CHAPTER XVIII

Trail 2 and the Pockets

During the three weeks that the Battle of the Points raged along the west coast, another hard-fought battle was being waged along the front lines. No sooner had the troops completed their withdrawal from the Abucay-Mauban line to the reserve battle position then the Japanese struck again. In II Corps the Japanese blow came in the center where, in the confusion which accompanied the establishment of the new line, there was a dangerous gap during the critical hours before the attack. Fortunately it was closed before the Japanese could take advantage of the opening. I Corps, where a similar gap developed, was not so fortunate. Here the Japanese poured through the hole before it could be plugged and set up strong pockets of resistance behind the line. For the next three weeks, simultaneously with the Battle of the Points and the fight in II Corps, Wainwright's troops were engaged in a bitter struggle to contain and reduce these pockets. Thus, in the period from 23 January to 17 February, the American positions on Bataan were under strong attack in three places: along the west coast beaches and at two points along the reserve battle line, now the main line of resistance, in I and II Corps.

By the morning of 26 January most of the American and Filipino troops were in place along the reserve battle position, their final defense line on Bataan. The new line extended from Orion westward to Bagac, following a course generally parallel to and immediately south of the Pilar-Bagac road which it crossed in the center. (Map 17) Having left behind Mt. Natib, "that infernal mountain which separated our corps," the troops were able now for the first time to form a continuous line across Bataan and to establish physical contact between the two corps.1 They were also able to tighten the defenses along the front and at the beaches, for the withdrawal had reduced the area in American hands by almost 50 percent.

The area into which the 90,000 men on Bataan were now compressed covered about 200 square miles. On the north, in the saddle between Mt. Natib and the Mariveles Mountains was the Pilar-Bagac road which extended across the peninsula like a waist belt. To the east, west, and south was the sea. As Mt. Natib had dominated the Abucay- Mauban line, so did the imposing mass of the Mariveles Mountains dominate southern Bataan. Except for the narrow coastal strip along Manila Bay, the entire region was rugged and mountainous, covered with forest and thick undergrowth. The temperature averaged about 95 degrees. Even in the shaded gloom of the jungle the heat during midday was intense. Any physical exertion left a man bathed in perspiration and parched from thirst. As it was the dry season there were no rainstorms to afford any relief. "The heat," complained

[325]

General Nara, "was extreme and the men experienced great difficulty in movement."2 When the sun set the temperature dropped sharply and those who had sweltered in the tropical heat during the day shivered with cold under their army blankets.

Forming the boundary between the two corps was the Pantingan River which flowed generally northward from the Mariveles peaks. On the east side of the river, in the II Corps area, was 1,920-foot-high Mt. Samat, four miles from the coast and a short distance south of the Pilar-Bagac road. Along its slopes and on its summit were high hardwood trees, luxuriant creepers, and thorny vines. Though movement through this jungled fastness was difficult, the heights of Mt. Samat afforded excellent observation of the entire battlefield below.

North of Mt. Samat, as far as the Pilar- Bagac road, the ground was similar to that on the slopes. Beyond, in the area held by the enemy, it was low and swampy. To the east of the mountain lay a plateau and along the coast were sugar-cane fields, thickets, and a plain. Flowing from the high ground in the center, through the coastal plain, were several large rivers and numerous small streams, many of them dry at this time of the year. But their steep, forested banks provided natural barriers to the advance of a military force.

Wainwright's I Corps was west of the Pantingan River. Here there were no plains or sugar-cane fields. The ground sloped sharply from the Mariveles Mountains almost to the sea, and the undergrowth was even more luxuriant and forbidding than on the east coast. Nowhere on Bataan was the terrain less suitable for military operations.

In moving to the new line, the Americans had relinquished control of the Pilar-Bagac road, the one lateral highway across Bataan. However, they had denied the enemy complete use of that valuable road by selecting commanding positions from which it could be brought under fire, and by extending the main line of resistance across the road in the center of the peninsula. A four-mile-long branch road, or cutoff, had been constructed from Orion to the Pilar-Bagac road, and the eastern portion of the II Corps line extended along this cutoff rather than along the road itself. To provide lateral communication behind the lines, the engineers were directed to link the east-west trails, a task that was completed by mid-February. The Americans still had possession of the southern portions of the East and West Roads and continued to use them as the main arteries for vehicular traffic. All other movement behind the line was by footpath and pack trail.

The organization of the new line differed in one important respect from that established for the Abucay-Mauban line. Because of the reduced size of units, the shortage of trained combat officers, and the difficulty of communications, the troops on the Orion-Bagac line were placed under sector commanders who reported directly to corps. Under this arrangement unit designations lost much of their validity and some divisions functioned only as headquarters for a sector. Thus, one sector might consist of three or more units, all under a division commander who retained only his division staff. This organization simplified control by

[326]

corps also, for divisions and lesser units reported now to the sector commanders. There was, it is true, a natural tendency toward building up a large staff in the sectors, but this inclination was quickly discouraged by MacArthur's headquarters, which explained that the sector organization had been adopted "for the purpose of decreasing rather than increasing overhead."3

General Parker's II Corps line stretched from Orion on the east coast westward for about 15,000 yards. Initially the corps was organized into four sectors, lettered alphabetically from A through D. Sector A on the right (east), which comprised the beach north of Limay to Orion and 2,500 yards of the front line, was assigned to the Philippine Division's 31st Infantry (US) which was then moving into the line. To its left and continuing the line another 2,000 yards was Sector B, manned by the Provisional Air Corps Regiment. This unit was composed of about 1,400 airmen equipped as infantry and led by Col. Irvin E. Doane, an experienced infantry officer from the American 31st Infantry. Sector C was under the command of Brig. Gen. Clifford Bluemel and consisted of his 31st Division (PA), less elements, and the remnants of the 51st Division (PA), soon to be organized into a regimental combat team. Together, these units held a front of about 4,500 yards. The remaining 6,000 yards of the II Corps line in front of Mt. Samat and extending to the Pantingan River constituted Brig. Gen. Maxon S. Lough's Sector D. Lough, commander of the Philippine Division, had under him the 21st and 41st Divisions (PA) and the 57th Infantry (PS)-not yet in the line-from his own division. Both Bluemel and Lough retained their division staffs for the sector headquarters. A final and fifth sector, E, was added on 26 January when General Francisco's beach defense troops were incorporated into II Corps and made a part of Parker's command. In reserve, Parker kept the 1st Battalion, 33d Infantry (PA), from Bluemel's 31st Division, and a regiment of Philippine Army combat engineers.

The emplacement of artillery in II Corps was made with a full realization of the advantages offered by the commanding heights of Mt. Samat. On and around the mountain, in support of General Lough's sector, were the sixteen 75-mm. guns and eight 2.95-inch pack howitzers of the 41st Field Artillery (PA). Along the high ground east of the mountain, in support of the other sectors, were the artillery components of the 21st, 31st, and 51st Divisions (PA), with an aggregate of forty 75-mm. guns, and two Scout battalions equipped with 75's and 2.95's. The Constabulary troops on beach defense, in addition to the support furnished by the 21st Field Artillery, were backed up by about a dozen naval guns. Corps artillery consisted of the 301st Field Artillery (PA) and the 86th Field Artillery Battalion (PS), whose 155-mm. guns (GPF) were emplaced in the vicinity of Limay.4

General Wainwright's I Corps line, organized into a Right and Left Sector, extended for 13,000 yards from the Pantingan

[327]

River westward to the South China Sea. Separating the two sectors was the north-south Trail 7. The Right Sector, with a front of about 5,000 yards to and including Trail 7, was held by the 11th Division (PA) and the attached 2d Philippine Constabulary (less one battalion). Brig. Gen. William E. Brougher commanded both the 11th Division and the Right Sector. Between Trail 7 and the sea was the Left Sector, commanded by Brig. Gen. Albert M. Jones, who had led the South Luzon Force into Bataan. The eastern portion of his sector was held by the 45th Infantry (PS); the western by Brig. Gen. Luther Stevens' 91st Division (PA). Like Parker, Wainwright was given responsibility for the beach defenses in his area and on the 26th he established a South Sector under General Pierce. For corps reserve, Wainwright had the 26th Cavalry (PS) which had helped cover the withdrawal from the Mauban line.

I Corps had considerably less artillery than the corps on the east. Corps artillery consisted of one Scout battalion, less a battery, equipped with 75-mm. guns. Jones had for his Left Sector the guns of the 91st Field Artillery and attached elements of the 71st which had lost most of its weapons at Mauban. Supporting the Right Sector was the artillery component of the 11th Division and one battery of Scouts. Only a few miscellaneous pieces had been assigned initially to beach defense but after the Japanese landings Pierce obtained additional guns and two 155-mm. howitzers.5

When it established the Abucay-Mauban line early in January, USAFFE had kept in reserve the Philippine Division (less the 57th Combat Team). During the course of the battle on that line both the 31st Infantry (US) and the 45th Infantry (PS) had been assigned to II Corps and committed to action. When the withdrawal order was prepared, Col. Constant L. Irwin, USAFFE G-3, had placed the Philippine Division regiments in reserve since, he explained, "these were the only units that we had upon which we could depend and which were capable of maneuver, especially under fire."6 This provision of the withdrawal plan was immediately changed by General Sutherland who believed that the corps commanders "needed all available help in order to successfully occupy the new line and at the same time hold the attackers."7 Both corps commanders therefore assigned their Philippine Division units to critical points along the new line, and USAFFE approved this assignment. It made no provision, however, for a reserve of its own, on the assumption that "after the withdrawal was accomplished an Army Reserve could be formed."8

Sometime during the 25th of January USAFFE reversed its stand and decided that it would require a reserve after all. The unit selected was the Philippine Division with its one American and two Scout regiments. This action was based, apparently, on the danger arising from the Japanese landings at Longoskawayan and Quinauan Points. General Sutherland felt, Colonel Irwin later explained, that the three regiments might be needed to contain the Japanese at the beaches and push them back into the sea.9 When the corps commanders

[328]

received the orders to send the three regiments to an assembly area to the rear, they were thrown "into somewhat of a tailspin."10 The new line was already being formed and the departure of the three regiments or their failure to take up their assigned positions would leave large gaps in the line. Corps plans, so carefully prepared, would have to be hastily changed and shifts accomplished within twenty-four hours.11

The shifting of units which followed USAFFE's order was as confusing as it was dangerous. In II Corps, where the 57th Infantry (PS) had been assigned the extreme left and the 31st Infantry (US) the right flank of the line, General Parker sought to fill the gaps by sending elements of General Bluemel's 31st Division (PA) to both ends of the line. The Philippine Army 31st Infantry (less 1st Battalion) was fortunately on the east coast in the vicinity of Orion, and it was ordered to take over Sector A in the place of the American 31st Infantry. The 33d Infantry (PA), assigned to Sector C but not yet in position, was sent to the left of the line being formed to replace the 57th Infantry. In the confusion no one remembered to inform General Bluemel of these changes, although the 31st and 33d Infantry were a part of his division and assigned to his sector.

In I Corps, where the 45th Infantry had been assigned to the important area between the Camilew River and Trail 7 in General Jones's Left Sector, Wainwright was forced to fill the gap with elements of the reduced and disorganized 1st Division (PA). Two hastily reorganized battalions of the 1st Infantry were ordered into the line on the 26th as a stopgap until the rest of the division could be brought in, but it was not until the next day that the troops actually occupied their positions.

When these shifts were completed the line-up along the main battle position was as follows: In II Corps, from right to left: Sector A, 31st Infantry (PA); Sector B, Provisional Air Corps Regiment; Sector C, unsettled but temporarily held by the 32d Infantry, one battalion of the 31st, and the 51st Combat Team; Sector D, 21st and 41st Divisions (PA) and the 33d Infantry (less 1st Battalion). In I Corps: Right Sector, 2d Philippine Constabulary and 11th Division (PA); Left Sector, elements of the 1st Division (PA) and the 91st Division. The reserve of the two corps remained unchanged but was backed up now by the Philippine Division in USAFFE reserve. The American 31st Infantry was located just north of Limay on the east coast, from where it could support II Corps should the need arise. The 45th Infantry was in bivouac near the West Road, about three miles south of Bagac, in position to aid I Corps. The 57th Infantry was near Mariveles, ready for a quick move to either corps.12

Opposing the Filipino troops-the entire line, except for Sector B, was now held by the Philippine Army-were the same Japanese who had successfully breached the Abucay-Mauban line in the first battle of Bataan. On the east, before Parker's II Corps, was General Nara's 65th Brigade and attached 9th Infantry; facing Wainwright was the Kimura Detachment. While General Kimura's force of approximately 5,000 men was comparatively fresh, Nara's troops

[329]

had been hard hit during the Abucay fight. By 25 January, with reinforcements, he had built up his two regiments, the 141st and 142d, to a strength of about 1,200 men each.13

Flushed with victory and anxious to end the campaign quickly, the Japanese hardly paused before attacking the Orion-Bagac line. Some time earlier they had found a map purportedly showing the American scheme of defense. On it, marked in red, were lines denoting the positions occupied by the American and Philippine troops. The main line of resistance was shown some miles south of its actual location, extending from Limay westward to the Mariveles Mountains. The positions from Orion westward, shown on the map and corresponding to the line actually occupied, were sketchy and the Japanese concluded that they were merely outposts. On the basis of this map General Homma made his plans. He would push his troops through the outpost line-actually the main line of resistance-and strike for Limay, where he conceived the main line to be and where he expected the main battle for Bataan would be fought.

At 1600, 26 January, General Homma issued his orders for the attack. The 65th Brigade was to sweep the supposed outpost line into Manila Bay, then proceed south to the presumed main line of resistance. General Kimura was ordered to drive down the west coast as far as the Binuangan River, which Homma apparently believed to be an extension of the Limay line. No difficulty was expected until this line was reached. So confident was Homma that his estimate was correct and so anxious was he to strike before the Americans could establish strong positions near Limay that he decided against waiting for the artillery to move into position to support the attack.14

Unfortunately for the Japanese their captured map was incorrect or they read it incorrectly. The first line they met was not the outpost at all but the main line of resistance. The Japanese did have the good fortune, however, to hit the line where it was weakest and at a time when the disorganization resulting from the withdrawal of the Philippine Division was greatest.

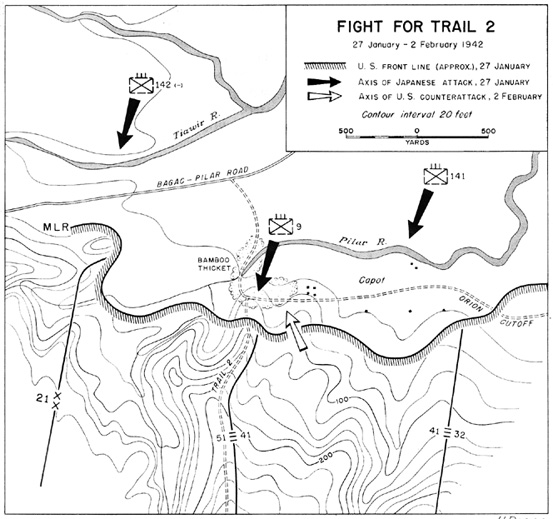

It was General Bluemel's Sector C which bore the brunt of the 65th Brigade attack against II Corps. For three quarters of its total length of 4,500 yards, the front line of this sector followed roughly the Orion cutoff to its intersection with the Pilar River and at that point straddled the north end of Trail 2 which led southward along the east slopes of Mt. Samat through the American lines. With the exception of the East Road this trail offered the easiest route of advance to the Japanese.

Bluemel had organized the defense of his sector on the assumption that he would have most of his 31st Division and what was left of the 51st to put into the line. Accordingly, he had assigned the right (east) portion of the line, from Sector B to Trail 2, to his own division; the left to the 1,500 men of the 51st Division. On each side of Trail 2, for a distance of about 600 yards, foxholes had been dug and wire had been strung.15

[330]

On the morning of 26 January General Bluemel set out to inspect his front lines. On the way he met the 1st Battalion, 31st Infantry, heading east away from its assigned positions. With understandable heat, and some profanity, he demanded an explanation from the battalion commander, who replied that he had received orders from his regimental commander to move the battalion to Sector A to join the rest of the regiment. This was apparently the first time the general learned that his 31st Infantry had another assignment. Bluemel peremptorily ordered the battalion commander back into line and told him to remain there until relieved by his, Bluemel's, orders.16

The general had another unpleasant surprise in store that morning. He had hardly resumed his tour of inspection when, at about 1000, he discovered that the 33d Infantry was not in its assigned place on the right of Trail 2 and that this vital area was entirely undefended. For four hours Bluemel sought to locate the missing regiment and finally, at 1400, learned that this regiment also had been taken from him and was now assigned to the left flank of the corps line instead of the 57th Infantry. There was nothing else for him to do then but spread his troops even thinner and he immediately ordered the 2d Battalion, 32d Infantry, and the sixty men of the headquarters battery of the 31st Field Artillery, acting as infantry and armed only with Enfields, into the unoccupied area. It was not until 1730, however, that these units were able to complete their move. Thus, for a period of almost ten hours on the 26th, there had been no troops cast of the important Trail 2. Only good fortune and the action of the tanks of the covering force averted disaster. Had General Nara pushed his men down the trail during these hours he might have accomplished his mission and reached Limay even more rapidly than the misinformed Army commander expected him to.

Bluemel's troubles were not yet over. Only thirty minutes after he had closed the gap left by the transfer of the 33d Infantry, he received orders at 1800 from General Parker to transfer the 1st Battalion, 31st Infantry (PA), which he had sent back into the line early that morning, to Sector A. Bluemel had no choice now but to allow the battalion to leave. Parker promised him the 41st Infantry (less 1st Battalion) from the adjoining sector, but that unit would not reach him until late the next day. In the meantime he would have to fill the new gap with one of his own units. He finally decided to use the reserve battalion of the already overextended 32d Infantry. Thus, on the night of 26 January, the entire 31st Division area was held by only the three battalions of the 32d Infantry and the artillery headquarters battery. In reserve was the 31st Engineer Battalion with 450 men whose armament consisted exclusively of rifles.

The shifts in the line had been completed none too soon, for by 1900 of the 26th advance patrols of the 65th Brigade had penetrated down the Orion cutoff to Trail 2, almost to the main line of resistance.

General Nara received Homma's orders for the attack on the morning of the 27th,

[331]

too late to take advantage of the confusion in the American line. At that time the bulk of his force was concentrated in front of Sector C. Colonel Takechi's 9th Infantry, the "encircling unit" of the Abucay fight, was in position to advance down Trail 2, and the 141st Infantry was bivouacked about one mile to the east. Above Orion probing Parker's right flank was the 1st Battalion, 142d Infantry. The remainder of the regiment was south of Pilar, along the Pilar-Bagac road. Too far to the rear to support the attack was the artillery.

At 1100, 27 January, Nara issued his own orders for the forthcoming attack. These were based on 14th Army's erroneous assumption that the American positions in front of him constituted an outpost line and that the main objective was a line at Limay. Nara's plan was to make the main effort in the area held by Bluemel's men. The center of the attack was to be Capot, a small barrio near Trail 2 in front of the main line of resistance. Making the attack would be two regiments, the 9th on the right (west) and the 141st on the left. They were to advance as far as the Pandan River where they would make ready for the assault against the supposed main line of resistance near Limay. The advance of these two regiments would be supported by Col. Masataro Yoshizawa's 142d Infantry (less 1st Battalion) on the brigade right, which was to drive southeast across the slopes of Mt. Samat to the Pandan River. Having reached the river, Yoshizawa was to shift the direction of his attack and advance down the river in a northeasterly direction to take the defenders in the rear. The regiment's initial advance would bring it to the American main line of resistance at the junction of Sectors C and D.

The attack jumped off at 1500, 27 January, with a feint by Maj. Tadaji Tanabe's 1st Battalion, 142d Infantry, down the East Road. Although the Japanese claimed to have met "fierce" fire from the Filipinos in this sector, the 31st Infantry (PA) was not even aware that an attack was being made. At 1600 the rest of Colonel Yoshizawa's regiment attacked in the area between Sectors C and D, where the 51st Combat Team and 21st Division were posted. Without any difficulty the regiment occupied the outpost line, but was stopped cold at the main line of resistance. (Map 18)

The main attack by the 9th and 141st Infantry against Capot began as darkness settled over the battlefield. With the exception of a single battalion of Takechi's 9th Infantry, which managed to cross the Pilar River and entrench itself in a bamboo thicket about seventy-five yards north of the main line, this attack, like that of the 142d, failed to achieve its objective. General Nara was forced to conclude after the returns were in that a stronger effort would be required to drive the enemy into Manila Bay. But he still believed that the line he had unsuccessfully attacked on the night of the 27th was an advanced position or outpost line.17

Meanwhile the 41st Infantry, promised to General Bluemel on the 26th, had begun to arrive in Sector C. Advance elements of the regiment reported in on the evening of the 27th and by the following morning, after a twenty-four-hour march over steep trails carrying its own arms, equipment, and rations, the regiment, less its 1st Battalion, was on the line. The 3d Battalion took over a front of about 1,200 yards east of Trail 2, relieving the 2d Battalion, 32d Infantry. Since it had no machine guns, it was reinforced by Company H of the 32d, and the

[332]

MAP 18

headquarters battery of the 31st Field Artillery (PA). One company of the 41st, Company F, was placed on Trail 2, well behind the main line of resistance, in position to support the troops on either side of the trail. The 2d Battalion (less Company F) went into regimental reserve.

When all units were in place, Bluemel's sector was organized from right to left (east to west), as follows: 32d Infantry (less Company H); 41st Infantry reinforced by Company H, 32d Infantry, and Headquarters Battery, 31st Field Artillery; and the remnants of the 51st Division. To the rear, on Trail 2, was Company F, 41st Infantry.

On the afternoon of the 28th General Nara ordered his troops to continue the attack. This time, however, he placed more emphasis on the northeast slopes of Mt. Samat where he conceived the enemy strong

[333]

points to be, and requested support from the artillery. The 141st Infantry, which was east of the 9th, was directed to move west of that regiment, between it and the 142d, thus shifting the weight of the attack westward. Tanabe's battalion remained on the East Road.

As before, the attack began at dusk. At 1830 of the 29th the 142d Infantry on the brigade right waded the Tiawir River, in front of the 22d Infantry (Sector D), but was stopped there. The 141st, which was to attack on the left (east) of the 142d, failed to reach its new position until midnight, too late to participate in the action that night.

Colonel Takechi's 9th Infantry was hardly more successful than the 142d in its advance down Trail 2. Most of the regiment had crossed the Pilar River during the day to join the battalion in the bamboo thickets just in front of Bluemel's sector. From there the regiment had advanced by sapping operations as far as the wire entanglements on the front line. Thus, when Takechi's men moved out for the attack, after an hour-long preparation by the artillery, they were already at the main line of resistance.

The fight which followed was brisk and at close quarters. The 41st Infantry east of Trail 2, supported by machine gun fire from Company H, 32d Infantry, held its line against every onslaught, with Company K, on the trail, meeting the enemy at bayonet point. West of the trail, elements of the 51st Combat Team were hard hit and in danger of being routed. Fortunately, reinforcements arrived in time to bolster the extreme right of its line, closest to the trail, and the enemy was repulsed. Next morning when a count was made the Filipinos found about one hundred dead Japanese within 150 yards of the main line of resistance. Some of the bodies were no more than a few yards from the foxholes occupied by the Filipinos, who suffered only light casualties. Again General Nara's attempt to pierce what he thought was an outpost line had failed.

Action during the two days that followed was confusing and indecisive. The Japanese, after nearly a month of continuous combat, were discouraged and battle weary. Losses, especially among the officers, had been high. "The front line units," complained General Nara, "notwithstanding repeated fierce attacks . . . still did not make progress.... Battle strength rapidly declined and the difficulties of officers and men became extreme." When "the greater part of the Brigade's fighting strength," the 9th Infantry, was ordered by General Homma to join its parent unit, the 16th Division, General Nara's situation became even more discouraging.18 With commendable tenacity, however, he persisted in his efforts to break through the remarkably strong "outpost line," and on 31 January ordered his troops to attack again that night. This time he made provision for air and artillery support. The 9th Infantry, scheduled to move out that night, Nara replaced by Major Tanabe's battalion.

At 1700, 31 January, the assault opened with an air attack against II Corps artillery below the Pandan River. An hour later the artillery preparation began, and "Bataan Peninsula," in General Nara's favorite phrase, "shook with the thunderous din of guns." The Japanese laid fire systematically on both sides of Trail 2 and down the trail as far back as the regimental reserve line. At about 1930 the barrage lifted and the infantry made ready to attack. At just this moment the artillery in Bluemel's sector

[334]

opened fire on the ford over the Pilar River and the area to the north in what the Japanese described as "a fierce bombardment." Simultaneously, according to the same source, "a tornado of machine gun fire" swept across the right portion of the Japanese infantry line assembling for the attack, effectively ending Japanese plans for an offensive that night. The careful preparation by aircraft and artillery had been wasted and the attack, mourned General Nara, "was frustrated."19

That night Colonel Takechi began to withdraw his 9th Infantry from the bamboo thicket in front of the main line of resistance near Trail 2. Casualties in the regiment had been severe and the withdrawal was delayed while the wounded were evacuated. By daybreak, 1 February, only one of the battalions had been able to pull out of its position. The rest of the regiment, unable to move during the hours of daylight, remained concealed in the thicket until darkness. Then a second battalion began to pull back, completing the move that night. On the morning of the 2d, only one battalion of the 9th Infantry remained in the thicket.

Meanwhile General Nara had been receiving disquieting reports of heavy troops movements behind the American line. His information was correct. General Bluemel was making preparations for a counterattack. His first effort on the 30th to drive the Japanese from the bamboo thicket had failed because the artillery had been unable to place its shells on the target. What he needed to hit the thicket was high-angle fire, but he had had no light mortars and the ammunition of the 3-inch Stokes mortar had proved "so unreliable as to be practically worthless."20 Since then General Parker had given Bluemel a battery of 2.95-inch mountain pack howitzers and ordered him to attack again. By the morning of the 2d he was ready. The 2.95's, 300 to 400 yards from the thicket, were in position to deliver direct fire and the 31st Engineer Battalion (PA), drawn from reserve to make the attack, was in readiness behind the main line of resistance.

At 0800 the counterattack opened. While the pack howitzers laid direct fire on the target, the 31st Engineer Battalion crossed the main line of resistance and headed toward the enemy concealed in the thicket. They were supported in their advance by rifle and machine gun fire from the frontline units near Trail 2. The engineers had not gone far before they encountered stiff resistance from the single battalion of the 9th Infantry still in position. After a small gain the attack stalled altogether, and elements of the 41st Infantry were sent into the fight. The advance then continued slowly and by dusk the Filipinos, at a cost of twenty casualties, had reached the thicket. There they halted for the night.

Next morning, 3 February, when the engineers and infantry, expecting to fight hard for every yard, resumed the attack, they found their advance entirely unopposed. During the night the last of the 9th Infantry had slipped out of the thicket and across the Pilar River. Bluemel's troops thereupon promptly moved the outpost line forward to a ditch about 150 yards below the Pilar-Bagac road. The danger of a break-through along Trail 2 was over.

General Nara's ill fortune was matched only by his persistence. Although he had

[335]

MAP 19

been repulsed with very heavy casualties three times and had lost his strongest regiment, he was still determined to push the "outpost line" into the bay. During the next few days, while activities along the front were limited to patrol and harassing action by both sides, he reorganized his brigade, replenished his supplies, and sent out reconnaissance parties. By 8 February he was ready to resume the offensive and that afternoon told his unit commanders to stand by for orders. Before they could be issued, however, he received a telephone call from 14th Army headquarters at San Fernando suspending the attack. Late that night, at 2330, he received another call from San Fernando canceling his plans altogether and directing him to withdraw the brigade to a position north of the Pilar-Bagac road and there await further instructions.

General Homma's orders were based only partially on Nara's inability to reach Limay. Everywhere on Bataan the Japanese offensive had stalled. The landings along the west coast had by this time proved disastrous and had resulted in the destruction of two infantry battalions Homma could ill afford to lose. But even more serious was the situation along the I Corps line in western Bataan where General Kimura had launched an offensive on 26 January.

In western Bataan, as in the east, the Japanese had followed closely on the heels of MacArthur's retreating troops. General Homma's orders on 26 January had directed Kimura, as well as Nara, to push ahead rapidly without giving the enemy an opportunity to dig in. Nara, it will be recalled, had been ordered to drive toward Limay, where, according to the captured map, the new American line was located. Homma's orders to Kimura called for an advance as far as the Binuangan River, along which Homma believed Wainwright had established his main line as an extension of the Limay line to the east.(Map 19)

To make the attack General Kimura had the 122d Infantry (less two companies) of the 65th Brigade and Col. Yorimasa Yoshioka's 20th Infantry, 16th Division. Actually, all Yoshioka had for the fight to follow was the regimental headquarters, service elements, and the 3d Battalion (less one company)-altogether about 1,000 men. The rest of the regiment was already committed or stationed elsewhere.

[336]

Even before he issued orders for the attack, General Homma had made arrangements on 25 January to increase the size of the force arrayed against I Corps. Hoping to take advantage of Kimura's easy victory on the Mauban line, he had directed General Morioka in Manila to hasten to Olongapo and assume command of operations in western Bataan. Morioka, 16th Division commander, was to take with him two battalions of infantry-one of which was the 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry, later lost in the Battle of the Points-and the 21st Independent Engineer Regiment headquarters. This move, Homma directed, was to be completed on 27 January. Thus, in the attack against I Corps that followed, command quickly passed from Kimura, who initiated the fight, to General Morioka.

Wainwright's main line of resistance, it will be recalled, was organized into two sectors, a Right Sector under General Brougher and a Left Sector commanded by General Jones. Brougher's line extended from the Pantingan River to Trail 7, which led southward from the Pilar-Bagac road through the American positions to join the intricate network of trails to the rear. Responsible for both the river and the trail on his flanks, Brougher placed the Constabulary on the right to guard the approach by way of the river and to tie in with the left flank of II Corps. Next to it was the 13th Infantry (PA) of the 11th Division and on the left of Brougher's sector, defending Trail 7, was the 11th Infantry led by Col. Glen R. Townsend.

Responsibility for the area west of Trail 7 rested with General Jones. On the left he placed General Stevens' 91st Division. The eastern portion of the sector, from the Camilew River to but not including Trail 7, was initially assigned to the 45th Infantry (PS), but when that regiment was withdrawn on 26 January, on orders from USAFFE, Wainwright assigned the area to General Segundo's 1st Division (PA). Although two hastily organized battalions of the 1st Infantry and one of the 3d Infantry moved into the line vacated by the 45th, a gap still remained in the center. The next afternoon, 27 January, the 2d Battalion, 1st Infantry, was withdrawn from its position on beach defense near Bagac and sent in to fill the gap.21

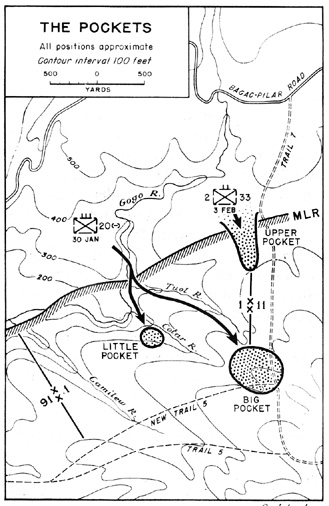

Wainwright's new main line of resistance ran through a thick jungle where it was extremely difficult for units to establish physical contact. Flowing in every direction through this area was a confusing network of streams. The Gogo River flowed into the Bagac River to form one continuous stream along the Left Sector main line of resistance. South of this east-west water line were three tributaries of the Gogo-the Tuol, Cotar, and Camilew Rivers. Behind the line was an equally confusing network of trails, intersecting each other as well as the main trails running south from the Pilar-Bagac road. New Trail 5 paralleled the main line of resistance and connected the West Road with

[337]

Trail 7. Below it and generally parallel to it was another trail, called Old Trail 5. So bewildering was the river and trail system, especially in the 1st Division area, that few of the troops knew precisely where they were at any given moment. It was in this area that the Japanese penetration came.

Establishment of the Pockets

The Japanese opened the offensive against I Corps on 26 January. Anxious to capitalize on his successful drive down the west coast, General Kimura sent his troops along the West Road against the 91st Division, on the extreme left of the line in the vicinity of Bagac. For two days, on the 26th and 27th, the Japanese sought to break through the new main line of resistance along the coast but the 91st held ground firmly. Repelled on the west, the Japanese, as they had done at Abucay, then began to probe the line in search of a soft spot. On the night of 28-29 January they found one in the 1st Division area.

The 1st Division had been badly disorganized and had lost much of its equipment in the first battle of Bataan and during the withdrawal along the beach. First sent to the rear for reorganization and a much needed rest, the division had then been hurriedly sent to the front on 26 and 27 January to replace the 45th Infantry. Since then the men had worked frantically to make ready for an attack. They dug trenches and cleared fields of fire but the work progressed slowly. Lacking entrenching tools and axes, many of the men had been forced to dig holes with their mess kits and clear the underbrush with their bayonets.

Before the men of the 1st Division could complete their preparations and while they were still stringing wire, they were hit by Colonel Yoshioka's 20th Infantry troops. The 1,000 men of the 20th Infantry first seized the high ground before the still unwired 1st Infantry sector. From this vantage point they pushed in the outpost line late on the 28th, drove back one company on the main line of resistance, and during the night moved rapidly through the gap up the valleys of the Cotar and Tuol Rivers, throwing out patrols as they advanced.

It is hard to imagine heavier, more nearly impenetrable or bewildering jungle than that in which Colonel Yoshioka's men found themselves. It is covered with tall, dense cane and bamboo. On hummocks and knolls are huge hardwood trees, sixty to seventy feet in height, from which trail luxuriant tropical vines and creepers. Visibility throughout the area is limited, often to ten or fifteen yards. There were no reliable maps for this region and none of the sketches then in existence or made later agreed. Major terrain features were so hazily identified that General Jones asserts that to this day no one knows which was the Tuol and which the Cotar River.22

Under such conditions it was virtually impossible for either side to maintain contact or to know exactly where they were. The Japanese moved freely, if blindly, in the rear of the 1st Division line, cutting wire communications and establishing strong points from which to harass the Filipinos. Segundo's men were almost as confused as the Japanese. They believed that only small enemy patrols had penetrated the line and sought blindly to find these patrols, sometimes mistaking friend for foe.

Before long, Colonel Yoshioka found his force split in two groups. One of these, less than a company, was discovered by 1st Divi-

[338]

sion patrols in a defensive position atop a hill just southeast of the junction of the Cotar and Gogo Rivers in the middle of the 1st Division area. This position, which became known as the Little Pocket, was about 400 yards below the main line of resistance and about 1,000 yards west of Trail 7.23

The bulk of Yoshioka's force continued to move east and soon was established along Trail 7 in the area held by Colonel Townsend's 11th Infantry. Its presence there was discovered on the morning of the 29th when the Provisional Battalion of the 51st Division led by Capt. Gordon R. Myers, moving north along Trail 7 to the aid of the 1st Division, met a Japanese force moving south. After a brief exchange of fire followed by a bayonet fight the Japanese broke off the action and withdrew. Not long after, 11th Infantry troops moving south from the front line along the same trail were fired on and killed. An American sergeant, sent forward from Colonel Townsend's 11th Infantry headquarters to investigate, met the same fate and his body was discovered about 200 yards north of the junction of Trails 5 and 7. It was clear now that an enemy force had established itself across the trail and the junction, nearly a mile behind the main line of resistance. From this position, which later came to be called the Big Pocket, the Japanese could block north-south traffic along Trail 7 and hinder the movement of troops westward along Trail 5.

There was as yet no indication of the size of the Japanese force in the pocket. Under the impression that only a strong patrol was blocking the trail, Colonel Townsend, on the afternoon of the 29th, ordered two reserve companies of the 11th Infantry to clear the area. The reaction of the Japanese to the attack quickly corrected Townsend's impression and a hasty call was put in for additional troops. USAFFE made available to corps the 1st Battalion of the 45th Infantry (PS) and by 2000 that night advance elements of the Scout battalion had reached the trail junction, ready to join in the fight the next day.

Attacks against the Big Pocket during the next few days by the Scouts on the South and the 11th Infantry troops on the north made little progress and only confirmed the fact that the enemy was strong and well entrenched. Yoshioka's troops had by now dug their foxholes and trenches and connected them with tunnels so that they could move freely without fear of observation. They had skillfully emplaced their machine guns behind fallen trees and had taken every advantage of the jungle to strengthen and conceal their defenses. They had even taken the precaution to dispose of the earth from the foxhole so as to leave no telltale signs of their position.

Artillery availed the Americans as little here as it had in the Battle of the Points. Poor visibility, inadequate maps, and the lack of high trajectory weapons resulted in shorts, overs, and tree bursts, some of which caused casualties among friendly troops. So dense was the jungle that one 75-mm. gun, originally emplaced to provide antitank defense at the trail junction, was unable to achieve any observable results though it poured direct fire on the enemy at a range of 200 yards. The value of the mortars was limited by the high percentage of duds as well as the thick jungle. Again, as on the beaches, the fight was to be a rifleman's fight backed up by BAR's and machine guns whenever they could be used.

The location of the Big Pocket created difficulties of an administrative nature. Although the pocket blocked the trail in the

[339]

11th Infantry area, on the internal flank of Brougher's Right Sector, it extended over into Jones's Left Sector, where the 1st Division was having difficulties of its own with the Japanese in the Little Pocket. Moreover, the pockets were not entirely surrounded and Yoshioka's men moved at will from one to the other. Just where the Big Pocket ended and the Little Pocket began was not yet clear and the 1st Division was as much engaged against the former as was the 11th Infantry. To clarify this situation, General Wainwright, who was present almost daily at the scene of the fighting, placed General Brougher, Right Sector commander, in charge of all troops operating against the Big Pocket. Colonel Townsend was given command of the forces immediately engaged.

The position of the Japanese in the two pockets was not an enviable one. Since 31 January, when 1st Division troops had shut the gate behind them, Colonel Yoshioka's men had been cut off from their source of supply. Though they had successfully resisted every effort thus far to drive them out, and had even expanded the original Big Pocket westward, their plight was serious. Without food and ammunition they were doomed. General Morioka attempted to drop supplies to them, but, as had happened during the Battle of the Points, most of the parachute packs fell into the hands of the Filipinos and Americans, who were grateful for the unexpected addition to their slim rations.

Only one course remained to Morioka if he was to save the remnants of Yoshioka's regiment. He must break through the main line of resistance again and open the way for a retreat-or further advance. All efforts by the 122d Infantry, which had been pushing against the 1st and 11th Divisions since the start of the attack, had thus far proved unavailing. But by 6 February Morioka had received reinforcements. One of the two battalions he had brought with him from Manila, the 2d Battalion of his own division's 33d Infantry, was now in position before the I Corps line, and the remnants of Colonel Takechi's 9th Infantry (less 3d Battalion) had reached western Bataan, after its fight on the east with Nara's brigade, to join its parent unit, the 16th Division, for the first time in the campaign.

With these forces Morioka launched a determined effort to relieve and reinforce the men in the pockets. The 2d Battalion, 33d Infantry, he sent down Trail 7. The 122d Infantry he strengthened by attaching two battalions of the 9th Infantry so that it could increase its pressure against the two Philippine divisions in the center of the line. The attack began late on the 6th, and shortly after midnight those Japanese advancing down Trail 7 overran a platoon of Company F, 11th Infantry, which was holding the critical sector across the trail. Eighteen of the twenty-nine men in the platoon were killed in their foxholes. For the moment it seemed as though the Japanese would be able to advance unhindered down Trail 7 to take the Filipinos on the north side of the Big Pocket in the rear. Only the quick action of Maj. Helmert J. Duisterhof, commanding the 2d Battalion, 11th Infantry, prevented this catastrophe. Organizing a containing force from the men in headquarters and from stragglers, he kept the Japanese to a gain of 600 yards, 800 short of the Big Pocket. The troops on each side of the penetration held firm so that what had promised to be another break-through became a fingerlike salient, referred to as the Upper Pocket.

Morioka had failed to reach Yoshioka but

[340]

he had broken the main line of resistance at still another point and attained a position which posed a real threat to the security of Wainwright's I Corps. The formation of the pockets-one of them actually a salient, for the main line of resistance was not restored- was now complete.

Reduction of the Pockets

While Morioka had been making preparations for the attack which gained for him the Upper Pocket, Wainwright had been laying his own plans to reduce the pockets. Thus far all attacks against them had failed. Though General Segundo had sent in all the troops he could spare to destroy the Little Pocket in the middle of the 1st Division area, he had been unable to wipe out the small force of Japanese entrenched there. Against the larger force in the Big Pocket Brougher had pressed more vigorously but with as little success. On the north and northeast he had placed two companies, G and C, of the 11th Infantry; on the south the 1st Battalion, 45th Infantry. Guarding Trail 5, south and west of the pocket, was the Provisional Battalion, 51st Division, which had made the initial contact with Yoshioka's men on Trail 7.

On 2 February Brougher had tried to reduce the pocket with tanks. After a reconnaissance had revealed that the jungle would not permit an unsupported armored attack, a co-ordinated infantry-tank attack was made with a platoon of four tanks from Company A, 192d Tank Battalion, closely supported by a platoon from the 1st Battalion, 45th Infantry. The armored platoon ran the enemy gantlet along Trail 7 and emerged on the north side of the pocket after losing one tank. The infantry, however, made only slight gains. An attack the next day brought similar results and the loss of another tank.

It was during that day's action that Lt. Willibald C. Bianchi won the Medal of Honor. Though assigned to another unit he had volunteered to accompany the supporting platoon sent out to destroy two machine gun positions. Leading part of the platoon forward he was wounded in the left hand. Refusing to halt for first aid he continued on, firing with his pistol. One of the enemy machine guns he knocked out with grenades. Meanwhile the tank, unable to lower the muzzle of its 37-mm. gun sufficiently, had been having difficulty reducing the other machine gun near by. Bianchi, who now had two more bullets in his chest, clambered to the top of the tank and fired its antiaircraft gun into the enemy position until the impact of a third bullet fired at close range knocked him off the tank. He was evacuated successfully and after a month in the hospital was back with his unit.24

By 4 February three of the four tanks of the Company A platoon had been destroyed and it was necessary to assign to Brougher's force another platoon from Company B of the 192d Tank Battalion. The attack was continued that day with as little success as before, and on the night of the 4th the Japanese were still in firm possession of the pockets. It was evident that a co-ordinated and stronger offensive than any yet made would be required for victory and General Wainwright called a meeting of the major commanders concerned to discuss plans for such an offensive.

The conference opened at about 1000 of the 5th at the command post of the 1st Divi-

[341]

sion. Present were Generals Jones, Brougher, and Segundo, Col. William F. Maher, Wainright's chief of staff, and Col. Stuart C. MacDonald, Jones's chief of staff. First Wainwright made the point that though the pockets overlapped sector boundaries the forces engaged would have to be placed under one commander and be treated as a single operation. All available forces, including the reserves, he asserted, would have to be thrown into the fight. Brougher was to be relieved and Jones would take command of all troops already engaged against the pockets. This decision gave the new commander the following force: 1st Battalion, 45th Infantry; the Provisional Battalion, 51st Division; Companies C and G, 11th Infantry; the 1st and 2d Battalions, 92d Infantry; the 1st Division; and the remaining tanks.

General Jones had a plan ready. First he would isolate the pockets and then throw a cordon of troops around each. The main attack against the Little Pocket would follow, and after it had been reduced he would throw all his troops against the Big Pocket. The entire operation would be a co-ordinated one with the main attacks against each pocket delivered along a single axis of advance. Wainwright approved the plan and directed that it be put into effect not later than 7 February.

Jones immediately made preparations for the reduction of the two pockets. All 1st Division troops who could be released from their posts along the main line of resistance were given to Colonel Berry, commander of the 1st Infantry, who was directed to make his own plans to take the Little Pocket. Lt. Col. Leslie T. Lathrop, commander of the 1st Battalion, 45th Infantry, was given tactical command of the troops for the assault against the Big Pocket. Jones himself worked out the plan for that attack. The main effort was to be made by the 1st Battalion, 92d Infantry, from the west. To its south would be the Provisional Battalion, 51st Division; to its north Company G, 11th Infantry. Company C, 11th Infantry, and the 1st Battalion, 45th Infantry, were to remain northeast and east of the pocket to prevent a breakout in that direction. The offensive against the two pockets would begin at 0900, 7 February.

The night before the attack Morioka opened his own offensive which by morning of the 7th had resulted in the salient called the Upper Pocket. Brougher, fearing a Japanese break-through at the salient, took from the forces Jones had gathered for the attack Company A, 92d Infantry, the reserve company of the battalion which was to make the main effort against the Big Pocket, and the tank platoon. At 0730, when Jones learned of the unauthorized transfer of his troops, he was forced to delay the hour of the attack against the Big Pocket to bring in more troops. It was not until 1500 that the replacement, Maj. Judson B. Crow's 2d Battalion, 92d Infantry, arrived.25

The attack against the Big Pocket began as soon as Major Crow's battalion was in place. By that time only a few hours of daylight remained and few gains were made. Moreover it was discovered late in the day that the 92d Infantry troops on the west had failed to establish contact with Company G, 11th Infantry, to its left (north) and that the pocket was not surrounded. Next morning the cordon around the Big Pocket was completed when these units tied in their flanks. Jones now waited

[342]

for the completion of the action against the Little Pocket before beginning his final assault against Yoshioka's men on Trail 7.

The attack against the Little Pocket had begun on schedule at 0900 of the 7th. Colonel Berry organized his 1st Division troops so that they approached the pocket from all sides, and then began to draw the noose tight. Evening of the first day found the Little Pocket only partially surrounded and it was not until nightfall of the 8th that Berry was ready to make the final attack from the southeast. Even then the pocket was not entirely enclosed, for a small gap remained on the east. The attack next morning was anticlimactic. When Berry reached the area that the Japanese had so stoutly defended for ten days he found only the bodies of the slain and discarded equipment. The enemy had escaped during the night by way of the one opening in the otherwise tight cordon of Filipino troops. The Little Pocket had been reduced but now there were Japanese loose somewhere behind the 1st Division line.

The small Japanese force which had escaped from the pocket was soon discovered near the main line of resistance on the west of Trail 7, evidently seeking to make its way back into the Japanese line. By accident it had stumbled into a trap, for in holding firm the west shoulder of the salient created by the Japanese attack of the 7th, the troops had so sharply refused their flank that the line resembled a horseshoe with the opening facing west. It was into this horseshoe that the Japanese from the Little Pocket stumbled on the morning of the 9th. Offered an opportunity to surrender, they replied with gunfire and in the brief fight which followed were entirely annihilated.

With the reduction of the Little Pocket and the destruction of the escaping Japanese on the morning of the 9th, General Jones was free to concentrate his entire force on the Big Pocket. But the situation had changed radically for earlier that morning General Morioka had received orders to pull back his troops to the heights north of Bagac.26 Immediately he directed Colonel Yoshioka to discontinue his efforts to hold the pocket and to fight his way back through the American lines. To cover the retreat, the 2d Battalion, 33d Infantry, in the Upper Pocket was to redouble its efforts to break through the holding force and join Yoshioka's men. Thus, as General Jones was making ready for the final attack against the Big Pocket, Yoshioka was hurriedly making his own preparations for a withdrawal.

On the American side the 9th and 10th were busy days. Colonel Berry, who now commanded the 1st Division, brought his force from the Little Pocket into the fight against the Big Pocket. On Jones's orders he placed his men in position to prevent a juncture between the enemy in the Upper Pocket and Yoshioka's troops. The rest of the 1st Division spent these days selecting and preparing a more favorable line along the south bank of the Gogo River. Meanwhile units surrounding the Big Pocket kept pressing in until they were so close that fire from one side of the pocket became dangerous to friendly units on the other side. Pushing in from the west were the two battalions of the 92d Infantry; on the opposite side of the pocket were the Scouts and Company C of the 11th Infantry. The Provisional Battalion, 51st Division, was pressing northward along Trail 7, while Company G, 11th Infantry, pushed south down the trail. The weakest link in the chain encircling the

[343]

pocket was on the north and northeast where the almost impenetrable jungle prevented close contact between the two 11th Infantry companies and the adjoining flank of the 45th Infantry. It was against this link, where a break was already evident, that Yoshioka's men would have to push if they hoped to escape.

Yoshioka's position was critical. A withdrawal in the face of these converging attacks would be a difficult and dangerous maneuver under the most favorable circumstances. With his exhausted troops the task would be even more hazardous. His men, who had been living on a diet of horseflesh and tree sap for days, were half starved, sick, and utterly worn out by two weeks of continuous fighting in the jungle. Until the 10th Yoshioka had been able to draw a plentiful supply of water from the Tuol River, but the advance of the 92d Infantry had closed off this source to him and he was feeling the effects of the shortage. Over one hundred of his men were wounded and would have to be carried or helped out during the withdrawal. Many of his officers had been killed and the maintenance of march discipline in the thick jungle promised to be a difficult task.

On 11 February the Filipinos were remarkably successful in pushing in the pocket. By 1000 that day all of Trail 7 had fallen to the Scouts. On the south the Provisional Battalion made excellent progress during the day while the two battalions of the 92d continued to push eastward against light opposition. By evening, wrote Jones's chief of staff, "it was quite obvious that the end was in sight."27 The attackers, unaware that Yoshioka had begun his weary trek northward, attributed their success to the enemy's lack of water and to the steady pressure exerted by the troops.

Only on the north had the Filipinos failed to register any great successes on the 11th. Here the two companies of the 11th Infantry and the northernmost element of the 45th Infantry, converging toward Trail 7, had failed to establish physical contact and one of them had lost its bearings and become dispersed. It was through these units that Yoshioka took his men.28

Command of the forces engaged in the Big Pocket fight changed again on 11 February. General Jones had come down with acute dysentery on the afternoon of the 11th and had been evacuated to the rear on a stretcher. Colonel MacDonald, his chief of staff, assumed command temporarily until General Wainwright placed Brougher in command the next day, 12 February.

By this time the fight for the pocket was almost over. On the afternoon of the 12th the unopposed Filipinos reached the junction of Trails 5 and 7 and on the following day moved through the entire area systematically to mop up whatever opposition they could find. There was none. The only living beings in the pocket were a number of horses and mules which the Japanese had captured earlier in the campaign. Three hundred of the enemy's dead and 150 graves were counted, and a large quantity of equipment, weapons, and ammunition-some of it buried-found.29 The Japanese

[344]

made good their escape but they were traveling light.

The exhausted remnants of the 20th Infantry worked their way north slowly, pausing frequently to rest and to bring up the wounded. In the dense foliage and heavy bamboo thickets, the withdrawing elements often lost contact and were forced to halt until the column was formed again. Passing "many enemy positions" in their march north through the American lines, the Japanese on the morning of 15 February finally sighted a friendly patrol.30 About noon Colonel Yoshioka with 377 of his men, all that remained of the 1,000 who had broken through the American line on 29 January, reached the 9th Infantry lines and safety, after a march of four days.

Colonel Yoshioka's 20th Infantry had now ceased to exist as an effective fighting force. Landing in southern Luzon with 2,881 men, the regiment had entered the Bataan campaign with a strength of 2,690. Comparatively few casualties had been suffered in the fighting along the Mauban line. The amphibious operations that followed on 23 January, however, had proved disastrous for Yoshioka. First his 2d Battalion had been "lost without a trace" at Longoskawayan and Quinauan, then the 1st Battalion, sent to its rescue, had been almost entirely destroyed at Anyasan and Silaiim Points. The pocket fights had completed the destruction of the regiment. It is doubtful if the ill-fated 20th Infantry by the middle of February numbered more than 650 men, the majority of whom were sick or wounded.31

With the fight for the Big Pocket at an end, General Brougher turned his attention to the Upper Pocket, the enemy salient at the western extremity of the 11th Division line. All efforts to pinch out the Japanese and restore the main line of resistance had failed. Since its formation on 7 February the salient had been contained by a miscellaneous assortment of troops. On the west were three companies of the 3d Infantry, one from the 1st Infantry, and the remnants of the platoon from Company F, 11th Infantry, which had been overrun in the initial attack. Holding the east side of the .penetration was Company A, 92d Infantry, which Brougher had taken from Jones on the morning of the 7th, and five platoons from the disorganized 12th Infantry. The 2d Battalion, 2d Constabulary, was south of the salient. Not only had this conglomerate force held the Japanese in check, but it had pushed them back about fifty yards before the fight for the Big Pocket ended.

On 13 February Brougher sent forward a portion of the force that had participated in the fight against Yoshioka to join the troops holding back the Japanese in the salient. The 1st Battalion, 45th Infantry, took up a position to the south while the Provisional Battalion, 51st Division, and troops from the 92d Infantry attacked on its left in a northeasterly direction. At the same time, 11th Infantry units and the Constabulary pushed in from the east. By evening of the 14th, despite stubborn resistance and the difficulties presented by the jungle, the salient had been reduced by half and was only 350 yards long and 200 yards wide. An attack from the South the next day cut that area in half.

[345]

The infantry was aided here, as in the Big Pocket fight, by tanks of the 192d Tank Battalion. Hampered by the dense undergrowth and lost in the confusing maze of bamboo thickets, vines, and creepers, the tankers would have been impotent had it not been for the aid of the Igorot troops of Major Duisterhofs 2d Battalion, 11th Infantry. Hoisted to the top of the tanks where they were exposed to the fire of the enemy, these courageous tribesmen from north Luzon chopped away the entangling foliage with their bolos and served as eyes for the American tankers. From their position atop the tanks they fired at the enemy with pistols while guiding the drivers with sticks.32

As a result of these tactics combined with steady pressure from the troops to the southwest and west, the Japanese were slowly pushed back. At least that was what the Americans and Filipinos believed. Actually, it is more likely that the Japanese in the salient were withdrawing to their own lines now that the necessity of providing a diversion for Yoshioka's retreat from the Big Pocket had ended. Once the 20th Infantry survivors had escaped it was no longer necessary for the men in the salient to hold their position. They had accomplished their mission and could now fall back, in accordance with Morioka's orders of the 9th. By the 16th the salient measured only 75 by 100 yards. An unopposed attack the next morning restored the main line of resistance and ended the fight which had begun on 26 January. The fight for the pockets was over.

[346]

Return to Table of Contents

Return to Chapter XVII |

Go to Chapter XIX |

Last updated 1 June 2006 |