CHAPTER V

November 1942 January 1943: Plans for a Million Waacs

While Director Hobby was overseas, the necessary steps were taken by the Services of Supply to carry out the September expansion plan. To verify G-3's estimate of a need for 1.500,000 Waacs, The Adjutant General's Office was asked to make a list of all the Army jobs suitable for women. A committee of classification experts at once began the project, the most comprehensive study ever made of the outer limits to which replacement of men in the United States Army could theoretically be pushed.

The Adjutant General's Estimates

After pondering over each of the 628 military occupations listed by the Army, The Adjutant General's committee came to the conclusion that 406 were suitable for women and only 222 unsuitable. A job was deemed unsuitable if it involved combat, if it required considerable physical strength, or if the working conditions or environment were improper for women. Jobs requiring long training time were also eliminated. Typical of the jobs ruled unsuitable were brake inspector and railway operator (too heavy and requiring too much training time), switchboard installer (too heavy), laborer (too heavy), intelligence specialties (improper environment), and so on. All supervisory jobs were automatically declared unsuitable for women. The committee likewise, after some disagreement, ruled that for psychological reasons women should not be used in such jobs as classification specialist, personnel consultant, or psychological assistant, since: in these jobs they might be called upon to classify recruits for combat duty, and it was felt that men would resent being classified as suitable for combat by individuals who were themselves noncombatants. The committee nevertheless admitted that, in an acute manpower shortage, women could actually be used in many of the 222 jobs thus ruled unsuitable.

The Adjutant General, using these lists, determined that in 1943 there: would be 3,972,498 men in Army jobs appropriate for women-over half of the Army's strength at that date. In the interests of caution, this number was reduced to allow for the fact that some jobs, although of a suitable type, might be rendered unsuitable by their location or for some other reason. For instance, it would not be economical to maintain women at small stations where only a few could be used; it would not be wise to replace all of the supply clerks at any station, since work too heavy for women might occasionally oc-

[92]

cur; women could not conveniently do the office work in men's units. With such deductions, it was decided that women could fill 450,000 of the Army's 665,256 administrative and clerical jobs; 100,000 of the 834,600 motor transport jobs; 25,000 of the 121.000 radio operators' positions; 30,000 of 96,755 supply jobs the total of women who could be used immediately was 750,000, and by the end of 1943 it was estimated that at least 1,323,400 could be used. Thus it was discovered that G-3 Division had, if anything, been conservative in estimating that 1,500,000 Waacs could be used by 1946.1

Estimates Based on Field Requisitions

Simultaneously with its request for The Adjutant General's theoretical estimates, the Services of Supply conducted a field survey to provide a practical check on the numbers usable by the Army. On 22 October, a few days after Director Hobby's departure, the Services of Supply informed its subordinate commands that further use of Waacs was contemplated, and asked for recommendations as to which jobs under their jurisdiction could be filled by WAAC personnel.2

Requisitions prompted by this letter were soon pouring into WAAC Headquarters, increasing those already arriving as a result of the earlier June expansion plans. They were listed in order of receipt, except for urgent cases, and forwarded for final approval in turn to the Chief of Administrative Services, the Chief of Operations, and G-3 Division of the War Department.

In order to determine which requests merited final approval, it was necessary to devise a number of new policies concerning the types of work and places of employment which would be authorized for Waacs. The number and variety of the requests went far beyond the four simple types of jobs originally authorized. The Air Forces requested Waacs for some thirty-one different technical and mechanical duties: the Signal Corps, Transportation Corps, Corps of Engineers, Ordnance Department, Chemical Warfare Service, and other agencies listed dozens of new types of work, many of which could not be filled by women except after Army technical training. There were also requests for new types of companies: Machine Records Units; Finance Department Companies, Base Post Offices, Mess Companies, and others for which no WAAC Table of Organization as yet existed. There were many requests for 4Vaacs to replace civilians: as clerks in post exchanges, as laundresses, and in other non-Civil Service work. Several commands wanted mobile units for combat theaters, and the Signal Corps wanted these units mixed, with men and women in the same company. 3

As a guide for determining which of these requests to honor, a most important policy had been recommended by Director Hobby before her departure: that Waacs not be allowed to replace civilians and that they be considered only for the 406 Army jobs included in The Adjutant

[93]

General's study. The Director stated that she had understood from the beginning that Waacs were to replace only enlisted men, except in the Aircraft Warning Service. General Grunert disagreed, recommending that stations be allowed to use Waacs in civilian jobs that they could not get civilians to accept. 4 G-1 Division upheld the Director, and the policy was established that "First priority rill be given to requests which result in WAAC personnel relieving enlisted men of the Army for combat duty." 5 This was a policy of enormous importance to the Corps' entire future employment.

It was also decided that first priority was to be given to fixed installations in the United States and second priority to fixed installations in foreign theaters of operations. Mobile units were not, however, ruled out of consideration at some future date when all other needs were filled. 6

No requests for Waacs to perform new or unusual military duties were disapproved; but it was obvious that actual provision of Waacs for such work would depend upon the establishment of new training schools and of types of units other than the standard Table of Organization company. Research was authorized to find some more flexible means of allotment which would permit Finance, Hospital, Mess, and other units.

The number of Waacs that could be used was greatly limited by a decision not to employ them in Washington, D. C., where as much as one third of the Navy women were eventually to be employed. This prohibition had originally applied to the Services of Supply only, having been announced by General Somervell at a staff meeting as an off-the-record policy for his Chiefs of Services, one of whom accidentally recorded it:

Our policy can be only the policy that he has announced to us. That policy he particularly does not want committed to writing, because the minute that anybody gets a hold of it and puts it in the paper, there will be a mess. This is the policy . . . he does not want any of them here, except in the Office of the Headquarters of the WAAC, and certain ones in G-2; whom for some reason they prevailed upon him to have. Do you get it? We don't want anything said about it. 7

However, a few weeks later, when it became clear that the War Department and the Air Forces were planning to bring Waacs into their headquarters, General Somervell recommended the policy in writing to the Chief of Staff, "in order that field agencies may have full benefit of the services of members of the WAAC." This policy was approved by the Chief of Staff and put into effect, with exceptions to be granted only by his own office for important secret work.8 It was also generally agreeable to WAAC Headquarters, since assignments to Washington were not popular with enlisted women who wished to work on a military post. However, the policy caused added confusion in current planning, since agencies such as the Signal Corps, which had attempted to get WAAC officers to aid in planning for enlisted

[94]

women, were obliged to relinquish them when informed that, ``by order of General Somervell, no WAAC officers will be placed on duty in the space occupied by the Office of the Chief Signal Officer." 9

Even with the various limitations; the results of the field survey generally upheld The Adjutant General's estimates. It was difficult to make an exact calculation of the constantly shifting requests, but the total, which had been 63.000 in midsummer and about 82,000 at the beginning of October, jumped to 386.267 toward the end of November and to 526,42 3 in December. These figures included only "actual requests . . . based on present tentative plans as to how and where Waacs can be used." 10 Thus, if more than 500,000 women could be assigned immediately, before overseas theaters and many other commands were heard from, it was clear that the G-3 estimate of 1,500,000 by 1946 had not been in excess of probable field requirements.

Considerable change in planners'' thinking resulted from the somewhat amazing revelation that, in a modern Army, possibly half of all "soldiers' " jobs were appropriate for women. With little natural limit thus existing upon the use of womanpower, major decisions were clearly required as to the Army's future policy: the number of women that it would attempt to employ in World War II, the rate at which it would take these, and the means by which it would attempt to get them.

The first and easiest solution to occur to most planners was that of drafting women. Although Director Hobby was not available for consultation, the Services of Supply on 4 November 1942 recommended to the War Department that, in furtherance of G-3's plans, legislation be sought to draft some 500,000 women yearly through regular induction facilities. According to SOS estimates, there were 25,605,179 women of ages 20 through 44 in the United States, of whom about 13,000,000 should be available for the war effort. Even if the WAAC required the present maximum Adjutant General's estimate of 1,300,000, this would constitute only 10 percent of the pool, leaving 90 percent for industry, farm, and other armed services. In recommending that the Army draft women, the Services of Supply noted:

The nation is obligated to see chat women will be placed to best advantage, not only from the standpoint of economical use, but to aid any disastrous aftermath due to misplacement in the war effort, or by the employment of women who have definite obligation in other fields . . . . It is to the advantage of the nation that the best use be made of this pool of labor, and it certainly should not be frittered away in useless competition between competing agencies in our country.11

Unfortunately for the speed of WAAC planning, this proposal was so serious as to require extended War Department consideration and high-level negotiation with other agencies. It was realized that any such proposal from the Army would provoke considerable public outcry and Congressional opposition, and therefore could

[95]

be publicly made, if at all, only with the full co-ordination of the sponsoring agencies. For this reason, as the winter of 1942 continued, no War Department reply as to the possibility of drafting women was received by either General Somervell or WAAC Headquarters.

The Weakness of the Auxiliary System

A second possibility which presented itself to planners was that of seeking legislation to give Waacs full military status. If a draft was later to be sought, such status was essential; even if it was not sought, there was already considerable evidence that no greatly expanded employment of womanpower was possible on an Auxiliary status.

In particular, it became clear during the autumn that most plans for overseas service must be canceled if the Auxiliary status continued. This was a serious blow, for the whole idea of the Corps had originally been thought of by the War Department as a means of preventing the confusion of civilian overseas service that occurred in World War I. During her visit to England, Director Hobby received from Lt. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower a request for immediate shipment of the two overseas companies then in training and for quick organization of a number of others. She also discovered-at that time top secret information-that the invasion of North Africa was imminent and that it was General Eisenhower's intent to take 4Vaacs with hire.

Director Hobby returned to the United States on 11 November, much impressed by the need for Waacs in General Eisenhower's headquarters, where she had observed a colonel typing a letter by the one-finger method. However, after conferring with her staff about current Comptroller General and Judge Advocate General decisions on the WAAC's legal status, her enthusiasm abated. It had recently been decided that Waacs were not eligible for the various benefits that protected men overseas-they could not, like the men, receive extra overseas pay; they were not eligible for government life insurance as men were, and would probably invalidate their civilian insurance by entering a war area; if sick or wounded they would not be entitled to veterans' hospitalization; if they were killed their parents could not collect the death gratuity; if captured by the enemy they could be treated as the enemy pleased instead of being entitled to the rights of prisoners of war. Under the circumstances; it appeared impossible for the Army to assume the responsibility of ordering women overseas; nor did the military situation yet require it, as the Director pointed out to the Chief of Staff:

One of the primary reasons for the establishment of the WAAC was to replace men. Until necessity dictates otherwise, conditions in the theaters of operation indicate replacement in the United States.

The Army classification system should be able to find among men the skills needed by the Army in the European Theater of Operations. Members of the WAAC can thus properly replace men found in the United States and release them for essential Army service overseas . . . .12

General Marshall therefore somewhat reluctantly postponed any consideration of immediate shipment overseas except for the two all-volunteer units already trained, saying: "They do not enjoy the same privileges that members of the Army do who

[96]

become a prey to the hazards of ocean transport or bombing." 13

In addition to negating plans for overseas shipment, it appeared possible that continued Auxiliary status would cause a rift with the Army Air Forces, which had been expected to employ more than 500,000 of the projected million-plus Waacs. Shortly after the Director's return from Europe, representatives of the Air Forces informed her that they could not employ Waacs on an Auxiliary status and would prefer to seek legislation for their own corps. General Marshall temporarily squelched this effort with a note to the Air Forces on 27 November:

I believe Colonel Moore this morning took up with Mrs. Hobby the question of her attitude toward a separate women's organization for the Air Corps. I don't like the tone of this at all. I want to be told why they cannot train these women, why the present legal auxiliary status prevents such training.14

The attitude of the Signal Corps and other employing agencies continued to be very similar to that of the AAF.

It also began to appear that the Army would have difficulty in obtaining any large corps of women on an Auxiliary status in competition with the newly organized WAVES, who could offer women all military benefits-fret mailing, government insurance, allotments to dependents, reinstatement rights to jobs, veterans' bonuses, and other advantages, none of which the Waacs were entitled to.

However, the granting of full Army status to women still appeared to many Army men as a drastic step, particularly in view of the fact that only a few units had as yet left the training centers. In late November it was finally decided to delay decision on both draft legislation and on Army status for the WAAC. The head of the Army's Legislative and Liaison Division, Brig. Gen. Wilton B. Persons, advised the General Council to postpone consideration of further legislation of any sort "until the Waacs have taken the field and demonstrated their usability." 15

A few days later, Director Hobby submitted a substitute proposal believed to be more palatable to Congress: that of merely registering women in order to obtain accurate knowledge of the manpower potential of the nation according to numbers, skills, and other data. This recommendation was also approved by General Somervell and sent to the Chief of Staff on the first anniversary of Pearl Harbor.16 However, it also was known to have small chance of immediate approval.

Proposals for Expansion on Auxiliary Status

There remained to planners the least desirable of the possible means of Corps expansion: to attempt to undertake G-3's directed program by voluntary recruiting and on an Auxiliary basis. A certain amount of action could be taken under existing legislation. It was therefore decided that, as a preliminary measure, the full 25,000 authorized by executive order should if possible be enrolled by the end of December 1942 instead of by the following June. Next, the Secretary of War petitioned the President to change the executive limitation from 25,000 to the full 150,000 authorized by Congress. The

[97]

President agreed and on 19 November 1942 raised the WAAC strength limit to 150,000. The Secretary of War indicated that the 150,000 women would be enrolled as fast as training facilities permitted, after which further legislation would probably be recommended.17

Meanwhile, recruiting quotas were opened as wide as training capacity would permit. From a beginning of 1,259 in July and 2,019 in August, the number of reported recruits had increased to 3;536 in September. In October and November, as Des Moines neared its maximum capacity, slightly over 4,000 women a month were enrolled. For December, estimated training capacity permitted advance quotas of approximately 6,000.18

In order to determine how fast the rest of the 150,000 could be enrolled, the General Staff called upon WAAC Headquarters for estimates as to the recruiting and training facilities that would be required to train 150,000 women by various possible dates, as well as greater numbers by later dates. The two WAAC training centers' combined peak capacity would plainly be insufficient to supply such numbers except over a period of years. The General Staffs desire was to take as many women as possible as rapidly as possible, since Army jobs were already waiting and since applicants might accept other war work if required to wait. Against this desire had to be balanced the practical question of where to get basic and specialist schools, of which the Army currently had none to spare. Compilation of a list of suitable schools was begun. It was also necessary to work out large flow charts to govern intake and output of proposed training centers and specialist schools, so that on a given date each would simultaneously produce exactly the required number of basics and specialists to make up exactly the number of WAAC companies departing for the field on that day, and for whom exactly the right amounts of housing and clothing were ready. Such charts had to be worked out for every possible total strength that the War Department desired to consider for every possible date.19

Opinions differed widely as to how quickly the WAAC should attempt to reach the 150,000 mark. Maj. Gen. Miller G. White, the new G-1 of the War Department, recommended to the General Staff in November that the Corps reach this number by July 1943-a deadline that would require at least 20,000 recruits a month for the intervening months, as well as several new training centers. An even more optimistic recommendation came from the new head of WAAC Headquarters' Recruiting Section. Capt. Harold A. Edlund, who advised a target of 50,000 a month, or 750,000 in 1943. Captain Edlund stated: "It may be that the goal outlined will appear to some as outside the realm of reason or possibility . . . but the reaching of 'a more modest goal is doubly assured if we bend every effort for the greater enrollment figure." On the contrary, General Surles, chief of the War Department Bureau of Public Relations, gave his opinion that not even 150,000

[98]

could be obtained; and added: "We have about exhausted that group of women who are willing to volunteer to leave their homes." 20 This was also Director Hobby's opinion; after her return from Europe she expressed the opinion that not even 150,000 women could be recruited by voluntary means.21

The somewhat unfortunate effect of this division of opinion was that, for the remainder of 1942, the War Department was no more communicative upon the subject of WAAC 1943 goals than it had been upon the questions of legislation. As a staff member later observed:

The Corps was placed in the position of a small businessman who overnight was told he must increase his business more than eight times, and to do it at once even before he knew what he was to product, out of what materials, when or how the product was to be made, and with practically no organization to assist.22

While it was realized that major decisions concerning womanpower could not be made easily in these, the darkest months of the war, their absence caused continued confusion in the new headquarters. At the same time, developments in the two training centers gave grounds for grave doubt as to whether any sort of expansion program could be supported.

In the second week of November, just before Director Hobby's return from England, urgent telegrams were received from the commandant at Fort Des Moines, pointing out that clothing shipments had again failed just as recruits were increased. The improvement caused by General McNarney's intervention in October had lasted scarcely a month.

Immediate investigation by WAAC Headquarters drew an alarming reply from The Quartermaster General: clothing promised to Fort Des Moines could not be delivered as scheduled. Also, no clothing could be sent to Daytona Beach by its opening date, as previously agreed by the Services of Supply. The Quartermaster General stated that his previous commitments had been contingent upon immediate letting of contracts and, for unexplained reasons, Requirements Division. Services of Supply, had again held up approval of the contracts for more than six weeks.23

On 11 November Director Hobby returned from England to find a recurrence: of the September crisis at Des Moines: hundreds of recruits without winter clothing, and sickness rates again high. Colonel Hoag reported the entire supply of clothing now exhausted except for a little summer-weight underwear. The civilian clothing in which recruits arrived was far from adequate protection for four weeks of winter training in snow-covered Fort Des Moines. Most women had been instructed to bring only one outfit, and this, particularly in the case of women from the southern and southwestern states; frequently included nothing warmer than a dress, a light topcoat, and open-toed shoes.

[99]

Units were now being shipped to the Aircraft Warning Service in the same civilian clothing in which the women had reported for training. It was known that trainees had written of these conditions to friends and relatives.24

Director Hobby's attempts at remedial action were somewhat delayed by the fact that, upon her return, she was immediately ordered to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, to lecture to the Command and General Staff School on the proper administration of Waacs. She had brought back from England much valuable material on this subject, none of which had any effect on the situation. The fact was that the American WAAC was helplessly repeating every one of the British WAAC's mistakes, not because the WAAC did not know them and how to avoid them, but because their occurrence hinged on outside factors over which it had no control.25 Nevertheless, three days after her return from England, the Director called in the two training center commandants; Colonels Faith and Hoag, for a meeting with Colonel Catron, Colonel Tasker, and herself. Here, in a stormy session, Colonel Faith alleged that the Services of Supply were neglecting the Waacs because they were not military personnel. He had particular reference to his experiences in trying to open the Second Training Center; for example:

Colonel Faith: I feel it is the function of this department [WAAC

Headquarters] to get the War Department to understand that the Waacs are

soldiers. It looks like I am going to have to open a training center at Daytona

without anything . . . . I am not going to tic down because I do not have

clothing, but I do sense the feeling that the War Department believes they have

an Army, and some Waacs. . .

Colonel Catron: No, the War Department feels that the Waacs ought to have what they need, but the clothing is not available . . . . I do not believe there is a tendency to say there is an Army and some

Waacs;

not in the Services of Supply. . .

Lt. Colonel Tasker. I think there was that condition . . . .

[Colonel Faith goes on to describe how The Services of Supply refused him

other equipment normally furnished to Army

schools.]

Director Hobby: . . . Let me straighten out the position of this

headquarters. You are given a job to do and a time schedule to do it on; and

when your equipment does not come through I want to know about it. I will say

another thing: you will find a lot of people with a bureaucratic frame of mind

that would kill anything new unless you fought for it. It is my job to fight for

it.

26

A number of events therefore occurred on 21 November. On that day the Director stopped all further shipments of uniformless units to the Aircraft Warning Service. She simultaneously directed recruiters to warn recruits to bring enough warm civilian clothing to last for several months. She also requested and received from her Army staff a report on the action they had taken to date. This report showed not only that all Services of Supply staff divisions had concurred before expansion plans had been put into effect, but also that the Quartermaster General's Office had been informed by telephone in June and again in September as soon as WAAC Headquarters had itself learned of the plans. With this report in her office, and also General Madison Pearson, she therefore telephoned General Somervell's Chief of Staff, Maj. Gen. Wilhelm D. Styer. 27

[100]

What was said was not recorded, but observers reported that it was sufficient to bring General Styer down the hall to WAAC Headquarters. Staff members were under the impression that Director Hobby mentioned that her own resignation would be necessary if the Services of Supply did not intend to give the WAAC the equipment for survival in the coming winter. In any event, General Styer was found to be not in agreement with the previous management of the WAAC supply program by his subordinates, which he attempted to correct by personal telephone calls on the spot. Emergency procurement of any available kind of cold weather garments was authorized. 28

The situation at Daytona Beach also was found to be critical. Before Director Hobby's return, a meeting had been held in General Grunert's of-Face to consider whether to cancel the scheduled opening of the second training center, since it could not be supplied with uniforms. Lieutenant Woods personally made the decision that the Army's stated needs must be met, in spite of the inconveniences to trainees. The Second WAAC Training Center therefore opened on 1 December 1942 as scheduled. It was virtually without equipment; shoes had been sent, and 600 utility coats scarcely enough for one week's trainees.29

Colonel Faith forwarded requests for improvement in the scattered housing and other facilities at Daytona Beach. A British report brought back by Director Hobby noted that to house women in scattered billets usually damaged health, administration, and the "amenities," and that "for young recruits undergoing basic training it is generally very unsuitable." 30 It was obvious that Waacs in Daytona Beach must either do without recreation or attend civilian night spots of doubtful respectability. Since a tent camp was being built to house some 6,000 of the trainees, Director Hobby asked in early December that it include the recreational facilities normally provided for an Army camp of 6,000 men-one theater, one service club, one library, and one post exchange. However, the Chief of Engineers objected on the grounds that critical building material would have been required; and the request was rejected by Requirements Division, Services of Supply. Colonel Faith also believed the commercial laundry facilities inadequate, but his requests for military supplements were refused by the Services of Supply. 31

Colonel Faith's most serious concern, however, was not the: lack of material facilities so much as the difficulty in getting competent Army cadre to augment the staff, which remained inadequate even after the original Army cadre was divided and the newly graduated Waacs assigned to all possible duties.32 The greatest need was for highly competent key Army offi-

[101]

cers. The Director's requests for certain individuals by name had been refused, and General Grunert informed her that the WAAC would be assigned only officers unfit for duty with male troops. At the November commandants' meeting, Colonel Faith and Colonel Catron came to open dispute over this decision, with Colonel Faith stating: "I absolutely refuse any reduction in the quality of material. We cannot go any lower. We cannot allow any more culls . . . . I don't want a one of them. I cannot make it any stronger."' To this Colonel Catron replied, "You will find lots of good material in the over troop age group. I think you are going to have to take it." Director Hobby added, "My own limited service in the War Department has taught me that it is difficult to get quality for the WAAC. It seems to be against the theory." 33

The seriousness of the objections to the Daytona site was not to become fully evident for several months, but it was sufficiently clear to Director Hobby, when she saw the center for the first time in December, to cause her to demand that the already scheduled Third WAAC Training Center be located on an Army post. Accordingly, she requested assignment of Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia, just outside of Chattanooga, Tennessee. Fort Oglethorpe was in a central location, which would make it convenient to draw trainees from most of the United States; it was also in a temperate climate. Nonconcurrences on its use for Waacs were offered by the Provost Marshal General, who maintained an internment camp there, and by the Commanding General, Army Ground Forces, one of whose mechanized regiments would also be forced to move. These objections were overridden by the Chief of Staff himself and Fort Oglethorpe was designated the Third WAAC Training Center. Col. Hobart Brown was selected to command it, and its activation date was set for 1 January 1943, with recruits to report in February.34

In order to co-ordinate the work of the three training centers and the others that might be expected, it was decided to group them into a WAAC Training Command, which would form an intermediate echelon between the training centers and WAAC Headquarters.35 Colonel Faith was chosen to command the new agency, and was promoted to the rank of brigadier general-an action that created a somewhat peculiar military situation, since the head of the WAAC Training Command was himself immediately under the command of Director Hobby, who wore colonel's eagles. Nevertheless, the rank of brigadier general was obviously quite modest for the commander of three large posts. General Grunert accordingly proposed that action be taken to change the Director's relative rank to that of brigadier general, and the Director immediately asked that equal rank be given Colonel Catron. General Somervell shelved both proposals and directed that no action be taken, pending decision on his proposal to draft women, which would necessarily place the WAAC in the Army. If the Corps should be given Army status, its Director and regional directors would become staff advisers instead of commanders, and an upward adjustment of

[102]

BRIG. GEN. DON C. FAITH shortly after his promotion and assignment to command the WAAC Training Command.

the allotted grades of female leaders as the Corps expanded would not be obligatory.36

Shipment of the First Post Headquarters Companies

For sometime disgruntled station commanders had complained about the repeated postponement of arrival dates originally given them for WAAC post headquarters companies. Many, ignorant of the fact that all available Waacs had gone to staff the Daytona Beach training center, began to repeat the rumor that the Corps was a failure and would never materialize in the field. One WAAC service command director noted; "I spent most of my time apologizing to my General for the peculiar behavior of WAAC Headquarters." 37

The necessity for staffing the Third WAAC Training Center with cadre again set back the shipment schedule of post headquarters companies. By Christmas of 1942 only two Army stations had received their promised shipment-Fort Sam Houston, Texas, and Fort Huachuca, Arizona.38 These units went out well equipped with winter uniforms at the expense of those remaining in training centers, in compliance with the: Director's ban on shipment in civilian clothing. They were also more fortunate than the pioneer Aircraft Warning Service companies, in that careful preparations had been made for them by the WAAC service command directors.

The women as a whole were consumed with eagerness to reach genuine Army stations, and both morale and discipline were good. Mrs. Woods noted later, "In spite of the difficulties topside, the spirit of the women was remarkable, especially the fervor with which they accepted all sorts of unexplained difficulties. There sprang up among them an unexcelled esprit de corps." 39

The arrival of the first Waacs at Fort Sam Houston on 17 December was described

by a WAAC spectator, who wrote:

The consensus of opinion at Fort Sam Houston was that it would be unfair arid

unwise to parade a company upon the day of

its arrival by troop train. In fact the remark was made: "They will not make a

good impression while disheveled." You would

have been

[103]

proud, however, if you had been standing there when they got off the train-their noses were powdered, their shoes were shined, they showed that they were well-trained and well disciplined. Before the last ones had got off the train, the cannon was fired for retreat. Like one woman they came to attention and saluted . . . . The salutes so impressed the photographers that they stopped taking pictures and faced the flag . . . . I am sorry that no pictures were taken at that time.40

The other unit, composed of Negro enrolled women with Negro officers, was likewise well received at Fort Huachuca, and housed in new barracks with hairdressing facilities, recreation room, and athletic area. Upon arrival the women found their bunks already made up and their first meal prepared.41

Shipment of post headquarters companies to the seven other service commands was postponed indefinitely to permit the opening of new training centers, but the defrauded commands set up such protest that certain exceptions had to be made. Just before Christmas Director Hobby called a meeting at New Orleans of WAAC directors from the service commands, to explain the situation and to point out that delay at this stage would result in tremendously greater supply when all training centers came into full production. Nevertheless, all appealed so earnestly for at least one unit per command that Director Hobby promised to send it, as token to the service commands that Waacs really did exist. This was done, and during the last of December 1942 companies were placed on orders for shipment to stations in the remaining seven service commands. Very little could yet be told of what their assignments or job performance would be, although WAAC Headquarters eagerly awaited such news.42

In December also two experimental antiaircraft units reached the field, their "secret" station being actually Bolting Field, within sight of the Pentagon. The Antiaircraft Artillery, as directed by General Marshall, began the task of determining which of its duties could be performed by women and with what degree of success.43

Considerably more complications attended efforts to get the first two units overseas in December. These units had been ready for shipment since September, and were by this date: trained to a hair-trigger state of tension while waiting for a shipment priority from England, which had not arrived. To ease the crowding at Des Moines, they were shipped to Daytona Beach, as soon as its cadre arrived, for another period of training.44 Their morale was scarcely improved by the constant turnover of officers. Since no one yet knew what qualities a women leader needed, there was a process of trial and error by which several officers were successively relieved from duty because of in-

[104]

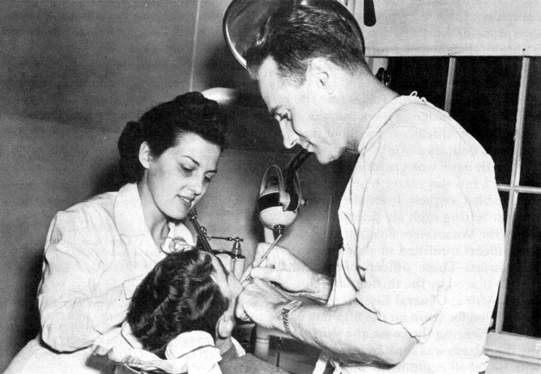

ON THE JOB AT FORT SAM HOUSTON, TEXAS. Motor pool attendant, above; dental assistant in the post dental school, below.

[105]

sufficient experience, lack of outstanding ability, or domineering traits and a habit of "treating adult women like high school freshmen." 45

The prolonged delay could not be explained to the women, since even their destination; like all troop movements, was classified; in general, they attributed it to vacillation and bungling in WAAC Headquarters. Actually, shipment waited upon authority from the European theater, which had requested activation of the units but had not yet furnished shipment priority. At the same time, Operations Division of the General Staff informed WAAC Headquarters that shipment without a priority was impossible because of the shipping jams resulting from the invasion of North Africa in November.46

Disbandment of the units was being considered when, a few days after the invasion, General Eisenhower cabled for a company of WAAC typists and telephone operators for North Africa, and provided a high shipment priority. However, although the units earmarked for London contained the necessary specialists, Director Hobby felt unable to assume the responsibility of ordering them into the more active North African area without the protection of military status.

The danger was graphically demonstrated a few days later when, in answer to a cabled request from the European theater setting high air priority, the first five of the Waacs were flown to England five officers qualified to act as executive secretaries. These officers were immediately placed by the theater on a ship for North Africa; General Eisenhower had in fact cabled for them on the fifth day of invasion. Nearing the coast, the ship carrying the Waacs was sunk by enemy action, with loss of all equipment. The five Waacs were fortunate enough to be rescued by a lifeboat and a British destroyer, but the scare was sufficient to emphasize the War Department's untenable position had the issue of hospitalization, capture, or death gratuity arisen publicly.

At this, Director Hobby herself flew to Daytona Beach and told the assembled women that their shipment must be either canceled or diverted to an unnamed but dangerous combat theater to which she would not order them against their wishes. She noted later that she reminded them of their lack of military status and its protection and "that I wanted them to appreciate the full significance of what I was saying." Then, in a speech which spectators called reminiscent of another Texan's at the Alamo, she called for volunteers to step forward to fill the unit. There were 300 women in the room, of whom 298 volunteered upon the instant. At this, Director Hobby was unable to continue speaking and hastily sought privacy in a broom closet. 47

Half of this number were chosen, processed, and ordered to the staging area in December. The remainder were held until the European theater had three times more postponed its shipping priority, when they were disbanded and sent to other duties.48

[106]

FIRST AMERICAN WAACS EN ROUTE TO NORTH AFRICA. (Photograph was taken in London, 30 November 1942.)

[107]

PROCESSING FOR OVERSEAS. Members of the first WAAC unit to go overseas receive their immunization shots, above, and are inspected by the WAAC director, below.

[108]

PROCESSING FOR OVERSEAS. Waacs give each other a lift to waiting trucks, above, and, below, are helped over the rail and onto the ship's deck.

[109]

Thus, by the end of 1942, the WAAC could boast two training centers open and a third being readied, twenty-seven Aircraft Warning Service units, nine service command companies shipped or ready to ship, two secret units with the Antiaircraft Artillery, and one on its way overseas. In late December Director Hobby reminded her staff that, in spite of the uncertainties and hardships of rapid expansion, "Our six months' achievement is really something to boast about." 49 Whereas she had originally promised the War Department 12,000 Waacs by July of 1943, the Corps had achieved that strength by December of 1942, with 12,767 enrolled. The year had witnessed a complete revolution in military thinking on the use of womanpower: in January, 12,000 Waacs had seemed too many; but in December, 1,200,000 seemed too few.50

The WAAC's first Christmas brought added praise from the Chief of Staff, in the name of the Army, for the Corps' spirit and contributions.51 At Christmas also, anticipating the greater effort that would be required by the impending General Staff decision, the Director telegraphed her staff, "May God bless you and give you strength for the task ahead." 52

Indecision as to Planning Goals

Strength of some sort was needed, for by January of 1943, planners feared that the WAAC could not survive unless the General Staffs decision as to its size and future status came quickly. It had now been almost five months since G-3 had called for 1,500,000 Waacs without setting definite goals. When these were not announced by the beginning of 1943, it was necessary to set an interim recruiting quota for January of about 10,000, based on existing training capacity. Reports indicated that this was being met, and that training centers were seriously overcrowded, yet by all evidence the Corps was still far from approaching the peak of General Staff expectations. It was learned informally that it was the General Staffs intent to authorize at once still another training center, the fourth. Again field shipment schedules were outdated and previous plans held up.53

At a meeting on 6 January, staff officers noted that, until it was known how big the Corps would be and how many new training centers would be required, it was impossible to set up shipping schedules or to tell Army stations when Waacs would arrive. The Quartermaster General and the Chief of Engineers were frantic for estimates on clothing and housing requirements which could not be given them.54 Neither was it possible to publish detailed discharge and other regulations-to remove the: burden of casts still coming to the office-since the Judge Advocate General desired to wait for a decision on the Corps' future status.55 Staff members, in

[110]

terviewed later, commented. "No one seemed to know what he was doing." One of the ablest of the early staff members, Colonel Tasker, who had been replaced as Executive by Colonel Catron, now gave up in despair and transferred to the General Staff in spite of Director Hobby's protest that "his knowledge concerning the creation and growth of this activity is such that his reassignment would be a very real loss.'' 56 Similarly, First Officer Helen Woods, the first woman to serve as Acting Director, applied for transfer to a regional directorship as far from Washington as possible.57

By the end of the year it was obvious that the October office reorganization directed by General Somervell's inspectors was a failure, and Colonel Catron again reorganized the headquarters. Previous divisions were abolished and two new main halves were set up-Operating and Planning. It was thus hoped that the daily crises and emergencies of operation could be kept from disturbing the calmer atmosphere necessary to finely calculated schemes and schedules, while at the same time action on urgent field needs would not be delayed because staff members were busy preparing estimates for the General Staff. The Planning Service was headed for a few weeks by Colonel Tasker and later by a new arrival, Lt. Col. Robert F. Branch; the Operating Service was headed by another new arrival, Col. Howard F. Clark, a regular Army officer of many years' experience. For the more technical aspects of personnel planning and statistics, a civilian woman consultant, Miss B. Eugenic Lies, was also employed. The employment of a civilian appeared to be the Director's first move to overcome the rigid channelization which prevented her contact with junior staff members, since Miss Lies was given authority to ignore all office channels in securing information for the Director.58

This reorganization also was a failure almost from the beginning. Colonel Branch soon recommended that his large Planning Service be dissolved, saying, "It is a good deal like having a Diesel engine connected with a sewing machine." 59 With Planning and Operating Divisions both the same size and considering the same subjects, it proved virtually impossible for planners not to operate, or for operators not to plan; overlapping and disagreement resulted. Also, as Colonel Branch pointed out, it was useless for the WAAC to make any plans at all in the face of its dependence on other un-co-operative or dilatory agencies. He said:

The opportunity scarcely exists for original or creative planning, since the problems of the Corps have been principally composed of situations after the fact. Action is therefore remedial in nature and choices are limited. Congressional action, War Department policy, and the attitude of other agencies are imitations which, regardless of their propriety or necessity; reduce the scope of planning work.60

Many badly needed improvements, which were never made or which were delayed, were ordered by Director Hobby during this period. Finer adjustments and accurate research were to be impossible until

[111]

a solution could be found to the basic problems of survival.61

By the end of January, when no directives were forthcoming from the General Staff, the WAAC planners, milling about helplessly among their schedules and flow charts, were in dispair. The office's Daily Journal for 1 February indicated: "Director asked General Grunert to obtain from the General Staff a definitive directive governing recruitment, training, and use of Waacs, particularly within remainder of fiscal year." As a result, General Grunert's office wrote the General Staff asking a quick decision on: "(1) how many Waacs we are to recruit and train by July, (2) where we can get training capacity, and (3) how we are to slow down recruiting if we do not [get the above]." 62

[112]

Page Created August 23 2002