|

CHAPTER II Weathering the Postwar Years With the agony of the Civil War over at last, the nation began to rebuild. The demands made upon the Army by Reconstruction duty, Indian uprisings in the West, and French machinations in Mexico caused demobilization to proceed gradually. For the Signal Corps, peacetime meant a return to virtual nonexistence because the legislation creating the Corps in 1863 provided for its organization only "during the present rebellion." From a strength in November 1864 of over 1,500 officers and men, the branch had been reduced by October 1865 to just 160 officers and men.1 In the absence of definitive congressional authority, its postwar status remained uncertain. Chief Signal Officer Benjamin F. Fisher addressed the issue of organizing the peacetime Signal Corps in his 1865 annual report. In reviewing the last year of the war, he lamented the lack of defined duties which had often "crippled the usefulness of the corps by its not being properly understood what it could do or was expected to do." Each departmental commander had used his signal officers in a different way. Ideally, in Fisher's view, the Signal Corps in wartime should not only provide communications but also serve as the military intelligence bureau. Signal officers would collect information from all sources, analyze it, and present it "reduced to logical form' 'to the commanding general. Only in the Department of the Gulf, Fisher reported, had signal operations been conducted in this manner. During peacetime, however, the chief signal officer envisioned a much more limited role for the Corps. In general he recommended that signal officers be attached to garrisons and posts "liable to be besieged" in order to communicate over the heads of the enemy. These men would also constitute a nucleus of trained officers who could serve in the event of war. Congress could provide this nucleus either by "continuing a small permanent organization with specifically defined duties" or through a detail system. Fisher favored the adoption of the former course and recommended the appointment of a board of officers to define the mission and develop the organization of the Signal Corps.2 Congress failed to act on Fisher's recommendation. Instead, when it passed legislation in July 1866 authorizing personnel for the peacetime Signal Corps, it left the branch's duties undefined and also reverted to the objectionable detail system to obtain personnel. Under the provisions of this act the Signal Corps [41] was to consist of one chief signal officer with the rank of colonel. In addition, the secretary of war could detail six officers and up to one hundred noncommissioned officers and privates from the Battalion of Engineers. Before being detailed to signal duty, both officers and enlisted men had to be examined and approved by a military board convened by the secretary of war.3 By choosing to use engineers as signal soldiers, Congress conformed to the practice of several foreign armies. The British Army, for instance, detailed its military telegraphers from the Royal Engineers and, in fact, did not establish a separate signal corps until after World War I. At the same time, Fisher had another serious matter on his mind-keeping his job. His appointment as chief signal officer would expire on 28 July 1866 without guarantee of renewal. Meanwhile Myer, who left active duty in the summer of 1864, had been devoting considerable effort to preparing his case for restoration as the Signal Corps' chief. Soon after his relief in November 1863, Myer had requested signal officers in the field to secure testimonials in his behalf and have their subordinate officers sign petitions to be sent to Washington. This tactic prompted Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan to call Myer an "old wire puller," but Sheridan nonetheless prepared a statement.4 After completing the signal manual in 1864, Myer had become signal officer of the Military Department of the West Mississippi under Maj. Gen. Edward R. S. Canby, his old commander in New Mexico before the war. Under Canby, Myer had issued a "General Service Code" to be used for communication between land and sea forces and had participated in combat operations around Mobile, Alabama. Later, Canby served in the War Department as an assistant adjutant general with responsibility for oversight of the Signal Corps.5 In January 1865 Myer presented his case to the Senate in the form of a printed memorial consisting of a summary of his involvement with signals and signaling and the reasons why he should be reinstated. He later supplemented it with copies of various pertinent documents. Myer requested that the Senate delay the confirmation of any nomination for chief signal officer until it had examined his claim. Myer also met with President Lincoln, who promised not to appoint someone else as chief signal officer without studying the merits of the case. Myer followed up the meeting with a letter written the day before the president's assassination in April 1865. He also wrote to Secretary of War Stanton but received no reply.6 Despite these apparent setbacks, Myer did not abandon his efforts. Fisher, for his part, wished to retain the position in which he had served for over a year. Holding that Myer had waited too long after his dismissal to argue his case, he believed that the former chief "ought not be permitted to come for ward now and work injury to an innocent party."7 Although Fisher had performed adequately, Myer, as the Signal Corps' founder, had a strong claim to the job. General Ulysses S. Grant, now the commanding general of the Army, championed Myer's cause and urged Stanton to reappoint him.8 Stanton, however, neglected to act upon the recommendation, presumably because of the wartime friction between himself and Myer. Finally, on 25 October 1866, President [42] GENERAL MYER Andrew Johnson ordered Stanton to make the appointment, and he did so five days later. Although Myer accepted the appointment on 3 November and the Senate confirmed it the following February, he did not immediately resume his former duties. Fisher remained chief signal officer until 15 November 1866, despite the expiration of his appointment. After that date Bvt. Capt. Lemuel B. Norton ran the office. He was the only wartime signal officer to serve continuously in the Signal Corps into the postwar period.9 Most likely Myer hoped that Stanton, at odds with the president over Reconstruction policy and in declining health, would soon resign. As it happened, the tenacious secretary held on to his post until suspended by the president on 12 August 1867, an act that resulted in Johnson's impeachment. When Grant stepped in as acting secretary of war, Myer resumed his duties on 21 August 1867. Myer, vindicated at last, found himself once again at the head of the organization he had created. Not one to waste time, he soon submitted a proposal to Grant to reinstate the course in signaling and telegraphy at West Point. With Grant's approval, instruction began on 1 October 1867.10 Meanwhile, the Naval Academy continued to teach signaling, and the academy's superintendent, Vice Adm. David D. Porter, enthusiastically supported Myer's signal system. In 1869 the Navy established its own signal office based on the Army's model, but it never organized a distinct naval signal corps.11 Late in October 1867 the War Department issued orders authorizing the chief signal officer to furnish two sets of signal equipment and two copies of the signal manual to each company and post. Significantly, these orders allowed the chief signal officer to provide for the equipment and management of field electric telegraphs for active forces in the field. Thus in four years events had come full circle for Myer. By sheer tenacity he had won the Signal Corps' struggle for control of the kind of communications that would dominate the future.12 Further advances in signal training came in July 1868 when Secretary of War John M. Schofield directed that one officer from each geographical department be selected to receive signal instruction in Washington. Formal classes began in August at the Signal Office under the supervision of Capt. Henry W Howgate. A signal school for enlisted men opened in September 1868 at Fort Greble, one of [43] the forts built to protect Washington during the Civil War. The officers and men were detailed under the authority of the act of July 1866, but the War Department never invoked the provision to take them from the engineers. Myer believed that Congress had not intended to limit the details to the engineers alone, and that to do so would "be injurious both to the corps of engineers, by depriving it of officers whose services might be otherwise needed, and to the signal service, by the complications constantly to arise." Secretary of War Schofield accepted his argument and permitted the detail of up to fifty men from the general service for signal instruction at Fort Greble.13 Several naval officers also attended the school. Among the Army officers reporting for instruction in October 1868 was 2d Lt. Adolphus W. Greely of the 36th Infantry, a man whose subsequent career became inextricably linked with the Signal Corps. Both officers and men received similar instruction based on Myer's manual in the use of the various types of signal equipment. Officers additionally learned the cipher codes. Field practice comprised an important component of the training; an officer was not considered "well practiced" until he could send and receive visual messages readily, day or night, at a distance of fifteen miles. John C. Van Duzer, formerly of the Military Telegraph, taught electric telegraphy. In the new field trains, machines using batteries and sounders replaced the Beardslee instruments. A properly qualified officer could send and receive ten words per minute, and his men were expected to erect field lines at a rate of three miles per hour. Upon completion of their training, the secretary of war directed that one officer and two men be sent to each department to conduct signal training at the various posts.14 Because the United States Army's Signal Corps was the first organization of its kind, it drew the attention of other nations, and Myer received requests for information about signaling from several foreign governments. In February and March 1868, before the official opening of the Signal School, a Danish officer received instruction in the signal office in Washington. After the opening of the school, two Swedish Army officers were among the first students.15 Early in 1869 the School moved across the Potomac River to Fort Whipple, Virginia. Of the new location Myer wrote:

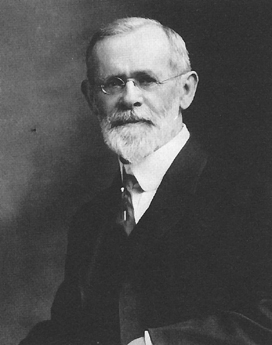

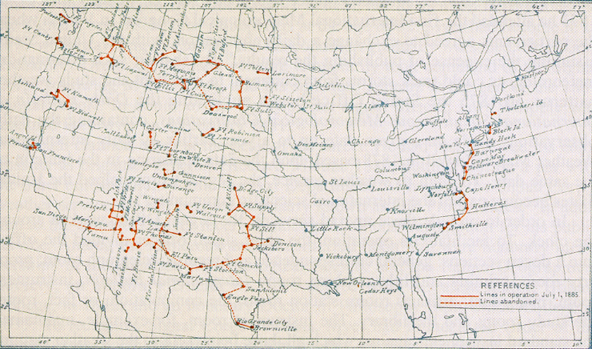

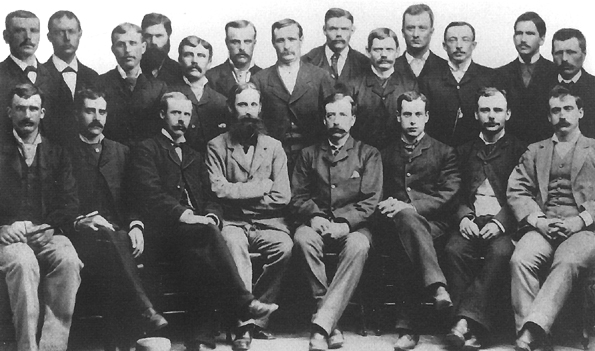

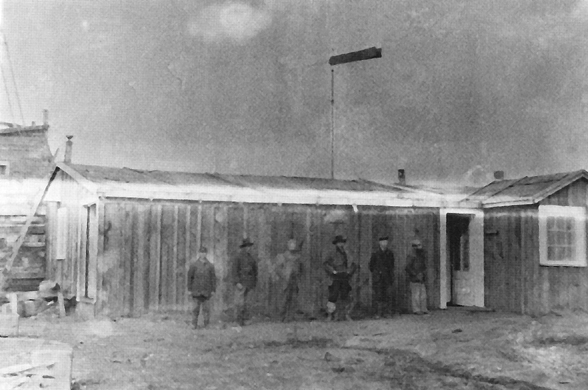

In his annual report for 1869 Myer expressed pride in the Signal Corps' recent accomplishments, but he could not forecast the changes the branch would soon undergo as the result of congressional hearings then underway regarding Army organization. The Signal Corps Becomes the Weather Service Despite the successful establishment of the Signal School, the Signal Corps still lacked a clear-cut mission. During hearings before the House Committee on [44] Military Affairs in 1869, Secretary of War Schofield testified that he felt the Army did not need a separate Signal Corps. The committee shared his view that the signal function could be performed by the engineers, but Congress did not act on this proposal.17 Nevertheless, when Congress reduced the size of the Army to save money, Myer knew that the Signal Corps needed a stronger footing in order to survive further scrutiny. One solution appeared to lie in weather observation and reporting, a field in which he had some experience from his days as an Army doctor. Weather has always regulated daily activities, especially for those whose livelihood is intimately tied to the land. Its study in the United States antedated the founding of the republic. Benjamin Franklin, who was not only a political leader but also a noted scientist in colonial America, had theorized about the origin and movement of storms. Another founding father, Thomas Jefferson, kept a daily journal of weather observations and corresponded widely with others of similar interest. Jefferson envisioned a national meteorological system, but until some means of rapidly reporting the weather was invented, a nationwide forecasting service was impossible.18 The Army's formal involvement in meteorology had begun in April 1814 when Dr. James Tilton, physician and surgeon general of the Army, directed military surgeons to record weather data. Regulations published for the Medical Department in December of that year required senior hospital surgeons to keep weather diaries. The collection of such information was believed to be important because weather was thought to influence disease.19 In addition to the Army, the Smithsonian Institution, founded in 1846, played an important role in the advancement of meteorology within the United States. Under the auspices of its first secretary, Joseph Henry, it organized the nation's first telegraphic system of weather reporting in 1849. Henry was a pioneer in the development of the electric telegraph, the instrument that made widespread, simultaneous weather observation and reporting feasible. The Smithsonian made arrangements with commercial telegraph companies to carry the reports of its voluntary observers, from which the first current weather maps were compiled. By 1860 five hundred stations reported to the Smithsonian, but the onset of the Civil War caused the network to decline and its importance to diminish. A fire at the institution in 1865 also inflicted considerable damage to meteorological instruments and records.20 After the war, as the nation's commercial and agricultural enterprises expanded, the need for a national weather service became apparent. Because the Smithsonian lacked the funds to operate such a system, Joseph Henry urged Congress to create one.21 A petition submitted in December 1869 to Congressman Halbert E. Paine by Increase A. Lapham, a Wisconsin meteorologist, provided further impetus for national legislation. Lapham advocated a warning service on the Great Lakes to reduce the tremendous losses in lives and property caused by storms each year. Paine supported this proposition and soon introduced legislation authorizing the secretary of war "to provide for taking meteorological obser- [45] vations at the military stations in the interior of the continent, and at other points in the States and Territories of the United States, and for giving notice on the northern lakes and on the seacoast, by magnetic telegraph and marine signals, of the approach and force of storms."22 Paine chose to assign these duties to the War Department because "military discipline would probably secure the greatest promptness, regularity, and accuracy in the required observations."23 Congress approved Paine's proposal as a joint resolution, and President Ulysses S. Grant signed it into law on 9 February 1870. Myer recognized that Paine's bill provided the mission the Signal Corps needed. As Paine later recalled: "Immediately after the introduction of the measure, a gentleman called on me and introduced himself as Col. Albert Myer, Chief Signal Officer. He was greatly excited and expressed a most intense desire that the execution of the law might be entrusted to him."24 Myer's efforts were rewarded when Secretary of War William W Belknap assigned the weather duties to the chief signal officer on 15 March 1870.25 Now the Signal Corps embarked upon a new field of endeavor, one that soon overshadowed its responsibility for military communications. At this time, before the advent of such weapons as long-range artillery and the airplane, weather forecasting had little relevance for Army operational planning. But the Army had long been performing duties not directly related to its military mission. Throughout the nineteenth century the Corps of Engineers, for example, had been carrying out projects such as river and harbor improvements that were not military in the strictest sense. Moreover, Congress had created the Corps of Topographical Engineers in 1838 specifically to conduct surveys and to build roads and canals that promoted national expansion. Thus, the assignment of weather duties to the Signal Corps was only another example of the Army's performance of essentially civil functions for the welfare of the nation.26 Having acquired the weather duties, Myer set about establishing a national reporting system. From the outset the Signal Corps directed its services chiefly toward the civilian community, as reflected in the title of the new "Division of Telegrams and Reports for the Benefit of Commerce" within the Office of the Chief Signal Officer. Myer subsequently added the words "and Agriculture" to reflect the additional services authorized by Congress in 1872.27 To provide weather information to the nation's farmers, the Signal Office published a Farmers' Bulletin that included daily weather summaries and predictions. It was telegraphed daily to and distributed from centers in the middle of agricultural areas. The Corps later added such services as frost warnings for tobacco, sugar, and fruit growers and special reports for cotton planters. During the 1870s American scientific education was in its formative stages. The rudiments of meteorology could be learned at such schools as Harvard and Yale, but no formal training for meteorologists existed. Therefore, the Signal Corps carried out its own program. The Corps conducted meteorological training at Fort Whipple in addition to regular military drills and signal instruction. "Full" training prepared a soldier to perform both field signal duties and those of the [46] weather service, while "field" training excluded weather duties. The Signal Corps selectively recruited personnel for the weather service-only unmarried men between the ages of twenty-one and forty were eligible-and required them to pass both physical and educational examinations. Upon acceptance, the men enlisted as privates and received at least two months of instruction at Fort Whipple. After an additional six months of duty on station as assistants (later extended to one year), followed by further training at Fort Whipple and appearance before two boards of examination, the men qualified for promotion to "observer-sergeant." After one year's service, an observer could again be called before a board for yet another examination.28 The work of the observer was often demanding. Three times daily he recorded the following data: temperature; relative humidity; barometric pressure; direction and velocity of the wind; and rain or snow fall. The Corps soon added to this list the daily measurement of river depths at stations along many major rivers. The observer also noted the cloud cover and the general state of the weather. Immediately upon completing his observations, the officer prepared the information for telegraphic transmission to the Signal Office in Washington. In a separate journal he recorded unusual phenomena, such as auroral and meteoric displays. In addition to the three telegraphic reports, he made another set of observations according to local time and mailed them weekly to Washington. The Corps also required a separate midday reading of the instruments, but the observer only forwarded the results if they differed greatly from the earlier readings. At sunset he recorded the appearance of the western sky to be used as an indication of the next day's weather. In case of severe weather, an observer could be on duty around the clock, making hourly reports to Washington.29 The extent and the hour of the observations changed over time. Originally the observers took the readings at 0735, 1635, and 2335, Washington time, but the last reading was soon changed to 2300 so that the information could be included in the morning newspapers. Before the introduction of standard time and time zones within the United States, a confusing multiplicity of local times existed. In 1870 there were over 100 such regional times. For the purposes of the meteorological observations, observers used Washington time until 1885. Thereafter the observers took their readings according to eastern time, or that at the 75th meridian west of Greenwich, England. Observers also made local-time readings from 1876 to 1881.30 In addition to long hours, the observer's job involved considerable paperwork: he recorded and forwarded all data to the Signal Office weekly and submitted a monthly digest as well. Record keeping was doubly important because the information often served as evidence in court cases in which weather was a factor. The observer was also responsible for the proper care and functioning of his instruments. If he did not have an assistant, the officer could select and train a civilian to perform his duties when necessary. To ensure a high standard of operation, signal officers periodically inspected the stations. Among those who served in this capacity were two future chief signal officers, Adolphus Greely and James Allen. [47] WAR DEPARTMENT WEATHER MAP, 1875 Despite the Signal Corps' rigorous training requirements, not all observers upheld its high standards. Human nature being what it is, a few proved to be unscrupulous in their work. After examining past submissions in 1890, records officer 2d Lt. William A. Glassford reported that some of the early weather watchers "were so confident of their ability to successfully counterfeit the laws of nature that they wrote up their observations several hours before or after the schedule time."31 One of these presumptuous individuals was Sgt. John Timothy O'Keeffe, or O'Keefe, stationed on Pikes Peak, Colorado. O'Keeffe filled out many of his reports without actually making the observations, believing that the authorities in Washington would not know any better.32 In addition to the demands of the work itself, some observers faced considerable physical danger. The sergeant at Chicago had his office destroyed during the great fire of October 1871, but luckily escaped with his life. During the nationwide cholera epidemic in 1878, signal observers remained at their posts in disease-ridden cities, and three of them died in the line of duty. The remoteness of frontier stations also posed many hardships, including the constant threat of Indian attacks. The observer atop Mount Washington, New Hampshire, faced winters that averaged over 200 inches of snowfall and temperatures well below zero. In February 1872 Pvt. William Stevens, an assistant at that station, was caught in a blizzard on the mountain and perished.33 [48] Once the observers had gathered the weather data, the means of reporting and disseminating it became most important. Like the Smithsonian, the chief signal officer made arrangements with the leading commercial telegraph companies to carry the tri-daily reports. Civilian telegraph experts established special circuits routed to the Signal Office. The initial arrangement with Western Union regarding transmission was only temporary, and at the end of the trial period the company refused to continue service. The House Appropriations Committee held hearings over the dispute and ruled that the company had a mandate to transmit the weather information as government business. The Signal Corps compensated the company, however, at rates determined by the postmaster general.34 When making the daily telegraphic reports, the weather observers used special codes to reduce their length to twenty words in the morning and ten in each of the other two reports, thereby saving the government both time and money.35 Regular transmission of the reports began at 0735 on 1 November 1870 from twenty-four stations stretching from Boston, Massachusetts, south to Key West, Florida, and west to Cheyenne in the Wyoming Territory. In addition to the station atop Mount Washington (opened in December 1870), the Signal Corps soon reached new heights in weather reporting with the station on Pikes Peak that began reporting in November 1873.36 To provide a picture of weather conditions across the country, the observers made their reports as nearly simultaneous as possible. The weather service did not initially make forecasts, and the enabling legislation did not specifically call for it to do so. Eventually general forecasts, referred to as probabilities, emanated from the Signal Office in Washington. Locally, the observers posted bulletins and maps in the offices of boards of trade and chambers of commerce to provide weather information to the public. Post offices also displayed daily bulletins, and observers supplied local newspapers with data. Some communities appointed meteorological committees to confer with the chief signal officer and to serve as a check upon the operations of the local weather station. On the national level, the Signal Office in Washington issued daily weather maps compiled from the reports received from all the stations. It also published the Daily Weather Bulletin, Weekly Weather Chronicle, and the Monthly Weather Review. All were available for sale to the public. Myer estimated that through these various means at least one third of American households received the Signal Corps' weather information in some form. A railway bulletin service, initiated in 1879, enabled stations along many major railroads to display weather information.37 The Monthly Weather Review contained a summary of the meteorological data collected by the Signal Office during the month as well as notes on current developments in the field of meteorology. Until 1884 the chief signal officer published the year's issues in his annual report. The Review became a leading meteorological journal, and it continues to be published today by the American Meteorological Society. To help establish his system, Myer looked to civilian meteorologists for expertise. Among the first he hired was Increase Lapham, who had played an important [49] CLEVELAND ABBE role in getting the weather service started. Lapham worked briefly as supervisor of weather reports on the Great Lakes, and he continued to provide information about shipping disasters to the Signal Office until his death in 1875.38 In January 1871 the Signal Corps hired Professor Cleveland Abbe of the Cincinnati Observatory as a weather forecaster. Abbe had begun issuing forecasts in Cincinnati in 1869, and the Signal Corps adopted many of his methods and procedures.39 Although Abbe had originally been skeptical about the quality of a military weather system, he remained with the Signal Corps' weather service throughout its twenty-year history.40 In addition to forecasting, Abbe founded the Monthly Weather Review and was its editor. Although weather reporting called for a new set of equipment (thermometers, hygrometers, etc.), flags still found a role in the weather-oriented Signal Corps. A red flag with a black square in the center, for example, became known as the "cautionary signal." When flown from observation stations, primarily those on the Great Lakes and the eastern seaboard, it indicated the likelihood of a storm in the vicinity. At night, a red light served as the storm warning. A white flag with a square black center flying above the red flag was known as the "cautionary offshore signal," meaning that winds were blowing from a northerly or westerly direction.41 Weather reporting also led the Signal Corps into a new relationship with the electric telegraph. At least one writer has incorrectly attributed the assignment of weather duties to the Signal Corps in 1870 to the fact that the Corps controlled its own telegraph lines.42 Actually, the Corps did not begin constructing lines until 1873, under authority of legislation approved in March of that year. The act directed the Signal Corps to establish signal stations at lighthouses and to construct telegraph lines between them if none existed. These lines were to work in conjunction with the stations of the United States Life-Saving Service, the forerunner of the Coast Guard. In some cases the Signal Corps located its offices within the life-saving stations.43 During 1873 and 1874 the Corps built lines between Sandy Hook and Cape May, New Jersey, and from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, to Norfolk, Virginia, along some of the most perilous stretches of the Atlantic coast. Leased wires connected these lines with the Signal Office in Washington. Further extensions between Wilmington, North Carolina, and the [50] mouth of the Cape Fear River and from the Delaware Breakwater, at the mouth of Philadelphia Harbor, to Chincoteague, Virginia, brought the total length of sea coast lines to just over 600 miles, a figure that remained about the same throughout the 1880s.44 The Signal Corps filled the critical need for a storm warning system along the Atlantic coast to warn vessels of approaching storms and to aid in the rescue of ships wrecked in the treacherous waters. When a wreck occurred, the Corps opened a special station at the scene to call for assistance and to maintain communication with those still on board the ship. Knowledge of naval and international signal codes enabled Army signal officers to establish communication with ships of any registry. Officers could also signal with flags and torches across breaks in the telegraph lines, a frequent occurrence on the stormy coastline. Their services saved many lives and untold tons of cargo. One of the wrecks to which the Signal Corps gave assistance was that of the Huron, a steamer that ran aground off Nags Head, North Carolina, in the early morning hours of 24 November 1877. Two of the survivors on a raft headed for what appeared to be the masts of fishing vessels but turned out to be the Signal Corps' telegraph poles on the shore. The nearest signal station was at Kitty Hawk, eight miles from the site of the wreck. It was housed in the upper story of the life-saving station, then closed for the season, a fact that severely inhibited the rescue effort. At midmorning, two fishermen brought news of the disaster to the signal station, and the observer, Sgt. S. W Naylor, headed for the scene to assist the victims. He set up a telegraph station on the shore that transmitted over 550 messages through 11 December. Only 34 men out of the crew of 132 survived the wreck of the Huron. Five others, including the superintendent of the Sixth Life-Saving District, lost their lives during the rescue operations, making the Huron one of the worst shipwrecks of the era.45 The following year a signal officer, 1st Lt. James A. Buchanan, on his way to inspect coastal signal stations, was himself a victim of a shipwreck when the schooner Magnolia went down in Albemarle Sound, North Carolina, during a hurricane. Buchanan lashed himself to the gunwale and eventually managed to swim ashore.46 The Signal Corps' telegraph network soon expanded beyond the eastern seaboard. In 1874 Congress enacted legislation directing the War Department to build lines to connect military posts and protect frontier settlements in Texas against Indians and Mexicans. Other acts authorized lines in Arizona and New Mexico and, somewhat later, the Northwest. These lines were intended to serve sparsely settled areas where commercial lines were not yet available. For the most part, soldiers maintained and operated the lines, but the Corps employed some civilians. As the telegraph extended its reach, the weather system also grew, because the operators doubled as weather observers. The Signal Corps' lines achieved their maximum mileage in 1881, when 5,077 miles were under its control. In succeeding years the mileage steadily dropped as commercial lines followed the railroads westward, and by 1891 only 1,025 miles remained [51] under the Signal Corps' supervision. In total, the Corps was responsible for building 8,000 miles of telegraph lines, to include both seacoast and frontier lines.47 First Lieutenant Adolphus W. Greely supervised much of the Signal Corps' telegraph construction. In Texas, where the Army built nearly 1,300 miles of line, one of the major obstacles was the shortage of timber for poles. Greely obtained some from the Rio Grande Valley, about 500 miles from where the lines were being constructed, and even imported juniper poles from the Great Dismal Swamp in Virginia. He later oversaw the construction of 2,000 miles of line from Santa Fe to San Diego, and in 1878 he went to the Dakota Territory to erect a line from Bismarck to Fort Ellis, Montana. The discovery of gold in the Black Hills and the Indian troubles in the area, highlighted by the Custer massacre in 1876, made the need for lines more acute.48 Will Croft Barnes was one of the Signal Corps operators assigned to a western station. Enlisting as a second class private in 1879, Barnes trained at Fort Whipple and, after duty constructing seacoast telegraph lines, was sent to Fort Apache, Arizona, "then about as far out of civilization as it was possible to get."49 Barnes arrived there in February 1880, much to the relief of the previous operator. To Barnes' dismay, the first weather observation had to be made at 0339 for transmission at 0400. Of greater concern to him were the Indian troubles in the area; Indians often cut the telegraph wires, making repairs a risky business. In the summer of 1881 the Army's relations with the Indians became especially tense when a shaman named Nakaidoklini became influential among the Apaches. Anticipating the later Ghost Dance movement of the 1890s, Nakaidoklini preached a doctrine that included the raising of the dead and the elimination of the white man. When the commander of Fort Apache, Col. Eugene A. Carr, was ordered to arrest the medicine man, violence resulted. His followers attacked Carr's party as the soldiers returned to the post following the arrest. Nakaidoklini was killed, along with one officer and three men; four others were mortally wounded and died before reaching Fort Apache. The day after Carr returned to the post, Barnes accompanied the burial party. In the midst of their work, Indians attacked, and soon the fort was under siege. Fortunately, the attackers were driven off, and for his part in the defense Barnes received the Medal of Honor, the second Signal Corpsman so recognized.50 The Signal Corps' weather reporting network gained additional strength in 1874 from the absorption of the Smithsonian's nearly 400 volunteer observers, as well as by an agreement made with the surgeon general to turn over to the Signal Corps the monthly reports made by medical officers. These acquisitions brought to over 800 the total number of reports received regularly by the Signal Office. Naval and merchant vessels also began to feed information into the systems.51 Besides reporting on the weather, Signal Corps observers sometimes relayed other types of information. In 1877 they provided President Rutherford B. Hayes with details about local conditions arising from labor unrest. During the so-called Great Strike-actually a wave of railroad strikes that spread across the nation in [52] MAP OF U.S. MILITARY TELEGRAPH LINES, 1885 the summer of 1877-Chief Signal Officer Myer ordered the observers at key points to report every six hours, and more frequently if necessary.52 Sgt. Leroy E. Sebree, for example, wired from Louisville on 25 July that "The wildest excitement prevails-troops are resting on their arms in City Hall-striking laborers are marching through the city forcing others to join. Every precaution is being taken to prevent serious trouble." Using the information gleaned from his observers, Myer could give the president his own assessment of conditions. On 26 July he cautioned Hayes that the news from Chicago in the afternoon papers seemed to be "purely sensational. The city is reported to be comparatively quiet." Indeed, order returned to most cities within a few days. By 29 July Myer could report to Hayes that "The regular night reports show absolute Quiet everywhere on the Atlantic & Picific [sic] Coast & the interior. The riots seem ended." He also congratulated the president and the secretary of war "on the sucess [sic] and conclusion of this campaign." Some trouble spots remained, and the Signal Corps continued its strike-related reports until 13 August 1877.53 From the beginning the weather service contained an international component. In the 1870s the Signal Corps established several stations in Alaska, only recently purchased from Russia. The Alaskan observers were also naturalists who collected specimens for the Smithsonian. One of these men, Pvt. Edward W Nelson, while stationed at St. Michael, documented the life and culture of the Bering Sea Eskimos.54 Beginning in 1871, Canadian stations exchanged reports with the Signal Corps, and reports received from the West Indies proved especially valuable during the hurricane season. [53] Eventually Myer established contact with many foreign weather offices. In 1873 he attended the first International Meteorological Congress in Vienna where the participants agreed to exchange a daily observation, with the United States assuming the expense of publishing the results.55 By sharing such information, meteorologists could track storms from continent to continent and study weather patterns. In 1875 the Signal Office began publishing the Daily Bulletin of International Simultaneous Meteorological Observations, containing the daily observations made on a given date up to a year earlier. A daily International Weather Map followed in 1878 based upon the data appearing in the bulletin of the same date. Through its weather service, the Signal Corps helped the United States become part of the international scientific community.56 In order to provide these myriad services, the Signal Office worked around the clock. To facilitate its operation, the chief signal officer divided the office into a dozen sections: general correspondence and records; telegraph room; property room; printing and lithographing room; International Bulletin; instrument room; map room; artisan's room; station room; the computation, or fact, room; the study room; and the library. The instrument room, for example, maintained the standard instruments against which all those being sent to the weather stations were compared. The Corps also manufactured new types of equipment, including self-recording instruments to continuously gather data. The Corps' library contained thousands of volumes and pamphlets, many of them gifts from foreign governments and institutions. In addition to maintaining the heavy administrative load of correspondence, the office responded to voluminous numbers of requests for weather information. In 1880 a complement of 110 enlisted men kept the office running.57 Indeed, the burgeoning duties of the Signal Corps created a need for additional personnel. Consequently, the secretary of war authorized increases in its detailed enlisted strength, and by 1874 the Corps comprised 150 sergeants, 30 corporals, and 270 privates.58 The number of detailed officers remained at six as specified in the 1866 legislation. Although Congress in 1874 limited the strength of the Army to 25,000, it did not include the Signal Corps in this total and specified that its strength was not to be diminished.59 But when Congress reduced the size of the Army two years later, in the midst of the depression that followed the Panic of 1873, it no longer exempted the Signal Corps and cut its enlisted force by fifty. In 1878, however, Congress restored the Corps to its previous strength of 450 enlisted men. The new law also provided that two signal sergeants could be appointed annually to the rank of second lieutenant, thus offering some upward mobility for Corps members. In 1880 Congress added 50 privates, bringing the Signal Corps' total enlisted strength to 500, where it remained until 1886.60 By 1880, after a decade of operation under Myer's leadership, the weather service was flourishing. It had grown to comprise 110 regular stations in the United States that reported by telegraph three times daily, and its annual budget totaled $375,000.61 But on 24 August 1880, the man who had contributed so [54] much to the development of the weather system, not to mention having founded the Signal Corps itself, died of nephritis at the age of 51. Myer had become ill in 1879 while traveling in Europe, and his condition gradually worsened. Brig. Gen. Richard C. Drum, the adjutant general, temporarily took command of the Signal Corps following Myer's death, and his signature appears at the end of the 1880 annual report. In honor of the Army's first signal officer, Fort Whipple was renamed Fort Myer on 4 February 1881.62 Death claimed Myer at the peak of his career. He had just received his commission as brigadier general, effective 16 June 1880, putting him on a par with the other bureau chiefs within the War Department. As head of the Signal Corps' weather service, he had become popularly known as Old Probabilities.63 In addition to the sobriquet, Myer received much professional recognition for his public service. Among the numerous awards conferred upon him were honorary memberships in the Austrian Meteorological Society and the Italian Geographical Society; an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from his alma mater, Hobart College, in 1872; and an honorary Doctor of Philosophy from Union College in 1875. To recognize Signal Corps veterans, Myer had founded the Order of the Signal Corps shortly after the Civil War, but this organization no longer exists.64 Col. William B. Hazen became the fourth person to hold the position of chief signal officer, taking office on 15 December 1880. A native of Vermont, Hazen had graduated from West Point in 1855 and then served in Oregon and Texas. During the Civil War he distinguished himself at such battles as Stone's River, Chickamauga, and Atlanta, where he commanded a division in the Army of the Tennessee. In 1865 he received a brevet major generalcy in the Regular Army for meritorious service in the field. After the war he returned to duty in the West. Never one to avoid controversy, Hazen created a sensation when he charged the War Department with corrupt management of the post trader system. The resulting congressional investigations led to the resignation and impeachment of Secretary of War William W Belknap during the Grant administration.65 Hazen also acted as an observer during the Franco-Prussian War, and in 1872 he published a book about military reform, The School and the Army in Germany and France.66 Hazen, promoted to the permanent rank of brigadier general in the Regular Army, quickly made some changes upon taking command of the Signal Corps. To begin, he reorganized the Signal Office into ten divisions that roughly corresponded to the various rooms created by Myer. Unlike Myer, who stressed the practical over the scientific, Hazen shifted the emphasis toward basic research.67 He established, for example, the Scientific and Study Division to prepare special reports and conduct other research projects. Professor Abbe supervised the work of the study room within that division, and he was assisted by three civilians with scientific backgrounds, known initially as "computers" because of the mathemat- [55] ical calculations involved in their work. Topics of inquiry included hurricanes, tornadoes, and thunderstorms. Copies of papers prepared by the study room appeared in many of the chief signal officer's annual reports. To supplement this staff, Hazen called upon several "consulting specialists," among them Alexander Graham Bell and Professor Samuel P. Langley of the Allegheny Observatory in Pennsylvania.68 A committee of the National Academy of Sciences also acted in an advisory capacity as needed by the chief signal officer. To formally present the results of the studies undertaken by the Corps, Hazen introduced a series of professional papers as well as a set of publications known as "Signal Service Notes." He also initiated the compilation of a general bibliography of meteorology. To further meteorological education, members of the study room delivered lectures to the students at Fort Myer. Hazen also directed Professor William Ferrel, one of the assistants in the office, to compile a textbook of meteorology for classroom use. Thus Hazen sought to combine the practical arts of observation, recording, and prediction with the science of meteorology.69 Under Hazen the Signal Corps' work took off in some new directions. To study the upper atmosphere, signal soldiers sometimes accompanied balloonists aloft in order to make observations. A leading aeronaut, Samuel King of Philadelphia, invited Signal Corps personnel to ride in his balloon on several occasions. One such adventurous soldier, Pvt. J. G. Hashagen, accompanied King on a flight from Chicago in October 1881 and ended up eating hedgehog in the wilds of Wisconsin after landing in a cranberry bog. (King had packed no food for the journey.) Hashagen succeeded in making meteorological observations during the flight, but he recommended including condensed soup as part of the equipment for future ascensions.70 During the weather service years the Signal Corps possessed no balloons of its own, but Abbe stressed the need for aerial investigations into weather, and he was prophetic when he wrote in 1884, "As the use of the balloon for military purposes has received much attention and is highly appreciated in Europe, it is probable that this also may at some time become a duty of the Signal Office."71 To raise the standard of personnel, Hazen sought to recruit promising graduates from the nation's colleges. By doing so he hoped "to furnish from the ranks of the Signal Corps, men who may take high standing in the science of meteorology."72 At the same time, some of the Signal Corps' current members were sent to private schools for further education. Pvts. Austin L. McRae and Alexander McAdie of the Boston weather station attended Harvard University to study atmospheric electricity. Pvt. Park Morrill, on duty in Baltimore, took similar courses at the Johns Hopkins University. These schools provided the courses without cost, and other schools located near signal stations offered similar arrangements.73 Hazen encouraged the expansion of weather activities through the establishment of state weather services with which the Signal Corps cooperated. In some cases enlisted men served as assistants to the state directors. These organizations proved especially helpful in distributing weather information to remote agricultural areas. By 1884 fourteen states had their own weather offices, with the six [56] GENERAL HAZEN New England states forming the New England Meteorological Society. Most states had organized weather agencies by 1890.74 The paucity of weather information on the West Coast had long concerned both Myer and Hazen, and in 1885 the Corps improved this situation by opening a signal office for the Division of the Pacific, which encompassed California, Oregon, and Washington. The new office at San Francisco issued forecasts twice daily and distributed them by means of the daily newspapers, the Associated Press, and the Farmers' Bulletin.When necessary, cautionary signals were displayed at several points along the coast. In addition to providing weather information, the division signal officer was directed to repair the telegraph cable between Alcatraz and the Presidio of San Francisco. The harbor's powerful currents and the fact that vessels frequently anchored there made repair and maintenance of the cable an expensive job.75 The Signal Corps' expanding duties required a great deal of office space. By 1882, the Corps occupied rooms in ten different buildings in Washington. Myer had first requested a new building in 1875, and Hazen took up the cause in his annual report of 1882. The State-War-Navy Building (now known as the Old Executive Office Building) had recently opened, and the chief signal officer, along with the other bureau chiefs, had his office there. But the new building could not house all of the Signal Corps' activities. In the absence of congressional action, Hazen repeatedly asked for a fireproof structure to provide protection for the branch's valuable records and property. Second Lieutenant Frank P Greene, in charge of the Examiner's Division in 1886, complained of the condition of his division's quarters. Not only were the rooms "small and dark, cold in winter and warm in summer," but there was also an "ever-present stale, ill-smelling odor, rising at frequent times to a pitch that is all but visible." In 1889 the Signal Corps finally moved to new quarters at 2416 M Street, Northwest, that contained a fireproof vault for its records.76 In many ways success and growth had marked Hazen's tenure. But troubles, some of a serious nature, had also begun to arise. Ironically, given his role in the post trader hearings, scandal rocked Hazen's own bureau when Capt. Henry W Howgate abruptly resigned from the Signal Corps in December 1880. To his cha [57] grin, Hazen soon discovered that Howgate had helped himself to a substantial portion of the Corps' funds. The exact amount was never determined, but it could have been as much as $400,000. Howgate, British by birth, had served with distinction in the Signal Corps during the Civil War. Rejoining the Army in 1867 as a member of the 20th Infantry, he subsequently returned to the Signal Corps where he worked in the Signal Office as property and disbursement officer under Myer. Howgate had hoped to succeed Myer as chief signal officer, but Hazen's friendship with then Senator James A. Garfield helped him win the appointment from President Rutherford B. Hayes. Instead of chief signal officer, Howgate became a fugitive. He fled to Michigan with his mistress and was not tracked down until August 1881. Authorities arrested Howgate and returned him to Washington for trial. Released on bail, he dropped out of sight once more. When found, he was finally placed in jail. But the wily captain was not finished. With the aid of his daughter and his mistress, he escaped again. This time Howgate eluded capture for thirteen years. He was finally seized in New York City in 1894, where he had been posing as a rare book dealer. At his first trial in 1895, the jury found Howgate not guilty, but he was not so lucky when tried on a second indictment and was sentenced to fifteen years in prison at Albany, New York. After five years, he received parole due to good conduct and poor health, and he died shortly afterward in 1901.77 Not surprisingly, Hazen assigned an officer to duty as examiner of accounts in the wake of the scandal.78 Howgate had spent a great deal of the embezzled money on his mistress, but he also used some of it to finance Arctic exploration, an area in which the Signal Corps became involved as part of the First Interpolar Year (1882-1883), the forerunner of what is now known as the International Geophysical Year. Unfortunately, this well-intentioned scientific endeavor became a new source of controversy and even scandal for the Signal Corps. Participating countries established stations around the North Pole to conduct meteorological, geological, and other scientific observations. In the summer of 1881 the United States sent two parties, both led by Signal Corps officers, one to Point Barrow, Alaska, and the other to Lady Franklin Bay on Ellesmere Island in northern Canada, less than 500 miles from the North Pole. The expedition to Alaska, commanded by 1st Lt. Patrick Henry Ray, spent two relatively uneventful years there. The second party, led by 1st Lt. Adolphus W. Greely, met a far different fate. When the scheduled resupply effort failed in 1882, the twenty-five men were left to fend for themselves in the frozen north. A relief expedition the following year, commanded by 1st Lt. Ernest A. Garlington, also failed to reach Greely's party. Garlington, facing a disaster of his own after his vessel sank and most of his supplies were lost, hastily withdrew south, leaving insufficient rations behind to sustain the stranded soldiers. Despite their precarious situation, Greely and his men continued their scientific work. They had also succeeded, during the first year of the expedition, in achieving the "farthest north" up to that time. But their subsequent ordeal was harrowing. When the rescue effort commanded by Capt. Winfield Scott Schley [58] MEMBERS OF THE GREELY ARCTIC EXPEDITION. GREELY IS FOURTH FROM LEFT, FRONT ROW. finally found Greely at Cape Sabine in June 1884, where he had retreated south according to plan, only the commander and six others remained alive, one of whom died soon thereafter. Unfortunately, sensational charges of murder and cannibalism initially overshadowed the accomplishments of the expedition. Greely denied knowledge of such acts and was ultimately exonerated. In 1888 the government published his massive two-volume report, containing a wealth of information about the Arctic. Greely received numerous honors for his work, among them the Founder's Medal of the Royal Geographic Society of London. He also became a charter member of the National Geographic Society, serving as a vice president and trustee of that organization.79 The outspoken Hazen publicly criticized Secretary of War Robert Todd Lincoln for his handling of the Greely affair. When Garlington's rescue mission failed in the fall of 1883, Lincoln had refused to send further assistance that year, leaving Greely and his men to face a third winter in the Arctic. Unwilling to abandon her husband and his men, Greely's wife, Henrietta, aroused public opinion and forced Lincoln to act. The secretary defended his actions in his 1884 annual report and censured Hazen for his criticisms. Ultimately, court-martial proceedings were instituted against the chief signal officer, resulting in a reprimand from President Chester A. Arthur.80 Hazen and Lincoln also disagreed upon another issue, the admission of blacks into the Signal Corps. In April 1884, W. Hallet Greene, a senior at the College of the City of New York, sought to enlist in the Corps. Hazen rejected his application, based on his understanding that black membership in the Army was [59] SIGNAL STATION AT POINT BARROW, ALASKA limited to the two black infantry and two black cavalry regiments. Secretary Lincoln, however, overruled Hazen's action and directed that Greene be accepted. By direct order of the secretary of war, Greene joined the Signal Corps on 26 September 1884.81 These controversial incidents did not help the Signal Corps' reputation with Congress. In an era of cost cutting, when the Army's total budget dropped sharply, the Signal Corps' appropriation had continued to rise, topping a million dollars in 1884.82 This fact alone, in the wake of the Howgate calamity, made the Signal Corps a natural target of congressional scrutiny. Beginning in fiscal years 1883 and 1884 its expenses were separated from those of the Army as a whole, and the categories of its expenditures were itemized for the first time. Hazen appealed this procedure to Secretary of War Lincoln, but received no sympathy. "I deem it prejudicial to the interests of the Army," wrote Lincoln in his 1884 annual report, "that its apparent cost of maintenance should be so largely increased by adding to it the cost of the Weather Bureau service, with which the Army is not concerned."83 When Congress appropriated less than the Signal Corps had requested, Hazen was forced to close a number of meteorological stations. Moreover, the budget cuts prevented the Corps from paying Western Union for transmitting reports from the Pacific coast during May and June 1883. Congress also refused to fund the West Indian stations that were of such importance during the hurricane season. As [60] Hazen complained in his annual report, the elimination of stations reduced the data received for forecasting, thus making predictions less accurate. (The average percentage of correct forecasts for 1883 was 88 percent, an accuracy rate rivaling that of forecasters today.) Other economies included the closing of cautionary signal stations and the dismissal of civilian assistants. Hazen also reduced the size of his annual report by about two-thirds by eliminating many tables and discontinuing the publication of the Monthly Weather Review within its pages.84 The operation of military telegraph lines was also substantially reduced. The Signal Corps abandoned many miles of line, in part because its services had been superseded by commercial companies, but also because Congress had stipulated that enlisted men from the line of the Army could no longer be used as operators and repairmen. Furthermore, line receipts could no longer be applied toward repair and maintenance.85 A new commission to investigate the role of science in the federal government posed an even greater threat to the Signal Corps' operations. Chaired by Senator William B. Allison of Iowa, and hence known as the Allison Commission, it began hearings in 1884. For the Signal Corps, the question was whether its weather duties properly belonged within the military.86 Few men in the late nineteenth century saw any relation between the study of the weather and military operations. As early as 1874 Commanding General of the Army William T Sherman had testified before the House Committee on Military Affairs that the men of the Signal Corps were "no more soldiers than the men at the Smithsonian Institution. They are making scientific observations of the weather, of great interest to navigators and the country at large. But what does a soldier care about the weather? Whether good or bad, he must take it as it comes."87 Hazen defended his program before Allison's committee and reiterated his arguments in his annual reports. But his superiors, particularly Sherman's successor as commanding general of the Army, Lt. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan, condemned the work of the Signal Corps, even its military signaling function. Sheridan had feuded with Hazen since the battle of Missionary Ridge during the Civil War, and he may have allowed his personal animosity to influence his attitude toward the Signal Corps. Secretary Lincoln, who had his own reasons for disliking Hazen, repeated his negative opinion of the weather duties as too expensive and not related to the Army.88 In their report the commission members divided evenly over the question of civilian versus military control of the weather service, and consequently they presented no plan for its separation from the Signal Corps. Thus, for the time being, the Corps retained its weather function but not without some changes being made. One immediate result of the commission's report was the closing of Fort Myer, site of the Signal School for nearly twenty years.89 Furthermore, as recommended by the commission, the new secretary of war, William C. Endicott, ordered the closure of the study room within the Signal Office.90 The Signal Corps' appropriations continued to decrease as Congress placed increasing pressure on the branch in the wake of the Allison hearings. In 1886 [61] GENERAL GREELY Congress authorized an investigation into the Corps' disbursements by the Committee on Expenditures in the War Department. While the committee found no evidence of fraud aside from the Howgate matter, it did feel that "proper economy has not always been observed" and recommended that legislation be enacted that more fully defined the scope of the Signal Corps' duties.91 In the midst of these troubled times, the chief signal officer's health failed, and in December 1886 Capt. Adolphus W. Greely assumed charge of the Signal Office as senior assistant. The following month General Hazen died of kidney trouble, apparently brought on by old wounds received in action against the Comanches prior to the Civil War.92 Captain Greely became the new chief signal officer, receiving a promotion in rank to brigadier general. Although the Signal Corps was beset with difficulties, Greely was a man well qualified to deal with them, having survived much worse situations in his twenty-five years of military service. Educated in the public schools of his native Massachusetts, he graduated from high school in his home town of Newburyport in 1860. The following year, while still only seventeen, he enlisted in the 19th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. During the Civil War he participated in several major battles and was seriously wounded at Antietam.93 When mustered out in 1867, he had attained the rank of captain with a brevet majority. Greely soon joined the Regular Army as a second lieutenant in the 36th Infantry and served in the West before receiving an unexpected detail to the Signal Corps in 1868. As a member of the Corps, he performed numerous duties and achieved world fame as an Arctic explorer. Greely became chief signal officer at a critical point in the Signal Corps' history. Denounced both within the War Department and in the halls of Congress, the branch saw its future clouded in doubt. For the immediate present at least, it continued to operate primarily as the nation's weather service. While Greely generally carried on the weather duties as inherited from Hazen, he did institute some changes. One of these was the addition of predictions of the force of storms, as called for in the 1870 joint resolution. This service began on 1 September 1887 with the display of flag signals to indicate whether a storm was to be light or severe and whether the center had reached or passed the weather [62] station. Signals also indicated the quarter from which winds could be expected. Greely relied much more heavily than his predecessors on volunteer observers, and their ranks grew substantially under his leadership. Thus, while the number of regular stations declined during this period, the total number of weather-related stations continued to increase due to the expansion of such services as special river stations and rainfall and cotton region stations that were manned by civilian volunteers. (Such volunteers are, in fact, still a vital component of the nation's weather reporting system.)94 The availability of trained personnel was another significant issue. The discontinuance of the Signal School at Fort Myer meant that Greely had to send untrained men to operate the regular weather stations, and the observer-sergeants became responsible for teaching their new assistants.95 Meanwhile, the legislative restriction on the number of officers detailed to the Signal Corps led to the eventual discharge of many of those who were knowledgeable about weather duties. This situation had a negative impact on weather forecasting, a skill which could only be learned by experience and practice. The loss of expert forecasters in the Signal Office resulted in a decline in the accuracy of the weather predictions by about 7 percent. Although part of the decline could also be attributed to the fact that the time period of the forecasts had recently been increased from twenty-four to thirty-two hours, the situation provided the Signal Corps' critics with further ammunition in their quest for change.96 In 1889 the Corps for the first time allowed some local observers to make forecasts for their area for the next twentyfour hours.97 Previously, all forecasts had been issued either from the Washington or the San Francisco office. With these increased responsibilities, Greely stressed the need to select well-qualified recruits. To obtain such men, the Signal Corps still required a written examination as well as recommendations of good moral standing and general character. Beginning on 1 July 1888 Greely established a new system of meteorological observations. He replaced the tri-daily observations with two made at 0800 and 2000, 75th meridian time (or eastern time). River observations would be made at 0800, 75th meridian time. Sunset observations would be replaced by a prediction made at 2000 as to whether rain would fall during the next twenty-four hours, based upon prevailing atmospheric conditions.98 Greely also modified the Signal Corps' weather publications in ways that proved to be very popular. In 1887 the Corps began issuing a weather crop bulletin each Sunday morning from March to October. During the off-season it appeared monthly. The bulletin provided a summary of weather conditions for the previous seven days and their effect upon such major crops as corn, cotton, tobacco, and wheat. Farmers were pleased, and many metropolitan newspapers published the information as well.99 Other projects were more scientific. The Signal Corps finally completed one of its major long-term enterprises, the publication of a general bibliography of meteorology, containing 65,000 titles, begun under Hazen in 1882.100 Despite the lack of funds, the Signal Corps also sent a display to the Paris Exhibition of 1889. [63] The presentation emphasized the Corps' weather duties and featured a small array of instruments as well as sets of the service's publications and charts. The daily weather map drew special attention, and the judges were impressed enough to award the exhibit three grand prizes.101 To increase the Corps' efficiency, Greely favored streamlining the force. In 1886 Congress had reduced the branch's enlisted strength to 470 and further cut the number in 1888 to 320. But 101 of the discharged men simply changed their standing from enlisted to civilian and continued to work for the weather service.102 Greely, however, felt that a further cut in the enlisted ranks would be beneficial, and he recommended bringing the total down to 225. He also favored replacing most enlisted assistants at weather stations with civilians and eliminating the rank of second lieutenant from the Corps' structure. Congress, however, made no further reductions in the Corps' enlisted strength.103 Officers continued to be detailed to the Signal Corps from the line, but their numbers did not vary greatly throughout the remainder of the weather service period. In 1883 Congress authorized the detail of up to ten officers, exclusive of the second lieutenants provided for in 1878 and those detailed to Arctic service. Thereafter the number steadily declined, falling to a low of four in 1885 and leveling off at five from 1886 through 1890. Likewise, Congress set a ceiling on the number of second lieutenants within the Corps. The number rose to sixteen in 1886, but fell to fourteen in 1888 and remained there for the rest of the weather service years.104 Despite the efforts to restructure and economize, the question of the status of the Signal Corps (or the Signal Service, as it was often called in this period) finally came to a head. In 1887 Secretary of War Endicott stated in his annual report that because of its concentration on weather duties the Signal Corps could no longer be relied upon for military signaling.105 Further pressure came from Congress in the form of a movement to raise the Department of Agriculture to cabinet rank. Senator Allison, among the leaders of this endeavor, favored placing the weather service within that agency. But the initial efforts to pass legislation that included the transfer of the weather duties were unsuccessful, and in 1888 Congress created the new executive department without them.106 Given the prevailing political climate, Chief Signal Officer Greely knew that the Signal Corps must relinquish its civil duties in order to survive. On a practical level, however, separating the work of the soldiers from that of the civilians would be difficult, because their responsibilities were so intertwined. Although the Corps had managed to retain its weather mission for the moment, its ultimate loss appeared inevitable, for the winds of change were blowing briskly.107 Military Signals Weather the Storm While the performance of military signaling faded into the background in the years after 1870, it did not disappear altogether. Until the closing of the school at [64] Fort Myer in 1885, signal soldiers continued to receive training in field signaling. Upon Hazen's recommendation, the adjutant general issued general orders in October 1885 directing that all post commanders provide signal instruction, a revival of the system practiced for a time without great success under Myer. These orders required commanders to keep not less than one officer and three enlisted men constantly under instruction and practice in signaling at each garrison in the United States.108 When Greely became chief signal officer in 1887, he found the system no more successful than before. He noted in his 1888 annual report that one-quarter of the Army's regiments lacked any signal instruction program, while in one-half of the regiments practically no signal training had taken place. This lack of preparation "simply indicates the practical abolishment of this Corps for any future war, since an efficient force for signaling could not be instantly created."109 Conditions improved in 1889 when the Army revised its regulations in relation to signal training to make department commanders responsible for instruction and practice in military signaling for the line officers and enlisted men in their departments. The commander was to appoint an acting signal officer at each post to conduct instruction and supervise field practice for at least two months each year. "Constant instruction will be maintained until at least one officer and four enlisted men, of each company, are proficient in the exchange of both day and night signals by flag, heliograph, or other device." Furthermore, the department commander was authorized to designate an officer on his staff as the departmental signal officer.110 The construction of practice telegraph lines at most Army posts provided further incentive and opportunity for soldiers to learn at least the rudiments of signaling. Greely maintained a list of the most capable men in case he needed to call upon their expertise to supplement the Corps during an emergency.111 The growing professionalism within the Army during the closing decades of the nineteenth century significantly affected signal training. In 1881 General William T. Sherman, commanding general of the Army, created the School of Application for Cavalry and Infantry at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. After an uncertain start, the school evolved into a true postgraduate course in the profession of arms, with signaling becoming part of the curriculum in 1888.112 In 1891 the Cavalry and Light Artillery School at Fort Riley, Kansas, was established, and signal training comprised part of the curriculum from the beginning. Also located at Fort Riley was a school for the instruction of signal sergeants. It offered a sixmonth course consisting of four months of classroom instruction and two months of practical application covering electricity, military surveying, telegraphy, telephony, and signaling.113 The signal courses at Riley and Leavenworth at least partially compensated for the loss of the separate signal school. In the aftermath of the Allison hearings, Hazen established a Division of Military Signaling within the Signal Office in June 1885 and placed it under an officer whose duties included the care and improvement of the field telegraph train and other signal apparatus, the preparation of a signal manual, and the [65] supervision of the theoretical and practical instruction of signal officers and enlisted men. The new division also collected information from American and foreign sources relating to signaling. After leading the world during the Civil War, the United States Army Signal Corps had fallen behind its European counterparts. The Swedish government, for example, had developed a smaller and lighter field telegraph train, while the U.S. Signal Corps' equipment had improved little since the immediate postwar period.114 Instruction in its use had continued at Fort Myer until 1883 when the Corps' budget lacked an appropriation for the necessary horses. While signal soldiers still learned telegraphy, the train had been rendered immobile.115 After six years of neglect, the Signal Corps in 1889 had only enough equipment to outfit two trains. At Washington Barracks, D.C. (now Fort Lesley J. McNair), where some of the equipment was stored, the Potomac River rose so high that lances floated from the truck. First Lieutenant Richard E. Thompson, in charge of the Division of Military Signaling, wrote that "We have the shadow rather than the substance of a field equipment."116 Because the Corps lacked the money for new equipment, it made some efforts to adopt the Army wagon or ambulance for use in carrying the telegraph apparatus. In 1891 Chief Signal Officer Greely sent a field train to Fort Riley to be used in the signal training being offered there.117 In the area of visual signals the Signal Corps had made a few improvements since the Civil War. The signal flags remained unchanged, but the Corps had tried to improve the torch using such new materials as asbestos and brickwood, a mixture of clay and sawdust. Flash lanterns began to replace torches, however, as they gave off a much brighter light that could be seen at greater distances. To facilitate the reading of visual signals, the Corps worked on the development of a binocular telescope that combined the extensive field of the marine glass with the power of the telescope. Although patented in 1880, incandescent lamps had not yet been perfected sufficiently for signaling purposes.118 In the Southwest, where the Army spent most of the post-Civil War years engaged in Indian campaigns, the hot, dry climate provided ideal conditions for visual signaling. The heliograph, a device that communicated by using a mirror to direct the sun's rays, was perfectly suited for this environment and had a much greater range than signal flags. Such an instrument had been used successfully by the British in India, and the Signal Corps apparently began studying its possibilities about 1873. Signal soldiers had practiced using the heliograph at Fort Whipple, Virginia, in 1877 and flashed messages a distance of thirty miles.119 Nearly ten years passed, however, before the Army used the heliograph in a major campaign. In 1886 Brig. Gen. Nelson A. Miles began operations against the Apaches under Geronimo in the Southwest. Miles knew of the British experiences with the heliograph and requested that Hazen send a detachment of men skilled in its use.120 The chief signal officer sent a detachment of eleven men equipped with 34 heliographs, 10 telescopes, 30 marine glasses, and an aneroid barometer. They set up a heliograph system in Arizona and New Mexico that Miles praised as "the most interesting and valuable ... that has ever been estab- [66] U.S. SIGNAL SERVICE

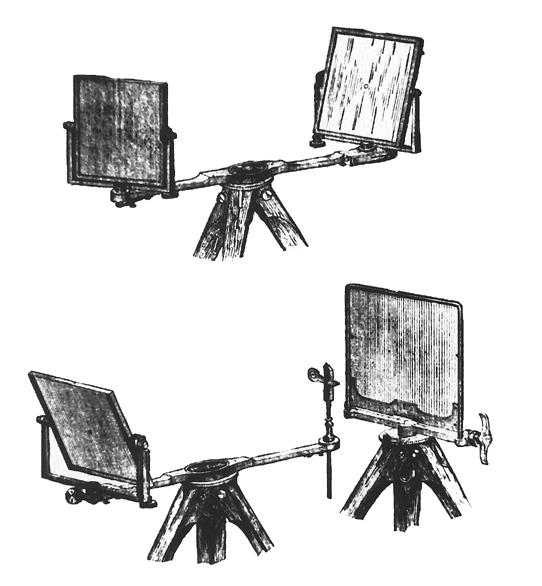

HELIOGRAPH. Clockwise from top, HELIOGRAPH