CHAPTER XV

The German Salient Expands to the West

The reaction of rifle companies and battalions to the German surprise attack on the morning of 16 December was an automatic reflex to an immediate threat. The speed of reaction in higher American headquarters was appreciably slower since the size of the enemy threat and its direction could be determined only when the bits and pieces of tactical information, ascending the command ladder echelon by echelon, began to array themselves in a credible manner. The fact that the German High Command had chosen to make the main effort on the north flank contributed to an early misreading of the scope of the attack, for in this sector of the Allied line there were two possible German military objectives which were tactically credible and compatible with the Allied preconception of a limited objective attack. These were, first, a spoiling operation to neutralize the gains of the 2d and 99th Infantry Divisions in the advance into the West Wall, and, second, a line-straightening operation to reduce the salient held by the 106th Infantry Division within the old West Wall positions. Either or both of these interpretations of the initial German effort could be made and would be made at corps and higher headquarters during the 16th.

The chain reaction during the early hours of the attack followed two paths, one via Gerow's V Corps and the other via Middleton's VIII Corps. The first report of enemy action on the 16th seems to have come to Gerow from the 102d Cavalry Group in the Monschau sector. The second report reaching V Corps was initiated by the 393d Infantry and was circumstantial enough to indicate a German penetration on the front of the 99th Division. By noon Gerow had sufficient information to justify a corps order halting the attack being made by the 2d and 99th. Although the First Army commander subsequently disapproved Gerow's action and ordered a resumption of the advance for 17 December, the American attack in fact was halted, thus permitting a rapid redeployment to meet the German thrust. Gerow's decision seems to have been taken before V Corps had any certain word from the 394th Infantry on the corps right flank. Neither Gerow nor Middleton was given prompt information that contact between the 99th Division and the 14th Cavalry Group had been broken at the V-VIII Corps boundary.

Since Middleton's corps had been hit on a much wider front than in the case of its northern neighbor, a somewhat better initial appreciation of the weight of the attack was possible. Even so, Middleton and his superiors had too little precise information during most

[330]

of the 16th to assess the German threat properly. Middleton seems to have felt intuitively that his thinly held corps front was being hammered by something more serious than local and limited counterattacks. By 1030 he had convinced General Hodges that CCB, 9th Armored Division, should be taken out of army reserve and turned over to the VIII Corps, for he had no armor in reserve behind the corps left flank. Shortly after noon telephone conversations with his corps liaison officers at the 106th headquarters in St. Vith convinced Middleton that he had to be ready to commit his own available corps reserves, four battalions of combat engineers and CCR, 9th Armored Division. By 1400 the 168th Engineer Combat Battalion was assembling at St. Vith and within the next few hours the remaining engineers and CCR were alerted and assembled, the latter moving up behind the corps center where, Middleton learned at 1415, all regiments of the 28th Division were under attack.

The sequence of events in the hours before midnight on the 16th is difficult to time. Middleton talked with the commander of the 106th Division by telephone and apparently believed that he, Middleton, had sanctioned a withdrawal of Jones's exposed two regiments and that such a withdrawal would be made.1 Impressed with the growing strength of the German attack, Middleton drafted a "hold at all costs" order which left his command post at 2120 and which set the final defense line generally along the west bank of the Our, Clerf, and Sure Rivers. General Bradley, whose 12th Army Group headquarters in Luxembourg City had a better telephone link to the VIII Corps than had the First Army command post at Spa, talked with Middleton, then telephoned General Patton that the 10th Armored Division would have to come north to help Middleton's corps. At midnight General Hodges ordered the 26th Infantry attached to V Corps and set it marching for Camp Elsenborn. About the same time Hodges alerted part of the 3d Armored.

It is unlikely that the responsible American commanders slept soundly on the night of the 16th, but as yet they had no real appreciation of the magnitude of the enemy attack. The tactics followed by the Germans in the first hours had made it very difficult for even the front-line commanders to gauge the threat. The disruption of the forward communications nets by German shellfire on the morning of the 16th had led to long periods of silence at the most endangered portions of the front and a subsequent overloading, with consequent delays, of those artillery radio networks which continued to function. The initial enemy employment of small assault groups, company-size or less, had led the combat commanders on the line to visualize and report a limited-scale attack. The broken and wooded nature of the terrain in the area under attack had permitted extensive German infiltration without any American observation, which also contributed to an erroneous first estimate of the enemy forces. Finally, the speed with which the American observation or listening posts were overrun and silenced had resulted

[331]

in large blank spaces on the G-2 maps in the American headquarters.

At the close of this first day of battle, therefore, the only certain view of the enemy was this: German forces were attacking all along the line from Monschau to Echternach; they had succeeded in making some dents in the forward American positions; at a number of points the defenders seemed to need reinforcement; and the amount of German artillery which had been used was suspiciously large for only a limited objective attack. During the night of 16 December the German assault waves overran or destroyed a large number of communications points and much radio or wire equipment in the forward areas, drastically slowing the flow of information to higher American headquarters.

To many American units 17 December opened as just another day. Company B of the 341st Engineer General Service Regiment, for example, went that morning to work on a railroad bridge under construction at Butgenbach. (Before noon the surprised engineers were shelled out.) As the morning progressed, however, the higher American headquarters began to comprehend that the enemy was making a full-scale attack and this with no limited objective in mind. By 0730 the V Corps commander had sufficient information to convince him that the enemy had broken through the lines of the 99th Division. At 0820 the VIII Corps artillery radio reported to Middleton that German troops were approaching St. Vith along the Schönberg] road. Two hours later the American command nets were jammed with Allied air force reports of large enemy vehicular columns moving westward. Even more significant was the fact that the fighter-bomber pilots were having to jettison their bomb loads in order to engage increasingly large flights of German planes.

Two other key pieces helped fill out the puzzle picture of enemy forces and intentions. Prisoners had been taken from a number of units known to belong to the Sixth Panzer Army, a formation long carried in Allied G-2 estimates as the German strategic reserve in the west. Second, some ninety Junker 52's had been counted in the early morning paratroop drop, an indication that the Germans had planned a serious airborne assault. By late morning of the 17th, therefore, it can be said that the American commanders had sufficient information to construct and accept a picture of a major German offensive. It would take another thirty-six hours to produce a really accurate estimate of the number of German divisions massing on the Ardennes front.

The 12th Army Group commander, General Bradley, had gone to Paris to discuss the replacement problem with General Eisenhower, when, on the afternoon of the 16th, a message from his own headquarters in Luxembourg City gave word of the German attack. Eisenhower suggested that Bradley should move the 7th Armored Division down from the north and bring the 10th Armored Division up from the Third Army. The 12th Army Group had no strategic reserve, but plans already existed to move troops in from Patton's Third Army and Simpson's Ninth in the unlikely event that the undermanned VIII Corps front was threatened. Bradley telephoned Patton and told him to send the 10th Armored Division north to help Middleton. Patton, as Bradley

[332]

expected, demurred. His own army was readying for a major attack on 19 December, an attack which had been the subject of controversy between Eisenhower and Montgomery and which represented the Third Army's last chance to be the chief ball carrier in the Allied push to cross the Rhine. Bradley, however, was firm and Patton at once gave the order to assemble the 10th Armored.

Bradley's second call went to General Simpson whose grueling attack to close along the Rhine River had come to a halt on 14 December beside the muddy western banks of the Roer. Here the choice fell, as Eisenhower had suggested, on the 7th Armored Division, which was resting and refitting in the rear of the XIII Corps zone. The 7th was turned over to the First Army and now Bradley had a fresh armored division moving in to shore up each of the endangered VIII Corps flanks. More troops, guns, and tanks would be moved out of Simpson's army on 16 and 17 December, but the authorization for these reinforcements is hard to trace. In many cases the transfer of units would be accomplished in simple fashion by telephone calls and simultaneous agreement between the higher commanders concerned.2 Hodges and Simpson had been comrades in World War I, and when Hodges asked for assistance Simpson acted promptly and generously. On the 16th, for example, Simpson offered the 30th Infantry Division and the 5th Armored on his own initiative.

Prior to the invasion of Normandy there had been a great deal of staff planning for the creation of a SHAEF strategic reserve for use in the first ninety days of the operation in western Europe. The Allied successes during the summer and autumn put these plans in moth balls and the subject was not reopened until early December when Eisenhower ordered that a strategic reserve be assembled and placed under the 12th Army Group, but for employment only at his direction as Supreme Allied Commander. Two days before the Ardennes attack the SHAEF operations section submitted a plan calling for a strategic reserve of at least three divisions. The concept, quite clearly, was to amass a force capable of exploiting a success on any sector of the Allied front without diverting divisions from other parts of the front. Some operations officer, possibly imbued with the Leavenworth doctrine of "Completed Staff Work," inserted the observation that "a strategic reserve could be used to repel a serious breakthrough by German forces," but hastened to add: "In view of current G-2 estimates, it is unlikely that such employment will become necessary." 3

To understand fully the position in which the Supreme Commander found himself on 16 December, it should be

[333]

remembered that American troops were in constant movement to Europe and the higher staffs tended to look upon the next few troopships as containing a reserve which could and would be used by the Supreme Commander to influence the direction of the battle. Four U.S. infantry divisions and one armored division were scheduled to arrive on the Continent in December, with an equal number slated for January. Of the December contingent two infantry divisions (the 87th and 104th) were already in the line when the Germans struck. There remained en route the 11th Armored Division and the 66th and 7th Infantry Divisions, the 75th having already crossed the Channel on its way to the front. Two additional US divisions were training in the United Kingdom and waiting for equipment, but neither was expected to cross the Channel during December: the 17th Airborne was scheduled for France in January, and the 8th Armored Division, still missing many of its authorized vehicles, was not as yet on a movements list.4

The only combat-wise divisions ready to the hand of the Supreme Commander were the 82d and 101st Airborne Divisions, which had been brought back to France after the long, tough battle in the Netherlands and were not expected to regain full operational status until mid-January. By the 17th, however, it was clear that the First Army had to be heavily reinforced, and promptly. General Eisenhower reluctantly gave the airborne troops to Bradley.

From this point on the immediate reinforcements needed to meet and halt the German counteroffensive would have to come from the armies in the field. (Simpson had already thrown the 30th Infantry into the pot, in addition to the 7th Armored.) Late in the evening of the 17th Bradley telephoned Patton, who was starting to move his troops into assembly areas for the Third Army attack on the Saar, and told the latter that two more divisions might have to go north. By midnight of 17 December approximately 60,000 men and 11,000 vehicles were on the move to reinforce Hodges' First Army. In the following eight days three times this number of men and vehicles would be diverted from other areas to meet the Germans in the Ardennes.

One piece of military thinking dominated in all the higher US military headquarters and is clearly traceable in the initial decisions made by Eisenhower, Bradley, and the army and corps commanders. The Army service schools during the period between the two World Wars had taught as doctrine- a doctrine derived from the great offensives of 1917 and 1918 on the Western Front-that the salient or bulge produced by a large-scale offensive can be contained and finally erased only if the shoulders are firmly held. The initial movements of the American reinforcements were in response to this doctrine.

The 30th Division Meets Peiper

The 30th Division (Maj. Gen. Leland S. Hobbs) was resting in the neighborhood of Aachen, Germany, after hard fighting in the Roer River sector, when a call from the XIX Corps informed its commander of the German attack along

[334]

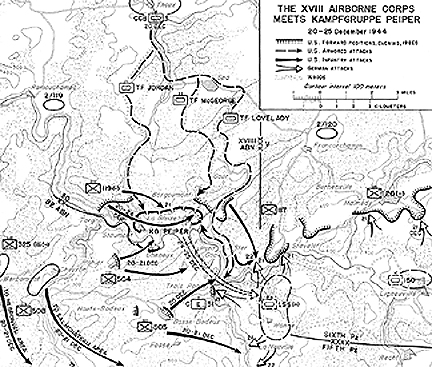

the V and VIII Corps boundary.5 At this time (the evening of 16 December) the situation did not seem too ominous and the division commander merely was told that he should alert his units in the rest area. Shortly before noon of the following day the corps commander, Maj. Gen. Raymond S. McLain, telephoned to say: "I don't know any of the details but you are going south. I think it is only temporary." The 30th Division was to move to an assembly area north of Eupen where the V Corps commander, General Gerow, would issue detailed orders. Gerow's instructions, actually received at noon, directed the 30th Division to relieve the 18th Infantry (1st Division) around Eupen and prepare for a counterattack to the southeast in support of the 2d and 99th Divisions farther south. The rapid advance of Kampfgruppe Peiper, however, would catch the division in midpassage, drastically changing the manner of its ultimate commitment. (See Map II.)

At 1630, on 17 December, the division started the forty-mile trip to its new assembly area moving by combat teams prepared to fight. The 30th Reconnaissance Troop, the 119th Infantry, 117th Infantry, and 120th Infantry moved in that order, with tanks and tank destroyers interspersed between the regiments. Despite the presence of a few German aircraft which picked up the column early in the move and hung about dropping flares or making futile strafing passes, the leading regiment closed by midnight. Meanwhile the V Corps commander, apprehensive lest the 1st SS Panzer Division column thrusting south of Malmédy should destroy the last connection between his own and the VIII Corps, ordered General Hobbs to switch his leading combat team to Malmédy at daylight.

Since the 119th had detrucked and bedded down for the night, the assistant division commander, Brig. Gen. William K. Harrison, Jr., caught the 117th Infantry on the road and directed it toward Malmédy. Its way fitfully lighted by enemy flares, the 117th (Col. Walter M. Johnson) moved cautiously south from Eupen. In early morning the head of the regimental column was bucking the heavy stream of traffic leaving Malmédy when new orders arrived: one battalion was to go to Stavelot, erect a roadblock, and prevent the Germans from advancing north of the Amblève River. Colonel Johnson hurried his 1st Battalion toward Stavelot, deployed the 2d Battalion on the ridge between Stavelot and Malmédy, then organized the defense of Malmédy with the 3d Battalion and the troops already in the town.

At daybreak on 18 December the remainder of the 30th Division was on the road to Malmédy with the 120th Infantry in the lead, under new orders for a division attack to the southeast. The V Corps G-3 had told General Hobbs that he expected this attack to be made not earlier than 19 December. But the German attack on Stavelot during the morning caused consternation

[335]

in both the corps and army headquarters, from which erupted a stream of orders and demands for greater speed. Harassed by confusing and contradictory directions, Hobbs finally had to ask that he be given orders from but one source. As it was, the 119th Infantry, still in Eupen, was alerted for Stavelot while the 120th Infantry, painfully slipped and slid along the muddy roads to Malmédy. Before trucks could arrive for the 119th Infantry Stavelot had fallen to the enemy. The First Army commander called Hobbs to Spa about noon. Before leaving Eupen, General Hobbs instructed the 119th Infantry (Col. Edward M. Sutherland) to meet him at Theux, five miles north of Spa, at which time he expected to have new orders.

General Hodges had just finished a conference with the acting commander of the XVIII Airborne Corps, Maj. Gen. James M. Gavin, whose two divisions, the 82d and 101st Airborne, had started advance parties from France for the Bastogne area where, according to the initial orders from SHAEF, the divisions were to be employed. The First Army commander, under whose orders the XVIII Airborne Corps now fell, determined to divert the 82d Airborne Division to Werbomont as a backstop in case Kampfgruppe Peiper succeeded in crossing the Amblève and Salm Rivers. The 82d, however, would not be in position before 19 December at the earliest. Meanwhile the 30th Division commander reached the First Army headquarters. In the midst of a discussion of new plans, word came in that the First Army liaison planes scudding under the clouds had seen the German armor moving north from Trois Ponts in the direction of La Gleize and Stoumont. It was apparent that the enemy had two choices: he could continue north along the Amblève valley, thus threatening the rearward installations of the First Army; or he could turn west toward Werbomont and so present a grave menace to the assembly of the 82d. Hobbs, then, met Colonel Sutherland with First Army orders which would split the 119th Infantry, sending one force along the valley of the Amblève, the other to Werbomont and thence to Trois Ponts.

The 119th left General Hobbs and traveled south to Remouchamps. At this point it divided, one detachment made up of the 2d Battalion and the cannon company heading for Werbomont, the second and stronger column winding along the road that descended into the Amblève valley. The 2d Battalion reached Lienne Creek after dark and threw up hasty defenses on the hills about three miles east of Werbomont. The Germans under Peiper had been stopped at the creek earlier, it will be recalled, but the battalion was in time to ambush and destroy the separate scouting force in the late evening. The 3d Battalion, leading the truck column carrying the bulk of the combat team, reached Stoumont after dark and hurried to form a perimeter defense. Patrols pushing out from the village had no difficulty in discovering the enemy, whose pickets were smoking and talking not more than 2,000 yards away. At least forty German tanks were reported in bivouac east of the village. Under cover of darkness the remainder of the American force assembled some three miles northwest of Stoumont, while the 400th Armored Field Artillery Battalion, picked up during the march, moved its batteries forward in the dark. Both

[336]

Americans and Germans, then, were ready with the coming of day to do battle for Stoumont.

The 117th Infantry, first of the 30th Division regiments to be fed into the line, had been deploying on the morning of 18 December around Malmédy. Its 1st Battalion (Lt. Col. Ernest Frankland), under orders to occupy Stavelot, circled through Francorchamps to approach the town from the north. On the road Colonel Frankland met officers of the 526th Armored Infantry Battalion who told him that the enemy was in Stavelot. About this time word of the German success reached the V Corps headquarters, where it was assumed that the 1st Battalion would perforce abandon its mission. Frankland, on the contrary, kept on going. He made contact about 1300 with a rifle company of the 26th Armored Infantry Battalion remaining near Stavelot, then detrucked his battalion north of the still-flaming gasoline roadblock and started south toward the town.

All this while Peiper believed that the 3d Parachute Division was close behind his column. Expecting it to reach Stavelot by the evening of 18 December, he had left only a small holding force in the town. In fact, the 3d Parachute Division had been held up by a combination of jammed roads and unexpectedly tenacious American resistance. The Sixth Panzer Army therefore did not expect the advance guard of the 3d Parachute Division to arrive in Stavelot before 19 December. At this point the failure of communications between Peiper and rearward German headquarters began to influence the course of operations, to the distinct disadvantage of the Sixth Panzer Army. Although without artillery support, Colonel Frankland launched his attack at Stavelot. On the slope north of the town a platoon of 3-inch towed tank destroyers from the 823d Tank Destroyer Battalion made good use of positions above the Germans to knock out a brace of Mark VI tanks and a few half-tracks. The two leading companies of the 1st Battalion had just reached the houses at the northern edge of the town when ten hostile tanks, returning in haste from Trois Ponts, counterattacked.

It might have gone hard with the American infantry but for the fighter-bombers of the IX Tactical Air Command and XXIX Tactical Air Command which opportunely entered the fray. During the afternoon the American planes had worked east from the La Gleize area, where the little liaison planes had first signaled the presence of German columns, and struck where-ever Peiper's tanks and motor vehicles could be found. Perhaps the trail provided by the rearward serials of Kampfgruppe Peiper led the fighter-bombers to Stavelot; perhaps the 106th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron, which broke through the clouds to make one sweep over the town, tipped off the squadrons working farther west. Before the German tanks could make headway, planes from the 365th Fighter Group, reinforced by the 390th Squadron (366th) and the 506th Squadron (404th), plunged in, crippled a few enemy vehicles, and drove the balance to cover, leaving the infantry and tank destroyers to carry out the cleanup inside Stavelot on more equitable terms. By dark the two American companies held half of the town, had tied in with the 2d Battalion between Stavelot and Malmédy, and were

[337]

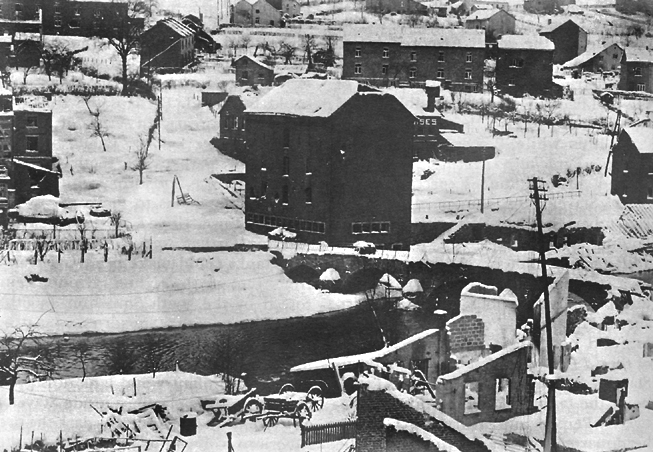

AMBLÈVE RIVER BRIDGE AT STAVELOT

reinforced by a tank platoon from the 743d Tank Battalion. Also the riflemen had the comforting knowledge that they could call for and receive artillery support: the 118th Field Artillery Battalion had moved through bullet fire and set up northeast of the town.

The fight for Stavelot continued all through the night of the 18th with German tanks, now free from the air threat, working through the streets as far as the town square. At daybreak the 1st Battalion and its tanks went to work and by noon had reclaimed all of the town down to the Amblève River. Twice during the afternoon tank-led formations drove toward the town, but both times the American gunners dispersed the field gray infantry and the tanks decided not to chance the assault alone. It is not surprising that the German infantry gave over the field. The 118th cannoneers fired 3,000 shells into the assault waves, working their guns so fast that the tubes had to be cooled with water.

By the night of 19 December the 1st Battalion had a firm grip on Stavelot-but, in the most telling stroke of all, its attached engineers had dynamited the Amblève bridge across which Peiper's force had rolled west on the morning of 18 December. The armored weight of the 1st SS Panzer Division could make itself felt only if it continued punching westward. Without fuel the punch and drive were gone.

[338]

Without the Amblève bridge and a free line of communications through Stavelot there was no fuel for Peiper. Without Peiper the freeway to the Meuse which the 1st SS Panzer Division was to open for the following divisions of the Sixth Panzer Army remained nothing more than a cul-de-sac.

Could the 30th Division surround and destroy Kampfgruppe Peiper before German reinforcements from the east reopened the way to their now isolated comrades? Would the 30th Division, its rear and right flank partially uncovered, be left free to deal with Peiper? The latter question was very real, even with the 82d Airborne moving in, for on the morning of 19 December the V Corps commander had warned the 30th Division chief of staff (Col. Richard W. Stephens) that large German forces had slipped by to the south and were moving on Hotton. An additional question plagued the 30th Division: where was the 7th Armored? Patrols sent out toward Recht on the 19th could find no trace of the tankers.

While the 1st Battalion, 117th Infantry, was busily severing the lifeline to Kampfgruppe Peiper on 19 December, Peiper was engaged with the bulk of his troops in an attempt to blast a path through Stoumont, the barrier to the last possible exit west, that is, the valley of the Amblève. Battle long since had been joined at Stoumont when scouts finally reached Peiper with the story of what had happened to his line of communications.

The kampfgruppe, whose major part was now assembled in the vicinity of La Gleize and Stoumont, consisted of a mixed battalion of Mark IV tanks and Panthers from the 1st SS Panzer Regiment, a battalion of armored infantry from the 2d SS Panzer Grenadier Regiment, a flak battalion, a battalion of Tiger tanks (which had joined Peiper at Stavelot), a battery of 105-mm. self-propelled guns, and a company from the 3d Parachute Division which had ridden on the tanks from Honsfeld. The force had suffered some losses in its breakthrough to the west, but these were not severe. By now the critical consideration was gasoline. A few more miles on the road or a few hours of combat maneuvering and Peiper's fuel tanks would be bone dry.

When the 119th Infantry (minus the 2d Battalion) moved into the Stoumont area on the night of 18 December, the rifle companies of the 3d Battalion (Lt. Col. Roy G. Fitzgerald) deployed in a hastily established line north, south, and east of the town. The 3d was backed up by light 3-inch towed tank destroyers belonging to the 823d Tank Destroyer Battalion, two 90-mm. antiaircraft guns detached from the 143d Antiaircraft Battalion, and three battalion 57-mm. antitank guns. The 1st Battalion, it will be remembered, dismounted in an assembly area about three miles northwest of Stoumont, where Colonel Sutherland located the regimental command post. The moment patrols had established the proximity of the large German force Sutherland was alerted, and he promised a tank company as reinforcement first thing in the morning. For the rest of the night the troops around Stoumont dug foxholes, planted mines, and waited uneasily for day to break.

Stoumont and the American lines lay on a bald hill mass rising on the north bank of the Amblève. La Gleize, the enemy assembly area, shared a similar

[339]

situation on the road east of Stoumont. The road itself, some distance from the river bank, approached Stoumont through patches of trees, which gave way at the eastern edge of the town to a border of level fields. The whole lent itself admirably to the employment of armor.

As the first light came on 19 December Peiper threw his infantry into the attack, supporting this advance from the east with tanks firing as assault guns. The grenadiers and paratroopers were checked by fire from the American lines as they crossed the open fields. But the gunners of the 823d, who could not see fifty yards from the muzzles of their guns and whose frantic calls for flares to be fired over the German tanks went unheeded, could not pick out the enemy armor. The panzers, formed in two columns, moved toward the foxhole line and the American company on the east edge of Stoumont fell back to the houses, uncovering the outnumbered and immobile towed tank destroyers, all eight of which were captured.6 At this moment the ten tank from the 743d Tank Battalion promised by Sutherland arrived and went into action. The enemy thereupon reverted to tactics successfully employed in reducing village resistance on the march west, sending two or three of the heavy-armored Panthers or Tigers in dashes straight along the road and into the town. At least six German tanks were crippled or destroyed in this phase of the action, two of them by antiaircraft crewmen, Private Seamon and Pvt. Albert A. Darago, who were handling bazookas for the first time and who were awarded the DSC for their bravery. (An infantry officer had showed the antiaircraft crew how to load and fire the bazooka just before the battle began.) One of the two 90-mm. antiaircraft guns also did yeoman service in the unfamiliar ground-laying role and destroyed two tanks from Peiper's heavy Mark VI battalion before the German infantry got in close enough to force its abandonment.

The Germans took some two hours to force their way inside Stoumont, but once the panzers ruled the streets the fight was ended. The rifle company on the south was cut off and the company in the town liquidated. The third company withdrew under a smoke screen laid down by white phosphorus grenades, reaching the reserve position manned by the 1st Battalion about noon. The tanks, commanded by 1st. Lt. Walter D. Macht, withdrew without loss, carrying survivors of the center company on their decks. The 3d Battalion had lost most of its equipment, as well as 267 officers and men.

This engagement had seen the Americans fighting without the artillery support so essential in American tactics. The 197th Field Artillery Battalion, assigned the direct support mission, did not reach firing positions in time to help the 3d Battalion. The 400th Armored Field Artillery Battalion was finally able to place one battery where it could give some help, but by this time the battle had been decided and the cannoneers fired only a few missions.

Word that the fight was going against the troops at Stoumont impelled Colonel Sutherland to alert his reserve battalion.

[340]

Company C, dispatched as reinforcement, had reached the village of Targnon when it began to pass men of the 3d Battalion moving to the rear. The company dismounted from its trucks and marched as far as the entrance to Stoumont. Failing to find the 3d Battalion commander the riflemen joined the tanks, which by this time had no infantry cover and were running low on ammunition. The newly wedded tank-infantry team yielded ground only in a slow and orderly withdrawal. The impetus of the German advance was considerably reduced when a 90-mm. antiaircraft gun, sited at a bend in the road west of Stoumont, knocked out a couple of German tanks and momentarily blocked the highway.

The situation was precarious-and not only for the force left to Sutherland. The only armor between the 119th Infantry command post and Liège was a detachment of ten Sherman tanks which had been whipped out of the First Army repair shops, manned with ordnance mechanics, and dispatched through Aywaille to block the Amblève River road. In front of the 119th command post the ten tanks of the 743d had but few rounds left in their ammunition racks.

At 1035 the 30th Division commander, who was in Sutherland's command post, called the First Army headquarters to ask for the 740th Tank Battalion. The S-2 of the 119th Infantry had discovered that this outfit, a new arrival on the Continent, was waiting to draw its tanks and other equipment at an ordnance depot near Sprimont, about ten miles north of the 119th command post. The First Army staff agreed to Hobbs's request, but the unit it handed over was far from being ready for combat. The depot had few fully equipped Shermans on hand and the first tank company drew fourteen Shermans fitted with British radios (unfamiliar to the American crews), five duplex drive tanks, and a 90mm. self-propelled gun. While Hobbs was on the phone trying to convince the army staff that he must have the tanks, his chief of staff, Colonel Stephens, was being bombarded by army demands that some part of the 119th should be pulled out and shifted north to cover the road to Spa and First Army headquarters. This was out of the question for the moment, for Sutherland had only a single battalion at his disposal.

All this while the little tank-infantry team held to its slow-paced withdrawal along the river road, lashing back at the Panthers in pursuit. Retreating through Targnon and Stoumont Station the force reached a very narrow curve where the road passed between a steep hill and the river bank. Here Lt. Col. Robert Herlong, who now had all of his 1st Battalion engaged, ordered the tanks and infantry to make their stand. It was about 1240. Fog was beginning to creep over the valley. A forward observer from the 197th Field Artillery Battalion, whose pieces now were in position, saw three German tanks leave Targnon and head down the road. A call sent a salvo crashing down on the western side of the village just as a large tank column started to follow the German point. Followed by more shells these tanks turned hurriedly back into Targnon. One of the point tanks did reach the American position, poked its nose around the bend in the road, got a round of high explosive uncomfortably close, and took off.

It is true that Herlong's tanks and infantry held a naturally formidable roadblock.

[341]

And the presence of artillery once again showed what it could do to alter the course of battle. But Peiper's object in the advance beyond Stoumont was not to crush his way through the 119th Infantry and move north through the defiles of the Amblève valley. His object, thus far unachieved, was to climb out of the valley confines and resume the westerly advance toward Huy and the Meuse. Peiper had been thwarted at Trois Ponts and at Lienne Creek in turn. The advance through Stoumont offered a last opportunity, for midway between Targnon and Stoumont Station lay an easy approach to the river, a bridge as yet untouched, and a passable road rising from the valley to join the highway leading west through Werbomont, the road from which Peiper's force had been deflected. With this bridge in German hands, Peiper had only to contain the 119th Infantry which had been retiring before his tanks while his main column crossed to the west. But Peiper knew by this time that his supply line had been cut at Stavelot. "We began to realize," he says, "that we had insufficient gasoline to cross the bridge west of Stoumont." 7

Unaware of the enemy predicament, the 119th Infantry took advantage of the lull which had followed the single German pass at the roadblock position to reorganize the remnants of the 3d Battalion. About 1530 the leading platoon of the conglomerate company taken from the 740th Tank Battalion arrived, but the additional infantry for which Colonel Sutherland had pleaded were not forthcoming. Indeed, his weakened 3d Battalion was already earmarked for use in the event the enemy turned north on the secondary road running from Stoumont directly to Spa and the First Army headquarters. However, Sutherland was told that the 2d Battalion, 119th Infantry, was in process of turning its position east of Werbomont over to the 82d Airborne Division and would be available in a few hours.

Anxious to feel out the enemy and establish a good line of departure for an attack on 20 December, Sutherland ordered the 1st Battalion commander to push out from the roadblock, using Capt. James D. Berry's untried and conglomerate tank company. About 1600 Herlong started east, Company C advancing on both sides of the road and tanks moving in the center. Just west of Stoumont Station three Panthers were sighted and destroyed in quick succession, one by a fluke shot which glanced from the pavement up through the tank flooring. The dead tanks blocked the road; so Herlong sent his infantry on alone and organized a line at the western edge of the station. There was no further contact with the Germans. Peiper, whose mechanized force by this time was nearly immobile, had withdrawn his advanced troops back to Stoumont, about two and a half miles east of the station. As for the road leading from Stoumont to Spa, a matter of grave concern to First Army headquarters on 19 December, Peiper, acutely conscious of his lack of mobility, never gave it a serious thought.

In midafternoon the 119th Infantry and the 740th Tank Battalion (Lt. Col. George K. Rubel) had been detached from the 30th Division and assigned to the operational control of the XVIII Airborne Corps, which at the same time took

[342]

back its 82d Airborne Division from the V Corps and in addition received the 3d Armored Division (-). The XVIII Corps commander thus had an entire airborne division, more than half of an armored division, and a reinforced regimental combat team to employ in checking a further westward drive by the Germans assembled in the La Gleize-Werbomont-Stoumont area.

The subsequent operations of the XVIII Airborne Corps would be molded in considerable degree by events prior to its appearance in the battle area. Already set forth have been the engagements in the Stoumont sector with two battalions of the 119th Infantry committed. The 2d Battalion of the 119th Infantry had left the regiment on 18 December with the independent mission of blocking the Germans at Werbomont and Trois Ponts, thus covering the assembly of the 82d Airborne. Late in the afternoon the battalion reached Werbomont, found no sign of the enemy, and detrucked for the march to Trois Ponts. About dusk the column reached the Lienne Creek in the vicinity of Habiemont, a village on a bald summit overlooking the Lienne. Here Maj. Hal D. McCown, the battalion commander, learned that German tanks had been sighted at Chevron, another hamlet a mile or so north on the Lienne. McCown, whose battalion was reinforced by a platoon each of tanks, tank destroyers, and infantry cannon, turned north only to find that the bridge near Chevron had been destroyed by friendly engineers and that no hostile crossing had been made. He moved north again but this time encountered fire from across the creek. Uncertain as to the situation and with darkness upon him, McCown ordered the battalion to deploy on the bare ridge line rising west of the creek.

Some time later the Americans heard tracks clanking along the road between their position and the creek; this was the reconnaissance detachment which Peiper had sent north and which had found a bridge, albeit too weak a structure for the German tanks. A brief fusillade from the ridge and the Germans fled, leaving five battered half-tracks behind. One prisoner from the 2d SS Panzer Grenadier Regiment was taken. His company, he told interrogators, was the advance guard of a four company detachment whose mission was to reconnoiter toward Werbomont and take that town. But no other attempt was made that night to run the 2d Battalion gauntlet. Screened by McCown's force, the 82d Airborne Division was free to detruck and assemble around Werbomont, as the night progressed, according to plan.

Recall that on the morning of 18 December the 82d Airborne Division started for Bastogne but was diverted short of its destination and ordered to Werbomont. General Gavin had gone from the First Army headquarters to Werbomont and made a personal reconnaissance of the ground as far as the Amblève River. This, of course, was on the morning of the 18th so that he saw none of the enemy forces who at that moment were turning in the direction of Werbomont. The advance party of the 82d arrived in the village at dark and opened the division command post. Although there was now serious question whether the convoys of the 82d would reach Werbomont in force before the Germans, the bulk of the division moved without opposition into the area during the night of 18 December. The following

[343]

GENERAL RIGDWAY AND GENERAL GAVIN

morning Maj. Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway, who had resumed command of the airborne corps, opened his corps command post near that of the 82d, once again under Gavin.

Later in the morning at the First Army headquarters (which had moved to Chaudfontaine), General Hodges gave Ridgway the directive which would make the airborne corps operational and flesh it out with troops. The corps' mission was to block further German advance along an irregular line extending from the Amblève through Manhay and Houffalize to La Roche on the Ourthe River, placing the corps' right boundary twenty miles northwest of Bastogne. Three threatened areas were known to be in the newly assigned zone of operations: the Amblève River sector, where the 119th Infantry was deployed; the Salm River sector, especially at Trois Ponts where a lone engineer company still barred the crossings (although this information was unknown to the 82d); and the general area north of the Ourthe

[344]

River where a vague and ill-defined German movement had been reported. But beyond checking these specific enemy advances the XVIII Airborne Corps had the more difficult task of sealing the gap of nearly twenty miles which had opened between the V and VIII Corps.

During the morning of 19 December the 504th and 505th Parachute Infantry Regiments marched out of the Werbomont assembly area under orders to push to the fore as far as possible, relieve the 2d Battalion, 119th Infantry, and improve the American defense line by adding a bridgehead across the Lienne Creek. There were no Germans here and by noon the initial deployment was close to completion. Meanwhile rumors had reached the First Army command post that the enemy had cut the main north-south highway running between Bastogne and Liège in the neighborhood of Houffalize. More rumors, mostly from truck drivers whose missions on the rear area roads usually gave them first sight of the westernmost German spearheads, put the enemy somewhere near Hotton, ten miles northwest of the XVIII Airborne Corps boundary marker at La Roche. Hastily complying with First Army orders, the 3d Battalion of the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment and a tank destroyer platoon set off southwestward to block the approaches to Hotton. By nightfall the battalion was in place, stuck out alone on the corps' right wing and waiting for troops of the 3d Armored to appear. A couple of hours before midnight a patrol did meet the armored "point"-Maj. Gen. Maurice Rose, the 3d Armored commander, riding in a jeep far in front of his tank columns.

The main body of the 82d Airborne Division began to push toward the east and south in midafternoon. With the 508th Parachute Infantry in support, the 504th and 505th moved along the roads toward La Gleize and Trois Ponts respectively. This proved to be only a route march, for the Germans were nowhere about.8 By midnight the 505th had a battalion each in the villages of Haute-Bodeux and Basse-Bodeux, effectively backstopping the small American force which still held Trois Ponts. The 504th, which had marched northeast, occupied the village of Rahier with two battalions. The 325th Glider Infantry, minus the battalion sent to Hotton, remained in and around Werbomont as corps and division reserve. One of its companies moved during the evening to the crossroads at Manhay, due south of Werbomont, a crossroads which General Ridgway styled "of vital significance." And a company of the 508th meanwhile established an outpost position on the Manhay-Trois Ponts road at Bras.

By the morning of 20 December, therefore, the 82d Airborne Division had pushed a defensive screen north, east, south, and west of Werbomont. It is true that to the south and west the screen consisted only of motorized patrols and widely separated pickets in small villages, but now there was a good chance that any major enemy thrust could be detected and channelized or retarded. Thus far, however, the XVIII Airborne Corps was making its deployment against an unseen enemy. Indeed, so confused was the situation into which Ridgway

[345]

TROOPS OF 325TH GLIDER INFANTRY MOVING THROUGH FOG TO A NEW POSITION

had been thrust that at midnight on 19 December he was forced to send an urgent message to Hodges asking for information on any V or VIII Corps units in his zone. But his corps was substantially strengthened by the next morning. CCB of the 3d Armored Division had reached Theux, about ten miles north of Stoumont, and was ready for immediate use. The 3d Armored Division (minus CCA and CCB) had reached the road between Hotton and Manhay on the corps' right wing.9

Ridgway had detailed plans for continuing the pressure along the corps front from northeast to southwest. CCB,

[346]

MAP 2

3d Armored, was to clear the east and north banks of the Amblève and establish contact with the 117th Infantry, which had its hands full in Stavelot. The reinforced 119th Infantry was to secure the Amblève River line from Stoumont to La Gleize. The 82d Airborne Division was to take over the Salm River bridges at Trois Ponts, drive the enemy from the area between the Amblève and the Werbomont-Trois Ponts road, and make contact with CCB when the latter reached Stavelot, thus completing the encirclement of such enemy forces as might be left to the north. The 3d Armored Division was to fan out and push reconnaissance as far as the road between Manhay and Houffalize, locating and developing the shadowy German force believed to be bearing down on the sketchy corps right wing somewhere north of Houffalize.

The immediate and proximate threat, on the morning of 20 December, was Peiper's force of the 1st SS Panzer Division, now concentrated with its bulk in

[347]

the Stoumont-La Gleize area, but with an outpost holding the light bridge over the Amblève at Cheneux and its tail involved in a fight to reopen the rearward line of communications through Stavelot. Kampfgruppe Peiper, it should be noticed, was considerably weakened by this piecemeal deployment; furthermore, it lacked the gasoline to undertake much maneuver even in this constricted area. (Map 2)

CCB (Brig. Gen. Truman E. Boudinot) moved south past Spa on the morning of the 20th in three task forces, using three roads leading to the Stoumont-La Gleize-Trois Ponts triangle. The largest of these detachments, Task Force Lovelady (Lt. Col. William B. Lovelady), had been given a complete tank battalion, reinforced by a company of armored infantry, and the important job of cutting the Stavelot-Stoumont road. Colonel Lovelady, then, led the force which formed the left jaw of the vise forming to clamp down on Kampfgruppe Peiper. His task force, proceeding on the easternmost of the three routes, reached the junction of the Trois Ponts-Stoumont roads without sign of the enemy. Just as the column was making the turn south toward Trois Ponts, a small enemy column of artillery, infantry, and supply trucks appeared, apparently on its way to reinforce Peiper's main body.

Since Trois Ponts and Stavelot were both in American hands, the appearance of this train was surprising. What had happened was this: German engineers had reinforced a small footbridge east of Trois Ponts, at least to the point that it would sustain a self-propelled gun carriage, and since the night of 18 December supply trucks and reinforcements had used the bridge to slip between the two American-held towns. German records indicate that some much-needed gasoline reached Peiper through this hole in the American net, but the amount was insufficient to set the kampfgruppe rolling again even if the road west had been free. As to this particular German column, the Americans disposed of it in short order. Task Force Lovelady continued on its mission and established three roadblocks along the main road between Trois Ponts and La Gleize. The Germans in the Stoumont sector were definitely sealed in, albeit still active, for four Shermans were destroyed by hidden antitank guns.

The two remaining task forces of CCB and companion units from the 30th Division were less successful. Task Force McGeorge (Maj. K. T. McGeorge), the center column, made its advance along a road built on the side of a ridge which ran obliquely from the northeast toward La Gleize. Most of the ridge road was traversed with no sight of the Germans. At Cour, about two miles from La Gleize, Task Force McGeorge picked up Company K of the 117th Infantry and moved on to assault the latter town. Midway the Americans encountered a roadblock held by a tank and a couple of assault guns. Because the pitch of the ridge slope precluded any tank maneuver, the rifle company circled the German outpost and advanced as far as the outskirts of La Gleize. A sharp counterattack drove the infantry back into the tanks, still road-bound, and when the tanks themselves were threatened by close-in work McGeorge withdrew the task force for the night to the hamlet of Borgoumont perched above La Gleize. It was apparent that the Germans intended

[348]

to hold on to La Gleize, although in fact E the greater part of Peiper's command by this time was congregated to the west on the higher ground around Stoumont.

The attack on Stoumont on the 20th was a continuation of that begun late on the previous afternoon by the 1st Battalion of the 119th Infantry. The maneuver now, however, was concentric. The 1st Battalion and its accompanying tank company from the 740th Tank Battalion pushed along the road from the west while Task Force Jordan (Capt. John W. Jordan), the last and smallest of the three CCB detachments, attempted a thrust from the north via the Spa road, which had given the First Army headquarters so much concern. Task Force Jordan was within sight of Stoumont when the tanks forming the point were suddenly brought under flanking fire by German tanks that had been dug in to give hull defilade. The two American lead tanks were knocked out immediately. The rest of the column, fixed to the roadway by the forest and abrupt ground, could not deploy. Search for some other means of approach was futile, and the task force halted for the night on the road.

The 1st Battalion, 119th Infantry, and the company of medium tanks from the 740th Tank Battalion found slow but steady going in the first hours of the attack along the western road. With Company B and the tanks leading and with artillery and mortars firing rapidly in support, the battalion moved through Targnon. The Germans had constructed a series of mine fields to bar the winding road which climbed up the Stoumont hill and had left rear guard infantry on the slopes north of the road to cover these barriers by fire. At the close of day the attacking column had traversed some 3,000 yards and passed five mine fields (with only two tanks lost), the infantry advance guard climbing the wooded hillside to flank and denude each barrier.

Now within 800 yards of the western edge of Stoumont and with darkness and a heavy fog settling over the town, Colonel Herlong gave orders for the column to close up for the night. One of the disabled tanks was turned sidewise to block the narrow road, while Companies B and C moved up the hill north of this improvised barrier to seize a sanatorium which overlooked the road and the town. The main sanatorium building stood on an earthen platform filled in as a projection from the hillside rising north of the road. Its inmates, some two hundred sick children and old people, had taken to the basement. After a brief shelling the American infantry climbed over the fill and, shrouded in the fog, assaulted the building. The German infantry were driven out and four 20-mm. guns taken. Companies B and C dug in to form a line on the hillside in and around the sanatorium, and Company A disposed itself to cover the valley road. Four tanks were brought up the slope just below the fill and in this forward position were refueled by armored utility cars. The enemy foxhole line lay only some three hundred yards east of the companies on the hill.

An hour before midnight the Germans suddenly descended on the sanatorium, shouting "Heil Hitler" and firing wildly. On the slope above the building German tanks had inched forward to positions from which they could fire directly into the sanatorium. American tanks were brought up but could not negotiate the

[349]

STOUMONT, SHOWING THE SANATORIUM

steep banks at the fill. One was set afire by a bazooka; two more were knocked out by German tanks which had crept down the main road. The flaming tanks and some outbuildings which had been set afire near the sanatorium so lighted the approach to the building that further American tank maneuver on the slope was impossible. By this time German tanks had run in close enough to fire through the windows of the sanatorium. The frenzied fight inside and around the building went on for a half hour or so, a duel with grenades and bullet fire at close quarters. About thirty men from Company B were captured as the battle eddied through rooms and hallways, and the attackers finally gained possession of the main building. However, Sgt. William J. Widener with a group of eleven men held on in a small annex, the sergeant shouting out sensings-while American shells fell-to an artillery observer in a foxhole some fifty yards away. (Widener and Pfc. John Leinen, who braved enemy fire to keep the defenders of the annex supplied with ammunition, later received the DSC.)

Although the German assault had won possession of the sanatorium and had pushed back the American line on the slope to the north, accurate and incessant shellfire checked the attackers short of a breakthrough. About 0530 the enemy tried it again in a sortie from the town headed for the main road. But tank reinforcements had arrived for the 1st Battalion and their fire, thickening that of

[350]

the artillery, broke the attack before it could make appreciable headway. When day broke, the Americans still held the roadblock position but the enemy had the sanatorium. In the night of wild fighting half the complement of Companies B and C had been lost, including five platoon leaders.

Despite the setbacks suffered during the American advance of 20 December on the Stoumont-La Gleize area, the net had been drawn appreciably tighter around Peiper. The German line of supply-or retreat-was cut by Task Force Lovelady and the Americans in Stavelot. The roads from Stoumont and La Gleize north to Spa were blocked by tank-infantry teams which had pushed very close to the former two towns. The 1st Battalion of the 119th Infantry had been checked at the sanatorium but nonetheless was at the very entrance to Stoumont and had the 2d Battalion behind it in regimental reserve.

Also, during the 20th, the 82d Airborne Division moved to close the circle around Peiper by operations aimed at erasing the small German bridgehead at Cheneux on the Amblève southeast of Stoumont. The 82d had planned an advance that morning to drive the enemy from the area bounded on the north by the Amblève River and by the Trois Ponts-Werbomont road on the south. The two regiments involved (the 504th Parachute Infantry on the left and the 505th on the right) marched to their attack positions east of Werbomont with virtually no information except that they were to block the enemy, wherever he might be found, in conjunction with friendly forces operating somewhere off to the north and south. The first task, obviously, was to reconnoiter for either enemy or friendly forces in the area.

Patrols sent out at daybreak were gone for hours, but about noon, as bits of information began to arrive at General Gavin's headquarters, the picture took some shape. Patrols working due north reached the 119th Infantry on the road west of Stoumont and reported that the countryside was free of the enemy. Civilians questioned by patrols on the Werbomont-Stoumont road told the Americans that there was a concentration of tanks and other vehicles around Cheneux. Working eastward, other patrols found that Trois Ponts was occupied by Company C, 51st Engineers, and that the important bridges there had all been damaged or destroyed. This word from Trois Ponts came as a surprise back at General Gavin's headquarters where the presence of this single engineer company at the critical Trois Ponts crossing site was quite unknown.10

The most important discovery made by the airborne infantry patrols was the location of the 7th Armored Division troops in the gap between the XVIII Airborne Corps and Bastogne. The whereabouts of the westernmost 7th Armored Division positions had been a question of grave import in the higher American headquarters for the past two days. Now a patrol from the 505th Parachute Infantry came in with information that they had reached a reconnaissance party of the 7th Armored in the village of Fosse, a little over two miles southwest of Trois Ponts, and that troops of that division were forming an outpost line just to the south of the 505th positions.

[351]

Once General Gavin had a moderately clear picture of the situation confronting his division he ordered the two leading regiments forward: the 504th to Cheneux, where the enemy had been reported, and the 505th to Trois Ponts. The 505th commander, Col. William E. Ekman, already had dispatched bazooka teams to reinforce the engineer company at the latter point and by late afternoon had his 2d Battalion in Trois Ponts, with one company holding a bridgehead across the Salm.

Acting under orders to reach Cheneux as quickly as possible and seize the Amblève bridge, the 504th commander, Col. Reuben H. Tucker, 3d, sent Companies B and C of his 1st Battalion hurrying toward the village. The leading company was nearing the outskirts of Cheneux in midafternoon when it came into a hail of machine gun and flak fire. Both companies deployed and took up the fire fight but quickly found that the village was strongly defended. Ground haze was heavy and friendly artillery could not be adjusted to give a helping hand. Dark was coming on and the companies withdrew to a wood west of Cheneux to await further orders.

The 1st Battalion had not long to wait. New plans which would greatly extend the 82d Airborne Division front were already in execution and it was imperative that the German bridgehead on the north flank of the division be erased promptly. Colonel Tucker ordered the 1st Battalion commander (Lt. Col. Willard E. Harrison) to take the two companies and try a night attack. At 1930 they moved out astride the road west of Cheneux, two tank destroyers their only heavy support. The approach to the village brought the paratroopers across a knob completely barren of cover, sloping gradually up to the German positions and crisscrossed with barbed wire. The hostile garrison, from the 2d SS Panzer Grenadier Regiment, was heavily reinforced by mobile flak pieces, mortars, machine guns, and assault artillery.

To breast this heavy fire and rush the four hundred yards of open terrain, the two companies attacked in four waves at intervals of about fifty yards. The moment the leading American assault waves could be discerned through the darkness the enemy opened an intense, accurate fire. Twice the attackers were driven back, both times with gaping ranks. The first two waves were almost completely shot down. Company C ran into the wire and, having no wire cutters available, was stalled momentarily. Finally the two tank destroyers worked their way to the front and began to shell the German guns. With their support a third assault was thrown at the village. This time a few men lived to reach the outlying houses. In a brief engagement at close quarters the Americans silenced some of the flak and machine guns, then set up a defense to guard this slight toehold until reinforcements could arrive.

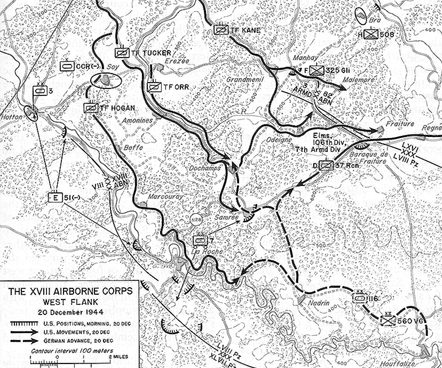

The West Flank of the XVIII Airborne Corps

20 December

The general advance of the XVIII Airborne Corps on 20 December included the mission assigned to the 3d Armored Division of securing the Bastogne-Liège highway between Manhay and Houffalize, thus screening the right or western flank of the corps. The bulk of the 3d Armored was engaged elsewhere: CCA deployed as a defense for the Eupen area, CCB driving with troops of the

[352]

30th Infantry Division against Kampfgruppe Peiper. When General Rose moved his forward command post to Hotton on 20 December, the residue of the 3d Armored was assembling between Hotton and Soy, a force numbering only the small reserve combat command and the 83d Reconnaissance Battalion. Nothing was known of any friendly troops to the front, nor did information on the location and strength of the enemy have more than the validity of rumor. Since it was necessary to reconnoiter and clear the area west of the important section of the north-south highway, now his objective, General Rose decided to divide his limited strength into three columns, two attacking via generally north-south routes and then swinging eastward; the third, on the extreme left, driving east to the Manhay crossroads and then turning south on the main highway.

This was a risky decision, as the 3d Armored commander well knew, for the zone of attack was very broad and if one of the small columns ran into a superior enemy force the best it could do would be to fight a delaying action on its own. Terrain and weather, however, would aid the reconnaissance somewhat, for although the area was laced by back roads and trails German maneuver would be drastically curtailed and a German advance limited to the few open and passable roads. General Rose tried to retain as much flexibility as he could, in view of the vague status of the enemy and the width of the front to be covered. The three task forces, or more properly reconnaissance teams, assigned to Lt. Col. Prentice E. Yeomans each had a reconnaissance troop, a medium tank company, a battery of armored field artillery, and a platoon of light tanks. The reserve, commanded by Col. Robert L. Howze, Jr., was made up of an armored infantry battalion, two companies of light tanks and one of mediums, plus a company of engineers. This reserve would follow the middle task force.

The attack or reconnaissance, time would tell which, began in early afternoon. On the right Task Force Hogan (Lt. Col. Samuel M. Hogan) set out along a secondary road surmounting the ridge which rose on the east bank of the Ourthe River and extended south to La Roche, the boundary for the XVIII Airborne Corps right wing. The Ourthe River, then, would form a natural screen on this flank. Hogan's column met no opposition en route to La Roche and upon arrival there found that the town was defended by roadblocks that had been thrown up by the 7th Armored Division trains. At this point the route dropped into the river valley, following the twists and turns of the Ourthe toward the southeast. Hogan sent on a small scouting force which covered some three miles before it was confronted by a German roadblock. There was no way around, daylight was running out, and the force halted.

The road assigned Task Force Tucker (Maj. John Tucker), the center column, followed the Aisne River valley southward. At the village of Dochamps this route began an ascent from the valley onto the ridge or tableland where lay the town of Samrée. At Samrée Task Force Tucker was to make a left wheel onto the La Roche-Salmchâteau road (N28), which followed a high, narrow ridge line to the east, there crossing the main Liège-Bastogne highway. This intersection, the Baraque de Fraiture,

[353]

would have a special importance in later fighting.

Tucker's column moved unopposed through the Aisne valley but at Dochamps, where began the ascent to the Samrée highland, it was engaged by a German force of unknown strength. In an attempt to continue the reconnaissance Major Tucker split his command in three. One force circled west and south to Samrée where, it had only now been learned, a part of the 7th Armored Division trains was fighting to hold the town. The second group turned east and finally made contact with Task Force Kane. Tucker's third group moved back north to Amonines.

Late in the afternoon General Rose learned that the 3d Armored tanks sent to Samrée had been knocked out and the town itself lost to the enemy. The elevation on which Samrée stood and its importance as a barrier on the highway from La Roche to the division objective made recapture of the town almost mandatory. Rose ordered Colonel Yeomans to regain Samrée and hold it; for this mission two companies of armored infantry from the reserve combat command were detailed to Lt. Col. William R. Orr. Colonel Orr picked up the remaining elements of Task Force Tucker and arrived outside of Dochamps a little before midnight, setting up a roadblock for the remainder of the night.

Task Force Kane (Lt. Col. Matthew W. Kane), on the left in the three column advance, found easy going on 20 December. Acting as the pivot for the swing south and east, Kane's column was charged with the occupation of Malempré, about 3,000 yards southeast of the vital Manhay crossroads. This latter junction on the Liège-Bastogne highway represented a position tactically untenable. Hills away to the east and west dominated the village, and to the southeast an extensive woods promised cover from which the enemy could bring fire on the crossroads. By reason of the ground, therefore, Malempré, on a hill beyond the woods, was the chosen objective. Kane's task force reached Manhay and pushed advance elements as far as Malempré without meeting the enemy.

The three reconnaissance forces of the 3d Armored Division by the close of 20 December had accomplished a part of their mission by discovering the general direction of the German advance northwest of Houffalize and, on two of the three roads, had made contact with the enemy. It remained to establish the enemy's strength and his immediate intentions. As yet no prisoners had been taken nor precise identifications secured, but the G-2 of the 3d Armored Division (Lt. Col. Andrew Barr) made a guess, based on earlier reports, that the three task forces had met the 116th Panzer Division and that the 560th Volks Grenadier Division was following the former as support.

Action in Front of the XVIII Airborne Corps Right Wing on 20 December

As the 3d Armored Division assembled for advance on the morning of 20 December, and indeed for most of the day, it was unaware that little groups of Americans continued to hold roadblocks and delay the enemy in the area lying to the front of the XVIII Airborne Corps right wing. These miniature delaying positions had been formed on 18 and 19 December by men belonging to the 7th

[354]

MAP 3

Armored Division trains, commanded by Colonel Adams, and by two combat engineer battalions, the 51st and 158th. As the 7th Armored advanced into combat around St. Vith on 18 December and it became apparent that German thrusts were piercing deep on both flanks of this position, Adams received orders to move the division trains into the area around La Roche and prepare a defense for that town and the Ourthe bridges. Most of the vehicles under Adams' command were concentrated west of La Roche by 20 December, but large stores of ammunition, rations, and gasoline had just been moved to dumps at Samrée. (Map 3)

The 51st Engineer Combat Battalion (Lt. Col. Harvey R. Fraser) had arrived at Hotton on 19 December with orders to construct a barrier line farther south which would utilize the Ourthe River as a natural obstacle. The battalion was minus Company C, which, at Trois Ponts, did much to slow the pace of Kampfgruppe Peiper's westward march. It did

[355]

have the services of the 9th Canadian Forestry Company, which took on the task of preparing the Ourthe crossings south of La Roche for demolition. From La Roche north to Hotton and for several kilometers beyond, the remaining two companies worked at mining passable fording sites, fixing explosives on bridges, and erecting roadblocks; but the extensive project was far from complete on 20 December. The sketchy barrier line on the Ourthe was extended toward Bastogne by the 158th Engineer Combat Battalion.11 To the 7th Armored trains and the engineers were added little groups of heterogeneous composition and improvised armament, picked up by the nearest headquarters and hurried to the Ourthe River line in answer to rumors of the German advance over Houffalize. It is hardly surprising, then, that the 3d Armored Division began its advance unaware of efforts already afoot to delay the enemy.

While little American detachments worked feverishly to prepare some kind of barrier line on the Ourthe River and around La Roche and Samrée, the north wing of the Fifth Panzer Army was coming closer and closer. Krueger's LVIII Panzer Corps pushed its advance guard through the Houffalize area on 19 December, while the rear guard mopped up American stragglers and isolated detachments on the west bank of the Our River. Krueger's orders were to push as far west as possible on the axis Houffalize-La Roche while his neighbor on the left, the XXXVII Panzer Corps, cut its way through Bastogne or circled past the road complex centered there.

The Reconnaissance Battalion of the 116th Panzer Division, several hours ahead of the main body of Krueger's corps, had reached Houffalize on the morning of 19 December, but because Krueger expected the town to be strongly defended and had ordered his reconnaissance to avoid a fight there the battalion veered to the south, then west toward La Roche. This brief enemy apparition and sudden disappearance near Houffalize probably account for the conflicting and confusing rumors as to the location of the Germans in this sector which were current in American headquarters on 19 December. Between Bertogne and La Roche the Reconnaissance Battalion discovered that the bridge over the west branch of the Ourthe had been destroyed. At this point the Germans had a brush with one of the roadblocks put out by the 7th Armored troops in La Roche and thus alerted Colonel Adams.12 Adams had no other information of the enemy.

It seemed to Adams, as a result of the skirmish, that the German advance toward La Roche was being made on the northwest bank of the main branch of the Ourthe River and that the final attack would come from the west rather than the east. He therefore moved the 7th Armored dumps from locations west of La Roche to Samrée, from which point he hoped to maintain contact with and continue supplies to the main body of the division at St. Vith. By early morning of 20 December the transfer had

[356]

been completed. Adams now was confronted with the necessity of pushing his defenses farther east to protect the new supply point. He dispatched part of a battery of the 203d Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion to the Baraque de Fraiture crossroads formed by the intersection of the Samrée-Salmchâteau road and the main Liège-Bastogne highway, the same junction which had seemed so important to the XVIII Airborne Corps commander in his map reconnaissance of this area. Upon arrival there the newcomers found that some gunners from the 106th Infantry Division, commanded by Maj. Arthur C. Parker, already had dug in to defend the vital crossroads.

The German appearance at the broken bridge which altered Colonel Adams' plans had even greater effect in General Krueger's headquarters. Krueger had no bridging available in the corps trains when the word reached him on the night of the 19th. The fact that he had to rely on the limited capacity of the 116th Panzer Division engineers meant that the western branch of the Ourthe could not be spanned before the evening of 20 December. Such a delay was out of the question. To sidestep to the south would bang the corps against very strong resistance forming around Bastogne and would scramble the vehicular columns of Krueger's armor with the 2d Panzer Division. By this time the 116th Panzer Division rear guard had occupied Houffalize without a fight. The main body of the division, having marched unopposed nearly to the road which runs from Bastogne northwest to Marche, was preparing to seize a second bridge over the west branch of the Ourthe at Ortheuville. Krueger had no faith that any stroke of fortune would deliver the Ourtheuville bridge untouched. This was the end of the fourth day of the German advance and the Americans, he reasoned, were long since on guard against a coup de main there.

Weighing the apparent American strength in the Bastogne sector against the total absence of resistance at Houffalize the LVIII Panzer Corps commander decided, late in the evening of the 19th, to shift his advance to the north bank of the Ourthe River and reroute the 116th Panzer Division toward Samrée by way of Houffalize. The order to halt his division and countermarch to Houffalize was a distinctly unpleasant experience for General von Waldenburg. (He would later say that his decision was "fatal to the division.") The business of reversing a mechanized division in full swing under conditions of total darkness is ticklish at best; when it is conducted by tired officers and men unfamiliar with the road net and is hampered by supply and artillery trains backing up behind the turning columns it is a serious test for any unit. Nevertheless the 116th sorted itself out, issued supplies, refueled its vehicles, and by early morning was en route to Houffalize. Meanwhile the 1128th Regiment, leading the 560th Volks Grenadier Division, had been closing up fast on the 116th Panzer Division in a series of forced marches (that later won for the 560th a commendation for its "excellent march performance"). By noon of 20 December the bulk of the 116th Panzer Division followed by a large portion of the 560th Volks Grenadier Division had defiled through Houffalize and was on the north bank of the Ourthe River.13

[357]

The maneuver now to be executed was a left wheel into attack against Samrée and La Roche, with the main effort, carried by the tank regiment of the 116th Panzer Division, made at Samrée. The right flank of the attack would be covered by the 560th Volks Grenadier Division As the morning drew along the Americans had made their presence felt by increasingly effective artillery fire from the north. German scouts reported that there were tanks to be seen near Samrée (actually the American garrison there had only one) but that the ground would sustain a German tank attack The 60th Panzer Grenadier Regiment assembled under cover of the woods south of the town, and the tanks (from the 16th Panzer Regiment) moved out onto the Samrée road. Advance patrols, which had started a fire fight in the late morning, were able to occupy a few houses when a fog settled in shortly after noon.

All this time the 7th Armored Division quartermaster, Lt. Col. A. A. Miller, had been issuing rations, ammunition, and gasoline as fast as trucks could load. The force he had inside Samrée was small: half of the 3967th Quartermaster Truck Company, the quartermaster section of the division headquarters, part of the 440th Armored Field Artillery Battalion's Service Battery, two sections of D Battery, 203d Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion, armed with quadruple-mount machine guns, plus a light tank and a half-track from the 87th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron. About noon word reached Samrée that the 3d Armored Division was sending a task force to the town. The German patrols had not yet entered the town; so, heartened by the approach of the friendly armor, Miller gave orders that no supplies were to be destroyed. About 1430 the fire fight quickened. Hearing that the 3d Armored tanks had reached Dochamps, Miller drove to find the task force and insure that he would get immediate aid. Not more than a half hour later the Germans swarmed in under a sharp barrage of rocket fire. By this time the one tank was out of ammunition, the machine gunners manning the .50-caliber weapons on the quartermaster trucks were also running low, the antiaircraft outfit had lost three of its weapons and fired its last round, and the division Class III officer had ordered the units to evacuate. A majority of the troops got out with most of their trucks and the remaining artillery ammunition, but 15,000 rations and 25,000 gallons of gasoline were left behind.

Shortly after, the detachment sent from Task Force Tucker appeared. Two armored cars, at the point, entered the north edge of the town, but the six medium tanks following were quickly destroyed by German armor coming in from the east. During the shooting the armored cars were able to pick up the surviving tankers and escape to La Roche. The 7th Armored Division headquarters received word of the fight, and from La Roche the commander of the Trains Headquarters Company, 1st. Lt. Denniston Averill, hurried to Samrée with two medium tanks and a self-propelled tank destroyer. Averill's little party attempted to enter Samrée, but was not heard from again.

[358]