CHAPTER III

The WAAC's First Summer

On the rainy morning of 16 May 1942. Mrs. Oveta Culp Hobby took the oath of office as Director. WAAC. This event represented a neatly executed coup d'elat on the part of the Army, which, on the night of 14 May, had sent Col. Robert N. Young of the General Staff hurrying to the home of the Secretary of War with the letter of appointment in his hand. The Secretary demurred at the haste but was persuaded that this was the only way to avoid irresistible political pressure the next morning to appoint other candidates who would be disastrously unfamiliar with the Army's plans. Competition for the position was by now so open that newspaper columnists were speculating on various candidates' qualifications, or lack of them.1

Thus on 15 May there was simultaneous announcement of the President's signature and of the appointment of the Director. The appointment ceremony the next morning was witnessed by the Secretary of War, the Chief of Staff, Congresswoman Ropers, Governor Hobby, and a few others. Mrs. Hobby accepted; saying, "You have said that the Army needs the Corps. That is enough for me." The occasion was not particularly inspiring for participants: klieg lights blazed; the speeches had to be given over and over for cameramen: Mrs. Hobby was asked to raise her hand and repeat the oath several times. Furthermore, her wide-brimmed hat proved unreasonably difficult to photograph. Thus the first Waac was sworn in.2

From this moment forward, Director Hobby was faithfully credited by some millions of Americans with having personally initiated the Corps and dictated its every move. Although she had neither originated the idea, written the legislation, nor determined the Regulations, her office repeatedly had to answer inquirers such as an Army private, who wrote: "From whom or whence did she derive the idea of organizing such a unit? 3

There followed immediately a well attended press conference, the first of many to come. The War Department realized the importance of the initial reac-

[46]

MRS. OVETA CULP HOBBY is sworn in as the first Waac by Maj. Gen. Myron C. Cramer. General Marshall, second from left, and Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson were among witnesses of the ceremony.

tion, and General Hilldring said, "This whole thing stands or falls on the next 60 days." 4

The basic idea of the Corps which the Director and the Chief of Staff wished to impress upon the public was that of a sober, hard-working organization, composed of dignified and sensible women. Their work must be shown as real, just as the war was real and the nation's danger was real. Although there might be problems of feminine adjustment, the War Department did not intend to encourage frivolity.

This excellent but somewhat staid approach was not expected by even the most sanguine to offer any great appeal to the press. The Director's staff noted that "news" about women had long been patterned on three stereotypes of the American woman: (1) she was a giddy featherbrain frequently engaged in powder-puff wars and with no interest beyond clothes, cosmetics, and dates; (2) she was a hen-. pecking old battle-ax who loved to boss

[47]

the male species; or (3) she was a sainted wife and mother until she left her kitchen, whereupon she became a potentially scarlet woman. Director Hobby had already taken issue with these views, saying, "Waacs will be neither Amazons rushing to battle, nor butterflies fluttering about." 5 One idea which she was particularly anxious to avoid was the familiar "morale purposes" accusation-that Waacs were not wanted to fill Army jobs so much as to provide companionship for soldiers. General Marshall had been deliberately careful, in urging Congress to pass the bill, to use solely the arguments concerning the usefulness of Waacs as workers, and never those that treated them chiefly as women.6

Here at this first conference was to begin a never-finished battle as to which idea of woman in the Army would prevail whether the public would get stories mainly of her real work and useful jobs, or of her underwear, cosmetics, dates with soldiers, her rank-pulling, sex life, and misconduct. Certain sections of the press were expected to co-operate; in the interest of the war effort, by playing down sensational angles that might hinder recruiting. Since not all could be expected to do so, the Director and her public relations consultant, Mrs. Herrick, sat up the night before the conference listing all possible embarrassing questions that reporters might ask, and rehearsing and polishing the Director's replies so as to minimize frivolous matters and emphasize the serious purpose of the Corps. A comparison of their list with the questions asked the next day showed that they did not miss even one, and in fact thought of a few that the reporters overlooked.

At the press conference, the Director was supported by the Chief of Staff himself, General Marshall, and the head of the Bureau of Public Relations; Maj. Gen. Alexander D. Surles. A routine handout was devoted to recruiting and training plans, enlistment requirements, and other statistics. A description of the uniform, especially the underwear, for which reporters were eager, was tactfully withheld a few days because its procurement was not yet finally approved. Frustrated here, the reporters opened up the expected barrage of questions directed at Mrs. Hobby: 7

Q How about girdles?

A. If you mean, will they be issued, I can't tell you yet. If they are

required, they will be supplied.

Q. Will Waacs be allowed to use make-up?

A. Yes, if it is inconspicuous.

Q. What do you consider that to be?

A. I hope their own good taste will decide.

Q Nail polish?

A. If inconspicuous, yes.

Q. Will the women salute?

A. Yes, they will salute.

Q Will they march and carry arms?

A. They will learn to march well enough to parade, but they will carry no

guns.

Q. Will they be put in guardhouses?

A. No, no guardhouses.

Q. This is a burning question. Will officer Waacs permitted to have dates

with privates?

A. [Here Mrs. Hobby turned to one of the generals

8 for a description of Army

tradition. He explained that Army policy was that officers

when not with troops, and enlisted men when off duty, might associate; but that

he

[48]

hadn't been to the field lately and didn't know how it worked for nurses.]

Some questions became even more pointed. "There was one male reporter in particular,'' reported a spectator, "who kept prodding the woman reporter next to him to ask more and more about illegitimate babies." To this query, Mrs. Hobby replied briefly that pregnant women, married or unmarried, would be discharged.

"The Director handled herself excellently," reported another observer. "She was very direct, forthright, composed; and as candid as could be. She made a good impression." The next day's newspaper stories confirmed this, although a few women columnists 9 pointed out that Mrs. Hobby's previous "unavailability" had not made her popular with newspaper-women who wanted intimate details, and the Negro press attacked the appointment of a woman from Texas.10 In general, the hundreds of clippings collected by the Bureau of Public Relations showed widespread praise for the Corps and the Director. A few spiced up the story with headlines such as "Petticoat Army" or "Doughgirl Generalissimo," 11 and some punsters were obviously unable to resist such opportunities as "Wackies," "Powder-magazines," "Fort Lipstick," and (concerning girdles), "It wouldn't do to let the fighting lassies get out of shape." 12

Male columnists were the worst offenders, in spite of Damon Runyon's remark, "A lady in the uniform of her country will scarcely be an object of jesting on the part of a gentleman not in the same garb." 13 Some of the attacks contained savage comparisons to "the naked Amazons . . . and the queer damozels of the Isle of Lesbos." 14 Others, as expected, had a field day with the idea that woman's place is in the maternity ward. Said one: "Women's prime function with relation to war is to produce children so that the supply of men for fighting purposes can be kept up to par." Another: "Give the rejected 4-F men a chance to be in the Army and give the girls a chance to be mothers." Others became emotional over their assumption that all Waac recruits would be married women who had deserted infants.15

Thus began the fight to hold the line on public relations, which had wrecked recruiting for British women's services. Prematurely hopeful that the worst was over, the Director and her staff began their first day as a recognized and operating headquarters.

Establishment of WAAC Headquarters

"The next month was chaos," said a staff member later. "Every newspaper and magazine writer came down to see us. Important people of all sorts were also now willing to advise us." 16 The open bays of the office at Temporary M swarmed with new clerks, insistent visitors, and hurrying staff members; telephones buzzed and boxes of supplies were stacked in corners.

On the day after the Director's appoint-

[49]

ment, the little headquarters pulled itself together and began to issue numbered memoranda. Now that there legally was a WAAC, the long-delayed funds could at last be allotted for a training center; the tentative Regulations could be published; the items of uniform could be approved for procurement and details released to the underwear-conscious press. More important, the still-nebulous group of preplanners could now be solidified into a real WAAC Headquarters, complete with charts and ready for rapid expansion. Thirty-seven civilians were also allotted, including another woman consultant, Mrs. Gruber, wife of Brig. Gen. William R. Gruber, to advise on military protocol and manage the Director's schedule. The office now totaled some fifty people.17

By any military standards this was hardly an impressive headquarters, scarcely the equal of that of a respectable Army regiment; and in spite of the exaggerated power that was attributed to it by the press and general public, its members by this time entertained few delusions of grandeur. As an insignificant civilian group, which included no general officer, they expected and got a low priority of attention as compared with the more vital phases of the combat effort, particularly in such matters as office space, cafeteria hours, entertainment allowances, and transportation.18

The office had at least a military-looking chief when, in June, there arrived the first WAAC uniform, especially made for Director Hobby. She promptly put it on, reported formally to the Chief of Staff, and came back wearing a colonel's silver eagles, which he had pinned on and directed her to wear. The relative rank of Director was thus established at that of colonel, although Congress had authorized pay equal only to that of a major. Both relative rank and pay were thus established as the same as that recently given to the Superintendent, Army Nurse Corps. The relative rank of full colonel was also necessitated by the grades of the Army officers on her staff, since Director Hobby would be superior in the WAAC chain of command to the commandant of the training center, Colonel Faith, as well as to her own staff, which now included Col. William Pearson as adjutant general and Col. Bickford Sawyer as finance officer.

No later Waacs ever suffered from uniform shortages as did Director Hobby at this time; there was in existence only one WAAC shirt, and in her travels her luggage contained little but an electric fan and an iron, which enabled her to wash, dry, and iron the shirt nightly.

Location in the Services of Supply

Meanwhile, the Services of Supply was considering a more important matter: the proper place in the headquarters chart to insert the square labeled WAAC. Competition for the honor of supervising the WAAC was not exactly brisk; it might be said that each agency outdid the other in striving to bestow this gift on its neighbor.19

[50]

Atone time it seemed that Civilian Personnel Division would be forced to assume control, although this was obviously inappropriate, since WAAC administration would be conducted along military lines. Military Personnel Division, from whence the preplanners had operated, was also inappropriate, as it was strictly a policymaking agency and did not operate, while WAAC Headquarters would operate a training center and various units. The loser in this unique contest was eventually the Chief of Administrative Services, at that time Maj. Gen. John P. Smith. General Smith was shortly to be succeeded by Maj. Gen. George Grunert, who, as a lieutenant colonel, had in 1927 been one of the War Department staff officers to recommend postponement of plans for a women's service corps. The Administrative Services, a large subdivision of the Services of Supply, included many comparable operating agencies, such as the Army Specialist Corps, the Army Exchange Service, and the National Guard Bureau. WAAC Headquarters would now be removed from the Chief of Staff by three echelons: first, the Chief of Administrative Services; over him the Commanding General, Services of Supply; and over both on personnel matters the Assistant Chief of Staff, G-1. The new position was not advantageous in many ways, but it appeared to the Director's advisers that there was at the moment no alternative.20

The WAAC's new status as one of the Administrative Services was set forth to the field by the first important War Department Circular governing the WAAC ---Circular 169 of 1 June 1942--- which, after two weeks of the Corps' existence, at last made the WAAC legitimate. The circular was so brief that a second circular was clearly needed at once, although it did inform the Army that (1) the Director would command the Corps and (2) other Services of Supply offices would set WAAC policy. it gave no details either of command channels or of interoffice co-ordination; neither did it refer to the tentative V1'AAC Regulations. All WAAC plans and recommended policies were required to be sent to the Chief of Administrative Services "for reference to the appropriate staff division of the Services of Supply." The Chief of Administrative Services wrote: "While the WAAC is not a part of the Army, yet the entire administration of the Corps, including its organization and development, must be supervised and assisted by the Services of Supply." 21

As the new Corps began the selection of officer candidates and the establishment of its training center, the work load upon the headquarters; never light, suddenly became so great as seriously to threaten its efficiency. 22 A fourteen-hour day and a seven-day week became standard in the Director's office, a schedule of course not uncommon throughout the War Department at this date. Even this was often exceeded: staff members reported that for days at a time Mrs. Hobby and her assistants worked every night until three, five, and sometimes seven in the morning, averaging only two or three hours of sleep each night, or merely going home for a shower and coffee before returning to work. Staff members worked under condi-

[51]

tions of what they called "awful confusion" and pointed out that the developments of the following months could be seen in perspective only if it was understood that they occurred, not separately and in order, but simultaneously and in the midst of wildly growing national publicity that was in itself a full-time problem.

Director Hobby attempted to cope with the confusion by rigorously budgeting her time. To Mrs. Gruber was given the task of scheduling all persons wishing to see the Director, in the belief that "more speed can be made if she finishes one subject without interruption." Staff members prepared summaries of staff papers and kept a chart for the Director's daily briefing; Colonel Pearson also directed that the Director be left free for "formulation of basic policies." Unfortunately, at this stage everything was new and policy was inseparable from detail; the situation resolved itself into a struggle to meet the daily crises without crushing the Director with decisions. The War Department Bureau of Public Relations required the Director to hold a full two-hour press conference twice weekly. Also, interviews with the public were scheduled four times a week, thus leaving only a few days entirely free for military problems. Even this amount of time was highly unsatisfactory to members of the press and Congress and other citizens who now came to call, and some criticism resulted. One Congressman complained, "I can get to the President in five minutes, but I can't get to Mrs. Hobby at all."

The Director was aware of the problem and stated in an office memorandum:

The successful launching of the WAAC is a public relations problem to probably a greater extent than any other War Department activity. We must establish a reputation for not giving the "brush-off" or "runaround" to those calling.

However, she felt little sympathy toward those who wanted merely a sight of her or some personal favor. She said later:

Many of them were just curiosity-seekers; they could have got accurate information from any Army officer in our headquarters, but they wanted to sit and chat with that new curiosity, a woman in Army uniform.

More important than seeing such people, she felt, were her military responsibilities to the Army and to the women about to join the WAAC.

These military duties, and not the public pressure, constituted the real problem of the heavy work load. The Director realized from the beginning that her duties were exactly the reverse of what they should have been; she said later: "We had foreseen this problem in Canada, and it was one of the reasons why we wanted Army status. Now, we were an Auxiliary and it was none of Army offices' legal business."

For example, the office set out to prepare Tables of Basic Allowances for the WAAC Training Center and for units, and was at once struggling with terms such as "T Square, Maple, Plastic lined, one per publications section"; "Chart, Anatomical, Blood System, one per training center"; "Can, corrugated, with cover, 32 gal, one per 20 mbrs." Realizing that the WAAC's staff of eleven officers did not possess the necessary specialist training to prepare accurate tables of chemical, signal, medical, and other equipment and that the tables could be done quickly by the Army spe-

[52]

cialists who prepared tables for men, Colonel Pearson attempted to send the work to the Chief of Administrative Services for distribution to other Services of Supply offices. It was promptly returned to him with the statement that the only thing wanted for distribution to the SOS offices was the final plan or policy for approval.23 Director Hobby noted further:

We had to prepare our own budget for presentation to Congress-a complicated statistical matter-because the people who prepared Army budgets said it wasn't their responsibility. Then, three of us worked all one night until 9 the next morning writing the recruiting circulars which I had to present for approval to The Adjutant General; TAG wouldn't write them. We had to check all the blueprints for housing at every station-endless, bewildering blueprints.24

In every field of military responsibility, it was the same story. The technical work of the WAAC was done by an office that knew little of the method, and the policy approval was given to agencies that knew nothing of WAAC over-all needs. Staff members realized that, had Army status made it possible, just the opposite organization would have been most efficient. Under the circumstances, most of the summer's tasks were accomplished, if at all, only by a process of mutual irritation.

Colonel Pearson, the office's oldest and most experienced adviser, was likewise unable to obtain from the Services of Supply any clear-cut decision that would enable him to distinguish between policy matters which he must refer to other offices and routine decisions which he could make and put into effect without delay. Colonel Pearson finally forced the issue by sending direct to The Adjutant General for publication a minor decision which he considered routine-that of raising the age limit for the first officer candidate class from 45 to the legal limit of 50. Refusing to publish it, The Adjutant General sent it to Control Branch, SOS, for clearance; Control Branch sent it for comment to Military Personnel Division, which commented and sent it back to Control Branch, which a week later returned it to the WAAC, with directions to draft the circular instead of asking The Adjutant General to do it; and a brief verbal spanking: "In the future, please transmit all matters of this nature to the Chief of Administrative Services."

It was thus established that even simple WAAC decisions would probably be considered policy matters and thus require approval by several SOS branches before they could be put into operation. While such a procedure proved useful in avoiding errors, it became impossible for WAAC Headquarters to act with anything like speed and decisiveness in the emergencies bearing down upon it. 25

Drastic expedients were suggested to the Director by her Army advisers, some involving the disbandment of WAAC Headquarters. The most plausible of these -although probably not legal-was to dismember the office and give the various pieces to the SOS divisions that handled the same matters for men; while the Director and a small office for control and inspection would soar upward for several SOS echelons and attach themselves to the office of the Commanding General, Services of Supply, Lt. Gen. Brehon B. Somervell. From this vantage point the Director could then heckle other offices when dif-

[53]

ficulties occurred. "As it is now," the Army advisers wrote mournfully, "we have to ask help from all of these branches, and maybe get it and maybe don't, and get bounced all around unless we want to go to the top to help us out, and that is a bad system." 26 This plan, although eminently workable, was not be adopted until the WAAC became part of the Army.

In spite of the unresolved confusion and the demands upon them, staff members remained enthusiastic and optimistic; Director Hobby publicly thanked them for their loyalty and for putting so much into the struggle.27

Selection of the First Officer Candidates

From the public viewpoint, selection of the WAAC officer candidates was the only important matter that the WAAC now had on its hands. From the moment of passage of the bill, WAAC Headquarters had been besieged, to the detriment of its other duties, by long-distance telephone calls, telegrams, visitors, and letters of application, all asking commissions. Congressmen, Army heads, and public officials were swamped by demands from friends and constituents. Officers of all the armed forces sought to get commissions for their friends and relatives, while powerful pressure groups sought to name assistant directors. "Every important person had a candidate," said a woman staff member, "and they all wanted guarantees of commissions and important positions.'' 28

Under its legislation, the WAAC could have commissioned many of its officers direct from civil life with appropriate rank, as the Army did and as the WAVES and other women's services were later to do. Mrs. Hobby's previous decision to grant no direct commissions was severely tested. Mrs. Rogers, the Corps' sponsor, urged her to commission several lieutenant colonels at once, as she feared that otherwise the WAAC leaders would have no prestige in their dealings with ranking Army officers. 29 However, it appeared that if even two or three women were commissioned directly, it would be impossible to refuse hundreds of others with prominent sponsors, and Director Hobby believed that Mrs. Rogers' objection concerning rank could be overcome by rapid promotion as soon as the women had demonstrated their ability.

It was General Hilldring's belief that the Director was strengthened in her original decision by the opinions of General Marshall.

The Chief of Staff was a great democrat [said General Hilldring]. I told Mrs. Hobby how, at his direction, I had made a fight to get more officers from the ranks of enlisted men. I told her that he might not object to appointing a few civilian women for the top jobs, but the rest of the officers must come from the ranks. They must be the best women in the ranks even if this was not necessarily the best in the nation.30

Also, staff members in their discussions of this point gave some weight to what they called "the man-woman element," a factor which did not ordinarily operate in the selection of male officers for commissions, but which now made it difficult to judge with entire accuracy the motives behind demands for the commissioning of female friends and secretaries.31

The experiences of other nations indi-

[54]

cated that, by its initial choice of officers, the entire future course of a women's corps might be determined. In England initial limitation of commissioned rank to socially or politically prominent women had left a corps without adequate troop officers. In some Continental countries commissions had been awarded chiefly to enable certain personnel to travel with ranking officers. It was recognized that, without firm leadership at this moment, the first American auxiliary might set out on a similar course. Finally, a General Staff decision was obtained that confirmed the Director's original policy of limiting the future WAAC leadership to those women who would enlist without guarantees, and making it possible to refuse all requests from high authorities without incurring charges of discrimination.32 All applicants who stormed WAAC Headquarters were therefore told to apply at their local Army recruiting stations. Director Hobby's own civilian advisers, Mrs. Woods and Mrs. Fling, had to follow this procedure when they desired to enlist.

By 27 May, Army recruiting stations all over the United States were supplied with application blanks, and newspapers carried the story that the doors were now open for officer candidate applications.33 The response was a rush that swamped recruiting stations and startled recruiters. The Adjutant General had optimistically sent each corps area 10,000 application blanks, a total of 90,000, although only 360 candidates were to be selected. Three days later, urgent calls had already come from the Second, Third, Fourth, and Sixth Corps Areas for 10,000 more each, and from the Fifth and Ninth for 5,000. Of the 140,000 blanks given out, it was assumed that many would not be returned, as the 4 June deadline gave little leeway on delayed applications. Some recruiting officers attempted to weed out the obviously unqualified and to give the scarce blanks only to eligibles.

In New York City, 1,400 women stormed the Whitehall Street office on the first day and stood in line from 8:30 to 5:00 o'clock. In five days over 5,200 had received application blanks in New York City alone, although only 30 women could be picked from the whole of New York State, New Jersey, and Delaware. In Washington 1,700 applied for the eight positions open to the District of Columbia. Numbers as reported by newspapers varied in different cities: Sheboygan-20; Lowell-65; Richmond-65: Baltimore500; Portland-380; Sacramento-135; Minneapolis-600 given out, but only 50 returned; Butte-"a few cautious inquiries." Nothing could be told as yet of the type of woman who had applied. Newspapers featured an Indian woman in full tribal regalia, a sixteen-year-old who wanted to get away from home, a wild-eyed mother brandishing a pistol and demanding to get to the front. It was hoped that these were not typical applicants.34

It had been decided that Army induction facilities could be used for women, with of course the necessary segregation

[55]

for physical examination.35 This decision provided an extra and unscheduled screening device, for only women of some valor dared approach the Army offices. Members of the first class commented: "The recruiting station was the dirtiest place I ever saw." "It was in the post office basement next to the men's toilets." "I was whistled at by the selectees." "Everyone in the room turned to look as the Captain bawled out 'Are you one of them Wackies?' " 36 WAC recruiters were later to find the location and nature of Army recruiting facilities a major handicap in recruiting women.

Some 30,000 women braved this obstacle and filed applications. Their papers were reviewed by the stations, and those who were not obviously disqualified for age, citizenship, or other causes were summoned for an aptitude test. This test had been prepared by the Personnel Procedures Section of The Adjutant General's Office to eliminate 55 percent of all applicants.37 It was attempted to make standard questions more appropriate for females, but some were not easily converted, and women were confronted by such problems as, "You are a first baseman, and after putting the batter out by catching the ball (not a fly) with your foot on the bag, you . . ." 38

Those who passed the aptitude test were further screened by a preliminary local interviewing board of two women and an Army officer selected by the corps area. To avoid appointment of unqualified women to these boards, the preplanners had sent out instructions that members were to be local personnel directors, business executives, YWCA supervisors, and women of like standing. These local boards weeded out those applicants who were visibly unsuited by reason of character, bearing, or instability. Members were asked to consider the question: "Would I want my daughter to come under the influence of this woman?" 39

The numbers passing both the test and the first board still hopelessly overcrowded Army medical facilities for the examination of women. It was therefore directed that only the top five hundred applicants in each corps area be given physical examinations. The examination was not entirely consistent throughout the corps area and it was evident that the Army still had far to go in working out a satisfactory physical examination for women, but it did eliminate those with the more obvious physical disqualifications.

There then arrived at each corps area headquarters an especially selected woman to be the Director's representative on the final screening board. Among the women selected were Dean Dorothy C. Stratton of Purdue, later head of the SPARS, and Dean Sarah Blanding of Cornell, later President of Vassar.40 In spite of the pres-

[56]

SCREENING OF APPLICANT for first officer candidate class by local interviewing board at Fort McPherson, Georgia, 20 June 1942.

sure of time, the final personal interviews were more extensive, and delved thoroughly into each candidate's record in school, college, and business to see if signs of leadership were evident.41 The Director's representatives then returned immediately to Washington bearing the candidates' complete papers, pictures, and interview records. Their private comments varied with the corps areas. One said, "Decidedly disappointed in both number and general type of applicants"; another, "A complete cross-section from young things to professional women"; and a third, "I was impressed with the common denominator shared by the extremes in types-wanting to do organized effective war work." 42

The final selection process was of un-equaled intensity. An evaluating board of eleven prominent psychiatrists 43 searched the work histories for evidences of mental instability, choosing women who showed steady progress and acceptance of responsibility rather than frequent unexplained changes of jobs. Application forms also revealed data on parents and family life,

[57]

whether applicants had ever lived in clubs or dormitories, their travel, sports interests, and health. Answers to the essay question on "Why I Desire Service" were believed to be particularly revealing. There followed what Director Hobby called "four days of careful, almost prayerful, work of making the final selections." 44 The Director personally read each of the final papers. The 30,000 applicants had been reduced to the 4,500 who appeared before the final boards, and in the midst of selection procedure, word came from the Chief of Staff to pick not 360, but 1,300, the papers of the extra candidates to be kept for call to later classes as needed. 45

The work was finally completed late on the night of 30 June. Within a week, corps areas had notified the 360 top-rated applicants, who thus had less than two weeks to close out their jobs, take the oath, and get to Fort Des Moines for the opening on 20 July.

The selected candidates had one characteristic in common: 99 percent had been successfully employed in civil life. Although there was no such educational requirement, 90 percent had college training and some had several degrees. Most fell in the age group of 25 to 39, although 16 percent were under 25 and 10 percent were 40 and over. About 20 percent were married, most of them to men in service, and there were some mothers, especially mothers of servicemen, though none with small children.46 The candidates included many women who had held responsible jobs: a dean of women, a school owner and director, a personnel director, a Red Cross official, a former sales manager, and several editors, and there were many more who had been reporters, office executives, lawyers, social workers, Army employees,

and teachers. In compliance with promises made to Congress, it had been necessary to choose a certain number from each corps area and from each state, regardless of density of population, with the result that many highly qualified women in certain crowded areas had to be turned down, while in certain sparsely settled states it was necessary to take almost every woman who applied.47

Two other problems complicated the task of the selecting authorities: the selection of Negro officer candidates and the selection of Aircraft Warning Service candidates. The Negro problem was particularly delicate, for the Negro press had immediately attacked the choice of a Director, and the National Negro Council had written President Roosevelt protesting the appointment of a Southern woman.48

The opposition was unexpected, since the War Department had early informed Congress that it would train Negro WAAC officers and auxiliaries up to 10 percent of the Corps and Mrs. Hobby had declared her support of the plan; while the Navy Department's WAVES, although not headed by a Southerner, did not accept any Negroes at all for almost three years.

The real cause of the objections came out in later news stories, which revealed that Negro leaders had hoped to use the

[58]

new Corps to break the "traditional and undemocratic policy of the Army and Navy" of placing Negro personnel in separate units.49 Their demand that the WAAC place Negro and white women in the same unit was rejected because the WAAC had been directed to follow the Army policy. Now the National Negro Council recommended to the Secretary of War that Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune and one other Negro leader be commissioned assistant directors, which was of course impossible under the no-direct-appointment policy. To make relations more precarious, it soon became apparent that not enough qualified Negro women had presented themselves as applicants for officer candidate school, and it was feared that WAAC failure to fill the quota of 10 percent would be interpreted by the Negro press as discrimination. Accordingly, Army officers made hurried trips to Negro colleges to attempt to recruit qualified women. Mrs. Bethune assisted in the selection of these candidates, not being within the age limit to attend the school herself. 50

For the Aircraft Warning Service the Army Air Forces asked that it be allowed to put women in uniform without sending them to school, but after long consideration it was decided that AWS officers must graduate from the regular officer candidate school before donning the WAAC uniform. On the matter of selection the Director felt unable to offer opposition, since the women to be selected were already running the operations and filter boards. The Air Forces were therefore allotted eighty vacancies for the first officer candidate class, which brought that class to a total of 440. WAAC Headquarters suffered some misgivings about the absence of the usual tests. However, while choices were later found to include some women without responsible paid experience and with test scores in the lowest aptitude category, Group V, the majority made successful officers.51

There was one applicant for attendance at the school who gave the War Department more trouble than all others combined. This was Director Hobby herself, who had made up her mind to attend the school as an ordinary student in order to understand through her own experience the problems of a woman's adjustment to military training. She stood firm in this decision for some time while the expostulations of shocked advisers raged around her. 52 The Director carried this determination unaltered up through several strata of general officers and was stopped at last only by General Marshall himself, who told her sympathetically but with finality that the thing was impossible under the Army system of rank.

The First WAAC Training Center

Meanwhile, the situation at Fort Des Moines could scarcely have been termed tranquil. Immediately upon passage of the WAAC bill, Colonel Faith and his staff of ten Army officers shot out of Washington in the race to have the training center ready when the women arrived.53 They reached Des Moines with less than two months to spare before opening date.

[59]

Colonel Faith's basic plan in beginning the undertaking was to make the course so military that Army skeptics could find little to criticize. Reporters who interviewed him came away stating, "It will be no glamour girls' playhouse." they gathered that few concessions would be made to "feminine vanity and civilian frippery." 54 Colonel Faith deplored the press phrasing of the matter, and stated later:

It was obvious to all of us that a considerable percentage of the Army was either opposed to the WAAC idea or very doubtful of its potential success. The best way to combat this attitude was to train the new soldiers in those qualifies which the Army values most highly: neatness in dress, punctiliousness in military courtesy, smartness and precision in drill and ceremonies, and willingness and ability to do the job.55

The students were, however, to be taught the Army's reasons for the things they were required to do. "'The American woman is the most co-operative human being on earth if she fully understands an order," Faith declared hopefully.56

Remodeling and new construction at Fort Des Moines began as soon as the induction station and reception center could be moved. Classrooms were erected, stables and plumbing converted, and separate housing provided for the male cadre. The rest of the staff, forty-one officers and 192 enlisted men, arrived about 30 May. 57 The director of training was especially selected by Colonel Tasker: he was Lt. Gordon C. Jones, a former instructor at The Citadel.

Direct communication had been authorized between Colonel Faith and the Director, and this proved indeed fortunate for the training center, which began to send by telephone; wire, and mail a steady stream of requests.58 Dayroom furniture was needed, also a Special Services officer, two women doctors, a post utilities officer, pictures of uniforms for the local press, instruments for the band, and money for everything. Boxes of training literature had not arrived, nor had test forms.

A hostess and a librarian were needed for the service club, also a Red Cross field director. Highly skilled classification teams had to be found to interview and classify the women, who might be expected to have job experience not ordinarily encountered by the Army. The Chief of Finance "strenuously objected" to furnishing a fiscal officer. The Corps of Engineers had no capable post utilities officer to offer. The $20,000 already allotted to the Seventh Corps Area was so restricted that Colonel Faith could not use it to purchase many of the miscellaneous items needed. There was no money for entertaining the scores of prominent people who desired to view the school.

These assorted requests, coming as they did during the period when WAAC Headquarters was struggling to establish its own organization and policies and to select officer candidates, quickly began to reveal still more of the difficulties which the Director's office must face as an operating headquarters. Most of the fairly minor matters discussed with Colonel Faith could easily have been decentralized to the Seventh Corps Area had the WAAC been in the Army, but since it was a separate organization, all of its funds and

[60]

personnel allotments had to be handled separately and justified by the Director's office.

The Adjutant General had meanwhile directed various Army commands to select and send to Des Moines the men who would serve as instructors and cadre until Waacs could take over.59 This personnel had no sooner reported than it was discovered that few if any of the instructors were qualified for the exacting and unprecedented task ahead. The director of training wrote:

Out of 41 officers which we requested originally, we got one man who is fitted for the job at hand. The others are all doing their best to fill jobs far beyond their former experience. The new officers are all fine fellows (we are fortunate to have gotten no duds) but professionally . . . .60

As the time grew shorter, it became apparent that some deficiencies were inevitable. Requisitions for field and technical manuals, circulars, forms; and Army Regulations were only partially filled or back-ordered, with no assurance from harassed supply depots that they could be filled within the next six months. The post's two mimeograph machines ran continuously to duplicate missing material.61 Funds for certain equipment did not arrive on time, and neither did some of the faculty. Colonel Tasker wrote, "The lieutenant who was to join your force cannot be located. Please let me know if others are missing." 62 Even ahead of these difficulties came the greatest problem of all, and an unexpected one-expansion.

Expansion Plans, Summer of 1942

In the midst of the WAAC's hurried preparations there occurred an event which was to bring far-reaching changes to all plans. On 13 June 1942 the Chief of Staff called into his office three Army officers representing the Chief of Administrative Services, the Office of the Director, WAAC, and Aircraft Warning Service.63 General Marshall informed these men that in view of the approaching Army personnel shortage it was his desire that every effort be made to organize and train personnel of the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps at the earliest possible date. He felt it would be possible to have considerable numbers in active service a great deal sooner than existing plans provided. The staff officers were directed to formulate the necessary speed-up plans.

All British precedent indicated that such a move meant great difficulty for the WAAC. British observers had commented, "It is difficult for the general public to realize the strain created by the great expansion of the women's services, built up as they have been . . . from almost non-existent foundations." 64 Director Hobby and the preplanners had fervently hoped for at least "time for trial and error before going into an assembly-line type of production." 65

Nevertheless, WAAC expansion was a calculated risk that the Army's current situation made necessary. In spite of earlier optimistic estimates, the armed forces were now experiencing what historians called "the manpower crisis of the summer of

[61]

1942." 66 The Army Ground Forces was already short more than 160,000 men. Only two days before General Marshall's decision the War Department had admitted the necessity either to train units understrength or to slow down the activation of new units, thus jeopardizing invasion plans. It was also being forced toward unpopular measures such as drafting eighteen-year-olds and fathers and cutting more deeply into defense industry and agriculture.67

On the other hand, the WAAC was concurrently rocking along with its modest prewar plan for about 12,000 women in the first year. Meanwhile, thousands of women were clamoring for admittance, and requisitions for over 80,000 of them had by this time been received from Army commands, of which at least 63,000 seemed suitable for employment. This did not include the needs of overseas theaters and many other domestic commands which had also shown interest.68

Thus, WAAC expansion seemed logical in spite of its practical difficulties. The Army itself was faced with the same expansion problems, and men were training with wooden guns, sleeping in tent camps, and wearing clothing often inappropriate to the climate, all with greater success than might have been expected. The WAAC move was nevertheless the greater risk, since men could be drafted to face these hardships while women would have to volunteer.

Plans for expansion were drawn up by the Services of Supply at hasty conferences on 14 and 15 June and submitted to the Chief of Staff on 17 June. The WAAC's ultimate strength was to be increased at least fivefold, from 12;000 to more than 63,000. Within a year, by May of 1943, there would be in the field 25,000 instead of the 12,000 previously planned for that date. Within two years, or by April of 1944, the entire 63,000 would be trained and at work. The divisions of the Services of Supply concerned believed it would be possible to manage this expansion successfully, and gave it their written concurrence. 69

The plan was approved by the Chief of Stall; although within three months it, too, was to be discarded by the General Staff in favor of still greater expansion. This moment marked an important turning point in Corps history: up to this date, it was obvious that the WAAC had been forced upon an unwilling Army by a combination of circumstances; from this time forward, its employment was not only voluntary but was extended more rapidly than its original sponsors had contemplated.

As the first result of the plan, construction at Fort Des Moines was stepped up by 20 percent, and action was taken by condemnation to lease Des Moines hotels, garages, office buildings, college dormi-

[62]

tories and classrooms, and even the local coliseum, so that specialist training might be given in the city, leaving more room for basic trainees at the post. 70 A tent camp was set up at Fort Des Moines for an additional 634 male cadre, who were intended to stay only four months, until Waacs could graduate and replace them. Action was not taken until 3 July to order these men in, and most arrived at Des Moines scarcely one jump ahead of the women whom they were to instruct.

It was now determined that the first officer candidate class of 440, which began on 20 July. would be followed by classes of 125 women weekly until at least 1,300 officers had been trained. Officer training time had already been cut from three months to six weeks. It had also been decided to start the first class of enrolled women soon after the first officer candidate class, without waiting for WAAC officers to graduate and assist in their training. Enrolled women would have only a brief four weeks of basic training, instead of the originally planned three months.71

Specialist schools-for cooks, clerks, and drivers-would be ready to function in August when the first enrolled women graduated from basic training. Thus it was believed that it would be possible as early as 9 November 1942 to begin sending three fully trained headquarters companies, with officers and cadre, to field stations each week, and to train and return to their station 300 Aircraft Warning Service Waacs weekly, beginning in September. 72

The First WAAC Officer Candidate Class, 20 July - 29 August 1942

By 20 July 1942, with the opening of the first officer candidate class.73 the mounting interest of press and public reached a point of near-hysteria. The old post at Fort Des Moines swarmed with dignitaries, invited and uninvited, who braved the steamy midsummer Iowa weather in order to view history in the making. Every angle of the new scene was well documented by the press; while photographers invaded the barracks in search of the still elusive WAAC underwear. Authorities were particularly alarmed to discover that a number of women reporters had resolved to participate in the first week of processing in order to reveal to the waiting public a woman's every sensation as she was converted info a soldier. Because it was not yet known whether the women's sensations would be printable, this request was refused, and the press was informed that the post was theirs for one day only. After that, a two-week news blackout was to be enforced while the Army and the women became acquainted in comparative privacy. This step seemed necessary to avoid complete disruption of training, but was later believed by some staff officers to have alienated certain writers and news agencies.74

Before crowds of interested Des Moines citizens the arriving Waacs were whisked

[63]

WAAC STAFF AND MEMBERS OF THE PRESS at Fort Des Moines, Iowa, 20 July 1942.

[64]

from incoming trains to waiting Army trucks. At the fort processing moved efficiently and included a brief physical check, an immediate meal, and assignment to one of the four companies. Each woman was assigned a bed, a wall locker, a footlocker, and a metal chair, and soon discovered that the Army had no bathrooms, only something two flights of stairs away called a latrine. Male company officers and cadre clung to their orderly and supply rooms, designating the first arrivals as barracks guides for the rest and hastily, if inaccurately, informing all comers that only married men with children had been given this assignment.

The issuance of uniforms was the main interest. Mobilized at the clothing warehouse were almost all of the saleswomen and fitters from department stores in Des Moines, and the Waacs were passed down an assembly line from one curtained booth to another. The underwear and foundation garments proved to be of excellent quality, although the rich mud-brown color of slips and panties was slightly disconcerting.

The morning was not an hour old before more was learned about women's uniforms than had been discovered in the past six months of research. It was immediately apparent that the articles shipped to Des Moines by the Philadelphia Quartermaster Depot bore little resemblance to the model that had been approved by the preplanners. The heavy cotton khaki skirts were cut as if to fit men's hips, and buckled and wrinkled across the stomach, so that even the slimmest Waac presented a potbellied appearance after she had sat down once. When Waacs walked or marched the skirts climbed well above the knee, unless a desperate grip on the skirt was substituted for the required arm swing. The hot, stiff cotton jackets, made of men's materials, draped as becomingly as a straitjacket and were of much the same texture. Shrieks of dismay arose as women tried on the WAAC caps, uncharitably christened "Hobby hats," which were not only unbecoming to many women but also cut the forehead and were easily warped, crushed, or soiled.

Furthermore, the Quartermaster size range had apparently been set up for a race of giants, and there here not enough small sizes in outer garments. As extensive alterations were necessary to cut down larger sizes, most of the women emerged with nothing to wear for a day or two except the brown-striped seersucker exercise suits-short button-front dresses worn over matching bloomers. However, the cameramen were diverted to a few women whose uniforms fitted without alteration; these were placed in the front row for platoon pictures or posed beside the post's one cannon.

The rest of the processing, carried on intermittently during the week, closely followed the Army pattern for men. There were simultaneous tetanus, typhoid; and smallpox shots; outside the dispensary stood an embarrassed Army sergeant with smelling salts, which actually proved little needed. The Articles of War were solemnly explained, although they applied to a Waac only in the improbable event that she should find herself "in the field." Lessons were given in bed-making, care of clothing and equipment, the difference between fall out and fall in, the beginnings of close order drill, and the other Army orientation that for men was usually given at reception centers. Women were given the standard Army General Classification Test (AGCT), and their skills were classified.

[65]

On the fourth day, with processing completed and the women at last neatly uniformed in khaki skirts and shirts, Director Hobby addressed the group for the first time. She had been at the Fort since the first day, observing somewhat wistfully. Vow she spoke words calculated to remove the military trees and reveal the forest, to give the women perspective on history and where they now stood in it:

May fourteenth is a date already written into the history books of tomorrow .

. . . Long-established precedents of military tradition

have given way to pressing aced. Total war is, by definition, endlessly

expansive . . . . You are the first women to serve . . . . Never forget it . . .

.

You have just made the change from peacetime pursuits to wartime tasks from

the individualism of civilian life to the anonymity of mass military life. You

have given up comfortable homes, highly paid positions, leisure. You have taken

off silk and put on khaki. And all for essentially the same reason-you have a

debt and a date. A debt to democracy, a date with destiny. . .

You do not come into a Corps that has an established tradition. You must make

your own. But in making your own, you do have one tradition-the integrity of all

the brave American women of all time who have loved their country. You, as you

gather here, are living history. On your shoulders will rest the military

reputation and the civilian recognition of

this Corps. I have no fear that any woman here will fail the standards of the

Corps.

From now on you are soldiers, defending a free way of life. Your performance

will set the standards of the Corps. You will live in the spotlight. Even though

the lamps of experience are dim, few if any

mistakes will be permitted you.

You are no longer individuals. You wear the uniform of the Army of the United

States. Respect that uniform. Respect all that it stands for. Then the world

will respect all that the Corps stands for . . . . Make the adjustment from

civilian to military life without faltering

and without complaint . . . .

In the final analysis, the only testament free people can give to the quality of

freedom is the way in which they resist the forces that peril freedom.75

As one of the women later said, "It was only then that I really knew what I had done in enlisting. I looked around the roomful of women and suddenly had no more doubts that it was right. My feet stopped hurting, and the: war and my place in it became very real."

From this time on the work began in earnest. The women were up at five-thirty or before in order to be neatly dressed for six o'clock reveille, a process that took most women somewhat longer than men. After making beds, cleaning, and picking up cigarette butts and photographers' flash bulbs in the area, the women marched to breakfast and then began classes, which lasted until five in the afternoon, with an intermission for lunch. After supper there was a required study hour and then a session devoted to the washing and pressing of uniforms and the shining of shoes.

The WAAC basic and officer candidate courses were identical with corresponding courses for men, except for the omission of combat subjects. Women studied military sanitation and first aid, military customs and courtesy, map reading, defense against chemical attack, defense against air attack, interior guard, company administration, supply; mess management, and other familiar subjects. A few courses were more or less adapted to women. The hygiene course was designed by the local hospital

[66]

personnel to apply to women's hygiene. The Army organization course contained vague references to WAAC organization, which no one even in Washington understood too well. Drill was without arms, and the physical training course was devised and conducted by a civilian consultant.76

The military courtesies course, which set out to permit no deviations for women, soon ran into the inescapable fact that there were socially accepted differences for women to which the Army must perforce conform. For example, women of some faiths could not remove their hats in church as was proper for men, and most women felt self-conscious about removing hats in such places as dining rooms and lobbies. Endless commotion was also caused when women attempted to open doors and show other required courtesies for men who outranked them. Army officers were, for the first time, confronted with a situation in which a man might be either an officer or a gentleman, but not both; there resulted much sprinting for doorways and leaping out of the wrong side of vehicles to avoid the eager assistance of a nearby Waac.

As the women learned about the Army, the Army also began to learn the many minor yet important items about the administration of women that could be learned only by experience. Oddly enough, these were not the expected difficulties that the planners had feared, for the women were agreeable about inspections and did not have hysterics in the barracks or faint at the discomforts of latrine ablutions. Instead, unique specific needs arose, more practical than psychological.

For example, a few laundry tubs and ironing boards had been provided, although men's barracks ordinarily did not have them. On the first day, the Waacs as one woman headed for these-a true WAAC pattern which was not to vary through hundreds of stations in the field and it was discovered that the women considered the number of laundry tubs, drying racks, and irons inadequate. Women stood in line until late at night for a turn at the irons. Many Waacs were found to have brought their own irons, in numbers which so frequently blew out barracks fuses that their use had to be limited. The allowance of four khaki shirts and four skirts did not permit use of local laundries, which took a week, for the women considered that neat appearance in the sticky hot climate required at least one and often two clean shirts daily.

Lack of opportunity to launder and iron her shirt for the next day was to prove a greater morale hazard to a woman soldier than any lack of movies, camp shows, and pinball machines. The women's anxiety about the matter gave strong support to a fact which civilian psychologists had already suspected, and which was to prove a new problem to station commanders: that a woman's grooming was vitally connected not only with her morale but with her health and actually with her conduct.77

Similarly, the women felt that the Army provided too few brooms, too little scrubbing powder; and not enough dust cloths. The women also suffered somewhat, as did male recruits, from sleeplessness, sore feet, heat and humidity, and somewhat more than men did-from the general lack of privacy.

Other expected difficulties with wom-

[67]

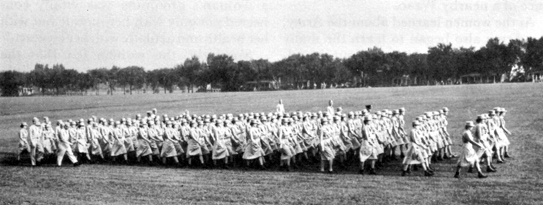

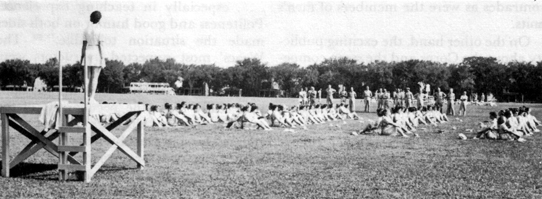

FIRST OFFICER CANDIDATE CLASS, 20 July - 29 August 1942. Top, reveille; middle, instruction in Military Customs and Courtesy; bottom, close order drill.

[68]

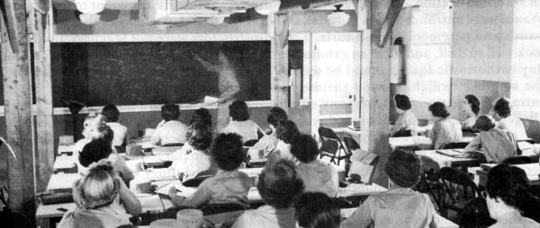

FIRST OFFICER CANDIDATE CLASS, 20 July - 29 August 1942. Top, classroom instruction; middle, physical training; bottom, chow line.

[69]

en's administration did not arise. Most Waacs were entranced with parades and bands and ceremonies of all sorts. They took well to drill; and after an exhausting day enthusiastic squads could be seen in the summer twilight, giving themselves extra drill practice. One company officer alleged, "They learn more in a day than my squads of men used to learn in a week." They were not disconcerted by the necessity for discipline and regimentation; their shoes were shined, uniforms spotless, beds tightly made, footlockers neat. Neither did they prove especially subject to quarrels, but appeared to be as good comrades as were the members of men's units.

On the other hand, the exciting publicity about the Corps and the steep competition for places had prepared women very little for the fact that the Army lacked wings and a halo. One disappointment was the caliber of the instruction at the training center. Ninety percent college women, the Waacs expected classes of challenging difficulty. Realizing this, WAAC Headquarters had sent Military Personnel Division a long account of the qualifications desired in the instructors assigned, saying, "The results to be obtained at the WAAC Training Center will depend in a large measure on the type of instructors which are detailed . . . . Time is too short to permit training these individuals after their arrival at Fort Des Moines." 78

Colonel Faith felt that the resulting selection had been good, since the instructors were a "group of fine and sincere young men" who, although with little Army experience, were for the most part graduates of The Adjutant General's School or others of similar level.79 Nevertheless, it became apparent to the students on the first day of classes that most of the instructors were not teachers, not public speakers, not college men, and sometimes without Army experience in the subjects they were teaching. It was a lucky young instructor who did not confront in every class some students with college training or years of teaching experience. The situation was similar to that which the WAVES were to encounter a few months later, of which the Navy noted, "The early indoctrination was largely farcical, with youthful male Reservists parroting material they had just received, to women their seniors . . . especially in teaching experience. Politeness and good humor on both sides made the situation tolerable." 80 The Waacs' most respected instructors were often the teachers of company administration, newly commissioned former sergeants who really knew the peculiarities of the morning report, although one of them startled his first class by welcoming them with, "Put dem hats on dose tables." 81

There were other situations that the women solemnly noted for correction in the days when they would be running the Corps. All companies habitually marched out to mess at the same time, so that the last of the 440 stood in line for an hour. The aptitude tests were given at 7:00 P.M. of a stifling summer evening, immediately after a heavy meal. The summer uniforms were like nothing ever before worn by woman, with five sweat-soaked layers of cloth around the waist and three around

[70]

the neck.82 The young officers did not seem to know how to put in their places the female apple polishers and classroom show-offs whose tactics were transparent to other women. The food was good and abundant but not always attractively prepared. These and similar occurrences gave the first hint of what was repeatedly demonstrated: that Waacs were often less tolerant of imperfection than men-a trait which some Army psychologists believed was due less to their sex than to the fact that all were volunteers; since male volunteers also frequently showed greater impatience than did draftees.83

This first class was nevertheless still too uncertain as to correct procedure, and too eager to please, to be very critical. General morale was at unprecedented heights. Women stood retreat with real appreciation of the ceremony. They trembled lest their company officers give them a gig. They crossed streets and ran out of doorways to practice their salute on everything that glistened, until the outnumbered male officers were forced to flee the front walks. No imperfection seemed of much importance when weighed against the general desire to justify the Army's admission of women to its ranks.

On the eve of graduation there occurred one further test of the new soldiers' soldierliness: the release of the roster of class standing. Herein, it was discovered that young women who had dated their company officers had mysteriously soared in rating to outrank the older women who had led their classes in training.84

Since many of the company officers were ex-college boys of 19, any woman over 30 had evidently appeared antique. Katherine R. Goodwin, who later headed some 50,000 Army Service Forces Wacs, recalled: "Captain B. called me in and told me I was so old he didn't sec how I could have made the journey to Des Moines, and that he couldn't imagine what use the Army could ever make of me, and perhaps I had better go home before I got any older."

Angry members rose in class to ask an explanation of the mathematics involved in rating, and an inquiry was launched by WAAC Headquarters. In general it was found that the honest tendency of the male officer was to consider a glamorous young woman; or a mannish loud-voiced one, the best material for leadership of women, whereas the women themselves had given highest ratings to women of mature judgment, and to those with a faculty for sweeping and polishing their share of the area. It was concluded that the problem would correct itself in later classes where women company officers had replaced men. However, the same situation was later to cause some difficulty in the field where men ordinarily selected and promoted WAC officers.

Graduation day, on 29 August; saw 436 new WAAC third officers, all with shining new gold bars but no WAAC insignia.

[71]

which The Quartermaster General was late in procuring. Mrs. Hobby spoke to the women, and Congresswoman Ropers told them: "You are soldiers and belong to America. Every hour must be your finest hour." 85 The Army was represented by Maj. Gen. James A. Ulio, The Adjutant General, and Maj. Gen. Frederick E. Uhl, Commanding General, Seventh Corps Area. General Marshall personally wrote out a congratulatory telegram for Director Hobby, saying, "Please act for me in welcoming them into the Army. This is only the beginning of a magnificent war service by the women of America." 86

[72]

Page Created August 23 2002