CHAPTER IV

The Signal Corps Takes to the Air

Above and beyond the branch's work with balloons, the air took on increased importance for the Signal Corps between 1904 and 1917. During the opening decade of the new century, man realized one of his most ancient dreams-to fly with wings. In addition, the atmosphere assumed new significance as a communications medium. Scientists strove to perfect the broadcast of voice and music by means of wireless telegraphy, better known as radio. Mankind was now "on" the air as well as "in" it. Both technologies possessed great military potential. Although soldiers took some time to fully recognize their value, the Signal Corps, in its search for new and improved forms of communication, introduced both the airplane and the radio into the Army.

International crises accelerated the drive for technical innovation. In Europe, war broke out in August 1914. Closer to home, the United States moved toward confrontation with its southern neighbor. Border clashes became a common occurrence from 1911 onward as Mexico endured bloody revolution and civil war. Tensions culminated with the Mexican Expedition of 1916. While fortunately falling short of a full-scale conflict, the campaign provided the Signal Corps with a laboratory for testing its aerial equipment, and the Army itself garnered valuable experience for the difficult years that lay ahead.

Organization, Training, and Operations, 1904-1907

The years 1904 to 1907 constituted a period of institutional change for the Signal Corps. Like the Army as a whole, the Signal Corps felt the effects of the Root reforms. On a doctrinal level, Army leaders began to consider integrating Signal Corps operations with those of the Army's combat arms in what would later be called combined arms warfare.1 On a more practical level, new and improved communications devices made their way into the Signal Corps' inventory, even as it supported military operations at home and abroad.

The Signal Corps also continued to cope with its long-standing personnel problem, and its overseas responsibilities placed an enormous strain upon its limited manpower. To provide relief, Congress expanded the Corps' enlisted strength in April 1904 to 1,212 men, an addition of 402 men or nearly 50 percent of its previous strength of 810. This increased complement included thirtysix slots in the new category of master signal electrician. These men, selected through the examination of first-class sergeants, performed a variety of duties

[119]

to include ballooning, cable splicing and laying, telegraphy, telephony, and working in power plants.2

The authorized number of Signal Corps officers remained forty-six. Chief Signal Officer Greely continued to lament the Corps' low percentage of fieldgrade officers, which allowed only a few men to receive promotions within the branch. Nevertheless, the Corps continued to perform exemplary service and in 1904 received praise for its work in Alaska from the new Secretary of War, William Howard Taft. Taft singled out General Greely for special commendation.3

One of the Root reforms, however, exacerbated Greely's personnel difficulties. The Army Reorganization Act, signed into law by President McKinley on 2 February 1901, eliminated permanent appointments to staff departments or corps. Officers would be detailed to the staff for four years and then serve for two years with the line before again becoming eligible for staff duty.4 In theory, this system provided more officers with the opportunity to gain staff experience, while the alternating tours with line units kept them from becoming too entrenched in the bureaucracy and ignorant of conditions within the line. Unfortunately, few chose to serve their detail with the Signal Corps. Despite efforts to secure volunteers, Greely had to resort to conscription to obtain the needed officers. Of the sixteen men detailed as of 1905, he explained, "fully one-fourth have endeavored to evade service through personal or political influence."5 As in past attempts, the detailing process, even in its new guise, did not prove very satisfactory for the Signal Corps. The chief signal officer continued to request that Congress increase the Corps' officer strength, but to no avail.

In addition to staff-line rotation, the improvement and standardization of education throughout the Army constituted one of the main objectives of the Root reforms. Beginning with the establishment of the Army War College in 1901, the War Department created a tier of service schools. As part of this system, the Signal School opened at Fort Leavenworth on 1 September 1905, while the school at Fort Myer closed. The inclusion of a separate signal school at Leavenworth explicitly recognized that the Signal Corps constituted a distinct branch of the Army.6

The Signal School was only one of several that comprised what became known as the Leavenworth Schools. It shared the post with the Army Staff College, the Infantry and Cavalry School (renamed in 1907 as the School of the Line), and, in 1910, the Field Engineer School. The officers attending the Leavenworth Schools received signal instruction as part of their curriculum, thus becoming familiar with the Signal Corps' role as part of the combined arms team.7

Maj. George O. Squier became the first head of the new Signal School, with the title of assistant commandant. (The commandant of the Staff College, Brig. Gen. J. Franklin Bell, also served as commandant of all the schools at the post.) The chief signal officer could recommend up to five Signal Corps officers for attendance each year. Officers from other branches as well as from the National

[120]

Guard could also enroll. The course of instruction included visual, acoustical, and electrical signaling; electrical and mechanical engineering; aeronautics; photography; topography; and foreign languages.8 The officers and men of Company A, Signal Corps, served as school troops, conducting exercises to demonstrate practical applications. The school's graduates would, ostensibly, provide the Signal Corps with the trained officers it needed.

In the field, however, signal training in line units remained problematical. In 1905 the Signal Corps consisted of 11 provisional companies: 6 in the United States, 2 in Alaska, and 3 in the Philippines.9 Usually less than half of the Army's nine geographical departments within the United States had a full-time signal officer, and Army regulations still contained the requirement that two men in each company, troop, and battery maintain competence in flag signaling.10 The Corps continued, however, to issue kits containing two-foot flags and field glasses, with over three hundred such kits having been distributed by 1907.11 Yet the increasingly technical nature of the Corps' operations demanded specialized training and a better distribution of signal personnel.

Consequently, the chief of staff recommended and the secretary of war approved a plan in 1905 to station a signal company in each of the Army's four geographical administrative divisions. (Each division contained two or more departments, and each department comprised several states or territories. The Philippines constituted a fifth division.) The new stations selected were Fort Wood, on Bedloe's Island in New York Harbor, for the Atlantic Division; Omaha Barracks, Nebraska, for the Northern Division; Benicia Barracks, California, for the Pacific Division; and Fort Leavenworth for the Southwest Division. Fort Wood, manned by Company G, Signal Corps, housed the school for fire-control work and submarine cables and became the home of the Corps' East Coast cable ships, the Joseph Henry and the Cyrus W. Field. Company G's duties included the care and lighting of the island's most famous resident, the Statue of Liberty.12 Companies B and D, Signal Corps, garrisoned Omaha Barracks where the instruction of enlisted men and the ballooning activities, formerly located at Fort Myer, continued. Benicia Barracks, home of Companies E and H, Signal Corps, served as the rendezvous point for men going to and returning from the Philippines and Alaska. Finally, at Fort Leavenworth Company A handled the departmental duties in addition to its work at the Signal School.

Under the Root reforms, the War Department General Staff became the Army's planning and coordinating agency, and the development of unit organization formed an important aspect of the General Staff's plans for future wars. In 1905 the War Department published the Army's first Field Service Regulations, which provided for the formation of provisional brigades and divisions in the event of mobilization. While European armies used the corps as their primary unit, the division became the U.S. Army's basic combined arms unit, containing all the types of smaller units necessary for independent action. Signal troops were included among them.

[121]

Although the Signal Corps for many years had grouped its personnel into provisional companies for administrative purposes, the chief signal officer had never received statutory authority to organize permanent tactical units. (The Regular Army signal companies formed during the War with Spain had been established under orders of the chief signal officer.) According to the 1905 Field Service Regulations, a division would include a signal company comprising 4 officers and 150 enlisted men. These men would be divided into detachments to provide corpslevel communications, visual signaling, and the construction, operation, and repair of telegraph and telephone lines.13 While the Army never fully implemented these regulations, they represented an attempt to prepare for future conflicts, rather than to rely on hastily organized forces as the nation had done during previous wars.14

Although he still lacked legislative authority, the chief signal officer issued a circular in October 1907 that outlined a provisional organization for divisional signal companies. Each division would contain three signal companies of four officers and one hundred men. These companies were differentiated by function into field, base, and telegraph companies: A field company operated tactical lines of communication; a base company provided strategic communications; and a telegraph company served the division's administrative communication needs.15 The chief signal officer provisionally organized Companies A, D, E, and I as field signal companies, but the shortage of men and officers limited them to only about three officers and seventy-five men each. A fully equipped company could establish forty miles of telegraph lines, thirty miles of electrical buzzer lines, two portable wireless telegraph stations, and six visual stations.16

On an operational level, the Signal Corps continued to perform a wide variety of duties at home and abroad. In 1904 it still operated over five hundred miles of military telegraph lines within the United States that handled over forty-one thousand messages during the year. But the total mileage was steadily decreasing, and by 1907 it stood at less than one hundred fifty miles.17 The discontinuance of the more than two hundred miles of line between Forts Brown and McIntosh, Texas, in 1906 (the War Department having abandoned both posts in that year) contributed significantly to this precipitous drop. While domestic military telegraph duties declined (the Corps still operated sizable systems in Alaska and the Philippines), the installation of post telephone systems kept signalmen busy. These systems were divided into two classes: those for coast artillery fire control and those for administrative purposes. By 1907 the Corps had installed telephone systems at fifty-nine of the seventy-one posts within the continental United States, in addition to those already in operation at coastal fortifications. The demand for telephones led the secretary of war to limit the number that could be installed at each post. While the Signal Corps did not maintain and run these post systems, it did retain the right to inspect them.18

On 9 April 1904, Secretary Taft relieved the Signal Corps of one of its duties, the supervision of the War Department library. In the eleven years that the branch had managed the library it had doubled the number of volumes, eliminated the fictional works in the collection by distributing them among Army post libraries, and

[122]

GENERAL ALLEN

generally introduced modern library methods. Control of the library passed to the Military Information Division of the General Staff.19

As the United States Army sought to modernize, foreign armies served as important sources of information and new ideas. The War Department learned a great deal from the observations of officers sent to witness the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905.20 The Japanese victory stemmed in large part from their superior use of modern battlefield techniques, including efficient means of communication. Like the Americans, the Japanese had studied such recent conflicts as the War with Spain and the Boer War, and they effectively applied the lessons learned. In addition to tactical and strategic telegraphy, they made considerable use of the field telephone,

especially to control the indirect fire of field artillery. The United States Army also experimented with this technique and in 1905 adopted indirect fire as the preferred method of employing field artillery. The Signal Corps provided the necessary telephones to field artillery units.21 The Russians, meanwhile, made greater use of wireless than the Japanese, but their personnel lacked adequate training. Moreover, wireless technology had not yet been perfected.22

The Signal Corps ended an era on 10 February 1906 when President Theodore Roosevelt promoted Chief Signal Officer Greely to major general and the War Department assigned him to command the Pacific Division with head quarters at San Francisco. He had guided the Signal Corps through its transition from the controversial weather service period into the modern electrical age. Greely's tenure of nearly nineteen years stands as the longest of any chief signal officer in history. His lifetime of "splendid public service" was recognized nearly thirty years later, on his ninety-first birthday, when Greely received the Medal of Honor.23

Greely passed the torch to Col. James Allen, who had been serving as his assistant in Washington. Allen was a West Point graduate, class of 1872, and had joined the Signal Corps in 1890. His accomplishments since then had been many and varied. In recommending Allen for the appointment, Greely referred to him as "one of the ablest and most competent officers I have known in 45 years of active service."24 Allen's promotion to brigadier general was concurrent with Greely's elevation in rank.

[123]

Greely had hardly pinned on his second star when he was faced with a major challenge: the San Francisco earthquake during the early morning of 18 April 1906 and the subsequent fire that raged for four days. Learning of the disaster while on his way East for his daughter's wedding, Greely hurried back to the devastated city, arriving on the 22d. In his absence, troops under Brig. Gen. Frederick Funston, commander of the Department of California, had assisted with the firefighting, helped to maintain law and order, and undertaken the administration of emergency relief services.

Amid the chaos, the maintenance of communications posed a difficult problem. The earthquake had knocked out the city's telephone system and destroyed virtually all of its telegraph lines. In the immediate aftermath of the disaster the only remaining communication with the outside world was provided by "one or two insecure wires to the East operated by the Western Union and Postal Telegraph Companies from their shattered main offices."25 Later in the day flames destroyed even these tenuous connections, and the city's half million residents found themselves isolated from the rest of the country. Fortunately, the Signal Corps could step in during the emergency. By 1000 on the 18th, about five hours after the earthquake occurred, Capt. Leonard D. Wildman, the departmental signal officer, had established a field telegraph line between the Presidio and the outskirts of the fire. With the aid of the Corps' operators, instruments, and material, the commercial telegraph companies gradually restored operations.

Luckily, due to the new stationing plan, the Signal Corps had storehouses and two companies (E and H) located at Benicia Barracks, only thirty-six miles away. Local National Guard units, to include the 2d Company Signal Corps, assisted in the relief efforts. This company laid telegraph lines connecting the city's Guard headquarters with subordinate units.26 On 1 May, Company A, Signal Corps, commanded by Capt. William Mitchell, arrived from Fort Leavenworth to provide additional men and material. They remained on duty in the city for a month.27 In the burned areas, military telegraph lines remained in use until 10 May. Citywide, Wildman set up a system of forty-two telegraph offices and seventy-nine telephone offices that connected all the military districts, federal buildings, railroad offices and depots, the offices of the mayor and governor, and other locations as needed.28 Because the cables in the harbor had been destroyed, the Signal Corps employed visual signals, including flags, heliographs, and acetylene lanterns, to communicate between Angel Island and Alcatraz. To restore the cables, the Corps called upon the Burnside, usually on duty in Alaska.

General Funston, in his report, commended Wildman for his proficiency and ability "in establishing and maintaining telegraph and telephone communication under the almost impossible conditions existing during the conflagration and immediately afterwards." Greely echoed Funston's praise.29

A modern machine, the automobile, proved especially useful during the emergency, when the streets were full of rubble and the city's famed cable cars

[124]

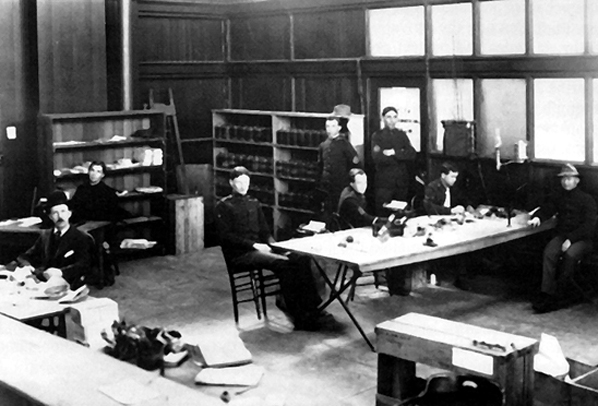

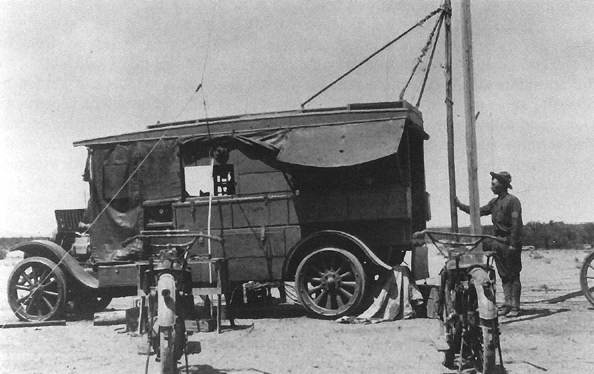

SIGNAL CORPS TELEGRAPH OFFICE, SAN FRANCISCO, 1906

out of service. The Signal Corps had purchased four commercial automobiles in the previous two years, and at the time of the earthquake one of them was in San Francisco.30 On the first day alone, this redoubtable vehicle traveled over two hundred miles carrying not only messages but signal equipment, medical supplies, food, the sick and wounded, and just about anything that needed hauling "over broken and piled-up asphalt pavement, through walls of flames, under or through networks of trailing wires and over piles of brick and broken cornices lined with scrap tin, and with sharp splinters of iron and wood everywhere."31 While the automobile performed well during this crisis and the Signal Corps experimented during this period with an auto-telegraph car, neither the Corps nor the Army made extensive use of motor vehicles until the Mexican Expedition, just prior to America's entrance into World War 1.32

The year 1906 continued to be an eventful one for the Signal Corps. That fall U.S. troops once again landed on Cuban soil, four years after the end of the military occupation that had followed the War with Spain. The deployment of the "Army of Cuban Pacification" was authorized by the Platt Amendment, embodied in the Cuban Constitution of 1901, which granted to the United States the right to intervene to preserve Cuban independence.33 The United States invoked the amendment in September 1906 when a revolt by the opposition party caused the Cuban republic to collapse. Secretary of War Taft, already in Cuba as part of

[125]

a peace mission, established a provisional government with himself as temporary governor. Pending the arrival of the Army, about two thousand marines landed to maintain order and protect property. In October the occupation force of 5,000 Army troops arrived. One thousand marines making up the 1st Provisional Marine Regiment remained under Army command, bringing the total American strength to 6,000.34

Army forces in Cuba included Company I, Signal Corps, commanded by Capt. George S. Gibbs. The newly organized unit comprised a total of 4 officers and 153 enlisted men. It also contained the Corps' first field wireless platoon, which soon established communication between Camp Columbia, the Army's headquarters west of Havana, and the fleet in Havana Harbor. With the help of a 100-foot antenna, the platoon also established communication with Key West, ninety miles away. In the field the Corps sometimes used portable wireless sets (weighing over four hundred pounds and carried by mules) instead of temporary telegraph or telephone lines. Signalmen also operated telephone and telegraph lines in Havana, including those belonging to the Cuban government, and connected the American troops at their stations throughout the island.35 Company I returned to the United States in January 1909 as the American intervention came to an end with the restoration of Cuban self-government.36

Simultaneously, in the Philippines, sporadic fighting continued in the ongoing attempt to bring the primitive peoples of the southern islands under American control. On the island of Jolo a band of fierce Moros had taken refuge atop Mount Bud-Dajo, venturing forth on occasion to launch raids in the surrounding countryside. Fearing a worsening of the situation, the Army decided to send troops against them. During this operation, on 7 March 1906, 1st Lt. Gordon Johnston joined the list of Signal Corpsman to have earned the Medal of Honor when he "voluntarily took part in and was dangerously wounded during an assault on the enemy's works."37 Ironically, Johnston, commissioned in the Cavalry, numbered among those line officers unhappily detailed to the Signal Corps. He had tried to secure relief from his detail, but Chief Signal Officer Greely had denied his request. Following his distinguished service in the Philippines and after recovering from his wounds, Johnston finally found himself back in the Cavalry in 1907.38

In both Cuba and the Philippines, the Signal Corps increasingly relied upon buzzer lines which used telephones to transmit Morse code. (The high-pitched hum of the telegraphic signals as heard through the telephone receiver has been likened to the sound of "a giant mosquito singing to its young.")39 The value of the buzzer lay in its ability to operate successfully over poorly insulated or even bare wires where an ordinary telegraph would fail. Buzzer lines could also be employed as regular telephone lines. A smaller version of the device, known as the cavalry buzzer, could be carried on horseback.40 Maj. Charles McK. Saltzman, a future chief signal officer, wrote in 1907 that "The day of the mounted orderly has passed, and the most important enlisted man in the fifty-mile battle line of the future will be the man behind the buzzer."41

[126]

During the early years of the new century, the Signal Corps had undergone modernization in response to the reforms implemented by the General Staff and the advances being made in communications technology. In a world that was becoming increasingly professionalized there remained, however, room for achievement by amateurs. Two brothers from Dayton, Ohio, owners of a bicycle shop, finally solved the long-standing problem of heavier-than-air flight through hard work and ingenuity. Chief Signal Officer Allen and the Signal Corps, along with the rest of the world, would soon become well acquainted with Wilbur and Orville Wright and their flying machine.

The Signal Corps Gets the Wright Stuff

Since 1892 lack of funds and facilities had continually hampered the Signal Corps' aerial operations. Although the Corps had constructed a balloon house at Fort Myer in 1901, Chief Signal Officer Greely never succeeded in getting a gas generating plant built there. With the closing of the school at Myer in 1905, Greely sent the Corps' aerial equipment to Benicia Barracks pending completion of new facilities at Fort Omaha.

Meanwhile, several factors combined to spur a revival of the Army's aeronautical program. In particular, a growing interest in aeronautics among the general public led to the formation of the Aero Club of America in 1905. This organization sponsored many aerial events and administered the licensing of pilots.42 Its early membership included two Signal Corps officers, Maj. Samuel Reber and Capt. Charles deForest Chandler. Moreover, another soldier, 1st Lt. Frank P Lahm, then attending the French cavalry school at Saumur, won the first Gordon Bennett international balloon race held in France in 1906.43

Under Chief Signal Officer Allen, aviation assumed a more prominent role in the Signal Corps' mission. His assistant, Maj. George O. Squier, was instrumental in bringing about this change. While at Leavenworth Squier had pursued the study of aeronautics in addition to his other scientific interests. He recognized the importance of the work being done by the Wright brothers and closely followed their progress. When he came to Washington in July 1907, Squier brought not only his expertise but his extensive list of contacts within the scientific community at large and the aeronautical community in particular. Shortly after Squier's arrival Allen issued a memorandum on 1 August 1907 creating an Aeronautical Division within the Office of the Chief Signal Officer, which was to have charge "of all matters pertaining to military ballooning, air machines, and all kindred subjects."44 Captain Chandler became the division's head. In the fall of 1907 the Corps shipped its balloon equipment from Benicia Barracks to Washington so that Chandler and the men assigned to his division could conduct ascensions. During some of these flights they successfully experimented with the reception of wireless messages in the balloon car.45 Meanwhile, Lieutenant Lahm, who remained in France while recovering from illness, received orders from the War Department to observe the aeronautical sections of the British and German

[127]

armies. He exceeded his orders and visited the Belgian and French armies as well. On his return to the United States, Lahm reported for duty to the Signal Office.46 In 1908 the Corps completed its new balloon facilities at Fort Omaha, which included a plant for hydrogen generation. The proximity of this post to the Signal School made it possible for the students at Leavenworth to travel there for aeronautical instruction.

Although their accomplishment remained relatively unknown, the Wright brothers had demonstrated the feasibility of heavier-than-air flight nearly five years earlier, in December 1903.47 In fact, they had offered to sell their airplane to the United States government through the Board of Ordnance and Fortification on two occasions in 1905. That body, still skeptical about flying machines after supporting Samuel P Langley's failed project two years earlier, had ignored the Wrights' offers. Rebuffed at home, the Wrights pursued opportunities to sell their plane in Europe. Finally, in 1907, the War Department reopened communication with them. Wilbur Wright appeared before the Board of Ordnance and Fortification in December 1907 and convinced the members and Chief Signal Officer Allen, who also attended, of the legitimacy of their claims. Subsequently, on 23 December 1907, the Signal Corps issued an advertisement and specifications to solicit bids for a heavier-than-air flying machine. The Corps' requirements included that the machine carry two persons, travel at least forty miles per hour, and be capable of sustained flight for at least an hour. The Corps also preferred that the machine be compact enough to be dismantled for transport in an Army wagon and readily reassembled. While the specifications closely followed the capabilities of the Wrights' airplane, the Corps also consulted with other scientists and engineers, to include Alexander Graham Bell, prior to their issuance.48

Despite the advent of heavier-than-air flight, the Signal Corps continued its work with lighter-than-air craft. Early in 1908 the Signal Office issued another set of specifications, these calling for a dirigible, that is, a sausage-shaped, engine-powered balloon that could be steered, later known as an airship. Europeans had taken the lead in dirigible development, and the name of the German Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin was most closely associated with this type of flying machine. The Signal Corps required the dirigible to also carry two persons and travel at least twenty miles per hour.49 Although it had previously lost a considerable sum by backing Langley, the Board of Ordnance and Fortification granted funds to purchase both the heavier-than-air and the lighter-than-air craft because the Signal Corps had no money within its own budget to do so.50 The flight trials of both the dirigible and the airplane were scheduled to be held at Fort Myer during the summer of 1908.

Not surprisingly, the Wright brothers numbered among the forty-one applicants submitting plans for a flying machine to the Signal Office. The Corps received many unusual proposals, including one from a prisoner in a federal penitentiary who promised to furnish an acceptable plane on the condition that the Army secure his release from prison. Of the three serious bidders who complied with the specifications, only the Wrights delivered a plane to Fort Myer for the flight trials.51

[128]

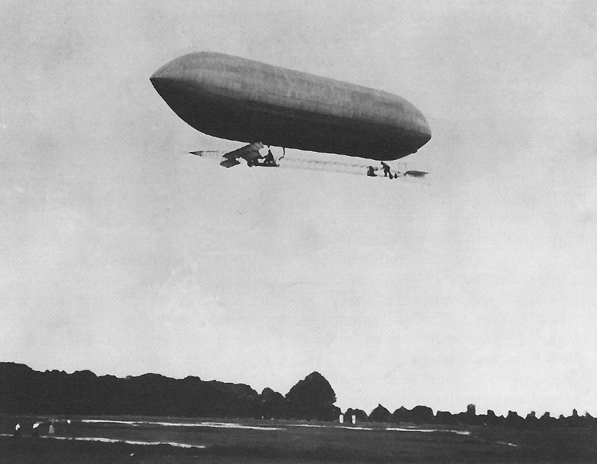

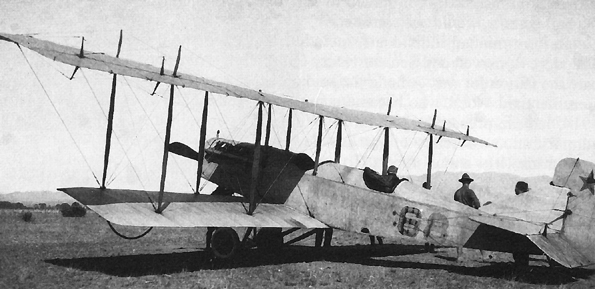

DIRIGIBLE AT FORT MYER, VIRGINIA, 1908

Major Squier headed an Aeronautical Board formed to supervise the trials, which began in August with the testing of the dirigible. Thomas S. Baldwin of Hammondsport, New York (he moved there after his airship factory was destroyed in the San Francisco earthquake), had submitted the winning bid, and his machine successfully met the Corps' requirements. The Army purchased his airship, which became known as Dirigible Number 1. The Corps used the dirigible at Fort Omaha until it became unserviceable, and in 1912 the Army sold the airship rather than invest in a new envelope.52

When the airplane trials began on 3 September 1908, crowds of curious spectators flocked to Fort Myer to witness the spectacle. Orville Wright conducted the tests, since Wilbur was then making flight demonstrations in Europe. The first flight lasted only one minute and eleven seconds, but on 9 September he remained aloft for one hour and two minutes. Earlier that day Lieutenant Lahm had accompanied Orville on a flight lasting over six minutes. Three days later Major Squier flew with Orville for over nine minutes. On 17 September Orville's passenger was 1st Lt. Thomas E. Selfridge, also a member of the Aeronautical Board. Selfridge had acquired considerable aeronautical experience, having until recently worked

[129]

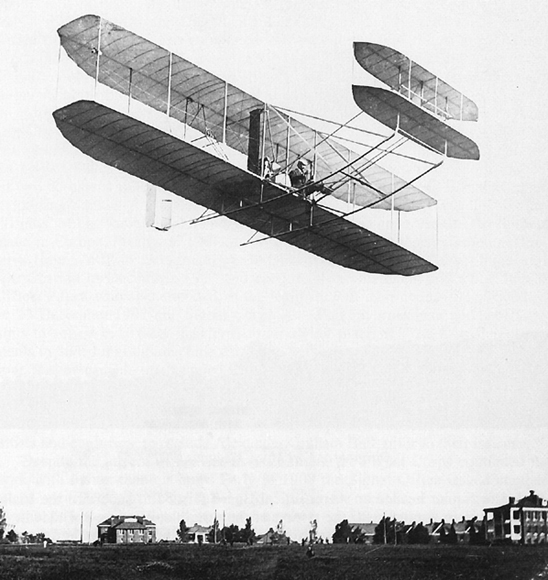

ORVILLE WRIGHT FLIES OVER FORT MYER, 1908

with Alexander Graham Bell, Glenn Curtiss, and others in a group known as the Aerial Experiment Association.53 On this day, however, disaster struck when a propeller blade cracked, causing the plane to crash. Selfridge died of his injuries, thus becoming the first American soldier killed in an airplane; Orville spent over six weeks recuperating in the Fort Myer hospital before returning home to Dayton.54 The Signal Corps postponed the airplane trials for nine months to allow the Wrights to try again. Despite the tragedy, Chief Signal Officer Allen remarked in his 1908 annual report, "The preliminary tests of the aeroplane at Fort Myer, Va., have publicly demonstrated, however, the practicability of mechanical flight."55

[130]

After rebuilding their plane and making some improvements, both of the Wright brothers returned to Fort Myer in June 1909 to resume the trials. Following a month of practice flights, the official tests began on 27 July with Orville once again at the controls. For the endurance test, Lieutenant Lahm accompanied Orville on a flight lasting 1 hour, 12 minutes, and 40 seconds, thereby exceeding the one hour called for in the specifications. For the speed test on 30 July, Orville and 1st Lt. Benjamin D. Foulois flew a ten-mile cross-country course between Fort Myer and Alexandria, Virginia. A captive balloon marked the halfway point at Shooter's (Shuter's) Hill in Alexandria, now the site of the George Washington Masonic National Memorial. A crowd of approximately seven thousand people, including President Taft, witnessed the historic flight. Completing the course at an average speed of 42.583 miles per hour, Orville again exceeded the contract requirements. With the successful conclusion of the trials, the Army purchased the Wrights' plane for $30,000.56

Their contract with the Army stipulated that the Wrights would teach two soldiers how to fly. Because of the limited open area at Fort Myer, the Signal Corps selected a more spacious location for the training in College Park, Maryland, about eight miles from Washington, D.C. Here, in the fall of 1909, Lieutenant Lahm and Lt. Frederic E. Humphreys became the Army's first pilots, with Wilbur Wright as their instructor. Lieutenant Foulois returned from an assignment in Europe in time to receive about three hours of instruction before operations shut down for the winter. (Not only was the fragile plane unable to withstand severe winter weather, especially strong winds, but no one had yet developed warm flight clothing for the pilots, who sat out in the open air.) Wilbur Wright, having fulfilled his contractual obligation, returned to Dayton. Lieutenants Lahm and Humphreys, only on temporary detail with the Signal Corps, went back to their regular units.57 Their departures left Foulois alone with a plane and no one to teach him how to fly it. In December he received orders to accompany the aircraft to Fort Sam Houston, Texas. As Foulois recalls in his memoirs, Chief Signal Officer Allen called him into his office and ordered him to "take plenty of spare parts, and teach yourself to fly." If the lieutenant had any questions, he could write to the Wright brothers for the answers. Thus, at Fort Sam Houston, Foulois took the first "correspondence course" in flying.58

For the next two years Foulois and the Wright plane constituted the Signal Corps' entire air force. As usual, Congress appropriated no funds to support aviation, despite General Allen's repeated requests. As one congressman reputedly remarked: "Why all this fuss about airplanes for the Army-I thought we already had one."59 Consequently, Foulois footed much of the airplane's maintenance costs out of his own pocket. Despite his straitened circumstances, the novice aviator accomplished a great deal. Most important, he succeeded in learning to fly and lived to tell about it. But his education proved to be a difficult and dangerous one, punctuated by a number of crash landings. On one such occasion, after nearly being thrown from the plane, Foulois installed the first aircraft seat belt.

[131]

While in Texas, Foulois' one-man air force received its first field experience early in 1911 in conjunction with Army maneuvers held along the Mexican border. In the process, he gave many soldiers their first glimpse of an airplane in flight. Foulois performed aerial reconnaissance and used a radio to make his report. With this device he could communicate in Morse code with Signal Corps stations on the ground. After February 1911, Foulois did not fly the Army's plane but rather a Wright machine owned by Robert E Collier, magazine publisher and member of the Aero Club of America. Collier loaned his airplane to the Army pending the appropriation of funds to obtain new equipment. Subsequently, the Army sent its first and only aircraft to Dayton for restoration and eventual display in the Smithsonian.60

While Foulois participated in the maneuvers along the border, Congress, faced with the threat of hostilities in Mexico, finally included $125,000 for aviation in the budget for fiscal year 1912. The lawmakers made $25,000 of the sum immediately available, and the Signal Corps used the money to purchase five new planes: three designed by the Wrights (Type B) and two manufactured by their rival, Glenn Curtiss, with whom the Wright brothers were entangled in a bitter patent suit. With new planes and pilots ordered to Fort Sam Houston, a provisional "aero company" was organized there in April 1911. The operations of this unit ceased, however, following the death of one of the pilots, Lt. G. E. M. Kelly, in a crash on 10 May.61

In June 1911 the Signal Corps officially opened a flying school at College Park, Maryland.62 Foulois did not number among the pilots reporting there, having been reassigned to a tour of duty with the Militia Bureau. Two of the new pilots at College Park, 2d Lts. Henry H. ("Hap") Arnold and Thomas DeW Milling, had previously received training at the Wright Company in Dayton.63 Training on a Wright machine, however, did not prepare a pilot to fly a Curtiss plane, and vice versa. While the Wrights controlled their planes by means of the wing-warping method, on which they had received a patent in 1906, Curtiss used movable ailerons between rigid wings.64 In these early years pilots usually knew how to fly either one type of plane or the other. Filling out the roster at College Park, an enlisted detail performed maintenance and guard duty. In addition to taking flying lessons that summer, the pilots experimented with a bombsight.

With the onset of cold weather, aviation operations again moved south. This time the Corps selected Augusta, Georgia, known for its mild winter climate, as its destination. As luck would have it, the winter of 1911-1912 proved to be an exception, with heavy snows falling in Georgia during both January and February. In the spring the melting snow plus excessive rainfall caused flooding. Fortunately, the soldiers had placed the planes on platforms, and they were not damaged. Between the bouts of bad weather the pilots managed to fit in some practice. They also received a visit in January from Wilbur Wright, no doubt a source of much valuable advice. The aviation world lost this pioneer when he died of typhoid fever at age forty-five the following May.65

[132]

Flying resumed at College Park in April 1912. The next month several new planes arrived. These more powerful "scout" planes (Wright Type C) had been designed to perform reconnaissance and could carry radio and photographic equipment in addition to two men.66 Experimental activities conducted at College Park during this year included night flying, aerial photography, use of the radio, and the testing of the Lewis machine gun from the air.67 Despite this experiment and the earlier one with the bombsight, few military experts recognized the offensive value of airplanes. Indeed, the rather flimsy machines themselves gave little indication of their potential for combat.

Yet Army fliers continued to gain experience and knowledge. During the summer of 1912 several pilots from College Park made reconnaissance flights in conjunction with maneuvers held in Connecticut. Later that fall Arnold and others went to Fort Riley, Kansas, to perform aerial observation of field artillery. By 1 November 1912 the number of personnel at the school had grown to twelve officers and thirty-nine men.68 When operations at College Park ended for the winter, the Curtiss pilots went to San Diego, California, where Curtiss operated a school and experimental station. On 8 December 1912 the Signal Corps established its own flying school on North Island in San Diego Bay.69 Meanwhile, the Wright pilots returned to Augusta. During the winter training there the Wright Company delivered its new "speed scout' 'plane (Type D), which carried only the pilot and could travel over sixty-six miles per hour. The Signal Corps intended to use this type of plane for strategic reconnaissance and the rapid delivery of messages.70

Aviation was an especially hazardous undertaking for the aerial pioneers, and many brave men lost their lives. To provide professional recognition and incentive for pilots, the War Department established the rank of military aviator in 1912. To achieve this rating a pilot had to be able, for example, to attain an altitude of at least 2,500 feet; to fly in a wind of at least 15 miles per hour for 5 minutes; and to make a reconnaissance flight of at least 20 miles cross-country at an average altitude of 1,500 feet. These requirements exceeded those previously prescribed by the Aero Club of America and reflected the introduction of more powerful planes. Qualified fliers wore the newly authorized military aviator's badge.71 The following year Congress acknowledged the risks taken by pilots when it authorized flight pay for those assigned to full-time aviation duty. The bonus amounted to a 35 percent increase in salary, but Congress limited to thirty the number of men who could receive the extra payment.72

After seven years at the head of the Signal Corps, General Allen relinquished his position on 13 February 1913, having reached the mandatory retirement age of sixty-four. Less than a month later, on 5 March, Brig. Gen. George P Scriven became the Army's seventh chief signal officer.73 A member of the West Point class of 1878, Scriven had over twenty years of experience with the Corps. While not an aviator when he became chief, he soon began taking lessons in order to better understand the problems the pilots faced.74 His views on aviation would set the Signal Corps' policy in the crucial years leading up to World War I.

[133]

GENERAL SCRIVEN

Increased interest in aviation soon obliged the Signal Corps to defend its dominion over the Army's air force. Early in his tenure Scriven testified before the House Committee on Military Affairs concerning proposed legislation to create a separate Aviation Corps. In his report Scriven argued against the idea.

It is no time now to make experimental changes,

whatever the future may develop in regard to the organization of a

separate corps. This may come, and may really be the fourth arm of

the service; but now we are crossing the stream, and it is not time

to swap horses or to make changes which will certainly cost the advance

of military aviation many years of delay.75 |

Several Army aviators, including Foulois and Arnold, agreed with Scriven and testified against the proposal.76 The committee also heard another voice defending the status quo, that of Capt. William Mitchell, then serving a tour on the General Staff and not yet an Army aviator. Mitchell stated that in his opinion aviation's role was that of reconnaissance and, for that reason, part of the Signal Corps' communications mission.77 The arguments of Scriven and the other opponents convinced the committee to reject the bill as written. While aviation remained something of a stepchild, the hearings did focus attention on its potential importance to the Army. Meanwhile, statistics compiled for the hearings clearly showed the lowly status then held by Army aviation: The United States ranked fourteenth out of twenty-six nations in the amount of its expenditures for aviation over the past five years. Germany ranked first.78

While congressmen debated their future, the Signal Corps' pilots were being put to work. Trouble flared again with Mexico in February 1913, and President Taft ordered the War Department to mobilize the 2d Division along the border. The Army aviators at Augusta were called to service, and at Texas City, Texas, the Signal Corps' aviation assets were organized to form the 1st Aero Squadron (Provisional) to support the division. Captain Chandler served as the squadron's first commander. During this period Lieutenant Milling made a cross-country flight from Texas City to San Antonio and back, totaling 480 miles, that set American distance and endurance records. Milling's observer, Lt. William C. Sherman, demonstrated the airplane's value for reconnaissance by making a detailed sketch map of the ground covered during the flight. (When finished, the map measured eighteen feet in length!)

[134]

By mid-June it had become apparent that no hostilities would ensue. Most of the squadron then left Texas for San Diego, where the Signal Corps had opened a new flying school. The California location possessed one significant advantage over Maryland: The climate permitted year-round training. On 13 December 1913 the school at San Diego officially became the Signal Corps Aviation School, and the Army did not renew its lease on the land at College Park.79

Meanwhile, serious problems with both planes and pilot training were coming to light. In 1913 alone seven officers had died, bringing the total number of aviation fatalities since 1908 to eleven officers and one enlisted man. Half of the deaths had occurred in the Wright Model C. All six of the Model Cs purchased by the Army had crashed, and Lieutenant Lahm could count himself among the lucky few to have survived. While operating a Wright C at Fort Riley in 1912, Lieutenant Arnold had come so close to death that he swore to give up flying forever.80 The Wright planes in general had a tendency to nose dive: When they crashed, the engine often tore loose and fell upon the pilot or passenger. With its extra power, the Model C proved more hazardous than its predecessors.

The rapidly rising death toll among Army aviators led to an investigation into the situation. In its report, the board of inquiry condemned the Wright C as "dynamically unsuited for flying."81 But the problems did not lie solely with the planes. The school at North Island received a very unfavorable report early in 1914 from the Inspector General's Department.82 Consequently, the Signal Corps hired Grover Loening, a former employee of the Wright Company, as the Army's first aeronautical engineer to oversee operations at San Diego. Furthermore, and most important, the Signal Corps outlawed the use of all pusher planes (that is, those with the engine and propellers behind the pilot), whether manufactured by the Wright Company or by Curtiss. The switch to tractor planes, in which the engine and propellers are in front of the wings and the pilot, did not meet with the approval of Loening's former employer: For several years Orville Wright refused to begin to manufacture this type of aircraft. The conversion to tractors did, however, cause an immediate drop in the number of fatalities. Only one pilot died in the next six months, and this mishap occurred when his plane was blown out to sea in a storm.83

Having concentrated its aeronautical pursuits on the airplane, the Signal Corps no longer needed a balloon plant. Thus, in October 1913, the Corps abandoned its post at Fort Omaha, and the Army transferred the balloon facilities to the Agriculture Department for use by the Weather Bureau in the making of balloon explorations of the upper atmosphere. Meanwhile, the Corps moved the signal companies stationed at Omaha to Leavenworth.84

On 4 December 1913 the War Department finally issued general orders that outlined the provisional organization for a Signal Corps aero squadron, although such a unit had participated in the maneuvers on the border earlier that year. The squadron would consist of twenty officers and ninety enlisted men organized into two aero companies, each with four airplanes and eight aviators. The unit would also have its own ground transportation in the form of sixteen tractors and six motorcycles.85

[135]

The Signal Corps had gotten the Army off the ground, but it had not yet really soared. After more than six years of existence, the Aeronautical Division remained small and underfunded. By the end of 1913 the Corps had received less than a half million dollars in total appropriations for aviation and had only twenty officers on duty at the San Diego flight school.86 On the positive side, fifty-two officers had been detailed to aeronautical duty since 1907; the Army had purchased twenty-four planes since 1909 (fifteen of which remained in operation); and the Signal Corps had established an aviation school.87 Despite its initial lead in military aviation and subsequent accomplishments, the United States had fallen far behind the flourishing aerial operations of the major European powers.

Next to aviation, radio was considered to be the wonder of the age during the early twentieth century. Initially known as wireless telegraphy, it freed long distance communication from the constraints of wires. Wireless telegraphy meant exactly that Morse code transmitted by electromagnetic waves instead of wires. The discharge of a spark across a gap caused by the pressing of a telegraph key generated the electromagnetic waves that relayed the message. The years 1900 to 1915 constituted "the golden age of the spark transmitter," with the names of Guglielmo Marconi, Reginald Fessenden, and Lee de Forest the most prominent in the early development of radio.

Spark-gap technology possessed several important drawbacks. From a security standpoint, a spark transmission could not be tuned; it covered a span of frequencies and could be intercepted by anyone with a receiver. Moreover, the signals of all stations within range of each other caused mutual interference. Not only did the noisy spark create a great deal of distortion, the consequent dissipation of energy over the broad band of frequencies lessened the distance over which the signals could travel. Only with advances in continuous wave technology would wireless telegraphy evolve into wireless telephony, or radio broadcasting.88

Within the military the Navy, rather than the Army, took the lead in radio development. Wireless telegraphy provided a heretofore unavailable means of communication with and between ships at sea. The Navy installed the first ship board radios in 1903, and by the following year it had established twenty shore stations and had plans for immediate expansion. Meanwhile, the Army, the Weather Bureau, commercial firms, and private individuals competed with the Navy for the airwaves. Concerns expressed by the Navy about the need for regulation led President Roosevelt in 1904 to appoint a board to study radio activities. The use of wireless by the combatants during the Russo-Japanese War provided the president with an additional incentive to take action.

Chief Signal Officer Greely served as a member of the Inter-Departmental Board on Wireless Telegraphy, generally known as the Roosevelt Board, along

[136]

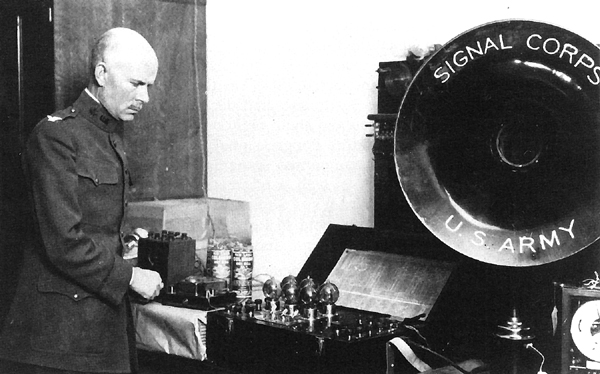

COLONEL SQUIER INSPECTS RADIO EQUIPMENT IN THE LABORATORY

with representatives of the Navy, the Agriculture Department, and the Commerce and Labor Department. The board's report, which received the president's approval, established the government's first radio policy. The board recognized the Navy's priority in radio matters, while allowing the Army to operate stations as necessary, provided that they did not interfere with those of the Navy. It additionally recommended that the Weather Bureau turn over its stations to the Navy and urged Congress to enact regulatory legislation. Nevertheless, Congress waited until 1912 to act, after the Titanic disaster had tragically demonstrated the need for control over wireless activities. It then passed a law requiring the licensing of private stations and operators by the secretary of commerce and labor and dividing the electromagnetic spectrum between its public and private users.89

Still, the lack of international radio regulations created problems, among them the Marconi company's attempt to establish a radio monopoly. Marconi initially leased rather than sold his equipment to his clients and supplied the operators as well. He further stipulated that there must be no intercommunication between Marconi sets and those of other manufacturers, except in emergencies. By this means he hoped to force all those wanting wireless service to use Marconi equipment. At the invitation of the German government, representatives of eight nations, including Chief Signal Officer Greely, gathered at the first international conference on wireless telegraphy, held in Berlin during August 1903. The meeting produced a protocol that remains the cornerstone of international radio agreements. Its provisions contained a statement upholding the poli-

[137]

cy of intercommunication, thus striking a blow to the Marconi interests.90 A second conference convened in Berlin in October 1906, with Chief Signal Officer Allen in attendance. The resulting treaty embodied the intercommunication principle of the 1903 protocol and received the endorsement of President Roosevelt. The conference also adopted the signal "SOS" as the international distress call because these letters could be easily sent and deciphered. General Allen and other government officials concerned about radio policy jointly submitted arguments in favor of the treaty before congressional hearings. Due to strenuous opposition by various radio companies, especially the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company of America, as well as of amateur operators, the Senate did not ratify this treaty until 1912.91 Majors Squier, Russel, and Saltzman attended the third international conference, held in London in 1912 to revise the 1906 treaty. Convening shortly after the Titanic disaster, the conference devoted much of its attention to safety at sea.92

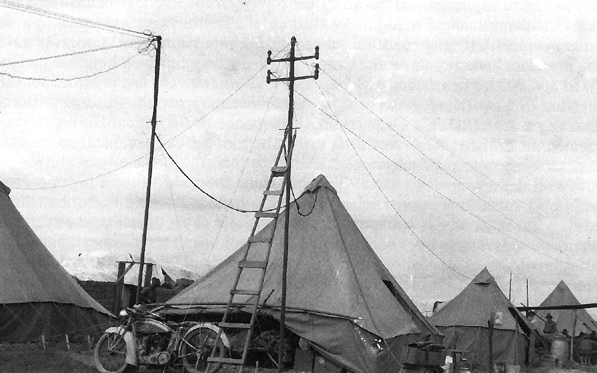

While the legal questions were being settled, research to improve radio continued. The Signal Corps worked on the development of both fixed and portable wireless equipment. As already noted, the Corps took its first field sets to Cuba in 1906. During 1907 and 1908 the Corps introduced pack and wagon sets to the Philippines. A pack set had a range of about twenty-five miles, while a wagon set could operate at a range upwards of two hundred miles.93 Finding commercial sets unsuitable for field conditions, the Corps constructed its own equipment in its laboratory. Once a standard model had been developed, the Corps sought a commercial manufacturer. By mid-1908 forty-five sets had been assembled and sent to the field. Also during that year, the Corps installed a wireless connection in the Philippines between the islands of Zamboanga and Jolo. These stations communicated over a distance similar to that across Norton Sound in Alaska and, as in that case, wireless replaced a cable that had been destroyed by the elements-this time a coral reef. The year 1908, a particularly busy one for the Corps in radio matters, witnessed the completion of a wireless system connecting the principal posts protecting New York Harbor. The Corps subsequently installed wireless equipment at other important coastal fortifications both within the United States and in the Philippines and Hawaii. For training purposes, the Corps also established a permanent station at Fort Omaha in 1908 and sent portable sets to Forts Leavenworth and Riley, subsequently replacing them with permanent stations. The Corps also conducted wireless training for enlisted men at Fort Wood.

In the far northwest, radio began to supplement wire within the Alaska communication system. By 1908 the Signal Corps was operating a series of wireless stations along the Yukon River. The stations cost much less to maintain than wire in the rugged climate that often wreaked havoc with the lines. But radio had not yet become reliable enough to replace wire completely. Under the guidelines established by the Roosevelt Board, the Navy operated the radio stations that connected Alaska with the continental United States. In addition to its stations on land, the Signal Corps supplied wireless sets for Army transports, cable ships, harbor tugs, and mine planters.94

[138]

In the air, the Signal Corps combined its two incipient technologies by installing wireless equipment in airplanes. In 1911 a message was successfully transmitted from an Army airplane over a distance of two miles; a year later the distance had increased to fifty miles. Improvement came steadily. By 1916 a pilot at the San Diego school was sending signals and messages from an airplane over 140 miles distant, and plane-to-plane communication was achieved for the first time.95

Aware of the deficiencies inherent in wireless telegraphy, the Corps turned its attention to the development of wireless telephony. Based on Allen's request for funds, the Army appropriation act of 1909 included $30,000 for the purchase and development of wireless telephone equipment.96 In order to conduct experiments, the Corps made arrangements for laboratory space at the recently created National Bureau of Standards in Washington, D.C., and Allen placed Major Squier in charge of the research effort there. Just down the hall, the Navy had undertaken its own radio research a year earlier. The bureau subsequently tried to concentrate all governmental radio research under its auspices, and Congress voted $50,000 for a radio laboratory there in 1916.97

While at the bureau, Squier conducted experiments with the transmission of radio waves along wires, which he called "wired wireless." By this method radio signals could be multiplexed-that is, many messages could be sent simultaneously along the same wire. He also found that voice signals could be sent by radio along telephone lines. These radio communications could, moreover, travel along the wires without interference with the regular telephone traffic. The "wired wireless" method of transmission provided greater secrecy than broad band radio and made more efficient usage of existing wires. In September 1910 Squier demonstrated his multiplex telephony system for General Allen over a line between the Bureau of Standards and the Signal Corps' lab at 1710 Pennsylvania Avenue. Pleased with the results, Allen initiated proceedings to secure a patent on the invention. Successful application of the technique, however, awaited the development of improved components, especially electronic tubes.98

Squier's reassignment as military attaché to London in March 1912 cut short his further experimentation in this area, but it did not curtail his research activities, for he had apparently received the assignment because of his scientific back ground. With his technical expertise, Squier could observe and report on the latest European developments.99

A former member of the Signal Corps, H. H. C. Dunwoody, made a significant contribution to radio technology in 1906 when he discovered that the carborundum crystal (carbon plus silicon) could detect wireless signals. Dunwoody had retired from the Army in 1904 after more than forty years' service and promotion to the rank of brigadier general. His last assignment had been as commander of Fort Myer. The carborundum detector, on which he received a patent, provided an inexpensive and effective receiver of spark transmissions. Because carborundum could also receive voice transmissions, it became a key component in the development of radio telephony. Dunwoody, meanwhile, became a vice president of de Forest's radio company.100

[139]

About the same time, de Forest invented the audion, a three-element vacuum tube that made radio broadcasting possible. Although de Forest was among the first to envision broadcasting's potential for providing entertainment and information, he did not immediately grasp the significance of his creation. De Forest initially used the audion as a receiver in conjunction with spark transmitters, but his attempts to broadcast operatic performances and lectures met with only minimal success. Several years later a student at Columbia University, Edwin H. Armstrong, made the necessary engineering breakthrough. Recognizing that the audion could both amplify and transmit continuous radio waves capable of carrying voice and music, Armstrong devised the feedback circuit-a discovery that provided the foundation for the subsequent development of radio technology.101

Meanwhile, in 1913 the Navy opened its first high-powered radio station at Arlington, Virginia. Using equipment designed by Reginald Fessenden that took spark technology to its limits, the station could transmit signals up to one thou sand miles. Arlington served as the first link in a chain of worldwide high-powered stations that connected the Navy Department with its major bases and units of the fleet wherever they might be.102

Despite the Navy's leading role in radio development, many naval officers had resisted radio's adoption, especially on shipboard. Historically, the commander, once leaving shore, had total operational control because his superior officers on land had no means of communicating with him. Radio destroyed this autonomy. Older officers, accustomed to flag signaling, also resisted the change. It thus took considerable time and effort to integrate radio into fleet operations.103

The Army, on the other hand, with its combined arms philosophy, depended upon the ability to communicate between its various commands. Radio accomplished this more easily than messengers, flags, or even the telegraph. While field commanders lost some autonomy once the commander in chief could communicate directly with the battlefield (as Lincoln's intervention via telegraph during the Civil War had demonstrated), on balance the Army had more to gain than lose from the introduction of radio. The centralization of command and control, fostered on an administrative level by the Root reforms, found technological support in the radio.

Organization, Training, and Operations, 1908-1914

Aside from its involvement with aviation and radio, the basic duties of the Signal Corps remained relatively unchanged between 1908 and 1914, which is not to say that they lacked importance. The branch continued to operate the Alaska communication system; to provide fire control, fire direction, and target range communications; and to establish post telephone systems. Due to advances in telephone technology, the Corps labored to upgrade the systems it had previously installed. By 1911 most post telephones operated by common battery rather than the hand-cranked magneto method, and underground lines replaced aerial wires at many posts. The Corps also operated a 100-mile telephone system in Yellowstone

[140]

National Park, which it turned over to the Interior Department in 1914.104 The opening of the Panama Canal that year, however, gave the Army a new strategic point to defend and a critical site for Signal Corps communications to be installed.

As for the military telegraph lines, once a major function of the Corps, that system had been reduced to "almost nothing."105 By 1913 but one line remained: between Fort Apache and Holbrook, Arizona, about ninety miles in length. The Corps continued to maintain some additional lines that connected military posts with commercial companies, but between 1913 and 1914 the number of such stations dropped from sixty to twenty-four. To release signal personnel for other duties, civilian operators worked at fourteen of these stations. At most posts telegraphic messages could now be received by telephone from commercial stations.

As had been true for most of its nearly fifty years of existence, the Signal Corps suffered from a chronic shortage of personnel. Like his predecessors, Chief Signal Officer Allen requested that Congress increase the Corps' size, but his pleas went unanswered, and the branch's authorized strength remained at 46 officers and 1,212 enlisted men. As Allen stated in his 1908 annual report, "until Congress takes some action to increase the number of officers and men of the Signal Corps, the mobile Army of the United States must remain vitally weak in a service where it should be strongest."106

While the Corps' authorized strength remained static, some changes did occur in the organization of its personnel. On 11 March 1910 the War Department reduced the size of the field signal company to three officers and seventy-five men, more closely approximating what the Corps could actually support. General orders issued on 5 April officially redesignated Companies A, D, E, I, and L (newly organized in 1909) as field signal companies.107 Company L served at Fort McKinley in the Philippines, while the others occupied stations within the continental United States until 1913, when Company E moved to Hawaii. In 1911 the War Department increased the strength of the field companies to four officers and ninety-six enlisted men. The company was divided into six sections: four to provide wire communications and two equipped with field radio pack sets.108

The 1910 edition of the Field Service Regulations significantly increased the number of signalmen allotted to a division. They provided each division (either of infantry or cavalry) with a field battalion consisting of two field companies. But because the Signal Corps had only enough resources to organize five field companies, it did not form these battalions. The regulations also called for an "aerowireless battalion" for each field army (equivalent to a corps) to consist of a wireless and an aero company. But again, as the Corps then possessed only one plane and one pilot, these units represented what the Army hoped to organize upon mobilization, rather than what it expected to field in peacetime.109

Telegraph companies, also envisioned by the chief signal officer in 1907, received official sanction via general orders issued by the War Department in 1913.110 Somewhat larger in size than a field company, with 4 officers and 139 enlisted men, each telegraph company was to be supplied with enough wire to

[141]

run approximately 125 miles of line and to establish 60 telephone and 10 telegraph stations. Each company comprised 6 sections, 3 for telephone work and 3 for telegraph operations. Not only did the Signal Corps lack the men to fill these organizations, it also lacked the horses and mules needed to transport the men and equipment.111

In 1914 the Army published its first Tables of Organization and Equipment (TOES) based on the Field Service Regulations issued that year. Henceforth, changes in unit organization appeared in this form rather than in War Department general orders. The tables outlined the structure of both a peacetime and a wartime army. For the Signal Corps, a radio company was to be paired with a wire company to form a field signal battalion in an infantry division during wartime. In a wartime cavalry division, a headquarters company replaced the wire company found in an infantry division. The headquarters company had, however, both a radio platoon and a wire platoon. In peacetime, a single field company contained the cadres of signalmen from which the wartime battalions would be formed. The separation of the wire units from the radio units in the 1914 TOES reflected the increasingly specialized nature of signal communications. The tables further provided for a telegraph battalion comprising two telegraph companies. These companies carried heavy-duty line intended for tactical use rather than the lighter and more portable variety used by the wire sections of the field companies. As for the Corps' aerial function, the tables assigned an aero squadron to each division in wartime.112

With no increases forthcoming from Congress, the War Department looked for other solutions to the Signal Corps' perennial personnel predicament. In 1913 Secretary of War Lindley M. Garrison requested that the Post Office Department take over the Washington-Alaska Military Cable and Telegraph System, thereby releasing 5 officers and 200 men for other work. Garrison argued that the system's commercial business overshadowed its military usage, thus making it a public utility.113 Pending a transfer and to satisfy immediate requirements, the Signal Corps withdrew 20 percent of the enlisted men from Alaskan service and placed them with field units. Ultimately, however, the Post Office turned down the secretary's proposal.114

Other initiatives proved more successful. The National Guard, as a result of the reforms initiated by the Dick Act of 1903, constituted an important manpower pool for the Signal Corps. Although the 1903 legislation had allowed the states and territories five years for their units to reach conformity in organization, equipment, and training with those of the Regular Army, full compliance had not been reached by 1908. In May of that year Congress extended the time period to 21 January 1910.115 Chief Signal Officer Allen used this legislation to encourage the formation of signal units within the National Guard as nearly half the states and territories still lacked organized signal troops. Due to the small size of the Regular Army's Signal Corps, the War Department needed the signal units of the National Guard in wartime to supplement the full-time force. Allen wanted the states to organize their units into field companies so that they could train as such

[142]

in peacetime and thus be prepared for service in the event of mobilization. Moreover, the participation of Regular Army signal units in summer maneuvers with the National Guard provided important practical training.116

Despite the introduction of radio, visual signals still played a role in military signaling, and the Signal Corps continued to distribute visual signaling kits as provided for in Army regulations. The expansion in the types of signaling had consequently led to a proliferation of codes in use. In 1908 the Signal School had conducted tests which concluded that Morse code could easily be adapted for signaling with wigwag flags. The chief signal officer in his 1909 annual report cited "a growing aversion" on the part of officers and enlisted men to the use of the Myer code in visual signaling.117 As it stood, they had to learn three codes: the Myer, the American Morse for ordinary telegraphy, and the Continental or International Morse for wireless and cable service. Finally, in 1912, the Army adopted the International Morse code as its general service code; the American Morse code would continue to be used on telegraph lines, field lines, and short cables. Thus, the Army abandoned the Myer code, which had been employed, although not continuously, since 1860.118 Furthermore, in 1914 the Army adopted two-arm semaphore signaling for general use. (The Field Artillery had adopted it somewhat earlier.) Semaphore signaling was faster and simpler than wigwag and had been employed by the Navy for some time. The Army continued to use wigwag for long-distance communication, for which it was better suited than semaphore, thus retaining some of Myer's original contributions to military signaling. The Signal Corps, meanwhile, acquired responsibility for distributing the semaphore equipment.119

The Army Signal School at Fort Leavenworth continued to train Signal Corps officers for their increasingly complex duties. In its electrical laboratory, students conducted research and sought to make improvements to field equipment. As commandant, Major Squier had instituted semimonthly technical conferences that provided the faculty and students with a forum for the presentation of papers and the exchange of ideas. The school published the best papers on an occasional basis and distributed them to Signal Corps officers, both of the Regular Army and of the National Guard. These papers served as a precursor to a professional journal.120 With the closing of the Signal Corps post at Fort Omaha in 1913, its school for enlisted instruction moved to Leavenworth along with the two signal companies stationed there.

But the relatively quiet years since the conclusion of the War with Spain were coming to an end. In 1910 revolt broke out in Mexico against the regime of Porfirio Diaz, who had ruled that country for over thirty years. Recurrent incidents led President Taft in March 1911 to order 30,000 troops to the border to conduct maneuvers and enforce neutrality. The bulk of these units were assembled from posts around the nation to form the Maneuver Division, which made its headquarters near San Antonio. (The Army then had no regular TOE divisions.) Meanwhile, Company A, Signal Corps, had traveled in February from Fort Leavenworth to Eagle Pass, Texas, presumably to lay down communication lines

[143]

in anticipation of the division's deployment. The divisional troops included Field Companies D and I, Signal Corps.121 The role of Signal Corps aviation has already been discussed. Maj. George O. Squier served as the division's chief signal officer, while a young infantry officer, 1st Lt. George C. Marshall, Jr., acted as his assistant. Although the communication systems provided by the Signal Corps worked well, the maneuvers proved less than a complete success. After ninety days the division still had not been fully organized.122 When Diaz resigned in May 1911 and the revolutionary leader Francisco Madero assumed power, peace had seemingly been restored to the troubled country. The War Department discontinued the Maneuver Division in August, but some troops remained in Texas, including Company I, Signal Corps, which stayed until November 1911.123

The overthrow and assassination of Madero by General Victoriano Huerta in February 1913 launched a protracted and bloody civil war within Mexico that necessitated further American troop concentrations along the border. Just before leaving office, President Taft requested that troops be sent to supplement the border patrols. Consequently, on 21 February, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson ordered the 2d Division, one of the Army's newly organized tactical divisions, to assemble at Galveston and Texas City.124 When the new president, Woodrow Wilson, refused to recognize the Huerta regime, he set the stage for possible confrontation. During this mobilization Field Company D, Signal Corps, once again served as a divisional asset.125 Meanwhile, Field Company I, scattered at several stations along the border and with its headquarters at Fort Bliss, provided communication with units in the field by means of radio, buzzer, and even the heliograph.126 Companies B and H, reorganized as telegraph companies, also served in Texas. The Signal Corps strung 130 miles of telegraph wire along the border which, in conjunction with commercial lines, made communication possible along most of the border's length.127 In addition, the Corps' aero squadron provided aerial support.

In April 1914 an international incident erupted at Vera Cruz, Mexico's principal port. The crisis began when Huertista soldiers arrested an officer and several crew members of an American warship at Tampico. Although the Mexicans soon released the prisoners, President Wilson demanded an apology, which the Mexican government refused to give. About the same time, a German ship arrived at Vera Cruz with a cargo of arms and ammunition for Huerta. President Wilson ordered American naval forces at Vera Cruz to prevent the ship from unloading. Later that day, 21 April, marines went ashore and seized the customs house. By the following day, despite Mexican resistance, the Americans controlled the city. Elements of the 2d Division thereupon embarked for Vera Cruz for occupation duty. Field Signal Company D, part of this contingent, arrived on 3 May to establish buzzer lines from the headquarters of the expeditionary force to six points in the city. It also installed radio connections between Army headquarters and a refugee train and maintained communication with the Navy. This campaign probably also marked the last field use of the heliograph by the United States Army.128

[144]

Brig. Gen. Frederick Funston served as military governor of Vera Cruz for the seven months of its occupation. At first war with Mexico seemed imminent. But Huerta, failing to rally sufficient support to oust the Americans, ultimately resigned and fled to Europe. Nevertheless, the troubles had only subsided temporarily. The subsequent recognition of the new government of Venustiano Carranza by the Wilson administration in October 1915 and Carranza's break with Francisco "Pancho" Villa set off the chain of events that led the United States to intervene in Mexico once again in 1916.129

The Signal Corps Spreads Its Wings

On 18 July 1914 Congress passed legislation creating the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps, to consist of up to 60 officers and 260 enlisted men. These men would serve in addition to the Corps' existing authorized strength. For the first time, the Army had soldiers permanently assigned to aviation duties. The act limited aviation officers, however, to unmarried lieutenants no older than thirty. The section's responsibilities included:

operating or supervising the operation of all military

air craft, including balloons and aeroplanes, all appliances pertaining

to said craft, and signaling apparatus of any kind when installed

on said craft; also with the duty of training officers and enlisted

men in matters pertaining to military aviation.130 |

Lt. Col. Samuel Reber headed the new section. The Aeronautical Division, meanwhile, continued in existence as the Washington office of the section. As for budget matters, Congress had specified in previous legislation that up to one-half of the Signal Corps' appropriation of $500,000 could be spent on aviation-related items.131

The retention of aviation within the Signal Corps indicated that Congress held the prevailing opinion that aviation served a support, rather than a combat, function. The Field Service Regulations of 1914 reinforced this view by assigning to aviation a passive reconnaissance mission. Its only direct combat role concerned the use of aircraft to prevent aerial observation by the enemy.132 As Chief Signal Officer Scriven wrote in his 1914 annual report, "much doubt remains" regarding the offensive value of aviation and "little of importance has been proved" as to the capabilities of planes in the dropping of bombs. "In reality," he stated, "little is known of this power of air craft, though much is guessed and more feared."133 He went on to remark that

if the future shows that attack from the sky is

effective and terrible, as may prove to be the case, it is evident

that, like the rain, it must fall upon the just and upon the unjust,

and it may be supposed will therefore become taboo to all civilized

people; and forbidden at least by paper agreements.134 |

Although Scriven, like most of his contemporaries, could not imagine the havoc that would be wreaked by aerial bombardment during World War II, he did have an insight into its deadly possibilities.

[145]

COLONEL REBER