Department of the Army Historical Summary: FY 1979

2.

Operational Forces

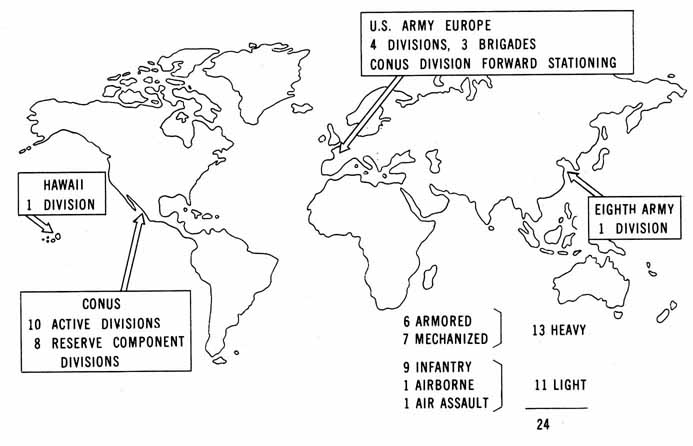

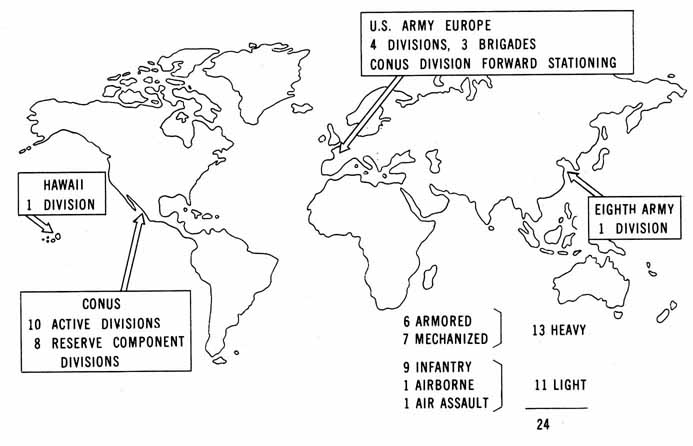

In the fall of 1979, the Army’s four-year expansion was complete. The expansion created three new divisions without an increase in troops and established the most stringent standards ever for peacetime readiness. No one doubted that the Army was stronger and certainly leaner than at any other time since the Vietnam War. It was the one credible deterrent against expanding communist forces. But, it was also an Army with some serious organizational problems.

Of those problems, none presented a larger threat to the military’s objectives than the inability of units to meet their deployment schedules. This was caused mainly by resource shortages and complex mobilization procedures. The restructuring of the Army into twenty-four divisions, active and reserve components, had been completed. Nevertheless, except for formations permanently stationed in Europe and Korea (the chief beneficiaries of the specialized programs to enhance force readiness), the Army was still deficient in usable battalions. Only four of the ten active divisions on the American mainland were capable of deploying overseas in an emergency. Furthermore, the logistics story was even bleaker.

For years, logistics had offered reasonable assurance that whatever edge an enemy might have, superior and timely support would put matters right. All that changed as the decade ended. With more active Army manpower being allocated to the improvement of active combat forces, more and more of the combat service support functions were being transferred to the undermanned reserves. By 1978, virtually no base existed that could sustain combat troops beyond the first few weeks of a war. Heightened concern for its power and force mix on the battlefield had brought the Army to the edge of logistical subsistence. Only patchwork solutions were visible.

Despite a long succession of reorganizations and manpower retention programs, the reserve components—both logistical and combat forces—were not adequately prepared. They were required to provide more than half of all the combat battalions necessary for early deployment in the event of a war. These

[5]

FIGURE 1 - STATIONING OF 24 DIVISIONS

supplemental battalions were affiliated with active forces for training and operations. Four understructured regular divisions, the 7th and 25th Infantry Divisions and the 5th and 24th Mechanized, had recently been rounded out with affiliated brigades. And yet, as NIFTY NUGGET 78 (an exercise in mobilization and deployment) demonstrated, this procedure would not suffice in a European war. Even before the fighting began, many reserve units would be heavily taxed in an effort to supplement the active forces. Barely a month into combat, the Individual Ready Reserve would be quickly exhausted.

In terms of mobilization, the Army ended the year in considerable trouble. Although the fiscal year 1980 request takes aim at the most glaring deficiencies, especially in prepositioned equipment, few expect a significant improvement to occur soon. This is how it has always been in the peacetime reinforcing establishment—there are always ammunition shortages, manpower shortages, and inadequate funds. To express concern, as was being done throughout the Army, is not in itself going to hasten significant improvement. Better for now, as the Chief of Staff put it, to establish realistic priorities and to balance the desirable at home against the necessary abroad. For it is abroad that the

[6]

Army’s basic mission lay, and where its efficiency to fight will have to be judged. It is also abroad that the Seventh Army lay, with a heritage of neglect which has yet to be fully overcome.

The “lost decade,” as it was known to the fifteen nations of the Atlantic Alliance, had ended four years earlier when NATO military advantages were lost to the Warsaw Pact and permanent inferiority in Europe loomed. Since then, force improvement programs have increased, but at a price. Every NATO member had pursued their force improvements individually, with little allied coordination. By the end of the 1970’s, the armies of the alliance were less operationally compatible than they had been five years before. Planners generally agreed that of all the NATO armies, U.S. Army, Europe (USAREUR), would have to take the lead in standardization.

In 1979, U.S. Army, Europe, was about 200,000 soldiers strong, or more than a quarter the strength of the active Army. With the exception of Brigade 75 (which had transferred in late January to northern Germany) and the Berlin Brigade, USAREUR was assigned to the Central Army Group. U.S. Army, Europe, contained four divisions, four separate brigades, and two armored cavalry regiments. The forces were becoming stronger, both armored and mechanized, an expression of shock action and firepower directed at Soviet advances. For example, cavalry units exchanged their Sheridans for M60’s, 210 Cobra/TOW’S in ten companies were installed on the ground, and armored units increased the size of their tank crews. Artillery forces had been strengthened by the arrival of three battalions of medium and heavy artillery (with increases in the number of tubes for every battery) and adoption of a novel uploading system to quicken the responses of ammunition units alerted for battle. Additional infusions of equipment and technology were to follow, and progress was so sure that in 1978 a proposal was made to turn over to Germany nearly all the base management operations. The proposal, referred to as USAREUR—An Army Deployed, would be negotiated with the NATO allies and would better enable the Army to prepare for war.

In the early years of the alliance, questions of cross-servicing and standardization had rarely arisen. With American military assistance programs supplying the allies with equipment, the standard division reflected American traditions. Unfortunately, the disappearance of the division coincided with the Vietnam

[7]

War, and by the time the United States could again focus on its NATO forces, the allied armies could hardly so much as communicate across corps boundaries.

This was the situation, when the allies began exploring “interoperability.” Serious disagreements over strategy, questionable dollar savings, and national will and pride had all hindered cooperation. However, everyone did agree on one point: not until 1983, at the earliest, would stocks of ammunition available to the alliance sustain a thirty-day war. With that single acknowledgement, working group discussions on both sides of the Atlantic continued as the fiscal year ended.

In the other global trouble spot where the Army stood on guard, it was a year of discovery and surprise. The withdrawal of the 2d Infantry Division from its sectors in South Korea, announced by President Carter in 1977, had been based on a favorable assessment of the peninsular balance. But in 1978, new intelligence indicated that the earlier estimate had been overly optimistic, that North Korea’s forces, the forth largest in the communist world, had much more capability to launch an invasion of the Republic of Korea than anyone in Seoul or Washington had previously thought. In July 1979 the President decided to temporarily freeze combat withdrawals. Certain supporting units would still depart in 1980, but air defense units would leave somewhat later. Equipment would continue to be turned over to the Korean forces. Other than that, the Army would remain on duty in South Korea.

The planned withdrawals had brought about an important change in command and control. The idea of a single headquarters directing Korean and American forces had been under consideration for a number of years, and had been proven, as far as planners were concerned, by the I Corps (ROK/US) Group in the western sector. Late in 1978, therefore, symbolizing our commitment to the Republic of Korea, the Combined Forces Command was inaugurated in Seoul. The commander in chief was an American, and commanded the Eighth U.S. Army. His deputy was a South Korean. The command proved its worth as a planning tool in managing TEAM SPIRIT, their first training exercise. By completion of the exercise late in the fiscal year, 160,000 troops had participated. They tested not only interoperability, but also reinforcement by American combat elements from stations as far away as Hawaii.

One of those elements was Hawaii’s 25th Infantry Division,

[8]

at the time a subordinate unit of Army Forces Command. For years, the absence of a headquarters specifically responsible for the Army in the Pacific (other than Korea and Japan) had been regarded as a serious weakness. That was the official interpretation given by the Joint Chiefs. Consequently, on 23 March, the Army Western Command was established at Fort Shafter, giving the Army a planning nucleus to hasten its passage to war in the Pacific theater. Now, as the Pacific reinforcing contingent, the 25th Division had its next higher headquarters right at home.

Building up the land forces in Europe and maintaining a position in the Pacific had been American goals for nearly three decades. It was something of a political departure, then, to create a rapid deployment force for use in global contingencies outside NATO. This raised questions in Washington about fundamental American interests and the projection of power.

As originally conceived and constituted by Army planners, the force was a mix of units from all the services—the Army’s contribution being a command and control headquarters, light and heavy divisions and brigades, and support elements. It was not, officials emphasized, a numerical addition to the strength of the military establishment, but a quick combined reaction force which, if called for in Third World emergencies, would rely upon existing units without mobilization. How the Army and the other services would work around their grievous shortages was not resolved. But increases in spending in fiscal year 1980 offered a good beginning.

When the fiscal year ended, the Army’s rapid deployment force was still uncertain. Decisions concerning commanders, basing, and airlift would take months to emerge from a cautious administration.

Support for the Civil Authorities

In another field of combined operations, humanitarian relief and assistance, and teamwork and readiness had long been the accepted standard. Nowhere was this demonstrated under conditions of greater urgency than in the grisly mission of recovery in Jonestown, Guyana. Three commands joined in the task force to evacuate the remains of the American cult members: the U.S. Readiness Command, the Military Airlift Command, and the U.S. Southern Command. The two-month operation cost the Department of Defense over $4 million and was possibly the most spectacular military commitment to emergency assistance.

[9]

Before the year was out, fire fighting, snow removal, and hurricane and flood relief would engage the Army’s forces, from Hawaii to the Caribbean. The nuclear incident at Three Mile Island called forth several transportation units. Finally, as throughout the 1970’s, Army and Air Force helicopters sustained the Military Assistance to Safety and Traffic program (MAST). In the program’s nine years of existence, its helicopters have flown 36,000 hours, transporting patients, medical teams, and supplies. By mid-1979, twenty-eight MAST sites were providing communities in the United States with emergency services.

During the past year, the U.S. continued to negotiate with the Soviet Union on the subject of a comprehensive treaty to ban chemical warfare. Since 1977, the intent has been to reach an agreement which, while permitting each the most advanced technologies for protection against a chemical attack, would prohibit production, stockpiling, and retention of toxic weapons. Twelve negotiation sessions have failed to produce an agreement on the issues of declaration of stocks, verification, and entry-in-force. The U.S. continued to adhere to its long-standing “no first use” policy while maintaining a chemical warfare stockpile for deterrence and for retaliation, should deterrence fail.

The establishment of the Nuclear and Chemical Directorate on the Army staff, to oversee all nuclear and chemical matters, signaled an awareness of the impending threat of chemical warfare. Four chemical defense companies were activated for permanent duty with forces in Europe to improve the chemical defense posture.

[10]

|

Go to: |

|

|

Last updated 22 January 2004

|