CHAPTER VI

The Base in the British Isles

The new headquarters was not sufficiently informed by the War Department either of the details of the immediate plans made in Washington at the ARCADIA Conference late in December 1941, or, as time went on, of the War Department's long-range plan for making the British Isles a great operating military base. When General Eisenhower went to London in mid-May 1942, he reported to Washington that the USAFBI staff members were "completely at a loss in their earnest attempt to further the war effort."2

In the summer and fall of 1941 the planning of Colonel Coffey and other members of SPOBS had been founded on the ABC reports, which contemplated the bombing of Germany as the first U.S. combat effort from a United Kingdom base. The War Department's RAINBOW 5 plan of April 1941, founded on the ABC-1 Report, provided that the only ground forces to be sent to the United Kingdom immediately after a declaration of war would be 44,364 troops to defend naval and air bases in Scotland and Northern Ireland, and a "token force" of 7,567 men for the defense of the United Kingdom, based in England.3

The ARCADIA Conference, the first wartime meeting of Prime Minister Churchill and President Roosevelt, gave the ground forces a new mission. President Roosevelt agreed to assume at once the responsibility for garrisoning Northern Ireland. The

[88]

first consideration was to release British troops for service in the Middle and Far East, the second was to encourage the British people and to improve relations with Ireland, an obvious danger spot should the Germans invade England. The U.S. force would have to be large. The original plan for the Northern Ireland Sub-Theater provided for three infantry divisions and one armored division, with supporting and service troops and air forces, in all about 158,700 men. The troop movement was code-named MAGNET. The figures for ammunition supply, expressed in units of fire (the specified number of rounds to be expended per weapon per day in the initial stages of an operation), were high: 30 units of fire for antiaircraft weapons, armored units, and antitank units, and 20 units of fire for all other ground weapons. They reflected the anxieties of the time.4

The first information the USAFBI officers had on MAGNET came in a War Department cable of 2 January. They later learned from MAGNET officers that the War Department had been working on the plans before 20 December 1941 and at least one SPOBS officer considered the failure to give General Chaney earlier warning "hard to explain." None of them saw the MAGNET plan until 20 February, when Brig. Gen. Ira C. Eaker brought a copy to London.5

The 2 January cable provided a certain amount of data for the Ordnance officer of USAFBI. The British would furnish antiaircraft protection for the time being, and some armament. To save shipping space and ease the drain on short supply, the MAGNET light artillery units would not bring their 105-mm. howitzers, but would be furnished by the British with comparable 25-pounders. For help in determining the necessary adjustments and instructions on the British gun sight, with which American troops were unfamiliar, General Chaney borrowed from the U.S. military attaché in London two artillery experts, who wrote a field manual and maintenance handbook to be studied by U.S. artillerymen on the voyage.6 In Washington the Ordnance Department was called upon to furnish standard U.S. panoramic telescopes, graduated in millimeters, together with newly designed adapters that were necessary to place the telescopes on the 25-pounder sight mounts. The British would provide ammunition, 1,500 rounds per gun, but Ordnance maintenance units in MAGNET would bring spare parts and

[89]

special repair tools.7

At the time General Chaney learned of the MAGNET force, the first increment of troops was estimated at 14,000, but ten days later it was reduced to 4,000 in order to accelerate troop movements to the Pacific area. Changes in troop strengths caused by strategic as well as logistic considerations and lack of accurate and timely information made planning difficult for General Chaney's small staff of only twenty-four officers and eighteen enlisted men—a headquarters smaller than that allotted to a regiment. The Ordnance Section in early January consisted of Colonel Coffey and 2d Lt. John H. Savage, a young tank expert who had arrived in London in late November on detached service from Aberdeen Proving Ground. Most of the staff sections had but one officer and one enlisted man. Since late fall of 1941, when new duties had been assigned to SPOBS, General Chaney had been submitting urgent requests for more men, including an Ordnance officer for aircraft armament, but he had not received them. The inability of his overworked staff to handle added tasks was already creating "an extremely grave situation" at the time he learned of the MAGNET plans.8

On 7 January 1942 he asked for fifty-four officers and more than a hundred enlisted men to form a nucleus USAFBI headquarters, all to be dispatched at once because of MAGNET, and all in addition to his earlier requests. This number was the minimum needed immediately. He estimated that the theater headquarters detachment, required eventually to serve the United Kingdom, would need 194 officers and 377 enlisted men.9

The War Department's response to these requests was meager indeed. Though a USAFBI headquarters force had been organized at Fort Dix, New Jersey, in early February, the first increment, six officers, did not arrive in England until 3 April. The second increment, sixteen officers and fifty enlisted men, did not come until 9 May. Brig. Gen. John E. Dahlquist, who was Chaney's G-1, afterward considered that the failure of the War Department to provide personnel for the USAFBI headquarters was "probably the most significant fact about the entire period from Pearl Harbor to ETOUSA." To General Chaney, the lack of personnel was "one of the vital questions in any discussion of USAFBI."10

Colonel Coffey fared little better than other members of USAFBI. He received no additions to his staff from the United States until May, when three officers and nine enlisted men arrived, part of the Fort Dix force. In the meantime he had obtained two officers in London, one a young

[90]

reservist called to active duty, the other an officer from the U.S. Embassy, Lt. Col. Frank F. Reed. Colonel Reed could not at first give his full time to USAFBI headquarters since he had to continue for several months to gather technical information for the military attaché, who was also short of personnel. The lack of adequate coverage in the Ordnance technical intelligence field was a cause of concern to both Reed and Coffey.11 In addition to new responsibilities, the important work of liaison and coordination with the British, begun under SPOBS, was continued. For example, Coffey and Reed spent two days in February at the Training Establishment of the Royal Army Ordnance Corps studying the RAOC, and obtained copies of lectures to send back to the United States to be used in training Ordnance officers who were going to sectors where their functions were likely to be controlled by the British.12

Close coordination with the British was essential in Colonel Coffey's plans for MAGNET, for it was expected that American troops would use the shops and depots near Belfast that were already serving the British Troops in Northern Ireland. The most important were a base depot and shop at Kinnegar, and an ammunition depot on a large, stone-walled estate, Shane's Castle, at Antrim.13

The advance party of the first MAGNET contingent arrived in London on 20 January. It consisted of officers of the 34th Division, a National Guard unit commanded by Maj. Gen. Russell P. Hartle, and included Hartle's divisional Ordnance officer, Lt. Col. Grayson C. Woodbury. Woodbury was briefed by Colonel Coffey and other members of the USAFBI staff in two days of conferences before he departed for Belfast, wearing, in the interest of security, civilian clothing borrowed from Londoners. On 24 January an official announcement was made of the command, which was to be called United States Army Northern Ireland Force (USANIF).14

The first 4,000 MAGNET troops landed in Belfast two days later on a murky, chill, winter day. They were welcomed with flags and bunting, bands, and speeches. They were told by the British Air Minister that they were entering a combat zone, and they were made aware of the fact as they went ashore. Above the sound of marching feet, the cheers, the strains of "The Star Spangled Banner," they heard the crump of antiaircraft batteries firing on German reconnaissance aircraft. For the people of Belfast it was a stirring occasion. Some were reminded of the arrival in

[91]

Northern Ireland of the American Expeditionary Forces troops in 1918.15

The uniforms of the American troops added to the illusion. The men wore the old "tin hats" of World War I. New helmets of the World War II type, an Ordnance item, had been available when the men were equipped, but at General Chaney's suggestion the War Department had provided only the old model 1917 steel helmets because there was a possibility that men wearing the new type, which resembled the German helmet, might be mistaken for enemy troops by Northern Ireland home guard night patrols.16

The possibility of an enemy invasion, probably through neutral Eire, could not be discounted. The operations plan for MAGNET provided a "striking force" to be composed of the 36th and 45th Infantry Divisions and the 1st Armored Division, and a "static," or holding force, composed of the 34th Infantry Division, all under V Corps. Later the 36th and 45th were dropped and the striking force consisted of V Corps troops, the 34th Division, and the 1st Armored Division, under the operational control of the commanding general of the British Troops in Northern Ireland.17

No Ordnance troops arrived with the first contingent, for they had been cut out by GHQ when the first increment was reduced from 14,000 to 4,000, "a serious mistake," according to the GHQ Ordnance officer, Lt. Col. Robert W. Daniels.18 Almost as soon as the first increment landed, the problem of sorting and storing Ordnance supplies led General Chaney to cable for a depot detachment. The movement orders for the second MAGNET contingent departing in February gave a high priority to the 79th Ordnance Depot Company, but the company ran into bad luck when its ship, the USAT American Legion, developed engine trouble at Halifax and had to turn back.19 The only Ordnance troops that came in with the second MAGNET contingent of 7,000 men were those of the 14th Medium Maintenance Company, which was part of V Corps troops, and a 12-man detachment from the 53d Ammunition Company. They had to support the entire MAGNET force, which had now swelled to more than 10,000 men, for more than two months.20

[92]

The 79th Ordnance Depot Company and another medium maintenance company, the 109th, arrived in Northern Ireland less than a week before the largest of all the MAGNET increments came in—the bulk of the 1st Armored Division aboard the Queen Mary—on 18 May. With the 1st Armored Division, Old Ironsides, and additional units of the 34th Division and V Corps that came in the two May convoys, the number of U.S. forces in Northern Ireland was more than tripled, rising to 32,202. To provide a base should the V Corps be assigned a tactical mission, the Northern Ireland Base Command (NIBC) was organized on 1 June 1942, and all of the Ordnance units were assigned to it except the 109th Medium Maintenance Company, which was assigned to the USANIF (V Corps) striking force, and the maintenance battalion that was organic to the 1st Armored Division.21

By 1 June 1942 ammunition depot stocks held approximately five units of fire of all types except armored division. Ordnance organizational equipment was approximately 100 percent complete. Weapons of the 1st Armored Division were being unloaded daily, and by 13 June all of the division's tanks had arrived. Storage facilities were becoming cramped because the British had not departed as expected, but there was plenty of tentage and every day new Nissen huts were taking up more space in the green Irish countryside and on the grounds of ancient estates.22

As of 31 May 1942 most of the U.S. Army ground forces in the British Isles were in Northern Ireland: 30,458 out of a total of 33,106 enlisted men in the British Isles were in USANIF, as were 1,744 out of a total of 2,562 officers.23 However, planning was already under way in Washington for a mammoth buildup in England. In April General Marshall had gone to London and obtained the consent of the British Prime Minister and Chiefs of Staff for a major offensive in Europe in 1943 or for an emergency landing, if necessary, in 1942. The former bore the code name ROUNDUP, the latter was called SLEDGEHAMMER, and the detailed, long-range planning by the Washington staffs for the concentration of American forces in the British Isles was called BOLERO. Until then, Washington planners had been "thrashing around in the dark," as General Eisenhower put it, and plans for the British Isles had gone no further than the garrisoning of Northern Ireland and the establishing of air bases in England for the bombardment of Germany. Now the United Kingdom was to be the main war theater. BOLERO provided for the arrival of a million U.S. troops in the United Kingdom by 1 April 1943.

When Marshall returned to the United States from London he told Eisenhower that General Chaney and other American

[93]

officers on duty in London "seemed to know nothing about the maturing plans that visualized the British Isles as the greatest operating military base of all time." Marshall sent Eisenhower to London to outline plans and to bring back recommendations on the future organization and development of U.S. forces in Europe. After an interview with Chaney, Eisenhower concluded that Chaney and his small staff "had been given no opportunity to familiarize themselves with the revolutionary changes that had since taken place in the United States . . . They were definitely in a back eddy, from which they could scarcely emerge except through a return to the United States."24

It might also be said that in Washington there was widespread ignorance, even at upper levels, as to the true nature of General Chaney's mission in London. General Eisenhower referred to him as a "military observer,"25 and General Eisenhower's naval aide, Capt. Harry C. Butcher, referred to the work of the Special Observer as "essentially a reporting job," rather than "an action responsibility."26 G Brig. Gen. Charles L. Bolté, Chaney's chief of staff, said later that he actually grew to hate the name Special Observer Group, and added, "I do not think that too much emphasis can be laid on the fact that many of the difficulties . . . arose from the misconception that SPOBS was an information-gathering agency, whereas it was really designed as the nucleus for the headquarters of an operational force which might or would matérielize if the United States entered the war."27

Ordnance planning for BOLERO was soon to be taken over by an organization other than Colonel Coffey's staff. General Marshall and General Somervell had decided to establish in England a Services of Supply organization paralleling that in the United States. The officer selected to command it, Maj. Gen. John C. H. Lee, was not given as much power as he wished, but following a long controversy between SOS and USAFBI, complicated by cloudy directives from the United States, he was given the main job of building up stocks of munitions in the British Isles. He selected as his Ordnance officer Col. Everett S. Hughes, who had held for two years the very important job of chief of the Equipment Division, Field Service, in Washington. Hughes arrived in London by air on 8 June with his procurement officer, Col. Gerson K. Heiss, and opened the Ordnance Section at SOS headquarters, 1 Great Cumberland Place. His chief of General Supply, Col. Henry B. Sayler, his maintenance officer, Col. Elbert L. Ford, and his chief of Ammunition Supply, Col. Albert S. Rice, arrived from the United States later in the month.28

When the European Theater of Operations, United States Army (ETOUSA), was established on 8 June 1942, Colonel Hughes as senior Ordnance officer in the theater became the Chief Ordnance Of-

[94]

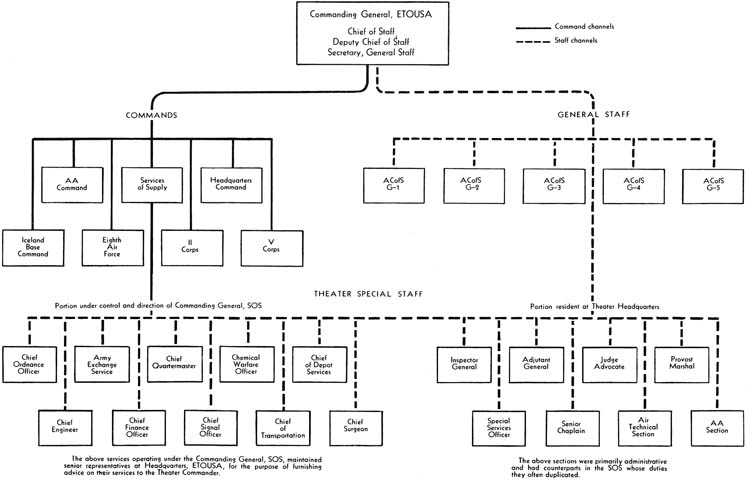

CHART 2 - EARLY COMMAND AND STAFF ORGANIZATION OF ETOUSA ESTABLISHED BY ETO GENERAL ORDER 19, 20 JULY 1942.

[95]

ficer, ETOUSA. (Chart 2) After the establishment of SOS, the Ordnance Section at Headquarters, ETOUSA, was concerned only with planning, technical advice, and liaison, and as Colonel Hughes was mainly occupied with the far greater responsibility at SOS, he appointed Colonel Coffey his special representative at ETOUSA headquarters. Most of Coffey's staff went over to the Ordnance Section of SOS. The two headquarters were soon to be separated by about ninety miles. General Lee had early in June decided to move SOS to Cheltenham, where the British could offer two extensive blocks of buildings, built to accommodate the War Office in the event London had to be evacuated. The additions to the Ordnance SOS staff that came from the United States in mid-July went direct to Cheltenham, Gloucestershire.

General Chaney served as theater commander less than two weeks and General Eisenhower succeeded him on 24 June. In the following month an important change occurred in the Ordnance organization. Colonel Hughes departed for the United States on 10 July, returning to England after a few weeks to become General Lee's chief of staff. His successor at SOS was Col. Henry B. Sayler. Eisenhower's General Order 19 of 20 July 1942 made Colonel Sayler also the Chief Ordnance Officer, ETOUSA.29

Storage for Weapons and Ammunition

The first concern of Ordnance Service, SOS, was the storage of weapons and other general supplies, since it had been decided that for the time being ammunition would be shipped to British depots. The depot system established by General Lee's staff provided two types of depots—general depots that stored supplies of more than one technical service, and branch depots for each service. General depots were mainly for receiving large shipments from the United States, storing them in their original packages, and shipping them in bulk to the technical branch depots for issuance to troops. This was not a hard and fast rule; some general depots issued direct to troops. Branch depots received matériel not only from general depots but also from the zone of interior and from local procurement, and sometimes they served as bulk depots. An important planning consideration was the fact that existing British installations would have to be used because there was little prospect for new construction before 1 January 1943.30

The first Ordnance general supplies to arrive and the only Ordnance SOS depot company that landed in England that summer went to Ashchurch, eight miles from Cheltenham, the largest and most modern of the five U.S. general depots activated on 11 July 1942. Recently built for the British Royal Army Service Corps as a depot for automotive supply and maintenance, it was situated in fertile Evesham Valley at the foot of the Cotswold Hills, fifty-one miles from the Bristol channel ports, through which most of the American supplies were expected to flow. Ten large hangar-type warehouses and five smaller ones provided a total closed storage space of 1,747,998 square feet, of which Ordnance was assigned 378,200, an area second only

[96]

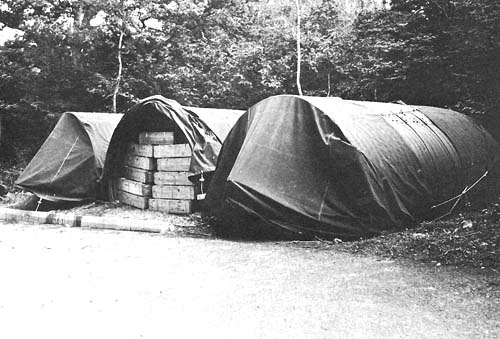

AMMUNITION STORED IN HUTMENTS BY AN ENGLISH ROADSIDE

to the 1,014,200 square feet allotted to Quartermaster's Motor Transport Service. The major warehouses were of brick, with gabled roofs and overhead roller suspension doors. They were connected by macadam roads that were lined with fences painted with yellow and black stripes for better visibility during blackouts. Mists settling over the valley aided camouflage but gave the whole installation a tone that was "peculiarly sombre."31

A decision on the site of the first Ordnance branch depot in England was made early in the summer. On 1 June Lt. Col. David J. Crawford, who had arrived from the United States late in May to reconnoiter for shop and storage space, reported favorably on Tidworth, in southern England, the region from which the British had agreed to withdraw their own troops in order to make way for the Americans. Tidworth was at the southeastern edge of Salisbury Plain, the great chalk downs that served as the main peacetime maneuver area of the British Army. Site of a former British tank and artillery shop, Tidworth had a depot with 133,000 square feet of shop space and 50,000 feet of storage space in two buildings. There were good rail and highway connections and a consider-

[97]

able amount of open shed and garage space. On 22 July Tidworth Ordnance Depot, designated O-640, was activated. Until September, when the 45th Ordnance Medium Maintenance Company arrived, it was operated entirely by British civilians.32

The Salisbury Plain area also contained two of the three British ammunition supply dumps (ASD's) first used for ammunition shipments from the United States— Savernake Forest and Marston Magna. The Third, Cinderford, was in the Forest of Dean near the Bristol ports. The British ASD's were simply areas containing adequate road nets and enough villages to provide railheads. Since the English countryside was too thickly settled to permit depots in the American or Australian sense, the British had stacked ammunition along the sides of roads. If the roads ran through an ancient forest or park with tall trees to hide the stacks from enemy bombers, so much the better; in any case roadside storage made the ammunition easily accessible, an important consideration at a time when fear of German invasion was always present. Each stack of artillery and small arms ammunition was covered by a portable corrugated iron shelter, or hutment, that was usually camouflaged by leaves poured over a wet asphalt coating. Bombs were stored in the open at Royal Air Force (RAF) depots.33

The first U.S. ammunition depots were activated on 2 August 1942 at Savernake Forest (O-675), capacity 40,000 tons, and Marston Magna (O-680), 5,000 tons. At both, troops were to be billeted in whatever buildings were available—the Marquess of Aylesbury's stables, farmhouses, a cider mill, and Nissen huts. But for some time to come, all U.S. ammunition depots had to be operated mainly by British RAOC troops. When large shipments of ammunition began to arrive in late August, more depots were needed. A site surveyed by the British but not yet used was found in the Cotswolds, northeast of Cheltenham. Activated as Kingham (O-670) on 11 September, this depot became by early 1943 the largest U.S. ammunition depot in England. On the same day that Kingham was activated, a fourth depot, O-660, was activated at the British ASD at Cinderford and soon became the second largest U.S. ammunition depot. The sites for these four depots were selected with ground force ammunition in mind. For air ammunition, three main depots of about 20,000 tons capacity each were required in the first BOLERO plan. Two were established in the Midlands, near Leicester and air bases— Melton Mowbray (O-690) and Wortley (O-695), both activated 30 September. The third was Grovely Wood (O-685) in southern England, activated 2 September. In the meantime, SOS began to store bombs and other air ammunition at Savernake, Cinderford, Kingham, and Marston Magna, which then became composite, rather than ground force, depots.34

[98]

Motor Vehicles

The assignment to Ordnance of responsibility for motor vehicles on 25 July 1942, effective 1 September, enormously increased the work of the General Supply Division. At the time it was hard for Ordnance officers in the European Theater of Operations to grasp the magnitude of the new job; compared to weapons, combat vehicles, and fire control instruments, soon to be referred to as "old Ordnance," the very much simpler mechanism of trucks did not at first seem to present much of a problem, especially since Ordnance men were already familiar with parts and maintenance considerations on combat vehicles. Later these officers learned that while general purpose vehicles involved comparatively simple technical problems, the great number of trucks as compared with the number of tanks and Ordnance special vehicles and the incomparably rougher usage automotive equipment received placed a very heavy drain on manpower. In terms of man-hours, automotive equipment was eventually estimated to constitute approximately 80 percent of the whole Ordnance job in the ETO.35

Most of the motor vehicles that had been coming in since late spring had been shipped partly disassembled and crated in order to save shipping space and had been turned over to the British Ministry of Supply for assembly because the theater had no American assembly plants and mechanics to do the work. Two methods of crating were used. The simplest was that which kept each vehicle in its own crate, with the wheels removed. These were called "boxed" vehicles. The crates could be easily stacked and bolted together, as uncrated wheeled vehicles could not. The second method required much more assembly work. It involved two kinds of packing, either one vehicle in one or two boxes, known as the single unit pack (SUP), or two vehicles in from one to five boxes (most commonly, one crate containing two chassis, the second two cabs, the third, axles), known as the twin unit pack (TUP). The SUP and TUP types were called "cased" vehicles.

The TUP method, which saved about two-thirds of the space required for an uncrated vehicle, was far more economical in space than the SUP method and came to be preferred, especially for the 3/4-ton, 1 1/2-ton, and 2 1/2-ton types. However, the TUP method of crating contributed to early confusion on how many vehicles there were in the theater, of what types, and where they were located. Often all three crates did not come on the same ship: one vessel would carry the cabs and chassis and another would carry the axles; and the two ships might dock at different ports. Sometimes the crates were not marked and had to be sent to an assembly plant and opened before their contents could be determined. Then they would have to be rerouted to the assembly plant designated to handle the particular type of vehicle.36

[99]

The vehicles were assembled in British civilian plants under the direction of the British Ministry of Supply, an arrangement that had been made when vehicles were a Quartermaster responsibility. The code name for the assembly work was TILEFER. By 11 July 1942 the Ministry's TILEFER organization had two assembly plants in the Liverpool area, the Ford Motor Company at Wigan and Pearson's Garage in Liverpool, and plans for others were under way. After cased and boxed vehicles were assembled and the few wheeled vehicles that arrived (only about 20 percent of the total) were reconditioned, the British drove them to large parking lots, which they called vehicle parks, to form pools from which troops could be supplied. Two of these parks, Aintree Racecourse and Bellevue, were near Liverpool. A third was at Ashchurch (G-25).37

Ashchurch suddenly became important to Ordnance planners when they learned that motor vehicles were to be added to other Ordnance responsibilities. Quartermaster's Motor Transport Service had planned to make Ashchurch a primary overseas motor base, operated by three regiments—a depot regiment, a supply and evacuation regiment, and a base shop regiment. The first unit of this large organization, which had been recruited from automobile plants, steel mills, and machine shops in the United States, arrived on 19 August, but since its equipment did not arrive until December, the men were assigned various duties, the most important of which was operation of the vehicle park. A tire repair company, the first of its type to be organized, also arrived at Ashchurch during August without equipment. It was given the job of operating the three gas stations and grease racks.38

The vehicle parks already in existence at Ashchurch and in the Liverpool area were adequate in the early summer. Few vehicles were coming into the ports, and those that did arrive were likely to be held up in assembly plants that were not yet in full operation. Only 526 general purpose vehicles were assembled by the British in July. Yet more vehicle parks would soon be needed. General Eisenhower had informed General Lee that the War Department was contemplating shipping approximately 160,000 knocked-down vehicles in the early fall.39 While this figure was overoptimistic, the rate of arrival and assembly did rise sharply in late August and early September. By the end of 1942 the Ministry of Supply had assembled a total of 33,362 vehicles. Twelve vehicle parks with a total of 23,000 vehicles had been activated: in the Liverpool, Bristol, and Glasgow port areas as near TILEFER assembly plants as possible; in the east of England near air installations; and in the south of England where ground troops were concentrated. They were located on estates, on race tracks, and on other open areas that had enough space and adequate camouflage. Little or no construction was possible at any of the sites

[100]

because neither the Engineer Corps nor local labor was available and for some time operations would depend almost solely on British personnel, military and civilian.40

The officers to command the vehicle parks were six men of Motor Transport Service's TILEFER Section, who were transferred to Ordnance on 1 September when a total of 14 motor transport officers and 27 enlisted men came into the Ordnance Service, SOS. These six men, particularly those who had been trained in the TUP program, were considered by the Ordnance Section to be some of the best officers in the theater. But they were few in number —three officers commanded two vehicle parks each. Four of the parks were for some time to come commanded by British officers.41 Besides the Quartermaster motor base and tire repair companies at Ashchurch, Ordnance received eleven Quartermaster companies and the large motor transport depot at Rushden, Northamptonshire, serving air installations. Rushden was designated O-646, becoming, with Ashchurch and Tidworth, one of the three primary Ordnance installations.42

At the time Ordnance received responsibility for motor vehicles in the theater, the shortage of commissioned officers, which had been a problem since SPOBS, was becoming acute. Ordnance officers were needed not only at depots, shops, and schools in the United Kingdom but also at ports and at three of the four base sections that were just being established: the Northern Ireland Base Section, which took over from the Northern Ireland Base Command; the Western Base Section, which included the ports of Glasgow and Liverpool; and the Southern Base Section, the concentration point for ground forces units in southern England. The Eastern Base Section, mainly concerned with services to the air forces, had no Ordnance section for some time.43

While base sections, depots, and shops were passing from the planning to the operating stage, with their efforts directed toward BOLERO, decisions were being made in London and Washington that were suddenly to change the direction of the effort and to accelerate tremendously the pace of the operations. By 25 July pressure on the Allied Powers to establish a second front before the spring of 1943—the date set for BOLERO—had led to an agreement by the Combined Chiefs of Staff to undertake an invasion of North Africa in 1942, an operation to be known as TORCH.

Weeks of discussion followed on where and when the landings would take place. By 5 September the decision was reached to make three simultaneous landings: one at Casablanca by a Western Task Force, mounted and shipped from the United States; another at Oran by a Center Task

[101]

Force, predominantly II Corps; and a third at Algiers, by an Eastern Task Force, mainly British. Center and Eastern Task Forces were to be mounted from the British Isles. The target date was unsettled for some time, varying from mid-October to early November. By the time the tactical plans were firm enough to furnish a definite troop basis, there were only about two months to plan, organize, collect supplies, process troops, train for amphibious landings, and embark.44

General Eisenhower was made commander in chief of the expedition. At Allied Force Headquarters (AFHQ), which was in charge of both logistical and operational plans, a British officer, Maj. Gen. Humfrey M. Gale, was to control logistical planning. His deputy, Colonel Hughes, became responsible for the U.S. supply program for TORCH in the British Isles. Colonel Ford, Sayler's maintenance officer, became Ordnance officer of AFHQ and took with him several members of the SOS staff, including his assistant, Colonel Crawford. Headquarters, ETOUSA, lost a valuable officer to the Mediterranean operation when Colonel Coffey left for the United States to help prepare Western Task Force. Center Task Force Ordnance planning was in the hands of Col. Urban Niblo, who had arrived in England that summer as Ordnance officer of II Corps, then commanded by Maj. Gen. Mark W. Clark. Later, Clark became Eisenhower's deputy and relinquished command to Maj. Gen. Lloyd R. Fredendall (II Corps' old commander), who joined the planning group on 10 October.45

Planning began in London in August in an atmosphere of great secrecy. The staff was literally locked up in Norfolk House; officers could leave the building, but enlisted men, both British and American, were confined to the building until the landing was made. The chiefs of technical services received little or no information on the size of the force or the location of the operation. Strenuous efforts were made to maintain security and mislead the enemy. For example, the British in attempting to indicate that the first convoys were going to India ordered typhus and cholera vaccine, which British forces used only in India, and made a point of losing one or two of the vaccine shipments so that the losses were known. The effort to confine knowledge of the "Special Operation" to as few persons as possible also had undesirable effects. It deprived Ordnance planners of staff help that they needed. Lacking staff men to check their requisitions back to the zone of interior, Colonel Hughes and Colonel Niblo inadvertently requisitioned ammunition for the old French gun of World War I, the 155-mm. GPF, instead of the 155-mm. Mi with which II Corps was equipped. As a result, the 155-mm. M1 guns had to be left behind in England and could not be used in

[102]

the initial phases of the North African campaign.46

In the Center Task Force and the small U.S. contribution to Eastern Task Force there would be 80,820 American troops, including the 1st Infantry Division, then in southern England, and the 34th Infantry and 1st Armored Divisions, in Northern Ireland. The job of equipping this force fell to SOS headquarters at Cheltenham. The base sections were as yet hardly more than skeleton organizations. No accurate figures on supplies existed, for there had not been time to catalogue the mountains of equipment that had been dumped in the British ports during the summer. It was known, however, that some Ordnance items such as spare parts for tanks and some calibers of ammunition were not available. And it was probable that there were not enough spare parts for motor vehicles. Nobody knew how many trucks were in England.47

On 8 September General Eisenhower sent the War Department a requisition for 344,000 ship tons of matériel for the North African operation, most of it to be shipped to the United Kingdom by 20 October. In Washington General Lutes of SOS, who had visited England in the late spring and had been concerned about the lack of U.S. service troops there to receive, sort, and identify U.S. matériel, believed that most of the II Corps equipment was already in the United Kingdom, but was scattered throughout England and unidentified. Dismayed at the prospect of having to duplicate shipments that he was convinced had already been made, he urged the SOS staff in the ETO to "swarm on the British ports and depots and find out where these people have put our supplies and equipment."48

While undoubtedly some Ordnance items had been "lost" because of misrouting or improper marking, it is unlikely that Ordnance matériel in sufficient quantity would have been uncovered even if there had been enough trained depot men to "swarm" efficiently. The Ordnance SOS staff believed that there were not enough Class II and IV supplies in the United Kingdom to support the first phase of TORCH. Most of the BOLERO cargo shipped to England in July and August of 1942 consisted of Quartermaster items (including boxed vehicles) and construction equipment and special vehicles for the large contingent of Engineer troops sent to build airfields, camps, and depots. There was also a considerable backlog of Army Air Forces matériel for units shipped early in June. Requisitions forwarded to the New York Port of Embarkation by the SOS Ordnance Service in July to build up the level of supply had been canceled in view of the current task force movements; the only Ordnance Class II and IV matériel arriving in the summer consisted of automatic shipments of 180 days of maintenance supply, based on the addendum and the number of major items shipped to the ETO with the early units. Until the 1st Infan-

[103]

try Division arrived early in August, there had been no ground combat forces in England. The division's weapons were not preshipped; at the time, vehicles were the only item of organizational equipment preshipped in sizable numbers.49

When the call came to support TORCH, the 1st Division had not received any of its field artillery and had only fractional allowances of machine guns and special vehicles. The fault lay in the system of sending men on transports and their organizational equipment on cargo ships, sometimes in different convoys, sometimes arriving at different ports. The problem of marrying units with equipment was not a simple one at best, as the experience in Australia had shown. In the case of TORCH, where time was all-important, the situation bordered on chaos. Two ships that had set out from the United States with 105-mm. howitzers for the 1st Division had failed to arrive; one went aground in Halifax Harbor, Nova Scotia, and the second, sent to replace the first, had to put in at Bermuda because of shifting cargo. On 12 September General Clark told Colonel Hughes that something would have to be done quickly or "those men will be going in virtually with their bare hands." Of the ground forces in Northern Ireland, the 34th Infantry Division had only old-style howitzers and lacked antiaircraft equipment and tanks; the 1st Armored had only the old model Grant M3 tanks.50

Even if there had been enough guns, it was doubtful whether enough ammunition had been provided. At the end of August only 21,040 long tons of ground force ammunition were in the theater and on 14 September Colonel Hughes was forced to admit that he had no assurance of an adequate ammunition supply for TORCH. A very large proportion of the early ammunition shipments had been bombs. A great deal of the artillery ammunition had arrived so damaged, because of poor packing, stowing, and handling at shipside, that it was unserviceable; moreover, in the ammunition depots the manpower problem was as acute as it was in the general supply depots. Only two ammunition companies arrived in August, the 58th and 66th. Both stationed at Savernake, they were undermanned because they had to furnish detachments for other depots. In addition, their men had not been sufficiently instructed in renovation, roadside storage, and operating at night under blackout conditions. Between 12 September and 20 October a few Quartermaster motor transport men and about 2,500 Engineers were assigned to help, but without the trained RAOC men, issue and supply would have been almost impossible.51

In attempting to fill the huge requisition of 8 September and subsequent ones, the SOS staff in the zone of interior was hampered not only by lack of ships but by the need to supply the very large Western Task Force then being mounted from the United

[104]

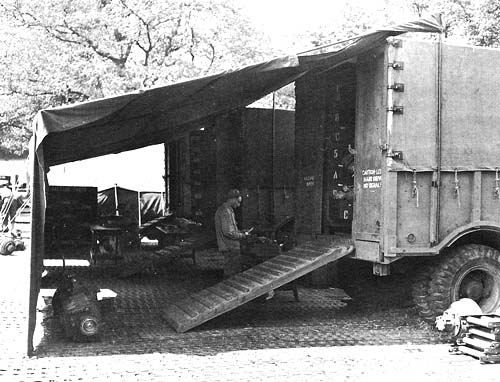

TRAILER SUPPLY UNIT IN ENGLAND

States. Working night and day in the effort to fill General Eisenhower's needs, SOS USA was able to send 131,000 ship tons of equipment to England and to add eight fully loaded cargo ships to the convoys by the time they sailed for North Africa late in October. It was 1 October before the first of the freighters sailed. In the meantime, the Ordnance Section at SOS ETOUSA did its best to supply the alerted TORCH units from stocks in the theater.52

All depots were combed for Ordnance supplies. They were found in Quartermaster, Engineer, and Medical depots, mixed with all sorts of other matériel. In one instance, two 90-mm. guns were found in a Quartermaster depot. The depots worked 24-hour shifts, since manpower was still spread thin. A second Ordnance depot company, the 78th, assigned to II Corps, arrived in mid-September and was divided between Tidworth and Ashchurch, but it never received any of its table of basic allowances equipment and could not be used to best advantage. Working against time, the depot men found enough

[105]

replacement spares in the theater's maintenance stocks to supply major items. Spare parts, for which there was a constant clamor, presented a far more difficult problem, especially in the case of general purpose vehicles. At the time, spare parts were shipped overseas in boxed lots, that is, they were boxed in quantities that were thought to be sufficient to supply a hundred trucks for the first year. The contents varied and sometimes did not contain enough fast-moving parts, such as spark plugs. For some vehicles there were not enough boxed lots. To supply the thousands of 2 1/2-ton trucks in the theater, less than one boxed lot was received by the end of 1942. The only solution was the dismantling of new 2 1/2-ton trucks in TUP boxes. Approximately 75 were dismantled at Tidworth and the parts boxed and shipped to North Africa.53

Almost all of the uncrated vehicles had arrived short of tools. The British supplied some tool sets for trucks, but their use was limited because tools were based on British vehicles, which used many nuts and bolts of sizes different from those used in American trucks. Tools for the repair of "old Ordnance" matériel were even harder to obtain, and those that arrived were often pilfered. Ordnance shop trucks arrived assembled, and, entrusted to British drivers on the journey from port to depot, were frequently rifled. The commanding officer of the 105th Ordnance Medium Maintenance Company estimated that 22 out of 23 shop trucks received in the first six weeks after the company's arrival in the theater had been "effectively robbed"; and this was only one of many such reports. The Ordnance Procurement Division did obtain some other supplies from the British, but local procurement was limited mostly to hardware, target material, some parts common, and cleaning and preserving material, including that used for waterproofing.54

The new problem of waterproofing material to enable trucks and tanks to swim to the shore after they left the ramps of landing craft became increasingly-important as preparations accelerated for a major amphibious landing. Here the British helped greatly, for they had developed a compound that would seal the vital parts of vehicles and yet could be easily stripped off after the landing. Using this compound to seal engines, electrical systems, and running gear, and affixing metal and rubber tubing to extend exhaust and intake outlets above the water, Capt. Madison Post of the newly established Ordnance Engineering Division, SOS ETOUSA, by 20 October evolved a means of operating trucks in three feet of salt water for a short period. Waterproofing tanks seemed simpler to the combat forces, because the enveloping hull of the tank made it unnecessary to waterproof each individual component, but Ordnance officers thought it considerably more complicated, since the hull had to be made

[106]

watertight, and it had many openings. To keep the engines from being flooded, metal "fording stacks" extending above the water had to be fitted on the exhaust pipes. Because the stacks interfered with the traverse of the turret they had to be quickly jettisoned after the landing so that the tanks could go in shooting. Working closely with the British, Ordnance officers rounded up large quantities of waterproofing material—metal tubing, rubber garden hose, sealing compounds, and a few British waterproofing kits—and arranged for shipment of the material to Ballykinler, Ashchurch, Tidworth, and other places where American troops were preparing for the North African landings.55

The North African venture began from the United Kingdom on 22 October 1942, when a cargo convoy of 46 vessels left British ports with supplies for the Center and Eastern Task Forces. On 24 October a second cargo convoy of 51 vessels sailed, and on 26 October and 1 November the first two troop convoys, of 41 and 17 vessels, respectively, departed with 68,463 American and 56,297 British troops. After that, convoys left the base in the British Isles at intervals of approximately one a week through December. The first ten cargo convoys carried among them 288,438 long tons of cargo, of which more than a third was Ordnance matériel. Food and clothing and similar Quartermaster supplies constituted the largest amount of tonnage, 35.2 percent of the whole; vehicles were next, 28.2 percent. Engineer supplies accounted for 12.8 percent, "old Ordnance" for 11.1 percent, gas and oil, 7.9 percent. Other technical services—Medical, Signal, and Chemical Warfare—had less than 1 percent each.56

As the first assault elements headed out into the Atlantic in a high wind and heavy sea, zigzagging south in a wide arc, Colonel Sayler in London began to assess the Ordnance effort in mounting TORCH. There were two serious causes for concern—vehicles and spare parts. The troops did not have their full table of equipment complement of trucks because it took too much shipping space to transport wheeled vehicles. The units could take only about 60 percent, with the promise that the other 40 percent would be shipped to North Africa in crates and assembled there. They did not have enough spare parts of certain kinds. The supply of automotive spare parts in the theater had been unbalanced: there had been sufficient for some makes of vehicles and practically none for others. To a certain extent the shortage was caused by shortages in the United States, but it was also attributable to confusion at the New York Port of Embarkation. Enough

[107]

major items for maintenance purposes had been furnished (on a 45-day basis, however) and on the whole, though some major items had been cannibalized to provide spare parts, Colonel Sayler thought the forces departing for North Africa were well equipped with Ordnance general supplies.57

Ammunition supply officers believed that units of the Center and Eastern Task Forces had been supplied with sufficient ammunition from British depots. Shortages of certain types, notably antitank mines, hand grenades, and pyrotechnics, had been filled by procurement from the British.58

In supplying arms, vehicles, and ammunition for TORCH; Colonel Sayler's main problem, like that of Colonel Holman in Australia, had been lack of enough men to do the job. At headquarters the staff had to work far into the night, or all night, to meet the time schedule since it was 50 percent understrength in officers, and the depots and shops were in the same condition. In the field, where autumn rains made seas of mud out of vehicle parks and ammunition depots, Ordnance troops of all kinds worked at whatever jobs had to be done. From Rushden in late September and early October a depot company and a maintenance company were sent to unload ammunition at Braybrooke; at Ashchurch a weapons maintenance company worked on motor transport. Engineer troops and, later, field artillery troops had to be borrowed to help the TILEFER organization operate vehicle parks. The British Army continued to help. As preparations quickened in late September, for example, 50 skilled packers and craters were sent from the Hilsea RAOC depot to help with the work at Ashchurch. Ordnance officers gratefully acknowledged the debt they owed the men of the Royal Army Ordnance Corps for help on general supplies and on ammunition.59

The cables and letters sent from the British Isles in the fall of 1942 had a familiar ring to Ordnance officers in the United States, for in many respects they dealt with the same problems that were stressed in cables and letters from Australia. They had the same urgency and often showed the same lack of comprehension of the problems at home—the demands of many theaters for limited stocks, the upheaval caused by the new responsibility for motor transport, the creaks and strains of a war machine just getting into gear. It was perhaps inevitable that theater commanders were affected by what General Marshall called "localitis"—a local instead of a global view of the war. To commanders in North Africa early in 1943 Marshall talked of Americans fighting in water to their waists in the swamps of Guadalcanal and New Guinea. His listeners were sure that when he flew to the Southwest Pacific he would emphasize the "tough going" Americans were encountering in North Africa.60

[108]

Return to the Table of Contents

Last updated 11 January 2007 |