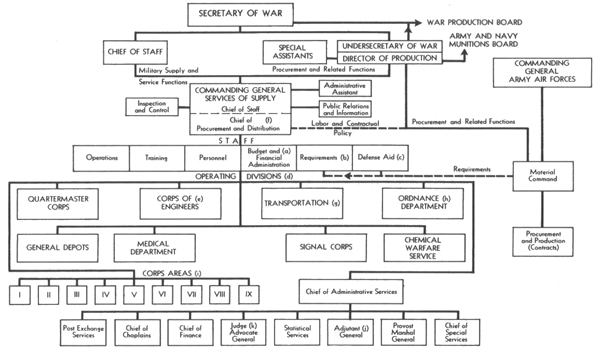

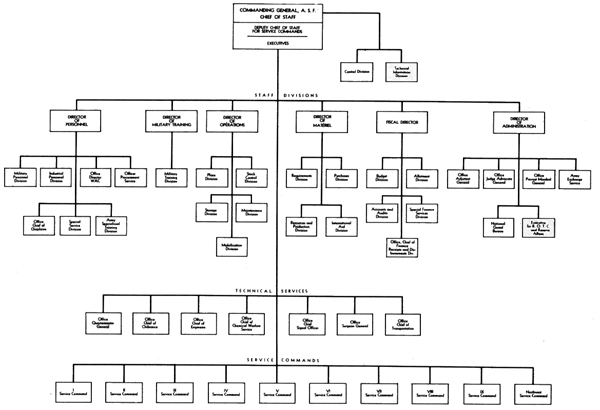

CHART 2 : ORGANIZATION OF THE SERVICES OF SUPPLY: 20 FEBRUARY 1942

In addition to the six supply arms and services and the nine corps areas, the Army Service Forces absorbed eight administrative "bureaus," parts of the War Department General Staff, and the Office of the Under Secretary of War, as related earlier. These last three elements were eventually built into a single structure called Army Service Forces headquarters. The concept of such a headquarters emerged slowly; it was no overnight product. So complicated is the story that only the major organizational developments can be treated in this chapter.

The Merging of the OUSW and G-4

The first organizational challenge that faced General Somervell after 9 March 1942 was the need for some kind of integrated machinery above the level of the technical services to calculate supply requirements, to direct procurement operations, and to control the distribution of available weapons and equipment. The merging of the OUSW and the G-4 Division of the War Department General Staff, one of the principal advantages resulting from the creation of the ASF, provided such machinery. At the beginning of 1942 the Office of the Under Secretary of War numbered about 1,200 officers and civilians. The Supply Division (G-4) of the General Staff had about 250 officers and civilians.

The OUSW consisted of a Resources Branch, a Procurement Branch, a Statistics Division, and an Administrative Branch. The Resources Branch was concerned with raw materials, machine tools, manpower, and labor matters. The Procurement Branch handled contract and legal questions, insurance, and production expediting. The Administrative Branch supervised tax amortization and accounting and finance services for contractors as well as general management services for the Office of the Under Secretary. The separate Statistics Division prepared monthly reports on procurement progress.

G-4, WDGS, had six branches-Planning, Supply, Construction, Transportation, Fiscal, and Development. The Planning Branch was generally concerned with planning the supply aspects of prospective military operations. The Supply Branch was responsible for estimating requirements and for distributing supplies and equipment. The Construction Branch handled construction requirements and supervised the purchase of real estate. The Transportation Branch exercised general supervision over transportation activities and for all practical purposes directed the

operation of ports of embarkation. The Fiscal Branch was the General Staff agency for putting together the War Department budget. The Development Branch supervised the research programs of the supply arms and services.

In the Initial Directive for the Organization of the Services of Supply, General Somervell created .two positions in his own office entitled Chief of Procurement and Distribution, and Deputy Chief of Staff for Requirements and Resources.1' (See Charts 2, 3, 4.) Presumably the two posts were separate and neither subordinate to the other. The Deputy Chief of Staff was supposed to represent the commanding general on all matters involving the development of the Army Supply Program, the assignment of lend-lease military supplies, and raw material problems including relations with the War Production Board. The Director of Procurement and Distribution was responsible for questions involving the procurement and distribution of supplies. As might be expected, the line of demarkation between the two was by no means clear. The first position was filled by General Clay, formerly in G-4, while the second post was held by Col. Charles D. Young, who had been in the Under Secretary's office. This arrangement broadened Clay's concern with Army requirements to include raw material requirements, and enlarged Young's duties to include the distribution of supplies after they were procured. The initial directive also created the following "functional staff " divisions: Requirements, Resources, Procurement, Distribution, Defense Aid (lend-lease), Operations, Personnel, Training, and Budget and Financial Administration.

The Requirements Division directed the preparation of the Army Supply Program. It combined parts of three branches of G-4 and a part of the Procurement Branch of the OUSW The Resources Division was a branch taken entirely from OUSW The Procurement Division was made up of elements from both G-4 and OUSW; the same was true of the Distribution Division. The Defense Aid Division brought together personnel in a unit under the former Deputy Chief of the War Department General Staff, G-4, and OUSW The Operations Division came entirely from G-4. The Personnel Division was composed mainly of officers from G-1 Division of the WDGS. The Training Division had to be built from scratch mainly with G-3 and technical service personnel. Finally, the Budget and Financial Administration Division combined units of both G-4 and OUSW. Thus the new functional staff of the ASF endeavored to draw together parts, especially of G-4 and OUSW, having common interests.2

This initial arrangement was purely experimental. For example, on 17 March, just eight days after the ASF was organized, the procurement and distribution units were combined into a single Procurement and Distribution Division with the former Chief of Procurement and Distribution as director, a post no longer on a par with the Deputy Chief of Staff for Requirements and Resources in the commanding general's office.3 After one further abortive attempt to set up a Deputy Chief of Staff for Procurement and Distribution,4 the status of procurement and distribution as a staff division

CHART 2 : ORGANIZATION OF THE SERVICES OF SUPPLY: 20 FEBRUARY 1942

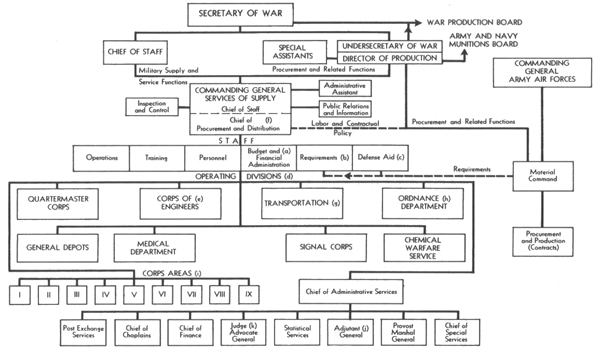

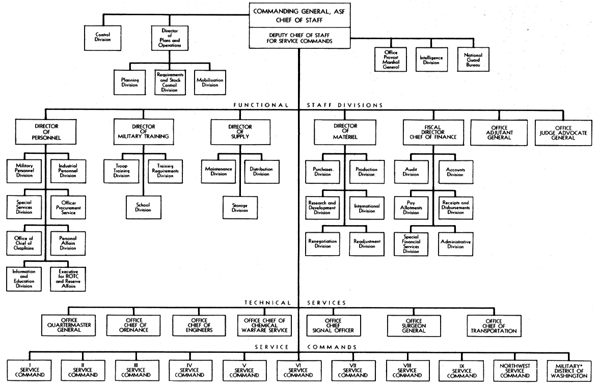

CHART 3 : ORGANIZATION OF THE SERVICES OF SUPPLY : 16 FEBRUARY 1943

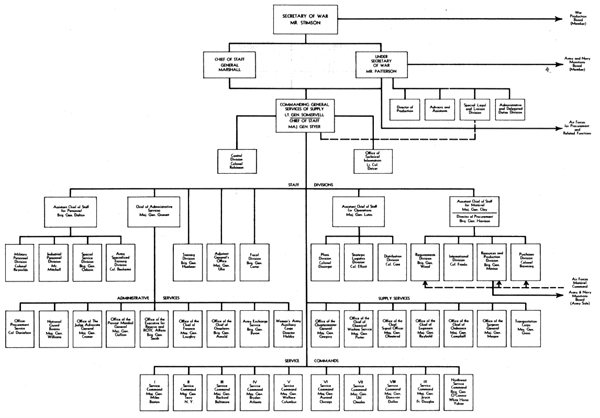

CHART 4 : ORGANIZATION OF THE ARMY SERVICE FORCES : 10 NOVEMBER 1943

was confirmed.5 The details of various subsequent staff organization changes are not as important here as an understanding of the basic organization problem in ASF headquarters pertaining to procurement and supply matters.

It must be remembered that ASF headquarters developed no new or improved weapons, let no contracts, operated no manufacturing plants, inspected no completed military articles, stored no supplies, and issued or shipped no military equipment. All these activities were performed by the technical services. ASF headquarters was a mechanism solely for insuring that all this work was performed according to plan. The organizational problem facing ASF headquarters was to determine what phases of military procurement and supply required central direction, emphasis, and follow-up. In other words, what interests shared in common by the technical services needed staff supervision?

Necessarily, changing circumstances produced new needs. For the duration of the war, however, ASF headquarters recognized certain definite functions common to all the technical services which demanded some degree of central direction. The first of these was research and development of new or improved weapons. Initially, this was a relatively small interest for ASF headquarters taken over from a unit in G-4 and combined with the supervision of procurement and distribution. Later supervision of development activities was lodged with the requirements division. It was not until May 1944 that a separate staff division for research and development was set up in ASF headquarters.6 Thereafter, partly because of pressure from the War Department staff, ASF headquarters gave increasing attention to promoting research activity in the technical services. But generally, the ASF staff role on development matters was a modest one.

The central control of purchasing policies and procedures was an important function of the ASF staff. As early as 17 March 1942 a Purchases Branch was established within the Procurement and Distribution Division.7 Later, in July 1942, a separate Purchase Division was set up.8 It was an extremely active staff office, developing and promulgating the procurement regulations which set forth standard purchasing policies to be observed by the technical services. It also watched over the prices paid for military equipment. Two parts of the Purchases Division's work became so important that new staff divisions were created to handle them. One of these was the supervision of the renegotiation of contracts where originally determined prices proved to be unduly high. A renegotiation division came into being in August 1943.9 By November 1943 the work in preparing and supervising policies on the settlement of terminated contracts had become so important that a Reconversion Division was set up.10 The designation was changed to Readjustment Division the same month.11

The control of procedures for calculating technical service needs for raw materials such as steel and copper, the presentation of these needs to the War Production Board, the allotment of raw materials supplies among Army procurement programs, and the conservation of materials had all been vital problems be-

fore the ASF was created arid were recognized as a major staff responsibility from the very beginning of the ASF. The Resources Division in charge of this work was taken over intact from the Office of the Under Secretary, as mentioned earlier. But as part of its work in determining new plant facility needs and in expediting production schedules, the Production and Distribution Division was also interested in the availability of raw materials. A separate Production Division was created in the ASF staff in July 1942 at the time that the Purchases Division was set up. Then in December, the Resources Division and the Production Division were combined into a single Resources and Production Division.12 Eventually it was called just the Production Division. 13 Thus, production supervision became a major staff function.

Before examining the staff evolution of distribution activities, one peculiar function must be mentioned. The Defense Aid Division (renamed the International Division in April 1942) handled military lend-lease, a task which required special consideration throughout the war. In the beginning General Somervell was much concerned that lend-lease demands be fully included in the Army Supply Program and carefully adjusted to American Army needs as well as to production feasibility. Later, military lend-lease involved primarily the assignment of American Army supplies to other nations in accordance with broad strategic directives. It was such an important supply activity that it was directed by a separate staff agency throughout the war. Once supplies were assigned, someone had to follow the matter closely to make sure that they were actually shipped. From 1943 on, supplies to be used in the military government of conquered territories became an ASF problem handled by its International Division.

All of the staff functions just mentioned-the supervision of research and development, of purchasing policy, of renegotiation of contracts, of the termination and settlement of contracts, of raw material distribution and production expediting, and of lend-lease-were brought together under single direction within ASF headquarters. It took time to develop the concept of a number of staff divisions in ASF headquarters under a single director. But this idea was recognized by April 1942 when the Deputy Chief of Staff for Requirements and Resources was designated to direct three staff divisions: requirements, resources, and international.14 The title of Assistant Chief of Staff for Materiel was introduced in July 1942,15 and in turn gave way to the designation Director of Materiel in May 1943.16

The staff assignment for supervising procurement requirements had an interesting evolution. Before 9 March 1942, War Department instructions to the supply arms and services on procurement requirements originated in G-4. But all production aspects of the program, including control of raw materials, were supervised by the Under Secretary. It was the vital interrelationship of procurement programming and raw materials distribution which General Somervell sought to recognize when the position of Deputy Chief of Staff for Requirements and Resources was created in ASF headquarters.

As already mentioned, this post was at first assigned to General Clay, who remained in charge until June 1944.

This juxtaposition of procurement planning and production control was probably justified in 1942 when all equipment needs were in short supply and production limitations largely determined the supply program. In time these conditions changed. More and more procurement needs came to be calculated as a part of strategic and logistical planning. Moreover, when procurement requirements were too closely tied to production expediting, there was a marked tendency to overproduce some items and to permit shortages to arise in others. General Somervell eventually concluded that it was a mistake to assign staff supervision over procurement planning to the same person who had responsibility for production performance.

In 1942 control over the distribution of supplies, a former G-4 activity, had been joined in the staff with direction of production. This was the organizational answer to moving supplies from production lines to troops. But in constructing the original headquarters organization General Somervell also provided for an Operations Division. This division was to plan overseas troop and supply movements. Gen. LeRoy Lutes, who was placed in charge, had earlier while in G-4 developed the procedure for the supply of overseas theaters of operations, a procedure which endured with slight modification throughout World War II. Moreover, he was already emerging as the key figure in supply planning-not just within the ASF but within the entire War Department. General Lutes was not satisfied with the existing staff arrangements for supervising the distribution of supplies, since the authority to issue orders to technical services on the actual movement of supplies was indispensable for the successful execution of his planning. As early as April 1942 an effort was made to define the respective responsibilities of the Procurement and Distribution Division and the Operations Division.17 Among other duties, it was agreed, the Operations Division would henceforth issue orders to the technical services on the supply needs of overseas theaters and of troops on their way overseas. It would also plan the general system of supply distribution both overseas and within the zone of interior. The Distribution Branch within the Procurement and Distribution Division would supervise the actual physical storage of supplies within depots in the United States. This demarkation did not prove satisfactory and was scrapped entirely in July. The Procurement and Distribution Division as an experiment in staff organization thus lasted only four months, from March to July 1942.

A new staff organization was set up under General Lutes as Assistant Chief of Staff for Operations. 18 The Operations Division was now called the Plans Division, and the Distribution Branch became the Distribution Division under General Lutes. A strategic logistics unit was added in August for long-range overseas supply planning.19

Then in April 1943, following a study by General Somervell's control office, Lutes undertook a complete reorganization of his responsibilities.20 A new ASF order called for five divisions under the

Assistant Chief of Staff.21 A Planning Division combined long-range strategic supply planning with the handling of immediate overseas supply needs. It was the connecting link between ASF headquarters and overseas theaters of operations. A Distribution Division supervised the machinery for maintaining inventory control records of all supplies and watched over general developments in the system for distributing supplies. For instance, it policed the new stock control system set up for military posts within the United States .22 A Storage Division, under a reserve officer who was an experienced warehouseman, directed improvements in the physical handling of supplies, such as the introduction of fork lift machinery, and kept careful records of the utilization of storage space. A Mobilization Division, besides having responsibility for directing the movement of ASF troop units, also exercised important coordinating functions in the supply and transportation phases of the movement of other Army units. This division was also responsible for the organization of ASF troop units. Finally, a Maintenance Division checked upon the repair of troop equipment and its return to using units or to stock for re-issue. This new organization under the Assistant Chief of Staff for Operations recognized major supply functions of common concern along functional lines.

In the autumn of 1943 the Distribution Division (renamed Stock Control), the Storage Division, and the Maintenance Division, were grouped together under a Director of Supply, Maj. Gen. F. A. Heileman who had served as General Lutes' assistant since July 1942.23 At the same time General Lutes was designated Director of Plans and Operations and along with his Planning Division and Mobilization Division was brought into the immediate office of the commanding general. This organizational change was intended to impress upon General Clay as director of materiel that Lutes would plan both the procurement and the distribution of supplies. But Clay was disposed to go his own way and Lutes was not inclined to raise a jurisdictional issue. Actually, the previous organization of ASF headquarters largely prevailed. General Heileman, while called Director of Supply, was still General Lutes' assistant. And Lutes went right on directing the overseas supply operations of the ASF with such assistance from General Clay's procurement activities as he could obtain.

A substantial organizational change was introduced in July 1944. By the spring of 1944 it had become apparent that procurement planning had moved into a new phase, making it possible to compare actual supply consumption with supply forecasts, and gear production demands to issue experience and stocks on hand. The answer was the evolution of the Army Supply Program into the Army Supply Control System, established in May 1944. In June the Requirements Division under General Clay and the stock control activities under General Heileman were merged into a single Requirements and Stock Control Division under General Lutes.24 The former head of the Requirements Division became General Lutes' principal assistant in overseas supply planning. Procurement planning and supply distribution were joined in one staff division under an officer also responsible for logistical planning.

Mention of some of the major problems facing the ASF staff on logistical planning will help illustrate why it was necessary to have a staff supervising the supply activities of the technical services. Some instances of ammunition shortages in Europe in 1944 were traced primarily to two factors. One was the failure to identify fully ammunition by calibers when it was shipped overseas in quantities by the Ordnance Department and the Transportation Corps. The other was the inadequate estimates of needs by overseas theaters. Moreover, the Ordnance Department felt that ammunition was being wasted, and in consequence had no strong incentive to raise production levels. This led General Lutes' office to put pressure on the production officials to increase output, on overseas theaters to increase their requisitions, and on the shipping personnel to manifest cargo more fully. Furthermore, it recognized that while the Transportation Corps was the shipping agent for all overseas supply, some central point had to provide instructions about the quantities of various supplies to be shipped to each theater. The development of a standard procedure for preparing troops for overseas movement (called POM) was of immense importance in determining the types of supplies needed, and in establishing definite supply schedules to maintain troops at overseas destinations. These are but a few examples of supply planning, which, all in all, attained a high level of performance during World War II.

The ASF staff structure in effect at the end of the war gave the Army Service Forces the best solution it could find to the problem of merging procurement planning and supply distribution. Organizationally, a Director of Plans and Operations, nominally a part of the commanding general's immediate office, was responsible for procurement planning and overseas supply planning; the essential feature of such planning was the supply control system. This office also supervised the determination of needs for service troop units overseas. It directed all troop movements. The staff activities concerned with depot operations, stock control procedures, and maintenance work were brought together under a Director of Supply. Research and development, purchasing policy (including renegotiation of contracts and the settlement of terminated contracts), production expediting including the distribution of raw materials, and lend-lease distribution, were organized under a Director of Materiel.

Yet it was General Somervell who personally effected such co-ordination of procurement and supply activities as was accomplished. His staff divisions were simply the institutional arrangements which made possible a personal direction of all phases of military supply.

The ASF as set up on 9 March included eight miscellaneous administrative "bureaus" of the War Department. These were the Offices of The Adjutant General, the Judge Advocate General, the Chief of Finance, the Chief of Chaplains, the National Guard Bureau, the Executive for Reserve and ROTC Affairs, the Provost Marshal General, and the Chief of Special Services. Each of these offices had functioned under the Chief of Staff, in actual practice dealing with various divisions of the War Department General Staff. Each performed miscellaneous duties, most of which were but slightly related. Most of the "bureaus" were of long standing, ex-

cept the Special Services which had been set up during 1941 to direct certain morale, recreational, and welfare functions for soldiers.

When the ASF was created, General Somervell and his immediate /aLdvisers were uncertain how to handle these bureaus. At first they were labeled "administrative services" and were regarded as a third operating element, alongside the technical services and the service commands. Certain adjustments were made in their organization. The National Guard Bureau and the Executive for Reserve and ROTC Affairs were directed to report to The Adjutant General. By this time both agencies were mainly concerned with personnel records, since the National Guard had been federalized and most of the Reserve officers and men had been called to active duty. The Special Services as it had functioned before 9 March was split into two parts. One, still called Special Services, handled recreational and morale activities, while the other, renamed the Post Exchange Service, supervised the operation of Army post exchanges. Brig. Gen. Frederick H. Osborn, who had been commissioned from civilian life to direct these activities, was temporarily designated as chief of both services. Within a short time General Somervell obtained another officer from civilian life, Col. Joseph W. Byron, to direct the affairs of the Army Exchange Service. Finally, the Statistical Division of the OUSW was taken over and redesignated the Statistical Service. It remained under the direction of Brig. Gen. Leonard P Ayres, who had been recalled to duty to make statistical studies similar to those on World War Studies that had won widespread recognition. Of the eight administrative bureaus inherited on 9 March, the ASF merged three into one, divided another into two parts, and added a new one. The end result was still eight administrative services.

Without endeavoring to follow the organizational vicissitudes of these administrative services in all their details, three important phases of subsequent developments may be noted. First, the concept of administrative services as operating units of the Army Service Forces was abandoned in favor of making these services integral parts of the ASF headquarters staff. Second, the idea of a Chief of Administrative Services to supervise the diverse activities of these various agencies proved impractical. Third, a number of subsequent adjustments were made in the composition of these agencies. None of these changes came suddenly. They evolved over the entire period of World War II.

In taking over this heterogeneous group of agencies, General Somervell was at first intent on imposing as little direct or personal burden of supervision upon himself as possible. Accordingly, the initial directive on ASF organization specified that there should be a "division, in charge of a Chief of Administrative Services . . ." to direct, supervise, and co-ordinate the functions and activities of the eight specified agencies. This seemed to suggest the creation of an "administrative service" within the ASF under a chief who was an operating, not a staff, officer. Actually, the language never had any real meaning. From the outset the Chief of Administrative Services found himself in an anomalous position. He was presumably a sort of commanding officer over a group of agencies which had almost nothing in common, which had numerous relations with many other parts of the ASF and of the War Department, and whose policy problems raised issues which General Somervell

could not ignore. The first change came within a month, when a new order on general ASF organization provided that the Chief of Administrative Services was an ASF staff officer.25 Yet he was still represented as having some sort of "line" authority over the administrative services. In July 1942, when the service command reorganization was in process, another reorganization of ASF headquarters took place. This began the process of absorbing administrative services into the ASF staff. The Office of the Chief of Special Services was moved into the personnel staff and renamed the Special Services Division. The Adjutant General became a separate staff officer for the commanding general. Although the Chief of Administrative Services remained, he had lost some of his responsibilities.26

By May 1943 it was apparent to General Somervell and his organization advisers that the concept of "administrative services" lacked reality. Most of these field activities had been transferred to the service commands in August 1942 and subsequently. Certainly the administrative services were not operating elements of the ASF in the same sense as the technical services or service commands. So the term "administrative service" was dropped and the offices were viewed as staff units of ASF headquarters. The position of Chief of Administrative Services was transformed into a Director of Administration, with certain staff offices assigned to his supervision; namely, The Adjutant General, the Judge Advocate General, the Army Exchange Service, the Provost Marshal General, the National Guard Bureau, and the Executive for Reserve and ROTC Affairs.27

The position of Director of Administration was abolished in November 1943.28

It was not revived during the remainder of the war. The staff units that had reported to the Director of Administration were assigned to other staff directors, and The Adjutant General and the Judge Advocate General reported directly to the commanding general.

The organizational fate of each of the original administrative services may be noted briefly. The positions of the judge Advocate General, the Provost Marshal General, and the Chief of Chaplains were not substantially altered throughout the war. Their duties remained much the same, even though they functioned as staff agencies of the ASE Other administrative services fared differently. The Statistical Service, created as a new administrative service on 9 March 1942, was abolished effective 1 July 1942.29 Its statistical activities were divided among all staff agencies, each of which was expected to use statistical reporting and analytical techniques in its supervisory responsibilities. General oversight of all statistical reporting and of ASF performance as a whole was vested in the Control Division.

The most radical change in a long established War Department bureau was that involving the Chief of Finance. As previously noted, the ASF at the start set up a Fiscal Division as a part of its staff organization. This division combined certain budgetary and other fiscal duties previously vested in G-4 and OUSW. The Chief of Finance, on the other hand, became one of the administrative services. A demarkation line between the two offices proved difficult to draw, and so for a time

the ASF had in effect two staff offices concerned with fiscal matters .30 The answer was an amalgamation of the two, the Chief of Finance becoming deputy fiscal director .31 If personality factors had been different, the arrangement might have been reversed. The ASF Fiscal Director, Maj. Gen. A. H. Carter, enjoyed the complete confidence of Under Secretary Patterson; the Chief of Finance, Maj. Gen. Howard K. Loughry, a Regular Army officer, had not been especially aggressive in modernizing accounting practices to meet war circumstances.

As already noted, General Somervell divided the Office of the Chief of Special Services into two parts when the ASF was created. Later he decided this differentiation had not gone far enough. The designation "special services" then was used to refer to a combination of all recreational activities from the post exchange to athletic programs, from motion picture theaters to USO theatrical units. The original special services, or Special Services Division, became the Information and Education Division concerned exclusively with the transmission of general information to troops and the operation of education programs through the radio, newspapers and magazines, motion picture, correspondence courses, and other media .32 The personnel and administrative requirements of the two services proved quite different in practice.

Finally, The Adjutant General's status was changed in two particulars. In addition to the central administrative services he rendered to the War Department as a whole, he also became the manager of internal housekeeping services for ASF headquarters. The other change was the loss of the National Guard Bureau and the Executive for Reserve and ROTC Affairs.

On 17 March 1942 the National Guard Association sent a resolution to the Secretary of War and to the Chief of Staff protesting that War Department Circular 59 "apparently emasculates and destroys the function and authority" of the National Guard Bureau. The association asked "that the Bureau be lifted from its obscure position in the Office of The Adjutant General of the Army to the status of an operating division of the Services of Supply." 33 When appearing before the House Committee on Appropriations on 21 March 1942 General Somervell was questioned on the National Guard Bureau. He bluntly stated: "No other branch of the Army feels that it has the authority to go out on its own to seek to nullify the decisions of the Chief of Staff and the Secretary of War." 34 Mr. Starnes of the committee expressed the opinion: "I think you should give consideration to the Committee's feelings and those of the National Guard Bureau." To this General Somervell replied, "The committee can be assured that we will give full consideration to anyone's feeling." 35

General Somervell's reluctance to pledge an adjustment in the status of the National Guard Bureau is easily explained. He feared that pressure brought to bear on behalf of the National Guard Bureau might be an entering wedge for many other pressures intended to break down the War Department reorganization

of 9 March. Accordingly, he did not wish to acknowledge any justification for the criticisms voiced by the House Committee on Appropriations. By virtue of its close relations with state administrations, the National Guard Bureau was a special concern of many Congressmen. The opposition to this particular part of the 9 March reorganization came largely from officers in various states who had not been mobilized into the Army of the United States. Even though the National Guard itself was now a part of the Army; there were still many individuals who wished to maintain close relations between state military programs and the War Department. These groups looked with disfavor upon the assignment of the National Guard Bureau to The Adjutant General's office.

On 27 April 1942 General Somervell made the National Guard Bureau a separate administrative service under the Chief of Administrative Services.36 On 27 June 1942 he made a similar change in the Office of the Executive for Reserve and ROTC Affairs.37 Thus two new administrative services were added to the ASF. Both offices were quite small.

Other administrative services were created before the ASF decided to abandon the designation. One was the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps set up to train and assign units of women to assist the Army in its administrative work .38 Another was the Officer Procurement Service set up in November 1942 to handle the recruitment of civilians as specialized officers in the Army.39 Like all other administrative services, both became staff divisions of ASF headquarters after May 1943.

One other word must be added about the special duties of these administrative services. They performed two different types of work. First, they supervised the service commands in rendering various services. This was an internal ASF staff job. They also performed certain services directly for the War Department in Washington and watched over the technical performance of their specialty throughout the entire Army. For example, the Judge Advocate General was the legal adviser of the Army on all matters. The Adjutant General published and distributed official War Department orders. The Chief of Chaplains was the head of all religious activities in the Army. Such was the dual nature of the work of the ASF staff.

General Organization of the Staff

Thus far, two aspects of ASF headquarters have been noted: how G-4 and OUSW were merged and how certain administrative bureaus finally became integral parts of the ASF staff. It is time to take a quick glance at the problem of organizing the ASF staff as a whole. This problem also had two aspects: the recognition of various major duties which the ASF had to perform and the prevention of an undue proliferation of staff units. The reconciliation of these two somewhat opposing objectives was not easy.

The evolution of the office of the commanding general as a part of the staff can be briefly sketched. The ASF organizational planners envisioned the office of the commanding general as being a particular part, but not all, of the staff. It was characterized by the fact that it had a broad point of view covering the ASF as a whole, and that it was peculiarly the per-

sonal staff of General Somervell. The office consisted of General Somervell, his chief of staff, and their immediate aides, who never numbered more than five officers and three or four civilians, plus a mail unit. Originally, there was also a Deputy Chief of Staff for Requirements and Resources, but this office soon evolved into a particular segment of the ASF staff: A new Deputy Chief of Staff for Service Commands was created in May 1943.40

The office of the commanding general also had a number of more highly organized units. The Control Division was set up on 9 March 1942 and functioned throughout the war as an adviser on organizational, procedural, and statistical matters. An administrative office to handle ASF headquarters personnel, space, transportation, and similar matters was abolished and the work assigned to other offices, principally to The Adjutant General.41 A Public Relations Division was abolished when the Secretary of War directed that most of its work be transferred to the War Department Bureau of Public Relations .42 A successor Technical Information Division lasted until the end of 1943. After that General Somervell had only a single officer to assist him on public relations matters. The principal addition to the office of the commanding general was the Director of Plans and Operations in November 1943.43 This action placed a planning unit in General Somervell's immediate office with fairly wide interests covering most ASF activities. But primarily, this office was concerned with overseas supply operations.

The tendency of the functional staff toward reproduction by fission was early revealed. On 21 March 1942 the Personnel Division was split into a Military Personnel Division and a Civilian Personnel Division.44 A possible solution to this kind of expansion was suggested in April when the then Deputy Chief of Staff for Requirements and Resources was -designated to direct three staff divisions.45 This had the effect of combining three staff divisions into one unit, as far as the commanding general was concerned. The idea of a level of supervision intervening between the commanding general and the functional staff divisions was then given general application in July 1942. Three assistant chiefs of staff were set up, one for materiel, one for operations, and one for personnel.46 To each of these assistant chiefs of staff two or more staff divisions were assigned. After 20 July there were sixteen staff divisions in ASF headquarters but only nine staff officers reporting directly to the commanding general.

As new activities came into being, new staff units were created. These new divisions were assigned to the jurisdiction of one of the assistant chiefs of staff. Thus, for example, when the Army Specialized Training Division was set up, it was placed under the Assistant Chief of Staff for Personnel.47

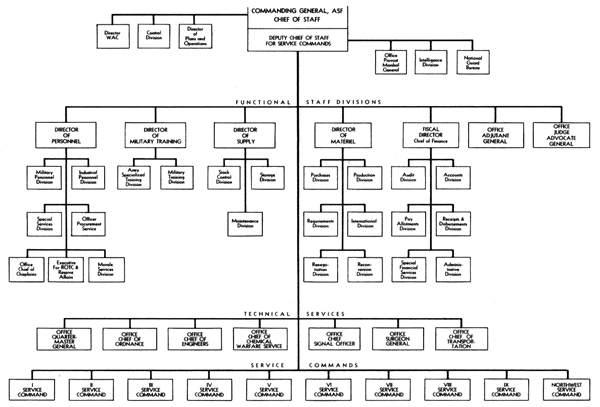

The label "assistant chief of staff "gave way to "director" in May 1943. At the same time, the entire functional staff was placed under six directors: Personnel, Military Training, Operations, Materiel, Fiscal, and Administration .48 (See Chart 5 )

CHART 5 : ORGANIZATION OF THE ARMY SERVICE FORCES: 20 JULY

1943

This was the most symmetrical, the most "orderly" staff organization achieved during the war. It looked "good" on paper. But there is more to organization than just an attractive chart. The creation of the various "directors" worked well in some cases; in the case of the Director of Administration it did not, and the office was abolished in November 1943. The Adjutant General and the Judge Advocate General were positions with too much importance and prestige to be thus subordinated. The staff organization thereafter became more complicated, more extensive. Certain staff units-a new Intelligence Division,49 the Provost Marshal General and the National Guard Bureau-were directed to report to the commanding general through the Deputy Chief of Staff for Service Commands. This was only a partly successful arrangement.

But the staff organization worked out in November 1943 continued with minor modifications until the end of the war .50 New units were added, such as a Personal Affairs Division 51 and a Research and Development Division. The director of the Women's Army Corps was transferred from the office of the commanding general to the Personnel Division (G-1) of the War Department General Staff on 10 February 1944. Immediately after V-E Day, the National Guard Bureau and the Executive for Reserve and ROTC Affairs were transferred from the ASF to the WDGS.52 The Provost Marshal General and the Intelligence Division were ordered to report directly to the commanding general in June 1945.53

By the end of the war ASF headquarters consisted of the office of the commanding general, five staff directors, and four staff units reporting directly to the commanding general. (See Chart 6.) In addition to a Chief of Staff and a Deputy Chief of Staff for Service Commands, the office of the commanding general included a Director of Plans and Operations (requirements and stock control, planning, and mobilization divisions) and a Control Division. The five staff directors were for personnel, military training, materiel, supply and fiscal matters. They had a total of twenty-two staff divisions under them. Reporting separately to the commanding general were The Adjutant General, the Judge Advocate General, the Provost Marshal General, and the Intelligence Division.

This staff organization was not very simple, it didn't look symmetrical on an organization chart. But it had the virtue of expressing the realities of administrative relationships and procedures as they had finally been worked out in ASF headquarters.

The Technical Services as Staff Divisions

Attention thus far has been directed to what the ASF called functional staff divisions. This picture is incomplete without reference to the staff responsibilities vested in the chiefs of the technical services. After the service command reorganization in August 1942 many operating functions previously exercised by the technical services were transferred to the administrative supervision of the service command. The chiefs of the technical services however, retained staff or technical supervision over these activities.

CHART 6 : ORGANIZATION OF THE ARMY SERVICE FORCES : 15 AUGUST 1944

An outstanding example was hospital administration. As already noted, general hospitals were transferred from the direct administrative control of The Surgeon General to that of the commanders of the service commands. This step was not intended to diminish the authority of The Surgeon General in medical matters. Rather, The Surgeon General became the staff officer of the commanding general, ASF, on medical activities at general hospitals. The responsibility for repairs and utilities functions at posts, camps, and stations was transferred from the Chief of Engineers - to service commands. Thereupon the Chief of Engineers became the staff officer for repair and utility functions. The Chief Signal Officer became the staff officer on communications activity within service commands. The Chief of Ordnance supervised automotive maintenance activities. The Chief of Transportation supervised transportation activities at posts, camps, and stations. From time to time the staff responsibilities of the technical services were increased. Whenever it became apparent that an activity fell solely within the jurisdiction of a single technical service, that technical service became the staff agency insofar as service command supervision was concerned. The ASF functional staff confined its interests to programs involving more than one technical service or developed programs for the service commands where there was no technical service interest, as, for example, the induction and separation of military personnel.

This expansion of the role of the technical services as staff divisions can be illustrated by two examples involving The Quartermaster General. Mention has already been made of the Food Service Program in the ASF which brought together the training of mess supervisors, cooks, and bakers; mess management; and the food conservation program. This Food Service Program was operated by each service command. The staff officer in ASF headquarters for this program was The Quartermaster Generals 54 Similarly, in May 1943 the responsibility of The Quartermaster General for the procurement, storage, and distribution of fuels and lubricants was greatly increased .55 The Planning Division in ASF headquarters screened requirements and requisitions for fuel and lubricants from theaters of operations just as it did for all supply questions. The Stock Control Division supervised the arrangements made for distributing fuels and lubricants; the Requirements Division incorporated fuel and lubricant requirements into the Army Supply Program, and the Purchases Division exercised the same supervision over the purchase of fuels and lubricants that it did over the purchase of other commodities. But The Quartermaster General was made "responsible for the performance of all staff functions necessary to the discharge of the operating responsibilities assigned herein." Prior to this time the Production Division, ASF, had included a Petroleum Section whose chief had been the representative of the commanding general on the Army-Navy Petroleum Board. He had handled most petroleum questions. While there were some petroleum activities under the jurisdiction of the Chief of Ordnance and the Chief of Transportation, most of the procurement operations were actually handled by The Quartermaster General. Thus, in effect the ASF had a situation where a staff offi-

cer in the Production Division was directing work done almost exclusively by The Quartermaster General. This arrangement was recognized as faulty and so The Quartermaster General became the staff officer on all petroleum matters. He was designated as the War Department Liaison Officer for Petroleum and was ordered to assign a representative to act as deputy to the commanding general in his capacity as a member of the Army-Navy Petroleum Board. Moreover, The Quartermaster General was given staff supervision over the petroleum activities of the Chief of Ordnance and the Chief of Transportation and for all other parts of the ASF.56 Thereafter, The Quartermaster General, through a Fuels and Lubricants Division, was the staff officer on all petroleum matters. On various matters, then, the chiefs of technical services were drawn into close personal relations with the Commanding General, ASF, and served as staff officers in their special fields.

The creation, abolition, and amalgamation of staff divisions was not the only type of staff adjustment that took place from 1942 to 1945. On occasion a staff responsibility assigned to one unit was transferred to another. For example, in February 1943 supervision of activities pertaining to claims against the government was transferred from the Chief of Finance to the judge Advocate General. 57 This step was taken in an effort to centralize in one office all action on claims matters. Previously the work had been divided between the Chief of Finance and the Judge Advocate General.

From time to time new activities were added to the work of the ASF staff. These were often absorbed within an existing staff division. Sometimes the activity was one which had only been partially recognized in past staff work, as, for example, when experience indicated the need for careful co-ordination of all troop movements. Accordingly, the Movements Branch in the Mobilization Division was designated the "Troop Movement Coordinating Center" for ASF headquarters.58 The branch was directed to develop procedures and policies on troop movements, to issue alert orders to ASF units, to prepare orders for the movement of ASF units, and to report the status of units being moved.

Still another type of staff adjustment was required in handling specific problems. The ASF staff, as already indicated, was a functional staff. On occasion this meant that some particular subject might be of interest to several different staff divisions. Two examples will suffice. A major problem which emerged during 1943 was that of proper packing and packaging of equipment for overseas shipment.59 In an effort to clarify responsibility for proper packaging and packing of supplies, an ASF order assigned staff supervision of packing and packaging at production points to the Director of Materiel, the staff

supervision over packing and packaging at depots and of organization equipment at posts to the Director of Operations, while marking-policy was the responsibility of the War Department Code Marking Committee .60 The Director of Materiel and the Director of Operations were instructed to get together and standardize their policies on packaging. In actual practice, the Director of Materiel assumed the leadership in developing packaging and packing specifications while the Director of Operations, and later the Director of Supply, carried out these policies at depots.

A similar problem which cut across a number of functional fields was that of spare parts. The assurance of an adequate supply of spare parts became increasingly difficult after 1943 as larger quantities of mat6riel came into the hands of troops. Staff responsibility for developing spare parts requirements was assigned to the Requirements Division.61 The Production Division was made responsible for supervising production policies and scheduling spare parts production. The Maintenance Division was made responsible for preparing spare parts lists, for developing policies to determine the basis of issue of these parts, and for supervising their utilization at shops. The Storage Division was responsible for the proper warehousing of spare parts, the Stock Control Division for developing appropriate records on their supply, and the Training Division for the proper training of military personnel in depots and maintenance units in the efficient handling of these items.

These are but a few examples of the constant adjustment that had to be made in staff responsibilities. Since no organization was possible which would entirely prevent overlapping responsibility among staff divisions, the Army Service Forces relied on each staff division to co-operate with other staff divisions whenever they had mutual interests. Where difficulty arose which could not be resolved amicably and directly between the staff divisions, the ASF chief of staff might make some adjustment or the Control Division might be asked to make recommendations.

A case in point was the continual difficulty in drawing a line of demarkation between the Intelligence Division and the Office of the Provost Marshal General on internal security and counterintelligence functions. War Department orders provided that the functions of the Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC) within the zone of interior would become the responsibility of the Commanding General, ASF, effective 1 January 1944.62 The supervision of investigative functions was then vested in the Provost Marshal General.63 At the same time, the Intelligence Division in ASF headquarters looked upon itself as the direct liaison with G-2 on all investigative matters. The Intelligence Division trained CIC personnel for overseas duty while the Provost Marshal General directed the training of personnel for investigative work in the zone of interior. There remained some duplication in the handling of investigation of suspected subversives. Partly because of personality factors, this conflict was not resolved at any time during 1944. Finally, under a circular issued in August 1945, all counterintelligence activities were transferred from the Provost Marshal General to the Director of Intelligence .64 This circular made the

Provost Marshal General responsible for criminal investigations and loyalty checks of civilians employed in industrial establishments having contracts with the War Department. Otherwise, the Director of Intelligence exercised all supervision of investigative activities into military and War Department civilian personnel. The circular pointed out, however, that it was necessary for a high degree of co-operation to continue between the Intelligence Division and the Provost Marshal General's office in handling domestic disturbances.

Organizational adjustments were not always possible as a means of eliminating conflict between staff agencies. Sometimes the only possible answer to conflict was an insistence upon closer co-operation between staff officers. Thus the Director of Mat6riel was responsible for fixing general purchasing policy for the ASF, including control of the provisions of procurement contracts. These contracts necessarily had to conform with general federal statutes governing purchasing operations by the government, had to be enforceable in courts of law, and had to meet the special fiscal requirements surrounding government contracts. This last requirement meant that contracts had to be satisfactory to the General Accounting Office (GAO) so that the disbursements made there under would not subsequently be suspended or even disallowed in the GAO audit.

The ASF Fiscal Director was responsible for financial administration, including supervision of all disbursement operations. To carry out this responsibility, the Fiscal Director was designated as the liaison officer between the ASF and the GAO. The legal adviser to the Director of Mat6riel found that 50 percent of his time was involved in negotiating various questions with the Fiscal Law and Regulations Branch in the Office of the Fiscal Director. Yet the Fiscal Director insisted that only his officers should discuss any questions with the GAO. The legal assistant to the Director of Materiel felt that this' insistence prevented him from explaining purchasing problems to the General Accounting Office and strongly expressed the belief that many rulings of the GAO might have been different if that office had been given a clearer understanding of the procurement problems confronting the War Department. The legal assistant accordingly wanted the authority to negotiate with the GAO transferred from the Fiscal Director to the Director of Materiel. The only solution to this type of conflict was closer working relationships within the staff. For example, in the instance cited, the merits of both sides should have been acknowledged. A great many of the questions arising between the Fiscal Director and the GAO dealt with details of governmental accounting or other issues not involving procurement contracts. At the same time, the special interest of the Director of Mat6riel in contracting arrangements should have been acknowledged by the Fiscal Director.

Enough has been said here to indicate the types of inter-staff issues which arose during the war. There was a continuing need for co-ordinating the work of the staff and for settling conflicts. In short, organizational problems did not end when new organization charts were drawn and issued.

From the beginning the ASF referred to its staff as a functional staff. The customary staff designations in the Army-G-1, G-2, G-3, and G-4-were never em-

ployed. In fact, the labels Assistant Chief of Staff for Materiel, Assistant Chief of Staff for Personnel, and Assistant Chief of Staff for Operations gave way, as already indicated, to the designation of Director of Materiel, Director of Personnel, and Director of Operations. The commanding General wanted a staff on functional lines in order to avoid the old conflict between the duties of a "general" and a "special" staff. The designations were changed also to avoid confusion with the War Department General Staff and to emphasize that staff officers were expected to perform the responsibilities assigned to them and not simply to co-ordinate other staff officers. For example, any past tradition that a G-1 was a planning agency and a means of co-ordinating other staff officers was broken by designating the personnel officer in the ASF as Director of Personnel, and by placing other units directly and fully under his responsibility. Thus, the Chief of Chaplains and the Executive for Reserve and ROTC Affairs were also under the Director of Personnel.

The staff was functional in another sense. It was concerned with those major purposes which the operating units-the technical services and the service commands-shared in common. Thus in the procurement and storage field, although operating responsibilities were divided by the type of commodity purchased, the functional staff was concerned with those activities common to all procurement operations. The Director of Materiel was concerned with pricing policy regardless of the type of commodity procured. The ASF developed standard procurement contracts as a means of preventing competition between the technical services in offering attractive contract provisions to suppliers. Standard contracts also meant that any company having contracts with several different procuring agencies of the War Department could be sure that all its contracts contained the same provisions on such matters as contract termination, price readjustment, and legal liabilities.

The Storage Division well illustrated the need for a central co-ordinating staff. Each technical service operated its own warehouses and other storage facilities. Each determined its own special storage needs. The job of the Storage Division as a staff agency was to see that all followed the most modern warehousing practices, that storage facilities were located in close proximity to the places where supplies were needed, and that unnecessary facilities were not built. In fact, there were frequent shifts of storage space from one service to another to meet peak loads or other special needs. Without such a staff agency many more storage facilities would probably have been constructed by the technical services.

To perform administrative services, the ASF was set up organizationally along geographical lines, by service commands. Thus there was a need for functional staff units to insure that various activities were performed in a uniform manner by all service commands.

Admittedly the ASF functional staff was large. On 31 July 1943 it numbered 45,186 military and civilian personnel, not including the technical services.65 On 31 August 1945 its strength had dropped to 34,138 military and civilian personnel. Of this total strength, 16,305 were located in ASF headquarters and the remainder were outside of Washington. The division

of this strength among the various parts of the staff was as follows: 66

| Office of the Commanding General | 723 |

| Director of Personnel | 2,675 |

| Director of Military Training | 205 |

| Director of Supply | 523 |

| Director of Materiel | 913 |

| Director of Intelligence | 136 |

| judge Advocate General | 815 |

| Provost Marshal General | 856 |

| Fiscal Director | 14,718 |

| Adjutant General | 12,574 |

| 34,138 |

Of the 16,000 personnel in Washington, over 9,000 were in the Office of The Adjutant General. This included personnel operating reproduction facilities, running the mail center, maintaining central records, and providing other services for the entire War Department.

More than half of the ASF staff, it will be noted, was located outside the District of Columbia. This in itself might seem odd. The ASF at one time hoped that all the work done outside Washington would come under the direct control of either a service command or a technical service. Actually this did not prove feasible. Of the 17,500 staff personnel located outside the District of Columbia on 31 August 1945, 12,466 were in the Office of Dependency Benefits located in Newark and in four regional accounting offices, all under the Fiscal Director. When the Office of Dependency Benefits was established in Newark, it was decided that it would be preferable administratively to keep it under the control of a staff officer in Washington. The four regional accounting offices handled work which had previously been centralized in Washington.

There were other situations where field offices continued under staff control. In a sense, these were not field offices but rather branch offices located outside of

Washington in order to prevent the concentration of all staff work in the Capital. Thus, the Special Services Division kept only a small group in Washington and had its main offices in New York City directing the activity of the post exchanges and the athletic and recreation program. The Information and Education Division had a publishing office in New York City as the central headquarters for rank and for distributing releases to post and division newspapers throughout the Army. The correspondence school for the Army had its office in Madison, Wisconsin; the Armed Forces Radio Service had its principal offices in Los Angeles and New York. These were branch offices of the Information and Education Division. Where some large central service had to be performed for the War Department as a whole, the ASF followed the practice of having the staff division retain control over the branch offices outside Washington.

It defined "pure staff activities" as advising the commanding general in its field of responsibility; formulating plans, poli-

cies, and procedures for the performance of a function throughout the ASF; advising and assisting subordinate operating units; and following-up on performance to insure that policies, plans, and procedures were carried out as specified. In essence this meant that staff work was planning and supervising. The manual emphasized the point that staff agencies did not perform a job. Rather, the staff divisions were to state the objectives and establish policies to guide performance and then to follow up in order to determine that performance met these objectives and policies.

The manual's mention of "activities performed for headquarters" referred to another type of duty necessarily performed by the staff divisions of the ASE Actually, some offices had to render a central service for the War Department, and since the ASF was a central service these offices were lodged in it. Thus the publications work of The Adjutant General's office was in reality a large operating job. But the work was also a central service rendered for the War Department. As far as the distribution of publications in the field was concerned, The Adjutant General's was a "pure staff" agency, since the distribution depots were under the command of service commands. The central legal service rendered by the judge Advocate General was another illustration of a central War Department service performed by an ASF staff division. The Transportation Corps also operated a central transportation service for ASF personnel and one for War Department personnel stationed in Washington as well. The Military Personnel Division of ASF handled the personnel problems of ASF headquarters. In short, several ASF staff divisions and technical services provided a central service, either for the War Department or for ASF headquarters, which was functionally related to the staff responsibility of that agency. As has already been explained staff divisions also exercised direct control over a number of field agencies.

The most important single aspect of the staff concept of the ASF was simply this: staff agencies planned and supervised. For example, the Readjustment Division outlined the major policies and procedures to be followed in settling terminated contracts, but the actual conduct of the negotiations to reach an agreement with a contractor remained in the hands of the technical services. The Readjustment Division then kept records to determine how well each technical service was performing its responsibility and checked up from time to time to make sure that the work was going satisfactorily and that obstacles were being overcome. This same arrangement was true in every functional field.

There were occasions when staff divisions tried to argue that they could only advise and suggest, that they could not be held responsible for results. General Somervell refused to accept this point of view. A staff division was expected to insure that results were obtained by the operational agencies of the ASK Staff officers and chiefs of the technical services or commanding generals of service commands were held equally responsible for getting the job of the ASF done.

Finally, one other aspect of the ASF staff should be noted. Even after the originally designated administrative services had been absorbed into the ASF staff, for reasons of convenience they were still often referred to as administrative services. This was primarily true of those parts of

the ASF staff whose head was also the chief of a branch of a service in the Army. The Adjutant General was head of The Adjutant General's Department, the Judge Advocate General the head of the judge Advocate General's Department, the Chief of Chaplains head of the Corps of Chaplains, the Chief of Finance head of the Finance Department, and the Provost Marshal General was head of the Corps of Military Police. Each of these were branches of the military service with personnel assigned to various commands of the Army throughout the world. For this reason it was convenient to continue to refer to their offices as administrative services, since their heads were responsible for the development of technical standards and procedures to be observed in the Army as a whole.

This, then, was the ASF staff, a large organization required to insure that appropriate service was given the Army. The supply problem itself was indivisible. Units in the United States and overseas commands were not considered properly supplied unless they had all of their ordnance equipment, their quartermaster equipment, their signal equipment, and their medical supplies. It took a great amount of work to insure balance in procurement programs, to maintain satisfactory distribution procedures in all technical services, and to keep the right types of supplies flowing out of ports of embarkation to overseas commands. Administration of a military post was geographically indivisible, but again it took a great amount of work to insure that posts inducted military personnel, ran their hospitals, stored and issued supplies, provided recreational facilities, and performed all their housekeeping duties proficiently. The ASF staff was always busy.