CHAPTER X

WESTERN NEW GUINEA OPERATIONS

By April of 1944, under the impact of General MacArthur's two-pronged offensive against the Japanese forward line in the southeast area and the parallel enemy thrust into the outer defense rampart of the Central Pacific mandated islands, the operational center of gravity in the Pacific theater of war was moving relentlessly closer to the line which the Army-Navy Central Agreement of 30 September 1943 had defined as the boundary of Japan's "absolute zone of national defense."1

In drafting this agreement, Army and Navy strategists recognized that the continuous attenuation of Japan's fighting potential made it unwise, if not impossible, to attempt a decisive defense of the existing Pacific front line under the increasing weight of Allied offensives. Therefore, the mission of the forces in Northeast New Guinea, the Bismarcks, Solomons, Marshall and Gilbert Islands was limited to one of strategic delay, and plans were laid to build a main line of resistance along a restricted perimeter from the Marianas and Carolines to Western New Guinea and the Banda and Flores Seas.2 These were to be flanked by the Bonins and Kuriles to the north and the Sundas to the west.

The essential points of the Army-Navy Central Agreement embodying this vital revision of Central and South Pacific war strategy were as follows:3

1. Key points in the southeast area, extending from Eastern New Guinea to the Solomon Islands, will be held as long as possible by destroying enemy forces whenever they attack.4

2. With a view to the rapid completion of counteroffensive preparations, the following missions will be accomplished by the spring of 1944:

a. Defenses will be strengthened, and tactical bases developed, in the areas of the Marianas and Caroline Islands, Western New Guinea, and the Banda and Flores Seas.

b. Bases will be developed in the Philippines area for strategic and logistic support.

c. Ground, sea, and air strength will be built up in preparation for counteroffensive action.

3. In the event of an enemy approach toward the areas mentioned in paragraph 2a, powerful com-

[250]

ponents of all arms will be concentrated against his main attacking front, and every means will be employed to destroy his forces by counteroffensive action before the attack is launched.

4. After the middle of 1944, if conditions permit, offensive operations will be undertaken from the area including Western New Guinea and the Banda and Flores Seas. Separate study will be made to determine the front on which such operations should be launched, and necessary preparations will be carried out accordingly.

The deadline fixed by Imperial General Headquarters for the completion of preparations along the new defense perimeter was based upon the estimate that full-scale Allied offensive operations against either the Western New Guinea or Marianas-Carolines sectors of the line, or possibly against both sectors simultaneously, would develop by the spring and summer of 1944. Although a six months' period was thus allowed for execution of the program, its actual start was somewhat delayed. Moreover, the scope of preparations envisaged was so vast that it was problematical whether the nation's material and technical resources would be equal to the task.

Primary emphasis in these preparations was placed upon the development of air power. After the bitter lessons taught by the southeast area campaigns of 1942-43, Army and Navy strategists unanimously agreed that the air forces must be the pivotal factor in future operations, whether defensive or offensive. To successfully defend the new "absolute defense zone" against the steadily mounting enemy air strength, they believed it imperative to have 55,000 planes produced annually. At the same time a large number of air bases, echeloned in depth and mutually supporting, had to be built and equipped over the widely dispersed areas of the new defense zone.

To meet the first of these requirements was impossible considering the current production level and the overall natural resources.5 Therefore, at the Imperial conference of 30 September 1943, a compromise was reached which set a production goal of 40,000 planes for the fiscal year 1944, a goal still thought extremely difficult to attain. The airfield construction program was equally ambitious. In the area embracing Western New Guinea, the Moluccas, Celebes, and the islands of the Banda and Flores Seas, where the existing number of fields totalled only 27, plans were laid for the construction of 96 entirely new airfields and the completion of 7 others already partially built, bringing the total number of airfields planned for the area to 120.6 This program was to be completed by the spring or, at latest, by the summer of 1944.

Although the central strategic concept of the new defense zone was one of powerful air forces rapidly deployable to prepared bases in any threatened sector, it was also obviously essential to build up adequate ground defenses to protect these bases from attack. In the early stages of the war, troops and materiel had been thrown into the exterior perimeter of advance, and development of a reliable inner defense system had been neglected. The powerful Allied offensives of 1943 in the southeast area aggravated this situation by drawing off and consuming a large portion of Japanese war strength, with the result that rear-area defenses in Western New Guinea, the Carolines and Marianas remained seriously weak and, at some points, non-existent. The

[251]

plan to forge these areas into a main line of resistance consequently necessitated the movement of substantial troop reinforcements and a large volume of supplies.

In view of Russia's continued neutrality and a relatively quiet situation on the China front, Imperial General Headquarters decided to redeploy a number of troop units from the Continent to the areas along the new Pacific defense line. The transportation of these units, however, presented a difficult problem because of the serious depletion of ship bottoms. The Army and Navy pressed for the allocation of additional non-military shipping to military use, but the tonnage demanded was far in excess of what could be spared without impairing the movement of raw materials urgently required for the war production program. The compromise figure of 250,000 tons finally agreed upon at the Imperial conference of 30 September was barely enough to compensate for losses of military shipping in current operations.7 However, it was considered the maximum that could be drawn from the nonmilitary shipping pool, which itself was below existing requirements.8

The critical shipping situation and the difficulties of procuring defense equipment greatly retarded the reinforcement of the new defense zone. At the end of 1943 the Marianas and Carolines, forming a vital sector of the perimeter line, were still garrisoned only by skeleton naval base forces.

Western New Guinea, lying directly astride the axis of General MacArthur's advance, also was weakly held by scattered naval base units and Army line of communications troops. The only sector adequately manned was the southern flank of the line in the Banda and Flores Seas area, the defenses of which had been comparatively well organized by the Nineteenth Army, with headquarters at Ambon.9

To provide for the defense of Western New Guinea, Imperial General Headquarters had decided at the end of October to transfer from Manchuria the headquarters of the Second Army, commanded by Lt. Gen. Fusataro Teshima, and to assign to it two first-line divisions, the 3d and 36th, then stationed in China. At the same time, it was decided to relieve the Second Area Army headquarters of its current duties in Manchuria and to place it in command of both the Second and Nineteenth Armies, thus unifying the direction of Army forces in the Western New Guinea and BandaFlores Sea sectors.10 General Korechika Anami, Second Area Army commander, provisionally established his headquarters at Davao, in the southern Philippines, on 23 Novem

[252]

ber,11 and on 1 December assumed operational command of the Second and Nineteenth Armies, the 7th Air Division, and the 1st Field Base Unit.12 Also by 1 December, Second Army headquarters had moved to Manokwari, Dutch New Guinea, where Lt. Gen. Teshima took command of forces in the assigned Army area.

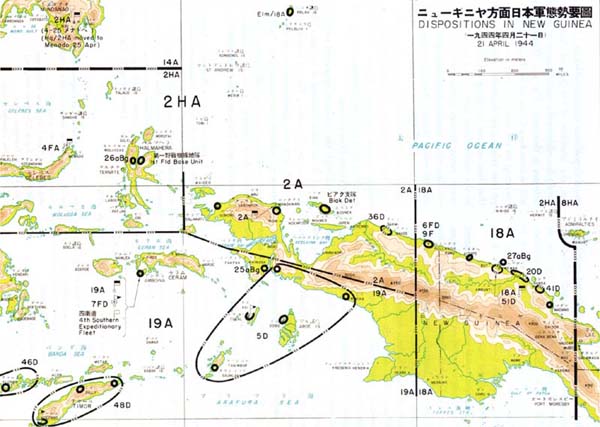

The operational zone assigned to the Second Area Army extended on the west to the Makassar and Lombok Straits, on the north to five degrees N. Latitude, and on the east to the 140th meridian, which marked the boundary with the Eighth Area Army. (Plate No. 64) Within this zone, the Area Army was to exercise direct command over the northern Moluccas, northeastern Celebes, and Talaud Islands. The Nineteenth Army remained charged with operations in the Banda-Flores Seas area, and the Second Army was assigned responsibility for all of Dutch New Guinea west of the 140th meridian.13

Imperial General Headquarters instructed General Anami that the main defensive effort of the Area Army should be made in Western New Guinea. However, when the new command dispositions went into effect on 1 December, the situation of the Second Army was hardly favorable for the establishment of strong defenses in this area. The 36th Division was still en route from China, while the 3d Division, operating on the Central China front, had not yet been released for shipment, with the result that there was not a single ground combat unit in the entire Army zone. Nor could Nineteenth Army furnish reinforcements since its two (later three combat divisions were scattered over the many islands of the Banda and Flores Seas, then still considered a vital sector of the defense zone.14 Moreover, the shortage of shipping and the menace of Allied air and submarine attacks militated against the ready transfer of units from the Nineteenth Army area to Western New Guinea.

Although the situation improved with the arrival of the main elements of the 36th Division15 on 25 December, Second Army troop strength was still inadequate to assure the defense of its broad operational zone. Pending final formulation of an over-all defense plan for Western New Guinea, Lt. Gen. Teshima stationed the 36th Division (less 222d Infantry at

[253]

PLATE NO. 64

Dispositions in New Guinea, 21 April 1944

[254]

Sarmi. The 222d Infantry, reinf. was dispatched to Biak Island to begin organizing the defenses of that strategic position.

The Second Army's plan for the defense of Western New Guinea emphasized the importance of securing Geelvink Bay. This plan was based upon the availability of only two divisions, the troop strength originally allotted by the High Command. The three key positions in this defense scheme were the SarmiWakde area, Biak Island, and Nianokwari.16 As finally decided on 8 January, the outline of planned strength dispositions was as follows:17

Sarmi-Wakde: One division (less one inf. refit.)

East Japen: One inf. regt. (reinf.)

Koeroedoe I.: One inf. regt. (reinf.)

Noeboai: One inf. regt. (reinf.)

Biak: One division (less one regiment)

Manokwari: One regt. (less one battalion)

Wissel Lake: One battalion

Under this plan, the 222d Infantry was to continue its interim mission of organizing the defenses of Biak Island until relieved by the 3d Division. The regiment would then proceed to garrison the east Geelvink Bay sector.

While initial attention was focussed on the Geelvink Bay area, the Second Area Army command was also concerned over the weak condition of the defenses of Hollandia, which lay just east of the 140th meridian in the Eighth Area Army zone of responsibility. An order to dispatch an element of the 36th Division to that sector was issued but was quickly revoked on the ground that it would weaken the defenses of Geelvink Bay without appreciably strengthening Hollandia.18 A large section of the New Guinea coast between Wewak and Sarmi thus remained practically undefended. General Anami promptly dispatched a staff mission to Eighth Area Army headquarters at Rabaul to press for reinforcement of the Hollandia area, and a similar recommendation was communicated to Imperial General Headquarters during December. The 6th South Seas Detachment (two battalions), temporarily stationed on Palau, was dispatched by the High Command. No other action was taken, however, since both Eighth Area Army and Eighteenth Army, after the loss of Finschhafen, were more immediately concerned with checking further enemy penetration of the Dampier Strait region.

Though unsuccessful in obtaining action on Hollandia, General Anami continued to press the organization of defenses within the Second Army zone in Western New Guinea despite severe handicaps. Troop strength remained seriously short, and in addition the prospects of adequate air and naval support were discouraging. The 7th Air Division, with headquarters on Ambon, in the Moluccas, was the only air unit assigned to Second Area Army and was currently recuperating from heavy losses. Operations in eastern New Guinea between August and November, had cut down its strength to only about 50 operational aircraft.19 This meager force was devoted almost exclusively to shipping escort missions in the rear areas.

The prospects for naval air support were no more encouraging. In case of an enemy attack directed at Western New Guinea, the Second Area Army could count upon the cooperation of the 23d Air Flotilla based at Kendari, in the Celebes, but the operational strength of this unit was likewise down to about 50 planes, and most of its experienced pilots had been transferred to the naval air forces at Rabaul during

[255]

the Solomons and Papuan campaigns.20 Moreover, despite the withdrawal, of the main defense line to Western New Guinea and the Carolines, the Navy continued to maintain its most efficient carrier flying units on land bases in the Rabaul area to serve as a forward strategic air barrier. This policy resulted not only in the steady depletion of the fleet air arm but in the immobilization of the carrier strength which otherwise might have been capable of providing air support at any threatened point of the main defense line.

The only naval surface combat forces in the immediate vicinity of the Second Area Army operational zone were the 16th Cruiser Division (Ashigara, Kuma, Kitakami, Kinu) and the 19th Destroyer Division (Shikinami, Uranami, Shigure), both under command of the Southwest Area Fleet with headquarters at Soerabaja. Charged with naval missions covering the area from the Indian Ocean to Western New Guinea, this fleet obviously had insufficient strength to provide support against an eventual enemy attack against the north coast of Dutch New Guinea. Meanwhile, the Second Fleet, containing the bulk of the Navy's battleships, was in the Truk area. Without attached carrier forces, however, its role was not offensive but merely to act as a fleet-in-being to deter enemy attack.

Naval ground forces in Western New Guinea under the command of the Fourth Expeditionary Fleet stationed at Ambon, were weak and uniformly small. During earlier operations in the southeast area, Army troops had received substantial support from naval base forces and special landing forces, but in Western New Guinea the naval base forces were too small. These were widely scattered at Hollandia, Wakde, Manokwari, Nabire, and Sorong.21

In the light of these unfavorable conditions, it was obvious that Second Area Army could not accomplish the organization of Western New Guinea defenses without substantial reinforcements of well-trained and well-equipped line units, as well as air strength. In midJanuary, therefore, General Anami forwarded an urgent request to Tokyo for more troops. Imperial General Headquarters responded promptly with a plan to allot 15 infantry battalions, three heavy artillery regiments, and one tank regiment, in addition to the 14th Division, which the High Command now planned to assign to Second Area Army in place of the 3d Division.22

These reinforcements, together with the necessary service and supply elements, would boost the strength of the Area Army from approximately 170,000 to about 320,000 troops. The 14th Division was scheduled to arrive by the end of March, while the other combat units were to complete their movement to Western New Guinea by May.23 The transport of service troops was to continue through July.

[256]

As a further step to bolster the southern sector of the national defense zone, Imperial General Headquarters in December 1943 began contemplating an important modification of the command dispositions then in force. Principally to assure the mobility and economical use of air power and shipping resources, it was proposed to combine the Fourteenth Army in the Philippines and the Second Area Army in the Western New Guinea-eastern Dutch East Indies area under the higher command of Southern Army, at the same time restricting them to ground forces only and placing the Third and Fourth Air Armies, as well as shipping groups, directly under Southern Army command. Such a step was also deemed necessary to assure that Southern Army would transfer primary emphasis from the Asiatic mainland to the Pacific front, now clearly the decisive battlefront of the war.24

Before this proposal had a chance to reach concrete form, developments on the Central Pacific front temporarily usurped the attention of Imperial General Headquarters, with the result that the final orders directing the modification of the command set-up were not issued until 27 March 1944. The effective date of the new dispositions was fixed at 15 April.

Setbacks to Defense Preparations

The suddenly increased tempo of the enemy advance in the Central Pacific during February gave rise to strong belief that an amphibious assault might develop against the Marianas or Carolines sector of the main defense line at any time.25 This impending danger led the Army and Navy High Commands to press successfully for the transfer to military use of an additional 300,000 gross tons of nonmilitary shipping during the months of February, March and April.26

First priority was assigned by Imperial General Headquarters to the movement of troops, munitions, and supplies to the Marianas and Carolines. Since military tonnage, despite the scheduled 300,000-ton increase, still fell below requirements, this decision necessitated the deferment of scheduled troop and supply shipments to other areas. In the latter part of February Imperial General Headquarters notified General Anami that the shipping allocation to second Area Army was being temporarily suspended due to the urgency of the Central Pacific situation. This of course meant a critical delay in the program to reinforce Western New Guinea.27

[257]

The suspension also led to changes in troop allocation plans. The 14th Division, previously allotted to Second Area Army, was reassigned on 20 March to the newly-activated Thirty-first Army for the defense of the Marianas and Carolines.28 In its place Imperial General Headquarters early in April assigned the 35th Division to Second Area Army, directing employment of the division main strength on Western New Guinea.29 However, the actual movement of the division main elements from China still had to await restoration of Second Area Army's shipping allocation.

In addition to, and partially as the result of, the shortage of shipping, slow progress in both the aircraft production and airfield construction programs seriously undermined the entire plan for the new Pacific defense line. Average monthly production for the period JanuaryApril 1944 was about 2,200.30 This did not augur well for the attainment of the production goal of 40,000 planes for the fiscal year 1944. The prospects were even darker due to the fast dwindling cargo-carrying bottoms resulting from the transfer to the military of 30,000 tons and the tremendous losses from enemy action in recent months.

The ambitious air base construction program for Western New Guinea and the eastern Netherlands East Indies had meanwhile bogged down seriously. In these areas even combat units had been put to work as labor troops in an effort to carry out the plans formulated by Tokyo, but shortages of materials, transportation capacity, available field labor, and mechanized equipment, together with deficiencies in engineering technique, slowed down progress to a minimum. Less than onethird of the projected bases was completed by the time they were critically needed, and the funneling of effort into their construction materially delayed other operational preparations by the field forces. Of the 35 new airfields planned for the Western New Guinea area, only nine were available for use by the end of April 1944. All other installations used by the air forces during the Western New Guinea campaign had already been in existence prior to the start of the construction program.31

Despite the lack of progress in aircraft production and the building of new bases, the Army and Navy made serious efforts to replenish their first-line air strength, both in planes and pilots, in preparation for decisive

[258]

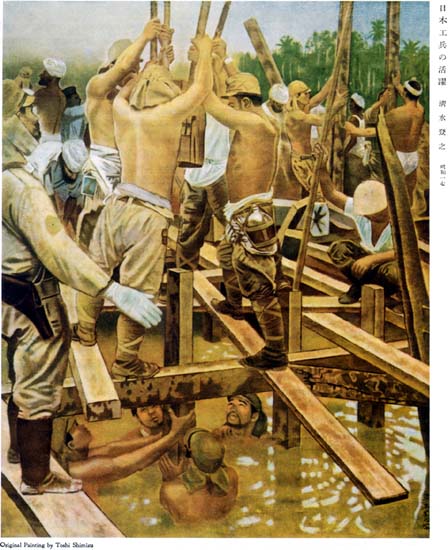

PLATE NO. 65

Japanese Engineer Activities in South Pacific

[259]

battle along the new defense line. During the latter part of February, the Navy began deploying the newly trained and constituted First Air Fleet, commanded by Vice Admiral Kakuji Kakuta, to the Marianas and Carolines. The primary mission of the Air Fleet was to counter any enemy attack in these two sectors, but it was also to extend its cover to Western New Guinea. The deployment had barely begun, however, when a heavy setback was received. On 23 February, enemy carrier forces struck the Marianas, and in the engagement most of the planes of the First Air Fleet advance echelon, which had just arrived from the homeland, were either destroyed or heavily damaged.32

The Fourth Air Army in Northeast New Guinea, now consisting of only the 6th Air Division and 14th Air Brigade, was also under increasing enemy pressure. On 25 and 26 March Allied planes struck in force at the Air Army's Wewak bases. Only a few elements remained there at the time of these attacks, since the Air Army headquarters and the bulk of its strength had displaced to Hollandia on 25 March coincident with the transfer of all Army forces in Northeast New Guinea to Second Area Army command.33 However, the attacks rendered Wewak useless as a forward base, and between 30 March and 3 April the Allied air forces extended their attacks to the Hollandia area. There they succeeded in destroying not only most of the Fourth Air Army's remaining combat strength, but a large number of aircraft transferred earlier from Sumatra.34

In the closing days of March, new naval developments in the Central Pacific rendered it painfully certain that Japanese defenses in Western New Guinea would have to bear the brunt of enemy amphibious attacks without opposition by the main strength of the fleet. At this time, Admiral Mineichi Koga, Commander-in-Chief of the Combined Fleet, was aboard his flagship, the 64,00-ton battleship Musashi, at Koror Anchorage in the Palau Islands, where he also had at his disposal Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita's Second Fleet.35 However, the Navy's carrier forces (all of which had been assigned to the Third Fleet were) dispersed at Singapore and in the home islands undergoing reconstitution and training.

This was the situation when, on 26 March, Admiral Koga received reports that a strong American carrier force was moving into the waters between Palau and Western New Guinea. Without carrier strength of his own, Admiral Koga decided that the circumstances were not propitious for the decisive battle which was the central objective of the Combined Fleet.36 He therefore released the Musashi to Vice Adm. Kurita and ordered the latter to put to sea with the Second Fleet, while the Combined Fleet headquarters transferred ashore. The fleet battle forces sortied on 29

[260]

March to await further orders in the waters northwest of Palau. At the same time the First Air Fleet was ordered to dispatch landbased fighter strength to Palau as speedily as possible to operate against the enemy task force. First Air Fleet attack bombers were to continue operating from the Marianas.37

From dawn of 30 March until dusk on 1 April, aircraft from the enemy carriers carried out devastating raids on the Palau Islands, Yap, and Woleai. Land installations were severely damaged; two destroyers and 22 fleet auxiliaries and merchant ships were sunk; and anchorages and channels were sewn with magnetic mines. Attempts by First Air Fleet planes to stem the attacks only resulted in heavy losses, totaling more than l00 aircraft, with comparatively little damage to the attacking force.38 Moreover, Admiral Koga and part of his staff were lost while flying from the main island of Palau to Davao to transfer Combined Fleet headquarters.39

Aircraft losses in the Carolines battle so reduced the strength of the First Air Fleet that it was no longer capable of any significant contribution to the defense of Western New Guinea. In addition, the Second Fleet, deprived of the use of its base at Koror Anchorage, was ordered to return to home waters to reorganize and continue preparations for future decisive battle. The Second Area Army thus lost all hope, at least for the time being, of obtaining naval air or surface support from the Central Pacific.

The beginning of April 1944 found Imperial General Headquarters still concerned primarily with preparations to defend the Marianas and Carolines against threatened American attack from the Central Pacific, but also forced to pay heed to mounting signs of an early offensive by MacArthur's forces in the New Guinea area. The carrier strike against the western Carolines at the end of March, together with the rising tempo of air attacks on Japanese bases along the north coast of New Guinea, seemed to foreshadow such a move. At the same time, there was an ominous intensification of enemy espionage and amphibious patrol activity along the coast from Madang as far west as Hollandia.40

[261]

PLATE NO. 66

Army Day Poster: "Develop Asia"

[262]

Ever since the invasion of the Admiralties, the Eighteenth Army command had anticipated a new Allied amphibious operation against the Northeast New Guinea coast by March or April of 1944, but it had estimated that the target area would be somewhere to the east of Wewak.41 With the carrier raid on Palau and the extension of Allied air attacks to Hollandia, a section of the Eighteenth Army staff saw an increasing possibility that the objective would lie farther west, not excluding even the distant Hollandia area. However, the estimate finally accepted still placed the most likely area of attack between Madang and Hansa Bay, including Karkar Island. Wewak was rated the next most probable target, with Hollandia least likely but not entirely excluded.42

One reason for Eighteenth Army's minimization of the immediate danger to Hollandia was the belief, based on past observation of General MacArthur's tactics, that landing operations in that area would not be attempted until advance bases had been taken, from which land-based Allied air forces (including fighters) could neutralize Japanese air bases to the west of Sarmi and also provide direct support to the landing forces.43 With the most advanced Allied bases located at Saidor and in the Admiralties, almost 500 miles from Hollandia and over 600 miles from Sarmi, it was considered almost certain that General MacArthur's next move would be aimed at seizing a forward fighter base somewhere between Madang and Aitape, in preparation for a later invasion of Hollandia.

The fighter-escorted bomber raids on Hollandia in early April forced an upward revision of the calculated capabilities of enemy fighters from existing bases.44 They did not modify Eighteenth Army's estimate of enemy offensive plans, however, since effective fighter range for the continuous type of support required in amphibious landing operations was still believed to be only about 300 miles. The possibility that carrier forces might be borrowed from the Central Pacific to provide tactical support was gravely underestimated since none of General MacArthur's previous invasion operations had been furnished such support.

Other enemy actions also were instrumental in strengthening Eighteenth Army's belief that the next blow would fall in the MadangWewak area. One was the unleashing in March of a heavy air offensive directed at the coastal area from Wewak eastward, with Wewak itself and Hansa Bay as the main targets; another was a marked augmentation of enemy motor torpedo boat activity from Dampier Strait west to Hansa Bay.45

Although the next Allied effort was thus expected to fall short of Hollandia, both Imperial General Headquarters and Second Area Army were strongly convinced that this valuable base would subsequently be attacked, possibly

[263]

as early as June.46 Not only were the major base facilities of Fourth Air Army located in the area, but Hollandia had become an important staging point on air transport routes to Japanese-held areas farther east,47 as well as the chief port for logistic support of the Eighteenth Army. Huge amounts of military supplies were in open storage along the shore of Humboldt Bay. All these factors made it appear highly probable that the enemy eventually would seek to wrest Hollandia from Japanese control, especially since it would give the Allies a welldeveloped air and sea base, valuable as a stagingpoint for large-scale amphibious operations.

Despite growing awareness of the need to bolster Hollandia's defenses, Eighteenth Army was in no position to take immediate steps to that end. Although the Army Commander had issued orders on 10 March for a strengthening of Aitape, Wewak, and Hansa Bay, the Army was experiencing great difficulty in moving troops westward from Hansa Bay because of the shortage of sea transportation and heavy enemy air interference from forward bases at Nadzab and Saidor.48

Nevertheless, when Second Area Army assumed operational control of Eighteenth Army and Fourth Air Army on 25 March, General Anami promptly ordered Eighteenth Army to move as soon as possible to the west of Wewak and consolidate the defense of air bases, with particular emphasis on the installations at Aitape and Hollandia. Pursuant to this order, Lt. Gen. Adachi revised the existing plan for redeployment of Eighteenth Army forces along the following lines:49

1. 51st Division to move to Hollandia instead of to Wewak.

2. 41st Division to assume the mission of garrisoning Wewak instead of Hansa Bay.

3. 10th Division to garrison Aitape, as previously planned.

Eighteenth Army immediately threw its full effort into the execution of the revised plan, but from the outset it faced severe difficulties. Use of sea routes, normally traversable in a few days, was interdicted by Allied air and sea superiority, leaving no alternative but time-consuming movement overland. Roads were nonexistent, and the native tracks leading west from Hansa Bay crossed two large rivers, the Ramu and Sepik, which were completely unfordable near the coast, and the mouths of which were flanked by broad stretches of almost impassible mangrove swamplands.50 Troop movements were further hampered by the necessity of keeping

[264]

constantly on the alert for an enemy surprise landing.

As later events proved, even had Eighteenth Army been able to adhere to its own timetable for these movements, they would not have been completed in time to meet the Allied attack at Hollandia. Given the most favorable conditions, the first echelon of the 51st Division, consisting of three infantry battalions, was not expected to reach Hollandia until late in May. The 20th Division meanwhile was held up on the east bank of the Ramu by the shortage of boats, and its first elements were unable to leave Hansa Bay for Aitape until early April.

As a stop-gap measure pending the arrival of the 51st Division, Eighteenth Army in early April dispatched Maj. Gen. Toyozo Kitazono, 3d Field Transport Unit commander at Hansa Bay, to Hollandia in order to assume direction of ground defense preparations by the miscellaneous army units already in that area. Just prior to Maj. Gen. Kitazono's arrival on April 10, Vice Adm. Yoshikazu Endo had temporarily transferred Ninth Fleet51 headquarters from Wewak to Hollandia. Fourth Air Army headquarters also was still at Hollandia at this time but withdrew to Menado immediately after the Air Army's transfer to direct Southern Army command became effective on 15 April. This left Maj. Gen. Masazumi Inada, who had arrived on 11 April to take command of the 6th Air Division, the highest Army air commander.52

Due to the brief lapse of time between the arrival of the new commanders and the Allied assault on Hollandia, no local agreement for the coordinated use of all forces had yet been reached when the attack came.53 These forces aggregated about 15,000, including all ground, air and naval personnel, of which about 1,000 were hospitalized ineffectives. Approximately 80 per cent of the total strength consisted of service units.54 Combat air strength was

[265]

also pitifully weak. The 6th Air Division had only a handful of aircraft still operational, and chief reliance was placed on the Navy's 23d Air Flotilla, which transferred its headquarters on 20 April to Sorong, on the Vogelkop Peninsula. The greater part of its strength began operating from a newly completed base on Biak.55

This was the situation of Hollandia's defenses when, on 17 April, the naval communications center at Rabaul radioed a warning that Allied landing operations might be expected imminently at some point on the New Guinea coast. Radio intercepts by Japanese signal intelligence revealed that Allied air units from Lae, Nadzab and Finschhafen were concentrating in the Admiralties, and that a large number of enemy ships was moving in the Bismarck Sea, maintaining a high level of tactical radio traffic.

Two days later, on 19 April, a patrol plane of the Carolines-based First Air Fleet sighted a large enemy naval force, including aircraft carriers, moving north of the Admiralties.56 The same day, an army reconnaissance flight from Rabaul spotted a second convoy of about 30 transports, escorted by an aircraft carrier, two cruisers and ten destroyers, passing through the Vitiaz Strait. On the 20th, two large enemy groups-one a task force with four carriers and the other an amphibious convoy-were reported standing westward just north of the Ninigo Islands, about 200 miles due north of Wewak.

From the course which these forces were taking, no accurate prediction was yet possible as to where the enemy would land. However, the invasion force now turned suddenly southward and, on 21 April, launched simultaneous air strikes at three different places-Hollandia, Aitape, and the Wakde-Sarmi area. So violent were these attacks that the local forces in each area believed that their own sector would be the main target of invasion.

At Hollandia the enemy air preparation began at dawn on 21 April and continued without interruption until late afternoon. Wave after wave of both carrier and land-based planes, numbering approximately 600, pounded the area, inflicting severe damage, particularly on the three airfields located in the vicinity of Sentani Lake. The simultaneous attacks on Wakde and Sarmi, though less protracted, were equally devastating. Virtually all base installations in the three places were completely wrecked, and the last few operational aircraft of the 6th Air Division were destroyed. Combat air strength to the east of Sarmi was now reduced to nothing.

Beginning at 0530 on 22 April, carrier planes again struck at the Hollandia airfields and also at the beaches along Tanahmerah and Humboldt Bays. Combat ships entered both bays and laid down a heavy barrage of naval gunfire, while three carriers approached within approximately nine miles of the shore. Under cover of this close support, the enemy rapidly put ashore the largest landing force thus far thrown against any Japanese-held point in New Guinea.57 Part of the force landed at Humboldt Bay, while a second contingent went ashore at Tanahmerah. (Plate No. 67) The Japanese forces defending both areas,58 stunned by the

[266]

PLATE NO. 67

Hollandia Operation, April-June 1944

[267]

weight of the air and artillery preparation and without adequate prepared positions on which to make a stand, were forced to withdraw. By noon of 22 April, the entire beach and port areas around both Humboldt and Tanahmerah Bays were completely occupied by the enemy.

Simultaneously with the Hollandia invasion, Allied amphibious forces had also effected a landing in the strategic Aitape sector, about 125 miles east of Hollandia. At 0500 on 22 April, enemy warships began a two-hour bombardment of Aitape itself, of the Tadji airfield sector eight miles southeast of Aitape, and of Seleo Island, lying several miles offshore from Tadji. Under cover of this preparation, enemy troops landed near the Tadji airfield, where the Japanese garrison force of about 2,000, incapable of serious resistance, withdrew after a few skirmishes.59 The airfield was immediately seized by the enemy, who had fighters based there by 24 April.

With the Japanese ground forces in both attack areas unprepared to offer a real defense, the initial reaction to the Allied landings necessarily was limited to air counterattacks. These were handicapped by the small number of planes available, but were prompt and partially effective. The 23d Air Flotilla, operating at extreme range from Sorong,60 carried out night attacks with medium torpedo bombers against Allied surface craft on 22, 23, and 24 April. Elements of the 7th Air Division, which had advanced to Sorong from the Nineteenth Army area, joined in the attacks on the night of the 24th.

Still subjected to heavy enemy air and naval bombardment and lacking unified command, the defense forces on the Hollandia front had meanwhile fallen back on the Sentani Lake airfield sector. Here they were cut off from their ration and ammunition supplies, which were stored near the coast, and faced the hopeless prospect of conducting the defense of the airfields with less than a week's rations, very little small arms and machine gun ammunition, and no artillery. When enemy forces, advancing simultaneously from the Humboldt Bay and Tanahmerah beachheads, converged on the airfield sector on 26 April, the defenders were obliged to withdraw toward Genjem to escape being trapped, and all three airfields were occupied by the enemy.

On the night of 27 April, 23d Air Flotilla planes again attacked enemy shipping off Hollandia, claiming one light cruiser sunk and another large vessel damaged.61 It was too late,

[268]

however, for such attacks to have any appreciable effect on the ground situation, and due to the prohibitive losses inflicted by enemy night fighters and antiaircraft fire, the air offensive was discontinued.

By, 7 May approximately 10,000 army and navy personnel had concentrated in the Genjem area, 20 miles west of Hollandia, where a large truck farming operation afforded limited food supplies.62 Maj. Gen. Inada, 6th Air Division commander, now assumed command of all troops, organized them into several echelons, and initiated a general withdrawal toward Sarmi.63

While these developments were under way, Second Area Army headquarters at Davao had been giving urgent study to the situation created by the unexpectedly early Allied invasion of Hollandia. Immediately upon learning of the enemy landings on 22 April, General Anami took the optimistic view that the enemy had overreached himself by launching an amphibious assault at such great distance from his bases. He calculated that the local forces at Hollandia, despite deficiencies in training and equipment, would be able to offer at least partially effective resistance until adequate countermeasures could be taken by Eighteenth Army. In the meantime, he estimated that the morale of the garrison could be bolstered and its resistance stiffened by the dispatch of a small token force to Hollandia by Second Army. On the same day, therefore, he sent the following order to Lt. Gen. Teshima:64

The Second Army Commander will immediately dispatch two battalions of infantry and one battalion of artillery (from the 36th Division) to the Hollandia area, where they will come under the command of the Eighteenth Army Commander.

General Anami's optimistic estimate of the situation changed, however, as ensuing reports indicated that the enemy, using forces of considerable size, had easily established beachheads not only at Hollandia but at Aitape. The latter move obviously would render extremely difficult any attempt to move the main body of the Eighteenth Army westward to bolster Hollandia. At the same time, it was apparent that the loss of Hollandia, giving the enemy an advance base of operations against Western New Guinea while the Geelvink Bay defenses were still incomplete, would gravely imperil the southern sector of the absolute defense line.

In General Anami's judgment, these considerations dictated a more aggressive employment of Second Army forces. He estimated that the enemy's plans envisaged following up the Hollandia invasion by an assault on Biak or possibly Manokwari, by-passing Sarmi entirely or attacking it only as a secondary effort. Reinforcement of both Biak and the Manokwari area thus appeared vitally necessary. However, rather than pull back the forward strength of the 36th Division for this purpose, General Anami decided to risk waiting for the arrival of the 35th Division from China and Palau.65

[269]

Meanwhile, in view of the lesser danger to Sarmi, he felt that it was pointless to keep the 36th Division idle in that area when it might be used in an effort to smash the enemy at Hollandia, in conjunction with an Eighteenth Army attack from the east. He therefore decided to modify the original plan for dispatch of a token force in favor of a major counteroffensive by the main strength of the 36th Division.

Pursuant to this decision, Second Area Army ordered the Second Army on 24 April to prepare to send the main strength of the 36th Division from Sarmi to Hollandia.66 On the same date, General Anami radioed an urgent recommendation to Imperial General Headquarters, Southern Army, the Combined Fleet, and the Southwest Area Fleet that all forces at Sarmi be committed in an attempt to retake Hollandia, and that strong naval forces be rushed to Western New Guinea to block any Allied leap-frog operation toward the Geelvink Bay area.

Neither Southern Army nor Imperial General Headquarters reacted favorably to the recommendation despite the dispatch of Lt. Gen. Takazo Numata, Second Area Army chief of staff, to Singapore in an effort to press the plan upon Southern Army headquarters.67At the same time, both Lt. Gen. Teshima, Second Army commander, and Lt. Gen. Hachiro Tanoue, 36th Division commander, indicated that they likewise questioned the advisability of the plan. Finally, on 27 April, the Combined Fleet replied that naval strength adequate to support the plan would not be available until about the middle of May.68

Although unable to gain support for his plan to commit the 36th Division in an immediate counterattack against the enemy at Hollandia, General Anami allowed his order of 24 April to remain in effect so that the division would continue preparations facilitating its eventual use as a mobile force to be moved quickly to any threatened sector. Nor did he rescind the earlier order for dispatch of a token force to the Hollandia area. The 36th Division assigned this mission to two infantry battalions of the 224th Infantry Regiment, reinforced by half the regimental artillery battalion. After completing its preparations, this force, under Col. Soemon Matsuyama, 224th Infantry commander, started out from the Sarmi area on 8 May via overland routes. By this date, the enemy was in firm possession of Hollandia and was already using the airfields for operational purposes.

Meanwhile, far to the east, the Eighteenth Army command independently revised its own operational plans in the light of the radically altered situation created by the Hollandia and Aitape landings. The main body of the Army, numbering close to 55,000 troops, including air force ground personnel and naval units, now found itself cut off from all outside sources of supply and deprived, by a combination of geography, the enemy, and insurmountable difficulties of movement, of every possibility of rejoining the Second Area Army forces west of Hollandia for the crucial defense of Western New Guinea.

Faced by the certainty that starvation and disease would gradually destroy his forces even if they remained passively in their present positions, Lt. Gen. Adachi decided that it was preferable to undertake active operations before the fighting strength of the troops was entirely dissipated. More important, he saw the possi

[270]

PLATE NO. 68

Deadly Jungle Fighting: New Guinea Front

[271]

bility that bold counterattacks by Eighteenth Army against the enemy's rear might force the diversion of Allied forces eastward, thus hampering the massing of enemy strength against the dangerously weak defenses of Western New Guinea.69

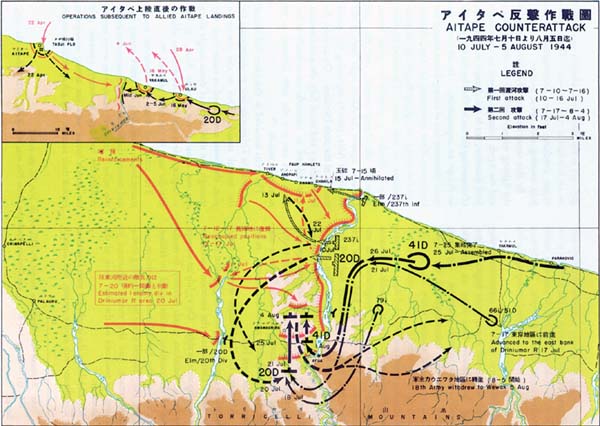

Acting swiftly to implement his decision, Lt. Gen. Adachi issued orders to the 20th, 41st and 51st Divisions on 26 April to prepare to move forward for a counterattack against the enemy beachhead at Aitape. On 7 May, advance elements of the 20th Division, then the farthest west of the Eighteenth Army's forces, began advancing toward Aitape from the Wewak area and, by early June, had driven in enemy outposts to reach the Driniumor River, about 12 miles from the main objective at Tadji airfield.70

Hollandia nevertheless was irrevocably lost, depriving the Japanese forces of their most valuable remaining air base and port on the northern coast of New Guinea. On the other hand, General MacArthur's forces had won an important forward base of operations seriously jeopardizing Japanese hopes of holding the absolute defense zone and the approaches to the Philippines.71

Failure of the Reinforcement Plan

Almost on the eve of the Allied invasion of Hollandia, a temporary easing of the shipping situation finally made it possible for the Japanese High Command to act on its long-delayed plan to move substantial troop reinforcements to Western New Guinea. Early in April, Imperial General Headquarters restored the shipping allocation of the Second Area Army and on 9 April directed the immediate movement from China of the main elements of the 35th Division.72

Pursuant to this directive, the Navy's General Escort Command organized a special convoy, designated Take No. 1 and consisting of nine large transports.73 The convoy was to carry, in addition to the 35th Division main elements, the 32d Division which had been

[272]

assigned to Fourteenth Army for the reinforcement of Mindanao. Protected by an unusually large naval escort, the convoy sailed from Shanghai on 17 April en route to Manila.

On the night of 26 April, four days after the start of the Hollandia invasion, the Take convoy encountered its first disaster in the waters northwest of Luzon. In a sudden attack by enemy submarines, one of the transports carrying one regiment of the 32d Division was sunk with the loss of virtually the entire regiment.74 The rest of the convoy continued on to Manila, where it arrived 29 April.

In the interim between the convoy's departure from Shanghai and its arrival at Manila, Imperial General Headquarters had suddenly altered the assignment of the 32d Division, transferring it to direct command of Second Area Army. This was due to realization that unless swift action was taken under the still unimplemented plan to strengthen Second Area Army by 15 battalions, the mounting danger to shipping movements into forward areas might completely bar execution of the reinforcement plan. Hence, when the Take convoy resumed its voyage from Manila on 1 May, it still carried the 32d Division.

To lessen the danger of enemy submarine attack, the convoy took a special route laid out by the Third Southern Expeditionary Fleet. In broad daylight on 6 May, however, the convoy was struck again as it neared the northeastern tip of the Celebes. Enemy torpedoes hit and sank three transports in rapid succession.

Although rescue operations were relatively successful, the 32d Division was reduced to only five infantry battalions and one and a half artillery battalions, while the two infantry regiments of the 35th Division were down to four battalions, with only a battery of artillery.75 The surviving ships of the convoy, carrying these troops, put in at Kaoe Bay, Halmahera, on 9 May.

Meanwhile, the definitive loss of Hollandia had seriously compromised Second Area Army's hopes of safely moving reinforcements into Western New Guinea, even from the nearby Halmahera area. The enemy now had an operating base within easy fighter range of Sarmi, Biak, and the Geelvink Bay area, while Allied bombers could strike at Sorong and Japanese ports and bases in the Moluccas. Japanese air strength was totally inadequate to meet this challenge. In view of the insufficient progress of the aircraft production program, no large air reinforcements could be allocated to Western New Guinea, and material defects, lack of proper maintenance, and other causes rendered unserviceable a large proportion of those few aircraft which were sent out from the Homeland.

The extension of the radius of Allied air control, coupled with the increasingly bold incursions by enemy submarines into heretofore Japanese-controlled waters, so augmented the menace to Japanese sea transportation that it appeared seriously questionable whether any fresh troops could be moved into the threatened sectors of Western New Guinea. General Anami faced the discouraging prospect, therefore, of defending that portion of the national defense zone with little more than his current strength.

Imperial General Headquarters was now called upon to make a difficult decision of

[273]

strategy. In view of the loss of Hollandia and the obvious difficulty of moving adequate reinforcements into Western New Guinea, a minority in the Army General Staff began broaching the idea of pulling back the perimeter of the absolute defense zone in the southern area from Western New Guinea to the Philippines.76 On the other hand, the Army High Command was aware that General Anami, despite the rejection of his proposal for an all-out counterattack to retake Hollandia, remained inclined toward a decisive defense of the forward positions in the Geelvink Bay area.

Imperial General Headquarters was in no way disposed to consider an outright revision of the national defense zone at this stage, but at the same time it decided that General Anami must be restrained from pouring the bulk of the reinforcement divisions into the Geelvink Bay sector instead of using them in the weakly defended Vogelkop-Halmahera zone. With the Navy section's reassurance that the Bay sector would have vital value in future naval operations, the Army Section dispatched a directive to Southern Army headquarters on 2 May, the main points of which were as follows:77

1. The line to be secured in the Western New Guinea area is designated as a line connecting the southern part of Geelvink Bay, Manokwari, Sorong, and Halmahera.

2. Strategic points on and in the vicinity of Biak Island will be held as long as possible.

3. Necessary troops will be withdrawn to Biak from the Sarmi district as quickly as possible.

Before Southern Army dispatched implementing orders to Second Area Army, General Anami had learned of the serious losses suffered by the Take convoy in the 6 May attack. He nevertheless wired both Southern Army and Imperial General Headquarters urging that some of the remaining ships of the convoy, despite the risk, be sent on at least to Sorong, and preferably as far as Manokwari, to complete the movement of the 35th Division. The 32d Division was to be retained for the defense of Halmahera.

Because of the grave risk entailed in sending major fleet units into waters dominated by Allied air power, General Anami's request was flatly rejected by Imperial General Headquarters. Moreover, the serious reduction of 32d and 35th Division strength led the High Command to modify the order of 2 May in favor of a further contraction of the projected main line of resistance. An Imperial General Headquarters directive to Southern Army on 9 May stated as follows:78

1. The line to be secured in the Western New Guinea area will be a line extending from Sorong to Halmahera.

2. The area covering the lower part of Geelvink Bay, Biak; and Manokwari will be held as long as possible.

Southern Army on 11 May dispatched implementing orders to the Second Area Army, directing that the 35th Division be stationed in the Sorong area.

There was now a serious and fundamental conflict of opinion between Imperial General Headquarters and General Anami with respect to defense strategy for Western New Guinea. On the one hand, the 9 May directive discarded the idea of a decisive defense of the Geelvink Bay positions, envisaging their use only to delay the enemy advance as long as possible. On the other hand, General Anami continued to hold that the forward line, including Biak, must be aggressively and determinedly defended even if adequate reinforcements were unavailable.79

[274]

Apart from the strategic consideration that Sorong would be difficult to defend if attacked, and might even be by-passed entirely once the Geelvink Bay area was in enemy hands, General Anami was influenced by other factors. First, the transfer of 36th Division troops from the Sarmi sector to Biak would be difficult in view of the lack of shipping and enemy air control over the area. Second, orders to fight delaying actions on the forward positions rather than defend them to the last would be meaningless and detrimental to morale, since the possibilities of safe evacuation would be slight. Third, General Anami had discovered that in the Combined Fleet's plan, the waters between Palau and Western New Guinea was considered to be a probable theater for a decisive naval battle, and thus he felt that a premature relinquishment of the Geelvink Bay area, giving the enemy valuable land air bases close to the theater of action, would seriously harm the Navy's chances.80

General Anami consequently decided to take advantage of what leeway was left him by Imperial General Headquarters and Southern Army directives to continue to throw the bulk of his strength into the defense of the key forward positions. Since Imperial General Headquarters had strongly vetoed the dispatch of merchant shipping into the Western New Guinea area, General Anami now opened negotiations with the Fourth Southern Expeditionary Fleet at Ambon to effect the transport to Western New Guinea by warships of the 35th Division troops stranded on Halmahera and Palau. The plan for the deployment of these units upon their arrival was now modified as follows:81

1. 35th Division Hq. and Special Troops-Manokwari

2. one regiment (less one bn)-Biak

3. one regiment (less one bn)-Sorong82

4. one regiment (less one bn)-Manokwari area

On 14 May General Anami proceeded to Second Army headquarters at Manokwari and personally informed the Army commander, Lt. Gen. Teshima, of these developments, instructing him to hold the Geelvink Bay area at all costs and to continue to secure the Sarmi area as a lifeline held out toward the Eighteenth Army forces cut off to the east of Hollandia. At the same time, General Anami dispatched messages to both the Combined Fleet and the Southwest Area Fleet outlining his intentions, substantially as follows:83

The fact that the Navy is preparing to wage a decisive battle in the waters near Geelvink Bay in the near future is a source of gratification to the Second Area Army. Although at this time changes in the main line of resistance have been ordered by higher authority, the Area Army is resolved to hold the Geelvink region at all costs. It is thus ready to give all possible assistance to the naval air forces in this area and to cooperate fully in the decisive naval battle. Moreover, the Area Army has expressed its opinion to higher authorities that the Army air forces should assemble as much strength as possible to cooperate with the Navy at the time of the decisive battle.

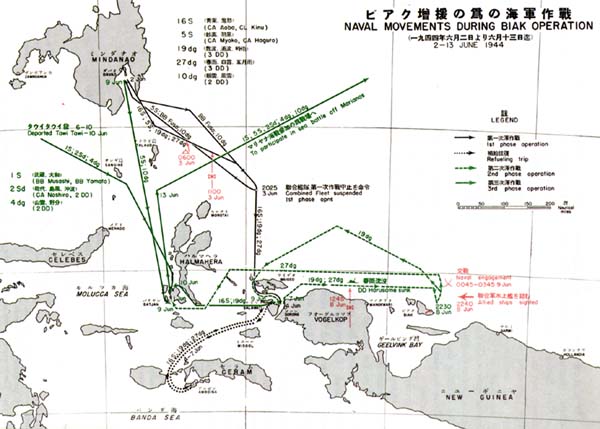

By this time the Navy's preparations for a showdown battle were well under way. On 3 May, Admiral Soemu Toyoda formally assumed command of the Combined Fleet in succession to Admiral Koga, and on the same day an Imperial General Headquarters Navy Directive to the Combined Fleet ordered plans to be laid for the so-called A-Go Operation. The

[275]

essentials of this directive were:84

1. The Commander-in-Chief, Combined Fleet, will swiftly prepare the naval strength required for decisive battle and, during or after the latter part of May, will apprehend and crush the main strength of the enemy fleet in the waters extending from the Central Pacific to the Philippines and Western New Guinea.

2. Decisive battle will be avoided, except under specified circumstances, until the required strength has been prepared.

3. This battle shall be designated Ago Operation.

Under the plans elaborated by the Combined Fleet, the First Mobile Fleet,85 and the First Air Fleet were assigned the principal roles in the projected battle. The former assembled its surface strength at Tawitawi in the Sulu Archipelago on 16 May, while the land-based units of the First Air Fleet continued to be widely deployed in the Marianas and Carolines to take advantage of any tactical opportunity that might arise. Tawitawi was chosen as the main staging point for the First Mobile Fleet because of its proximity to both the refueling facilities of Balikpapan and the sea area which the Navy High Command expected to be the scene of the decisive battle. It was also safely beyond the range of enemy land-based air power and afforded greater security against Allied intelligence than other anchorages in the Philippines.

In the midst of these preparations, however, the Western New Guinea front flared into action again as General MacArthur's forces, less than a month after the invasion of Hollandia, launched a new amphibious assault against the Wakde-Sarmi area guarding the coastal approach to the vital Geelvink Bay region.

With the enemy in firm possession of Hollandia, it was fully apparent that the Allied assault on the heart of Japan's Western New Guinea defenses in the Geelvink Bay area would not long be delayed. Second Area Army estimated that Biak would be the next major objective of General MacArthur's forces, but defense preparations were also hastened in the Wakde-Sarmi coastal sector to meet the possibility that the enemy might first attempt to seize Japanese air bases there to facilitate fighter support of subsequent operations against Biak or Manokwari.86

Under Second Area Army's original plans formulated late in 1943, the Wakde-Sarmi sector, roughly 145 miles west of Hollandia, was to be the forward bastion of the defenses of Geelvink Bay. Engineer and construction units, assisted by combat troops of the 36th Division, had been intensively engaged in building airfields, roads, bridges, and various base installations in the area since January 1944.87 Highest priority was given to airfield construction. By the time of the Hollandia invasion, one of four projected airfields had been completed near Sawar, seven miles below Sarmi, and another was under construction at nearby Maffin Bay.88

The Wakde Islands, lying two and a half miles off the coast about ten miles east of Maffin Bay, were at the eastern extremity of the sector.

[276]

Small, flat and coral-fringed, the islands were not suited for defense against amphibious assault, but on the main island of Insoemoear was an airstrip just under 5,000 feet in length, maintained and used by the Navy but which the Fourth Air Army used both as an operational base and as a dispersal and relay field.89

Japanese troop strength in the WakdeSarmi area at the end of April totalled approximately 14,000.90 The 36th Division under Lt. Gen. Hachiro Tanoue, less the 222d Infantry Regiment already stationed on Biak, was the principal combat force, supplemented by various construction units, airfield and antiaircraft personnel, and supply elements.91 These forces were concentrated mainly between Maffin Bay and Sarmi, with only the 9th Company of the 224th Infantry Regiment, a mountain artillery platoon, some antiaircraft and airfield units, and the 91st Naval Garrison Unit stationed on Insoemoear Island guarding Wakde airfield.92

Prior to the Allied invasion of Hollandia, the development of adequate ground defenses in the Wakde-Sarmi area had been seriously hampered by the funnelling of the main effort of the local forces, including combat troops, into the long-range airfield construction program. The enemy's sudden penetration to within a little more than 100 miles of Wakde led Lt. Gen. Tanoue to order an immediate shift of emphasis to the organization of defenses against amphibious attack. Time was already short, however, and Second Area Army's order directing the dispatch of the 224th Infantry Regiment (Matsuyama Detachment) toward Hollandia seriously curtailed the number of combat troops immediately available.

With only the 223d Infantry, remaining elements of the 224th and miscellaneous supporting troops at his disposal, Lt. Gen. Tanoue decided to center his defensive dispositions in the Maffin Bay-Sawar sector, leaving

[277]

the coastal stretch east of the Tor River and opposite Wakde unguarded. (Plate No. 69) A 36th Division order issued on 8 May set forth the essentials of the operational plan substantially as follows:93

1. The division will assume new dispositions and prepare to destroy the enemy at close range.

2. The Right Sector Unit will consist of the 26th Airfield Survey and Construction Unit, with the remaining elements and part of the artillery of the 224th Infantry Regiment attached. Main strength of the unit will secure the Mt. Irier and Mt. Sakusin sectors, and an element will secure the Toem area.

3. The Central Sector Unit will consist of the 223d Infantry (less 2d Battalion), with the Division Tank Unit (less one platoon) and the road Airfield Survey and Construction Unit attached. It will secure the area from the Mt. Saksin-Mt. Irier line to the Sawar River.

4. The Left Sector Unit will be composed of the 2d Battalion, 223d Infantry, with one tank platoon attached. It will secure the area from the Sawar River to Sarmi, including the Mt. Hakko position.

5. Above units will hold as many mobile reserves as possible. Enemy landing forces will be smashed at the beach.

6. The 4th Engineer Group Commander will supervise the construction of fortifications in the various sectors.

7. The Division command post is at Mt. Hakko but will later move to Mt. Saksin.

While these dispositions were hastily being put into effect, enemy air attacks on the Sawar and Wakde airfields, begun soon after the fall of Hollandia, increased in frequency and intensity. Since the meager remaining combat strength of the Japanese air forces in the Western New Guinea area had already retired to rear bases less vulnerable to attack, these raids appeared to be only a precautionary measure to ensure that the fields could not be used. The enemy bombing offensive reached maximum violence in the middle of May, with apparent emphasis on the coastline of Maffin Bay. At the same time, frequent appearances by Allied destroyers and motor torpedo boats in the coastal waters near Sarmi gave further indication that an early landing might be attempted.94 On 16 May Lt. Gen. Tanoue communicated the following estimate of the situation to his subordinate commanders:95

On the basis of the daily increasing severity of enemy air attacks, the constant activity of warships off the coast....and the relative situation of our and the enemy's forces, it appears highly probable that landings are being planned near Wakde Island and Sarmi Point.

This estimate proved true sooner than anticipated. At 0400 on 17 May, an enemy task force of heavy surface units began a fierce three-hour bombardment of Insoemoear Island, interspersed with heavy air strikes, and at 0700 Allied troops began landing operations on the mainland opposite Insoemoear, in the sector between Toem and Arara. The main Japanese forces, concentrated as they were to the west of the Tor River, were unable to offer any opposition to the landing.96 By the evening of 17 May, the Allied forces had established a firm

[278]

PLATE NO. 69

Sarmi-Wakde Operation, May-July 1944

[279]

beachhead between the Tementoe and Tor Rivers.

At 2200 the same day, Lt. Gen. Tanoue ordered his forces to prepare for an attack to wipe out the enemy beachhead, simultaneously ordering the Matsuyama Detachment, then to the east of Masi Masi on its way toward Hollandia, to return to the Toem area as quickly as possible and attack the enemy from the east.97 As these preparations were getting under way, the enemy on 18 May moved strong amphibious forces across to Insoemoear Island and wiped out the small Wakde garrison in brief but sharp fighting.98 With the capture of Wakde airfield, the enemy achieved what seemed to be his main strategic objective.

Although not certain as to the exact situation east of the Tor River, Lt. Gen. Tanoue rushed his attack preparations and, on the night of 18 May, ordered the Right Sector Unit to cross the river and begin a preliminary attack.99 The following day an order was received from the Second Army Commander directing an all-out attack on the enemy in the Toem sector. Accordingly, Lt. Gen. Tanoue at 1,000 on 19 May issued a new order, the essential points of which were as follows:100

1. It is estimated that the strength of the enemy forces, which landed in the vicinity of Toem, is about two infantry regiments and about 100 tanks and armored cars.

2. The Matsuyama Detachment is returning and will attack the enemy. The Right Sector Unit is also preparing to attack.

3. The division main strength will annihilate the enemy in the vicinity of the Tor River.

4. The Central Sector Unit will cross the Tor River by dawn of 22 May and prepare to attack Toem. Special assault and incendiary units will be organized. The main strength of the artillery will remain in their present positions on the coast.

5. The division command post will move to Mt. Saksin before dawn on 22 May.

Execution of the attack plan, however, necessitated moving the main strength of Lt. Gen. Tanoue's forces across the wide and unbridged Tor River. Since movement along the coastal road and a crossing near the river mouth would be exposed to enemy naval gunfire, the 36th Division commander decided to move his units inland through jungle and mountainous terrain to cross the Tor at its confluence with the Foein River, and then swing back toward the enemy beachhead. In preparation for this operation, Lt. Gen. Tanoue on 20 May ordered the 36th Division bridging unit to move landing craft and collapsible boats via the Foein River to the proposed crossing-point on the Tor.101

While the Central Sector Unit (223d Infantry) was beginning its difficult march to attack positions east of the Tor, the Right Sector Unit commenced operations in the Maffin sector on 19 May. A reconnaissance to the east of Maffin village on that date revealed that the enemy had already crossed the Tor River near its mouth and established a small bridgehead. By 21 May, this Allied element

[280]

had pushed to a point about one mile east of Maffin, stoutly resisted by rear echelon troops of the 224th Infantry, which had been organized into a provisional battalion. By 24 May, the enemy occupied Maffin village and continued to advance westward, threatening the Mt. Irier-Mt. Saksin positions occupied by the main strength of the Right Sector Unit. The Allied force, however, halted at the east bank of the Maffin River and did not launch an immediate assault on the hill positions. Lt. Gen. Tanoue took advantage of this momentary lull to order the Left Sector Unit (2d Battalion, 223d Infantry) to move immediately to the Mt. Irier line and bolster the rapidly weakening Right Sector Unit. Pending arrival of these reinforcements on 29 May, the Right Sector Unit hastily organized defenses in depth on the high ground west of Maffin.102

While the Right Sector Unit was heavily engaged in the Maffin area, the 223d Infantry, delayed in its overland march to the assigned crossing point on the Tor and handicapped by the slowness with which the assault boats were brought forward, finally crossed the Tor on 25 May, three days behind schedule. Meanwhile, the Matsuyama Detachment completed its forced march back from the east, closed up to the right bank of the Tementoe River, and prepared to attack the enemy's left flank at Toem.

On the night of 27 May, the Matsuyama Detachment crossed the Tementoe River and launched a surprise attack on Toem. This operation met with limited success. A part of the detachment penetrated as far as the beach, forcing a number of the enemy to flee offshore in landing boats. The enemy's artillery and naval gunfire reaction to this attack was extremely violent. Heavy casualties were sustained, and before dawn on 28 May, Col. Matsuyama, fearing that the narrow salient might be pinched off, withdrew the advance elements and allowed his exhausted troops a breathing spell.103

Meanwhile, the 223d Infantry, having completed its arduous trek from the Sawar area, began assembling in the jungle about two miles south of Arara on the night of 27 May and prepared to attack. Completion of the assembly and attack preparations consumed three days, and it was the night of 30 May before the regiment was ready to strike in force. The attack penetrated the outer part of the enemy perimeter, but again the Japanese lacked the means to exploit the initial success. The regiment withdrew before dawn on 1 May but kept up nightly raiding attacks thereafter.104

While the 223d and 224th Infantry continued their pressure on the enemy's ToemArara beachhead, the situation in the Maffin area improved.105 The Right Sector Unit commander, having been reinforced by the 2d Battalion, 223d Infantry, on 29 May, decided to recapture Maffin village. This attack was carried out on the night of 31 May but did not succeed. On the night of 2 June, however, the effort was renewed, and Maffin was reoccupied. The Japanese continued the attack eastward against increasing enemy resistance but did not succeed in wiping out the Allied bridgehead across the mouth of the Tor.

[281]

The initiative seized by the Right Sector Unit was shortlived. On 6 June, the enemy struck back at the Japanese positions about one-half mile east of Maffin village. This attack continued on 7 June and was so powerful that the exhausted Right Sector Unit was finally obliged to conduct a delaying action back through Maffin and thence southward to draw the enemy away from Mt. Irier.106

The situation of the 36th Division was now extremely precarious. To the east of the Tor was the main body of the division at the end of a long supply line which wound circuitously through the dense jungle interior. Without naval or air support any further efforts on the part of the 223d and 224th Infantry Regiments to reduce the enemy beachhead seemed foredoomed to failure. To the west of the Tor, all that stood between the enemy and the Sawar airfield-Sarmi village area was a handful of exhausted troops entrenched on Mt. Irier and Mt. Sento. This situation led Lt. Gen. Tanoue, on 8 June, to order the Matsuyama Detachment to withdraw immediately west of the river. On 10 June a similar order was transmitted to the 223d Infantry. It was hoped that the two regiments would arrive in the Mt. Irier-Mt. Sento area in time to meet the enemy assault on that critical position.107

The withdrawal of the division main body was a difficult and protracted operation. However, the stubborn resistance of the Right Sector Unit near Maffin delayed the enemy's approach to the Mt. Irier-Mt. Sento positions until mid-June, and the main strength of Lt. Gen. Tanoue's forces had by that time completed its withdrawal west of the Tor. The division commander now deployed the 1st Battalion, 224th Infantry, on Mt. Irier, the 224th Infantry (less 1st Battalion) on Mt. Sento, and the 223d Infantry in the sector west of Mt. Saksin as a mobile reserve.108

Following a small-scale attack on Mt. Sento on 17 June, the enemy on the 23d began a series of attacks on Mt. Irier. The battle raged for two days, during which the heights changed hands three times. However, relentless enemy pressure backed by intense air and artillery bombardment finally carried the position. Meanwhile, a new enemy landing to the west of the Woske River mouth on 24 June menaced the Japanese rear. Lt. Gen. Tanoue promptly ordered the 224th Infantry to fall back to the Mt. Sento-Mt. Saksin line, and the 223d Infantry to withdraw west of the Woske to meet the threat to Sawar airfield.109 Actually, the enemy never attempted to seize either Sawar airfield or Sarmi village. His main objectives appeared to have been won, and the presence in the area of the exhausted remnants of the 36th Division had no important effect on the subsequent strategic situation.

Fighting in the Wakde-Sarmi sector after 27 May had been overshadowed by a far more crucial battle farther west. Having gained control of Wakde airfield for use as a forward base, the enemy, without waiting to complete the defeat of Lt. Gen. Tanoue's forces, had already launched an assault on Biak Island, the keystone of the Japanese defenses in Western New Guinea.

[282]

The swift Allied advance to Wakde left no doubt that the enemy was rapidly preparing for the final phase of his campaign to win control of all New Guinea and force the Japanese back upon the Philippines. Because of its vital strategic importance as a base from which to extend the radius of Allied air domination, Biak Island- less than 600 miles from Halmahera and Palau, and barely 900 miles from Davao, on Mindanao Island-was considered certain to be a major objective of this final drive.

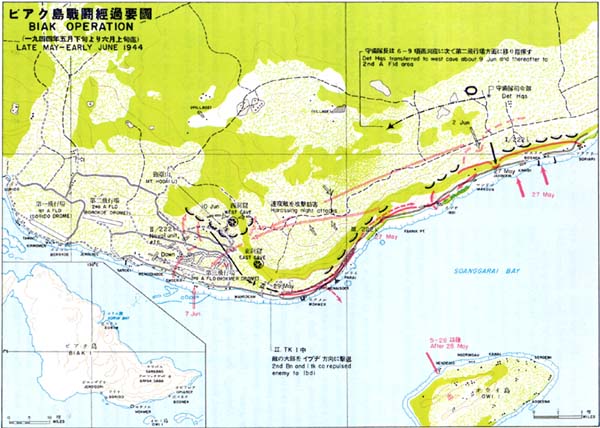

Second Area Army, when it first formulated its plans to develop the Geelvink Bay area into the main line of resistance in Western New Guinea, decided to make Biak the key strongpoint of the line. As elsewhere along the absolute defense zone perimeter, primary emphasis was laid upon the construction of airfields. Between December 1943 and the enemy invasion of Hollandia in April 1944, two of three projected fields on southern Biak were completed and put into operational use by planes of the Navy's 23d Air Flotilla.110 Their usefulness ended almost immediately, however, when the enemy's vastly superior air forces began operating from Hollandia bases.

As in the Wakde-Sarmi sector, the concentration of effort on airfield construction until the Hollandia invasion resulted in dangerously delaying the preparation of ground defenses against enemy amphibious attack. In the five weeks which elapsed between the Hollandia and Biak invasions, the Biak garrison forces, under able leadership and by dint of desperate effort, succeeded in organizing a system of strong cave positions, which proved highly effective after the enemy landing.111 However, time, equipment and manpower were so short that defensive preparations could not entirely be completed. Some 15-cm naval guns, brought to Biak immediately after the Hollandia invasion to strengthen the coast defenses, were still unmounted when the island was attacked.112

The Allied blow also fell before Second Area Army had been able to execute its plan to reinforce the Biak garrison with elements of the 35th Division.113 The 222d Infantry, 36th

[283]

Division, under command of Col. Naoyuki Kuzume, continued to constitute the combat nucleus of the garrison, the remainder of which consisted of rear echelon, service, and construction units. In addition to the Army troops, 2,000 naval personnel were on the island, bringing the aggregate strength of the forces on Biak to approximately 12,000.114

Five days after the enemy landings at Hollandia, Col. Kuzume took initial action to organize and dispose his forces to meet a possible amphibious attack. These dispositions were laid down in an operations order issued on 27 April, the essentials of which were as follows:115

1. The Biak Detachment will destroy at the water's edge any enemy force attacking this island. The detachment main strength will be disposed along the south coast immediately.

2. Rear area forces will be converted into combat units. The detachment will assume command of Navy ground troops.

3. Coastal sectors of responsibility are designated as follows:

19th Naval Garrison Unit-Bosnek to Opiaref

1st Bn, 222d Infantry-sector east of Opiaref

2d Bn, 222d Infantry-Sorido to Bosnek

3d Bn, 222d Infantry--detachment reserve

Tank Company-take position at Arfak Saba and prepare to move against enemy landing.4. Detachment headquarters will be 2 1/2 miles north of Jadiboeri.

On the heels of this order, the Allied air forces on 28 April carried out a heavy raid on the Sorido airfield sector, marking the beginning of a month-long air assault which constantly hampered the progress of defensive preparations.116 From 17 May, when the Allied landing in the Wakde area took place, the bombings increased sharply in violence and assumed the characteristics of pre-invasion softening-up operations.

In view of the intense enemy concentration on the Sorido-Mokmer airfield sector, Col. Kuzume decided on 22 May to shift the operational center of gravity of the detachment to the west. The 1st Battalion, 222d Infantry, was relieved of its mission in the sector east of Opiaref and sent to replace the naval garrison unit in the Bosnek sector. The naval troops were, in turn, shifted westward into the Sorido

[284]

airfield sector, while the tank company was brought over from Arfak Saba and assembled in the area northwest of Mokmer airfield.117