Department of the Army Historical Summary: FY 1980

2

Operational Forces

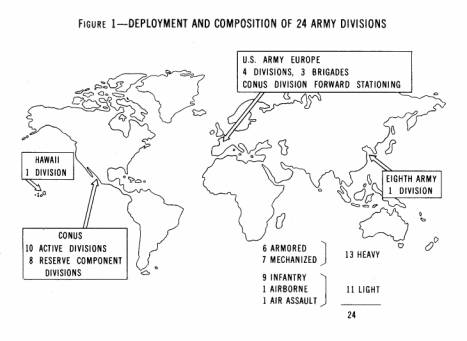

During the five previous fiscal years, the Army had activated three divisions and two separate brigades, converted a light division to mechanized, eliminated five major headquarters, and converted 50,000 support and overhead spaces to combat. This year the Army continued to mold its twenty-four divisions (sixteen active and eight reserve component) into the mix of heavy and light forces and sustaining structure most suited to meet NATO commitments as well as potential threats outside NATO. The deployment and composition of the force is indicated in figure 1, and the combat to support distribution of the force is shown in chart 1.

Fiscal year 1980 was marked by growing awareness of the Army’s need to develop a credible capability to deal with threats to U.S.

FIGURE 1—DEPLOYMENT AND COMPOSITION OF 24 ARMY DIVISIONS

[7]

CHART 1— DISTRIBUTION: COMBAT TO SUPPORT OF ARMY FORCE STRUCTURE

interests outside Europe while still retaining the capacity to meet NATO commitments. Recognition of the need for this new capability led to the organization, after many months of planning and discussion, of the Rapid Deployment Joint Task Force (RDJTF). Viewed by some as the lineal descendent of the old Strike Command, discontinued in 1972, the RDJTF grew out of a 1977 study highlighting the need for a multiservice force which could be deployed to areas outside NATO and Northeast Asia.

The Iranian revolution, the seizure of the American hostages in Tehran, and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan hastened the formation of the RDJTF. It was officially established on 11 March 1980 with Lt. Gen. Paul X. Kelly, USMC, as commander and headquarters in the former Strategic Air Command alert facility at MacDill Air Force Base, Florida. The RDJTF is primarily a headquarters which, when needed, would command various designated units of the four services, generally those not otherwise committed to NATO or Korea. No new forces have been added to the U.S. military structure as a result of its creation. The major Army units designated for the force are Headquarters, XVIII Airborne Corps; 82d Airborne

[8]

Division; 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault); 24th Infantry Division (Mechanized); 194th Armored Brigade; and various ranger units. The task force headquarters is a separate subordinate command of the U.S. Readiness Command (USREDCOM) but in the event of deployment the RDJTF commander would normally report directly to the National Command Authority through the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS).

The current focus for the RDJTF is the Middle East and Persian Gulf area and its mission is to plan, train, exercise, and prepare to deploy forces in response to contingencies threatening U.S. interests. It is not an invasion force, that is, a unit for forcible entry into a hostile country, but is structured mainly to assist nations of the Southwest Asia region in resisting aggression.

RDJTF planners estimate that the United States could have its first tactical air forces on the scene in the Middle East or Persian Gulf area within a few hours; a battalion on the ground within two days; and a brigade within one week. An airborne division could be lifted in about two weeks. The most optimistic estimate for seaborne movement of a division is thirty to thirty-five days. Whatever the deployment time, the effectiveness of the force will largely depend on the extent of logistic support provided by the “host nation” or lifted from U.S. bases.

The Army’s ability to meet its commitments, whether in NATO or as part of the RDJTF, depends largely on the ability of its units to meet their deployment schedules, deploy quickly, and sustain themselves once deployed. During fiscal year 1980, however, the readiness of major U.S. Army combat units declined. In December 1979, the Army rated six of its ten combat divisions in the Continental United States (CONUS) as in category C-4 (not combat ready). Two of the units so rated, the 101st Airborne and the 24th Infantry Divisions, were earmarked for the RDJTF.

Of the remaining four divisions, three were rated combat ready but with major deficiencies. These divisions had suffered most from failures to meet recruiting goals in 1979 and from the shortage of experienced NCOs in the combat arms specialty due to assignment to Europe and the Far East.

In a move to provide more accurate and timely information on the readiness of Army units, three significant changes were made in the unit status reporting system. The first was to base personnel calculations only on those individuals assigned to a unit who are available for immediate deployment. The second was to count any equipment not actually on hand as a deficiency in equipment readiness ratings, and the third was to establish a separate rating criteria for aircraft readiness.

[9]

To further bolster readiness, the Army Chief of Staff announced a series of changes to improve cohesion and stability in U. S. based units. These moves included an end to the policy of keeping Army units in Europe and Korea at between 102 and 105 percent of strength. This would allow the withdrawal of some 6,000 NCOs from Europe and 1,000 from Korea. These experienced NCOs will be assigned to stateside divisions to beef up the readiness and training capability of the divisions. The Chief of Staff also announced longer tours of command for battalion and brigade commanders and an increase in the length of basic training from eight to nine weeks with additional advanced training as appropriate.

At the same time, the Army continued to refine its mobilization planning and techniques. As currently envisioned, mobilization—that is, the process of calling to service, preparing, deploying, and supplying combat units—is an almost unbelievably complex task involving fifty-three different mobilization stations which must man, equip, train, and deploy more than 4,000 separate military units. The Army’s basic organizing program for mobilization is labeled CAPSTONE and involves the grouping of active, reserve, and National Guard units into preorganized packages each with a specific mission. For example, an Army Reserve engineer battalion might be packaged with a second Army Reserve engineer battalion, an Army National Guard engineer battalion, and an active engineer battalion to form an engineer group. All members of subordinate units in the engineer group would know in advance their wartime assignment, where to report for mobilization, and what other units would comprise their group.

To aid in mobilization under the CAPSTONE concept, Army Readiness Regions, which were responsible for the coordination and evaluation of reserve unit training, were given the additional mission of preparing for and coordinating mobilization planning for units in their region. Their names were changed to Army Readiness and Mobilization Regions (ARMRS).

Fiscal year 1980 also saw a continuation in the activation of military intelligence battalions (Combat Electronic Warfare Intelligence (CEWI)) to help the Army cope with the increasingly complex and sophisticated problems of electronic warfare. During the year, five divisional military intelligence battalions (CEWI), two in Europe and three in the United States, were activated; other divisions formed provisional CEWI type units in anticipation of formal activation as division commanders began to perceive the operational advantages of the CEWI concept. Meanwhile, the Army continued to study and test plans for a military intelligence group (CEWI), and tables of

[10]

organization and equipment (TOEs) were approved for four corps-level military intelligence groups (CEWI) to be activated in the future.

Aside from questions of readiness, the capability of the Army to quickly deploy its forces to Europe or elsewhere from CONUS was also increasingly called into question. A new U.S. transport aircraft able to carry heavy battle tanks over long distances and land on relatively short, primitive runways and fast cargo-carrying ships with the capability to unload in primitive ports were among the basic requirements for a successful overseas deployment in reasonable time, yet both systems remained in the design and budgeting stage.

The highest state of readiness among U.S. Army active forces in fiscal year 1980 was represented by the units composing U.S. Army Europe. In keeping with the concept of “US Army, Europe—an Army deployed,” the Army continued to take measures to assure USAREUR is combat prepared. The three main elements of the concept are to relieve USAREUR of many peacetime base support functions, to provide rehabilitated and modernized base facilities, and to acquire additional facilities as necessary.

Planning continued for a community-level pilot project at Karlsruhe, Germany, involving performance of basic base support functions such as transportation, housing, driver training, and food service by commercial contractors.

In the event of a Warsaw Pact attack, USAREUR’s forces and U.S. NATO allies intend to “fight outnumbered and win,” in the words of an Army field manual. That they will fight outnumbered was scarcely questioned during the fiscal year but winning was beginning to seem increasingly difficult in the face of the Warsaw Pact’s growing mobility, readiness, and strength and the loss of NATO’s edge in theater nuclear weapons.

For the sixth year in a row, U.S. Army forces participated in NATO readiness exercises with special attention given to exercise REFORGER 80 involving the deployment and redeployment of U.S. units to Europe. Units from CONUS participating in the exercises included elements of the 2d Armored Division, a battalion combat team of the 82d Airborne Division, a battalion of the 9th Infantry Division, the 2d Battalion, 34th Armor, and an 8-inch, self-propelled field artillery unit of the South Carolina Army National Guard as well as many other Army Reserve and National Guard units. A new element introduced in REFORGER 80 was the participa-

[11]

tion of U.S. units in a large-scale British field exercise, SPEARPOINT. An airborne battalion of the 82d Airborne Division from Fort Bragg was flown directly to Europe aboard C-141 aircraft and parachuted into the exercise area.

This fiscal year, the Eighth Army marked its 30th anniversary of service in Korea. North Korea continued to commit provocative acts. In May infiltrators fired upon 2d Infantry Division troops who were performing civil police duties for the United Nations Command in the Demilitarized Zone. Fortunately, there were no American casualties.

Redesignation of I Corps (ROK/US) Group as the Combined Field Army (ROK/US) became effective on 14 March 1980. This change gave recognition to the fact that the 185,000-member organization was a field army in size and mission.

In June, the 38th Air Defense Artillery Brigade completed the transfer of equipment from one of its Improved Hawk battalions to the South Koreans and inactivated the unit. Plans provide for transferring assets of two other of the brigade’s Improved Hawk battalions in the future.

Preparations moved forward during the year to replace the 105-mm. howitzer in two battalions of the 2d Infantry Division, and to replace the AH-1G helicopter with the AH-1S model in the division’s cavalry squadron. The new howitzers will nearly triple the range of direct support artillery and permit the use of an improved family of munitions. The AH-1S helicopter will fire the TOW missile and will significantly increase the division’s ability to knock out tanks. Also begun was the establishment of a military intelligence battalion (CEWI) in the division that will employ the most up-to-date equipment and procedures for near real-time battlefield intelligence.

During 1977, the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Logistics had successfully established a system for the accelerated delivery of selected repair parts to certain units by shipping them by air. Called the Air Line of Communications (ALOC), the system was successfully tested for use in the shipment of supplies to Korea in 1978 and 1979. A final evaluation of the Korean ALOC conducted at the end of 1979 by a joint Army-Air Force-Defense Logistics Agency team found that the system contributed significantly to improved logistical support for the Eighth Army. It was made permanent in February 1980 and in that same month the system was extended to units in Alaska and Hawaii.

[12]

The massive and unexpected influx of Cuban refugees into the United States, beginning in April 1980, resulted in a Presidential emergency declaration which designated the Federal Emergency Management Agency as the overall coordinator of government refugee operations. On May 3, the Secretary of the Army was designated Executive Agent for Department of Defense (DOD) activities in support of the Cuban refugees. That same day the first Cuban refugees began arriving at Eglin Air Force Base and Key West Naval Air Station, Florida. Between that date and September 30, over 43,700 refugees passed through DOD reception and processing centers at Fort Chaffee, Arkansas; Fort Indiantown Gap, Pennsylvania; and Fort McCoy, Wisconsin, at an estimated cost of almost 92 million dollars. The Army Medical Department established medical facilities at the refugee camps. About 10,000 refugees still remained at Fort Chaffee which had been selected as the consolidated facility for refugees.

As a result of damage in the Dominican Republic caused by Hurricane Allen in early September 1979, the Army dispatched helicopters, water purification units, and communications equipment from the 101st and 82d Airborne Divisions and the Puerto Rico National Guard. In October, the 193d Infantry Brigade provided medical teams, helicopters, vehicles, and communications equipment to alleviate suffering resulting from severe flooding in Nicaragua. Aid continued through February 1980.

As part of a major reorganization of the Army’s command and control structure, the first since 1973, all active Army divisions were grouped under three corps headquarters during the fiscal year. The object of the reshuffling was to reduce the number of units which report directly to U.S. Army Forces Command.

Under III Corps at Fort Hood, Texas, were placed the 1st Infantry Division (Mechanized), 5th Infantry Division (Mechanized), 1st Cavalry Division, 2d Armored Division, 3d Armored Division, 6th Cavalry Brigade, 11th Air Defense Artillery Group, and 13th Support Command. Under the XVIII Airborne Corps were the 24th Infantry Division, 197th Infantry Brigade, 194th Armored Brigade, 18th Field Artillery Brigade, 1st Support Command, and the 36th Engineer Group. Sometime in the future, the three divisions in the Far West— 4th Infantry Division, 7th Infantry Division, and 9th Infantry Division—will be grouped under an as yet undesignated corps. However,

[13]

due to shortage of personnel and funds, these three divisions will continue to report directly to U.S. Army Forces Command.

The reorganization into corps was one of a number of actions taken by the Army during the fiscal year as a result of the findings of a major Army Command and Control Study (ACCS-82) begun in September 1978 and completed at the end of 1979. In addition to the three corps plan, the study group also recommended assignment of a mobilization planning and execution mission to the Army Readiness and Mobilization Regions, a change completed by July 1980, and the transfer of basic policy-making responsibilities for mobilization from U.S. Army Forces Command to Headquarters, Department of the Army (HQDA), done in March 1980. Implementation of another recommended action, the assignment of full-time mobilization planners to major command and CONUS armies and mobilization stations, was also begun. The Army was also considering a plan for designating certain Army Reserve organizations to assume command of some Army installations in CONUS in the event of mobilization.

Since World War II, the United States has maintained a capability to conduct chemical warfare for much the same reason that it maintains a nuclear arsenal, that is, to deter attacks employing these types of weapons and to retaliate should deterrence fail. The production and stockpiling of chemical weapons is permitted under the 1925 Geneva protocol, which, in effect, is a “no first use” agreement rather than a complete prohibition of chemical warfare.

At the end of fiscal year 1980, the Soviet Union was estimated to have an edge over the United States of eleven to one in chemical personnel and four to one in chemical munitions. Unconfirmed but numerous and persistent reports on the use of chemical agents in Laos, Cambodia, and Afghanistan prompted the Army to take steps to upgrade its capabilities in the field of chemical warfare. The U.S. Army Chemical Warfare and NBC Defense Review Committee was established on 1 March 1980 to conduct semiannual reviews of the entire chemical warfare effort. Chemical units equipped to provide biological and chemical reconnaissance and decontamination support were added to divisions and selected nondivisional Army units in the United States and Europe. At the same time, the Army began a program to increase the level of nuclear, biological, and chemical warfare expertise in the Army. The U.S. Army Chemical School, which had closed its doors in 1972, was reestablished at Fort McClellan, Alabama, in December 1979. Also, over 3,600 chemical warfare specialists were scheduled to be added to active Army units

[14]

beginning in fiscal year 1980. Each company-size unit would receive an NCO chemical expert and each battalion a chemical officer with additional specialist officers assigned to training, doctrine, and materiel development commands. By the end of the fiscal year, almost 400 of these billets for chemical specialists had been filled, mostly in USAREUR.

While training of chemical warfare specialists went forward, research and continued development of chemical defensive equipment was accelerated. Perhaps the most critical activity was the development of a new protective mask. During October 1979, a special in-process review of the mask was conducted which resulted in a decision to proceed with development to obtain a prototype for testing. In February 1980, HQDA reserved approval authority for the development acceptance in-process review based upon the importance of the mask program. Another new item of protective equipment, the M51 Collective Protective Shelter, which provides protection for medical treatment of casualties in a toxic agent environment, was issued to Eighth Army and USAREUR.

In late 1979, a high level interagency review was held to assess the necessity for modernizing the U.S. chemical weapons stockpile. The review resulted in a recommendation to fund the initial phase of a munition production facility at Pine Bluff Arsenal, Arkansas. The facility would manufacture a 155-mm. nerve agent binary munition. Binary chemical munitions form a lethal chemical agent from nonlethal constituents by means of a chemical reaction occurring only during the flight of the weapon to the target.

The proposal to fund the binary manufacturing facility was supported by the JCS and DOD but funds for equipment were not included in the President’s fiscal year 1981 budget. Nevertheless, Congress authorized and appropriated funds for the initial construction phase of the binary munitions production facility.

In response to growing concern about the effects which U.S. atmospheric nuclear tests conducted between 1945 and 1962 may have had on the long-term health of participating servicemen, the Chief of Staff directed the Adjutant General’s Office to establish the Army Nuclear Test Personnel Review Program to identify all Army personnel who took part in atmospheric nuclear tests.

The program is administered by The Adjutant General with support by the Reserve Components Personnel and Administration Center (RCPAC), St. Louis, Missouri, and the United States Army Management Systems Support Agency, which provides computer facilities. The initial goal of the program is to identify all of the estimated 54,000 participants in the various tests. The task is complicated by the scarcity of records for personnel who left the service

[15]

prior to 1960. Approximately 85 percent of the records of these men and women were destroyed in a 1973 fire at the St. Louis Records Center. An attempt is under way to rebuild these records from other sources such as the FBI and the Veterans Administration. So far 50,000 of the estimated 54,000 individuals have been identified and an initial data base is expected to be completed early in fiscal year 1981.

Military Support to Civilian Authorities

As in other years, Army units were called upon to render a variety of services and support to civilian authorities from disaster relief to support of the Winter Olympic Games.

Except Cuban refugee relief activities noted earlier, demands on the Army for help in disasters and emergencies were relatively light during fiscal year 1980. In the wake of Hurricane Frederick, soldiers using Army landing craft provided ferry service between the mainland and the former resort center of Dauphin Island off the coast of Alabama, while other units provided helicopter support. In November 1979, the tiny atoll of Majuro in the Trust Territories of the Pacific Islands was flooded by wave action. Soldiers from Western Command (WESTCOM) moved in and provided medicine, food, and water purification services for several weeks. In the Far West, Army boatmen rescued cattle stranded by floods in the San Joaquin River Valley and provided communication and helicopter support during the volcanic eruption of Mount Saint Helens in Washington in May 1980. During a strike by New York City transit workers in April 1980, the Army provided 41 buses with drivers to maintain critical federal operations in the city.

The primary and presidential election campaign of 1980 brought requirements for Army support to protect the candidates. Specifically, the Army provided explosive ordnance disposal personnel to assist the U.S. Secret Service in over 1,700 bomb search missions throughout the United States.

For the 1980 Winter Olympic Games, the Army provided a wide variety of services ranging from the loan of cold weather field manuals to design, installation, and maintenance of complex communications systems. An average of 130 active Army personnel were on hand during the period of the games operating a radio communications net, acting as telex operators, assisting with medical service support, and operating a complete backup electric power system.

The backup system was soon put to the test when, on 19 February, a power failure in Lake Placid blacked out the broadcast center, the

[16]

focal point for all radio and television coverage of the games as well as the Mount Van Hoevenberg area where a number of events were in progress. Within four minutes the backup generators were providing power to those sites, enabling the games to continue without interruption.

To provide security for the Olympic Village, Army technicians installed an electronic physical security belt around the village site. The system was designed, installed, and maintained by the Army and operated by New York State Police personnel trained by the Army.

On 24 April, after 5 1/2 months of training and preparations under conditions of strict secrecy, Army personnel—along with personnel of the Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps—participated in an unsuccessful attempt to rescue Americans held hostage at the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, Iran, since early November 1979.

Preparations for the rescue attempt had begun as early as 4 November when a special joint task force was secretly established to plan and train for the mission. During December, January, and February, elements of the force trained together at a desert training site in the western United States. By the end of March, the joint task force elements had conducted a number of training exercises and was considered ready to undertake the mission on short notice.

Eight RR-53 helicopters carrying rescue mission personnel took off from the aircraft carrier Nimitz on the evening of 22-23 April for a 600-mile night flight to a refueling site in the Iranian desert called Desert One. One helicopter experienced mechanical difficulties with its rotor blade and was obliged to land in the desert approximately two hours after takeoff. The crew was picked up by another helicopter, which then attempted to continue on to the rendezvous. It soon encountered a hanging dust formation which, combined with instrument failure and time delay, caused the pilot to decide to return to the Nimitz. An hour later, the six helicopters remaining in formation also encountered unexpected dust, but arrived safely at the desert rendezvous where they were to be refueled by C-130s. One helicopter, however, suffered a partial hydraulic failure, which rendered it incapable of continuing on to the objective. Six helicopters had been determined by the commander of the joint task force and his planners to be the minimum necessary for continuation of the mission at that point. When the commander at Desert One advised the joint task force commander of the fact that only five operational helicopters remained, the latter, with the concurrence of the

[17]

President, ordered the mission aborted and the helicopters and C-130s withdrawn.

One helicopter, repositioning itself to permit another helicopter to top off its fuel tanks for the return flight, collided with a C-130 and both aircraft immediately burst into flames. Shortly thereafter, ammunition aboard the two burning aircraft began to explode, showering several other helicopters with shrapnel and rendering at least one unfit for flight. At this point, all personnel transferred to the C-130s and departed. Eight men were killed and five others injured in the collision of the helicopter and the C-130; all others returned safely to the Nimitz.

[18]

|

Go to: |

|

Last updated 17 September 2004 |