Map No. 1

LAUNCHING THE INVASION

"I am ashore with Colonel Simmons and General Roosevelt, advancing steadily (0940). ... Everything is going OK (1025).... Defense is not stubborn (2400)." Thus did Col. James A. Van Fleet report the progress of his 8th Infantry to his commanding officer, Maj. Gen. Raymond O. Barton of the 4th Division, on D Day, 6 June 1944. These messages were confirmed by liaison officers returning to the headquarters ship, U.S.S. Bayfield, after trips to the beach: "Everything is moving along very nicely." To Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins, commanding the VII Corps, these reports were reassuring indications that at least a foothold had been secured on the Cotentin Peninsula and with less difficulty than had been feared (Map I). [1]

The comparative ease with which the 4th Division had come ashore on "Utah Beach" was, however, only a part of the story of the VII Corps assault. Hard fighting in the Cotentin Peninsula had preceded the seaborne landings, as two airborne divisions, the 82d and 101st, had been dropped into the beachhead area several miles inland beginning at about H minus 5 hours. Their mission was to seize crossings or destroy bridges over the Merderet and Douve Rivers and secure vital exits of causeways leading inland from the beach across inundated areas, and thus facilitate the expansion of the beachhead by the 4th Division. The mission of the airborne divisions was a key one, for the success of the Utah assault was largely dependent on the success of their operation.

The VII Corps assault on the east Cotentin constituted

the right flank of the larger Allied invasion

known as Operation NEPTUNE. The original plan

for the 1944 invasion of the Continent, known

as the OVERLORD Plan, did not include an assault

on the beaches of the east Cotentin, largely

because, when the plan was written in. the summer

of 1943, it was believed that with the resources

then allotted to the operation it would be sounder

to concentrate on the landings over the beaches

between Grandcamp and Caen. On the other hand

it was recognized that a landing on the Contentin

proper, on beaches northwest of the Carentan

estuary, would be highly desirable in order to

insure the early capture of the port of Cherbourg.

Tactical planning had been dominated from the

beginning by the need for adequate port capacity,

on which the later build-up of forces in the

lodgment area largely depended. When Gen. Dwight

D. Eisenhower

[1]

assumed supreme command for OVERLORD in January 19442 it seemed to him and his subordinate commanders that the Cotentin assault was not only desirable but essential for the success of the invasion. Additional resources were found and the original three-division assault was increased to five. The assault front was widened both eastward to include additional beaches in the British sector and westward to include the east Cotentin. Equally important, the provision of additional air transport made it possible to land two and two-thirds airborne divisions simultaneously. Two of these airborne divisions were to land in the American sector to reduce the admitted risks of the west flank assault, where troops for some time after landing would be separated

[2]

from the main body of Allied forces by the Carentan estuary and would attack in an area where the enemy had formidable defensive advantages.

One of the factors which had dominated the tactical planning for NEPTUNE was that the assault area itself did not include a port, which was so necessary for sustained operations. The first mission of the invasion force following the consolidation of a beachhead was therefore the capture of Cherbourg. This mission was assigned to VII Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins. The VII Corps, together with V Corps, which was to land at Omaha Beach, constituted the First U.S. Army under Lt. Gen. Omar N. Bradley. On General Bradley's left was the Second British Army, commanded by Lt. Gen. Miles C. Dempsey. The two armies together constituted 21 Army Group under Gen. Sir Bernard L. Montgomery, who, for the assault phase, was the over-all ground commander.

Tactical Aspects of the Terrain

The dominant terrain feature of the south Cotentin is the Douve River which, together with its principal tributary, the Merderet, drains the major portion of the peninsula, flows south and southeast, and then turns toward the sea (Map I). Neither river has high banks or is sufficiently wide to present insurmountable obstacles, but through much of their course these rivers flow through flat bottom lands and water meadows. A lock and dam at la Barquette, just north of Carentan, controls the drainage of most of these bottom lands. At high tide the low marshlands of the Douve and the Merderet are below sea level, and by opening the lock these lands can be converted into shallow lakes, which, supplemented by the water meadows and undrained swampland of the Prairies Marecageuses to the south, effectively isolate the Cotentin, restricting all land traffic to established routes through Carentan and Pont l'Abbe on the east and to a narrow strip of land between St. Lo- d'Ourville and St. Sauveur-de-Pierre-Pont on the west. The blocking of these routes and the seizure of the la Barquette locks intact would permit the establishment of an easily defended military line to the south, protecting the rear and the west flank of forces pushing northward against Cherbourg.

On the east coast of the Cotentin a belt of low-lying meadow land, from the mouth of the Douve to Quineville, had been subjected to shallow flooding. This area of inundation, running parallel to Utah Beach, had been created by the obstruction of several stream exits about fifty yards to the rear of the beach, resulting in the flooding or complete saturation of the soil for a width of one to two miles. Travel in this area was restricted to a few causeways which cleared the inundations by approximately one foot but could be easily obstructed by blocks or demolitions.

Critical areas of the Cotentin therefore were: (1) the Carentan-la Barquette area, with its control of the water level in the low marshlands along the Douve and Merderet, which was the key point in the east for passage into or out of the peninsula; (2) the dry ground between St. Lo-d'Ourville and St. Sauveur-de-Pierre-Pont, which controlled the western approaches to the peninsula; and () the inundated area between the mouth of the Douve and Quineville, which not only restricted the exploitation of an initial landing by canalizing any advance from the beachhead but also facilitated the enemy's defense of the area.

The VII Corps' original plan of attack was designed to gain immediate control of these critical areas. Briefly, it provided for an assault on Utah Beach by the 4th Division (with attached tanks and combat engineers) and two predawn airborne landings: one by the 101st Airborne Division southeast of Ste. Mere-Eglise, with the task of capturing the vital beach exits and blocking the eastern approaches

[3]

to the peninsula; and the other by the 82d Airborne Division west of St. Sauveur-le Vicomte, with the mission of sealing the western approaches to the peninsula.

Utah Beach, located directly east of Ste. Mere-Eglise, is a smooth beach with a shallow gradient and compact grey sand between high and low water marks. It differs from Omaha in that the terrain along the shore is not high; there is no dominating ground to assault and secure. Direct access to the beach is hindered only by the Iles St. Marcouf. The beach is backed for nearly 10,000 yards by a masonry sea wall, which is almost vertical and from 4 to 8 feet high at the proposed landing point. Sand is piled against the sea wall face in many places, forming a ramp to the top, which has a wire fence. Gaps in the wall mark the termini of roads leading to the beach, but these gaps were blocked. Behind the wall, sand dunes, from 10 to 20 feet high, extend inland from 150 to l,000 yards, and beyond them were the inundated areas whose western banks and exits might be easily defended by relatively small enemy forces.

Man-made defenses along the coast took various forms. Since the beginning of 1944 construction activity had increased markedly in the defensive belt. On the beach itself rows of obstacles had been emplaced at a distance of from 50 to 130 yards to seaward. These obstacles were in the form of stakes or piles slanted seaward, steel hedgehogs and tetrahedra, and Element "C" or "Belgian Gates," which were barricade- like gates constructed of steel angles and plates and mounted on small concrete rollers. The gates were used also to block roads or passages where a mobile obstacle was needed to make a defensive line continuous.

Defenses immediately behind the beach along the sea wall consisted of pillboxes, tank turrets mounted on concrete structures, "Tobruk Pits," firing trenches, and underground shelters. These were usually connected by a network of trenches and protected by wire, mines, and antitank ditches. Concrete infantry strong points provided interlocking fire, and were armed with both fixed and mobile light artillery pieces. The strong point at les Dunes de Varreville, directly opposite "Green Beach" and first objective of the 1st Battalion, 8th Infantry, combined most of

[4]

these features. Increased activity was evident in this area early in the year, possibly as a result of Field Marshal Erwin J. Rommel's inspection of the Atlantic Wall in December and January. Aerial reconnaissance revealed new casemated positions and showed that new open field battery emplacements were being prepared.

The fixed infantry defenses were more sparsely located in the Utah Beach area than at Omaha Beach (where V Corps landed), probably because the enemy relied on the natural obstacle provided by the innundated area directly behind the beach. At and near the roads leading to the beach the defense was a linear series of infantry strong points, armed chiefly with automatic weapons. About two miles inland on the coastal headlands behind Utah Beach were several coastal and field artillery batteries, the most formidable being

[5]

those at Crisbecq and St. Martin-de-Varreville. Here heavy- and medium- caliber guns housed in a series of concrete forts were sited to cover both the sea approaches and the beach areas.

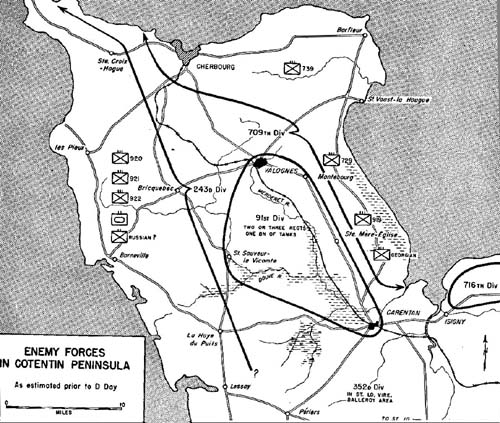

The Cotentin Peninsula lay within the defensive zone of the German Seventh Army, commanded by Col. Gen. Friedrich Dollmann. Allied intelligence estimates between March and early May of 1944 placed the enemy force occupying the Cotentin at two infantry divisions, the 709th and 243d. The 709th Division was known to have a large percentage of non-Germans, particularly Georgians, and was disposed generally along the east coast of the peninsula, with two of its regiments (729th and 919th) believed to be manning the beach defenses. The 243d Division was located generally to the rear of the 709th, with the mission of defending the western portion of the peninsula. The 716th and 352d Divisions, disposed east and south of the Cotentin, were not believed capable of affecting the VII Corps assault.

Intelligence reports early in May indicated that the enemy had been strengthening his coastal defense units to bring them up to the level of field divisions in strength and equipment. Formerly classified by Allied intelligence as "static," these divisions had been upgraded to "limited employment" or "low establishment." In addition to the organic field artillery of the infantry divisions, the enemy had various army and navy coast artillery and flak battalions, and the 709th Division was thought to have been strengthened by elements of the 17th Machine Gun Battalion at Carentan. It was not believed early in May that the enemy had panzer battalions or reserves of regimental strength in the Cotentin.

On the basis of these reports, the enemy was estimated to be capable of (1) rigid defense of the beaches, manning the crust of coastal fortifications and obstacles with the 709th Division and various artillery and flak units; (2) reinforcing the 709th Division in the assault area with elements of the 243d Division commencing at H Hour; (3) piecemeal counterattacks by a maximum of four battalions and a battalion combat team on D Day; and (4) a coordinated counterattack with motorized armored reinforcements from outside the peninsula at any time after D plus 2.

About ten days before D Day it was learned that enemy dispositions in the Cotentin had probably been altered as a result of the recent arrival of the 91st Division in the Carentan-St. Sauveur-le Vicomte-Valognes area. This division was estimated to consist of two or three regiments and one battalion of tanks. The 243d Division was believed to have moved farther west, while the 91st Division occupied positions to the rear of the 709th Division (Map No. 1). The mission of the 91st was

[6]

apparently to strengthen the defense of the eastern half of the peninsula from Carentan to Valognes. These three divisions were part of the LXXXIV Corps, which also controlled other divisions east of the Cotentin Peninsula.

The appearance of the 91st Division was a surprise. It upset the VII Corps original plan of deployment and forced a change in the initial mission of the 82d Airborne Division.

The VII Corps plan of operations was issued on 27 March 1944. One of its major objectives, derived from the tactical aspects of the Cotentin terrain, was the cutting of the entire peninsula at its base as a preliminary to the drive on Cherbourg. The original plan of deployment provided that the 101st Airborne Division would land southeast of Ste. Mere-Eglise, destroy the bridges in the vicinity of Carentan, and seize the crossings over the Douve at Pont l'Abbe and Beuzeville-la Bastille in order to protect the southern flank of the VII Corps

[7]

This plan of deployment had to be revised when it became known toward the end of May that the Germans had moved the 91st Division into the Cotentin. The additional strength which the enemy now possessed greatly increased his capabilities. Not only was he now able to meet the beach landings in greater strength, but his possession of additional troops at St. Sauveur-le Vicomte constituted a potentially serious threat to an airborne landing in this vicinity. It now became more important than ever for the seaborne elements to secure rapidly a beachhead sufficiently deep to hold against enemy counterattacks in force. Of equal importance was the need for a prompt drive to Carentan to forestall the destruction of the locks in this area, to seal off the enemy's eastern approach to the beachhead, and to keep the Germans from driving a wedge into the initial gap between VII and V Corps.

General Collins learned of the changed enemy situation in the Cotentin on 27 May, when he was called to General Bradley's headquarters in Bristol and was advised of the necessity of making some changes in the plans for the drop of the two airborne divisions.

[8]

It had been clearly understood that the 82d and 101st Airborne Divisions were to be under First Army control during the mounting of the operation and until they actually touched ground in Normandy. Maj. Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway and Maj. Gen. Maxwell D. Taylor, commanding generals of the 82d and 101st respectively, had, therefore, received their early instructions on the planning directly from the First Army staff. However, since both divisions were to pass to VII Corps control upon landing, General Bradley had agreed that General Collins' staff should collaborate closely in the detailed planning.

At the Bristol meeting of 27 May the First Army staff proposed that both the 82d and 101st Airborne Divisions be dropped east of the Merderet-the 101st south and east of Ste. Mere-Eglise, and the 82d in the immediate vicinity of that town. After some study, General Collins suggested a less radical change: that the 82d be dropped between the Merderet and the Douve, generally north of Pont l'Abbe, and that the 101st's plan remain unchanged. General Collins thought that the 82d would thus be in a better position to seize not only the crossings of the Merderet at la Fiere and Chef-du-Pont but also the crossings of the Douve farther west in the vicinity of St. Sauveur-le Vicomte and Ste. Colombe.

After additional study of the maps, however, it was concluded that because of the wooded and thickly hedged area between the Merderet and the Douve, and the paucity of clearings large enough to take gliders, it would not be possible to drop the entire 82d Division west of the Merderet. The final decision, therefore, provided for a divided drop astride the Merderet, with one parachute regiment dropping to the east and two parachute regiments to the west of the river (Map II).

When this change was made, troops of the infantry divisions were already moving into the marshaling areas preparatory to embark-

[9]

In the new plan it became the task of the 82d Airborne Division to secure the western edge of the bridgehead, particularly by capture of Ste. Mere-Eglise, a key communication center, and by establishing deep bridgeheads over the Merderet River, on the two main road westward from Ste. Mere-Eglise, for a drive toward St. Sauveur-le Vicomte. The 101st Airborne Division was to clear the way for the seaborne assault by seizing the western exits of four roads from the beach across the inundated area. At the same time it was to establish defensive arcs along the northern and southern edges of the invasion area and establish bridgeheads across the Douve at two points for later exploitation in a southward drive to Carentan to weld the VII and V Corps beachheads.

The missions of the 4th, 90th, and 9th Infantry Divisions remained unchanged. The 4th Division, principal seaborne unit in the assault on Utah Beach, was heavily weighted with attachments for its special mission, among them the 87th Chemical Mortar Battalion, the 1106th Engineer Combat Group, the 801st Tank Destroyer Battalion, and one battery of the 980th Field Artillery Battalion (155-mm.), plus antiaircraft artillery units and a detachment of the 13th Field Artillery Observation Battalion. The 4th Division was to assault Utah Beach at H Hour, establish a beachhead, and then drive on Cherbourg in conjunction with the 90th Division, which was to land on D plus 1 (Map IV). One of the 90th Division's Regimental Combat Teams (RCT), the 359th, landing on D Day, was to be attached to the 4th Division for operations on its northeast flank, reverting to the control of the 90th upon the latter's arrival on shore. The 9th Division was to begin landing on D plus 4 and assemble in Corps reserve in the area around Orglandes, prepared for operations to the northwest.

In addition to these units the revised field order of 28 May provided for the temporary attachment to the VII Corps of another division, the 79th, to begin landing on D plus 8. And, as an added precaution, the support of Corps artillery was to be hastened by phasing ahead by three days the entry of two 155-mm. howitzer battalions (the 188th and 951st). To insure expeditious movement of men and supplies across the beaches the 1st Engineer Special Brigade was charged with organizing and operating all shore installations necessary for debarkation, supply, evacuation, and local security.

At H minus 2 hours a detachment of the 4th Cavalry Group was to land on the Iles St. Marcouf to capture and destroy any installations there capable of hindering the landing operations.

[10]

(Photos)

[11]

The VII Corps attack was to be preceded by intensive air and naval bombardment of enemy defenses in the landing zones of the amphibious forces. The Allied air forces had been carrying out an intensive strategic bombing of railroads and German Air Force bases. In order to deceive the enemy concerning the area to be invaded, concentrated bombing of coastal defenses was delayed until D minus 4, and even then was deliberately scattered, with more attacks delivered in the Pas de Calais area than in the area selected for invasion. Not until D Day itself were the Allies finally to show their hand by a concentrated bombardment of the coastal defenses at the points where landings were planned. The objective was neutralization of the fortifications, demoralization of the troops manning them, and disruption of transport and signal communications.

About midnight, on s June, bombers of the RAF were scheduled to range up the entire invasion coast, centering their attention on known enemy coastal batteries, especially on the two big coastal batteries at Crisbecq and St. Martin-de-Varreville. Shortly before H Hour, medium bombers of the Ninth Air Force were to attack batteries at Utah Beach and to the east. The Ninth Air Force was also to provide protection for the cross-Channel movement, and one squadron of fighter-bombers was to be on air alert over Utah Beach during the assault. After H Hour the Tactical Air Forces were to be on call to support the ground troops in their advance inland.

Naval fire support was to be given by Task Force 125, organized into a bombardment and a support craft group. The bombardment group, consisting of 1 battleship, 5 cruisers, 8 destroyers, and 3 subchasers, was organized into 5 fire support units. At H minus 40 minutes these warships were to begin the bombardment of enemy shore batteries and defenses which threatened the ships and craft in the Utah Beach assault. The support craft group, comprising 33 craft variously equipped with rocket launchers and artillery, was to deliver close-in supporting fires from positions nearer the beach. Rockets were to be discharged when the first waves of assault craft were still 600 to 700 yards from the shore. Beginning at H Hour naval fires were to be lifted to inland targets on call from naval shore fire control parties.

In magnitude the amphibious assault on the Atlantic Wall had never before been equaled. Months of special training preceded the actual landing. At the Assault Training Center at Wollacombe, England, infantry units practiced the assault of various types of strong points, and combat engineers received special training in the use of demolitions to clear beaches of obstacles. Together with airborne and other units they tested these techniques on Slapton Sands in full-scale dry run exercises such as DUCK and FOX, in which all phases of marshalling, embarking, and assaulting were practiced. The TIGER (27-28 April 1944) and FABIUS (4 May 1944 ) series of exercises were the last, and were the dress rehearsals for invasion. As a result, when paratroops and gliderborne units descended upon the Cotentin, followed by 30-man assault teams (each comprising an LCVP load ), beach-clearing demolition teams, and amphibious tanks, it was an assault by specialists.

The mounting of the invasion began in the second week of May. During that week assault troops entered the sausage-shaped marshalling areas along the roads of southern England, where a security seal was imposed and here the men remained until they departed for the embarkation points. While in the marshalling areas they were briefed on the coming operation, received final issues of supplies and equipment, and waterproofed their vehicles. Troops had concentrated by boat serials, so that when they finally left on 1 and 2 June

[12]

Provision of the lift, protection at sea, fire support, and the breaching of underwater obstacles were the responsibility of Task Force U, commanded by Rear Admiral Don P. Moon, USN. Task Force U was part of the Western Naval Task Force under the command of Rear Admiral Alan G. Kirk, who himself was responsible to Admiral Sir Bertram H. Ramsay, commander of the Allied Naval Expeditionary Force. An important factor in the success of Task Force U was the high degree of cooperation between General Collins and Admiral Moon and their staffs. Jointly they worked out the details of the operation in their fenced-in Quonset hut camp on Fore Street, Plymouth.

Task Force U comprised approximately 865 vessels and craft in 12 separate convoys. The lack of a large port necessitated the use of nine different loading and sortie points, all taxed to capacity. Most of the convoys contained three or four sections, which sailed from different ports and had to make precise rendezvous.

The difficulty of coordination was further complicated by a last-minute postponement of D Day. The date provisionally set a month earlier had been 5 June. On this and the two following days early morning light and tidal conditions fitted most closely the requirements of H Hour. It had been decided that the landings must be made near low tide, when most of the beach obstacles were exposed, and that the approach should be covered by darkness, but that the landings were to be made in daylight to give the assault troops visual bombing and observed naval fire support. Weather, however, interfered with the original plan. Predictions of strong winds and heavy seas for 5 June made General Eisenhower early on 4 June postpone D Day for twenty-four hours.

Task Force U convoys, having farther to sail than the other assault forces, had assembled on 3 June. The postponement of D Day found some of them already at sea. They back-tracked to use up the extra day, and some 250 gunfire support and landing craft sought temporary shelter in Weymouth Bay and Portland Harbor.

The regrouping of convoys began again early on the morning of June. Despite the turning back and the obvious difficulty of reorganizing so scattered a fleet, the second start was accomplished with a minimum of confusion and Task Force U sailed again for the Transport Area, 22,500 yards off Utah Beach (Map No. 2). Sweepers of the 14th and 16th Minesweeper Flotillas had cleared a boat lane across the mine fields on Cardonnet Bank and had marked the Channel well with red and green lighted dan buoys.

At 0200 the marker vessel was passed at the entrance to the Transport Area, and at 0229 the Bayfield, headquarters ship for Task Force U, anchored in its assigned berth. Primary and secondary control vessels took their stations nearer the shore. LCT's and fire LST's with Rhino ferries were anchored a little farther out. The Barnet and Bayfield held troops for Uncle Red Beach; the Dickman and Empire Gauntlet held troops for Tare Green. H Hour was 0630.

[13]

Return

to Table of Contents

Next Chapter