CHAPTER III

POLITICO-MILITARY EVOLUTION TOWARD WAR

The sudden, far-flung attacks unleashed by Japan's armed forces against Pearl Harbor and the Asiatic possessions of Great Britain and the United States before dawn on 8 December 1941 rang up the curtain on the Pacific War. It was to be a gigantic struggle, fought over an area covering 38 million square miles of the globe and every kind of terrain from the tundra wastes of the Aleutians to the jungles of Burma and New Guinea.

This desperate act was characterized by the enemy press as "national suicide," but the politico-military clique which gambled Japan's fate in war saw it as the only alternative to a retreat from policies and ambitions to which they stood irrevocably committed.

The Manchurian Incident of 18 September 1931 had evoked a strong reaction in the United States, expressed in repeated diplomatic protests from Washington. Great Britain aligned itself with the United States when hostilities spread to the Shanghai area in March 1932, imperiling British interests, and both nations supported China in an appeal to the League of Nations. The final League report adopted in February 1933 was so adverse that Japan, rather than yield, served notice of withdrawal from League membership.

Anti-Japanese sentiment intensified in Britain and the United States following the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War on 7 July 1937.1 On 1 July 1938, six months after the embarrassing sinking of the American gunboat Panay by Japanese Navy planes, the United States Government imposed a so-called "moral embargo" on the export of aircraft and aircraft parts to Japan. It was the initial step in a progressively more stringent economic blockade.

On 3 November 1938 Japan proclaimed the establishment of a "New Order for East Asia".2 The United States and Britain promptly recognized this as a covert threat to China's "Open Door" and countered with loans of 25 million dollars and 50 million pounds,

[30]

respectively, to the Chungking Government. The League of Nations on 20 January 1939 also proffered aid to Chiang Kai-shek.

Japanese troops occupied Hainan Island, off the South China coast, in February 1939 and at the same time closed the Yangtze to all neutral commercial shipping. On 26 July of the same year, the United States served notice of its intention to abrogate the Japanese-American Treaty of Commerce and Navigation, the trade basis upon which the two countries had operated since 1911. In December 1939 aircraft plans and equipment as well as equipment used in manufacturing high-grade aircraft gasoline were added to the list of items, export of which to Japan was forbidden.

On 30 March 1940 the Wang Ching-wei Government was formally inaugurated at Nanking in opposition to the Chungking Government. The United States promptly refused recognition of the new regime, as a Japanese "puppet," and offered Chiang another loan, this time for 20 million dollars. This was followed on 2 July with enactment of an export control law covering national defense materials, the implied intent of which was to curb the Japanese national potential.

Under this law an export license system was first applied to aircraft materials and machine tools, and was later broadened to include highgrade gasoline; high-grade lubricating oil and first class scrap iron.3 Thereafter new items were frequently added to the list. Since Japanese domestic production of crude oil supplied but 1,887,000 barrels of the minimum of 34,600,000 barrels annually required to maintain national defense and economic life,4 the American curb on oil exports alone was regarded in Japanese governing circles as a crippling blow to Japan's basic industry and, indirectly, to her national safety.

On 22 July 1940 the second Konoye Cabinet took office and, five days later, carried out a sweeping revision of basic Japanese policies in the light of changes in the world situation.5 This revision committed Japan:

1. To strive for speedy conclusion of the China Incident by cutting off all assistance to Chungking from outside powers.

2. To maintain a firm stand toward the United States on one front, while strengthening politicalities with Germany and Italy and ensuring more cordial diplomatic relations with Russia.

3. To open negotiations with the Dutch East Indies in order to obtain essential materials.6

Japan's anxiety to end the China stalemate was a paramount consideration. The hostilities on the Continent had bogged down and constituted a severe drain on the nation's resources. Acting under the decisions of 27 July, the Konoye Cabinet therefore concluded a

[31]

"Joint Defense Agreement " with the French Vichy Government under which Japanese troops were dispatched to northern French Indo-China, for the purpose of blocking the last remaining supply route to Chungking.7 Foreign Minister Yosuke Matsuoka explained the limited motive of this act in a special plea to the United States Ambassador in Tokyo, but Washington countered with an added loan of 25 million dollars to Chiang Kai-shek.8

In the same month Japan sought relief from the American oil embargo by dispatching a special mission headed by Commerce Minister Ichizo Kobayashi to Batavia to negotiate an agreement with the Dutch East Indies, the major oil-producing country in the Far East. Ambassador Kenkichi Yoshizawa took over the negotiations from December 1940, but the parleys finally ended in failure in June 1941.9 As a corollary, French Indochina later failed to deliver to Japan rice and rubber in the amounts fixed by an agreement reached in May 1941.

Four days after the dispatch of troops into northern Indochina, Japan implemented another decision of the July Liaison Conference by concluding the controversial Tripartite Military Alliance with Germany and Italy on 27 September 1940. The professed object of the alliance was to deter the United States from going to war in either the Atlantic or Pacific,10 but whatever Japan's real motives, the pact merely increased British and American suspicion of Japanese intentions and brought on new countermeasures.

In October the United States issued a general evacuation order to all Americans within the "East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere". Since early in the year, the bulk of the United States Fleet remained concentrated in Hawaiian waters,11 and on 13 November Britain established a new Far East Military Command in Singapore. Malaya, Burma, and Hongkong were placed under this command, and military preparations were pushed in close liaison with Australia and New Zealand.

Beginning early in 1941, Japanese fears were heightened by a series of secret staff conferences among high-level Army and Navy representatives of the United States, Britain, China, and the Netherlands. In particular, the Manila conference in April, which was attended by the Commanding General, Philippines Department (Major General George Grunert), the United States High Commissioner to the Philippines (The Hon. Francis B. Sayre), the British Commander-in-Chief for the Far East (Air Marshal Sir Robert Brooke-Popham), the Commander of the United States Asiatic Fleet (Admiral Thomas C. Hart), and the Acting Governor-General of the Netherlands East Indies (The Hon. Hubertus van Mook), was interpreted by Japan as a sign that the so-called ABCD Powers were formulating concrete plans of immediate military collaboration.

Japanese intervention in the border controversy between Thailand and Indochina in February 194112 was followed three months

[32]

later by new American and British loans of 50 million dollars and ten million pounds, respectively, to the Chungking Government. The United States further bolstered this financial aid by extending the Lend-Lease Act to cover arms shipments to China.

In April 1941 Japan realized one of its major diplomatic objectives with the conclusion of the Japanese-Soviet " Non-Aggression Pact." However, the outbreak of the Soviet-German war only two months later created an entirely new situation. The Konoye Cabinet resigned on 16 July, reassembling two days later under the same Premier but with Matsuoka, the architect of the Axis Pact, replaced as Foreign Minister by Admiral Teijiro Toyoda.13 The new cabinet was geared to rehabilitate relations with the United States, a course which conservative Navy elements had stoutly advocated.14

The American Government refused to take seriously the conciliatory trend of the new government line-up since Japanese troops shortly moved into southern French IndoChina;15 and the United States retaliated on 26 July by freezing all Japanese assets. London took similar action, also abrogating the British, Indian, and Burmese commercial treaties with Japan, and the Netherlands Government followed suit.

Japan now found its trade cut off with all areas except China, Manchuria, Indochina, and Thailand. Economic rupture was complete with the United States, Britain, and the Netherlands, who controlled the key materials essential to Japan's national defense and industrial existence. The gradual decline of the nation's power potential was inferentially inevitable.

The stoppage of fuel imports assumed paramount strategic importance. Even if Japan were to suspend all industrial expansion and further military preparations, and to undertake an epochal increase in synthetic petroleum production, it was estimated that approximately seven years would be required before output would reach the annual consumption level of 34,600,000 barrels.16 Meanwhile, essential industries dependent upon liquid fuels would be paralyzed within a year. In two years the Japanese Navy would be immobilized.

An international impasse was fast approaching, but Japan's leaders in August 1941 hesitated to take the final plunge.

In a war against the material power of Britain and the United States, Japan's inherent economic weakness seemed to make the risk too great. Premier Konoye, who had long

[33]

subscribed to this view,17decided to make a new effort to break the deadlock in the Japanese-American negotiations.18 His Memoirs record:

During this period I racked my brains in search of some way to overcome the crisis between Japan and America. Finally I made the firm resolution to attempt a personal meeting with the President. I revealed my intention to the War and Navy Ministers for the first time on the evening of 4 August....

The War and Navy Ministers listened tensely to my resolution. They could not reply at that meeting, but later the same day the Navy expressed complete approval and voiced hope for the success of the proposed meeting. The War Minister replied by written memorandum which stated:

". . . .The Army raises no objections, provided however that the Premier firmly adheres to the fundamental principles of the Empire's revised proposal [to the United States] and provided that if, after every effort has been made, the President still fails to understand the Empire's real intentions, and proceeds along the present line of American policy, Japan will firmly resolve to face war with the United States."19

The Konoye proposal was laid before President Roosevelt on 17 August and met with an initially favorable response. However, the State Department's insistence that the meeting be held only after a prior agreement on basic principles resulted in a stalemate.20 The sands of diplomacy were running out.

Amidst this atmosphere of high tension, the Emperor on 6 September summoned the Cabinet and representatives of the Army and Navy High Command to a conference at which, for the first time, the question of peace or war was squarely posed. Deliberation centered upon an "Outline Plan for the Execution of Empire Policies " (Teikoku Kokusaku Suiko Yoryo), which provided:

1. In order to guarantee the existence and defense of the Empire, preparations for an eventual war against the United States, Great Britain and the Netherlands shall be completed approximately by the latter part of October.

2. Concurrently with the above, the Empire will exert every effort to secure realization of its demands through diplomatic negotiations with the United States and Great Britain. [The minimum terms which Japan would accept in an agreement with the United States were set forth separately.]

In the event that these negotiations fail to achieve the Empire's demands by the early part of October, it shall immediately be resolved to go to war with the United States, Great Britain, and the Netherlands.21

Speaking for both Army and Navy High

[34]

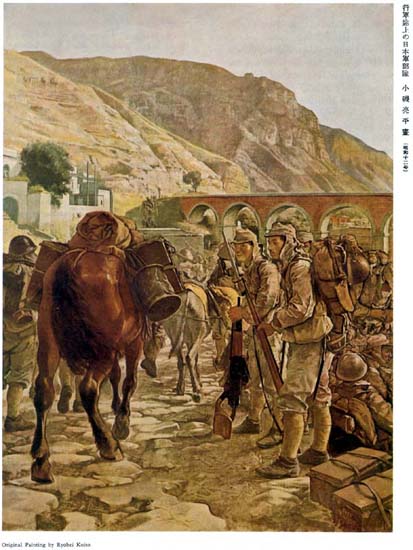

PLATE NO. 7

Japanese Column on the March

[35]

Commands, Admiral Osami Nagano, Chief of the Navy General Staff, backed up the plan with a warning that Japan's power to fight was steadily declining due to exhaustion of essential war materials and the increased military preparations of the ABCD Powers. Instead of " letting time slip idly by," he declared, the nation must first push its own war preparations and, if diplomacy fails, "advance bravely into offensive war operations." The statement was especially significant because it reflected the views of the Navy, the role of which would be of paramount importance in war with the United States. Essential extracts follow:22

The High Command sincerely hopes that the Government will exhaust every possible means of settling the present situation diplomatically. However, if Japan should be obliged to resort to war, the High Command, from the standpoint of military operations, is of the opinion that the gradual exhaustion of most of the country's essential materials such as petroleum, is lowering the national defense power, and that, if this continues, Japan in the end will fall irrevocably into a condition of impotency.

Meanwhile the United States, Britain, and other Powers are swiftly reinforcing their military establishments and strategic defenses in the Far East, and war preparations in these countries, especially in the United States, are likewise being greatly accelerated. Consequently, by the latter half of next year, the United States will be far ahead in its preparations, and Japan will be placed in an extremely difficult position.

Under such conditions, it is highly dangerous for Japan to let time slip idly by without attempting to do anything. I think that Japan should, first of all, carry out preparations as best it can; and then, if our minimum demands essential to self-defense and national existence are not accepted in the diplomatic negotiations and war finally becomes inevitable, we should not lose our opportunity but should advance bravely into offensive war operations with firm resolution, thus seeking the salvation of our country.

In regard to the outlook for such operations, it can be considered from the outset that the probability of an extended war is extremely great. Japan, therefore, must have the determination and the preparations to conduct an extended war. It would be just what we are hoping for if the United States, seeking a quick decision, challenged us with its main naval strength.

Considering the present position in the European war, Great Britain can dispatch to the Far East only a very limited portion of its naval strength. Hence, if we could intercept the combined British and American fleets in our own chosen area of decisive battle, we are confident of victory. However, even victory in such a battle would not mean the conclusion of the war. In all probability, the United States will shift its strategy to a long war of attrition, relying upon its invincible position and dominant material and industrial strength.

Japan does not possess the means, by offensive operations, to overcome its enemies and force them to abandon the war. Hence, undesirable as an extended war would be due to our lack of resources, we must be prepared for this contingency. The first requisite is immediate occupation of the enemy's strategic points and of sources of raw materials at the beginning of the war, thus enabling us to secure the necessary resources from our own area of control and to prepare a strong front from an operational viewpoint. If this initial operation succeeds, Japan will be able to establish a firm basis for fighting an extended war even though American military preparations progress according to schedule. For Japan, through the occupation of strategic points in the Southwest Pacific, will be able to maintain an invincible front. Thereafter, much will depend upon the development of our total national strength and the trend of the world situation.

Thus, the outcome of the initial operations will largely determine whether Japan will succeed or fail in an extended war, and to assure the success of the initial operations, the requisites are:

1. Immediate decision on whether to go to war, considering prevailing circumstances in regard to relative Japanese and enemy fighting strength;

[36]

2. Assumption of the initiative;

3. Consideration of meteorological conditions in the zone of operations to facilitate these operations.

It is necessary to repeat that the utmost effort must be made to solve the present crisis and assure Japan's security and development by peaceful means. There is absolutely no reason to wage a war which can be avoided. But to spend our time idly in a temporizing moment of peace, at the price of later being obliged to engage in war under unfavorable circumstances, is definitely not the course to take in view of the Empire's program for lasting prosperity.

Although the conference finally adopted the "Outline Plan," Baron Yoshimichi Hara, President of the Privy Council, pressed for further clarification by the High Command of the apparent subordination of diplomacy to preparations for war.23 The Emperor himself, in a rare departure from constitutional precedent, intervened to second the demand, voicing regret that the Army and Navy had not made their attitude fully clear.

With this, His Majesty took from his pocket a sheet of paper on which was written a verse composed by the Emperor Meiji:

"When all the earth's oceans are one,

Why do the waves seethe and the winds rage ?"Reading this aloud, His Majesty said, "I have always endeavored to spread the peace-loving spirit of the late Emperor by reciting this poem."

Silence swept the chamber, and none uttered a word....24

After this dramatic moment Admiral Nagano again rose to express "trepidation at the Emperor's censure of the High Command" and to assure His Majesty that "the High Command places major importance upon diplomatic negotiations and will appeal to arms only in the last resort."25 Nevertheless, failing diplomatic success within a fixed time limit, Japan now stood committed to war.

In actuality, Japanese military preparations for the "Great East Asia War" far antedated the outbreak of hostilities. Even long before the decision to fight was taken on the highest policy-making level, the Army and Navy had independently begun gathering intelligence, making clandestine aerial surveys, compiling maps, experimenting with new-type weapons

[37]

and conducting special types of training which were specifically applicable to an eventual war against the United States, Great Britain, and the Netherlands.

As early as July 1940, Japanese Army intelligence possessed detailed information regarding order of battle and troop dispositions in Australia.26 Between 27 November and 15 December 1940, a year before Pearl Harbor, Japanese aircraft successfully carried out photographic reconnaissance of parts of northern Luzon, including the Lingayen Gulf, Vigan, and Aparri coastal areas27 where the Philippine invasion forces were to land following the outbreak of war.

Intelligence data regarding troop and air strength, ground force dispositions, airfields, harbors and fortifications were also assembled well in advance of hostilities for Java, Sumatra, Singapore, New Guinea, and the Philippines.28 To assure the success of the Pearl Harbor attack, special intelligence arrangements were set up to obtain accurate, up-to-date reports on the number and location of American naval units in the harbor.29

Midget submarines, the precursors of Japan's tokko (special attack) weapons,30 had been secretly developed by the Navy as early as 1934, but as war with the United States grew imminent during the summer of 1941, experiments were rushed to completion at the Kure Naval Station in attaching these small craft to long-range mother submarines capable of carrying them to a distant zone of operations and then releasing them for attack upon designated targets. Five of these suicide craft were used for the first time in the attack on Pearl Harbor.31

During the late summer and fall of 1941 Japanese units destined to take part in the invasions of the Philippines, the Dutch East Indies and Malaya were put through intensive training in amphibious operations and jungle warfare along the South China coast and in special training areas near Canton, on Hainan Island, and in Indochina Morale pamphlets, special military manuals, and training guides all based on the assumption of war against Britain and the United States were prepared for advance distribution.32

Following the 6 September Imperial conference, the tempo of Japan's war preparations sharply mounted. Steps were taken to mobilize and fit out about 1,500,000 tons of shipping for Army and Navy use. At the same time the assembly of the troops and supplies required for operations against the United States, Britain

[38]

and the Netherlands, and their concentration in preliminary staging areas in Japan Proper, Formosa, and South China were begun. Actual organization of the various southern invasion forces and the deployment of operational strength in the areas where hostilities were to begin, were to be carried out only after the final decision to go to war had been taken. According to the 6 September plan, this decision had to be made by mid-October.33

Only four days after the Imperial conference of 6 September had debated the issue of war or peace, the top-ranking staff officers and fleet commanders of the Navy assembled at the Naval War College in Tokyo to take part in the annual "war games." The problem set for the games was an invasion of the Southern area, but a restricted group of the highest officers of the Combined Fleet simultaneously studied behind barred doors technical problems involved in a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor.34

On 10 November, the general terms of ArmyNavy cooperation in the Southern operations were agreed upon in Tokyo, and between 14 and 16 November detailed operational plans were elaborated by the Fleet and Army commanders directly concerned in a conference held at the headquarters of the Iwakuni Naval Air Group, on the Inland Sea near Hiroshima.35

Meanwhile, the parallel diplomatic efforts to revive the Washington negotiations made no headway. Foreign Minister Toyoda in September pressed for reconsideration by Washington of the proposed Roosevelt-Konoye conference, and the American Ambassador in Tokyo, Mr. Joseph C. Grew, strongly counselled this course in dispatches to the State Department.36 On 2 October, however, Secretary of State Cordell Hull, in a memorandum handed to Ambassador Nomura in Washington, reiterated that general withdrawal of Japanese troops from both China and Indochina remained a prerequisite for any JapaneseAmerican agreement.37

The Konoye Cabinet, unable to agree on the course that Japan should take in view of these

[39]

conditions, resigned on 16 October, and two days later War Minister General Hideki Tojo formed a new government. Despite the mid-October deadline, Premier Tojo pledged continued efforts for a diplomatic settlement.38 Then, on 5 November, a newly summoned Imperial conference revamped the 6 September "Outline Plan for the Execution of Empire Policies." Japan's resolution to accept war was reaffirmed; preparations therefor were to be completed by the end of November; however diplomatic negotiations were to be continued in the hope of effecting a compromise.39

Explaining the purport of the revised plan before the conference, Premier Tojo declared that eight Liaison conferences of the Government and Imperial General Headquarters, held between 23 October and 2 November, had reached the conclusion that war with the United States, Great Britain, and the Netherlands "was now unavoidable," and had unanimously decided to concentrate effort on war preparations, although still seeking to break the deadlock by diplomatic means.40

With the deadline for war now set at the end of November, speed was of the essence. The same day that the Imperial conference took place, the Navy Section, Imperial General Headquarters and Admiral Yamamoto, Commander-in-Chief of the Combined Fleet, issued orders for the fleet to prepare for the outbreak of war.41 The following day, 6 November, the Army Section, Imperial General Headquarters fixed the order of battle of the Southern Army and directed its commanding general to move his forces to the assembly areas and points of departure for the invasion of the "southern strategic areas."42

On the diplomatic front the urgency was no less great. On 6 November Ambassador Extraordinary Saburo Kurusu left by air for Washington to make the final effort for a peaceful solution.43 Without waiting for his arrival, Japan on 7 November transmitted its Proposal "A" through Ambassador Nomura, and when this was rejected, Proposal "B" for a temporary modus vivendi freezing war moves in the Pacific was presented by Ambassador

[40]

Kurusu on 20 November, three days after his arrival in Washington.44

It was at this crucial juncture that the Hull note of 26 November was delivered. Describing the reaction to the note in a statement made after the war, Admiral Shigetaro Shimada, at that time Navy Minister, said:

It was a stunning blow. It was my prayer that the United States would view whatever concessions we had made as a sincere effort to avoid war and would attempt to meet us half-way, thereby saving the whole situation. But here was a harsh reply from the United States Government, unyielding and unbending. It contained no recognition of the endeavors we had made toward concessions in the negotiations. There were no members of the Cabinet nor responsible officials of the General Staff who advocated acceptance of the Hull note. The view taken was that it was impossible to do so and that this communication was an ultimatum threatening the existence of our country. The general opinion was that acceptance of this note would be tantamount to the surrender of Japan.45

On 21 November, Imperial General Headquarters had ordered the Combined Fleet to move at the appropriate time to positions of readiness for the start of operations.46 The various naval task forces, though subject to recall in the event of a Japanese-American agreement, left for their designated theaters of operation toward the end of November.

On 29 November a Liaison conference of the Government and Imperial General Headquarters concluded that war must be launched. Instructions were sent to Japan's ambassadors in Germany and Italy to secure commitments whereby:

1. Germany and Italy would immediately declare war against the United States upon the outbreak of Japanese-American hostilities;

2. None of the three Powers would enter into a separate peace with the United States and Great Britain; and

3. The three Powers would not make peace with Great Britain alone.47

On 1 December an Imperial conference met to ratify finally the decision to fight. It was a moment of grave solemnity when, in the presence of the Emperor, Premier Tojo rose to announce:

In accordance with the decision reached at the imperial conference of 5 November, the Army and Navy have made full preparations for war, while the Government has continued to exert all possible effort to adjust diplomatic relations with the United States. However, the United States has not receded from its original demands. In addition, the United States, Great Britain, the Netherlands and China, in collusion, have demanded a one-sided compromise, adding new conditions such as unconditional withdrawal of our troops from China, repudiation of the Nanking Government and abrogation of the Tripartite Treaty with Germany and Italy.

If our country should yield, its prestige would be lost, and the China Incident could not be settled. More than this, the very existence of Japan would be imperilled. It is now clear that our country's claims cannot be realized through diplomatic negotiations.

Economic and military pressure by the United States, Great Britain, the Netherlands, and China is increasing. From the standpoint both of national strength and of military operations, the point has finally been reached

[41]

at which the nation can no longer allow matters to go on unchanged.

Under these conditions our country is obliged to take up arms against the United States, Great Britain and the Netherlands in order to solve the present situation and to preserve its national existence. Already the China Incident has continued for four years, and today we are plunging into an even greater war. It indeed fills us with trepidation that His Majesty has been caused such grave anxiety.

However, the strength of our country is many times greater than before the China Incident. Our internal unity is stronger, and the morale of the officers and men of the Army and Navy is higher. I am firmly convinced that, with the entire nation unified in determination to die for the country, we shall break through this national crisis.48

The Imperial conference then formally resolved "to open hostilities against the United States, Great Britain, and the Netherlands as a result of the failure of the Japanese-American negotiations and in accordance with the Outline Plan for the Execution of Empire Policies decided on 5 November."49

On the basis of this decision, Imperial General Headquarters on the same day ordered the Commanding General of the Southern Army to start invasion operations on 8 December,50 and on 2 December orders were issued to the Commander in Chief, Combined Fleet fixing the same date for the commencement of attacks by the Navy.51

On 6 December a Liaison conference of the Government and Imperial General Headquarters decided that Ambassador Nomura should be instructed to deliver Japan's final note ending the Japanese-American negotiations at 1:00 p.m. 7 December, Washington time, 30 minutes before the scheduled launching of the attack on Pearl Harbor.52

At 10:30 p.m. 7 December, with hostilities only five hours away, the United States Embassy in Tokyo received from the Washington State Department a triple-priority code dispatch instructing the Ambassador to transmit "at the earliest possible moment " a personal message from President Roosevelt to the Emperor urging efforts "to restore traditional amity and prevent further death and destruction in the world."53 This dispatch, though stamped by the Japanese Government Telegraph Office as having been received at 12:00 noon,54 was delivered with a 10 1/2-hour delay.55 After it had been decoded, Ambassador Grew personally handed the message to Foreign Minister Shigenori Togo at 12:30 a.m., 8 December, and the latter presented it to the Emperor in an extraordinary

[42]

audience at 3:00 a.m.56

Even as the Emperor read the President's plea to seek ways "of dispelling the dark clouds", the first wave of planes from the Japanese task force north of Oahu was nearing the target, and at precisely 3:25 a.m. the first bombs rained on Pearl Harbor.57 The machinery of war was irrevocably in motion.

In Tokyo, at 11:40 on that day, the solemn notes of the national anthem warned anxious radio listeners that an important announcement was impending. Then the voice of Premier Tojo, reading the Imperial Rescript declaring war,58 reached a stunned and silent nation. The broadcast ended with the strains of a martial song, "Umi Yukaba," its words grimly expressive of the fatalism with which the nation went to war.

Across the sea,

Corpses in the water;

Across the mountain,

Corpses heaped upon the field;

I shall die only for the Emperor,

I shall never look back.59

[43]

Go to: |

|

Return to the Table of Contents

Last updated 1 November 2006 |