CHAPTER XI

PHILIPPINE DEFENSE PLANS

Strategic Situation, July 1944

So ominous for Japan's future war prospects were the defeats inflicted by Allied arms in the Marianas and Western New Guinea in the early summer of 1944 that, in mid-July, they culminated in the second shake-up of the Army and Navy High Commands in five months, and the first major political crisis since the Tojo Government had taken the nation into war.1

On 17 July Admiral Shigetaro Shimada resigned as Navy Minister in the Tojo Cabinet, and a day later, simultaneously with the public announcement of the fall of Saipan, General Tojo tendered the resignation of the entire Cabinet, yielding not only his political offices as Premier and War Minister, but also stepping down as Chief of Army General Staff. General Kuniaki Koiso (ret.), then Governor-General of Korea, formed a new Cabinet on 22 July with Field Marshal Sugiyama as War Minister and Admiral Mitsumasa Yonai as Navy Minister. General Yoshijiro Umezu was named Chief of Army General Staff.2 The shakeup was not finally completed until 2 August when Admiral Shimada also yielded his post as Chief of Navy General Staff to be replaced by Admiral Koshiro Oikawa

While these changes in Japan's top-level war command were still hanging fire, the planning staffs of the Army and Navy Sections of Imperial General Headquarters were already giving urgent attention to the revision of future war strategy in the light of the new situation created by the parallel Allied thrusts into Western New Guinea and the Marianas. Strategically, as well as in virtually every other respect, the situation was darker than at any time since the outbreak of the Pacific War.

The "absolute" defense zone defined by Imperial General Headquarters in September 1943 had in fact been penetrated at two vital points. In the south, General MacArthur's forces, within six months of their breakthrough via the Vitiaz and Dampier Straits, had pushed one arm of the Allied offensive more than one thousand miles along the north coast of New Guinea, coldly by-passing and isolating huge numbers of Japanese troops along the axis of advance. The capture of Hollandia gave the enemy a major staging area for further offensive moves, and his land-based air forces, with forward bases on Biak and Noemfoor, were in a position to extend their domination over the Moluccas, Palau, and the sea approaches to the southern Philippines.

In the Central Pacific, the northern prong of the Allied offensive had by-passed the Japanese naval bastion at Truk to penetrate the planned defense perimeter at a second vital

[304]

point in the Marianas, only 1,500 miles from the home islands themselves. The seizure of Saipan not only placed the Volcano and Bonin Islands within easy range of Allied tactical bomber aircraft, but threatened Japan itself with intensified raids by the new B-29, already operating from western China. More serious still, the crippling losses suffered by the Navy in the Philippine Sea Battle, especially in air strength, gave the enemy unquestioned fleet and air supremacy in the Western Pacific.

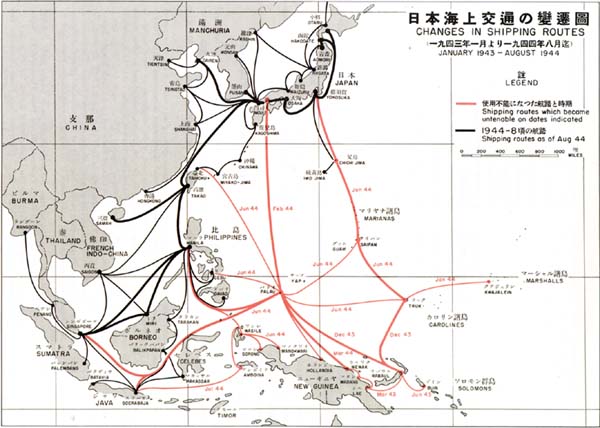

Because of the vast expansion of the areas menaced by Allied sea and air activity, it was necessary to abandon all projects for the dispatch of major reinforcements to segments of the outer defense line which still remained intact, notably Palau and Halmahera. Japanese lines of communication with the southern area were pushed back into the inner waters of the South and East China Seas, and even these relatively protected, interior routes were now subject to increased danger since the acquisition of new bases in the Marianas enabled enemy submarines to step up and prolong their operations against convoys moving along the inner shipping lanes. (Plate No. 75)

Transport losses due to enemy undersea attacks, particularly in the waters adjacent to the Philippines, had already assumed grave proportions before the loss of the Marianas.3 Vital military and raw materials traffic between Japan and the southern area was seriously affected, and by the summer of 1944 fuel reserves in the homeland had dwindled to a critically low point, while southbound troops and materiel began to pile up at Manila, the central distribution point for the entire southern area, for lack of transport. Personnel replacement depots in the Manila area were so overcrowded that local food supplies ran short and the troops had to be placed on reduced rations.4

The shortage of fuel reserves in Japan Proper had a hampering effect on the operational mobility of Japan's remaining fleet strength. Soon after returning to home bases from the Philippine Sea Battle, the First Mobile Fleet was obliged to split its forces, dispatching most of its surface strength to Lingga anchorage, in the Dutch East Indies, where sufficient fuel was available, while the carrier forces remained in home waters to await aircraft and pilot replacements.5

With the main Pacific defense line breached at two points and its remaining segments incapable of being reinforced adequately to ensure

[305]

PLATE NO. 75

Changes in Shipping Routes, January 1943-August 1944

[306]

successful resistance to Allied assault, it was obvious that Japan must now fall back upon its inner defenses extending from the Kuriles and Japan Proper through the Ryukyu Islands, Formosa, and the Philippines to the Dutch East Indies. Plans and preparations must swiftly be completed with a view to the eventual commitment of the maximum ground, sea and air strength which Japan could muster in a decisive battle to halt the enemy advance when it reached this inner line.

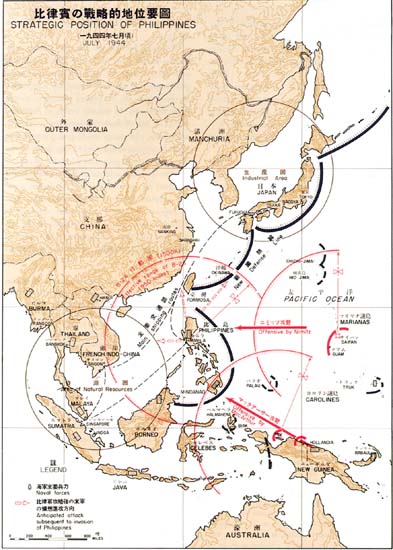

Because of their key strategic position linking Japan with the southern area of natural resources, the Philippines naturally assumed a position of primary importance in the formulation of these plans. Just as their initial conquest had been necessary to guard the Japanese line of advance to the south in 1941-2,6 so was their retention of paramount importance to the defense of the Empire in 1944.

Were the Philippines lost, the already contracted supply lines over which flowed the fuel and other resources essential to continued prosecution of the war would be completely severed, and all of Japan's southern armies from Burma to the islands north of Australia would be cut off from the homeland. At the same time, the enemy would gain possession of a vital steppingstone toward the heart of the Empire and a staging area adequate to accommodate the vast build-up of forces and materiel required for mounting the final assault upon the Japanese home islands.7 (Plate No. 76)

Imperial General Headquarters estimates of Allied offensive plans also underlined the importance of the Philippines. As early as March 1944, a careful study of the enemy's

[307]

PLATE NO. 76

Strategic Position of Philippines, July 1944

[308]

probable future strategy arrived at the conclusion that there was only slight possibility of a direct advance upon Japan from the Central Pacific, primarily because the absence of land bases within fighter range of the main islands would make effective air support of an invasion via that route extremely difficult. Instead, it was considered most probable that the enemy offensives from New Guinea and the Central Pacific would first converge upon the Philippines in order to sever Japan's southern line of communications, and that, with these islands as a major base, the advance would then be pushed northward toward Japan via the Ryukyu Island chain.8 Land-based air power would be able to support each successive stage of this advance.

The enemy thrust into the Marianas in June caused Imperial General Headquarters to reexamine the possibilities of a direct advance upon the homeland from that direction, but while a capability was accepted, the High Command did not diverge from its previous estimate that the enemy's most probable course would be to undertake reconquest of the Philippines as a prior requisite to the invasion of Japan Proper.9

On the basis of these estimates, Imperial General Headquarters decided that top priority in preparations for decisive battle along the inner defense line must be assigned to the Philippines. It was anticipated that the enemy would launch preliminary moves against Palau and Halmahera about the middle of September in order to secure advance supporting air bases, and that the major assault on the Philippines would come sometime after the middle of November.10

With the short space of only four months remaining before the anticipated invasion deadline, all Japan's energies now had to be concentrated on the task of transforming the Philippines into a powerful defense bastion capable of turning back and destroying the Allied forces.

For almost a year and a half following the completion of the Japanese occupation of the Philippines in June 1942, little attention had been given either by Imperial General Headquarters or by the occupying forces to preparations against an ultimate Allied reinvasion. Japan's full war energies were thrown into the outer perimeter of advance to meet steadily intensifying Allied counterpressure, and the development of a strategic inner defense system went neglected until the establishment in September 1943 of the "absolute defense zone" embracing areas west of Marianas-Carolines-Western New Guinea line.

Under the plans worked out for this zone, as outlined earlier,11 the Philippines were to play the role of a rear base of operations, i. e., an assembly and staging area for troops and supplies and a concentration area for air reserves, to support operations at any threatened

[309]

point on the main defense perimeter from the Marianas south to Western New Guinea and the Banda Sea area. To implement these plans, Imperial General Headquarters in October directed the Fourteenth Army12 to complete the establishment of the necessary base facilities by the spring of 1944.

Major emphasis in this program was laid upon the construction of air bases. The Army alone planned to build or improve 30 fields in addition to 13 already in operational use or partially completed.13 The Navy projected 21 fields and seaplane bases to be ready for operational use by the end of 1944, expanding its total number of Philippine bases to 33.14 Line of communications and other reararea base installations were also to be expanded and improved.

To speed up the execution of the program, Imperial General Headquarters dispatched additional personnel to the Philippines in November, and ordered the reorganization and expansion of the 10th, 11th, and 17th Independent Garrison Units, currently stationed on Mindanao, the Visayas, and northern Luzon respectively, into the 30th, 31st, and 32d Independent Mixed Brigades, with a strength of six infantry battalions each, plus normal supporting elements. In addition, the 33d Independent Mixed Brigade was newly activated at Fort Stotsenberg, Luzon, by combining various garrison units.15

In the political sphere, Japan sought to win increased Filipino cooperation in October by setting up an independent government under the presidency of Jose P. Laurel. A treaty of alliance concluded simultaneously with the inauguration of the new government provided for close political, economic and military cooperation "for the successful prosecution of the Greater East Asia War" and was supplemented by attached "Terms of Understanding" which stipulated:16

The principal modality of the close military cooperation for the successful prosecution of the Greater East Asia War shall be that the Philippines will afford all kinds of facilities for the military actions to be undertaken by Japan, and that both Japan and the Philippines will closely cooperate with each other in order to safeguard the territorial integrity and independence of the Philippines.

In accordance with these provisions, the Laurel Government promulgated orders to ensure cooperation with local Japanese military commanders, and steps were taken through local administrative agencies to recruit Filipino labor for use in carrying out the airfield construction program and the improvement of defense installations. As General MacArthur's forces steadily forged ahead toward the Philippines in the spring of 1944, however, cooperation with the Japanese armed forces gradually broke down, giving way to sabotage and active hostility.17

Anti-Japanese feeling and discontent were heightened by food shortages. Prior to the

[310]

war a substantial volume of food products had been imported, but as the intensification of enemy submarine warfare cut down shipping traffic, these imports almost ceased. Commodity prices soared to inflation levels, and Filipino farmers refused to deliver their prescribed food quotas to government purchasing agencies. Allied short-wave propaganda broadcasts effectively played upon this unrest by emphasizing Allied economic and military superiority and the certainty of Filipino liberation.

The local situation was deteriorating so rapidly that a report drawn up by Imperial General Headquarters at the end of March 1944 summarized conditions in the following pessimistic terms:18

Even after their independence, there remains among all classes in the Philippines a strong undercurrent of pro-American sentiment. It is something steadfast, which cannot be destroyed. In addition, the lack of commodities, particularly foodstuffs, and rising prices are gradually increasing the uneasiness of the general public. The increased and elaborate propaganda disseminated by the enemy is causing a yearning for the old life of freedom. Cooperation with and confidence in Japan are becoming extremely passive, and guerrilla activities are gradually increasing.

It was these guerrilla activities, which the small Japanese occupation forces had never been able to stamp out, that posed the most serious potential threat to military operations. In the spring of 1944 the total strength of the organized guerrillas was estimated at about 30,000, operating in ten "battle sectors".19 Allied submarines and aircraft operating from Australia and New Guinea brought in signal equipment, weapons, explosives, propaganda leaflets and counterfeit currency for the use of the guerrilla forces,20 and liaison and intelligence agents arrived and departed by the same means.

Particularly dangerous to the Japanese forces was the gathering and transmission by the guerrillas of intelligence data to the Allies. A network of more than 50 radio stations, at least five of which were powerful enough to transmit to Australia and the United States, kept feeding out a constant flow of valuable military information: identifications and locations of Japanese units, troop movements, locations and condition of airfields, status of new defense construction, arrival and departure of

[311]

aircraft, ship movements and defense plans.21

Intelligence agents operated boldly in virtually every part of the Philippines, but the greatest activity appeared to be concentrated in the area around the Visayan Sea and on Mindanao, a fact which suggested the probability of an eventual Allied landing in that area.22 Japanese local units repeatedly undertook campaigns to eliminate the guerrillas and silence their radio stations but as soon as the troops withdrew after a clean-up expedition, guerrilla activity would spring up anew.

Until the summer of 1944, direct military action by the guerrillas was generally limited to sporadic hit-and-run attacks on small Japanese units in out-of-the-way areas and on supply columns.23 Such harassing tactics did not affect the overall dispositions of the Japanese forces, but they required that small garrisons keep constantly on the alert. Moreover, as enemy invasion became a more and more imminent probability, the activities of the guerrillas grew bolder and more flagrant, aided by the fact that the Japanese forces were increasingly preoccupied with defensive preparations and were obliged to concentrate troop strength in anticipated areas of attack.

Between October 1943 and March 1944, military preparations in the Philippines remained confined to the development of the islands as a rear operational base for support of decisive battle operations along the Marianas-Carolines-Western New Guinea line. No plans were yet considered for fortifying the Philippines themselves against enemy invasion, partially because Japan's resources were already heavily taxed in order to complete preparations along the main forward line, and partially because of belief that the Allied advance could be stopped at this forward barrier.

In March, however, the first indications of a change in strategic thinking with regard to the Philippines appeared. On 27 March Imperial General Headquarters, Army Section ordered a revision of the command set-up for the southern area, expanding Southern Army's operational control to take in the Fourteenth Army in the Philippines, the Second Area Army in Western New Guinea and the eastern Dutch East Indies, and Fourth Air Army. These new dispositions were to become effective 51 April.* 24 The same order directed Fourteenth Army to institute defense preparations, particularly on Mindanao, and on 4 April Imperial General Headquarters transferred the 32d Division to Fourteenth Army for the purpose of reinforcing the southern Philippines.25

Consequent upon the revision of command, Southern Army drew up new operational plans

*Note: This is an error in the original text and it is uncertain what date was intended.

[312]

PLATE NO. 77

Unloading Operations, Philippine Area

[313]

covering its expanded zone of responsibility and specifying the missions of subordinate forces. An essential feature of these plans was the emphasis placed upon strengthening the Philippines, not merely as a rear supporting base, but as a bastion against eventual direct invasion by the enemy. The main points were as follows:26

1. Southern Army's main line of defense will be the line connecting Burma, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Sumatra, Java, the Sunda Islands, the north coast of New Guinea west of Sarmi, Halmahera and the Philippines. The Philippines, Halmahera, Western New Guinea, Bengal Bay and the Burma sectors of this line are designated as "principal areas of decisive battle." The Philippines shall be the "area of general decisive battle.27

2. The forces defending the sectors designated as "principal areas of decisive battle" (Fourteenth Army, Second Area Army, Seventh Area Army, Burma Area Army) will, in cooperation with the Navy, strengthen combat preparations and annihilate the enemy if and when he attacks on those fronts. The forces holding other sectors of the Army's main defense line will secure key points and repulse enemy attacks.

3. Ground and air forces in the Philippines will be reinforced, and in the event that the enemy offensive reaches this area, Southern Army will mass all its available ground and air strength there for the general decisive battle.

4. The Fourth Air Army will be responsible for operations in the Philippines and eastern Dutch East Indies (including Western New Guinea); and the Third Air Army will be responsible for operations to the west of and including Borneo. In the event of enemy attack on the Pacific sector of decisive battle, however, the full strength of both Air Armies will be concentrated on that front and annihilate the enemy.28

Thus, even while preparations were under way for a decisive defense of the MarianasWestern New Guinea line, Imperial General Headquarters, Army Section and Southern Army already had begun to envisage an even greater decisive battle in the Philippines, which would spell the fate of Japan's entire conquered empire in the south. The enemy's startling advance to Hollandia, which occurred while the Southern Army's plans were in the final stage of preparation, served to underline the new emphasis given to the Philippines.

The substance of these plans was communicated to the commanders of the various armies under Southern Army control at a conference specially summoned for that purpose at Singapore on 5 May. In mid-May Field Marshal Hisaichi Terauchi, Southern Army Commanderin-Chief, transferred his headquarters to Manila in order to exercise closer control over operations on the Army's eastern decisive battlefront, and at the same time the 3d Shipping Transport headquarters, which controlled all ocean transportation within the Southern Army area, displaced from Singapore to Manila.29

[314]

Southern Army meanwhile began pressing for action to increase troop and air strength in the Philippines to more adequate levels. At the beginning of May, Fourteenth Army's combat ground forces consisted of only one division (16th) and four independent mixed brigades, with one additional division (30th) already allocated by Imperial General Headquarters late in April and scheduled for early transfer form Korea. As against this meager strength, the operations staff of Southern Army estimated that fifteen field divisions would be required for decisive battle operations in the Philippines, in addition to eight independent mixed brigades for security control and garrison duty.30 A large-scale reinforcement of the Fourth Air Army was also considered vitally necessary.31

Southern Army recognized, however, that the prior demands of reinforcing the Marianas-Western New Guinea line left no immediate possibility of boosting troop strength in the Philippines up to the level of its estimated requirements. No formal representations were therefore made to Tokyo, although the Army's views were informally communicated to Imperial General Headquarters staff officers who visited Singapore and, subsequently, Manila for liaison purposes. The need of allocating sufficient shipping to Southern Army to permit moving troops from other sectors of its own responsible area to the Philippines was also stressed in these conversations.32

The Fourteenth Army Commander, Lt. Gen. Shigenori Kuroda,33 had meanwhile taken initial steps in April to regroup the forces already at his disposal with a view to ultimate defense against invasion. The 16th Division (less the 33d Infantry and other minor elements designated Army reserve) was transferred from Luzon to Leyte and, with the 31st Independent Mixed Brigade attached, was made responsible for the defense of Visayas. The 32d and 33d Independent Mixed Brigades were directed to undertake defense preparations in northern and southern Luzon, respectively. The 30th Division, upon arrival from Korea, was to be assigned to the defense of Mindanao, reinforced by the 30th Independent Mixed Brigade, already in the Mindanao area.34

While the Army was carrying out these preliminary moves to revitalize the defenses of the Philippines, the major elements of the Navy were fully occupied in preparations for the planned decisive battle operations in the Western Pacific.35 The 3d Southern Expeditionary Fleet, which had been responsible since January 1942 for local naval security in Philippine waters, had only small forces and was unable to take more than limited measures to

[315]

strengthen the islands' sea defenses.36

The situation in regard to air strength also remained unsatisfactory pending the execution of plans to reinforce the Fourth Air Army. Of the Air Army's existing components, the 6th Air Division had lost virtually all of its remaining strength at Hollandia, while the 7th Air Division was fully committed in the Ceram area.37 Active operations on the Burma front meanwhile barred any early transfer of Third Air Army strength to the Philippines area.38 Naval air strength was chiefly limited to the 26th Air Flotilla, which had moved back from the Rabaul area to Davao in February for reorganization and training.39

The enemy's unexpectedly early penetration to Hollandia in April brought wider recognition that no time must be lost in strengthening the defenses of the Philippines. The main Western New Guinea defense line under preparation in the Geelvink Bay area was still incomplete and inadequately manned, and serious doubt began to be felt that it would succeed in stopping General MacArthur's accelerated drive toward the Philippines.

To meet this danger, Imperial General Headquarters, Army Section in the middle of May ordered Southern Army to carry out a program of operational preparations in the Philippines, designated as Battle Preparations No. 11.40 The Army High Command recognized that air power would be of key importance in defending so large an island area and therefore assigned first priority in this program to preparations for large-scale air operations. Army ground forces were charged with full responsibility for carrying out the airfield construction program, which was expanded to provide for 30 new fields in addition to those projected in October 1943.41

A sufficient number of additional fields were to be ready for use by the end of July to permit the deployment of four air divisions, and subsequent construction was to proceed rapidly enough to enable two more air divisions to be deployed in the Philippines by the end of 1944. Already established fields, such as those at Manila, Clark, Lipa, Bacolod, Burauen, Del Monte and Davao, were to be maintained as air bases.42

Shortly prior to the issuance of Battle

[316]

Preparations No. 11, Imperial General Headquarters had taken initial steps to reinforce air strength in the Philippines, ordering the transfer of the 2d and 4th Air Divisions from the Second Air Army in Manchuria. The 4th Air Division was directly assigned to the Fourth Air Army, while the 2d was assigned to Southern Army, which subsequently placed it under Fourth Air Army command. Late in May the first increment of these reinforcements arrived in the Philippines, and on 1 June Fourth Air Army headquarters effected its planned transfer from Menado to Manila.43 Before leaving Manchuria, the 2d and 4th Air Divisions were reorganized, most of the flying units being assigned to the 2d44 and base maintenance units to the 4th.45

Under Battle Preparations No. 11, steps were also taken to bolster Fourteenth Army troop strength. During June 15,000/20,000 filler replacements were transported to the Philippines, and Fourteenth Army was ordered to reorganize and increase its four independent mixed brigades to divisions, using these replacements to fill them up to division strength.46 The new divisions and their locations were as follows:

Ind. Mixed Division

| Brig. |

Designation |

Headquarters |

|---|---|---|

| 30th | 100th Division | Davao, Mindanao |

| 31st | 102d Division | Cebu |

| 32d | 103d Division | Baguio, Luzon |

| 33d | 105th Division | Las Baños, Luzon |

In addition to these units, two new independent mixed brigades, the 54th and 55th, were activated on Luzon, the 55th remaining in Central Luzon and the 54th transferring to Zamboanga via Cebu shortly after organization was completed.47 The 58th Independent Mixed Brigade, just organized in Japan Proper, was also assigned by Imperial General Headquarters order to Fourteenth Army as a further step to strengthen the ground forces in the Philippines.48

Despite the shift of a portion of the airfield construction program over to the 4th Air Division, a large part of the Army ground forces still had to be allocated for this purpose instead of to the immediate preparation of ground defenses against invasion. Fourteenth Army, however, was keenly aware of the detrimental consequence which the same course had produced with respect to the tenability of the Western New Guinea defense line, and decided that August must be fixed as the deadline for the switch-over of all ground forces to preparations for ground operations.49

[317]

Efforts were also launched to increase the efficiency of the line of communication system and to accumulate reserves of military supplies. One of the first moves was the formation of the Southern Army Line of Communications Command on 10 June.50 This headquarters took over command of all line of communication units in the Philippines and, in addition, was charged with responsibility for logistical support of the entire Southern Army.

Concurrently with the execution of the Army's Battle Preparations No. 11, the Navy also took steps to reinforce its Philippine defenses, especially in air strength. After suffering heavy losses in June and early July at the hands of enemy carrier forces in the Central Pacific, the 61st Air Flotilla of the land-based First Air Fleet51 was ordered back to Philippine bases and immediately began reorganizing and replenishing its strength with replacements arriving from Japan.52

Meanwhile, on 12 July, Southwest Area Fleet transferred its headquarters from Surabaya to Manila in order to assume closer control of naval base and surface forces in the Philippines.53

The sharp acceleration of defense preparations in the Philippines made it necessary to allocate additional shipping for military use. In August 105,000 tons of general non-military ships were made available to the Army and earmarked for employment in reinforcing the Philippines. At the same time, in order to speed the importation to Japan of oil and critical raw materials from the southern area, the Government in July transferred 200,000 tons of shipping from general freight transport between Japan and China-Manchuria to the southern shipping route, and ordered the conversion of 232,000 gross tons of cargo ships into oil tankers.54

To achieve maximum utilization of shipping space, a central coordinating control body was established in July, composed of representatives of the War, Navy and Transportation Ministries. This body permitted a more flexible system whereby military shipping, which might return to Japan empty after discharging troops or supplies at Manila for example, could be diverted to Singapore or some other southern port to pick up critical cargo for the Homeland. Similarly, nonmilitary freighters hitherto sent out empty to southern ports could be used to carry military traffic as far as Manila.55

Along with these measures, the Navy, after considerable experimentation, achieved a more effective system of convoy protection. The number of escort ships was increased to 80, almost three-fourths of which operated on the

[318]

southern route under the 1st Escort Force headquarters, located at Takao, Formosa.56 Four escort carriers, converted from merchant ships, were also made available for escort duty, and new air groups, with radar-equipped planes, were organized exclusively for patrolling shipping lanes.57 Navy seaplanes were also being equipped with a newly-perfected magnetic device for the detection of submerged submarines.58

Central Planning for Decisive Battle

Initial steps to gird the Philippines against eventual enemy invasion were thus already under way when the penetration of the main Western New Guinea defense line and of the Marianas made it evident that Japan must now prepare to wage an all-out decisive battle in defense of the inner areas of her Empire.

Although the Philippines were expected to be the first of these inner areas to be attacked, Imperial General Headquarters also had to consider the possible contingency that the enemy might strike alternatively at Formosa or the Ryukyu Islands, or possibly even at the Japanese home islands themselves. Comprehensive operational plans therefore had to be worked out to cover all these possibilities.59

The basic strategic principle adopted as the foundation of these plans was that whichever of the inner areas first became the object of invasion operations by the main strength of the enemy would be designated as the "decisive battle theater," and that as soon as this theater was determined, all available sea, air and ground forces would be swiftly concentrated there to crush the enemy. Because of the necessity of central control and coordination, the decision as to when and where to activate decisive battle operations was reserved to the highest command level, Imperial General Headquarters.60

Detailed matters discussed in connection with the plans included problems relating to the preparation and concentration of all three arms, an undertaking which exceeded in scale anything attempted by the Japanese High Command since the initial war operations in December 1941. A further vital topic of discussion centered around the most effective employment of air, sea and ground forces during the various stages of an enemy invasion.

The first major problem concerned the employment of air forces, the most mobile arm and therefore the one which could be most rapidly concentrated at any point of attack. The High Command estimated that the Allied forces would employ the same tactical pattern of invasion which they had established in the Marshalls, at Hollandia and at Saipan, i. e., carrier-based planes would first endeavor to gain air superiority by neutralizing Japanese base air forces; second, while Allied aircraft maintained control of the air, naval surface units would seek to destroy ground defense positions near the beach by concentrated shelling; and third, troop transports would begin disembarking the

[319]

assault troops.

Against these Allied tactics the Japanese heretofore had followed the practice of committing most of their available air strength in attacks directed at the enemy carriers during the first phase of invasion. The plane losses suffered in such attacks, however, generally were so high that insufficient strength remained to carry out effective attacks against the enemy's troop transport during the third and critical phase. The transports consequently were able not only to approach the landing points without having suffered any appreciable damage at sea, but to ride relatively unmolested in anchorage while the troops debarked.

In the light of this past experience, Imperial General Headquarters concluded that a change in air tactics was necessary. It was estimated that the most effective results would be obtained if the employment of the main strength of the Air forces were withheld until the third phase of the enemy attack and the maximum strength were then thrown simultaneously against both troop transports and carriers. In accordance with this plan, the High Command decided to employ the main strength of the Army Air forces in attacks against troop transports and the main portion of the Navy Air forces against enemy carriers.61 These assignments were subsequently embodied in a Army-Navy Central Agreement covering air operations, issued on 24 July.

Withholding air attacks until the third phase necessitated the fortification of airfields to withstand enemy bombing and strafing attacks during the first two phases. Additional construction was therefore planned,62 and as an added precautionary measure to reduce losses during the first and second phases, it was decided to disperse air units at fields staggered in depth.

The employment of naval surface forces, the next most mobile element, constituted the second major problem confronting Imperial General Headquarters in preparing the plans for decisive battle. The problem was rendered doubly difficult by the fact that the Combined Fleet, as a result of its heavy losses in the Philippine Sea Battle on 19-20 June, was so depleted in both aircraft carriers and, to an even greater degree, in carrier-borne air forces, that its ability to wage a modern-type sea battle was seriously impaired. No more than six carriers, of which only one was a regular, first-class carrier, remained in operation, plus two battleships fitted to launch aircraft by catapult.63 The Fleet, however, still possessed considerable surface firepower, including the two 64,000-ton super-battleships Musashi and Yamato, five other battleships, 14 heavy cruisers, seven light cruisers and about 30 destroyers.64

[320]

PLATE NO. 78

Subchaser in Action

[321]

In spite of the serious weakness in aircraft carriers, the Navy High Command opposed adoption of passive defense tactics on the ground that the Fleet would face annihilation at some later date under still more unfavorable conditions if the enemy succeeded in occupying any of the inner areas. The Third and Fifth Fleets, both of which were in the Inland Sea, would be cut off from indispensable fuel supplies of the southern area, while the Second Fleet, which had left home waters on 9 July for Lingga Anchorage, would be separated from its source of ammunition resupply in the homeland. Moreover, the sea areas in which the Navy must operate would thereafter be within range of superior enemy land-based air forces.

On the basis of this reasoning, the Navy Section of Imperial General Headquarters decided in favor of risking the full remaining strength of the Fleet in bold offensive action. Surface forces, supported by land-based air strength, would launch a concerted attack designed to catch and destroy the enemy fleet of invasion transports at the points of landing. The assault was to be facilitated by a diversionary move to draw off the enemy naval forces covering the landing operations.

Because of the absolute necessity of preventing enemy penetration of the inner defense line and the inadequate sea and air forces available to oppose such a penetration, Imperial General Headquarters also considered the possible initiation of tokko, or special-attack, tactics for the purpose of destroying the enemy at sea.65

In planning the most effective method of using the ground forces, the Army Section of Imperial General Headquarters gave particular attention to a revision of the hitherto accepted tactical concepts of defense against enemy landing operations. Almost complete reliance had hitherto been placed upon strong beach positions, with little or no emphasis on secondary defenses. The primary tactical principle had been to destroy the enemy troops from these beach positions as they attempted to come ashore. The successive defeats suffered since Tarawa, however, had demonstrated that such positions could not be decisively held under the type of devastating preparatory naval bombardment employed by the Allied forces.

As a result of the careful studies made of this problem over a period of some months, the Army Section decided that new tactics of defense should be employed in the ground phase of the projected operations. These tactics involved: (1) preparation of the main line of resistance at some distance from the beach to minimize the effectiveness of enemy naval shelling: (2) organization of defensive positions in depth to permit a successive wearing down of the strength of the attacking forces; and (3) holding substantial forces in reserve to mount counterattacks at the most favorable moment.66

Instructions based upon the conclusions reached by Imperial General Headquarters were subsequently communicated to all armies in the field.

Army Orders for the Sho-Go Operations

By the latter part of July, the basic plans covering the decisive battle operations to be conducted along the inner defense line had been completed. Imperial General Headquarters designated these operations by the code name Sho-Go, meaning "victory," and proceeded to issue implementing orders to the various Army and Navy operational commands. The basic order governing Army operations was issued by the Army Section of Imperial General Headquarters on 24 July, stating in

[322]

part as follows:67

1. Imperial General Headquarters is planning to initiate decisive action against anticipated attack by the enemy's main force during the latter part of the year.... The decisive battle area is expected to be Japan Proper, the Nansei (Ryukyu) Islands, Formosa or the Philippines. The zone of decisive action and the date of the initiation of operations will be designated by Imperial General Headquarters.

2. To accomplish their respective missions, the Commander-in-Chief, Southern Army, the Commander, Formosa Army, the Commander-in-Chief, General Defense Command, the Commander, Fifth Area Army, and the Commander-in-Chief, China Expeditionary Army will swiftly prepare for decisive action in cooperation with the Navy.

A directive implementing the above order was issued the same day by the Army Section, Imperial General Headquarters, including the following instructions:68

1. Army commanders will generally complete preparations for decisive action in their respective area by the following dates: Philippine area (Sho Operation No. 1); end of August: Formosa and Nansei Islands (Sho Operation No. 2); end of August: Japan Proper, excluding Hokkaido (Sho Operation No. 3); end of October; Northeastern area (Sho Operation No. 4); end of October.

Air operations were specifically dealt with in a Army-Navy Central Agreement which was appended to this directive. The principal stipulations of this agreement were as follows:69

1. Operational Objective:

The Army and Navy Air forces will complete preparations for decisive action by mid-August. In the event of an enemy invasion, the total Air forces of both the Army and Navy shall be concentrated in the area of decisive action and will engage and destroy the invading forces through coordinated action.

Imperial General Headquarters shall determine the zone wherein decisive action shall be executed.

2. Disposition and Employment of Air Forces:

a. The basic disposition of Army and Navy Air forces shall be as follows:

Northeast area—Twelfth Air Fleet; 1st Air Division.

Japan Proper (excluding Hokkaido)—Third Air Fleet; Air Groups attached to Third Fleet (if stationed in Japan); Training Air Army; 10th Air Division; 11th Air Division; and 12th Air Division.

Nansei Islands and Formosa Area—Second Air Fleet; 8th Air Division.

Philippines, Western New Guinea—Halmahera, and Central Pacific areas—First Air Fleet70; Fourth Air Army.

Present dispositions will be maintained on other fronts.

b. Plans for employment of Air forces:

For Sho Operation No. 1, the Navy shall concentrate the First and Second Air Fleets in the Philippines, hold the Third Air Fleet in reserve, and transfer the Twelfth Air Fleet to Japan Proper. Besides the total strength of the Fourth Air Army, the Army shall send as reinforcements to the Philippines two fighter regiments and one heavy bomber regiment from the Training Air Army, one fighter regiment, one light bomber regiment, and one heavy bomber regiment from the 8th Air Division, and two fighter regiments from the Fifth Air Army in China. The 1st Air Division shall be held as strategic reserve.

3. Allocation of Missions and Command Dispositions:

[323]

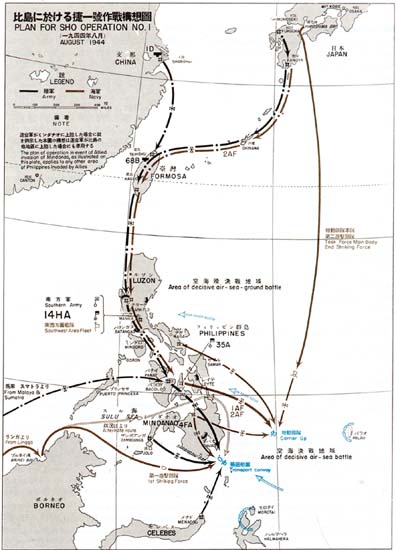

PLATE NO. 79

Plans for Sho Operation No. 1, August 1944

[324]

a. Operations in the Philippines, Western New Guinea-Halmahera, and Central Pacific areas shall be the joint responsibility of the Army and Navy Air forces. The respective missions of these forces until the development of decisive action in the Philippine area will be:

(1) Navy—Air Operations in the Central Pacific area and longrange patrols in the Philippine area.

(2) Army—Air Operations in the Western New GuineaHalmahera area.

b. In the event decisive action develops in the Philippine area, the following procedure will be followed to achieve coordinated action by both Air forces:

(1) When the emphasis is in on surface operations, Fourth Air Army units designated for attacks on enemy carriers will be placed under the tactical command of the Commander, First Air Fleet.

(2) When the emphasis is on land operations, the necessary forces of the First Air Fleet will be placed under the tactical command of the Commander, Fourth Air Army.

4. Basic Operational Procedure for Decisive Air Action:

a. Base air operations before the start of decisive action: The objective shall be the destruction of the enemy's fighting potential and the minimization of our losses by dispersing our Air forces in depth and by adopting a tactical command which is both aggressive and flexible. For this purpose, particular emphasis will be placed on frequent surprise raids against enemy bases and on timely interceptions. Direct air defense of our bases will be provided by antiaircraft fire as a rule.

b. Decisive air action against enemy amphibious attack forces: The general plan will be to send elements of our attack forces to drain the enemy carrier strength, and then to muster the entire Army-Navy air strength for bold, repeated, day-and-night attacks after permitting the enemy to come as close as possible to our bases, and to destroy both enemy carriers and troop convoys.

c. In the event of enemy carrier raids against strategic points in Japan Proper, air defenses will be strengthened, and the enemy will be attacked offensively regardless of the procedure in item (b).

The Army Section directive of 24 July also included a troop employment plan for the shifting of ground units of specified strength from various areas along the inner defense line to the invasion point. In case of the activation of Sho Operation No. 1 for the Philippines, the plan provided that the Formosan Army would dispatch a force of one infantry brigade plus supporting elements, and that reinforcements of approximately division strength would be sent from Shanghai.71 Both these reinforcement groups were to be dispatched to the northern Philippines upon receipt of orders from Imperial General Headquarters.

On the same day that the basic Sho-Go Operations order and directive were issued, Col. Yozo Miyama, Chief of Operations Section, Southern Army headquarters, along with representatives of all subordinate commands concerned, attended a conference at Imperial General Headquarters in Tokyo to discuss the broad phases of the plans. At this conference, Col. Miyama received an "Outline of Essential Instructions for Sho Operation No. 1," in which was stated the decision of the Imperial General Headquarters, Army Section that Fourteenth Army should prepare to fight the decisive ground battle on Luzon and in the event of a prior enemy incursion into the central or southern Philippines, should limit its action there to delaying the enemy and securing the local air and naval bases as long as possible.72

[325]

Cogent reasons made it appear advisable to the Army High Command to determine in advance the exact sector of the Philippines in which decisive ground action should be fought. The most important of these reasons was that Japanese troop strength was inadequate to permit the stationing beforehand of enough strength in all sectors to fight decisive action wherever the enemy might strike. Coupled with this was the expectation that the commitment of all Japanese sea and air forces to attack on the enemy invasion fleet would make it impossible to provide the necessary escort for movements of troop reinforcement from other sectors of the Philippines to the particular island which the enemy chose for his attack. Hence, decisive battle stations must be predetermined, prepared and manned in advance.

A combination of factors led Imperial General Headquarters to the selection of Luzon as the sector for decisive ground battle. The High Command estimated that the initial Allied landing would probably be made in the central or southern Philippines rather than on Luzon, and it would have preferred to fight the decisive ground action there in conjunction with the planned decisive action of the sea and air forces. However, there was no absolute certainty that the enemy would not by-pass the central and southern Philippines, nor any means of predicting, if he did attack there, which of the numerous islands he would invade. On the other hand, Luzon, because of its great value both strategically and politically, was considered certain to be invaded sooner or later. Further factors which influenced the decision were that ground operations on Luzon would be less hampered by logistic difficulties, and that Japanese troops would possess greater mobility due to the existence of a relatively well-developed transportation network.

On the basis of these considerations, Imperial General Headquarters concluded at this stage that the greatest chances of success in ground action would be obtained by massing troops on Luzon and awaiting the Allied invasion of that island. The resultant corollary was that, if the initial enemy invasion were launched in the central and southern Philippines, the Japanese ground forces in that area would fight essentially a delaying action, endeavoring to hold on as long as possible to key air and naval bases and to consume the maximum degree of enemy strength.

On 4 August, eleven days after the issuance of the Sho-Go plans, Imperial General Headquarters ordered a reorganization of the Army command in the Philippine area, setting the date of activation at 9 August. By this order, Fourteenth Army was elevated to the level of an Area Army, Lt. Gen. Kuroda stepping up to assume the new command. The Area Army was to be responsible for the over-all conduct of Army operations in the Philippines, and in addition to exercise direct command over the defense forces on Luzon.73 By the same

[326]

order, the Thirty-fifth Army was activated under command of Fourteenth Area Army to take over conduct of operations in the central and southern Philippines. Lt. Gen. Sosaku Suzuki, who had hitherto commanded the Central Shipping Transportation headquarters in Japan, was appointed Thirty-fifth Army Commander, with headquarters at Cebu.

In July and early August, Imperial General Headquarters also took action transferring additional troops to the Philippines. These troops consisted of three first-class, seasoned divisions, i. e., the 26th from the China Expeditionary Army, and the 8th Division and 2d Armored Division from the Kwantung Army, supplemented by the 61st Independent Mixed Brigade, which had been activated in Japan on 10 July.

In addition to these transfers, Imperial General Headquarters further implemented the troop employment plan applicable to Sho Operation No. 1 by designating the 1st Division,74 which was to be stationed in Shanghai under direct Imperial General Headquarters command, and the 68th Brigade, stationed in Formosa under the Formosa Army Commander, as reserves for decisive battle operations in the Philippines area. As stipulated in the Army directive of 24 July, these units were to be committed to the northern Philippines.

Meanwhile, on 5 August, the Southern Army Commander-in-Chief, Field Marshal Terauchi, called together the commanders and ranking staff officers of subordinate ground and air commands at Manila for map maneuvers to study problems involved in the execution of Sho Operation No. 1. A Southern Army order of the same date embodied the essentials of the Imperial General Headquarters Army Section directive and instructions specifically relating to the Philippines.75 Essentials of this order were as follows:76

3. The Fourteenth Area Army Commander will speedily perfect airfield installations and execute other preparations in accordance with Battle Preparations No. 11. He will conduct operations in accordance with the following:

a. Luzon will be the main area for decisive ground battle.

b. In the central and southern Philippines, the principal aim will be to hold strategic areas in order to facilitate the decisive operations of the Navy and Air forces.

Following up this order, Southern Army formulated a theater operational plan which further implemented the designation of Luzon as the sector for decisive ground operations. The plan provided that preparations for ground operations should be carried out according to the following instructions for specific areas:77

[327]

Batan and Babuyan Islands area: An element of the Area Army will secure strategic positions and bar enemy attempts to gain advance air bases.

Luzon area: The main Area Army strength will be concentrated in this principal area of decisive ground battle and will destroy the main force of the invading enemy.

Central and southern Philippines: Substantial forces will be employed to hold strategic points, block enemy attempts to advance his sea and air bases, and maintain pivotal centers of decisive sea and air operations. In particular, it is vital to secure air bases on Leyte and southeastern Mindanao.

Navy Orders for the Sho-Go Operations

Three days prior to the issuance of the Imperial General Headquarters Army order covering the Sho-Go Operations, the Navy Section of Imperial General Headquarters, on 21 July, had issued a directive outlining "naval policy for urgent operations" and ordering preparations for decisive battle to be waged in the event of enemy attack on the inner defense line. Essential portions of this directive were as follows:78

1. Operational Policy:

a. The Imperial Navy will endeavor to maintain and make advantageous use of the strategic status quo; make plans to smash the enemy's strength; take the initiative in creating favorable tactical opportunities, or seize the opportunity as it presents itself, to crush the enemy fleet and attacking forces.

b. In close conjunction with the Army, the Navy will maintain the security of sectors vital to national defense and prepare for future eventualities.

c. It will also cooperate closely with related forces to maintain the security of surface routes between Japan and vital southern sources of materials.

2. Various types of operations:

a. Operations by base Air forces: Main strength of the base Air forces will be stationed in the Homeland (Hokkaido, Honshu, Shikoku, Kyushu), the Nansei Islands, Formosa, and the Philippines, and part strength in the Kuriles, vital southern sectors and the Central Pacific, with the object of attacking and destroying the enemy fleet and advancing forces.

b. Mobile forces and other surface forces will station the majority of their operational strength in the Southwest Area and, in accordance with enemy movement, will move up to the Philippines or temporarily to the Nansei Islands. Some surface elements will be stationed to the Homeland area. Both will engage in mobile tactics as expedient, coordinating their action with that of the base Air forces to crush the enemy fleet and advancing forces.

c. Protection of surface lanes of communication and anti-submarine warfare: Important strategic points are to be protected and maintained in order to preserve the safety of surface communication between Japan and the southern area. Simultaneously, the forces concerned will maintain close cooperation in nullifying attacks by enemy task forces, air-raids from enemy bases, and the activities of enemy submarines.

3. Operations in various areas:

a. Homeland (Hokkaido, Honshu, Shikoku, Kyushu) Nansei Islands, Formosa and Philippines. (applicable also to the Bonin Islands): The Navy will cooperate with the Army and related forces, giving priority to strengthening defenses and taking all measures to expedite the establishment of favorable conditions for decisive battle. In event of enemy attack, it will summon the maximum strength which can be concentrated and hold vital sectors, in general intercepting and destroying the enemy within the operational sphere of the base Air forces.

[328]

Following the issuance of the Army's basic Sho-Go Operations order on 24 July, the Navy Section of Imperial General Headquarters on 26 July issued a new directive fitting its previous outline of naval policy for urgent operations into the framework of the Sho-Go Operations plan.79 To implement both these directives, the Combined Fleet on 1 August issued Combined Fleet Top Secret Operations Order No. 83, which specified the following general missions of the naval forces in the Sho-Go Operations:80

1. Operational Policy:

a. The Combined Fleet will cooperate with the Army according to the operational procedures specified by Imperial General Headquarters for the Sho-Go Operations in order to intercept and destroy the invading enemy in decisive battle at sea and to maintain an impregnable strategical position.

2. Outline of Operations:

a. Preparations:

(1) Air bases will be prepared as rapidly as possible in the Philippines to permit deployment of the entire air strength of the First and Second Air Fleets. Air bases in the Clark Field and Bacolod areas will be organized rapidly in accordance with the Army-Navy Central Agreement.

b. Operations:

(1) Enemy aircraft carriers will be destroyed first by concentrated attacks of the base air forces.

(2) Transport convoys will be destroyed jointly by the surface and air forces. If the enemy succeeds in landing, transports carrying reinforcements and the troops already on land will be the principal targets so as to annihilate them at the beachhead.

(3) Surface forces will sortie against the enemy landing point within two days after the enemy begins landing. All-out air attacks will be launched two days prior to the attack by the surface forces.

Combined Fleet Top Secret Operations Order No. 84, also issued on 1 August, fixed the new tactical grouping of naval forces for the Sho-Go Operations. Almost the entire surface combat strength of the Fleet was included in a Task Force placed under the overall command of the First Mobile Fleet Commander, ViceAdm. Jisaburo Ozawa. This force was broken down into three tactical groups: (1) the Task Force Main Body, directly commanded by ViceAdm. Ozawa and consisting of most of the Third Fleet (carrier forces): (2) the First Striking Force, commanded by Vice Adm. Takeo Kurita and made up of the Second Fleet with part of the 10th Destroyer Squadron attached: (3) the Second Striking Force, commanded by Vice Adm. Kiyohide Shima and composed of the Fifth Fleet plus two destroyer divisions and the battleships Fuso and Yamashiro.81

The manner in which these tactical forces were to be employed in the planned decisive battle operations was set forth in more detail in an "outline of operations" annexed to Combined Fleet Top Secret Operations Order No.

[329]

85, issued on 4 August. The gist of this outline applying to surface force operations was as follows:82 (Plate No. 79)

1. Disposition of forces: The First Striking Force will be stationed at Lingga Anchorage, while the Task Force Main Body and the Second Striking Force will be stationed in the western part of the Inland Sea. However, if an enemy, attack becomes expected, the First Striking Force will advance from Lingga Anchorage to Brunei, Coron or Guimaras; the Task Force Main Body and the Second Striking Force will remain in the Inland Sea and prepare to attack the north flank of the enemy task force.

2. Combat operations: If the enemy attack reaches the stage of landing operations, the First Striking Force, in conjunction with the base Air forces, will attack the enemy in the landing area.

a. If the enemy attack occurs before the end of August, the Second Striking Force, plus the 4th Carrier Division and part of the 3d Carrier Division, will facilitate the operations of the First Striking Force by launching effective attacks against the enemy and diverting his task forces to the northeast.

b. If the enemy attack occurs after the end of August, the Second Striking Force will be incorporated under the command of the Task Force Main Body as a vanguard force. The Main Body will then assume the mission of diverting the enemy task forces to the northeast in order to facilitate the attack of the First Striking Force, and will also carry out an attack against the flank of the enemy task forces.83

During August, the Navy Section of Imperial General Headquarters also took action to give the Combined Fleet more unified operational control of naval forces in order to facilitate the execution of the Sho-Go plans. On 9 August the General Escort Command and units assigned to naval stations were placed under operational command of the Combined Fleet, and on 21 August the China Area Fleet was similarly placed under Combined Fleet command.84

In line with the broad plans handed down by Imperial General Headquarters, Army and Navy preparations for decisive battle in the Philippines area were pushed ahead on a first priority basis during August.85 Particular urgency was attached to the early completion of preparations by the Air forces, which were to play the key role in the initial phases of an enemy invasion.

Shipping to the Philippines continued to be severely limited, but air reinforcements and supplies arrived steadily. Meanwhile, ground units made every effort to speed the airfield construction program. By the end of September, over 60 fields considered good enough for

[330]

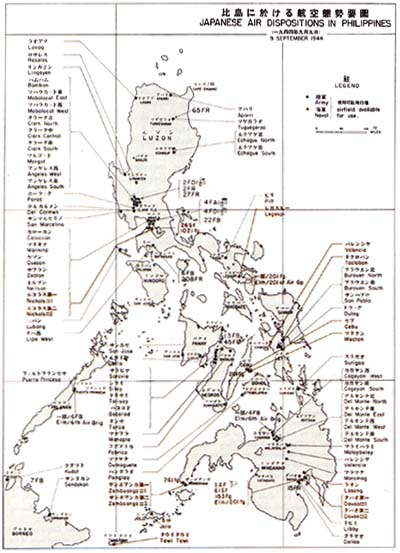

all-weather use were in operational condition.(Plate No. 80)

Completion of the movement of the 2d and 4th Air Divisions from Manchuria brought the total strength of the Fourth Air Army in the Philippines up to approximately 420 aircraft of all types by the latter part of August.86 The 2d Air Division, which contained all the combat flying units, commanded five air brigades, one air regiment, and other small elements.87 These were deployed principally at the Clark Field and Bacolod bases, where they had been undergoing intensive training since their arrival from Manchuria.

On 7 September, the 2d Air Division Commander with part of the headquarters staff moved to Menado in the Celebes.88 Prior to his departure, the 2d Air Division Commander ordered battle preparations for three of the division's air regiments in order to bolster the air strength of the 7th Air Division,89 which was deployed in the Menado area for support of Second Area Army operations. Minor elements of the 2d Air Division were also dispatched to bases on North Borneo.

Parallel with the strengthening of the Fourth Air Army, the reorganization and replenishment of the naval land-based air forces also proceeded according to plan. By the end of July, the combat flying elements of the 23d Air Flotilla in the Celebes and the 26th and 61st Air Flotillas at Davao had been reconstituted as the 153d, 201st and 761st Air Groups, respectively.90 These three combat air groups, under an Imperial General Headquarters Navy order of 10 July, were to be detached from their respective flotillas and operate under direct command of the First Air Fleet.91

The headquarters of the First Air Fleet, which had been virtually wiped out in the Marianas operations, was under reorganization in Japan. On 7 August the reorganization was completed, and the newly appointed Air Fleet commander, Vice Adm. Kimpei Teraoka, left shortly thereafter with his staff to set up the headquarters at Davao.92 On 10 August, to unify the command of naval forces in the Philippines, Imperial General Headquarters transferred the First Air Fleet from direct Combined Fleet command to that of the South

[331]

PLATE NO. 80

Japanese Air Dispositions in the Philippines, 9 September 1944

[332]

west Area Fleet, which already controlled all naval ground and surface elements in the Philippines area.93

With the establishment of First Air Fleet headquarters at Davao, the flying elements began an intensive training program to raise combat efficiency. By the early part of September most of these elements were deployed at bases on Mindanao and Cebu in readiness to carry out the missions assigned to the Navy Air forces. The combat air groups, however, were still short of both trained flying personnel and aircraft.94 Despite the attachment of the Army's 15th Air Regiment equipped with long-range reconnaissance planes, the First Air Fleet was unable to perform its preliminary mission of patrolling the waters east of the Philippines with complete adequacy.

Back at Homeland bases, the Second Air Fleet, which had been activated on 15 June, was conducting a program of specialized training in preparation for its scheduled deployment to Formosa and Ryukyu Island bases in September.95 Under the Army-Navy Central Agreement on air operations (cf. p. 294), the Second Air Fleet was to advance from these bases to the Philippines and reinforce the First Air Fleet upon the activation of Sho Operation No. 1.

To the Second. Air Fleet was assigned the particular mission of attacking enemy carriers. Its flying units were therefore specially trained and equipped for this purpose, and a special force designated as the "T" Attack Force was organized to carry out surprise attacks at night or under adverse weather conditions.96 The bulk of the best pilots in the Navy Air forces were assigned to this unit.97 In addition, the 7th and 98th Air Regiments (Army), equipped with new Type IV twin-engine bombers, were attached to the Second Air Fleet on 25 July.98 The bombers were modified for carrying torpedoes, and training instituted in executing attacks on carriers.

Detailed plans for air operations under the Sho No. 1 plan were meanwhile under joint study by the Army and Navy High Commands in Manila. By early September, the main lines of these plans had been worked out as follows:99

1. Prior to the start of decisive battle operations, surprise hit-and-run attacks will be directed against enemy land-based air forces in order to gradually reduce their strength. Enemy air attacks against our bases will be intercepted in planned localized actions so as to minimize the dissipation of our combat strength.

2. In the event of enemy task force raids, designated air units will execute attacks on the enemy force at night or in poor weather. Under favorable circumstances, daylight attacks may also be carried out.

3. In the event of enemy invasion operations, the invading forces will be drawn as close as possible before the full weight of our Air forces is thrown into

[333]

the attack. Concentrated attacks by all available air units will begin one day prior to the anticipated day of arrival of the invasion convoy at the landing point (X-Day), to be announced later.

a. Attacks will be carried out in accordance with the Table of Assignments decided by Imperial General Headquarters.100

b. In attacking the enemy carrier groups, the first target will be the regular carrier group in order to facilitate subsequent attacks on the transport group.

c. Attacks will be launched against the transport group, as a rule, after the enemy ships have entered the anchorage. Fighter units and surprise attack units will attack first, followed by all types of aircraft.

While Army and Navy Air forces girded themselves for decisive battle, the widelydispersed naval surface forces also continued preparations for the vital role they were to play in the Sho-Go Operations. At Lingga Anchorage, South of Singapore, the First Striking Force concentrated on training in night attacks and the use of radar fire control, the latter of which had not been extensively employed hitherto. The Task Force Main Body and the Second Striking Force remained in the Inland Sea, the former still occupied primarily with the replenishment and training of its carrier air groups.

On 10 August the 1st Carrier Division, reorganized around two newly-commissioned regular carriers, was added to the Task Force Main Body.101 Vice Adm. Ozawa, Task Force Commander, meanwhile set 15 October as the target date for completion of the reorganization and training of the 3d and 4th Carrier Division air groups.102 Concurrently with these preparations, steps were taken to strengthen the antiaircraft armament of combat units.103

Ground force strength in the Philippines also mounted steadily as the units newly assigned by Imperial General Headquarters in July and early August began arriving. Movement of the 26th Division from Shanghai to Luzon was completed by 29 August. During September advance echelons of the 8th Division, 2d Armored Division, and 61st Independent Mixed Brigade arrived. Movement of the remaining strength of these units continued in October, and the last elements of the 61st Independent Mixed Brigade reached the Batan Islands, off northern Luzon, only in November. Enemy submarine attacks inflicted substantial troop losses during these movements despite efforts to ensure adequate protection of the convoys.104

Arrival of the 8th and 26th Divisions, 2d Armored Division, and 61st Independent Mixed Brigade brought the major combat forces

[334]

of the Fourteenth Area Army up to nine divisions and four independent mixed brigades. In line with Imperial General Headquarters and Southern Army directives designating Luzon as the principal area of decisive ground battle, Lt. Gen. Kuroda retained all the newly-assigned forces under direct Area Army command for the defense of Luzon. The allocation of troop strength was thus as follows:105

Fourteenth Area Army (Luzon, N. Philippines)

8th Division

26th Division

103d Division

105th Division

2d Armored Division

58th Independent Mixed Brigade

61st Independent Mixed Brigade

Area Army Reserve: 33d Infantry Regiment

55th Independent Mixed Brigade

Attached troops

Thirty-fifth Army (Central Southern Philippines)

16th Division (less 33d Inf. Regt.)

30th Division

100th Division

102d Division

54th Independent Mixed Brigade

Attached troops

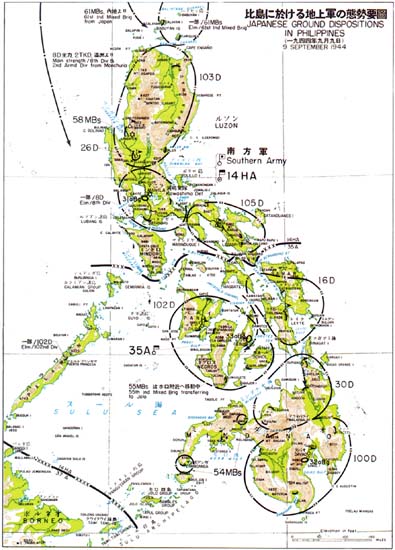

Troop dispositions ordered by Fourteenth Area Army for the defense of Luzon were as follows: 8th Division in the Batangas area; 103d Division on northern Luzon, with headquarters at Baguio; 105th Division on southern Luzon, with headquarters at Naga; Kawashima Detachment (elements of 105th Division) in the Lamon Bay area; 58th Independent Mixed Brigade, reinforced by the 26th Independent Infantry Regiment,106 in the Lingayen area; 61st Independent Mixed Brigade on the Batan and Babuyan Islands107; 26th Division and 2d Armored Division in the central plain area as Luzon reserve.108

While these dispositions were still being put into effect, Fourteenth Area Army headquarters in the latter part of August reappraised the enemy situation, concluding on the basis of weather conditions and the progress of enemy air concentrations that an attack on the Philippines might be expected at any time after the end of August. Enemy intentions were estimated as follows:109

1. Enemy forces will advance on the Philippines either directly from the New Guinea area or Saipan, or after capturing intermediate bases.

2. The initial landing will probably be made in the central of southern Philippines, somewhere between (and including) Leyte and Mindanao.110

3. The possibility of a direct attack on Luzon must also be considered. In this eventuality, probable landing points are the Legaspi, Baler Bay, Dingalan Bay, Lamon Bay, Aparri and Lingayen sectors. Should the enemy contemplate an early advance to Formosa and the Ryukyu Islands, his plans will include

[335]

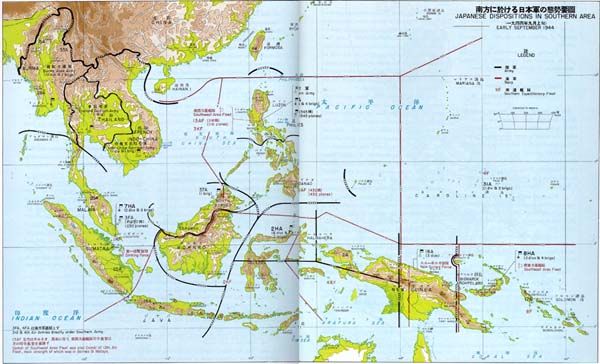

PLATE NO. 81

Japanese Dispositions in Southern Area, September 1944

[336-337]

securing air and naval bases in the vicinity of Aparri.

4. The enemy will be able to employ from eight to ten infantry divisions, including a considerable number of airborne and tank units, if Luzon is invaded.

5. Landings will be powerfully supported, and will be preceded and accompanied by intensive neutralization air attacks on Japanese air bases.

Final Preparations, Central and Southern Philippines

As the critical period for the anticipated Allied invasion drew nearer, the Thirty-fifth Army in the central and southern Philippines, where the initial enemy blow was expected to fall, hastened to effect last-minute preparations. The Army's general missions had been laid down by Fourteenth Area Army in an order to the Thirty-fifth Army Commander, Lt. Gen. Suzuki, when the latter assumed command on 9 August. These missions were:111

1. To support and execute preparations for air operations in the central and southern Philippines.

2. To defend the central and southern Philippines and, in particular, secure air and naval bases in that area.

3. In the event of an enemy landing, to conduct operations designed to reduce the fighting power of the enemy forces as much as possible and to prevent the establishment of enemy bases.

Since May 1944 the ground forces in the central and southern Philippines area had been primarily engaged in the air base construction program together with air force ground personnel. However, Fourteenth Area Army had decided that all ground forces must switch over to ground defense preparations at the end of August. Only a few weeks still remained before this deadline, and Lt. Gen. Suzuki consequently ordered work on the projected bases to be accelerated as much as possible.112

The fact that some of the bases, particularly those at Davao and at Burauen, on the east coast of Leyte, lay close to possible enemy landing points caused marked concern on the part of the ground force command. Because of the difficulty of securing them, ground force staff officers recommended that emphasis be shifted to the development of major bases farther inland, but this view was not accepted by the Air forces on the ground that coastal bases were essential to give them maximum operational range against an approaching enemy invasion force.113 Air force opposition, plus the shortness of time available, resulted in a decision to avoid any change in plan.

When Lt. Gen. Suzuki took over his command, Thirty-fifth Army strength was thinly scattered over the central and southern islands. The 16th Division, less the 33d Infantry Regiment,114 was stationed on Leyte, with an element of about battalion strength garrisoning Samar.115 The 102d Division was dispersed over

[338]

PLATE NO. 82

Japanese Ground Dispositions in the Philippines, September 1944

[339]

the islands of the Visayan Sea. The 30th Division was on the northern tip of Mindanao around Surigao. The 100th Division occupied other key points on Mindanao from Zamboanga on the west to Dansalan on the north and Davao on the southeast. A force of only about one battalion was stationed in the Davao area. The 54th Independent Mixed Brigade was in the vicinity of Cebu.

Lt. Gen. Suzuki summoned his subordinate commanders to Cebu on 18 August for a conference on the operational plans to be employed in the event of an Allied landing in the Army area.116 The substance of these plans was as follows:117

1. Operational objectives: The Army will secure the central and southern Philippines, particularly the air bases near Davao and on Leyte, and will destroy enemy landing forces in coordination with the decisive operations of the sea and air forces.

2. Outline of Operations:

a. The Army will maintain a tight defense in the Davao sector and the Leyte Gulf area with the 100th Division and the 16th Division, respectively. The main body of the 30th Division and elements of the 102d Division will constitute a mobile reserve to be committed to any key area which the enemy may attack.

b. Suzu Operation No. 1: If the principal effort of the enemy invasion is directed at the Davao sector, the main body of the 30th Division, three reinforced infantry battalions of the 102d Division, and other forces will be committed to the area.

c. Suzu Operation No. 2: If the principal effort of the enemy landing is directed at the Leyte Gulf area, the main body of the 30th Division, two reinforced infantry battalions of the 102d Division, and other forces will be landed at Ormoc to reinforce the 16th Division.

d. If the enemy lands powerful forces at both Davao and Leyte Gulf, it is tentatively planned to commit the main body of the 30th Division to Davao and elements of the 102d Division to Leyte.

In accordance with these plans, the 100th Division was immediately ordered to concentrate its main strength in the Davao area, while the 54th Independent Mixed Brigade was dispatched from Cebu to take over the mission of defending western Mindanao and Jolo Island. The main strength of the 30th Division, consisting of the division headquarters and two reinforced infantry regiments, was directed to move from Surigao to the vicinity of Malaybalay and Cagayan, a centralized location more suited to the division's mission as mobile reserve.118 The 16th Division on Leyte and 102d Division in the Visayan area were not affected by this regrouping.

Naval ground forces in the central and southern Philippines were also being reinforced and regrouped. During August and September, nine naval construction units with a total strength of about 9,000 arrived in the Philippines, a portion of this strength being allocated to the central and southern islands.119 The 33d Special Base Force was activated early in August at Cebu. The 36th Naval Guard unit at Guimaras Anchorage was ordered to move to Leyte in early October to expedite defense preparations in the vicinity of the naval airfield at Tacloban. The 32d Special Base Force still remained responsible for the defense of naval and harbor installations at Davao. These

[340]

various units were primarily concerned with the construction of such fortifications as were necessary for the direct protection for naval installations.

The primary mission of the 16th Division on Leyte was to secure the vital air bases at Tacloban, Dulag and Burauen. Until midsummer, however, the division was so occupied in the construction of new airstrips and in antiguerrilla operations that organization of ground defenses had not proceeded beyond the construction of coastal positions facing Leyte Gulf.120 The construction of inland positions did not get under way until July, when the main strength of the 9th Infantry Regiment was moved back from Samar to Leyte to speed defense preparations.

Concerned by the 16th Division's overconcentration on beach defenses, Thirty-fifth Army in August directed Lt. Gen. Makino to place greater emphasis on the preparation of defenses in depth and suggested that strong positions for the main body of the division be organized along an axis running through Dagami and Burauen. In compliance with these instructions, work on inland positions was accelerated in September, although seriously hampered by the difficult terrain and guerrilla activity.

Concurrently with these preparations, the Army began building up reserves of ammunition and rations with a view to the possible interruption of supplies from the rear during an enemy attack. Each division stocked sufficient food to be self-sustained for a period of one month and from 1,050 to 1,500 tons of ammunition.121 In addition, a reserve supply of one month's rations and 750 tons of ammunition was stored on Cebu.