Department of the Army Historical Summary: FY 1989

3

Organization and Budget

Headquarters, Department of the Army

Having been elected in November 1988 to succeed President Ronald Reagan, President George Bush did not immediately select a new Secretary of the Army. The incumbent, the Honorable John O. Marsh, Jr., remained in office until a successor was sworn in. Marsh's tenure as Secretary, having begun in January 1981, was longer than that of any preceding Secretary of the Army or Secretary of War.

In late April 1989 President Bush nominated Richard Lee Armitage, then serving as the Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs, to replace Marsh. Citing personal reasons, Armitage withdrew his name from consideration a month later. President Bush subsequently nominated Michael P. W. Stone to be Secretary of the Army. Stone had served as Assistant Secretary of the Army (Financial Management) between May 1986 and May 1988, and as Under Secretary of the Army from May 1988 to May 1989. As Under Secretary he was also the Army Acquisition Executive. When nominated by Bush in July 1989, Stone was Acting Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, having been selected for that position by the new Secretary of Defense, Richard Cheney. Stone was sworn in as Secretary of the Army on 14 August 1989. The Army had been without an under secretary between May and September 1989, when the vacancy created by Stone's move to the Office of the Secretary of Defense was filled by John Shannon, who had served as Assistant Secretary of the Army for Installations and Logistics since 1984.

Stone served as Secretary of the Army for a little more than a month before the end of FY 1989. The reforms in the Army's acquisition process that he had initiated as Under Secretary continued to unfold. Important decisions regarding the formation of the military and civilian elements of the Army Acquisition Corps began to come up for Stone's review at the end of FY 1989. During his confirmation hearings, Stone articulated his vision of the Army. The service's "pressing needs," he told the Senate Armed Services Committee, "are to have a force immediately ready for war . . . with sufficient stores for a long fight." He stressed the importance

of proper modern equipment, adequate battlefield sustainment, continued emphasis on recruiting high-quality soldiers, and rigorous, realistic training. With Congress, he shared concern about some readiness problems in the reserve components and pledged to enhance Army special operations forces. Stone also called for the continued modernization of heavy forces because of the Soviet Union's modernization of its armored forces and emphasized the priorities needed for both ammunition procurement and weapons systems. If budget reductions demanded retrenchment, Stone indicated he would minimize the effect on force structure, continue to modernize but at a reduced pace, and maintain both force readiness and essential sustenance.

Stone's views were similar to those espoused throughout FY 1989 by the Army's senior military leaders. During FY 1989 the service's senior military leadership was characterized by more continuity. Chief of Staff General Vuono, who assumed that office on 23 June 1987, served as chief throughout FY 1989. Foremost among the personnel changes in key Army Staff positions during FY 1989 was the appointment of a new Vice Chief of Staff. Effective 17 January 1989, Lt. Gen. Robert W. RisCassi, formerly Director of the Joint Staff, became Vice Chief of Staff, U.S. Army, succeeding General Arthur E. Brown, Jr., who retired after serving in that position since June 1987. General RisCassi's background included recent participation in the development of Army doctrine and design of the new light infantry division concept.

Major organizational elements of Headquarters, Department of the Army, in FY 1989 are depicted in the table in the appendix. During FY 1987 and FY 1988, as mandated by Title V of the Department of Defense Reorganization Act of 1986, the Army Secretariat had assumed added responsibilities for acquisition, research and development, auditing, comptroller functions (including financial management), information management, and inspector general duties within the Army. In accord with Title V of the 1986 act, the Army also continued to reduce its administrative and headquarters staffs. Effective FY 1989, Congress limited the strength of the Secretariat and the Army Staff to 3,105 military personnel and civilian employees.

By FY 1989 the pace of organizational change spurred by the 1986 act abated within the Army Secretariat, but FY 1989 saw continued centralization of civilian management of the functional areas noted above. The Under Secretary, who was also the Army Acquisition Executive, adjusted the acquisition chain of command during FY 1989 by consolidating and eliminating subordinate program executive officers. To facilitate the developmental and acquisition process, a new staff group, the Army Test and Evaluation Management Agency (TEMA), was established on 1 November 1988 as a staff support agency assigned to the Office of the

30

Chief of Staff, with operational control exercised by the Deputy Under Secretary

of the Army (Operations Research). As the single point of contact at HQDA

for test and evaluation (T&E) matters, TEMA coordinated Army T&E policy

and resource actions with the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense

(OASD) (Research, Development, and Acquisition), the Army Staff, and the other

Army agencies and armed services, and developed and monitored major range

and test facility funding policies.

The US Army Financial Management Systems Integration Agency, located in Washington, D.C., was established as a staff support agency of the Financial Management Systems Directorate, effective 31 March 1989. As of 15 February 1989, the US Army Information Systems Selection and Acquisition Activity, Alexandria, Virginia, was redesignated as the US Army Information Systems Selection and Acquisition Agency and assigned as a field operating agency of the Director of Information Systems for Command, Control, Communications, and Computers. The agency continued to rely on the Commander, US Army Information Systems Command, for administrative and logistic support until FY 1990.

Continuing the realignment of the organization and functions of The Adjutant General's Office, the Adjutant General Center was disestablished as a field operating agency under the jurisdiction of The Adjutant General at the start of FY 1989. Its organizational elements and functions were realigned to other Army activities, principally the Total Army Personnel Agency. The Headquarters, Armed Forces Courier Service, a derivative unit of the Adjutant General Center, was disestablished and transferred to the Defense Courier Service as a joint service and DOD activity under the command and control of the Commander in Chief, Military Airlift Command, US Air Force. The Administrative Assistant to the Secretary of the Army assumed financial and administrative duties formerly carried out by The Adjutant General.

In addition, effective 1 October 1988, in accord with the US Total Army Personnel Agency (USTAPA) concept plan, the US Army Civilian Personnel Center (CIVPERCEN), formerly a field operating agency of the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Personnel (ODCSPER), HQDA, was incorporated into USTAPA as a separate directorate. USTAPA, a provisional field operating agency of ODCSPER since FY 1988, was redesignated the US Total Army Personnel Command (PERSCOM), effective 8 December 1988. PERSCOM remained a field operating agency of ODCSPER and retained proponency for the following elements: US Army Central Personnel Clearance Facility, Fort Meade, Maryland; US Army Central Identification Laboratory, Hawaii; US Army Enlistment Eligibility Activity, St. Louis, Missouri; US Army Enlisted Records and Evaluation Center, Fort Benjamin Harrison, Indiana; six US Army Personnel Assistance Points at entry and debarkation sites at Charleston

31

(South Carolina), John F. Kennedy Airport (Jamaica, New York) , Philadelphia International Airport (Pennsylvania), Seattle (Washington), St. Louis (Missouri), and Dulles International Airport (Herndon, Virginia); US Army Mortuary, Oakland, California; US Army Drug and Alcohol Operations Activity, Falls Church, Virginia; Personnel Security Screening Points at Fort Leonard Wood (Missouri), Fort Jackson (South Carolina), and Fort Dix (New Jersey); US Army Physical Disability Agency, Walter Reed Army Medical Center, Washington, DC, and its subordinate Physical Evaluation Boards; Office of Promotions Reserve Component and the Reserve Appointments Branch, located at P E R S C O M 's headquarters; and the Institute of Heraldry, Cameron Station, Alexandria, Virginia.

In a change of Army Staff proponency, the US Army Center of Military History (CMH), a field operating agency of the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations and Plans (ODCSOPS), was redesignated a field operating agency of HQDA on 1 March 1989, with proponency resting in the Management Directorate of the Director of the Army Staff (DAS), Office of the Chief of Staff, Army. The DAs shares some administrative functions regarding CMH with the Office of the Administrative Assistant to the Secretary of the Army.

During FY 1989 the Redistribution of Base Operating Information System (BASOPS)/Unit Structure Within TDA (ROBUST) Task Force completed its review of the Army's Table of Distribution and Allowances (TDA) structure of more than 600,000 spaces and nearly 3,000 units. Established in 1988, the task force had a goal to recommend a TDA structure best suited to complement the force design of Tables of Organization and Equipment (TOE) organizations adopted under the Army of Excellence program. The task force was also motivated by the need to scale down the strength of TDA organizations to protect combat force structure. Although submitted to the Army leadership early in FY 1989, the ROBUST Task Force's recommendations continued to be reviewed throughout the year.

Major Army Commands and the Unified Commands

Major Army Commands (MACOM) are also depicted in the table in the appendix. During FY 1989 changes occurred in several MACOMs One source of change was the Army's increasing involvement with environmental issues and compliance with state and federal laws. This workload had increased dramatically in recent years as the Army exerted itself to comply with tougher standards, to contend with lengthy litigation, and to overcome adverse publicity. In some instances environmental concerns had curtailed missions. To meet better its growing environmental respon-

32

sibilities and to streamline environmental management, the Army Environmental Office became an HQDA staff support agency under the Office of the Assistant Chief of Engineers, effective 1 October 1988.

At the same time, the US Army Toxic and Hazardous Materials Agency (USATHAMA) was transferred from the Army Materiel Command (AMC) to the US Army Corps of Engineers. The Chief of Engineers, as the environmentalist of the Army, delegated execution authority to the Assistant Chief of Engineers (ACE). USATHAMA, a field operating agency under the ACE, is responsible for centralized environmental support of the worldwide Total Army Environmental Program. To carry out its mission, USATHAMA can exploit the substantial environmental talent available through the Corps of Engineers' civil works missions in its districts and divisions. To enhance support to installation commanders in the environmental area, USATHAMA's mission expanded to encompass environmental restoration, which included the assessment and cleanup of hazardous waste disposal sites, regulatory compliance, hazardous waste reduction/minimization (HAZMIN), environmental training and awareness, and environmental technology development in support of installation restoration programs and pollution abatement.

Several organizational changes occurred in the Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) in FY 1989. On 14 July 1989 TRADOC inactivated the US Army Training Board. Established in 1971 as an Army "think tank" devoted to training issues, it was inactivated as a result of funding cuts and reorganizations of TRADOC's training functions. Over the years many of the board's activities began to duplicate other TRADOC training activities- the Combined Arms Training Activity, the Center for Army Lessons Learned, and the combat training centers. During FY 1989 TRADOC began reorganizing its subordinate test and evaluation structure, while it concomitantly planned to realign the Army's entire test and evaluation community. The Army sought to consolidate test and evaluation activities under two centers-one for technical and the other for operational T&E. In a realignment completed in early FY 1989, TRADOC gave primary responsibility for T&E functions to the Commander, TRADOC Combined Arms Test Activity (TCATA), at Fort Hood, Texas. It entailed a realignment of TCATA, the Combat Developments Experimentation Center (CDEC), and eight TRADOC test boards under the Test and Experimentation Command (TEXCOM). Concurrent with this realignment, TEXCOM became a major subordinate command of TRADOC.

On 18 July 1989, soon after TEXCOM was reorganized, the Deputy Under Secretary of the Army (Operations Research) asked for a review of the Army 's entire test and evaluation organization. He aimed to consolidate all T&E activities under one command. Three major issues were involved in the review: the consolidation of Army test and evaluation organizations;

33

the consolidation of Army analytic organizations; and the transfer of certain Army test centers to government-owned, contractor operated status. Of the several alternatives presented, Chief of Staff General Vuono selected a plan recommended by TRADOC and the Operational Test and Evaluation Agency (OTEA). The plan envisioned consolidation of several technical test and evaluation elements under AMC. These elements included the Army Materiel Systems Analysis Agency (AMSAA); the Test and E valuation Command (TECOM); technical test and evaluation functions associated with the U.S. Army Aviation Systems Command's Army Engineering Flight Activity, the US Army Missile Command's Test and E valuation Directorate, and the Atmospheric Science Laboratory 's meteorology teams; and certain functions of the US Army Armament , Munitions, and Chemical Command and the US Army Communications and Electronics Command. Under the reorganization, the entire Integrated Logistic Support (ILS) Division of the Logistics Evaluation Agency (LEA) would be transferred to AMSAA. The proposed command was tentatively designated as the Army Technical Test and Evaluation Command. Assigned to AMC, it would report directly to the Chief of Staff .

Operational test and evaluation, in turn, would be centralized under a newly created Operational Test and Evaluation Command (OTECOM) consisting of the US Army Operational Test and Evaluation Agency and the US Army Test and Experimentation Command. This arrangement, while it reduced personnel spaces, saved money, and streamlined operations, also responded to Congress' desire to separate technical T&E, which focused on engineering design and item performance, from operational T&E, which determined the operational effectiveness and suitability of weapons and equipment under development.

The proposed realignment was not approved during FY 1989. A general officer steering committee was chartered by the Vice Chief of Staff and the Deputy Under Secretary of the Army (Operations Research) to manage and implement the reorganization. Tentative plans envisioned a technological test and evaluation center in the Washington, D.C., area and an operational test center at Fort Hood, Texas. The latter would include the TEXCOM Experimentation Center (TEC) at Fort Ord, California; the Airborne and Special Operations Test Board at Fort Bragg, North Carolina; the Air Defense Artillery Board at Fort Bliss, Texas; and several liaison elements at various locations that would replace seven test boards (Arm o r, Engineer, Aviation, Communications-Electronics, Field Artillery, Infantry, and Intelligence and Security). Army planners believed this alignment would reduce intraservice conflicts between T & E organizations and save the Army more than $300 million between FY 1991 and FY 1995. Others considered that the proposed organization would reduce the Army 's testing capacity, particularly by eliminating an

34

immediately responsive branch test capability through the abolition of the seven boards.

Also under TRADOC's jurisdiction, the command structure at Fort Lee, Virginia, was reorganized in FY 1989. Command of Fort Lee was transferred from the Quartermaster Center, a major general billet, to the Commanding General, US Army Logistics Center, a lieutenant general billet, on 3 January 1989. The Logistics Center's mission did not change except for the additional responsibility for garrison operations. This change made Fort Lee's command structure parallel to Fort Leavenworth's, where the Commander of the Combined Arms Center was also the Commandant of the Command and General Staff College and the installation commander.

Plans to realign or close selected bases in the United States affected several TRADOC installations. The proposed closure of Fort Dix, New Jersey, a major training base, led TRADOC to study a realignment of the Army's entire training base. The possible closure of Fort Ord, California, increased pressure to relocate Headquarters, TEXCOM, to Fort Hunter Liggett, California, where the command had its mission elements. This move was delayed during FY 1989 pending the review and approval of an environmental impact statement and by other factors.

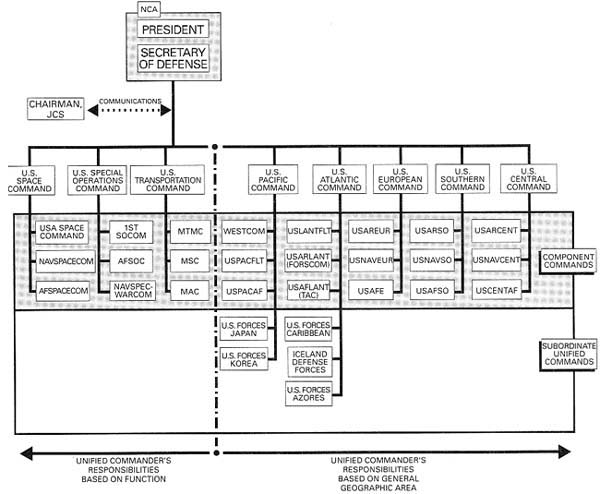

Chart 1 illustrates the relationships among Army MACOMs and the unified and specified commands subordinate to the national command authority in FY 1989. Army MACOMs constitute Army component commands in several unified commands and in certain specified and subordinate unified commands. These MACOMs are the principal suppliers of ground combat power for the appropriate CINCs. US Forces Command (FORSCOM), as a CONUS MACOM, was responsible for the readiness of Army forces and, as required, provided forces in its role as a specified command. FORSCOM was also the Army component of the US Atlantic Command, provided the nucleus for the Army component of the US Central Command, and through its subordinate 1st Special Operations Command (1st SOCOM) provided the Army component of the US Special Operations Command (USSOCOM).

During FY 1989 extensive planning was done to convert the 1st SOCOM to an independent MACOM by FY 1990. These efforts were closely coordinated with USSOCOM, since the 1st SOCOM would continue as the Army component in USSOCOM. (See Chapter 5 for additional discussion of this matter.) Through a Joint Mission Analysis (JMA), USSOCOM had refined its special operations forces (SOF) in FY 1989 to achieve a proper balance of readiness, modernization, sustainability, and force structure for SOFs of all three services. Its primary missions were to provide combat-ready SOFs to reinforce other unified commands and to plan and conduct special operations when directed by higher authorities.

35