CHAPTER IX

AIR AND NAVY COMPONENTS

Part I-Far East Air Forces Initial Operations

While the world's chancelleries deliberated the fate of the Japanese Empire, the Fifth and Seventh U. S. Air Forces continued to bomb Japan's lines of communication, industrial areas, shipping, aircraft, and various other military installations. After the Japanese Government notified the Allies of its acceptance of the peace terms, activity of these Air Forces was limited to reconnaissance, surveillance, and photographic missions. Meanwhile, during the interim which existed while arrangements were made for the formal capitulation, there were numerous interceptions of U. S. reconnaissance aircraft, indicating that the Kamikaze indoctrination had some effect. For this reason, American air activity over Japanese territory had to be temporarily suspended.1

From iq August, when the Japanese Surrender Delegation flew from Atsugi to Ie-shima and was then escorted to Manila by American aircraft, until 30 August when General MacArthur landed at Atsugi, increased armed surveillance missions were flown over Japan by B-29's to insure that the surrender terms would be kept. This tremendous display of air power throughout Japan left no doubt of defeat in the minds of the Japanese.2

As rapidly as the advance party of the Far East Air Forces (FEAF) completed reconnaissance of the Tokyo airfields, established communications facilities, and set up an air traffic control center, the Fifth Air Force brought in its tactical units.

By the end of August FEAF air units were concentrated on Okinawa, preparing to deploy to the mainland of Japan. A mass shuttle to Atsugi airfield enabled the 11th Airborne Division to complete a speedy occupation of the Yokohama area on 30/31 August. All available troop carrier transport of FEAF was utilized as well as "Skytrains" and "Sky-masters" of the Air Transport Command (ATC). Advance headquarters of GHQ, USAFPAC, Eighth Army, and FEAF were airlifted to Japan. Repatriated Allied prisoners of war and civilian internees in need of hospitalization were evacuated on the return flights of these planes to Okinawa and the Philippines.

To provide staging and servicing facilities for transport and transient aircraft, a small task force composed of service personnel and equipment was established in September in the Kanoya area, Kyushu. Considerable air traffic was staged through that area due to the relatively great distances from Okinawa and the Philippines to Japan. Subsequently, Fifth Air Force combat units with appropriate service elements occupied objective locations

[268]

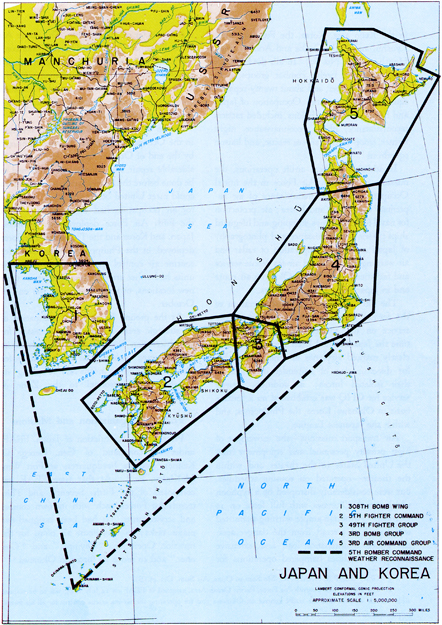

PLATE NO. 87

Fifth U.S. Air Force Zones of Responsibility, 1945-1947

[269]

in the Keijo area, Korea, the Fukuoka area, Kyushu, and in the Osaka and Aomori areas, Honshu. (Plate No. 87) In all, the Fifth Air Force provided twelve combat groups, both fighter and bomber, and about twenty separate squadrons for the initial Occupation of Japan and Korea. These echelons included tactical reconnaissance, photo reconnaissance, night fighter, troop carrier, air-sea rescue, and liaison squadrons.

In addition to these airlift operations, the missions of the Fifth Air Force in the Initial Occupation included maintenance of air supremacy over Japan and Korea; air protection for naval forces, convoys, shipping, and lifeguard ships; aerial reconnaissance and photography of Japan and Korea; operation of radar and air warning services; and air-sea rescue service and facilities on the Tokyo-Okinawa air route and in Japanese and Korean waters.

The Fifth Air Force assumed operation of the former Japanese Government air courier service on 10 October 1945. Prior to that time the Japanese had been permitted to use clearly marked airplanes in scheduled flights for dissemination of surrender directives to their isolated forces; in addition, courier service for GHQ was established on a routine basis to Okinawa, Korea, the Philippines, and within the Japanese Empire.

Air transport missions-the movement of high priority personnel and equipment from the United States to the theater and within the theater-operated on routine schedules, but were considerably disrupted by a typhoon which struck Okinawa with full force on 11 October. Although ample warning permitted withdrawal of aircraft from the danger area, the added maintenance load and extensive damage to facilities hampered operations for the remainder of the month. The Army Air Force Weather Control at Okinawa was completely demolished. When the storm delayed supplies and destroyed equipment in the Okinawa area, B-29's had to fly relief missions comparable to their prisoner of war supply drops during September.3

As on the ground and sea, the air situation in the Occupation plan had become stabilized by the end of October 1945 Although considerable repair and construction remained to be done before the former Japanese air facilities could meet United States standards, the areas for air occupation had been settled. With the Fifth Air Force deployed in Okinawa, Japan, and Korea and the Thirteenth Air Force deployed in the Philippines, preparations for routine air control were complete. All air units had either arrived, were en route to their new locations, or were loading by the end of October.

As the ground forces began occupation of all strategic areas in Japan, the necessity for air observation lessened. FEAF turned its efforts toward deploying air units to Japan for Occupation duties, meanwhile returning its "high-point" personnel to the Zone of Interior.

FEAF : Organization and Missions

Prior to the capitulation of Japan, FEAF, under the command of Gen. George C. Kenney, had its headquarters at Fort Wm. McKinley, P. I. At that time FEAF was composed of the Fifth. Seventh, and Thirteenth Air Forces, each with its own combat and service units. It had been assigned two major tasks: to coordinate air plans for the invasion Operations "Olympic" and "Coronet," and to move its forces to Okinawa.4

[270]

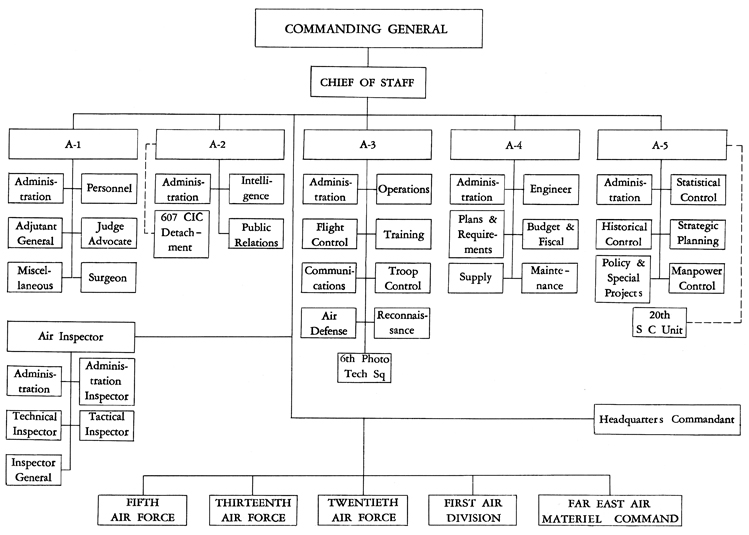

With the surrender came the task of redirecting this powerful offensive force along completely different lines.5 Practically over- night the plans and missions had to be changed, even though the organizations remained intact until it was determined that the Occupation was to be a peaceful one. Reorganization and redesignation took place on 25 December 1945, at which time the Pacific Air Command, U. S. Army, (PACUSA) was activated.6 The U. S. Army Strategic Air Force was discontinued. Its Headquarters and Headquarters Squadron, all its units, allotments, and personnel were released and assigned to PACUSA. (Plate No. 88) Under the command of General Kenney, PACUSA was assigned to U. S. Army Forces, Pacific, with its initial station at Fort Wm. McKinley and advance headquarters in Tokyo. Lt. Gen. Ennis C. Whitehead officially assumed command of PACUSA on 30 December 1945.7

Throughout the three year period following the cessation of hostilities the organization of PACUSA did not change materially. A few smaller units were activated, deactivated, or transferred in order to balance the Air Forces and keep them organized in a manner consistent with their missions. One exception was the reorganization of the supply and logistics agencies of PACUSA. At the close of the war active supply depots were operating under Far East Air Service Command(FEASC) at Townsville, Finschhafen, Biak, Leyte, Nichols Field, Guam, and Okinawa. Nichols Field, already a large depot and situated near a ready labor market, was built up rapidly and received the bulk of supplies from Townsville, Finschhafen, Biak, and Leyte. Manpower shortage made the closing of the Okinawa depot necessary in October 1946, and the Philippine Islands Treaty granted Nichols Field to the Philippine Government in mid-1947.

The designation of FEASC was changed to Pacific Air Service Command on 26 February 1946, and again on 1 January 1947 when it became Far East Air Materiel Command (FEAMCOM). On 21 January 1947 FEAMCOM moved from Fort McKinley to Fuchu, Japan.8 Two depots were under the technical control of FEAMCOM: Marianas Air Materiel Area located at Guam, and Japan Air Materiel Area located at Tachikawa, Honshu, Japan. These depots, in addition to their normal functions of supply and maintenance, had the overwhelming task of locating, identifying, classifying, inventorying, and warehousing the tremendous amount of materiel left over from the war.

Headquarters, PACUSA (Administration), arrived in Japan on 16 May 1946 from Fort McKinley, occupying joint offices with the advance echelon in downtown Tokyo.9

[271]

PLATE NO. 88

Organization of FEAF Command and Headquarters Staff, 1947

[272]

PACUSA lost one of its major air forces on 1 January 1947 when the Seventh Air Force was reassigned to CINCPAC.10 At the same time several new units were assigned to PACUSA: the Pacific Division of the Air Transport Command, the 43rd Weather Wing, and the 7th Airways and Air Communications Service Wing. All had parent units in Washington but were placed under the operational control of the Commander in Chief, Far East, who in turn delegated control to the Commanding General, PACUSA. All of these were service units vital to the proper functioning of balanced air forces, giving logistical and technical support to the tactical and administrative units of FEAF.

The title of Air Force Headquarters was again changed. On 1 January 1947 PACUSA became Far East Air Forces, U. S. Army, but with no change in assignment or organization. The final title change came in November 1947 when, as a result of the integration program of the Armed Forces, Far East Air Forces, U. S. Army, became Far East Air Forces, U. S. Air Force. FEAF remained under CINCFE, but on a parity of command with the other services. For the accomplishment of its missions, FEAF was allotted a substantial portion of the U.S. Air Force; in its designated areas of responsibility, FEAF operated and maintained a total of thirty-nine air bases and related installations involving some twenty-four airfields and airstrips.11

Maintenance of the Air Force in Japan

On V -J Day there were 300,000 Air Force officers and airmen in the Pacific Theater. Four months later 215,000 of these had departed for the United States and demobilization, leaving only 85,000 in the theater as of January 1946.12

The rapid demobilization of troops affected the essential team character of the Air Force combat units which thereafter operated at reduced strength until the flow of replacements exceeded the flow of departures for a sufficient period. On-the-job training was immediately established in all units, combining individual training with unit training; this plan had the advantage of maintaining organizational structure. In order to raise the level of technical knowledge in units, some civilian technicians were recruited from the United States. In September 1947 a FEAF-wide technical training program was established, offering over thirty courses, for the most part in specialties not then available through replacements; during the first year approximately 4,800 students were graduated. This program filled the gaps in individual training and developed unit training to a state of combat readiness unexcelled in the entire U.S. Air Force.13

[273]

PF-80 flies over rice fields near Tokyo on photographic reconnaissance mission.

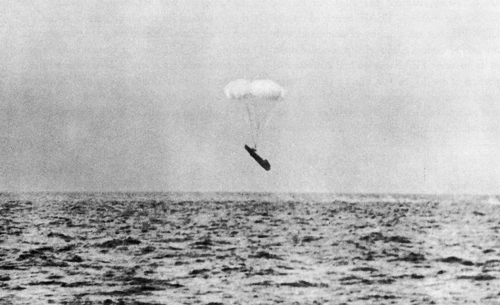

Life boat descends by parachute in air-sea rescue operations.

PLATE NO. 89

Occupation Missions-FEAF

[274]

Aerial Mapping and Other Activities

FEAF's aerial mapping program developed into an important post-war activity. Mapping squadrons flew over 100,000 miles during which they mapped or charted thousands of square miles of previously uncharted territories in the Far East. The photographic negatives resulting from aerial photography were delivered to topographic units of the Corps of Engineers, and to the Aeronautical Chart Service of the U.S. Air Force. The Engineers were responsible for technical ground control and for the actual production of maps, while the latter was responsible for the production of aeronautical charts.

Additional miscellaneous activities of FEAF included the disposal of extensive stocks of war surplus property, maintenance of base facilities, provision for maintenance and protection of aviation ammunition stores, preparation of plans for Air Force bases involved in the permanent base construction program, and establishment of a civilian manpower control to insure the efficient allocation of civilian personnel employed by FEAF.

Troop Carrier Aviation and

International Air Traffic

Both during and after the war, increased dependence was placed on Troop Carrier Aviation for the support of the armed forces. Unique logistical and administrative problems developed within the Far East Command which covered vast water areas, mountainous terrain, and small isolated islands, with climates ranging from tropical to sub-arctic. This area, extending from Hokkaido on the north to the Admiralty Islands on the south, required a fast and reliable means of communication. Suitable port facilities and sufficient shipping were not available nor, except to a limited degree in Japan, did adequate railroad and highway facilities exist.

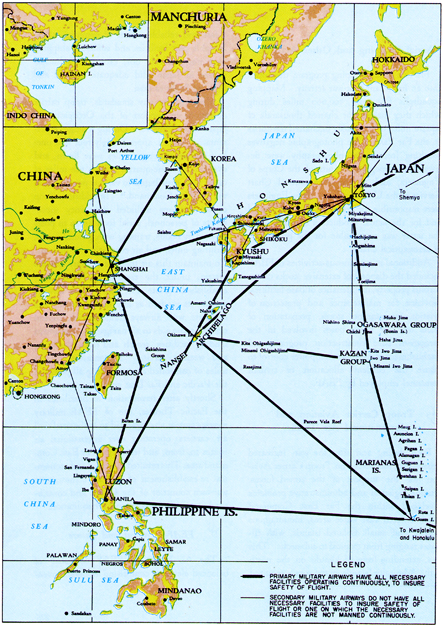

Measured by any standards, troop carrier operations in support of the Occupation of Japan were extensive. During a single representative month approximately four and one-half million passenger miles were flown, and over one and one-quarter million ton miles of cargo were distributed to various points within the Far East Command.14 In addition, troop carrier missions included emergency movements of personnel, aerial food drops to posts isolated by floods, training with ground forces, airlifting units, and air evacuation of patients. To maintain this air traffic, a military airways system, under the control of FEAF, was established. (Plate No. 90) This airways system, as modern as any in the world, was complete with airways traffic service, control centers, radio aids to air navigation, instrument landing facilities, search and rescue facilities, and weather service. It contained 20,000 miles of controlled routes linking all points in the Pacific and Far East areas.

Shortly after termination of hostilities in the Pacific Theater, use of FEAF military airways system was extended to authorized civil aid carriers operating over international air routes to, from, and within the Far East Command area. This resulted in a rapid and economical re-establishment of civil air commerce to war-torn countries of the Orient and contributed materially to economic rehabilitation.

The Air Forces of FEAF consisted of balanced elements comprising modern conven-

[275]

PLATE NO. 90

Pacific Military Airways, November 1948

[276]

tional and jet-type fighters, fast light-bombers, troop carriers, and, in addition, specially trained and equipped search and rescue units, which enhanced the safety of both military and civil air transport operations. Vigorous. training of these units continued and was periodically tested through the conduct of exercises and maneuvers, including joint training operations with army and navy forces.

FEAF continued to cooperate with U. S. Army and U. S. Navy Forces in the discharging of responsibilities of the U. S. Government in the Occupation of Japan.

Part II-U.S. Naval Command in the

Far East : Initial Operations

With the capitulation of Japan, the U.S. Pacific Fleet, consisting of the Third, Fifth, and Seventh Fleets and the North Pacific Force, occupied strategic naval areas of Japan and Korea and enforced the surrender terms imposed on the Empire.

In order to carry out preliminary missions for the Occupation, the U.S. Pacific Fleet Liaison Group with the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (FLTLOSCAP) was formed in late August 1945 under the command of Rear Adm. J. J. Ballentine, USN.15 Offices were set up in Yokohama with the major section of GHQ, and communications with Commander in Chief, Pacific, (CINCPAC) were established through the USS Teton. FLTLOSCAP was to control disarmament, demobilization, and repatriation, as these operations concerned the Navy; to advise GHQ on all naval matters; and to control Japanese Merchant Marine shipping until a special section was established with that particular responsibility.16

Naval zones of responsibility were defined to include the allocation of geographical areas to Third, Fifth, and Seventh U.S. Fleets, and to the North Pacific Force.17 The Third U.S. Fleet, under the command of Admiral Halsey, occupied Tokyo Bay and established minor naval and naval air facilities ashore in support of the Eighth U.S. Army. The Fifth U.S. Fleet, commanded by Admiral Spruance occupied and patrolled the sea approaches and coastal waters of Japan west of 135° east.

Elements of the Sixth U.S. Army were landed and firmly established in Kyushu, Shikoku, and western Honshu, while the clearance of mine fields in the Tsushima Strait-Inland Sea area was initiated by the Fifth Fleet. The Seventh U.S. Fleet, under the command of Admiral Kinkaid, assisted in staging, training and transport of troops in support of operations of the U.S. Forces in China and Korea. The North Pacific Force, commanded by Vice Adm. Frank J. Fletcher, guarded the lines of sea communications from the Aleutians to Russia and initiated clearance of the mine fields in the Tsugaru Strait between Honshu and Hokkaido.18

Initial occupation tasks of the Navy were mine-sweeping channels and transporting occupation troops to Japan. During the early part of October mine-sweeping operations were

[277]

limited to these areas essential for conducting the Occupation: Tokyo and Sagami Bays, Tsugaru Strait between Hokkaido and Honshu, and areas off Kochi in Shikoku, Sasebo in Kyushu, and Sendai in northern Honshu. Later in the month, mine-sweeping operations began in Bungo Suido between Kyushu and Shikoku, Iyo Nada between Honshu and Shikoku, and Hiro Bay off Kure.

Amphibious forces of the Third, Fifth, and Seventh Fleets immediately began to bring in the troops assigned for Occupation duty and to evacuate prisoners of war from Japan on the return trips. These operations were completed by the end of October.19 The Navy also became primarily responsible for transporting two million servicemen who were due to return to the United States. Escort carriers and attack transports were temporarily converted to augment shipping normally allotted for troop transport, and Operation "Magic Carpet" was successfully executed.20

COMNAVJAP : Organization and

Missions 21

As logistic conditions improved and the situation in Japan became stabilized, the functions and responsibilities of FLTLOSCAP changed. Shipping Control Authority for Japanese Merchant Marine (SCAJAP) was established under the command of Rear Adm. D. W. Beary on 12 October 1945;22 this organization assumed control of all ships over 100 gross tons operated by the Japanese. SCAP retained operational control over SCAJAP in repatriation shipping and related activities through the G-3 Repatriation Section. In dealings with the Imperial Japanese Government, SCAJAP worked through the Ministry of Transportation and the Ministry of Navy until the latter was deactivated on 31 December 1945. Thereafter, SCAJAP worked through successive civil offices established under the Japanese naval demobilization program. The Commander of the Fifth Fleet, Admiral Spruance, was the senior U. S. Naval officer in the Japan area and all naval activities ashore were under his operational control.

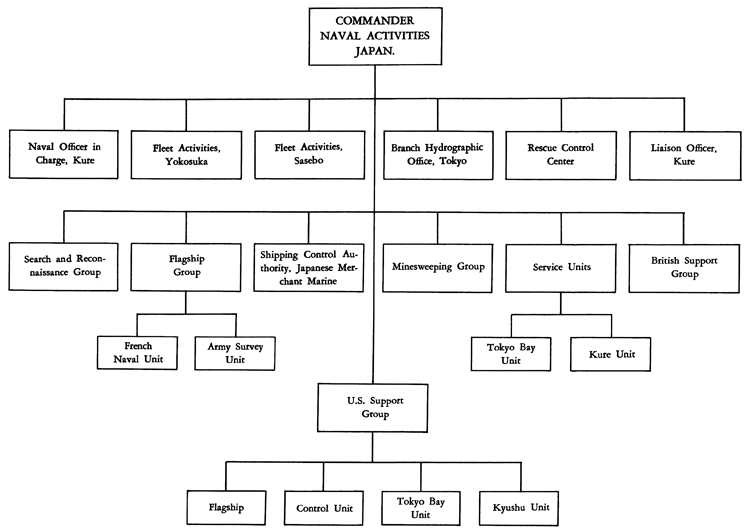

On 28 January 1946 FLTLOSCAP was dissolved and a naval command known as Naval Activities, Japan (COMNAVJAP) was established under the command of Vice Adm. R. M. Griffin, who retained this command until 9 July 1948 when he was relieved by Vice Adm. Russell M. Berkey.23 (Plate No. 91)

When the Far East Command was estab-

[278]

PLATE NO. 91

COMNAVJAP: Task Organization, Task Force 96, 1947

[279]

lished on 1 January 1947, Admiral Griffin was redesignated Commander Naval Forces, Far East (COMNAVFE), with the proviso that the title "Commander Naval Forces, Japan," would be used in connection with duties involving the Allied relationships for which Admiral Griffin was responsible to SCAP.24 On that same date Commander, Naval Activities, Japan, Commander, Naval Operating Base, Okinawa, and Commander, Naval Forces, Philippines, reported to CINCFE for duty while Commander, Marianas, reported for operational control. CINCFE in turn reassigned these responsibilities to COMNAVFE.25

Plans for the landing of Occupation forces, their equipment, and subsequent logistic support entailed the assignment of a large number of amphibious craft to Navy commands in Japan. Following completion of operations, most of the landing craft were returned to the United States by the middle of April 1946. Others were decommissioned and sunk by combat support forces or scuttled after being loaded with Japanese ammunition and poison gas.

Owing to personnel demobilization, transfer and consolidation of Occupation forces, and expansion of Army units in port areas, all port directorates except those at Kure and Kagoshima were abolished on 14 May 1946. Kagoshima controlled a heavy volume of United States and Japanese shipping involved in the repatriation program. The Kobe, Kagoshima, Nagasaki, and Fukuoka offices that reported ship movements were all closed by August when Army authorities assumed control of port operations.

The Port Director's office at Kure was established by the U.S. Navy, but when southern Honshu was turned over to the British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF) in March 1946, functions of the port director were assumed by the Royal Navy.26 The British Naval Officer in Charge, Kure, and all British naval units under his command were under the operational control of COMNAVJAP. In accordance with the provisions of SCAP Occupation Instructions, the former Japanese naval yard at Kure remained under United States control.27 The COMNAVJAP liaison officer in charge supervised scrapping .

[280]

of former Japanese naval vessels.28

Drydock and limited repair facilities at Kure, Sasebo, Yokosuka, and Maizuru were retained. By March 1948 approximately 11,000 Japanese workers were employed at Kure, Sasebo, and Maizuru. Almost 30 percent of these were actually engaged in ship work. Approximately 1,000 Japanese were employed by Fleet Activities, Yokosuka, for work in the ship repair department.29

Fleet Activities, Yokosuka and Sasebo

The largest shore establishments under COMNAVJAP were Fleet Activities, Yokosuka, and Fleet Activities, Sasebo, both located on the sites of former Japanese naval bases. Fleet Activities, Yokosuka, was responsible for general administration of the Yokosuka Naval Base, Yokosuka Marine Air Base, and Kisarazu Naval Air Base, and for control of the United States personnel in communities adjacent to these establishments. Other duties included demilitarization, inventory, and disposition of enemy equipment in its area of responsibility in accordance with current instructions, operation of Radio Tokyo (Station NDT)30 and other communications facilities located in the Yokosuka area; assistance in the logistic support of fleet units based at Yokosuka and naval units ashore in the Tokyo Bay area; and administration of Port Directors at Yokosuka, Yokohama, and Tokyo. By inspection and surveillance, control of all former Japanese naval vessels in Japanese ports east of longitude 138° was maintained.

With the surrender of the Japanese, the U.S. Navy was assigned Yokosuka as its zone of authority.31 The Japanese had evacuated hastily before the Allied landings and left the base in complete disorder. Demilitarization was begun immediately and was completed within the first year. Ninety percent of the former arsenal was returned to the people for reindustrialization.32

Yokosuka Base repaired ships supporting the Occupation, became the supply center for the U.S. Navy ashore and afloat in Japan, and governed the city of Yokosuka. The military government of Yokosuka was integrated into the Base organization instead of being a separate command.

The area of responsibility and scope of

[281]

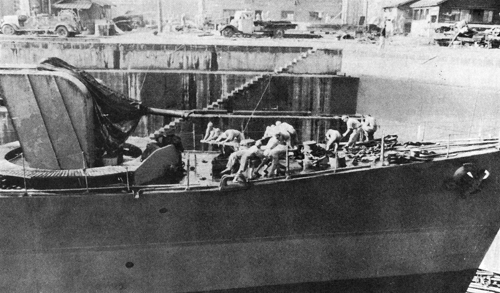

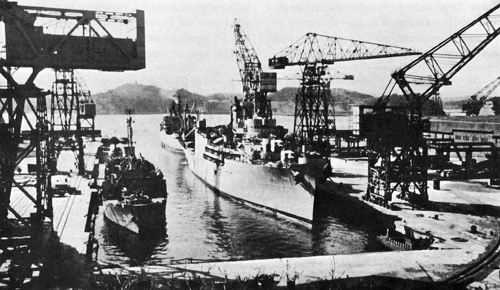

Japanese destroyer Okake is disarmed for conversion to troop

transport duty, Maizuru Naval Base.

Yokosuka Naval Base drydocks service an American destroyer. Completely repaired,

these drydocks offer modern service to ships in port.

PLATE NO. 92

Fleet Activities, Japan

[282]

command of Fleet Activities, Sasebo,33 were considerably smaller since the greater part of Sasebo Naval Base was then under the jurisdiction of the Second Marine Division, operating under Eighth U.S. Army control.34

Prior to the end of the war, U.S. mine sweepers had been engaged in clearing the mine fields in the East China Sea. Upon cessation of hostilities, this operation lost its importance and sweeping operations in the East China Sea southwest of Kyushu were suspended. All mine craft were returned to Buckner Bay (Okinawa) for regrouping and preparation for their new tasks incident to the evacuation of Allied military personnel and the entry of Occupation forces.35

More than 3,700 acoustic, approximately 2,500 pressure type, and 4,500 magnetic mines had been laid in Japanese waters during the war. Samples of United States mines had been recovered by the Japanese, analyzed, and means devised for removing them. They developed effective sweeping for ground mines of all types and for acoustic mines. While their methods of sweeping influence (pressure type) mines were not as effective as those of the United States, they reported that before the end of hostilities they had swept 1,250 United States influence mines; they also reported that 623 of their ships were either sunk or damaged by mines during the war period.36

The immediate task assigned was the clearing of navigable channels, through Japanese and American mine fields, into certain key Japanese ports to secure the landing of Allied Occupation units; this was to be followed by additional clearance of channels and harbor facilities to insure safe entry for the supply vessels brought in to maintain the troops ashore. The secondary tasks assigned were the sweeping of sea lanes around southern Kyushu and between the Japanese ports of occupation so that United States ships could move without restriction between these ports, and providing mine-sweeping units for task groups of Fifth Fleet.

Early in the Occupation, the Japanese were instructed by Commander Fifth Fleet to supply information on mine fields and safe channels for the ports of Sendai, Nagoya, Kobe, Osaka, Kure, Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Wakanoura. Arrangements were made to have the Japanese meet United States forces and assist in sweeping operations which began 12 September 1945. Japanese coastal defense vessels were used as additional mine sweepers and were controlled by Commander Minecraft, U.S. Pacific Fleet (COMINPAC), through a Task Group Commander established in Tokyo, and through U. S. Sweep Group commanders in the field. Japanese sweepers not operating directly under local U. S. commanders were controlled from Tokyo where COMINPAC's representatives issued the necessary directives

[283]

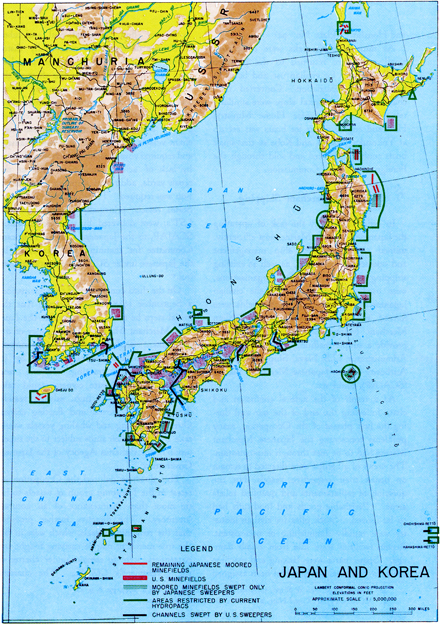

to the Japanese mine-sweeping central authority. Where practicable they were assigned tasks directly in support of United States interests; these tasks included entry into Japanese ports, freedom of movement on the high seas for United States shipping, and elimination of floater sources. After completing such tasks Japanese naval units were employed to assist the Japanese repatriation program, then to sweep Japanese ports which appeared desirable for Japanese use and might later be desirable for the use of United States vessels. Since Japanese mine-sweeping vessels were equipped to sweep for moored mines only, they were assigned to areas which were sown with this type of mine. Later when United States vessels conducted magnetic and acoustic exploratory sweeps of these waters, no mines were found.37 Progress made during the initial mine-sweeping operations in Plate No. 93.

The U.S. Navy mines laid in Japanese and Korean waters were almost exclusively influence mines containing firing mechanisms which had been modified; pressure and low frequency acoustic mines were an exception. Since standard mine-sweeping gear and procedures were of reduced effectiveness against these modified mines, new gear and procedures were instituted at the earliest possible stage of the mine-sweeping campaign. No pressure sweeps were available in the forward area for use during the earliest sweeping in connection with the Occupation of Japan, and entry of transports heavily loaded with men presented a serious problem involving potential casualties. Even though the entry channel was swept for all other types of mines, and chosen for probable lack of pressure mines, some means was obviously desirable to avoid risk. "Guinea-pig" ships were obtained and fitted out for this purpose. While sweeping, these ships were operated by skeleton volunteer crews. All personnel remained top-side, operating the ship by remote engine-room controls. Precautions were taken against personnel casualties by padding decks and overheads and by providing crash helmets. "Guinea-pig" ships were not used until after the completion of the magnetic and acoustic sweeping. In planning the mine-sweeping operations in Japanese home waters, an effort was made by choice of harbors and channels to avoid as much as possible those areas sown with pressure mines. The sweeping of ports mined with large numbers of pressure mines was deferred sufficiently to allow a high percentage of these mines to become sterilized.38

On 25 March 1946 a total of 328 Japanese vessels and 9,064 Japanese personnel were engaged in mine-sweeping duties.39 The last moored mine-sweeping tasks were completed in August 1946. As the sweeping progressed, vessels and personnel were released so that by the end of 1948 less than 1,500 Japanese personnel and only fifty-two vessels were engaged in mine-sweeping. Major ports of Tokyo Bay, Nagoya, Nagasaki, Sasebo, Kobe, and Osaka were completely cleared of mines and were declared open to all shipping. Operations were continued in the Inland Sea and the Shimonoseki Straits between Kyushu

[284]

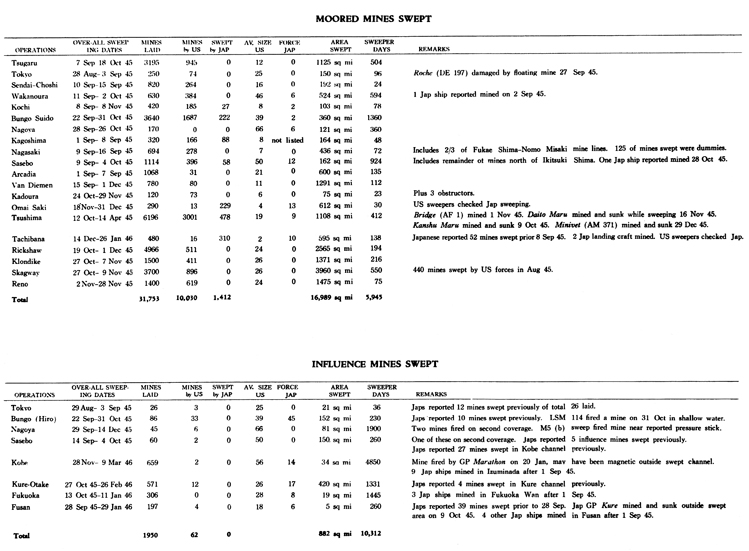

PLATE NO. 93

Mine Situation in the Western Pacific, 20 February 1946

[285]

and Honshu.40(Plate No. 94)

As mine-sweeping tasks were completed, small craft were returned to the Japanese Home Ministry for civilian use and listed as available for repatriation. Converted merchant ships and hospital ships were similarly returned to the Japanese Home Ministry. Hull and engine repair for boats was set up at Yokosuka, Sasebo, and Kobe so that small boats could be repaired and sold through the Foreign Liquidation Commission.

In order to simplify the task of operating the Japanese Merchant Marine most efficiently, trained civilian Japanese ship management and operational personnel, as well as existing shipping and related civilian organizations, were used. Representatives of the civilian Japanese ship industry and related fields were formed into a group known as the Civilian Merchant Marine Committee (CMMC) to provide a simple medium through which the Administrator, U.S. Naval Shipping Control Authority for the Japanese Merchant Marine (SCAJAP), could act.

As a result of the natural confusion and chaos following the end of the war and during the first phases of the Occupation, many problems concerning the Japanese Merchant Marine had to be met through improvisation. The crews of all ships were directed to remain on board their respective vessels, but the question of replacements and qualified reliefs arose. Perishable goods and foodstuffs had to be moved. Stock piles for civilian industry were rapidly diminishing or nonexistent. Repair facilities were idle from bomb damage. Spare parts were lacking and machine tools for their manufacture had been assigned to the war effort. Fuel oil, coal, and lubricants were deficient and were badly distributed. Civilian shipping organizations had been fully mobilized for the war effort at the expense of the basic national economy. Labor was scarce and the enormous problem of repatriating over six million nationals required prompt action. Since many Japanese merchant vessels had suffered from bomb damage and required voyage repairs, which were delayed by lack of facilities and spare parts at the repair yards, additional shipping for repatriation was required. Therefore, various United States vessels, principally Liberty ships and LST's, were delivered by the Administrator, SCAJAP, to the Japanese Civilian Merchant Committee for manning and operation by the Japanese under SCAJAP operational control.41

On the third anniversary of the Occupation, 2 September 1948, SCAP directed that the initial steps be taken to decentralize the Japanese Merchant Marine. Each agency of the government would control the Government owned special type vessels required by its missions: patrol, training, research, and weather ships. Private owners would take over vessels such as tugs, salvage vessels, dredgers, small ferries, and floating cranes. Owners of fishing and whaling vessels would take control of their ships subject to the supervision of the Fisheries Agency of the Japanese Government.

This directive reduced the Occupation interest in the foregoing group of vessels to little more than maintenance of an accurate inventory. The directive further provided that the remaining vessels, which were in fact the true merchant marine carrying freight and passengers, were to remain under charter to the government's CMMC. The charters,

[286]

PLATE NO. 94

Moored and Influence Mines Swept: August 1945-April 1946

[287]

however, were to be changed from "bare boat" to time charters; this thrust the responsibility of manning, supplying, and repairing ships on the owners. The entry of private enterprise into these fields was expected to reduce the drain on the national economy and prepared private companies for eventual full control of their ships. SCAP designated SCAJAP, which continued to operate as a staff section of COMNAVFE, to implement this program, regulating its progress to the ability of the shipping industry to assume responsibilities.42

One of the largest tasks performed by the Navy in Japan was the repatriation of Japanese nationals from all areas of the Pacific and the return of aliens in Japan to their homes.43 Responsibility for the operational control of repatriation shipping and the super- vision of its maintenance was vested initially in Commander, U.S. Fifth Fleet, insofar as it concerned former Japanese naval ships, and in FLTLOSCAP for former merchant ships. Repatriation was under way when the Shipping Control Authority for the Japanese Merchant Marine (SCAJAP) was formed.44 SCAJAP was continued as a task group of COMNAVJAP. By the end of 1946 mass repatriation was completed from all areas except those controlled by the U.S.S.R. SCAJAP vessels continued to be available to repatriate the thousands of military and civilian personnel believed held in these areas.45

Suppression of Illegal Traffic

A considerable amount of unauthorized waterborne traffic was conducted between Korea and Japan, consisting mainly of Japanese attempting to return to Japan and Koreans attempting to return to Korea with more than their authorized allowance of personal effects as well as extensive commercial smuggling. In order to prevent these activities and the introduction of contagious diseases by illegal entrants rom Korea, Occupation forces maintained beach and off-shore patrols to intercept such traffic.46 Destroyer patrols operated in Korean waters from the cessation of hostilities until January 1947 under Commander, Seventh Fleet, and after that date under Commander Naval Forces, Far East, (COMNAVFE); in addition, intermittent patrols were maintained off the coast of Honshu and Kyushu.

It was recognized from the start that the suppression of illegal sea traffic in Japanese and Korean waters should eventually become the responsibility of the Japanese and Korean governments. Japan, however, did not have a coast guard organization prior to the war; the coast guard functions were performed by the Imperial Japanese Navy. Korea was in the initial stages of achieving national sovereignty. A small operating coast guard consisting of former United States vessels was

[288]

established in Korea.47 In Japan, twenty-eight patrol craft formerly engaged in mine sweeping were allocated to the Japanese Coast Guard because it was felt that activation of the Coast Guard would reduce U.S. Navy patrol tasks. This added new responsibilities to the U.S. Navy in the form of supervision and direction of the coast guard operations.48

In order to coordinate better the work of various agencies formerly concerned with maritime matters and to provide a firm foundation for the development of a Japanese Coast Guard, the Japanese Diet passed the Maritime Safety Authorities Bill. This law became effective on 1 May 1948, establishing a Maritime Safety Board under the Ministry of Transportation.49

Miscellaneous Naval Activities 1946-1948

Branch Hydrographic Office: On 1 July 1946 Branch Hydographic Office, Tokyo, was established with Commander E. B. Dodson, USN, in charge. He also assumed direction of the Japanese Hydrographic Office which had formerly been under the supervision of SCAP through the Army Engineer Corps. The mission of the Hydrographic Office at Tokyo, in addition to services to United States and Allied shipping, was the re-organization of Japanese hydrographic facilities and resumption of hydrographic work in Japanese waters. When the U.S. Office was closed in 1948, work was continued by the Japanese Office.

Support Groups: United States and British Naval Support Groups were assigned tasks that backed the U.S. Army and Navy and Allied units in their control of the Japanese Empire. They conducted inspections of Japanese shipping including suspicious vessels encountered at sea, controlled movements and inspections of ex-Japanese naval vessels and shipping, performed escort duties, and assisted in air-sea rescue operations. Units were maintained in the Yokosuka and Sasebo areas available to meet emergencies and frequent

[289]

visits were made to all ports open to United States shipping to observe conditions and inspect Japanese shipping. Each group contained one cruiser and four destroyers. The U.S. Group had three additional destroyer escorts assigned primarily to perform patrol duties in Korean waters. During 1947 and 1948 Support Groups continued assigned tasks. The British Group operating under COMNAVJAP was dissolved on 30 November 1947 and in its place a unit consisting of three destroyers was formed to operate as a part of the U.S. Support Group.

Naval Air Units: In February 1946 COMNAVJAP had under his control one Marine Air Group, MAG 31, composed of 116 aircraft of various types.50 The Naval Air Base at Kisarazu serviced the needs of Naval Air Transport Service (HATS) until it was decommissioned in May 1946 and the NATS detachment was moved to Atsugi Airfield; Air search and reconnaissance functions were operated directly from Headquarters COMNAVJAP, with air facilities provided by Fleet Air Wing One. The boundaries of search and reconnaissance, including search and rescue functions, were defined by CINCPAC and the ports of Yokosuka and Sasebo were selected as seaplane bases. Ready duty destroyers, fleet tugs, and seaplanes were used singly or in coordinated action in rescue search missions at sea. These missions included searching for downed planes, removing sick patients from ships, and towing disabled Allied and Japanese vessels.

Communications: Communications for GHQ and the Navy Liaison Office were handled by the USS Teton upon arrival at Yokohama in August 1945. When the Army Mobile Radio was set up in Tokyo, a mobile communications unit set up transmitting and receiving stations to handle the Navy communications for GHQ. Later, this unit was dissolved and Radio NDT at Yokosuka took over the guard for SCAP, SCAJAP, FLTLOSCAP, and the Port Directors in this area. In early 1947 physical control of this unit was transferred to Headquarters, COMNAVFE. At the end of the year the Army receiver station located on Tsushima Island near Tokyo took over the receiving side of the Guam-Tokyo radio teletype circuit, making possible the joint use of facilities and personnel. A joint emergency transmitter station was constructed at Totsuka which furnished emergency service requirements of GHQ, FEAF, Army Air Communications Service, and Eighth Army Headquarters.51

The cooperation of Navy and Air components with the Army ground forces made it possible for the Occupation of Japan to proceed in an orderly, efficient manner. From the very beginning, when individual and coordinated missions were outlined, through the initial landings and later when the Occupation was established, the contribution of each of the forces in carrying out its assigned missions was a tangible element of the success of the Occupation.

[290]

Go to

Last updated 11 December 2006 |