of Gaffey's 4th Armored, it will be recalled, lay to the east of Assenois on the Arlon-Bastogne axis. On the right of the 4th Armored the 26th Infantry Division was echeloned to the southeast and on 26 December had put troops over the Sure River, but the only direct tactical effect this division could have on the fight south of Bastogne would be to threaten the Seventh-Army line of communications and divert German reserves.2 The gap between the 26th Infantry and the 4h Armored Divisions, rather tenuously screened by the 6th Cavalry Squadron, would be filled by the 35th Infantry Division (Maj. Gen. Paul Baade), which had just come up from Metz and had orders to attack across the Sure on 27 December.3 If all went well this attack would break out to the Lutrebois-Harlange road, which fed into the Arlon highway, and proceed thence abreast of the 4th Armored. West of the Assenois corridor the left wing of Gaffey's command was screened, [606] but rather lightly, by scratch forces that General Middleton had gathered from his VIII Corps troops and what remained of Cota's 28th Division. On the afternoon of 26 December General Patton assigned CCA, 9th Armored, which was near Luxembourg City, to the III Corps with orders that it be attached to the 4th Armored and attack on the left to open the Neufchâteau-Bastogne highway. The 9th Armored Division's CCA was relieved that same afternoon by CCA of Maj. Gen. Robert W. Grow's 6th Armored Division. Although the enemy troops around Assenois had been broken and scattered by the lightning thrust on the 26th, the III Corps' attack on the following day met some opposition. The 35th Division, its ultimate objective the Longvilly-Bastogne road, had more trouble with terrain and weather than with Germans, for the enemy had elected to make a stand on a series of hills some five thousand yards beyond the Sure. On the left the 137th Infantry (Col. William S. Murray) trucked through the 4th Armored, crossed the tankers' bridge at Tintange, and moved out cross-country in snow six inches deep. The 2d Battalion drove off the German outpost at the crossroads village of Surré, but to the west the 3d Battalion, defiling along a draw near Livarchamps, came suddenly under fire from a pillbox which checked further movement. The 320th Infantry (Col. Bernard A. Byrne) had to make its own crossings at the Sure, one company wading the icy river, but Boulaide and Baschleiden, on the single road in the regimental zone, were occupied without a casualty. Thence the Battalion pushed on toward the north. In the 4th Armored zone CCR shepherded trucks on the Assenois road while CCB and CCA continued the foot-slogging pace north toward Bastogne. The armored infantry and the two rifle battalions of the 318th marched through the snow, fighting in those woods and hamlets where the German grenadiers and paratroopers-now with virtually no artillery to back them up-decided to make a stand. CCB made its attack from west of Hompré against troops of the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division, here faced about from Bastogne; by nightfall its patrols had reached the 101st Airborne perimeter. CCA, farther from the point of impact on 26 December, had a rougher time although the commanders of the two battalions from the 15th Parachute Regiment confronting the Americans had been captured in battle the previous day. When the 51st Armored Infantry Battalion moved toward the village of Sainlez, perched on a hill to the front, the enemy paratroopers made such good use of their commanding position that the Shermans had to enter the action and partially destroy the village before the German hold was broken. The defenders flushed from Sainlez moved east and struck the 1st Battalion of the 318th, which had cleared Livarchamps, in the rear, starting a fire fight that lasted into the night. American battle casualties in this sector were high on the 27th, and about an equal number of frost bite cases plagued the infantrymen who had now spent six days in the snow and wet. While the 4th Armored and its attached troops pressed forward to touch hands with the Bastogne garrison, the perimeter itself remained in unwonted quiet. General Taylor went into the city to congratulate McAuliffe and resume [607]

SUPPLIES MOVING THROUGH BASTOGNE [608] command of his division.4 Supply trucks and replacements for the 101st rolled through the shell-torn streets. A medical collecting company arrived to move the casualties back to corps hospitals and by noon of the 28th the last stretcher case had left the city. Perhaps the most depressing burden the defense had had to bear during the siege was the large number of seriously wounded and the lack of medical facilities for their care. As early as 21 December the division surgeon had estimated the 101st casualty list as about thirteen hundred, of whom a hundred and fifty were seriously wounded and required surgery. As this situation worsened the Third Army chief of staff, General Gay, made plans on his own responsibility to move surgeons into Bastogne under a white flag, but the successful flight of the Third Army surgeons sent in by liaison plane on the 25th and by glider on the 26th changed the plans and did much to alleviate the suffering in the cellar hospitals of Bastogne. The casualties finally evacuated numbered 964; about 700 German prisoners were also sent out of the city. Uncertainty as to the tenure of the ground corridor resulted in a continuation of the airlift on the 27th. This time 130 cargo planes and 32 gliders essayed the mission, but by now the German ack-ack was alert and zeroed in on the paths of approach. Most of the gliders landed safely, but the cargo planes carrying parapacks suffered heavily on the turnaround over the perimeter; of thirteen C-47's sent out by the 440th Troop Carrier Group only four returned to their base. During the morning of 28 December it became apparent that the German units in front of the III Corps were stiffening. The 35th Division gained very little ground, particularly on the right. On the left the 137th Infantry made slow going over broken ground and through underbrush, the bushes and scrub trees detonating percussion missiles before they could land on the German positions. The 3d Battalion, pinned down in the ravine in column of companies, took nearly all day to work around the irritating pillbox, which finally was destroyed. Thus far the 35th Division, filled with untrained replacements, was attacking without its usual supporting battalion of tanks, for these had been taken away while the division was refitting at Metz. Meanwhile General Earnest, commanding CCA of the 4th Armored, had become concerned with the failure of the 35th to draw abreast on his open east flank, particularly since the rifle battalion borrowed from the 80th Division was under orders to rejoin its parent formation. He therefore asked that the reserve regiment of the 35th (134th Infantry) be put into the attack on his right, with the object of taking Lutrebois, a village east of the Arlon highway. During the night of the 28th the 134th Infantry (Col. Butler B. Miltonberger) relieved the tired troops from the 80th, taking attack positions east of Hompré. The orders were to push any German resistance to the right (that is, away from the Arlon road); thus insensibly the 35th Division was turning to face northeast instead of north with the 320th behind the 137th and the 137th falling into position behind the 134th. This columnar array would [609] have considerable effect on the conduct of the ensuing battle. By Christmas Day it was apparent in both the Allied and German headquarters that the Ardennes battle had entered a new phase and that events now afoot required a fresh look at the grand tactics to be applied as the year drew to its close. The Allied commanders had from the very first agreed in principle that the ultimate objective was to seize the initiative, erase the German salient, and set an offensive in motion to cross the Rhine. There was division in the Allied camp, however, as to when a counteroffensive should be launched and where it should strike into the salient. Beyond this, of course, lay the old argument as to whether the final attack across the Rhine should be on a wide or narrow front, in the British or in the American sector.5 On 25 December the commanders of the two army groups whose troops faced the Germans in the Ardennes met at Montgomery's Belgian headquarters. General Bradley, whose divisions already were counterattacking, felt that the German drive had lost its momentum and that now was the moment to lash back at the attackers, from the north as well as the south. Field Marshal Montgomery was a good deal less optimistic. In his view the enemy still retained the capability to breach the First Army front (a view shared by the First Army G-2, who was concerned with two fresh German armored divisions believed to be moving into the Malmédy sector); the American infantry divisions were woefully understrength; tank losses had been very high; in sum, as Montgomery saw it, the First Army was very tired and incapable of offensive action. Bradley was distressed by Montgomery's attitude and the very next day wrote a personal letter to his old friend, the First Army commander, carefully underscoring the field marshal's authority over Hodges' army but making crystal clear that he, Bradley, did not view the situation "in as grave a light as Marshal Montgomery." As Bradley saw it the German losses had been very high and "if we could seize the initiative, I believe he would have to get out in a hurry." The advice to Hodges, then, was to study the battle with an eye to pushing the enemy back "as soon as the situation seems to warrant." Perhaps, after Bradley's visit, the field marshal felt that he should set the record straight at SHAEF. After a long visit with Hodges on the 26th, he sent a message to Eisenhower saying that "at present" he could not pass to the offensive, that the west flank of the First Army continued under pressure, and that more troops would be needed to wrest the initiative from the Germans. At the moment, however, the Supreme Commander was concerned more with [610] the slowness of the Third Army drive (earlier General Patton had called twice to apologize for the delay in reaching Bastogne) than with an enlargement of the Allied counterattack. In the daily SHAEF staff meeting on the morning of the 26th Eisenhower ruled that General Devers would have to redress the lines of his 6th Army Group by a general withdrawal to the Vosges, thereafter joining his flank to the French north of Colmar. Such regrouping, distasteful as it was, would free two or three American divisions for use in the Ardennes. (It would seem that the SHAEF staff approved the withdrawal of Devers' forces-all save Air Marshal Tedder who did not think the withdrawal justified and argued that Montgomery had British and Canadian divisions which could be freed to provide the needed SHAEF reserve.) 6 The lower echelon of Allied commanders was meanwhile stirring restively. Having reached Bastogne late on the 26th, Patton set his staff to work on plans for a prompt redirection of the Third Army attack. On the 27th General Collins arrived at the First Army command post with three plans for an attack led by the VII Corps, two aimed at a junction with Patton in the Bastogne sector, one with St. Vith, deeper in the salient, as the objective. Collins' proposals posed the problem of grand tactics now at issue-should the German salient be pushed back from the tip or should it be cut off close to the shoulders-but it remained for Patton, the diligent student of military history, to state in forthright terms the classic but venturesome solution. Arguing from the experiences of World War I, the Third Army commander held that the Ardennes salient should be cut off and the German armies engulfed therein by a vise closing from north and south against the shoulders of the Bulge. Thus the Third Army would move northeast from Luxembourg City toward Bitburg and Prüm along what the Third Army staff called the "Honeymoon Trail." General Smith, the SHAEF chief of staff, was in agreement with this solution, as were Hodges, Gerow, and Collins-in principle. The salient at its shoulders was forty miles across, however, and a successful amputation would necessitate rapid action by strong armored forces moving fast along a good road net. The First Army commanders, as a result, had to give over this solution because the road complex southeast of the Elsenborn Ridge, which would be the natural First Army axis for a cleaving blow at the German shoulder, could not sustain a large attack force heavy in armor-hence Collins' compromise suggestion for an attack from a point north of Malmédy toward St. Vith.7 How would the two army group commanders react to the pressures being brought to bear by their subordinates? Bradley was concerned with the vagaries of the winter weather, which could slow any counterattack to a walk, and by the lack of reserves. He may also have been uncertain of his air support. Bad flying weather was a distinct possibility, and the Eighth Air Force-a rather independent command-was increasingly disenchanted with its battlefield [611] missions over the Ardennes (indeed, on 27 December the Eighth Air Force had stated its intention of scrubbing the battle zone targets and going after the Leipzig oil depots, weather permitting). Bradley decided therefore to settle for half a loaf and on the 27th briefed the Supreme Commander on a new Third Army attack to be mounted from the Bastogne area and to drive northeast toward St. Vith. Bradley was careful to add that this plan was not Patton's concept of a drive against the south shoulder. There remained Montgomery's decision. By the 27th he was ready to consider definite counterattack plans. When this word was relayed to Eisenhower at his daily staff meeting it elicited from him a heartfelt "Praise God from Whom all blessings flow!" and the Supreme Commander set off at once to meet the field marshal in Brussels. Hodges, Collins, and Ridgway did their best in the meantime to convince Montgomery that the First Army attack should be initiated not around Celles, as the field marshal had first proposed, but farther to the east. On the evening of 28 December Eisenhower phoned General Smith from Brussels and told him that he saw great possibilities in a thrust through the Bastogne-Houffalize area. As it turned out, this would be the maneuver ultimately adopted. Perhaps the field marshal had given Eisenhower reason to think that the First Army would make its play in a drive on Houffalize; perhaps-and this seems more likely-Montgomery still had not made any final decision as to the place where the counterattack would be delivered. Certainly no time had been set although 4 and 5 January had been discussed as possible target dates. Hodges and Collins continued to press for a decision to get the attack from the north flank rolling-the prospects for which brightened when the British offered the loan of two hundred medium tanks. Meanwhile the new Third Army attack against the south flank commenced. On the last day of December, the serious prospect of bad weather outweighed by the fact that the Germans were thinning the First Army front to face the Third, Montgomery gave his decision and Hodges consented: the VII Corps, followed by the XVIII Airborne Corps, would attack toward Houffalize and St. Vith respectively on 3 January.8 Eisenhower's telephone call from Brussels on the 28th released the 11th Armored and 87th Infantry Divisions from the SHAEF reserve for use by Bradley. That night Patton met with the VIII and III Corps commanders to lay out the new plan for continuation of the Third Army attack. Middleton's VIII Corps would jump off from the Bastogne area on the morning of 30 December, its objective the high ground and road nexus just south of Houffalize. Millikin's III Corps would move into the attack on 31 December, driving in the direction of St. Vith. The initial pressure on the salient would be exerted much farther to the west than Patton wished. Bradley made doubly sure that the Third Army would indeed place its weight as planned by telling Patton that the two fresh divisions could be employed only by the VIII Corps. But the Third Army commander [612] put his cherished concept into the army operations order by means of a paragraph which called for the XII Corps to be prepared for an attack across the Sauer River and northeast through the Prüm valley-ultimate objective the Rhine River crossings at Bonn as the entire Third Army swung northeast. On Christmas Day the German commanders sensed, as their opponents across the line had done, that they were at a turning point in the Ardennes battle. How should the higher commanders now intervene to influence the course of battle, or, more accurately, could they intervene? Manteuffel's plan was to make the suit fit the cloth: put enough new troops in to take Bastogne, then swing the left flank of the Fifth Panzer Army toward the Meuse and fight the Allies east of the river-the old Small Solution. Field Marshal Model agreed that Bastogne must be taken and that additional troops would be needed for the task, but the only armor immediately available was the Fuehrer Begleit Brigade and he had just extricated this unit from the Manhay fight to give added weight to the Fifth Panzer Army drive against the American line on the Ourthe River. As it turned out, Remer's brigade arrived in the Ourthe sector only a few hours before the Americans broke through to Bastogne. It had time to put in only one probing assault when Model, on the late afternoon of the 26th, sent the Fuehrer Begleit again on its travels, this time countermarching to seal the gap in the Bastogne ring with a riposte between Sibret and Hompré. Model and Rundstedt seem to have agreed on a plan of action which may or may not have had the Fuehrer's approval (there is no record). The Fifth and Sixth would seek to destroy the Allied forces east of the Meuse while the Seventh held on as best it could; as a first step an attack would be made to eradicate the Americans in the Bastogne area.9 Obviously the German lines would have to be shortened somewhere, and Model, directly under Hitler's baleful eye, dare not surrender ground. This responsibility fell to the Fifth Panzer Army commander, who on 26 December (with tacit approval from Model at every step) set about creating a defensive front in the west roughly following the triangular outline Bastogne-Rochefort-Amonines. The battered 2d Panzer Division was brought back through the Rochefort bridgehead and troops from the 9th Panzer took over from Panzer Lehr in the Rochefort area, the latter sidestepping toward the southeast so that one flank finally would lie on the Lesse River with the other [613] fixed at Remagne, five miles west of the Neufchâteau-Bastogne highway. The LVIII Panzer Corps, possibly as a sop to Hitler, was allowed to continue its fruitless attacks in the Ourthe sector, but with the Fuehrer Begleit out of the picture these quickly dwindled away. Manteuffel made his old comrade Luettwitz responsible for the defensive western front and took a new corps headquarters, which had been sent up from the OKW reserve, to handle the Bastogne operation. This, the XXXIX Panzer Corps, was commanded by Generalleutnant Karl Decker, a very experienced officer with a reputation for prudence combined with determination. Decker, despite protests by Luettwitz, was placed under the latter, and for a few days the German order of battle would show an "Army Group Luettwitz." Manteuffel counted on the Fuehrer Begleit to carry the main burden of the counterattack south of Bastogne. The brigade had about forty Mark IV tanks plus an assault gun brigade of thirty tubes, and its infantry had not been bled white as in the rest of the armored formations. In addition, Manteuffel had been promised the beat-up 1st SS Panzer Division, the 3d Panzer Grenadier Division, and the Fuehrer Grenadier Brigade, parts of these formations being scheduled to reach Decker on 28 December. Advance elements of the Fuehrer Begleit did arrive that morning, taking station in the Bois de Herbaimont north of the Marche-Bastogne road, but the Allied Jabos were in full cry over the battlefield and Remer could not bring all his troops forward or issue from the forest cover. Time was running out for the Germans. As early as the night of the 27th Rundstedt's staff believed that unless Remer could make a successful attack at once it was "questionable" whether the Bastogne gap could be sealed. Manteuffel later would say that this job could have been done only by counterattacking within forty-eight hours. On both sides of the hill, then, the troops were being moved for a set piece attack on 30 December. Would either opponent anticipate the ensuing collision? German intelligence officers did predict that the 6th Armored Division soon would appear between the III and XII Corps. The OB WEST report of 27 December reads: "It is expected that the units of the Third Army under the energetic leadership of General Patton will make strong attacks against our south flank." Within twenty-four hours this view altered: The First Army was said to be having difficulty regrouping and still showed defensive tendencies; therefore, even though the Third Army was in position to attack, it probably would not attack alone.10 The American intelligence agencies had practically no knowledge of any German units except those immediately in contact. Of course some kind of counterattack was expected, but this, it was believed, would come when bad weather cut down friendly air activity. The weather did turn foul late on the 28th and the word went out in the American camp: Prepare for an armored counterattack, enemy tanks are in movement around Bastogne. [614] While the Fuehrer Begleit Brigade was assembling, General Kokott did what he could to gather troops and guns in the sector west of Assenois and there make some kind of a stand to prevent the tear in the Bastogne noose from unraveling further. The key villages in his original defense plans were Sibret and Villeroux, overwatching as they did the Neufchâteau-Bastogne highway. Kokott could expect no help from the 5th Parachute Division, originally entrusted with the blocking line in this area, for on the night of 26 December an officer patrol reported that not a single paratrooper could be found between Sibret and Assenois. Kokott's own division, the 26th Volks Grenadier, and its attached battalions from the 15th Panzer Grenadier had taken very heavy losses during the western attack against the 101st Airborne on Christmas Day. The rifle companies were down to twenty or thirty men; most of the regimental and battalion commanders and executive officers were dead or wounded; a number of heavy mortars and antitank guns had been sent back to the divisional trains because there was no more ammunition; and the only rifle replacements now consisted of what Kokott called "lost clumps" of wandering infantry. When CCA of the 9th Armored Division (Col. Thomas L. Harrold) got its orders on the 26th to come forward on the left flank of the 4th Armored and attack toward Sibret, there was more at stake than defending the corridor just opened through the German lines. General Middleton was already busy with plans for his VIII Corps to join the Third Army attack beyond Bastogne and, with the memories of the traffic congestion there early in the fight still fresh in mind, was most unwilling to drag the VIII Corps through the Bastogne knothole in the forthcoming advance. Middleton convinced Bradley and Patton that the VIII Corps should make its drive from a line of departure west of Bastogne, and for this the Neufchâteau road first had to be opened and the enemy driven back to the northwest. When CCA started down the Neufchâteau road on the morning of the 27th, it faced a catch-as-catch-can fight; no one knew where the enemy might be found or in what strength. Task Force Collins (Lt. Col. Kenneth W. Collins), in the lead, was held up some hours by mines which had been laid north of Vaux-lez-Rosières during the VIII Corps' withdrawal; so Task Force Karsteter (Lt. Col. Burton W. Karsteter) circled to head for Villeroux, leaving Task Force Collins to take Sibret. Karsteter, who had two medium tank companies, got into Villeroux, but night was coming and the tanks were not risked inside the village. Collins sent his single company of Shermans into Sibret, firing at everything in sight. The Americans could not be said to hold the village, however, for a small detachment of the 104th Panzer Grenadier Regiment was determined to make a fight of it and did. It took all night to drive the German grenadiers out of the cellars and ruined houses. During the night of 27 December the Germans put more men into Villeroux (the 39th Regiment was slowly building up a semblance of a front) but to no avail. American artillery and [615] Allied fighter-bombers shattered the village, and Karsteter finished the job with his tanks. Task Force Collins was delayed on the 8th by a formidable ground haze which lingered around Sibret all morning. Halfway to its next objective, the crossroads at Chenogne north of Sibret, the American column came under enfilading fire from a small wood lot close to the road. The tank company turned to deal with this menace and finally suppressed the German fire, but light was fading and the column laagered where it was. In the meantime General Kokott had gathered a counterattack force, a company of the division Pioneers, to retake Sibret. While at breakfast on the 29th eating K rations on the tank decks and in foxholes beside the road, Collins' troops suddenly saw a body of men march out of the nearby woods. An American captain shouted out and the leading figure replied, "Good morning"-in German. The Americans cut loose with every weapon, to such effect that some fifty dead Germans were counted, lying in column formation as they had fallen. Late in the day, however, the fortunes of war turned against the Americans. Collins' tanks had moved through the village square in Chenogne and were approaching a road junction when high velocity shells knocked out the two lead tanks. Then, in a sharp exchange of shots, the enemy gunners accounted for two more of the Shermans, and the Americans withdrew. They could not discover the exact enemy locations in the twilight but were sure they were facing tanks. That night, the VIII Corps artillery reported, it "blew Chenogne apart." While Task Force Collins was engaged on the road to Chenogne, Task Force Karsteter also was moving north, its objective Senonchamps, the scene of hard fighting in previous days and a sally port onto the main road running west from Bastogne to Marche. Here Task Force Karsteter was unwittingly threatening the assembly area of the Fuehrer Begleit which lay in the woods north of the highway, none too securely screened by remnants of the 3d Battalion of the 104th Panzer Grenadier around Chenogne. Remer's brigade already had taken some share in the action against CCA and one of his 105-mm. flak pieces was responsible for holding up Task Force Collins in the fight at the roadside woods, continuing in action until it was rammed by a Sherman tank. Not far out of Villeroux, Task Force Karsteter came under hot and heavy fire from the Bois de Fragotte, lying over to the northwest. What the Americans had run into was the main body of the 3d Panzer Grenadier Division. Losses among the armored infantry were very high, and that night a liaison officer reported that the task force front was "disorganized." Four of Karsteter's tanks ran the gauntlet of fire from the woods and entered Senonchamps, but the infantry failed to follow. The cumulative losses sustained by CCA in the three-day operation had been severe and it was down to a company and a half of infantry, although 21 medium and 17 light tanks still were operable.11 [616] The grand tactics of the two opponents had been solved-at least on the planning maps-by set-piece attacks in the Bastogne sector which were scheduled to commence on or about 30 December. This date was firm insofar as the American Third Army was concerned. In the German camp the date was contingent on the caprices of the weather, traffic congestion on the roads running into the area, the damage which might be inflicted by the Allied fighter-bombers, and the uncertainty attached to the arrival of fuel trucks coming forward from the Rhine dumps. The two attacks nevertheless would be launched on 30 December. Middleton's VIII Corps, scheduled to provide the American curtain-raiser thrust on the left wing of Patton's army, took control of the 101st Airborne Division and the 9th Armored Division the evening before the attack began. Although General Taylor's paratroopers and glider infantry would play no offensive role in the first stages of the Third Army operation, they had to hold the pivot position at Bastogne and provide couverture as the scheme of maneuver unfolded. Of the 9th Armored commands only CCA, already committed, could be used at the onset of the VIII Corps advance toward Houffalize. On the morning of the 30th, then, the corps order of battle (east to west) would be the 101st, CCA of the 9th Armored, the 11th Armored Division, and the 87th Infantry Division, with these last two divisions designated to make the main effort. The 11th Armored (General Kilburn) had been hurried from training in the United Kingdom to shore up the Meuse River line if needed and had some cavalry patrolling on the east bank when Eisenhower turned the division over to Bradley. Late on the evening of the 28th General Kilburn received orders from Middleton to move his division to the Neufchâteau area, and two hours after midnight the 11th Armored began a forced march, the distance about eighty-five miles. The heavy columns were slowed by snow, ice, and the limited-capacity bridge used to cross the Meuse, but CCA, in the van, reached the new assembly area a couple of hours before receiving the corps attack order issued at 1800. CCB and the remainder of the division were still on the road. Some units of this green division would have to go directly from the march column into the attack, set for 0730 the next morning. There was no time for reconnaissance and the division assault plan had to be blocked out with only the hastily issued maps as guidance. The general mission given the 11th Armored-and the 87th as well-was to swing west around Bastogne, capture the heights south of Houffalize, and secure the Ourthe River line. The first phase, however, was a power play to drive the enemy back to the north in an assault, set in motion from the Neufchâteau-Bastogne road, which would sweep forward on the left of CCA, 9th Armored. General Kilburn wanted to attack with combat commands solidly abreast, but the VIII Corps commander, concerned by the thought of exposing [617]

11TH ARMORED DIVISION HALF-TRACKS MASSED on the outskirts of Bastogne. the relatively untested 87th without tank support, ordered Kilburn to divide his force so as to place one combat command close to the new infantry division. Thus the 11th Armored would make its initial drive with CCB (Col. Wesley W. Yale) passing east of a large woods-the Bois des Haies de Magery-and CCA Brig. Gen. Willard A. Holbrook, Jr.) circling west of the same. The 87th Infantry Division (Brig. Gen. Frank L. Culin, Jr.) had arrived on the Continent in early December and been briefly employed as part of the Third Army in the Saar offensive. Ordered into the SHAEF reserve at Reims on 24 December, the division was at full combat strength when, five days later, the order came to entruck for the 100-mile move to the VIII Corps. There the 87th assembled between Bertrix and Libramont in preparation for an advance on the following morning to carry the corps left wing north, cut the Bastogne-St. Hubert road, and seize the high ground beyond. Middleton's two division attack would be well stiffened by ten battalions of corps artillery. Across the lines, on the afternoon of 29 December, General Manteuffel called his commanders together. Here were the generals who had carried the Bastogne fight thus far and generals of the divisions moving into the area, now including three SS commanders. Manteuffel, it is related, began the conference [618] with some critical remarks about the original failure to apprehend the importance of Bastogne. He then proceeded to tell the assemblage that the Ardennes offensive, as planned, was at an end, that Bastogne had become the "central problem," and that the German High Command viewed the forthcoming battle as an "opportunity," an opportunity to win a striking victory or at the least to chew up the enemy divisions which would be poured into the fight. The operation would be in three phases: first, close the ring once again around Bastogne; second, push the Americans back to the south; third, with reinforcements now on the way, take Bastogne in a final assault. Army Group Luettwitz would conduct the fight to restore the German circle with the XXXIX and XLVII Panzer Corps, the first attacking east to west, the second striking west to east. A number of the divisions en route to Bastogne had not yet arrived and the attack set for the 30th would be neither as strong nor as coordinated as Manteuffel would wish, but he was under pressure from his superiors and could entertain no further delay. The eastern assault force comprised the much understrength and crippled 1st SS Panzer and the 167th Volks Grenadier Divisions; its drive was to be made via Lutrebois toward Assenois. The attack from the west would be spearheaded by the Fuehrer Begleit advancing over Sibret and hammering the ring closed. The 3d Panzer Grenadier Division was to advance in echelon to the left of Remer's brigade while the remnants of the 26th Volks Grenadier Division and 15th Panzer Grenadier Division screened to the west and north of Bastogne. The timing for the arrival of the incoming reinforcements-the 12th SS Panzer, the 9th SS Panzer, and the 340th Volks Grenadier Divisions-was problematical. Generalmajor Walter Denkert, commanding the 3d Panzer Grenadier Division, planned to attack at 0730 on 30 December because of the predisposition the Germans had noted (and on which they had capitalized many times) for the Americans to delay the start of the day's operations until about eight or nine o'clock in the morning. His division expected to move south through the Bois de Fragotte (between Chenogne and Senonchamps), then swing southeast to retake Villeroux. The attack plan was intended to pave the way for Remer's brigade (attached to the 3d Panzer Grenadier Division since Denkert was the senior commander) to seize Sibret and permit the combined force to debouch against Assenois and Hompré. The Americans, as it turned out, were not as dilatory as had been anticipated-both their attack divisions were moving north by 0730. Remer also kept to his time schedule. The Fuehrer Begleit advance was geared for a one-two punch at Sibret. The battalion of Remer's panzer grenadiers, which had clashed briefly with Task Force Collins in Chenogne the previous evening, moved out over the snow-covered fields to pry an opening on the north edge of Sibret, while the Fuehrer Begleit tank group-carrying a battalion of grenadiers-waited in Chenogne to move forward on a parallel trail which passed through Flohimont [619] and entered Sibret from the west. A dense ground fog covered the area for a few hours, masking the opposing forces from one another. The grenadier battalion made some progress and drove Task Force Collins back toward Sibret, but the battalion commander was killed and the advance slowed down. Remer's tank group was nearing Flohimont when the fog curtain raised abruptly to reveal about thirty American tanks. Colonel Yale had divided CCB of the 11th Armored into a tank force (Task Force Poker) and an infantry task force (Task Force Pat). Task Force Pat, essentially the 21st Armored Infantry Battalion, had marked Flohimont on the map as its line of departure but in the approach march became confused. Communications failed, and the reconnaissance troops in the van of CCB got lost and fell back on Task Force Pat. Adding menace to confusion the German artillery began to pound the Jodenville-Flohimont road along which the attack was directed. Meanwhile the reinforced 41st Tank Battalion (Task Force Poker), which had picked Lavaselle from the map as its goal, rolled north with little opposition and reached its objective about a mile and a half west of Chenogne. These were the American tanks seen by Remer. Lavaselle turned out to be located in a hollow, hardly a place for armor, and the task force commander (Maj. Wray F. Sagaser) decided to move on to the villages of Brul and Houmont which occupied some high ground just to the north. There was a creek to cross with a single rickety bridge, but the tanks made it. The twin hamlets were defended only by a few infantry and fell easily-then intense rocket and mortar fire set in. Task Force Poker was on its own, well in front of the rest of the 11th Armored, uncertain that its sister task force would succeed in forging abreast at Chenogne, and with night coming on. Remer apparently decided to forgo a test of strength with the American armor moving past in the west, his mission being to attack eastward, but when word reached him that the Americans had hit the outpost at Lavaselle he hurried in person to check the security screen covering the western flank. Here one of Remer's panzer grenadier battalions had thrown forward an outpost line extending as far west as Gerimont and backed by a concentration of flak, assault guns, and mortars in the Bois Des Valets to the north of and about equidistant from Houmont and Chenogne. Satisfied that this groupment could hold the enemy, Remer returned to Chenogne. He found that the village had been bombarded by planes and guns till it was only a heap of stones with a handful of grenadiers garrisoning the rubble. Remer instantly sent a radio SOS to the commander of the 3d Panzer Grenadier, then set out to find his tank group. When the bombardment started at Chenogne, the German tanks still there simply had pulled out of the village. About the same time, Task Force Pat resumed its march on Chenogne, Company B of the 22d Tank Battalion leading and the armored infantry following in their half-tracks. Near the village, in a lowering fog, the German armor surprised the company of Shermans and shot out seven of them. The enemy allowed the American aid men to carry away the surviving tankers and both sides fell back. As dusk came Remer set about pulling his command together, and the [620] 3d Panzer Grenadier-heeding his call for assistance-moved troops into the ruins of Chenogne.12 This division had taken little part in the day's activity, probably because of the intense shelling directed on its assembly area in the Bois de Fragotte by the 4th Armored and corps artillery, the cross fire laid down from Villeroux by the tanks of Task Force Karsteter, and the uncertainty of Remer's situation. The western advance on 30 December by CCA of the 11th Armored met almost no resistance during the first few hours, in part because the 28th Cavalry Squadron had driven the German outpost line back on Remagne. The immediate objective, Remagne, was the anchor position for the left wing of the new and attenuated Panzer Lehr position, but this division had just completed its shift eastward and had only small foreposts here. One of these, in the hamlet of Rondu about a mile and a half south of Remagne, seems to have flashed back warning of the American approach. In any case the 63d Armored Infantry Battalion, leading the march as Task Force White, had just come onto the crest of the ridge beyond Rondu when, as the men on the receiving end vividly recall, "All hell broke loose." The two tanks at the point of the column were hit in one, two order. The armored infantry took a hundred casualties in thirty minutes while digging madly in the frozen ground. Task Force Blue (the 42d Tank Battalion) was shielded by the ridge and received little fire. Since the 87th Division had not yet come up on the left, the 41st Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron moved around to the west flank in anticipation of a German counterthrust. It was midafternoon. German high velocity guns were sweeping the ridge, and there was no room for maneuver: the Ourthe lay to the west and the Bois Des Haies de Magery spread to the east, separating CCA and CCB. General Kilburn asked the corps commander to assign Remagne to the 87th and let CCA sideslip to rejoin CCB east of the woods. Middleton agreed and a new maneuver was evolved for 31 December in which all three combat commands of the 11th Armored would attack to concentrate at the head of the Rechrival valley, thus following up the drive made by Task Force Poker. An hour before midnight CCA began its withdrawal. On the left wing of the VIII Corps the assault units of the 87th Division were trucked northward on the morning of 30 December to the line of departure in the neighborhood of Bras, held by the 109th Infantry.13 Since the first major objective was to sever the German supply route along the St. Hubert-Bastogne road the attack was weighted on the right, with the 345th Infantry (Col. [621] Douglas Sugg) aiming for a sharp jog in the road where stood the village of Pironpré. On the left the 346th Infantry (Col. Richard B. Wheeler) had a more restricted task, that is, to block the roads coming into St. Hubert from the south. Earlier the Panzer Lehr had outposted Highway N26, the 345th route of advance, but apparently these roadblock detachments had been called in and Sugg's combat team marched the first five miles without meeting the enemy. The advance guard, formed by the 1st Battalion (Lt. Col. Frank L. Bock), was within sight of the crossroads village of Moircy and less than two miles from the objective when a pair of enemy burp guns began to chatter. This was only outpost fire, and the leading rifle company moved on until, some five hundred yards short of Moircy, the enemy fire suddenly thickened across the open, snow-covered fields, causing many casualties and halting the Americans. The accompanying cannoneers (the 334th Field Artillery) went into action, the mortar crews started to work, and both Companies A and B deployed for the assault. Short rushes brought the rifle line forward, though very slowly. By 1400 the Americans were on the edge of Moircy, but the two companies had lost most of their officers and their ranks were riddled. Colonel Bock ordered his reserve company to circle west of the village and take the next hamlet, Jenneville. While moving over a little rise outside Jenneville, the leading platoon met a fusillade of bullets that claimed twenty casualties in two minutes. Nevertheless the 2d Platoon of Company C reached the edge of the village. At this moment two enemy tanks appeared, stopped as if to survey the scene, then began to work their machine guns. The artillery forward observer crawled toward the panzers to take a look, and was shot. The Company C commander then called for the artillery, bringing the exploding shells within fifty yards of his own men. The German tanks still refused to budge. Two men crept forward with bazookas, only to be killed by the tank machine guns, but this episode apparently shook the tank crews, who now pulled out of range. Meanwhile Moircy had been taken and the battalion commander told Company C to fall back. The expected German counterattack at Moircy came about three hours before midnight. Tanks pacing the assault set fire to the houses with tracer bullets, and the two battalion antitank guns were abandoned. Although Colonel Sugg ordered the battalion out, the company radios failed and in the confusion only Companies A and B left the village. Some of the machine gunners, a platoon of Company B, and most of Company C stayed on, taking to the cellars when the American artillery-including a battery of 240-mm. howitzers-started to shell Moircy. By midnight the Germans had had enough and evacuated the village. Bock then ordered the remaining defenders out. This day of sharp fighting cost the 1st Battalion seven officers and 125 men. Most of the wounded were evacuated, however; during the night battle in Moircy one aid man had twice moved the twelve wounded in his charge from burning buildings. The much touted Fuehrer Begleit attack failed on the 30th to dent the Bastogne corridor-indeed it can be said that it never started. What of the eastern [622] jaw of the hastily constructed German vise-the 1st SS Panzer attack? The 1st SS Panzer was still licking its wounds after the disastrous fight as advance guard of the Sixth Panzer Army, when Model ordered the division to move south, beginning 26 December. Most of its tanks were in the repair shops, fuel was short, and some units did not leave for Bastogne until the afternoon of the 29th. This march was across the grain of the German communications net and became badly snarled in the streets of Houffalize, where Allied air attacks had caused a major traffic jam, that forced tank units to move only in small groups. It is probable that fewer than fifty tanks reached the Bastogne area in time to take part in the 30 December attack. The appearance of this SS unit was greeted by something less than popular acclaim. The regular Army troops disliked the publicity Goebbels had lavished on the feats of the SS divisions and the old line commanders considered them insubordinate. Worse still, the 1st SS Panzer Division came into the sector next to the 14th Parachute Regiment: the SS regarded themselves-or at least were regarded-as Himmler's troops, whereas the parachute divisions were the personal creation of Goering. (It is not surprising that after the attack on the 30th the 1st SS Panzer tried to bring the officers of the 14th before a Nazi field court.) 14 The 167th Volks Grenadier Division (Generalleutnant Hans-Kurt Hoecker), ordered to join the 1st SS Panzer in the attack, was looked upon by Manteuffel and others with more favor. This was a veteran division which had distinguished itself on the Soviet front. The 167th had been refitting and training replacements from the 17th Luftwaffe Feld Division when orders reached its Hungarian casernes to entrain for the west. On 24 December the division arrived at Gerolstein on the Rhine; though some units had to detrain east of the river, Hoecker's command was at full strength when it began the march to Bastogne. A third of the division were veterans of the Russian battles, and in addition there were two hundred picked men who had been officer candidates before the December comb-out. Hoecker had no mechanized heavy weapons, however, and the division transport consisted of worn-out Italian trucks for which there were no spare parts. The 167th and the kampfgruppe from the 1st SS Panzer (be it remembered the entire division was not present on the 30th) were supposed to be reinforced by the 14th Parachute Regiment and the 901st of the Panzer Lehr. Both of these regiments were already in the line southeast of Bastogne, but were fought-out and woefully understrength. The first plan of attack had been based on a concerted effort to drive straight through the American lines and cut the corridor between Assenois and Hompré. Just before the attack this plan was modified to make the Martelange-Bastogne highway the initial objective. The line of contact on the 30th extended from Neffe south into the woods east of Marvie, then followed the forest line and the Lutrebois-Lutremange road south to Villers-la-Bonne-Eau. The boundary between the 167th and the 1st SS Panzer ran through Lutrebois. The 167th, lined up in the north along the Bras-Bastogne road, would [623]

35TH INFANTRY DIVISION MACHINE GUN POSITION south of Bastogne. aim its assault at the Remonfosse sector of the highway. The 1st SS Panzer, supported on the left by the 14th Parachute Regiment, intended to sally out of Lutrebois and Villers-la-Bonne-Eau. Lutrebois, however, was captured late in the evening of the 29th by the 3d Battalion of the 134th Infantry. A map picked up there by the Americans showed the boundaries and dispositions of the German assault forces, but either the map legend was unspecific or the word failed to get back to higher authority for the German blow on the morning of 30 December did achieve a marked measure of tactical surprise. The 35th Infantry Division stood directly in the path of the German attack, having gradually turned from a column of regiments to face northeast. The northernmost regiment, the 134th Infantry, had come in from reserve to capture Lutrebois at the request of CCA, 4th Armored, but it had only two battalions in the line. The 137th Infantry was deployed near Villers-la-Bonne-Eau, and on the night of the 29th Companies K and L forced their way into the village, radioing back that they needed bazooka ammunition. (It seems likely that the Americans shared Villers with a company of German Pioneers.) In the south the 320th Infantry had become involved in a bitter fight around a farmstead outside [624] of Harlange-the German attack would pass obliquely across its front but without impact. During the night of 29 December the tank column of the 1st SS Panzer moved up along the road linking Tarchamps and Lutremange. The usable road net was very sparse in this sector. Once through Lutremange, however, the German column could deploy in two armored assault forces, one moving through Villers-la-Bonne-Eau, the other angling northwest through Lutrebois. Before dawn the leading tank companies rumbled toward these two villages. At Villers-la-Bonne-Eau Companies K and L, 137th Infantry, came under attack by seven tanks heavily supported by infantry. The panzers moved in close, blasting the stone houses and setting the village ablaze. At 0845 a radio message reached the command post of the 137th asking for the artillery to lay down a barrage of smoke and high explosive, but before the gunners could get a sensing the radio went dead. Only one of the 169 men inside the village got out, Sgt. Webster Phillips, who earlier had run through the rifle fire to warn the reserve company of the battalion west of Villers. The battle in and around Lutrebois was then and remains to this day jumbled and confused. There is no coherent account from the German side and it is quite possible that the formations involved in the fight did not, for the reasons discussed earlier, cooperate as planned. The American troops who were drawn into the action found themselves in a melee which defied exact description and in which platoons and companies engaged enemy units without being aware that other American soldiers and weapons had taken the same German unit under fire. It is not surprising, then, that two or three units would claim to have destroyed what on later examination proves to have been the same enemy tank detachment and that a cumulative listing of these claims-some fifty-odd German tanks destroyed-probably gives more panzers put out of action than the 1st SS Panzer brought into the field. It is unfortunate that the historical reproduction of the Lutrebois fight in the von Rankian sense ("exactly as it was") is impossible, for the American use of the combined arms in this action was so outstanding as to merit careful analysis by the professional soldier and student. The 4th Armored Division artillery, for example, simultaneously engaged the 1st SS Panzer in the east and the 3d Panzer Grenadier in the west. Weyland's fighter-bombers from the XIX Tactical Air Command intervened at precisely the right time to blunt the main German armored thrust and set up better targets for engagement by the ground forces. American tanks and tank destroyers cooperated to whipsaw the enemy assault units. The infantry action, as will be seen, had a decisive effect at numerous points in the battle. Two circumstances in particular would color the events of 30 December: because of CCA's earlier interest in Lutrebois, radio and wire communications between the 4th Armored and the 35th Division were unusually good in this sector; although the 35th had started the drive north without the normal attachment of a separate tank battalion, the close proximity of the veteran 4th Armored more than compensated for this lack of an organic tank-killing capability. [625] Lutrebois, two and a half miles east of the German objective at Assenois, had most of its houses built along a 1,000-yard stretch of road which runs more or less east and west across an open plain and is bordered at either end by an extensive wooded rise. On the morning of the 30th the 3d Battalion of the 134th Infantry (Lt. Col. W. C. Wood) was deployed in and around the village: Company L was inside Lutrebois; Companies I and K had dug in during the previous evening along the road east of the village; the battalion heavy machine guns covered the road west of the village. To the right, disposed in a thin line fronting on the valley, was the d Battalion (Maj. C. F. McDannel). About 0445-the hour is uncertain-the enemy started his move toward Lutrebois with tanks and infantry, and at the same time more infantry crossed the valley and slipped through the lines of the 2d Battalion. As the first assault force crossed the opening east of Lutrebois, the American cannoneers went into action with such effect as to stop this detachment in its tracks. The next German sortie came in a hook around the north side of Lutrebois. Company L used up all of its bazooka rounds, then was engulfed. The German grenadiers moved on along the western road but were checked there for at least an hour by the heavy machine guns. During this midmorning phase seven enemy tanks were spotted north of Lutrebois. A platoon of the 654th Tank Destroyer Battalion accounted for four, two were put out of action by artillery high explosive, and one was immobilized by a mine. News of the attack reached CCA of the 4th Armored at 0635, and General Earnest promptly turned his command to face east in support of the 35th Division. By 1000 General Dager was reshuffling CCB to take over the CCA positions. The first reinforcement dispatched by CCA was the 51st Armored Infantry Battalion, which hurried in its half-tracks to back up the thin line of the 2d Battalion. Here the combination of fog and woods resulted in a very confused fight, but the 2d Battalion continued to hold in its position while the enemy panzer grenadiers, probably from the 2d Regiment of the 1st SS Panzer, seeped into the woods to its rear. The headquarters and heavy weapons crews of the 3d Battalion had meanwhile fallen back to the battalion command post in the Losange château southwest of Lutrebois. There the 51st Armored Infantry Battalion gave a hand, fighting from half-tracks and spraying the clearing around the château with .50-caliber slugs. After a little of this treatment the German infantry gave up and retired into the woods. During the morning the advance guard of the 167th Volks Grenadiers, attacking in a column of battalions because of the constricted road net, crossed the Martelange-Bastogne road and reached the edge of the woods southeast of Assenois. Here the grenadiers encountered the 51st. Each German attempt to break into the open was stopped with heavy losses. General Hoecker says the lead battalion was "cut to pieces" and that the attack by the 167th was brought to nought by the Jabos and the "tree smasher" shells crashing in from the American batteries. (Hoecker could not know that the 35th Division artillery was trying out the new POZIT fuze and that his division was providing the target for one of the most [626] lethal of World War II weapons.) The main body of the 1st SS Panzer kampfgruppe appeared an hour or so before noon moving along the Lutremange-Lutrebois road; some twenty-five tanks were counted in all. It took two hours to bring the fighter-bombers into the fray, but they arrived just in time to cripple or destroy seven tanks and turn back the bulk of the panzers. Companies I and K still were in their foxholes along the road during the air bombing and would recall that, lacking bazookas, the green soldiers "popped off" at the tanks with their rifles and that some of the German tanks turned aside into the woods. Later the two companies came back across the valley, on orders, and jointed the defense line forming near the château. Thirteen German tanks, which may have. debouched from the road before the air attack, reached the woods southwest of Lutrebois, but a 4th Armored artillery observer in a cub plane spotted them and dropped a message to Company B of the 35th Tank Battalion. Lt. John A. Kingsley, the company commander, who had six Sherman tanks and a platoon from the 701st Tank Destroyer Battalion, formed an ambush near a slight ridge that provided his own tanks with hull defilade and waited. The leading German company (or platoon), which had six panzers, happened to see Company A of the 35th as the fog briefly lifted, and turned, with flank exposed, in that direction. The first shot from Kingsley's covert put away the German commander's tank and the other tanks milled about until all had been knocked out. Six more German tanks came along and all were destroyed or disabled. In the meantime the American tank destroyers took on some accompanying assault guns, shot up three of them, and dispersed the neighboring grenadiers. At the close of day the enemy had taken Lutrebois and Villers-la-Bonne-Eau plus the bag of three American rifle companies, but the eastern counterattack, like that in the west, had failed. Any future attempts to break through to Assenois and Hompré in this sector would face an alert and coordinated American defense. The III Corps Joins the Attack Despite the events of the 30th there was no thought in the mind of General Patton that Millikin's III Corps-would give over its attack toward St. Vith, scheduled to flesh out the Third Army offensive begun by Middleton. General Millikin would nonetheless have to alter his plans somewhat. It had been intended that the 6th Armored Division, coming in from the XII Corps, would pass through the 4th Armored (which now had only forty-two operable tanks) and set off the attack on 31 December with a drive northeast from the Bastogne perimeter. The 35th Division was to parallel this drive by advancing in the center on a northeast axis, while the 26th Division, on the corps' right wing, would turn its attack in a northwesterly direction. The 4th Armored expected to pass to Middleton's corps, but the latter agreed on the night of the 30th that Gaffey's command should continue its support of the 35th Division. Whether the 35th could shake itself free and take the offensive was questionable, but General Baade had orders to try. The 26th Division was now deployed in its entirety on the north side of the Sure [627] River and its center regiment was almost in sight of the highway linking Wiltz and Bastogne (the next phase line). Both flanks of the division were uncovered, however, and German tanks were observed moving into the area on the 30th. One thing the III Corps commander sought to impress on his infantry divisions as H-hour loomed-they must keep out of time-consuming and indecisive village fights. This, after all, was an order which had echoed up and down the chain of command on both sides of the line, but neither German nor American commanders could alter the tactical necessities imposed by the Ardennes geography or prevent freezing troops from gravitating toward the shelter, no matter how miserable, promised by some wrecked crossroads hamlet. Admittedly the battle which had flared up on the left wing of the III Corps was serious, but General Millikin expected (or at least hoped) that the 6th Armored Division attack would improve the situation.15 While deployed on the Ettelbruck front with the XII Corps, General Grow's troops had not been closely engaged, and the division would enter the Bastogne fight with only a single tank less than prescribed by the T/O&E. Its orders to move west were given the division at 0230 on the 29th. Although the distance involved was not too great, the movement would be complicated by the necessity of using a road net already saturated in the support of two corps. The push planned for 31 December turned on the employment of two combat commands abreast and for this reason the march north to Bastogne was organized so that CCA, ordered to attack on the right, would use the Arlon-Bastogne highway while CCB, ticketed for the left wing, would pass through the VIII Corps zone by way of the Neufchâteau-Bastogne road. During the night of 30 December CCA (Col. John L. Hines, Jr.) rolled along the icy highway, where the 4th Armored had accorded running rights to the newcomers, and through the city; the advance guard, however, took the secondary road through Assenois because of the German threat to the main route. By daylight CCA was in forward assembly positions behind the 101st Airborne line southeast of Bastogne. CCB failed to make its appearance as scheduled. What had happened was a fouling of the military machine which is common in all large-scale operations and which may leave bitterness and recrimination long after the event. The 6th Armored commander believed he had cleared CCB's use of the Neufchâteau road with both the VIII Corps and the 11th Armored, but when Col. George Read moved out with his column he found the highway not only treacherously iced but encumbered with 11th Armored tanks and vehicles. What Read had encountered was the switch bringing the 11th Armored force from the west around to the right wing. The 11th Armored had not expected the 6th Armored column to appear before midnight of the 31st. An attempt to run the two columns abreast failed because the tanks were slipping all over the road. [628] CCB later reported that the 11th Armored blocked the highway for six hours, that is, until ten o'clock on the morning of the 31st. Finally General Grow ordered Read's force to branch off and go into assembly at Clochimont on the Assenois road. Colonel Hines intended to postpone the CCA attack until the running mate arrived. There was no cover where his troops were waiting, however, and as the morning wore on intense enemy fire began to take serious toll. He and Grow decided, therefore, to launch a limited objective attack in which the two CCA task forces would start from near the Bastogne-Bras road and thrust northeast. The armored task force, organized around the 69th Tank Battalion (Lt. Col. Chester E. Kennedy), had the task of capturing Neffe and clearing the enemy from the woods to the east; the infantry task force, basically the 44th Armored Infantry Battalion (Lt. Col. Charles E. Brown), was to move abreast of Kennedy, scour the woods south of Neffe, and seize the nose of high ground which overlooked Wardin on the northeast. The assault, begun shortly after noon, rolled through Neffe with little opposition. But snow squalls clouded the landscape, the fighter-bombers sent to blast targets in front of CCA could not get through the overcast, and the armored infantry made little progress. CCA's expectation that the 35th Division would come abreast on the right was dashed, for the 35th had its hands full. Just before dusk small enemy forces struck at Hines's exposed flanks, and CCA halted, leaving the artillery to maintain a protective barrage through the night. The role of the artillery would be of prime importance in all the fighting done by the 6th Armored in what now had come to be called "the Bastogne pocket." Not only the three organic battalions of the division, but an additional four battalions belonging to the 193d Field Artillery Group were moved into the pocket on the 31st, and the firing batteries were employed almost on the perimeter itself. A feature of the battle would be a counterbattery duel-quite uncommon at this stage of the Ardennes Campaign-for the I SS Panzer Corps had introduced an artillery corps, including some long-range 170-mm. batteries, and a Werfer brigade southeast of Bastogne. Now and later the American gunners would find it necessary to move quickly from one alternate position to another, none too easy a task, for the gun carriages froze fast and even to turn a piece required blow torches and pinch bars. On the morning of New Year's Day CCB finally was in place on the left of Hines's combat command. The immediate task in hand was to knife through the German supply routes, feeding into and across the Longvilly road, which; permitted north-south movement along the eastern face of the Bastogne pocket and were being used to build up the forces in the Lutrebois sector. CCA would attempt a further advance to clear the woods and ridges beyond Neffe. CCB, working in two task forces, aimed its attack on Bourcy and Arloncourt with an eye to the high ground dominating the German road net. The 6th Armored Division expected that troops of the 101st Airborne would extend the push on the left of CCB and drive the enemy out of the Bois Jacques north of Bizory, the latter the first objective for CCB's [629] tank force. The previous afternoon the VIII Corps commander had ordered General Taylor to use the reserve battalion of the 506th Parachute Infantry for this purpose, then had countermanded his order. Apparently General Grow and his division knew nothing of the change. Communication between divisions subordinate to two different corps always is difficult, but in this case, with an armored and an airborne division involved, the situation was even worse. At this time the only radio contact between Taylor and Grow was by relay through an army supply point several miles south of Bastogne, but the two generals did meet on 31 December and the day following. The morning of the attack, 1 January 1945, was dark with cloud banks and squalls as the 68th Tank Battalion (Lt. Col. Harold C. Davall) moved rapidly along the narrow road to Bizory. The 78th Grenadier Regiment, in this sector since the first days of the Bastogne siege, had erected its main line of resistance farther to the east and Bizory fell easily. At the same time Davall's force seized Hill 510, which earlier had caused the 101st Airborne so much trouble. About noon the Americans began to receive heavy fire, including high velocity shells, from around Mageret on their right flank. Although doing so involved a detour, the 68th wheeled to deal with Mageret, its tanks crashing into the village while the assault gun platoon engaged the enemy antitank guns firing from wood cover nearby. The grenadiers fought for Mageret and it was midafternoon before resistance collapsed. Then the 69th Tank Battalion from CCA, which was on call, took over the fight to drive east from Mageret while its sister battalion turned back for the planned thrust at Arloncourt. By this time the sun had come out, visibility was good, and the CCB tanks were making such rapid progress that the division artillery commander (Col. Lowell M. Riley) brought his three battalions right up on Davall's heels. Within an hour the 68th was fighting at Arloncourt, but here it had hit the main German position. Briefly the Americans held a piece of Arloncourt, withdrawing at dark when it became apparent that the 50th Armored Infantry Battalion (Lt. Col. Arnold R. Wall), fighting through the woods to the northwest, could not come abreast. As it turned out, the 50th was forced to fall back to the morning line of departure. It too had collided with the main enemy defenses and was hit by a German counterattack-abruptly checked when the 212th Field Artillery laid in 500 rounds in twenty minutes. 16 The brunt of the battle in the CCA zone was borne by the 44th Armored Infantry, continuing doggedly through the woods southeast of Neffe against determined and well entrenched German infantry. Whenever the assault came within fifty yards of the foxhole line, the grenadiers climbed out with rifle and machine gun to counterattack. Two or three times Brown's battalion was ejected from the woods, but at close of day the Americans were deployed perhaps halfway inside the forest. The 6th Armored had gotten no assistance from the 35th Division during the day, and it [630]

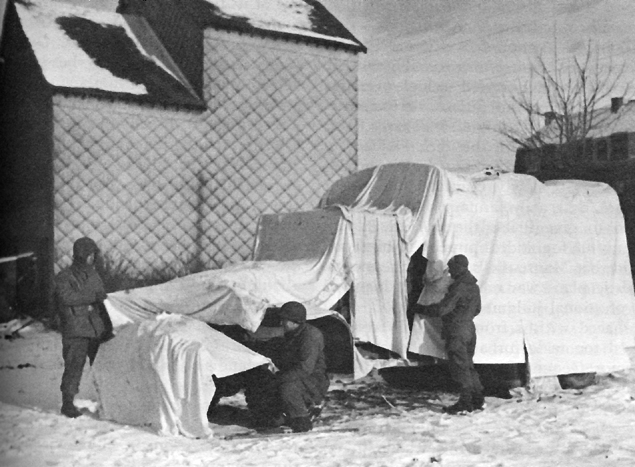

BED SHEETS DONATED BY VILLAGERS camouflage 6th Armored Division vehicles. was apparent to General Millikin that Grow's division would probably have to continue its attack alone. He therefore extended the 6th Armored front to the right so that on the evening of 1 January it reached from Bourcy on the north to Bras in the south. General Grow immediately brought his extra tank battalion and armored infantry battalion forward from CCR to beef up the combat commands on the line. Every tank, gun, and man would be needed. The new and wider front would bring the 167th Volks Grenadier Division into action against the 6th Armored south of Neffe. But this was not all. At the Fifth Panzer Army conference on the 29th one of the SS officers present was General Priess, commander of the I SS Panzer Corps. He was there because Manteuffel expected to re-create this corps, as it had existed in the first days of the offensive, by bringing the 12th SS Panzer Division in from the Sixth Panzer Army and joining to it the 1st SS Panzer Division, at the moment moving toward Lutrebois. The subsequent failure at Lutrebois was overshadowed by the American threat to the Panzer Lehr and Fuehrer Begleit west of Bastogne, and on the last day of December Manteuffel ordered Priess to take over in this sector, promising that the 12th SS Panzer shortly would arrive to flesh out the new I SS Panzer Corps. [631] On the afternoon of New Year's Day Priess had just finished briefing his three subordinate commanders for a counterattack to be started in the next few hours when a message arrived from Manteuffel: the 12th SS Panzer was detached from his command and Priess himself was to report to the army headquarters pronto. The two generals met about 1800. By this hour the full account of the 6th Armored attack was available and the threat to the weakened 26th Volks Grenadier Division could be assessed. Manteuffel ordered Priess to take over the fight in the 26th sector at noon on 2 January, and told him that his corps would be given the 12th SS Panzer, the 26th Volks Grenadier Division, and the 340th Volks Grenadier Division, which was en route from Aachen. The 6th Armored Division would be given some respite, however. When Field Marshal Model arrived to look over the plans for the counterattack, on the afternoon of the 2d, only a small tank force had come in from the 12th SS Panzer, and the main body of the 340th was progressing so slowly that Model set the attack date as 4 January. He promised also to give Priess the 9th SS Panzer Division for added punch. It must be said that Manteuffel's part in these optimistic plans was much against his own professional judgment. Faced with a front normally considered too wide for a linear advance by armor, General Grow put five task forces into the attack on 2 January, holding only one in reserve. The boundary between CCA and CCB was defined by the railroad line which once had linked Bastogne, Benonchamps, and Wiltz. CCB now had two tank battalions (the 68th and 69th) plus the 50th Armored Infantry Battalion to throw in on the north wing; CCA got the two fresh battalions from CCR. About one o'clock on the morning of the 2d the Luftwaffe began bombing the 6th Armored area. Although the German planes had been more conspicuous by their absence than their presence during the past days, it seemed that a few could always be gotten up as a token gesture when a large German ground attack was forming. (For example, on 30 December the Luftwaffe had supported the eastern and western attacks with great impartiality by dropping its bombs on Bastogne, the most concentrated air punishment the town received during the entire battle. CCB, 10th Armored, was bombed out of its headquarters, and a large portion of the Belgian population sought safety in flight.) While the German planes were droning overhead, dark shapes, increasing in number, were observed against the snow near Wardin. These were a battalion of the 167th Volks Grenadier forming for a counterattack Nine battalions of field artillery began TOT fire over Wardin, and the enemy force melted away. Just to the north, but in the CCB sector, the advance guard of the 340th Volks Grenadier Division made its initial appearance about 0200 on the 2d, penetrated the American outpost line, and broke into Mageret. The skirmish lasted for a couple of hours, but the Luftwaffe gave the defenders a hand by bombing its own German troops. In midmorning the 68th Tank Battalion sortied from Mageret to climb the road toward Arloncourt, the objective of the previous day. The paving was covered with ice and the slopes were too slippery and steep for the steel tank [632] treads; so the armored engineers went to work scattering straw on all the inclines. Finally, Company B came within sight of the village, but the Germans were ready-Nebelwerfers and assault guns gave the quietus to eight Shermans. The enemy guns were camouflaged with white paint and the snow capes worn by the gunners, and the supporting infantry blended discreetly with the landscape. So successful was the deception that when a company of Shermans and a company of light tanks hurried forward to assist Company B, they were taken under fire on an arc of 220 degrees. Colonel Davall radioed for a box barrage and smoke screen; Riley's gunners met the request in a matter of seconds and the 68th got out of the trap. Farther north, and advancing on a route almost at a right angle to that followed by the 68th, the 50th Armored Infantry Battalion pried a few grenadiers out of the cellars in Oubourcy and marched on to Michamps. The reception was quite different here. As Wall's infantry entered Michamps the enemy countered with machine gun bursts thickened by howitzer and Werfer fire coming in from the higher ground around Bourcy. This time twelve artillery battalions joined in to support the 50th. At sunset German tanks could be seen moving about in Bourcy and Colonel Wall, whose force was out alone on a limb, abandoned both Michamps and Oubourcy. (Wall himself was partially blinded by a Nebelwerfer shell and was evacuated.) The German tanks, two companies of the 12th SS Panzer which had just arrived from west of Bastogne, followed as far as Oubourcy. South of the rail line the 15th Tank Battalion (Lt. Col. Embrey D. Lagrew) came forward in the morning to pass through Brown's 44th Armored Infantry Battalion, but this march was a long one from Remichampagne and it was nearly noon before the 15th attack got under way. On the right the 9th Armored Infantry Battalion (Lt. Col. Frank K. Britton) came in to take over the fight the 44th had been waging in the woods near Wardin. It was planned that the armored infantry would sweep the enemy out of the wooded ridges which overlooked Wardin from the southwest and south, whereupon the tank force would storm the village from the north. Britton's battalion was caught in an artillery barrage during the passage of lines with Brown, became disorganized, and did not resume the advance until noon. Shortly thereafter the 9th was mistakenly brought under fire by the 134th Infantry. There was no radio communication between Lagrew and Britton, probably because of the broken terrain, and Lagrew reasoned that because of his own delay the infantry attack must have reached its objective. The tanks of the 15th Tank Battalion gathered in the woods northwest of Wardin, then struck for the village, but the German antitank guns on the surrounding ridges did some expert shooting and destroyed seven of Lagrew's tanks. Nonetheless a platoon from Company C of the 9th, attached to Lagrew's battalion, made its way into Wardin and remained there most of the night. All this while the 9th Armored Infantry Battalion was engaged in a heartbreaking series of assaults to breast the machine gun fire sweeping the barren banks of a small stream bed that separated the wood lot southwest of Wardin from another due south. This indecisive affair cost the 9th one-quarter [633]