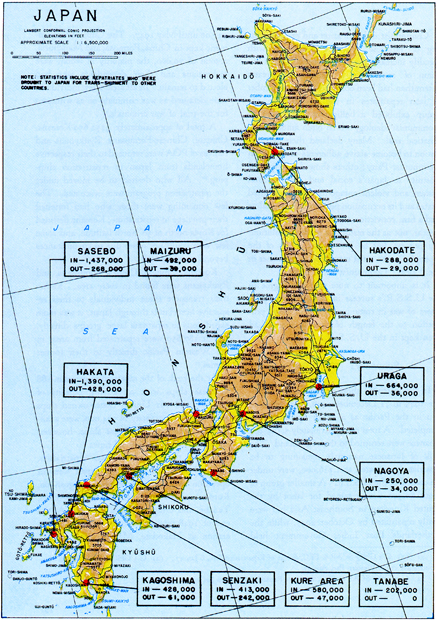

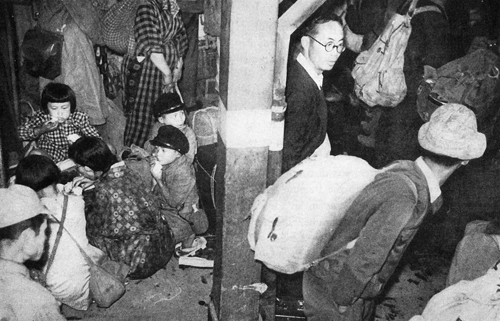

PLATE NO. 48

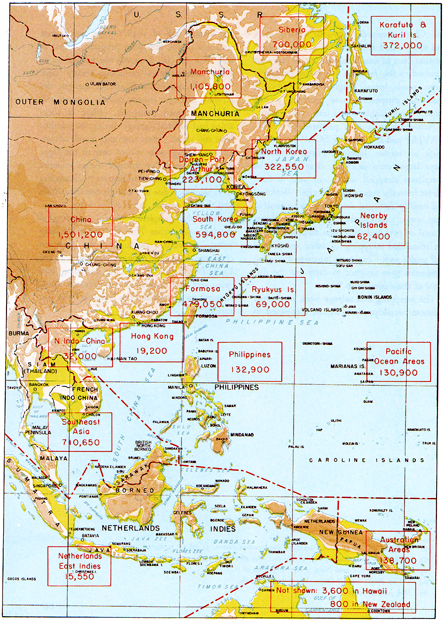

Japanese to be Repatriated: August 1945

[148]

CHAPTER VI

OVERSEAS REPATRIATION MOVEMENTS

At the end of the war over six million Japanese were scattered throughout the islands in the Western Pacific and on the Asiatic mainland. Their repatriation became one of the major problems confronting General MacArthur. Their early return to Japan was desirable for purely humanitarian reasons as well as for the purpose of easing the economic burden of the liberated countries. (Plate No. 48)

In addition, there were approximately 1,170,000 aliens in Japan, many of whom had been forcibly removed from their homelands. Early in September 1945 a large number of these displaced persons flocked to ports in southern Honshu and Kyushu, hoping thereby to obtain preferential treatment for their repatriation. This influx resulted in congestion and created health and sanitation problems which threatened public welfare in Japan. Recognizing this urgent problem, SCAP promptly initiated a program for mass repatriation, placing it under the staff supervision of G-3 in conjunction with the Naval High Command.

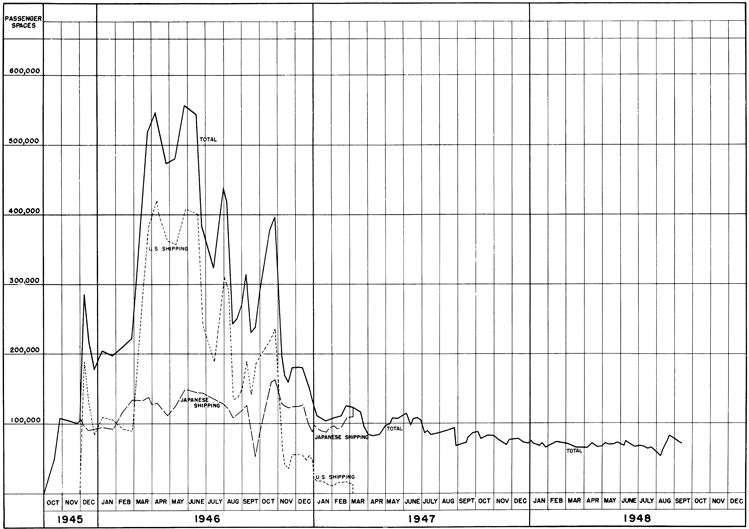

Mass repatriation can be divided into four phases. The first phase covered the initial period from 14 September 1945 to 28 February 1946. Throughout this period the only shipping available for repatriation was that which was recovered from the Japanese and such United States manned ships as could be utilized at this time. Evacuation from United States controlled areas in the Western Pacific was given priority.

During the second phase, 1 March to 15 July 1946, United States owned ships were made available to the Japanese to augment their own meager resources in shipping; repatriation from overseas areas was at its peak and reached a maximum rate of 193,000 persons per week. Throughout this period evacuation from Chinese and British controlled areas was emphasized. Approximately 1,600,000 Japanese were returned to Japan from these two areas alone.1

The third phase of mass repatriation covered the period from 16 July 1946 to 19 December 1946. It was marked by a decline in the numbers repatriated, owing to the diminishing numbers of repatriates delivered to embarkation ports from areas outside Japan.

Following 19 December 1946, the program was largely concerned with the repatriation of approximately 1,617,650 Japanese from Soviet controlled areas. Throughout the course of this fourth phase, however, approximately 100,000 Japanese were repatriated from British controlled Southeast Asia, a residual program substantially completed by October 1947.2

[149]

The general repatriation program was characterized by the large numbers moved, the fact that all repatriation had to be conducted over sea lanes, often over very great distances, and the amount of coordination which was necessary between SCAP and the various overseas area commanders.

This chapter covers only the details of mass repatriation of Orientals-in the Western Pacific, defined as that portion of the Asiatic-Pacific Theater west of the 180th meridian; it excludes the repatriation of Occidentals, diplomats, and other special categories since these were handled on their individual merits. The narrative is not final because at the end of 1948 repatriation of Japanese from Soviet controlled areas was still not complete;3 it does, nevertheless, cover the period during which a great mass of repatriates was moved and the agreements reached under which the remainder would be eventually returned home.

In arriving at a feasible solution to the problem of transporting more than seven and a half million persons over ocean areas, shipping not required to support the economy of Japan was made available from the remnants of Japan's once powerful navy and merchant marine. A variety of ship types were represented: aircraft carriers, cruisers, destroyers, three masted sailing ships, escorts, troop transports, hospital ships and merchantmen. It was necessary to demilitarize all naval ships before using them and the majority of vessels had to be converted to make them suitable for transporting personnel. All of the craft were in a very poor state of maintenance and repair, hence considerable work was necessary before they could be operated efficiently. The most suitable shipyards where this could be accomplished were located at Yokosuka, Kobe, Osaka, Kure, Sasebo, Maizuru and Ominato. While there was a lack of materials to be used in ship repair, many parts could be procured by stripping beached and sunken Japanese ships for spare parts and scrap metal. It was estimated that about 167 Japanese ships with a total passenger carrying capacity of 87,600 spaces could be operated 50 percent of the time. Sailors who had formerly manned ships in the merchant marine and navy were immediately available for assignment to repatriation ships. Operational control and supervision of maintenance was exercised by the U. S. naval representative of SCAP for merchant ships and by the commander of the U. S. Fifth Fleet for naval ships.

The necessary logistic support to the repatriation program was available from Japanese resources except for the supply of fuel oil for ships. In order to commence the program at an early date, oil used by repatriation ships was provided initially from United States sources.

Although rolling stock was somewhat limited, the rail system in Japan was relatively intact and could be utilized with little dislocation of normal functions for the transportation of personnel to and from ports. The ports and port areas, however, presented quite a different picture. Bombing by U. S. forces had caused widespread destruction of port facilities. Mines in the harbors, channels and inland waters precluded the use of many fine ports and made the operation of shipping in others extremely hazardous.

Since repatriation involved personnel in areas under various Allied commanders and

[150]

was to be implemented by the Japanese, closely centralized control was necessary.4 Under the concept of the Occupation, the machinery of the Imperial Japanese Government (IJG) was utilized for implementation of the repatriation program.

The threat of epidemics was realized, but this risk had to be accepted. Provisions for rigid quarantine procedures at points of entry in Japan were required; similarly, certain controls had to be established in Japan to prevent unauthorized traffic in goods, currency, financial instruments, and precious metals. To provide these controls, the flow of repatriates was channeled through designated focal points called "Reception Centers." Responsibility for their operation and maintenance was charged to the Japanese Ministry of Welfare, in conjunction with the demobilization machinery operated by residual military and naval personnel in a civil status.

SCAP evolved certain basic policies which with minor modifications governed the planned repatriation program throughout its implementation. The original policies were:5

a. Maximum utilization will be made of Japanese naval and merchant shipping allocated for repatriation of Japanese nationals.

b. Japanese naval vessels and those Japanese merchant vessels designed primarily for the transport of personnel and not required for inter-island or coastal passenger service, will be utilized for the repatriation of Japanese nationals.

c. Personnel to be repatriated will be transported on cargo vessels only to the extent that the cargo carrying capacity of the vessel is not curtailed thereby.

d. The Imperial Japanese Government will operate, man, victual and supply Japanese shipping used for repatriation to the maximum practicable extent.

e. First priority will be granted to the movement of Japanese military and naval personnel, and second priority to the movement of Japanese civilians.

f. All Japanese personnel will be disarmed prior to return to Japan proper.

g. In the evacuation of Japanese nationals from areas under the control of CINCAFPAC and CINCPAC, the former will prescribe the percentage of shipping allocated for repatriation purposes, to be employed in servicing the respective areas. Priorities for the evacuation of specific areas will be established as necessary....

h. In the evacuation of Japanese nationals from areas under the control of the Generalissimo, Chinese Armies, SACSEA, GOCAMF and the Commander in Chief, Soviet Forces in the Far East, SCAP will make the necessary arrangements.

The plan, as finally conceived, provided for the division of responsibility as follows:

a. SCAP

1) Completed the necessary arrangements with coordinate and subordinate commanders for the evacuation of repatriates.

2) Assumed responsibility for repatriates after they were embarked on SCAP-controlled ships.

3) Retained control of the repatriation fleet to include the allocation of shipping to the several areas concerned.

4) Issued necessary directives to the Imperial Japanese Government for: the reception, care, demobilization (of military and naval personnel) and transport to their homes of returning Japanese

[151]

repatriates; transportation from their homes in Japan to the evacuation ports in the case of the repatriates from Japan.

5) Supervised the over-all execution of the program.

b. Responsibility for the operational control of repatriation shipping and the supervision of its maintenance was vested initially in Commander, U. S. Fifth Fleet, insofar as it concerned former Japanese naval ships, and in Fleet Liaison Officer, SCAP, (FLTLO-SCAP) for former merchant ships.

c. The Imperial Japanese Government was charged with the execution of the provisions of the repatriation directives published by SCAR This included establishment, organization and operation of repatriation reception centers, transporting of repatriates to and from these centers, and providing of crews and supplies for repatriation ships. At the reception centers the IJG was required to subject each repatriate to physical examinations and quarantine procedure, as were necessary; inoculations against cholera and typhus, vaccination against smallpox, and disinfestation by DDT of person and baggage; screening for war criminals; inspection of baggage and persons to prevent unauthorized traffic in goods, financial instruments and precious metals. In addition, the following functions were performed at reception centers: rail and ship movements were coordinated; food and clothing, to be placed aboard repatriation ships or to be used at the centers, were assembled and distributed; returning Japanese soldiers and sailors were demobilized and furnished free rail transportation to their homes.6

First Phase: 17 September 1945-

28 February 1946

In order to save time, repatriation from United States controlled areas was set in motion concurrently with the preparation of the over-all program. Short range shipping was allocated to Korea and the Ryukyus, while long range shipping serviced more distant islands in the Pacific. Korea, the Ryukyus, and the Philippines were cleared expeditiously except for small remaining numbers of prisoners of war. For all practical purposes, mass repatriation from these areas was completed by January 1946. The rapid rate at which the U. S. Army Forces were redeployed to the Zone of Interior created an acute shortage of labor in the Ryukyus, Philippine Islands, and Pacific Ocean Area. To compensate for this shortage, authority was granted to retain temporarily prisoners of war and Japanese surrendered personnel in areas under control of U. S. Army Forces Western Pacific (AFWESPAC), U. S. Army Forces Middle Pacific (AFMIDPAC), and CINCPAC.

During this phase, arrangements were concluded with the Chinese Government, the General Officer Commanding Australian Military Forces and the Supreme Allied Commander, Southeast Asia Command, for repatriation of Japanese nationals under their control. These arrangements were relatively simple. It was agreed that the governments and commands evacuating Japanese nationals were to be responsible for delivering repatriates to designated ports of embarkation, processing them for communicable diseases, and inspecting for excesses in amount of authorized articles in their possession and for contraband. The overseas commanders were further charged with overseeing proper loading of ships prior to departure and furnishing necessary emergency supplies.

Allocation of shipping to the various areas was based on the original number of persons to be returned from each area and the geographical distance from Japan.

When reduced to passenger spaces, however, the Japanese shipping became completely in-

[152]

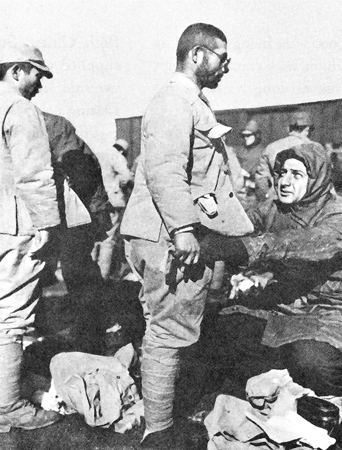

Ashes of comrades are carried from Rabaul for delivery to families in Japan.

Japanese commanders receive Allied instructions on disarmament and repatriation.

PLATE NO. 49

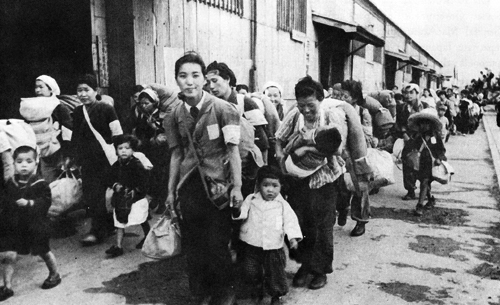

Repatriation Begins

[153]

adequate. For this reason, representations were made to Soviet Russia, China, Southeast Asia Command, and Australia to utilize Japanese shipping then under their jurisdiction. This shipping was to be used under SCAP control to support a minimum economy of Japan and for repatriation. SACSEA responded by reporting fourteen ships with a total carrying capacity of 23,000. These ships eventually were operated for repatriation purposes under SCAP control. Repeated efforts to obtain shipping from China and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics were unproductive. Australia reported that she had confiscated no shipping which was suitable for this purpose.

During this phase, the repatriation of non-Japanese from Japan was progressing satisfactorily. Of those desiring repatriation, 58 percent of the Koreans, 63 percent of the Formosans, 97 percent of the Chinese, and 12 percent of the Ryukyuans (Japanese) were returned to their respective homelands.7

The naval organization controlling repatriation shipping underwent considerable change during this period. A U. S. naval organization, known as the Shipping Control Authority for the Japanese Merchant Marine (SCAJAP), was established in Tokyo on 12 October 1945.8 On 6 March 1946, when the office of Commander, Naval Activities, Japan (COMNAVJAP), was established, SCAJAP was integrated into that office as an important subdivision, but continued to perform the same functions. In dealings with the Japanese Government, SCAJAP worked through the Ministry of Transportation and the Ministry of Navy until the latter went out of existence on 31 December 1945; thereafter SCAJAP worked through successive agencies established under the Japanese naval demobilization program.9

Early in 1946 it became apparent that, statistically, repatriation in the Western Pacific would take several years unless the shipping resources of the Japanese were substantially augmented; action was accelerated to increase shipping assigned to repatriation. Following this policy, 100 U. S. Liberty type cargo ships, 100 LST's, and sufficient U. S. hospital shipping to move 25,000 patients before July 1946 were made available to SCAP for repatriation early in March 1946. These ships were operated under SCAJAP and were manned by Japanese crews.

In the first half of January 1946, operation procedures were incorporated in a single paper entitled: "Agreements Reached at Conference on Repatriation, January 15-17 1946, Tokyo, Japan." Similarly, all directives to the Japanese were combined in a single directive during March of the same year.

Under the broad concept of the Occupation, the Sixth and Eighth U. S. Armies established troop detachments at each of the reception centers so that close supervision over the Japanese could be exercised. When the Sixth Army was inactivated in January 1946, the Eighth Army became the sole local supervising agency.

As the first phase neared completion, the basic policies had been published and operational procedures had been established and tested. A good beginning had been made since approximately a million and a half Japanese had been returned to their homes and over 800,000 non-Japanese evacuated from Japan.

[154]

SCAP was ready to speed up the program of repatriation.10

Second Phase: 1 March-15 July 1946

During the second phase of the repatriation program, emphasis was placed on evacuating over a million and one-half Japanese in China proper and Formosa, and the three quarters of a million in British areas in the Pacific.11 The largest portion of the burden was borne by United States shipping, made available early in 1946.

Liberty ships from War Shipping Administration, vessels released in the Philippines, and Navy LST's released in the Marianas began arriving in February. They were turned over to the Imperial Japanese Government under an indemnity agreement; the Japanese were to be fully responsible for manning, supplying and repairing. Although the ships had been demilitarized prior to arrival in Japan, there was considerable refitting to be done to make them suitable for carrying passengers. Since the ships' crews were to consist of Japanese, all signs and instructions had to be changed rom English to Japanese. SCAJAP was responsible for training the crews and, in carrying out this task, did an outstanding job.

The ships were ready for use in early March and were initially assigned to shuttle between China (including Formosa and Japan in accordance with the schedules agreed upon at a conference in Tokyo the preceding January. Except for minor departures, the original schedules were followed. Formosa was cleared for all practical purposes by 12 April and China proper by 12 July 1946. Vast numbers were moved under oriental passenger standards -the carrying capacities of the Liberties and LST's were raised to 3,500 and 1,200 passengers respectively, an increase of 1,000 and 300 each over the maximum number established by the U. S. forces during the war for the same type ships.12

The problem of clearing the China Theater was complicated by a cholera epidemic which occurred among repatriates who were being returned from Haiphong, French Indo-China; Canton, China; and Kiirun, Formosa. This situation interfered considerably with the repatriation program since infected ships were quarantined and the passengers held aboard, examined, and treated until medical authorities were satisfied that they no longer constituted a hazard to the public health of Japan. Some of these ships were held in quarantine as long as thirty days. To indicate the magnitude of the problem, there were at one time twenty-two ships with a total of 76,000 repatriates in quarantine at Uraga, Japan. A total of 438 persons died of cholera before the epidemic was brought under control; only the determined efforts of the Public Health and Welfare Section of SCAP and port quarantine agencies prevented introduction of widespread epidemics into Japan.

During the peak of repatriation from China, great demands were made on the reception centers and rail system in Japan. In two successive weeks reception centers in Japan handled loads of more than 185,000 persons per week. Effective prior planning by reception centers and transportation units permitted the housing, welfare, and ultimate absorption into

[155]

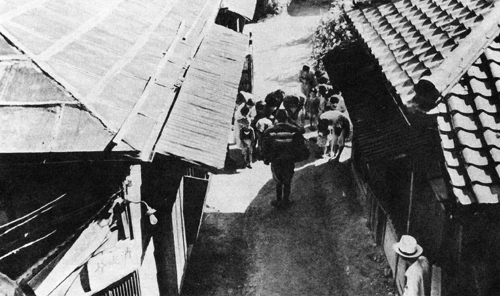

Troops pack their kits near Shanghai preparatory to the final voyage to Japan.

Homeward Bound: Yokosuka

PLATE NO. 50

Shanghai to Yokosuka

[156]

Japan of these large numbers without any major difficulties.13

When United States owned ships began operating in March, long range Japanese ships, previously on the China shuttle, were diverted to evacuate over three quarters of a million Japanese in Southeast Asia and Australia. In April, when the requirements for shipping from China decreased appreciably, authority was obtained from the U. S. Joint Chiefs of Staff to also utilize United States ships for repatriation from these areas. As a result, by August 1946, Australia and Southeast Asia were cleared of all Japanese, except for war criminals and those retained for labor.

In addition to returning Japanese from China, Australia, and Southeast Asia, repatriation shipping under the control of SCAP transported about 65,000 Koreans from Chinese controlled areas to Korea. Movement of these nationals was an extension of the United States policy of repatriation, as expressed in the Potsdam Declaration, and was executed under instructions from the U. S. War Department.

In February 1946, after the initial rush to be repatriated had subsided, there was a marked decrease in numbers who wished to be repatriated from Japan. This was particularly noticeable among Koreans. Most commonly advanced reasons for this change of heart were the poor economic and political conditions reported as existing in Korea, and the restrictions against removing goods and currency from Japan. In order to determine how many persons still desired to be returned to their homelands and to set a target date for the completion of SCAP's responsibilities to repatriate all non Japanese, it was decided to register all Koreans, Formosan and Chinese nationals, and Ryukyuans (actually Japanese).

For those who indicated a desire to be repatriated, the privilege of review by United States authorities of legal proceedings as ruled by Japanese courts was continued. The Japanese Government was also held responsible for their continued welfare, transportation to reception centers, and ultimate embarkation on repatriation ships. For those who did not indicate a desire to go back to their home countries, these privileges were withdrawn. Thereafter, according to established policies, they were required to live on the indigenous resources of Japan. Furthermore, the decision to remain in Japan once made, was considered irrevocable and such persons were no longer entitled to the privilege of repatriation. This same policy was followed in respect to persons who were scheduled to be repatriated, but who failed to report where ordered. Exceptions were made only when such failures to report were due to unavoidable circumstances. In furtherance of this policy the mass return of Chinese nationals and Formosans was considered completed in May 1946. The repatriation of Koreans continued at a sluggish rate of about 6,000 per month during the period.

Efforts were again made to initiate repatriation from Soviet controlled areas on the local military level. In January 1946 the Commanding General, U.S. Army Forces in Korea, conferred at Seoul with the Commanding General of the Soviet Forces in the Far East, in order to effect repatriation from North Korea to Japan. These negotiations were unsuccessful due to certain demands made by the U.S.S.R., chiefly the furnishing of food and rail transportation through Korea for the repatriates. In Japan a plan for repatriation from North Korea was proposed to the Soviet member of the Allied Council for Japan. No agreement could be reached on matters

[157]

concerning the supply of fuel oil for repatriation ships and the granting of preferential treatment to repatriates destined for North Korea.

Early in June it was realized that shipping available for repatriation far exceeded the number of repatriates that could be sent to evacuation ports. Mass repatriation had reached its peak and was then on the decline.

Third Phase: 16 July-

31 December 1946

With China proper cleared and Southeast Asia shipping requirements established, there was a lull in repatriation activities beginning in mid-July 1946. The number of repatriates to evacuation ports dropped to negligible figures except in the case of Hulutao, Manchuria, from which repatriates were being evacuated at a rate of 7,500 a day. Meanwhile, except for unproductive laborers, repatriation from United States controlled areas had been temporarily suspended. The British announced their intention to retain 113,500 PW's in their areas until some time in 1947. By this time South Korea had been cleared.

A review of repatriation shipping requirements was made and at this time it was decided that fifty-five U. S. Liberties could be sent back to the War Shipping Administration. These ships were returned to the United States by Japanese crews who later came back to Japan in other SCAP Liberties dispatched from Japan. The first of these ships sailed for the United States on 15 August 1946.

The lull was of short duration. For some time SCAP had been faced with the question of retaining Japanese nationals in United States controlled areas. Due to the rapid demobilization of our own forces and the difficulty of obtaining satisfactory labor, the major commanders were desperately in need of the services of Japanese PW's in order to perform the important task of terminating our wartime bases.

The issue was squarely met on 8 August 1946, when SCAP announced plans to return all Japanese PW's and displaced personnel in United States controlled areas by the end of the year. This affected some 45,000 in the Philippines, 5,000 in Hawaii, 7,000 in the Pacific Ocean Area, and 12,000 in Okinawa. These were duly evacuated in three equal increments from each of the above areas during the months of October, November, and December.

Return of Okinawans was authorized during the latter part of July after the transfer of military government from CINCPAC to CINICAFPAC was effected on 1 July 1946. The plan, involving the return of some 150,000 from Japan and Formosa during the period of 15 August to 31 December 1946, was organized and implemented without any major problems.

The flow of Japanese from Hulutao, Manchuria, increased progressively until by the end of September over 10,000 were being evacuated daily. Because of a cholera epidemic in Hulutao, it was difficult to supply shipping to maintain the above rate, as all ships from cholera ports were held in quarantine until cleared by public health officials. With the advent of cold weather, the threat of this disease diminished and the critical shipping situation eased. Manchuria was cleared by the end of October 1946, except for certain groups in areas controlled by Chinese Communist forces and a limited number of technicians retained by the Chinese Government. These were estimated to number about 68,000.14

[158]

It is interesting to note that while the Chinese Nationalist forces and Chinese Communist forces were conducting civil war, the truce teams under General Marshall were instrumental in obtaining an agreement from the Communists to repatriate the Japanese under their control. Because of this understanding, Japanese nationals in Communist held areas of Manchuria were sent home through Hulutao which was under control of the Nationalist forces (with exception of the 68,000 noted above).

During this period General MacArthur's Headquarters directed evacuation of some 89,000 Japanese nationals released from the British controlled areas in Southeast Asia. On various occasions, General MacArthur requested governmental action to induce the British to return all their Japanese nationals by 31 December 1946. These efforts failed and some 80,000 remained in Malaya and Burma at the year's end.

On 26 September the representative of the Soviet Government in Japan announced to General MacArthur that they were ready to repatriate Japanese PW's and other Japanese nationals; this was quite a conciliatory attitude on the part of the Soviets after ignoring (since January 1946) continuous SCAP attempts to start repatriation. Action was immediately taken to conclude an agreement governing this repatriation. The negotiations moved slowly and it was not until 19 December 1946 that full agreement was reached. Under its terms the Soviets guaranteed to return all Japanese surrendered personnel and all Japanese civilian personnel who desired to come back to Japan.

General MacArthur agreed to furnish the necessary shipping and to assume all responsibility for repatriates from time of embarkation. He accepted a rate of 50,000 per month although he had offered to evacuate up to 360,000 per month. A total of approximately 30,200 were returned from North Korea, Siberia, Dairen-Port Arthur, Sakhalin, and the Kuriles during December.15

Repatriation from Japan continued slowly. By the end of 1946 all non-Japanese and Ryukyuans who desired repatriation had either been repatriated or had forfeited their privilege to return. The only exceptions were those destined for northern Korea and a few others who could not move due to circumstances beyond their control. These latter cases were reviewed and decisions were made on their individual merits.16

Fourth Phase: 1 January 1947-

31 December 1948

At the close of 1947 approximately 625,000 Japanese had been repatriated from Soviet controlled areas (Dairen, Siberia, North Korea, and Karafuto-Kuriles). In addition, some 294,000 Japanese had crossed from North into South Korea and had been repatriated from there, although this movement received no official sanction.17

The Occupation authorities estimated that some 751,000 Japanese remained to be repatriated from Soviet controlled areas as of 31 December 1947.18 The Soviets were exceedingly secretive about the number of deaths among

[159]

Processing Repatriates: Customs

Displaced civilians are processed at Hakata Reception Center, Kyushu.

PLATE NO. 51

Soldiers, Sailors and Displaced Civilians

[160]

internees so this figure was not necessarily accurate. To expedite repatriation from Soviet controlled areas the United States representative on the Allied Council for Japan, on 29 October 1947, offered enough shipping (including fuel to increase the rate of repatriation immediately to 131,500 persons for the first designated month, and to 160,000 per month thereafter. No Soviet answer to this offer was received. On the other hand, allegedly because climatic conditions made the use of embarkation ports in Siberia and Karafuto in winter impossible, the Soviet authorities suspended all repatriation of Japanese from December 1947 until May 1948.19

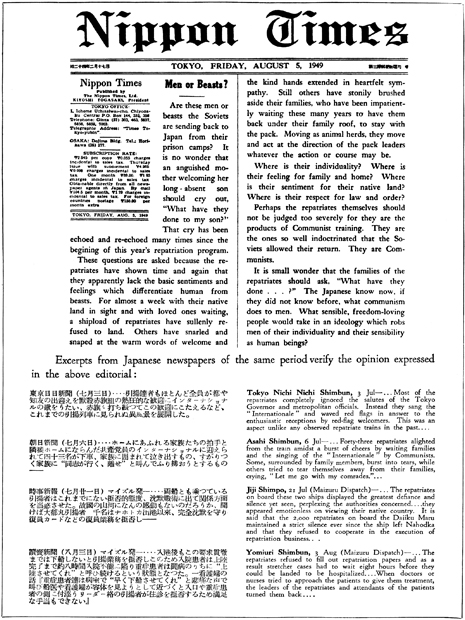

From June 1948 on, the Soviets did not fulfill their 50,000 monthly quota as specified in the agreement of 19 December 1947, in spite of General MacArthur's repeated protests; they suspended repatriation for periods of several months without any apparent justification. The repatriation of Japanese nationals still detained in Soviet areas thus evolved into a perplexing situation, involving difficulties of an entirely different type than those encountered in repatriation from other areas. Heretofore, the problems of repatriation consisted of tremendous distances, limited shipping, epidemics inherent in mass movements under crowded conditions, and integration of millions of returnees into the economic and political life of Japan; repatriation from Soviet areas, however, posed a problem in the uncompromising attitude of the Soviets. Their repatriation policy was probably predicated on the prolonged use of inexpensive Japanese labor. Interrogation of repatriates also revealed calculated indoctrination in political camps.

The Soviets completely disregarded the individual rights of approximately 469,000 Japanese who, as of 31 December 1948, were still held by them under conditions of slave labor, and made no attempt to justify their actions in the eyes of the world. Their repatriation policies should have demonstrated to the peoples of the Far East what international communism really holds for them. The issue was squarely met in General MacArthur's response to a Soviet charge that SCAP was pursuing policies in violation of the Potsdam Declaration:20

There is a deep and natural resentment throughout Japan at what is generally regarded by all Japanese as a basic disregard of human and moral values in the retention in Russia after more than three years following surrender of half a million Japanese prisoners employed under shocking conditions of forced servitude in works designed to increase the Soviet war potential. This, despite solemn undertaking entered into by the Allied Powers in Clause 9 of the Potsdam Declaration offered as a condition to the Japanese surrender, which reads as follows: "The Japanese military forces, after being completely disarmed, shall be permitted to return to their homes with the opportunity to lead peaceful and productive lives."

Evacuation of Japanese from

South Korea

In the early days of the Occupation, a high priority was given to the evacuation of Japanese nationals from Korea, south of 38 ° north latitude. In that part of Korea, there were some 600,000 Japanese nationals, the majority of whom were either military, former admin-

[161]

istrators, or technicians. In accordance with United States policy for a self-governing Korea, it was necessary to clear the way for a democratic government representative of the freely expressed will of the Korean people, by removing at the earliest date possible the influence exerted by the former Japanese officials, military and civilian.

Coincident with the surrender, the Japanese had resumed passenger ferry boat schedules between Korea and Japan. This shipping was promptly augmented by assigning short range Japanese vessels to assist in the repatriation of Japanese from Korea. By the end of September 1945 an average of 4,000 persons per day was being evacuated from South Korea. Additional shipping spaces were obtained by shuttling Japanese from Korea in LST's, which were under control of CINCPAC and were engaged in moving the U. S. XXIV Corps from Okinawa to Korea. A total of twenty LST's were employed for this purpose and returned approximately 20,000 Japanese to Japan between 12 and 16 October 1945. Similarly, 50,000 Japanese were evacuated in LST's from Saishu, a large island off the southern tip of Korea.

Because of the importance of this operation, the Japanese nationals were cleared from South Korea rapidly. All Japanese military and naval personnel, except some 2,650 retained for labor were evacuated by 21 November 1945. The sole purpose of holding a small group of Japanese was to have them aid in the repatriation of Japanese civilians, who, except for key technical advisors, were evacuated by the end of March 1946. The final contingent of the Japanese Army was returned home on 28 April 1946.

An additional repatriation burden was imposed upon the XXIV Corps21 by Japanese nationals who crossed the 38° parallel into South Korea. While this border was technically closed, many Japanese seeking repatriation evaded the road blocks and drifted into the United States zone as early as September 1945. At first, the number of Japanese from North Korea was low. During the period from 15 September 1945 to 21 March 1946, only 42,500 were evacuated via South Korea. However, from 21 May to 30 June 1946, about 10,000 Japanese per week entered the United States zone from North Korea, Manchuria. and Siberia. This number was further increased to approximately 1,500 per day by the middle of August 1946. To protect the public health of Korea, collecting stations were established along all natural avenues of approach into South Korea from the north. All Japanese were rounded up and brought to these collection centers where they were examined medically, immunized against small-pox, typhus, and cholera and dusted with DDT to prevent the introduction of epidemic diseases into South Korea. They were then evacuated through reception centers to Japan.

The repatriation program from this area was handicapped by various incidents. In January 1946 all repatriation activities were suspended for a four-day period because of a threatened general strike. Flood conditions caused another halt of activities for six weeks, from 26 June to 10 August 1946. A railroad strike in Korea caused a further delay in repatriation from 26 September to 17 October, while a cholera epidemic made it necessary to place all repatriates in quarantine prior to their evacuation. This quarantine lasted from 10 August to mid-December 1946.

Prior to 10 August 1946, SCAP controlled shipping was placed on shuttle service to Korea; subsequent to that date, however, ships were dispatched on request of XXIV Corps as processed repatriates became ready for shipment.

The clearance of the Japanese from South

[162]

Japanese repatriates arrive at Beppu, Kyushu, for processing

prior to returning to their homes.

Japanese repatriates arrive at Uraga, one of the principal

reception centers in Japan.

PLATE NO. 52

Debarkation: Beppu and Uraga

[163]

Korea was accomplished more expeditiously and completely than from any other area. Approximately 592,000 were evacuated from the beginning of the program until 31 December 1946.22

In September 1945 the Japanese reported that approximately 1,356,400 Koreans were located in Japan. The policy concerning repatriation of Koreans provided that they should be treated as liberated people insofar as military security permitted. Those desirous of repatriation, who were not being held as war criminals or for security reasons, would be returned to their homeland as soon as practicable. However, since they had been Japanese subjects, they could, at SCAP's discretion, be treated as enemy nationals and, if circumstances so warranted, be forcibly repatriated. In essence, all Koreans in Japan were given the opportunity to be repatriated, provided they had not been in active support of the Fascist governments or guilty of distributing propaganda. Those in the latter category were repatriated regardless of their desires.

Initially, Koreans flocked to repatriation ports in southern Honshu and in Kyushu in uncontrolled movements, thereby causing a serious health menace and congestion in these port areas. Since regularly scheduled ships were repatriating Japanese from Korea at the outset of the Occupation, these ships were used to repatriate Koreans on the return voyage.23

The shipping assigned to repatriate Koreans could not evacuate them fast enough to alleviate the overcrowded conditions in reception centers. This situation was eased when United States and Japanese-manned LST's, used to repatriate Japanese from northern China, on their return trip were utilized to transport Koreans.

During the period from 6 January to 17 February 1946, the average daily rate of Koreans being transported dropped to 3,000, and the Japanese Government reported that its job of inducing Koreans to move to reception centers had become increasingly difficult. This slowing down of repatriation to South Korea was attributed to the confused political situation which existed in Korea, housing shortages, widespread unemployment, general lack of organized agencies in Korea to aid repatriates, and economic conditions which were reportedly much poorer in comparison with those in Japan. The limitation on the amount of money and baggage that could be taken out of Japan especially warranted serious consideration on the part of those Koreans who had been established in Japan for a long time.

In order to solve the problem so that the Occupation forces could discharge the implied obligation to repatriate Koreans from Japan within a reasonable period of time, it was necessary to determine the number of Koreans in Japan who were desirous of repatriation, establish a plan for their evacuation by a definite date, and impose a forfeiture feature upon those who would not move according to plan.

As a result of this plan, on 17 February 1946, the Japanese Government was directed to conduct a registration of all Koreans in Japan to determine their desires concerning repatriation.24 The Koreans were told at the time of

[164]

registration that if they did not request repatriation, they forfeited this privilege until regular commercial facilities were available. At the same time, those who indicated they desired repatriation, but refused to move according to plan set up by the Japanese Government, also forfeited this privilege. A deadline date of 30 September 1946 was established for repatriation of Koreans from Japan. Application of this forfeiture proviso was not arbitrarily enforced, however; such cases were subject to review and when circumstances warranted, provision was made for later repatriation.

The initial policy for repatriation had been to return Koreans from north of 38° via South Korea. This became such a burden on the railroads and the economy of South Korea that it was decided to suspend movement of Koreans to North Korea until such time as they could be returned directly to their homes.

During June 1946 heavy rains and floods disrupted rail and highway communications from the major ports to the interior and damaged crops and buildings. By the end of the month the damage to communications was severe enough to cause repatriation activities to be discontinued. Although the Commanding General, USAFIK, requested that the temporary suspension remain in effect until 30 November, General MacArthur, considering the political repercussion that could result if Koreans were prohibited from returning to their homeland, lifted the suspension on 10 August 1946 and repatriation was resumed. As a result, the date for completing the program of returning Koreans to South Korea was set at 15 November 1946. Another stoppage of repatriation was due to a railway strike in Korea during the period 26 September to 17 October. This unexpected delay changed the estimated date for completion of the program to the end of December.

In September 1946, as an added incentive for Koreans in Japan to return to Korea, provision was made whereby each Korean family was allowed to ship home 500 pounds of household goods, and 4,000 pounds of tools and handicraft equipment. This allowance was in addition to personal belongings which they carried with them. Provision was also made for Koreans who had already been repatriated to have their tools and handicraft equipment left behind in Japan shipped to them.

During September 1945 illegal traffic between Korea and Japan began flourishing by means of small unregistered ships. Until May 1946 unauthorized persons smuggled by these ships (mostly Koreans) were no serious threat to the health or economy of either country. Late in the same month, however, South Korea suffered an epidemic of cholera. The entry into Japan of unauthorized persons consequently constituted a grave danger to public health, since the illegal entrants were not processed through any quarantine ports. To stop this traffic, vigorous patrol measures were undertaken by units of the U. S. and British Navies, the Allied Occupation forces, and the Japanese Government. Those illegal ships which were apprehended were impounded and the passengers and crews placed in quarantine. After this isolation terminated, the Koreans were returned to their country under guard.

From August to the end of December 1946, some 15,400 Koreans, trying to gain illegal entrance into Japan, were apprehended and returned to Korea.25 The majority of those, it was discovered, were former repatriates who were returning to resume residence in Japan.

By the end of December 1946 a total of approximately 929,800 Koreans had been re-

[165]

patriated from Japan, excluding the illegal entrants.26 There remained some 5,570 who were eligible for repatriation and whose return was scheduled during the early part of 1947. By May 1947 repatriation of Koreans was substantially completed.

Evacuation of the 171,000 Japanese and other nationals dispersed throughout the many islands of the Japanese defensive system in the Pacific27 presented one of the more difficult problems of repatriation from United States controlled areas. Personnel and shipping shortages delayed the start of the operation, but within a month after V-J Day, movement of Japanese, Ryukyuans, Koreans, Formosans, and Chinese was well under way.28 A few individuals had requested and obtained authority to remain because of past residence in these areas for over ten years.

By September 1945 Japanese shipping of a total passenger capacity of 18,000 was allocated to the clearance of these areas. This shipping was augmented by a number of small American manned ships which had been operating in the Pacific Ocean Area. In the second month of 1946 those United States ships that were designated for use as SCAJAP controlled, Japanese manned repatriation ships sailed for Japan with full loads.

During the period 15-17 January 1946, a conference was held in Tokyo by representatives of all commanders concerned with repatriation in order to establish standard operating procedures. It was agreed that repatriation of Japanese nationals would be suspended until July 1946, except for ineffectives; repatriation of remaining Formosans, Koreans and Chinese would be continued under existing arrangements; repatriation of other nationals (of Indonesia, Malaya, Manchuria and the Celebes would be handled separately in each case. As a result of this conference, processing of repatriates was expedited, operation of shipping facilitated, and additional passenger comforts made possible. The areas where repatriates would be processed and refueling ports were decided upon. The commander of the Marianas area at Guam was made responsible for onward routing and supply of repatriation vessels while within the limits of the Pacific Ocean Area. During the winter months, repatriation ships were stocked from United States sources with blankets and warm clothing for the prospective passengers. This equipment, the cost of which was charged against reparations, was later collected at debarkation ports in Japan. The articles, after being dyed and marked, were further distributed by the Japanese Government for relief purposes. Eventually, customs processing procedures established at the conference were strictly applied when it was found that many PW's were returning from the Pacific Ocean Area to Japan with large quantities of newly-purchased luxury items of United States manufacture, wrist watches, fountain pens and silk stockings; all items in excess of amounts normally required by individuals were confiscated.

Though hampered by the low operational efficiency (about 50 percent of the Japanese shipping and occasional supply shortages, repatriation schedules set in September were maintained with minor interruptions and negligible loss of life through mid-March 1946. Since by that time 163,000 had been repatriated

[166]

Customs search for contraband and weapons.

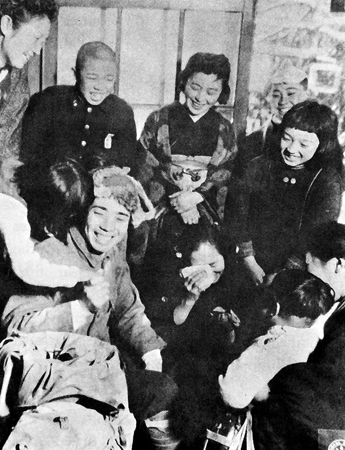

Repatriate from Soviet territory returns to his family.

PLATE NO. 53

From Port to Home

[167]

and the remaining 7,000 were being utilized as labor, shipping schedules were curtailed except for evacuation of those no longer needed for labor.

On 8 August 1946 General MacArthur requested CINCPAC to return all remaining Japanese prisoners of war and surrendered personnel in three monthly increments starting in October 1946, so that the target date of 31 December 1946 for the completion of the over-all repatriation program could be met. CINCPAC agreed to the plan, and through its implementation, the task of repatriation from the Pacific Ocean Area was completed ahead of schedule when on 24 December 1949 the Japanese ex-destroyer Sugi with her last load of repatriates arrived at Uraga, Japan.29

When Phase Three of the repatriation program ended, a total of approximately 130,800 persons had been returned to Japan and 40,700 returned directly to Formosa, the Ryukyus, China and Korea.30

Extensive United States base installations which existed in the Philippine Islands facilitated control and evacuation of the 152,400 repatriates.31 Principal concentrations were on Luzon, Mindanao, and Leyte. The initial proportional share of Japanese repatriation shipping allotted to the Philippine Islands amounted to only 12,000 spaces but was augmented by routing supply ships returning empty to the United States from the Philippine Islands via Japan. On 7 October 1945 the first Japanese ships, modified to transport repatriates, arrived in the Philippine Islands. Both United States and Japanese ships were supplied with additional life-saving equipment, overside latrines, and food and water stores. During cold weather, blankets and warm clothing, furnished by the United States, were placed upon all ships engaged in repatriation; the passengers were allowed to keep the clothing issued to them.

Until February 1946, with slight modifications, evacuation of Japanese proceeded according to plan. On 24 December 1945 General MacArthur directed the Commanding General, AFWESPAC, to route shipping on the Japan shuttle via Takao, Formosa, to permit return of approximately 12,000 Formosans from the Philippines and subsequent transport of Japanese in Formosa to Japan. On the same date movement of approximately 1,400 Koreans and 53,000 Chinese direct to their respective homelands was also authorized.

Suspension of repatriation in January affected approximately 43,600 Japanese PW's who were required for maintenance and repair of essential installations in the Philippine Islands. Evacuation of sick and other ineffectives from this group in American cargo ships continued until May 1946. At this time, authority to utilize United States shipping was withdrawn and limited SCAJAP Japanese shipping was substituted.

When General MacArthur decided that all United States controlled areas were to be cleared by the end of 1946, a plan was set up to clear the remaining Japanese from the Philippine Islands. Shipping was prepared to remove the Japanese from camps located near Tacloban, San Fernando, and Manila. Approximately equal monthly increments were

[168]

evacuated during October, November, and December 1946. By the end of the year only 665 Japanese remained in the Philippine Islands. They were detained there either as witnesses or as suspected criminals for the war crimes trials. There was also an undetermined but fast dwindling number, probably not exceeding 500, hiding in the mountains.

Although the Ryukyus, because of their proximity to Japan, should have presented an easy repatriation problem, such was not the case. The Ryukyus, especially Okinawa island, had been ravaged by invasion and rehabilitation proceeded slowly. As late as the spring of 1946 there ware still 130,000 residents homeless on Okinawa itself. Never self-supporting, the food situation on Okinawa was further aggravated by the loss of many acres of arable land taken over for base installations.

Initially, military government in the Ryukyus south of 30° north latitude was exercised by CINCPAC. As such, that headquarters was responsible for the return of some 69,200 Japanese military personnel.32 A ferry service was established to the Ryukyus in October 1945 to transport only the Japanese military. This was supplemented almost immediately by the assignment of short range Japanese shipping, and further augmented by empty United States cargo ships returning home via Japan.

Japanese military were returned to Japan by the beginning of 1946, with the exception of 14,000 whose return was temporarily suspended until the last quarter of the year. During this period their services were utilized to repair war damaged facilities and to assist the native population to return to their former homes.

The return of displaced Ryukyuans was not so easily achieved. There were approximately 160,000 Ryukyuans in Japan who had been hurriedly evacuated from their homes just prior to the invasion by the United States forces. They had been permitted to carry with them little in the way of baggage, clothing or funds. Their situation in Japan rapidly became worse from a social and economic standpoint. It was therefore to the interest of General MacArthur's headquarters to return them to their former homes.

Early agreements with CINCPAC were reached under which repatriates from Japan destined for localities in the Ryukyus other than Okinawa would be accepted. Consequently, Ryukyuans were loaded on shuttle ships which were returning Japanese. The program for the return of Okinawans moved slowly. Repeated representations to CINCPAC to initiate this program were unproductive. CINCPAC, with considerable justification, refused to accept the Okinawans on the grounds that food and shelter were not available locally to support the added increase in population. When the responsibility for military government of the Ryukyus was transferred from the Navy to the Army on 1 July 1946, the matter was reconsidered. General MacArthur was most anxious to evacuate the Ryukyuans because they were a serious relief problem in Japan. It was for this reason he directed that they be repatriated without further delay and that necessary food and shelter be provided for them from Japanese and United States resources. A conference was called in Tokyo on 22 July, at which time the representatives of AFWESPAC and SCAP agreed upon a plan for the repatriation of all Ryukyuans in Japan who were willing to return home.

This plan, published late in July, was quite complicated because of conditions in the Ryukyus. It provided that repatriation would begin on 5 August 1946; repatriates would be

[169]

segregated in Japan and loaded on ships according to destination;33 further distribution in the Ryukyus would be made by small boats; and all repatriates would undergo a six-day quarantine period before departing. The rate of repatriation to Okinawa was established at 4,000 per week until 26 September, after that at 8,000 per week until the program was completed. Incorporated in the plan were provisions for the return of approximately 140,400 Ryukyuans from Japan.34 Careful supervision smoothed out the complicated mechanics of the entire operation.

'The military government authorities in the Ryukyus were faced not only with the task of receiving the repatriates but of transporting them to their homes and providing shelter and food for them. Inter-island transportation was provided by small native and United States craft, including six LST's made available by SCAP. Overland transportation was furnished from the meager resources of the military government authorities in the Ryukyus.

Houses for the incoming repatriates were built of lumber, with cement and nails furnished by SCAP. Over 17,000 simple dwellings were constructed; the frames were of wood while the roofs and walls were of thatch. Almost 10,000 pyramidal tents were used to provide for immediate needs.35

All remaining Japanese prisoners of war and surrendered personnel retained in the Ryukyus for labor were returned to Japan in three monthly increments starting in October 1946. The program was completed by the end of the year.

Because of the large numbers involved, repatriation of over 3,000,000 Japanese and other nationals from China and adjoining areas became another of the more difficult and pressing tasks on V-J Day. On that date, this mass of humanity, consisting of approximately equal numbers of military and civilian personnel, was reported to be geographically situated as follows:36

Area |

Numbers |

China |

1,501,200 |

Manchuria |

1,105,850 |

Formosa |

479,050 |

North Indo-China |

32,000 |

Hong Kong |

19,200 |

Two factors made necessary the assignment of a high priority to repatriation from China and adjoining areas. First, it was United States policy to assist in the establishment of a sound central government in China. This objective could not be accomplished as long as the security of China was threatened by the presence of large numbers of Japanese troops. Second, large numbers of Japanese were located in areas of conflicting interests of the French Government, Viet Nam, Chinese Nationalists, and Chinese Communists, making early evacuation of these groups imperative to prevent their being used as pawns in the various political disputes. These factors combined with extremely poor interior transportation and communication facilities in war-ravaged China made even the concentration of repatriates at evacuation ports a formidable task.

[170]

Japanese repatriates aboard ship.

Repatriates are admitted to the Matsuasa Restaurant at Omori.

PLATE NO. 54

Flotsam of War: Displaced Civilians

[171]

Full appreciation of the repatriation problem in Chinese areas is possible only through knowledge of the role played by the U. S. forces stationed in China. Upon the cessation of hostilities with Japan, the U. S. Joint Chiefs of Staff assigned the task of advising and assisting the Chinese in repatriation of Japanese to the U. S. Army Forces, China Theater, (later re-designated as the U. S. Army Forces, China). When this headquarters was discontinued, its duties were transferred to the Peiping Headquarters Group, acting mainly in an advisory capacity to the Chinese Government, General MacArthur, and the U. S. Navy in China. Of the coordination tasks assigned to the various U. S. Army forces in China, the maintenance of effective liaison with the Chinese authorities was the most difficult. Successful liaison was accomplished only through patient, persistent efforts.

No time was lost in getting the program under way. Under an interim plan implemented early in October 1945, the first shipping was used in evacuating Japanese situated near Shanghai and Tangku. Concurrently, a more complete organization for repatriation was developed by SCAP through a series of conferences, in which the Chinese and United States ground and naval commanders in China were integrated into the SCAP repatriation system. As in the case of other areas, many of the ships and direction of the program came from the United States. The Chinese Government was made responsible for the delivery of repatriates to the ports, their medical and other processing and their correct loading aboard the SCAP controlled ships according to the monthly quotas scheduled; however, supervision of this loading and processing was also made a responsibility of the United States forces in China. This was accomplished by sending American liaison teams, which included communications and medical personnel, to the main evacuation ports in China. These teams solved the communication problem and greatly reduced the amount of epidemic diseases carried to Japan.

After two previous conferences (representatives came from General MacArthur's headquarters, Navy Command in the Pacific, and United States Forces in China) had resulted in establishment of general policies regarding ships, shipping routes, and embarkation rates,37 a third one was called for 15-17 January 1946 in Tokyo. At this time, all United States commands in the Pacific and Far East (except AFMIDPAC) were integrated into a theater-wide organization for repatriation. Operational procedures and schedules were developed with emphasis on the plan for evacuation of China. The results of this conference were published as "Agreements Reached at Conference on Repatriation 15-17 January 1946, Tokyo, Japan." This document governed repatriation procedures from that time on.

At the conference, daily evacuation rates

[172]

were set as follows: North China, 4,000; Central China and Formosa, 16,000; South China and North French Indo-China, 15,000; an aggregate of 1,050,000 per month. These rates were based upon use of United States shipping for Chinese repatriation.38

Within two months of the 17 January conference, repatriation from Chinese areas was limited only by the numbers made available at evacuation ports. With the exception of stragglers, war criminals, and 28,000 civilian technicians retained by the Chinese Nationalist Government, the greater part of China was cleared by June 1946.39

South China was cleared by 25 April 1946, repatriates being removed through the principal ports of Canton, Amoy, and Swatow. Hainan Island was cleared without incident in March. Also included in South China repatriation was that part of French Indo-China north of 16° north latitude. Although operational control of this area was being transferred from the Chinese Nationalists to the French Government concurrently with evacuation of Japanese, the area was cleared during May 1946 without difficulty other than a major dislocation of shipping due to a cholera epidemic.

The Hong Kong area of South China, under British control, was cleared early in May through combined use of Japanese manned United States repatriation ships and British cargo vessels. The British, however, retained about 1,300 Japanese for labor until December 1946, when this number was reduced to 268. These were subsequently repatriated.

Central China evacuation schedules were interrupted by an outbreak of smallpox in Shanghai in April, a typhus epidemic in May, and cholera in June. On the Shanghai-Sasebo shuttle, the only major shipping accident of the entire repatriation program occurred on 22 January 1946 when the Enoshima Maru, carrying 4,300 Japanese civilians, struck a free mine and sank slowly, fifty miles out of Shanghai; through the assistance of another repatriation vessel, all but seventy-seven of the passengers and crew were saved. Except for stragglers, Central China was cleared in July 1946.

Repatriation from Formosa was delayed until early December 1945, when the Chinese Government landed troops and took control of the island. The northern half of Formosa was cleared through Kiirun and the southern portion through Takao. The Japanese located in a comparatively inaccessible strip on the east coast were removed through Karenko by small draft vessels loaded by lighters. Cholera once again slowed the program. However, except for some 24,000 technicians required for operation of essential public facilities, Formosa was cleared by 15 April 1946. By the end of 1946 those retained by the Chinese had been reduced to 11,000 through use of both Chinese and SCAJAP shipping.

[173]

North China repatriation, though affected by the Chinese Communist and Nationalist military operations which occasionally blocked the ports of Tangku and Tsingtao, was completed late in May 1946. During periods of internal Chinese strife and strained relations in North China, repatriation was expedited through efforts of the U. S. Marines.

By comparison with the rest of China, repatriation from Manchuria proved the most difficult. Though the Chinese Communists had agreed upon the desirability of repatriation of Japanese, few efforts were made by them to cooperate until the fall of 1946. Though never definitely ascertained, it was estimated that 612,000 Japanese were concentrated in the Mukden-Hulutao area, 387,000 near Changchun in central Manchuria, 310,000 in the vicinity of Harbin in north Manchuria, and 250,000 in the Dairen-Port Arthur area.40

After the Nationalist forces had advanced well beyond Mukden, repatriation began in April through the port of Hulutao. The initial evacuation rate of 3,000 daily was increased to 7,5 00 daily by July. Peak loads were transported to Japan during the summer months except for minor interruptions because of a flood in the interior and another delay of three weeks during August because of cholera. During this period every effort was made to push repatriation in order to complete the program in Manchuria before the port of Hulutao was frozen in. Out of the 1,300,000 believed to be in the area, only 469,000 Japanese, mostly civilians, had been repatriated by mid-August 1946.

During the summer repeated attempts were made to secure evacuation of Japanese from central and north Manchuria under Chinese Communist control. Early in September evacuation from Chinese Communist areas was at last made possible; the outflow from Hulutao increased to 10,000-15,000 daily during the next two months. By the end of October all Japanese had been evacuated from Manchuria except the 250,000 under Soviet control and some 68,000 unaccounted for in the interior.41

A straggler program was set up in September 1946 to accomplish repatriation of scattered groups of Japanese at Canton, Hainan, Shanghai, and Formosa. Included in this program were the 24,000 Japanese technicians and their dependents held in Formosa. They were initially expected to be transported to Japan by Chinese ships. Of this group SCAP actually provided transportation for all but 3,000 of the 13,000 repatriated by the end of 1946.42 When in December 1946 repatriation shipping facilities were further reduced, SCAP established a policy to provide transportation for only those straggler groups of more than 200 persons.

Repatriation of Koreans from China to Korea was started late in January because of military expediency, medical considerations, and availability of surplus repatriation shipping from China shuttles. Because of the limited port facilities in Korea, the traffic was divided between the ports of Inchon and Fusan.

By mid-March 1946 the situation of remaining Koreans in north and central China awaiting repatriation had so deteriorated that their early repatriation was imperative. Consequently, schedules were advanced and this repatriation was completed in June 1946.

During the repatriation program from China, cholera, typhus, and smallpox epidemics origi-

[174]

Orderly embarkation under U.S. Navy.

Aboard an LST at Tsingtao, China.

PLATE NO. 55

Repatriates from China and Manchuria.

[175]

nating there during the spring and summer of 1946 had a tremendous effect on reception facilities in Japan. Shipping and passengers tied up in the quarantine ports of Uraga, Hakata, and Sasebo at times totalled over eighty vessels with more than 150,000 repatriates aboard. Control of quarantine ports and maintenance of nearly normal evacuation rates from all areas during the spring and summer of 1946 required a high degree of rapid and effective coordination of all United States and Japanese agencies; with the institution of adequate measures to limit the return of unauthorized Koreans to Japan in small craft, even minor outbreaks of these diseases in Japan were eliminated.

Mass repatriation from Chinese areas was completed by the end of December 1946, with some 3,101,700 Japanese returned home.43

The problem of repatriating Japanese stragglers in Manchuria still existed, however; in a G-3 report of 29 April 1949 it was estimated that there were slightly more than 60,000 Japanese still in the Chinese Communist controlled areas of Manchuria.44 Their repatriation could be accomplished only if they were able to infiltrate into Nationalist areas and then be transported to ports on the coast. General MacArthur was prepared to send shipping whenever there were sufficient number of Japanese available for repatriation. (Plate No. 56)

In September 1945 approximately 710,670 Japanese awaited repatriation from areas under control of SACSEA.45 The immediate problem involved disarming the Japanese and assembling them in areas near appropriate ports of embarkation. According to British policies regarding Japanese civilians, those who entered British or other Allied areas after the outbreak of the war were to be repatriated. Those individuals, nevertheless, who had either resided in such areas prior to the outbreak of war or were not objected to by territorial authorities, did not have to be returned to Japan.

It was agreed between SACSEA and SCAP that useable Japanese shipping recovered in Southeast Asia areas46 would be utilized, under United States control, in transporting repatriates from Southeast Asia ports directly to Japan. In addition, such other Japanese shipping as could be made available would also be allocated to Southeast Asia repatriation.

Because of the limited number of ships and the distance involved only 34,300 Japanese had been repatriated from SACSEA by 21 April 1946.47 Early in 1946 it was realized that four or five years would be required to complete the Southeast Asia repatriation program with shipping then available. This situation was unacceptable to both British and United States authorities, and various sources for procurement of additional shipping were investigated. Previously, some 106 Liberties and 85 LST's had been made available to SCAP from United States resources to accelerate repatriation from China. By the end of March 1946 it was foreseen that some of these ships would be in excess of the repatriation requirements of China

[176]

PLATE NO. 56

Repatriation Shipping: October 1945-September 1945

[177]

and could be used profitably in the evacuation of Japanese from Southeast Asia. Authority was therefore obtained from the U. S. Joint Chiefs of Staff early in April to employ United States owned shipping in this manner on a charter free basis until 30 June 1946. The British agreed to make available operating supplies such as fuel, emergency victuals and stores in kind, that were required for SCAP shipping used in repatriation service from SEA areas. After 30 June 1946 the British were obliged to pay charter hire for United States owned ships used in repatriation from their areas.48

SACSEA established priorities for clearing areas in the following order: North Borneo, south French Indo-China, outer Netherlands East Indies, Siam, Malaya, Java, Sumatra and the inner Netherlands East Indies, and Burma. A plan for repatriating Formosans and Koreans directly to their home lands was integrated into the program. Similarly, provisions were also made for the movement of sick evacuees by SCAP controlled hospital shipping. Two British hospital ships, the Gerusalemme and the Amapoora, assisted by returning one shipment each of invalid Japanese.

In July 1946 SCAP set 31 December 1946 as the target date for the completion of the repatriation program. The British, however, contemplated retaining some 90,000 Japanese prisoners of war and surrendered personnel for labor during 1947.

Representatives of SCAP and SACSEA conferred at Tokyo from 11 to 17 June 1946, consummating agreements which covered immediate shipping requirements, disposition of shipping recovered in Southeast Asia, and details of fuel supply and charter hire. In short, it was agreed that SCAP would supply the necessary ships to repatriate such Japanese as the British would agree to release through August 1946, but would make no commitments of repatriation shipping after that time. The British on their part agreed to fuel all repatriation ships on a round trip basis and to pay charter hire for the use of United States owned ships utilized. Further agreements were reached whereby three Japanese warships would be placed at the disposal of SCAP on their last repatriation trip to Japan, and that Japanese ships other than warships recovered in Southeast Asia would be returned to SACSEA upon completion of the program. These agreements were approved by SCAP and SACSEA. By the middle of August provisions had been made for the return of virtually all repatriates from Southeast Asia areas, except those retained for labor.

General MacArthur did not agree to the postponement of repatriation and made statements to this effect to the U. S. War Department and to SACSEA. The British continued to retain 82,000 Japanese in areas under their control and in addition turned over 13,500 to the Netherlands East Indies (NEI) Government.

In November 1946 SCAP made a final offer to SACSEA to evacuate all Japanese repatriates from Southeast Asia to Japan, and in a separate action endeavored to dispose of the ships in accordance with the June agreement. The British did not accept the offer and, in addition, expressed a desire to retain all Japanese ships and their crews seized in Southeast Asia. The last Japanese repatriates were evacuated from that area in October 1947, except for those retained for war crimes trials.49

[178]

In December 1946 the Netherlands Government agreed to return the 13,500 Japanese held under their control. Repatriation from the Netherlands East Indies was completed in May 1947, but for those Japanese who were held as witnesses or defendants for war crimes trials.50

Following Japan's surrender, the respective areas of responsibility of Australian Military Forces (AMF) and SACSEA were not clearly delineated. During autumn 1945 and prior to the actual inauguration of repatriation from AMF areas, successive phasing resulted in the establishment of AMF control of the Australian mainland, New Guinea east of 142° east longitude, and the Admiralty, Bismarck (New Britain, New Ireland), and Solomon Islands. Approximately 138,700 Japanese awaited repatriation in these areas.51

By agreement between AMF and SCAP, some Japanese shipping (including warships) capable of making the long voyage, was dispatched in late 1945. Because many evacuees in AMF areas were sick or disabled, a large amount of hospital shipping was provided by SCAP. By the first of March 1946 some 31,900 Japanese had been repatriated.52

Early in April authority was obtained to utilize Japanese manned United States Liberty ships to augment the seventeen Japanese ships then engaged in repatriation from AMF areas. The Australian Government agreed to make available operating supplies in kind as required for SCAP shipping when used in such repatriation service. Consequently, eight Liberties were assigned to the clearance of AMF areas. This number was eventually increased to sixteen. By early April, the Australian mainland had been cleared of Japanese. Only a few were held in connection with war crimes activities.

In April and May the program was nearing completion. Shipping was kept flowing into Rabaul to the limit of the port's ability to process and load repatriates. By 13 June 1946 all areas controlled by AMF had been cleared of Japanese, Korean and Formosan repatriates. Eight hundred Japanese held for war crimes or judicial investigation were returned to Japan in November, leaving a balance of 816 as of 31 December 1946.53 The area was completely cleared during the following year.

Incomplete reports available indicated that there were approximately 1,617,650 Japanese in areas controlled by the U.S.S.R. at the conclusion of hostilities.54

Following instructions from the U. S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, appropriate representations were made in October 1945 to the Soviet Government requesting that it turn over to SCAP ships recovered in areas under Soviet control to be used for repatriation and to support a minimum economy in Japan. No replies to this or other radios of a similar nature were received until 12 April 1946. It was only then that the U.S.S.R. Member of the Allied Council for Japan reported the amount of shipping recovered from the Japanese by the Soviet Government but stated that none was suitable for repatriation purposes.

On a local level, the respective military

[179]

Japanese repatriate children aboard ship.

Repatriate from Soviet territory is met by his family.

PLATE NO. 57

Repatriates from Soviet Territory

[180]

commanders exercising authority in North and South Korea conferred in January 1946, on the question of repatriating Japanese nationals located in North Korea to Japan via South Korea. The main difficulty involved was the supply of fuel for rail transportation, but repatriation of Japanese from North Korea actually adjusted itself while these and later conferences were in progress. Although there was no legal repatriation traffic across the 38° border in Korea, a total of some 292,800 Japanese filtered through and were repatriated to Japan through South Korea. When negotiations were finally consummated it was found that there were less than 15,000 Japanese to be repatriated from North Korea.55

During the period between October 1945 and April 1946, sporadic attempts to effect repatriation of isolated groups from restricted areas under Soviet control were made without success. In April 1946 SCAP forwarded proposals for mutual repatriation between Japan and North Korea to the Soviet authorities. The proposals contained in this document were patterned on the existing agreements made by SCAP with other Allied governments and commands. In May the Soviet Government returned the document suggesting certain changes to the proposed agreements. As a result of this communication, a conference was held in Tokyo the following month. No agreement was reached inasmuch as the Soviet Government requested preferential treatment be given to Koreans in Japan who were to be returned to North Korea, but was not willing to furnish any fuel or other supplies for repatriation ships.

A further conference between representatives of SCAP and the Soviet Government was held in Tokyo in July 1946. SCAP proposed that agreements be reached regarding repatriation of Japanese from northern Korea and the Dairen-Port Arthur area, Manchuria. Since the Soviet representative was not authorized to discuss the return of Japanese prisoners of war and surrendered personnel from those areas, the conference was adjourned. To support SCAP's position, the basic authority contained in the Potsdam Declaration was used, wherein the Allied Powers announced their intention to permit the Japanese military to return to Japan; hence the repatriation of civilians was secondary, being conducted primarily for humanitarian reasons. The entire matter of repatriation from Soviet controlled areas was then presented to the War Department, requesting that arrangements be conducted on a governmental level.56

In the latter part of September 1946 Soviet authorities advised SCAP of their willingness to undertake the repatriation of Japanese PW's and civilians from the U.S.S.R. and territories under its control; repatriation could begin the following month. By 3 October 1946 SCAP had forwarded proposals for repatriation of Japanese nationals from the Soviet and Soviet controlled areas. The proposals were similar to those sent to the Soviet authorities in April. In an attempt to overcome points of difference encountered in the June conference, the plan contemplated the use of Japanese coal burning ships. Japanese oil burning ships and United States owned ships were to be used for repatriation only when payment for fuel and charter hire by U.S.S.R. had been arranged on a governmental level.

From 14 October until mid-December 1946, a series of thirteen conferences were held in an attempt to reconcile points of difference: the

[181]

And a new life.

PLATE NO. 58

Return to Home and a New Life

[182]