CHAPTER IV

The Base In Australia

The Japanese, having occupied Rabaul in January, on 8 March moved into Lae and Salamaua on the upper coast of eastern New Guinea, which put them in easy bombing distance of Port Moresby, the chief Australian outpost in New Guinea, about 700 miles across the Coral Sea from Townsville. This was the situation when General MacArthur arrived in Australia from the Philippines on 17 March. That same day he was named by the Australian Government as its choice for Supreme Commander of the Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA) and on 18 April officially assumed command of the new theater. MacArthur filled the top positions on his staff with the men who had come with him from Corregidor and who had served with him in USAFFE. In addition to the existing American commands, consisting of USAFFE (now a shadow command), United States Forces in the Philippines (USFIP), and USAFIA, MacArthur established three tactical commands within SWPA. These were Allied Land Forces under an Australian, General Sir Thomas Blarney; Allied Air Forces under General Brett; and Allied Naval Forces, also under an American, Vice Adm. Herbert F. Leary. American ground forces were assigned to USAFIA but came under General Blarney for operational employment.2

[44]

With the limited forces at his command, there was little General MacArthur could do for some time to come beyond checking the enemy's advances toward Australia, protecting land, sea, and air communications in the theater, and preparing for later offensives. For the time being, air operations against the Japanese on New Guinea and Rabaul and protection of Australian airfields, coastal cities, and shipping were the main effort. Support of air as well as port operations was the first major task of the USAFIA Ordnance office.3

Rounding Up Weapons and Ammunition

Weapons and ammunition were urgently needed to arm aircraft and defend airfields, coastal cities, and ships, but little help could be expected immediately from the United States. The automatic system of Class II and IV supply set up by the first War Department plan for Australia, dated 20 December 1941, was aimed at building up a 60-day level by 1 March 1942 and was raised in early February to a 90-day level, but it soon broke down for lack of shipping and supplies. In any case it would take time for the system to be effective and there was an inescapable time lag involved in the long voyage from San Francisco. From the first, War Department policy called for American commanders in Australia to obtain locally as many items as possible, and for this purpose Holman had brought with him credits for $300,000 in Ordnance funds. Only partially used, and later reimbursed by SWPA, these funds were of major importance in the early days in Australia. Part went into services and materials for storing the ammunition that came in the Coolidge and the Mariposa. Ammunition, which was supplied automatically for the first six months of 1942, did not present as serious a problem as weapons, though requests were made for more bombs and ammunition for aircraft and ground machine guns, antiaircraft guns, and small arms.4

After 21 February 1942 all local procurement was done by the American Purchasing Commission, established by General Barnes to coordinate and control all USAFIA purchasing, prevent competition, fix priorities, and work with U.S. naval authorities. The commission was composed of a representative from each technical service and had a Quartermaster chairman. The Ordnance member was Maj. Bertram H. Hirsch. Unfortunately, Australia's resources after three years of war were meager. According to General Brett, "There was plenty of money available to purchase what we wanted, but heartbreakingly little of what we wanted and needed."5

[45]

The men on Holman's staff had to round up weapons wherever they could. In response to a request by General Brett in March to arm Air Forces ground personnel with rifles and machine guns, Holman got about 10,000 Enfields from distress cargoes and salvaged machine guns from wrecked aircraft, improvising mounts for them. To bolster seacoast defenses, the Australians had some lend-lease 155-mm. guns of World War I vintage. Captain Kirsten, who was an expert on antiaircraft weapons, and M. Sgt. Delmar E. Tucker of Holman's office helped convert these guns into coast artillery by supervising their installation on Panama mounts and instructing Australian personnel in their operation. This was an effort that continued throughout most of 1942. Tucker, a specialist on artillery, was so good in his field that he was offered a commission in Artillery, and so loyal to Ordnance that he turned down the offer. He also made a fine contribution, along with Captain Kirsten, to the early and very important ship arming project.6

Australia had always depended heavily on coastal shipping because its railways and highways were inadequate even in peacetime. Railroads ran along the coast, with feeder lines branching into the vast and mostly uninhabited interior, but there were no through trains in the American sense, for lines linking the populous states of Queensland, New South Wales, and Victoria had different gauges, so that every time a state line was crossed, men and freight had to change trains. Australia had no major highways suitable for long-distance haulage; such roads as existed were fit only for light traffic. Once the Americans began building the logistical bases, coastal shipping between Australian ports became even more important, and after the Japanese threat to Port Moresby in March 1942, ship traffic northward increased immeasurably.7

The theater's early need for ships and still more ships was partially met by the temporary retention of transpacific merchantmen arriving from San Francisco, but it very soon became plain that USAFIA would have to acquire a local fleet to move troops, equipment, and supplies within the theater. A beginning was made when twenty-one small Dutch freighters, which had formerly operated in the Netherlands Indies and had taken refuge in Australian ports after the fall of Java, were chartered from their owners, the Koninklijke Paket-vaart Maatschappij (KPM). The KPM vessels formed the backbone of the "X" fleet of small freighters on which men and cargoes were carried between Australian ports, north to Port Moresby, New Guinea, and eventually around the southern coast of New Guinea north as far as Cape Nelson. USAFIA also discovered the need for a fleet of shallow-draft vessels that could navigate among coral reefs and use primitive landing places far up the coast of New Guinea and in the outlying islands. For this purpose it obtained from the Australians a miscellaneous collection of luggers.

[46]

rusty trawlers, old schooners, launches, ketches, yawls, and yachts, which became known as the "S" fleet, sometimes called the "catboat flotilla." Both of these makeshift fleets were under Army control and remained so because the U.S. Navy, which theoretically operated all seagoing vessels in theaters of operations, maintained that it did not have the resources to do so in SWPA.8

The "X" and "S" fleets sailing out of Australian ports were heading into dangerous waters and had to be armed against enemy action. A large share of this responsibility, as well as the main responsibility for inspecting and servicing ships' guns at the ports, fell on USAFIA Ordnance. The U.S. Navy was unable to help in the early days, and the efforts of the Royal Australian Navy were restricted to vessels assigned to the theater by the British Ministry of Transport, including most of the KPM ships and several others of the "X" fleet, but excluding ships of American registry.9

Providentially there arrived in Australia in the spring of 1942 a shipment of weapons that could be used on the USAFIA fleets, particularly on the large and growing "S" fleet. The shipment had been dispatched from the United States in mid-February under the UGR Project initiated shortly after Pearl Harbor by Col. Charles H. Unger for the purpose of arming small vessels to be used in running the Japanese blockade of the Philippines. By the time the shipment arrived the Philippines had fallen. USAFIA's Small Ships Supply-Section fell heir to the weapons—fifty 105-mm. howitzers, fifty 37-mm. antitank guns on M4 carriages, five hundred .30-caliber machine guns on Cygnet mounts, and a quantity of miscellaneous equipment.10

The 105-mm. howitzers of the UGR Project were intended to be exchanged for 75-mm. guns in the hands of troops already in Australia; the 75's would then be employed in ship armament. Forty-nine 75-mm. guns were rounded up from theater resources. Of these, eight had been on board a ship beached during the Japanese raid on Darwin on 19 February. After being under water for thirty-nine days, the guns were salvaged, completely overhauled under the supervision of Sergeant Tucker, and sent to Melbourne for ship armament. Only sample ship mounts for the 37's and 75's had come from the United States. Holman's staff took the samples to Australian firms, supervised the manufacture of mounts and adapters, and then used Ordnance troops to remove the guns from their carriages and place them on the mounts. Because they considered the Cygnet mount for the .30-caliber machine gun unsuitable, the USAFIA Ordnance men designed a pedestal type of mount that would take either the .30-caliber machine gun or its preferred replacement, the .50-caliber machine gun, and had about 200 manufactured in Melbourne. On the small ship project, Ordnance worked closely with the

[47]

group headed by Colonel Unger, who had over-all responsibility for small ship procurement and operation.11

The overworked USAFIA Ordnance troops continued to service British, Dutch, and Australian weapons as well as American. Some help came from Australian maintenance experts and from Australian Navy facilities, but this aid was not entirely satisfactory, and an acute shortage of American maintenance units complicated the task.12

The main problem of the USAFIA Ordnance officer was manpower—"first, last, and always."13 To supply Ordnance service at far-flung installations on the rim of the island continent stretched his resources to the utmost. By 3 March 1942 the USAFIA commander had established six base sections: Base Section 1 at Darwin, Base Section 2 at Townsville, Base Section 3 at Brisbane, Base Section 4 at Melbourne, Base Section 5 at Adelaide on the southern coast, and Base Section 6 at Perth on the west coast; and soon afterward, Base Section 7 at Sydney. Acting as service commands and communications zones, the base sections received, assembled, and forwarded all U.S. troops and supplies, and operated ports and military installations. Until early April, when 17 technicians and clerks from the United States reported to Holman's office and ground Ordnance units began to arrive, the technical personnel that could be spared from aviation Ordnance units were placed on special duty to work at the ports.

The nine Ordnance aviation companies that began arriving in mid-March were immediately dispersed to support their combat or air base groups. By the end of April there were air base groups in the Townsville, Brisbane, Melbourne, Sydney, and Darwin areas, and small servicing details at Adelaide and Perth. Combat operations were centered in the north. Moving to the Darwin and Townsville areas, where Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) airfields were being supplemented by fields constructed by U.S. Engineers, bombardment and pursuit groups took their own Ordnance companies with them. As the groups sent out squadrons to cover the danger areas on the northern coast, Ordnance aviation companies were divided into platoons to accompany them.14

The story of the 445th Ordnance (Aviation) Bombardment Company exemplifies the strain placed on aviation companies. Two platoons accompanying the 49th Pursuit Group (the first group to get into operation in Australia) when it moved from Sydney into the Darwin area in mid-March were split up in order to serve squadrons of the 49th at different landing strips. This duty consisted of unbelting, oiling, polishing, and rebelting all ammunition each

[48]

night, and stripping, oiling, and polishing all guns every third night. At the beginning of May, one of the platoons was attached to the 71st Bombardment Squadron and sent to operate the ammunition dump at Batchelor Field. This air terminal was forty miles south of Darwin, so far from any port or railhead that Quartermaster supplies could not get through and the men had to obtain much of their meat by hunting. In mid-May a fourth platoon of the 445th was sent to New Caledonia.15

Dispersion of Ground Reinforcements

When the first Large increment of ground Ordnance troops arrived the second week in April, it also was widely dispersed. The troops had been sent from the United States to support the first ground reinforcements sent to Australia. The reinforcements, dispatched as a result of a mid-February warning message from General Wavell, commander of ABDA, that the loss of Java might have to be conceded, consisted of about 25,000 troops, including the 41st Infantry Division and 8,000 service troops of which 700 were Ordnance—one medium maintenance company, one depot, and two ammunition companies. Early in March, after the collapse of ABDA, a second infantry division, the 32d, was sent to Australia at the request of Prime Minister Churchill, who wanted to avoid bringing an Australian division home from the then critical Middle East battle zone. The 32d Infantry Division brought with it another medium maintenance company. These were the last reinforcements of any size to arrive in Australia for some time to come, despite urgent requests by General Brett for many more ground units, including Ordnance units up to three ammunition battalions, three maintenance and supply battalions, and three depot companies. There were not enough men available in the United States or ships to carry them.16

The Ordnance companies that arrived with the main body of the 41st Division at Melbourne the second week in April were the 37th Ordnance Medium Maintenance Company, the 84th Ordnance Depot Company, and the 55th and 50th Ordnance Ammunition Companies. The 84th Depot Company established at Seymour (north of Melbourne) the first Ordnance general supply depot in Australia. Soon the new arrivals were scattered all over Australia. The 37th Ordnance Medium Maintenance and the 55th Ordnance Ammunition Companies were sent to Brisbane to provide service to air and antiaircraft units there and at Base Section 2 at Townsville. The 84th, for many months the only depot company in Australia, furnished an officer and

[49]

five enlisted men to form the Ordnance Section of Base Section 7 at Sydney, where distress cargoes, chiefly Dutch, were piling up. The 84th also supplied a detachment to operate a general supply depot at Adelaide on the south coast, the headquarters of the 32d Division.17

The 118th Ordnance Medium Maintenance Company, commanded by 1st Lt. Frederick G. Waite, arrived with the 32d Division. The company landed without its tools, equipment, repair trucks, or parts, but the young commander managed to acquire some distress cargo tools at the Adelaide port. In the circumstances, Waite remembered later, the job of supporting the division "was not done as well and as thoroughly as we desired, or as the combat troops had a right to expect" but "did get done after a fashion." In addition, he had to send detachments to aid port operations at Sydney, an antiaircraft regiment at Perth, and the task force at Darwin.18

It took the most careful planning by Colonel Holman's office to make the best use of the very scarce Ordnance troops. The depot and ammunition sections that had arrived in March were organized into the 36oth Ordnance Composite Company, activated on 1 May, and sent about 100 miles north of Adelaide to operate at one of the transshipment points on the overland route to Darwin. Between Darwin and the cities of the eastern and southern coasts there was a gap in the railroad line of as much as 600 miles. This had to be bridged by truck or air transport. The 25th Ordnance Medium Maintenance (AA) Company was given the job of supporting the 41st Infantry Division, but because this company was especially experienced in antiaircraft artillery, it had small detachments at Brisbane, Townsville, and Perth working on fire control instruments and instructing other Ordnance companies in that kind of maintenance. Out of the effort at Townsville grew the very important Townsville Antiaircraft Ordnance Training Center directed by the commander of the 25th, Capt. William A. McCree.19

The necessity of splitting Ordnance companies into detachments placed a severe drain on organic unit equipment. A single machine shop truck might be adequate for the work of a medium maintenance company, but when the company was split into detachments operating in four separate areas the men would need four trucks instead of one; an aviation bombardment company would need additional truck cranes; an ammunition company, a larger supply of tarpaulins. All required more messing equipment, and also water trailers for operations in a country where water was scarce. Mobile equipment operating

[50]

over poor roads, or none at all, required an ample supply of spare parts.20

A Huge Continent With Poor Transportation

For the first five months of 1942, the one factor primarily affecting supply in Australia was transportation. This is amply illustrated by the story of the early effort to transport ammunition from southern and eastern ports to Darwin. It had to be sent overland because the sea lanes to Darwin were insecure, and the hardships reminded one observer of the attempt to forward supplies over the Burma Road.21

From Adelaide the rail line north stopped at Alice Springs, which seemed to one Ordnance officer a comparatively large community for the outback—"actually several houses and even curbs along the street." From there, supplies were carried forward in trucks operated by the Australians. About six hundred miles north, at Birdum—one small building and three tin shacks—there was a railroad to Darwin, but it had small capacity, was antiquated and in poor repair, and was chiefly useful in the rainy season when the dirt road, in some places only bush trail, was washed out.

From Brisbane to Darwin, a distance of 2,500 miles, the railroads ran only as far as Mount Isa, a small settlement that reminded some Ordnance officers of a mining town in Arizona or Nevada. There, supplies were transshipped to Birdum by Australian truck companies. Assuming cargo space was available—not always a safe assumption—a shipment normally took about ten days. In early February one load of 18,000 75-mm. shells was delayed for ten days and finally arrived without fuzes. It took another eight days to find the fuzes and deliver them by air.22

Beginning in March regulating stations were established along the routes to Darwin, but the length of time supplies were in transit and the probability of losses en route made necessary extra supplies to fill gaps in the supply line. General Barnes warned Washington that particular attention would have to be given to ammunition shipments from the United States because of the large distribution factor involved in long hauls and poor transportation.23

Looking for "lost" Ordnance supplies and troops, reconnoitering for depot and shop sites, the RPH officers who had arrived with Colonel Holman spent weeks at a time in the field, furnishing aid and comfort to harassed officers at remote sta-

[51]

CONVOY OF TRUCKS NEAR MOUNT ISA, QUEENSLAND

tions. "Believe me," Major Hirsch reported to Colonel Holman, "there's nothing these chaps like better than to have a staff officer out in the bush, making passes at the flies on their faces and eating dust with their food." These officers often traversed country so treeless and desolate that by comparison the American desert seemed "a garden of Eden." But sometimes there were diverting adventures. Reconnoitering for an ammunition depot near Rockhampton, Major Hirsch received unexpected help from a bushman who "divined" for water with a forked stick; and on a survey trip from Rockhampton to Coomooboolaroo, Hirsch flushed two kangaroos at which he took a few shots with his .45.24

Geelong and the Ordnance Service Centers

Availability of transportation played an important part in the selection of the first important Ordnance installation in Australia. The ammunition that began piling up on the docks at Melbourne in February

[52]

and was dispersed around the city soon presented such a hazard that a safer place had to be found for it. With the help of the Australian Army's Land Office, Hirsch was able to acquire a site across the bay from Melbourne at Geelong. The location was excellent because ammunition, which was loaded first in ships for better ballast and therefore unloaded last, could simply be retained after the other supplies were unloaded at Melbourne and sent around to Geelong in the same ship. When the 25th Ordnance Medium Maintenance Company (AA) landed in Brisbane in mid-March, the main body of the company (less detachments dispatched to the four corners of Australia in support of antiaircraft units) was sent to Geelong to establish Kane Ammunition Depot.25

Out of the Geelong installation grew Holman's concept of the Ordnance service center, which included not only storage (wholesale and retail) but maintenance shops where a great deal of reclamation and salvage work was done: everything possible was saved from wrecked equipment, put into serviceable condition, and reissued. Moreover the center was to become a staging area for Ordnance troops and supplies that came there direct from the ports instead of moving through a general staging area. When Ordnance troops came off the ships they were sent immediately to a service center, where they got a hot meal and a bed. And they could be put to work at the center if their equipment had not come with them, as was often the case. Early in January General Brett had urged that basic essential equipment be sent on the same ship with the units, or at least in the same convoy, but the War Department then, and for six months to come, considered it wasteful of shipping space. The 25th Ordnance Medium Maintenance Company, for example, had arrived without its shop trucks containing its tools and machinery and for that reason had been given the job of starting the ammunition depot.26

At an Ordnance service center Holman could organize, train, control, and use Ordnance troops as he thought best. The opportunity for direct control and flexibility was to prove of great value, not only in the early days when Ordnance units arrived slowly and infrequently from the United States but later when small teams such as those for bomb disposal and technical intelligence came in. Instead of being lost in a large general base, they were under Ordnance control from the start and were kept on Ordnance jobs. Geelong became the model for the Coopers Plains Ordnance Service Center at Brisbane, the first well-developed first-class activity of this kind, which set the standard for future operations. The concept was so successful that it remained in effect in the Southwest Pacific throughout the war. After Holman became Chief of Staff, Headquarters U.S. Army Services of Supply (USASOS), in October 1943, he was instrumental in having the service center concept applied to other technical services as well as Ordnance.27

[53]

Fine co-operation by the Australian Army's Land Office, plus the benefits of reverse lend-lease, made possible the establishment of a number of Ordnance installations by summer 1942. The Australians helped in the location of ammunition depots, which according to the Ordnance supply plan were to be established in the western districts of each base section; after Kane, the most important was the depot at Darra, near Brisbane. In the populous areas around Melbourne, Adelaide, and Sydney, the Australians provided industrial buildings for depots and shops, mostly wool warehouses, some of them with good concrete floors and traveling cranes, and in less industrialized areas, wool sheds, school-houses, small automobile shops and warehouses, a rambling frame orphanage, and an old dance hall. Some of these buildings had their disadvantages. In transforming one wool shed into an Ordnance maintenance shop, the Engineers had to shovel their way through a "mixture of dirt, old wool, hides and manure and the place stunk to high Heaven."28

Ordnance officers found their opposite numbers in the Australian Army eager to co-operate. They provided not only depot sites but trucking and other services and facilities for training and maintenance. In Schools conducted by the Australian Army, men of the three Ordnance medium maintenance companies, for example, received early training in British 40-mm. Bofors antiaircraft guns and fire control equipment, and aviation Ordnance men learned about bomb disposal. In the Brisbane and Townsville areas, where facilities were expanding late in the spring, Australian maintenance shop officers had instructions to do work for Americans under the same system and priority as for Australians. Late in May Colonel Holman was planning to help make up for the lack of a heavy maintenance company, which had been requested from the United States but not received, by using a large fourth echelon repair shop then being built by the Australians at Charters Towers, eighty-three miles inland from Townsville.29

When lend-lease Ordnance supplies and equipment began to arrive in quantities in June, Holman's men helped unload and distribute them, instructed Australian troops in maintenance, and provided the technical data requested by Australian Army authorities, who were keenly interested in all U.S. weapons, ammunition, and equipment brought into the theater. By the end of May the USAFIA Ordnance office was planning a definite project for servicing American lend-lease tanks; and experimental work was already under way at Australia's Armored Fighting Vehicles School at Puckapunyal near Seymour.30

Throughout the spring, Australian factories, shops, and other possible sources of

[54]

supply were thoroughly explored by the USAFIA Ordnance men. They found a plentiful supply of cleaning and preserving materials, lumber, paints and oils, gas for welding, and fire-fighting equipment; some standard motor parts; and a limited supply of abrasives, cloth and waste, tool steel, and maintenance equipment and tools. Moreover, the Australians were able to manufacture some standard items of Ordnance equipment such as link-loading machines for .30-caliber and .50-caliber ammunition, arming wires and bomb fin retaining rings, leather pistol holsters and rifle slings, machine gun water chests, and cleaning rods and brushes for machine guns and ramrods for larger weapons.

The USAFIA Ordnance Section designed many items and adapted others, such as the gun mounts devised for ship arming and airfield defense, to fit U.S. Army requirements. Jib cranes were developed to facilitate the handling of bombs from railway cars to trucks and at the depots; a scout car for line of communications units was made by fitting a light armored body on the chassis of small Canadian trucks evacuated from the Netherlands Indies. A rapid automatic link loader for machine guns was copied from a U.S. Navy model, and because reports from air units showed that regular ammunition delinking, inspecting, cleaning, and relinking had to be done to insure proper functioning of machine gun feeding, a delinker similar to one designed by a U.S. Air Forces Ordnance officer was manufactured in Australia.

Many of the Ordnance items that the Americans improvised or adapted in the theater were accepted for their own use by the Australians, who seemed to Holman's staff to have great respect for American equipment. Suggestions for inventions poured into the USAFIA Ordnance office from Australian soldiers and civilians; one invention that amused Kirsten was a "disappearing bayonet," which was not visible to the unsuspecting Japanese soldier until it was suddenly sprung on him. With very few exceptions, the inventors' ideas were forwarded to Australian military authorities in accordance with an agreement worked out for the handling of such suggestions.31

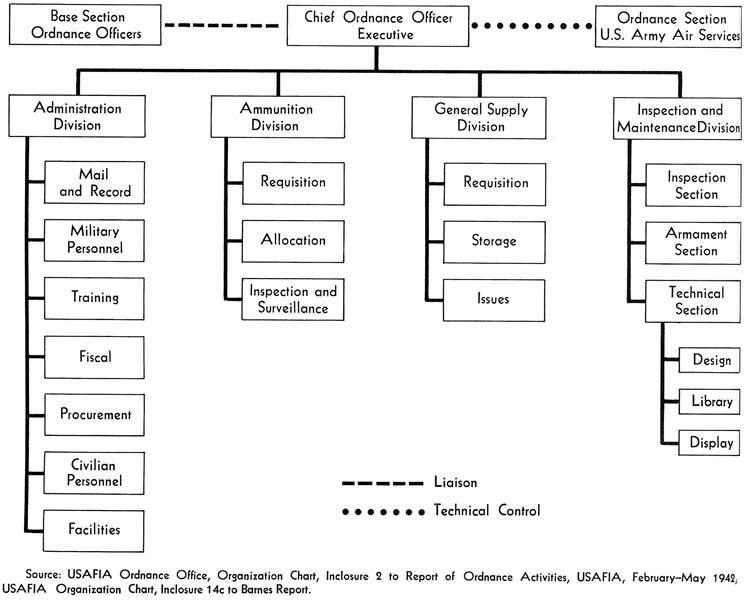

The directive establishing the Southwest Pacific Area under the command of General MacArthur on 18 April 1942 set up separate organizations for Allied Land Forces and Allied Air Forces, the former commanded by Australia's General Blarney, the latter by General Brett. On 27 April the United States Army Air Services (USAAS) was created and placed under the command of Maj. Gen. Rush B. Lincoln. For some time, there was confusion as to its exact responsibility; it was the end of May before USAAS was officially defined as an administrative, supply, maintenance, and engineering command operating under the commander of the Allied Air Forces.32 (Chart 1)

The Ordnance Section of USAAS was staffed with four officers and seven enlisted men from the USAFIA Ordnance office and was headed by Maj. Robert S. Blodgett, chosen for the job by Colonel

[55]

CHART 1-THE U.S. ARMY FORCES IN AUSTRALIA ORDNANCE OFFICE, MAY 1942

Holman, who had served with Blodgett in the United States and had a high opinion of his ability. Two of the officers had come south from the Philippines: Maj. Harry C. Porter had flown from Corregidor and Maj. Victor C. Huffsmith had had a perilous sea voyage from Manila to Mindanao, sailing immediately after Pearl Harbor in a small ship with detachments of two Ordnance aviation companies, the 701st and 440th. Ordered to Australia on 29 April, he was on the last flight out of Mindanao before the Japanese took over.33

Though the USAAS Ordnance Section was divorced from the USAFIA Ordnance Section, the two offices necessarily worked

[56]

closely together, since in the early days of SWPA air operations were the primary effort. USAAS obtained its ammunition and Ordnance major items from USAFIA. Later, as the air operations grew and spread over very large areas, the official connection weakened. After Maj. Gen. George C. Kenney on 4 August 1942 took over from General Brett the command of the Allied Air Forces, and the Fifth Air Force was established, USAAS became a part of the Fifth Air Force (in October redesignated Air Service Command, Fifth Air Force). The March 1942 organization by which three major commands were established under the War Department-ground, air, and service-had its effect; and there were presages of the reorganization that was soon to shift control of Ordnance aviation troops to Air Forces commanders. But between Blodgett's and Holman's offices a good deal of informal and very effective liaison continued, a circumstance that Holman attributed to Blodgett's excellent relationship with Kenney and his loyalty to Ordnance.34

Midsummer 1942: New Responsibilities

Six months after the Pensacola convoy landed with one Ordnance company, Ordnance strength in Australia stood at 145 officers and 3,500 enlisted men. There were four ammunition companies (out of twelve requested); three medium maintenance (out of five requested); one depot (out of five requested); one composite; and fifteen aviation companies-six air base, six bombardment, and three pursuit. With these men, most of whom had been in Australia less than three months, Colonel Holman had staffed five ammunition depots and five maintenance and supply depots, was providing Ordnance service to two divisions and fifteen air groups, and was handling incoming supplies and transshipments at seven ports.35

There were still grave shortages in supplies, notably in spare parts, tools, bomb-handling equipment, and technical manuals. Much still remained to be done in segregating stores and training troops; for example, one young ammunition officer complained that all his time was spent in finding out where bombs, fuzes, and arming wires were stored, and teaching his men "what to do, how to fuze and put arming wires on, how to put bombs into bomb bays . . . ." But depots and shops were beginning to operate with some degree of efficiency, especially in the Melbourne, Adelaide, and Sydney areas. At the depot in Adelaide, for example, items were correctly stored in bins and Standard Nomenclature List groups were segregated. Kane Ammunition Depot near Melbourne was becoming "an Ordnance show place."36

Transportation and communications between the southern cities and the northern

[57]

outposts were slowly improving. Bottlenecks were being eliminated from the road north to Darwin and the use of Australian teletype instead of straight mail from Melbourne to Darwin and Townsville shortened communications time considerably. The Ordnance office at Townsville, which according to Major Hirsch had been leading a "hand to mouth existence.. . mainly because actual information of coming events is either lacking entirely or delayed beyond comprehension," was now "in the throes of growing up."37

For the very real accomplishments that spring and summer of 1942 in Australia in the face of meager resources, Colonel Holman was given a large share of the credit by the young officers of his USAFIA Ordnance staff. They admired not only his brains and imagination but his enthusiasm and his positive approach to problems. At USAFIA staff meetings, Kirsten remembered later, "the Quartermaster would be gloomy—couldn't cook with Australian chocolate, etc.; the Engineer officer would be gloomy—couldn't drive nails in Australian hardwood, etc.; but Holman (though Ordnance was as bad off as any) would say we can get this done in such and such a time. Naturally this made such a good impression he could get almost anything he wanted." Also, Holman had the quality of arousing loyalty. He selected capable young officers and then backed them up.38

During the first half year in Australia, the efforts of the USAFIA Ordnance office had been devoted mainly to support of air and antiaircraft operations, supplying armament and ammunition to the fighter and bomber groups operating from Australian bases in defense of northern Australia and New Guinea and to the antiaircraft units at the ports and airfields and aboard ships. In July, as the chill damp of an Australian winter settled in Melbourne, the USAFIA Ordnance office began preparations to support the New Guinea prong of the first U.S. offensive in the Pacific, as directed by the Joint Chiefs of Staff on 2 July.

The offensive, an "island-hopping" operation of the kind soon to become familiar, would be in three phases. The first, assigned to Vice Adm. Robert L. Ghormley's South Pacific Area, was the capture of Guadalcanal and other islands in the Solomons; the second, assigned to General MacArthur, was the capture of the remainder of the Solomons and the northeastern coast of the narrow Papuan peninsula in New Guinea, where the Japanese held Lae and Salamaua; and the third, also assigned to MacArthur, was the capture of the Japanese stronghold of Rabaul and adjacent areas in the Bismarck Archipelago. The object was to halt the Japanese advance toward the tenuous line of communications between the United States and Australia and New Zealand. The offensive was restricted to the few ships, troops, weapons, and supplies that could be spared from the preparations for an invasion of Europe.39

In Australia, the U.S. armed forces began preparing at once to capture the north-

[58]

ORDNANCE WAREHOUSE, TOWNSVILLE

eastern coast of Papua. The 32d and 41st Infantry Divisions, which along with the 7th Australian Infantry Division were to furnish the ground combat troops, were moved to eastern Australia and started to train for jungle warfare. Until the men were ready, the Army Air Forces was to step up its bombing operations. Engineer troops had been sent to develop new airfields at Port Moresby and at the small but important RAAF base at Milne Bay on the southeastern coast of Papua. These fields would not be enough. For the recapture of Lae and Salamaua, a major airfield on the northeastern coast was necessary. A reconnaissance revealed a good site at Dobodura, about fifteen miles south of Buna, a native village and government station on the northeastern coast of Papua almost opposite Port Moresby, and on 15 July GHQ SWPA directed the launching of operations to occupy the Buna area between 10 and 12 August. (See Map 2)

Within a week of this order, a Japanese convoy was discovered moving on Buna. Aided by bad weather that shielded it from Allied air attacks, the enemy force reached the area on the night of 21 July and began landing. Allied bombing and strafing the next morning had little effect; the Japanese were soon securely established at Buna. General MacArthur's G—2, Brig. Gen. Charles A. Willoughby, believed that they merely wanted the same favorable airfield sites that had attracted the Allies. A Japanese advance overland on Port Moresby,

[59]

only 150 miles to the southwest, was not ruled out, but it seemed highly improbable, because between the northern and southern coasts of Papua rose the 13,000-foot Owen Stanley Range. Over these mountains there were no roads, only narrow, primitive footpaths that became precarious tracks as they wandered up rock faces and bare ridges, then down rivers of mud as they descended into the heavy jungle below. Whatever the intentions of the Japanese, the obvious course for General MacArthur was to reinforce Port Moresby and Milne Bay. He did so by ordering the 7th Australian Infantry Division to move to these areas immediately. He also sent forward engineers and antiaircraft units.40

Preparations To Support the Move Northward

In early July when the New Guinea offensive was directed, Ordnance installations were meager in northeastern Australia, the logical support area for the coming campaign. At Brisbane, designated on 7 August the main base of supply, the 37th Ordnance Medium Maintenance Company was operating in the open air from shop trucks at the edge of Doomben Race Track, and a detachment of the 84th Ordnance Depot Company was setting up a small general supply depot in a converted orphanage building in Clayfield. Until then, general supplies had been stored at Darra, an ammunition dump operated by the 55th Ordnance Ammunition Company with the assistance of about 50 civilian mounted guards and 50 civilian laborers.41

By the end of July, when the 32d Division had moved to Camp Cable, 30 miles south of Brisbane, and the 4ist had arrived at Rockhampton, 400 miles to the north, the USAFIA Ordnance office had secured a tract at Coopers Plains south of Brisbane. Here it began to build a large Ordnance service center to house a maintenance shop of 10,000 square feet, to be operated by the 37th Ordnance Medium Maintenance Company, and a general supply depot of 20,000 square feet, to be operated by the 84th Ordnance Depot Company. The base commander, Col. William H. Donaldson, and his Ordnance officer, Lt. Col. William C. Cauthen, managed to get both shop and depot completed in September, and during the fall the space was more than tripled. At Rockhampton a maintenance shop and a small general supply depot were being established to service the 4ist Division. New ammunition depots were established at Wallaroo, west of Rockhampton, and Columboola, west of Brisbane; Darra was enlarged. A transshipping warehouse was built at Pinkenba from which weapons and ammunition could be forwarded to Townsville and points north.42

At Townsville the Ordnance job became heavier because of the transshipping operation, the concentration of antiaircraft units in northern Australia and New Guinea, and the need to support stepped-up bombing operations. The 25th Ordnance Medium Maintenance Company arrived there on 12 July to distribute and maintain sixty new

[60]

40-mm. Bofors antiaircraft guns. The men found that many of the guns, either defective to begin with or damaged in shipping, had to be rebuilt. In addition to this task the company operated an Ordnance shop and depot—in a building formerly used to manufacture windmills—serviced ships' guns at the port, and sent detachments to isolated units of Coast Artillery. Reinforced by a small detachment of the 5gth Ordnance Ammunition Company, the 55th Ordnance Ammunition Company, which had already furnished a detachment of thirty men for Port Moresby, handled ammunition at the wharf and operated the Kangaroo Transshipment Depot, on the north coast road to Cairns. Transshipment by rail or boat to Cairns, a small port north of Townsville, became important as the supply system to the combat zone evolved. Cairns became a center for small ships into which ammunition was reloaded for the run to New Guinea and points on the Cape York Peninsula. This system was developed to relieve the congestion at Townsville; also smaller and more frequent shipments of ammunition were thought to provide better service with fewer losses. An ammunition storage area was developed at Torrens Creek (180 miles west of Townsville) to support both New Guinea and Darwin should the Townsville-Cairns area be cut off, but it served for only a few air missions and shipments and never became fully operational.43

In the general preparations for the Papua Campaign, General MacArthur's headquarters moved from Melbourne to Brisbane. On 20 July USAFIA was discontinued and United States Army Services of Supply, Southwest Pacific Area (USASOS SWPA), was created and placed under the command of Brig. Gen. Richard J. Marshall, to whom were transferred all USAFIA personnel and organizations.44 Maj. Gen. Robert L. Eichelberger arrived in August with Headquarters, I Corps, to which were assigned the 32d and 41st Divisions.

These changes affected Ordnance service to some extent, but no theater reorganization could compare in effect on Ordnance with a War Department reorganization that took place that summer. Early in August 1942 a cable from Washington to the Commander in Chief, SWPA, announced that responsibility for the supply and maintenance of all motor vehicles was to be transferred from the Quartermaster Corps to the Ordnance Department. USASOS received the news on 15 August, only two weeks before the changeover was to become effective, 1 September 1942.45

Responsibility for Motor Vehicles

The USASOS Ordnance office inherited from Quartermaster about 22,000 vehicles, of which some 15,000 were trucks, ranging in size from the 1/4-ton jeep to the 4-ton 6x6; 3,000 were trailers; and 2,500 were sedans. The rest were ambulances,

[61]

motorcycles, and miscellaneous types. More than 6,000 of the total, including most of the sedans, had been purchased in Australia or obtained from Dutch distress cargoes. Along with the vehicles, Ordnance inherited problems.46

First was the familiar problem of personnel. By agreement between Colonel Holman and Col. Douglas C. Cordiner, the USASOS chief quartermaster, the Quartermaster motor transport officers were told that they must remain with Ordnance for a period of six months or a year (to be released to Quartermaster at the end of the period if they wished). But there were only ten of them at Headquarters, USASOS, two of whom were in ill health, and only seven at the various base section headquarters. The Quartermaster units concerned with motor transport were assigned to Ordnance as of 1 August, but they were few. Only four were in Australia: Company A, 86th Quartermaster Battalion (Light Maintenance), and the 179th Quartermaster Company (Heavy Maintenance), stationed at Mount Isa; Company C, 86th Quartermaster Battalion (Light Maintenance), stationed at Townsville; and Company A, 72d Quartermaster Battalion (Light Maintenance), at Brisbane. In the cities a large proportion of the repair work was being done under contract by commercial automobile companies, which also stored and distributed spare parts.47

The greatest need for repairs was often far from cities and could only be met by maintenance troops. Additional companies had been requested by the USASOS quartermaster, but he had been told that they would not be available before 1943; they were not forthcoming even after Colonel Holman on 10 September urged USASOS to inform Washington that the vehicle maintenance situation was fast approaching the critical stage. Throughout the fall the heavy trucking operation in the Mount Isa-Darwin area, carried on over rough roads in clouds of dust, continued to tie up a large portion of Holman's motor maintenance men. The arrival in Townsville of shiploads of unassembled vehicles made necessary the assignment of mechanics to an assembly plant there, since no commercial assembly plants existed north of Brisbane.48

When Ordnance took over motor vehicles, shortages existed in certain types of trucks, especially the versatile jeeps, which could go anywhere and were particularly valuable as staff cars. There were only about 2,000 in the theater, and they were beginning to be considered by everyone "an absolute necessity"—so much so that

[62]

they were freely stolen by one organization from another. One day a jeep assigned to Capt. John F. McCarthy, Ordnance officer of Base Section 2, disappeared from the street in Townsville where he had parked it and was next seen tied down on an Australian flatcar scheduled to head west with an Australian unit. Colonel Holman commented, "This is the payoff." During the buildup at Port Moresby it was not safe to leave a jeep parked with the keys in it. The shortage was so acute that officers often had to thumb rides or walk for miles.49

For most of the vehicles, particularly jeeps, there were not enough spare parts. The shipping shortage had made it impossible to build up a reserve stock (the ideal was a 90-day reserve supply) and some items were entirely lacking. When Maj. Gen. LeRoy Lutes, deputy commander of Services of Supply, visited Australia in October he noted that the spare parts situation was critical. Since San Francisco records showed that shipments had been made, and since he believed "no doubt many were bogged down on unloaded ships," the fault lay in maldistribution. Because of the poor railroad facilities it had been hard to distribute parts to outlying units from the large bulk storage U.S. Army General Motors Warehouse on Sturt Street, Melbourne. The answer was to carry a complete stock at the base section depots, but this would not be possible until large stocks arrived from the United States, a most unpredictable event because the motor vehicle changeover had caused an upheaval in the Ordnance distribution system.50

In assuming his new responsibilities, Holman saw to it that the Quartermaster officers and units that came over were instructed in Ordnance procedures and that his own Ordnance men learned motor transport maintenance. A significant change in the Ordnance system of maintenance came about that fall on instructions from Washington. Since the 1930's, Ordnance had employed three levels of maintenance: first echelon, performed by the line organization; second echelon, performed by Ordnance maintenance companies in the field; and third echelon, performed in the rear. Influenced by the Quartermaster system, which used four echelons, Ordnance planners instituted a five echelon system. First and second echelon work, now lumped together and called organization maintenance, was done by the using organization. Third echelon, sometimes called medium maintenance, was now done in the field in mobile shops. It involved replacement of assemblies, such as engines and transmissions, as well as general assistance and supply of parts to the using troops. Fourth echelon, commonly referred to as heavy maintenance, was done in the field in fixed or semifixed shops. Fifth echelon, the complete reconditioning or rebuilding of matériel and sometimes the manufacturing of parts and assemblies, was done in base shops.51

[63]

By October 1942 the four Quartermaster motor maintenance companies had been redesignated, three of them becoming Ordnance medium maintenance (Q) and the fourth, heavy maintenance (Q). The Quartermaster bulk parts storage depot in Melbourne became Sturt Ordnance Depot, and to it were transferred Ordnance parts for scout cars, half-tracks, and other Ordnance vehicles, in order that all vehicle requisitions could be filled in one place. In the Brisbane and Sydney areas, where parts had been stored and maintenance mainly done in commercial shops, Colonel Holman was planning to mesh motor transport installations with Ordnance supply and maintenance activities when facilities and personnel permitted. At Brisbane, Colonel Cauthen worked out better methods for assembling crated vehicles, using an outdoor assembly line supervised by Ordnance but operated by combat troop labor provided by the receiving organization. At Townsville motor maintenance, weapons maintenance and depot units, civilian-operated motor parts depots, and tire retreading plants were rapidly consolidated into an Ordnance service center, its most important mission the supply and maintenance of troops en route to New Guinea.52

[64]

Return to the Table of Contents

Last updated 11 January 2007 |