1

2

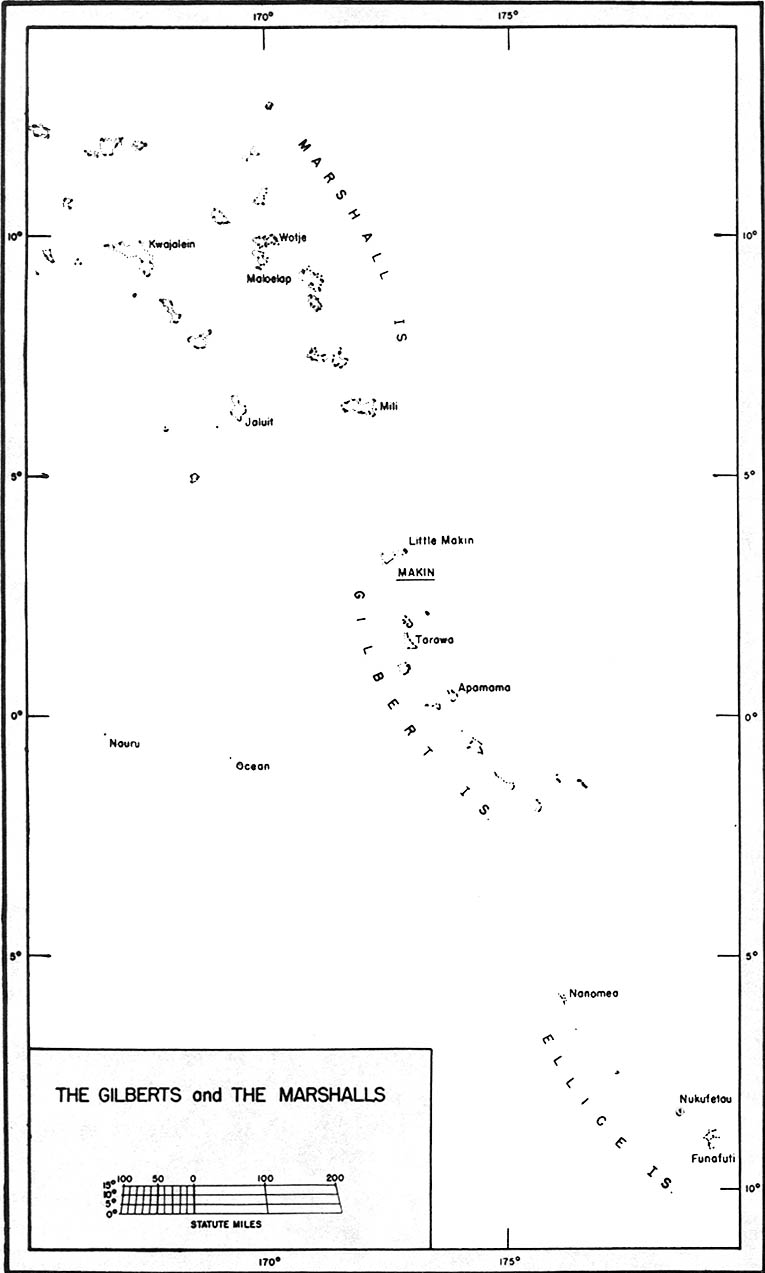

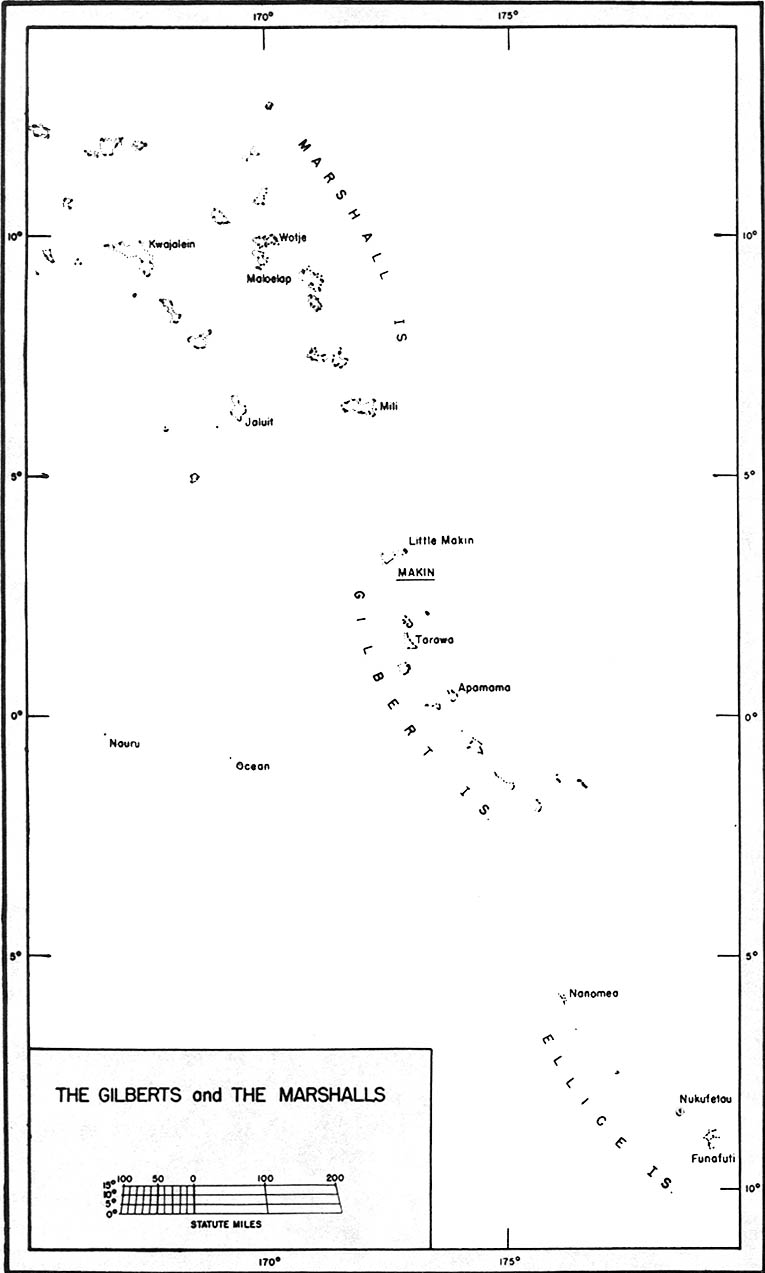

BEFORE DAWN ON 20 NOVEMBER 1943, an assemblage of American military might lay waiting off the western shore of Makin, northernmost atoll in the Gilbert Islands (Map No. 2, page 2). A strong task force, with transports carrying men of the U. S. Army, was about to commence the assault on Makin. Off Tarawa, about 105 miles to the south, an even larger force of U. S. Marines was poised in readiness to seize the airfield and destroy the Japanese there. From points as distant as the Hawaiian Islands and New Zealand, and by several different routes, the separate elements of this armada had gathered to carry out our first aggressive mission in the Central Pacific. The attack upon Makin would be the first seizure of an atoll by an Army landing force.

Invasion of the Gilbert Islands brought the war in the Central Pacific to a new phase. After almost two years of defense, of critical engagements like the Battle of Midway (3-6 June 1942) and hit-and-run raids like those against Makin (17 August 1942) and Wake Island (24 December 1942), the United Nations were taking the offensive. They were to do in that area what had been done for a year in the Southwest Pacific. The attack upon the Gilberts was for the Central Pacific the counterpart of that upon the Solomons (7 August 1942) in the Southwest Pacific. Japanese-held bases were to be recovered and used against the enemy in further strikes toward the heart of his empire. (Map No. 1, opposite.)

For almost a year after the Battle of Midway, the strength of the United Nations had permitted aggressive action in only one Pacific area at a time. Then, in the Aleutians, Attu had been seized in May 1943, and Kiska had been occupied in August, while the Japanese were also being driven from their bases in the Solomons and New Georgia. With the threat to the western coast of Canada

1

2

and the United States removed, force became available for simultaneous campaigns in Bougainville and the Gilberts. On 1 November, the hard battle for Bougainville was opened; at the same time, the expedition to the Gilberts was starting on its mission, We were ready to dear what Admiral Chester W. Nimitz called "another road to Tokyo."

The Gilberts straddle the equator some 2,000 miles southwest of Oahu (Map No. 2, page 2). Most of them are low, coral atolls, rising a few feet from the sea, supporting coconut palms, breadfruit trees, mangroves, and sand brush. Two genuine islands, Ocean and Nauru, were included in the days of British control in the same colonial administrative unit with the atolls, although they lay some 200 to 400 miles farther west. The Japanese seized Makin on 10 December 1941 and converted it into a seaplane base. In September 1942 they occupied Tarawa and Apamama. At Tarawa they built an air strip and collected a considerable garrison, There also they set up administrative headquarters for the naval forces in the Gilberts. On Apamama an observation outpost was established. On Ocean and Nauru Islands they also built up air bases, and from the latter extracted phosphates important in their munitions industry. Combined with these Japanese bases were others in the Marshalls to the northwest, the whole comprising an interlocking system of defense.

If the Gilberts and Marshalls were outer defenses of the conquered island empire of Japan, for Americans they were a menace to the fundamental line of communications from Hawaii to Australia. From them, the Japanese struck at our advanced staging positions, such as Canton Island and Funafuti in the Ellice Islands. From them also, Japanese observation planes could report the movements of our convoys and task forces, could direct submarines and bombers to points of interception, and thus hold in the Central Pacific area a large portion of our fighting strength to furnish adequate protection. Once the islands had come into our hands, our route to the Southwest Pacific could be shortened sufficiently to provide, in effect, the equivalent of added shipping for the transport of men and materiel.

Raids by bombers of a U. S. Navy task force brought Makin under fire in January 1942. In the following August Carlson's Marine Raiders spent an active night there destroying installations and most

3

of the small Japanese garrison. In the first nine months of 1943, Seventh Air Force planes harassed the Japanese in the Marshalls and Gilberts and measured their growing strength. While American forces were pursuing this program of harassment, their power to strike aggressively was also growing.

It was apparent to the joint Chiefs of Staff by July 1943 that our war potential had reached a level permitting more than neutralizing raids against the islands; we could attempt to take them. On 20 July they sent orders to the Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Ocean Areas, covering operations in the Ellice and Gilbert Islands groups, including Nauru. They estimated that enough amphibious and ground forces would be available, without hampering the operations already under way in the South and Southwest Pacific, or delaying those projected for early in 1944 against Wewak, Manus, and Kavieng. Two Marine divisions and one Army division, with supplementary defense and construction troops, and a considerable surface force, were deemed necessary. The target date was set tentatively for 15 November, contingent upon ability to gather naval forces from the North and South Pacific and assault shipping from the North Pacific in time.1 Strategically this attack would aid operations elsewhere by putting the enemy under pressure in a new area, and it would secure our lines of communication to the Solomons; as the joint Chiefs of Staff set forth its purposes, it would also be of help in gaining control of the Marshalls in the following January.

The command was to be as specified by Admiral Nimitz, Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Ocean Areas. Planning and organization for a series of operations in the Central Pacific Area began at once. A force uniting land, sea, and air power in flexible proportions, adapted to the successive requirements of a series of island conquests, was constituted.2 From base to beaches, the Navy would transport and protect the troops, and it would support their subsequent operations by naval gunfire and carrier-based planes. Troops for the assault and others for the garrisons which would convert captured islands to American bases were to be drawn from both the Marines and the Army. The troops were to be organized as the V Amphibious Corps.

1. This was just before the action at Kiska.

2. The V Amphibious Force, under naval command, was that which operated

in the Central Pacific Area.

4

Preparations were initiated for an attack upon the Gilberts, an operation in which the organization would receive its first test in combat. When this operation had succeeded, other campaigns would extend the road to Tokyo further to the northwest. The route would run via Kwajalein, Eniwetok, Saipan, and Guam, to Iwo Jima, Okinawa, and beyond. The Gilberts were only the first barrier to surmount; the goal was Tokyo itself.

5

MAJ. GEN. RALPH C. SMITH, Commanding General, 27th Infantry

Division, United States Army, and of the landing forces at Makin.

6

page created 9 November 2001