The American Soldier, 1781

Sir Henry Clinton, the British commander in chief in North America had long planned to neutralize the state of Virginia by establishing a base in the Chesapeake Bay region, encouraging Tory action in support of the crown, and sending raiding forces up the various rivers. In January 1781 he initiated a devastating raid with sixteen hundred men up the James River under the traitorous Benedict Arnold. To counter or capture Arnold, Washington sent Lafayette to Virginia with twelve hundred Continentals to be augmented by Virginia militia. This effort was not successful. Indeed, after British reinforcements arrived from New York, the raids worsened and, following the late May arrival of General Cornwallis, British strength increased to about seven thousand men. Lafayette then became the pursued. But General Clinton in New York was not enthusiastic about Cornwallis' pursuit in the Virginia interior and ordered him to return to the coast, establish a base, and provide a contingent of troops to New York. Responding, Cornwallis returned to Yorktown by way of the York River. He was warily followed by Lafayette and General Wayne who had joined Lafayette with an additional eight hundred Continentals.

During this period, Washington was negotiating to obtain French cooperation for a combined sea-land attack on New York in the summer of 1781. He was subsequently informed in mid-August that the French West Indies fleet under Admiral de Grasse would not come to New York but would go to Chesapeake Bay and remain there until mid-October. Washington realized that if he could achieve superiority on land while de Grasse blockaded the bay, Cornwallis could be defeated before Clinton could relieve him. His immediate problem was to move as many American troops south as could be spared from the defense of West Point as well as Rochambeau's four thousand French who had joined him in April without raising Clinton's suspicions. It would also be necessary for the French squadron from Newport under Admiral Barras to bring ammunition and supplies to Chesapeake Bay. Finally, and of utmost importance, de Grasse's fleet with its ships and reinforcements had to arrive as planned. To deceive Clinton, Washington deliberately leaked information that ongoing movements of American and French troops were to concentrate for an attack on Staten Island from New Jersey. The ruse was successful. But when word reached Washington in Philadelphia on 1 September that the reinforced British fleet had sailed from New York, he could only conclude that the British fleet was out to intercept Barras or de Grasse.

The American-French force marched through Philadelphia during the next few days and past Chester to the Head of Elk from where they were to be transported by water to Yorktown or an alternate location close by. Washington followed on 5 September by road, while Rochambeau went to Chester by water. Still plagued by his worries regarding the French and British fleets, Washington rode steadfastly past Chester. Three miles to the south he was met by an exhausted express rider who reported that Admiral de Grasse with twenty-eight ships of the line and three thousand men was in Chesapeake Bay.

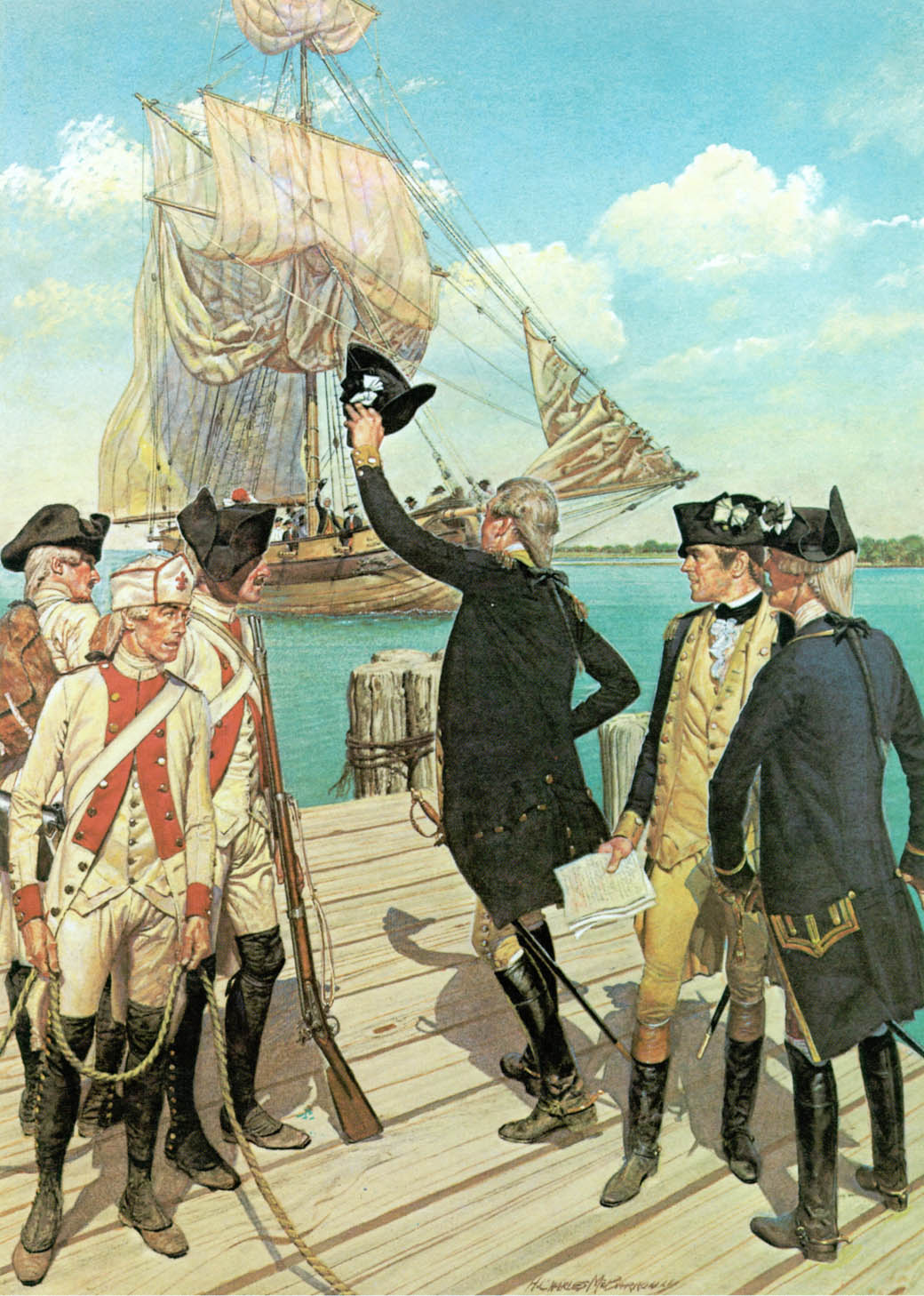

Washington turned back to Chester to give the exciting news to Rochambeau. When the Frenchman's ship came in sight, the usually dignified Washington took off his hat, waved it around, and laughed and shouted at the astonished French general, who soon joined in the rejoicing.

The painting depicts Washington waving to Rochambeau and shows a group of enlisted men from the French Soissonais Regiment, and an American and a French staff officer. General Washington and the American staff officer wear the black cockade with white center in honor of their French allies, and the French staff officer wears a white cockade with a black center in honor of the Americans.