CHAPTER VIII

The Main Landings

The first part of Imperial General Headquarters' plan for the conquest of the Philippines had been successful beyond the hopes of the most optimistic. American air and naval power had been virtually destroyed. Five landings had been made at widely separated points and strong detachments of Japanese troops were already conducting offensive operations on Luzon and Mindanao. The 5th Air Group was established on Luzon fields, and the Navy had its own seaplane bases at Camiguin Islands, Legaspi, and Davao. Army short-range fighters were in position to support Japanese ground troops when required. All this had been accomplished in less than two weeks.

The main landings, to be made on Luzon north and south of Manila, were still to come. There would be two landings: the major effort at Lingayen Gulf, and a secondary effort at Lamon Bay. (Map 4) The forces assigned to these landings had begun to assemble late in November. The 16th Division (less the 9th and 33d Infantry) left Osaka in Japan on 25 November and arrived at Amami Oshima in the Ryukyus on 3 December. Three days later all of the 48th Division less the Tanaka and Kanno Detachments) was concentrated at Mako, in the Pescadores, and at Takao and Kirun, on near-by Formosa. The major portion of the shipping units was in Formosa by the end of November and began to load the convoys soon after.

There was much confusion during the concentration and loading period. The greatest secrecy was observed, and only a small number of officers knew the entire plan. These men had to travel constantly between units and assembly points to assist in the preparations and in the solution of detailed and complicated problems. Unit commanders were given the scantiest instructions, and worked, for the most part, in the dark. Important orders were delivered just before they had to be executed, with little time for study and preparation. Such conditions, the Japanese later regretted, "proved incentives to errors and confusion, uneasiness and irritation."1 Moreover, after 8 December, the Japanese lived in fear of an American bombing of Formosa ports, where the vessels were being loaded with supplies and ammunition.

Despite fears, confusions, and mistakes, the separate convoys were finally loaded and ready to sail by 17 December. The uneasiness arising from ignorance and secrecy persisted aboard ship. Even now the men were not told where they were going. Adding to the nervousness was the restriction placed on the use of maps. Only a few officers were allowed to see them. "All the units," the Japanese later observed, "were possessed of a presentiment, arising from the general atmosphere, that they were on their way to a very important theater of operations."2 The 14th Army staff, which did know the destination, shared the nervous-

[123]

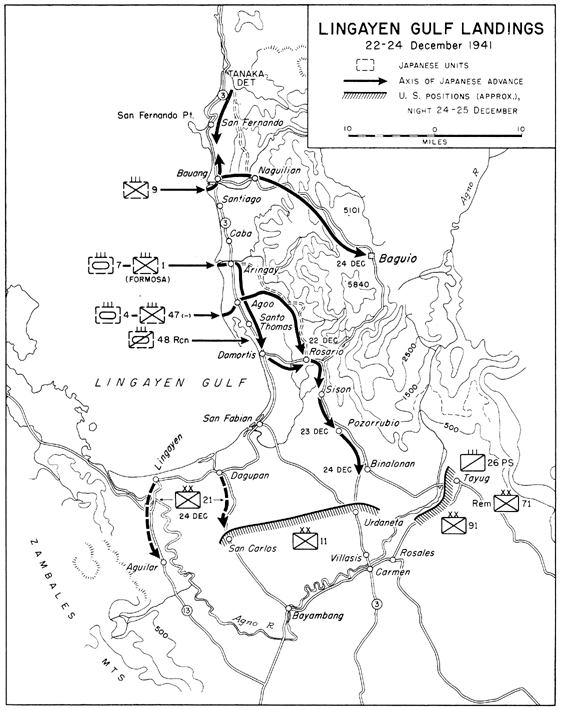

MAP 4

[124]

ness of the troops. Everything depended upon the success of this operation. All that had gone before was but a preliminary to these landings. If they did not succeed, the plans of the Southern Army and of Imperial General Headquarters would fail. "During all my campaigns in the Philippines," said General Homma when he was on trial for his life, "I had three critical moments, and this was number one."3

On the morning of 21 December, Filipinos near Bauang along the shores of Lingayen Gulf observed a Japanese trawler cruising leisurely offshore. Unmolested, it took soundings and then serenely sailed off to the north.4 Late that night, seventy-six heavily loaded Army transports and nine Navy transports, all under strong naval escort, steamed into Lingayen Gulf and dropped anchor. The main assault was on.

The Landing Force

Aboard the transports was the main strength of General Homma's 14th Army, altogether 43,110 men.5 The major combat strength of the Lingayen Force was drawn from Lt. Gen. Yuichi Tsuchibashi's 48th Division. Activated in Formosa in late 1940 and as yet untried in battle, this division was composed of the 1st and 2d Formosa Infantry Regiments, the 47th Infantry, and artillery, reconnaissance, engineer, and transport regiments. Attached to it for the landing was a large number of combat and service units, but the 2d Formosa had been lost by the establishment of the Tanaka and Kanno Detachments. Although probably the best motorized division in the Japanese Army at this time, the 48th by American standards could hardly be said to have sufficient motor transportation. One battalion of each infantry regiment was equipped with bicycles. Divisional artillery consisted of the 48th Mountain Artillery, similar to a standard field artillery regiment except that the basic weapon was the 75-mm. mountain gun (pack).6

[125]

In addition to the 48th Division, the Lingayen Force contained the 16th Division's 9th Infantry, and part of the 22d Field Artillery with 8 horse-drawn 75-mm. guns. Larger caliber pieces were provided by the 9th Independent Field Artillery Battalion (8 150-mm. guns), the 1st Field Artillery Regiment (24 150-mm. howitzers), and the 8th Field Artillery Regiment (16 105-mm. guns). Included in the Lingayen Force were between 80 and 100 light and heavy tanks distributed between the 4th and 7th Tank Regiments.7 A large number of service and special troops completed the force.

The vessels that reached Lingayen Gulf on the night of 21 December were organized in three separate convoys. The first to leave had come from Kirun in northern Formosa and had sailed at 0900 of the 17th. It contained twenty-one transports and had been escorted by the Batan Island Attack Force, which had returned to Formosa after the landing on 8 December.8

The convoy loaded at Mako in the Pescadores, being second farthest from the Philippines, was the next to depart. At noon on 18 December, the twenty-eight transports of this group, accompanied by the Vigan Attack Force, left port. The last convoy left Takao in Formosa at 1700 on the 18th, escorted by the naval force which had supported the Aparri landing.

With each convoy went a large number of landing craft, altogether 63 small landing craft, 73 large ones, and 15 others, which the Japanese called "extra large." In addition, there were 48 small craft, best described as powered sampans. The smallest of the landing craft weighed 3 tons and was apparently used as a personnel carrier. The large landing craft, Daihatsu Model A (Army), was probably the one that saw most service in the Pacific war. Resembling a fishing barge in appearance, it weighed 5 tons, was 50 feet long, was capable of 6 to 10 knots, and had a draft of 3 to 4 feet and a capacity of 100 to 120 men for short hauls.9 The "extra large" landing craft, or Tokubetsu Daihatsu, weighed 7 to 8 tons and was capable of carrying the later model tanks. Its end could be dropped, enabling the tanks to climb in and out under their own power.10

In addition to the direct support provided by the naval escorts with each convoy-altogether 2 light cruisers, 16 destroyers, and a large number of torpedo boats, minesweepers and layers, patrol craft, and miscellaneous vessels-a large naval force led by Vice Adm. Ibo Takahashi, 3d Fleet commander, moved into position to furnish distant cover. On 19 December this force sortied from Mako and sailed to a point about 250 miles west of Luzon. There it was joined by units of Vice Adm. Nobutake Rondo's 2d Fleet, detached from support of the Malayan invasion. Altogether, the Japanese had a force of 2 battleships, 4 heavy cruisers, 1 light cruiser, 2 seaplane

[126]

carriers, and some destroyers in position to meet any Allied naval attempt to disrupt the landing of the Lingayen Force.11

The Plan

The Japanese plan called for landings at three points along the shores of Lingayen Gulf, to begin at 0500 of the 22d.12 Each of the convoys constituted a separate task force and each was to land at a different point. The southernmost landing was to be made by the Takao convoy carrying the 47th Infantry (less one battalion), 4th Tank Regiment (less one company), and supporting elements. This force was to land at Agoo, a small village just inland from the eastern shore of Lingayen Gulf, about five miles north of Damortis. Starting at 0500, the troops, already loaded into the sixty-nine landing craft assigned to this force, were to head for the beach. The first wave was scheduled to touch down at 0540. The round trip time of the landing craft in this wave was to be two hours; thereafter it would be one hour. Altogether each of the craft would make ten round trips during the first day.

The landing craft of the Mako convoy, carrying the 1st Formosa and 7th Tank Regiment, were to move out thirty minutes after the 47th Infantry, and at 0550 would hit the shore at Caba, seven miles north of Agoo. To carry the troops of this force ashore, 57 landing craft and 19 powered sampans were assigned. The third force, consisting of the 9th Infantry and called the Kamijima Detachment, was not to start landing operations until 0700.13 At that time the troops would be loaded into 20 landing craft and 29 sampans and would head for Bauang, about seven miles north of Caba, the first wave reaching shore at 0730. Thus, 14th Army expected to hold a fifteen-mile stretch of beach, from Bauang on the north to Agoo on the south, along the narrow coastal plain between Lingayen Gulf and the Cordillera central range, by 0730 of D Day, 22 December.

The position chosen for the landing was an excellent one. Between the mountains and the shore was a narrow level strip along which ran Route 3, an excellent hard-surface, two-way highway. At Bauang was a road intersecting Route 3 and leading eastward through a mountain defile to Baguio, whence it turned south to join Route 3 again near Rosario. At Aringay, just above Agoo, was a river which formed

[127]

a small valley through the mountains. Through this valley ran a partially surfaced road which led from Aringay to Rosario, one of the key road intersections in this area. South of the landing beaches was the central plain of Luzon. Route 3 opened directly on to the road network leading into Manila.

Once ashore the troops were to destroy any American forces in the vicinity and move inland without waiting to consolidate the beachhead. Later waves would perform that task. The Kamijima Detachment at Bauang was to send one element north to occupy San Fernando, La Union, and another east along the Bauang-Baguio Road, to seize the Naguilian airfield and then press on to Baguio. By seizing Baguio, the Japanese would prevent an American counterattack from the east through the defile. The occupation of San Fernando to the north would effect a consolidation with Colonel Tanaka's force moving south from Vigan and would protect the rear of the Japanese southward advance.

The forces landing at Caba and Agoo were to press south toward Damortis and Rosario. Two roads would be used: the coastal highway to Damortis, and the partially surfaced road which paralleled the Aringay River and led to Rosario. Once at their objectives, these troops were to assemble and "prepare to advance" toward the bank of the Agno River, the first formidable obstacle to a force moving south from Lingayen Gulf to Manila.

The Landing

The voyage of the Lingayen Force to the target was uneventful. In an effort to avoid detection and to create the impression that the destination was Indochina, the transports at first followed a southwesterly course. Only a typhoon in the South China Sea hindered the approach; no American planes or ships appeared.

The combined invasion force was without air cover, such support no longer considered necessary, until the 21st when twenty planes of the 24th and 50th Fighter Regiments, based at Laoag, came out to meet the ships and escort them during the last leg of the journey. At the same time, six light bombers struck Fort Wint on Grande Island at the entrance to Subic Bay, hoping thus to make the real landing site. Between 0110 and 0430 on 22 December, the three convoys, after a slow voyage at an average speed of 8 knots, dropped anchor in Lingayen Gulf.14 The weather was chill, the skies were dark, and an intermittent rain was falling.

At this point things began to go wrong. The convoy leaders, warned against stopping short of their targets, went to the other extreme. The initial anchorage was to have been between San Fernando and the Aringay River, but the lead ship, unable to locate the river in the darkness, overshot the mark, and dropped anchor off Santo Thomas, about four miles south of Agoo. The other transports followed, dropping anchor at intervals over a distance of fifteen miles. As a result, the landing craft now had to make a longer trip than anticipated to reach their designated beaches.15

[128]

Under cover of cruiser and destroyer gunfire, the troops began going over the side shortly after 0200. By 0430 two battalions of the 47th Infantry and one battalion of the 48th Mountain Artillery were in the landing craft, ready to strike out for shore. At 0517 the first troops touched down on the beach south of Agoo. Less than fifteen minutes later, at 0530, the 1st Formosa Infantry, the main strength of the 3d Battalion, 48th Mountain Artillery, and tanks began landing at Aringay, about two miles south of Caba. Two hours later part of the Kamijima Detachment came ashore near Bauang; the rest of the Detachment landed at Santiago, three miles to the south, at 0830.16

The transfer of the troops to the landing craft had proved extremely difficult because of high seas. The light craft were heavily buffeted on the way to shore and the men and equipment soaked by the spray. The radios were made useless by salt water, and there was no communication with the first waves ashore. Even ship-to-ship communication was inadequate. The men had a difficult time in the heavy surf, and it proved impossible to land heavy equipment. The high seas threw many of the landing craft up on the beach, overturning some and beaching others so firmly that they could not be put back into operation for a full day. The northernmost convoy finally had to seek shelter near San Fernando Point, where the sea was calmer. The second wave could not land as planned, with the result that the entire landing schedule was disrupted. The infantry, mountain artillery, and some of the armor got ashore during the day, but few of the heavy units required for support were able to land.

Luckily for the Japanese, they had been able, by skillful handling of the transports, to enter shoal waters before the American submarines could get into action. Once inside, however, the vessels were strung out for fifteen miles, presenting a perfect target for those submarines that could get into the gulf. The S-38 pushed into shallow waters and sank the Army transport Hayo Maru while it was following the gunboats which were preparing to lay mines a few miles west of the anchorage. But on the whole the results obtained by the submarines were disappointing.17

To increase the Japanese worries, four of the B-17's that had come up from Batchelor Field to bomb the Japanese at Davao flew on to Lingayen Gulf and managed to slip through the covering screen of the 24th and 50th Fighter Regiments that morning to strafe the cruisers and destroyers and inflict some damage on the Japanese. Even Admiral Takahashi's cover force, now about 100 miles northwest of Lingayen Gulf, came under attack. PBY's and Army planes went for the flagship Ashigara, mistaking it for the Haruna. Although they scored no hits, the planes reported the Haruna, sunk. The cover force finally slipped away into a rain squall.

Meanwhile, the rising sea had forced many of the Japanese ships to shift anchorage and they moved into the inner bay. There they ran into more trouble when they came into range of the 155-mm. guns of the 86th Field Artillery Battalion (PS). This battalion had two guns at San Fabian and

[129]

155-MM. GUN EMPLACEMENT NEAR DAGUPAN

two at Dagupan, and these apparently opened fire on the southernmost elements of the invasion force. Although claiming to have sunk three transports and two destroyers, the coastal guns actually did no damage except to give General Homma many nervous moments.18

The Japanese landing at Lingayen did not surprise the high command in the Philippines. It was the logical place to land a large force whose destination was Manila. On 18 December G-2, USAFFE, had received information of the movement of a hostile convoy of about eighty transports moving toward the Philippines from the north. This information had been relayed to naval headquarters which already had submarines in the area.19 At 0200 of the 20th, 16th Naval District headquarters reported to USAFFE that a large convoy had been sighted forty miles north of Lingayen Gulf. On the night of 20-21 December, USAFFE, acting on information received, warned the units stationed in that area that a Japanese expedition "of from 100 to 120 vessels" was moving south and could be expected off the mouth of the gulf by

[130]

evening of the 21st.20 The first report of the arrival of the invasion force came from the submarine Stingray which had been on patrol off Lingayen for several days. Before any action could be taken, the landings had begun.

Despite the warning, the Americans seem to have been ill prepared to drive off the invaders. At this time the 120-milelong coast line of Lingayen Gulf was defended by two Philippine Army divisions, only one of which had divisional artillery. The southern edge of the gulf where the landing was expected and where the bulk of the artillery was emplaced, was in the 21st Division sector. The eastern shore, as far north as San Fernando, was held by the 11th Division. The 71st Infantry (71st Division ), with only ten weeks' training, was attached to the 11th Division and posted in the Bauang-Naguilian area. The 26th Cavalry (PS), led by Col. Clinton A. Pierce, had been moved from North Luzon Force reserve at Resales to Pozorrubio on Route 3 about twelve miles south of Rosario, in the path of the Japanese advance.

Only at Bauang were Filipino troops waiting at the beach. Here the Headquarters Battalion, 12th Infantry (PA), with one ,50-caliber and several .30-caliber machine guns, faced the oncoming Japanese. As the Kamijima Detachment approached the shore, the Filipinos took it under fire. The .50-caliber gun caused heavy casualties among the Japanese, but the .30's had dropped out of the action early with clogged firing mechanisms, due to faulty ammunition. Despite the casualties, the Japanese pushed ahead and established a foothold on shore, whereupon the Filipinos withdrew.21

Behind the beach at Bauang was Lt. Col. Donald Van N. Bonnett's 71st Infantry (PA). On the 21st Bonnett had been given orders to halt Colonel Tanaka's 2d Formosa at San Fernando, La Union. One battalion, with a battery of 75-mm. guns (SPM) attached, was to move up the coastal road to meet the 2d Formosa head on. Another battalion was to advance along a secondary road to the east and attack Colonel Tanaka on his left flank. This maneuver, if well executed, might have destroyed the 2d Formosa, but the inexperienced and poorly equipped Filipinos were not capable of a swift and sudden onslaught.22

Before the 71st Infantry could complete its movement the Japanese landed. Patrols from the Kamijima Detachment immediately moved north along Route 3 and at 1100 made contact with a 2d Formosa patrol. By 1400 the main bodies of both units had joined. Meanwhile, Colonel Kamijima's 2d Battalion, 14th Army reserve, had pushed into Bauang immediately after landing and by 1700 had secured the town and surrounding area. The 3d Battalion, in accordance with the plan, moved

[131]

out along the Bauang-Baguio road to the east, toward the Naguilian airfield.

With Colonel Kamijima's 9th Infantry ashore, the position of the 71st Infantry units became untenable. One battalion moved down the coastal road and the other, with elements of the 11th Division, fell back to the east in the face of the Japanese advance. Bonnett's orders now were to withdraw through Baguio to the south, clearing the Philippine summer capital by dark.23

Farther south Col. Hifumi Imai's 1st Formosa and the 48th Mountain Artillery (less 1st and 2d Battalions) had landed at Aringay and by 1030 had concentrated for the advance. Colonel Imai's mission was to move his force south toward Damortis and Rosario. Early in the forenoon the regiment moved out, down the coastal road, and by 1600 the column had joined the 48th Reconnaissance and the 4th Tank Regiments, which had come ashore at 0730, north of Damortis.

The landing at Agoo, where Col. Isamu Yanagi's 47th Infantry with a battalion of the 48th Mountain Artillery had come ashore, was unopposed initially. Without waiting for motor transportation, Colonel Yanagi moved inland toward the Aringay Road, thence south to Rosario. Meanwhile, Brig. Gen. William E. Brougher, 11th Division commander, had sent forward a battalion of infantry to meet the Japanese coming down the coast and, if possible, disrupt the landing at Agoo. By this time the 48th Reconnaissance and 4th Tank Regiments were ashore, and in the brush that followed easily routed the Philippine Army troops who beat a hasty retreat to Damortis.24

Thus, by afternoon of the 22d, the Japanese had pushed ashore elements of three infantry regiments, with supporting artillery and tanks; the main force of the 14th Army was still aboard the transports. Hard fighting lay ahead before the initial objectives of the Lingayen Force would be attained and the Japanese freed from the danger of being driven back into the sea.

Consolidating the Lingayen Beachhead

While his troops at Lingayen were pushing ahead, General Homma remained aboard ship in Lingayen Gulf. He had done all he could in the planning and preparation for the invasion. Now his troops were committed and their failure or success was out of his hands. His anxieties, the lot of any commander during the amphibious stages of an operation, were increased by lack of communications with the men ashore and the confusion caused by high seas and heavy surf. He had no knowledge of the disposition of his troops, moving in many columns in all directions, and no way of controlling the action. He had pushed his infantry and approximately half his armor ashore between Bauang and Agoo, but all the artillery save one regiment was still aboard the transports in the gulf. Cut off from his troop commanders, he had no way to lessen his apprehension by assurances that all was well.

There was some basis for General Homma's fears. The position of the Japanese troops ashore, while generally favorable, might easily become precarious. The landing had been made in a narrow corridor crossed by numerous streams, each of which afforded the defender an opportunity for delaying action. Although the plain to the south provided an excellent route to Manila,

[132]

it could also be used by the Americans and Filipinos as the base for a concerted counterattack against the Japanese as they streamed out of the corridor. A vigorous and well-timed attack by the four divisions of the North Luzon Force, spearheaded by the well trained and equipped Philippine Division in USAFFE reserve, might well "wipe out the invader."25 If, at the same time, sufficient air and naval forces could be mustered to attack the transports and naval escort lying at anchor in the bay, the Japanese line of retreat would be cut and all Homma's achievements and plans brought to naught.

According to the Japanese plan, the troops, once they had landed at Lingayen, were to move on without waiting for the concentration of the entire landing force. But a difference of opinion now arose in 14th Army headquarters. The more cautious staff officers, believing it would be suicidal to proceed with the advance as planned, argued for the establishment of a strong, well-organized beachhead before moving further. Their troops, they reasoned, were at present confined to the long, narrow coastal plain, and the Americans from their positions along the commanding heights to the east might well hold up any Japanese advance long enough to allow General MacArthur to send up his reserves. The results would be disastrous.

The more aggressive wished to execute the original plan. They argued that the American commanders would not risk an offensive in front of the Agno River line. Even if the Americans decided to attack earlier, the bolder 14th Army staff officers felt that the advantages gained from continuing the advance were great enough to justify the risk. If the plan succeeded, the Japanese would gain bridgeheads across the Agno and would be in position to advance rapidly on Manila. Also, it would assure the safety of the beachhead. The views of the more aggressive won out, and General Homma agreed to continue the advance as planned.26

As the first day passed and no word came from the advancing troops, General Homma's fears increased. With no prospect of a calm sea in which to land his artillery and heavy equipment next day, and still fearing an American counterattack, he determined to shift anchorage. At 1730 of D Day he ordered the convoy to move farther south during the night, to a point off Damortis, and continue landing operations there the next day. Fearing artillery fire at the new anchorage, he ordered General Tsuchibashi, the 48th Division commander, to take San Fabian, where there were two 155-mm. guns, thus extending the Japanese drive southward along the Lingayen coast.27

Damortis and Rosario

As the Japanese invasion force made ready to land, the Americans made last minute preparations to meet the attack. USAFFE attached twelve 75-mm. guns on self-propelled mounts to Wainwright's North Luzon Force and ordered the 192d Tank Battalion to his support, but did not place them under his command. Wainwright in turn sent Colonel Pierce's 26th

[133]

Cavalry (PS) from Pozorrubio to Rosario and by 0500 the Scouts were on their way.

While the main body of the 26th Cavalry advanced toward Rosario, the Scout Car Platoon (less detachments) moved ahead quickly to Damortis. When it found the town unoccupied it pushed northward along the coastal road. A few miles to the north the Scout platoon ran into the forward elements of the 48th Reconnaissance and 4th Tank Regiments and fell back to Damortis.

Meanwhile the rest of the 26th Cavalry at Rosario had been ordered to Damortis and directed to hold that town. Upon its arrival the regiment established defensive positions, which would permit a delaying action in the event of a forced withdrawal. At 1300 the cavalrymen came under attack from Japanese ground units supported by planes of the 5th Air Group.

Colonel Pierce, who now had, in addition to his own cavalry, a company of the 12th Infantry and one from the 71st under his command, was hard put to hold his position and called on General Wainwright for help. At about the same time Wainwright received word that an enemy force mounted on cycles or light motor vehicles was approaching Damortis. To meet this emergency, Wainwright requested a company of tanks from Brig. Gen. James R. N. Weaver, the Provisional Tank Group commander.

Because of a shortage of gasoline, Weaver could furnish only a platoon of five tanks from Company C, 192d Tank Battalion. These moved out to the threatened area and near Agoo met the enemy's light tanks. The command tank, maneuvering off the road, received a direct hit and burst into flames. The other four, all hit by 47-mm. antitank fire, succeeded in returning to Rosario but were lost by bombing later in the day. At 1600 elements of the 1st Formosa and 48th Mountain Artillery, which had landed earlier in the day at Aringay joined the attack. Colonel Pierce, finding himself completely outnumbered, withdrew to his first delaying position east of Damortis. By 1900, the Japanese were in complete control of the town.28

Earlier that afternoon Wainwright had attached the 26th Cavalry to the 71st Division and had ordered Brig. Gen. Clyde A. Selleck to take his 71st Division (less 71st Infantry), then at Urdaneta, to Damortis, a distance of about twenty-five miles, and prevent the Japanese from moving south. The 26th Cavalry was to cover the right flank of the 71st Division and hold the junction of the Rosario-Baguio road, east of Rosario, in order to permit Major Bonnett's force, the 71st Infantry (less 1st Battalion), then at Baguio, to clear that point and join the North Luzon Force.

At about 1630 General Selleck, accompanied by the 72d Infantry commander and Lt. Col. Halstead C. Fowler of the 71st Field Artillery, arrived at Rosario, which had by now become the focal point of American resistance. There he learned that Japanese troops were not only approaching from the west along the Damortis road, but also from the northwest where Colonel Yanagi's 47th Infantry was advancing from Agoo along the Aringay River valley. On his way to Damortis, Selleck found Colonel Pierce in his defensive position and learned of the exhausted condition of the 26th Cavalry. Since 71st Division troops had not

[134]

yet come up, he ordered the cavalrymen to fall back slowly on Rosario.

The Japanese by this time had a sizable force advancing along the Damortis-Rosario road. With the 48th Reconnaissance Regiment in the lead and Colonel Imai's 1st Formosa supported by the 48th Mountain Artillery (less 1st and 2d Battalions) forming the main body, the Japanese threatened to overwhelm Colonel Pierce's weary cavalry. The tankers, Company C, 192d, supporting the Scouts, claimed to have orders from General Weaver, the Provisional Tank Group commander, to fall back at 2000 to Rosario, and at the appointed time began to pull out. As the last of the tanks passed through the American lines, the rear guard of the 26th Cavalry was penetrated by Japanese tanks. In the confused action which followed, the Japanese tanks, merged in the darkness with the struggling men and the terrified riderless horses, cut up the defenders and exacted a heavy toll. Only bold action by Maj. Thomas J. H. Trapnell in blocking a bridge over a small river a few miles west of Rosario with a burning tank halted the Japanese and prevented a complete rout.

When the retreating cavalrymen reached Rosario, they discovered that Troop F, which had been defending the trails northwest of the town, had been forced back by Colonel Yanagi's troops. It was now fighting a pitched battle in the town's public square. Fortunately for the Scouts, part of Colonel Yanagi's force had just been detached and ordered back to Agoo for the drive on San Fabian. Troop F held until the rest of the regiment had passed through Rosario. Then it broke off the action and followed, leaving the Japanese in possession. There was no pursuit; the 47th Infantry was content to wait for the 1st Formosa and the tanks, a few miles west of the town on the Damortis road.

Things had gone no better for Major Bonnett's force at Baguio. Busily tracking down rumors of Japanese units approaching in every direction, Bonnett spent the night at Baguio instead of pushing south to Rosario. Lt. Col. John P. Horan, the commander of Camp John Hay at Baguio, kept MacArthur's headquarters informed by radio of Japanese movements in the area and of the predicament of the force under Bonnett.29 A few minutes before midnight of the 22d Horan radioed that the Japanese were "reported in Rosario" and that Bonnett desired "to move south at once if way is clear." "Can you contact Selleck by radio," he asked, "and inform us?"30

Although Horan received no reply, Wainwright, about midnight of the 22d, ordered Pierce to hold the junction of the Baguio and Rosario roads. Bonnett, unaware of this effort and believing that the Japanese held Rosario, remained at Baguio, and the 26th Cavalry finally had to withdraw the next morning when the position became untenable.31 Bonnett later moved east over the mountains into the Cagayan valley, but Horan remained at his post throughout the 23d. The next morning, with the Japanese advancing from all sides, Horan pulled out after sending a final message to MacArthur: "My right hand in a vise, my nose in an inverted funnel, con-

[135]

stipated my bowels, open my south paw. . . ."32 So ended the American occupation of the Philippine summer capital.

Thus, by the end of D Day, the Japanese had secured most of their objectives. They had landed safely along the beaches between Bauang and Agoo, and, pushing north, south, and east, had seized the defiles through the mountains, effected a juncture with Colonel Tanaka's force, and occupied Damortis and Rosario. The Japanese were now in position to debouch on to the central plain. Only their inability to get artillery and supplies ashore marred the day's success.

All the honors in the first day's fight had gone to the Japanese. Only the Scouts of the 26th Cavalry had offered any serious opposition to the successful completion of the Japanese plan. The untrained and poorly equipped Philippine Army troops had broken at the first appearance of the enemy and fled to the rear in a disorganized stream. Many of them, moving back along the coastal road, had passed through the 21st Field Artillery command post at the bend of the gulf. Col. Richard C. Mallonée, American instructor with the regiment, thought, "Their presence presages disaster." Although he reorganized them and sent them back to division headquarters, few of them, he felt sure, ever arrived. Their stories were always the same.

Always they were subjected to terrible, horrible mortar fire. Always the storyteller continued to bravely fire his rifle, machine gun or 75, as the case might be; always their officers ran away-or if the teller is an officer, then his superior officers ran first; always the enemy planes dropped many bombs and fired many machine guns; always there suddenly appeared many hostile tanks, headed straight for him; always he was suddenly surprised and astonished to realize that he was absolutely alone, all the others having been killed, or- despicable cowards-ran away. Then and only then, with the tanks a few feet away had he flung himself to one side where-and there the story has two variations, first he is captured but escapes that night; second he hides until night when he returns to our lines-but doesn't stop there. But from there on the threads of the story re-unite; they are very tired, they seek their companions, they are very hungry, and, Sir, could they be transferred to the Motor Transport Corps and drive a truck.33 |

The Approach to the Agno

The morning of 23 December found the 71st Division (less 71st Infantry) in position astride Route 3 south of Sison, the 72d Infantry and the 71st Engineers in the front lines, with the 71st Field Artillery in support to the rear. The 26th Cavalry, which had suffered heavily, was under orders to fall back through the 71st Division line to Pozorrubio to reorganize. The 91st Division, USAFFE reserve at Cabanatuan, had been attached to the North Luzon Force, and its 91st Combat Team had been ordered north to reinforce the 71st Division. It was to arrive at noon and occupy a position north of Pozorrubio, along the road leading south from Rosario.

The action on the 23d opened when two battalions of the 47th Infantry, moving south from Rosario, struck General Selleck's line near Sison. Largely because of Colonel Fowler's artillery, the Japanese advance was held up until noon. During the early afternoon the 47th Infantry was joined by the 48th Reconnaissance and 4th Tank Regiments. Aided by planes of the 10th

[136]

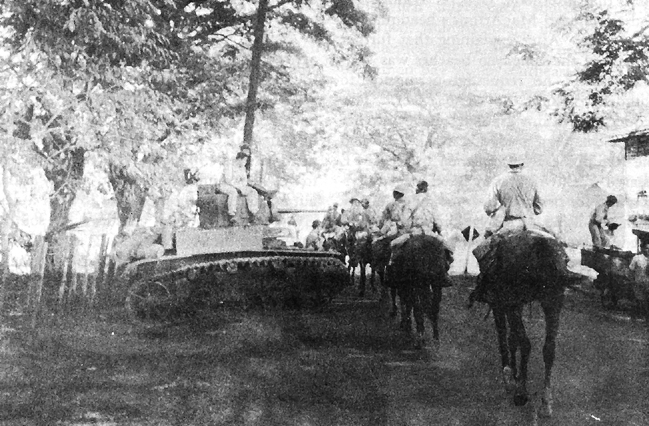

26TH CAVALRY (PS) MOVING INTO POZORRUBIO pass a General Stuart light tank, M3.

Independent and 16th Light Bombardment Regiments, the Japanese now began a concerted attack.

The Filipinos of the 71st Division, like those of the 11th, broke and fled to the rear, leaving the artillery uncovered. The line might have held if the 91st Combat Team, en route from Cabanatuan, had reached Sison in time. But the 91st had run into bad luck. Japanese light bombers ranging far in advance of the ground troops had knocked out a bridge across the Agno River in the path of the 91st advance. The 91st Combat Team was forced to detour and at this critical moment was far from the scene of combat.

The situation was serious. A meeting of the American commanders was hastily called and it was agreed that the 71st Division would have to withdraw to a line just north of Pozorrubio. The 91st Combat Team, it was hoped, would reach that place in time to set up a line there. The 26th Cavalry in 71st Division reserve at Pozorrubio was to retire to Binalonan where it would set up an outpost line through which the remainder of the division could fall back if necessary.

At 1900, as the Japanese entered Sison, the 26th Cavalry began to move out toward Binalonan and the 91st Combat Team reached Pozorrubio. That night the enemy attacked the 91st and drove it out of the town. With its rout, all hopes of holding a line at Pozorrubio came to an end.

Even before the Japanese had entered

[137]

Sison that afternoon, General Wainwright had telephoned MacArthur's headquarters at Manila. After explaining that further defense of the Lingayen beaches was "impracticable," he requested permission to withdraw behind the Agno River. This request was readily granted. Believing that he could launch a counterattack if he had the Philippine Division, then in USAFFE reserve, Wainwright also asked for the division and for permission to mount an attack from the Agno. He was directed to submit his plans. "I'll get my plans there as soon as possible," he replied, but asked for an immediate answer on whether he would get the Philippine Division. After a slight delay, he was told that his chances of securing the division were "highly improbable." Nevertheless he began to make his plans for a counterattack.34

The action of 24 December placed the Japanese in position for the final drive toward the Agno River. At about 0500, with the 4th Tank Regiment in the lead, the Japanese made contact with the 26th Cavalry outposts north and west of Binalonan. Although the Scouts had no antitank guns, they were able to stop the first attack. The tanks then swung west to bypass the American positions, leaving the infantry to continue the fight for Binalonan. By 0700 the 26th Cavalry had blunted the assault and inflicted many casualties on the enemy. Pursuing their advantage, the Scouts counterattacked and the Japanese had to send in more tanks to stop the 26th Cavalry. Even with the aid of tanks, the Japanese made no progress. Sometime during the morning the 2d Formosa joined the attack, and the cavalrymen found themselves in serious trouble. Too heavily engaged to break off the action and retire, they continued to fight on.

At this juncture, General Wainwright arrived at Binalonan to see Selleck. He found neither General Selleck, who had gone to Wainwright's command post to report, nor any 71st Division troops, but did find the 26th Cavalry, which now numbered no more than 450 men. He ordered Pierce to get his wounded men and supply train out as quickly as possible and to fight a delaying action before withdrawing southeast across the Agno to Tayug. For more than four hours the cavalrymen held their position against overwhelming odds, and at 1530 began to withdraw. By dusk the last elements had reached Tayug and the 2d Formosa entered Binalonan. "Here," said General Wainwright, himself a cavalryman, "was true cavalry delaying action, fit to make a man's heart sing. Pierce that day upheld the best traditions of the cavalry service."35

Despite the heroic struggle by the 26th Cavalry, the Japanese had secured their initial objectives and had established a firm grip on northern Luzon. They were now in position to march south to Manila along the broad highways of the central plain of Luzon. Only the southern route to the capital remained to be seized. That task was the mission of the Lamon Bay Force, already moving into position.

Simultaneously with the departure of the Lingayen Force from Formosa, Lt. Gen. Susumu Morioka, 16th Division commander, had left Amami Oshima in the Ryukyus on 17 December to begin his six-

[138]

day voyage southward to Lamon Bay, 200 road miles southeast of Lingayen. With the landing of his force, the Japanese plan to place troops in position to attack Manila from the north and south would be complete.

Organization and Preparation

The Lamon Bay Force had a secondary role in the seizure of Luzon and was consequently much smaller than the Lingayen Force. Its combat elements consisted primarily of General Morioka's 16th Division (less the 9th and 33d Infantry and some supporting elements) and numbered 7,000 men. In addition, it contained a number of attached service and supporting units. General Homma did not expect much from this force; in his opinion, the 16th Division, which had seen action in China, "did not have a very good reputation for its fighting qualities."36

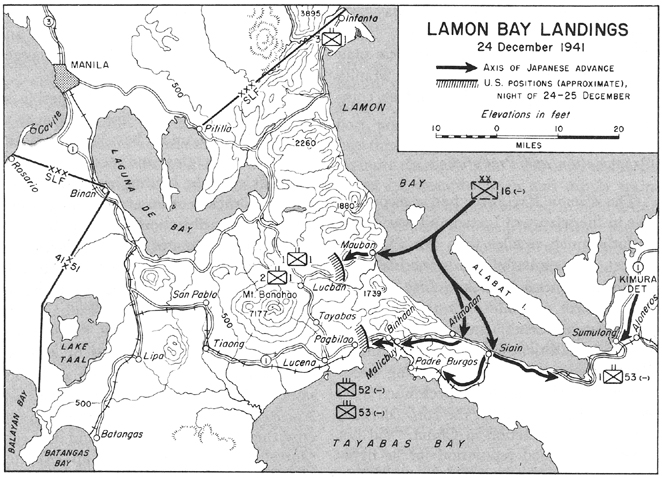

The plan for the Lamon Bay landing had been prepared during November, while the division was still in Japan. The original objective had been Batangas Bay on the southwest coast of Luzon, where the beaches were suitable for landings and where a direct route led through favorable terrain toward Manila to the north.37 (Map 5) But when the number of aircraft assigned to the Philippine operation was reduced, and when intelligence sources reported American reinforcements in bombers and submarines, the target had been changed to Lamon Bay on the southeast coast.

The new landing site was undesirable on two grounds. First, the line of advance to Manila from Lamon Bay lay across the Tayabas Mountains, and secondly, Lamon Bay offered poor landing sites during the winter months because of prevailing winds. Despite these objections, Lamon Bay was chosen as the target of the 16th Division.

The final plan developed by Morioka called for landings at three points along the shore of Lamon Bay-at Mauban, Atimonan, and Siain. General Morioka expected to take the Americans by surprise, but was ready, if necessary, to make an assault landing. His troops were to rout any American forces on the beaches, rapidly cross the Tayabas Mountains, and then concentrate in preparation for an expected counterattack. In order to avoid congestion on the narrow beaches and during the crossing of the mountains, the troops were to move ahead rapidly in several columns immediately after landing, without waiting for supporting troops or for the consolidation of the beachhead. The main force of General Morioka's division was to advance west along Route 1, then sweep around Laguna de Bay to drive on to Cavite and Manila from the south.

The force scheduled to land at Mauban was the 2d Battalion, 20th Infantry, and a battery of the 22d Field Artillery under Lt. Col. Nariyoshi Tsunehiro. After landing, it was to strike out to the west to Lucban, where it would be in position to move southeast to support the Atimonan force. If such support proved unnecessary, Tsunehiro was to turn northwest to Laguna de Bay, skirt

[139]

MAP 5

the southern shore, then strike north along Route 1 to Manila.

The main force of the 16th Division, under direct command of General Morioka, was to make the assault on Atimonan. Included in this force were the 20th Infantry (less than 2d and most of the 1st Battalion); the 16th Reconnaissance Regiment, with one company of light armored cars; the 16th Engineers; and the 22d Field Artillery (less 2d Battalion and one battery of the 1st). Once ashore, these troops were to move west across the mountains along Route 1, then north along the shore of Laguna de Bay and on to Manila. American troops and positions encountered along the way were, so far as possible, to be bypassed and mopped up later. The main advance was not to be held up.

Simultaneously with the landing at Atimonan, the 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry (less one company), with artillery support, was to land near Siain to the south, and cover the left flank of the main force. Having fulfilled this mission, the Siain force was to pass into division reserve.

The 24 transports carrying the invasion force left the staging area at Amami Oshima in the Ryukyus at 1500 on 17 December, six hours after the first Lingayen convoy pulled out of Kirun Harbor in northern Formosa. The transports were escorted ini-

[140]

tially by 4 destroyers and 4 minesweepers, but they had not gone far before they were joined by Rear Adm. Kyuji Kubo's force of 1 light cruiser, 2 destroyers, 2 minesweepers, and 1 minelayer from Legaspi.

The voyage from Amami Oshima was smooth and uneventful until the 23d, when the American submarine Sculpin forced the convoy to adopt evasive tactics. No damage was caused. At 0130 of the following morning, after the Lingayen Force had already been ashore for two days, the transports dropped anchor in Lamon Bay. An hour later the troops were ready to move to shore.38

The Landing

From the American point of view, the Japanese could not have landed at a more inopportune moment. Maj. Gen. George M. Parker's South Luzon Force was badly dispersed. The 41st Division (PA) on the west coast was in position, but elements of the 51st Division along the east coast were in the process of movement. The South Luzon Force had been reinforced during the past few days by the recently inducted 1st Regular Division (PA), but only the 1st Infantry of this division had actually moved into the area. Its orders were to relieve the 3d Battalion, 52d Infantry, north of Mauban. By evening of the 23d the relief had been accomplished, and one battalion of the 1st Infantry was in position at Mauban, another at Infanta; the remaining battalion was in reserve at a road junction northeast of Lucban. This move had just been completed when MacArthur's headquarters transferred the 1st Infantry to North Luzon Force. General Parker-and General Jones-protested the order vigorously, and it was finally rescinded, but the movement of the 3d Battalion, 52d Infantry, was in progress when the enemy landed.

That same evening the 51st Division troops, who had moved south to delay the movement northward of the Kimura Detachment from Legaspi, were pulled back and were in the process of moving when the Japanese landed. The results for them were more tragic; many of them were cut off and never returned to the American lines.

Not only were the forces along the east coast dispersed at the moment of the landing, but those units in position were handicapped by the absence of artillery. The South Luzon Force included two batteries of the 86th Field Artillery with 6 155-mm. guns, and a battalion of 16 75-mm. guns on self-propelled mounts. But none of these pieces were emplaced in the Lamon Bay area. They were all on the west coast-at Batangas, Balayan, and Nasugbu Bays. General Jones had requested that at least 2 of the 155-mm. guns be moved to Atimonan, and Parker, concerned over this lack of artillery along the east coast, had twice asked MacArthur's headquarters for additional artillery. Both times he had been turned down, despite the fact that he used "the strongest arguments possible."39

The failure to move some of the guns from the west coast to Lamon Bay, especially after the Japanese landing at Legaspi, can be explained only by the fact that MacArthur's headquarters feared to uncover the west coast beaches which offered a direct route to Manila across favorable terrain.

[141]

By accepting the difficulties of a Lamon Bay landing, the Japanese unconsciously gained a great advantage.

Thus, during the night of 23-24 December, as the Japanese were loading into the landing craft, the Lamon Bay area was without artillery support and was the scene of confusion, with several units in the process of movement from one place to another. Fortunately, the 1st Battalion, 1st Infantry, was in position at Mauban, and Headquarters and Company A of the 1st Battalion, 52d Infantry were at Atimonan.

News of the approach of the Japanese reached the defenders at 2200 on the night of the 23d, when the transports off Atimonan were sighted. Four hours later troops were reported debarking there and at Siain. First word of a landing at Mauban was received by General Jones of the 51st Division at 0400. All these reports greatly overestimated the strength of the Japanese force. The Atimonan force was thought to be a reinforced division, and the troops coming ashore at Mauban were estimated as a reinforced brigade.

Under cover of aircraft from the seaplane carrier Mizuho, Colonel Tsunehiro's 2d Battalion, 20th Infantry, came ashore at Mauban, northernmost of the three landing sites, in the first light of dawn. Immediately it ran into an effective crossfire from the 2d Battalion, 1st Infantry, dug in along the beach. At about this time, American planes struck the Japanese, inflicting heavy casualties on the troops and causing considerable damage to the ships.40 By 0800, after much heavy fighting, the Philippine Army regulars had been pushed back into Mauban. Thirty minutes later Colonel Tsunehiro's troops were in control of the village. The 2d Battalion, 1st Infantry, fell back five miles to the west, where it set up a defensive position. At 1430 the Japanese reached this position and there the advance came to a halt before the stubborn defense of the Filipinos.

The 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry, landed at Siain without difficulty. At 0700 one company moved out to the southwest along the Manila Railroad toward Tayabas Bay while the rest of the battalion pushed southeast on Route 1 to effect a juncture with General Kimura's troops moving northwest. Both columns made satisfactory progress during the day. By evening the company moving toward Tayabas Bay was within five miles of Padre Burgos. The rest of the force ran into sporadic opposition from Colonel Cordero's 52d Infantry troops in the Bicol Peninsula, and it was not until three days later that the 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry, joined with the Kimura Detachment.

General Morioka's main force came ashore on the morning of 24 December about two and one half miles southeast of its. target. The first troops landed were held up by Company A, 52d Infantry. The next wave containing the 16th Reconnaissance Regiment, landed beside the infantry but avoided action by moving off to the side, in accordance with instructions not to delay the main advance. The regiment then

[142]

LT. GEN. MASAHARU HOMMA, 14TH ARMY COMMANDER, coming ashore at Lingayen Gulf,

24 December 1941.

struck off into the mountains, bypassing Atimonan. The town itself was secured by 1100, although the Philippine Army troops fought stubbornly.

The 16th Reconnaissance Regiment pushed along Route 1 toward Malicbuy, where the 2d Battalion, 52d Infantry, was frantically setting up defensive positions. Planes of the 8th Air Regiment (light bombers) provided cover for the advancing Japanese and attacked Malicbuy several times during the morning, destroying a number of vehicles and impeding the efforts of the troops to establish an adequate defense. When the 16th Reconnaissance reached the town, the 2d Battalion, 52d Infantry, already weakened by air attacks, fell back after a short fight. The Japanese entered Malicbuy without further interference.

The American forces set up their next defensive position along a river near Binahaan, about four miles to the west. Here they were joined by the 53d Infantry (less two battalions) and the 3d Battalion (less one company) of the 52d Infantry. Late in the afternoon, when the Japanese at Atimonan had completed mopping-up operations in the town, they joined the main body at Malicbuy. The entire force then struck the delaying position at Binahaan. Under cover of darkness the defenders withdrew

[143]

along Route 1 toward Pagbilao, the next objective of the 16th Division.41

By the evening of 24 December the Japanese had successfully completed the first and most difficult part of their plan for the conquest of the Philippines. In the south, at a cost of 84 dead and 184 wounded, General Morioka had landed his reduced division of 7,000 men. American resistance had held up the advance of some units, but the main force of the 16th Division had swept ahead, with the armored cars of the 16th Reconnaissance in the van. Unloading had progressed satisfactorily, and many of the service and supporting units had already landed. The roads leading westward through the Tayabas Mountains had been secured, and the troops of the Lamon Bay Force were in position to reach Tayabas Bay the following morning. General Homma had not expected much from this force. Its success came, therefore, as "quite a surprise" to 14th Army headquarters at Lingayen Gulf, and, as the Japanese later confessed, "The result realized was more than expected."42

North of Manila the Lingayen Force stood ready to drive on to the Agno River. After several days of difficulties, the beachhead had been organized and heavy supplies and equipment brought ashore. San Fabian to the south had been occupied and the American artillery there driven out. The north and east flanks of the coastal corridor had been secured, and Japanese troops were pouring out on to the central plain to add their weight to the advance on Manila, 100 miles away. That day, 24 December, General Homma brought his staff ashore at Bauang, where he established 14th Army headquarters. The Japanese were evidently in the Philippines to stay.

[144]

Return to Table of Contents

Return to Chapter VII |

Go to Chapter IX |

Last updated 1 June 2006 |