Cover: Taking a Salteador Stronghold (West Point Museum Art Collection, U.S. Military Academy)

The Mexican War (1846-1848) was the U.S. Army's first experience waging an extended conflict in a foreign land. This brief war is often overlooked by casual students of history since it occurred so close to the American Civil War and is overshadowed by the latter's sheer size and scope. Yet, the Mexican War was instrumental in shaping the geographical boundaries of the United States. At the conclusion of this conflict, the U.S. had added some one million square miles of territory, including what today are the states of Texas, Arizona, New Mexico, and California, as well as portions of Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, and Nevada. This newly acquired land also became a battleground between advocates for the expansion of slavery and those who fought to prevent its spread. These sectional and political differences ripped the fabric of the union of states and eventually contributed to the start of the American Civil War, just thirteen years later. In addition, the Mexican War was a proving ground for a generation of U.S. Army leaders who as junior officers in Mexico learned the trade of war and latter applied those lessons to the Civil War.

The Mexican War lasted some twenty-six months from its first engagement through the withdrawal of American troops. Fighting took place over thousands of miles, from northern Mexico to Mexico City, and across New Mexico and California. During the conflict, the U.S. Army won a series of decisive conventional battles, all of which highlighted the value of U.S. Military Academy graduates who time and again paved the way for American victories. The Mexican War still has much to teach us about projecting force, conducting operations in hostile territory with a small force that is dwarfed by the local population, urban combat, the difficulties of occupation, and the courage and perseverance of individual soldiers. The following essay is one of eight planned in this series to provide an accessible and readable account of the U.S. Army's role and achievements in the conflict.

This brochure was prepared in the U.S. Army Center of Military History by Stephen A. Carney. I hope that this absorbing account, with its list of further readings, will stimulate further study and reflection. A complete list of the Center of Military History's available works is included on the Center's online catalog.

| JOHN S. BROWN Chief of Military History |

The Occupation of Mexico

May 1846-July 1848

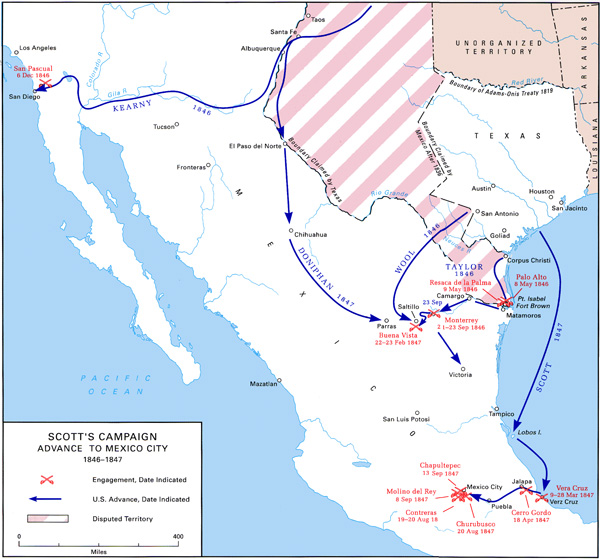

The Mexican War altered the United States and its history. During eighteen months of fighting, the U.S. Army won a series of decisive battles, captured nearly half of Mexico's territory, and nearly doubled the territories of the United States. Initially, three U.S. Army forces, operating independently, accomplished remarkable feats during the conflict. One force-under Brig. Gen. Zachary Taylor-repelled initial Mexican attacks at Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma, north of the Rio Grande. Subsequently, Taylor's force crossed the river and advanced into northern Mexico, successfully assaulted the fortified town of Monterrey, and-although heavily outnumbered-defeated Mexico's Army of the North at Buena Vista.

Concurrently, Col. (later Brig. Gen.) Stephen W Kearny led a hardened force of dragoons on an epic march of some 1,000 miles from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, across mountains and deserts to the California coast. Along the way, Kearny captured Santa Fe in what is now New Mexico and, with the help of the U.S. Navy and rebellious American immigrants, secured major portions of California.

Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott directed the third and decisive campaign of the war. Scott's army made a successful amphibious landing from the Gulf of Mexico at the port of Veracruz, which was captured after a twenty-day siege. Scott then led his army into the interior of Mexico with victories at Cerro Gordo, Contreras, Churubusco, Molino del Rey, and Chapultepec, ending the campaign and ultimately the war with the seizure of Mexico City.

The conflict added approximately one million square miles of land to the United States, including the important deep-water ports of coastal California, and it gave the Regular Army invaluable experience in conventional operations. Yet, the Mexican War consisted of more than a series of conventional engagements, and no formal armistice was reached until long after the capture of Mexico City. Rather, the Army had to conduct a "rolling occupation," thereby serving as administrators over the captured territory as the Army's frontline units continued to pursue conventional Mexican forces.

Incidentally, by definition, "Territory is considered occupied when it is actually placed under the authority of the hostile army. The occupation extends only to the territory where such authority has been established and can be exercised" (as defined in U.S. Army Field Manual 27-10 and

3

based on Article 42 of the Hague Convention of 1907). Thus, the Army found itself facing the more difficult mission of occupying a foreign country with a small force while battling capable and highly motivated guerrillas.

The U.S. Army designated small bodies of armed Mexicans who fought an irregular war against the Americans as "guerrillas." Guerrilla, a term based on the Spanish word for small war, was initially used during Napoleon's Peninsula War, 1808-14, to describe Spanish irregulars fighting the French. Army commanders also used the Mexican term rancheros to describe guerrillas. In the current study, the terms guerrillas and irregulars are used interchangeably.

Both the occupation and the insurgency reflected existing sociopolitical realities of Mexico. Indeed, the country's deep and often violent racial, ethnic, and social divisions further complicated the task of the occupying forces. Regional variations between northern and central Mexico, differences between the composition of Zachary Taylor and Winfield Scott's armies and the threats they faced, and-not least the great difference in policies pursued by the two commanders meant that the U.S. Army conducted not one but two very different occupations in Mexico during 1846-48.

Numerous factors affect the nature and structure of occupation as a military mission. The strategic and long-term goals of any occupier will shape the occupation policy. This policy should work toward an anticipated end state, which can run the spectrum from annexation to the restoration of independence.

An occupying force faces several essential duties and the possibility of collateral missions. Primary responsibilities include enforcing the terms of the instrument ending conventional hostilities, protecting occupation forces, and providing law and order for the local population. Collateral missions may include external defense, humanitarian relief and in some cases-nation-building, which can be the creation of an entirely new political and economic framework. Economic conditions, demographics, culture, and political developments all come into play and affect occupation policy.

Mexico's Political and Social Situation at the Onset of Hostilities

Race and ethnicity greatly affected the history and development of Mexico. The descendants of native American Indians, who had

4

inhabited the region before the arrival of the Spanish in 1519, greatly outnumbered those of European ancestry. Even before Mexico achieved its independence in 1821, Spaniards and the criollos, or Mexican-born Spaniards, made up only 20 percent of Mexico's population but controlled the country's government and economy. The remainder comprised Indians and mestizos, the latter group being of mixed European and Indian heritage. Criollo control continued after independence.

Although the Mexican population was divided along cultural, economic, and racial lines, the criollos themselves were split between conservative and liberal factions. Conservatives advocated installing a strong centralized government, having Catholicism as the official state religion, and limiting voting rights to the privileged few. Liberals proposed granting additional powers to Mexico's states, defended religious toleration, and supported the expansion of voting rights. To complicate the political scene, the liberals further subdivided themselves into purist and moderate factions, each with different agendas. As a result, the government in Mexico City remained in a seemingly constant state of disarray that contributed to economic stagnation and an ever-growing national debt.

At the onset of the conflict with the United States, the Mexican government was, in theory, a representative democracy. The Constitution of 1824 had created a federal system modeled on the U.S. Constitution. The Mexican federal government was composed of three branches: an executive branch with a president and vice president; a legislative branch, or general congress, comprising two houses-a senate and house of representatives; and a judicial branch with a supreme court and local circuit courts.

In theory, the executive and legislative officials were elected through popular vote, but, in reality, only a small fraction of Mexico's population actually had the right to vote. In 1846, for example, less than 1 percent of Mexico City's population of some 200,000 met the property requirement necessary to vote. Even smaller portions of the population in outlying regions were able to vote. The ruling elite refused to extend suffrage to the remainder of the population and cautiously guarded its power and land holdings, which further alienated the Indians and mestizos. As a result, rebellions were common in Mexico. In 1844, for example, a revolt against the central government led by Gen. Juan Alvarez soon turned into an Indian insurrection that spread a swath of destruction across 60,000 square miles of southwestern Mexico centered on Acapulco. Although the Mexican Army mercilessly repressed such outbreaks, underlying tensions seethed close to the surface as the war flared along the Rio Grande in May 1846.

5

6-7

Mexico itself comprised more than twenty separate states, although that number fluctuated over time. State and local governments were organized in the same manner as the federal government. In fact, the criollos dominated Mexico at the state (provincial) and territorial level just as they did in the national capital. The provincial governments paid homage to the federal authority in Mexico City, but political instability and the distance between the capital and many of the states enabled the provincial governments to enjoy a wide degree of autonomy. As a result, U.S. forces conducted much of their negotiations with state and local governments early in the war and had no real opportunity to deal with the central government until Scott launched his campaign against Mexico City. In sum, the country's governing bodies were unprepared to deal with either internal or external crises.

In 1845, Mexico's borders included more than one-third of the North American continent, with a population of slightly more than seven million people. North of the Rio Grande, Mexico's holdings extended from the western borders of Texas and the Arkansas River in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west (Map 1). The holdings included more than one million square miles of land in what today are the states of Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming. The geography of this sparsely populated territory included portions of the jagged Rocky Mountains and Sierra Nevada, the craggy Intermountain region, and the rugged Coast Range. In addition, stretches of largely uninhabited desert contrasted with potentially valuable agricultural assets such as California's Central Valley.

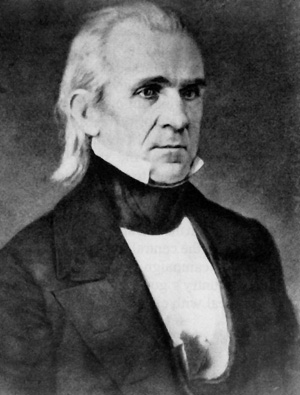

Those territories attracted the intense interest of many Americans, including President

7

President James K. Polk (Library of Congress)

James K. Polk and his administration, which had several clearly defined goals at the onset of the Mexican War. Polk wanted to settle the disputed southern boundary between Texas and Mexico. Ever since winning independence from Mexico in 1836, the Republic of Texas had insisted that the Rio Grande constituted the border separating it from Mexico. Mexico, however, set the line some 150 miles north at the highlands between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande. When the United States accepted Texas's application for statehood in December 1845, it inherited the Texan claim.

The United States also coveted Mexico's lands north of the Rio Grande to support its rapidly growing population of approximately eleven million by 1840. Looking westward to expand, the nation justified

8

its demand for land with the concept of Manifest Destiny, a belief that God willed it to control the entire North American land mass. More than the perceived will of God, however, was involved. Economics also played a central role in the concept. American explorers in California had reported deep-water ports along the west coast, valuable departure points when the United States sought to open trade between its own growing industries and lucrative markets in Asia. In an attempt to settle Texas border questions and to secure California, the U.S. government had offered several times between 1842 and 1845 to purchase both regions from Mexico. Mexico City refused all overtures because Mexican popular opinion insisted that the government preserve all of the territory that the nation had wrested from Spain.

When the war officially began on 8 May 1846, President Polk had a clear set of objectives for the U.S. Army. Secretary of War William L. Marcy, writing for the president, ordered General Taylor's force of some 4,000 Regulars-or just under half of the entire U.S. Army-to seize as much territory in northeastern Mexico as possible. Meanwhile, Marcy sent Kearny's force through New Mexico and into California with instructions to cut those regions off from the central government in far-off Mexico City. Polk and Marcy believed that the Mexican government would not resist an offer to purchase the territory if U.S. military forces already controlled it.

Organized along European lines, the standing U.S. Army, designated the Regular Army, contained specialized corps of infantry, cavalry, artillery, and engineers. At the outbreak of the conflict, it numbered only 7,365 soldiers. In compliance with its missions of guarding the frontier and defending the nation's coastline, the Army had scattered its units in small posts manned by units of company size or less across the eastern seaboard and through the interior frontier. Because entire regiments rarely assembled, the force seldom practiced large-unit tactics.

The core of the Army consisted of its eight infantry regiments, which consisted of ten companies each. On paper, each company possessed fifty-five men, but at the onset of the war most averaged only thirty-five. Brigades consisted of an ad hoc collection of multiple regiments, and divisions contained several brigades. Those larger formations were temporary wartime organizations.

Infantrymen in the American Army enlisted for five years and received an average pay of $7 per month. Offering low wages and harsh discipline, the service attracted the poorly educated and those with few opportunities in civilian life. In 1845, 42 percent of the Army consisted

9

of foreign nationals; 50 percent were Irish and the rest were from other European nations.

The cavalry of the U. S. Regular Army consisted of two light regiments trained and designated as dragoons, both organized into five squadrons of two companies each. Trained to fight mounted or dismounted, dragoons were always scarce and difficult to expand in a timely fashion. Their training and equipment were deemed too expensive in terms of time and money to justify increasing the numbers. The Army's lack of such highly mobile troops was evident throughout the conflict.

The Army's artillery arm was more robust. It contained a mixture of 6-pound field artillery, as well as 12-, 18-, and 24-pound coastal defense weapons. Howitzers firing shells of 12-, 24-, and 32-pound weight added to the Army's arsenal. In Mexico, the Army would use primarily light artillery against guerrilla forces. At full strength, American light field artillery companies had three two-gun sections and came with a large number of horses to transport the guns, ammunition, and most of their crew. Some "flying" companies had all of their troops mounted.

The U.S. Army also fielded a small number of highly trained engineers who served in either the Corps of Engineers or the Corps of Topographical Engineers. Members of the former specialized in bridge and fortification construction. The latter created maps, surveyed battlefield terrain, and built civil engineering projects such as roads and canals.

Soldiers from the Ordnance, Subsistence, and Quartermaster Departments provided logistical support. The Ordnance Department supplied firearms and ammunition, while the Subsistence Department secured bulk food items, such as barrels of flour, salt pork, and cured beef. Both operated in the rear along the Army's lines of communication. The Quartermasters had the greatest responsibility. They supplied troops with all equipment other than weapons, such as uniforms, horses, saddles, and tents; they also arranged transportation and oversaw construction projects; and, during the Mexican War, they created and ran a series of advanced supply depots close to field operating forces that ensured a steady flow of provisions and equipment to the troops. Although its long supply trains and depots sometimes became targets for Mexican irregulars and bandits, the Quartermaster Department provided the Army with one of the most advanced logistical support operations in the world.

In times of emergency, the United States called for volunteers to enlist in state-raised regiments to augment its small professional force. The use of volunteers was first established in the 1792 Militia Act. Volunteers were compelled to serve wherever the War Department required them.

10

State militia, however, could not be forced to travel beyond their home state's borders. The practice stemmed from the country's colonial history and its ideological aversion to standing armies as a threat to republican liberties, a prejudice bequeathed by European colonists and the Revolutionary War generation. When necessary, Congress gave the War Department permission to request a specific number of regiments from each state. State governors then issued calls for volunteers and named a time and place for the volunteers to gather. Once raised, the men were organized into companies, battalions, and regiments. Regiments elected their own officers, although governors sometimes selected field and staff grade officers. The president appointed all volunteer generals, who were then confirmed by Congress. After the regiments were organized, they "mustered" into federal service and came under War Department's control. They were not, however, governed by the 1806 Articles of War, the basis for the American military justice system, a situation that gave them much more autonomy than the Regular Army enjoyed. During the Mexican War, some 73,260 volunteers enlisted, although fewer than 30,000 actually served in Mexico.

The U.S. forces' reliance on volunteer soldiers complicated matters. Because volunteers were taken directly from civilian life and quickly thrown into a rigid hierarchal system, many responded poorly to the regimentation of military life. At their worst, they resented superiors, disobeyed orders, balked against the undemocratic nature of military life, and proved difficult to control. They rarely understood and generally ignored basic camp sanitation, and they were generally unaccustomed to the harsh life faced by soldiers in the field. Not surprisingly, they experienced much higher death rates from disease and exposure than the Regulars. The officers of those regiments often held their rank by virtue of political appointment or through election by those who became their subordinates. This system offered no assurance that those who initially commanded possessed the ability or the training to lead. One senior Army officer concluded: "The whole volunteer system is wholly indebted for all its reputation to the regular army without which the [illegible] body of volunteers in Mexico would have been an undisciplined mob, incapable of acting in concert, while they would have incensed the people of Mexico by their depredations upon persons of property."

Swept by "war fever," the men who initially rushed to join Taylor's army in northern Mexico exemplified the worst characteristics of the lot. As a group, the early volunteers were vehement racists, vocal exponents of Manifest Destiny, and eager to fight and kill Mexicans-any Mexicans. They had little patience with the hardships of camp

11

life, strict codes of discipline, hot Mexican sun, prohibitive rations, or boredom of garrison duty. Drunkenness flourished because alcohol provided an easy escape for men who found the normal day-to-day routine of soldiering far removed from their dreams of adventure and military glory. Brawls fueled by gambling, regional rivalries, and general boredom were common. Violent confrontations between the ill-trained American soldiers and Mexicans were also frequent.

Volunteers who arrived later in the war knew better what to expect and proved less unruly. In addition, commanders gradually found ways to control and occupy their new soldiers, which lessened their onerous effect on the Mexican citizenry. During the final months of the conflict, most of the volunteer troops conducted themselves with greater self- restraint in camp and proved quite effective on the battlefield.

Throughout the war, both Taylor and Scott also relied heavily on special companies of mounted volunteers: the Texas Rangers, who acted as the eyes and ears of the Army by conducting crucial reconnaissance, collecting intelligence, and carrying messages through Mexican lines. They also launched raids against specific targets, especially guerrilla encampments. Technically state militia and not mustered into federal service, the Texans voluntarily agreed to serve in Mexico. Their depredations on the Mexican citizenry were often excessive, however, and their behavior, along with that of other volunteers, did much to spark local Mexican resistance.

U.S. Army Counterinsurgency Doctrine

The U.S. Army had no official doctrine covering occupation or counterinsurgency operations in 1846. In the absence of formalized manuals, its professional soldiers instead passed on informal doctrine that was based on traditions and experiences from one generation of officers to the next through personal writings and conversations. Little of it applied directly to the situation the troops encountered during the Mexican War. For example, American forces had no experience in the control of foreign territory other than a winter's occupation of portions of Quebec Province during the American Revolution and some brief forays into Canada during the War of 1812. In 1813 during a three-day sojourn in York, the Canadian capital, American troops had looted and then set fire to large portions of the town and its harbor. This unhappy precedent, the product of poor discipline and heavy losses, possessed more relevance in 1846 than some American commanders chose to acknowledge.

The volunteers' actions during the various Indian Wars also bequeathed a mixed heritage. The Second Seminole War (1835-42),

12

Texas Ranger (Library of Congress)

which pitted the Army against some 1,500 Seminole and African-American warriors in the Florida Everglades provided a particularly relevant example. The Seminoles used their knowledge of the nearly impenetrable Florida swamps to conduct ambushes whenever possible. In response, the Army shunned conventional tactics, such as trying to coordinate several converging columns over virtually impassible terrain, and adopted an unconventional approach. Commanders established a series of heavily garrisoned posts to protect white settlements and to limit the Seminoles' ability to move with impunity. They also began active patrolling from those posts to find and destroy Indian villages and crops, as well as Indian war parties whenever possible. The tactics were both brutal and effective. Generals Taylor and Scott would apply similar measures during the occupation of Mexico.

13

Mexico's Guerrilla Tradition and Composition of Irregular Forces

In 1846, most Americans knew little about Mexican society, culture, or history. They did not realize that guerrilla warfare formed a central part of Mexico's military tradition throughout the nineteenth century. During Mexico's War for Independence, the poorly equipped rebels often resorted to hit-and-run tactics by mounting small-unit attacks on Spanish military detachments and the long supply trains that equipped them.

Expert horsemen, Mexican guerrillas usually fought while mounted. Heavily armed with rifles, pistols, lances, sabers, and daggers, they showed particular skill with lassos and preferred to rope their victims and drag them to death when possible. They mastered the local terrain and had the ability to use complex networks of paths, trails, and roads to strike the unwary and then to disappear into the countryside. Fortunately for the Americans, many guerrillas doubled as thieves who failed to differentiate among their victims and often attacked their own countrymen for personal gain. Although the general population sometimes supported them, many Mexicans tired of their attacks and occasionally worked with the Americans to stop them.

The Mexicans also employed irregular cavalry units, often raised from local ranchers and commanded by regular troops. In modern military terms, those forces would be designated as partisan fighters. "Partisan" describes organized guerrilla bands fighting under Mexican regular officers or officially sanctioned by the Mexican government. The term "partisan" did not enter the U.S. Army lexicon until 1863 in General Order No. 100, which differentiated between armed prowlers, guerrillas, and partisans. The term is appropriate in the current study, however, because there was considerable partisan activity during the conflict, especially in central Mexico.

Although not officially part of the Mexican Army, the partisan cavalry often operated under close supervision of the regular army. Although Generals Antonio Canales and Jose Urrea were the best- known partisan leaders in northern Mexico, the Mexican government devoted considerable attention to raising partisan forces to harass the U.S. Army on its march toward the capital. Aware that Scott's long supply line and the attitude of the civilians along this route were key to the success or failure of the American campaign, the leadership in Mexico City decided to disrupt convoys carrying ammunition and other supplies and to otherwise harass American forces. On 28 April 1847, just ten days after the Mexican defeat at Cerro Gordo, a newly installed

14

Mexican guerrilla (Colección Banco Nacional de México)

president of Mexico and adviser to Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna-the enigmatic Mexican strongman-Pedro Maria Anaya, ordered the creation of a series of volunteer Light Corps to attack Scott's line of communications. Seventy-two Mexicans, most wealthy and twenty-one of them military officers on active service, received permission to raise the units. Brig. Gen. Jose Mariano Salas, a close friend of Santa Anna, played a prominent role in the effort. Terming the units "Guerrillas of Vengeance," Salas recruited volunteers by vowing that he would "attack and destroy the invaders in every manner imaginable," under the slogan "war without pity, unto death."

The units in the corps were designed to target supply and replacement convoys, small parties of American troops, and stragglers.

15

They used a variety of tactics. The larger forces operated as cavalry units, which sought to engage quickly, to inflict maximum casualties, and then to disappear rapidly. The smaller units made extensive use of sharpshooters who concealed themselves in the trees and chaparral that lined the Mexican National Highway, which Scott's forces would use extensively. Imposing terrain features along most of the route's length worked to the advantage of the partisans.

Because of Mexico's immense size and population, the U.S. Army in reality occupied only a small area that encompassed key population centers along Mexico's lines of communication. This arrangement was necessitated by the fact that the U.S. Army never maintained more than 30,000 troops in Mexico during the entire war. The Polk administration expected this handful of soldiers-less than 0.4 percent of the total population of Mexico-to pacify some 7 million Mexicans. During the Mexican War, the United States occupied two regions of Mexico proper. Taylor and Scott occupied more than a thousand square miles of northern and central Mexico, respectively. Brig. Gen. Stephen W Kearny's troops did occupy a third area north of the Rio Grande-what today is New Mexico and California-but large numbers of Americans had already filtered into those regions and the United States did not intend to return either one to Mexican control. In addition, the areas of Mexico occupied by Kearny's troops contained only 90,465 inhabitants as of the 1842 census. Of those, a significant number were U.S. settlers. Such a small number of civilians possessed far less potential for troubling a U. S force than did the millions of their countrymen who lived to the south. In addition, the area was already closely tied to the United States economically through well-established trade routes. The situation in those areas, therefore, was markedly dissimilar to what confronted Taylor and Scott in Mexico proper, which had little indigenous support for annexation. Because there were no significant guerrilla actions against Kearny, and he quickly integrated New Mexico and California into the United States, this study will not explore his occupation.

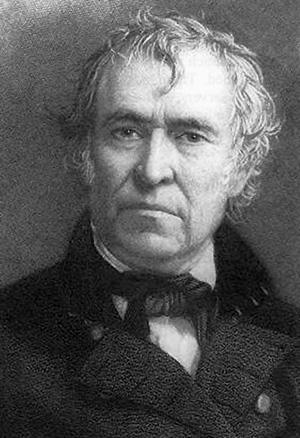

Unique circumstances and personalities produced wildly different types of occupation in Mexico. Zachary Taylor, known to his troops as "Old Rough and Ready" for his casual demeanor and willingness to share his soldiers' hardships, often neglected troop discipline. Winfield Scott, nicknamed "Old Fuss and Feathers" for his attention to detail and fondness for pompous uniforms, insisted on strict adherence to rules and regulations.

16

Taylor's Occupation of Northern Mexico

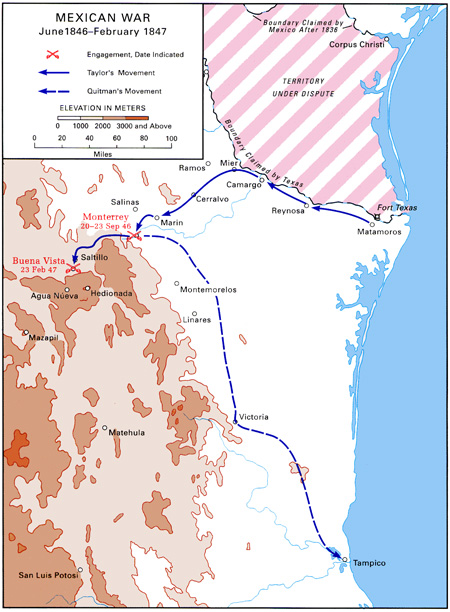

Zachary Taylor's occupation of northern Mexico began on 12 May 1846 when his troops crossed the Rio Grande and took the town of Matamoros unopposed. As the war progressed, Taylor extended his holdings. First, he gained control of Camargo, some eighty miles upstream from Matamoros, and then he went southward to Monterrey and eventually to Saltillo, approximately 140 miles southwest of Camargo (Map 2). The Saltillo to Camargo line became one of the most important supply and communications routes in the north. By war's end, Taylor's forces controlled a region extending as far as Victoria to the southeast and Parras to the west.

Taylor quickly achieved the purely military objectives that the Polk administration assigned him. Within four months, he won decisive battles at Palo Alto, Resaca de la Palma, and Monterrey, thereby forcing Mexico's Army of the North to withdraw some 400 miles south from the Rio Grande to San Luis Potosi. Taylor's occupation of northern Mexico, however, did not compel Mexico's government to sell any of the territories sought by the United States as President Polk had hoped. In fact, the situation in northern Mexico deteriorated rapidly in response to the local depredations of the volunteer troops.

Until June 1846, Taylor's army consisted of Regular Army troops who enjoyed some popularity with the citizenry. Matamoros's citizens held the American force in higher esteem than they did the Mexican Army, which had abandoned all of its wounded when it retreated from the town. The U.S. Army had immediately set up hospitals to minister to the sick and wounded and had provided for the basic needs of the townspeople.

The dynamic changed when volunteers moved into the area and immediately began raiding the local farms. As the boredom of garrison duty began to set in, plundering, personal assaults, rape, and other crimes against Mexicans quickly multiplied. During the first month after the volunteers arrived, some twenty murders occurred.

Initially, Taylor seemed uninterested in devising diversions to occupy his men and failed to stop the attacks. As thefts, assaults, rapes, murders, and other crimes perpetrated by the volunteers mounted and Taylor failed to discipline his men, ordinary Mexican citizens began to have serious reservations about the American invasion. Taylor's lackadaisical approach to discipline produced an effect utterly unanticipated by the Polk administration, many of whose members, particularly pro-expansionists such as Secretary of the Treasury Robert J. Walker, believed that Mexicans would welcome the Americans as liberators. Instead, public opinion turned against the Americans

17

and began to create a climate for guerrilla bands to form in the area. Mexicans from all social backgrounds took up arms. Some of them were trained soldiers; others were average citizens bent upon retaliating against the Americans because of attacks against family members or

18

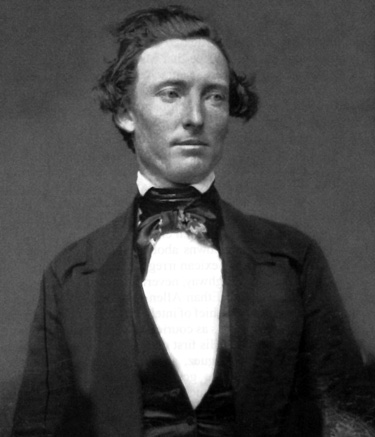

Zachary Taylor (Library of Congress)

friends. Criminals joined in, and bandits and highwaymen began to flourish, looking for easy prey.

As Taylor's force moved up the Rio Grande and its lines of communications extended, irregulars began to capture and kill stragglers, the sick, and the wounded who fell behind on long marches.

The local populace increasingly appeared more than willing to support and shield the guerrillas. The volunteers' racism, anti-Catholcism and violence provided all the motive that locals needed to oppose the

19

American advance. Guerrilla attacks grew more frequent after the battle for Monterrey, when Brig. Gen. William J. Worth, the new military governor of the city, discontinued military patrols in the town for a short time, allowing a bloodletting to occur.

Taylor appointed officers to serve as military governors of all major towns that he occupied. Each military governor had authority to make whatever rules he wished. There was no official military governing policy at the time. Observers estimated that volunteer troops killed some 100 civilians, including many who had been killed by Col. John C. Hays' 1st Texas Mounted Volunteers. A few weeks later, apparently in retaliation, Mexicans killed a lone soldier from a Texas regiment just outside Monterrey. Rangers under Capt. Mabry B. "Mustang" Gray responded by killing some twenty-four unarmed Mexican men. The event galvanized much of the population against Taylor's Army of Occupation.

The boredom of occupation duty led to additional waves of violence. During November 1846, for example, a detachment from the 1st Kentucky regiment shot a young Mexican boy, apparently for sport, and Taylor again failed to bring any of the guilty soldiers to justice.

The most concerted and organized irregular campaign in northern Mexico began in February 1847, during the initial phase of the battle for Buena Vista, and it lasted nearly a month. As Taylor repositioned his troops around Saltillo to contest Santa Anna's advance, the Mexican commander sent a detachment of partisan cavalry under General Urrea to sever the Monterrey-Camargo road, Taylor's line of communication to the Gulf coast. Urrea's cavalry joined forces with General Canales' force of partisan irregulars, which had been active in the region since the onset of hostilities the previous spring. Urrea was determined to strike isolated garrisons and Taylor's lightly defended supply trains. As Taylor's lines of communications had lengthened and become more difficult to defend, his supply convoys had become attractive targets for guerrillas, a vulnerability that he failed to recognize.

On 22 February, Urrea's mounted guerrillas attacked a wagon train containing some 110 wagons and 300 pack mules just five miles outside the undefended hamlet of Ramos, which was some seventy-five miles northeast of Monterrey. While a portion of the attackers surrounded the train's guards posted at the front of the column, others went directly for the wagoneers. During the short skirmish, Urrea's men killed approximately fifty teamsters, drove off the survivors, forced the guards to surrender, and captured most of the supplies.

The partisan commander next gathered up the undamaged wagons and mules and moved on to attack the American garrison at Marin,

20

arriving late that evening. Two companies from the 2d Ohio under the command of Lt. Col. William Irvin-some 100 men-defended the town. They held the irregular cavalry at bay until 25 February when a small relief column finally arrived. Low on supplies, the troops abandoned Marin and moved back toward Monterrey. Unknown to Irvin and his rescuers, the rest of the 2d Ohio, commanded by Col. George W. Morgan, was marching south toward Marin from Cerralvo. Along the way, they picked up some twenty-five survivors of the initial "Ramos Massacre." Arriving in Marin soon after Irvin left, Morgan ordered his men to continue south after midnight on the morning of 26 February, when a number of Urrea's lancers attacked them just outside the town. When Morgan sent a messenger to Monterrey for reinforcements, his courier came upon Irvin's column marching southward. In response, Irvin and 150 of his men turned back to join forces with Morgan, and the reinforced column reached Monterrey without further incident. In the end, Morgan and Irvin estimated they had killed some fifty partisans while suffering five wounded and one killed. Urrea's force, however, effectively closed the route between the Rio Grande and Monterrey.

Defense of supply convoy (Library of Congress)

21

Finally recognizing the seriousness of the guerrilla threat, Taylor organized a column of mixed arms under Maj. Luther Giddings to run the gauntlet to Camargo. It consisted of about 250 infantrymen, a section of field artillery, and approximately 150 wagons. Giddings left Monterrey on 5 March and by midafternoon on the 7th had come within one mile of Cerralvo, a small town fifty miles southwest of Camargo. When local citizens warned him of an impending attack, he quickly parked the train and organized his men into a defensive perimeter.

The initial guerrilla assault failed to break through Giddings's line but succeeded in destroying about forty wagons and killing seventeen American civilian teamsters and soldiers. Strengthened by a relief column from Camargo the following day, the Giddings column reached Camargo without further incident.

Next, Taylor sent Col. Humphrey Marshall's 1st Kentucky cavalry regiment northward from Monterrey to locate the guerrilla force. Marshall soon reported that Urrea was again near Marin. In response, Taylor organized a brigade of dragoons, Capt. Braxton Bragg's battery, and Col. Jefferson Davis's 1st Mississippi Rifles and personally led it to Marin. Joining Marshall early on the morning of 16 March 1847, Taylor sent a portion of the force to guard a supply train moving out of Camargo while the rest of the force pursued Urrea. Although the Americans failed to engage the guerrilla leader, their presence in such large numbers made further organized partisan operations against U.S. supply routes in the region impossible. Subsequently, Urrea retired southward toward San Luis Potosi, allowing Taylor to reopen his supply lines to the Rio Grande. To prevent similar situations from recurring, Taylor continued to send mixed armed groups with each convoy. He also positioned additional units at various garrisons along his lines of communication and sent "Mustang" Gray's Texas Rangers to operate in the area. The Rangers hoped either to find and eliminate the guerrillas or to terrorize the local people to such an extent that they would stop supporting the irregulars. Such measures were only partially successful.

On 4 April 1847, General Canales called on all Mexicans to take up arms against the Americans and threatened to execute as traitors any who refused. Guerrilla attacks increased through the summer and into the fall of 1847. A large partisan force raided the supply depot at Mier, some 180 miles northwest of Matamoros, on 7 September, carrying off some $26,000 worth of supplies. A hastily organized party of dragoons and civilian teamsters caught the irregulars, who were slowed considerably by their plunder, allowing the Americans to reclaim their supplies after killing some fifteen of the enemy.

22

By early November 1847, the guerrillas changed their tactics. The strong American presence in convoys and at various garrisons made attacking those targets less attractive. Instead, the guerrillas focused on ambushing small detachments patrolling the countryside. Outside Marin, for example, a large force of guerrillas under Marco "Mucho" Martinez engaged a detachment of dragoons commanded by 1st Lt. Reuben Campbell. This time, the dragoons fought their way through the enemy line and killed Martinez, whom Taylor had labeled "the most active of the guerrilla chiefs on this line."

A few days after Martinez's death, Texas cavalrymen found and raided a guerrilla camp near Ramos, about fifty miles to the north and west of Camargo, killing two more irregulars and capturing a large number of horses and mules, as well as arms and other equipment. Those two victories helped curb the violence that had been common along the Rio Grande since the previous May.

American commanders finally supplemented tactical measures with more enlightened policies to reduce violence against civilians. Bvt. Maj. Gen. John E. Wool, the military governor of Saltillo, instituted strict curfews, moved garrisons out of city centers, set up road blocks to keep soldiers away from populated areas, and threatened to discharge any unit whose members indiscriminately slaughtered Mexican livestock or plundered from the locals. Although conditions improved somewhat, violent crimes against Mexican citizens continued. In fact, Taylor himself announced that he would hold local governments responsible for U.S. Army goods destroyed in their jurisdiction and would lay "heavy contributions ... upon the inhabitants," a punitive policy that was effective.

Taylor and Wool also decided to organize Mexican police forces into a lightly armed constabulary that was responsible for particular regions. Raised from local citizens, the units were to "ferret out and bring to the nearest American military post for punishment ..." any guerrillas or their supporters. Although the units' actions against Comanche Indian raiders along the Rio Grande enhanced their local popularity, the units had little effect on guerrilla operations.

Frustrated in September 1847, Taylor granted General Wool the authority to try any Mexicans "who commit murder and other grave offences on the persons or property ..." of the American Army of Occupation. Based on a similar order that General Scott had issued in central Mexico, the measure governed military tribunals in the area under the general's jurisdiction and essentially placed the region under military law.

In December, Secretary of War Marcy reinforced the harsh measures by directing that local authorities turn guerrillas over to the Americans.

23

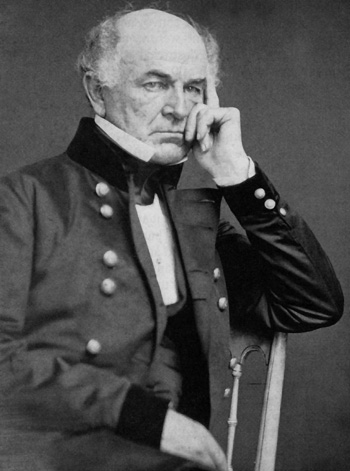

John E. Wool (National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution)

If they failed, then the Army had the authority to hold entire towns responsible for any violence that took place in surrounding areas. Any Mexicans who provided material support to guerrillas would not only pay fines but also forfeit all personal possessions. The measures worked. Within a few months, Wool collected more than $8,000 in fines, as well

24

as livestock and other personal property. By the end of 1847, attacks in northern Mexico had dropped off considerably.

Wool took command of Taylor's army on 26 November 1847 when the latter returned to the United States. Shortly thereafter, Wool issued a scathing proclamation in which he stated that the war had been conducted "with great forbearance and moderation." Even so, he said, "Our civilians and soldiers have been murdered and their bodies mutilated in cold blood." As a result, anyone who "pays tribute to Canales or to any other person in command of bandits, or guerrilla parties ... will be punished with utmost severity."

Wool's final report in 1848 credited the decrease in guerrilla attacks to three basic policies. First, holding local leaders personally responsible for guerrilla activity in their jurisdictions curbed high-level support for the irregulars. Second, making localities financially accountable for U.S. government property lost in attacks made local citizens hesitant to harbor attackers. Finally, Wool contended, the use of native police forces helped forge bonds between the Army of Occupation and the local populace and allowed the Americans to collect intelligence that they would never have found otherwise. Others, however, place more emphasis on the large number of troops on security duty, their offensive operations against the partisans, and the measures taken to at least separate the volunteer troops from the civilian population.

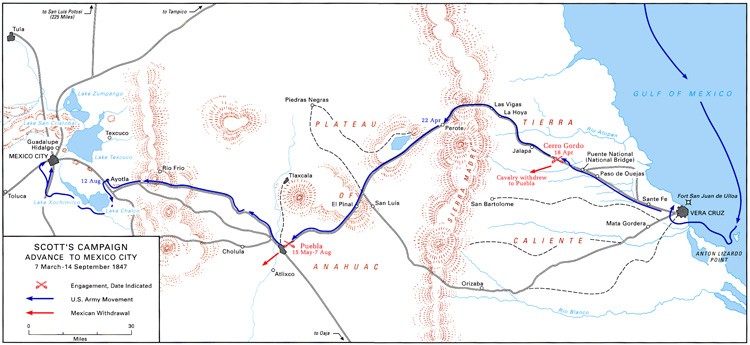

Scott's Occupation of Central Mexico

While Taylor struggled with Mexican resistance in the north after the battle at Buena Vista, Scott launched his central Mexico campaign (Map 3). In February 1847, leading elements of his invasion force seized the Gulf port town of Tampico for use as a staging point. Scott's occupation effort began at that point and ended with the American withdrawal in July 1848. By then, Scott's area of control extended some 280 miles from the port of Veracruz to Mexico City and straddled Mexico's National Highway-roughly the same route that the Spanish conquistadores had followed on their march to the Aztec capital in 1519. One of the few paved routes in Mexico, the road allowed heavy wagons to move up and down its length with ease.

From the initial planning stage in October 1846, Scott's campaign had objectives far different from those of Taylor's northern mission. By the time Scott had outlined his plans for the invasion of central Mexico, Taylor's presence in northern Mexico had clearly failed to compel the Mexicans to cede California or any of the other territory coveted by U.S. leaders. As a result, Scott intended to carry the war to

25

26-27

the heart of Mexico, capturing the nation's capital. This, he and the Polk administration reasoned, would force Mexico to accept U.S. terms.

The strategy, although well conceived and necessary to bring the war to a successful conclusion, was fraught with danger. Operating in Mexico's most populated territories, Scott's army would rarely number more than 10,000 troops at the leading edge of his advance during the entire campaign. For much of the time, Santa Anna's army outnumbered Scott's by nearly three to one. The Americans would be hard-pressed to deal with the Mexican military, let alone any civil uprisings or partisan attacks similar to those besetting Taylor. Scott understood from the beginning that he would have to secure the loyalty and respect of the local citizens or fail in his mission.

26

Scott owned an extensive personal library including works on the history of Napoleon's occupation of Spain from 1808 to 1814. In particular, Sir William Francis Patrick Napier's three-volume History of the Peninsular War guided his planning for his future campaign. Mining French experience for insights, he was struck by the rancorous conduct of the French troops toward the Spanish population and the failure of harsh French occupational measures to quash the growing uprising there. As provocations multiplied on both sides, the fighting escalated out of control. The French responded by setting fire to entire villages, shooting civilians en masse, destroying churches, and even executing priests. The locals retaliated in kind. Although the Spanish irregulars operated without any centralized command and control structure, individual

27

bands of guerrillas managed to isolate various French commands and wreaked havoc on their lines of communications. By the time an allied force under Arthur Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington, compelled the French to withdraw from Spain in 1813, Napoleon's force had seen some 300,000 men killed and wounded, compared with Napoleon's preoccupation estimate of approximately 12,000 casualties. In fact, Scott saw Wellesley's stress on strict discipline-insisting his soldiers respect personal property and meet the basic needs of Spanish civilians-as the proper model for operating in a potentially hostile land.

In light of his studies, Scott wrote his General Order No. 20, commonly known as the Martial Law Order, even before he left for Mexico. Issued at Tampico on 19 February 1847, it made rape, murder, assault, robbery, desecration of churches, disruption of religious services, and destruction of private property court-martial offenses not only for all Mexicans and all U.S. Army soldiers but also for all American civilians in Mexico. Scott closed the gap by making everyone-whether soldier, civilian, or Mexican citizen subject to the U.S. Army's jurisprudence. All accused offenders would be tried before a court made up of officers appointed by the commanding general.

Scott administered his tribunals, or commissions, in much the same way as modern courts-martial. He appointed one Regular Army officer to preside over the proceedings as judge advocate of the court. Nine other officers, usually from volunteer regiments, made up the jury. Another officer prosecuted the case, while an officer from the accused's unit served as a defender. A Regular officer defended civilians, both American and Mexican. Commissions heard one case or multiple cases over an extended period, sometimes lasting for weeks. The tribunals had the authority to determine innocence or guilt and to levy punishment, which included the lash, hard labor in ball and chain, imprisonment, branding, and even death. The commanding general-and sometimes the War Department-had to approve the most severe sentences.

The system was hardly foolproof. In one notorious case, a volunteer from the 1st Pennsylvania Regiment stood trial for theft. The accused solider had used the stolen goods, including a watch and a gold crucifix, to ensure that his compatriots would support his alibi. He had also bribed the defending officer to prevent him from exposing the deception. In the end, the soldier went free.

Scott's order closed an obvious loophole that had existed in the 1806 Articles of War, which had previously prescribed the conduct of U.S. soldiers in wartime. Because the authors of that code had never imagined that the United States would fight a war in foreign territory, they failed to extend its jurisdiction beyond America's borders or to

28

make provisions for crimes against civilians. The shortcoming had, for all practical purposes, given American volunteers and civilians such as teamsters and camp followers immunity from punishment under the Articles. Under the 1806 Articles, they would be put on trial either in local Mexican civil courts or in civilian courts in the United States. Even the Regulars were exempt from the Articles while in foreign territory, although they were still held to the U.S. Army's own strict code of conduct.

In reality, Scott aimed General Order No. 20 at the volunteers. Alarmed, both Secretary of War Marcy and Attorney General Nathan Clifford argued against its harsh provisions, fearing that the volunteers and their families might be enraged and turn to Congress for relief. In the end, however, neither man forbade issuance of the proclamation.

As for the Regulars, both Scott and Taylor held them to strict standards throughout the war. Even petty theft was punishable by thirty lashes with rawhide. Indeed, many Regulars noted the injustice of volunteers literally getting away with murder while they faced extremely harsh punishments for comparatively minor crimes. This inequity contributed to some of the tension and animosity that existed between volunteer and Regular soldiers.

General Scott's policies underwent their first test immediately after the surrender of Veracruz on 27 March 1847. At that time, Scott reissued General Order 20, declared martial law, and arranged for the centralized distribution of food to the city's population, which had suffered serious privation during the siege. Another public proclamation stated that the U.S. Army was a friend to the Mexican people and that it would do away with the abuses that the Mexican government had inflicted on its people.

From this enlightened beginning, Scott's occupation campaign differed markedly from Taylor's. By insisting on strict discipline, Scott preempted many of Taylor's problems with volunteers. When a military commission found two soldiers guilty of stealing from a local store, for example, the Army imprisoned both in the town's dungeon. When another commission found Isaac Kirk, a "free man of color" working for the Army, guilty of rape and theft, the Army hanged him. Scott quickly issued a proclamation on 11 April 1847 declaring that the capital punishment proved the Army would protect the Mexican people. Those examples and others like them had their effect. Scott reported a few weeks later that after the imposition of these sentences, "... such offenses by American soldiers abated in central Mexico."

Scott also assured merchants that the Army would protect their goods. As a result, local markets reopened for business quickly. In

29

addition, the general saw to the organization of indigenous work crews to clear the streets of debris and accumulated garbage. The citizens not only aided in removing visible signs of the war left from the siege but also were paid a high salary, which was meant to improve the local economy by infusing it with money. The program garnered considerable popular support for the occupation.

Scott repeatedly made the case to civic leaders and to the general population that if the Mexican people cooperated with his forces, the war would end more quickly and with less devastation. Such policies convinced Veracruz's inhabitants to accept American occupation with little noticeable resistance. Life returned to normal in the town, and Scott wrote Secretary of War Marcy that the people "are beginning to be assured of protection, and to be cheerful."

Unlike the Polk administration, Scott understood and honored local mores. When Marcy suggested that he raze San Juan de Ulua, the culturally important castle in Veracruz, for example, Scott refused on grounds that the destruction of such an important site would only sow anger and resentment. Scott knew that successful guerrilla campaigns, like those in Spain against the French, required an environment hostile to the occupiers. He used discipline, good public relations, and an understanding of the local culture to keep that from happening.

To win the war in the shortest possible time, Scott planned to abandon many of his resources and to march boldly into Mexico's interior to seize the country's capital in a single daring stroke. He also understood that he could accomplish the task with fewer than 10,000 frontline troops only if the Mexicans who lived along the Veracruz-Mexico City corridor provided goods and food and declined to rise up en masse against his forces. Consequently, Scott insisted that his officers pay in full and at a premium price all provisions his army gathered from Mexicans. He also ordered, "The people, moreover, must be conciliated, soothed, or well treated by every officer and man of this army, and by all its followers." Public opinion had to be favorable, or at least neutral, toward the Americans. Thus, as in Veracruz, he maintained strict discipline throughout the ensuing campaign to Mexico City and insisted on severe punishments for transgressors. When a soldier in the 8th Infantry killed a Mexican woman at Jalapa, a military tribunal ordered him hanged. The military similarly executed two civilian teamsters in the town for murdering a local boy.

Because of his astute observations and careful planning, Scott faced a type of guerrilla different from the one that opposed Taylor. Rather than facing an angry population such as the one supporting various irregular forces in the north, U.S. forces in central Mexico were beset

30

by the Light Corps, highly trained and motivated volunteers fighting in formal partisan military units with the explicit consent of the Mexican government.

After their official creation on 27 April 1847, Light Corps units were operating in the Veracruz-Mexico City corridor by mid-May 1847. They soon became such a menace that Maj. Gen. John A. Quitman, a leading southern Democrat and a staunch supporter of President Polk, required 1,500 men to escort him from Veracruz to his new command with Scott's main force. Raising this force delayed Quitman's departure from the coast for several weeks.

The number of attacks on Americans climbed steadily during the summer and fall of 1847. The first actions focused on small groups of soldiers. In one instance on 2 May 1847, guerrillas rode down two soldiers, "lassoed" them "around their necks and dragged on the ground," and then speared their battered bodies. Scott responded with Capt. Samuel Walker's mounted Texas Rangers, ruthless fighters outfitted with Colt six-shot revolvers. Walker's men engaged the guerrillas outside of La Hoya and Las Vigas, two towns about seventy miles northwest of Veracruz, killing some fifty Mexican irregulars.

Travel on the National Highway, nevertheless, became increasingly dangerous. In June, Lt. Col. Ethan Allen Hitchcock, Winfield Scott's inspector general and later his chief of intelligence, began using Mexican criminals liberated from prisons as couriers to slip through the guerrilla- infested corridor to the coast. His first messenger, a convicted highway robber named Manuel Dominguez, assured him that other prisoners hostile to Santa Anna and the government would eagerly support such missions. Believing that such a group could provide valuable intelligence services, Hitchcock proposed recruiting a "Spy Company" made up entirely of Mexicans. Scott eagerly endorsed the plan, and Hitchcock raised a 100-man force under Dominguez's command that included many former prisoners.

The company gathered information, provided messengers, and acted as guides and translators. Some of its most valuable intelligence came from its members who infiltrated Mexico City as "market people from Chalco ... selling apples, onions, etc." From those missions, the spies gave Hitchcock detailed reports about the situation in the city and its defenses. Scott also instructed them to capture or kill guerrilla leaders whenever possible. As a result, the company captured Mexican Generals Antonio Gaona and Anastasio Torrejon during operations near Puebla. Overall, the Spy Company performed effectively, easily slipping undetected through Light Corps positions along the Veracruz-Mexico City road. Concerned, Santa Anna himself offered all of the spies a

31

Samuel Walker (Library of Congress)

"pardon for all past crimes" and "a reward adequate to any service they may render to the Republic."

Scott also had other sources of human intelligence. Records detail that his command spent some $26,622-or more than $520,000 in 2004 dollars-in payments for information-gathering efforts. Of that, Hitchcock paid $3,959 directly to the Spy Company as salaries. The rest

32

Ethan Allen Hitchcock (Library of Congress)

went to informants, deserters, Mexican officers, and even one of Santa Anna's servants.

As the Americans rushed to create an intelligence apparatus, the partisans made American supply trains a continual target. A convoy under the command of Lt. Col. James S. McIntosh, for example, left Veracruz on 4 June 1847 with nearly 700 infantrymen and approximately

33

128 wagons. During the next two weeks, the Light Corps attacked it on three separate occasions. The first came on 6 June, as it approached Cerro Gordo. McIntosh halted the convoy and called for reinforcements after losing twenty-five men who were wounded and killed along with twenty-four wagons that were destroyed. A relief column under Brig. Gen. George Cadwalader with 500 men reached the besieged unit on 11 June. Reinforced, the Americans started to move forward again only to find the Puente Nacional, or National Bridge, occupied by partisans. Located some thirty-five miles northwest of Veracruz, the bridge spanned a wide valley with imposing terrain on both its sides, creating a perfect bottleneck for the convoy. Only after McIntosh and Cadwaladar fought a series of fierce actions against Light Corps positions around the bridge, losing thirty-two dead and wounded, was the convoy able to continue. Pushing on, it next came under assault on 21 and 22 June when an estimated 700 men attacked it at La Hoya. Again, Cadwalader and McIntosh's troops eventually battled their way through. The Mexican Spy Company later located additional guerrillas preparing to ambush the column yet again, but Captain Walker's Rangers rushed out of their garrison at Perote, a nearby town, and managed to disperse the irregulars. The column reached Scott's main force a few days later.

After the heavy resistance faced by McIntosh, Scott decided to use larger and more heavily armed convoys. Brig. Gen. Franklin Pierce, a future president of the United States, departed Veracruz in early July 1847 with 2,500 troops, 100 wagons, and 700 mules. Some 1,400 Mexican irregulars met the supply train at the National Bridge, however, and forced Pierce to retreat to Veracruz after losing thirty men. Reinforced with artillery and additional forces, Pierce eventually reached Scott's force at Puebla without further incident.

Another column carrying much-needed supplies departed Veracruz on 6 August 1847, guarded by some 1,000 men under Maj. Folliott T. Lally. Again, the irregulars attacked, and Lally lost 105 men as he fought his way through the resistance. The commander at Veracruz sent three companies to assist, but enemy action forced even that relief column to return to Veracruz after it lost all but one supply wagon in yet another fight at the National Bridge. In the end, Lally managed to push through the enemy's positions and to reach Scott's army a few days later.

The next supply train set out from Veracruz in September 1847. Maj. William B. Taliaferro reported that his force faced daily attacks and lost several men in each one. Even at night, Light Corps partisans harassed the Americans with heavy fire, but, in the end, Taliaferro broke through and reached Scott.

34

Because the Light Corps specialized in killing stragglers and other men separated from their units and in assaulting small detachments on foraging or reconnaissance missions, American commanders increasingly sought to keep their forces concentrated. On 30 April 1847, warning that "stragglers, on marches, will certainly be murdered or captured," Scott's orders required officers of every company on the march to call roll at every halt and when in camp to take the roll at least three times a day. While his force rested at Puebla to await reinforcements, Scott also made it a punishable offense to enter the town alone. He instructed soldiers to travel in groups of six or more, to be armed at all times, and to leave camp only if accompanied by a noncommissioned officer.

Such orders reflected an additional threat. Men from the Light Corps continually worked their way into American garrisons at night, killing individual soldiers. In the seaport garrison at Villahermosa, Commodore Matthew C. Perry, U.S. Navy, explained that "Mexican troops infiltrated the town every night to pick off Americans; this was the kind of fighting they liked and they were good at it." Attempts to prevent the attacks proved unsuccessful because "dispersing Mexicans" seemed "no more effective than chasing hungry deer out of a vegetable garden. They always drifted back, to take pot shots at `gringos."' Col. Thomas Claiborne, commander of the garrison housed in the fortress Perote, reported that "the guerrillas were swarming everywhere under vigorous leaders, so that for safety the drawbridge was drawn up every night."

Scott's capture of Mexico City on 14 September 1847 did not end his woes. While the Mexican regulars fled, average citizens and criminals who had been released from prisons as the Americans entered the city began using stones, muskets, and whatever other weapons were available to oppose the U.S. Army's advance. The irregular urban combat quickly turned vicious. The U.S. Army responded with close- range artillery fire against any building that housed guerrillas. Although such tactics ended widespread resistance, the partisans instead focused their attacks on individual and small groups of soldiers.

Meanwhile, the Light Corps continued to restrict the flow of supplies, mail, money, and reinforcements to Scott. Shortly after pacifying Mexico City in mid-September, Scott turned his mind to the problem posed by the increasingly bold partisans. First, he enlarged the garrison at Puebla to some 2,200 men and constructed four new posts along his line of communications at Perote, Puente Nacional, Rio Frio, and San Juan. Completed by November, each post contained about 750 soldiers. Their commanders were required to send strong patrols into the countryside to find and engage irregular forces. Finally, Scott

35

Scott entering Mexico City (Library of Congress)

decided that all convoys would travel with at least 1,300-man escorts. Thus, by December, he had diverted more than 4,000 soldiers, or nearly 26 percent of the 24,500 American troops in central Mexico, to secure his supply lines.

Scott also created a special antiguerrilla brigade and placed it under the command of Brig. Gen. Joseph Lane, a veteran of the fighting at Buena Vista. Lane's combined-arms force of 1,800 men included Walker's Rangers, as well as additional mounted units and light artillery, stressing mobility to better locate and engage Mexican Light Corps units. The brigade patrolled the Mexican National Highway and attempted to gather intelligence from the local population, either through cooperation or intimidation. Although not numerous enough to secure the entire length of the Veracruz-Mexico City corridor, the brigade did succeed in carrying the war to the partisans and their supporters.

Lane's brigade was most successful in an engagement with a large Light Corps unit led by Gen. Joaquin Rea on the evening of 18 October 1847 outside the town of Atlixco. Lane posted his available artillery on a hill overlooking the town and initiated a 45-minute cannonade into the irregular positions. After the bombardment, he ordered his force into Atlixco. The operation destroyed a significant portion of the Light Corps force with Mexican casualties totaling 219 wounded and 319 killed.

36

Although Rea escaped with some of his men and several artillery pieces, his original unit was largely destroyed. Lane reported that he declared Atlixco a guerrilla base and that "so much terror has been impressed upon them, at thus having the war brought to their own homes, that I am inclined to believe they will give us no more trouble." In the fight, Lane used his mobility to find and engage the enemy and his combined-arms team to inflict maximum damage on the Light Corps unit.

Unfortunately, Lane's unit became most infamous for a brief engagement that followed an incident at Huamantla, a few miles from the town of Puebla, on 9 October 1847. When Captain Walker of the Texas Rangers fell mortally wounded in the skirmish, Lane ordered his men to "avenge the death of the gallant Walker." Lt. William D. Wilkins reported that, in response, the troops pillaged liquor stores and quickly became drunk. "Old women and young girls were stripped of their clothes and many others suffered still greater outrages." Lane's troops murdered dozens of Mexicans, raped scores of women, and burned many homes. For the only time, Scott's troops lost all control. Lane escaped punishment in part because news that Santa Anna had stepped down as commander of the Mexican Army after the engagement at Huamantla overshadowed the American rampage.

In Washington, however, many would have applauded such an incident. Angered by the Mexican partisans' successes, the Polk administration ordered Scott to destroy the Light Corps' "haunts and places of rendezvous," a directive that eventually led the U.S. forces into a scorched-earth policy. Although Scott had his doubts about such tactics, he realized the necessity of denying the guerrillas sanctuary and thus applied "the torch" as historian Justin Smith commented "with much liberality, on suspicion, and sometimes on general principles, to huts and villages; and in the end a black swath of destruction, leagues in width, marked the route" from Veracruz to Mexico City. When such extreme measures failed to stop the Light Corps' attacks, Scott issued a forceful proclamation on 12 December 1847, declaring that "No quarters will be given to known murderers or robbers whether called guerrillas or rancheros & whether serving under Mexican commission or not. They are equally pests to unguarded Mexicans, foreigners, and small parties of Americans, and ought to be exterminated."

Once again, such measures failed to diminish the Light Corps' effect on Scott's line of supply. On 4 January 1848, a force of some 400 irregulars attacked a supply convoy near Santa Fe, in the state of Veracruz, and carried away 250 pack mules and goods. On 5 January, the irregulars attacked another convoy at Paso de Ovejas. Col. Dixon Miles, the convoy commander, requested reinforcements of at least 400

37

infantrymen plus artillery. Eventually, his column ran the gauntlet and reached Mexico City.

Scott's efforts to secure his rear line of communication enjoyed mixed results. In general, his work to calm and pacify the general population generally succeeded. Millions of Mexican civilians living in the Veracruz-Mexico City corridor went ahead with their lives as usual, and there was little of the spontaneous resistance to the U.S. occupation that had characterized events in northern Mexico. Nevertheless, the successes of the mounted Light Corps partisans cannot be denied and had a deleterious effect on the U.S. Army's freedom of action.

Scott's Stabilization Campaign

Scott's success against the regular Mexican Army had unexpected consequences. Its demise eliminated one of the primary elements holding Mexican society together. Without fear of reprisal, peasants across the country rose up in revolt. Between 1846 and 1848, some thirty-five separate outbreaks occurred across Mexico. In each case, the rebels targeted wealthy, landed elites and symbols of the nation's federal authority. A large revolt on the Yucatan peninsula in early 1848 pitted some 30,000 Indians against wealthy white landowners and merchants living in the region. The governor of the state issued an urgent plea for help, saying that the peasants were waging a "war of extermination against the white race." Here and elsewhere, the unrest took a high toll in both human and economic terms.

The state of unrest caused the U.S. Army two problems. First, the revolts steadily grew in size, frequency, and violence, thereby threatening to engulf U.S. forces. If the peasant revolts that swept through Veracruz targeted Scott's army, as well as the upper-class Mexicans, all could be lost. Second, without a strong central government in place, no peace treaty with Mexico would be possible and thus no legal guarantee for the territorial acquisition that the United States desired. As President Polk explained about Mexico, "Both politically and commercially, we have the deepest interest in her [Mexico's] regeneration and prosperity. Indeed, it is impossible that, with any just regard to our own safety, we can ever become indifferent to her fate."

The Mexican elites recognized the necessity of reaching some sort of peace accord before they could rebuild their army, the prerequisite ensuring their hold on power. The central government, in exile since Scott occupied the capital, thus faced a conundrum. It confronted a two-front war, one with the United States and the other with the rebellion, the former gradually appearing as the lesser of two evils. The

38

northern aggressor desired territory, while the ruling elite feared that the Mexican people wanted nothing less than a race war that would lead to the destruction of the elite or elimination of its power and privilege. In the end, although the rebellion caused the Americans concern, it and some twenty-two months of warfare and occupation persuaded Mexico's political leaders to end their resistance and to pursue peace.

As a result, the two sides agreed to terms on 2 February 1848 in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Although it took several months for both governments to ratify, the accord met most American demands. Mexico recognized U.S. sovereignty in Texas, with its southern border resting on the Rio Grande, and agreed to cede Upper California and New Mexico, the region that eventually became the states of Arizona, California, Nevada, New Mexico, and Utah, as well as portions of Colorado, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and Wyoming. In return, the United States promised to pay Mexico $15 million in gold and to assume responsibility for all outstanding claims that American citizens had against Mexico. In short, the war with Mexico and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo largely defined the current western borders of the United States, making a country that stretched from coast to coast.

While the two nations carried out their respective ratification processes, they concluded a truce on 6 March 1848. This often-overlooked document not only confirmed that all hostilities had ceased but also included a stabilization plan to rebuild the Mexican government. One important part of the agreement read, "If any body of armed men be assembled in any part of the Mexican Republic with a view of committing hostilities not authorized by either government, it shall be the duty of either or both of the contracting parties to oppose and disperse such body; without considering those who compose it." In effect, the United States promised to support the existing Mexican government against any internal rebellions, while Mexico agreed to disband any guerrillas still operating against U.S. forces.

The measure benefited the American Army more than the Mexican government, as Light Corps units raised and directed by the federal government almost immediately ceased troubling Scott's forces. The agreement accomplished what the American military could not do by force of arms alone end guerrilla attacks in the Veracruz-Mexico City corridor. Elsewhere, Mexican rebels of all stripes simply avoided the U.S. military and concentrated their efforts in areas outside of U.S. control.

The stabilization plan also provided that the United States would supply modern weapons to the Mexican government to aid in the reconstitution of the federal army. In the first delivery alone, the Mexicans

39

received 5,125 muskets, 762,400 cartridges, 208 carbines, and 30,000 carbine cartridges from local American supply depots. The U.S. Army sold the munitions at a greatly reduced price, less than half of their market value. More important than the sheer numbers was the quality of the equipment. The American weapons were of the latest pattern and much more accurate than those that the Mexican Army had previously possessed. At the battle of Palo Alto, for example, a large number of the Mexican small arms had been outdated and unserviceable British Brown Bess muskets.

Finally, in an effort to stabilize the Mexican economy, the Americans allowed Mexican merchants to join their convoys between Veracruz and Mexico City and to sell their wares to the Army. That corridor had long served as a key commercial route, and thus the U.S. presence expanded trade and provided a great, albeit temporary, boost to the region's economy. The U.S. Army also escorted Mexican traders who carried precious metals from the mining regions in northern Mexico to the Rio Grande and eventually to the Gulf coast.

The U.S. Army and the Problems of Occupation

Although U.S. forces won every conventional battle, a multitude of issues arose to threaten the occupation once it began. Logistical difficulties in particular proved a major factor. The simple movement of the materiel deep into Mexico over rough roads took significant planning. Army Quartermasters partially alleviated their difficulties by creating a series of forward supply depots in the southern United States along the Gulf coast and up the Rio Grande. Those depots permitted the Quartermasters to pre-position equipment and supplies and to forward them far more quickly to critical points in the theater of operations. However, a general shortage of transport-whether steamships to move supplies up the Rio Grande, wagons to traverse level areas with established roads, or pack mules to caravan through mountainous regions-prevented many goods from reaching the troops in a timely manner. As a result, American forces had to acquire much of their supplies directly from local Mexican sources, often by purchasing them at premium prices.

As supply lines lengthened, the effort to guard those routes became difficult and required increased numbers of troops. Early in the conflict, Taylor had paid little attention to convoy security. Because of that, Mexican guerrillas scored several impressive victories against lightly armed supply trains and managed to carry away tons of supplies, money, and mail. In the end, both Taylor and Scott were forced to

40