Chapter IX:

Project 80: The Hoelscher Committee Report

Of all Secretary McNamara's

study projects the one known as Project 80 entitled Study of the

Functions, Organization, and Procedures of the Department of the Army

was the most important for the Army. In substance, it took up the

question of functionalizing the technical services where previous

studies and reorganizations had left it.

As in the case of Project 100

Secretary McNamara assigned responsibility for this study to Cyrus R.

Vance, who appointed Solis S. Horwitz, the Director of Organizational

Planning and Management, to supervise the project directly under him.

They agreed and informed the new Secretary of the Army, Elvis J. Stahr,

Jr., that the Army would be allowed an opportunity to study and evaluate

its own organization and procedures. On the recommendation of the Chief

of Staff, General Decker, Secretary Stahr selected the Deputy

Comptroller of the Army, Leonard W. Hoelscher, as the project director

to work directly with Horwitz's office.1

Mr. Hoelscher brought to his

task greater knowledge, experience, familiarity, and professional

accomplishment in the area of Army administration, organization, and

management than anyone, civilian or military, associated with the Army's

previous reorganizations as far back as Secretary Root. He had come to

Washington in 1940 as a colleague and protégé of Luther Gulick and John

Millett from the Public Administration Service in Chicago where he had

been a specialist in municipal administration after a decade as city

planner and city manager of Fort Worth, Texas. He had joined the Bureau

of the Budget after its transfer to the Executive Office of the

President in 1940 as a consultant on the organization and management of

federal agencies. During the war he had as-

[316]

Mr. HOELSCHER

sisted the Army Air Forces in

its reorganization under the Marshall plan and later worked with General

Gates in developing the concept of program planning. He also assisted in

improving the War Department's manpower statistics through the Strength

Accounting and Reporting Office. After the war he became Chief of the

Management Improvement Branch of the Bureau of the Budget at a time when

it was actively seeking to rationalize the federal bureaucracy along

functional lines. From 1950 on, as Special Assistant to the Army

Comptroller, and from November 1952, as Deputy Comptroller, he was

actively involved in developing the Army's functional program and

command management systems, in attempting to secure the adoption of

modern cost-accounting systems, and in improving the Army's management

procedures generally. With General Decker he had also worked to develop

a mission-oriented Army budget. Over a period of twenty years he had

developed an unparalleled, intimate working knowledge of Army

organization and management and its problems both as a planner and as an

operator.2

The Deputy Secretary of Defense,

Roswell L. Gilpatric,

[317]

gave Mr. Hoelscher some broad,

informal instructions. He suggested. the study should first determine

what major changes had taken place in the defense environment since the

Army's last reorganization in 1955 and, second, outline what basic

considerations or standards the Army should meet in the light of these

changes. The study should then recommend changes required in the

functions, organization, and procedures of the Department of the Army to

meet these basic considerations.

The committee, Mr. Gilpatric

went on, should assume no further major changes in the National Security

Act of 1947 or in the Army's current assigned missions and functions to

train and support forces assigned to the unified and specified commands.

The Army's Chief of Staff would continue to be a member of the joint

Chiefs of Staff, and the assistant secretaries of defense would remain

advisers supposedly without operating responsibilities.3

Mr. Horwitz and his staff wanted

other areas investigated. A perennial question was whether the General

Staff should be involved in operations, how responsive it was to demands

from higher echelons, and what should be its relations to other Army

elements. Was CONARC necessary as a kind. of "second Department of

the Army?" Should the technical services be subordinated to a

"Service Command" or replaced by a "Research and

Development" or "Materiel Command?" Should the Army

continue to perform such "non-military" tasks as managing the

Panama Canal or the civil functions of the Corps of Engineers? 4

On the basis of these

instructions, assumptions, and questions Mr. Hoelscher drew up an

outline showing how he proposed to conduct the study. He recommended

that there be a project director with full executive authority to

conduct the study and make its final proposals, assisted by a Project

Advisory Committee and supported by a working staff divided into task

forces assigned to investigate particular areas, organizations, or

functions. General Decker approved this plan on 17 February and, as

already noted, appointed Mr. Hoelscher as Project Director.

[318]

He was to report periodically

through him to Mr. Stahr and through Mr. Horwitz's office to Mr. Vance

on his progress.5

Hoelscher had a small project

headquarters staff which organized the several task forces, co-ordinated

their activities, and helped prepare the final report. The Project

Advisory Committee consisted of representatives of the General Staff and

CONARC. The seven task forces, or study groups, were assigned to

investigate the Secretary of the Army's Office and the General and

Special Staffs and to evaluate the general management of the Army:

CONARC, including training and combat developments; Office of the Deputy

Chief of Staff for Logistics (ODCSLOG), the technical services and Army

logistics; Research and Development; personnel management; Reserve

Components; and the Army's nonmilitary functions. No action was ever

taken on the recommendations of the group studying Reserve functions,

and the study group on nonmilitary functions was never formed. Later

another study group was organized at the request of the Chief of Staff

to investigate Army aviation.6

Hoelscher considered the

selection of personnel so critical that he obtained special permission

from General Decker to examine the personnel files of qualified persons

rather than rely upon the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff for

Personnel's (ODCSPER) resumes, the usual procedure. Hoelscher was

looking particularly for people whose records indicated they had

inquiring, analytical minds and the kind of broad-gauged training at the

Army War College or the Command and General Staff School which

emphasized the Army as a whole rather than the interests of a particular

arm or service. For each task force he sought a combination of officers

and civilians with a general background, management analysts, and

functional specialists.

DCSPER sent him the records of

more than four hundred officers and civilians who met these

qualifications. Following two months of examining these records,

Hoelscher and his staff selected fifty officers and thirteen

civilians, exclusive of clerical

[319]

assistance. Most officers were

colonels, but two were general officers. Perhaps the most important was

Brig. Gen. Ralph E. Haines, assistant commander of the 2d Armored

Division, who was chief of the task force on logistics. He was an armor

officer who had spent nearly all of his career in military operations.

Hoelscher's headquarters staff came largely from the Comptroller's

Directorate of Management Analysis and were chosen for their knowledge

of this area and because they were available and would remain so after

completing the study to follow up the committee's work.7

Second to selecting properly

qualified personnel, Hoelscher stressed what he considered the proper

methods of analyzing the Army's problems rather than compulsively

drawing organization charts at the outset. As he saw it, this should be

the very last item on the agenda after methodical analysis. To a

management expert like Hoelscher, organization charts were a red herring

leading people away from the real problems, the methods and procedures

by which an organization conducted its affairs. If the management of the

Army was inefficient, merely redrawing organization charts would not

solve the problem. That was one lesson to be learned from studying

previous Army reorganizations.8

The study groups spent

considerable time assembling facts and analyzing them. They studied

nearly four hundred reports and conducted approximately six

hundred interviews. They

[320]

made sixty field trips including

a visit overseas to investigate the U.S. Army's European Command. By

June they began discussing the basic considerations or standards the

Army should meet. After defining these objectives they developed,

evaluated, and chose among alternative patterns of organization and

management.9

In investigating changes in the

defense environment since 1955, the study groups concluded that there

were two Paramount trends which affected the Army's operations. The

first was the observable trend toward assigning all combat forces to the

unified and specified commands, operating directly under the joint

Chiefs of Staff. As a result, in the future the role of the services

would be to organize, train, and supply these commands. Second was the

equally obvious trend toward centralizing control over most programs in

the Department of Defense. In these circumstances, the Secretary of the

Army had more and more become an extension of the Office of the

Secretary of Defense, instead of being a spokesman for Army interests

and objectives. Centralization was most apparent in the areas of

research and development, common supplies and services, and financial

management. The increasing cost and complexity of new weapons systems

had led to increasing emphasis on systems or project management which

cut across service lines. The new program packages required the

development of uniform management information and control systems

throughout the Department of Defense for purposes of budgeting and

accounting.

The study groups by mid-June had

settled on two dozen basic considerations for improving the Army's

performance in the areas of financial management, Army staff

co-ordination and control, personnel management, supervision and

co-ordination of training, control of combat developments, research and

development, management of the Army's logistic systems, and the Army's

relations with industry and academic life. The ultimate objective was an

Army capable of meeting the requirements of "cold, limited or

general war." 10

[321]

The committee began by pointing

out what Army reformers had been saying since World War II. In two world

wars the Army had had to change its organization, particularly its

supply system, after the outbreak of war. A properly organized Army

should be able to function in peace and war without such upheavals. A

further consideration was that another major war probably would not

allow the Army the luxury of reorganizing in the midst of combat.

Therefore, if any changes were necessary, they should be made now.11

The improvements recommended in

financial management had also been an Army objective for a decade: more

effective long-range planning and programing, integration of planning,

programing, and budgeting, and the development of programs and budgets

in terms of missions performed. The development of new weapons required

some form of project or systems management outside normal command

channels. The Army should integrate its various programs for review and

analysis and for measuring performance more effectively with less

emphasis on minor details and more on anticipating future developments.

The committee suggested also creating a single automatic data processing

authority to assist the Army staff in controlling, integrating, and

balancing its growing array of information systems..12

The committee's proposals for

improving Army staff coordination indicated the need for some

organizational readjustments. There was an apparent duplication of

effort between the Secretary of the Army's staff and the General Staff

which should be corrected. The Army staff should get out of operations.

"There is an inevitable conflict between staff and command

viewpoints," it said, indicting the technical service chiefs.

"Placing both staff and command responsibilities on a single

officer detracts from his capability to perform either job well."

If he were responsible for a particular segment of the Army under his

command, he could not see a problem from the viewpoint of the Army as a

whole.13

Personnel management had not

been the subject of previous general studies of Army organization. Here

the emphasis

[322]

was on the need to utilize

military personnel on the basis of their capabilities rather than their

branch of service. There should be broader career opportunities for both

military and civilian personnel. Referring to the technical services,

the report pointed out that the increasing complexity of weapons systems

made greater flexibility necessary in the assignment of people with

specialized talents. The major problem in training was that

responsibility was fragmented among too many agencies, including the

technical and administrative services. On Reserve matters the committee

suggested greater participation by CONARC in command, supervision, and

support of Reserve units along with an overhaul of the ROTC program. 14

The committee found

responsibility for combat developments similarly fragmented. Long-range

planning of new doctrinal concepts and materiel requirements was

inadequate. Essentially a planning function, combat developments

required an environment free from operating responsibilities and from

the conservative outlook of those who distrusted changes. The emphasis

in combat developments as in operations research, the committee said,

should be on the application of research and development techniques to

concrete military requirements. Research and development within the Army

required an environment that would attract qualified scientists,

engineers, and other professional experts.

The Army's logistics systems

still needed greater integration and co-ordination. Finally, the Army

should improve its relations with businessmen and professional

scientists who were impatient with its red tape and delay.15

Following agreement on these

twenty-three "Basic Considerations" the study groups discussed

alternative solutions, including alternative organizational patterns. By

the end of August general agreement was reached on most major issues.

During September the study groups wrote their reports, while Hoelscher

and his immediate staff drafted an over-all report and dealt with

criticisms made by senior members of the Army staff.

Hoelscher presented his

recommendations orally to Secretary Stahr, General Decker, and the

General Staff on 11

[323]

October and to the Deputy Chief

of Staff for Logistics, General Colglazier, and representatives of the

technical service chiefs two days later.16

The Army as a whole was

especially interested in the organizational changes the committee

proposed. The most drastic was its proposal to functionalize the

technical services. To perform the Army's major research, development,

production, and supply functions, the Hoelscher Committee recommended

creation of a Systems Development and Logistics Command, a concept

dating back at least to General Goethals in World War I. It recommended

transferring the training functions of the technical services to CONARC,

reorganized as a Force Development Command. Responsibility for military

personnel management, it said, should be transferred, with certain

exceptions, to a new Office of Personnel Operations (OPO) . In line with

this the committee recommended abolishing The Adjutant General's Office

with its personnel functions going to OPO and its administrative

functions reorganized under a new Chief of Administrative Services. An

entirely new functional command, the Combat Developments Agency, later

designated the Combat Developments Command (CDC), would assume

responsibilities for this program formerly fragmented among CONARC, the

technical services, and the Army staff.

The Hoelscher Committee and its

task force on Army headquarters (Group B) also proposed important

improvements in the organization and procedures of the Army staff. These

included the addition of a Director of the Army Staff under the Chief

and Vice Chief of Staff and splitting the Office of the Deputy Chief of

Staff for Military Operations (ODCSOPS) into two agencies, a Deputy

Chief of Staff for Strategy and International Affairs and one for Plans,

Programs, and Systems. It proposed to regroup the Army's special staff

agencies in order to reduce the number of separate organizations

reporting directly to the Chief of Staff. The technical services would

continue under different titles as staff agencies relieved of their

field commands. The Office of the Chief of Ordnance and the Chief

Chemical Officer would be abolished entirely. The proposed organization

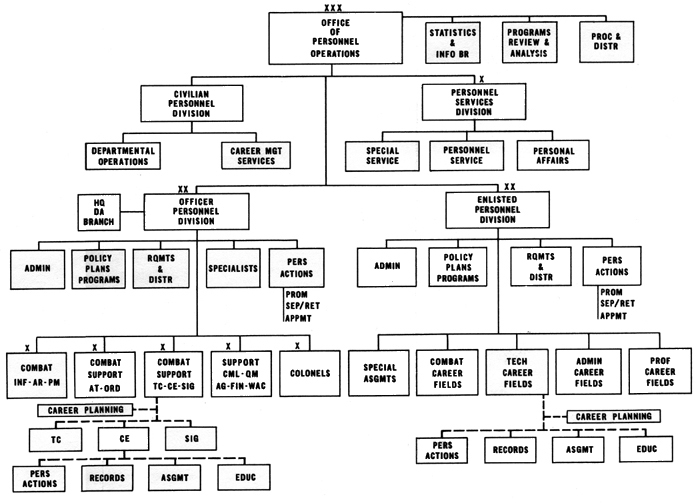

of Headquarters, Department of the Army, is outlined in Chart 25.

[324]

HOELSCHER COMMITTEE PROPOSAL FOR REORGANIZATION OF DEPARTMENT OF THE

ARMY HEADQUARTERS OCTOBER 1961

* Chief of Public Information also serves as Chief of Information.

1 General Staff Agency.

2 No change contemplated in status of Army Audit Agency.

Source: Hoelscher Committee Report, II, p.120.

[325]

A Director of the Army Staff,

the committee said, was necessary to co-ordinate the activities of the

General Staff for two reasons. Neither the Chief nor the Vice Chief of

Staff could perform this function effectively because they did not have

the time to devote to it. They were too busy with activities of the

joint Chiefs of Staff and other agencies outside the department. Second,

co-ordinating the activities of the General Staff had become a serious

problem in recent years, serious enough to justify such a position as a

full-time job. The increase in the size of Army staff agencies, their

expanding operations, and the frequent overlapping of their

jurisdictions created conflicts which the secretariat of the General

Staff could not resolve. Making the director senior to the deputy chiefs

would prevent many of these conflicts from reaching the overburdened

Chief and Vice Chief.17

In recommending splitting DCSOPS

into a Deputy Chief for Strategy and International Affairs and another

for Plans, Programs, and Systems, the committee asserted that DCSOPS

responsibilities for joint staff activities were so great that it did

not have time for its other assigned functions. Responsibility for

organization and training was fragmented among numerous Army staff

agencies. This required so much co-ordination that DCSOPS had little

time for policy planning. Joint staff activities and organization and

training were really two different functions that ought to be treated

separately.

The Deputy Chief of Staff for

Strategy and International Affairs would be responsible to OSD and JCS

for all joint staff activities and for international and civil affairs

concerning the Army. It would relieve the rest of the General Staff of

these functions and so eliminate some of the delay required to obtain

concurrences from many different agencies. As the Army's operations

deputy the DCSOPS would continue to run the Army War Room.18

The Deputy Chief of Staff for

Plans, Programs, and Systems would take over the other functions of

DCSOPS including organization and training, Army long-range planning,

combat developments, and Army aviation. This office would be respon-

[326]

sible for eliminating the gap

between plans, programs, and budgets. Creating a Systems (Management)

Directorate would provide for supervision of this new technique within

the Army staff.19

Financial management,

the

committee thought, could be improved by strengthening the authority of the

Comptroller, the Budget Officer of the Department of the Army, as an independent

review and analysis agency for the Army staff, and as the department's

Chief Management Engineer. It also recommended the adoption of

mission-oriented budget packages and improved review and analysis

procedures. It recommended that the Comptroller co-ordinate and integrate

the development of automatic data processing systems within the department

as well as systems analysis functions which relied heavily on the use of

automatic data processing.20

The Army staff was bogged down

in excessive co-ordination involving lengthy procedures of concurrences

and nonconcurrences.

Action officers complained they

must spend many hours seeking out those who may have an interest in a

particular problem-and then waiting long intervals for formal

concurrence from the other agencies. The system emphasized the formality

of concurrence as opposed to the substance of the problem. Partly by

custom, partly by the tradition of leaving no stone unturned to assure

that the staff action is complete, agencies having only minor interest

in a particular problem still must be shown as concurring formally

before the paper can be forwarded to the top officials of the

Department. 21

The committee proposed a system

of "active co-ordination" which would abolish the

time-consuming, traditional system of formal concurrences. The action

agency responsible for a particular project would be required to

determine and develop all the possible considerations, ramifications,

and consequences affecting its proposed solution, whether for or

against. It would submit alternative courses of action to

decision-makers along with the information needed on which to base their

decisions. This system would have the further advantage of reducing the

incentive to produce meaningless compromises for the sake of agreement.

[327]

Such a plan, while it resembled

the decision-making techniques of General Marshall and Secretary

McNamara, meant a radical break not only with traditional Army

procedures but those of the entire federal bureaucracy. In this sense

the proposal made by the Hoelscher Committee for active co-ordination

was far more revolutionary and radical than the more publicized

organizational changes it recommended.22

The task force which

investigated CONARC's training and combat developments program found

that the greatest weakness was fragmentation of responsibility for these

two functions among too many agencies. The situation was bad in regard

to training. It was even worse in the area of combat developments. The

independent technical services were major obstacles to effective

integration of these programs, but too many Army staff agencies were

involved as well. They complicated matters further not only by causing

additional delay, but their deliberations and compromises also made it

difficult to obtain clear policy decisions and instructions.

A particular weakness of the

combat developments program was the failure to develop any adequate

long-range planning, a natural consequence of mixing responsibility for

planning with operations at all levels in the Army.23

The CONARC task force

recommended integrating training. (Chart 26) CONARC would become a Force

Development Command responsible for induction and processing (functions

of The Adjutant General's Office), individual military training, the

organization, training, and equipment of units for assignment to

operating forces, and for supporting them and designated Reserve units

at required levels of mobilization or readiness. The Force Development

Command would also take over CONARC responsibilities for the CONUS

armies.

If individual training remained

a function of the Force Development Command's headquarters, it would

have to compete for attention with unit training and installation

support functions. Transferring to the Force Development Command the

schools and training centers of the technical and administra-

[328]

HOELSCHER COMMITTEE

PROPOSAL FOR REORGANIZATION OF CONARC, OCTOBER 1961

Source: Hoelscher Committee Report

tive services would add further

responsibilities to an overburdened headquarters.

A separate but subordinate

Individual Training Command could concentrate singlemindedly on

integrating the Army's individual training activities. It would also

supervise the Army's service schools, training centers, and personnel

processing activities. Specifically exempted because of their special

nature would be West Point and its Preparatory School, the Army War

College, certain intelligence schools, the Army Logistics Management

Center, and "courses of instruction of a professional medical or

non-military character." 24

The task force, in discussing

problems of installation support under the Force Development Command,

emphatically rejected any resurrection of the housekeeping command

concept that had caused so much trouble before the CONARC reorganization

of. 1955. The chief problem remaining in this area was financial

management. Installation support funds came under the amorphous,

catchall category designated "Operations and Maintenance of

Facilities." There was no such category in

[329]

the Army's appropriations

structure. Most of the funds to support installations came not only from

the Operations and Maintenance budget but also from the Operating

Forces, Training Activities, and Central Supply Activities

appropriations. Here again Congressional limitations on transferring

funds from one appropriations category to another were the principal

cause of the trouble and led to illegal transfers among appropriations

categories, as indicated earlier. The task force recommended making

Operations and Maintenance of Facilities a separate and legally distinct

category as the most efficient way of solving these problems.25

In recommending the integration

of combat developments under a single agency the CONARC task force

followed recommendations made by Project VISTA in 1952, the Haworth

Committee in 1954, and the Armour Research Foundation in 1959. In its

analysis, the task force suggested that four separate functions or

stages were involved: long-range planning, the development of materiel,

combat arms testing, and implementation, meaning the incorporation of

new doctrines and weapons in military training. The combat developments

agency proposed would cover only the first or planning stage. The CONARC

task force suggested assigning development and user acceptance tests to

the proposed logistics command, while training and doctrine would remain

under the Force Development Command. The "Combat Developments

Agency" would be responsible for preparing detailed military

specifications for new weapons and equipment, for developing new

organizational and operational concepts and doctrines, for testing these

ideas experimentally in war games and in field maneuvers, for conducting

combat operations research studies, and for analyzing the results in

terms of cost-effectiveness. The proposed agency would include all such

functions and personnel currently located at USCONARC headquarters and

its school commands as well as in the technical and administrative

services, the Army staff (principally the Office of the Assistant Chief

of Staff for Intelligence and DCSLOG), and the Army

[330]

HOELSCHER COMMITTEE PROPOSAL FOR A COMBAT DEVELOPMENTS AGENCY, OCTOBER

1961

Source: Hoelscher Committee Report, III, p.87.

War College. (Chart 27) Under

its command would be the Office of Special Weapons Development at Fort

Bliss, Texas, concerned with tactical nuclear operations, and the Combat

Developments Experimentation Center at Fort Ord, California. Combining

these elements in a separate Department of the Army staff agency,

designated as such rather than as a field command, was suggested as the

best means of emphasizing that its function was planning as distinct

from current operations. "This agency would emphasize creative

activity requiring imagination and the ability to focus on the future.

It would be a challenger of current doctrine and an innovator of new

concepts, which, in turn, demand new hardware."26

The most important Project 80

task force was the one under General Haines responsible for studying

DCSLOG, the technical services, and Army logistics in general. The

central issue, as in previous reorganizations, was how to assert

effective executive control over the operations of the services. The

services themselves had continued to deny the need for controls limiting

their traditional freedom of action either through placing them under a

logistics command or by breaking them up along functional lines. The

Palmer reorganization of 1955 which tried to place them under the

"command" of DCSLOG simply had not worked. DCSLOG had never

been able to assert effective control over them because it had to share

this authority with the rest of the Army staff. In 1961 they remained

seven organizationally autonomous commands. They employed nearly 300,000

military and civilian personnel at approximately four hundred

installations inside the United States with an estimated real estate

value of $11 billion and a current annual budget of $10 billion.

General Haines' task force

initially identified thirteen problem areas requiring detailed

investigation. Approximately half involved DCSLOG and the Army's

logistics systems only. The rest involved other Army staff agencies,

including personnel management, training, and intelligence.27

Another

important task was to conduct interviews and obtain the opinions of a

broad spectrum of individuals inside and outside the Army.

[331]

One was the new Assistant

Secretary of Defense for Installations and Logistics, Thomas D. Morris,

a career civil servant with intimate knowledge of financial management

and logistics. His deputy, Paul Riley, who had worked on logistics

management problems in the Department of Defense since 1958 was another.

Both criticized the Army for excessive delay in making decisions. They

also felt that while the Air Force and Navy came up with firm,

long-range logistics programs the Army generally presented only one-year

projections which merely summarized the technical services annual

programs. Dr. Richard S. Morse, the new Assistant Secretary of the Army

for Research and Development, asserted the Army must cut red tape and

make decisions more promptly. All three thought the independence and

conservatism of the technical services caused most of these problems.28

After investigating the thirteen

logistics problem areas General Haines' group concluded by making a

number of recommendations, many of which had been made before. Effective

management of Army logistics, it said, required that the Army staff

should confine itself to planning and policy-making and divorce itself

from the details of administration. The Office of the Deputy Chief of

Staff for Logistics, the principal offender, was so involved in

overseeing administrative operations that it neglected its planning

functions. It could not function effectively as commander of the

technical services because of the concurrent jurisdiction exercised by

other Army staff agencies over the technical services. Second, below the

Army staff there should be "positive, authoritative control over

the wholesale Army logistic system." Third, both in the Army staff

and in the field, development and production must be closely related.

Fourth, the argument of commodity versus functional organization

oversimplified the problem. Whatever logistics system was adopted, both

elements would have to be present at one level or another. The principal

aim should be to eliminate the duplication, unnecessary staff-layering,

and rigid compartmentalization of the existing. system. Such an

organization should also be adaptable to "systems management"

which cut across

[332]

traditional command lines.

Finally, the Army must overcome the "divisive influence"

caused by the relative autonomy and self-sufficiency of the technical

services.29

The whole Hoelscher Committee

generally agreed that the technical services should be functionalized.

It agreed that the General Staff should get out of operations and that

training, combat developments, and personnel functions within the Army

logistics system could be more effectively performed if these functions

were transferred to the proposed Force Development Command, Combat

Developments Agency, and the Office of Personnel Operations. Other

Army-wide services of the technical services could be transferred to

special staff agencies without harming the Army's logistics system.30

The logistics task force

considered three alternative organizational patterns for managing Army

logistics. The first involved two functional field commands, one for

research, development, and initial production and a second, the Army

Supply and Distribution Command, for the later phases of the materiel

cycle. The second alternative was to create two commodity commands, one

for military hardware, including all major weapons systems, and another

for general supplies and equipment, many of which were under single

managerships. Finally, the task force considered setting up a single

Systems and Materiel Command responsible for the entire spectrum of

supply from research and development through distribution and

maintenance.

The Haines task force and the

Hoelscher Committee, except the task force considering research and

development, believed that two separate functional commands would create

complex problems of co-ordination in addition to splitting the materiel

cycle. Two separate commodity commands would deal with research and

development and with distribution. Here, the likely transfer of the

single manager agencies to the newly created Defense Supply Agency made

it questionable whether a separate supply command was really necessary.

Conse-

[333]

quently they preferred a single

"Systems and Materiel Command." 31

The research and development

task force protested that such a command would subordinate research and

development to production and operations. World War II demonstrated that

successful research and development resulted from a separation of

research and development from supply activities, while industrial

production and military supply were not adversely affected to a material

degree by such a separation. "Furthermore, historical events reveal

the suppressive effect of the prevailing social order on innovating

activities, which on that account must be removed from the control of

day-to-day operations for maximum results." As an alternative this

group preferred an organizational pattern in which research and

development was separated from other supply functions. The pattern

proposed by General Haines' group, they believed, was worse than the

existing organization. They also wanted to strengthen the role of

research and development at the Army staff level by reverting to a

three-deputy chiefs of staff concept, one for joint plans, another for

operations and readiness, and a third for Army programs and resources.32

The Hoelscher Committee replied

by pointing out that the Army's research and development program would

continue to be headed by an Assistant Secretary for Research and

Development and on the General Staff by the Chief of Research and

Development. Important elements of the Army's research and development

program would be under the new Combat Developments Agency. The Haines

group added that under its proposed organization the new Systems and

Materiel Command would place sufficient emphasis on research and

development by appointment of a Chief Scientist as adviser to the

commanding general, a Director for Research and Development, and by

providing a special office for Project Management.

The overriding reason that the

Hoelscher Committee and General Haines' logistics task force selected a

single logistics command was that they considered it both unwise and

impractical to separate research and development from production because

of the need for close co-ordination between these func-

[334]

HOELSCHER COMMITTEE PROPOSAL FOR A LOGISTICS COMMAND, OCTOBER 1961

Source: Hoelscher Committee Report, IV, p.72.

tions at the operating level. To

confirm this opinion, Hoelscher conducted additional interviews with

logistics management experts and made special field trips in August to

several technical service industrial installations.

The basic organization proposed

for the Systems and Materiel Command, later to be called the Army

Materiel Command (AMC), consisted of a headquarters with three

functional directorates for research and development, production and

procurement, and supply and maintenance plus a supporting staff. (Chart

28) The Haines task force had deliberately placed Project Management,

Plans and Programs, and a Chief Scientist inside the office of the

commanding general to emphasize the importance and priority of these

functions. The principal field agencies were a series of

commodity-oriented development and production commands similar to the

existing Ordnance Department's field agencies and a functional supply

command responsible for both transportation and distribution.33

The Personnel Management report

was a unique feature of Project 80 because previous Army organization

studies had paid little attention to this subject. They had said little

beyond asserting that in any functional reorganization the technical

services should lose their personnel as well as other nonlogistical

functions.

The Personnel Management task

force asserted that responsibility for this function continued to be

fragmented among twenty different agencies on the basis of historical

accident rather than rational design. There had been little improvement

since 1945 when Drs. Learned and Smith had complained: "No single

agency in the War Department General Staff has adequate responsibility

or authority to make an integrated Army-wide personnel system

work."

The mixture of staff and

operating responsibilities within these agencies made integrated control

even more difficult. The agencies primarily responsible for personnel

management were DCSPER, The Adjutant General's Office (TAGO), and the

technical services. But nearly all other Army staff agencies were

involved, and all combined staff and operating responsi-

[335]

bilities. For practical purposes

responsibility for personnel management in the Reserve Components was a

separate area with its own personnel management program. TAGO also

supervised Army recruiting, induction, and personnel processing in the

field. It ran the Army's welfare and morale programs. Finally TAGO was

the Army's chief administrative officer, records keeper, postman, and

printer.34

Improvements in personnel

management since World War II had been piecemeal. Personnel and manpower

statistics had greatly improved, especially after TAGO obtained the use

of a large computer in the 1950s. As a consequence, manpower controls

were more effective. Personnel classification and career management,

both military and civilian, had also improved. Combat arms officers, in

particular, were receiving much broader educations, both within and

outside the Army. This was less true for technical service

officers.35

The Personnel Management task

force did not believe that further major improvements in Army personnel

management were possible under the existing system. Co-ordination and

control were extremely difficult when twenty agencies shared

responsibility for the program. Second, the Army staff and DCSPER in

particular were too heavily involved in operations, and the Army staff's

long-range personnel planning had suffered as a consequence. A third

major criticism was that career management, especially in the technical

services, tended to be narrowly tailored to serve branch or service

interests.36

According to Mr. Hoelscher, the

most difficult area in reaching final agreement among the committee as a

whole concerned the initial or basic military training of the individual

soldier. This area extended from planning the Army's enlisted military

personnel requirements in terms of individual military occupations,

througFl induction, basic training, and ultimate assignment to specific

units or services. This was precisely the area where current

responsibilities were most fragmented and

[336]

HOELSCHER COMMITTEE PROPOSAL FOR OFFICE OF PERSONNEL OPERATIONS,

OCTOBER 1961

(AN ILLUSTRATIVE ORGANIZATION OF OFFICE OF PERSONNEL OPERATIONS)

Source: Hoelscher Committee Report, VI, p.57.

confused among the major Army

staff agencies and the technical services who were often at loggerheads

with each other. Known as the "Flow of Trainees through the

Training Base," this problem would continue to cause trouble.37

The Personnel Management task

force's principal recommendation was to consolidate control over Army

military personnel management in a single Office of Personnel Operations

and transfer to it all such functions performed by the Army staff,

including TAGO and the technical services, except for such professional

groups as the Army Medical Corps, the Judge Advocate General's Corps,

and the Chaplains Corps. DCSPER would retain responsibility for general

officer assignments. It also recommended organizing officer personnel

management within OPO along "branch" lines for technical

service as well as combat arms officers with brigadier generals assigned

as branch chiefs to provide proper top-level supervision. (Chart 29)

OPO would operate under the

General Staff supervision of DCSPER, and the Hoelscher Committee

stressed that the DCSPER and the Chief of OPO should not be the same

person since the purpose of OPO was to relieve DCSPER of all operating

responsibilities. TAGO would be abolished and its personnel

responsibilities transferred to OPO, including welfare and morale

services. Its personnel research function would be transferred to the

Army Research Office. The Hoelscher Committee also recommended

transferring responsibility for induction and recruiting, examination,

reception, transfer, and separation of enlisted personnel to the

proposed Individual Training Command tinder CONARC as mentioned

earlier.38

Civilian personnel management

received little attention. The Hoelscher Committee simply recommended

transferring this function from the technical services and from the Army

[337]

staff to OPO, stressing

that it remain a separate and distinct operation from military personnel

management.39

When Mr. Hoelscher's over-all

report and those of the task forces had been drafted, he submitted them

to the Secretary of the Army's staff and to the General Staff

representatives on the Project Advisory Committee for comment.40

The

technical services, the agencies most vitally affected by the proposed

reorganization, were not consulted. General Colglazier, the Deputy Chief

of Staff for Logistics, informed technical service chiefs in late

September that their comments were not wanted at this time and cautioned

them against revealing information on Project 80 to

"unauthorized" persons.41

General Colglazier's office had

kept the technical service chiefs reasonably well informed of

developments. Brig. Gen, James M. Illig, Chief of DCSLOG's Office of

Management Analysis, and his assistant chief, Dr. Wilfred J. Garvin, as

members of the Project Advisory Committee, were the principal contacts

between the Hoelscher Committee and the technical services. At the end

of July General Illig and Dr. Garvin learned of the alternative

organization patterns being considered and developed a set of DCSLOG

counterproposals.

The "Illig-Garvin"

proposals and the criticisms of the final Hoelscher Committee report,

also made by General Illig and Dr. Garvin, represented a rough consensus

among DCSLOG and the technical services. They accepted the Hoelscher

Committee concept of one or more logistics commands, but insisted the

technical service chiefs should remain as such on the Army staff with

responsibility for personnel management and training.42

[338]

The creation of a logistics

command, General Illig and Dr. Garvin said, was preferable to the

situation that had developed since the Palmer reorganization of 1954-55

were there was no effective direction and control over the technical

services short of the Chief of Staff himself. The evil, as they saw it,

and the great "divisive" influence within the Army was the

progressive "functionalization" of Army operations, programs,

and budgets.

"The preoccupation of multiple Army staff agencies

with specialized functional areas and related programs and budgets had

impaired the command integrity of the Technical Services and prevented

effective management of their several functions towards a common

end." The technical services were the victims rather than the cause

of the trouble. Illig and Garvin believed a Systems and Materiel Command

such as the Hoelscher Committee proposed was clearly preferable to the

evil consequences of the creeping functionalization of the past decade.

They did not agree with the

Hoelscher Committee's contention that the Army staff should divorce

itself from operations. The technical services had long and successfully

exercised both staff and command functions. Detailed control by the Army

staff was necessary to answer questions and meet criticisms from the

Bureau of the Budget, the General Accounting Office, and Congress.

Increasing costs, decreasing appropriations, and technical problems

encountered in the earlier stages of research and development were other

reasons why DCSLOG and other Army staff agencies had to exercise

detailed controls over operations.43

Concerning the organization of

the Army staff General Illig and Dr. Garvin opposed continued separation

of research and development from production, preferring an arrangement

which separated development and production from supply and distribution.

They opposed a separate Deputy Chief of Staff for Strategy and

International Affairs, suggesting instead creating an operating deputy

for JCS affairs within the Office of the Chief of Staff. They objected

to the proposal for a Director of the Army Staff as an additional

unnecessary staff layer. This

[339]

was the Vice Chief of Staff's

responsibility. An assistant to the Vice Chief of Staff who would direct

Army staff programing and systems management was preferable to the

proposed deputy for these functions. The heads of Army staff agencies

also should retain their right of personal access to the Chief of Staff.

No change in traditional Army staff procedures which eliminated this

right was acceptable.44

General Illig and Dr. Garvin

agreed on the creation of a separate combat developments agency. They

opposed making CONARC responsible for all technical training because

technical service specialists, including civilian experts, not only

worked with the combat arms but also within the Army's wholesale

logistic system and in jointly staffed defense agencies like the new

Defense Supply Agency on functions unrelated to CONARC's training

mission. For similar reasons Illig, Garvin, Colglazier, and the

technical service chiefs opposed transferring technical service military

officer personnel management to the proposed Office of Personnel

Operations where the influence of the combat arms would be predominant.

They simply did not believe combat arms oriented agencies like CONARC or

OPO could produce the kind of skilled technicians required in an era of

rapid technological change .for service throughout the Army and

Department of Defense. It was clear from all their comments that DCSLOG

and the technical service chiefs objected more to losing responsibility

for military training and officer personnel management than any other

features of the Hoelscher Committee report.

Under the alternative

organization proposed by Illig and Garvin, responsibility for individual

training and personnel management would remain under the technical

service chiefs as Army staff agencies. To the new Systems and Materiel

Command they proposed also transferring "career management and

personnel operations" of the Army's wholesale logistic

establishment as part of "the command function of the Technical

Services" it would inherit. In summary, they recommended that

the Army assure the retention at

departmental headquarters of a strong technical staff to perform all

staff functions currently prescribed

[340]

for the Chiefs in the Technical

Service [sic] in AR 10-5, to manage the careers of all military

personnel assigned to Army technical corps, to direct and control Army

technical schools, and to furnish those currently assigned Army-wide

services which are not transferred to the Systems and Materiel Command 45

The Hoelscher Committee made

some minor adjustments as the result of Army staff criticisms. The final

report as submitted to the Chief of Staff on 5 October 1961 and on 16

October to Secretary McNamara included the following principal

recommendations:

The technical services and The

Adjutant General's Office were to be functionalized. The agencies

primarily affected were the offices of the chiefs of the technical

services which were either abolished or reorganized functionally as Army

staff agencies except for the Surgeon General and the Chief of

Engineers. The field installations of the technical services were to

remain, although their exact relations to the new field commands were

undecided. Technical service personnel would still retain their branch

insignia and designation just as the combat arms had after the abolition

of the chiefs of the combat arms under the Marshall reorganization in

1942.

The principal logistics agency

of the Army in place of the technical services was to be a single

Systems and Materiel Command. It would be responsible for the entire

materiel cycle from research and development through distribution and

major maintenance activities, except for combat development functions.

It would inherit most of the personnel and field installations of the

technical services.

A second new major field command

would be a Combat Developments Agency. It would be responsible for

integrating this function, fragmented until then among the several

technical services and CONARC, and its personnel would be drawn largely

from these agencies.

CONARC would be reorganized as a

Force Development Command, a designation later dropped, to include all

the technical service schools and training facilities, while losing its

combat development functions to the Combat Developments Agency. A new

major field command under CONARC would be responsible for training

individuals, including their

[341]

induction and processing,

functions currently assigned to The Adjutant General's Office.

Another new field agency rather

than a command was to be the Office of Personnel Operations responsible

for all Army personnel management functions previously performed by

DCSPER, The Adjutant General's Office, and the technical services. The

management of general officer careers would remain a DCSPER function.

The real change centralized the

personnel management of technical service officers under OPO because

personnel management of technical service enlisted personnel had already

been centralized in The Adjutant General's Office.

Less noticed was the

reorganization of Army headquarters proposed by the Hoelscher Committee

because this feature was largely eliminated in the final reorganization

plan approved by Secretary McNamara. The principal changes proposed were

to create a Director of the Army Staff with the rank of lieutenant

general to act as the deputy of the Vice Chief and Chief of Staff in

supervising the work of the Army staff. Second, the committee proposed

to separate the operational planning and training functions of DCSOPS

into two agencies, a Deputy Chief of Staff for Strategy and

International Affairs and another for Plans, Programs, and Systems,

which would include responsibility not only for organization and

training but also for co-ordinating Army plans, programs, and budget

functions in these areas.

The Adjutant General's Office

was to be abolished with its personnel functions going to OPO and CONARC,

while its administrative functions would be reorganized under a new

Chief of Administrative Services. The Office of the Chief of Military

History would be abolished also and its functions transferred to the

latter agency.

While public attention focused

on the organizational changes proposed by the Hoelscher Committee, the

latter made two major recommendations for improving Army staff

procedures. First, it recommended that the General Staff divorce itself

from operating responsibilities by transferring personnel responsible

for such functions to the new major field commands. The principal agency

affected would be DCSLOG, which as a

[342]

result of the Palmer

reorganization in 1955 had greatly increased its staff. Second, it

proposed to reform the General Staff's "staff actions"

procedures by cutting down on the number of formal concurrences required

in favor of procedures which were aimed at producing quicker and clearer

decisions and actions.46

Six months of detailed research

by a carefully selected staff which balanced professional and military

talent in many areas made the Hoelscher Committee report the most

thorough and detailed investigation of Army organization and management

since World War I. Following submission of his report, Hoelscher and his

headquarters staff conducted special briefings at Carlisle Barracks in

mid-October for Secretary Stahr, General Decker, the General Staff, and

representatives of the technical services. General Decker then disbanded

the Hoelscher Committee, except for a small headquarters staff.

[343]

Endnotes

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

Return to the Table of Contents