CHAPTER III

HALTING THE JAPANESE

Following the capture of Lae and Salamaua by the Japanese, General MacArthur unhesitatingly discarded the prevailing concept of a purely passive defense of Australia and decided to achieve his mission by offensive operations in New Guinea.

The meager resources at his disposal necessarily limited the scope of such actions, but by striking boldly at the enemy's weak points and avoiding frontal engagements in force, he expected to upset the enemy's timetable and frustrate his plan to occupy southeastern New Guinea. Relying on tactical maneuver, the exploitation of terrain factors, and an increasing flow of intelligence, the General planned to operate with maximum striking power in order to reduce the loss of life and materiel to a minimum.

When the Japanese temporarily halted their advance toward Australia, they controlled the entire chain of islands which lie across its northern sea approaches, with the single exception of southeastern New Guinea. These forward positions formed a front three thousand miles long, extending from Java to the Solomons. Interior sea and air lines of communication, radiating southward from Japan through intermediate supporting bases from Singapore to Formosa and to Truk, permitted easy concentrations for further offensive moves. The western and northern coasts of Australia to the Torres Straits were directly exposed to Japanese operations from the Netherlands East Indies. In addition to these geographic advantages, the Japanese held the initiative as to the point of attack.

In April reinforcements dispatched to III Corps in Western Australia and to Northern Territory Force at Darwin raised each to division strength, plus certain auxiliaries. Small air force elements were maintained in each locality and airdrome facilities were expanded in order to accommodate major striking forces for projected operations as the center of gravity of the Allied air forces moved forward. Naval protection at this time was limited to two light cruisers and a number of destroyers and submarines based at Fremantle.

After the Japanese occupation of Rabaul and the New Guinea coast, the most pressing danger facing General MacArthur was a potential enemy thrust to Port Moresby in preparation for a drive against Australia. Consistent with his strategy of defending Australia in New Guinea, General MacArthur decided to strengthen immediately the Allied position in Papua and develop Port Moresby as a major air and land base.

Port Moresby, flanked on the east by Milne Bay and protected on the north by the formidable 14,000-foot Owen Stanley Range, was well placed strategically. Except for its vulnerability to amphibious assault, it was ideally situated for future air operations against enemy

[45]

positions to the north and the northeast. A strong base in this region would not only serve to protect Australia from hostile raids but also provide the starting point on the road back to the Philippines-the heart of the enemy's supply and communications network in his newly conquered empire.

Constant enemy air raids and the lack of adequate airdrome facilities made Port Moresby virtually untenable for big bombers except as a forward fueling point. The nearest supporting airfields were at Townsville, 700 miles to the south. To strengthen his Port Moresby base, General MacArthur planned to move his bombers into more forward positions. A program of airdrome construction was undertaken in Australia, first expanding installations in the Townsville-Cloncurry area, then building north along the York Peninsula. This development was in its early stages when, at the end of April, the presence of a large Japanese naval force in the Mandated Islands and concentrations of aircraft in the New Britain-Solomons region indicated that the enemy was about to renew his offensive. To meet this threat, General MacArthur ordered the Allied Air Forces to intensify their reconnaissance, to assemble a maximum striking force on the TownsvilleCloncurry airfields, and to bomb enemy positions. During the first week in May the important stronghold of Rabaul was attacked repeatedly. Missions were also sent against Lae, Buka and Deboyne Islands, and enemy convoys in adjacent waters. Garrison commanders in northeastern Australia and at Port Moresby were alerted to the possibility of landings in their respective areas.1 Allied Naval Forces (SWPA) dispatched three cruisers to augment the Pacific fleet units which already included the aircraft carriers Lexington and Yorktown. Every measure was taken to check the threatened enemy advance.

The Allied countermeasures were soon justified. Eight days after General MacArthur had issued orders for the all-out alert, the Japanese made their first move. On 3 May an enemy naval force made an unopposed landing at Tulagi Harbor in the southern Solomons.2 The next morning, however, the Yorktown, which had been refueling at Espiritu Santo, made a high speed run north and launched its planes in three strikes against harbor shipping, crippling a destroyer and three or four small boats. It then returned southward to rejoin the Lexington. While the occupation of Tulagi was being carried out, the main force of the Japanese Fourth Fleet was completing its final preparations for a full scale amphibious invasion of Port Moresby. The decision to take Port Moresby had been made on 29 January and specific orders to the 5th Carrier Division were issued in the middle of April. The landings were to take place on 10 May.3

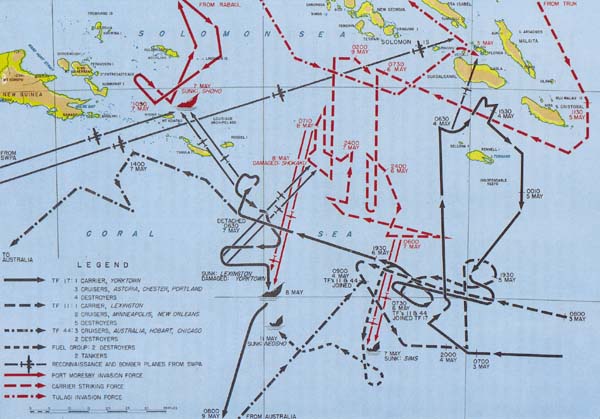

On 1 May, a strong fleet of Japanese warships, including the carriers Zuikaku and Sho-

[46]

kaku of the 5th Carrier Division, had left Truk to follow a route through the Mandated Islands around San Cristobal and into the Coral Sea. (Plate No. 14) The main missions of this task force were to protect the Port Moresby landing group and to engage the Allied Fleet which was expected to appear on the scene.

Meanwhile, the Japanese South Seas Detachment, a veteran unit which had already taken Guam, Rabaul, and Salamaua, had been designated as the invasion landing force under Maj. Gen. Tomitaro Horii. This group, loaded on approximately 12 transports, departed from Rabaul on 4 May escorted by 1 light cruiser and 6 destroyers and also supported by the carrier Shoho and four heavy cruisers.

Long-range, land-based bombers from General MacArthur's Command were combing the area for the Japanese convoy but failed to locate it either that day or the next.4 On the 5th, however, Allied intelligence reported that Port Moresby was the main enemy objective and that landings could be expected any time between 5 May and 10 May.5 B-17's and B-26's of the Southwest Pacific Area stood by on the alert to attack while other planes carried out neutralizing raids to keep enemy land-based air power from participating in the coming battle. It was not until late on the 6th, however, that three B-17's on reconnaissance duty finally located the Japanese invasion force headed for the Jomard Passage and the Louisiade Islands. Rear Adm. Frank J. Fletcher, Commander of the Allied Fleet, dispatching a group of cruisers and destroyers to cover the Jomard Passage, moved north with his carrier force to contact and close with the main enemy fleet.

On the morning of 7 May, army scout planes reported sighting an enemy carrier, which proved to be the Shoho, off Misima Island. Ten B-17's immediately were sent to the attack. They were generally unsuccessful in their high level bombing, but were able to start fires on one cruiser and, by throwing the Japanese formation into complete disorder, they caused the carrier to reverse its course. Flyers from the Lexington and the Yorktown arrived shortly thereafter catching the Japanese in a state of unpreparedness, with but few planes in the air and with their carrier headed away from the wind.6 Nine bomb hits and four torpedoes sank the Shoho within five minutes after the first blow was scored. A second strike at the retiring enemy force was readied but not ordered aloft because the other Japanese carriers had not yet been located.

The undiscovered Shokaku and Zuikaku were at this time to the northeast busily searching for the United States carriers. Reconnaissance planes from these two enemy ships misdirected a heavy attack against a group of oil tankers, mistaking them for a carrier task force. Admiral Fletcher did not learn of this attack until dusk, too late to take any effective counteraction.

The Japanese learned of the sinking of the Shoho as their planes were returning from the attack on the tanker group, and at dusk about twenty-seven bombers and torpedo planes again left the Shokaku and Zuikaku in another effort to locate and sink the Lexington and the Yorktown. After a fruitless search of almost 300 miles, the planes were forced to jettison all bombs and torpedoes and swing back to their ships. During the return flight, these planes passed over the United States carriers at night and some landings were actually attempted before the Japanese pilots realized their mistake.

Both sides initiated all-out attacks on 8 May.

[47]

PLATE NO. 14

Battle of the Coral Sea

[48]

About mid-morning, United States carrier planes scored three hits on the Shokaku which was forced to retire. At the same time that the Shokaku was undergoing attack, planes from the Shokaku and Zuikaku were attacking the Lexington and Yorktown. Early in the afternoon the Lexington, put out of control by enemy attacks, was abandoned and sunk by its own destroyer escorts. The Yorktown was damaged but remained operational. This exchange terminated one of the most unusual battles in the annals of naval warfare. Not only was it the first engagement between carrier forces in history but surface ships did not exchange a single shot throughout the entire battle.7

In addition to reconnaissance and preparatory raids against enemy air installations, land-based aircraft from the SWPA supported the action of the naval forces by flying some forty-five sorties against the enemy fleet. Bad weather intervened, however, and frustrated all attempts to bomb the crippled Shokaku, which succeeded in escaping to the sanctuary of Rabaul.8

The Battle of the Coral Sea prevented the Japanese from occupying Port Moresby by sea and temporarily delayed their plans to capture Guadalcanal and occupy the Solomons.9 The race against time by the Allies had now become a split-second effort to develop the northeastern Australia-New Guinea area. The construction of airdromes at Cairns, Cooktown, Coen, Horn Island, and Port Moresby was pushed rapidly, and small garrisons were provided for the airdromes on the York Peninsula and at Port Moresby. On the other hand, the Allied victory was a purely defensive one. Allied forces in the Southwest Pacific were still unable to launch a major offensive. The Japanese had lost an important battle, but the strategic initiative still remained in their hands.10

Kanga Force was formed in April 1942 to harass and interrupt the development of the Japanese bases at Lae and Salamaua. This force consisted of a small formation of local Europeans known as New Guinea Volunteer Rifles, and a reinforced Australian Independent Company.11 A part of the force was already at Wau, a prewar gold mining town in the Owen Stanleys, from which trails led to Lae and Salamaua. Additional troops were flown in from Port Moresby during the latter part of May.

At the beginning of May, General MacArthur suggested to General Blamey that ground raids be initiated against Lae and Salamaua to destroy enemy installations and, if possible, to occupy the airfields.12 If Lae

[49]

and Salamaua could be denied to the enemy for a limited period and the airfields used by Allied pursuit planes, valuable time would be gained for strengthening the defenses at Port Moresby.

Toward the end of May, as Kanga Force was making preparations to launch raids on Lae and Salamaua, scout reports indicated that the Japanese themselves were about to move into the Bulolo Valley against Wau. The Kanga Force Commander, Maj. N. L. Fleay, was committed to the defense of the important air installations at Wau, but with the small force available he was unable to protect the airfields and at the same time carry out offensive operations against Lae and Salamaua. The raids, therefore, were postponed for a later date.

The planned attacks were finally made at the end of June and although some damage and casualties were inflicted on the enemy, no decisive results were obtained. Kanga Force was maintained at Wau after these raids under almost prohibitive conditions to continue the protection of air facilities and to secure the crest of the Owen Stanleys in that area.

While the Southwest Pacific Area was thus engaged, another naval battle was being fought in the Central Pacific that considerably altered the general strategic situation. Soon after the retirement of the Japanese from the Coral Sea, a powerful concentration of enemy naval forces in home waters was reported. The United States Pacific Fleet prepared to meet an attack eastward. On 3 June the enemy was sighted southwest of Midway Island. Beginning that afternoon and continuing for the next three days, land-based planes from Midway and carrier aircraft from the Yorktown, Enterprise, and Hornet repeatedly battered the

Japanese ships, sinking four aircraft carriers and one heavy cruiser. One heavy cruiser was severely damaged in addition to two destroyers. American losses were light, consisting of the Yorktown and one destroyer. Again, as in the Battle of the Coral Sea, the opposing warships never once sighted each other and not a single direct shot was exchanged. The dominant role of air power in naval warfare was now clearly demonstrated.

This decisive victory restored the balance of naval power in the Pacific and automatically removed the threat to Hawaii and the west coast of the United States. Thereafter, except for the Aleutians where the Japanese had landed on Attu and Kiska Islands, enemy operations were confined to the South and Southwest Pacific Areas.

Whereas the Battle of Midway compelled the Japanese to concentrate their attention on the New Guinea area, the Battle of the Coral Sea had pointed to the strategic importance of Milne Bay. It convinced the Japanese that a base at that location would be invaluable for the air support of any future convoy rounding the southeastern tip of Papua. It also disclosed another line of approach to Port Moresby-the coastal trails along which ground troops could infiltrate to divert Allied strength from its defenses and to reinforce Japanese troops attacking over the Owen Stanley mountains.

General MacArthur was equally aware of the strategic potentialities of Milne Bay. He fully realized not only its importance to the enemy but also its value to his own scheme of offense. While affording a powerful barrier against any Japanese attack, the Owen Stanley mountains also presented an obstacle to Allied advance. An Allied base at Milne Bay would

[50]

pave the way for a move around the end of New Guinea and along the Papuan coast to Buna and thence to the main objectives of Lae and Salamaua, avoiding the mountains entirely. With Milne Bay in Allied hands, the east flank of Port Moresby would be secured.

Accordingly, in June General MacArthur ordered the secret construction of an air, land, and naval base at Gili Gili located at the head of Milne Bay.13 The move along the coast to the site of the projected base, known as Operation Fall River, was made secretly and skillfully so that the initial execution of the plan was unhampered by enemy opposition. Had the Japanese been aware of General MacArthur's intention to fortify Milne Bay, they would have made every effort to prevent its fulfillment. This was clearly demonstrated by the fury and determination of their counterattacks as soon as they learned that he had beaten them to that all-important position.

In addition to the cover afforded by the air forces at Darwin and on the York Peninsula, General MacArthur directed the construction of an airdrome at Merauke on the southern coast of Dutch New Guinea as a further protection to his west flank.14 Although the project had to be temporarily suspended in August because the engineer effort was required elsewhere, a garrison of one infantry company and auxiliaries was kept at Merauke to deny its use to the Japanese.

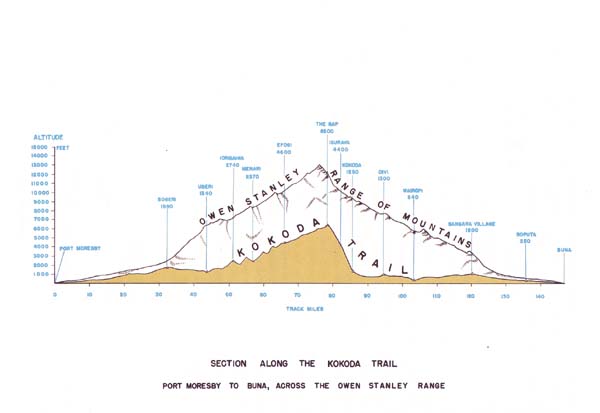

General MacArthur also anticipated enemy efforts along the Kokoda Trail, the only passable route across the mountains from Buna on the east Papuan coast to Port Moresby. (Plate No. 15) He was convinced that the Japanese intended to employ this route either to assault Port Moresby directly or as a supply base for a possible amphibious force attacking by sea through the Louisiade Archipelago. To forestall such a move, he asked General Blamey to advise him of the plan of New Guinea Force for the protection of Kokoda and the points along the trail.15 General MacArthur's estimate of the enemy's intention was strikingly correct. Three days after this query to General Blamey, Imperial Japanese Headquarters ordered the commander of the Japanese Seventeenth Army to co-operate with the Navy and "immediately make land attack plans against Port Moresby."16

On 21 June, the Australian Maroubra Force,

[51]

PLATE NO. 15

Section along the Kokoda Trail

[52]

consisting of the Papuan Infantry Battalion and a battalion of the 30th Brigade, was organized for concentration at Kokoda on the northern slopes of the Owen Stanleys northeast of Port Moresby. It was directed to prevent an enemy penetration of the mountains along the route of the Kokoda Trail.17 The Papuan Infantry Battalion, about 280 native troops with white officers, was already north of the range and a company of the brigade started forward overland in early July. The remainder stayed at Port Moresby to assist in the strengthening of the southern terminus of the Kokoda Trail, and to reinforce the advance detachment if necessary.

In addition to defending the passes along the Owen Stanleys, General MacArthur worked out a plan for the occupation of key points along the Kokoda Trail from Port Moresby to Buna. This plan, designated as Operation Providence, called for an overland force to proceed from Port Moresby to Buna. Upon arrival at Buna this force would meet a light convoy proceeding up the coast from Milne Bay. The commander of the overland expedition, utilizing the supplies and equipment of this light convoy, would then form a beachhead to cover the landing of a second and main convoy proceeding from Milne Bay. According to this plan, the main convoy would contain the personnel for airdrome construction and garrison units and also necessary supplies.18

General MacArthur's plan to penetrate deeply into the difficult and largely unknown terrain held by the Japanese required special preparation and the collection of new information. New Guinea was a wilderness compared with Western Europe where professional armies in being for over a century had left a rich heritage of military and topographical information. The amount of material on the geography and topography of New Guinea and adjacent areas, however, was inadequate; available hydrographic charts were old and faulty, and data on health and climatic conditions peculiar to these regions were meager. Information concerning the activity of the enemy, his strength and dispositions, his combat methods and current equipment, and his actual relationships with the natives was imperative. Such intelligence would have to be obtained by secret operations behind the enemy lines and from other sources.

General MacArthur directed that special agencies be developed to provide him with this information.19 On 19 July 1942 the Allied Geographical Section (AGS) was formed to assemble and evaluate all geographic information regarding the Southwest Pacific Area. The primary task of the new section was to prepare and publish reports and locality studies on the areas of immediate tactical interest in

[53]

New Guinea, New Britain, New Ireland, and the Solomons. Subsequently, more extensive "Terrain Studies" were issued to all planning staffs, supplemented by pocket-size "Handbooks" supplied to troops in the field, down to platoon commanders, as a sort of individual "Baedeker" for the assault echelons when they hit the landing beaches.20

The Allied Intelligence Bureau (AIB) was established in July 1942 to collect intelligence through clandestine operations behind enemy lines. A secondary function was to conduct sabotage operations and to secure co-operation and aid from the natives in fighting the Japanese. The Bureau incorporated several previously existing agencies and absorbed the Royal Australian Navy's "coast watching" system. It dispatched agents and radio transmitters by submarine and established stations ranging from Bougainville to Borneo, from Papua to Palawan. This organization performed invaluable service in giving immediate reports by radio on Japanese plane and ship movements in the area from the Solomons to New Ireland, New Britain, and the mainland of New Guinea. (Plate No. 16) This information enabled Allied planes to be ready and in the air at a time when the Allies were relatively weak in air power. Operational areas of New Guinea were explored by parties sent in by AIB to ascertain Japanese strength, activities, and movements. Intelligence was radioed for strategical use directly to local force commanders, Air Force units, and the Navy, as well as to AIB Headquarters in Brisbane and Port Moresby. The coastal waters between Milne Bay and Buna were sounded, charted, and marked by secret buoys to guide the transports of proposed landing operations.21

Experience on Bataan with a handful of Nisei interpreters had clearly shown the potentialities of a competent interrogation and

[54]

translation service. Out of this experience grew one of General MacArthur's most important single intelligence agencies-the Allied Translator and Interpreter Section (ATIS) which was organized on 19 September 1942. Invaluable results were achieved by ATIS personnel in neutralizing one of the greatest advantages possessed by the Japanese-a language which was almost as effective as a secret code. The Japanese had found early in the war that they could label their mine fields, carry personal diaries, use their spoken language freely, and even handle military documents with little regard for security.

With complete confidence in the Nisei, G-2 employed hundreds of second-generation Japanese from Hawaii and California in linguist detachments, to be sent into the field with the combat forces. ATIS intelligence teams accompanied the troops in all initial landing operations. Captured maps and orders processed by ATIS revealed enemy strength and dispositions and plans of attack. Diaries contained excellent clues to the psychology and the state of morale of the Japanese troops. Other documents indicated the enemy's problems of food and supply, his order of battle, the effect of our air attacks, his relations with the natives, the relative effectiveness of Allied and Japanese weapons, and other equally important data. Spot interrogations of prisoners taken in battle were at times of such importance that they caused a shift in Allied plans of attack. ATIS provided information of immediate operational as well as over-all strategic value.22

These intelligence agencies combined to furnish the SWPA with its own Office of Strategic Services. As the war progressed they were enlarged and co-ordinated to meet the immediate needs of each new tactical and strategical situation. By using this weapon of superior intelligence, General MacArthur was in a position to gain the greatest strategic advantage in the shortest time with minimum losses.

General Headquarters Transferred to Brisbane

On 20 July, General MacArthur transferred his entire headquarters from Melbourne to Brisbane, and drew with it forward echelons of all component forces-Ground, Air and Navy. Brig. Gen. Richard J. Marshal replaced General Barnes in command of United States Army Forces in Australia, which was redesignated United States Army Services of Supply, and Maj. Gen. George C. Kenney relieved General Brett as Commander, Allied Air Forces.

The Allied successes in the Coral Sea and at Midway created a new situation which, General MacArthur urged, should be exploited by immediate offensive action. In a radio to the War Department on 8 June, he outlined his plans and recommendations and emphasized

[55]

PLATE NO. 16

Coast Watching Teleradio Stations

[56-57]

the necessity of speed in their execution:

The first objective should be the New Britain-New Ireland area, against which I would move immediately if the means were available; have the 32nd and 41st Infantry Divisions and the 7th Australian Division which can be used in support of a landing force, but which cannot be employed in initial attack due to lack of specialized equipment and training; naval component excellent, but lack integral air elements; recommend 1 division trained and equipped for amphibious operations and a task force, including 2 carriers, be made available to me at earliest practicable date; with such a force I could retake that important area.... speed is vital; not possible for me to act quickly if I must build equipment and train my divisions; cannot urge too strongly that the time has arrived to use the force, or a portion of it, which you have informed me to be 40,000 men on the west coast (USA) trained for amphibious operations, and could be employed in conjunction with the forces available to me in the initiation of offensive operations in the SWPA.23

On 24 June General MacArthur elaborated on his plan for an offensive along the northeast coast of New Guinea and in the New Britain-New Ireland area. He stressed the important strategic principles of concentration of forces and the selection of objectives which could be held once they were won. An operation against Timor had been proposed, but General MacArthur doubted whether Timor could be held in proximity to strong Japanese bases in the Netherlands East Indies and with the Japanese in complete control of the adjacent sea areas. He was opposed to any division of the Allied effort and, rather than dissipate limited strength in various areas, he proposed a single unified drive under united command:

Impracticable to attempt the capture of Rabaul by direct assault supported by the amount of land-based aviation now available; my plan contemplates a progressive movement, involving primary action against the Solomons and the north coast of New Guinea, in order to protect the naval surface forces and to secure airfields from which essential support can be given to the forces participating in the final phase of the operation; necessary that all ground operations in this area be under my direction; to bring in land forces from other areas with a view to their operation under naval direction exercised from distant points can result in nothing but complete confusion; the very purpose of the establishment of the Southwest Pacific Area was to obtain unity of command.... the action projected northwest of Australia, [attack on Timor] even if successful, cannot be supported as is the case in the New Britain area; doubtful whether Timor could be held under present circumstances in view of nearby Japanese bases and their control of the sea; its capture should not be undertaken unless we are prepared to support it fully which includes the continuous control of the sea lane between there and Australia; the situation is entirely different in the New Britain-New Ireland area, which if captured can unquestionably be held; no effort from the northwest coast of Australia should be made until naval and air forces are built up which will insure retention of objectives....

If correct [command] procedure is not followed it makes a mockery of the unity of command theory, which was the basis of the organizational plan applied to the Pacific Theater.24

On 2 July, the Joint Chiefs of Staff issued a directive under which Admiral Ghormley was assigned the conquest and garrisoning of the Santa Cruz Islands, Tulagi, and adjacent positions.25 General MacArthur's task was to capture the remaining Solomon Islands, and also Lae, Salamaua, and the northeast coast of New Guinea. The target date for

[58]

the first operation against the Solomon Islands was set as 7 August.

The task would not be easy. The enemy was bringing large reinforcements into the region of the projected offensive and was intensifying his efforts to complete airdromes at the key points of Kavieng, Rabaul, Lae, Salamaua, Buka, and Guadalcanal.26 The Allies, on the other hand, lacked trained amphibious forces; they were short on shipping facilities and airfields; and they needed experienced pilots and more planes to counter Japanese power.27

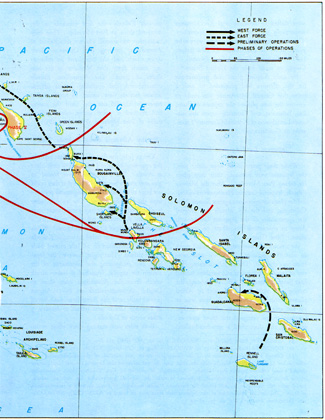

Plans for the offensive, however, were rushed. Operation Tulsa Two B envisioned two drives. (Plate No. 17) One force would proceed generally along the north coast of New Guinea securing in succession Lae-Salamaua-Gasmata, Cape Gloucester-Talasea-Madang, and Wewak -Lorengau. The other force would follow along the Solomons to New Ireland seizing Faisi-Kieta-Buka and Kavieng. In addition to his operations in New Guinea, General MacArthur prepared to support the attack on Guadalcanal by interdicting hostile air and naval activities in the area west of the Solomons.28

Air force units were meanwhile being moved into Cape York Peninsula and New Guinea as rapidly as the completion of airdromes and limited shipping allowed. By 19 August four airfields had been completed at Port Moresby, one for heavy bombers, one for medium bombers, and two for fighters. Two more heavy bomber fields and one for medium bombers were expected to be ready by 5 September. At Milne Bay, one field, already in operation for pursuit planes, was to be ready for heavy bombers by 25 August, and two other heavy bomber strips were under construction. On Cape York Peninsula two fields for heavy bombers and one for-fighters were completed, with three additional heavy bomber fields planned for September. Adequate service facilities had been completed in the Townsville-Cloncurry area.

The acceleration of air movements and the construction of air establishments is an early characteristic of General MacArthur's strategy in three-dimensional warfare. His complete air mindedness is demonstrated by the principle of moving his bomber line forward: (1) advancing in successive bounds, (2) establishing forward airfields, and (3) making the next move under cover of his own air umbrella.29

The United States 32nd and 41st Divisions

[59]

PLATE NO. 17

Tulsa Two B

[60-61]

were shifted to Brisbane and Rockhampton respectively, to train for offensive operations. These divisions, formed into a corps, were to be placed under the command of Lt. Gen. Robert L. Eichelberger, Commanding General, I Corps, en route from the United States.30

By early August, plans and preparations for the offensive had proceeded to such a point that General MacArthur was ready to execute the first phase-the capture of Buna, Lae, Salamaua, and Gasmata-upon the successful conclusion of Admiral Ghormley's operation at Guadalcanal.31

While these preparations were under way, the Japanese were pursuing their own plans for taking Port Moresby. After the Midway debacle, Imperial General Headquarters cancelled the plans for operations against Samoa, New Caledonia, and the Fiji Islands and ordered the commander of the Japanese Seventeenth Army to concentrate his efforts on securing eastern New Guinea.32

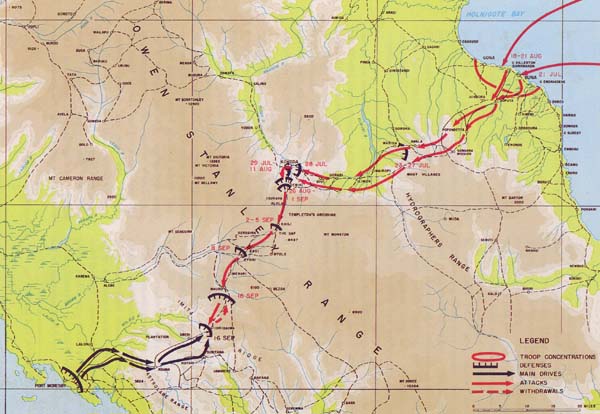

As a result of these orders, the Allied move to execute Operation Providence and seize Buna was checked. On 21 July, a strong convoy of Japanese transports and warships landed near Basabua northwest of Buna. Although the convoy was sighted and attacked by Allied planes, General MacArthur's air force was as yet too small to effect any serious damage. Japanese troops occupied the Buna area immediately and dispatched a spearhead inland towards Kokoda-the first elements in the overland drive to Port Moresby. Their only opposition was a small advance detachment of Australians, carrying out Operation Providence, which had just completed an exhausting march from Port Moresby to the outskirts of Buna. The Australians, heavily outnumbered, and operating against adverse terrain factors, were forced to begin a slow retreat which did not stop until the enemy had reached a point within twenty airline miles of Port Moresby. (Plate No. 18)

Enemy Advance along Kokoda Trail

On 23 July, the first ground action between the opposing forces in New Guinea took place at Awala. The Australians were forced to give way after it became obvious that they could not hope to withstand increasing enemy pressure from the beachhead area. On 25 July, after breaking out of an enemy encirclement near Oivi, the Australians fell back to Deniki, a few miles south of Kokoda airdrome. When the Japanese at first failed to occupy Kokoda itself, the Australians on 28 July moved back to the airfield. That night, however, the Japanese, also recognizing the importance of the airstrip for supply, launched a heavy attack which drove the Australians once more to Deniki. A counterattack on 10-11 August proved futile, and the Australians were forced to evacuate Deniki and retreat to Isurava, 3 miles south of Kokoda.

Both sides were making every effort to in-

[62]

crease their strength at this stage. The Australians planned to build Isurava into a base from which they could attack and reoccupy Kokoda. Once in possession of the airstrip on the Kokoda plateau, they could receive air reinforcements from Port Moresby and drive the Japanese back to the coast. The Japanese likewise planned to build Kokoda into a large forward supply base. As companies of Australian infantry were trickling through the Owen Stanleys to bolster the battle-weary forces at Isurava, the Japanese were dispatching troops from Rabaul for the final all-out drive on Port Moresby. The main strength of the South Seas Detachment had arrived at Basabua, near Buna, during 13-21 August under orders to proceed to Port Moresby. On 18 August, Lt. Gen. Sidney F. Rowell replaced Maj. Gen. Basil M. Morris as Commander of New Guinea Force. Maj. Gen. Arthur S. Allen was put in charge of the Australian 7th Division and made responsible for operations on the Kokoda Trail. The troops at Isurava had been reinforced by the 2nd Battalion of the 30th Brigade and two battalions of the 21st Brigade.

By 26 August, the date on which the Australians were to have launched their counterattack, the enemy himself was applying heavy pressure on Isurava. Outflanked and outnumbered, the Australians were pushed back along the trail. Attempts to supply them by air were abortive as supplies were either smashed or lost in the air drops. The reinforcements which were to have ousted the Japanese from Kokoda were now forced to assume the defensive and to help extricate the battered remnants of the forces retreating from Isurava. General MacArthur was faced with the grim task of halting a Japanese drive which, if successful, would not only disrupt the Allied timetable in the southwest Pacific but could mean an eventual struggle for Australia itself.

Admiral Ghormley launched his scheduled attack against the Solomons on 7 August when the 1st Marine Division, reinforced, went ashore at Tulagi and on Guadalcanal. Three aircraft carriers were among the participating naval units, which also included several cruisers and destroyers temporarily assigned to Admiral Ghormley's control from General MacArthur's naval forces. General MacArthur did everything in his power to assist the landing operation and to support the Solomons offensive. Submarines were dispatched to operate in the vicinity of Rabaul, reconnaissance was intensified, and air attacks against enemy airfields and shipping were pressed vigorously. All planes capable of the range were directed against Rabaul, Buka, and Kieta while others struck at Lae and Salamaua. Land operations in New Guinea were also intensified to relieve the pressure on the Solomons.33

The Marine landings at Tulagi and Guadalcanal took the enemy garrisons by surprise. At the end of the second day, the Marines were in complete control of Tulagi and held the airfield on Guadalcanal, the immediate objectives of the operation. The Japanese, however, struck back viciously by sea and air from their bases in the northern Solomons and the Bismarck Archipelago. On the night of 8 August, hostile surface units entered the area between Guadalcanal and Florida Island undetected and sank the cruisers Canberra, Quincy, Vincennes, and Astoria, and badly damaged the Chicago and two destroyers. Enemy land-based planes began bombing Marine positions during daylight hours and submarines were active against the American lines

[63]

PLATE NO. 18

Japanese Thrust toward Port Moresby

[64]

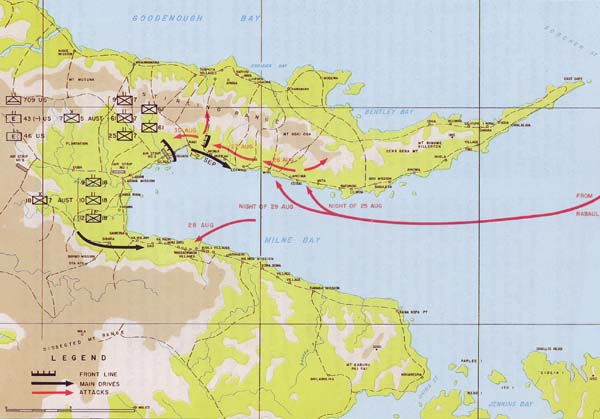

PLATE NO. 19

Enemy Landings at Milne Bay, August 1942

[65]

of communication. At night enemy warships bombarded shore installations virtually at will.

On 23 August, a heavily guarded convoy of transports was sighted moving south of Rabaul. The Allied fleet took partial revenge for its earlier losses as carrier aircraft combined with land-based planes from Guadalcanal and the Southwest Pacific Area succeeded in inflicting damage that turned the enemy back. The Japanese, however, were able to land additional troops on Guadalcanal by means of the "Tokyo Express"-fast night runs by destroyers from the northern Solomons-and the Marines defending the airfield faced increasing pressure. The campaign became a race to see which side could build up the greater number of reinforcements and supplies, the outcome depending upon control of the sea and air.

Intelligence meanwhile indicated that the Japanese had discovered the Allied occupation of Milne Bay.34 General MacArthur anticipated that the enemy, incensed at having been forestalled, would soon attempt retaliatory measures. Preparing for such a move, he secretly dispatched the Australian 18th Brigade to reinforce the 7th Brigade which had been sent in July to garrison the airfield. In addition to these two brigades, the forces at Milne Bay included some 1300 United States combat and service troops.35 They were under the command of Maj. Gen. Cyril A. Clowes, who arrived on 13 August to take charge of the forces in that area. Air power consisted of two fighter squadrons and part of a Hudson bomber squadron based on the Milne airdrome.

The first indications of a Japanese attack became evident on 24 August when seven enemy barges were sighted moving down the Papuan coast midway between Buna and Milne Bay. An air raid on Milne Bay by about twelve Japanese fighters was carried out on the same day. On 25 August, the enemy barges were discovered beached off Cape Varietta on Goodenough Island. They were immediately strafed and destroyed by Allied planes.36

A more dangerous threat, however, appeared on the 25th in the form of an enemy convoy of nine vessels moving southward from the direction of Rabaul past the Trobriands and Normanby Island. Bad weather hampered efforts to bomb the convoy which subsequently succeeded in landing over 1,100 troops by power barge near Waga Waga and Wanadala. (Plate No. 19) Japanese warships moved into the bay under cover of darkness to shell Allied positions and then, covered by heavy mists, retreated to open waters by dawn. Enemy troops put ashore initially and later as reinforcements numbered slightly over 1,900 men.

The Japanese proceeded with the operations, unaware of the secret Allied reinforcement of their Milne Bay garrison. The first important clash of the opposing forces took place near KB Mission, a few miles west of Waga Waga. The enemy, bringing ashore light tanks in addition to mortars and 25-pounders pushed the

[66]

defenders back beyond the Mission to the west bank of the Gama River.

By dawn of the 27th, the fighting had moved still further back toward No. 3 Airstrip. Here the Allies had drawn up a strong defense line hidden in the wooded area on the edge of the strip. For three days, the enemy did his utmost to advance but was unable to pass the strip defenses. Finally, on 30 August, having been hastily reinforced on the previous night by the 3rd Kure Special Landing Party, the Japanese launched a determined attack in force.37 They came forward in repeated and furious charges backed by field pieces and heavy machine guns but a solid wall of Allied fire prevented a single Japanese from crossing the strip. The attack was repulsed and the enemy suffered heavily. That night marked the turning point of the battle.

With their tanks bogged in mud, their task force commander and most of their officers killed, their rations almost exhausted, and their equipment unsuited for the terrain and climate around Milne Bay, the Japanese began to crumble rapidly. The Allies, seizing the advantage, started their counterattack. Moving rapidly across No. 3 Airstrip, past the Gama River, they reoccupied KB Mission. In the early morning of 2 September the advance was continued. On 5 September the enemy was driven from his position at Waga Waga, thus putting an end to organized resistance. Several pockets farther east were cleaned out by air strafing and artillery.

The Japanese managed to evacuate about 1300 of their troops on the evening of 5 September, abandoning the remainder to the jungle. Some of these hapless troops tried to make their way over the Stirling Range and along the coast to rejoin their forces at Buna. Some were caught in the lower foothills and in the native villages near Ahioma, at the eastern end of the Bay. Others who had succeeded in crossing the range were found and killed near Taupota on the north shore. The rest died of starvation and disease along the coast. Despite their incompetent leadership, the Japanese troops at Milne Bay fought bravely and tenaciously to the bitter end. A grim foretaste of the future was to be found in the fact that at one phase of the operations, nearly 700 Japanese were killed and only three, (two of whom later died) were taken prisoner. Wounded Japanese who could not be evacuated were shot by their own men.

General MacArthur analyzed the signifi-

[67]

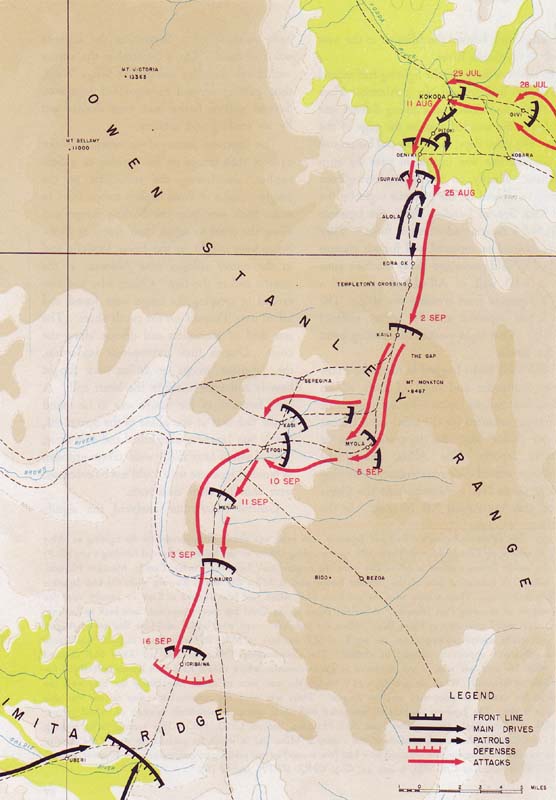

PLATE NO. 20

Action from Oivi to Imita Ridge, July-September 1942

[68]

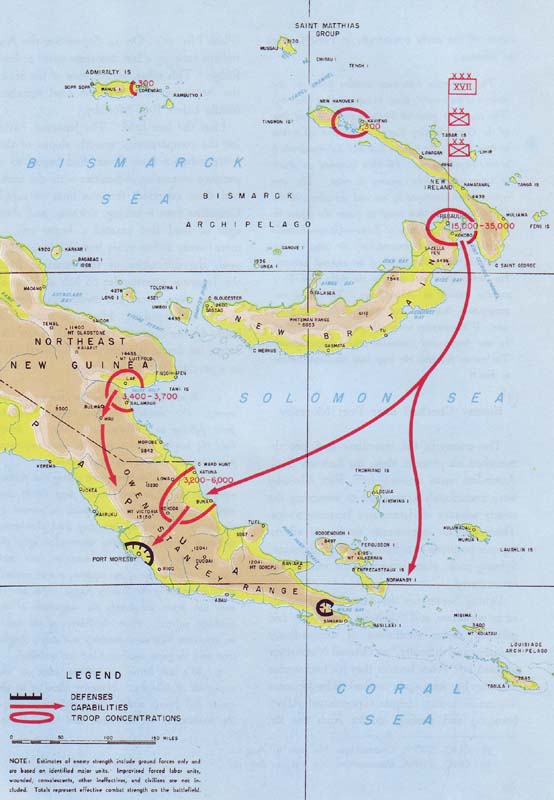

PLATE NO. 21

Japanese Dispositions and Capabilities, September 1942

[69]

cance of the early operations in New Guinea as follows:

This operation represents another phase in the pattern of the enemy's plans to capture Port Moresby. This citadel is guarded by the natural defense line of the Owen Stanley Range. The first effort was to turn its left flank from Lae and Salamaua which proved impracticable. He then launched an attack in large convoy force against its rear. This was repulsed and dissipated by air and sea action in the Coral Sea. He then tried to pierce the center in a weak attempt by way of Buna-Gona-Kokoda subjecting himself to extraordinary air losses because of the extreme vulnerability of his exposed position. His latest effort was to turn the right flank by a surprise attack at Milne Bay. The move was anticipated, however, and prepared for with great care. With complete secrecy the position was occupied by our forces and converted into a strong point. The enemy fell into the trap with disastrous results to him.38

Enemy Checked near Port Moresby

The enemy in the meantime had not diminished his pressure along the Kokoda Trail. Australian units arriving from Port Moresby were immediately committed to stemming the steady advance of determined Japanese troops. There was no opportunity to choose advantageous positions or to build elaborate defenses; fighting took place wherever the enemy was encountered.

During September the Australians continued to withdraw, still "fighting tenaciously and gallantly under conditions of extraordinary hardship and difficulty," as General MacArthur phrased it.39 From Isurava they fell back across The Gap but were again outflanked by Japanese infiltration tactics, despite concentrated Allied bombing and strafing attacks from the air. (Plate No. 20) On 14 September the Australians took up a last desperate stand at Imita Ridge. This ridge, within view of the sea on the Australian side, was the final remaining hurdle before Port Moresby.

Here the line held. The Japanese, having left the comparatively smooth slopes of their initial advance from Buna, had begun to experience increasing difficulties with the terrain and their extended, tenuous lines of supply. Casualties from bombing, sickness, and shortages of food had exacted a heavy toll. A mere twenty airline miles from his long-sought goal, the difficulties of the situation forced the Japanese commander to halt and consolidate his worn forces and await reinforcements of men and supplies. His grim story of the battle for the Kokoda Trail, told a short time before his death, is revealed by General Horii in a proclamation to his troops:

1. Repeatedly we were in hot pursuit of the enemy. We smashed his final resistance in the fierce fighting at Ioribaiwa, and today we firmly hold the heights of that area, the most important point for the advance on Port Moresby.

2. For more than three weeks during that period, every unit forced its way through deep forests and ravines, and climbed scores of peaks in pursuit of the enemy. Traversing knee deep mud, clambering up steep precipices, bearing uncomplainingly the heavy weight of artillery ammunition, our men overcame the shortage of our supplies, and we succeeded in surmounting the Stanley Range. No pen or word can depict adequately the magnitude of the hardships suffered. From the bottom of our hearts we appreciate these many hardships and deeply sympathize with the great numbers killed and wounded....

3. We will strike a hammer blow at the stronghold of Moresby. However, ahead of us the enemy still crawls about. It is difficult to judge the direction of his movement, and many of you

[70]

have not yet fully recovered your strength. I feel keenly that it is increasingly important during the present period while we are waiting for an opportunity to strike, to strengthen our positions, reorganize our forces, replenish our stores, and recover our physical fitness....

4. When next we go into action, this unit will throw in its fighting power unreservedly.40

In spite of the victory at Milne Bay and the checking of the enemy on the Kokoda Trail, General MacArthur felt that the overall situation was becoming increasingly precarious. During July and August the Japanese had been steadily pouring planes and ships into the Truk-Rabaul region and after their defeat at Midway the main battleground was now definitely in the South and Southwest Pacific Areas. Estimates on Japanese dispositions and capabilities indicated that they would soon be in a position to renew their drive for control of New Guinea. (Plate No. 21) General MacArthur reported to Washington that, unless steps were taken to match the heavy ground, air, and naval forces which the Japanese were assembling, a situation might develop similar to that which had successively overwhelmed Malaya, the Netherlands East Indies, and the Philippines early in the war.41

[71]

Go to: |

|

|

Last updated 20 June 2006

|