CHAPTER V

DEMOBILIZATION AND DISARMAMENT OF

THE JAPANESE ARMED FORCES

The General Demobilization Program

There must be eliminated for all time the authority and influence of those who deceived and misled the people of Japan into embarking on world conquest, for we insist that a new order of peace, security and justice will be impossible until irresponsible militarism is driven from the world.... The Japanese military forces, after being completely disarmed, shall be permitted to return to their homes with the opportunity to lead peaceful productive lives.1

These principles enunciated in the Potsdam Declaration formed the basis for the elimination of military power and the initial plans for the demobilization of the Japanese armed forces incidental to occupation movements. Upon the return of the surrender delegation to Japan in August 1945, a complex demobilization machinery went into high gear: the rapid, orderly repatriation, demobilization and disarmament of the Japanese armed forces, at home and abroad, began immediately.

In view of the Theater G-2's detailed knowledge of the strength and dispositions of the Imperial Japanese Forces and the internal structure of the General Staff and other military organs after four years of intimate combat association, the intelligence section was given a prominent role in the surrender negotiations. In the agenda of the conference, the basic conditions were laid down for demobilizing and disarming the Imperial Forces. G-2 was directed to supervise the initial demobilization and disarmament plans of the Japanese Government, to exercise GHQ supervision of subsequent developments thereunder, and to render periodical progress reports.

On the day of surrender, the Imperial Japanese Forces totaled 6,983,000 troops, an aggregate of 154 army ground force divisions, 136 brigades,2 and some 20-odd major naval units.3 Army and Navy forces stationed within the home islands numbered 3,532,000; air force units were then integral parts of the Army and Navy. The balance of the Japanese forces were spread in a great arc from Manchuria to the Solomons, and across the islands of the Central and Southwest Pacific.4

Accurate and reliable figures on total strengths at the time of surrender were unavail-

[117]

able for some time. Original figures presented to General MacArthur's headquarters required continuous adjustment; and as repatriation progressed, it became apparent that hundreds of thousands of men, included in initial Japanese strength estimates, had perished prior to the conclusion of hostilities.

In the over-all picture, enormous military risks were involved in landing initially with "token" United States forces. The Japanese mainland was still potentially a colossal armed camp, and there was an obvious military gamble in landing with only two and a half divisions, then confronted by fifty-nine Japanese divisions, thirty-six brigades, and forty-five-odd regiments plus naval and air forces. The terrific psychological tension was dissolved by the relatively simple formula of preserving the existing Japanese Government, and utilizing its normal agencies to effect the complicated processes of disarmament and demobilization.

The program for the accomplishment of this tremendous task was initiated under the provisions of several key directives in August-September 1945.5 Immediate responsibility for demobilization was vested in the Imperial General Headquarters and the Japanese Army and Navy Ministries, in order that their technical and administrative skill could be exploited to the maximum degree. Supervising and planning this complicated operation required careful coordination on the part of the Occupation forces and ultimately involved practically all General Staff sections6 and several Japanese

[118]

agencies.

Certain civil sections were also drawn into this complex picture in connection with various phases of the demobilization operation. For example, the Public Health and Welfare Section of GHQ, SCAP, cooperating with G-3, was instrumental in developing effective repatriation quarantine policies, a step which prevented the dangerous epidemics so often associated with mass movements of people.7

To effect coordination and facilitate progress of the demobilization and disarmament program, each local Japanese commander was ordered to report to the senior U.S. Army commander in his area for command instructions; the Japanese staff was required to produce such information as locations of regiments and all larger units, tables of organization, actual strength figures, status of demobilization, and locations and names of commanders of demobilization depots. When this information was checked against the same information submitted by the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters8 some discrepancies were noted; for example, the Japanese failed to report twenty-three units of the tooth Air Brigade located at Takamatsu airfield on Yura Island (Shikoku District). However, through local surveillance by Occupation troops, complete demobilization was quickly carried out.9

Orders published by the Sixth and Eighth U. S. Armies implemented SCAP Directives Numbers 1 and 2. In essence they called for existing agencies (such as the Japanese military, naval, and civilian police, and the senior naval and military commanders) to disarm all personnel found with weapons. These agencies were also charged with expediting the transportation of Japanese military and naval personnel to their homes and directing the local authorities in the storing of surrendered arms and munitions and undertaking reconnaissance to insure that Occupation orders were being obeyed.10 Only the local Japanese police were permitted weapons considered necessary to maintain law and order.

In the initial Occupation phase, the infantry regiment became the chief instrument in the local supervision of demobilization. The entire plan for the imposition of surrender terms was based on the presence of infantry regiments in all Japanese prefectures. The outline of Occupation duties was fairly well established by SCAP and AFPAC instructions. The Sixth and Eighth Armies assigned prefectures to corps, divisions, and regiments. The specific number of prefectures assigned was determined by

[119]

population density, industries, and military installations. Usually regimental zones of responsibility comprised a single prefecture.

The Japanese had not waited for the Allied forces to appear before they started to disband their Army and Navy: in September-October 88 percent of the Army was demobilized. The Occupation troops soon found the bulk of their activities directed towards supervising disposition of war material. The demobilization program functioned smoothly and efficiently on its own momentum and reports to GHQ were monotonously uniform: "No disorders; no opposition; cooperation continues."

Japanese Plans for Demobilization

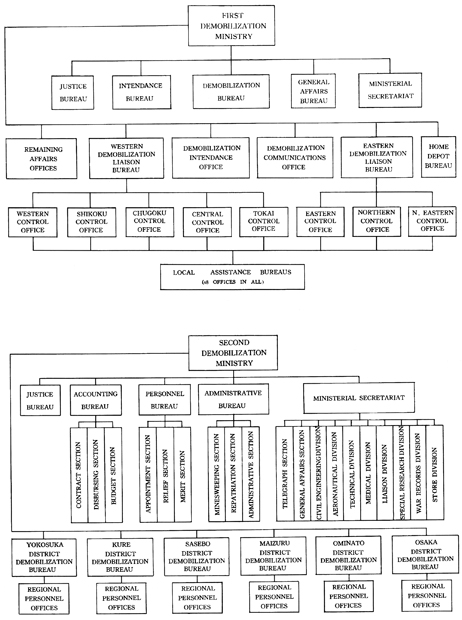

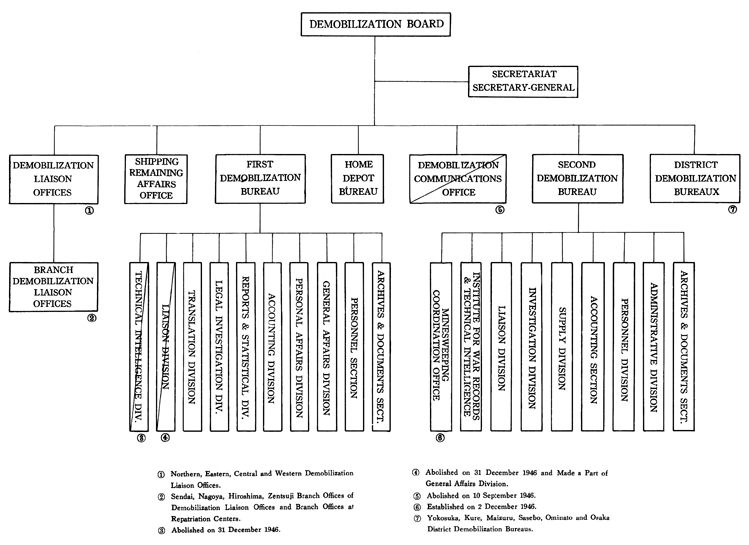

The over-all plan for the completion of the Japanese demobilization program, prepared by the Chiefs of the Military and Naval Affairs Bureau provided for the transformation of the existing Japanese Army and Navy Ministries into Ministries of Demobilization, on 1 December 1945. (Plate No. 36) The two Demobilization Ministries were to be staffed by civilians and organized much in the same way as the already existing Japanese civil ministries. As the demobilization program decreased in scope, the Demobilization Ministries were to be further changed into small bureaus, tentatively by 1 April 1946. It was estimated that the General Staffs of the Army and Navy and the Department of Military Training could be dissolved by mid-October; the only professional personnel to be retained were those necessary to carry on essential business, liaison, and information for the Occupation forces. The naval recommendations included estimated dates for complete repatriation of all Japanese then serving outside the Empire, minesweeping, and completion of administrative problems such as operation of hospitals, ports, and shipyards.

These plans, submitted mainly in chart form, were approved by SCAP on 10 October.11 There were certain inferential conditions: the dates listed in the plan would be regarded as absolute maximum, not to be exceeded; Japanese authorities would exert every effort to advance specific dates whenever possible.

Demobilization of the Japanese armed forces fell naturally into two major categories, the demobilization of the forces in the home islands and the forces overseas. The Japanese Navy Ministry (later the Second Demobilization Ministry) was given the mission of transporting all repatriates to Japan. Upon their arrival in the homeland they were channeled through either army demobilization or navy demobilization channels, depending upon their individual status. Demobilization of the overseas forces depended entirely upon chronology of repatriation to Japan.

Demobilization of the Japanese

Home Forces

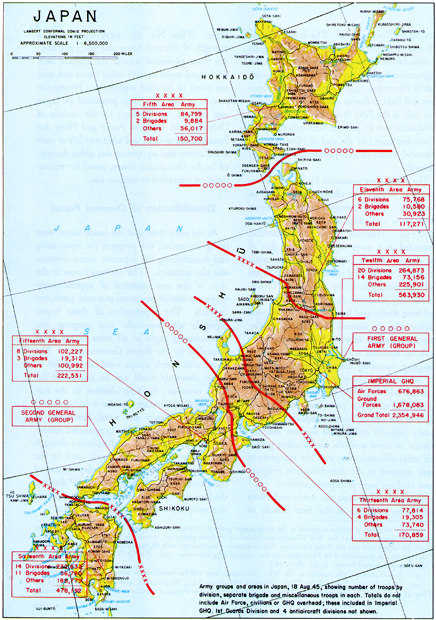

At the time of surrender, the command structure within the Empire was organized into two major branches, Army and Navy, both, however, under Imperial General Headquarters. The Army, which consisted of fifty-seven infantry divisions, two armored divisions, thirty-six brigades, the Emperor's personal guards, and the four anti-aircraft divisions was grouped into several major commands as follows: First General Army (Group) : Eleventh, Twelfth, and Thirteenth Area Armies, stationed in northern Honshu, Aomori to Nagoya; Second General Army (Group): Fifteenth and Sixteenth Area Armies, stationed in southern Honshu, Nagoya to Shimonoseki, and Shikoku and Kyushu; and the Fifth Area Army which was directly under the Imperial GHQ, stationed in Hokkaido, Karafuto, and the

[120]

PLATE NO. 46

Organization of First and Second Demobilization Ministries, 14 June 1946

[121]

Kuriles. (Plate No. 37) For convenience in effecting demobilization, the Japanese boundary between Army Groups was altered to conform to the established boundary between the Sixth and Eighth U. S. Armies.12

A new but temporary command function of "Demobilization Commissioner" was created. The commanding generals of the First and Second General Armies (Groups) functioned as senior commissioners. Under the Ministers of War and Navy and the Chief of the General Staff, all commanders of units down to and including divisions operated as "commissioners"; while lower echelon commanders did not rank as commissioners, they were responsible for the demobilization of their own units. Under this organizational framework, the Japanese War Ministry completely demobilized 1,961,368 troops without incident or disorder between August and October 1945.13

The Japanese surrender delegation in Manila reported on 19 August that the strength of their naval personnel on 1 August was 1,024,255.14 These forces were organized into the major commands of Naval Section of the Imperial General Headquarters, Fleet Headquarters, Southwestern Area Fleet, Southeastern Area Fleet, and combined Naval Force Headquarters, plus ten naval station units, five area fleets, three air fleets, and one combined command corps.15 These naval units under direction of the Navy Ministry were responsible for demobilizing the once powerful Imperial Navy.

On the recommendation of the theater intelligence, the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters was abolished on 13 September, a decisive step toward Japan's demilitarization.16 Responsibilities formerly held by the Imperial General Headquarters were transferred to the Japanese War and Navy Ministries.17

By mid-September approximately 55 percent of the total of 2,353,414 army strength had been demobilized.18 By October some 83 percent of the original strength was out of the army; on 15 October, the tentative target date assigned by SCAP,19 the remaining tactical units that had not been disbanded were attached to their original depot headquarters for demobilization. All military forces in Japan were demobilized by December.

The largest of the three major Japanese ground force units was the First General Army (Group). This Army of 852,060 men, stationed in the northern Honshu area, was over 90 percent demobilized by October. Transportation difficulties, aggravated by a heavy typhoon and floods which further disrupted an already badly damaged rail system, slowed up demobilization of the Second General Army (Group); of its total of 700,723 men, about 75 percent was discharged by October; in November, demobilization was nearly complete.

The strength of the Fifth Area Army was approximately 150,700 men; of this force 72,600 were located in the Kuriles and Kara-

[122]

futo, under Soviet control. The demobilization rate was obviously dependent upon the progress of repatriation. The Soviets, however, did not begin returning prisoners until December 1946, and in December 1948 approximately 408,700 were still held in Soviet areas. In comparison, over half of the Fifth Area Army, stationed in Hokkaido, was 87 percent demobilized by 24 September 1945; by the end of November, all personnel under SCAP jurisdiction had been released.20

The Navy data presented by the surrender envoys at Manila was ultimately found to be inaccurate. Navy strength in Japan proper, stated to be 1,024,225, was later established at 1,178,750. However, naval demobilization proceeded at a more rapid rate than that of the Army. By 10 September approximately 82 percent of the total naval strength in Japan had been demobilized; by the end of November the only personnel on duty were those who had been discharged from the Navy and were employed by the Second Demobilization Ministry in a civilian status. They continued to work on essential naval tasks, such as mine-sweeping, operating disarmed vessels engaged in repatriation shipping, and maintaining Japanese war ships held for the Allied Powers. In addition to service personnel, the Japanese Navy at the end of the war employed approximately 739,000 civilians as workers and employees in naval arsenals, construction gangs, and other affiliated jobs; with the exception of those required in the demobilization program these civilians were promptly dismissed.

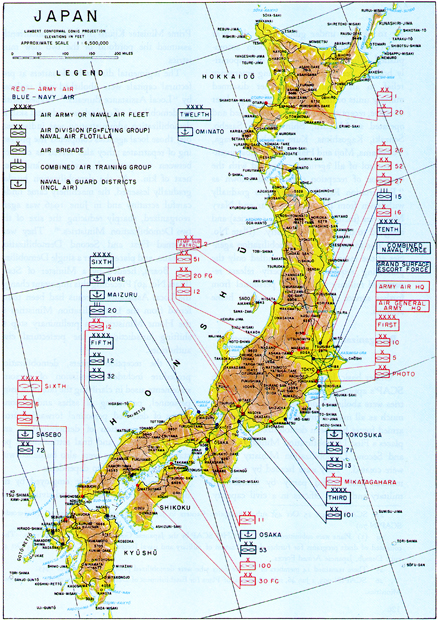

All personnel of both the Army and Navy Air Forces stationed in the four islands of Japan. (Plate No. 38) were reported at a strength of 262,000 Army and 291,537 Navy. Air Force personnel outside the Empire were discharged together with other forces and were not listed or handled separately. Ninety-five percent of the Air Force personnel in Japan was released by October; by the middle of December the Japanese Army and Navy Air Forces ceased to exist, and what was left of their installations and equipment was either destroyed by the Occupation forces, saved for reparations, or converted to civilian use.

Demobilization of Overseas Forces

At the same time that the home forces were being disbanded, the program for repatriating and demobilizing the Japanese forces overseas was also initiated. The overseas forces at the close of the war consisted of approximately 3,450,000 service personnel and over 3,000,000 civilians. The repatriation of these began promptly after surrender and progress was comparatively rapid in all areas except those controlled by the Soviet Government.21 The speed with which troops were demobilized in Japan obviously could not be duplicated for those overseas; the time element in the mechanics of repatriation was the delaying factor.

Japanese military and naval commands in appropriate port areas initially processed returning repatriates (civilian and military) through the existent machinery previously used by the Japanese Army and Navy in the deployment of their forces. On 28 September SCAP directed the Japanese Government to establish repatriation reception centers at designated ports.22

[123]

PLATE NO. 37

Disposition of Japanese Army Ground Forces in the Homeland at the Time of Capitulation,

18 August 1945

[124]

PLATE NO. 38

Japanese Army-Navy Air Dispositions, 15 August 1945

[125]

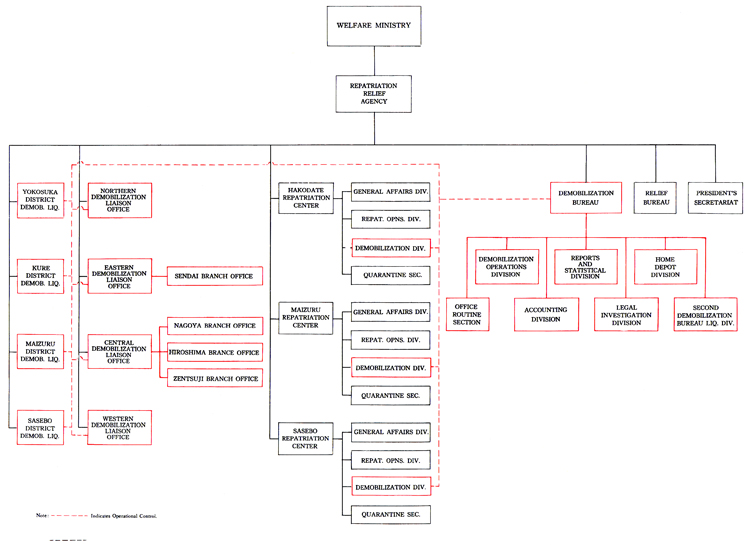

By 10 October under guidance of the War and Navy Ministries this had been accomplished. The centers were capable of temporarily housing, feeding, and extending emergency relief to all repatriates, whether disarmed military units or individuals. Following a later directive, reception centers were established and operated at Maizuru, Shimonoseki, Sasebo, Senzaki, Kagoshima, Kure, Hakata, Uraga, Yokohama, Moji and Hakodate.23 Subsequently, control of all agencies concerned with the operation of reception centers and known as "Repatriation Relief Bureau" was gradually withdrawn from the Japanese War and Navy Ministries (including succeeding agencies) and assigned to the Welfare Ministry. (Plate No. 39) The former military demobilization agencies at the reception centers handled only the processing required to properly release repatriated military and naval personnel from further service and get them to their home stations.

Reorganization of the Demobilization

Machinery

Under basic Japanese plans prepared with SCAP's approval, the War and Navy Ministries were abolished on 30 November,24 in as-much as all major components of the Japanese armed forces had been demobilized.25 In their places a First Demobilization Ministry (Army) and Second Demobilization Ministry (Navy) were created. They were headed by a civilian minister and staffed partly by demobilized military and naval officers in a civil capacity. Prime Minister Kijuro Shidehara concurrently assumed the portfolio of the two new ministries.

The regimental district headquarters at prefectural capitals were abolished and replaced by "Local Assistance Bureaus." Staffed partly by demobilized officers whose technical skill in demobilization administration was indispensable, those local agencies completed the processing of repatriates; they also served as contacts between unrepatriated servicemen and their next of kin. As the demobilization burden gradually lessened, the machinery came under careful scrutiny and in June 1946 was again reorganized, sharply reducing the size of the two Demobilization Ministries.26 They were renamed First and Second Demobilization Bureaus, and placed under a single Demobilization Board, headed by a Minister of State. (Plate No. 40) Preceding this important change, the Local Assistance Bureaus had been transferred from the Demobilization Ministries to the Home Ministry as a preliminary step to shifting jurisdiction to the prefectural civil authorities.

In the reception centers, demobilization procedure included submission of personal statements, used in clarifying the fate of missing personnel, processing of ashes and personal effects of deceased personnel forwarded from overseas, preparation of demobilization and discharge reports, and final settlement of pay status. The centers were also burdened with furnishing initial aid to dependents.

All personnel who were employed by the demobilization agencies assumed civilian status

[126]

but continued to perform their duties until their phase of the job was completed,27 key personnel included specialist crews for mine-sweeping.

The basic organization of the Demobilization Board remained unchanged until it was dissolved on 15 October 1947. By this time over half its task had been completed.28 There had been a progressive and marked reduction in personnel of the Board, and repatriation centers at Uraga, Nagoya, Hiroshima, Hakata, and Senzaki were closed; the Second Demobilization Bureau's operation of repatriation shipping was discontinued in January 1947. Meanwhile, with the adoption of the new constitution and the Japanese Local Autonomy Bill on 3 May 1947,29 the Local Assistance Bureaus, previously placed under Home Ministry jurisdiction, became sections of the Welfare Department, on the prefectural level.

As a transitional step, the First Demobilization Bureau and its local agencies were transferred intact to the Welfare Ministry which was already partly operating the repatriation centers ; the Second Demobilization Bureau and its regional agencies were temporarily placed in the Prime Minister's office. The next step in the reduction of the demobilization machinery was the elimination of the Second Demobilization Bureau which was approved by SCAP on 10 January 1948.30 Its former functions of mine-sweeping, ship maintenance, and related necessary activities were assumed by the Maritime Bureau of the Transportation Ministry and the remaining associated activities were charged to the First Demobilization Bureau which became simply the Demobilization Bureau. By 31 May 1948 the number of repatriation ports and demobilization centers had been reduced to three-Hakodate, Maizuru, and Sasebo. At that time, the last remnants of the Japanese demobilization machinery were eliminated as independent agencies31 and their functions and responsibilities completely transferred to the Repatriation Relief Agency, Welfare Ministry.32 Within one month after the completion of repatriation and therefore of physical demobilization, the Japanese Government planned to decrease the size of the Repatriation Relief Agency to a small Repatriation Liquidation Bureau. The latter, in turn, was scheduled to operate for just one year. Only when the last Japanese servicemen had been returned to Japan could the demobilization of the Japanese armed forces be considered completed, and the existence of a well-integrated and efficient demobilization system terminated.33

Due to a later start (December 1946), temporary delays, and low monthly rate of repatriation of Japanese from Soviet controlled

[127]

PLATE NO. 39

The Demobilization Organs of the Welfare Ministry, 1 June 1948

[128]

PLATE NO. 40

Organization of the Demobilization Board, June 1946-October 1947

[129]

areas and Communist-dominated districts of Manchuria, an estimated total of 499,000 Japanese army and 2,000 naval personnel still had not been returned to Japan in July 1948.34

Since repatriates included both civilians and servicemen, the totals of repatriation and demobilization do not coincide. All repatriates who were in Japanese military or naval service at the time of surrender were demobilized promptly and formally upon arrival at a Japanese repatriation port, although final processing was completed at the Local Assistance Section of the returnee's home prefecture.35

An aspect of demobilization which was of great importance to the Japanese although not of direct concern to the Occupation was the verification of the fate of the large number of personnel missing in overseas areas. The continuation of dependency allowances, the necessity for issuing valid death certificates for legal purposes, and humanitarian obligations of the Japanese Government to the next-of-kin of missing service personnel made such verification indispensable. The demobilization agency was charged with this increasingly difficult and time consuming task. The Home Depot Division, a subdivision of the Demobilization Bureau combined with the prefectural Local Assistance Sections, performed the bulk of the work.

The deaths of 1,402,153 servicemen who, prior to the surrender had not been reported dead or missing in action, were verified; and by August 1948 only 76,960 were carried as missing.36 With a few exceptions, missing personnel were presumed to be dead.

[130]

Since no information was made available by the Soviet authorities concerning the Japanese troops detained in Soviet-controlled areas, it was impossible to determine the number of missing men among the Japanese forces which surrendered to the Soviets. Of the 900,000 Japanese servicemen estimated to have surrendered to the Soviet forces, only 436,000 had been repatriated by 31 July 1948, and at the end of 1948 the fate of many of those under U.S.S.R. control had not yet been fully determined.37

General MacArthur, realizing the difficulties encountered in effecting complete demobilization of all Japanese armed forces, directed activities toward the speed-up of the demobilization program in Japan and in areas under SCAP or AFPAC jurisdiction on a geographical basis. It was obvious that American commanders could do little to accelerate demobilization of Japanese forces held by the U.S.S.R. until international disputes had been resolved and mutual agreements reached.

In a radio report to the American people on 15 October 1945, General MacArthur summarized the achievements of initial Occupation objectives:38

Today the Japanese Armed Forces throughout Japan completed their demobilization and ceased to exist as such. These forces are now completely abolished.

I know of no demobilization in history, either in war or in peace, by our own or by any other country, that has been accomplished so rapidly or so frictionlessly. Everything military, naval or air is forbidden in Japan.

This ends its military might and its military influence in international affairs. It no longer reckons as a world power either large or small. Its path in the future, if it is to survive, must be confined to the ways of peace.

Approximately seven million armed men, including those in the outlying theaters, have laid down their weapons. In the accomplishment of the extraordinarily difficult and dangerous surrender of Japan, unique in the annals of history, not a shot was necessary, not even a drop of Allied blood was shed. The vindication of the great decision of Potsdam is complete.

Nothing could exceed the abjectness, the humiliation and finality of this surrender. It is not only physically thorough, but has been equally destructive on Japanese spirit. From swagger and arrogance, the former Japanese military have passed to servility and fear. They are thoroughly beaten and cowed and tremble before the terrible retribution the surrender terms impose upon their country in punishment for its great sins.

Again, I wish to pay tribute to the magnificent conduct of our troops. With few exceptions, they could well be taken as a model for all time as a conquering army. Historians in later years, when passions cool, can arraign their conduct.

They could so easily-and understandably-have emulated the ruthlessness which their enemy have freely practiced when conditions were reversed, but their perfect balance between their implacable firmness of duty on the one hand and resolute restraint from cruelness and brutality on the other, has taught a lesson to the Japanese civil population that is startling in its impact.

Nothing has so tended to impress Japanese thought -not even the catastrophic fact of military defeat itself. They have for the first time seen the free man's way of life in actual action and it has stunned them into new thoughts and ideas.

The experience of an American lieutenant in an encounter with a Japanese armored column is typical of many similar events that occurred in the initial days of the Occupation. A jeep bearing a 43rd Division lieutenant was spinning along the road from Kazo to Kumagaya when an approaching cloud of dust resolved itself into a Japanese tank company moving to a

[131]

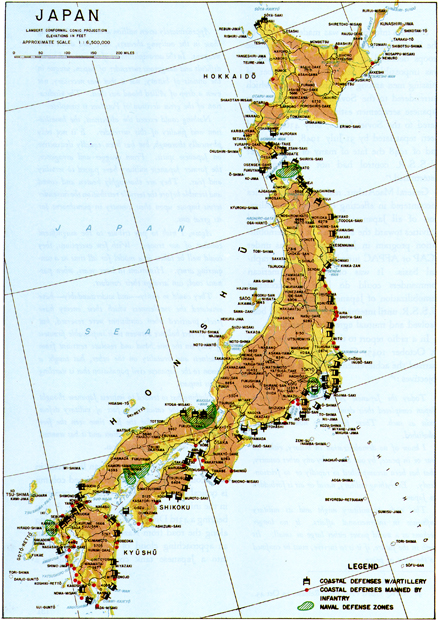

PLATE NO. 41

Japanese Coastal Defenses, 18 August 1945

[132]

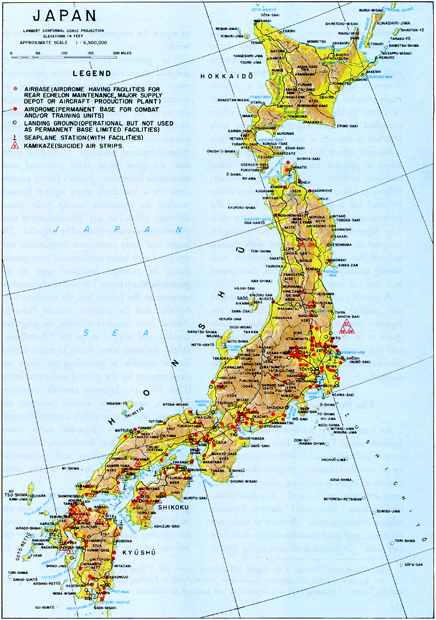

PLATE NO. 42

Japanese Airfields, 15 August 1945

[133]

demobilization center. As the lead tank stopped to permit passing, the jeep driver cautiously skirted it to the left on the narrow road. The soft shoulder crumbled and the American found himself tilted at a perilous angle with his vehicle mired in the soft muck of a rice paddy. Climbing out, the officer scratched his head and pointed to a cable attached to the side of one tank. Meanwhile a Japanese officer had come running up and asked in passable English if the tank driver had been at fault. Assured to the contrary, he barked orders to his men and the tank driver jockeyed his tank into position, hooked the cable on the jeep and pulled it back on the road. The Japanese captain bowed his apologies, accepted an American cigarette with thanks, ordered his tank column to continue and, waving amiably to the American, disappeared in a cloud of dust.

A month earlier these men would have shot one another on sight. Significantly, the Japanese armored unit was travelling without guard to be demobilized; the Americans and and the Japanese alike were integrated in a demobilization program which was evidently successful.39

As remarkable as the demobilization of the Japanese armed forces had been, it would have been of little value had it not been accompanied by an equally exhaustive program designed to dispose of Japanese weapons, armament, equipment, and other war materiel. The demobilization process transported former Japanese soldiers to their homes, left them to their own resources, and gave them freedom to lead their own lives. It provided an accounting system to report the progress of demobilization to the world.

The problem of disarmament and the disposal of war materiel, however, proved to be more difficult ; considerable stocks of war equipment were dispersed amid the tangled masses of fire blackened girders, in thousands of caches located deep in the hills, in carefully constructed tunnels and warehouses, and over miles of Japanese landscape. Along the shores near the great ports, there remained many permanent fortresses. Japan's frantic preparations for a last ditch stand against invasion resulted in numerous hastily built coastal defenses. (Plate No. 41) The majority of these coastal defenses were manned by brigades. The larger and more permanent installations were equipped with heavy artillery and were concentrated in strategic locations such as the peninsula which forms Tokyo Bay, the northern entrance to the Inland Sea, the southern tip of Kyushu, and the coastline around Fukuoka. Almost three hundred airfields, ranging from bomber and supply strips to "Kamikaze" strips, sheltered some 6,000 Japanese combat aircraft capable of providing air cover and close support for the ground and naval forces. (Plate No. 42) Japanese arsenals, munitions factories, steel plants, aircraft factories, and ordnance depots were widely scattered throughout the country.40 Japanese naval vessels consisting of carriers, battleships, destroyers, submarines, and auxiliary and maintenance craft were anchored in all of the major ports.

The initial disarmament procedures complied with the instrument of surrender and with early SCAP directives. The Japanese troops turned over their individual weapons to unit officers, who in turn assembled them in the

[134]

supply rooms, warehouses, and depots formerly used by the Japanese Army. With the prompt disarmament and demobilization of the individual soldier the way was cleared for the disposal of more bulky war equipment.

As soon as the surrender arrangements were made, the four small islands protecting Tokyo Bay were vacated by the Japanese and the Allied Navy entered the Bay without a shot being fired. The Japanese had cleared the important naval installations of all personnel except for skeleton crews, demilitarized all coastal defense and antiaircraft installations, and had marked the latter with large white flags. When the initial landing parties came ashore, Japanese officers and guides led them to the facilities available at the Yokosuka naval base, thus setting a pattern for a peaceful occupation.

The burden of location and disposal of ammunition, explosives, military stores and any other property belonging to the Japanese forces was placed upon the Japanese; they were ordered to collect all war materiel and assemble it as directed by the local United States commanders.41 Items which could not be readily transported were reported as such and processed later.

Spot inspections covering all of Japan, completed by 1 October 1945, attested to the full compliance with surrender terms by the Japanese Army and Navy Air Forces. Except for a few types which were preserved for technical air intelligence purposes, all aircraft were at that time grounded and were in the process of being destroyed. Initial destruction methods of enemy aircraft employed by the Occupation forces are typified in the following account:42

With the XI Corps Artillery in Mito-Two of the white peace negotiation planes bearing green crosses were among the 1,500 Japanese aircraft destroyed during the past 12 days by men of the 637th Tank Destroyer Battalion which is located just northeast of Tokyo.

Moving in on 12 airfields, and covering a ground area of 800 square miles, these men have organized into what they call " Destruction Incorporated" crews. A crew consists of five men, a Japanese full track prime mover and a gas pump spray mounted on a Japanese truck.

The system for destruction is simple, but believed to be foolproof. Two men on the prime mover pull the planes to the selected burning area. One man searches the entire plane for bombs and ammunition. Another member punctures all gas tanks to prevent explosion. The remaining man stands by the gas pump spray and at the signal "all clear" sprays Japanese synthetic gas over the plane to be destroyed. It is then ignited and the crew moves on to the next aircraft.

Because of the large number of agencies involved in the destruction or scrapping of Japanese aircraft and because of the variations in nomenclature and other statistics, exact figures of planes destroyed were not available. However, the Occupation authorities made certain that there were no Japanese planes in operational existence in the four home islands. During the early days of the Occupation many of the planes were disabled with no intent to salvage materials. That procedure was later discarded in favor of an economical scrapping program. Dismantling naturally proceeded at a slower rate than burning or demolition, but the salvaged items were useful in aiding

[135]

restoration of the war torn Japanese economy.43

Surrendered War Materiel: Disposition

Prior to the Occupation of Japan it was anticipated that the quantities of Japanese general war materiel would be enormous and tentative plans were made to dispose of it. Based on plans and directives from technical agencies and ample experiences in other theaters, the program for the disposition of this materiel was formulated on the premise that large numbers of Japanese service troops and adequate numbers of Japanese military vehicles would be available. However, in many areas of Japan the military forces had been completely demobilized prior to the Occupation. Vehicles were already lacking both in quantity and quality. Completion of the disarmament program was delayed as the personnel used in final disposition of the materiel consisted of Japanese laborers, a limited number of Japanese technicians, and specialist crews from United States forces. Tactical troops were often used initially in congested areas to perform the work of destroying the materiel as it was located or to oversee its transportation to waterfronts for loading and dumping. Army LCM's and Navy craft were used for this purpose. As fast as Japanese ships and crews could be substituted, the United States personnel were relieved. In the Sixth Army zone during the month of November 1945, at least ten ports were in operation, and approximately 4,500 tons of ammunition were disposed of daily.

One of the most interesting features of the disarmament program was the disclosure of the precarious condition of the Japanese defending forces in the home islands. After Allied victories of Iwo Jima, Okinawa, and the Philippines and the establishment of Allied naval blockade of China, only the troops in Japan were supplied by the homeland. On 31 August 1945 the Japanese reported on hand 1,369,063 rifles and light machine guns with limited ammunition of only 230 rounds per weapon. Records later indicated that actually some 2,468,665 rifles and carbines were received by the Occupation forces and later disposed of. The Japanese reported more artillery ammunition than small arms ammunition. Ammunition for the grenade launcher, often known as the "knee mortar," was also more plentiful; some 51,000,000 rounds were reported, or an average of 1,794 rounds for each weapon.

As in the case of demobilization, the infantry regiment was also the chief instrument in the disarmament program, charged with seizing all Japanese military installations and disposing of all confiscated materiel. As inventory lists were received from the Japanese, reconnaissance patrols, consisting of an officer and a rifle squad, made the rounds in the regimental area to verify these inventories and to search for any unreported installations or caches of materiel. The infantry company became the working unit

[136]

Japanese laborers place gasoline drum under plane to be destroyed, Kyoto, Japan.

Japanese tanks are rendered impotent by use of dynamite prior to scrapping.

PLATE NO. 43

Scrapping of Japanese Equipment, October 1945

[137]

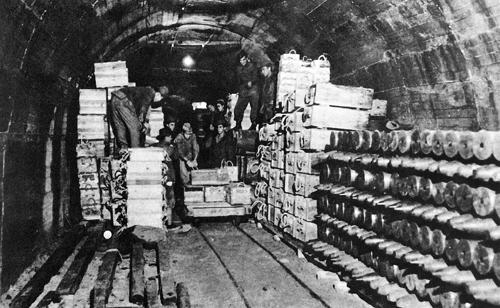

which performed supervision of disarmament and disposal of equipment. Among unreported installations was an extensive underground fighter aircraft engine plant, with a capacity of 100 per month, which was discovered by 1st Cavalry reconnaissance units in the Tokyo area. The entrances to tunnels, which had been in the process of being extended and expanded during the war, were cleverly concealed and in all probability could not have been detected from the air.

It was found that some discrepancies noted in the Japanese inventories were due to the difference in Japanese phraseology and nomenclature and errors in translations. For example, at Matsuyama Air Base on Shikoku Island, "20 Needles" were thought to refer to some sort of Japanese aerial weapons. Examination by troops of the 24th Infantry Division proved them to be packages of ordinary sewing needles.

Ammunition and weapons, particularly small arms, could have been hidden easily by rebellious individuals or groups, only to be brought out at some later time in revolt against the Occupation forces. Apparently there were more than a few abortive attempts in that direction, for although the Japanese military commanders appeared to be acting for the most part in good faith in surrendering their arms and equipment, every month of the Occupation disclosed new caches of military supplies. Though the caches usually were not heavily stocked, their very existence was enough to indicate that the chain of Japanese responsibility had broken down somewhere. Thorough reconnaissance and inspection by the Occupation forces brought to light many situations which were resolved before they could become serious problems.44 For example, a check on the police stations in Aomori, Hirosaki, and Sambongi (all towns in Aomori Prefecture) produced some 1,880 rifles, 1,881 bayonets, 18 light machine guns, 505,260 rounds of rifle and machine gun ammunition, 46,980 rounds of blank ammunition, one case of TNT, and 150 military swords. Daily G-2 and CIC reports revealed many instances of smaller caches, sometimes in school compounds. Officials and teachers, when questioned, usually pleaded ignorance, and very often investigation did show that faulty dissemination of instructions had been the root of the trouble.45

The G-4 sections of the various commands were designated to supervise the disposition of war materiel and report on progress. Systems were established to indicate readily by means of maps and charts the type and class of supplies located in each dump, the status of disposition within each camp, the percentage of dumps recovered, and dumps returned to the Japanese. Continuous information was sent to all echelons regarding the locations of principal installations in their zones. All equipment, whether received by unit commanders or uncovered by patrols, was secured and labeled, the date and place of surrender or discovery indicated, a record made of the unit concerned, and a statement made to show that it had been acquired by the United States armed forces.46

[138]

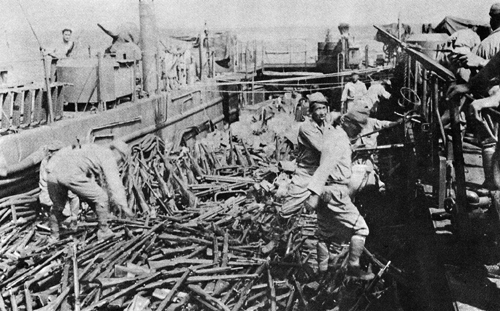

Japanese arms are inspected by an American soldier at the Katsuura School.

Ammunition is removed from storage cave at Takatsuki Dump, Osaka.

PLATE NO. 44

Disposal of Weapons and Ammunition, October 1945

[139]

Policy directed that enemy equipment would be destroyed or otherwise disposed of at the location where the Japanese turned it over to the disposal units. In destroying equipment other than ammunition and explosives, units were granted authority to use any practical method to render the materiel useless. The most common methods employed were: smashing, cutting with acetylene torches, burning with thermite grenades, or salvaging and melting down in blast furnaces. The resulting scrap was turned over to the Japanese Home Ministry. Negotiations were opened with steel plants and blast furnaces and contracts were drawn for the disposition of Japanese ordnance items. Arrangements were made to transport all such equipment to industrial areas for disposition. Destruction and re-smelting were accomplished rapidly and the ingot metal turned over to custody of Home Ministry representatives. Unfused artillery ammunition, bombs, and other inert projectiles were transported to former munitions factories where they were broken down to save both the explosive (for conversion to peacetime use) and the scrap metal.

Because the work was hazardous, special instructions were issued to all units for the immediate disposal of explosives, chemicals, and poison gases. All Japanese ammunition, bulk explosives, and other loaded equipment (ordnance, chemical ammunition, and engineer explosives) were destroyed without delay, with the exception of items desired for technical intelligence purposes. The principal method utilized was dumping into the sea at a depth in excess of 300 feet (later 600 feet). In areas that prohibited transportation to port facilities both detonation and burning were used to dispose of large quantities of munitions.

The most persistent difficulty encountered during the destruction of Japanese ordnance material was the acute shortage of qualified technical personnel, both Japanese and American. Even under normal circumstances the disposal of large quantities of Japanese ammunition and explosives would have presented many risks. With the loss of skilled technicians due to the demobilization program in Japan and the readjustment program in the U.S. Army, the task became even more complicated. Most of the work had to be done by slow and unskilled Japanese laborers; their apparent disregard for personal safety, combined with the language barrier, made the job dangerous. In accordance with agreements between the commanders of the Sixth U. S. Army and Fifth U. S. Fleet, Sixth Army assumed responsibility for disposition of naval equipment and installations ashore in western Japan. Some of Japan's largest naval installations were located in this area and the quantity of naval equipment increased the disposition problem considerably. Mine and bomb disposal specialists were borrowed from units in the Occupation forces, both Army and Navy, and ordnance explosive technicians from all available sources were located and utilized. Efforts to locate skilled technicians through the Japanese Home Ministry met with indifferent success. The rapidity of the demobilization of the Japanese armed forces had scattered these persons to all parts of Japan.

Under the best conditions, there is a certain peril connected with handling ammunition stored without adequate safety precautions. Japanese supply dumps were located in caves, on small islands, in marshlands, and in forests. In many of these areas seepage led to deterioration of highly sensitive ingredients such as fuses, safety devices, and packaging materials. The lack of safety devices on much of the Japanese equipment often made it impossible

[140]

Weapons of the Japanese 58th Army are loaded aboard LSM for dumping at sea.

Japanese ammunition on its way to the bottom of the Pacific Ocean.

PLATE NO. 45

Disposal of Weapons and Ammunition, October 1945

[141]

to remove and detonate the munitions in accordance with the usual safety procedures. Wherever this situation existed, the contents of a cave or tunnel were detonated at the site; this method, to mention one example, had to be used in handling 100,000 pounds of picric acid and blasting powder stored in a cave on Eta Jima. Deterioration had progressed to a point where movement of the stores was impossible and detonation on the spot became the only solution.

Progress of the munitions disposal program was sporadic. While disarmament of the troops and demobilization of personnel were accomplished rather rapidly, materiel disarmament took much longer. The destruction of munitions was equally slow but by the end of 1946 the program was reported 80 percent complete.47

Return of Demilitarized Materiel

to the Japanese

Throughout the process of disarmament, at no time was there any wanton destruction of materials and equipment; those stores which could be reasonably converted to civilian use were saved. There was urgent need for the return of salvaged materials to the economy of Japan. The country was impoverished. Many of its people were near starvation and generally in need of clothing. A large percentage of the nation's houses in the urban areas had been destroyed by heavy bombing. To alleviate these conditions in every possible way, the Occupation forces returned to the Japanese Government all Japanese military stores of food, extensive stocks of uniforms, rubber boots, garrison coats, medicines, and other items.48

[142]

Further need for these supplies developed with the inception of the repatriation program. More than six million Japanese were repatriated, many of them returning without sufficient clothing.49

Engineering and automotive equipment, vital in rebuilding devastated areas, was specifically excluded from the list of materials to be destroyed and much of it was returned to the Japanese. Initial requirements of the Occupation forces in such articles as nails, ropes, cement, wire, and plywood were met but, in general, these and other construction items were redistributed for Japanese civilian use.

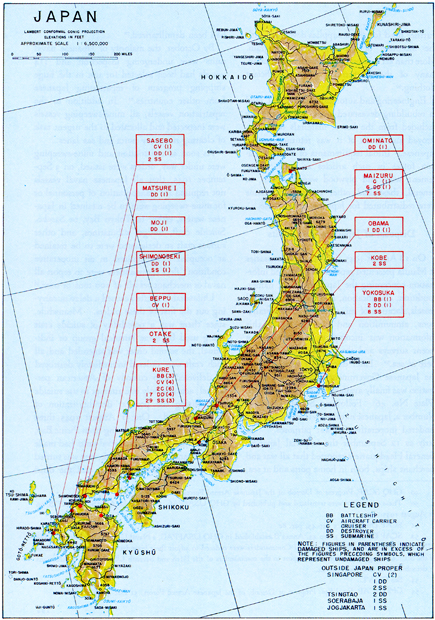

Disposal of Japanese Fleet Units

On 18 August 1945 the Japanese emissaries at Manila presented reports with detailed information concerning the Japanese Navy, names, condition, classification, and location of naval vessels, location of mined areas, shore installations, ammunition and fuel on hand; this information was incomplete due to lack of recent surveys and the fact that certain units were at sea.50 Later documents were filed by the Japanese Government and accurate information was finally available in early September. (Plate No. 46) Following SCAP Directive Number 2, Japanese naval vessels were promptly rendered inoperative for war purposes.51 As early as 12 September the Imperial Japanese General Headquarters reported that all war and merchant ships, both in home ports and at sea, had been demilitarized.52

By October, the majority of Japanese naval units were undergoing inspection and 114 vessels had been selected for use in the huge shipping program of repatriating Japanese from other countries.53 In addition to the repatriation vessels, all mine-sweeping vessels were inspected and allocated to the urgent task of clearing necessary ports and sea lanes.

As soon as repatriation and mine-sweeping were under way, orders were issued, on 3 September 1945, that all Japanese naval vessels not required for transportation of personnel or for mine-sweeping were to be retained in Japanese waters, either in Tokyo Bay, or Sasebo. Suicide craft, midget submarines, and other surface craft so designated were to be retained at occupied naval stations in an inoperative condition; fleet commanders were to report all naval or merchant vessels of 100 tons or over.54

Unfavorable weather caused a delay in carrying out the first of these orders. Meanwhile, since there was a possibility of suicide craft being used by some fanatical group or individual, the second order was amended and all such craft were ordered immediately destroyed or delivered into custody of American personnel; actually only one attempt to use suicide craft during the postwar demilitarization of Japan occurred. On 31 August 1945 three suicide craft were seen moving from Picnic Bay, Hong Kong, after British naval units had made their entrance. One was sunk, one was turned back to the harbor and sunk, and the third

[143]

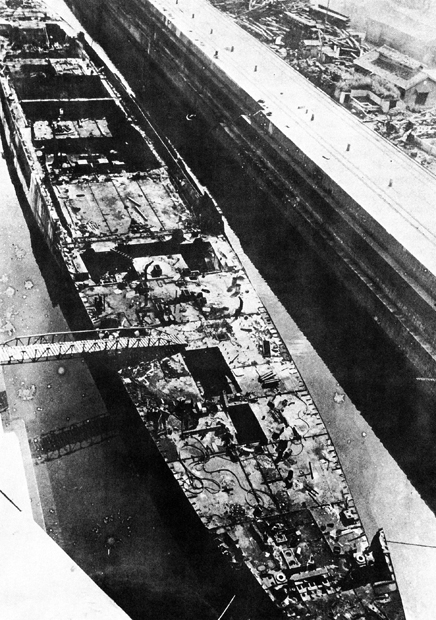

PLATE NO. 46

Disposition of Major Japanese Fleet Units, 1 September 1945

[144]

was beached and later destroyed.55

In Japan, various types of suicide craft were reported in twenty-four scattered port areas 393 midget submarines, 177 human torpedoes, and 2,412 suicide surface craft.56 By October over 90 percent of this fanatical arsenal was either destroyed or placed under immediate control of the Occupation forces. As the Occupation progressed, the remaining 10 percent, together with 141 additional midget submarines, was destroyed.

The general reports regarding all Japanese vessels, merchant and war, revealed 2,524 vessels of all kinds belonging to the Japanese Navy.57 By February 1946 the Second Demobilization Ministry was using 408 vessels of the former Imperial Japanese Navy-138 for repatriation, 269 for mine-sweeping, and one for transportation of fuel. Many of the ships so used were former aircraft carriers, cruisers, escorts, submarine chasers, transports, and hospital ships.

By mid-October 1946 the number of vessels employed by the Second Demobilization Bureau had been progressively reduced to 250 vessels, 89 in repatriation service and 160 in mine-sweeping activities. In the first month of 1947 all of these craft were withdrawn from control of the Second Demobilization Bureau and were reassigned to the Civilian Merchant Marine Committee. On 1 January 1948 the Second Demobilization Bureau's functions of mine-sweeping and ship maintenance, were assumed by the General Maritime Bureau of the Transportation Ministry. The last transfer of functions relieved the remaining military or naval demobilization agencies completely of operating any ships.58

On 12 February 1948 the Far Eastern Commission belatedly ordered an early completion of the disarmament and demobilization of the Japanese Armed Forces and, in general, approved the steps already taken by General MacArthur toward the completion of this gigantic task.59

Combatant ships of destroyer tonnage and less were divided among the United States, United Kingdom, Soviet Russia, and China when no longer needed in the service of the Occupation. Deliveries of the several lots were based on four separate drawings held in Tokyo. During the remainder of 1947 a total of 135 former Japanese naval ships were allocated and delivered to the four major Allied Powers.60

Japanese crews, consisting of former naval personnel, sailed all ships to ports previously specified by the receiving nations. The vessels assigned to the U.S.S.R. were delivered to the port of Nakhodka; the Chinese lot to Shanghai and Tsingtao; the United States lot to Tsingtao, Yokohama, and Yokosuka; and the United Kingdom lot to Singapore and Kure. Three ships in the first lot, all of the ships in the second lot, and the bulk of the third lot received by the United States were held in Japan for scrapping. In the four drawings, the U.S.S.R., the United States,

[145]

PLATE NO. 47

The Japanese Light Cruiser Ibuki in Drydock at Sasebo-64 percent Scrapped, 14 March 1947

[146]

and China received thirty-Four vessels each, and the United Kingdom thirty-two vessels.61 Smaller craft of one hundred tons or less were returned to the Japanese for use as fishing or cargo vessels, ferries, freight barges, and other peacetime purposes; those returned totaled some 200,000 displacement tons of shipping.

According to a plan prepared by COMNAVJAP and approved by SCAP on 2 April 1946, all former Japanese Navy combatant ships larger than destroyer class were to be completely scrapped within one year of their release from the repatriation service. Wrecked and heavily damaged ships were to be sunk in deep water. By October 1946 all submarines (a total of 151) had thus been disposed of and the scheduled scrapping of other vessels was well under way. Eighteen Japanese scrapping companies were assigned to carry out the disposal of the major ships.62

The scrapping and salvage work on former Japanese warships was almost completed in the the second half of 1948.63 The 421 former warships in the scrapping program ranged in size from the Ise, a 40,000 ton battleship, to small torpedo boats of about twenty tons. Types of craft included aircraft carriers, destroyers, destroyer escorts, cruisers, submarines, and high speed transports. Most of these ships had suffered damage during the war but were still afloat. Steel and other metals obtained from salvage were turned over to the Japanese Government as returned enemy material to be used in peacetime industries.64 Scrapping costs were high due to the high cost of carbide and the low market value of the scrap.

With the completion of the scrapping of the Japanese cruiser Tone, the last of the large remaining combat vessels above the 3,000 ton class was destroyed. On 15 January 1949 the U. S. Navy reported that the scrapping program and disarmament of the Japanese naval strength was complete: the Japanese Navy was extinct.65

[147]

Go to

Last updated 11 December 2006 |