CHAPTER IV

BASIC STRATEGY AND MILITARY ORGANIZATION

It was obvious to Japan's military strategists that the Pacific War would be a long one. The superior fighting potential of the United States made it improbable that Japan could inflict a crushing defeat on its adversary at the outset. The tremendous distances involved rendered a direct attack on the American mainland impracticable; finally; Japan not only had the United States to contend with, but Great Britain and the Netherlands as well.

Equally obvious was the certainty that possession of the natural resources for war would become a decisive factor. Japan did not have these raw materials within its own territory, and foreign sources of supply were blocked. The supply of liquid fuel, for example, was practically limited to the quantity on hand, and stockpiles were barely adequate for two years of armed conflict.

The first objective of Japan's strategy, therefore, was the conquest of the rich colonial areas in the South, whose vital resources added to those within the Japanese Empire, Manchuria, and Occupied China would provide a firm economic basis for waging an extended war.1

The fleet was assigned the vital task of blocking superior enemy naval power and supporting ground-force invasion operations.

In view of the handicap resulting from the pre-war ratio of 7.5 to 10 between the Japanese and American fleets, it was considered that the American fleet must be crippled by a surprise blow at the outbreak of war, giving Japan mastery of the sea long enough to attain its strategic objectives in the Western and Southwest Pacific. With American air and sea power temporarily crushed, and vital American and British bases, as well as the Netherlands Indies, in Japanese hands, it was estimated that Japan could carry on the war successfully for another two years, provided the fleet sustained no serious losses.

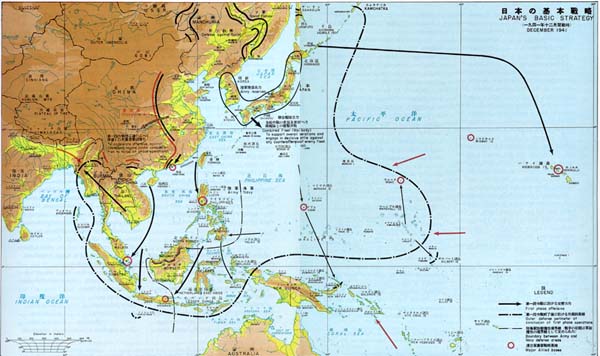

Once the initial objectives were taken, Japan would possess an outer defense perimeter extending from Burma through Sumatra, Java, Timor, Western New Guinea, the Caroline and Marshall Islands, and Wake. The vast sea areas within this perimeter, except for the Solomons-New Guinea-Philippines line, were generally favorable to the establishment of a strong strategic inner defense. (Plate No. 8) Within this zone, the Japanese fleet, especially its carrier forces, supplemented by land-based air strength, would be able to operate at great advantage, provided the United States and Britain were unable to build up their air strength sufficiently to swing the balance in their favor.

As regards land operations, it was estimated that the Army, if successful in its initial operations, would be able to secure and maintain its hold on the occupied areas. An anticipated

[44]

British counterattack against Burma could be successfully withstood by utilizing favorable terrain features and furnishing reinforcements when necessary. The southern areas, China, Manchuria, and Japan Proper would be strongly garrisoned, and as long as the destruction of Japanese shipping could be held within reasonable bounds,2 profitable exploitation of the occupied territories was deemed possible. With all the needed raw materials at its disposal, Japan's economic and military capacity to carry on the war could be guaranteed for about two years.

Beyond that date, however, a number of unpredictable factors made it impossible for Imperial General Headquarters to plan with certainty. The relative position in regard to armaments, fleet strength, and air power three years hence could not be accurately foretold. What changes would Japan's material power and morale undergo? Every shift in the world situation, especially in the European War, would have profound repercussions in the Pacific. These great imponderables rolled up like a stormy wave, making it impossible to see ahead beyond the first two years of war.

Aside from strategic problems, Japan's war planners devoted special attention to three principal elements which conditioned the nation's over-all fighting strength. These were manpower, raw materials, and transportation, especially shipping.

Paradoxically, as far as manpower was concerned, the very over-population which was one of the pressure factors behind Japanese expansionism now became a factor in Japan's favor.

Japan Proper, covering an area of only 381,000 square miles, supported in 1940 a population of 73,114,000.3 The population, for the past ten years, had been increasing at the rate of 800,000 to one million annually. With this reserve of manpower, immediate mobilization demands could be met easily, and the needs of industry could be filled throughout an extended war.

War-weariness had increased appreciably during the later years of the China Incident. But confronted by the new and graver challenge of a life-or-death struggle against the United States, Great Britain, and the Netherlands, the Japanese people could be expected to rise to the test. Japan's leaders entertained no doubt that traditional loyalty and obedience would keep the people's morale from breaking even under the strain of a long war.

As for raw materials, Japan expected to be practically self-sufficient in coal, iron, and industrial salts within the Japanese-Manchurian-Chinese bloc, if adequate marine transportation could be assured. Kyushu, Hokkaido, Sakhalin, and North China were the main sources of coal for general use. Coal for steel production came chiefly from Sakhalin, Manchuria, and North China. North and Central China could be counted on for iron ore, while industrial salts were available in Korea, Manchuria, North China, and Formosa.

The annual production of steel was approximately 5,000,000 tons. The overall steel plan for 1941 was as follows:

| Production goal: | 4,760,000 tons |

| Navy Allotment: | 950,000 tons |

| Army Allotment: | 900,000 tons |

| Ordinary Consumption: | 2,910,000 tons |

These estimates were revised in November

[45]

PLATE NO. 8

Japan's Basic Strategy, December 1941

[46-47]

1941 to conform to a decrease in production and an expected increase in Navy requirements in the event of war. The new figures were:

| Production goal: | 4,500,000 tons |

| Navy Allotment: | 1,100,000 tons |

| Army Allotment: | 790,000 tons |

| Ordinary Consumption: | 2,610,000 tons |

Of the 2,610,000 tons allotted for ordinary consumption, it was planned to allocate 300,000 tons to the shipbuilding industry on a priority basis, in order to achieve a ship construction goal of 600,000 tons annually.4 It was estimated that, if the Southern campaign succeeded, it would be possible to carry on a long war with a steel program of these proportions. The shortage of liquid fuel was Japan's Achilles heel. The combined output of natural and synthetic oil did not exceed 3,459,000 barrels annually. War needs must be drawn mainly from reserves, at least until the oilproducing territories in the south could be occupied, developed, and fully exploited.

Allowing for the possibility that the oil wells in the southern area might be totally destroyed before they fell into Japanese hands, the Government and Imperial General Headquarters developed a supply plan which would barely meet estimated war requirements:5

Supply: (in thousand barrels)

| Stock pile: | 52,836 |

| Domestic Production: | 1st year | 2nd year | 3rd year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crude Oil | 1,573 | 1,258 | 1,887 |

| Synthetic Oil | 1,887 | 2,516 | 3,145 |

| Total | 3,460 | 3,774 | 5,032 |

| Production in the southern areas: | 1st year | 2nd year | 3rd year |

| Borneo | 1,887 | 6,290 | 15,725 |

| Sumatra | - | 6,290 | 12,580 |

| Total | 1,887 | 12,580 | 28,305 |

Demand:

| 1st year | 2nd year | 3rd year | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Military | 23,902 | 22,644 | 21,072 |

| Non-military | 8,806 | 8,806 | 8,806 |

| Total | 32,708 | 31,450 | 29,878 |

Balance: (exclusive of minimum reserve of 9,435,000 bls)

| 1st year | 2nd year | 3rd year |

|---|---|---|

| 16,040 | 944 | 4,403 |

Included in Japan's liquid fuel reserves as of 1 December 1941 were 6,919,000 barrels of aviation gasoline. The production program called for 503,200 barrels during the first year, 2,075,700 barrels during the second year, and 3,396,600 during the third year of the war. Wartime requirements were computed at 4,500,000 to five million per year, and plans were drawn up on the basis of these figures. The margin of safety was so slight, however, that considerable difficulty was anticipated in the second and third years.6

To meet Japan's domestic requirements for staple food, 397 million bushels of rice must be available annually. The rice supply plan for 1942 called for domestic production of 298 million bushels, the balance of 99 million bushels to be made up by imports from Korea, Formosa, Thailand, and French Indo-China. Transports returning empty from the zone of operations would be utilized to make up any shortage of nonmilitary shipping. If, due to military operations, imports from Thailand and French Indochina fell short of the estimated 50 million bushels counted upon from the two countries combined, soy beans,

[48]

sweet potatoes and miscellaneous grains grown in the Homeland, Korea, Formosa and Manchuria would be used to make up the deficit.7

Although shortages of a few special materials like cobalt and high quality asbestos were anticipated, control of the southern supply areas and the speedy development of occupied China8 were expected to produce a steady supply of important materials such as bauxite, raw rubber, raw materials for special steels, metals, non-ferrous metals, leather, cotton, hemp, and oil. This plan, however, depended entirely upon the maintenance of adequate marine transportation, and Imperial General Headquarters realized fully that this factor would prove a decisive one in the Pacific War.

In November 1941, Japan's total shipping amounted to 6,720,000 gross tons, including motor sailboats over 100 tons. Of these, serviceable ships aggregated 5,980,000 gross tons, including 360,000 gross tons of oil tankers.9

It was estimated that the level of imports required by the "Materials Mobilization Plan of 1941" could be maintained during hostilities, provided a minimum of three million gross tons of shipping was reserved at all times for nonmilitary use. With this tonnage, approximately five million tons of materials could be transported monthly, even if wartime shipping efficiency dropped by 15 to 20 per cent. Actually, the monthly average of tonnage transported during the first half of 1941 corresponded to this estimate, but since military requirements continued to tie down 2,800,000 tons of shipping long after the Southern operations had entered a relatively inactive phase, the reservation of three million tons of ships for nonmilitary use became a difficult problem.

In view of the vital importance of shipping, Imperial General Headquarters had given careful consideration to probable war losses and replacement construction plans. The Navy estimated that losses would aggregate 800,000 gross tons during the first year, 600,000 the second year, and 700,000 the third year. Imperial General Headquarters, however, estimated that losses during the first year of the war would amount to between 800,000 and one million tons,10 and that subsequently losses would decline.11 On this basis, decision was made to build 1,800,000 gross tons of new ships over a three-year period, an average of 600,000 tons annually.12

Japan's private shipbuilding capacity at the start of war was approximately 700,000 gross

[49]

tons, limited by an engine building capacity sufficient to power only 600,000 tons. In order to achieve the required goal of 600,000 tons of new ships annually, the Government planned to allot a yearly ration of 300,000 tons of steel, plus copper and other essential metals, to the shipbuilding industry, to lower shipbuilding standards, to institute thorough-going Navy control of all stages of construction from raw materials to finished ships, and to take steps to assure an adequate labor supply.13

To maintain the level of shipping needed for nonmilitary use, the Army had to restrict the number of requisitioned ships to a minimum, regardless of the effect on military plans and operations. Imperial General Headquarters fixed the limits of requisitioned tonnage for Army and Navy use as follows:14

| Army: |

(Gross tons) |

|---|---|

| 1st to 4th month: | 2,100,000 |

| Fifth month: | 1,700,000 |

| Sixth month: | 1,650,000 |

| Seventh month: | 1,500,000 |

| Eighth month: | 1,000,000 |

| Navy: |

|

| Monthly: | 1,800,000 |

| (Including 270,000 tons of tankers) | |

In other words, the Army's needs in requisitioned ships would be at their peak during the first four months of the Southern operations and thereafter were expected to decrease gradually until a constant level of one million tons was reached. After September 1942, it was estimated that a total of 2,800,000 gross tons would satisfy the combined requirements of both Army and Navy.15 Shipping requirements were figured so closely that any upward revision in Army demands might upset the balance of the war program. It was therefore agreed that neither service could boost its shipping allotment without reference to the Liaison conference of the Government and Imperial General Headquarters.

The primary decision which Imperial General Headquarters was called upon to make in the development of Japan's war plans was the delimitation of the areas to be occupied by the military forces. Economic and strategic considerations were uppermost in shaping this decision.16

First, from the standpoint of military strategic necessity, the United States must be expelled from the Philippines17 and its island

[50]

bases at Guam and Wake captured, while Britain's important Far Eastern bastions at Singapore and Hong Kong must likewise be placed under Japan's control. These strategic positions were the key to the control of important areas. To protect Singapore, Burma must also be taken.

Second, in order to secure the economic resources required for the prosecution of a long war, Java, Sumatra, Borneo, the Celebes, and Malaya must be successively occupied.

Third, seizure with small military forces of important points in the Bismarck Archipelago, centering on Rabaul, was also decided upon in order to protect the important Japanese naval base of Truk, but no definite plan was made for the invasion of New Guinea.

The areas enumerated would give Japan a strong strategic position in conjunction with the existing Japanese island possessions from the Marshalls west through the Carolines and Marianas.

The Army and Navy General Staffs made a shrewd appraisal of the possible lines of action open to the Allied Powers. This estimate was as follows:18

1. The Allies would attempt to isolate Japan politically and economically. At the same time, they would step up aid to Chiang Kai-shek in order to hold as many of Japan's effective forces immobile on the Continent as possible.

2. The United States and Great Britain would try to delay Japan's penetration of the southern areas by reinforcing their own air and sea power in the Philippines-Singapore areas and by holding these strategic bases as long as possible. The main body of the United States fleet also might, depending upon the trend of the early operations, attempt a trans-Pacific thrust, presenting the possibility of a decisive sea battle. Allied air and sea forces would harass Japanese sea traffic with guerrilla tactics to interfere with lines of communication.

3. When their mobilization was finally completed, the Allies would attempt a large-scale counteroffensive with air, sea, and ground forces, preparatory to a decisive naval battle. The United States would probably launch its counteroffensive from the southern and middle Pacific, where there were good sites for air bases. An offensive mounted across the Northern Pacific seemed unlikely because of unfavorable weather conditions. Should an American offensive be launched early in Japan's southern campaign, the chances were that it would be from the Central Pacific.

4. In the event that the United States and Great Britain elected to avoid decisive battle early in the war, they would probably limit themselves for the time being to submarine and air attacks on Japanese supply lines. At the same time they would endeavor to secure their communication lines with Australia and India with a view to the eventual use of these territories as bases for the start of a counteroffensive.

5. In all likelihood, Great Britain would be forced to employ the bulk of its strength in Europe, and would play a minor role in the Pacific operations. However, it could not be predicted with certainty whether the United States would elect to throw its main strength first against Japan or against the Axis

[51]

Powers in Europe. Japanese strategists, after carefully weighing the possibilities, estimated that first priority would be given to Europe.

6. The United States and Great Britain, already counting Chiang Kai-shek as an ally, would undoubtedly attempt to bring the Soviets into the war.

With the decision to fight taken and the areas to be occupied defined, the next vital question facing Imperial General Headquarters was the selection of the most propitious moment for opening the hostilities.19

In a war to be waged with inferior forces against three enemy countries, it was deemed absolutely essential that Japan exploit to the fullest the advantage of choosing the moment to strike and seizing the initiative from the start of the operations. Were Japan to wait passively until war finally resulted from a step-by-step process of deterioration, Imperial Headquarters estimated that loss of the initial tactical advantage would make it impossible to attain the basic Japanese strategic objectives.

It was estimated that, if war were not started before March 1942, economic inferiority would be such as to preclude any hope of success.

In order to guard against the remote possibility of an attack by the Soviet Union while Japan would be heavily engaged in the south, it was considered advisable to start hostilities early enough so that the Southern operations would be near completion before the end of the winter, during which a Soviet attack from the north would be unlikely.

In view of the steady tightening of defensive arrangements among the ABCD Powers, particularly joint Anglo-American defense arrangements in the Malaya and Philippines areas, it was deemed advantageous to start hostilities at an early date.

Assuming that the fleet would take the "Great Circle" route to attack Pearl Harbor, navigational and weather conditions would be extremely unfavorable after January. Similarly, navigational conditions off Malaya would become unfavorable in January and February.

To facilitate air and landing operations, it was advisable to select a date during the last-quarter moon.

To achieve a successful surprise attack operations should begin on Saturday or Sunday.20 In accordance with the decisions taken by the Imperial conference of 6 September,21 the High Command first planned to launch hostilities early in November. Then, with the revision of these decisions by the 5 November Imperial conference,22 the anticipated opening of hostilities was postponed until early December. The final decision on the date of the attack was held in abeyance until the outcome of the Japanese-American negotiations became clear.

Following the Imperial conference of 1 December, which finally ratified the decision to fight, 8 December (Sunday, 7 December in Hawaii and the United States) was fixed by Imperial General Headquarters as the date for the start of the war.

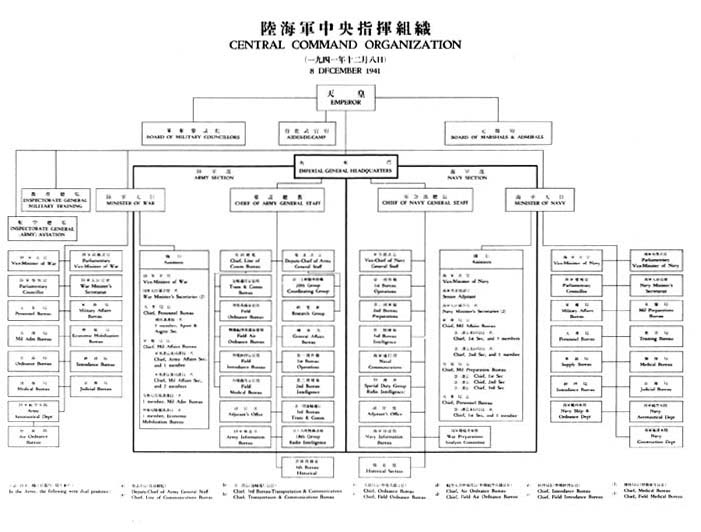

Central Command Organization23

With the outbreak of the China Incident

[52]

PLATE NO. 9

Central Command Organization

[53]

in 1937, Imperial General Headquarters was established as the central directing and coordinating organ of the Army and Navy High Commands. This body was divided into the Army and Navy Sections, in which the Chiefs of General Staff of both services and the chiefs and selected subordinates of the more important bureaus and sections of the War and Navy Ministries and the Army and Navy General Staffs were included. (Plate No. 9)

The Board of Military Councillors, a special body created in 1887, comprised of selected generals as well as the Board of Field Marshals and Fleet Admirals, composed of all field marshals and fleet admirals, were to advise the Emperor on matters of great military importance, and were also available to the services for consultation.

The Army and Navy Chiefs of General Staff were the Emperor's highest advisers in all matters involving the operational use of the fighting forces. Such matters did not pass through the Premier or the Cabinet. In other words, it was the special characteristic of the Japanese military High Command that it enjoyed complete independence from control by political organs of the Government in military matters.

To unify political and military strategy during war and promote closer coordination, the Government and High Command, in November 1937, established the Imperial General Headquarters-Government Liaison Conference.

Members ordinarily included the Premier, Ministers of War, Navy, and Foreign Affairs, and the Chiefs of the Army and Navy General Staffs. Decisions arrived at by this body were to be implemented by the responsible military or governmental agency.24

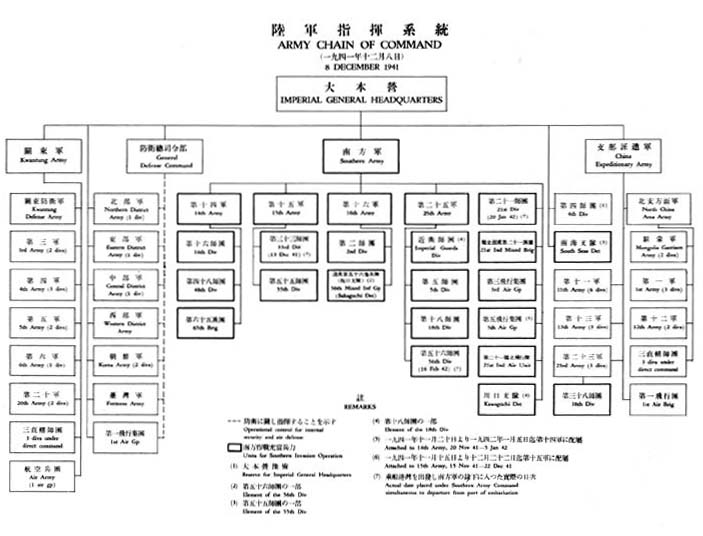

Strength And Organization Of Forces

Originally, Japan's basic policy was to maintain its controlling position in the Far East. Its armament, therefore, was developed mainly for use in its own and neighboring territories. The two potential enemies were the United States, a naval power on the east, and Russia, a military threat on the Continent to the west. For this reason, Japan could not subordinate one service to the other, and maintained an Army and Navy of equal strength.

Although both services made tremendous advances during the China Incident, a great disparity still existed between their strength and that of the United States Navy and the Soviet Army. Armament building and operational plans had been scaled to a conflict with one enemy before the Pacific War. Military operations against more than two nations had hitherto not been considered.

Japan had no independent Air force. Each service possessed its own air arm. After the outbreak of the China Incident in 1937, Japan began expanding its Air forces. Growing realization of the importance of air power as proved

[54]

PLATE NO. 10

Army Chain of Command

[55]

by active operations stimulated this expansion.25 The late start of the program, however, made it impossible to build up an air strength of planes of advanced design in the amount considered desirable before the beginning of the Pacific War. The Army Air forces had been operating with planes of short or medium range. Development of long range aircraft had not been emphasized.

At the time of its organization, the Japanese Army had been modeled first on the French and then on the Prussian Armies. From experience gained in the Russo-Japanese War, however, and profiting by the lessons of World War I, Japan adopted a unique system of organization, tactics, and training suitable to the requirements for operations in East Asia.

Following the outbreak of the Manchurian Incident, the potential enemy was obviously the Soviet Union. To oppose superior Soviet forces training emphasized offensive operations, individual courage, and proficiency in all branches of military science. Fire power and mechanization were not, however, stressed. During the six years' interval between the Manchurian and China Incidents, military personnel strength was enormously increased, and further augmentation between 1937 and 1941 brought the total strength up to 51 divisions at the outbreak of war.26 However, due to a lack of raw materials and limited budgets, little new equipment of improved design was issued. The Chinese forces, poorly trained and equipped, offered little stimulus to efficiency, and as a result Japanese staff officers grew slack as hostilities dragged on, and the whole standard of training deteriorated.

As the political situation vis-à-vis the

[56]

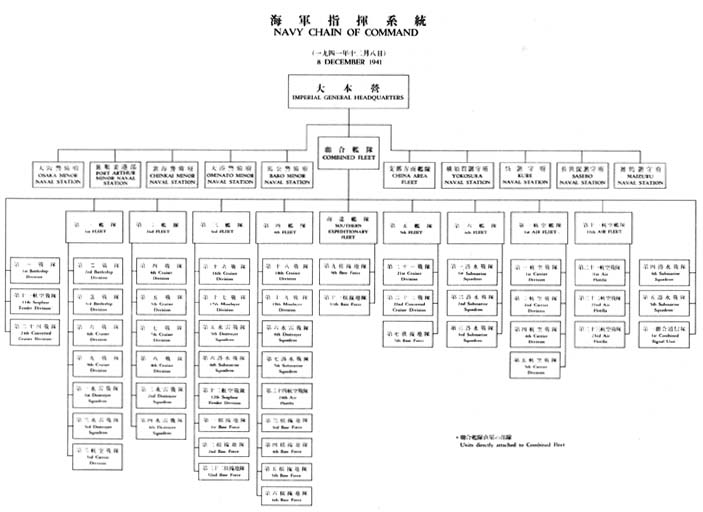

PLATE NO. 11

Navy Chain of Command

[57]

United States deteriorated, emphasis was shifted from preparation for war with the Soviets. This change was immediately reflected in Japanese combat tactics, and special training was begun for war against the United States and Great Britain.

The combat services were barely able to maintain sufficient armament to equip those forces already stationed overseas. Consequently, Japan Proper was short of air defense installations. There were practically no modern air defenses in the major cities, and air defense training never progressed beyond the point of arousing the people to become aware of passive precautionary measures.

The Navy, modeled on the British system at the time of its organization, had evolved a distinct Japanese form of its own following the Sino-Japanese War a decade later. Its primary mission until about 1935 had been to maintain command of the Western Pacific Ocean.

The Washington Naval Treaty limited the capital ship strength of the Japanese Navy to 60 per cent of that of the British and American fleets. Adequate defense of the country posed the problem of meeting a numerically superior naval force if the American Navy were concentrated. As a result, Japanese naval strategy, prior to World War II, was based on the concept of intercepting the American fleet while the latter was en route to attack in Far Eastern waters.

Along with this basic concept of strategy, the Japanese Navy developed its own special battle tactics which stressed the use of large high-speed submarines and night attacks by destroyers. Since naval thinking continued to be based largely on the idea of fleet engagements at sea, undue emphasis was laid upon first-line combat vessels, with relative disregard for the small-type auxiliaries needed for amphibious operations.

Lack of adequate funds, raw materials, and industrial power forced the Navy to curtail its construction plans considerably. The optimistic view that small-type vessels and amphibious equipment could easily be produced in wartime through accelerated shipbuilding proved absurd. The beginning of the war found the Japanese Navy with a strength of 68 per cent of that of the United States in first-line combat ships. However, in small-type auxiliaries, Japan had only 156 ships totaling 490,364 tons (38.5 per cent) as compared with 1,273,469 tons for the American Navy.

In December 1941 the Japanese Navy comprised 391 ships of all types, aggregating 1,466,177 tons. These included ten battleships (301,400 tons), ten aircraft carriers (152,970 tons), 38 cruisers (257,655 tons), 112 destroyers (165,868 tons), 65 submarines (97,900 tons), five seaplane tenders (58,050 tons), and five submarine tenders (33,445 tons). During the hostilities, new ship construction and conversion added to the fleet two 64,000-ton battleships (Yamato and Musashi), nine aircraft carriers, six escort carriers, six cruisers, 63 destroyers, 126 submarines, and 615 auxiliaries. The Yamato and Musashi, commissioned 16 December 1941 and 5 August 1942 respectively, were the world's largest and most heavily armed capital ships, carrying guns of 45-centimeter (17.7 inches) caliber.27

[58]

Go to: |

|

Return to the Table of Contents

Last updated 1 November 2006 |