U.S. Army become more professional during this period? What reforms contributed to this result?

2. The wars against the Seminoles lasted for years and took thousands

of troops to subdue and remove a relative handful of Indians. Why did this take so long? Which tactics worked and which did not?

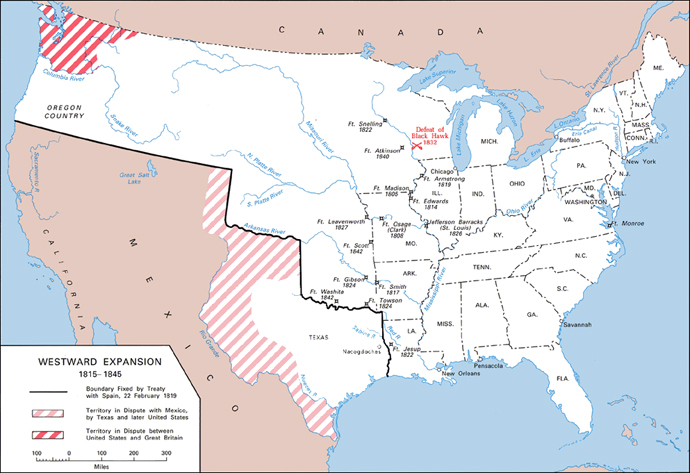

3. What were the major roles and missions of the Army in the early settlement of the West from 1815 to 1845? How effective was the Army in performing these missions?

4. What was the "expansible army" policy proposed by Secretary of War Calhoun? To what degree do we have an expansible army today? What were some alternatives to this idea in the nineteenth and twentieth

centuries?

5. What were the advantages and disadvantages of using contractors

to provide military support such as rations, clothing, transportation,

and other services during this period? Why was the Army so slow to develop its own internal logistics capability?

6. Compare and contrast the Army on the eve of the War of 1812 to the Army on the eve of the war with Mexico. What were the similarities

and differences? What factors accounted for the changes?

Coffman, Edward. The Old Army: A Portrait of the American

Army in Peacetime, 1784–1898. New York: Oxford University

Press, 1986.

Johnson, Timothy. Winfield Scott: The Quest for Military Glory.

Lawrence:

University Press of Kansas, 1998.

Mahon, John K. History of the Second Seminole War, 1839–1842.

Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1985.

Morrison, James L., Jr. "The Best School in the World": West

Point, The Pre–Civil War Years, 1833–1866, Kent, Ohio: Kent

State University

Press, 1986.

Prucha, Francis P. The Sword of the Republic: The United States

Army on the Frontier, 1783–1846. New York: Macmillan,

1969.

Remini, Robert V. Andrew Jackson and the Course of American

Empire, 1761–1821. New York: Harper & Row, 1977.

Skelton, William B. An American Profession of Arms: The Army

Officer Corps, 1784–1861. Lawrence: University Press of

Kansas, 1992.

Other Readings

Browning, Robert S. Two If By Sea: The Development of American

Coastal

Defense Policy, Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press,

1983.

Goetzmann, William H. Army Exploration in the American West

1803–1863. Austin: Texas State Historical Association, 1991.

Sprague, John T. The Origin, Progress, and Conclusion of the

Florida War. Tampa, Fla.: University of Tampa Press, 2000.

Walton, George H. Sentinel of the Plains: Fort Leavenworth and

the American West. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1973.

![]()