CHAPTER VII

World War II: Establishing the Circuits of Victory

The shock of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor galvanized the American people into action. When Congress declared war on the Axis powers in December 1941, a truly global conflict began, with fighting on four of the seven continents and across the seas. By that time the Signal Corps had already undergone a great expansion. Yet its strength of 3,000 officers and 47,000 men represented but a fraction of the manpower needed to support a total war.1

The Search for Manpower and Brainpower

On 7 December 1941 Chief Signal Officer Dawson Olmstead had been conducting an inspection of radar sites in Panama. Upon learning of the attack, he hurriedly returned to Washington to oversee the Corps' wartime operations. He faced an extraordinary challenge. The 1941 Troop Basis, the formal War Department authorization for units, envisioned the activation of four field armies and allowed the Signal Corps 1 signal service regiment, 5 air warning regiments, 19 battalions, 32 division signal companies, 2 troops (1 for each cavalry division), 29 platoons, and a variety of specialized companies to meet the needs of radio intelligence, operations, photographic duties, repair, depot storage, construction, and so forth.2

Now faced with the problem of finding men to fill these units, the Signal Corps, as in World War I, endeavored to tap the large pool of trained civilian communicators. It did so through a program known as the Affiliated Plan, established in 1940, which enabled the Corps to draw personnel from civilian groups which varied widely, from the telephone and motion picture industries to groups of pigeon fanciers. Rather than organizing an entire unit from the personnel of a particular company, such as the Bell battalions during World War I, the Affiliated Plan used smaller groups of civilian specialists as cadres around which units were created. The Affiliated Plan allowed the Signal Corps to form the nuclei of 404 units. Ironically, radio experts were not among the new recruits, because the Army Amateur Radio System, organized to supplement the Signal Corps during peacetime emergencies such as floods and tornadoes, had no provision for supplying personnel to the Corps in wartime. As a result, many experienced communicators were lost to other branches.3

[255]

Training men to operate the Signal Corps' increasingly sophisticated equipment presented another challenge. The Corps needed individuals of high aptitude and intelligence for its technical training, but had difficulty securing them. Proficiency in some specialties, such as automatic equipment installation, came only after many months of instruction.4 The electronics industry could supply skilled personnel, but at the same time the Corps needed to keep those men at their jobs producing communications equipment.5

One solution was to seek high-quality recruits. During World War II the Army evaluated its inductees according to the Army General Classification Test (AGCT), which measured both intelligence and aptitude. A score of 100 represented the expected median. Based on the results, the men were divided into five classes, from highest to lowest. Although all arms and services were supposed to receive the same proportion of men from each category, those with needs for high technical proficiency were quick to put in claims for high scorers. The Signal Corps fared well, with 39 percent of the men assigned to its training centers from March to August 1942 coming from Classes I and II; by 1943, 58 percent of its inductees came from these classes.6

Even before the war the Signal Corps had opened an enlisted replacement training center at Fort Monmouth in January 1941. The center provided recruits with basic training, after which they enrolled in courses at the center or received advanced specialist training at the Signal School. By December 1941 it had already turned out 13,000 enlisted specialists.7

Once war began the Signal Corps quickly outgrew the existing facilities at Monmouth, and Chief Signal Officer Olmstead made arrangements to expand operations to other locations in the vicinity. Consequently, in January 1942 the Signal Corps leased the New Jersey State National Guard Encampment at Sea Girt, a few miles from Monmouth, which became known as Camp Edison. In July 1942 the Corps also established a new post at Eatontown, named Camp Charles Wood, and eventually the headquarters of the replacement center moved there. In October 1942 the training facilities in the Monmouth area became known as the Eastern Signal Corps Training Center. The Signal School, meanwhile, became the Eastern Signal Corps School and included enlisted, officer, officer candidate, and training literature departments.8

To handle the wartime flood of personnel, the Signal Corps opened a second replacement training center in February 1942 at Camp Crowder, Missouri, near the town of Neosho in the southwestern corner of the state. Camp Crowder now received most of the Army's signal recruits, including those entering through the Affiliated Plan, who traveled there to receive basic training. Recruits spent three weeks learning the basics of soldiering: drill; equipment, clothing, and tent pitching; first aid; defense against chemical attack; articles of war; basic signal communication; interior guard duty; military discipline; and rifle marksmanship. In July 1942 the Midwestern Signal Corps School opened its doors at Camp Crowder, with a capacity of 6,000 students, and the following month the Corps' first unit training center also opened there. The headquarters established in

[256]

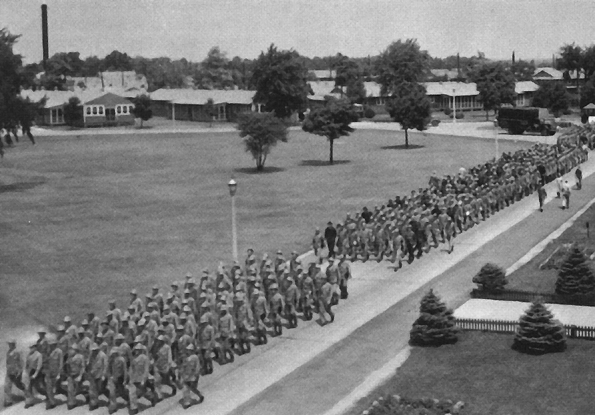

OFFICER CANDIDATES AT FORT MONMOUTH MARCH TO CLASS

October 1942 to administer this group of schools was designated the Central Signal Corps Training Center.9

But the Army's requirements for technically trained manpower were endless. Camp Crowder soon exceeded its capacity, and a third training facility opened in September 1942 at Camp Kohler, California, near Sacramento. Originally intended to provide basic training only, the Western Signal Corps Training Center eventually became the Corps' third replacement training center as well as its second unit training center. The Western Signal Corps School, part of the center, opened at Davis, California, in January 1943. Using the facilities of the University of California's College of Agriculture, the lucky students learned about radio, wire, and radar in a comfortable academic environment.10 Meanwhile, the Signal Corps transferred all aircraft warning training to the Southern Signal Corps School at Camp Murphy, Florida, where classes began in June 1942.11 Thus a nationwide system for preparing signal soldiers took form.

Yet the Signal Corps, like the Army in general, suffered growing pains. The demands of the war mounted faster than the output of the schools, and some men had to be sent to the field before they had learned their jobs. The combat theaters became the finishing schools. Americans invaded North Africa in November 1942, and in early 1943 the Signal Corps instituted a theater training program to

[257]

produce the signal specialists urgently needed for the fight against German General Erwin Rommel's Afrika Korps.12

The Signal Corps also suffered from a shortage of adequately trained officers. In some respects, military communications technology had outstripped the civilian variety; the commercial economy had no equivalent for several of the systems being used by the Army, notably radar. Skilled supervisors were hard to find. Although the War Department authorized an additional 500 signal officers shortly after Pearl Harbor, the Corps had difficulty filling the positions. It could draw upon only 10 percent of Reserve Officers Training Corps graduates and, though the output from the officer training schools gradually increased, so too did the demand for qualified men.13

Initiated before the nation entered the war, the Electronics Training Group provided another source of officers. The Signal Corps required candidates selected for this program to hold degrees in electrical engineering or physics. They received commissions as second lieutenants in the Reserve. After three weeks of training at the Signal School they went to England to work as student observers at radar stations. They spent three months training at British air warning schools, then five months at defense stations in the British Isles. In the aftermath of Pearl Harbor, the demand for officers caused the British to accelerate and shorten the courses, but the training, though sharply curtailed, proved highly valuable to the United States Army.14

Growth was continuous. By mid-1942 the Signal Corps' strength rose to 7,694 officers, 121,727 enlisted men, and 54,000 civilians.15 Approximately fifty thousand technicians entered the Signal Corps through the Enlisted Reserve Corps and its training program before the president ordered its cessation in December 1942.16 There were qualitative changes as well, reflecting new outlooks brought by combat experience. In Signal Corps training, the emphasis shifted increasingly from individuals to teams, who received functional on-the-job training in addition to classroom instruction. Radioteletype teams, for example, practiced on the transatlantic systems in the War Department Message Center (later redesignated as the War Department Signal Center), while base depot companies trained at the various Signal Corps depots. The men worked on the same equipment they would find in the field and received instruction geared to their future service in overseas theaters. Thus the 989th Signal Service Company, scheduled for duty in the Pacific, learned pidgin English in addition to its technical specialties.17 Training continued overseas as well. In sum, approximately 387,000 officers and men completed courses conducted by the Signal Corps.18

The Corps also found that it needed more flexible organizations to fit the widely varying conditions encountered in the theaters of war. New "cellular" Tables of Organization and Equipment allowed units to be constructed out of "building blocks" of sections and teams that could be adapted to the situation at hand. Eventually the Signal Corps adopted a master table, TOE 11-500, "Signal Service Organization," dated 1 July 1943, that provided for fifty-four types of

[258]

WACS OPERATE A RADIO-TELEPHOTO TRANSMITTER

IN ENGLAND

teams that could be assembled in any combination and tailored to specific needs. Each team bore a two-letter designation: EF, for example, denoted a sixteen-man radio link team, while EA denoted a four-man crystal grinding section which cut quartz to receive precise radio frequencies. The cellular concept proved so successful that the Army's other technical services adopted it.19

By mid-1943 military mobilization was virtually complete, and the Army had nearly reached its authorized strength of 7.7 million men. The Signal Corps, in fact, had a surplus of officers by the summer of 1943, though this situation proved to be short-lived. As of June 1943 the Corps' strength had reached approximately 27,000 officers and 287,000 enlisted men.20 Beginning in January 1943 the Signal Corps had also begun to receive female soldiers, members of the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC), later designated the Women's Army Corps (WAC). All told, the Signal Corps received at least 5,000 of these women, known as WACs. Both within the United States and overseas, WACs replaced men in such jobs as message center clerks and switchboard operators, releasing the male personnel for other duties. WACs also worked in film libraries and laboratories and performed signal intelligence duties such as cryptography.21

Black soldiers played a significant role in the wartime Signal Corps. The Army organized a number of black signal units, many of them to perform construction duties. The first of these units to be deployed outside the continental United States was the 275th Signal Construction Company, which went to Panama in December 1941 to build a pole line. It later participated in four campaigns in Europe. The 42d Signal Construction Battalion, activated in August 1943 at Camp Atterbury, Indiana, served in both the European and the Asiatic-Pacific theaters. Despite the notable accomplishments of these and other units, the Signal Corps remained below its proportionate share of black troops throughout the war.22

[259]

Under the demands of history's greatest war, the Signal Corps struggled to meet the Army's communications requirements. But even as it reached its greatest expansion in history to that time, an organizational crisis developed at its headquarters that spelled the end of the chief signal officer's career.

Marshall Reshapes the War Department

In order to streamline the operation of the War Department, Chief of Staff George C. Marshall, Jr., initiated a major reorganization that resulted in the most sweeping changes since the early years of the century. Effective 9 March 1942, the Army was divided into three commands: the Army Ground Forces; the Services of Supply, later renamed the Army Service Forces; and the Army Air Forces. General Marshall placed the Signal Corps and the other technical services under the Services of Supply, commanded by Lt. Gen. Brehon B. Somervell, an engineer known for his energy and administrative ability as well as for his prickly personality.23

For the Signal Corps, the new setup emphasized its logistics responsibilities over its command and control and its research and development functions. In effect, the Marshall reorganization lowered the Signal Corps' status and allowed it less freedom of action. Chief Signal Officer Olmstead now reported through Somervell rather than directly to the chief of staff, and thus lost much of his former control over the Corps' operations.24 Yet the Signal Corps retained its designation as a combat arm, and it continued to provide the doctrine and equipment used by every Army communicator.25

As the war progressed, General Olmstead found it very difficult to reconcile the many facets of the Corps' mission. He was supposed to guide Army-wide communications, although the Signal Corps controlled communications only to division level, below which the using arms took over. At and above his own level, a number of boards shared his work: the Joint Communications Board (Army-Navy) served the Joint Chiefs of Staff and was the highest coordinating agency in military signals; the Army Communications Board served the General Staff, with the chief signal officer as president.26 A Signal Corps Advisory Council, with such members as David Sarnoff of RCA, provided him counsel.27 Such arrangements implied that the chief signal officer was only one player in the complex game of wartime communications, though an important one.

But the Army Service Forces structure, in Olmstead's view, buried him under numerous layers of bureaucracy and hampered operations. As a remedy, he wished to place the chief signal officer on the General Staff and to create a Communications Division with himself at the head and subordinate signal officers in the Ground, Air, and Service Forces. Former Chief Signal Officer Gibbs supported Olmstead's position in a letter to Chief of Staff Marshall. When Marshall in May 1943 appointed a board to investigate Army communications, Olmstead hoped this would provide the opportunity to win the powers he

[260]

GENERAL INGLES

sought. As events unfolded, however, the results differed dramatically from his intent.

The Board to Investigate Communications took testimony from 11 May to 8 June 1943 from officers rep resenting all branches of the Army and from Admiral Joseph R. Redman, Director of Naval Communications. General Somervell, in his appearance before the committee, spoke harshly of the chief signal officer, blaming all of the Corps' problems on him. But the board proved more independent than Somervell may have anticipated. In its report of 21 June, the board asserted that "control and coordination of signal communications within the Army are inadequate, unsatisfactory and confused," and recommended that a Communications and Electronics Division be established on the General Staff. Despite Somervell's opinion, the board members unanimously agreed that the Army's communication problems could not be solved by personnel changes alone.28 But this was unsatisfactory to the chief of staff. General Marshall disapproved the board's recommendation, opting instead to remove Olmstead as chief signal officer.29

Olmstead stepped down on 30 June 1943. His successor, Maj. Gen. Harry C. Ingles, had been a classmate of Somervell's in the West Point class of 1914. During World War I, Ingles was an instructor at the Signal Corps training camps at Leon Springs, Texas, and Camp Meade, Maryland. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s he held a variety of Signal Corps and staff assignments. When World War II broke out, Ingles was in Panama serving as signal officer of the Caribbean Defense Command. Following his promotion to major general in December 1942, he became deputy commander, United States Forces in Europe, early in 1943. Upon assuming the post of chief signal officer a few months later, Ingles inherited the problems faced by Olmstead as he guided the Signal Corps throughout the remainder of the war.30

Maj. Gen. James A. Code, Jr., served both Olmstead and Ingles as assistant chief signal officer and in particular handled supply matters. As the only high-ranking signal officer to serve throughout the war in the same position, he provided continuity to the Signal Corps' policy and administration.31 One thing had clearly been settled by the changes: the Marshall reorganization stuck, and technical service officers had to adapt to it as best they could.

[261]

In contrast to headquarters politics, the Signal Corps had many successes in its practical work for the war effort. Few of its endeavors were more important then providing worldwide communications for America's civilian and military leaders.

In order to tie together the nation's far-flung defense system, the War Department Radio Net expanded its services to become the Army Command and Administrative Network (ACAN), connecting the command headquarters in Washington with all the major field commands at home and overseas. It also maintained connections with the Navy's circuits and the civil communication systems of Allied and neutral nations.32 By replacing radio circuits with radioteletype, which operated automatically, transmission speed improved dramatically.33 The 17th Signal Service Company continued to operate station WAR at the War Department Signal Center, which served as the hub of the network. In January 1943 the center moved from the Munitions Building in downtown Washington, where it had been located since its creation in 1923, to the newly built Pentagon across the Potomac River in Virginia.

Through the ACAN's facilities the Signal Corps provided communications for the conferences held by the Allied leaders, beginning with Casablanca in January 1943 and ending with Potsdam in mid-1945. Arrangements for the Yalta Conference in February 1945 were probably the most difficult and elaborate because the meeting was held on short notice in a remote location on the Crimean Peninsula. A floating radio relay station aboard the USS Catoctin, outfitted with one of the first long-range radioteletypewriter transmitters installed on a ship, enabled President Roosevelt to communicate with Washington and with his commanders in the field. The president was so impressed with the facilities that he referred to the "modern miracle of communications" in his report to Congress.34 In addition to these conferences, the three officers and forty enlisted men of the White House signal detachment, created in the spring of 1942, provided communications for the president and his staff wherever they traveled. Even Roosevelt's private railroad car had its own radio station, with call letters WTE.35

To enable the ACAN to provide worldwide service, the Signal Corps designed an equatorial belt of communication circuits that avoided the polar regions where magnetic absorption of radio waves inhibited operation.36 Maj. Gen. Frank E. Stoner, chief of the Army Communications Service (the division in the Office of the Chief Signal Officer which administered the ACAN), estimated that the Army sent eight words overseas for every bullet fired by Allied troops. An average of 50 million words a day traveled over its circuits by 1945. In May 1944 the Signal Corps, using the ACAN's facilities, sent a nine-word test message around the world in just three and one-half minutes. A similar test a year later accomplished the feat in just nine and a half seconds.37 The independent Army Airways Communications System also depended in part upon the Signal Corps, which installed its equipment and often operated its stations.38

[262]

While circling the globe, the Signal Corps encountered a variety of problems. In Iran its men labored under summertime temperatures high enough to kill mosquitoes and sand flies. Equipment likewise suffered under such extreme conditions. The few signal units stationed in the China-Burma-India Theater faced a scarcity of supplies and transport. They utilized whatever means of motive power were available, including donkeys, camels, and elephants. The pachyderms also proved useful both for handling poles and as elevated platforms from which to string wire (giving new meaning to the term "trunk lines").39 To withstand the torrid climate of the Pacific islands, where field wire deteriorated in just a few weeks, signal equipment required "tropicalization," such as spraying it with shellac, to provide protection from heat, moisture, rust, and fungus. Other tropical hazards included the ants of New Guinea, which attacked the insulation on telephone wires and radio connections.40

Signal Security and Intelligence

During World War II the adversaries engaged in spectacular battles on the ground, in the air, and across the seas. They also waged a less visible, yet vitally important, type of combat over the airwaves: electronic warfare. On the Western Front during World War I, listening to and jamming enemy signals had become routine. But advances in communications technology since 1918 had resulted in sophisticated cryptological equipment that produced codes too complex for the human mind alone to solve. Moreover, the immense volume of radio traffic presented an enormous burden of work for intelligence experts. Equally sophisticated solutions had to be found. The success of the Allies in breaking the Japanese and German cipher systems played a crucial role in the outcome of the war. Only since the 1970s, however, has the full story begun to emerge from records long withheld from public view.

For most of World War II the Signal Corps retained responsibility for the Army's signal security and intelligence activity, passing on its results to the Military Intelligence Division of the General Staff for evaluation. The Signal Intelligence Service (redesignated in 1942 as the Signal Security Service and in 1943 as the Signal Security Agency) mushroomed from approximately three hundred employees on 7 December 1941 to over ten thousand by V-J Day.41 In August 1942 the Signal Intelligence Service moved its headquarters from downtown Washington to Arlington Hall, a former private girls' school in the Virginia suburbs, where it gained the space and security its burgeoning activities demanded. Soon thereafter, Vint Hill Farms near Warrenton, Virginia, became one of the agency's primary monitoring stations. In October 1942 Vint Hill also became the site of the cryptographic school.

The 2d Signal Service Company performed the Signal Intelligence Service's intelligence-gathering duties. Activated at Fort Monmouth in 1939 under the command of 1st Lt. Earle F. Cook, the unit expanded to battalion size in April 1942. In the field its personnel formed detachments that operated the monitoring

[263]

stations within the United States and around the world. During the war the battalion's strength grew to a maximum of 5,000, including WACs. Despite its size, the Army Service Forces denied the Signal Corps' request to enlarge the unit to a regiment.42

The 1942 Marshall reorganization making the Signal Corps a subordinate element of the Army Service Forces created almost insurmountable bureaucratic barriers to the smooth coordination of the collection of communications intelligence by the Signal Corps and its analysis by the Military Intelligence Division. As a result of these strains, operational control of the Signal Security Agency passed in December 1944 to the Military Intelligence Division, and in September 1945 the newly established Army Security Agency took over its functions. By that time the Signal Corps had built a sophisticated intelligence collection system, resting ultimately on new technology.

Several new devices enhanced communications security. For the rapid enciphering and deciphering of written messages, the Signal Corps developed an automatic machine called the Sigaba. William E Friedman, the Army's foremost cryptologist, had played a primary role in its design.43 While the enemy never broke the Sigaba's security during the war, the Army did have a close call when a truck carrying one of the machines disappeared near Colmar, France, in February 1945. After six weeks of frantic searching, soldiers found the lost Sigaba in a nearby river. Fortunately, Nazis had not stolen the truck. Instead, a French soldier, unaware of the vehicle's secret cargo, had apparently "borrowed" the vehicle, abandoning its trailer and dumping the contents, encased in three safes, into the water.44

Encoding and deciphering were only part of the problem. Early in the war Roosevelt and Churchill had used a scrambler telephone to communicate, but the Germans could intercept its signals. By the spring of 1944 a more secure means was available-a radiotelephone system known as SIGSALY.45 High-level commanders also used SIGSALY to direct troops and equipment. Designed by Bell Telephone Laboratories and manufactured by Western Electric, a single SIGSALY terminal weighed about ninety tons, occupied a large room, and required air conditioning. Its massive size obviously prevented its use in the field. Members of the 805th Signal Service Company, made up largely of Bell System employees, operated the equipment. Users spoke into a handset, and their speech patterns were encoded electronically and transmitted by shortwave radio. On both the sending and receiving ends, Signal Corps technicians played special phonograph records, destroyed after each use, which contained the secret key that masked the voices of the speakers with white noise. Pushing communications technology into new frontiers, SIGSALY pioneered such innovations as digital transmissions and pulse code modulation. While the Germans monitored the system, they never succeeded in breaking it. The details of SIGSALY's technical features remained classified until 1976.46

A third security system, known as SIGTOT, permitted two-way teletype conferences between widely separated parties. The equipment provided a written record of the matters discussed and, in some locations, displayed communications

[264]

GERMAN TROOPS USE THE ENIGMA IN THE FIELD

received on a screen. SIGTOT could be operated over any reliable landline or radioteletype channel, and installations were available at nineteen overseas stations by V-J Day.47

While safeguarding the Army's own communications, the Signal Corps actively attempted to breach the security of enemy signals. In the field, radio intelligence units located enemy stations and intercepted them. For example, the 138th Signal Radio Intelligence Company, serving in the Pacific, contained about twenty JapaneseAmerican soldiers, known as Nisei, who could read Japanese cleartext messages.48 To monitor friendly radio traffic, the Signal Corps created a new type of unit known as SIAM (signal information and monitoring). In addition to detecting breaches of security, these units were intended to inform commanders of the state of operations in forward units.49

Certainly one of the greatest signal intelligence feats of the war involved the breaking of the German cipher machine Enigma. While Friedman and his colleagues concentrated on cracking the Japanese codes, the British devoted their efforts to the German encryption systems. Although the Enigma resembled a standard typewriter, it operated by means of complex electrical circuitry. A system of rotors, the number of which could be varied, enciphered messages automatically and in such an infinitely complicated manner that the Germans believed it impregnable.

The Signal Corps, in fact, had purchased an early commercial version of the Enigma in 1928. Additionally, a signal officer, Maj. Paul W Evans, while serving as assistant military attaché in Berlin in 1931, had been given a demonstration of Enigma's abilities by the German War Department. Friedman attempted to solve the machine's mysteries, but failed to do so as his attention became increasingly focused on Japan and the ultimately successful attempt to break the PURPLE code.50

[265]

Fortunately, the Polish secret service succeeded during the 1930s in breaking the Enigma enciphering process and in reproducing a copy of the machine. When Poland fell in 1939, the Poles shared their knowledge with the French and British. By that time the Germans had switched to a more complicated Enigma system which the Poles had not yet broken. That task fell to British analysts at Bletchley Park, who eventually solved the puzzle. Once accomplished, they called the intelligence thereby produced ULTRA. As the British became more adept at using the knowledge gained from ULTRA, it began to have a significant effect on the conduct of the war.51

The British shared their intelligence with the Americans, but they did not immediately divulge their collection methods. When Eisenhower arrived in London in June 1942 to begin preparations for Operation TORCH, the Allied invasion of North Africa, he received a briefing on ULTRA directly from Prime Minister Churchill.52 Meanwhile, Friedman and his staff had been able to use PURPLE intercepts to gain information about German war plans via reports to Tokyo from the Japanese embassy in Berlin.53 Finally, in mid-1943, Friedman and others were given access to the British Enigma machine known as "the bombe." Thereafter American Army officers participated in the intelligence-gathering activities at Bletchley Park.54

Radio deception played an important role in the success of the D-day invasion, and much of the information that made that achievement possible came from ULTRA. ULTRA also proved a significant factor during the Allied drive across France. With their communications system disintegrating, the Germans increasingly relied upon radio and thereby unwittingly allowed ULTRA to reveal more and more of their plans. As the Germans fell back on their homeland, however, they could once again employ wire networks that were less susceptible to interception than radio. Before the Ardennes counteroffensive, the Germans imposed radio silence, which rendered ULTRA impotent. Although ULTRA remained important as a source of information until the end of the war, its role after November 1944 was much reduced.55

Perhaps the most unusual signal security procedure practiced during the war was the use of American Indians as "code-talkers." Because few non-Indians knew the difficult native languages, which in many cases had no written form, they provided ideal codes for relaying secret operational orders. In the European Theater several members of the Comanche tribe served as voice radio operators with the 4th Signal Company of the 4th Infantry Division. While the Army recruited only about fifty Native Americans for such special communication assignments, the Marines recruited several hundred Navajos for duty in the Pacific.56

On the home front the United States government, as it had done during World War I, placed some restrictions upon broadcasting, including the closure of all amateur radio stations on 8 December 1941.57 The president created the Office of Censorship a few days later. It contained a cable division operated by Navy personnel to censor cable and radio communications, and a postal division operated

[266]

COMANCHE CODE-TALKERS OF THE 4TH SIGNAL COMPANY

by Army personnel to censor mail. The domestic press and radio operated under voluntary censorship guidelines, and on several occasions the press leaked the fact that the United States could read the enemy's codes. (Fortunately, the enemy was not paying attention.)58 Domestic commercial broadcasting, meanwhile, continued with minimal disruption.59 Unlike during the nation's two preceding wars, the international undersea cables were never cut. Despite fears that the enemy was using them to gain information, investigations after the war found no evidence that this had been the case.60

During World War II signal intelligence and security assumed critical importance, and the efforts of the Army's intelligence specialists undoubtedly contributed to bringing the war to a speedier conclusion than would have otherwise been possible. Improvements in the handling and dissemination of signal intelligence had, by 1945, helped remedy the deficiencies evident at the time of Pearl Harbor.

While photography had long been part of the Signal Corps' mission, either officially or unofficially, its value and versatility had never been fully appreciated

[267]

or exploited. For the first half of the war the Signal Corps' photographic activities garnered mostly criticism. For one thing, the duties of Army photographers had not been spelled out clearly either for themselves or for the commanders under whom they served. By the end of the war, however, improvements in training and organization had overcome most of the initial difficulties. As for the significance of the Signal Corps' effort, the photographic record of World War II speaks for itself.61

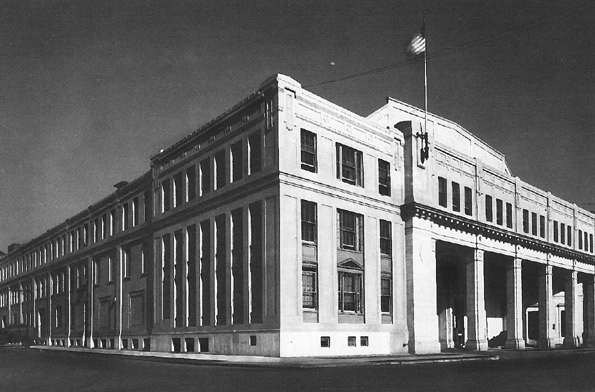

Reflecting the expanded scope of its work during wartime, the Photographic Division of the Office of the Chief Signal Officer became the Army Pictorial Service on 17 June 1942.62 Photographic training initially took place at Fort Monmouth. In February 1942, however, the Signal Corps had purchased from Paramount Studios its studio at Astoria, Long Island, which became the Signal Corps Photographic Center.63 After undergoing renovation, the center opened in May 1942. It included the Signal Corps Photographic School, which absorbed the training function from Monmouth and taught both still-and motion-picture techniques. Professional photographers from the New York press assisted with the instruction. Since Army photographers were also soldiers, they first received basic training at a replacement center to learn to aim and shoot with more than just a camera.64

The Signal Corps retained its photographic facilities at the Army War College in Washington and augmented them by opening a still-picture sub-laboratory in the Pentagon in early 1943. In 1944 the Corps consolidated all of its still-picture laboratory operations there. The Pentagon also housed the Corps' Still Picture Library with its motion-picture counterpart located at Astoria. The Signal Corps also acquired a 300-seat auditorium and four projection rooms at the Pentagon for official screenings.65

The Army had conducted little prewar planning regarding the procurement of photographic equipment and supplies. Consequently, the Signal Corps used standard commercial photographic products almost exclusively. Due to the limited supply of those items, the Signal Corps early in the war urged private citizens to sell their cameras to the Army. Film became officially classified as a scarce commodity and came under the control of the War Production Board. In April 1943 the Signal Corps established the Pictorial Engineering and Research Laboratory at Astoria to conduct tests and experiments of photographic material and equipment. Among its projects the laboratory adapted a radio shelter for use as a portable photographic laboratory and darkroom and developed a lightweight combat camera.66

The Signal Corps provided photographic support to the Army Air Forces at the training film production laboratory at Wright Field, Ohio. Due to friction between the two branches over the division of responsibilities, however, the Signal Corps withdrew its personnel from the laboratory at the end of 1942 and left it wholly an Air Forces operation. Until the opening of the Astoria center, a training film laboratory had also been housed at Monmouth.67

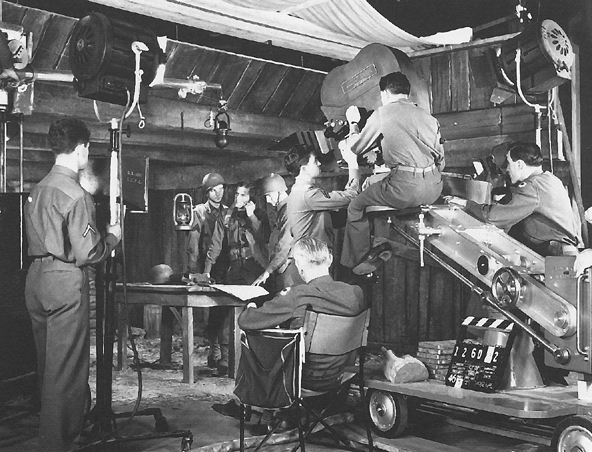

Meanwhile, the Signal Corps continued and expanded its relationship with the commercial film industry. Under the Affiliated Plan, the Research Council of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences sponsored the organization of

[268]

THE SIGNAL CORPS PHOTOGRAPHIC CENTER AT ASTORIA, LONG ISLAND

five photographic companies.68 Moreover, although the Army had previously used films to teach soldiers how to fight, it needed help explaining why the war was necessary. At General Marshall's instigation, Frank Capra, maker of such classic motion pictures as It Happened One Night (1934) and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), received a commission as a major in the Signal Corps in February 1942. As commander of the 834th Signal Service Photographic Detachment, a unit activated especially for the purpose, Capra created a series of orientation films to help the men in uniform understand the war. This series of seven films, titled Why We Fight, proved highly successful at informing both soldiers and civilians about the issues at stake.69 By 1945 Capra had turned out a total of seventeen films for the Army and received the Distinguished Service Medal for his work. One of the members of Capra's documentary film crew was Theodor Seuss Geisel, who later became famous as the children's author, Dr. Seuss.70 In addition to Capra, several other Hollywood figures contributed their talents to the war effort. Producer Darryl F. Zanuck, a colonel in the Signal Corps, supervised Signal Corps photographic activities during the fighting in North Africa and Italy. Critics have long considered Capt. John Huston's San Pietro, depicting operations during the Italian campaign, a masterpiece of documentary filmmaking.71 Recently, however, historian Peter Maslowski carefully scrutinized the authenticity of Huston's film. The term documentary is misleading because Huston staged much of San Pietro's action after the battle took place.

[269]

MAKING A SIGNAL CORPS TRAINING FILM AT ASTORIA

While Huston's film is dramatically effective, it and others of its genre are not necessarily objective accounts of events as they actually happened.72

Photography found a variety of uses. Training films provided an effective means for teaching and indoctrinating the masses of inductees. Studies showed that films cut training time by at least 30 percent.73 The Signal Corps rescored many of these films into foreign languages for use by our non-English-speaking Allies. In the field, the Signal Corps distributed entertainment films that provided an important means of recreation for the soldiers. On the home front, still and motion pictures marked the progress of the struggle. Newsreels, shown in the nation's theaters, brought the war home to millions of Americans in the days before television. Signal Corps footage comprised 30 to 50 percent of each newsreel.74 Meanwhile, the still pictures taken by Army photographers illustrated the nation's books, newspapers, and magazines. Although the government placed some restrictions upon the kinds of images that could be shown, the public received a more realistic look at warfare than ever before.75

Black and white photography remained the norm for combat coverage, but Army cameramen used color film to a limited extent. In addition to being more costly, color film required more careful handling than black and white. A signifi-

[270]

cant innovation occurred with the development of telephoto techniques, or the electronic transmission of photographs, which meant that pictures could reach Washington from the front in minutes. That technology anticipated the "fax" machines of a later era.76

For planning purposes General Marshall ordered the compilation of shots illustrating the tactical employment of troops and equipment for presentation weekly to selected staff officers and commanding generals in Washington and all the overseas theaters. Each week the Signal Corps reviewed more than 200,000 feet of combat film to compile the Staff Film Report. Declassified versions became combat bulletins that were issued to the troops.77

V -Mail represented a new variation in photography. To save precious cargo space in ships and airplanes, the bulk of personal correspondence could be reduced by microfilming it. While the Army Postal Service had overall responsibility for V-Mail operations, the Signal Corps managed its technical aspects. The Signal Corps operated V-Mail stations in active theaters while commercial firms, such as Eastman Kodak, took over where conditions permitted. At the receiving end, the film was developed, enlarged, and printed into 4½ by 5 inch reproductions. V-Mail service began in the summer of 1942 and grew rapidly. From June 1942, when 53,000 letters were handled, usage skyrocketed to reach a peak volume of over 63 million letters processed in April 1944.78 Although the processing was a laborious and mind-numbing procedure, it paid off in soldiers' morale and the peace of mind of their loved ones at home. Official Photo Mail provided similar service for official documents with the Signal Corps, for security reasons, doing all the processing.79 In addition to mail, unofficial photos taken by the soldiers themselves had to be developed by the Signal Corps and censored. By April 1944 this amounted to 7,000 rolls in an average week in the European Theater alone.80

But some believed there was more to be exposed than just film. In August 1942 the Senate Special Committee Investigating the National Defense Program, chaired by Senator Harry S. Truman, began initial inquiries into the Army's photographic activities. The committee's questions focused on the training film program and its relationship with Hollywood. Critics had alleged that the Research Council of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, which had handled all of the Signal Corps' contracts, exerted too much influence over the program. In particular, they had focused on the role of Colonel Zanuck: he concurrently served as chairman of the Research Council, executive of a film studio (Twentieth Century-Fox), and an officer of the Signal Corps.

The impending congressional inquiry spurred General Somervell to initiate his own series of investigations. As a result, Somervell directed Chief Signal Officer Olmstead to decentralize the operations of the Army Pictorial Service and give more authority to the Signal Corps Pictorial Center. In the future, a western branch of the center would oversee all new production projects in Hollywood, with the Research Council retained in an advisory capacity only.

Early in 1943 the Truman Committee began hearings on the Army Pictorial Service. Although Olmstead had already begun to make the recommended

[271]

SIGNAL CORPS PHOTOGRAPHIC TECHNICIAN

IN FULL REGALIA

administrative changes, Somervell removed the Army Pictorial Service from the Signal Corps' control and placed it directly under his own supervision. Meanwhile, the Truman Committee found no fault with the films produced in Hollywood by the Research Council and exonerated Zanuck. After the hearings had concluded, Somervell in July 1943 returned the Army Pictorial Service to the Signal Corps, now headed by General Ingles. Truman, whose work on the committee had made him well known, went on to become Roosevelt's presidential running mate in 1944. When Roosevelt died in office in April 1945, Truman became the nation's thirty-third president.81

Somervell remained worried about the Signal Corps' "picture business" as he received complaints about the confusion surrounding photographic operations in the field. Although Army photographers took millions of pictures, too many merely showed high-ranking officers engaged in such activities as eating lunch, reviewing parades, or receiving awards. The new chief signal officer continued to make improvements in the Pictorial Service, and Somervell's concerns gradually disappeared.82

The Army Ground Forces' tables of organization assigned one photo company to each field army. Each company contained four general assignment units: Type A units took still and silent motion pictures, while Type B units shot newsreels. The company also included two laboratory units. In the field, the company's personnel actually operated in small teams and detachments wherever needed. Detachments of the same company might be scattered throughout more than one theater. Subsequent revisions to the tables of organization provided for more flexible units using the cellular concept. Special photographic teams from the Signal Corps Pictorial Center supplemented the field units and covered all headquarters installations as well as the Army Service Forces. The assignment of photographic officers to the staffs of theater commanders, which the War Department directed in May 1943, resulted in improved supervision of photographic activities.83

As the war began to wind down, Capra, now a colonel, directed two films to explain what happened next and to keep morale up. The first, Two Down and One to Go, dealt with the defeat of Germany and the Army's plans for redeployment

[272]

SIGNAL CORPS CAMERAMEN WADE THROUGH A STREAM DURING THE INVASION OF NEW GUINEA,

APRIL 1944

to the Pacific. In particular, it explained the Army discharge system, a topic on everyone's mind. The film was released simultaneously to military and civilian audiences on 10 May 1945. Two weeks later the Army released the second film, On to Tokyo.84 In July 1945 a Signal Corps photograph of the "Big Three" world leaders at Potsdam (President Truman, Prime Minister Atlee, and Marshal Stalin) became one of the first published news pictures transmitted by radio for reproduction in color.85

In retrospect, the Signal Corps cameramen performed a remarkable service for historians and for the understanding of World War II by future generations. Many of their pictures, as critics complained, were banal or merely intended to compliment the local brass. Yet they also took memorable pictures, which have helped to define the image of the war for those who never saw it. Overall, they bequeathed a unique, epic, visual record without a parallel for drama, amplitude, and detail.

Equipment: Research, Development, and Supply

Maj. Gen. Roger B. Colton headed the Signal Supply Services, which bore the responsibility for research and development as well. A graduate of Yale University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Colton had worked at the Monmouth laboratories with William Blair on the development of radar. After Blair's retirement in 1938, Colton had succeeded him as director of the Signal

[273]

Corps Laboratories.86 Thus he approached the problems of wartime research and development with an admirable technical background.

As with training, the wartime expansion of research and development activities at Fort Monmouth soon overwhelmed the available facilities. Consequently, the Corps rapidly set up new laboratories nearby. Early in 1942 the Signal Corps Radar Laboratory, later known as the Camp Evans Signal Laboratory, opened at Belmar, New Jersey.87 Other new research facilities included the Eatontown Signal Laboratory for work on wire, meteorology, and direction-finding and the Coles Signal Laboratory at Camp Coles in Red Bank, New Jersey, which developed radio equipment. The number of laboratory personnel working under Colton increased to 358 officers and over 14,000 civilians within six months after Pearl Harbor.88 While greatly expanding its own facilities, the Signal Corps also depended heavily upon commercial firms such as Westinghouse and General Electric for research and development.89

Problems began with supply. To control the nation's economic mobilization, the federal government created a variety of agencies. In January 1942 President Roosevelt formed the War Production Board, which played a role similar to that of the War Industries Board during World War I. By suspending the manufacture of many consumer goods, such as cars and light trucks and commercial radios and phonographs, the board forced companies to devote full production to military items.90 But for industry in general, and the electronics industry in particular, prewar estimates fell far below actual requirements, and shortages of essential materials held up production.

In the case of rubber, vital to the manufacture of field wire, the Japanese had cut off much of the supply from the Far East. Although the search began for synthetic materials, technical problems in their production and labor shortages slowed their introduction. Quartz needed for radio crystals remained scarce, and efforts to produce an artificial substitute met with only limited success.91 To obtain enough copper, "the metal of communications systems," in the summer of 1942 the Army furloughed 4,000 soldiers who had formerly been copper miners. Copper pennies became rare, replaced by zinc versions. Silver, an excellent electrical conductor and not on the government's list of critical materials, became a copper substitute in electrical equipment, and half a billion dollars' worth of silver coins and bullion were borrowed from the United States Treasury for conversion to transformer windings and other items.92

The Signal Corps had received its first billion-dollar budget appropriation in March 1942. To meet the need for trained supply officers, the Signal Corps opened a school for supply training at Camp Holabird, Maryland, late in 1943. But long before that the Corps was accepting every two weeks as much equipment as it had acquired throughout the entire course of World War I.93The "big five" electronics manufacturers (Western Electric, General Electric, Bendix, Westinghouse, and RCA) received the bulk of the contracts, although the government required that a certain percentage of the work be subcontracted to smaller firms. Radio and radar equipment accounted for over 90 percent of the Corps' procurement budget.94

[274]

The burgeoning size of the Signal Corps' equipment catalogue gives an idea of the increased specialization of its activities. While the Corps had used some 2,500 different items of equipment during World War I, it needed more than 70,000 by June 1943. By the war's end the number of separate items had risen to over 100,000.95 The sheer magnitude of the supply effort created problems of production, inspection, storage, and distribution that dwarfed anything the Corps had ever faced and could scarcely have been imagined by prewar planners. The provision of spare parts, in particular, plagued the Corps throughout the war.96

Radar equipment remained in short supply. Since there had been no radar industry prior to the war, one had to be built from scratch.97 The Signal Corps continued to maintain its Aircraft Radio Laboratory at Wright Field, which established a separate radar division in 1942. Through the Joint Communications Board, the Army and Navy worked together on radar development.98

In solving the radar problem, the Signal Corps benefited greatly from the contributions of civilian scientists working for the National Defense Research Committee (NDRC), a government agency established in June 1940 through the efforts of Dr. Vannevar Bush, a renowned electrical engineer who served as president of the Carnegie Institution of Washington and chairman of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics. Modeled after the NACA, the committee included military representatives and cooperated closely with the technical services of the Army, particularly the Signal Corps, on matters of applied research.99

One of the most important accomplishments of the NDRC was the establishment of the Radiation Laboratory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology where physicists worked on the development of microwave radar. Progress was greatly facilitated by the exchange of technical information with the British, whose discovery of the resonant-cavity magnetron, an electronic vacuum tube that could produce strong, high-frequency pulses, proved especially valuable. Details of this breakthrough had been brought to the United States by the Tizard Mission, a group of scientific experts who arrived in August 1940, led by Sir Henry Tizard, rector of the Imperial College of Science and Technology.100

In 1941 the NDRC became part of the new Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), also administered by Dr. Bush. The OSRD focused its efforts on weapons development, notably radar, as well as on radio and other forms of communication. The proximity fuze numbered among the projects with which it became involved. In general, the OSRD negotiated contracts with research institutions, both universities and private firms, as well as with government agencies such as the Bureau of Standards. Under its auspices the government undertook the Manhattan Project to develop the atomic bomb, an endeavor that was subsequently transferred to the Army.101

Thanks to the work of both military and civilian scientists, radar technology improved dramatically during the course of the war. Microwave devices, such as the SCR-582 introduced in North Africa, proved especially valuable. Their shorter wavelengths and narrower beams of radiation made them less susceptible to

[275]

enemy jamming.102 Even the British, who had earlier severely criticized American radar, praised the new versions.103 Another model, the SCR-584, was "the answer to the antiaircraft artilleryman's prayer" and the "best ground radar airplane killer of the war."104 With a longer range, it replaced the SCR-268.105 Beginning at the Anzio beachhead in February 1944, the SCR-584 proved to be an excellent gunlaying radar. The British, who had chosen not to develop radar for antiaircraft purposes, used the 584 to defeat German "buzz bomb" (V-1) attacks that began in the summer of 1944. The 584 further demonstrated its versatility through additional uses as an aid in bombing and for meteorological purposes to detect storms. Both the SCR-582 and the 584 were the products of the Radiation Laboratory.106

Radio relay equipment, the marriage of wire and radio, first used in North Africa, proved to be one of the war's most significant innovations in communications, combining the best features of both systems. Given the nomenclature AN/TRC, for Army-Navy Transportable Radio Communications, it became known as antrac. The multichannel equipment provided several speech and teletype circuits and connected directly into the telephone and teletype switchboards at either end. It could be installed much faster than conventional wire lines and with fewer personnel. During fast-moving operations, the equipment could be carried forward in a truck and trailer. It differed from standard field radios in that it offered duplex connections and could not be intercepted as easily. Antrac could also transmit pictures, drawings, and typewritten text by facsimile. For operations in the Pacific, antrac (or VHF, as it was commonly called in this theater) solved the problem of communicating over water and hostile jungle terrain. It was also used for ship-to-shore communications and to link beachheads to bases.107

At the Signal Corps' request, Bell Laboratories developed the first microwave multichannel radiotelephone system, known as AN/TRC-6. Designed to provide trunk lines for a field army, it was capable of high-grade two-way communications over thousands of miles. AN/TRC-6 arrived in Europe in time for use at the end of the war and became a major communication link in the Rhine Valley. In the Pacific Theater, the equipment moved no farther west than Hawaii before the war ended.108

Other advances in communications equipment included the development of spiral-four cable, an improvement over W-110, which had proven of limited use during maneuvers. Originally developed by the Germans, spiral-four received its name from the spiral arrangement of its four wire conductors around a fiber core. Encased in an insulating rubber jacket, the wire provided "long-range carrying power with minimum electrical loss and cross talk."109 Spiral-four had a greater carrying capacity than multiple open wire lines and did not require tedious installation procedures: setting poles, stringing wire, and attaching crossarms. It could be laid on the ground or through water (fresh or salt) or buried underground. The new wire made long-range, heavy-duty communications possible, and the Signal Corps accepted spiral-four as standard in February 1942. In addition to its other fine qualities, natives in the Southwest Pacific found that the wire made "the best

[276]

belts they ever had," reminiscent of how curious Civil War soldiers had once used then-novel field telegraph wire for various purposes unrelated to communication.110 The Signal Corps continued to use W-110 for forward communications as well as the lighter-weight assault wire, W-130.111

Despite new developments, the Signal Corps still relied upon older electrical items such as the field telegraph set TG-5 (buzzer, battery, and key), the field telephone EE-8 (battery powered), and a sound-powered phone TP-3 requiring no battery.112 The original walkie-talkie, designed to be carried on a soldier's back, underwent significant changes to become the SCR-300, an FM set with a range of two miles and which weighed about thirty-five pounds.113 British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, attending military demonstrations at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, in June 1942, took particular delight in carrying and operating this device.114 The first models reached the field, where they found ready acceptance, in 1943. Another short-range, portable telephone, the SCR-536, became the infantry frontline set. Operating on AM and weighing just five pounds, it could be used with one hand. Hence this device received the name “handie-talkie.”115

Armored forces adopted FM radios in the 500 series, and those of the 600 series belonged to the Field Artillery. The clarity of the static-free FM signals allowed soldiers to communicate over the din of artillery firing and tank noise. One infantry battalion radio operator wrote: "FM saved lives and won battles because it speeded our communications and enabled us to move more quickly than the Germans, who had to depend on AM."116

The rush to produce new equipment resulted in problems with systems integration. For instance, the FM walkie-talkie could not communicate with the AM handie-talkie. Moreover, because the frequency range of FM tank radios did not overlap that of the walkie-talkie, tank-infantry teams could not talk to each other.117 Though various attempts were made to solve the problem, the war ended without a satisfactory answer.

The growing demand for electronic communications and the multiplicity of new devices demanded innovations to maximize usage of the finite number of available frequencies. The development of single sideband radio contributed to the conservation of frequencies in the crowded shortwave sector of the electromagnetic spectrum. This technique provided circuits using only one-half of the frequencies that extend on either side of a radio's central frequency, saving the other half for use by others.118

During World War II radio's usage expanded beyond simply a means of communication to more deadly pursuits. To improve artillery fire control, the Signal Corps became involved in the development of the proximity, or variable time, fuze. This device consisted of a tiny radar (or doppler radio) set built into the nose of an artillery shell that sensed a target within a hundred feet and automatically detonated when directly over it, rather than upon impact. The fuzes proved considerably more effective than conventional types.119

After General Ingles became chief signal officer in 1943, he streamlined the Corps' organization, separating staff and operating functions. In a move that

[277]

THE SCR-300, BETTER KNOWN AS THE WALKIE-TALKIE; BELOW, RADIOMAN WITH HANDIE-

TALKIE (SCR-536) ON OKINAWA

[278]

reflected sound organizational sense plus the growing complexity and size of both operations, he also split General Colton's Signal Supply Services into two elements, divorcing procurement and distribution from research and development.120 But during the buildup for the Normandy invasion, the Signal Corps was obliged to commandeer trained personnel from wherever it could, including its own laboratories. Consequently, Camp Evans, Eatontown, and Monmouth all took significant cuts during 1943. Yet the restriction on research touched only about 17 percent of the total projects, chiefly in the areas of optics, acoustics, and meteorology.121

Nevertheless, the Signal Corps' cutbacks assisted the Army Air Forces in its attempts at expansion.122 Ever since the inception of the air service, the Signal Corps had struggled with it for authority. Growing ever more powerful as the war progressed, the air arm proceeded with its drive for autonomy. Under the Army's 1942 reorganization the Air Forces had received responsibility for the procurement, research, and development of all items "peculiar" to it.123 At that time the airmen had tried to capture air electronics, but General Somervell had prevented the transfer of the function.

While the Signal Corps won this opening round, it ultimately lost the battle. Its chronic shortage of scientists, exacerbated by the 1943 personnel reductions, became a decisive factor in the struggle between the two branches. The greatest difficulties stemmed from the Corps' shortcomings in supplying spare parts for radar equipment. The situation came to a head in June 1944 when Maj. Gen. Barney M. Giles, chief of the air staff, completed a study for the chief of staff listing all the reasons why aircraft electronics should be transferred to the Air Forces. Upon reviewing the study, General Marshall agreed with Giles' position, though Somervell lodged his objections to the separation and Chief Signal Officer Ingles argued that it would split "the essential oneness" of all Army communications. Marshall directed that the change be made effective on 26 August 1944.

The details of deciding which items were in fact "peculiar to the AAF" took somewhat longer to determine. The SCR-584, for example, was used by both the air and ground forces. After considerable negotiation, the transfer was completed in the spring of 1945. As a result, the Signal Corps relinquished control over approximately 700 items of electronic equipment along with several of its facilities, including the Aircraft Radio Laboratory at Wright Field. In addition, it lost 600 officers, 380 enlisted men, and over 8,000 civilians from its roster. Among the officers transferred to the Air Forces was General Colton, head of research and development.124

Yet there was more to the story than the parochial view of bureaucratic gains and losses. The scientific research effort that accompanied World War II far surpassed anything the nation had ever seen. It was an integrated endeavor that extended beyond the capabilities of the military's technical services to embrace nearly the entire civilian research establishment of the United States. World War II, moreover, witnessed a fundamental shift whereby the federal government,

[279]

rather than private industry, became the primary source of funds for research and development.125 Despite the dismantlement of the OSRD after the war, military research and development had become institutionalized both within the Army and throughout industry. Furthermore, the growth of the nation's scientific effort meant that the United States no longer needed to look to Europe for technological leadership.126

The Signal Corps' Contribution

At its peak strength, in the fall of 1944, the Signal Corps comprised over 350,000 officers and men, more than six times as many as it had needed to fight World War I. By May 1945 its numbers had declined somewhat to 322,000 and represented about 3.9 percent of the Army's total strength of well over eight million.127 This percentage corresponded closely to the Signal Corps' proportion of the AEF in 1918. Despite the vast increase in the numbers of men engaged, however, the Signal Corps' battle casualties did not increase substantially over those for the earlier war, totaling just under four thousand officers and men. This relatively low casualty rate clearly reflects the fact that the Signal Corps no longer provided frontline communications.128

In other respects, however, the Corps' contribution to the struggle grew enormously. Both strategically and tactically, World War II differed immensely from World War I. New tactics based on mechanization and motorization freed armies from the deadlock of trench warfare. Commanders using field radios could maintain continuous contact with their troops during rapid advances. The increased flexibility of communications helped make mobile warfare possible. Moreover, by means of the ACAN system, worldwide strategic communications became commonplace and required only minutes instead of hours.129

More than ever before, success in combat depended upon good communications. General Omar N. Bradley, who finished the war as commander of the 12th Army Group, testified to this reality in his memoirs. Referring to his telephone system as "the most valued accessory of all," he went on to say:

From my desk in Luxembourg I was never more than 30 seconds by phone from any of the Armies. If necessary, I could have called every division on the line. Signal Corps officers like to remind us that "although Congress can make a general, it takes communications to make him a commander."130 |

Never had the maxim been so true as when fast-moving struggles swept over most of the surface of the earth. At home and in all the combat theaters, the Signal Corps provided the Army with rapid and reliable communications that often made the difference between defeat and victory.

[280]

Return to Table of Contents

Return to Chapter VI |

Go to Chapter VIII |

Last updated 3 April 2006 |