CHAPTER V

On the night of 15 December German company commanders gave their men the watchword which had come from the Fuehrer himself: "Forward to and over the Meuse!" The objective was Antwerp. Hitler's concept of the Big Solution had prevailed; the enemy was not to be beaten east of the Meuse but encircled by a turning movement beyond that river. The main effort would be made by Dietrich's Sixth Panzer Army on the north wing, with orders to cross the Meuse on both sides of Liège, wheel north, and strike for the Albert Canal, fanning out the while to form a front extending from Maastricht to Antwerp. Meanwhile the infantry divisions to the rear of the armored columns would form the north shoulder of the initial advance and a subsequent blocking position east of the Meuse along the Vesdre River. Eventually, or so Hitler intended, the Fifteenth Army would advance to take a station protecting the Sixth Panzer Army right and rear.

Manteuffel's Fifth Panzer Army, initially acting as the center, had the mission of crossing the Meuse to the south of the Sixth, but because the river angled away to the southwest might be expected to cross a few hours later than its armored partner on the right. Once across the Meuse, Manteuffel had the mission of preventing an Allied counterattack against Dietrich's left and rear by holding the line Antwerp-Brussels-Namur-Dinant. The left wing of the counteroffensive, composed of infantry and mechanized divisions belonging to Brandenberger's Seventh Army, had orders to push to the Meuse, unwinding a cordon of infantry and artillery facing south and southwest, thereafter anchoring the southern German flank on the angle formed by the Semois and the Meuse. Also, the Fuehrer had expressed the wish that the first segment of the Seventh Army cordon be pushed as far south as Luxembourg City if possible.

What course operations were to take once Antwerp was captured is none too clear.1 Indeed no detailed plans existed for this phase. There are numerous indications that the field commanders did not view the Big Solution too seriously but fixed their eyes on the seizure of the Meuse bridgeheads rather than on the capture of Antwerp. Probably Hitler had good reason for the final admonition, on 15 December, that the attack was not to begin the northward wheel until the Meuse was crossed.

Dietrich's Sixth Panzer Army, selected to make the main effort, had a distinct political complexion. Its armored divisions all belonged to the Waffen SS, its

[75]

GENERAL DIETRICH

commander was an old party member, and when regular Wehrmacht officers were assigned to help in the attack preparations they were transferred to the SS rolls. Hitler's early plans speak of the Sixth SS Panzer Army, although on 16 December the army still did not bear the SS appellation in any official way, and it is clear that the Sixth was accorded the responsibility and honor of the main effort simply because Hitler felt he could depend on the SS.

Josef "Sepp" Dietrich had the appropriate political qualifications to ensure Hitler's trust but, on his military record, hardly those meriting command of the main striking force in the great counteroffensive. By profession a butcher, Dietrich had learned something of the soldier's trade in World War I, rising to the rank of sergeant, a rank which attached to him perpetually in the minds of the aristocratic members of the German General Staff. He had accompanied Hitler on the march to the Feldherrnhalle in l923 and by 1940 had risen to command the Adolf Hitler Division, raised from Hitler's bodyguard regiment, in the western campaign. After gaining considerable reputation in Russia, Dietrich was brought to the west in 1944 and there commanded a corps in the great tank battles at Caen. He managed to hang onto his reputation during the subsequent retreats and finally was selected personally by Hitler to command the Sixth Panzer Army. Uncouth, despised by most of the higher officer class, and with no great intelligence, Dietrich had a deserved reputation for bravery and was known as a tenacious and driving division and corps commander. Whether he could command an army remained to be proven. The attack front assigned the Sixth Panzer Army, Monschau to Krewinkel, was narrower than that of its southern partner because terrain in this sector was poor at the breakthrough points and would not offer cross-country tank going until the Hohes Venn was passed. The initial assault wave consisted of one armored and one infantry corps. On the south flank the I SS Panzer Corps (Generalleutnant der Waffen-SS Hermann Priess) had two armored divisions, the 1st SS Panzer and the 12th SS Panzer, plus three infantry divisions, the 3d Parachute, the 12th Volks Grenadier and the 277th Volks Grenadier. On the north flank the LXVII Corps (General der Infanterie Otto Hitzfeld) had only two infantry divisions, the 326th and 246th Volks Grenadier. The doctrinal question as to whether tanks or infantry should take the lead, still moot in German

[76]

military thinking after all the years of war, had been raised when Dietrich proposed to make the initial breakthrough with his two tank divisions. He was overruled by Model, however, and the three infantry divisions were given the mission of punching a hole on either side of Udenbreth. Thereafter the infantry was to swing aside, moving northwest to block the three roads which led south from Verviers and onto the route the armor would be taking in its dash for Liège. Hitzfeld's corps had a less ambitious program: to attack on either side of Monschau, get across the Mützenich-Elsenborn road, then turn north and west to establish a hard flank on the line Simmerath-Eupen-Limburg. All five of the Sixth Panzer Army infantry divisions ultimately would wind up, or so the plan read, forming a shoulder on an east-west line from Rotgen (north of Monschau) to Liège. Under this flank cover the armored divisions of the I SS Panzer Corps would roll west, followed by the second armored wave, the II SS Panzer Corps (General der Waffen-SS Willi Bittrich) composed of the 2d and 9th SS Panzer Divisions.

Dietrich's staff had selected five roads to carry the westward advance, the armor being assigned priority rights on the four southernmost. Actually it was expected that the 1st SS and 12th SS Panzer Divisions would use only one road each. (These two routes ran through the 99th Infantry Division sector.) Although the planning principle as regards the armored divisions was to hold the reins loose and let them run as far and as fast as they could, the Sixth Panzer did have a timetable: one day for penetration and breakout, one day to get the armor over the Hohes Venn, the Meuse to be reached by the evening of the third day, and crossings to be secured by the fourth.2

This army was relatively well equipped and trained. Most of its armor had been out of combat for some time and the horde of replacements had some degree of training in night movement and fighting. The 1st and 2d SS had not been loaded with Luftwaffe and over-age replacements as had the other divisions. The artillery complement of the Sixth Panzer Army was very heavy, albeit limited in mobility by the paucity of selfpropelled battalions. The four armored divisions had about 500 tanks and armored assault guns, including 90 Tigers (Mark VI). Lacking were two things which would markedly affect the operations of the Sixth Panzer Army once battle was joined. There were few trained engineer companies and these had little power equipment. The infantry lacked their full complement of assault guns, a weapon on which the German rifle platoon had learned to lean in the assault; only the 3d Parachute was fully armed with this critical infantry weapon.3

The southern portion of the V Corps front was occupied by the 99th Infantry Division (Maj. Gen. Walter E. Lauer),

[77]

which had arrived on the Continent in November 1944 and been placed in this defensive sector to acquire experience.4 The 99th Division front (left to right) extended from Monschau and Höfen to the railroad just north of Lanzerath, a distance of about nineteen miles. To the east lay the Germans in the West Wall pillbox line. The frontage assigned an untried division at first thought seems excessive, but the V Corps commander wished to free as much of his striking power as possible for use in the scheduled attack to seize the Roer dams; furthermore the nature of the terrain appeared little likely to attract a major German attack. (Map II)

In the extreme northern portion of the sector, around Höfen, the ground was studded with open hills, to the east of which lay a section of the Monschau Forest. Only a short distance to the south of Höfen the lines of the 99th entered this forest, continuing to run through a long timber belt until the boundary between the V and VII Corps was reached at the Losheim Gap. The thick woods in the sector were tangled with rock gorges, little streams, and sharp hills. The division supply lines began as fairly substantial all-weather roads, then dwindled, as they approached the forward positions, to muddy ruts following the firebreaks and logging trails. Except for the open area in the neighborhood of Höfen, visibility was limited and fields of fire restricted. Any clearing operation in the deep woods would only give away the American positions. Although terrain seemed equally difficult for offense or defense, this balance would exist only so long as the defender could retain control over his units in the woods and provide some sort of cordon to check infiltration. The nature of the ground and the length of the front made such a cordon impossible; the 99th could maintain no more than a series of strongpoints, with unoccupied and undefended gaps between.

Three roads were of primary importance in and east of the division area. In the north a main paved road led from Höfen through the Monschau Forest, then divided as it emerged on the eastern edge (this fork beyond the forest would have some tactical importance.) A second road ran laterally behind the division center and right wing, leaving the Höfen road at the tiny village of Wahlerscheid, continuing south through the twin hamlets of Rocherath and Krinkelt, then intersecting a main eastwest road at Büllingen. This paved highway entered the division zone from the east at Losheimergraben and ran west to Malmédy by way of Büllingen and Butgenbach. As a result, despite the poverty of roads inside the forest belt where the forward positions of the 99th Division lay, the division sector could be entered

[78]

SNOW SCENE NEAR KRINKELT

from the east along roads tapping either flank.

From 8 December on the 99th Division had been preparing for its first commitment in a large-scale operation, repairing roads, laying additional telephone wire, and shifting its guns for the V Corps attack toward the Roer dams. In addition a new supply road was constructed from the Krinkelt area to the sector held by the 395th Infantry. The 2d Infantry Division was to pass through the 99th, then the latter would attack to cover the southern flank of the 2d Division advance. As scheduled, the 2d Division passed through the 99th Division on 13 December, beginning its attack on a narrow front toward Dreiborn, located on the northern fork of the Höfen road beyond the Monschau Forest.

The dispositions of the 99th Division were these: On the north flank the 3d Battalion, 395th Infantry, occupied the Höfen area, with the 38th Cavalry Squadron on the left and the 99th Reconnaissance Troop on the right. The ground here was open and rolling, the 3d Battalion well dug in and possessed of good fields of fire. Next in line to the south, the 2d Division was making its attack on a thrust line running northeastward, its supply route following the section of the Höfen road which ran through the forest to the fork. The remaining two battalions of the 395th resumed the 99th Division front, succeeded

[79]

to the south, in turn, by the 393d Infantry and the 394th. Conforming to the wooded contour, the elements of the 99th Division south of the 2d Division attacking column occupied a slight salient bellying out from the flanks.

Two battalions of the 99th Division (the 1st and 2d of the 395th) took part in the attack begun on 13 December, although other elements of the division put on demonstrations to create some diversion to their immediate front. The 2d Battalion, 395th, on the right of the 2d Division jumped off in deep snow and bitter cold in an attack intended to swing north, wedge through the West Wall bunker line, and seize Harperscheid on the southern fork of the road beyond the forest. The advance on the 13th went well; then, as the attack hit the German bunkers and enemy guns and mortars ranged in, the pace began to slow. By 16 December, however, several important positions were in American hands and it seemed that a breakthrough was in the making despite bad weather, poor visibility, and difficult terrain.

The German troops manning the West Wall positions in front of the 2d and 99th Divisions had been identified prior to the 13 December attack as coming from the 277th Volks Grenadier Division and the 294th Regiment of the 18th Volks Grenadier Division. An additional unit was identified on the second day of the offensive when prisoners were taken who carried the pay books of the 326th Volks Grenadier Division. Although this was the only indication of any German reinforcement, American commanders and intelligence officers anticipated that a counterattack shortly would be made against the shoulders of the 2d Division corridor held by the 99th, but that this would be limited in nature and probably no more than regimental in strength. The immediate and natural reaction, therefore, to the German attack launched against the 99th Division on the morning of the fourth day of the V Corps offensive (16 December) was that this was no more than the anticipated riposte.

The Initial Attack

16 December

To the south of the 393d Infantry, the 394th (Col. Don Riley) held a defensive sector marking the right flank terminus for both the 99th Division and V Corps. The 6,500-yard front ran along the International Highway from a point west of Neuhof, in enemy hands, south to Losheimergraben. Nearly the entire line lay inside the forest belt. On the right a two-mile gap existed between the regiment and the forward locations of the 14th Cavalry Group. To patrol this gap the regimental I and R Platoon held an outpost on the high ground slightly northwest of Lanzerath and overlooking the road from that village. Thence hourly jeep patrols worked across the gap to meet patrols dispatched by the cavalry on the other side of the corps boundary. Acutely aware of the sensitive nature of this southern flank, General Lauer had stationed his division reserve (3d Battalion of the 394th) near the Buchholz railroad station in echelon behind the right of the two battalions in the line. The fateful position of the 394th would bring against it the main effort of the I SS Panzer Corps and, indeed, that of the Sixth Panzer Army. Two roads ran obliquely through the regimental area. One, a main road, intersected the north-south International Highway (and the

[80]

forward line held by the 394th) at Losheimergraben and continued northwestward through Büllingen and Butgenbach to Malmédy. The other, a secondary road but generally passable in winter, branched from the International Highway north of Lanzerath, and curved west through Buchholz, Honsfeld, Schoppen, and Faymonville, roughly paralleling the main road to the north.

Of the five westward roads assigned the I SS Panzer Corps the two above were most important. The main road to Büllingen and Malmédy would be called "C" on the German maps; the secondary road would be named "D." These two roads had been selected as routes for the main armored columns, first for the panzer elements of the I SS Panzer Corps, then to carry the tank groups of the II SS Panzer Corps composing the second wave of the Sixth Panzer Army's attack. But since the commitment of armored spearheads during the battle to break through the American main line of resistance had been ruled out, the initial German attempt to effect a penetration would turn on the efforts of the three infantry divisions loaned the I SS Panzer Corps for this purpose only. The 277th Volks Grenadier Division, aligned opposite the American 393d Infantry, had a mission which would turn its attack north of the axis selected for the armored advance. Nonetheless, success or failure by the 277th would determine the extent to which the tank routes might be menaced by American intervention from the north. The twin towns, Rocherath-Krinkelt, for example, commanded the road which cut across-and thus could be used to block-the Büllingen road, route C.

The two infantry divisions composing the I SS Panzer Corps center and south wing were directly charged with opening the chief armored routes. The 12th Volks Grenadier Division, regarded by the Sixth Army staff as the best of the infantry divisions, had as its axis of attack the Büllingen road (route C); its immediate objective was the crossroads point of departure for the westward highway at Losheimergraben and the opening beyond the thick Gerolstein Forest section of the woods belt. The ultimate objective for the 12th Division attack was the attainment of a line at Nidrum and Weywertz, eight airline miles beyond the American front, at which point the division was to face north as part of the infantry cordon covering the Sixth Panzer Army flank. The 3d Parachute Division, forming the left wing in the initial disposition for the attack, had a zone of advance roughly following the southern shoulder of the Honsfeld or D route. The area selected for the breakthrough attempt comprised the north half of the U.S. 14th Cavalry Group sector and took in most of the gap between the cavalry and the 99th Division. In the first hours of the advance, then, the 3d Parachute Division would be striking against the 14th Cavalry Group in the Krewinkel-Berterath area. But the final objective of the 3d Parachute attack was ten miles to the northwest, the line Schoppen-Eibertingen on route D. The 3d Parachute axis thus extended through the right of the 99th Division.

The decision as to exactly when the two panzer divisions would be committed in exploitation of the penetrations achieved by the infantry was a matter to be decided by the commanders of the Sixth Panzer Army and Army

[81]

Group B as the attack developed. Armored infantry kampfgruppen from the 12th SS Panzer Division and 1st SS Panzer Division were assembled close behind the infantry divisions, in part as reinforcements for the breakthrough forces, in part because none of the Volks Grenadier units were used to close cooperation with armor.

Considerable reshuffling had been needed in the nights prior to 16 December to bring the I SS Panzer Corps toward its line of departure and to feed the infantry into the West Wall positions formerly occupied by the 277th Division. All this was completed by 0400 on the morning set for the attack (except for the reconnaissance battalion which failed to arrive in the 3d Parachute Division lines), and the bulk of the two artillery corps and two Volks Werfer brigades furnishing the artillery reinforcement was in position. None of the three army assault gun battalions, one for each attacking division, had yet appeared. The German artillery, from the 75-mm. infantry accompanying howitzers up to the 210-mm. heavy battalions, were deployed in three groupments, by weight and range, charged respectively with direct support of the attacking infantry, counterbattery, and long-distance fire for destruction.

The first thunderclap of the massed German guns and Werfers at 0530 on 16 December was heard by outposts of the 394th Infantry as "outgoing mail," fire from friendly guns, but in a matter of minutes the entire regimental area was aware that something most unusual had occurred. Intelligence reports had located only two horse-drawn artillery pieces opposite one of the American line battalions; after a bombardment of an hour and five minutes the battalion executive officer reported, "They sure worked those horses to death." But until the German infantry were actually sighted moving through the trees, the American reaction to the searchlights and exploding shells was that the enemy simply was feinting in answer to the 2d and 99th attack up north. In common with the rest of the 99th the line troops of the 394th had profited by the earlier quiet on this front to improve their positions by log roofing; so casualties during the early morning barrage were few.

The German infantry delayed in following up the artillery preparation, which ended about 0700. On this part of the forest front the enemy line of departure was inside the woods. The problem, then, was to get the attack rolling through the undergrowth, American barbed wire, and mine fields immediately to the German front. The groping nature of the attack was enhanced by the heavy mist hanging low in the forest.

The 2d Battalion, on the north flank, was more directly exposed since a road led into the woods position from Neuhof. At this point, close to the regimental boundary, the battle was carried by a fusilier company attached to the 990th Regiment of the 277th Volks Grenadier Division. The fusiliers succeeded in reaching the 2d Battalion lines about 0800 but were driven off by small arms fire and artillery.

In midafternoon the 12th SS Panzer Division, waiting for the infantry to open the road to the International Highway, apparently loaned a few tanks to carry the fusiliers into the attack.5 Behind

[82]

a smoke screen the tanks rolled out of Neuhof. An American sergeant spotted this move and with a sound-powered telephone brought friendly artillery into play. High explosive stopped the tanks in their tracks. A few infantry-men got through to the forest positions occupied by the 2d Battalion. There an unknown BAR man atop a log hut "raised hell with the Krauts" and the attack petered out. The 2d Battalion, during this day, never was really pressed. The chief enemy thrusts had gone to the north, where the right flank of the 393d Infantry was hit hard by the 277th Division, and to the south, against the center and refused right flank of the 394th. No word of events elsewhere on the 394th front reached the 2d Battalion command post, but the appearance of German infantry in the woods along the northern regimental boundary gave a clue to the penetration developing there, and the left company of the 2d Battalion was pulled back somewhat as flank protection.

The initial enemy action along the 394th Infantry center and south flank was intended to punch holes through which the panzer columns might debouch onto the Büllingen and Honsfeld roads. The prominent terrain feature, in the first hours of the fight, was a branch railroad line which crossed the frontier just north of Losheim and then twined back and forth, over and under the Büllingen-Malmédy highway westward. During the autumn retreat the Germans themselves had destroyed the bridge which carried the Büllingen road over the railroad tracks north of Losheim. To the west the highway overpass on the Lanzerath-Losheimergraben section of the International Highway had also been demolished. The crossroads at Losheimergraben would have to be taken if the German tanks were to have quick and easy access to the Büllingen road, but the approach to Losheimergraben, whether from Losheim or Lanzerath, was denied to all but infantry until such time as the railroad track could be captured and the highway overpasses restored.

The line of track also indicated the axis for the advance of the left wing of the 12th Volks Grenadier Division and, across the lines, marked a general boundary between the 1st and 3d Battalions of the 394th Infantry. When the barrage lifted, about 0700, the assault regiments of the 12th Division already were moving toward the American positions. The 48th Grenadier Regiment, in the north, headed through the woods for the Losheimergraben crossroads. Fallen trees, barbed wire, and mines, compounded with an almost complete ignorance of the forest trails, slowed this advance. The attack on the left, by the 27th Fuesilier Regiment, had easier going, with much open country and a series of draws leading directly to the track and the American positions.

The 3d Battalion (Maj. Norman A. Moore), to the south and west of the 1st Battalion position at Losheimergraben,

[83]

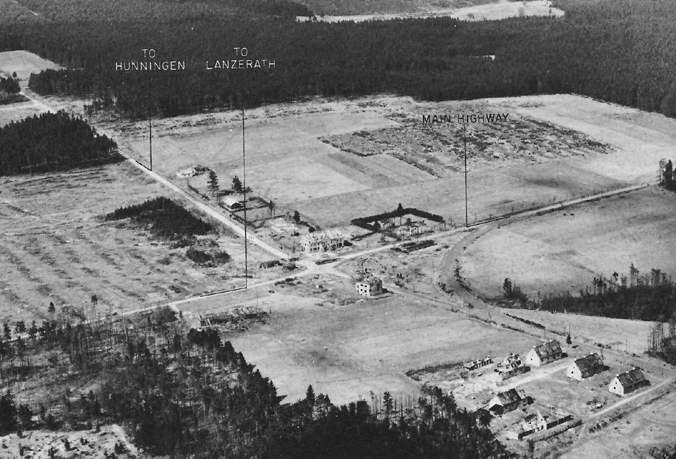

LOSHEIMERGRABEN

first encountered the enemy. About 0745 L Company, at the Buchholz station, had taken advantage of the lull in the shelling and was just lining up for breakfast when figures were seen approaching through the fog, marching along the track in a column of two's. First thought to be friendly troops, the Germans were almost at the station before recognition brought on a fusillade of American bullets. The enemy scattered for the boxcars outside the station or sought shelter in ditches along the right of way and a close-quarters fire fight began. A 3-inch tank destroyer systematically worked over the cars, while the American mortar crews raked the area beside the track. A few Germans reached the roundhouse near the station, but Sgt. Savino Travalini, leader of the antitank platoon, went forward with a bazooka, fired in enough rounds to flush the fusiliers, then cut them down with his rifle as they broke into the open. (Sergeant Travalini was awarded a battlefield commission as second lieutenant.) K Company, ordered up to reinforce the outnumbered defenders at the station, arrived in time to take a hand in the affray. By noon the Germans had been repelled, leaving behind about seventy-five dead; L Company had suffered twenty-five or thirty casualties.

As a result of the stubborn stand at the station, some of the assault platoons.

[84]

of the 27th Fuesilier Regiment circled back to the northeast and onto the left of the 1st Battalion (Lt Col. Robert H. Douglas). Here one of the battalion antitank guns stopped the lead German tank and the supporting fusiliers were driven back by 81-mm. mortar fire thickened by an artillery barrage. The major threat in the Losheimergraben sector came shortly after noon when the 48th Grenadier Regiment finally completed its tortuous approach through the woods, mines, and wire, and struck between B and C Companies. B Company lost some sixty men and was forced back about 400 yards; then, with the help of the attached heavy machine gun platoon, it stiffened and held. During the fight Sgt. Eddie Dolenc moved his machine gun forward to a shell hole which gave a better field of fire. When last seen Sergeant Dolenc still was firing, a heap of gray-coated bodies lying in front of the shell hole.6 The C Company outposts were driven in, but two platoons held their original positions throughout the day. Company A beat off the German infantry assault when this struck its forward platoon; then the battalion mortar platoon, raising its tubes to an 89-degree angle, rained shells on the assault group, leaving some eighty grenadiers dead or wounded.

The early morning attack against the right flank of the 394th had given alarming indication that the very tenuous connection with the 14th Cavalry Group had been severed and that the southern flank of the 99th Division was exposed to some depth. The only connecting link, the 30-man I and R Platoon of the 394th, northwest of Lanzerath, had lost physical contact early in the day both with the cavalry and with its own regiment. Radio communication with the isolated platoon continued for some time, and at 1140 word was relayed to the 99th Division command post that the cavalry was pulling out of Lanzerath-confirmation, if such were needed, of the German break-through on the right of the 99th. Belatedly, the 106th Infantry Division reported at 1315 that it could no longer maintain contact at the interdivision boundary. Less than an hour later the radio connection with the I and R Platoon failed. By this time observers had seen strong German forces pouring west through the Lanzerath area. (These were from the 3d Parachute Division.) General Lauer's plans for using the 3d Battalion, 394th Infantry, as a counterattack force were no longer feasible. The 3d Battalion, itself under attack, could not be committed elsewhere as a unit and reverted to its parent regiment. Not long after the final report from the I and R Platoon, the 3d Battalion was faced to the southwest in positions along the railroad.

A check made after dark showed a discouraging situation in the 394th sector. It was true that the 2d Battalion, in the north, had not been much affected by the day's events-but German troops were moving deeper on the left and right of the battalion. In the Losheimergraben area the 1st Battalion had re-formed in a thin and precarious line; the crossroads still were denied the enemy. But B Company had only twenty men available for combat, while the enemy settled down in the deserted American foxholes only a matter of yards away. Four platoons had been taken from the 3d Battalion to reinforce the 1st, leaving the former with no more than a hundred

[85]

men along the railroad line. Farther to the west, however, about 125 men of the 3d Battalion who had been on leave at the rest center in Honsfeld formed a provisional unit extending somewhat the precarious 394th flank position.

Some help was on the way. General Lauer had asked the 2d Division for a rifle battalion to man a position which the 99th had prepared before the attack as a division backstop between Mürringen and Hünningen. At 1600 Colonel Riley was told that the 394th would be reinforced by the 1st Battalion, 23d Infantry, of the 2d Division. During the night this fresh rifle battalion, and a company each of tanks and tank destroyers, under the command of Lt. Col. John M. Hightower, moved from Elsenborn to take up positions south and southeast of Hünningen. Before sunrise, 17 December, these reinforcements were in place.

During the night of 16-17 December the entire infantry reserve in the 99th Division zone had been committed in the line or close behind it, this backup consisting of the local reserves of the 99th and the entire 23d Infantry, which had been left at Elsenborn while its sister regiments took part in the 2d Division attack to break out in the Wahlerscheid sector. The 3d Battalion of the 23d had set up a defensive position on a ridge northeast of Rocherath, prepared to support the 393d Infantry. The 2d Battalion had assembled in the late afternoon of the 16th approximately a mile and a quarter north of Rocherath. The 1st Battalion would be at Hünningen. Troops of the 2d Division had continued the attack on 16 December, but during the afternoon Maj. Gen. Walter M. Robertson made plans for a withdrawal, if necessary, from the Wahlerscheid sector.

As early as 1100 word of the German attacks on the V Corps front had produced results at the command post of the northern neighbor, the VII Corps. The 26th Infantry of the uncommitted 1st Infantry Division, then placed on a 6-hour alert, finally entrucked at midnight and started the move south to Camp Elsenborn. The transfer of this regimental combat team to the V Corps would have a most important effect on the ensuing American defense.

The First Attacks in the Monschau-Höfen Sector Are Repulsed

16 December

The village of Höfen, the anchor point for the northern flank of the 99th Division, had considerable importance in the attack plans of the German Sixth Panzer Army. Located on high ground, Höfen overlooked the road center at Monschau, just to the north, and thus barred entry to the road to Eupen-at the moment the headquarters of the V Corps.

For some reason Field Marshal Model wished to save the German town of Monschau from destruction and had forbidden the use of artillery there.7 The plan handed General Hitzfeld for the employment of his LXVII Corps (Corps Monschau) called for an attack to the north and south of Monschau that was intended to put two divisions astride the Monschau-Eupen road in position to check any American reinforcements attempting a move to the south. The right division of the Corps Monschau, the

[86]

326th Volks Grenadier Division, had been ordered to put all three regiments in the initial attack: one to swing north of Monschau and seize the village of Mützenich on the Eupen road; one to crack the American line south of Monschau, then drive northwest to the high ground on the road just beyond Mützenich; the third to join the 246th Volks Grenadier Division drive through Höfen and Kalterherberg, the latter astride the main road from Monschau south to Butgenbach. If all went according to plan, the 326th and 246th would continue northwestward along the Eupen road until they reached the Vesdre River at the outskirts of Eupen.8 The force available to Hitzfeld on the morning of 16 December for use in the Monschau-Höfen sector was considerably weaker than the 2-division attack planned by the Sixth Panzer Army. In the two nights before the attack the 326th Volks Grenadier Division had moved into the West Wall fortifications facing Monschau and Höfen. The American attack against the 277th Volks Grenadier Division at Kesternich, however, siphoned off one battalion to reinforce the latter division; in addition one battalion failed to arrive in line by the morning of 16 December. Worse, the 246th Volks Grenadier Division, supposed to come south from the Jülich sector, had been held there by American attacks. Hitzfeld was thus left with only a few indifferent fortress troops on the south flank of the 326th Division. The total assault strength in the Höfen-Monschau area, as a result, was between three and four battalions. Nonetheless, Hitzfeld and the 326th commander Generalmajor Erwin Kaschner, could count on a heavy weight of artillery fire to give momentum to the attack. Two artillery corps (possibly totaling ten battalions) were in position to give fire either north or south of the no-fire zone at Monschau, plus one or two Volks Werfer brigades-a considerable groupment for the support of a division attack at this stage of the war.

The American strength in the Höfen-Monschau sector consisted of one rifle battalion and a reconnaissance squadron: the 3d Battalion, 395th Infantry, under Lt. Col. McClernand Butler, in Höfen, and the 38th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron (Lt. Col. Robert E. O'Brien) outposting Monschau and deployed to the north along the railroad track between Mützenich and Konzen station. The infantry at Höfen lay in a foxhole line along a thousand-yard front on the eastern side of the village, backed up by dug-out support positions on which the battalion had labored for some six weeks. Two nights prior to the German offensive, Company A of the 612th Tank Destroyer Battalion towed its 3-inch guns into the Höfen sector for the purpose of getting good firing positions against the village of Rohren, northeast of Höfen, which lay in the path of the 2d Infantry Division attack. The appearance of the guns, sited well forward and swathed in sheets for protective coloration in the falling snow, gave a lift to the infantry, who as yet had to fight their first battle.

[87]

CONSTRUCTING A WINTERIZED SQUAD HUT NEAR THE FRONT LINES

the 196th Field Artillery Battalion were emplaced to give the battalion direct support.

The 38th Cavalry Squadron was aligned from Monschau north to Konzen station, holding a continuous position with fifty dismounted machine guns dug in behind mines, barbed wire, and trip flares covering the approaches from the east. The right flank of the squadron, outposting Monschau, was at some disadvantage because of the deep, rocky draws leading into and past the town. But to the north the terrain was less cut up and offered good fields of fire for the American weapons posted on the slopes west of the railroad track. In addition to the assault gun troop in Mützenich, the squadron was reinforced by a platoon of selfpropelled tank destroyers from the 893d Tank Destroyer Battalion, which was stationed behind the left flank to cover a secondary road which entered the American position, and the 62d Armored Field Artillery Battalion. On the whole the defense in the Monschau-Höfen area was well set when the battalions of the 326th Volks Grenadier Division moved forward to their attack positions on the morning of 16 December. The German guns and Werfers

[88]

opened a very heavy barrage at 0525, rolling over the forward lines, then back to the west along the Eupen road, shelling the American artillery positions and cutting telephone wires. Neither the infantry nor cavalry (gone well to ground) suffered much from this fire, heavy though it was; but many buildings were set afire in Höfen and some were beaten to the ground. Monschau, as directed by Model, escaped this artillery pounding. In twenty minutes or so the German fire died away and off to the east the glow of searchlights rose as artificial moonlight. About 0600 the German grenadiers came walking out of the haze in front of the 3d Battalion. The wire to the American guns was out and during the initial onslaught even radio failed to reach the gunners. The riflemen and tank destroyer gunners, however, had the German infantry in their sights, without cover and at a murderously easy range.

The result was fantastic. Yet the grenadiers who lived long enough came right up to the firing line-in three verified instances the bodies of Germans shot at close range toppled into the foxholes from which the bullets came. A few got through and into the village. Assault companies of the 1st Battalion, 751st Regiment, and the 1st Battalion, 753d Regiment, had made this attack. But the support companies of the two battalions were blocked out by an intense concentration of well-aimed 81-mm. mortar fire from the American heavy weapons company, this curtain strengthened within an hour by the supporting howitzer battalion. By 0745 the attack was finished, and in another hour some thirty or forty Germans who had reached the nearest houses were rounded up. Reports of the German dead "counted" in front of Höfen vary from seventy-five to two hundred. The casualties suffered by the 3d Battalion in this first action were extraordinarily light: four killed, seven wounded, and four missing.

At Monschau the 1st Battalion of the 752d Regiment carried the attack, apparently aimed at cutting between the Monschau and Höfen defenses. As the German shellfire lessened, about 0600, the cavalry outposts heard troops moving along the Rohren road which entered Monschau from the southeast. The grenadiers were allowed to approach the barbed wire at the roadblock, then illuminating mortar shell was fired over the Germans and the cavalry opened up with every weapon at hand-the light tanks doing heavy damage with 37-mm. canister. Beaten back in this first assault, the German battalion tried again at daylight, this time attempting to filter into town along a draw a little farther to the north. This move was checked quickly. No further attack was essayed at Monschau and a half-hearted attempt at Höfen, toward noon, was handily repelled. As it was, the 326th Volks Grenadier Division lost one-fifth of the troops put into these attacks.

To the south of Höfen and Monschau in the 2d Division and 395th Infantry zones, 16 December passed with the initiative still in American hands. The German attacks delivered north and south of the corridor through which the Americans were pushing had no immediate repercussion, not even in the 395th Infantry sector. The Sixth Panzer Army drive to make a penetration between Hollerath and Krewinkel with the 1st SS Panzer Corps, therefore, had no contact with the Monschau Corps in the

[89]

north, nor was such contact intended in the early stages of the move west. The German command would pay scant attention to the small American salient projecting between the LX VII Corps and the 1st SS Panzer Corps, counting on the hard-pressed 272d Volks Grenadier Division to hold in the Wahlerscheid-Simmerath sector so long as needed.

The German Effort Continues

17-18 December

Although hard hit and in serious trouble at the end of the first day, particularly on the right flank as General Lauer saw it, the inexperienced 99th Division had acquitted itself in a manner calculated to win the reluctant admiration of the enemy. German losses had been high. Where the American lines had been penetrated, in the 393d and 394th sectors, the defenders simply had been overwhelmed by superior numbers of the enemy who had been able to work close in through the dense woods. Most important of all, the stanch defense of Losheimergraben had denied the waiting tank columns of the I SS Panzer Corps direct and easy entrance to the main Büllingen-Malmédy road.

The initial German failure to wedge an opening for armor through the 99th, for failure it must be reckoned, was very nearly balanced by the clear breakthrough achieved in the 14th Cavalry Group sector. The 3d Parachute Division, carrying the left wing of the I SS Panzer Corps forward, had followed the retreating cavalry through Manderfeld, swung north, and by dusk had troops in Lanzerath-only two kilometers from the 3d Battalion, 394th, position at Buchholz.

The 12th SS Panzer Division could not yet reach the Büllingen road. The 1st SS Panzer Division stood ready and waiting to exploit the opening made by the 3d Parachute Division by an advance via Lanzerath onto the Honsfeld road. During the early evening the advance kampfgruppe of the 1st SS Panzer Division, a task force built around the 1st SS Panzer Regiment (Obersturmbannfuehrer Joachim Peiper), rolled northwest to Lanzerath. At midnight-an exceptionally dark night-German tanks and infantry struck suddenly at Buchholz. The two platoons of Company K, left there when the 3d Battalion stripped its lines to reinforce the Losheimergraben defenders, were engulfed. One man, the company radio operator, escaped. Hidden in the cellar of the old battalion command post near the railroad station, he reported the German search on the floor above, then the presence of tanks outside the building with swastikas painted on their sides. His almost hourly reports, relayed through the 1st Battalion, kept the division headquarters informed of the German movements. About 0500 on 17 December the main German column began its march through Buchholz. Still at his post, the radio operator counted thirty tanks, twenty-eight half-tracks filled with German infantry, and long columns of foot troops marching by the roadside. All of the armored task force of the 1st SS Panzer Division and a considerable part of the 3d Parachute Division were moving toward Honsfeld.

Honsfeld, well in the rear area of the 99th, was occupied by a variety of troops. The provisional unit raised at the division rest camp seems to have been deployed around the town. Two platoons

[90]

of the 801st Tank Destroyer Battalion had been sent in by General Lauer to hold the road, and during the night a few towed guns from the 612th Tank Destroyer Battalion were added to the defenses. Honsfeld was in the V Corps antiaircraft defense belt and two battalions of 90-mm. antiaircraft guns had been sited thereabout. In addition, Troop A, 32d Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron, had arrived in Honsfeld late in the evening.

The stream of American traffic moving into the village during the night probably explains the ease with which the Honsfeld garrison was routed. The leading German tanks simply joined this traffic, and, calmly led by a man signaling with a flashlight, rolled down the village streets. With German troops pouring in from all sides the Americans offered no concrete resistance. Though some made a fight of it, most engaged in a wild scramble to get out of town. Some of the tank destroyers were overrun by infantry attack through the dark. Guns and vehicles, jammed on the exit roads, were abandoned; but many of the Americans, minus their equipment, escaped.

The predawn seizure of Honsfeld opened D route to the spearhead column of the 1st SS Panzer Division. Reconnaissance, however, showed that the next section of this route, between Honsfeld and Schoppen, was in very poor condition. Since the 12th SS Panzer Division had not yet reached C route, the main Büllingen-Malmédy road, Peiper's kampfgruppe now turned north in the direction of Büllingen with the intention of continuing the westward drive on pavement. At 0100 on 17 December the 24th Engineer Battalion had been attached to the 99th Division and ordered to Büllingen, there to prepare positions covering the entrances from the south and southeast. Twice during the dark hours the engineers beat back German infantry attacks; then, a little after 0700, enemy tanks hove into sight. Falling back to the shelter of the buildings, the 254th did what it could to fend off the tanks. Here, in the town, a reconnaissance platoon of the 644th Tank Destroyer Battalion had just arrived with orders to establish contact with the enemy column, but only one section managed to evade the panzers. The rest of the platoon were killed or captured. Upon receipt of orders from the division, the engineers, who had clung stubbornly to houses in the west edge, withdrew and dug in on higher ground 1,000 yards to the northwest so as to block the road to Butgenbach. There the two companies of the 254th still intact were joined by men hastily assembled from the 99th Division headquarters, the antiaircraft artillery units in the vicinity, and four guns from the 612th Tank Destroyer Battalion.

To the surprise of the Americans gathered along this last thin line the Germans did not pursue the attack. By 1030 a long line of tanks and vehicles were seen streaming through Büllingen, but they were moving toward the southwest! Later, the 99th Division commander would comment that "the enemy had the key to success within his hands, but did not know it." And so it must have seemed to the Americans on 17 December when a sharp northward thrust from Büllingen would have met little opposition and probably would have entrapped both the 99th and 2d Divisions.

[91]

In fact, Peiper's column had simply made a detour north through Büllingen and, having avoided a bad stretch of road, now circled back to its prescribed route.

American ground observers, on the 17th, attributed the change in direction to intervention by friendly fighter-bombers, whose attack, so it appeared, "diverted" the German column to the southwest. Two squadrons of the 366th Fighter Group, called into the area to aid the 99th Division, made two attacks during the morning. The 389th Squadron struck one section of the German column, which promptly scattered into nearby woods, and claimed a kill of thirty tanks and motor vehicles. It is doubtful that the Germans were crippled to any such extent-certainly the move west was little delayed-but the American troops must have been greatly heartened. The 390th Squadron, directed onto the column now estimated to be two hundred vehicles or more, was intercepted by a squadron of ME-109's which dropped out of the clouds over Büllingen. The Americans accounted for seven German aircraft, but had to jettison most of their bombs.

The lack of highway bridges over the railroad south of Losheimergraben had turned the first day's battle for the Losheimergraben crossroads into an infantry fight in the surrounding woods. Both sides had sustained heavy losses. The 48th Grenadier Regiment had pushed the 1st Battalion of the 394th back, but had failed to break through to the tiny collection of customs buildings and houses at the crossroads. By daylight on 17 December the Americans held a fairly continuous but thinly manned front with the 1st Battalion around Losheimergraben, part of the 3d Battalion west of the village, and the 1st Battalion of the 23d Infantry holding the exposed right-flank position in Hünningen.

The 12th Volks Grenadier Division, under pressure from higher headquarters to take Losheimergraben, continued the attack with both its forward regiments, now considerably weakened. While the 27th Fuesilier Regiment moved to flank Losheimergraben on the west, the 48th Grenadier Regiment continued its costly frontal attack. The flanking attack was successful: at least a battalion of the 27th drove through a gap between the 1st and 3d Battalions. By 1100 the German infantry were able to bring the Losheim-Büllingen road under small arms fire and the noose was tightening on the Losheimergraben defenders. The frontal attack, at the latter point, was resumed before dawn by enemy patrols trying to find a way around the American firing line in the woods.

In a foxhole line 200 yards southeast of Losheimergraben, 1st Lt. Dewey Plankers had organized about fifty men. This small force-men from Companies B and C, jeep drivers, and the crew of a defunct antiaircraft gun-beat back all of the German patrols. But the game was nearly up. The enemy Pioneers finally threw a bridge over the railroad at the demolished overpass on the Losheim road, and at about 1100 three panzers, supported by a rifle company, appeared in the woods in front of Plankers' position. Lacking ammunition and weapons (twenty of the tiny force were armed

[92]

only with pistols), Plankers ordered his men back to the customs buildings at the crossroads and radioed for help. Carbines, rifles, and ammunition, loaded on the only available jeep (the chaplain's), were delivered under fire to the American "blockhouses." The German tankers, unwilling to chance bazooka fire at close range, held aloof from the hamlet and waited for the German gunners and some ME-109's to finish the job. The garrison held on in the basements until the tanks finally moved in at dusk. Lieutenant Plankers had been informed in the course of the afternoon that neighboring troops were under orders to withdraw. He took the men he had left, now only about twenty, and broke through the Germans, rejoining what was left of the 394th Infantry at Mürringen late in the evening.

Even before the German penetration at the Losheimergraben angle, the 394th stood in danger of being cut off and destroyed piecemeal by the enemy infiltrating from the east and south. As part of a withdrawal plan put in effect during the afternoon for the entire division, General Lauer ordered the 394th to withdraw to a second defensive position at Mürringen, about four kilometers in the rear of the regiment's eastern front.

The 2d Battalion, holding the north flank, was under pressure from both right and left. At dawn of 17 December, the enemy had attacked along the Neuhof road with tanks in the van. Company E, directly in the path, used its bazookas with such good effect that three panzers were crippled. Excellent artillery support and fine shooting by the battalion mortars helped discourage any further frontal assault. Infiltration on the flanks, however, had placed the 2d Battalion in serious plight when, at 1400, the order came to withdraw west and tie in with the 3d Battalion. Leaving a small covering force behind, the 2d Battalion started on foot through the woods, carrying its heavy weapons over the rugged and snow-covered trails. The Germans also were moving through the forest, and the battalion was unable to turn toward the 3d as ordered. Withdrawing deeper into the forest the battalion bivouacked in the sector known as the Honsfelder Wald. The covering force, however, made its way to Mürringen, where it was set to defend the regimental command post.

The 1st Battalion, in the Losheimergraben sector, had been so splintered by incessant German-attack that its withdrawal was a piecemeal affair. Isolated groups fought or dodged their way west. Two hundred and sixty officers and men made it.9 Two platoons from Company K which had been attached to the 1st Battalion did not receive word of the withdrawal and held on under heavy shelling until ammunition was nearly spent. It took these men twenty-four hours to wade back through the snow to the regimental lines. What was left of the 3d Battalion also fell back toward Mürringen, harassed by groups of the enemy en route and uncertain as to what would be found at Mürringen.

The survivors of the 394th Infantry now assembling at Mürringen were given a brief breathing spell while the enemy concentrated on the 1st Battalion, 23d Infantry, defending the Hünningen positions 1,500 meters to the south. The 12th Volks Grenadier Division attack finally had broken through the American

[93]

line but now was definitely behind schedule. The 48th Regiment, having been much reduced in strength in the fight around Losheimergraben, re-formed on the high ground between the forest edge and Mürringen. The north flank of the regiment lay exposed to counterattack, for the 277th Volks Grenadier Division on the right had been checked in its attempt to take the twin villages, Krinkelt-Rocherath. The fight now devolved on the 27th Regiment, which was ordered to take Hünningen before an attempt to roll up the American south flank.

Colonel Hightower's 1st Battalion was in a difficult and exposed position at Hünningen. His main strength, deployed to counter German pressure from the Buchholz-Honsfeld area, faced south and southeast, but the German columns taking the Honsfeld-Büllingen detour were moving toward the northwest and thus behind the Hünningen defenders. Whether any part of this latter enemy force would turn against the rear of the 1st Battalion was the question.

Through the morning the 1st Battalion watched through breaks in the fog as tanks and vehicles rolled toward Büllingen. Visibility, poor as it was, made artillery adjustment on the road difficult and ineffective. Shortly after noon about 120 men who had been cut off from the 2d and 254th Engineer Battalions arrived at Hightower's command post and were dispatched to form a roadblock against a possible attack from Büllingen. Somewhat earlier twelve Mark IV tanks had appeared south of Hünningen-perhaps by design, perhaps by accident. Assembled at the wood's edge some 800 yards from the American foxhole line, the panzers may have been seeking haven from the American fighter-bombers then working over the road. In any case they were shooting-gallery targets. One of the towed 3-inch guns which the 801st Tank Destroyer Battalion had withdrawn during the early morning debacle at Honsfeld knocked out four of the panzers in six shots. The rest withdrew in haste.

At 1600 the enemy made his first definite assault, preceded by six minutes of furious shelling. When the artillery ceased, German infantry were seen coming forward through a neck of woods pointing toward the southeastern edge of Hünningen. A forward observer with Company B, facing the woods, climbed into the church steeple and brought down shellfire which kept pace with the attackers until they were within a hundred yards of the American foxholes. A number of the enemy did break through, but the assault evaporated when nearly fifty were killed by four men manning automatic weapons from a platoon command post just in the rear of the firing line. The commander of the 27th Regiment sent forward seven "distinct attacking waves" in the course of the afternoon and early evening. In one assault the Germans captured two heavy machine guns and turned them on Company A, but a light machine gun section wiped out the German crews. At no time, despite numerous penetrations in the 1st Battalion line, was the enemy able to get Hünningen into his hands.10 Late in the afternoon an indistinct radio message was picked up by the 1st Battalion, 23d Infantry. It appeared that the battalion now was attached to the 9th Infantry (2d Division), to the north, and that orders were to pull out of Hünningen.

[94]

Up to this point, the 394th Infantry was still in Mürringen, gathering its companies and platoons as they straggled in. Furthermore the 1st Battalion was in a fire fight with an enemy only a few score yards distant in the darkness. Colonel Hightower, therefore, tried by radio to apprise the 9th Infantry of his predicament and the importance of holding until the 394th could reorganize. At 2330 Colonel Hirschfelder, the 9th Infantry commander, reached Hightower by radio, told him that Hightower's battalion and the 394th Infantry were almost surrounded and that, if the battalion expected to withdraw, it must move at once. Colonel Hightower again explained his situation, said that in his opinion he could not pull out unless and until the 394th withdrew, but that he would discuss the situation with the commander of the 394th. Hirschfelder agreed and told Hightower to use his own judgment.

At Mürringen Colonel Riley's 394th had not been hard pressed although the German artillery had shown no favoritism and hammered Mürringen and Hünningen equally. The groups filtering back to Mürringen, however, generally had very little ammunition left, even though many detachments came back with all their heavy weapons. If the 394th was to make a stand at Mürringen it would have to be resupplied. At first Colonel Riley hoped to get ammunition by air, for it appeared that the German drive in the Krinkelt area to the north shortly would cut the last remaining supply road. This was a vain hope for aerial supply missions in December were far too chancy. The alternative solution was for the 394th to withdraw north to Krinkelt, using the one route still open.

The German Attack Toward Rocherath and Krinkelt

16-17 December

The 393d Infantry (Lt. Col. Jean D. Scott) had taken no part in the V Corps offensive of 13 December except to put on a "demonstration" in front of the West Wall positions. The regiment, minus its 2d Battalion (attached to the 395th Infantry), was deployed along the German frontier, a line generally defined by the eastern edge of the long forest belt in which the bulk of the 99th Division was stationed and the International Highway. The width of the front, held by the 3d Battalion on the left and the 1st Battalion on the right, was about 5,500 yards. Outposts on the regimental left lay only a few score yards from the West Wall bunkers, but the right was more than half a mile from the German lines. About four miles by trail behind the 393d, the twin villages of Rocherath and Krinkelt lay astride the main north-south road through the division area. In front of the 393d, across the frontier, were entrances to the two forest roads which ran through the regimental sector, one in the north at Hollerath, the second in the south at Udenbreth. Both villages were in enemy hands. At the western edge of the woods the roads converged, funneling along a single track into Rocherath-Krinkelt. The twin villages, therefore, had a tactical importance of the first order. Through them passed the main line of communications in the 2d Division corridor, and from them ran the supply route to the 393d Infantry and the 395th.

In the West Wall bunkers facing the 393d lay the 277th Volks Grenadier Division (Col. Hans Viebig). Reconstructed in Hungary from the remnants

[95]

of an infantry division of the same number which had escaped from the Falaise pocket, the 277th arrived in the west during early November. In the days before the counteroffensive the division screened the entire front behind which the I SS Panzer Corps was assembling, but on the evening of 15 December, while two new infantry divisions moved into the line, the 277th assembled on the north flank of the corps zone between Hollerath and Udenbreth. One reinforced battalion, on the far southern flank of the original sector, was unable to reach the division line of departure in time to join the attack.

The I SS Panzer Corps commander had decided to put the weight of his armored thrust to the south and thus avoid entanglement with the American force which, it was thought, could be gathered quickly on the Elsenborn ridge in the northern sector of the zone of advance. But the Elsenborn area had to be neutralized, if for no other reason than to erase the American artillery groupment located there. The 277th Volks Grenadier Division had the task of making the penetration on the right wing of the corps and driving obliquely northwest to take the Elsenborn ridge. As finally prescribed by the corps commander, the phases of the attack planned for the 277th were these: to break through the American line and open the forest roads to Rocherath and Krinkelt; capture these twin villages; seize the Elsenborn area and block any American advance from Verviers. The division commander had received this mission with qualms, pointing out that the wooded and broken terrain favored the Americans and that without sufficient rifle strength for a quick breakthrough, success in the attack could only be won by very strong artillery support. But his orders stood. On the night of 15-16 December the 989th Regiment assembled near Hollerath, its objective Rocherath. To the south the 990th occupied the West Wall pillboxes near Udenbreth, poised for an attack to seize Krinkelt.

The artillery, Werfer, and mortar fire crashing into the American positions on the morning of 16 December gave the attacking German infantry the start the 277th commander had requested. The concentration thoroughly wrecked the American telephone lines which had been carefully strung from battalion to company command posts; in some cases radio communication failed at the same time. This preparatory bombardment continued until 0700.

The north wing of the 393d, held by the 3d Battalion (Lt. Col. Jack G. Allen), lay in the woods close to the German pillboxes from which the assault wave of the 989th, guided by searchlights beamed on the American positions, moved in on the Americans before they had recovered from the shelling. In the first rush all of Company K, save one platoon, were killed or captured. By 0855, when telephone lines were restored and the first word of the 3d Battalion's plight reached the regimental command post, the enemy had advanced nearly three-quarters of a mile beyond the American lines along the forest road from Hollerath. Colonel Allen stripped the reserve platoons from the balance of the 3d Battalion line in a futile attempt to block the onrush, but by 0930 the Germans had reached the battalion command post, around which Allen ordered Companies I and L to gather.

[96]

At this point the 81-mm. mortar crews laid down such a successful defensive barrage (firing over 1,200 rounds in the course of the fight) that the attackers swerved from this area of danger and continued to the west. By nightfall the forward companies of the 989th were at the Jansbach creek, halfway through the forest, but had been slowed down by troops switched from the left wing of the 3d Battalion and had lost many prisoners to the Americans. The 3d Battalion radio had functioned badly during the fight and contact with the 370th Field Artillery Battalion, supporting the 3d, was not established till the close of day. Despite the penetration between the 3d and 1st Battalions and the large number of enemy now to the rear and across the battalion supply road, Colonel Allen reported that the 3d could hold on during the night. His supply road had been cut in midafternoon, but Company I of the 394th had fought its way in with a supply of ammunition.

On the south the 1st Battalion (Maj. Matthew L. Legler) likewise had been outnumbered and hard hit. Here the 990th Regiment had assembled in Udenbreth during the dark hours and, when the barrage fire lifted at 0700, began an advance toward the 1st Battalion. The German assault companies, however, failed to get across the half mile of open ground before dawn and were checked short of the woods by mortar and machine gun fire. The commander of the 277th Volks Grenadier Division at once decided to throw in his reserve, the 991st Regiment, to spring the 990th loose. Sheer weight of numbers now carried the German attack across the open space and into the woods-but with high casualties amongst the riflemen and the officers and noncoms herding the assault waves forward. By 0830 the Germans had nearly surrounded Company C, on the 1st Battalion right. An hour later, the 991st Regiment, attacking southwest from Ramscheid, knocked out the light machine guns and mortars in the Company B sector (on the left) with bazooka fire and captured or killed all but one platoon. Company A (Capt. Joseph Jameson), which had been in reserve, counterattacked in support of what was left of Company B and by noon had dug in on a line only 300 yards behind the original line. Here Company A held for the rest of the day against repeated enemy attacks and constant artillery fire with what the regimental after action report characterized as "heroic action on the part of all men." In this fight friendly artillery played an important role. The surviving Company B platoon had retained an observation post overlooking the treeless draw along which reinforcements moved from Udenbreth and despite the German fire a telephone wire was run forward to this command post. The American gunners quickly made this avenue suicidal; through the afternoon cries from the wounded Germans lying in the draw floated back to the American line.

Company C on the 1st Battalion right had slowly succumbed to the weight of numbers; by 1015 two of its platoons had been engulfed. There was little that the regiment could do in response to Major Legler's plea for assistance, but at 1030 the mine-laying platoon from the regimental antitank company arrived to give a hand. This small detachment (26 riflemen plus 13 runners and cooks), led by Lt. Harry Parker, made a bayonet charge to reach the remaining

[97]

Company C platoon and set up a new line of defense on the battalion right flank. A gap still remained between the battalion and the 394th Infantry farther south.

By the end of the day the 393d Infantry had restored a front facing the enemy. 11 But the new line could hardly be called solid, the rifle strength remaining was too slim for that. The 1st Battalion had lost over half of its effective strength; the 3d Battalion had its right bent back for several hundred yards and had lost nearly three hundred men. The enemy wandered almost at will through the woods, firing into foxholes, shooting off flares, and calling out in English to trap the unwary. But even with the German strength apparent on all sides, the American situation seemed to be improving. Reinforcements, requested by General Lauer, had arrived from the 2d Division during the late afternoon, the supply roads might be restored to traffic when daylight came again, and the losses inflicted on the attacker were obvious and heartening.

The breakthrough on the south flank of the 99th Division, during 17 December, was paralleled that day by a strong German armored thrust into the division center. The 393d, whose left battalion had been driven back into the deep woods during the first day's attack, was under orders to counterattack and restore its original line. The 3d Battalion was close to being surrounded, and in order to recover its eastern position at the wood line it would have to reopen the battalion supply road. At 0800 Colonel Allen's tired and weakened battalion attacked to the west and drove the enemy off the road, but when the eastward counterattack started it collided with a battalion of German infantry. For half an hour Germans and Americans fought for a hundred-yard-wide strip of the woods. Then, about 0800, the German armor took a hand.

The failure by the 277th Volks Grenadier Division to clear the woods and reach Krinkelt-Rocherath on 16 December had led to some change of plan. The right flank, roughly opposite the 3d Battalion sector, was reinforced by switching the 990th Regiment to the north to follow the 989th Regiment. More important, the 12th SS Panzer Division (which now had come up on the left of the 277th) parceled out some of its tanks to give weight to the infantry attack by the right wing of the 277th Volks Grenadier Division.

The first tank entered the forest road from Hollerath, rolled to within machine gun range of the Americans, stopped, then for twenty minutes methodically spewed bullet fire. Attempts to get a hit by artillery fire were futile, although the American shelling momentarily dispersed the accompanying infantry and permitted a bazooka team to wreck one track. But even when crippled the single tank succeeded in immobilizing the American infantry. Four more enemy tanks appeared. One was knocked out by a bazooka round, but the rest worked forward along the network of

[98]

firebreaks and trails.12 The combination of tanks and numerous infantry now threatened to erase the entire 3d Battalion position. Ammunition had run low and the 3d Battalion casualties could not be evacuated.

About 1030 Colonel Scott ordered the 3d Battalion, 393d Infantry, as well as its southern neighbor (the 1st), to remove to new positions about one and a half miles east of Rocherath. This would be done by withdrawing the 3d Battalion through the 3d Battalion, 23d Infantry (the reinforcements sent by Robertson), which had dug in some thousand yards to its rear. All the vehicles available to the forward troops were filled with wounded. Fifteen wounded men, most too badly hurt to be moved, were left behind, together with the 3d Battalion surgeon, Capt. Frederick J. McIntyre, and some enlisted aid men. By noon the entire battalion had pulled out (disengaging without much difficulty); it passed through the 3d Battalion, 23d Infantry, and two hours later was on the new position. Allen's battalion had fought almost continuously since the early morning of the 16th; then at full strength, it now was reduced to 475 men and all but two machine guns were gone.

The 1st Battalion of the 393d Infantry had not been hard pressed during the morning of 17 December because the German forces in its area had been content to move through the gap on the right, between the 393d and 394th. Ordered to withdraw about 1100, the battalion was in position alongside the 3d Battalion, 23d Infantry, by 1400, the two now forming a narrow front east of the twin villages.

The 3d Battalion, 23d Infantry (Lt. Col. Paul V. Tuttle, Jr.), had been rushed to the western edge of the woods on the afternoon of the 16th for use as a counterattack force. The hard-hitting German attack against the 3d Battalion, 393d, on the following morning so drastically changed the situation that Colonel Tuttle's orders were altered to: "hold at all costs." His battalion was none too well prepared for such defense, having arrived with no mines and very little ammunition. Trucks bringing ammunition forward found the road between Büllingen and Krinkelt barred by the enemy and never reached the battalion.

Shortly after the troops from the 393d passed through the battalion, Company I, on the open left flank, heard the clanking of tank treads. A few minutes later German tanks with marching infantry clustered around them struck the left platoon of Company I, rolling forward till their machine guns enfiladed the foxholes in which the American infantry crouched. Company I held until its ammunition was nearly gone, then tried to withdraw to a nearby firebreak but went to pieces under fire raking it from all directions.13 Company K, in line to the south, next was hit. The company started an orderly withdrawal, except for the left platoon which had lost its leader and never got the order to pull back. This platoon stayed in its foxholes until the tanks had ground past, then rose to

[99]

CAMOUFLAGED PILLBOX IN THE FOREST serves as a regimental command post.

engage the German infantry. The platoon was wiped out.

A medium tank platoon from the 741st Tank Battalion, loaned by Robertson, had arrived in the 3d Battalion area during the night. Lt. Victor L. Miller, the platoon leader, took two tanks to cover a forest crossroads near the Company K position. In a duel at close quarters the American tanks destroyed two panzers, but in turn were knocked out and Lieutenant Miller was killed.

Parts of Company K held stubbornly together, fighting from tree to tree, withdrawing slowly westward. For courage in this fight, Pfc. Jose M. Lopez, machine gunner, was awarded the Medal of Honor. This rear guard action, for the company was covering what was left of the battalion, went on until twilight. Then, as the survivors started to cross an open field, they were bracketed by artillery and Werfer fire and scattered. (Later the battalion would be given the Distinguished Unit Citation.) Company L, on the inner flank, had been given time for an orderly retreat; eighty or ninety men reached Krinkelt.

The 3d Battalion of the 393d had barely started to dig in behind the 3d Battalion, 23d Infantry, when the first stragglers came back with word of the

[100]

German assault. Colonel Allen moved his spent battalion to a hastily organized position 500 yards to the northwest and prepared to make another stand. The main force of the German attack, however, had angled away while rolling over the flank of the forward battalion. About this time the 3d Battalion, 393d, met a patrol from the 1st Battalion, 9th Infantry, which had been rushed to the Rocherath area to cover the 2d Division withdrawal south from Wahlerscheid, and the two battalions joined forces.

The retreat of the 3d Battalion, 23d Infantry, left its right-flank neighbor, the 1st Battalion, 393d Infantry, completely isolated.14 Telephone lines long since had been destroyed, and radio communication had failed. In late afternoon Major Legler decided to withdraw but hearing that the 2d Battalion of the 394th was to tie in on his right reversed his decision. About dark, however, the Germans struck in force and the rifle companies pulled back closer together. Because the battalion supply road was already in German hands, Legler and his men struck out across country on the morning of the 18th, taking a few vehicles and those of the wounded who could be moved. The main body reached Wirzfeld but the rear guard became separated, finally joining other Americans in the fight raging around Krinkelt. The 1st Battalion by this time numbered around two hundred men.

The 395th Infantry Conforms to the Withdrawal

The 395th Infantry, which had supported the 2d Infantry Division attack in the Wahlerscheid sector, was little affected on the 16th and the morning of the 17th by the German power drive against the rest of the 99th Division. Information reaching the 395th command post was sparse and contradictory; both the 2d Division and the 395th still assumed that the battle raging to the south was an answer to the American threat at Wahlerscheid, where the 2d Division had made a sizable dent in the West Wall by evening of 16 December.15

All this time a chain reaction was moving slowly from the menaced southern flank of the 99th northward. It reached the 395th before noon on 17 December with word that the 324th Engineer Battalion, stationed between that regiment and the 393d, was moving back to the west. Actually the engineers had not yet withdrawn but had moved to make contact with and cover the exposed flank of the 395th, this apparently on General Lauer's orders while the 395th was taking orders from Robertson. The withdrawal of the 2d Infantry Division to the Rocherath area resulted in the attachment of the 395th (reinforced by the 2d Battalion of the 393d) to General Robertson's division. Now the battalions were ordered to blow up all of the pillboxes taken in the advance. Finally, at 1600, Col. Alexander J. Mackenzie received a retirement order given by General Lauer or General Robertson, which one is uncertain. The plan was this. The two battalions of the 395th and the attached battalion from the 393d would fall back toward the regimental command post at Rocherath. From this

[101]

point the regiment would deploy to cover the road leading out of Rocherath to the north and northeast, the road which the 2d Infantry Division was using in its march south from the Wahlerscheid battlefield.

The 1st Battalion reached Rocherath and on General Robertson's orders entrenched on both sides of the road north of the village. Heavy weapons were dragged through the deep mud and were placed to cover the road. The other two battalions dug in along a perimeter which faced east from Rocherath and the Wahlerscheid road. So emplaced, the 395th waited for the enemy to come pouring through the woods onto the 2d Division route of withdrawal.

On the opposite side of the 2d Division corridor, in the Höfen area, the enemy made no serious move on 17 December to repeat the disastrous attack of the previous day. The immediate objective of the 326th Volks Grenadier Division remained the high ground northwest of Monschau near Mützenich. General Kaschner apparently decided on 17 December to make his bid for a breakthrough directly in this sector and to abandon momentarily the attempt to force a penetration between Monschau and Höfen.