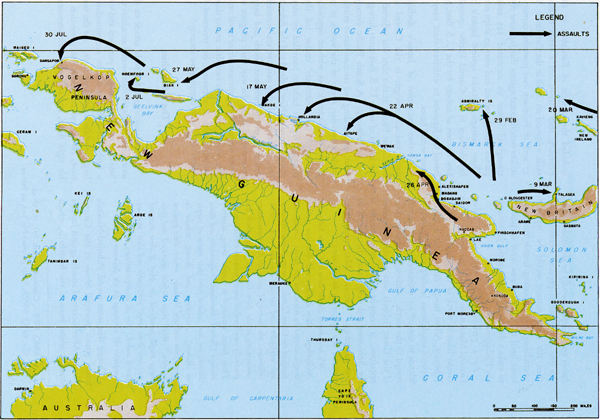

CHAPTER VI The route of General MacArthur's return to the Philippines lay straight before him-westward along the coast of New Guinea to the Vogelkop Peninsula and the Moluccas. (Plate No. 39) The successive Allied blows in New Guinea, New Britain, and the Solomons had seriously breached the Japanese outer wall of island defenses. General MacArthur was still about 1,600 miles from the Philippines and 2,100 miles from Manila, but he was now in a position to carry out with increasing speed the massive strokes against the enemy which he had envisioned since the beginning of his campaigns in the Southwest Pacific Area. With the Japanese confused and thrown off balance by the recent series of Allied successes, General MacArthur urged that the situation be exploited immediately :

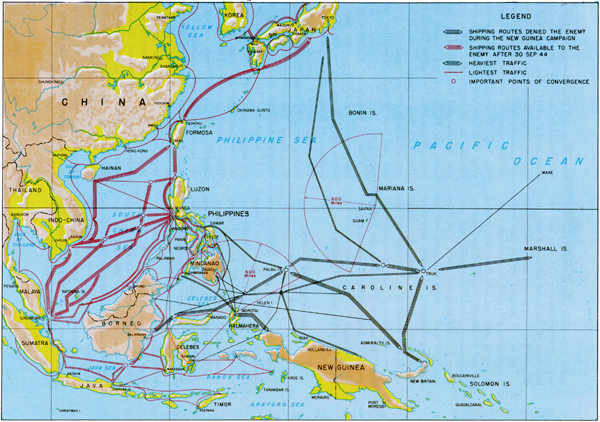

General MacArthur planned to advance through western New Guinea because that route would provide the best opportunity for the complete utilization of the Allied ground-air-navy team. Such a drive, penetrating Japan's defense perimeter along the New Guinea line, would permit the by-passing of heavily defended areas and, at the same time, follow his tried and proved pattern of operations.2 The land-based bomber line would again be moved westward by the successive occupation of new air sites; ground forces would be rapidly deployed forward by air transport and amphibious movements; additional plane and ship bases would be established as each objective was taken. Enemy naval [134] PLATE NO. 39 [135] forces and shipping would be eliminated along the line of advance to prevent reinforcement; then the same pattern would be repeated, neutralizing and pocketing hostile concentrations until the Allied forces were in position to make a direct attack against the Japanese in the Philippines. As a preliminary to the coming drive, General MacArthur directed the seizure of the Green Islands, north of Bougainville. On 15 February, Allied troops carried out a weakly opposed amphibious landing and captured the islands to cut off an estimated 22,000 enemy troops to the south. Although the occupation of the Green Islands was a relatively minor operation, it completed the envelopment of the Solomons and rung down the curtain on that campaign. General MacArthur summarized the operation as follows:

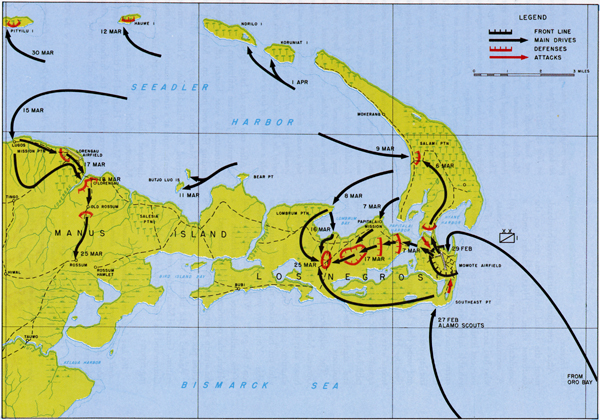

During this same period, Admiral Nimitz's forces struck powerful blows in the Central Pacific. After successful attacks against Japan's strategic island bases in the Marshalls, which included the capture of Kwajalein in early February, they carried out a series of heavy raids westward on Truk in the Carolines. On 17 and 18 February two powerful carrier air strikes were directed against this Japanese naval stronghold where an estimated 325 enemy planes were destroyed and over 30 ships sunk. These damaging attacks against Japan's two key defenses in the Central Pacific opened a new horizon of activity for the U. S. fleet, and forced the Japanese to withdraw their navy to more secure bases. Another indication of Japan's declining naval and air strength in the Central and Southwest Pacific at this time was reflected in the moves of other U.S. fleet units during 22 and 23 February. A South Pacific destroyer team, on a raiding and reconnaissance mission, made a two-day sweep of the waters in and around the Bismarck Sea without opposition. Although the destroyers' course led them through regions hitherto patrolled by enemy planes based in New Ireland and the Admiralties, and although they made several successful strikes on enemy merchant vessels and barges encountered along the way, their progress was never contested by Japanese air or naval units. The waters, once under complete enemy domination, could, it appeared, be traversed by Allied craft with comparative security.4 Before launching a full-scale attack to the west, MacArthur needed an additional base near enough for staging purposes and with a harbor of sufficient size to accommodate a large amphibious striking force. At the same time, he wished to insure the protection of his right flank, and to prevent reinforcements [136] from reaching enemy troops bottled up in the Bismarcks-Solomons area. The Admiralty Islands in the Bismarck Archipelago filled these requirements. They possessed ideal natural harbors and airfield sites which could support subsequent operations along the New Guinea coast and against the Carolines and Marianas to the north. In addition, their strategic location would provide another base from which to complete the encirclement of the Japanese cut off on New Britain and in the Solomons. Occupation of the Admiralties by the Allies would put the final seal on the isolation of Rabaul. The original plan called for an amphibious operation on 1 April against the Admiralty Islands by Southwest Pacific Forces in conjunction with an attack on Kavieng by Admiral Nimitz's fleet units. In February, however, General MacArthur saw reflected in the lack of opposition to Allied air and naval craft in the Bismarck area, a temporary confusion and weakness of the enemy which he decided to capitalize upon without delay. He felt that the situation presented an ideal opportunity for a coup de main which, if successful, could advance the Allied timetable in the Pacific by several months and deal another powerful blow to Japan's crumbling defense structure in the New Guinea area. The principal enemy positions in the Admiralties were on Los Negros and Manus Islands, both of which were in a precarious position at this time. Allied air power blocked the shipment of sufficient supplies to maintain a strong defense and seriously reduced the possibility of bringing in reinforcements in time to withstand an Allied attack. The feeble reaction to Allied raids offered by Japanese naval and air units demonstrated that their resistance would probably be minor and easily overcome. The question of enemy ground dispositions in the Admiralties, however, posed a different problem. Opinions differed sharply on the number of Japanese troops in the islands. Repeated air observation flights over Manus and Los Negros at the end of February reported a total lack of enemy activity. Momote airfield was observed to be entirely unused; even the bomb-craters in the runway had been left unfilled and grass was growing along the air strip. Surrounding buildings and installations were seemingly unattended and in a bad state of disrepair. The continued lack of antiaircraft fire and apparent desertion of the air strips reported by air reconnaissance supported the inference that the Japanese had left the islands altogether.5 General MacArthur's G-2, however, held firmly to a different opinion. On the basis of intercepted information and ground reports over a long period of time, the conclusion reached was that " cumulative intelligence does not support air observer reports that the islands have been evacuated."6 On 15 February, [137] the probable enemy units still on the islands were listed and their total strength was estimated to be approximately 3,250 men.7 On 24 February, these figures were revised and the estimate of Japanese troops in the Admiralties sector was raised to 4,000.8 G-2 analysis discounted the significance of the lack of antiaircraft oppositions pointing out that " prior to the Allied landing at Cape Gloucester a similar situation was reported but resistance was encountered to the landing and to the subsequent offensive moves." It attributed the lack of antiaircraft fire to the deteriorated state of the enemy's logistical situation and predicted that "the enemy will hold his fire until the final defense of the Admiralties is imminent."9 On 24 February General MacArthur directed that an immediate reconnaissance in force be made to probe the island defenses by landing at Hyane Harbor on eastern Los Negros, where enemy positions apparently were weakly held. His aim essentially was to strike swiftly, achieve surprise, and thus avoid bitter fighting and heavy casualties at the beachhead. If an initial foothold could be established without undue losses, the reconnaissance force would then advance and seize Momote airstrip near the harbor entrance; if unforeseen enemy strength should be encountered at the beaches, however, and an unfavorable situation should develop, a speedy withdrawal would be carried out. In cognizance of his G-2 estimates of enemy strength in the Admiralties, General MacArthur also took precautions against the eventuality of a delayed counterattack in strength. A strong auxiliary force was readied at Finschhafen which would be sent two days later as reinforcements to enlarge the perimeter, if established, and to guard against any powerful Japanese reaction that might develop after the Allied landing was secured. On the morning of 29 February, the daring strike was launched. The reconnaissance force was light, consisting of approximately 1,000 troops of the 1st Cavalry Division supported by two cruisers, a dozen destroyers, and the necessary air cover. The troop units were made up mainly of a reinforced squadron of the 5th Cavalry under Brig. Gen. William C. Chase; the naval forces were under the command of Admiral Kinkaid. General MacArthur was relying almost entirely upon surprise for success and, because of the delicate nature of the operation and the immediate overall decision required, he accompanied the force in person aboard Admiral Kinkaid's flagship, [138] PLATE NO. 40 [139] the Phoenix. After a preliminary air and naval bombardment, the initial landing was made on the southwest shore of Hyane Harbor under a completely overcast sky. (Plate No. 40) A reconnaissance group of Alamo Scouts, who had secretly explored the vicinity of the intended landing two days previously, provided valuable information on the dispositions of enemy concentrations near the harbor.10 The first assault waves met little opposition. Before the Japanese could recover from their surprise and swing their heavy guns, which were facing Seeadler Harbor, into position, most of the troops were ashore. Working in a heavy rain against sporadic and weak enemy fire they established a wide perimeter along the airstrip and started the preparation of defensive positions. The calculated risk had been justified. General MacArthur, coming ashore just six hours after the first assault wave to survey the situation, said to General Chase: "Hold what you have taken, no matter against what odds. You have your teeth in him now-don't let go."11 With the scheduled arrival of the auxiliary force from Finschhafen on 2 March, the perimeter could be enlarged and the airstrip secured and prepared for incoming Allied planes. Assured of the ultimate success of the operation, General MacArthur returned to New Guinea and his Headquarters issued the following report :

After two days of hard fighting in which determined Japanese infiltration attempts and counterattacks were beaten off, the original landing force was joined on 2 March by General MacArthur's auxiliary forces which had arrived from Finschhafen. These reinforcements came at a timely moment. An enemy document captured early the next morning disclosed that a Japanese effort to regain Momote airfield would be made on the night of 3 March. Hurried but thorough preparations were made for the forthcoming attack, which was expected to include most of the [140] Japanese remaining on western Los Negros and whatever troops could be brought from nearby Manus Island. The scheduled attack came as promised. Wave after wave of tough Japanese infantry came pouring through the darkness against the Allied defenses.13 In fierce but foolhardy charges, they sought to overwhelm each Allied position by sheer weight of numbers. When those in front were mowed down by mines and machine gun fire, the others rushed on undaunted over the bodies of their comrades only tb be cut down in turn. During the course of these suicidal " banzai " charges, the enemy resorted to wily and fanciful tactics. Japanese, who had somehow managed to learn the names of Allied platoon leaders, tried to trick them into misdirecting or ceasing their fire by interpolating false orders in perfect English into tapped telephone wires. One column of enemy troops came marching forward singing, for no apparent reason, "Deep in the Heart of Texas." Bayonets were affixed to five-foot poles and used as spears by the Japanese when their ammunition gave out. Bandages were discovered tied around their arms at pressure points, presumably to provide a ready tourniquet which would permit them to continue fighting should they lose the use of either hand.14 It was a bizarre and bloody night but the efforts of the Japanese, however brave, were erratic and unco-ordinated. Their attacks tapered off as their dead began to litter the field of battle and by morning the main enemy counterdrive had been decisively crushed. The cavalry forces awaited the arrival of more troops before clearing the rest of the islands. Further reinforcement echelons arrived on the 4th, 6th and 9th of March. The Allies struck out from the Momote perimeter westward to take Papitalai and northward to occupy Salami Plantation. From the latter point they moved on across Seeadler Harbor to seize Papitalai Mission and Lombrum Plantation. By 30 March all organized enemy resistance on Los Negros had been overcome. Meanwhile operations against the larger island of Manus had begun. On 9 March, the 2nd Brigade Combat Team of the 1st Cavalry Division, under Brig. Gen. Verne D. Mudge, disembarked at Salami Plantation. On 15 March, after units of the 7th Cavalry had secured the two small islands of Hauwei and Butjo Luo off the north coast of Manus, assault troops of the 2nd Brigade landed at Lugos Mission, two miles west of Lorengau. The Japanese forces, depleted by the Los Negros counterattacks, put up a stubborn but useless struggle. Lorengau airfield was captured on the 17th and the Allied units moved to take Rossum on the 25th. This brought to an end the campaign for the Admiralties. The success of the operation was complete. The Japanese had been powerless to present any naval opposition to the Allied landings and their efforts in the air were sporadic and easily overcome. On the ground, G-2 estimates had been remarkably accurate. It was calculated, after a count of enemy killed and captured, that the Japanese had used approximately 4,300 troops to defend the islands-substantially the force predicted in G-2 estimates of enemy strength.15 The occupation of the Admiralties had tied the last knot in the noose around Rabaul. More than 100,000 Japanese were now choked off in the Bismarcks-New Britain-Solomons [141] area. Henceforth the enemy was compelled to rely almost exclusively on risky submarine and destroyer runs for carrying in bare essentials. In addition the supply route to his outer defenses was pushed farther west and the whole sea region between Truk and New Guinea was placed within Allied air range. With the threat to his right flank removed, General MacArthur could now concentrate his entire attention on the task of moving westward along the coast of New Guinea. Concurrently with the landings in the Admiralties, several lesser operations were undertaken to supplement the main Allied drives in the Bismarck and Solomon Seas areas. On 6 March, the 1st Marine Division on New Britain pushed on to take Talasea on the Willaumez Peninsula and then occupied the Cape Hoskins area. Most of the Japanese south of Rabaul had by this time retreated northeastward into the Gazelle Peninsula. On 20 March, Admiral Halsey's forces captured Emirau Island in the St. Matthias group. The enemy troops had been withdrawn before the landing and the objective was gained without cost. This operation further strengthened the Allied grip on the Bismarck Archipelago and, in addition, provided an excellent air base within short range of Kavieng and Rabaul. Meanwhile, the Australians, who had been fighting vigorously on the Huon Peninsula and in the Ramu Valley, pressed westward along the New Guinea coast. Progress had been held up considerably by the steep ranges of the Finisterre Mountains but, working steadily across this natural barrier, New Guinea Force moved into Bogadjim on Astrolabe Bay on 13 April. Madang was captured eleven days later, and on 26 April the Australians occupied Alexishafen as the Japanese carried out a mass retreat to the west toward Wewak and Aitape. The sudden seizure of the Admiralties put the Allied timetable well ahead of schedule. According to the original plan Hansa Bay was the next objective on the New Guinea coast but in view of the spectacular success of the Admiralties landing, General MacArthur was anxious to take a longer step forward. The proposed capture of Hansa Bay would mean an advance of only 120 miles from the Allied position at Saidor, and, even if the Allies occupied that base they would still have to face the large Japanese concentrations around Wewak and Aitape. With the outcome of his operations into the Admiralties assured, General MacArthur planned a bold maneuver which, at one stroke, would move his forces almost 500 miles forward and at the same time squeeze some 40,000 Japanese troops between the jaws of a strong Allied vise. He would by-pass Hansa Bay, by-pass the enemy stronghold at Wewak, and strike well to the rear at Aitape and Hollandia. On 5 March, just four days after his return from Los Negros, General MacArthur submitted his daring plan to the Joint Chiefs of Staff in Washington:

[142]

It was later decided that the rapid development of the Admiralties' extensive harbor and airfield facilities, coupled with the occupation of Emirau Island, made the capture of Kavieng unnecessary. The plan to invade New Ireland was consequently cancelled.17 The naval forces originally allocated for the Kavieng operation could now be shifted to the New Guinea theater to be employed against Hollandia. Admiral Nimitz agreed to support fully the proposed assault on Hollandia. The Pacific Fleet would lend all possible assistance by furnishing the large naval forces required for such an ambitious undertaking. Carrier planes would provide close cover for the initial assaults of the landing parties since the projected point of attack was too distant from the forward bases held at the time for adequate protection by land-based fighters. The navy would also carry and protect the tremendous stores of supplies, munitions, and special equipment which were needed to maintain a major invasion operation. In addition, carrier task groups would begin the immediate neutralization of enemy positions in the western Carolines from which possible interference to the Allied operation might be forthcoming. General MacArthur's plan called for landings on both sides of Hollandia, at Humboldt and Tanahmerah Bays, with a simultaneous landing by a smaller force at Aitape, midway between Hollandia and Wewak. The Hollandia forces would converge on the flanks of the three airstrips inland while the forces to the east would seize the fighter field at Aitape and prevent any junction of the enemy's Wewak and Hollandia troops. The target date was set for 22 April.18 During March and the first part of April, intensive air raids were launched by the Fifth Air Force against the intervening Japanese airfields on New Guinea. Strong formations of B-25's with fighter escort blasted continuously at Hansa Bay, Wewak, and Hollandia. General MacArthur described the punishing raid of 3 April against Hollandia as follows:

[143]

During the same period navy carrier planes struck in force at the Palau Islands and at Yap, Ulithi, and Woleai to interdict any reinforcement efforts by the enemy from the western Carolines. Large numbers of Japanese planes were destroyed on the ground and in the air, and shipping concentrations were heavily hit. Any threat of opposition from the northwest was virtually removed. The Thirteenth Air Force also sortied from the Admiralties to continue pounding Rabaul and Kavieng, and the Royal Australian Air Force, operating from northwestern Australia, attacked enemy airdromes in the regions of Arafura Sea, Geelvink Bay, and the Netherlands East Indies. Intelligence reports during March indicated that the Japanese were hurriedly strengthening their bases at Hansa Bay and Wewak.20 Information on their defense dispositions indicated that an Allied attack was expected at either or both of these places. General MacArthur's G-2 thought that the opportunity to encourage this belief was too attractive to be overlooked, and on 7 March submitted a comprehensive deception plan to strengthen the enemy's conviction and at the same time lure him into diverting his forces from the Hollandia-Aitape area. General MacArthur was in accord with this suggestion, and ordered his forces to carry out definite deceptive measures along the New Guinea coast.21 The air force was directed to [144] continue the air attacks on Madang and Wewak and to drop dummy parachutes in the Hansa Bay area. Frequent reconnaissance flights were sent on ostensible mapping and photographic missions. The navy was directed to make suitable demonstrations along the same lines. PT boats were ordered to conduct operations against certain points along the coast in the Hansa Bay region, and empty rubber landing boats, indicative of disembarked scouting parties, were to be left at various spots along the shores east of Wewak. Hollandia was the principal Japanese rear supply base in New Guinea. A sheltered but undeveloped harbor located on Humboldt Bay, it provided the only protected anchorage of any size between Wewak and Geelvink Bay. The airfield area, shielded from the sea by the high Cyclops mountain range, was near Lake Sentani, about twelve miles from Humboldt Bay and midway to Tanahmerah Bay to the west. The bulk of the enemy's remaining New Guinea air strength was based on three large airdromes in this area. Hollandia also served the Japanese as a important trans-shipment point for the unloading and transfer of personnel and cargo from large transports to smaller coastal vessels. A considerable backlog of supplies was observed on the beaches and in the vicinity of the airfields. Intelligence estimated the number of Japanese troops in the Hollandia-Aitape area at the end of March to be 15,000; at Wewak-Hansa Bay, 30,000; at Wakde-Sarmi, 5,500; and in the Manokwari-Geelvink Bay area, 11,000.22 A large Allied task force was gathered in expectation of a difficult campaign. The closest teamwork of all participating components would be required to accomplish the largest operation and the longest amphibious move yet attempted in the Southwest Pacific Area. The projected operation involved a distance of 985 miles from Goodenough Island, the principal staging area, and over 480 miles from Cape Cretin, south of Finschhafen, the advance staging point. General Krueger, Commanding General of Alamo Force, was made responsible for the co-ordination and planning of the ground, air, and naval forces. General Eichelberger, commanded the main landing group comprising the 24th and 41st Divisions, which was to seize the Hollandia airdromes by invasions at Humboldt Bay and Tanahmerah Bay. Brig. Gen. Jens Doe, commanded the 163rd Regimental Combat Team which was to land in the Aitape-Tadji area and capture the Tadji airfield. Another combat team would be kept in reserve. The naval forces were to provide air cover and escort protection. Admiral Barbey was in charge of the naval amphibious forces while the carrier forces of the Fifth Fleet were under Rear Adm. Marc A. Mitscher. The entire task force for the invasion rendezvoused north of the Admiralties and then proceeded in a northwesterly direction toward Palau. Although this course was 200 miles longer than the direct route, it was intended to mislead the Japanese and prevent them from determining the exact objective in case of discovery by aerial reconnaissance. Swinging suddenly southward the huge convoy approached the New Guinea coast. On 21 April, fast carrier planes struck the Wakde-Sarmi, and Hollandia airfields while the Fifth and Thirteenth Air Forces concentrated on Wewak and Hansa Bay. On 22 April, after heavy preliminary naval and air bombardment, the invasion troops went ashore according to plan. Complete tactical and strategic surprise was achieved. The con- [145] voys had sailed within striking distance of their objectives apparently without detection. The ease of the landings exceeded even the most sanguine hopes. No more than token resistance was met at any point and there was no interference from the enemy's air or naval forces. The painstaking deception measures had been remarkably effective. In the Hollandia area, United States troops made a virtually unopposed advance. At both Humboldt Bay and Tanahmerah Bay opposition to the landings was ineffective and the two jaws of the giant invasion pincers clamped down rapidly on both sides of Mt. Cyclops. (Plate No. 41) So stunned was the enemy by the unexpected landings, that in the beach area complete radar sets and other valuable equipment, still uncrated, were left behind to be captured.23 Progress was limited only by the problems of supply and the difficult terrain since the Japanese had failed to exploit the natural defensive positions offered by the narrow mountain defiles. On 26 April the Sentani, Cyclops and Hollandia airdromes were captured. In the meantime the Tami airstrip, lying on the coastal flat east of Humboldt Bay, was secured. With all objectives achieved, only mopping up operations and consolidation remained for the combat troops. On 6 June the Hollandia phase of the operation was officially closed.24 At Aitape the story was much the same. On D-Day, the Tadji airfield was seized and a perimeter defense was consolidated. Although there were many contacts with scattered Japanese groups, resistance on the whole was light. General MacArthur emphasized the strategic importance of the Hollandia-Aitape operation in his official communique:

[146] PLATE NO. 41 [147]

Later evidence revealed that the garrison strength in the Hollandia area closely paralleled the G-2 estimate of 15,000 troops. This garrison, however, was comprised of a heterogeneous mixture of lightly armed and ill-trained service units and failed to respond with the last-ditch type of resistance heretofore so characteristic of the Japanese.26 The enemy had intended to build Hollandia into a well defended strongpoint. The service units were forerunners of the heavy fortifications and combat troops that were slated to meet an anticipated Allied drive from Hansa and Wewak. If the Allied attack had not come as soon as it did the results might well have been different. One of the most urgent tasks after the initial assault waves were ashore was the building of dispersal and storage areas and the forcing of exits from the congested beaches. Engineer units worked rapidly and efficiently to complete high priority construction projects. The supply track from Depapre on Tanahmerah Bay to the airdromes was improved to permit jeep traffic, and a road from Pim on Humboldt Bay was open for traffic as far as the Cyclops strip by the time it was captured. For major construction, the entire Hollandia area was divided into the Hollandia, Sentani, Tanahmerah, Tami, and Dock sectors. Permanent facilities included docks, a 900-foot channel through a coral reef at Depapre, the completion and improvement of the road net, the rapid repair and improvement of captured airdromes, water supply facilities, and fuel pipe lines. As roads improved and building materials became available, emphasis shifted to the construction of hospitals, camps, headquarters areas, and warehouses. All this was necessary to make Hollandia a supply base and staging area for future operations, and to establish it as the operating headquarters of the Southwest Pacific Area. The Hollandia-Aitape operation had neutralized enemy forces to the east, increased the range and effectiveness of the Army Air Forces, and gained major harbor facilities. The initial success made possible the advancement of the schedule for subsequent operations to the west by releasing troops, ships, and planes for attacks from the newly developed air and naval facilities in the Hollandia-Aitape area. The [148] seizure of Hollandia forced the Japanese to withdraw their line of defense westward to Sarmi and Biak and reduced their communications in the New Guinea area practically to zero.27 Regrouping of Command Functions The expanding nature of the tasks ahead, involving a substantial increase in the United States forces allocated to the Southwest Pacific Theater, caused General MacArthur to reorganize his command. He recommended that, excepting the units required for garrison operations, the forces of the South Pacific Command be regrouped and apportioned to the areas in forward contact with the enemy. Accordingly, on 15 June, the Thirteenth Air Force, the XIV Corps, the 25th, 37th, 40th, 43rd, 93rd, and the American Divisions in addition to the 1st and 2nd Philippine Regiments, were assigned to the Southwest Pacific Area. On the same day, the Far Eastern Air Force, under General Kenney, was established to direct the operations of the Fifth and Thirteenth Air Forces. The XIV Corps, under Maj. Gen. Oscar W. Griswold, was given the responsibility of defending air and naval installations along the Solomons-New Britain-Emirau axis. New Guinea Force was given the same mission for all of New Guinea east of the Ramu River. The advance echelon of a new Eighth Army Headquarters was brought in to take over part of the administration and tactical duties of the Sixth Army; General Eichelberger assumed command on 7 September when the Eighth Army was formally established.28 The Seventh Fleet, after 5 May, comprised 3 light cruisers, 27 destroyers, 30 submarines, and supporting vessels. The deficiencies were filled by Admiral Nimitz from the Third Fleet which was transferred to the Central Pacific along with the 15th Marine Amphibious Corps and most of the naval air forces of the South Pacific Area. Since Admiral Halsey remained with the Third Fleet, he relinquished his command of the South Pacific Force on 14 June.29 As the Allied advance speared westward into Dutch territory, General MacArthur directed that civil affairs in that region be administered by Netherlands East Indies officials accompanying the troops. This policy of immediate transfer of civil control without a preliminary military government was instituted by General MacArthur at the start of the war. Rather [149] than establish a military governor, he retained and supported the constitutional authority of the existing government. This policy was continued during the occupation of the islands north of Australia, when Australian civil officials assumed authority promptly in the wake of the operations. The success of this method was reflected in the complete lack of friction between the various governments concerned. The Hollandia invasion initiated a marked change in the tempo of the Allied advance westward. Subsequent assaults against Wakde, Biak, Noemfoor, and Sansapor were mounted in quick succession and, in contrast to previous campaigns, no attempt was made to complete all phases of one operation before moving on to the next objective. General MacArthur was determined to reach the Philippines before December and consequently concentrated on the immediate utilization of each seized position to spark the succeeding advance. Even while the first waves of troops were pouring on to the Hollandia beaches, he radioed his Chief of Staff to complete preparations for the Wakde Islands operation with the least possible delay.30 On 29 April, he informed the War Department that he would attack positions in the Wakde region about I 5 May with the primary objective of obtaining " more airdrome space for displacement of the air forces forward." He also wished to secure light naval bases to prevent hostile interference with the development of the Hollandia area and to support subsequent assaults upon the Vogelkop Peninsula.31 The Wakde-Sarmi region, beginning approximately 140 miles west of Hollandia, had been developed by the Japanese into a ground and air position of considerable strategic importance. There were good airfields at Mafin and Sawar on the mainland and on Wakde Island itself just off the New Guinea shore opposite Toem. The Japanese had established numerous bivouac and storage areas along the entire coastal road from Maffin Bay to Sarmi. Intelligence sources indicated that the enemy was concentrated in strength in the Wakde-Sarmi region.32 It was therefore decided to employ a division less one regimental combat team at Sarmi and use the regimental team for the seizure of Wakde Island.33 Accordingly, the 163rd Regimental Combat Team of the 41st Division was directed to secure a beachhead in the Toem-Arara area, occupy Wakde Island, and protect the development of the required base construction. Wakde was too small an island to permit the direct landing of all required combat and service troops without serious congestion. Since Toem was in close range of any enemy coastal guns possibly on Wakde, it was planned to land first at Arara and from there maneuver into position for the Wakde invasion. On 17 May, after a heavy air and naval bombardment, the 163rd Regimental Combat Team landed at Arara and established a beachhead flanked on the west by the Tor River and on the east by the Tementoe River. (Plate No. 42) At the same time a reinforced company landed without opposition on tiny Insoemanai Island, south of Wakde, to lend mortar and machine gun support. The following day, the task force went into Wakde in a shore-to-shore [150] PLATE NO. 42 [151] movement from the Toem area. Stubborn resistance from a strongly entrenched enemy was encountered but by 20 May all opposition had been overcome and the airdrome cleared for use. On 19 May, supplementary landings were made on Liki and Niroemoar Islands to the west where radar installations were rapidly established. Two days later, the drive toward Sarmi was initiated at Toem by a landing of the 158th Regimental Combat Team. This force crossed the Tor River and, augmented by later reinforcements during June, moved forward to Maffin airfield against strong opposition.34 The capture of Wakde Islands provided General MacArthur with a new advance base within easy fighter range of his forward objectives, deepening his penetration of Japan's perimeter defenses. All remaining enemy airdromes and harbors in New Guinea were now subject to Allied medium bomber raids. The enemy's rear areas, already dislocated and disrupted by the seizure of Hollandia, were thrown into further confusion as the Allied air, naval, and ground forces continued to pound the pocketed Japanese in northern New Guinea. Biak Island lay next in the line of General MacArthur's sweeping advance. This island, 200 miles west of Wakde, possessed one of the two remaining major groups of enemy airdromes between Hollandia and Halmahera and therefore constituted a valuable military asset to the Allied scheme of operations. On 27 May, just one week after the last enemy guns were silenced on Wakde, the 4rst Division, less the 163rd Regimental Combat Team, made the first assault at Bosnek, on southern Biak. Its immediate objectives were the three airdromes at Mokmer, Borokoe, and Sorido near the southwest coast. (Plate No. 43) Initial opposition was relatively light and the landing force began an advance inland toward the airfields. General MacArthur described the landing operation and its strategic value as follows:

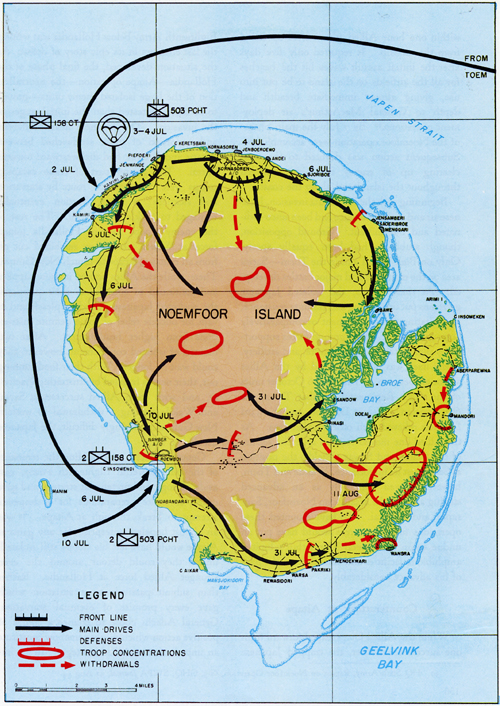

The slight opposition to the beach landings, however, was little indication of the bitter struggle to follow, for "the Japanese defense of Biak," as General Eichelberger's report described it, "was based on brilliant appreciation and use of the terrain."36 In this instance, the enemy had purposely withheld his main forces until the United States troops had advanced to the rugged terrain beyond the beaches. Then, from the dominating cliffs and caves overlooking the moving Allied columns, the Japanese [152] launched a savage counterattack and, aided by 5-ton tanks, succeeded in driving a block between the beachhead and invading forces. Enemy frontal pressure increased considerably and a temporary retirement and regrouping was necessary. The situation remained critical until the remainder of the 41st Division could be brought in from Wakde to bolster the United States positions.37 Thus strengthened, the 41st Division renewed its drive toward Mokmer at dawn on 2 June and, after several days of severe and violent fighting, seized the important airdrome at Mokmer on 7 June. Even then, the struggle continued unabated as the Japanese poured a heavy fire into the newly established airfield positions. It was another week before the strip could be brought into use. Additional United States reinforcements were sent in and, despite the enemy's fierce and valiant attempts to hold the remaining airfields at Sorido and Borokoe, the two strips were finally wrested from the Japanese. Major fighting on Biak was over by 22 July, although the Japanese continued sporadic resistance throughout the rest of the year. Mopping-up operations continued with amphibious shore-to-shore landings in August at Korim Bay, Wardo, and Warsa Bay. Other landings on Soepiori Island in September brought the campaign to a close. The figure of over 7,200 enemy killed by 20 January 1945 indicates the tenacity with which the Japanese fought to keep Biak from falling to the Allies.38 With hardly a pause, General MacArthur's forces swept forward to invade nearby Noemfoor Island, west of Biak. Since strategic considerations dictated a landing on the northwest end of the island where the enemy was judged to be strongest, the preceding air and naval bombardment was more intense than usual. Prior to and during the entire operation, naval forces maintained patrols, preventing any reinforcement of the Japanese garrisons. The Fifth Air Force, now merged with the Thirteenth Air Force under the Far Eastern Air Force, was strong enough to send 150 bombers on a single mission. For three weeks, ending with a record assault the day prior to the landings, the air bases at Noemfoor and other fields nearby were continuously and heavily pounded. On 2 July, troops of the 158th Regimental Combat Team landed near Kamiri airdrome. (Plate No. 44) Wading ashore through the surf, the landing force moved swiftly to the east, northeast and southwest and formed a strong perimeter. By evening Kamiri airstrip was securely in Allied possession and on the next day paratroopers of the 503rd Parachute Infantry were flown in to help destroy enemy resistance and to capture the other airfields. Thus reinforced, the United States troops attacked to the northeast and seized Kornasoren airfield on 4 July. Two days later a shore-to-shore landing was made at Roemboi Bay to capture the airdrome at Namber and [153] PLATE NO. 43 [154] PLATE NO. 44 [155] within one hour Allied planes were operating from the airstrip. It required only five days after the initial assault waves hit the beaches for all the airfields on the island to be put into use, giving almost immediate breadth and depth to General MacArthur's air deployment operations.39 By 7 July the main phases of the Noemfoor operation were accomplished. Subsequent action was devoted to the final clearing up of enemy remnants scattered throughout the island and along the coast. Beginning with the Hollandia invasion, Japanese air and naval resistance had been unco-ordinated and intermittent. Ground opposition, though stubborn, had been equally spotty. Only on Biak Island and in the Toem-Sarmi area on the mainland had major battles developed. At these points, the isolated Japanese garrisons put up a strong and resolute resistance, necessitating the employment of comparatively large numbers of Allied ground forces supported by planes, tanks, naval gunfire, and artillery. Sarmi itself was never occupied by the Allies although between 17 May and 6 October units of the 158th Regimental Combat Team, the 6th Division, the 31st Division, and the 33rd Division relieved each other in that area. As the Allied line moved forward after the seizure of the Maffin and Sawar airfields, the position at Sarmi lost its importance. Wakde and Toem, however, served admirably as an advanced staging area for the assaults on Noemfoor, Sansapor, and Morotai. To have mounted these operations from rear areas would have put an undue strain on General MacArthur's limited amphibious facilities and slowed down the pace of his advance considerably. While the Allied forces leaped forward from one success to another, the trapped Japanese Eighteenth Army below Hollandia was writing the last chapters in its epic story of defeat. As the situation developed, the final phase of the Hollandia-Aitape operation-the neutralization of the large isolated enemy units-proved to be more contested than the initial stages of the invasion. The Japanese near Hollandia and a portion of those sandwiched between Aitape and Wewak had fled westward towards Sarmi. The greater part of these escaping troops were destroyed en route by starvation and sickness; a small fraction eventually managed to trickle into Sarmi. The rest of the enemy troops east of Hollandia joined forces at Wewak where they remained cut off from all routes of escape to Dutch New Guinea. There, while the Allies poured in more supplies and continued to consolidate their positions, the pocketed Japanese waited helplessly and in vain for outside relief or some definite instructions from higher headquarters. After two months of isolated confinement, however, they could wait no longer. With their food running out, their nerves frazzled by frustrating inactivity, and with fresh Allied successes at Sarmi and Wakde making a withdrawal to western New Guinea increasingly difficult, the Japanese decided to act. General Adachi, commanding the remnants of the once powerful Eighteenth Army, cast aside all logic and pretense at strategy and gave orders to make preparations for a desperate attempt to break through at Aitape. It was an almost hopeless enterprise, for any gains at Aitape would have left his troops still isolated, unless they could detour around the even stronger Allied force at Hollandia. Rather than submit passively to a situation which gave every promise of eventual starvation, General Adachi chose to chance a course of positive action which might somehow constitute an impediment to Allied strategy. In an im- [156] passioned address, he exhorted his troops virtually to destroy themselves in a blind mass attack:

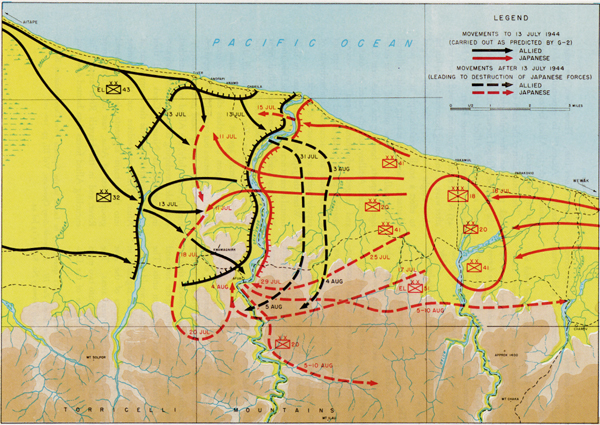

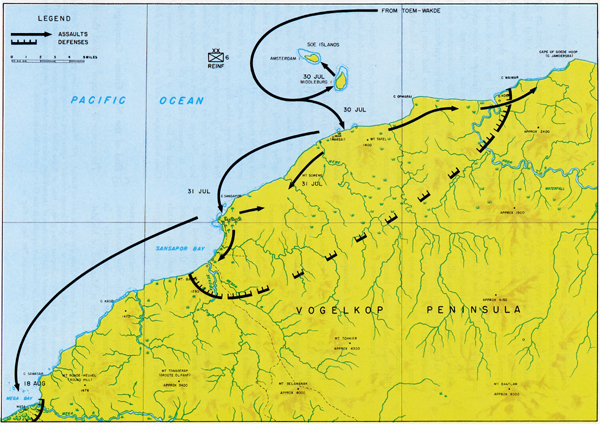

The preliminary movements leading to General Adachi's final attack against the Aitape positions were picked up by General MacArthur's G-2 Section. Cumulative intelligence from native sources, aerial reconnaissance, prisoner of war interrogations, intercepts, perusal of captured documents, and information from ground and PT boat patrols built up so unmistakable a picture of enemy intentions that Allied forces were able to take complete countermeasures well in advance of the actual attack. During the period 15 June to 3 July, special intelligence studies were made available to the staffs and the troops concerned, predicting 5-10 July as the date of attack and describing enemy dispositions, including the strength and identity of the forces involved.41 It was forecast that the Japanese contemplated employing the 20th and 41st Divisions assisted by garrison units. The probable plan of enemy formation would consist of two regiments abreast, a third regiment in the rear, and advance elements of the 41st Division available in the forward areas. The attack itself was to be divided into two main phases: Phase One, the seizure of the Driniumor River line; Phase Two, the general assault on Aitape.42 In expectation of the coming attack, the Allied forces at Aitape were heavily reinforced. The initial effort of the main enemy offensive took place soon after midnight on 11 July as the Japanese plunged forward in a mad suicidal rush against the Allied line south of the mouth of the Driniumor River. (Plate No. 45) Allied machine gunners mowed down wave after wave of oncoming Japanese troops, but by sheer weight of numbers, the enemy managed to effect a small breakthrough at the point of attack. Since the ensuing assaults followed substantially the course outlined in the intelligence reports, however, the Allies were fully prepared. Artillery, already placed in position and ranged beforehand, wiped out enemy assembly points while Allied planes kept up a continuous and accurate bombardment of supply points and routes of attack. When the Japanese were frustrated in their frontal attempt near the mouth of the Driniumor River, they tried to pierce the Allied right flank to the south through the foothills of the Torricelli Mountains. For over a month, they battered violently against the Allied lines in the Afua region in fruitless efforts to overrun the Aitape defenses but every drive was repulsed as the toll of enemy dead mounted sharply. Finally, on 31 July, the Allied forces launched a double enveloping counteroffensive, advancing eastward to Niumen Creek and then pivoting south to encircle the enemy's rear at Afua. This counterdrive cut the Japanese into three main segments, leaving scattered groups west of Afua, east of the Driniumor River, and in the Harech River area. The encircling Allied forces then hunted down and [157] PLATE NO. 45 [158] PLATE NO. 46 [159] destroyed the divided enemy units in detail, virtually annihilating the remainder of General Adachi's Eighteenth Army. By 10 August all effective resistance had ceased. The scattered remnants of an utterly defeated enemy force dispersed into the mountains to congregate at Wewak and But where they remained isolated and helpless until the close of the war. The reckless and abortive campaign had cost the Japanese heavily in killed and wounded. As General Adachi, himself, later gloomily acknowledged: " The story of the Eighteenth Army is tragic. We lost 10,000 killed when we decided to attack the Allies at Aitape."43 This final costly episode brought to an end the last Japanese hopes in New Guinea. Following the capture of Noemfoor Island, General MacArthur's next strike was directed at the Vogelkop Peninsula, the last enemy stronghold in the New Guinea area. Adhering again to the principle of avoiding massed enemy concentrations where feasible, his forces attacked the western end of the Peninsula, bypassing several thousand Japanese defending Manokwari. (Plate No. 46) On 30 July, a task force comprising elements of the 6th Division made simultaneous and unopposed landings near Cape Opmarai on the mainland, and on Middelburg and Amsterdam Islands to the northwest. Only a few enemy stragglers were encountered. The next day a shore-to shore landing from Cape Opmarai was carried out at Sansapor. As in other New Guinea areas, airdrome construction proceeded rapidly. In a short time airfields at Mar and on Middelburg Island and a float plane base at Amsterdam Island were fully operative. The operation to seize airfield sites on the Vogelkop Peninsula advanced Allied forces another 200 miles to the west. Groups of Japanese troops moving along the coast and inland were intercepted by units of the 6th Division in the Mar-Sansapor region and at Mega, twenty miles to the southwest. Only Sorong remained as the westernmost enemy base in the Vogelkop and its significance as a threat to Allied operations had been nullified by constant air assault. General MacArthur issued an official account of the Sansapor operation stating:

End of the New Guinea Campaign The capture of Sansapor marked the suc- [160] cessful termination of the long and hard-fought New Guinea Campaign. Control of the entire stretch of coastline from Milne Bay to the Vogelkop Peninsula was now firmly in Allied hands. In less than thirteen months, General MacArthur's forces, boring through layer after layer of Japan's outer defense perimeter, had moved 1,300 miles closer to the core of her island empire. The thousands of Japanese troops they had pocketed and cut off from outside aid had lost all ability to interfere seriously with Allied operational plans. When queried as to the immediate disposition of these isolated enemy segments, General MacArthur recommended that they be ignored until the main task was accomplished:

The Allies quickly developed their newly captured territory for immediate use. A major heavy bomber base was constructed on Biak, and fighters and medium bombers were stationed on Wakde, Noemfoor, and at Sansapor. From these bases the Far Eastern Air Force was to strike during the next few months at Japanese positions in Ceram, Celebes, Halmahera, Dutch Borneo, Java and the Palaus in preparation for the assault against the Philippines. In the meantime, the Royal Australian Air Force Command, was to interdict the Arafura, Banda and Ceram Seas and adjacent land areas thus protecting General MacArthur's southern flank. The New Guinea Campaign, waged through broiling sun and drenching rain amid tangled jungle and impassable mountain trails, had been a difficult and grueling struggle. In combating the extraordinary problems of climate and terrain, however, many valuable lessons were learned which were to prove of great benefit in pursuing the tasks ahead. This ability to cope with crises and profit from experience was a distinguishing characteristic of the Allied conduct of the war in the Southwest Pacific. One of the important victories won by General MacArthur's forces was their triumph over the anopheles mosquito. It was a battle involving science and discipline, waged by the troops, both officers and men, under the pittance of the Medical Corps. During the first stages of the New Guinea Campaign, malaria had been as bitter and deadly a foe as the enemy. On the Papuan front, it had been responsible for more non-effectives than any other single factor. By the time General MacArthur was ready to go into the Philippines, however, it was reduced to secondary importance as a cause of disablement and no longer deserved serious consideration in planning tactical operations. This remarkable achievement, comparable with Goethals' and Gorgas' triumph over yellow fever, was accomplished by the cooperation of everyone who served in New [161] Guinea. The Medical Department surveyed, researched, lectured, demonstrated and recommended, and General Headquarters issued the necessary directives to insure the success of the struggle against malaria. General MacArthur appointed a special committee of representatives, authorities from both the Australian and American medical services, to formulate the general principles under which the campaign would be carried out. Medical officers and Malaria Control Units, specially trained to cope with the menace to the Allied forces in infested areas, waged a bitter war against the mosquitoes, frequently within sound of the enemy's guns.46 Malariologists provided expert advice to unit commanders. Troops were educated to the dangers and prevention of malaria with posters and pamphlets and every man was urged to wage his own personal war against the mosquitoes. The result was complete success. Japanese efforts along these same lines were not nearly so effective. Even as late as the Hollandia operation their malaria casualties continued to assume enormous proportions, despite the fact that they had captured huge quantities of quinine in the Netherlands East Indies.47 As General MacArthur stated: "Nature is neutral in war but, if you beat it and the enemy does not, it becomes a powerful ally." Shortages of equipment and the lack of adequate shipping presented another problem which was solved by the Southwest Pacific Command in its seizure of New Guinea from the Japanese. In addition to the fact that many important items of equipment for both combat and service troops were in short supply right up to the end of operations, the difficulty of handling the necessary tonnage of materiel was increased by the limited port facilities in New Guinea. Construction of bases had to be initiated almost from scratch in the native villages and missionary settlements that constituted the "cities" of New Guinea. Whatever facilities were needed had to be built or brought in as the forces advanced. The jungles and swamps afforded poor foundations upon which to erect the supply and operational bases necessary to carry on a war of rapid maneuver over long distances. Major construction projects were carried out in a primitive area devoid of railroads, highways, shipping facilities, and air transport.48 In many cases, shipment of unit equipment from the United States was lacking in organization and completeness. The initial equipment of a single organization was often transported on many different ships, destined for discharge at various ports. This situation caused much rehandling and reshipping, contributing to the congestion which invariably occurred in all new ports during their more critical periods of development. Equipment shortages of those units about to be employed in forthcoming operations were generally overcome by "crisis management." Equipment in the hands of units not scheduled for immediate combat was transferred to those troops marked for earlier action and loaded on [162] PLATE NO. 47 [163] special ships where water movement was necessary. In some instances, the troops had but little time to familiarize themselves with the weapons they were to take into battle.49 The lack of adequate and suitable water transportation with which to concentrate troops in staging areas and take them into combat at times considerably hampered the planning of operations. Amphibious landing craft were always critically short and liberty type ships had to be used as troop transports, both for assembling troops and for moving supporting elements into objective areas. Such cargo vessels were altered to add necessary facilities by the construction of crude accommodations on deck. Movements of troops in the tropical areas of the Southwest Pacific were accomplished in a manner which would have been utterly impossible in less temperate climates.50 The Battle against Enemy Coastal Shipping The battle against enemy shipping was another significant feature of the New Guinea Campaign. The wholesale destruction by our planes, submarines, and PT boats of enemy coastal vessels, transports, barges, schooners, and sailing craft in the Southwest Pacific Area gradually paralyzed enemy efforts to supply, reinforce, or evacuate the remnants of his armies cut off in New Guinea, New Britain, New Ireland, and the Solomons. (Plate No. 47) More than 5,000 of these craft were destroyed. After the conclusion of the fighting in the Buna-Lae area and the Solomons, the Japanese were reluctant to risk major naval units, and as a result of their heavy losses in cargo ships and transports they were forced to devise a new supply technique. Without additional food, ammunition, and reinforcements, the Japanese forces would be unable to prevent the Allies from seizing all of New Guinea and the adjacent areas. Submarines were too small and unmaneuverable to be of more than minor aid and, moreover, were too few in number. Accordingly, the enemy's most ambitious efforts along these lines were directed to a greatly expanded use of barge traffic. These barges were manufactured and collected in Japan, China, the Philippines, and various island ports and then routed to the New Guinea area. They had a troop capacity of from 35 to 60 men and a cargo carrying capacity of up to 20 tons, and were generally of excellent workmanship. When the enemy's use of small craft for transportation and supply purposes began to assume serious dimensions, the Allies found it imperative to develop effective counter tactics. The answer lay in a coordinated, intensive employment of PT boats, Catalinas, and low flying planes. This combination destroyed the enemy's small craft much faster than they could be rebuilt. The Japanese reacted by emplacing scores of heavy caliber shore batteries to cover their lugger and barge movements. These measures proved ineffective against the fast striking PT boats and planes, however, and the Japanese were forced to abandon daylight traffic almost entirely. Attempts were thereafter confined to movement by night as their barges, restricted by the darkness, crept furtively from cove to cove under cover of elaborate camouflage and security measures. This almost complete interdiction of all water-borne reinforcement was a major factor in the enemy's defeat in New Guinea and demonstrated again the resourceful capabilities of the Allied forces in countering each new threat as it arose. [164] With the end of operations in western New Guinea the Japanese were in an extremely vulnerable position throughout the Pacific. The powerful spearhead of General MacArthur's forces now pointed menacingly only 600 miles below Mindanao. Two whole armies had been destroyed or paralyzed-the Seventeenth Army in the Solomons and the Eighteenth Army in New Guinea-and the remainder of the once powerful Eighth Area Army was scattered and isolated in New Britain and New Ireland. Over a quarter of a million Japanese troops were withering on the vine, virtually erased as a military fighting force. The unhappy strategic situation to which the Japanese had been reduced was further aggravated by Admiral Nimitz's forces which had by-passed Truk and invaded Tinian, Guam, and Saipan in the Marianas, thus tightening the Allied ring which encircled Japan's inner zone of defense. In southwest New Guinea and the Netherlands East Indies, the Allied Air Forces had so successfully neutralized the areas around the Arafura, Banda, and Ceram Seas that it became unnecessary to carry out ground actions in those regions. Japan's air forces beyond the Philippines had been swept from the skies. The constant and implacable pressure exerted by the Allied Air Forces gradually eliminated the enemy's air resources in the Southwest Pacific. Thousands of planes had been destroyed along with experienced pilots and crewmen. Huge stocks of valuable equipment, supplies, and ammunition which the Japanese could not replace, had been completely lost. General MacArthur's conduct of operations along the New Guinea axis had not only yielded large stretches of enemy holdings but had also kept Allied losses in the Southwest Pacific to an extraordinarily low level. By adhering closely throughout his campaign to the four basic principles of war-the principles of mass, surprise, economy, and objective (adherence to a master plan)-he had achieved maximum gains in territory with minimum losses in combat. While Japan's whole defense structure was being rocked to its very foundations, General MacArthur was preparing even stronger blows. The vexing problems of logistics had been largely solved. His newly captured bases, with steadily increasing stock piles of materiel, now assured adequate supplies for his projected drive forward into the heart of the enemy's Pacific possessions-the Philippines.

[165]

|

|||||||