CHAPTER XVI

The Caribbean in Wartime

The Panama and Caribbean defenses felt the initial impact of war chiefly in the shape of repercussions from Washington. At least two fields of activity were affected, namely, the problem of command and the matter of reinforcing the garrisons. The entry of the United States into the war radically and immediately altered the situation in each of these fields.

As a result of the attack on Pearl Harbor, the vexing problem of who should command when the forces of two or more services were involved was, as far as it concerned the North Atlantic bases, pushed farther away from a solution; but, as far as the Caribbean-Panama area was concerned, the problem was disposed of immediately. The only difficulty that remained was to make the solution work. On this general subject Secretary Stimson's biographer has observed: "The attack at Pearl Harbor emphasized again the importance of unity of command; all the armed forces in any area must have a single commander. Stimson was ashamed that the lesson had to be so painfully learned; for months he had read it in the experience of the British in North Africa, Crete, and Greece. Incautiously he had assumed that it was equally well learned by others . . . ." 1 As late as 5 December the Army-Navy Joint Planning Committee had been struggling with the task of formulating a statement of general policy governing the application of unity of command. No agreement had been reached by the time the attack on Pearl Harbor occurred. Then, out of the flood of rumors and alarms that followed the Japanese onslaught came a report that two hostile aircraft carriers had been sighted off the west coast of Mexico. General Andrews was immediately instructed to "take all necessary precautions in reconnaissance" and to notify the naval commander. In Washington, GHQ, learning that Navy patrol

[409]

planes based on Coco Solo were part of a task force under the commander in chief of the Atlantic Fleet, raised the question of command, but on being referred to General Andrews in Panama the question became one of liaison rather than command.2

On Friday, 12 December, five days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Secretary Stimson was amazed to find that no scheme for establishing unity of command in Panama had been worked out. Aroused by the thought that the canal would probably be one of the next objectives of the Japanese, he had General Marshall draw up a proposed directive placing all Army and Navy forces in the Panama Coastal Frontier, except fleet units, under Army command, and later in the day Mr. Stimson laid the proposal before the Cabinet.3 The President approved the idea by taking a map, writing "Army" over the area of the Panama Coastal Frontier, but at the same time writing "Navy" over the Caribbean Coastal Frontier, and then adding his "O.K.-F.D.R." As presented by Secretary Stimson, the draft proposal had said nothing about the command of the Caribbean area except that "the Commanding General, Caribbean Defense Command, within his means and other responsibilities, will support the Naval Commander of the Caribbean Coastal Frontier." During the afternoon General Gerow discussed the Panama command with Admiral Stark, without referring to the Caribbean, and after the Cabinet meeting he took the papers that had been approved by the President to a conference with Admirals Stark and King, and Rear Adm. Richmond Kelly Turner. Admiral King, Commander in Chief, Atlantic Fleet, and soon to become Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet, thought Secretary Stimson's proposal might possibly be a practical solution, but Admiral Turner,- head of the Navy War Plans Division, was opposed. His view was that unity of command was appropriate only for regularly organized task force operations, that once established it ought not to shift back and forth according to which service had "paramount interest," and that for general defensive operations the appropriate method of co-ordination was mutual co-operation, not unity of command.4 But the President's intent with respect to Panama

[410]

was clear, and at a meeting of the joint Board held the next day Admiral Stark accepted the decision to establish unity of command under the Army. A major consideration was the view that "unless unified control was affected [effected?] by joint agreement between the Army and the Navy, the establishment of a department of National Defense, appointed by the Administration, might be considered a certainty." 5

Over the weekend, the Navy War Plans Division prepared a written statement on the subject, which Admiral Stark forwarded to General Marshall on Monday, 15 December, and which brought into the discussion the question of command in the Caribbean. The Navy's position was that the President's notation on the map of the Caribbean Coastal Frontier indicated that he intended unity of command to be established under the Navy in that area, as in Panama under the Army. This was what the Navy had proposed almost a year before. The Army countered with the same argument that had brought on the previous stalemate: that it was impossible to consider the Army defenses of the Panama-Caribbean area except as a unit and that, if unity of command were necessary in the Caribbean, it should, as in Panama, be under the Army. When the question came up for discussion at a further meeting of the joint Board, on 17 December, the only agreement was that efforts to reach one would be continued. But the same consideration that helped to bring the Army and Navy into agreement on the Panama command doubtless played a similar part with respect to the Caribbean. In any event, on the morning of 18 December, General Marshall instructed the War Plans Division that in the Caribbean the Navy would exercise unity of command. Thus, within a week after Secretary Stimson became aware of the serious situation the question of who should command was solved.6

In two or three days more, all the details of the directives to be issued were likewise settled. In order to allay any possible uneasiness on the part of the naval commander at Panama, General Marshall had first proposed a list of special restrictions and exceptions that would have limited the Army's exercise of command, but they were soon laid aside, at Admiral Stark's suggestion, in favor of a simple, more easily interpreted directive modeled on the one that had been adopted for Hawaii. All forces "assigned for operations" in the respective coastal frontiers came within the scope of the

[411]

orders, which were limited only by the provisions of Joint Action of the Army and the Navy.7 The urgency of the situation had prevented the War Department from consulting General Andrews. Now the success of the decision rested on his good judgment. He promised to do his best. The decision presented him with a difficult problem of organization; but barring an immediate interruption in the shape of a serious threat to the Caribbean, the plan, he believed, could be made to work.8

While the War Plans Division, General Marshall, and Secretary Stimson had been occupied chiefly with the question of command, GHQ and General Andrews had been more concerned with reinforcing and strengthening the Caribbean garrisons. By directing the various commanders to put the RAINBOW 5 war plan into effect, the War Department brought on a veritable barrage of requests for reinforcements, since the deployment of forces provided in RAINBOW 5 was incomplete. Because the Canal seemed to be one of the objectives of the Japanese war makers, General Andrews' requests fared better than most. On 12 December GHQ noted that two infantry regiments, two barrage balloon units, one field artillery battalion, and two hospital units were to be sent to Panama in addition to some 1,800 coast artillery filler replacements. A few days later, arrangements were made to send the 53d Pursuit Group to reinforce the air garrison. Negotiations were started to acquire 72 40-mm. antiaircraft guns from the British and to dispatch one heavy bomber squadron and one flight of pursuit planes to Talara.9 The December 1941 reinforcements, both ground and air, were more than double those in the entire first eleven months of the year. By the end of December the Panama garrison had risen to about 39,000 men; and at the end of January it had reached 47,600.

Puerto Rico, unlike Panama, appeared to lie beyond reach of the Japanese. In common with all the Atlantic bases similarly situated, Puerto Rico felt the immediate effect of the Pearl Harbor attack as a temporary disruption of its defense build-up. The War Department gave careful scrutiny to requests for reinforcements submitted before the Japanese assault, and in December less than 200 men were added to the Puerto Rican garrison. The same rate of increase was maintained during the next two months, so

[412]

that the total strength, which at the end of November 1941 had amounted to about 21,200 men, had risen to only 22,000 at the end of February 1942.10

The naval forces available for purposes of local defense were, like the Army garrison, concentrated in the Panama area, where Rear Adm. F. H. Sadler, Commander Panama Naval Coastal Frontier, had at his disposal a small and motley force of patrol planes, submarines, and subchasers. For "heavy" units, Admiral Sadler had two old destroyers and a gunboat, and the rest of his command consisted of 6 submarines, 3 converted yachts, 5 subchasers, 1 mine sweeper, and 12 patrol planes with their tender. Even before General Andrews was given over-all command, his superior responsibility had been informally acknowledged by Admiral Sadler, who considered himself somewhat as a task force commander under General Andrews as well as a task group commander under the Commander in chief, U. S. Atlantic Fleet.11 In the Caribbean, Rear Admiral J. H. Hoover's naval forces were divided between a patrol force consisting of two old destroyers, three small submarines, two subchasers of World War I vintage, and twelve patrol planes, and smaller local surface forces at Guantanamo and Trinidad. The latter were virtually undefended; at Trinidad on 7 December 1941 there were only two converted yachts, two "Yippies" (district patrol craft, YP-63 and YP-64) and four of Admiral Hoover's patrol planes.12 As in the case of the Army, the Navy's first reaction was to strengthen the defenses at the Pacific end of the Canal. On 14 December the War Department learned that the Navy had sent two submarine divisions (8-12 vessels) and a patrol squadron of twelve planes to Panama with orders to establish advanced patrol bases in the Galapagos Islands and Gulf of Fonseca.13

Somewhat better progress had been made in operational planning under RAINBOW 5 than in the deployment of troops. In October 1941 a group of General Andrews' staff officers headed by Brig. Gen. Harry C. Ingles, G-3 of the Caribbean Defense Command, arrived in Washington to prepare an operations plan for the Caribbean theater. A draft had been made ready

[413]

by GHQ on the model of the Iceland plan prepared a few months earlier. When General Ingles and his group returned to Panama on 31 October, the current estimate of the situation and the intelligence plan prepared by GHQ had been brought into agreement with the views of the Caribbean Defense Command. The rest of the work was to be done in Panama and to be submitted to GHQ for approval. By the date of the Pearl Harbor attack the operations plan itself, the basic document, had been completed, but not all the seventeen annexes were finished.

Based as it was on the RAINBOW 5 war plan, the Caribbean operations plan faced toward the Atlantic and anticipated a war in which Germany and Italy would be the major opponents, the Atlantic and Europe the principal battleground, and the Caribbean relatively immune to attack. It contemplated a garrison of a little more than 112,000 men for the Caribbean theater. Considering the fact that the actual deployment of forces in November 1941 was based on the possibility of a carrier raid against the canal from the Pacific, that the total garrison of the Caribbean Defense Command amounted to less than 60,000 men at the end of November, and that the establishment of separate unified commands in Panama and the Caribbean created a different scheme of organization from that envisaged by GHQ, there might have been some question of the practicality of the operations plan.14 As it turned out, the canal itself was never seriously threatened from either side, nor were the outposts, except for Aruba and Curacao, ever fired upon. Nevertheless, the Caribbean Defense Command garrison was built up to a peak of 119,000 men in December 1942. More than half of them were in Panama guarding the canal from attack or sabotage.

Provisions for armed assistance to recognized governments of the Latin American republics and for the protective occupation of colonies belonging to European powers were a feature of the RAINBOW 5 war plan; but these provisions were specifically excepted when the plan was ordered into effect after the attack on Pearl Harbor.15 The Dutch islands of Aruba and Curacao were then the principal focus of attention, but, before American troops could be sent to the islands, the approval of the Netherlands Government was desirable, arrangements with the local authorities for the arrival of the troops were necessary, and provision for the departure of the British had to be made. All this took time. It was not until the end of January that these

[414]

preliminary details were finally disposed of. On 26 January 1942 the War Department informed General Andrews that the Netherlands Government had agreed to entrust the defense of the islands to American troops. Two days later, Col. Peter C. Bullard, commanding officer of the designated forces, and his staff, arrived at Curacao to make the necessary arrangements for the landing. Had it not been for some dissatisfaction on the part of the Dutch over command arrangements in the Far East and their unwillingness to permit Venezuelan participation in the defense of Aruba and Curacao, and for some reluctance on the part of the United States Government to press the issue until after the Rio de Janeiro Conference of Foreign Ministers, faster progress might have been made.16

Meanwhile, in mid-January six A-20 light bombers were stationed, with the permission of the Netherlands Government, on the two islands. Some question had arisen whether the islands were within the Panama Coastal Frontier and thus under General Andrews' jurisdiction or within the Caribbean Coastal Frontier and under Admiral Hoover. The 1940 joint Army and Navy plan for the defense of the Panama Canal had included both Aruba and Curacao in the Panama Coastal Frontier; but the boundaries established by the RAINBOW 5 plan, under which General Andrews was now operating, clearly placed them within the limits of the Caribbean Coastal Frontier.17 Both Admiral Hoover and General Andrews, without informing each other, made arrangements to send planes to the islands. An embarrassing situation was averted only by a narrow margin when an information copy of an order of Admiral Hoover was received by the Puerto Rican Department and forwarded by it to General Andrews' headquarters.18

The ground troops, to the number of about 2,300 men, sailed from New Orleans for Aruba and Curacao on 6 February and arrived at the islands on 11 February. The British garrison, about 1,400 strong, departed three days later. Before the American forces had their guns and searchlights ready, the enemy struck and won, as at Pearl Harbor, an initial victory.

[415]

The dispatch of American troops to Aruba, Curacao, and Surinam, and the entry of the United States into the war as an associate of Great Britain and the Netherlands, raised a problem of command relationships not only between the Army and the Navy, but also between the United States and its allies. A unique feature of the situation in the Caribbean was the fact that the over-all command was strictly unilateral, while several of the subsidiary commands were combined commands. In Trinidad and in Jamaica an Anglo American headquarters was set up; in Aruba and Curacao there was a combined Dutch-American headquarters.

Conversations between representatives of the War Department and members of the British Military Mission in Washington had been held during the late spring and early summer of 1941 on the subject of co-ordinating local defense measures in the British colonies where the new United States bases were located. Because the United States was not a belligerent, this subject had not been included in the base agreement of March 1941, but the dispatch of American garrisons during the ensuing months seemed to make some arrangement essential.19 There were a number of complicating factors, among them the special relationship between the colonial Governors and the military forces of the colony, the matter of offshore air and naval patrols, and the question of who should command. The authority of the colonial Governors was clarified by a British statement, later incorporated into the final agreement, to the effect that, although bearing the title of commander in chief, the Governor was not vested with command authority except on special appointment from the King, and thus he was not entitled to take the immediate direction of military operations.20 Agreement on the remaining points was soon reached, and the whole signed in final form on 30 August 1941.21

On the salient point, it was agreed that unity of command of the forces of both powers would be established either on instructions from the two governments in the event of an attack on the territory, or as soon as the "Associated Powers" became "mutually associated in a war against a common enemy." The nationality of the officer exercising unity of command would be determined generally by the strengths of the forces involved and

[416]

the tactical or strategic importance to the respective powers of the locality concerned. Specifically it was agreed that the American commander at Bermuda, Jamaica, Antigua, St. Lucia, Trinidad, and British Guiana would exercise command over the combined forces, subject to a review of the situation at any time at the request of either government.22

Co-ordination was provided for through the medium of a Local Combined Defense Committee to consist of the colonial Governor, as chairman and convening authority, the senior officers of the American and British military and naval forces, and whatever other local authorities might be necessary as advisers. The actual preparation of a co-ordinated local- defense plan for all the combatant services--American and British was to be the task of a Local Joint Military Defense Subcommittee, presided over by the commander of the Combined Local Defense - Forces, i.e., the commander of the American forces. The several military defense plans prepared by the subcommittee and the civil defense plans prepared by the colonial authorities were to be co-ordinated into a combined defense plan by the Local Combined Defense Committee.23

The agreement was approved by the joint Board on 19 September. After minor revisions were made it was approved by the Secretaries of War and Navy and sent to the President on 1 December. When the attack on Pearl Harbor brought the United States into the war, President Roosevelt, on 12 December 1941, gave his approval to the agreement.24

Meanwhile, in Trinidad the co-ordination of local defense measures had been informally explored in conversations between the British commander, Brigadier J. F. Barrington, and representatives of General Talbot's planning staff. The Governor, Sir Hubert Young, wished to bring the discussions into the framework of existing machinery and suggested several times that a U.S. Army representative be appointed to the local defense committee through which he, as Governor, exercised his responsibility for the defense of the colony. To General Talbot these proposals seemed to involve a surrender of authority on his part, which he was unable to accept; as a result there was no formal co-ordination of defense plans until after the United States entered the war. 25

[417]

On 16 December Governor Young received a telegram from the Colonial Office informing him of the agreement that President Roosevelt had approved four days earlier. In accordance with the provisions of the agreement the Governor called a meeting of the Local Combined Defense Committee on 20 December, for the purpose of discussing the scale of attack for which preparations would have to be made and of deciding upon the composition of the two committees. A second meeting was held on 3 January. As for the scale of attack, it was generally agreed that the only thing to do was "to guard against the possibilities outlined by higher authority with the forces available," and that if the turn of events increased the possibilities "higher, authority would decide whether or not to make further provision against them.26 As for the composition of the Local Combined Defense Committee, it was decided that the colonial secretary and the American consul should be members, in addition to the Governor and the military and naval commanders as provided in the basic agreement. The Local Joint Military Defense Subcommittee was to consist of General Talbot, chairman, the British military and naval commanders, the commandant of the United States Naval Base, and a representative of the Caribbean Air Force (USAAC). The question arose during the first meeting whether the Combined Defense Committee or the joint Military Defense Subcommittee should prepare the initial draft of the co-ordinated military-civil defense plan. There was general agreement that the actual drafting should be done by the military subcommittee, that the plan should then be submitted to the Combined Defense Committee for approval, and that any points of difference arising in the military subcommittee should be referred to the Combined Defense Committee for resolution. On this last point the instructions received by General Talbot and Governor Young were perhaps none too clear. The intent, as General Andrews who was then in Trinidad pointed out, had apparently been to have a joint advisory board to which both the Combined Defense Committee and the military subcommittee would submit any differences; but General Talbot and Governor Young both agreed that any differences of opinion arising in the joint Military Defense Committee would be submitted to the Combined Defense Committee before they were referred to higher British and United States authorities.27 With these organizational preliminaries out of the way, the business of preparing

[418]

the various joint plans-port security, air raids precaution, medical, censorship, antiaircraft defense, et cetera---was parceled out to the appropriate authorities. To General Talbot was allocated the responsibility for planning the machinery by which operational intelligence and military facilities could be mutually exchanged between the two powers.

Although the measure of co-operation between the American forces and the government of the colony in the month following the attack on Pearl Harbor was high, the previous difficulties had left a permanent scar. General Andrews, during his visit in Trinidad, had been much concerned about the situation and had come to the conclusion that it required an officer of higher rank and more diplomatic experience than General Talbot.28 But all the rank of the Archangel Michael and the wisdom of Solomon would have been of no avail to the American commander without a will to co-operate on the part of the Governor. Whether the fact of association with Great Britain in the war would have produced complete co-operation in Trinidad was not really put to test, for it was decided to make a fresh start. Early in January 1942 Maj. Gen. Henry C. Pratt assumed command of the Trinidad Base Command, and not long afterwards a change of Governors took place. By the beginning of April, when Under Secretary of War Patterson made an inspection trip to the Caribbean, the atmosphere was noticeably clearer.29

Most of the machinery of collaboration set up in the weeks immediately after the entry of the United States into the war was working full blast by the first of June. The first joint defense plans had been turned out. A Joint Operations Center, the kingpin of the system, had been organized. In effect the joint Operations Center was the command post of the commander of the Combined Local Defense Forces, the instrument by which his orders were transmitted to the subordinate commands. Through control officers representing the Army, the Air Force, and the Navy, he exercised operational control and maintained liaison with the headquarters of the British forces.30

The only British island, other than Trinidad, that had any sizable local defense forces was Jamaica, where a Canadian infantry battalion had been on guard since early in the war. The American garrison was outnumbered, and its commander outranked, and for this reason it had been decided in January 1942 that the brigadier commanding the Canadian and British troops should exercise command over the Combined Local Defense Forces "until such time as the strength and composition of the United States gar-

[419]

rison . . . warranted the assumption of command by an appropriate United States Army officer." 31 The arrangement satisfied neither Admiral Hoover nor the American commander in Jamaica. By October 1942 reinforcements had raised the strength of the American garrison to a level that was perhaps slightly higher than that of the British and Canadian forces, and to Admiral Hoover it seemed time to raise the question of command. He had received a report from Col. Earl C. Ewert, the local American commander, which related difficulties in organizing combined field exercises, and which expressed a fear that the British were proposing to place the local police and the volunteer militia in the same category as regular troops. This would more than double the actual British-Canadian forces. Colonel Ewert further reported that there was a plan on foot to raise the rank of the British commander to that of major general. Colonel Ewert's and Admiral Hoover's concern about the command situation in Jamaica was not shared by the War Department, whose position was that the original circumstances had not changed sufficiently to warrant a change in command. The Navy Department agreed that a change was undesirable at this particular time in view of the possibility of labor disturbances on the island.32 Admiral Hoover, although not persuaded that a shift of command was unwarranted, concurred in the view that it would be impolitic to make one just then.33 The United States had now been at war a full year, and the American garrisons in the Caribbean were at their peak strength. After December 1942 the contraction began. It was at first almost imperceptible, and in fact a few of the smaller garrisons, including the one at Jamaica, were increased slightly in the early months of 1943; but by June 1943 the reduction of the Jamaica garrison was well under way. The command arrangements continued unchanged until the end of the war.

The formula by which the question of command in the British colonies had been decided, namely, the relative strength of the respective forces and the strategic importance of the place, was not similarly employed in the initial negotiations with the Netherlands Government over the defense of Aruba and Curacao. That it could be used and would operate to give command of the combined defense forces to the United States was no doubt the reason why the Netherlands Government wished to set the number and com-

[420]

position of the American garrison. In transmitting his government's formal request that an American garrison be sent, the Netherlands Minister had written to Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles that "the number and the composition of the necessary troops will be communicated by the Netherlands Government in due course," and he had further pointed out that "the British troops [who were being relieved by the Americans] were present in the islands as an allied force, the costs of which were borne by the British authorities while they were placed under the command of the Dutch military commander in Curacao acting under the supreme command of the Governor . . . ." The Netherlands Government, he concluded, presumed that the same arrangement would be kept with respect to the American forces.34 The only point to which the American Government took exception was that concerning the size and composition of the force. Decision in this regard was considered to be a matter for determination by consultation between the two governments and not by the Netherlands Government alone.35 The American forces that landed in Aruba and Curacao on ii February 1942 were not, however, placed under the Dutch military commander. Colonel Bullard's instructions were merely to co-operate closely with the Governor and to act under his general supervision, provided he could do so without jeopardizing the success of his mission. Then came the U-boat assault against Aruba and the tanker route from Maracaibo. Unity of command under an officer of the United States Navy was one of the first measures that Admiral Hoover suggested after the attack, but his suggestion ran afoul of General Andrews' insistence that command be vested in an Army officer.36 At the same time the State Department began pressing the Netherlands Government for unified command of all Dutch and American forces under an American officer. Agreement on the matter was finally reached at the end of March when the Netherlands Government accepted Rear Adm. Jesse B. Oldendorf, USN, as supreme commander of all forces in the Aruba-Curacao area. Admiral Oldendorf, who had been placed in command of all American forces in the area earlier in the month, now organized a joint staff with Captain Van Asbeck, the local Dutch commander, as his chief of staff. For purposes of operations the Dutch forces would be commanded by their own officers, under Admiral Oldendorf, who was in

[421]

turn under Admiral Hoover, commander of the Caribbean Sea Frontier. The constitutional position of the Dutch colonial Governor was recognized and nominally upheld by considering Admiral Oldendorf's orders as being given under the authority of the Governor.37 Once established, the command arrangements in Aruba and Curacao appear to have been satisfactory to all concerned. They were maintained, apparently without friction, for the duration of the war.38

In Surinam, the Dutch colony on the South American mainland, where American troops had arrived early in December 1941, no arrangement for combining all forces under one command was made. When General Talbot, immediately after the troops arrived, directed the commanding officer to assume command of all forces in the colony, the Governor, who had taken a dim view of the proceedings from the very start, was unreservedly and justifiably indignant. General Andrews and the War Department moved quickly and almost simultaneously to countermand the order.39 The incident seemed to point to the need for an agreement on the subject, and on 22 December Secretary Stimson asked the State Department to negotiate one by which unity of command over all forces in Surinam would be vested in the senior U.S. Army officer present. But discussions with the Government of the Netherlands over the question of sending troops to Aruba and Curacao were now in full swing, and until an agreement on this score was reached it appeared desirable to postpone the question of command in Surinam. As soon as the American forces had landed in Aruba and Curacao, Secretary Stimson again brought up the question of command.40 The ensuing negotiations resulted only in the agreement respecting the two islands.

In Surinam the relationship between the Dutch and American forces continued to rest on "mutual cooperation." The local colonial forces, which were the principal element in the command problem, played, for the most part, a very minor role in the war. Their opportunity would have come had the enemy attempted to land or perhaps attack by air; but nothing of this sort took place.

[422]

The battle of the Caribbean, heralded by the attack at Aruba, took the form of a sustained and extremely damaging U-boat assault against shipping. Its first victims were five tankers -four of them British ships and the other a Venezuelan- that were torpedoed and sunk during the early morning hours of 16 February 1942. Insult was added by the fact that two of the ships were sent down while lying at anchor in San Nicolas harbor, Aruba, by a U-boat that entered the anchorage, sank the two tankers, then came boldly to the surface and lobbed a few shells at the Lago oil refinery. Fifteen or twenty minutes after the attack, a guard at the airfield, about ten miles away, reported that a fire had broken out at the refinery, and the air commander immediately placed his unit on the alert. Ten minutes later a plane was sent up to reconnoiter. It reported ships on fire in the harbor and oil burning on the water, although nothing about gunfire or submarines. Shortly afterwards, the airfield received a request for an air patrol over the refinery area until daylight; but still no indication was given that hostile action had taken place or might be impending. An hour and a half after the attack the first report of U-boat activity reached the commander of the air unit. An antisubmarine patrol was instituted at once. While the planes were investigating a questionable contact forty-five miles off the island, an American tanker that was tied up at the Eagle refinery dock, only four miles from the airfield, was torpedoed and severely damaged. Reinforcements amounting to six additional planes soon arrived from Puerto Rico and Trinidad, and patrols were extended to cover the tanker route between Aruba and Maracaibo. During the next two days at least seven U-boats were reported sighted in the vicinity, one of them not more than four hundred yards off the airfield. Five of them, according to the air unit's reports, were attacked by the planes; but without radar, with crews untrained in antisubmarine warfare, and armed only with 300-lb. demolition bombs, the planes had little luck against the wily U-boats. Possibly the mere presence of the planes forced the submarines to a more cautious approach than they would otherwise have made, for General Andrews, who was making an inspection tour of the Caribbean and happened to be in Aruba during the attack, wrote to General Marshall that "it was fortunate that we had airplanes there, otherwise the oil plants would have been in for a good shelling." 41

Actually only three U-boats were responsible for all the havoc, and a

[423]

prematurely exploding shell in the deck gun of U-156, which seriously wounded two of the crew and forced the raider to retire, was of greater good fortune to the oil refineries of Aruba than the presence of American planes. When one of the other U-boats attempted to shell the oil installations the following night, Aruba was completely blacked out. This and the air and surface patrols during the day made further shelling of land targets impossible. Two attempts on the part of the third U-boat to shell Curacao were frustrated by naval patrol vessels. The primary object, however, was to destroy shipping, and in this the operation was an unqualified success. Reinforced during the next two or three days by the arrival of two more U-boats, the German raiders sank 21 ships totaling about 103,000 tons in the space of two weeks. Losses to the shallow-draft Maracaibo tanker fleet seriously cut the oil production of the huge refineries on Aruba and Curacao. The onslaught reached a new peak in May, when eight U-boats sank 35 ships totaling more than 145,000 tons in the Caribbean Sea Frontier west of the shipping control line. In June there were 14 undersea raiders operating in the entire Caribbean Sea Frontier and the adjacent waters of the Gulf and Panama Sea Frontiers. By the middle of the month, 22 percent of the bauxite fleet had been destroyed, 20 percent of the ships in the Puerto Rican run had been lost, and of 74 vessels allocated to the Army for the month of July, 17 had already been sunk. By the end of the year 1942 the enemy had sunk in the Caribbean, in the Atlantic sector of the Panama Sea Frontier, and in the nearby fringes of the Gulf Sea Frontier, a total of 270 vessels, comprising more than 1,200,000 tons of shipping.42

Although General Andrews recognized the U-boat campaign as "a definite menace to our war effort," he considered the canal to be "the one real enemy objective" and its protection to be his "paramount mission." Although he was somewhat concerned about the possibility of German surface

[424]

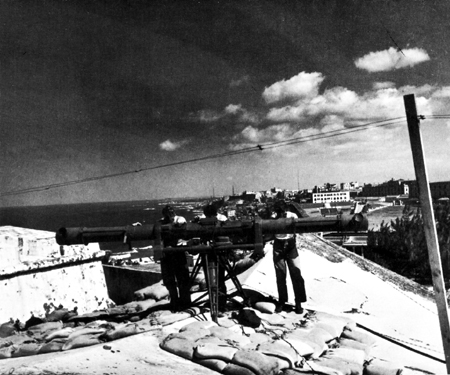

OPTICAL HEIGHT FINDER MOUNTED ON OLD EL MORRO FORTRESS, San Juan, Puerto Rico. U.S. Army post is visible in background.

raiders penetrating the Caribbean, he was more than ever convinced that the principal threat was by carrier-borne aircraft from the Pacific.43

The means for detecting an enemy carrier force before it launched its planes and for sighting the enemy planes before they reached the canal were the nerve center of the Panama defenses. Patrol planes, operating at about the 900-mile radius, were depended upon for the initial warning of an enemy's approach. Long-range radar (the SCR-271 and its mobile version, the SCR-270) was relied upon for the detection of enemy planes at distances up to about 150 miles. Still closer-in, the fixed antiaircraft defenses relied upon short-range, height-finding radar (SCR-268) for searchlight and fire control.

[425]

At the time of the Pearl Harbor attack serious deficiencies existed in the warning and detection system. There were not enough planes and operating bases to carry out the search as planned. There were only two SCR-271 radars in operation, one at each end of the Canal. Although three additional sets arrived by the end of December and were being installed on the Pacific side of the Isthmus, the work was slowed down by a shortage of trained radar engineers and mechanics. There was as yet no airborne equipment for surface vessel detection (ASV) in use and about one-fourth of the 3-inch antiaircraft batteries were without SCR-268 sets.44 Well aware of the situation, the War Department on 22 December gave General Andrews broad authority "to sub-allot funds and take such other action as is necessary for the construction and installation of AWS Detector Stations, Filter Centers and Information Centers . . . ." to the full extent of the requirements as determined by General Andrews.45

There were nevertheless certain deficiencies which were not entirely the result of a shortage of equipment and trained men. Tests in Panama repeatedly disclosed that low-flying planes approaching directly over the Bay of Panama were not detected by the radar system. Visiting British experts had noted this characteristic in American sets and attributed it to a basic defect of the equipment, but the Signal Corps insisted that, properly placed and operated by competent crews, the American equipment in this respect was just as good as, if not better than, the British radar. Whatever the cause, the blind spot remained. Furthermore, neither the SCR-270 nor the SCR-271 was designed to show the elevation of the approaching plane, and neither gave a continuous tracking plot. These qualities were indispensable for ground-controlled interception (GCI), which British experience had demonstrated to be the most successful method for conducting an air defense.46

Much of the construction activity in Panama during these early months of 1942 was devoted to the preparation of sites for additional radar equipment, to the building of access roads, and the construction, at some of the sites, of landing strips. A number of SCR-268 sets were converted for use against low-flying planes, and a proposal was studied to establish picket patrol boats off the coast for visual sighting. Meanwhile, at the suggestion

[426]

of Mr. Watson-Watt of the British Air Commission, Secretary Stimson had taken steps to obtain special low-angle equipment (British CHL [Chain Home Low] radar) from Canada and had personally requested the Canadian Minister of Defense to give first priority to four sets for the defense of the Canal. This the Canadian Government promised to do. The sets were scheduled for delivery in Panama during March and early April.47 At the request of Secretary Stimson, Mr. Watson-Watt, after inspecting the radar defenses of the west coast, undertook to survey the situation in Panama.

The report submitted by Mr. Watson-Watt was as unfavorably critical as the one he had made a few weeks earlier on the west coast situation, and it aroused much the same reaction. Since he viewed things in the light of British developments in ground-controlled interception, it was inevitable that Mr. Watson-Watt should find the SCR-271 and SCR-270 to be very poor instruments, operated by untrained and apathetic crews. He recommended that both models be replaced as soon as possible with Canadian CHL sets.48 His major point, one of such importance that he reiterated it in a separate, personal memorandum for Secretary Stimson, was the necessity for equipping the long-range air patrols with ASV (air-to-surface vessel [radar] ) sets. This, he stated in his note for Mr. Stimson, was "one contribution to the air defense of the Panama Canal so outstanding in importance, urgency and early practicability that it transcends all others . . . ." Since Christmas Day 1941, Mr. Watson-Watt continued, ASV equipment had reached the United States from Canadian factories at the rate of 15 to 20 sets a day, and more than 500 officers and men of the Navy and Marine Corps had been trained in its operation in Canadian schools. "In these circumstances," he concluded, "the complete absence of so much as one installation . . . can only be due to the fundamental failure to visualize the complete transformation which these equipments can work in carrier search." 49 Although the actual deliveries to the Army of Canadian ASV sets were far from the figures cited by Mr. Watson-Watt, nevertheless there were indications that the full potentialities of ASV had not yet been appreciated.50

[427]

In mid-March, immediately after Mr. Watson-Watt made his report, Secretary Stimson himself went to Panama. He returned convinced that the radar defenses of the Canal, particularly ASV equipment, were of the highest priority. Persuaded that without ASV the air patrol would be of very little value and that with ASV the number of planes needed for patrol purposes could be substantially reduced, Secretary Stimson on his return gave "a considerable stimulus to the varied elements of the new defense system." 51

Mr. Stimson's prodding, the efforts of the Signal Corps and Air Forces, construction activity in Panama, and mounting production of radar equipment began to have a cumulative effect. By 1 May, ten long-range detectors (SCR-270 and SCR-271) were in operation in the vicinity of the canal, two were being installed, and another would be available after reconditioning. Six SCR-268 sets had been modified for GCI application and were in operation. Two of the Canadian CHL sets were being installed, and the other two were either on hand or en route. Two other British GCI sets were expected, but the delivery date had not been set. In addition, there was an SCR-270 in operation at Salinas and four SCR-271's were to be shipped to the Galápagos base during the next six or eight weeks.52

By the midsummer of 1942 the equipment situation had been brought fairly well under control. The production and installation of ASV sets would have been taken off the Signal Corps' critical list except for the fact that the equipment had no sooner been placed in the hands of the Air Forces than it became obsolete as a result of the development of microwave ASV. Nevertheless, a shortage, not so much of equipment as of trained operators and maintenance crews, continued to hamper the build-up of the antiaircraft defenses in Panama; and in spite of more and better equipment and more expert, scientific placing of the sets there still remained a blind spot at low altitudes over the Bay of Panama.53 This blind spot was not corrected until the end of the year. Furthermore, the special equipment for ground control of interception had been slow to arrive. The first two sets were not installed until September and did not begin operating until the following month.

[428]

Until then, "all interceptions were made either by air alerted patrols near the canal or by dead reckoning the fighter into the filtered radar tracks." 54

During all these months the air and naval forces had been engaged in combat with the U-boats in the Caribbean. Although ASV equipment had become available by the end of June to the planes that were seeking out and giving battle to the submarines, plans for sealing the gaps in the Antilles screen by installing ground radar on the islands progressed more slowly.55 The inescapable conclusion is that the spotlight which fell on Panama in 1942 had its source in the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, not in the U-boat assault in the Caribbean.

The Army's unpreparedness for the submarine assault that actually materialized was not entirely owing to a shortage of long-range bombers for seeking out and destroying enemy U-boats, although this was part of the reason. Partly to blame also was the reluctance of air officers to employ their bombers in this fashion. The Navy, which was just as reluctantly coming around to the opinion that escort of convoy was the only successful way of handling the submarine menace, was equally unprepared. Both elements of an ideal escort force- ships for surface escort and planes for air coverage-were lacking; and the Army, which had the planes, was unwilling to use them for convoy escort and patrol under Navy command.

For one reason or another the air strength available at any one time for antisubmarine operations in the Caribbean, or even the total strength actually on hand, is not a matter of clear record. From War Department records it would appear that in April 1942 there were on hand in the vast region bounded by Salinas on the coast of Ecuador, the Galapagos Islands, Guatemala City, Guantánamo, the island of Puerto Rico, and Zanderij Field in Surinam, a total of 28 heavy bombers (15 of them equipped with ASV radar), 30 medium bombers, 16 light bombers, and 34 PBY patrol bombers-in addition to pursuit planes.56 For the protection of the Atlantic Sec-

[429]

tor of the Panama Sea Frontier there were the bombers of the Sixth Air Force in Panama; but the Sixth Air Force was committed to the principle of a striking force, a principle which was not strictly consonant with the developing doctrine of antisubmarine operations. The Sixth Air Force had also taken on most of the task of patrolling the Pacific approaches to the Canal and was reluctant to spare more than a few bombers for antisubmarine operations on the Atlantic side. In mid-June, at the height of the U-boat blitz, ten Army bombers were shifted into the Atlantic sector of the frontier, where they were joined by the twenty-four Catalinas (PBY's) of Navy Patrol Wing 3; but this move took place only after all four squadrons of the 40th Bombardment Group were transferred from Puerto Rico to Panama.57

During the summer and early fall of 1942 the antisubmarine forces received substantial reinforcements. Although the Navy withdrew some of its PBY's to buttress the defenses of Alaska when the Japanese invaded the Aleutians, sufficient air and surface craft were assembled in the Panama-Caribbean area to organize a convoy system in July. In August a Royal Air Force (RAF) squadron arrived at Trinidad and immediately proved a welcome addition. By the end of September, according to War Department calculations, there were in the whole area a total of 44 heavy bombers, 65 medium bombers, 22 light bombers, and 105 observation planes plus Navy Catalinas and RAF Hudsons.58

After the first encounters in February 1942, there had been few contacts between bombers and U-boats until June, when planes -Army and Navy-

[430]

TABLE 5-SHIPPING LOSSES IN THE CARIBBEAN AREA

JANUARY 1942-JULY 1944

| Date | Total | Caribbean S.F. (West) 1 |

Caribbean S.F. (East) 1 |

Panama S.F. (Atlantic Sector) |

Gulf S.F. (South-East) 2 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Tonnage | No. | Tonnage | No. | Tonnage | No. | Tonnage | No. | Tonnage | |

| 1942 | ||||||||||

| Jan. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Feb. | 24 | 118,354 | 21 | 103,929 | 3 | 14,425 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mar. | 17 | 99,481 | 15 | 82,073 | 2 | 17,408 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Apr. | 14 | (3) | 12 | (3) | 2 | (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| May | 58 | 255,143 | 35 | 145,652 | 9 | 35,821 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 73,670 |

| Jun. | 66 | 314,562 | 29 | 136,424 | 8 | 53,007 | 13 | 69,508 | 16 | 55,623 |

| Jul. | 28 | 132,110 | 15 | 82,240 | 4 | 15,660 | 2 | 5,630 | 7 | 28,580 |

| Aug. | 46 | 241,368 | 29 | 161,921 | 15 | 76,847 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2,600 |

| Sep. | 32 | 133,450 | 26 | 103,003 | 4 | 22,725 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 7,722 |

| Oct. | 16 | 65,927 | 10 | 30,459 | 6 | 35,468 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nov. | 25 | 149,077 | 17 | 103,508 | 8 | 45,569 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dec. | 10 | 49,950 | 5 | 24,181 | 5 | 25,769 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 336 | 1,559,422 | 214 | 973,390 | 66 | 342,699 | 15 | 75,138 | 41 | 168,195 |

| 1943 | ||||||||||

| Jan. | 6 | 33,150 | 4 | 23,566 | 2 | 9,584 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Feb. | 3 | 16,042 | 1 | 2,010 | 2 | 14,032 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mar. | 8 | 39,226 | 5 | 27,386 | 2 | 9,347 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2,493 |

| Apr. | 3 | 15,147 | 1 | 7,176 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 7,973 |

| May | 2 | 4,232 | 2 | 4,232 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Jun. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Jul. | 6 | 34,806 | 5 | 33,165 | 1 | 1,641 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Aug. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sep. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Oct. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nov. | 4 | 13,792 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 13,792 | 0 | 0 |

| Dec. | 3 | 21,548 | 1 | 10,200 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1,176 | 1 | 10,172 |

| Total | 35 | 177,945 | 19 | 107,735 | 7 | 34,604 | 5 | 14,968 | 4 | 20,638 |

| 1944 | ||||||||||

| Jan. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Feb. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mar. | 1 | 3,401 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3,401 | 0 | 0 |

| Apr. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| May | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Jun. | 1 | 1,516 | 1 | 1,516 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Jul. | 1 | 9,887 | 1 | 9,887 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 3 | 14,804 | 2 | 11,403 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3,401 | 0 | 0 |

1 The boundary between the western and

eastern portions of the Caribbean Sea Frontier is the shipping control line from

65° W, 25°N to 50°20' W, 4°20' N.

2 Only that portion of the Gulf Sea Frontier

lying south and east of a line drawn from Cape Sable, Fla., to Veracruz, Mex.,

is included.

3 Not shown in source document.

Sources: CDC Hist Sect, Anti-Submarine Activities in the CDC, 1941-46, Appendix B.

[431]

TORPEDOED VESSEL BEING TOWED INTO SAN JUAN HARBOR, Puerto Rico.

of the Panama Sea Frontier joined surface forces in a wild chase after one of the German submarines that was causing so much trouble off the Atlantic entrance to the Canal. Three other U-boats were attacked by Army planes in June. But in the same month shipping losses reached a dismal high: 29 vessels totaling 136,400 tons in the Caribbean, 13 in the Atlantic sector of the Panama Sea Frontier, and 16 in the adjacent margins of the Gulf Sea Frontier. Most of the sinkings took place in the waters around Trinidad or in the approaches to the Canal, but no air attacks against U-boats were recorded in the Trinidad area and only one in the vicinity of the Canal.59 In July air units in the Caribbean reported ten or a dozen attacks against U-boats. None of the attacks ended with a kill. Few of them, indeed, resulted in damage; but the number of ships lost to submarines in July was perceptibly lower. In August, Army, Navy and RAF planes delivered at least 18 at-

[432]

tacks against the marauders, and on 22 August the air forces chalked up their first score. The victim was U-654, caught and sunk off Colon by planes of the 45th Bombardment Squadron. But in August the U-boats were again taking a heavy toll of shipping, chiefly in the vicinity of Trinidad and east of the Windward Islands. In the Caribbean, west of the shipping control line, the same number of ships were lost in August as in June; in tonnage, the losses were the highest yet. East of the line, 15 ships totaling 76,800 tons were sunk. During the next month, September, losses continued to run high in the mid-Caribbean area, west of the shipping control line, and Army pilots reported only eight air attacks against U-boats in the entire Sea Frontier; but in the marginal areas shipping losses declined.

Despite their successes, the U-boats were not having things all their own way. In addition to U-654, five others had failed to return from raids in the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico. Reports reaching Admiral Karl Doenitz from his U-boat commanders began to note the danger from fast, land-based aircraft and from numerous patrol vessels, which made it necessary for the U-boats to remain submerged during much of the day, with a consequent heavy strain on the crews. The U-boats, furthermore, did not like the convoy system; their favorite victims were lone, defenseless ships. As a result, Admiral Doenitz decided to pull most of the U-boats out of the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico and to concentrate instead on the area east of Trinidad, where convoys had not yet been reported, where air activity was considerably less, and where surface patrols had been only recently observed for the first time.60 In October, for the first time in six months, not a single vessel was sunk by an enemy submarine in the Gulf and Panama Sea Frontiers. Losses throughout the Caribbean area were the lowest in six months; in the western portion of the Caribbean Sea Frontier they were the lowest since the beginning of the blitz in February.

The cyclical pattern of the U-boat assault had already manifested itself. That the October lull would be followed by renewed activity was expected, but it was impossible to foretell precisely how high the new peak would reach. November began inauspiciously. On the very first day of the month a ship was sunk on the extreme eastern edge of the Caribbean Sea Frontier, about six hundred miles west of the Cape Verde Islands. Then the U-boats began closing in on the eastern approaches to Trinidad, and, before the first week of November was over, eleven more ships had gone down. The indications were that the grievous blows of May and June would be repeated.

[433]

Meanwhile, three weeks had gone by without a single counterattack by Army airmen. At last, on 8 November, a plane of the 10th Bombardment Squadron discovered and bombed a U-boat in the vicinity of Trinidad. The pilot reported that minor damage had been done to the submarine. Several days later a bomber from Curacao spotted and attacked another U-boat. Although these were the only attacks reported by Army planes in November, Navy PBY's and the RAF bombers made five other attacks, while surface craft were responsible for an additional four.61

The biggest event of the month, one that had an important effect on the Battle of the Caribbean, was the landing of American troops in North Africa on 8 November. German submarines began concentrating off the shores of Morocco and along the convoy routes to Africa, and the assault in the Caribbean began to subside. In December only 10 vessels totaling about 50,000 tons were sunk in the Caribbean Sea Frontier. In no subsequent month did the score ever again reach that figure.62 Looking back from the vantage point of the historian, it can be seen that November 1942 marked a real turning point, although at the time not even the most optimistic observer could have said that the end was in sight.

In no other phase of the war did the conflict of instrument employed versus the element in which it was employed and the ancient tug of theater versus function, as the basis for command, produce more sound and fury. Although the stress and strain of it primarily affected the upper levels of the War and Navy Departments, the local commanders and local operations could not entirely escape. Within two weeks after command of the Caribbean was turned over to the Navy, the matter of reinforcements and their control had become a problem, and the question later became confused when the need of air reinforcements to meet the U-boat attack arose. From time to time during 1942 elements of four different Army Air Forces organizations were dispatched to the Caribbean to reinforce the Antilles Air Command, but because of the command situation each of them was retained under the control of its parent organization.63

It was something of a paradox that the organizational confusion resulted in the first instance from the fact that the Navy and the Army Air Forces

[434]

held almost identical theories of organizing antisubmarine forces, namely, on a functional, or task, basis rather than an area basis. In order to give sea-based aviation the flexibility and mobility required for its effective employment, the Navy had made it part of the fleet instead of placing it under the control of local "area" commanders who might have been reluctant to give up forces specifically assigned to the defense of the area-whether naval district or sea frontier. To minimize the pull of local commander and fleet commander, resort was frequently had to the practice of issuing two, and sometimes three, hats to the same individual. Thus, Admiral Hoover was not only Commander, Caribbean Sea Frontier, and Commandant, Tenth Naval District, but also Commander, Task Group 6.3, of the Atlantic Fleet Patrol Force. In his capacity as task group commander under the commander in chief of the Atlantic Fleet, and not as sea frontier commander, Admiral Hoover had command of the Navy patrol bombers that fought the U-boats in the Caribbean.64 On the other hand, it was as commander of the Caribbean Sea Frontier that he exercised unity of command in the area, and Army planes under his control in that capacity could only with extreme difficulty be moved elsewhere. Much the same situation prevailed along the eastern seaboard, where Army planes were placed under the control of the Sea Frontier commander. As a result, quite apart from reasons of tactical doctrine, the Army Air Forces carefully began to build its own antisubmarine organization. Within a framework of research and development, the First Sea-Search Attack Group was activated on 8 June and units of its Second Sea-Search Squadron later operated in the Caribbean. The First Bomber Command, under whose operational control the First Sea-Search Attack Group was placed, had been engaged in the antisubmarine war in the Eastern Sea Frontier, and, in August, units of the 40th Bombardment Squadron of the I Bomber Command were sent on detached service to Puerto Rico and Trinidad. Air Force plans now pointed toward the First Bomber Command "as the organization that would be responsible for AAF specialized antisubmarine activity wherever it might be undertaken." 65

These plans matured in mid-October with the activation of the Army Air Forces Anti-Submarine Command, the cadre of which was the First Bomber Command. Early in December, a squadron of the Antisubmarine

[435]

Command arrived at Trinidad, on detached service from the 26th Antisubmarine Wing at Miami, Fla. It was made clear to the commanding general of the Caribbean Defense Command that this reinforcement was a temporary arrangement only.66 Partly on this account the new arrivals "found no very satisfactory place" in the administrative and operational structure already set up by the Army and Navy in Trinidad. 67

The German U-boat campaign now erupted with renewed vigor in the North Atlantic. As a result of the extremely grave situation, an inter-Allied conference was held in Washington-the Atlantic Convoy Conference-to explore all sides of the problem and decide upon an allocation of planes for antisubmarine purposes. The President was insistent "that every available weapon" be put to use "at once." 68 But the discussions that followed, between Admiral King, General Marshall, and General Arnold, invariably reached a deadlock over the matter of command. The establishment of the Tenth Fleet in May 1943 for the purpose of centralizing and more closely integrating the Navy's antisubmarine activities clearly invalidated the argument that the Army Air Forces could offer a more flexible, functional organization. The arguments then shifted over to different grounds. The issue remained the same. Since neither side would give way, the result was an agreement by which the Navy, recognizing the Army's primary responsibility in the field of long-range strategic bombing, took over full responsibility for the conduct of antisubmarine operations. Long before this agreement was worked out and accepted, on 9 July 1943, the peak of the U-boat battle in the Caribbean had been passed and the theater was in the process of contracting. 69

After January 1943 the enemy was never again a menace in the Caribbean, only a nuisance. Never again did the toll of sinkings approach that of 1942. Never, after January 1943, were the tanker routes from Maracaibo and Trinidad, the bauxite routes from the Guianas, and the approach to the Panama Canal in serious jeopardy. Only a few more than half as many vessels were lost in the Caribbean area in the entire year of 1943 as in the one bad month

[436]

of June 1942 ; in tonnage, the year's loss was less than one-third that of June 1942. This result was due partly to the increased strength, improved equipment, and better training of the antisubmarine forces. It was in part a tribute to Allied victories in more distant waters, and in part a reflection of the shift of German U-boats away from the Caribbean. From October 1942 to the end of June 1943 ,there was only one brief period when more than three or four U-boats ventured at any one time west of the Caribbean shipping control line. This was in early March 1943, when three of them penetrated into the margins of the Gulf Sea Frontier while three others were raiding in the Caribbean. In December, and again in May and June there was only one U-boat in the area. Then, during the last two weeks of July 1943, the U-boat offensive in the Caribbean suddenly flared up again. As a result of the success of Allied aircraft in the North Atlantic, Admiral Doenitz decided to shift operations to safer waters and ordered thirteen of his U-boats to make a concerted attack on shipping in the vicinity of Trinidad and Puerto Rico. But in contrast to the sorry toll exacted by a force of fifteen to eighteen U-boats the previous summer, only six vessels now fell victim to the marauders. Four of the U-boats never returned to their base.70

By the middle of August all but a few submarines had withdrawn from the Caribbean, and thereafter only an occasional U-boat ventured into the area. After July 1943 Allied shipping losses amounted to three vessels in the Caribbean Sea Frontier, six small vessels in the Atlantic Sector of the Panama Sea Frontier, and one vessel in the adjacent waters of the Gulf Sea Frontier. Although shipping losses stood in direct proportion to the number of U-boats in the area, the tally of U-boats sunk by American forces in 1943 was exactly what it had been in 1942.71

The beginning of contraction and retrenchment in Panama and the Caribbean coincided with the beginning of the end of the U-boat threat, but the connection was only fortuitous. As early as February 1942 the War Plans Division had been concerned about the demands for reinforcements that were coming in from all directions. General Gerow, in rejecting a Navy suggestion that the problem of command in Bermuda could be solved by relieving the British garrison, expressed himself thus: "I believe we should make every effort to limit further dispersion of our forces. Unless we call a halt

[437]

somewhere, we will never have forces for an offensive." 72 Against this concern there had to be weighed the desire to provide the fullest possible defense for the Canal, the need of completing and defending the air route to Brazil, and the fact that the Army garrisons were below their authorized strength. In February, the very month in which General Gerow was voicing his concern, about 3,500 troops went to Panama and the Caribbean; and in the next month, March 1942, over 9,500 reinforcements and replacements arrived from the United States. By October the straws in the wind had begun to blow in a different direction. Brazil had entered the war against the Axis in August. Preparations for the North African landings were in the final stage. In the far Pacific the Japanese Navy was so involved with the growing Allied offensive as to render completely improbable any sneak attack against the canal. The possibility of a reduction in the troop basis for the Caribbean Defense Command was accordingly discussed with General Andrews in October, and a decision was reached to place the ceiling tentatively at 110,000 men.73 This was approximately the actual strength as of that moment, but in the three months' interval before the decision began to take effect nearly 10,000 additional troops arrived in Panama and the Caribbean. The peak strength of something more than 119,000 men was reached at the end of December. The build-up had taken thirteen months to complete.

Beginning in January 1943, the reduction continued throughout the remaining two and a half years of war. In April 1943, the category of defense for the Caribbean Defense Command was reduced from "D," which considered the area as exposed to major attack, to a modified category "B," which admitted the possibility of only minor attacks and permitted some relaxation of defense measures. By the end of June 1943 the strength of the Army forces had dropped to about 111,000 men.74

Aside from the general fact that to reduce the strength of any command was always a more complicated and lengthier process than the buildup, there were two elements in the particular situation that helped to explain why the process of contraction gathered momentum as slowly as it did. These elements were, first, a recrudescence of the Martinique problem, in the spring of 1943, and second, the gradual replacement, beginning in January 1943, of continental troops by Puerto Ricans.

[438]

The Allied landings in North Africa and the adherence of General Henri Giraud and Admiral Francois Darlan to the Allied cause had badly shaken the pro-Vichy regime in Martinique and French Guiana. On 17 March 1943 Admiral Robert, High Commissioner for the Vichy Government, lost his hold on French Guiana when the Governor of that colony announced his allegiance to the Giraud government and declared his intention of co-operating fully in the war against the Axis. Admiral Robert was attempting to keep Martinique in line by stern, repressive measures, and the possibility of his using force to suppress the defection of French Guiana could not be lightly dismissed. American naval and air patrols in the vicinity of Martinique were strengthened, and a military mission was hastily dispatched to Cayenne. Although Admiral Robert quickly disclaimed any intention to use force against Guiana, there remained the possibility of a de Gaullist coup and there existed the further consideration that Cayenne Airport, which had been improved by Pan American Airways under the Airport Development Program, might be useful in the antisubmarine campaign. On 20 March the first detachment of American troops entered French Guiana. Le Gallion Field at Cayenne proving unsuitable for large planes, the construction of a new airfield was begun in April, but neither field had an opportunity to prove its value.75

Meanwhile, anti-Vichy sentiment had been spreading in the French islands. In Guadeloupe street demonstrations against Admiral Robert reached such proportions that on the night of 26 April 1943 local police and soldiers were forced to fire on the crowds and several people were wounded. Martinique was on the verge of civil war. The moment was propitious, the State Department decided, for breaking relations with Admiral Robert's tottering regime. The American consul general was recalled, and a joint Army-Marine Corps task force was organized for the occupation of Martinique. The ground components of the force consisted of the 295th Infantry (minus one battalion and the 78th Engineer Battalion, both from Puerto Rico, the 13th Defense Battalion (USMC), and the 33d Infantry (minus one battalion), and 13 5th Engineer Battalion from Trinidad. With attached medical detachments, the total strength came to 5,550 officers and men. Air and naval support forces and the 551st Parachute Battalion were also assigned to the operation. Throughout the month of May the several elements of the task force underwent intensive training in landing operations, in the establishment of a beach-

[439]

head, in street fighting, and in all the various aspects of an amphibious operation such as the invasion of Martinique would require. A completed plan of operations was ready by 6 June. Perhaps Admiral Robert had some intimation of what was in motion, for at the end of June he announced his readiness to turn over control of the colonies to the French Committee of National Liberation. His offer was immediately accepted. Two weeks later a representative of the committee arrived to take up the reins, and Admiral Robert departed. Thus a long-standing, potentially dangerous trouble spot was finally removed. The troops in Trinidad and Puerto Rico settled back into their old and by now tedious role of watchful waiting.76

While the Martinique affair was approaching a crisis, the War Department had gradually changed its policy respecting the employment of Puerto Rican troops. At the beginning of the year 1943 there were approximately 17,000 Puerto Ricans under arms, including the 65th Infantry, and all of them were stationed either in Puerto Rico itself or in the Virgin Islands. The situation, according to the chief of staff of the Puerto Rican Department, was unsatisfactory from the standpoint of training, discipline, and morale; but to send Puerto Rican troops elsewhere in the Caribbean area hinged upon the willingness of the various governments to accept them. Negotiations with the Republic of Panama on this subject had offered little encouragement for approaching the others. When the War Department proposed to send the 65th Infantry to Panama as a replacement for continental troops that were to be withdrawn for service in the Pacific, the Panamanian Government insisted on a careful screening of the unit despite the fact that it was a Regular Army regiment and was to be stationed within the Canal Zone. The record of the 65th Infantry in Panama, where it arrived in mid-January, gave considerable satisfaction to the staff of the Puerto Rican Department and served as an argument for replacing continental troops elsewhere. At the urging of the Puerto Rican Department a small detachment of insular troops was sent to Cuba in late March as a guard for Batista Field, and again the experiment was successful. The War Department consequently decided upon a general replacement of continental troops not only in Panama, but in the bases on British Islands as well, to the extent permitted by the availability of trained Puerto Rican units. Eventually, it was hoped, 20,000 Puerto Rican troops could be made available. A sharp increase in the Puerto Rican induction program was immediately authorized, and arrangements for ob-

[440]

taining the approval of the British Government were begun at once.77 Although the new policy took shape precisely at the time when the plans for an invasion of Martinique were being developed, it rested on the assumption that the Caribbean was a quiescent theater.

Since the induction of Puerto Ricans into the army was accelerated more speedily than the replacement of continental troops, the immediate effect of the new policy was to hold back the reduction in over-all strength. After the summer of 1943 the movement of troops away from the theater and the general curtailment of activities began to pick up speed. By the end of the year nearly 5,000 Puerto Ricans were in Panama; Puerto Rican units had replaced some of the continental troops in Trinidad, Antigua, Jamaica, Surinam, and Curacao, and the over-all strength in the Caribbean Defense Command had been reduced to about 91,000 officers and men.78 By VE-day, in May 1945, the strength was down to 67,500, approximately 10,000 more than on the day the United States entered the war.

[441]

page created 30 May 2002