CHAPTER I

THE JAPANESE OFFENSIVE IN THE PACIFIC

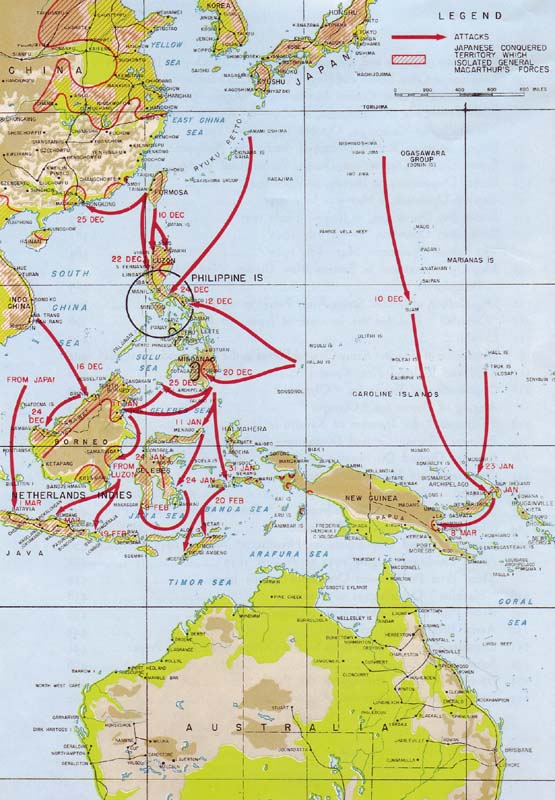

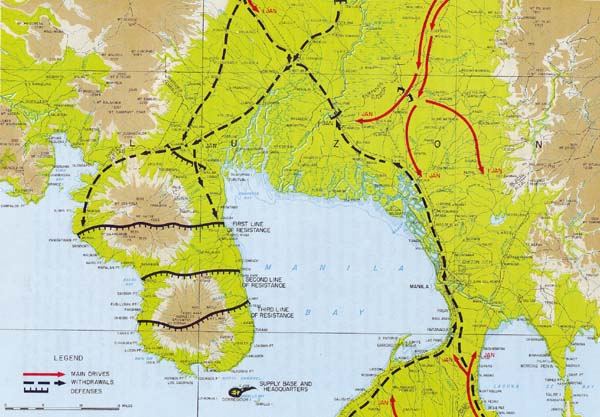

The devastating attack against Pearl Harbor on 7 December 19411 and the subsequent Japanese thrusts in Asia left only one important obstacle in the path of the Japanese onslaught to the Southwest Pacific-General MacArthur and his small forces, isolated in the Philippines. (Plate No. l) Their tenacious defense against tremendous odds completely upset the Japanese military timetable and enabled the Allies to gain precious months for the organization of the defense of Australia and the vital eastern areas of the Southwest Pacific. Their desperate stand on Bataan and Corregidor became the universal symbol of resistance against the Japanese and an inspiration for the Filipinos to carry on the struggle until the Allied forces should fight their way back from New Guinea and Australia, liberate the Philippines, and then press on to the Japanese homeland itself.2

By the end of November 1941 the Japanese had completed their over-all preparations for war against the United States, Great Britain, and the Netherlands. The Japanese Combined Fleet was directed to attack the naval forces of those nations and to combine with the Japanese Army and Air Force in a many-pronged offensive against Allied territories. The target date for the commencement of operations was 8 December 1941, East Longitude Time.3

Japan's ultimate aim was complete hegemony in Asia and unchallenged supremacy in the western Pacific. Her strategic objectives were the subjugation of the Philippines and the capture of the immense natural resources of the Netherlands East Indies and Malaya. The conquest of the Philippines became an immediate military necessity. The Islands represented America's single hope of effective resistance in Southeast Asia, and, given the time and resources, General MacArthur would

PLATE NO. 1

The Japanese Conquests which Isolated General MacArthur's Forces in the Philippines

[1]

accomplish his long-range plan of making the islands impregnable.4 He once called the Philippines "the key that unlocks the door to the Pacific." The Japanese understood this completely, for the islands lay directly athwart their path of future aggression. Close to South China and the island stronghold of Formosa, they were not only an obstacle to Japan's international ambitions, but they could be made into a powerful strategic springboard for their drive south and eastward. Flanking the vital sea routes to the south, they were the hub of the transportation system to Southeast Asia and the Southwest Pacific; from the Philippines, lines of communication radiated to Java, Malaya, Borneo, and New Guinea. Economically too, they were necessary to Japan's grandiose scheme of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. As a thriving democracy, the Philippines were a living symbol of American political success in Asia and a direct negation of the national and moral principles represented by Japan. The Japanese were convinced that the Philippines must be conquered.

The abundant supply of oil, rubber, and other essential products in the Netherlands East Indies and Malaya which Japan needed for her vast war machine was another lucrative prize. The Japanese planned to isolate this region by destroying Allied naval power in the Pacific and Far Eastern waters, thus severing British and American lines of communication with the Orient. The unsupported garrisons of the Far East would then be overwhelmed and the areas marked for conquest quickly seized. Air attacks launched from progressively advanced airfields would prepare the way for amphibious assaults.

The first major operations would be directed against the Philippines and Malaya, with the invasion of British Borneo following as soon as possible. In the early stages of these campaigns, other striking forces were to seize objectives in Celebes, Dutch Borneo, and southern Sumatra, enabling the forward concentration of aircraft to support the invasion of Java. After the fall of Singapore, northern Sumatra would be occupied; operations would also be carried out against Burma at an appropriate time to cut the Allied supply routes to China. Singapore, Soerabaja, and Manila were expected to become major bases.5

The Japanese also planned to capture other strategic areas where they could establish advance posts and raise an outer barrier against an Allied counteroffensive. Their scheme of conquest envisaged control of the Aleutians, Midway, Fiji and Samoa, New Britain, eastern New Guinea, points in the

[2]

Australian area, and the Andaman Islands in the Bay of Bengal. All these would be seized or neutralized when operational conditions permitted.6

If the offensive succeeded, the United States would be forced back to Pearl Harbor, the British to India, and China's life line would be cut. With this eminently favorable strategic situation and control of the raw materials which they required, the Japanese felt they would be in a position to prosecute the war to a successful conclusion and to realize their ambition to dominate the Far East.

Japan's war potential, her probable action and plans of invasion had been brilliantly anticipated many years before by Homer Lea in his amazing book, The Valor of Ignorance, published in 1911.7 Although this extraordinary publication had created a sensation among the general staffs of the world, the growing Japanese menace was not fully appreciated. Among the few, General MacArthur had clearly recognized the danger signals. His long and close association with the Philippines and the Orient had given him a rich background of knowledge and experience with which to judge the situation in the Far East. His grasp of the Japanese character and psychology and his understanding of Japanese military policy and aggressive intentions had induced him to voice repeated warnings of the shape of things to come. In a desperate race against time, he had attempted to stem the tide by initiating preparations for the defense of the Philippines. Working against almost insuperable political and administrative obstacles, he had commenced in 1935 to create a modern Philippine Army of ten divisions to counter the Japanese attack that he knew would soon come from the north, swiftly, fiercely, and without warning.

As the signs of impending conflict became unmistakably clear, General MacArthur prepared his meager forces in the Philippines for the inevitable storm. He grouped them into three principal commands, the Northern Luzon Force, the Southern Luzon Force, and the Visayan-Mindanao Force. The major unit was assigned to northern Luzon, for General MacArthur expected the principal enemy attack to be launched at the entrance to the great Central Plain, the natural corridor from Lingayen Gulf to Manila.8

The forces at General MacArthur's disposal included regular United States Army

[3]

units, regiments of the Philippine Scouts which were a part of the Army of the United States, the Philippine Army, and the Philippine Constabulary units. From 1 September 1941, orders were progressively issued to various units of the Philippine Army calling them to active duty. The over-all command was designated the United States Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE) which had been created by the War Department on 26 July 1941. The air arm of USAFFE, designated the Far East Air Force (FEAF), was headed by Maj. Gen. Lewis R. Brereton.

The Japanese operations which plunged the United States into total war occurred in rapid sequence and were well timed. The surprise attacks against Pearl Harbor and the Philippines were followed at once by the invasion of Malaya, the seizure of Guam, and the capture of other American and British areas in the Pacific and the Far East. When the first blows fell, Nazi Germany, Japan's ally, had already conquered most of Europe. The German armies were deep in Russia on a broad front, and in the Middle East Rommel's armored divisions were attacking the British troops defending Egypt.

General MacArthur recommended that the Soviet Union strike Japan from the north. Such pressure, he felt, supplemented by United States air concentrations in Siberia, would limit the range of Japan's striking power, counter her initial successes, and gain time to strengthen the Philippines and the Netherlands East Indies. He believed it would throw Japan from the offensive to the defensive and that it would save the enormous outlay in blood, money, and effort necessary to regain lost ground. The Soviet Union, however, did not elect to engage in hostilities with Japan, and the British were unable to supply the reinforcements needed to protect their outposts in the Far East. The burden of stopping the Japanese rested largely upon the Allied forces already in Southeast Asia and the Pacific region and such additional strength as the United States could provide.9

Allied Strategy after Pearl Harbor

The United States was not prepared for war, and the effort which could be exerted against the Japanese was immediately and sharply limited by the global strategy adopted. President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill, in a Washington conference after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, confirmed a previous decision to concentrate first on the defeat of Germany.10 Until victory was won in Europe, operations in the Pacific would be directed toward containing the Japanese and maintaining pressure upon them by conducting such offensive action as was possible with the limited resources available.11

The prospects for the Allies in the Pacific were highly discouraging. Eight battleships of the United States Pacific Fleet had been sunk or damaged at Pearl Harbor. Two days later the British battleship, Prince of Wales, and the battle cruiser, Repulse, were sent to the bottom off the east coast of Malaya. There remained in Netherlands East Indies waters some United States, Dutch and British cruisers, destroyers and submarines, but Japa-

[4]

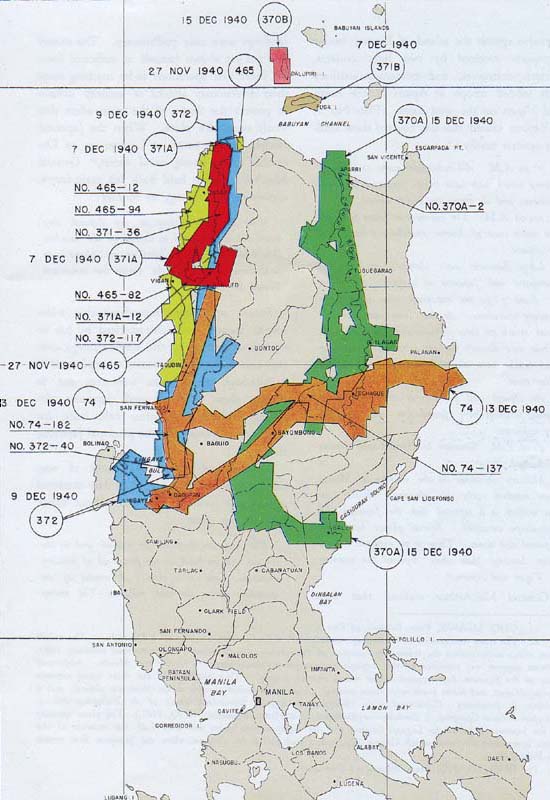

PLATE NO. 2

The Japanese Invasion of the Philippines and the Forces Employed

[5]

nese naval supremacy was temporarily assured. The enemy already possessed overwhelming superiority in air and ground forces available at well-developed bases extending from French Indo-China to Formosa and the Mandated Islands.

The principal obstacles to Japanese expansion in Southeast Asia were the United States and Filipino forces under the command of General MacArthur in the Philippines, the British Imperial III Corps defending Singapore, and the concentration of Dutch forces in Java. Without substantial reinforcement these forces were not capable of more than delaying action.12

The Attack against the Philippines

The Japanese strike against the Philippines on 8 December was anticipated by General MacArthur several days in advance. On 4 December his pursuit interceptor planes began night patrols. Each night, they located hostile Japanese bombers from twenty to fifty miles out at sea, but the enemy planes turned back before actual contact was made. The last of these night flights was intercepted and turned back at the exact time of the attack on Pearl Harbor.13

When the enemy attacked the Philippines in overwhelming strength, the relatively weak American air force of fewer than 150 planes suited to combat service was totally inadequate to turn back the attackers.14 Enemy bombers were guided in by sympathizers or espionage agents located near military objectives. Complete reports on American airfields and troop dispositions, procured by an extensive espionage net just prior to hostilities, enabled the Japanese to concentrate their attacks accurately on the most important objectives. Serious damage was inflicted on American planes and airdrome installations in the central Luzon area. On 10 December the naval base at Cavite was heavily bombed, and simultaneously the Japanese began their ground

[6]

offensive against the island of Luzon; twelve transports escorted by two light cruisers, thirteen destroyers, and numerous auxiliary craft landed troops at Aparri in the north and Vigan on the west coast. (Plate No. 2)

Reports issued that day covered these landing actions briefly:

7:30 A.M All indications point to a heavy enemy attack with land troops supported by naval elements and air forces on North Luzon.

10:00 A.M. The enemy is in heavy force off the north coast of Luzon, extending from Vigan to Aparri.

Large Japanese navy elements are escorting transports with Japanese air support. At Vigan at about 7:30 six transports were engaged in landing operations. At that time our bombardment attack on these ships created grave damage. Three were directly hit, one immediately capsizing and bombs were observed hitting close to the other three.

At Aparri and perhaps at other contiguous points, landings were effected but exact strengths are unknown.

4:00 P.M. Situation in North Luzon remains unchanged.

Military objectives in the vicinity of Manila were bombed early this afternoon. While not yet verified, it is reported that the Japanese did not escape unscathed. Several planes have been reported shot down. There is no evidence of any other landings than those reported this morning at Vigan and Aparri.15

General MacArthur realized that these landings were only preliminary. The enemy had not yet shown himself in sufficient force for these two operations to be anything more than diversionary attacks or security actions to protect the flanks of the main effort that would soon take place. When the Japanese landed in the south at Legaspi on 12 December under strong naval escort,16 General MacArthur again held back his main forces, explaining his strategy as follows:

With the scant forces...at my disposal, they could not be employed to defend all the beaches. The basic principle of handling my troops is to hold them intact until the enemy has committed himself in force....17

Future operations throughout this widespread theater were characterized by his tenacious adherence to this single strategic concept and the tactical measures to implement it.

Although small units were sent out to contain these relatively weak Japanese elements, General MacArthur held back his main force, waiting for the principal Japanese thrust.

At the end of the first week of war, the General reported many widely scattered actions but revealed that the all-out attack had not yet come:

The situation, both on the ground and in the air, was well in hand as the first week of military operations came to a close. A resume of the operations during the week follows: The enemy

[7]

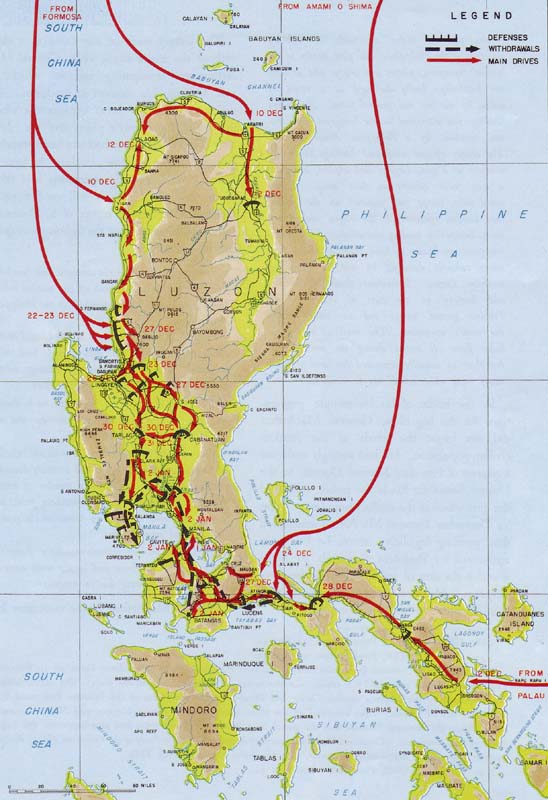

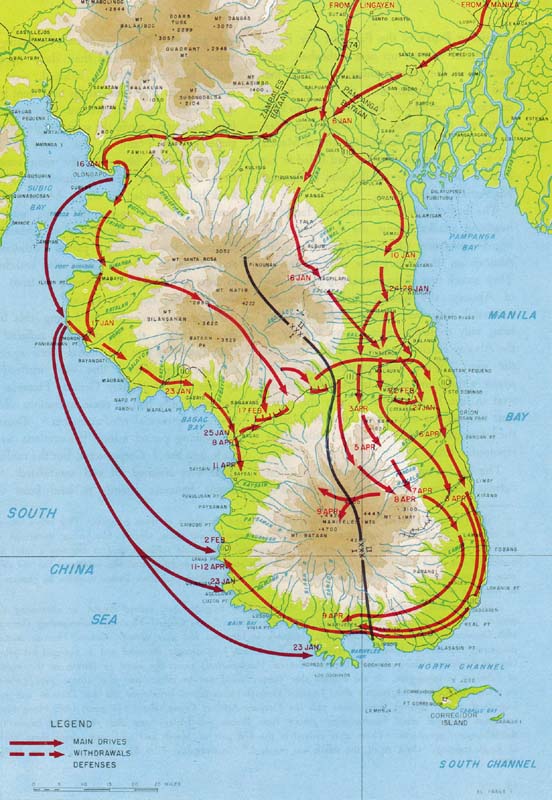

PLATE NO. 3

Aerial Reconnaissance of Luzon

[8]

PLATE NO. 4

Operations on Luzon

December 1941

[9]

carried out 14 major air raids on military objectives in the Philippines, but paid dearly in the loss of transports, planes and troops and at least two battleships badly damaged as a result of action by our air and ground forces. An enemy landing was attempted in the Lingayen area, but was repulsed by a Philippine Army division. The enemy effected unopposed landings in limited numbers at Vigan, Legaspi and Aparri, but there is only local activity in those areas. Enemy naval units, troops and materiel on the ground were bombed effectively in the Vigan and Aparri areas, hampering landing operations. Four enemy transports are known to have been sunk and three others seriously damaged by our air force off northern Luzon. Individual deeds of heroism and bravery on the part of American and Filipino ground troops and air units marked the week's operations....The total of enemy air losses from all causes during the week is not less than 40 actually accounted for and probably many more which could not be verified....18

In the midst of his last-minute preparations for the big blow, General MacArthur did not forget the needs of the stricken civilian population. He had strongly endorsed a request of President Manuel Quezon to the United States for funds for public relief and the protection of the civilian population. On 14 December General MacArthur announced that, pending legislative action, he had been authorized by President Roosevelt to make available the sum of 20,000,000 pesos for these purposes. He took immediate action to turn this amount over to President Quezon.19

The second week of war came to a close without the major attack which General MacArthur was anticipating and for which he was holding his reserves in readiness. He did not commit his forces because the whole pattern of the enemy's plans and the direction of his main thrust had not been revealed. Except, for a Japanese landing in force at Davao,20 no large-scale operations had taken place, and aerial activity still predominated. General MacArthur's report of 21 December indicated, however, that the fighting was growing in intensity:

Increasing activity on the northern and southern fronts marked the second week of the war in which Japan is seeking to gain a foothold in the Philippine Archipelago.

Ground and air commands of the United States Army Forces in the Far East struck back with increasing fury at the invaders, routing enemy patrols in the Vigan and Legaspi sectors.

The enemy launched 12 major air raids during the week, but for the most part damage was not serious and casualties were light.

Our air force landed telling blows on the invaders at Legaspi, where it bombed and seriously damaged two transports and shot down a number of enemy planes. At Vigan, on the northern front, our airmen destroyed at least 25 planes and set fuel supplies afire.

In Davao on the extreme southern front the enemy landed in force and as the week came to a close, heavy fighting was in progress.21

General MacArthur in the meantime kept

[10]

a close watch on the low, sloping beaches of Lingayen Gulf where, weeks before the initial blows, he had stationed the 11th and 21st Divisions of the Philippine Army at beach defenses. In the deceptive quiet of the gray dawn that spread over Lingayen Gulf on 22 December 1941, the great enemy blow fell at last. The communique that morning made no attempt to minimize the ominous situation. General MacArthur reported tersely:

Nichols Field was bombed at about 8:00 A.M. today.

There was sighted this morning off Lingayen Gulf a huge enemy fleet estimated at 80 transports. Undoubtedly this is a major expeditionary drive being aimed at the Philippines.22

The Japanese knew where to strike. Strength, location, and routes of the American main groupings were accurately plotted on the intelligence maps of the Japanese Headquarters. More than a year before their invasion of the Philippines-November and December 1940-the Japanese had made extensive aerial surveys of northern Luzon, selecting the areas of strategic importance and the points they could best attack. (Plate No. 3) Their objective was the prompt and complete annihilation of the defending forces so as to clear without delay the way to the rich areas that lay to the south.

Only two days after the mass landings at Lingayen Gulf, where the greatly outnumbered defenders on the beaches were ultimately overwhelmed by the invaders, another large Japanese force landed at Atimonan, on Lamon Bay, on the east coast of southern Luzon.23 This was much closer to Manila and central Luzon than the original Japanese elements that had landed far to the south at Legaspi.

With these landings the strategy of the Japanese commander, Lt. Gen. Masaharu Homma, became immediately apparent. It was obvious that he sought to swing shut the jaws of a great military pincers, one prong being the main force that had landed at Lingayen, and the other the smaller but nonetheless powerful units that had landed at Atimonan. (Plate No. 4) If these two forces could effect a speedy juncture, General MacArthur's main body of troops would have to fight in the comparatively open terrain of central Luzon, with the enemy to the front and to the rear. The Japanese strategy in arrogant optimism envisaged complete annihila-

[11]

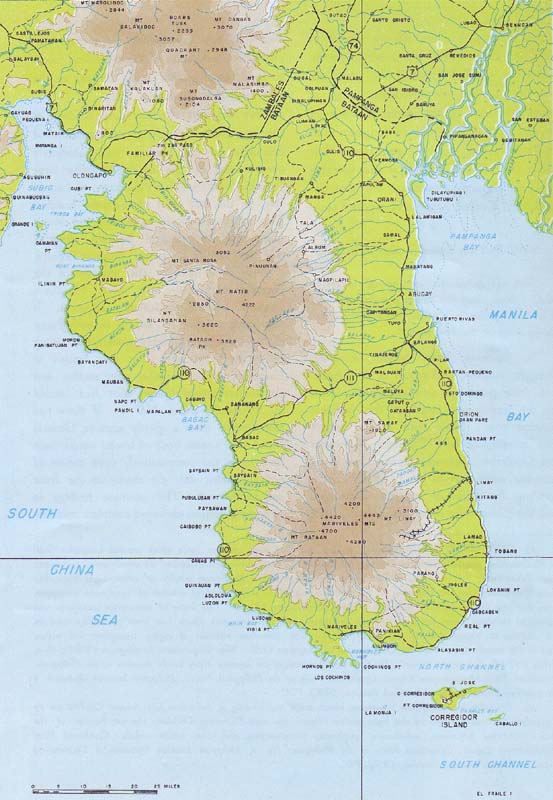

PLATE NO. 5

Terrain Features of Bataan

[12]

PLATE NO. 6

Route of Strategic Withdrawal to Bataan and Concept of Defense

[13]

tion of the Luzon defense forces within a very short period.24 With the principal island of the archipelago under their control, the Japanese could look forward to an easy conquest of the remainder of the islands.

Strategic Withdrawal to Bataan

General MacArthur's concept of defense against a superior force landing in northern Luzon was one of delaying actions on successive lines drawn across the great Central Plain from Lingayen Gulf in the north to the neck of the Bataan Peninsula in the south. While these delaying actions were retarding the enemy advance, General MacArthur would withdraw his troops from Manila, from the south, and from the Central Plain into Bataan where he could pit his intimate knowledge of the terrain against the Japanese superiority in air power, tanks, artillery, and men. To allow his main bodies to be compressed into the Central Plain by the Japanese advancing from both directions could only mean early and total destruction. By retiring into the peninsula, he could exploit the maneuverability of his forces to the limit, for Bataan's forests and ravines gave him his only chance of survival. (Plate No. 5)

On Bataan, the main line of resistance would run from Moron, on the coast of the China Sea, to Abucay, on the shore of Mawla Bay. Should it become necessary, the defenders could drop back to a reserve line some six or eight miles to the rear. A third projected line crossed the Mariveles Mountains, the highest part of the peninsula. Still farther to the rear, Corregidor, separated from Bataan by two miles of water, would serve as the supply base for the Bataan defense and deny the Japanese the use of Manila Harbor, even though they should take the city of Manila itself.

The growing menace of encirclement by superior numbers induced General MacArthur to act quickly. The difficult problem he faced was to sideslip his troops westward in a series of rapid maneuvers and holding actions to the rocky peninsula and to the island forts in Manila Bay before superior forces of the enemy could cut off their path from the north. The crux of the problem was the successful passage of a famous tactical defile-the bridge at Calumpit, just south of San Fernando in Pampanga, where Highway No. 3 from northern Luzon to Manila joined with Highway No. 7 leading into Bataan. (Plate No. 6) The movement of the Southern Luzon Force, already complicated through the passage of Manila, was inevitably canalized at Calumpit, and once across the bridge, this force would also have to pass through San Fernando before it was safely on the road to Bataan.

As a corollary, the hard-pressed Northern Luzon Force would have to hold the enemy back from San Fernando and the Calumpit bridge no matter what the price until the Southern Luzon Force had cleared the critical

[14]

defile, or General MacArthur stood to lose nearly half the forces with which he expected to defend Bataan and Corregidor.

To effectuate his strategy for protecting San Fernando until the movement of the Southern Luzon Force was completed, General MacArthur designated several lines for delaying action across the great Central Plain. The line directly north of San Fernando was to be held at all costs until the beginning of 1942, by which time, according to the schedule for the withdrawal of the Southern Luzon Force, the latter would be safe.

The lack of military transportation was solved by using scores of commercial buses which were commandeered to speed up the movement of the Southern Luzon Force.25 At the same time both commercial and military trucks were employed day and night in endless columns to move goods, ammunition, equipment, and medical supplies from Manila to Bataan. In anticipation of the needs of war, General MacArthur had initiated the construction of a general hospital at Limay on the east coast of Bataan, and now, with the outbreak of the conflict, additional supplies were taken to the peninsula for the establishment of a second hospital.26

As the complicated but precisely timed withdrawal operation was being carried out, General MacArthur on 27 December declared Manila an open city to save the population from unnecessary suffering. His proclamation read:

In order to spare the metropolitan area from possible ravages of attack either by air or ground, Manila is hereby declared an open city without the characteristics of a military objective. In order that no excuse may be given for a possible mistake, the American High Commissioner, the Commonwealth government, and all combatant military installations will be withdrawn from its environs as rapidly as possible.

The Municipal government will continue to function with its police force, reinforced-by constabulary troops, so that the normal protection of life and property may be preserved. Citizens are requested to maintain obedience to constituted authorities and continue the normal processes of business.27

The Japanese discovered too late the strategy underlying the movement of General MacArthur's forces behind the curtain of the rear guard actions in Pampanga and Batangas. Driving with reckless fury, they strove desperately to cut the vulnerable road junction at San Fernando and the bridge defile at Calumpit. The year ended with the Japanese applying increasing pressure to the beleaguered American and Filipino forces.

[15]

The enemy is driving in great force from both the north and the south. His dive bombers practically control the roads from the air. The Japanese are using great quantities of tanks and armored units.Our lines are being pushed back.28

On 1 January General MacArthur announced the successful completion of the historic withdrawal:

In order to prevent the enemy's infiltration from the east from separating the forces in southern Luzon from those in northern Luzon, the Southern Luzon Force for several days has been moving north and has now successfully completed junction with the Northern Luzon Force. This movement will uncover the free city of Manila which, because of complete evacuation by our forces previously, has no practical military value. The entrance to Manila Bay is completely covered by our forces and its use thereby denied the enemy.30

General MacArthur regrouped his forces on Bataan into two corps, with I Corps under General Wainwright on the left and II Corps under Brig. Gen. George Parker on the right.31 As reorganization took place, the thousands of troops on the Bataan Peninsula began to dig in. New field artillery regiments were improvised in the field from miscellaneous elements to offset the enemy's great artillery superiority. While final delaying actions took place in the vicinity of Guagua, work went ahead on two runways near the southern tip of the peninsula to serve as a base for the

[16]

PLATE NO. 7

Action on Bataan

January-April 1942

[17]

remaining P-40's of the Far East Air Force. A hospital was set up near Cabcaben, and, because of the great number of civilians that had fled into Bataan with the army forces, refugee camps had to be established to keep them out of the way of military activities.

General Homma entered the city of Manila on 2 January 1942, but he had failed in his primary purpose, the annihilation of General MacArthur's field forces.

The baffled Japanese immediately launched headlong attacks against the first organized line of resistance, which ran from Moron to Abucay on the twenty-mile wide peninsula. They struck first on 12 January in the vicinity of Abucay, the eastern anchor. Initially successful, they were thrown back a few days later, only to strike again on 17 January in the Abucay Hacienda area, a little farther to the west. When unsuccessful there, they struck a third time on 20 January, still farther west in the II Corps sector. At the same time another Japanese force attacked Moron, the left anchor of the whole line, only to be repulsed. (Plate No. 7)

The hard-pressed defenders of this initial defense line on Bataan were finally forced to give ground. They were already beginning to suffer from malaria, and their daily rations, which had been sharply reduced, were to become even more meager as time went by.32 They were unable to prevent the Japanese from infiltrating across the steep jungle-covered slopes of Mt. Natib in the center of the general defense line. At the same time a fresh, coordinated Japanese attack on the left flank had succeeded in taking Moron. The constant pressure against I Corps was so heavy that the only possibility of preserving alignment was to effect a partial withdrawal and reorganization. II Corps also withdrew in order to maintain a continuity of front on the line from Bagac to Orion.

Although successful in forcing this first line on Bataan, the Japanese had suffered so many casualties that their initial efforts against the new Bagac-Orion line were ineffective. By the end of January General Homma in turn practically had to cease operations while awaiting substantial reinforcements.33 During this waiting period minor penetrations were made into the I Corps sector, but the raiding forces were pinched off and annihilated. A serious Japanese attempt to land from the

[18]

China Sea behind the American lines on the west coast of Bataan was likewise frustrated. These attacking forces were completely destroyed.34

The brilliant use of artillery, superbly placed for interdiction fire, and carefully timed counter-attacks had held the baffled and infuriated enemy at bay in a series of increasingly costly attacks. Attack and counterattack had serrated the opposing lines; Abucay had been lost and retaken; Moron had been lost and retaken, and lost again. For three bloody weeks, the line from Moron to Abucay had held, only to be swept back at last by the overwhelming Japanese tide. For many additional weeks, the line from Bagac to Orion had held steady.35 The enemy had begun to avoid bloody frontal attacks and to resort to landings on the west coast behind the American-Filipino lines, or to attempted penetration raids, to stab deep into the battle line, only to be sealed off and liquidated. If only help could have reached the Philippines, even in small force, if only limited reinforcement could have been supplied, the end could not have failed to be victory. It was Japan's ability to bring in fresh forces continually and America's inability to do so that finally settled the issue.

During this period of fighting President Quezon continued to carry on the government of the Philippines from General MacArthur's Headquarters on Corregidor. On 28 February he addressed a message to his people, praising their resistance and urging continued support of their Allies:

Almost three months have passed since the enemy first ravaged our sacred soil. At the cost of many lives and immeasurable human suffering we have been resisting his advance with all our might. He has taken our capital and occupied several of our provinces, but we are neither beaten nor subdued....

Our soldiers in the field and the civilians behind the lines are animated by one determination and one arm-to fight the invader until death and to expel him from our land....

For the last month, the enemy has failed to make any advance. Every attack he has launched against us has been repulsed and his losses have been mounting every day. Under the leadership of General MacArthur our men are valiantly doing their duty. We are holding our ground against overwhelming odds....

Already the gallantry of our soldiers has aroused the admiration of the whole world....The most glorious chapter in the history of our country is being written in Bataan and Corregidor on the epic stand of our armies....

I urge every Filipino to be of good cheer, to have faith in the patriotism and valor of our soldiers in the field, but above all, to trust America....

The United Nations will win this war. America is too great and too powerful to be vanquished in this conflict. I know she will not fail us.36

The resistance afforded by the American and Filipino forces against successive concentrations of superior strength in all components and branches had developed into an epic of courage and tenacity. The Philippines were

[19]

now entirely surrounded by the Japanese, who were north in Formosa and on the China coast, west in Indo-China, south in Borneo and the Netherlands East Indies, and east in the Marianas, Carolines, and Marshall Islands. The United States Navy, charged with the vital mission of maintaining and keeping open sea-borne supply lines to the Philippines, was unable to do so. This spelled the doom of the forces fighting there. The fall of Singapore on 15 February enabled the enemy to reinforce his units on Luzon, but the continuing resistance on Bataan denied the Japanese an essential base for the projected thrust to the South Pacific. The enemy was forced to retain large army and navy forces in the Philippines,37 which otherwise could have been employed against Allied shipping of men and materials to Australia and New Caledonia from the United States and the Middle East. As it finally developed, this enabled the barely sufficient preparations to be accomplished which saved those areas from what appeared inevitable invasion.

General MacArthur was not permitted to remain on Bataan or Corregidor to direct the last defense. Instead, he was ordered by President Roosevelt on 22 February to proceed to Australia to organize a new headquarters. On 11 March, in compliance with repeated orders, the General and selected members of his staff began the hazardous six-day journey by PT boat and plane through enemy-controlled areas to Australia from whence he was to launch the campaigns that would carry him not only back to Manila but on to the heart of the enemy's homeland-Tokyo.

General Wainwright assumed command of some 60,000 men remaining on Bataan and 10,000 more on Corregidor. Detachments cut off in northern Luzon, numbering about 2,000, continued to fight the enemy in guerrilla fashion.

General MacArthur's order of battle when he left for Australia was as follows:38

Bataan

1. From Bagac to Mt. Samat : Philippine I Corps (including the 11th Division of the Philippine Army; the 1st Regular Division and the 71st and 91st Divisions of the Philippine Army, each less one regiment; and the 45th Infantry and 26th Cavalry Regiments of the Philippine Scouts.)

2. From Mt. Samat to Orion: Philippine II Corps (including the 21st, 31st, and 41st Divisions and the 51st Combat Team of the Philippine Army; the Provisional Air Corps Regiment of the United States Army; and the Philippine Army Provisional Air Corps Battalion and Training Cadre Battalion.)Corregidor and the forts at the entrance to Manila Bay

1. The Harbor Defense Command under Maj. Gen. George F. Moore.

[20]

Visayas

1. The Visayan Forces under Brig. Gen. Bradford G. Chynoweth.Mindanao

1. The Mindanao Force under General Sharp.

His plans already formulated for the future conduct of operations on Bataan, were aimed at a fight to the end; they included attempts at opening supply lines from the southern portion of the Philippines and also a counterattack to capture the enemy base at Subic Bay.39 There was still the possibility that the defense could be protracted until the United States had time to recover from the first blows of the war and begin to send in supplies and reinforcements.

United States Army Forces in Australia

While the fighting in the Philippines was retarding the Japanese general advance, Australia was being prepared as a major Allied and United States base. A convoy en route to the Philippines from the United States at the outbreak of hostilities had been diverted to Australia. While at sea on 21 December, the troops were formed into Task Force South Pacific, and after debarking at Brisbane they were designated, on 5 January 1942, United States Army Forces in Australia (USAFIA). This expeditionary force was placed under the command of Maj. Gen. George H. Brett who was directed to establish a service of supply in support of the Philippines.

Plans had been formulated by the War Department for building an air force in Australia for the defense of critical points in the Southwest Pacific Area. The remaining heavy bombers-fewer than twenty-from General MacArthur's Far East Air Force had been moved south to Darwin and were already operating from Australia. General Brereton, in command of this force, was under instructions to protect lines of communication to the Philippines and furnish support for that operation, as well as to cooperate with the Navy and Allied forces in Australia and the Netherlands East Indies.

[21]

Allied strategy envisaged holding the Malay barrier (Malaya, Sumatra, Java, and northern Australia) while re-establishing communications with Luzon through the Netherlands East Indies. Burma and Australia were essential supporting positions. The former constituted the only remaining route for supplying China. The latter was to be the staging area for the reserves of manpower and materiel which would have to be shipped from the United States if the Japanese push were to be stopped. To carry out this strategic policy, the American, British, Dutch, and Australian Governments established a unified control over the area. The ABDA Command, as it was called, included Burma, Malaya, the Netherlands East Indies, and the Philippines within its jurisdiction. General Sir Archibald P. Wavell of the British Army was appointed Supreme Commander with headquarters in Java. All land, sea, and air forces of the participating governments in the area were directly under him as were also the supporting forces in Australia.

The mission of the United States forces in Australia became twofold: to get supplies through the Japanese blockade into the Philippines and to continue logistic support of the United States Army units in the Nertherlands East Indies. These were largely Air Corps units, including the heavy bombers of the Far East Air Force which had been shifted from Darwin to Java for their base of operations.40 General Brett left Australia to become Deputy Commander under General Wavell, and General Brereton was appointed Commander of the United States Operating Air Forces in the ABDA area. Maj. Gen. Julian F. Barnes assumed command of United States troops and facilities in Australia.

It was evident that Japanese seizure of the entire region from Burma to Australia could not be long delayed;41 at every point the Allied forces were inferior in strength. General Wavell's Headquarters were dissolved on 28 February, and he departed to organize the defenses of India. General Brett returned to direct the United States Army Forces in Australia, and the command in Java passed to the Dutch who prepared for a final stand.42

A desperate but futile effort to halt the Japanese was made in the Java Sea on 27 February. An Allied force of five cruisers and nine destroyers under the command of Rear Adm. Karel W. F. Doorman of the Royal Netherlands Navy moved out to intercept the approaching invasion forces. In the resulting action, the Allied fleet suffered a crushing defeat. The enemy immediately proceeded with landings on Java and overcame major resistance by 9 March. Tokyo thereupon announced the completion of the conquest of the Netherlands East Indies. The announcement followed by one day the fall of Rangoon and the cutting of the Burma supply line to China.43

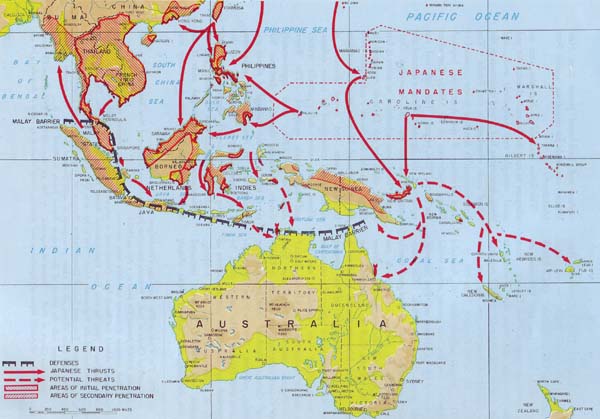

To the east the Japanese were soon established in the southern Solomons, at Rabaul and Gasmata in New Britain, and at Kavieng

[22]

in New Ireland. They had extended their control of the Central Pacific by the occupation of the Gilbert Islands. On 8 March enemy forces seized Lae and Salamaua on the northeast coast of New Guinea. From these positions and from the Netherlands East Indies, the Japanese directly menaced the security of Australia and the sea lanes through the South Pacific.44 (Plate No. 8)

The Allied commanders in Australia considered that the next enemy moves would be directed against Darwin and Port Moresby, both already under air attack. The occupation of Darwin might be designed merely to deny it to the Allied forces or as one stage in a general offensive against northwest Australia and the Gulf of Carpentaria. An attack on Port Moresby would eliminate it as a threat to the flank of an advance from Rabaul southward against the east coast of Australia or New Caledonia and the sea and air routes from the United States.45

Intelligence reports indicated that there were at least nine Japanese divisions in Dutch New Guinea, Ambon, Makassar, Timor, Celebes, and Java. Two or more were available to seize Darwin. The attack could be supported by about four aircraft carriers as well as shore-based planes from Koepang, Ambon, and Namlea. A force estimated at one division, with two or three aircraft carriers and land-based planes from New Britain, was ready for operations against Port Moresby.46

The forces available in Australia were inadequate to meet the Japanese threat. Air and naval strength were particularly weak, and these deficiencies had proved disastrous to the Allied cause elsewhere in the Pacific. The Commonwealth's first line troops consisted of three divisions of the Australian Imperial Forces which were in the Middle East when the Pacific War began. This fact and the rapidity of the Japanese offensive dictated the return of the 6th and 7th Australian Divisions. They were scheduled to arrive in late March, while the 9th Division remained in Egypt. In the Southwest Pacific there were the 1st Armored Division of the Australian Imperial Forces and several divisions of militia troops conscripted for home defense. These units were only partially trained and inadequately equipped. The Royal Australian Air Force had approximately sixteen squadrons classed as first-line, but there was a serious shortage of planes and trained crews in some of these squadrons. They were equipped, in general, with inferior types of aircraft which limited their capabilities to small-scale bombing and reconnaissance.47 The principal units of the Royal Australian Navy were two heavy and

[23]

PLATE NO. 8

Disintegration of the Malay Barrier and the Threat to Australia

[24]

PLATE NO. 9

Orientation Map Showing the Lack of Rail Transportation along the Vulnerable Northern Coast

[25]

two light cruisers.

Limitations of manpower and productive capacity severely restricted expansion of the Australian armed forces and made support from overseas essential.48 The War Department in Washington planned to bring to full strength the two heavy bomber groups, two medium bomber groups, one light bomber group, and three pursuit squadrons already in Australia and to provide additional fighter units. With the exception of field artillery and antiaircraft elements, there were no United States ground combat forces, but the 41st Division was to arrive in April, and another division had been promised if the Australians permitted one of their divisions to remain in the Middle East.49

The combined United States and Australian forces were obviously insufficient for the protection of the whole of a vast continent, almost equal in size to the United States and with a coast line 12,000 miles in length. Concentration in any area to oppose Japanese landings was exceedingly difficult because of the great distances to be covered and the inadequate transportation facilities. The road and rail network of Australia was of limited capacity and of varying gauges and did not permit the rapid movement of troops. Principal routes frequently paralleled the coast and were vulnerable to amphibious attack. Darwin possessed no rail connection with the rest of the country. Port Moresby and Tasmania depended solely upon sea lines of communication and their control by friendly air and naval forces.50 (Plate No. 9)

The Australians disposed the bulk of their forces in the general region around Brisbane and Melbourne where most of the industries, the principal food producing centers, and the best ports, were located. The area was all-important to the country's war effort, and its defense was the prime consideration of its military authorities.51

Small forces were stationed in Tasmania and Western Australia and at Darwin, Port Moresby, Thursday Island, and Townsville. Because of their relative isolation, the retention of these points on the outer perimeter depended largely upon their garrisons, none of which was strong enough to oppose a major assault successfully. Reinforcing them was impossible, as additional troops could be drawn only from the vital southeastern region which, in the opinion of the Australian Chiefs of Staff, was itself inadequately held. Withdrawal from the outlying areas was equally out of the question. Their importance warranted an effort to hold them as long as possible, and the destructive effect of such an evacuation on public morale also had to be considered. The return of the 6th and 7th Divisions and the expected arrival of a division from the United States would allow the strengthening of the forces at Darwin, Western Australia, and Tasmania. The Australians, however, planned to retain two of these units

[26]

to increase the reserve in the Brisbane-Melbourne zone.52

Coordination of the United States and Australian forces which manned the defense was achieved through cooperative effort and a system of joint committees established early in January.53 So long as the continent had not been directly threatened this was adequate, but by the middle of March the Japanese were approaching the doorstep of Australia. Darwin, the only port on the northwest coast, had already been severely bombed. Townsville had also been subjected to air raids. With each passing day the Japanese were forging new links in their chain of encirclement and preparing new strikes against Australia and her life line to the outside world. The organization of a combined Allied defense under a single directing authority had become a matter of urgent necessity. Proposals concerning the organization of a new area of command had been made early in March by the Australian and New Zealand Governments. A decision concerning these proposals was the next important problem facing the governments engaged in this theater of the war. Final action awaited the safe arrival of General MacArthur from the Philippines.

[27]

Go to: |

Last updated 20 June 2006 |