The U.S. Army and the Lewis & Clark

Expedition

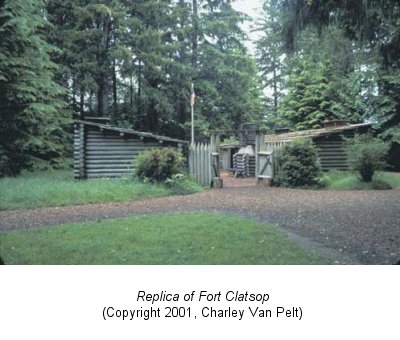

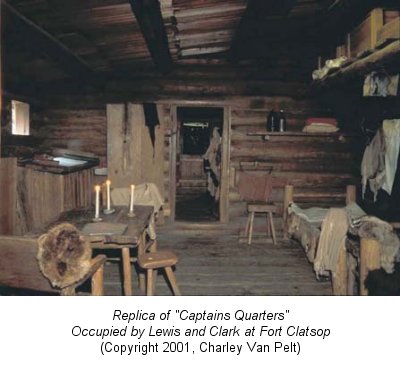

Part 7: Fort Clatsop and the Return Trek

Life at Fort Clatsop was depressing. Of the 112 (some say 102) days

the expedition was there, it rained every day except twelve, and only

half of those were clear days. Most of the men suffered from being constantly

wet and cold, and their clothing was rotting off their backs. Making

salt was a vital diversion, but boiling ocean water was a slow and tedious

process. After two months the operation

produced only one bushel of salt. Without salt, preserving food in

the wet and humid weather was a serious problem. To make matters worse,

hunting parties had a difficult time finding enough palatable food for

the expedition. Despite these challenges, Lewis and Clark kept everyone

busy, including themselves. Lewis spent much of his time writing in

his journal on botanical, ethnological, meteorological, and zoological

topics, while Clark completed the first map ever made of the land between

North Dakota and the Pacific coast. Together they discussed what they

had seen and learned from the Indians.

After three months of constant rain, dietary problems, fleas, and boredom,

the Corps of Discovery left Fort Clatsop on 23 March 23. Concerned with

the security of the Expedition, the two captains wanted “to lose

as little time as possible” getting to the Nez Perce. They decided

to return along the same path they had come, satisfied that it was the

best possible route. Even though security was rigid, at various points

on the way up the Columbia, Lewis and Clark had to use the threat of

violence to preclude trouble with the Indians. In early May they finally

reached their old friends, the Nez Perce. Once again, the Nez Perce

demonstrated their hospitality by feeding and taking care of the Corps

of Discovery. During a two-month stay with the Nez

Perce, Lewis and Clark held councils with the tribal elders, while

their men participated in horse races and other games with young Indian

warriors. Clark also used his limited medical skills to created more

goodwill. These activities built great relations with the Indians. Indeed,

Lewis wrote the Nez Perce considered Clark their “favorite physician.”

On 10 June, the Corps of Discovery set out toward the Lolo Trail, over

the objections of the Nez Perce. The Indians had warned Lewis and Clark

that the snow was still too deep to attempt a recrossing of the Rockies.

Eager to get home, the captains ignored this sound advice and proceeded

on without Indian guides. In a week the expedition found itself enveloped

in snow twelve to fifteen feet deep. Admitting that the going was “difficult

and dangerous,” Lewis and Clark decided to turn back. “This

was the first time since we have been on this long tour,” Lewis

wrote, “that we have ever been compelled to retreat or make a retrograde

march.” Sergeant Gass agreed, and noted that most of the men were

“melancholy and disappointed.” Two weeks later, the Corps

of Discovery set out once again, this time with Indian guides. Averaging

nearly twenty-six miles a day, the expedition took just six days to

reach the eastern side of the Rockies. On 30 June, Lewis and Clark set

up camp at Travelers Rest. There, the Corps of Discovery rested for

three days before implementing the final portion of its exploration.

According to the plan Lewis and Clark had formulated at Fort Clatsop,

they split their command into four groups. Captain Lewis, Sergeant Gass,

Drouillard, and seven privates would head northeast to explore the Marias

River and hopefully meet with the Blackfeet to establish good relations

with them. At the portage camp near the Great Falls, Lewis would leave

Gass and three men to recover the cache left there. Captain Clark would

take the remainder of the expedition southeast across the Continental

Divide to the Three Forks of the Missouri. There, he would send Sergeant

Ordway, nine privates, and the cache recovered from Camp Fortunate down

the Missouri to link up with Lewis and Gass at the mouth of the Marias

River. Clark, four privates, the Charbonneau family, and York would

then descend the Yellowstone River to its juncture with the Missouri

River. Meanwhile, Sergeant Pryor and three privates would take the horses

overland to the Mandan villages and deliver a letter to the British

North West Company, seeking to bring it into an American trading system

Lewis sought to establish. Lewis and Clark would unite at the juncture

of the Missouri and Yellowstone Rivers in August.

The willingness of Lewis and Clark to divide their command in such

rugged, uncertain, and potentially dangerous country shows the high

degree of confidence they had in themselves, their noncommissioned officers,

and their troops. In addition to the physical challenges the expedition

would certainly meet, war parties of Crow, Blackfeet, Hidatsa, and other

tribes regularly roamed the countryside and threatened to destroy the

expedition piecemeal. By dividing their command in the face of uncertainty,

Lewis and Clark took a bold but acceptable risk to accomplish their

mission.

Separated for forty days, the Corps of Discovery proceeded to accomplish

nearly all its objectives. Lewis and his team successfully explored

the Marias but narrowly escaped a deadly confrontation with the Blackfeet

in which two Indians died. What had begun as a friendly meeting turned

into a tragedy. On the afternoon of 26 July, Lewis came upon several

Blackfeet, greeted them, handed out a medal, a flag, and a handkerchief,

and invited them to camp with his party. They agreed. Lewis was thrilled,

but at the same time somewhat apprehensive: the Nez Perce, the Shoshoni,

and other plains tribes had warned Lewis to avoid their traditional

enemy. At council that evening, Lewis discussed the purpose of his mission,

asked the Blackfeet about their tribe and its trading habits, and urged

them to join an American-led trade alliance. During the discussion,

Lewis noticed that the Indians possessed only two guns; the rest were

armed with bows, arrows, and tomahawks. The meeting concluded with smoking

the pipe. Nevertheless, after standing first watch, Lewis woke Reubin

Field and ordered him to observe the movements of the Blackfeet and

awaken him and the others if any Indian left the camp.

At daybreak Joseph Field was standing watch without his rifle. As the

Blackfeet crowded around the fire to warm themselves, Field realized

he had carelessly left his rifle unattended beside his sleeping brother

Reubin. Suddenly, Drouillard’s shouts awakened Lewis, who noticed

Drouillard scuffling with an Indian over a rifle. Lewis reached for

his rifle, but it was gone. He drew his pistol, looked up, and saw an

Indian running away with his rifle. At the same time, another Indian

had stealthily slipped behind Joseph Field and grabbed both his and

Reubin’s rifles. The men chased the Indians, and Lewis and Drouillard

managed to recover their rifles without incident. But when the Field

brothers caught the Indian with their rifles, a fight ensued and the

Blackfoot died of a knife wound to his heart. After recovering the weapons,

the soldiers saw the Blackfeet attempting to take their horses. Lewis

ordered the men to shoot if necessary. Running after two Blackfeet,

Lewis warned them to release the horses or he would fire. One jumped

behind a rock while the other raised his British musket toward Lewis.

Instinctively, Lewis fired, hitting the Indian in the abdomen. The Blackfoot

fell to his knees but returned fire. “Being bearheaded [sic],”

Lewis wrote, “I felt the wind of his bullet very distinctly.”

Fearing for their lives, Lewis, Drouillard, and the Field brothers began

a frantic ride southeastward to reunite with Sergeants Gass and Ordway

at the mouth of the Marias. This they accomplished on 28 July, after

riding nearly 120 miles in slightly more than twenty-four hours.

As Lewis and his party made their way from the site where they had

encountered the Blackfeet, Sergeant Ordway’s group had recovered

the cache at Camp Fortunate, proceeded down the Missouri River, and

linked up with Sergeant Gass without incident. Gass’ team had already

recovered the cache at the portage camp at the Great Falls and was awaiting

Lewis and Ordway. Meanwhile,

while Clark and his party were exploring the Yellowstone River, Pryor

could not complete his mission. On the second night out, a Crow raiding

party stole all the soldiers’ horses. Demonstrating their ingenuity,

Pryor and his men kept their cool, walked to Pompey’s Pillar (named

in honor of Sacagawea’s infant son, whom Clark nicknamed “Pomp”),

killed a buffalo for food and its hide, made two circular Mandan-type

bullboats, and floated downriver to link up with Clark on the morning

of 8 August. Four days later, Lewis and his group found Clark along

the banks of the Missouri River.

Clark was astonished to see Lewis lying in the white pirogue recovering

from a gunshot wound in the posterior, but he was relieved to learn

it was not serious. While hunting on 11 August, Private Cruzatte apparently

had mistaken Lewis for an elk. On 14 August, the Expedition reached

the Mandan villages. After a three-day visit with the Mandans, the Corps

of Discovery bit farewell to the Charbonneau family and Private Colter

(who had requested an early release so he could accompany two trappers

up the Yellowstone River) and proceeded down the Missouri River. On

1 September, Lewis and Clark held a council with some friendly Yankton

Sioux. Three days later the Corps of Discovery stopped to visit the

grave of Sergeant Floyd