CHAPTER II

TROOP MOVEMENTS, DISPOSITIONS, AND LOCATIONS

While the advance party secured Atsugi airstrip and made arrangements for the landing of additional troops, the 11th Airborne Division on Okinawa prepared itself for airlift to Japan. Its first echelon began landing at Atsugi early on the morning of 30 August, and troop and cargo-carrying aircraft continued to arrive at three-minute intervals throughout the day.

Immediately upon his arrival, Maj. Gen. Joseph M. Swing, Commander of the Division, conferred with Lieutenant General Arisue, making final arrangements for the arrival of General Eichelberger and later, General MacArthur.1

Simultaneously with the development of this airhead at Atsugi, elements of the Third Fleet anchored in Sagami Bay supported the landing of the 4th Regimental Combat Team of the 6th Marine Division at Yokosuka. The First and Second Carrier Task Forces (Task Forces 39 and 38) patrolled the coastal waters of the Empire, prepared to make a show of force if necessary.2 Forts and shore batteries on Futsusaki, a narrow spit jutting out from the eastern shore into Uraga Strait, were occupied by small landing parties.3 The main Fleet landing party went inland and established headquarters at Yokosuka Naval Base. While United States forces were securing these important points in the Area of Initial Evacuation, not a shot was fired, although the Marines, like their airborne counterparts at Atsugi, took no chances and were ready for immediate combat should there be the slightest attempt at deception by the Japanese. It soon became apparent that the Japanese had meticulously followed the requirements stipulated in Manila.4 The area had been cleared of all military personnel except for a small detachment which policed and guarded the area. Coastal defenses and antiaircraft had been demilitarized and were marked with white flags which were visible for some miles. Courteous Japanese officers and guides were available for further instructions.5

In the missions outlined in "Blacklist," Eighth Army was assigned responsibility for occupying the Tokyo Bay area.6 Therefore,

[28]

upon landing at Yokosuka, the Marine forces came under the command of General Eichelberger. Hardly had the Marines established themselves when an infantry patrol from the 11th Airborne arrived from Atsugi to effect contact. The liaison patrol was from the 511th Parachute Infantry of the 11th Airborne, a unit which, after landing at Atsugi, had moved eastward to secure the Yokohama dock area in preparation for large scale amphibious landings in that vicinity.

Throughout the morning and early afternoon of 30 August the big transport planes continued to arrive in steady succession at Atsugi. When General Eichelberger arrived approximately six hours after the first troops, his paratroopers sent up a great shout of welcome. He waved back to them saying, "This is the beachhead where I was supposed to land in the invasion of Japan. General MacArthur gave me this area. I certainly never expected to get here by plane without a shot being fired."7 General Swing briefly reviewed the situation for him and introduced General Arisue. They discussed plans for the reception of General MacArthur and his party expected later that afternoon. General Arisue suggested that he act as guide, but the Eighth Army Commander directed him to proceed at once along the proposed route to check security measures and then to remain in Yokohama.8

Near the administration building on the far side of the Atsugi airfield, some anxious-to-please Japanese armed guards were saluting every American who passed within yards of them. Meanwhile, regiments of the 11th Airborne were establishing their headquarters near the airfield. Units of the forward echelons of GHQ and Headquarters, Fifth Air Force, were arriving by plane and were loading equipment to be used for an operating headquarters into the nondescript trucks which the Japanese had assembled. "Manpower" was as important as "horsepower," as one after another of the worn-out vehicles broke down on the road between Atsugi and Yokohama. For the first time, the occupying forces could see for themselves to what straits the Japanese nation had been reduced by the prolonged and exhausting war.

Shortly before 1400 there was a stir of excitement. A strong contingent of newspapermen, photographers, and newscasters swarmed to witness the arrival of the Supreme Commander. As the General stepped from the plane he was greeted by Generals Eichelberger and Swing and cheering veterans of the 11th Airborne Division to whom he said "Melbourne to Tokyo was a long road but this looks like the payoff."9

General MacArthur paused only a few moments at the airfield, then stepped into a

[29]

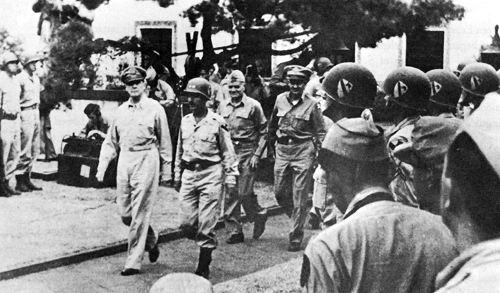

General R. L. Eichelberger, at right, with Maj. Gen. J. M. Swing, Commander, 11th

Airborne Division, receives the report of Japanese officers at Atsugi airfield,

during the initial landings.

General Eichelberger greet General MacArthur at Atsugi airfield.

PLATE NO. 11

The Occupation Begins, 30 August 1945

[30]

waiting automobile to go on to Yokohama where temporary General Headquarters were being established. General Arisue had assured General Swing that requirements presented to the Japanese emissaries in Manila had been fulfilled and the route was safe.10 The fifteen miles of roadway between the airfield and the New Grand Hotel were lined with thousands of armed Japanese soldiers and policemen. They stood at attention but faced away from the road, an additional security measure which was customarily used only for the movements of the Japanese Imperial family. In spite of these elaborate preparations, the Americans took no chances. The Honor Guard Company of the 3d Battalion, 188th Para-glider Infantry, had taken the precaution of guarding the entire length of the Atsugi-Yokohama road.

Units of the forward echelon of GHQ managed to move most of their equipment to the Yokohama Customs House for the establishment of GHQ. But before unpacking was thoroughly under way, orders were given to unpack only the essentials needed to carry on for a few days. It was General MacArthur's intention to move his staff and his headquarters to the capital itself as soon as reports had been received on suitable sites for billets and offices. Eighth Army Headquarters staff likewise set up a temporary arrangement preparatory to moving into the Customs House which it was to occupy when GHQ transferred to Tokyo.

By the end of the day, 4,200 troops and 123 planes had completed the move from Okinawa.11 Weary troopers dropped their gear in assigned areas and the rattle of mess kits replaced all other sounds. It was a peaceful sound and one which few men of the 11th Airborne Division had expected would characterize their descent upon the home soil of Japan.

At the New Grand Hotel the Supreme Commander had his evening meal in the company of news correspondents and his ranking generals. It was a democratic gathering and the meal was a simple one-hamburgers and grapes.12

The weather turned against the Occupation plans during the night. Okinawa dispatched only eight airloads for Atsugi airfield; nevertheless, this lift was sufficient to bring forward the remaining elements of the 511th Parachute Infantry, and the regiment was able to establish its command post that day in Yokohama. There were now more than 2,000 occupation troops within the confines of the city.

In spite of the bad weather, ground operations continued. Patrols ranged out to Asano and Yokohama docks, through the bombed industrial city of Kawasaki and up to the Tama River on the outskirts of Tokyo. No incidents were reported. The 187th and 188th Para-glider Infantry Regiments dispatched men to scout the Hayama-Misaki area (guarding the entrance to Tokyo Bay and west along Sagami Bay as far as Odawara.13 They reported these areas completely cleared. Everywhere women and children ran into hiding, while men and boys saluted and bowed at the approach of the paratroopers. There was no sign whatever of civil disturbance or Japanese resistance. During the afternoon a reinforced company from the Third Fleet Landing Force occupied Tateyama Naval Air Sta-

[31]

tion on the east side of Tokyo Bay. It was anticipated that this area would be occupied by the 112th Regimental Combat Team. To prepare for this, the Marine unit planned a reconnaissance of the whole area on the following day.

The first airshift of occupation troops within Japan took place on 1 September. The reconnaissance troop of the 11th Airborne Division was transported by plane across Tokyo Bay and to Kisarazu airfield where it secured both the field and surrounding installations.14 Meanwhile, the 1st Cavalry Division and 112th Cavalry RCT, under the XI Corps, arrived in Sagami Bay and prepared to land the 1st Cavalry at Yokohama on 2 September, and the RCT at Tateyama (Chiba Peninsula) on 3 September.15

The Japanese had been repeatedly told through official communiques during the course of the war that American naval strength had been reduced to impotency. Consequently, the tremendous collection of seapower anchored in Tokyo Bay in preparation for the official surrender ceremonies must have been a shocking and sobering sight.16 By evening preparations were complete for the ceremonies which were to take place at 0900, 2 September 1945, aboard the USS Missouri.

Occupation operations did not pause even for that historic event. An umbrella of 400 B-29's and more than 1,500 fleet carrier planes circled above the bay. At the same time, while the surrender document was being signed aboard the battleship,17 Task Force 33 arrived in Tokyo Bay with the first elements of XI Corps. By noon the leading elements of this force, which was under the command of Maj. Gen. William C. Chase, began to debark. Approximately 3,000 men were landed and by early evening the convoy to the assigned divisional assembly areas of Hara-Machida had begun. The 112th Cavalry RCT also arrived with the leading elements of XI Corps but remained afloat until the following morning.18

That historic day witnessed numerous other developments of vital importance to the Occupation. Immediately after the signing of the surrender document, the Supreme Commander issued Military and Naval General Order Number 1 to the Japanese. It was based upon the "United States Initial Post Surrender Policy for Japan"19 and confirmed the general

[32]

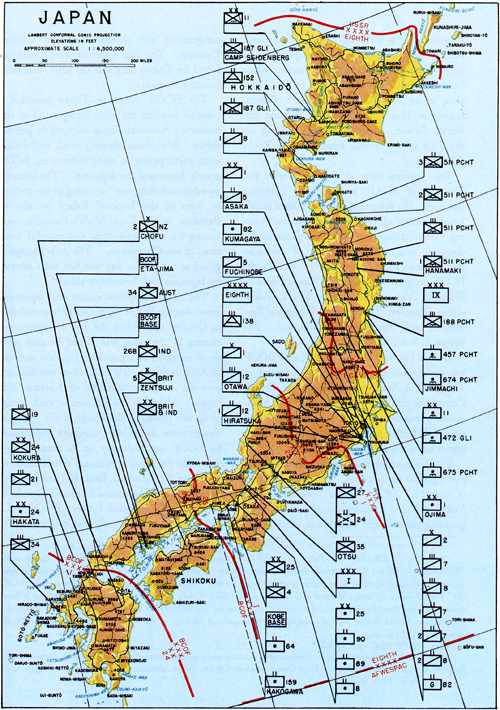

Japanese Delegation, headed by Foreign Minister Shigemitsu and

General Umezu, on board the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay.

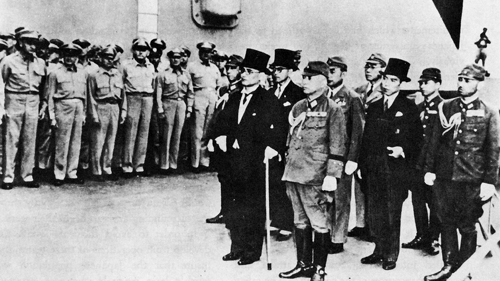

General MacArthur takes position before a microphone as the Japanese general signs

the Surrender Document. In the rear of the Supreme Commander stands Lt. Gen.

Jonathan Wainwright, defender of Corregidor until its fall in May 1942.

PLATE NO. 12

MacArthur takes the Surrender, 2 September 1945

[33]

requirements which had been outlined to the Japanese emissaries at Manila two weeks previously. The order called upon the Imperial General Headquarters "...by direction of the Emperor and pursuant to the surrender to the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers...", to order the Japanese forces to surrender themselves and their arms to designated representatives of SCAP in various parts of the Pacific Theater and China.20 The Japanese police force was initially exempted from the general disarmament and was ordered to remain on duty for the preservation of law and order, for which it would be held responsible. The Japanese Government was directed to provide detailed information about the armed and economic resources of the country. The safety and well-being of prisoners of war and civilian internees was specifically demanded and all pertinent records were required immediately. The Japanese were to be prepared to deliver all such persons to Allied authorities.

To permit maximum concentration upon the immediate occupation problems in the Japanese main islands and Korea, responsibility for implementation of surrender and subsequent operations in all other Pacific areas was considered outside the province of SCAP. The following commands were dissolved: Allied Land Forces, Allied Naval Forces, and Allied Air Forces. For surrender purposes the British Empire assumed control of certain portions of the Southwest Pacific Area, the Netherlands East Indies, and Australian and New Zealand Forces in the East Indies, south of the Philippines and Manus Island.

Immediately after the surrender ceremonies were concluded, Eighth Army Headquarters authorized the dispatch of several "mercy teams," organized in early August for the recovery of Allied prisoners of war and internees. These units landed at Atsugi on 30 August and established themselves in Yokohama, impatiently awaiting the order which would permit them to fan out rapidly through the surrounding areas to begin their work.21

In order to avoid incidents which might develop from operations of these teams and to insure that the Japanese population would quickly learn precisely what was expected of them, GHQ, SCAP, did not depend solely upon General Order Number 1. People were informed directly through existing newspaper and radio facilities.22 This action was also expected to serve as an automatic and effective check against the recurrence of militaristic or ultra-nationalistic propaganda. After screening by the Counter Intelligence Corps, civilian personnel recommended by the Japanese as being trustworthy and pro-democratic in their beliefs were retained to assist in dissemination of news and information from GHQ. Initially Domei and Joho Kyoku news agencies and the Japan Broadcasting Corporation were utilized and administered by GHQ.23 Orders were issued that all Japanese outbound international

[34]

news services to unoccupied areas would originate from Tokyo. GHQ, SCAP, would authorize through its established agencies the use of all world news and pictures published or broadcast in Japan. News releases would be supplied by the Office of War Information in continental United States. Japanese radio stations picked up OWI broadcasts directly from San Francisco, Hawaii, Saipan, and Manila.24

Japanese radio and newspapers might freely use news originating within Japan provided:25

I. Nothing was disseminated prejudicial to public order and safety, including criticism of surrender terms and Allied control measures.

2. No suggestion was imparted of disunity in Allied Powers policy toward Japan.

3. No praise or pity was expressed for Japanese into custody by Allied authority.26

4. No promises were attributed to Allied Power, excepting basis of direct textual quotations from official documents reported without comment or interpretation.

5. Files of all publications were maintained for Allied inspection.

It was decided also that motion picture shows would be temporarily suspended pending review by censorship authorities.27

Eighth Army assumed responsibility for the Area of Initial Evacuation but functioned through the Japanese Government. The task of allocating areas, facilities, and equipment to occupation agencies was also placed under its jurisdiction. The only exceptions to this arrangement were the Yokosuka Naval and Air Bases which were assigned to the Navy. Boundaries were later fixed by agreement between the Eighth Army and the Navy. The Eighth Army Commander allocated the Atsugi airdrome and surrounding territory to the Far East Air Forces, and made available to General Headquarters those facilities requested through its representatives.

On 30 August GHQ, AFPAC, issued an amendment to the last operations instructions. This amendment materially altered the missions assigned to the Army commanders. Instead of actually instituting "military government," Army commanders were to supervise the execution of the policies relative to government functions which GHQ, AFPAC, was to issue directly to the Japanese Government.28 Likewise, the functions of the armies with respect to the disarmament and demobilization of the Japanese armed forces were changed from operational control and direction to supervision of the execution of orders, as transmitted to the Japanese forces by GHQ, AFPAC. In contrast to the original concept, the Japanese Government and its armed forces were required to shoulder the chief administrative and operational burden of disarmament and demobilization.29 The new plan was designed to avoid possible incidents which might result in spo-

[35]

radic conflict.

On 3 September, GHQ, SCAP, issued Directive Number 2.30 It was a comprehensive document, the basic authority for the Occupation of Japan by Allied Forces. Among its numerous provisions was an order to the Japanese Imperial Government and the Japanese Imperial Headquarters, to comply with all the outlined requirements, to assure prompt and orderly establishment of the Occupation forces, and to establish specific controls over disarmament and demobilization of Japanese armed forces.31

To facilitate the Occupation of Japan by the two United States Armies, this Directive specified that the boundaries of the First Japanese Army (Group) would be adjusted to coincide with those of the Eighth U.S. Army. Similarly, the boundaries of the Second Japanese Army (Group) would coincide with those of the Sixth U.S. Army. As specified by the Directive, the Commanding General of the First Japanese Army (Group) reported to General Eichelberger for instructions. General Eichelberger directed him to notify all Japanese military commanders and civilian officials that, beginning with 6 September, they could expect United States reconnaissance parties to travel throughout their areas. Following this, the occupying troops would move in. Seventy-two hours' advance notice of a reconnaissance party's arrival in a particular area and forty-eight hours' notice of the movement of troops would be given. These detailed arrangements would permit the Japanese commanders to disarm their units prior to arrival of occupation forces and to restrict them to barracks or camp areas, thus reducing the possibility of any clashes.

The Commanding General of the Second Japanese Army (Group) reported to the Sixth U.S. Army Commander. At the same time, a senior representative of the Chief, Japanese Imperial Naval General Staff, reported to a designated naval representative for instructions covering the entry of United States naval forces into Japanese and Korean waters and naval establishments.

The 112th Cavalry Regimental Combat Team landed at 0930 on 3 September near Tateyama Bay naval air station and established control over coastal defenses. Immediate contact was made with the 11th Airborne Division reconnaissance troop which was patrolling north to Chiba and south to Tateyama. Control of the 112th Cavalry RCT passed to the 11th Airborne Division.

Four years of bitter warfare had taught the American soldier that appearances where Japanese were concerned could be fatally deceptive. As patrols pushed out to the Yokohama-Tateyama area, carbines were ready and faces were grim, despite the fact that Japanese men and boys continued to salute respectfully. Here is what an official situation report had to say of the period:32

No hostile military or civilian action during period as 112th RCT landed Tateyama where 1,600 armed troops were reported: Jap Army, Navy and State Dept officials met our forces and agreed to stipulation of the surrender. 11th A/B Div and Fleet Landing Force continued to patrol area of responsibility with no reported unusual incidents. CIC Detachment and Japanese Civil Police completed investigation of 2 Jap civilians found dead vicinity Grand Hotel, Yokohama, 1 Sep. Japanese Police satisfied deaths not result any American action.

[36]

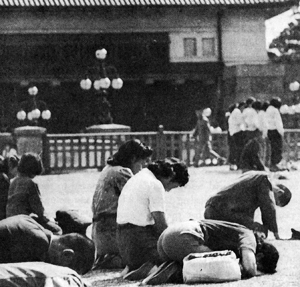

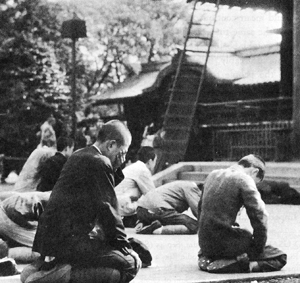

Prayers at the Imperial Palace

Prayers at Yasukuni Shrine, Tokyo

PLATE NO. 13

Surrender Day for the Japanese, 2 September 1945

[37]

The next day witnessed an event unique in Japanese political history. While troops continued to unload in Tokyo Bay, an emergency session of the Diet was called to hear the Emperor's address and Prime Minister Prince Naruhiko Higashi-Kuni's explanation of the developments which led to the Imperial decision to surrender. The Emperor's opening address to the Diet was significant. It was the first time he gave direct orders to his subjects. The address was lucid and free of ambiguous terms. Previously, the Imperial rescript had merely stated acceptance of the Potsdam declaration. The people knew only that the instrument of surrender had been signed by representatives of the Emperor. Now the Emperor told them in person that, in his desire to improve Japan's difficult position, he had ordered capitulation. Thus, even in defeat, the unique traditional relationship of the "Emperor-head of the Japanese Nation-family" had been preserved. Peaceable fulfillment of Allied demands could mean continuation of this relationship. At the same time, it was hinted that this privilege might be lost if the Allied demands were not peaceably fulfilled. The Emperor ordered the people to abide by the terms of surrender and to work toward regaining the trust and faith of the world. He stressed the need for coolness, self-discipline, and assistance to soldier's families and others who suffered as a result of the war. To the Japanese this was a clear directive to work in peace, an indication that a new chapter in the life of the nation was beginning. It is interesting to note that although the term "surrender" was not used in the Imperial address, it occurred frequently in the local press.33

While the Emperor was addressing the Japanese people, Lt. Gen. Charles P. Hall's XI Corps Headquarters finished unloading and opened in Yokohama. The 8th Cavalry Regiment (1st Cavalry Division) passed to control of the Commanding General, XI Corps, and relieved the 11th Airborne Division of guard duty on the perimeter along the inner Yokohama Canal and at vital installations in Yokohama proper.34 The 12th Cavalry Regiment moved to the Tachikawa area, west of Tokyo, and occupied Chofu, Yokota, Showa, and Tachikawa airfields, completing United States control of all important airfields on the Kanto Plain.35 Meanwhile, elements of the 11th Airborne continued to arrive at Atsugi despite unfavorable weather. Service troops of the Far East Air Forces and the first battalion of the 127th Infantry (32d Division) landed at the Kanoya airdrome on 4 September. They occupied the area south of Tokyo.36 On 5 September, reconnaissance parties from the XI Corps and 1st Cavalry Division penetrated Tokyo in preparation for the main movement of troops planned for 8 September. The 1st Cavalry Division thus claimed to be the first unit in Tokyo.

The weather continued to be unfavorable and the remaining elements of the 11th Airborne on Okinawa were forced to postpone departure for Atsugi until the following day. On 6 September the 11th Airborne closed at Okinawa. No casualties had been reported in the movement of the 11th Airborne between Okinawa and Atsugi, but fifty-nine men had been killed and nine seriously injured in crashes

[38]

between Luzon and Okinawa.37 Troop carrier planes began moving elements of the 27th Division.38 By evening of 7 September the air movement of the 27th Division from Okinawa to Atsugi had assumed sizeable proportions. Approximately 25 percent of the strength of the 105th Infantry Regiment had arrived. The forward command post of the Division closed at Okinawa and opened at Hiratsuka.

The initial landing at Atsugi was the first occupation of Japanese soil by American troops. However, the event which was to symbolize the real defeat of Japan was the entry of the Supreme Commander and his forces into Tokyo, the final step on a long trail.

At 0800 on 8 September a motor convoy left the assembly area of 1st Cavalry Division at Hara-Machida and turned toward Tokyo. Among other vehicles was a jeep which carried General Chase, the Division Commander. Unfortunately for all those of the Division who had so thoroughly earned the right to be "first" in Tokyo, the bulk of the Division was carrying out occupation duties and not many units could be spared for the mission. Only the band, the second squadron of the 7th Cavalry Regiment, the 302d Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop, and one veteran representing each of the other non-participating troops were included for the formal entry.

North and east the convoy sped. The cavalrymen moved through pine-covered hills, pock-marked with caves dug by the Japanese. They passed through Hachioji, almost obliterated by United States air attacks. Only scattered corrugated metal shacks, some steel and concrete safes and vaults, a few tall stacks, and forlorn, fire-blackened ruins remained of what had been a thriving industrial city of 60,000 people. Along the Chofu Highway Japanese children waved, shouted, bowed or saluted. It was difficult to believe that this occasion emblematized conquest. The convoy seemed more like a triumphant parade of troops returning home to receive the victor's plaudits.39

The cavalcade halted at the city limits. General Chase alighted from his jeep and stepped across the line. As soon as he was seated again in his jeep, the convoy resumed its movement. The U.S. Army was in Tokyo.40

A few hours later, at a simple ceremony in front of the American Embassy, General MacArthur gave the following order to General Eichelberger: "Have our country's flag unfurled and in the Tokyo sun let it wave in its full glory, as a symbol of hope for the oppressed and as a harbinger of victory for the right."41 The guard of honor presented arms and the officers saluted, as the Stars and Stripes waved over Tokyo, Japan's capital city-humbled, charred, and flattened in defeat.

The Commanding General, XI Corps became responsible for the city of Tokyo, a task delayed for several days to allow the Japanese to disarm the troops within the capital. During the day, the 2d Cavalry Brigade Headquarters and the 7th Cavalry Regiment moved to Tokyo, establishing their bivouac area on the Yoyogi Parade Ground adjacent to the Meiji Inner Shrine. Elements of the 132d Infantry of the Americal Division had arrived at Yokohama,

[39]

General MacArthur with Maj. Gen. Wm. C. Chase, followed by Admiral Wm. F. Halsey

and Lt. Gen. R. L. Eichelberger enter the American Embassy grounds, Tokyo, for the

official raising of the American flag.

Salute to the flag in the American Embassy grounds.

PLATE NO. 14

Tokyo-The End of the Road, 8 September 1945

[40]

and were en route to their assembly area two miles southwest of Hara-Machida.42

The 187th Para-glider Infantry of the 11th Airborne Division continued to guard Atsugi airfield and vicinity and relieved elements of the 1st Cavalry Division at Hara-Machida Military Academy and Ordnance School. During the course of guard duty around the field an incident occurred which was initially thought to be the first clash with Japanese civilians. Approximately 100 men attempted to loot warehouses at the northeast corner of the airfield. Troops of the 187th broke up the attempt and arrested three persons. Another resisted arrest and was killed. An immediate investigation revealed that the offenders were not Japanese but Koreans.43

The Occupation Firmly Established

With the United States troops in Tokyo, the Occupation became an accepted fact to the Japanese people. There were no hostile or subversive moments, only a curious interest on the part of all classes of Japanese as new units moved through the streets of Yokohama and Tokyo. The Japanese press in general maintained an attitude which was almost that of a host.

With the exception of the 8th and 12th Cavalry RCT's, on security duty in the Yokohama-Tachikawa area, remaining units of the 1st Cavalry moved from Hara-Machida into Tokyo on 9 September.

The Americal Division continued its debarkation during 9 and to September and established its command post northwest of Hara-Machida. Nearly all of the division artillery was established in the Yokohama area, while more than 60 percent of the 164th Infantry was billeted in the vicinity of Tachikawa.

Good weather had favored large-scale air movements from Okinawa and seventy-four planes arrived at Atsugi carrying personnel and equipment of the 27th Division. The regimental headquarters of the 105th Infantry had been established at Odawara and rail transportation had been marshalled for the movement of the incoming troops on 10 September.44 On the same day Task Force 35, bearing Eighth Army representatives, entered Katsuyama Bay on the Uraga Peninsula east of Tokyo, and a landing was made at Katsuura. Considerable army and navy equipment was found in good condition and no incidents were reported.

By to September primary security duties were taken over by the Americal Division which, with the exception of a battalion of the 164th Infantry, had completed unloading and moving from the docks. Elements of the Division relieved 1st Cavalry units on duty in Tachikawa and Chofu airfield areas and in the Yokohama area. At Hara-Machida the 182d Infantry of the Americal Division replaced elements of the 11th Airborne which was to be transferred to Sendai. Soon thereafter the advance party of the 11th Airborne departed for Sendai. The air movement of the 27th Division from Okinawa went on without interruption during the day, while the 105th Infantry, which had arrived earlier, moved by rail from Atsugi to Odawara. Meanwhile the 106th opened a temporary command post at Zama.

At the initiation of G-2, SCAP directed that the Imperial General Headquarters should be

[41]

dissolved not later than 13 September.45 It had served its immediate purpose. The pattern of the Occupation in the Initial Evacuation Area, as outlined in the original surrender documents, was assuming definite shape. The Eighth Army, charged with execution of General Order Number 2, was ready to expand its area of operations. Radiation movements of several subordinate units were carried out:46 (1) XIV Corps landed at Sendai on 15 September and opened its headquarters on the 18th; (2) 11th Airborne and 27th Divisions transferred control of and responsibility for their current assigned areas to XI Corps; (3) 11th Airborne Division began rail and motor movement to Sendai on 14 September, occupied Miyagi Prefecture and opened its command post on 1 October at Sendai; (4) control of both divisions passed to XIV Corps; (5) farther north, the 81st Division, IX Corps, landed in the Aomori area on 27 September; (6) elements of the 77th Division landed on 15 October at Otaru and secured the city with its port facilities, occupied Sapporo, and as troops became available, extended control throughout the island of Hokkaido.47

In the same order were included a number of other instructions generally in keeping with the prudent policy of avoiding friction. Among them were discreet reminders to commanders that the moves were still operational in character. It directed that all units be continuously in a state of combat readiness. Each commander charged with initial occupation of an area was directed to dispatch a reconnaissance party at least forty-eight hours in advance for verification of Japanese compliance with existing directives. No subordinate commander was allowed to issue directives to the Japanese military authorities. He submitted his request to Eighth Army Headquarters for specific instructions, which were then sent from that headquarters to the Japanese. Considerable attention was given to dress, conduct, discipline, and military courtesy of the troops. All commanders were ordered to take positive steps to protect shrines, objects of art, historic and religious monuments; Imperial residences and buildings; and all embassies, consulates, and buildings belonging to any of the United Nations.48

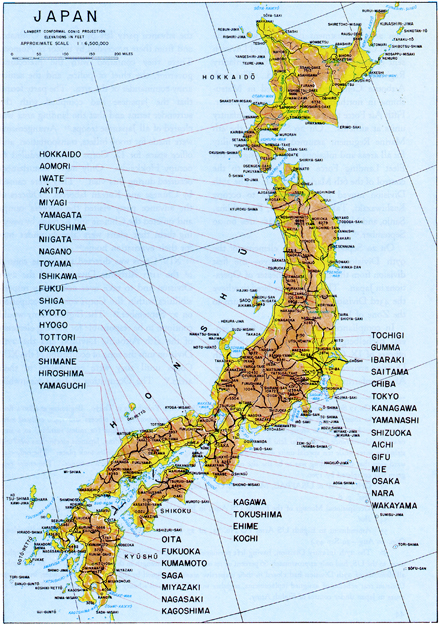

Nearly all of the 1st Cavalry Division was established in Tokyo by 13 September. On 14 September, the final plane load of 27th Division troops arrived at Atsugi. Elements of the 43rd Infantry Division moved to Kumagaya, northwest of Tokyo. The Eighth Army's area of responsibility was extended by CINCAFPAC to include the entire prefecture of Nagano. Patrols by the newly-arrived 27th Division were operating in the Hadano area. The same day, elements of Headquarters XIV Corps began unloading in the Sendai area. XI Corps was informed by Eighth Army that its area of responsibility would include the prefectures of Chiba, Ibaraki, Tochigi, Saitama, Tokyo, Gumma, Nagano, Yamanashi, and 'Kanagawa (excluding the Yokosuka Naval Base).49 (Plate No. 15)

During the period 17-20 September, expan-

[42]

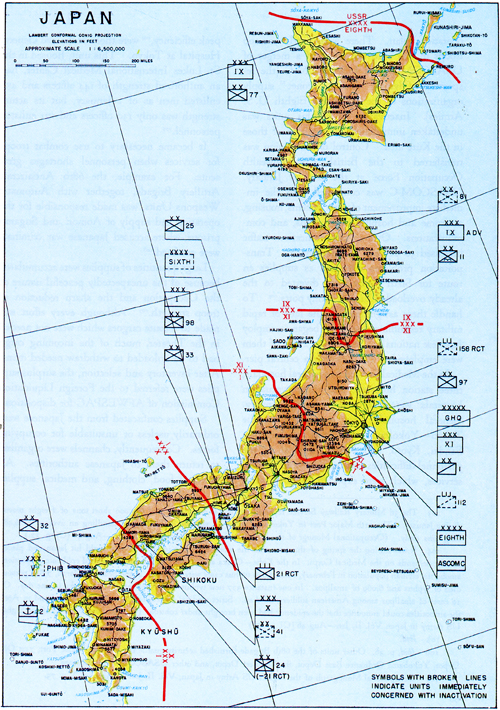

PLATE NO. 15

Prefectures of Japan: The Principal Political Subdivisions

[43]

sion and readjustment continued within the Initial Occupation Area.50 The 43rd Division sent elements in to relieve the 164th Infantry Regiment at Irumagawa airfield. The 11th Airborne Command Post opened in Matsushima in northern Honshu on 17 September. Fifth Air Force troops began to relieve infantry units at airfields. On 20 September the 4th Marine Regiment assumed the responsibility for all areas and missions formerly assigned the Fleet Landing Force which reverted to the control of the 6th Marine Division. The 27th Division moved from Muratsuka to occupy Kashiwazaki, Takada, Korizama, Fuchishima, Sanjo, and Nagaoka in the Niigata area on 20 September.51

On 20 September advance elements of the 97th Division arrived in Tokyo-the first division from the European Theater of Operations in Japan. The 97th was ordered to relieve the 43rd Division which prepared to return to the Zone of Interior.52

In compliance with instructions from General Eichelberger, an advance party of staff officers of IX Corps, 81st Division, and 77th Division arrived in Yokohama on 2 September. After conferring with the Eighth Army staff, the advance party left by plane for Ominato, and from there proceeded by motor to Aomori. There they conferred with the prefectural governor, the chief of police, and the senior army commander of the area. The party found that the Japanese had complied with the surrender terms and that the landing area was cleared of all Japanese troops.53 Arrangements were made for troop billets, transportation, and office space for IX Corps units scheduled to occupy Hokkaido. Only minor disturbances occurred during this visit. They were caused by Chinese and Korean laborers. Officers of the advance party visited the laborers' camps and quieted the Chinese and Koreans by assuring them that plans were already under way for their evacuation home.54

XIV Corps was directed to assume control of the 11th Airborne Division and the 27th Division and to take over occupation responsibilities within the Corps zone of occupation on 27 September.55 The Eighth Army would continue to be responsible for moving elements of the 11th Airborne Division and the 27th Division into the zone of occupation of the XIV Corps until they were established in their areas.56 The Occupation of Japan meanwhile

[44]

had proceeded so well that shipments of all combat elements of Corps troops (except combat engineers) were cancelled.

Before the end of September, IX Corps units landed in force in northern Honshu.57 81st Division troops landed on 25 September and established Division headquarters in Aomori. Regimental command posts were located as follows: the 321st Infantry at Tsuchiya, the 322d Infantry at Hirosaki, and the 323d Infantry at Hachinohe. (Plate No. 16)

With the exception of the 158th Regimental Combat Team, which was scheduled to occupy Utsunomiya (northwest of Tokyo) in October, Eighth Army's occupation of Honshu was virtually completed by the end of September. The main and supporting movements had taken place with smoothness and dispatch, something that had not been anticipated. Not one serious incident marked the movement of thousands of Eighth Army troops into Honshu. All areas were under firm control. Units of the IX, XI, and XIV Corps carried out their missions without trouble. They operated routine security patrols, seized and secured critical Japanese installations and made local checks on the demobilization of the Japanese armed forces. The progressive destruction of enemy ammunition and materiel was also supervised. In a surprise move at the end of the month, troops and CIC units established guards over all Japanese financial institutions and strong rooms. The banks were closed, pending a detailed inspection by SCAP technical experts.58 In the midst of these activities the 43rd Division, the first to be returned to the Zone of interior, sailed from Yokohama on 28 September.

Sixth Army Occupation Movements

Because the initial occupation under Eighth Army had gone so smoothly, it was possible to accelerate Sixth Army occupation assignments. Originally it was planned for Sixth Army moves to be initiated only after the Eighth Army had completed its assignments under "Blacklist," and the desire of Japan to accept the surrender terms had been established beyond all doubt. Although no sizeable Sixth Army landings were planned until October, main preliminary moves began on 25 September.59

General Krueger's area of responsibility was divided into three zones. I Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Innis P. Swift, was to occupy the Osaka-Kyoto-Kobe zone. This zone included thirteen prefectures and extended south from the Eighth Army boundary to a point between Kobe and Okayama. The central zone of the Sixth Army area was adjacent to the I Corps zone and comprised the remainder of southern Honshu (except the Shimonoseki tip) and the island of Shikoku. Maj. Gen. Franklin C. Sibert's X Corps was given responsibility for this area, which became the second zone. The third zone, which included the Shimonoseki tip of Honshu and the island of Kyushu,

[45]

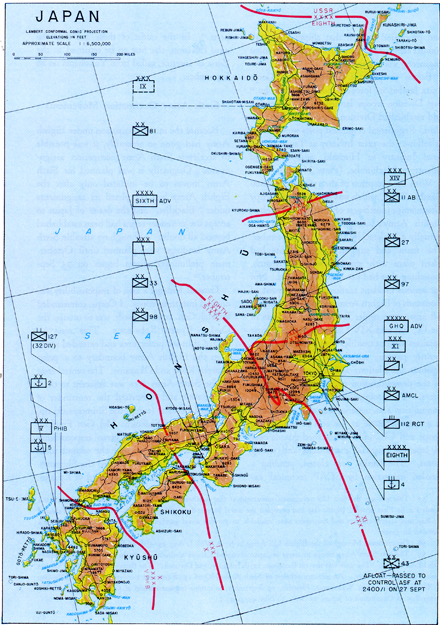

PLATE NO. 16

Location of Major Ground Units, 30 September 1945

[46]

was assigned to the V Amphibious Corps commanded by Maj. Gen. Harry Schmidt, USMC.

The leading elements of the 5th Marine Division landed at Sasebo (Kyushu) on 22 September, and on the following day the 2d Marine Division went ashore at Nagasaki. After these key objectives had been occupied, the 2d Marine Division expanded south of Nagasaki to assume control of the Nagasaki, Kumamoto, Miyazaki, and Kagoshima prefectures. In the meantime the 5th Marine Division expanded east to the prefectures of Saga, Fukuoka, Oita, and Yamaguchi.60

Headquarters Sixth Army landed at Wakayama on 25 September and opened at Kyoto two days later. Two of the three divisions of I Corps, the 33d and the 98th, arrived on 25 and 27 September respectively.61 The 32d Infantry Division was not scheduled to move from the Philippines to Japan until October.

There was every indication by the beginning of October that the Occupation was proceeding satisfactorily. Although there was good co-operation on the part of both the Japanese population and the officials of the government,62 it was necessary to move Sixth Army troops into their zones of responsibility in order to make the Occupation complete. In view of complete Japanese cooperation, modifications of the original "Blacklist" plan were possible in expediting the Occupation. Paragraphs of that order regarding possible resistance were eliminated.63

When General Krueger (Sixth Army) assumed command of ground forces in the zones of responsibility of V Amphibious Corps and I Corps on 24 and 27 September respectively, he established his headquarters in Kyoto. I Corps was to control the Osaka-Kyoto-Kobe area; X Corps, the central portion of the Sixth Army Zone; and V Amphibious Corps, the extreme southern part.

All movements of Sixth Army units were of dual nature: occupation and adjustment for early inactivation of the veteran Sixth. After this was accomplished, transfer of low-point troops into Eighth Army and deployment of high-point troops to the Zone of Interior for discharge or reassignment would follow.64

Japanese Reaction to Initial Occupation

The Japanese reaction to the initial occupation was so favorable that the Supreme Commander issued an official statement in September in which he estimated the total occupation force could be cut to 200,000 men by 1 July 194665 This seemed unbelievable and some

[47]

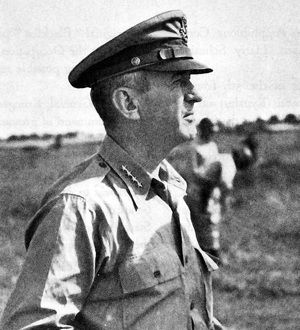

Gen. Walter Krueger as he appeared in

the field in 1945

Gen. Walter Krueger arrives in Tokyo for

a visit with the Supreme Commander.

PLATE NO. 17

Sixth U.S. Army Commander

[48]

American magazines and newspapers were quite antagonistic, claiming that the statement had been made for effect only and was not in the best interests of safety. Nevertheless, the "man on the ground," the American soldier, was inclined to believe it.

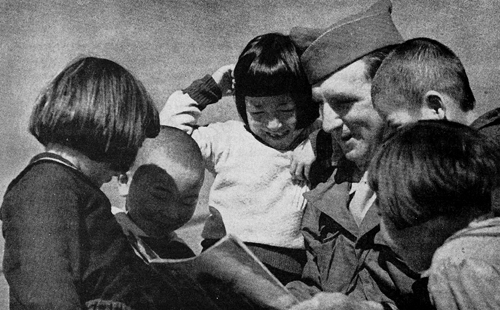

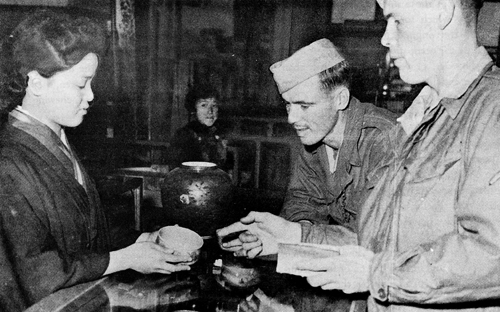

Calming a nervous populace called for discipline and friendliness. General MacArthur's troops proved themselves equal to the task. American personal kindness and official consideration were wholly unexpected by the Japanese. Those factors went far toward building good relations with an emotionally disturbed people. Beginning with the first hours of the Occupation, the old authoritarian background of the Japanese contrasted with the free, liberal philosophy of the American forces. Adjustments had to be made and sometimes led to misunderstanding and confusion.

Japan, accustomed to close control from the top and always indifferent to independent thinking from those in lower strata, had no criteria by which to initiate or to judge the value of the original measures so strongly desired by the occupation authorities. Adjustment, however, proved far less difficult than had been anticipated. This was partly due to the apparent eagerness of the Japanese to adapt themselves to occidental methods, although a great deal of credit must be given to the shrewd advance planning of General MacArthur.

Japanese ideas of how their conquerors would react once Japan was occupied were based on former Japanese Army policy in the conquered Asiatic and Pacific Ocean areas. In those areas the native populations, regardless of their own food shortage, were always expected to feed the Japanese troops. Mindful of their army's policy and in anticipation of food requisitions by the Occupation forces, the Kanagawa prefectural authorities laid in a store of onions, potatoes, fruit, and meat. Since all intelligence surveys had correctly reported an acute shortage of food in Japan, Occupation personnel expressed considerable surprise at this abundance. When a member of the reception committee explained that the food had been "requisitioned," one of the United States officers made it clear that no such special consideration was desired. This attitude, wholly at variance with Japanese Army practices abroad, produced an immediate, favorable effect upon Japanese public opinion. The Japanese were further impressed by early reports of tolerant treatment of the Japanese by our soldiers.

Two days after the surrender, twenty truck-loads of flour, rolled oats, canned goods, and rice arrived at the Yokosuka municipal office as relief supplies for the local people. The next day eleven more trucks appeared with medical supplies, blankets, tea, and other goods. Mayor Umezu, completely overwhelmed by this unexpected generosity, expressed his deep appreciation.66 Simultaneously, American soldiers on patrol or sightseeing in trucks and jeeps circulated throughout the occupied areas. Amused by the Japanese children, they handed out chocolate bars, hard tack, chewing gum, and candy drops.67

There were other humane actions, as in the case of three American soldiers who gave first aid to a girl knocked down and severely injured by a Japanese street car. The soldiers were further reported to have hailed a passing army vehicle and to have taken the injured girl to a hospital. This act was greatly appreciated by the Japanese.68

Units temporarily billeted in the Yokohama Museum and the Yokohama City Library created a very favorable impression. Just before

[49]

Shopping on the Ginza.

PLATE NO. 18

GI: Ambassador of Goodwill

[50]

leaving, they carefully cleaned the rooms, gathered up all the trash, and buried waste and refuse in a neighboring lot.69

The friendly boyishness of the new arrivals who, when strolling along the Ginza for the first time, polled the numerous street stall eating places to ask for milk70 amused the Japanese and eased the tension. These minor incidents exemplify what appealed to the "face saving" tradition-bound nature of the Japanese people.

To forestall any incidents which might be caused by exuberant, irresponsible soldiers seeking souvenirs, all commanding officers were instructed to take necessary precautions. Considering the fact that the majority of occupation troops were combat veterans, relatively few incidents marred the initial occupation. The Japanese received the victors submissively following the Emperor's mandate. They had accepted the Americans cautiously and were eventually impressed by the complete absence of systematic looting and violence which many had fully expected. The one factor which had an immediately noticeable effect on the people of Japan was the spontaneous generosity of the Americans.

There was no lack of a realistic attitude on the part of the Occupation authorities. This was an occupation of enemy country, and fanatics were known to exist and circulate. For this reason, ten check points, manned jointly by Japanese policemen and Eighth Army troops, were established around the initial occupation zone. The police, stationed outside the zone, stopped all passers-by to make sure that no armed individuals penetrated. The troops remained for the most part within their area and arrested those who acted suspiciously. Cooperation between the Occupation forces and Japanese civil police was thus early established.71

The Japanese press, which at first had been inclined to be dubious about American behavior, now voiced unanimous praise.72 Japanese authorities, in striving faithfully to avoid unpleasant incidents which might lead to violence, urged their people to act prudently, decorously, and with composure, "thereby displaying the true essence of the Yamato race."73

This took several forms. Initially, the Japanese publicists and officials recommended passive acceptance of Occupation authority, and avoidance "as far as possible" of all but the most essential business relations with Americans. This, it was pointed out, was not due to hostility between the two peoples but to the unavoidable fact that customs differences and language barriers posed almost insuperable obstacles to normal social relations.74 As a further means of lessening conflict they began to intensify efforts to widen the use of English. This was not an easy task. English had been frowned upon during the war, school courses in the language had been discontinued, and in many places casual use of English had been regarded as a sign of disloyalty. Nevertheless, as soon as surrender was proclaimed, efforts

[51]

were made in every town and village to revive the study of the language.75 Specifically, the police advised the Japanese to stop worrying, to disregard rumors, and to report to the police all problems arising between Japanese and foreigners.76 Newspapers, using a well worn Japanese method, warned that the eyes of the world were upon Japan and that calmness was to be maintained.77 One newspaper, blandly assuming that "...coquetry is the cause of trouble..." warned women against the use of heavy lipstick, rouge and eyebrow pencil. It also urged Japanese to be cautious of the type of English used on the streets. "Do not loiter in the streets nor follow the troops, and do not try to purchase anything from soldiers...." was probably its most significant advice.78 Yomiuri and Tokyo Shimbun were the most consistent of all Japanese newspapers in warning Japanese women against improper costumes or behavior.79 After cautioning girls against walking unattended even in the daytime, Yomiuri added: "Even when called upon by foreign soldiers saying 'hello' or 'hey', inter-mingled with their broken Japanese, women will pay no attention and will avoid all contact with them."80 The press and the people alike were soon to learn that even in the few instances when women were molested, the offenders were punished.

Washington suggested that restrictions should be placed upon associations of Occupation personnel with the Japanese population only in the event that the Occupation authorities considered such restrictions necessary.81 General MacArthur, who had lived in the Orient. for many years, was reluctant to make an issue of a delicate problem. The subject was therefore handled with tolerance, restraint, and discretion.

Recognizing early that restoration of good relations depended largely upon the correctness of Japanese behavior, and that this in turn called for proper understanding of American psychology, Japanese newspapers stressed the need for promoting good relations. Lack of information concerning American ideals and methods was cited as a chief obstacle in promoting mutual confidence.82 Although this was a complete reversal of form according to their former pronouncements, it was not too surprising. The Japanese psychology was quite pliable where their country's future was concerned.

The Japanese eagerly sought contacts with American soldiers. They made strenuous efforts to facilitate proper social relations. Tokyo municipal police prepared a chart of entertainment places and distributed it to all policemen, officials, and others who might be asked to direct Occupation troops to such resorts. Various associations worked out elaborate plans for restaurants, recreation centers, theaters, dance halls, and other entertainment facilities. Rather than depend on Japanese recreation plans (some of which were not approved by Occupation authorities), clubs and snack bars were provided by the American Red Cross and Army Special Services. Special Services also took over numerous hotels, theaters, parks, golf

[52]

clubs, and other facilities, providing a variety of supervised recreation for Occupation personnel.

By the end of September, Japan's defeat had become a reality to her people. For the first time in her long history Japan had become a nation completely dominated by a foreign power. The firm hand of General MacArthur was controlling and guiding the Japanese nation and the people seemed responsive and cooperative. The large task of demilitarization of factories and resources had begun. War criminals were being arrested and held for trial. Ammunition, weapons, and other military material were being moved to depots to be inventoried and eventually destroyed. All these things the Japanese people had initially accepted, and continued to accept submissively, if not favorably.

Eighth Army Occupation is Completed

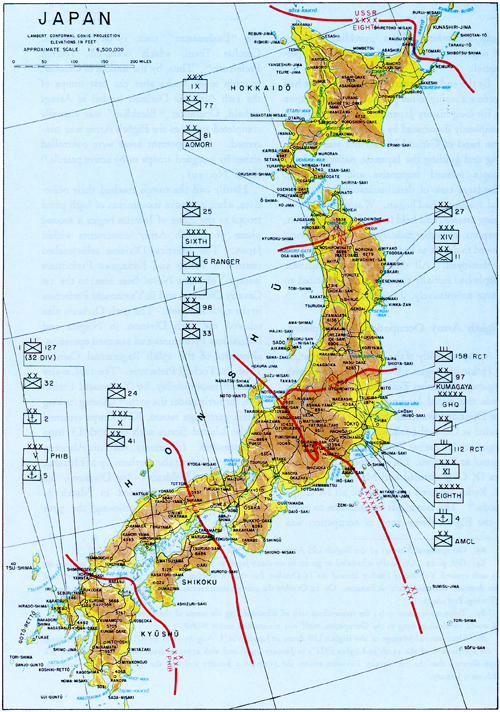

A responsibility of the IX Corps, occupation of Hokkaido began 4 October when the 306th Regimental Combat Team of the 77th Division made the initial landing. The remainder of the Division proceeded by water convoy and landed at Otaru the following day. The 307th Regimental Combat Team immediately took control at Sapporo. On 7 October, Headquarters IX Corps landed and Maj. Gem Charles W. Ryder assumed command of all IX Corps troops.83 The last major organization to move in the Eighth Army zone of occupation was the "Bushmaster" unit, 158th Regimental Combat Team, which occupied Tochigi Prefecture.84 Thus, by the middle of October, roughly seven weeks after the first troops of the 11th Airborne Division landed at Atsugi airfield, Operation "Blacklist" was virtually completed as far as the Eighth Army was concerned. All important areas were controlled either by assigned troops or by active patrols.85 (Plate No. 19)

Hardly had the troops reached their objectives, when extensive movements of high point troops to the Zone of Interior began a second phase of Eighth Army movements within Japan. The Americal Division relinquished control in Tokyo and Kanagawa Prefectures (except Yokosuka Naval Base area) to the 1st Cavalry Division, and in Yamanashi Prefecture to the 97th Division. The 97th Division also relieved the 27th Division in Niigata and Fukushima Prefectures and assumed operational control of the 158th Regimental Combat Team in Tochigi Prefecture. The 1st Cavalry assumed responsibility for Yamanashi Prefecture, formerly under the 97th.86 Closing its long Pacific campaign record, XIV Corps returned to the United States with the 27th Division in December. In January, the 11th Airborne Division took over the northern tip of Honshu, relieving the "Wildcats" (81st Division). Its control was further extended in March to include Hokkaido, thus relieving the 77th Division.

[53]

PLATE NO. 19

Location of Major Ground Units, 31 October 1945

[54]

Communications, Procurement and Requisition

The initial work of Signal Corps units required not only installation and maintenance of communications over the island of Honshu as the number of Occupation troops increased weekly, but also necessitated survey and overhaul of worn Japanese equipment to determine ways and means of blending this into a swiftly growing communications network. Bombings of Japan had caused destruction of about 25 percent of all wire communications. An additional 25 percent had reached a low state of efficiency through overloading and poor maintenance. In Tokyo only 50,000 of the original 200,000 instruments were in service. In all of Japan it was estimated that approximately half of all the instruments in use at the beginning of the war were buried in the debris.87

There was no difficulty in procuring billets and office space during the initial occupation. The 11th Airborne Division took over barracks vacated by Japanese soldiers. For several days, the paratroopers and the 1st Cavalry men moved from one installation to another in their respective assigned sectors and occupied whatever space was available. But with the arrival of additional troops and the heavier concentration of forces in the half-gutted Tokyo-Yokohama area, the problem became acute.

There arose an immediate need for an orderly, supervised system which could provide billeting space and bivouac areas with the least possible delay. The problem had been anticipated, however, and the advance party which landed at Atsugi on 28 August carried instructions from General Headquarters for the establishment of the Eighth Army Area and Facilities Allocation Board. On 2 September an advance party of seven officers organized the Board in Yokohama in order to coordinate demands on the Japanese for procurement of facilities. This original small section was greatly enlarged when most of the personnel of the Eighth Army Field Artillery Section, headed by Brig. Gen. Eugene McGinley, were placed on temporary duty with the Allocation Board. Its maximum strength was forty-five officers and twenty enlisted clerks.88

To handle efficiently the volume and variety of requests submitted, the Board was organized into four sections: Billeting and Housing, Area and Storage, Records, and Coordination and Planning. A fifth section was later added to assume control of the Tokyo area, excluding the part which General Headquarters had already acquired for its own use.89

Japanese officials played an important role in many phases of the Occupation and the work of the Allocation Board was no exception. The Yokohama Liaison Office, created to simplify and coordinate routine administrative

[55]

matters, was a subordinate echelon of the Japanese Facilities Agency. The office operated in compliance with the provisions of an Eighth Army administrative order.90 The same order directed that all billeting space, barracks, camp areas, port facilities, transportation, and many other major installations would be allocated by the Board, based on requirements submitted by subordinate units.91

Beginning with a mere handful of men late in August, the Eighth Army moved three corps, seven combat divisions, and supporting service troops into Japan within less than a month. By October a total of 232,379 Eighth Army men were in the country.92 The Sixth Army in its zone of responsibility had an approximately equal number. However, this was the high water mark and already the tide was turning the other way. It was apparent to careful observers that the capitulation of Japan was as comprehensive as it was real. Consequently, General MacArthur's mid-September estimate that an army of 200,000 would be adequate to garrison the islands was now widely acclaimed.

General MacArthur was impatient with critics who mistook the Occupation policy of allowing the Japanese considerable freedom in rebuilding the country economically and politically as a sign of softness. In a significant press release dated 14 September he stated:93

I have noticed some impatience in the press based upon the assumption of a so-called soft policy in Japan. This can only arise from an erroneous concept of what is occurring.

The first phase of the occupation must of necessity be based upon military considerations which involve the deployment forward of our troops and the disarming and demobilization of the enemy. This is coupled with the paramount consideration of withdrawing our former prisoners of war and war internees from the internment camps and evacuating them to their homes. Safety and security require that these steps shall proceed with precision and completeness lest calamity may be precipitated. The military phase is proceeding in an entirely satisfactory way. Over half of the enemy's force in Japan proper is now demobilized and the entire program will be practically complete by the middle of October. During this interval of time safety and complete security must be assured.

When the first phase is completed the other phases as provided in the surrender terms will infallibly follow. No one need have any doubt about the prompt, complete and entire fulfillment of the terms of surrender. The process, however, takes time. It is well understandable in the face of atrocities committed by the enemy that there should be impatience. This natural impulse, however, should be tempered by the fact that security and military expediency will require an exercise of some restraint. The surrender terms

[56]

are not soft and they will not be applied in kid-gloved fashion.

Economically and industrially, as well as militarily, Japan is completely exhausted and depleted. She is in a condition of utter collapse, her governmental structure is controlled completely by the occupation forces and is operating only to the extent necessary to insure such an orderly and controlled procedure as will prevent social chaos, disease and starvation.

The over-all objectives for Japan have been clearly outlined in the surrender terms and will be accomplished in an orderly, concise and comprehensive way without delays beyond those imposed by the magnitude of the physical problems involved.

It is extremely difficult for me at times to exercise that degree of patience which is unquestionably demanded if the long-time policies which have been decreed are to be successfully accomplished without repercussions which would be detrimental to the well-being of the world but I am restraining myself to the best of my ability and am generally satisfied with the progress being made.

The inconsistencies of armchair strategists, clamoring for repressive measures while weakening U. S. troops through accelerated demobilization became obvious in all theaters. Fortunately, General MacArthur's accurate psychological appraisal of the Japanese system enabled him to handle a contradictory situation. It was possible to utilize the Japanese government structure to the extent necessary to prevent complete social disintegration, insure internal distribution, maintain labor, and prevent calamitous diseases or wholesale starvation. With the Occupation well under way it was General MacArthur's opinion that the purposes of the surrender terms could be accomplished with only a small fraction of the men, time, and money originally projected.

Following the newly adopted Congressional policy of greatly reducing the armed forces, plans were developed for deactivation and redeployment. The result was that by the end of the year, General Eichelberger's command (Eighth Army) was under 200,00094 and was still going down. Meanwhile, the Occupation continued at an undiminished pace, quietly and efficiently.

The first four months of the Occupation were also a period in which great changes were brought about in the social, political, and economic life of Japan.95 Beginning with the famous "Bill of Rights" directive in the second month of the Occupation, SCAP had issued a steady stream of orders to the Japanese Government designed to destroy those influences in Japan which had led her into war, and to establish a democratic form of government. Political prisoners were liberated; the secret police force was dissolved; Shinto religion was separated from the state; the Emperor renounced his divinity; women's suffrage was promulgated; the educational system was revised; trade unions were legalized; and scores of other political and social reforms were launched. All of this required supervision and surveillance on the part of military occupation personnel.

The Beginning of the Second Phase

With the opening of 1946, a new phase in the Occupation of Japan began. Activities during the first months, from the landing at Atsugi in August to the end of the year 1945, consisted primarily of movements to occupy Japan and the deployment of large numbers of combat troops prepared equally to fight or favor, the recovery of Allied prisoners and

[57]

internees, the establishment of Occupation facilities, and the disarming and demobilizing of the Japanese armed forces.

From a military standpoint, the new phase would be concerned primarily with the maintenance of immediate objectives and the enter-ing upon long-range objectives of the Occupation. Both would be accomplished with a greatly reduced and constantly adjusting military force, yet one capable of meeting all emergencies, even combat, if necessary.

Among internal military problems confronting the Occupation, one of the most important was redeployment and deactivation of troops. Sixth Army was relieved of occupation duties on 31 December 1945, and General Eichelberger assumed command of all occupation army troops.96 At that time his Eighth Army consisted of five corps, eleven divisions, a number of lesser tactical units, and hundreds of service organizations. (Plate No. 20) The total strength was 18,123 officers and 223,383 enlisted men.97 This seemed to guarantee Eighth Army a personnel pool adequate to cope with its assigned mission, but by this time the United States' demobilization program had developed the tremendous momentum which reached its peak in January 1946. Actually there was more shipping available to the Zone of Interior than there were soldiers to fill it. Consequently, the point system, which had already undergone revision downward, was again modified.98 Following this change of the point system, Eighth Army lost 48,830 commissioned and enlisted personnel in January. The 1,385 replacements received hardly offset this loss, and the Eighth Army strength dropped sharply to 194,061 by the end of January.99

The 11th Replacement Depot at Okazaki and the 4th Replacement Depot at Zama shipped the soldiers home through the ports of Nagoya and Yokohama respectively. During January both depots reported the return of the "100,000th homeward-bound soldier."100

The Air Force strength in January was listed at 30,799.101 The Fifth Air Force with its base at Irumagawa was charged with the responsibility for air operations in Japan; the Fifth Fighter Command, based at Itazuki in Kyushu, covered southern Japan ; and the Fifth Bomber Command, also at Irumagawa, controlled northern Japan.

Service Unit and Supply Reorganization

During January the largest single unit operating under Sixth Army was USASCOM- C102 which was originally the service of supply for Eighth Army under the old "Coronet"

[58]

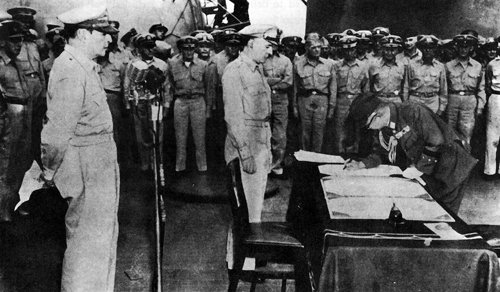

PLATE NO. 20

Location of Major Ground Units in Japan, 1 January 1946

[59]

operations plan. There were nearly 110,000 troops in this unit, the result of a merger of USASCOM-O and USASCOM-C (the respective "Olympic" and "Coronet" supply organizations of the Sixth and Eighth U. S. Armies). Inactivation of surplus units was undertaken immediately, particularly of those in the Kure area. Control of that region was transferred to the British Commonwealth Occupation Force at the end of January. USASCOM-C was concerned with the immediate improvement of water systems, housing, airdrome and hospital installations, and communications. Over-all communications traffic increased 30 percent in one month. Transportation problems increased as supplies en route for Sixth Army were diverted to the already overloaded Eighth Army ports.103 To handle these assignments in the face of rapid military reshuffling, the Army began to employ Japanese nationals. More than 2,800 of them were employed at the Yokohama central pier.

In the Medical Service, five general hospitals, three station hospitals, and three evacuation hospitals were inactivated during January. General hospitals were maintained in the Tokyo-Yokohama area and at Sapporo, Sendai, Kyoto, and Kobe. Typical of the personnel difficulties encountered by all medical services, which were expected to carry on at peak efficiency,104 were those of the 42d General Hospital at Tokyo. This unit, housed in the St. Lukes International Medical Center, had an authorized strength of 144 officers and 450 enlisted men as of 1 January, but its actual strength was only 130 officers and 171 enlisted personnel.105

It became necessary to use combat troops for services when personnel shortages grew acute. For example, the 68th Antiaircraft Artillery Brigade, together with Automatic Weapons Units, was made responsible for the operation and supply of Aomori and Sugamo prisons, where accused Japanese war criminals were confined.106

Large quantities of supplies were accumulated because of the unexpectedly peaceful nature of the Occupation and the sharp reduction of troop strength.107 Although every effort was made to re-route cargoes which were not needed in the Theater, much of the incoming cargo had to be unloaded to withdraw needed items. After inventory and selection, the surplus supplies were referred to the Foreign Liquidation Commission of AFWESPAC for disposition.

Supplies confiscated from the Japanese were ordinarily useless or unsuitable for occupying forces. Consequently, channels were organized to return them to Japanese authorities. All stores of food, clothing, and medical supplies

[60]

Lt. Gen. R. L. Eichelberger and Lt. Gen. H. C. H. Robertson, BCOF, inspect Kure dock area.

General Eichelberger inspects the Australian Guard of Honor at Kure,

British Commonwealth Occupation Force Headquarters.

PLATE NO. 21

The British Commonwealth Occupation Force, March 1946

[61]

were distributed as equitably as possible when and where they were most needed. As far as practicable, scrap from combat equipment was converted into domestic articles which reappeared on the Japanese market. Destructive munitions were dumped.108

Occupation troops were constantly uncovering caches of precious metals and gems, which either were of Japanese origin or were looted from invaded countries. On 14 January Eighth Army troops in Chiba Prefecture found sixty two tons of silver in one cache. In another instance the Civil Intelligence Section of G-2 recovered 46,000 carats of industrial diamonds seized mainly from the optical plants of occupied territories, particularly the Netherlands East Indies.109

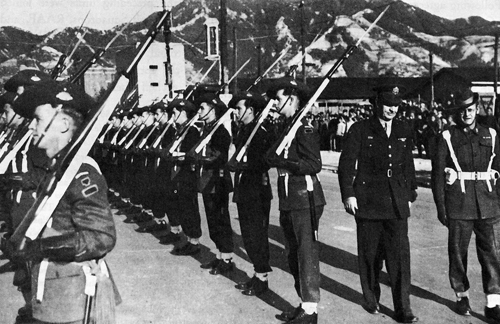

British Commonwealth Occupation

Force (BCOF)

Following agreements reached between British Commonwealth and United States Government representatives in Washington late in 1945110 and between Australian authorities and SCAP in December, the first elements of BCOF arrived in Japan by air 8 February. These were headquarters staff personnel. The following day a naval shore party arrived. It was not until 13 February, however, that the first sizeable unit came in. This was the 34th Australian Infantry Brigade, consisting of 1,200 troops, which landed and was established at Kure the same day. On 20 February Headquarters, BCOF, opened at Kure.111 Six days later Lt. Gen. J. Northcott, the Commander, arrived.112

Iwakuni airfield in Yamaguchi Prefecture was made Headquarters of the BCOF Air Group, which was under the operational control of the Fifth U.S. Air Force. Air Vice Marshal C.A. Bouchier opened the headquarters of the British Commonwealth Air Group there on 1 March 1946. The following week, the 81st Wing, Royal Australian Air Force, flew in from Borneo. Other air units included the 14th Squadron of the Royal New Zealand Air Force which arrived on 24 March. By 24 April the preceding units were joined by the 11th and 17th Squadrons, RAAF, and the 4th Squadron, Royal Indian Air Force.

BCOF ground forces continued to arrive throughout the spring and summer of 1946 until they reached their troop strength in

[62]

PLATE NO. 22

Location of Major Ground Units, 6 December 1946

[63]

August with a total of 36,154 officers and men.113 On 25 March the Occupation took on a distinctive international aspect when headquarters of the British and Indian Division, under Maj. Gen. D. Tennant Cowan, arrived at Hiro. On the same day the 5th British Infantry Brigade arrived, moving on the 24th of the month from Him to Kochi (Shikoku).

The military role of BCOF, under the direction of SCAP, included the following functions: the safeguarding of all Allied installations, and of all Japanese installations awaiting demilitarization; the demilitarization, disposal, and military control of Japanese installations and armaments.114 In March, BCOF progressively relieved I Corps troops in Shimane, Yamaguchi, Ehime, Kochi, Tokushima, Kagawa, Tottori, and Okayama Prefectures, and the island of Shikoku. The operation was completed by 10 June.

Liaison between GHQ, SCAP, and BCOF was maintained through the establishment in Tokyo of a headquarters known as British Commonwealth Sub-Area, Tokyo. This headquarters became responsible for the administration of all British subjects, military and civilian, stationed in the capital.

In order to assure the British Commonwealth Force greater participation in the Allied "show of strength," BCOF troops were ordered to Tokyo in April to share the responsibility of guarding the Imperial Palace and other honor assignments with troops of the 1st Cavalry Division. The first Commonwealth unit selected for Tokyo duty was the 34th Australian Infantry Brigade.115

The BCOF troops in Tokyo provided a colorful relief to the solid background of the numerous American forces engaged in general duties. With these relatively small, well-drilled units participating in many ceremonies, BCOF greatly impressed the Japanese. The frequent parades, including one "trooping of the colors" in front of the Imperial Palace by the 2d Battalion of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers, were among the most interesting and colorful functions of the Occupation. The daily change of guard at the palace was watched with interest by Japanese and Americans alike.116

The usual occupation duties were lightened somewhat for BCOF in its area of responsibility in October 1946 when the last of repatriation centers in that area was closed because only small numbers of repatriated Japanese arrived. BCOF, however, fell heir to a troublesome problem-the illegal entry of Koreans into Japan. Although the solution of such smuggling was placed in the hands of the Japanese Government by SCAP, complete supervision by BCOF was necessary in its area. There was need for close operational coordination-involving the use of air, land, and sea forces to properly patrol the coastal areas and apprehend violators. Cooperation between BCOF and I Corps was developed early and continued.117

[64]

Provost courts were established in the BCOF area in May for the purpose of handling all types of cases of United Nations nationals who were not connected with the military forces. BCOF reported "a remarkable lack of crimes against personnel of the Armed Forces."118

The Intelligence Corps of BCOF was made responsible for the disposition of enemy equipment. The one large disposal operation took place on Okuno Shima, where the principal Japanese chemical warfare arsenal had been functioning from 1925 to 1945. The elimination of dangerous chemicals and decontamination in this area, known as Operation "Lewisite," took over six months to complete. At the end of this hazardous operation, over 18,000 tons gross weight of war gasses and vesicants had been destroyed, and much valuable information had been collected on Japanese preparations for chemical warfare.

I Corps Realignments: With the introduction of BCOF troops into the Kure area, I Corps' area of responsibility was split-25th Division was located in central Honshu, north of the BCOF zone, while the 24th Division occupied the southern part of the island. By mid-year the shifts necessary to allow BCOF to assume its duties were completed. The 24th Division left Shikoku and Tottori Prefectures to relieve the 2d Marines on the west coast of Kyushu. By the end of August, this Division occupied all Kyushu. The 25th Division was replaced by BCOF in Okayama. By the end of August, 25th Division occupied all of the Kinki region, operating its patrols from headquarters at Osaka.119

The 2d Marine Division was to be relieved of occupation duties as rapidly as compensatory shifts could be made. After BCOF troops arrived, the area of responsibility for the Marines was gradually decreased through the indirect action of BCOF substituting for the 24th Division. For the latter, in turn, gradually began to relieve the 2d Marine Division.120 The 24th finally replaced the Marines on 15 June.121

Early in 1946, with the reduction of strength, troop lists were revised, and the number of units reduced. By mid-year, Eighth Army consisted of I Corps with the 24th and 25th Divisions, IX Corps with the 1st Cavalry and 11th Airborne Divisions, and the necessary service organizations and base commands. The deployment of major tactical units in zones of responsibility was stabilized by July 1946. No major, and only a few minor, changes in troop lists or locations of units occurred during the remaining months of 1946 or in 1947.122 (Plate No. 22)

By the end of 1946, most of the combat veterans had been returned to the Zone of Interior and had been replaced largely by draftees inducted near the end of the war or afterward. Many of them arrived in Japan with incomplete basic training; camps were built and special training programs were instituted. Units were so critically short of

[65]

personnel that much of this took the form of on-the-job training. Within ten months the bulk of these young draftees were replaced by Regular Army enlisted men, increasing the trend toward a more stabilized peacetime organization. From the military standpoint, local duties became routine. Except for guard duty and disaster relief work, the primary duties of a combat army disappeared.

The Occupation pattern had developed sufficiently to have its characteristics remain fairly constant after 1946. The decline in strength of military forces was contrasted by the rise in the number of civilian specialists and other employees sent in from the Zone of Interior or hired locally to carry on the Occupation. Although the administration of the Occupation was still in the hands of the military, its operation became increasingly a function of the Japanese civil sections operating under General MacArthur in his capacity as the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers.

[66]

Go to

Last updated 11 December 2006 |