Army Ground Forces, Study No. 1

CHAPTER VIII:

GHQ AND THE DEFENSE COMMANDS IN THE CONTINENTAL UNITED STATES

In addition to all of its other functions, GHQ became involved in defense planning for the continental United States. Though this activity never became as urgent as its responsibility for certain overseas bases and never as important as the control it exercised over training, the ideas of GHQ on the military organization of the country’s defense were a definite factor in the plans developed up to March 1942. The recommendations of GHQ regarding defense planning were governed by General McNair’s fundamental belief in unity of command. The problems raised in applying this principle to the organization of defense commands in the continental United States as well as of those outside its limits brought to light the basic difficulties in carrying out the plans for GHQ as conceived by the Harbord Board twenty years before. The vast difference in the strategic situation of 1918 and 1941 was among the major causes leading to the dissolution of GHQ. This development was hastened by overlapping of planning and command responsibilities, the inability of the War Department to delegate full authority to GHQ, and the unsettled relationship between GHQ and the Army Air Forces in the organization for the defense of the United States established in March 1941.

The Role of GHQ in Planning the Defense of the United States

Before 3 July 1941, while still exclusively a training headquarters, GHQ had already made its influence felt in military planning. It participated in the separation of the field forces from the corps areas, an action which made possible the creation, apart from fixed administrative establishments, of large mobile armies for tactical employment in the field. These field forces were expected to become capable of offensive warfare. The War Department over-all strategic plan prescribed, as the primary task of the United States Army, the building of “large land and air forces for major offensive operations.”1

But in 1940 and 1941 offensive warfare, however desirable, seemed on sober calculation of means, a possibility only for the future. During most of this period, it was by no means certain that Great Britain could stand up under the blows with which the Luftwaffe was hammering her cities. A War Department G-2 conference in May 1941, attended by the G-2 of GHQ, attempted to estimate the military power which the United States could exert if the British should be defeated and came to the following conclusions:2

|

May-November 1941: |

An unbalanced force without combat aviation could be put into the field

in any area not within a thousand miles from the west coast of Europe

or Africa. |

|

November 1941-April 1942: |

A small force with combat aviation could be used. |

|

April-November 1942: |

Balanced forces would be available up to the limit of ship tonnage. |

|

After November 1942: |

Shipping, equipment, and training would permit an expeditionary force of 430,000 to be put into action. |

[65]

In these circumstances, the War Department had to consider above all the immediate defense of the continental United States. GHQ had no responsibility in the matter before 3 July 1941, but after that date it was responsible for the planning and after Pearl Harbor for the execution of measures to resist attack. Even before 3 July 1941, the advice of General McNair was sought and frequently accepted. Since attack was unlikely except by air, air officers played a leading part in defense planning. Indeed, they tended to feel that the problem was exclusively theirs and to attach slight importance to collaboration with ground troops in the repelling of invasion. Nevertheless plans for the air forces and plans for the defense of the United States became inextricably interwoven.

The Principle of Territorial Command Unity and the Air Problem

An Air Defense Command had existed since 26 February 1940, with headquarters at Mitchell Field, New York, under command of General James E. Chaney.3 It was a planning body, with authority to organize combined air-ground operations, but it had no territorial responsibility and no control over either aircraft or antiaircraft artillery except as they might be attached to it by the War Department. General Chaney repeatedly urged the organization of definite defense measures for the vital northeastern area of the United States.

In the discussions which came to a head late in 1940 General McNair was consulted. He favored the division of the continental United States into four regional defense commands. He wished to keep these distinct from the four field armies, which as mobile units might by moving away leave a region unprotected, and from the nine corps areas, which as fixed administrative organizations were not suited for combat. In each defense command, in his view, there should be unity of command over all elements of defense; pursuit aviation, antiaircraft artillery, mobile ground troops, harbor defenses, and the aircraft warning service. The area under a defense command, if invaded, would become a theater of operations and the defense commander would become theater commander with unified control over all military means in his theater.4

Fear that unity of command within a given area subject to attack might be lost caused General McNair to disapprove of certain features of reorganization of the Air Corps effected at this time. The Air Corps, in order to create an intermediate echelon between its seventeen wings and the headquarters of the GHQ Air Force, divided the United States into four air districts. General McNair, dubious at first, was brought to accept these territorial air districts for purposes of training and administration. The Air Corps, supported by G-3 of the War Department General Staff, then proposed the creation of a bombing command and of an air defense command within each air district, the former to conduct offensive operations, the latter defensive operations, “within the theater of the Air District.”5 General McNair concurred in the formation of these commands for the training and organization of mobile air units, but he demurred at the identification of air districts with theaters of operations. He maintained that, in the event of actual operations, the business of the air district was not itself to fight, but to supply appropriate bomber and pursuit aviation to the theater commander, who must be placed over air and ground forces alike and held responsible for operations as a whole.6

Creation of the Four Defense Commands

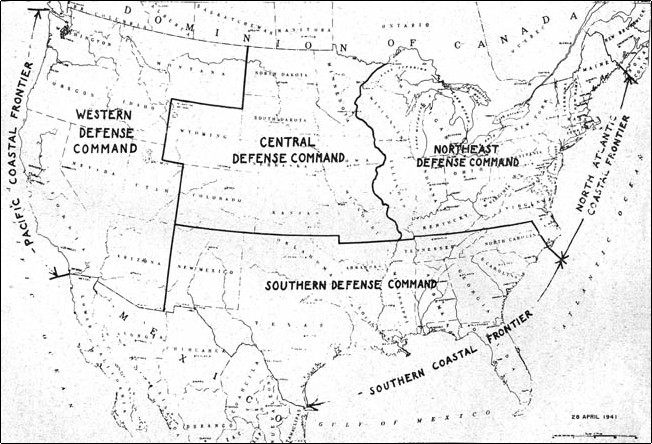

Action taken by the War Department in March 1941 embodied most, but not all, of General McNair’s ideas. A formal order of 17 March divided the United States into four Defense Commands—Northeastern, Central, Southern, and Western.7 Each defense

[66]

[67]

commander was to be responsible in peacetime for planning all measures against invasion of the area of his command. Should such invasion occur, he was to take charge of operations until otherwise directed by the War Department. To avoid accumulation of overhead, the commanding general of each of the four armies was designated as the commanding general of the defense command within which his headquarters was located, and the army staffs, with some reinforcement, were used as the staffs of the defense commands. GHQ was made responsible for the supervision and coordination of their planning, but not “until such time as the staff of GHQ has been expanded to undertake these additional responsibilities.”

The same order of 17 March replaced the four air districts with four air forces. To prevent confusion between territorial and mobile activities, against which General McNair as well as General Chaney of the Air Corps8 had warned, each air force was divided into a fixed and a mobile echelon. The fixed echelon would control bases, airdromes, aircraft warning services, etc. The mobile echelon would comprise a bomber command and an interceptor commend. “Interceptor Command” was the name now chosen for what the proposals of the preceding fall called “Air Defense Commands” and was in turn to yield to the name “Fighter Command” in 1942. Under whatever name, pursuit (i.e. fighter) planes were meant as distinguished from bombers.

The order of 17 March did not fully provide the regional unity of responsibility desired by General McNair. The four air forces stood directly under the GHQ Air Force. They were not subordinate to the defense commends and were only roughly coterminous with them.

For peacetime planning and preparation the distribution of authority was not clear. The principle of regional unity was recognized in the provision that the “planning for all measures of defense” in each area should rest with the commanding general of the defense command. But the conflicting principle of functional autonomy was recognized on the same page of the order, where responsibility for “the aviation and air defense portions of defense plans for Defense Commands” was conferred upon the commanding general of the GHQ Air Force. This provision was strengthened by additional instructions issued on 25 March, which directed that “current plans for organization of means of air defense will be transferred from the army commanders and other commanders to the commanding general, GHQ Air Force,” and that the latter should nominate his own representatives on local joint planning committees.9 In the geographical situation of the United States, with attack unlikely except by air, this was a considerable limitation on the planning powers of the regional defense commanders. The discrepancy was noted at once by General McNair as well as by others and led to prolonged discussion in the War Department. To General McNair it seemed “manifest that there must be a unified responsibility in peace for the preparation of war plans, even as there must be an undivided command within the defense command in war.”10

The question became even further entangled in the summer of 1941. By the directive of 3 July 1941, GHQ received authority to supervise the planning of commanders of defense commands. But in June the Army Air Forces had been established as an autonomous element in the War Department, and the GHQ Air Force, renamed the Air Force Combat Command and responsible only to the Chief of the Army Air Forces, had passed out from under such authority as GHQ had ever been able to exercise over it, carrying with it the power to make aviation plans for defense commands.11 Nevertheless General McNair continued his efforts to have planning authority transferred from the Army Air Forces to the regional commanders by whom, in case of attack, the plans would presumably be executed. On 15 August 1941 General McNair stated his position in full detail. He requested that the plans of the Air Forces for a theater should be submitted to GHQ, to be embodied, if approved, in a directive from GHQ to the theater commander; that local plans proposed by a theater commander should be transmitted through GHQ to the Chief of the Army Air Forces for approval or comment; and that, at the outbreak of

[68]

[69]

hostilities, GHQ would assume command of the air forces assigned to the theater and take the necessary action to obtain such air reinforcements as might be requested.12

Regional unity for war operations was provided for by the directive of 17 March. As construed by the War Department, this directive prescribed in case of war the attachment of an air force to its geographically corresponding defense command. The basic War Department strategic plan stated explicitly: “When the War Department, to meet an actual or threatened invasion, activates a Theater of Operations (or similar command) in the United States or contiguous territory for the combined employment of air forces and ground arms (other than antiaircraft artillery), the commander of the theater (or similar commander) will be responsible for all air defense measures in the theater.” This hypothetical situation became a reality with the declaration of war in the following December. The First Air Force was attached to the Northeastern Defense Command, which was now activated and renamed the Eastern Theater of Operations. The Fourth Air Force was attached to the Western Defense Command, which was in effect alerted as a theater of operations while retaining its old name. The Second and Third Air Forces, in the interior of the country, remained for training under the Air Force Combat Command. On the two coasts, the theater commanders obtained unity of command including aviation. The principle of unity, strongly advocated by General McNair, had been adopted for the potential combat zones.13

Coordination of Antiaircraft Weapons and Pursuit Aviation

Though in matters of higher command and planning General McNair sought to moderate the claims of the Air Forces, in the coordination of aviation and antiaircraft artillery he found himself trying to impose on the Air Forces more control of ground forces than they were willing to assume.

As early as May 1940, the Air Defense Command under General Chaney began to organize Southern New England into a Test Sector for a rehearsal of defense measures against air attack. The Test Sector exercise was executed in January 1941. Pursuit planes, coast artillery, regional filter boards, and the aircraft warning service, manned both by military personnel and by civilian volunteers, cooperated to resist an attack simulated by American bombers. Three observers from GHQ were present: the Air Officer, Colonel Lynd, and the two Coast Artillery officers, Lieutenant Colonels Milburn and Handwork.14

Colonel Lynd’s report to General McNair, dated 1 February 1941, concluded that the main lesson learned from the test was the need of putting antiaircraft defense under air command. This doctrine was accepted by GHQ and was incorporated in a War Department order of 7 March, assigning to the GHQ Air Force the responsibility for air defense in the Continental United States. Ten days later the order of 17 March, establishing an interceptor command within each of the four air forces, provided specifically that antiaircraft artillery, searchlights, and balloon barrages should be attached to interceptor commands during operations.15

Precisely how the interceptor commander, always an air officer, should exercise his control over these ground elements was a question admitting many different answers: There was agreement on the general aim. The interceptor commander must distribute local responsibilities for defense between ground elements and pursuit planes and, when both came into action in the same place, he must prevent his pursuit planes from being shot down by friendly artillery or entangled in friendly balloon barrages. Experience in England had shown that such mishaps were only too common.16 Tactical coordination required centralization of command and intelligence together with very rapid channels of command and communication.

[70]

As a result of experience in the Test Sector exercise, General Chaney recommended that the fire of all antiaircraft artillery be controlled by regional officers of the interceptor command, and G-3 of the War Department drew up a proposal to this effect. The Chief of Coast Artillery accepted the principle, but made an exception for combat zones, considering it impracticable to have antiaircraft batteries in the actual presence of enemy bombers await instructions from a regional officer.17 The question was taken up by the Air Defense Board created in April 1941 and composed of the Chief of Coast Artillery, the Chief Signal Officer, and the Commanding General of the GHQ Air Force, Lt. Gen. Delos C. Emmons. The Board agreed with the Chief of Coast Artillery, excepted combat zones from the terms of the War Department proposal, and suggested the appointment of an Antiaircraft Artillery officer on the staff of the interceptor commander.18

Reluctance of Air to Accept Command over Ground Forces

General McNair took issue with the findings of the Air Defense Board. On 9 July he pointed out that coordination of air defense was at least as necessary in combat zones as elsewhere, He insisted on unity of command over all air defense means. “It follows,” he said, “that organic corps and army antiaircraft units should be abolished. All such units should be assigned or attached to interceptor commands.” He recommended also that the proposed staff officer be replaced by an antiaircraft command officer, who should stand in relation to the interceptor commander somewhat as the commander of divisional artillery stood to the commanding general of a division.19

The issue between GHQ and the Air Forces was now reduced to two questions: (1) whether an interceptor commander should have all antiaircraft artillery in his area assigned, or attached to his command, and (2) whether he should exercise command over such artillery, or only “operational control.” The latter phrase, borrowed from the British, was favored by many officers in the Army Air Forces. On both questions General McNair insisted on the larger powers for the air commander.

During the following months the Air Force Combat Command, under General Emmons, acting for the Chief of the Army Air Forces, prepared a draft for a Basic Field Manual on “Air Defense,” which was submitted to GHQ for comment in October 1941. General McNair, in consultation with General Clark, Lieutenant Colonels Milburn and Handwork of the GHQ Coast Artillery Section, and Colonel Lynd, now liaison officer representing the Air Forces at GHQ, prepared comments which restated his basic views. He objected to the term “operational control” as uncertain in meaning and recommended the substitution of the word “command.” Moreover, he insisted that an interceptor command should include all antiaircraft weapons in the area and urged the creation of antiaircraft commands to be placed under interceptor commanders.20

These recommendations, dated 22 October and repeated in a memorandum of November, were eventually incorporated in training circulars published by the War Department. Training Circular No. 70, 16 December 1941, stated: “All antiaircraft artillery and pursuit aviation operating within the same area must be subject to the control of a single commander designated for the purpose.” Training Circular No. 71, 18 December 1941, repeated almost word for word General McNair’s language on the creation of antiaircraft commands under interceptor commanders and used the word “command” to, the exclusion of “operational control.”

The Air Forces were not satisfied. On 30 December General Emmons submitted to the Chief of the Army Air Forces an amended draft of the proposed Field Manual on Air Defense. Though General Emmons stated that all acceptable changes had been made, General McNair’s main criticisms had not been embodied.21 In view of this development General McNair renewed his objection to the term “operational control.” It is

[71]

“objectionable,” he wrote, “because it is unnecessary. The relation between the interceptor command and antiaircraft units operating in the same area is either command or cooperation. It cannot be something between these two.”22

In January 1942 Gen. C. W. Russell became Chief of the Air Support Section of the Air Forces Combat Command, which was located at GHQ. In his last post as Chief of Staff to General Emmons, he had signed most of General Emmons’ refusals to adopt General McNair’s recommendations, but he now came to agree with General McNair. “The term ‘operational control,’” he reported on 14 February 1942 to General McNair, “... is giving considerable difficulty. Action is required either to define the term explicitly or do away with it altogether and establish unity of command.”23

The Basic Field Manual on Air Defense, when finally published on 24 December 1942, embodied General McNair’s recommendations. The phrasing was less simple and clear-cut than that suggested by him, but “all” antiaircraft weapons were put under the “command” of the interceptor commander and no use was made of the term “operational control.”24

[72]

|

Last updated 18 February 2005

|