![]()

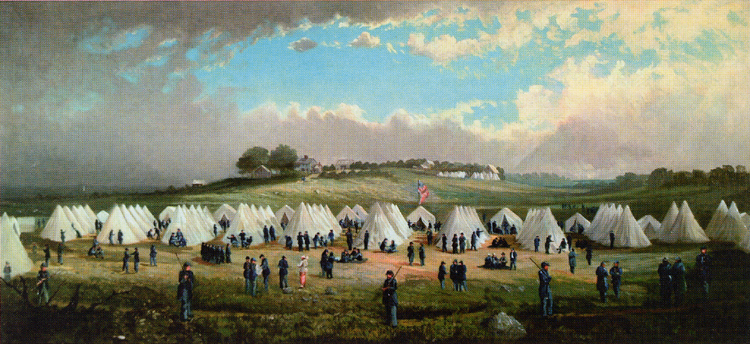

THE CIVIL WAR, 1861

![]() uring the administration of President James Buchanan, 1857–1861, tensions over the issue of extending slavery into the western territories mounted alarmingly and the nation ran its seemingly inexorable course toward disunion. Along with slavery, the shifting social, economic, political, and constitutional problems of the fast-growing country fragmented its citizenry. After open warfare broke out in Kansas Territory among slaveholders, abolitionists, and opportunists,

the battle lines of opinion hardened rapidly. Buchanan quieted Kansas by calling in the Regular Army, but it was too small and too scattered to suppress the struggles that were almost certain to break out in the border states.

uring the administration of President James Buchanan, 1857–1861, tensions over the issue of extending slavery into the western territories mounted alarmingly and the nation ran its seemingly inexorable course toward disunion. Along with slavery, the shifting social, economic, political, and constitutional problems of the fast-growing country fragmented its citizenry. After open warfare broke out in Kansas Territory among slaveholders, abolitionists, and opportunists,

the battle lines of opinion hardened rapidly. Buchanan quieted Kansas by calling in the Regular Army, but it was too small and too scattered to suppress the struggles that were almost certain to break out in the border states.

In 1859 John Brown, who had won notoriety in "Bleeding Kansas," seized the Federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in a mad attempt to foment a slave uprising within that slaveholding state. Again Federal troops were called on to suppress the new outbreak, and pressures and emotions rose on the eve of the 1860 elections. Republican Abraham Lincoln was elected to succeed Buchanan; although he had failed to win a majority of the popular vote, he received 180 of the 303 electoral votes. The inauguration that was to vest in him the powers of the presidency

would take place March 4, 1861. During this lame-duck period, Mr. Buchanan was unable to control events and the country continued to lose its cohesion.

Secession, Sumter, and Standing to Arms

Abraham Lincoln’s election to the Presidency on November 6, 1860, triggered the long-simmering political crisis. Lincoln’s party was opposed to the expansion of slavery into the new western territories. This threatened both the economic and political interests of the South, since the Southern states depended on slavery to maintain their way of life and their power in Congress. South Carolina on December 20 enacted an ordinance declaring that "the union now subsisting between South Carolina and other States, under the name of the ‘United States