CHAPTER VIII

DEFENSE OF PAPUA

With the sudden reversal of Japanese fortunes in New Guinea and the parallel failure of the second general offensive mounted by the Seventeenth Army Guadalcanal, Imperial General Headquarters for the first time began to assess the full gravity and implications of the situation which was developing on the southeast area front.1

It was evident that the Seventeenth Army, its major forces already expended in the futile attempts to retake the Solomons,2 could not cope with the added menace presented by General MacArthur's thrust against the Japanese right flank in Papua. To repulse these twin Allied drives and pave the way for ultimate resumption of the offensive toward Port Moresby, a drastic reorganization of command and an immediate reinforcement of fighting strength were imperative.

Therefore, on 16 November, Imperial General Headquarters ordered the activation of the Eighteenth Army to take over the conduct of operations in New Guinea, restricting the operational sphere of the Seventeenth Army exclusively to the Solomons. Both armies were simultaneously placed under a new theater command designated as the Eighth Area Army, and Lt. Gen. Hitoshi Imamura, Commanding General of the Sixteenth Army in Java, was ordered to Rabaul to assume command. These command dispositions were to become effective on 26 November.

Upon activation, the Eighth Area Army consisted of the Seventeenth Army, the newly activated Eighteenth Army, the 6th Division, 1st Independent Mixed Brigade, and 12th Air Brigade. Elements of the 5th Division were also assigned on 20 November. On 27 November, the Army's 6th Air Division3 commanded

[171]

by Lt. Gen. Giichi Itahana was activated and placed under the Commander-in-Chief, Eighth Area Army, to be used in support of both Seventeenth and Eighteenth Army operations.

To command the new Eighteenth Army in charge of New Guinea operations, Imperial General Headquarters appointed Lt. Gen. Ilatazo Adachi, then chief of staff of the North China Area Army. At the date of its activation, the Eighteenth Army's combat forces comprised only the remnants of the South Seas Detachment, the 41st Infantry Regiment, the 15th Independent Engineers Regiment and some small units, all badly battered in the Owen Stanleys campaign. On 20 November, however, elements of the 65th Brigade4 in the Philippines were transferred to Eighteenth Army by Imperial General Headquarters order. This was followed by an Eighth Area Army order on 26 November, placing the major portion of the 21st Independent Mixed Brigade,5 as well as one infantry battalion and one mountain artillery battery of the 38th Division,6 under Eighteenth Army operational control.

Parallel with this regrouping and replenishment of forces, Imperial General Headquarters on 18 November issued an operational directive to the Commanders-in-Chief of the Eighth Area Army and the Combined Fleet, clarifying future objectives on the southeast area front. The directive continued to give priority to the recapture of the Solomons, but at the same time it called for a strengthening of Japanese bases in New Guinea with the ultimate objective of resuming the offensive toward Port Moresby and sweeping the Allies from Papua. Essential points of the directive were as follows:

1. The Army and Navy will cooperate in hastily reinforcing and equipping air bases in the vicinity of the Solomon Islands for employment in subsequent operations, and will devote special attention to strengthening air defenses in this sector. Army forces on Guadalcanal will immediately secure key positions in preparation for offensive operations, while recovering their strength. The Navy, during this period, will use every means at its disposal to check enemy reinforcements to the Solomons and will cooperate with the Army in curbing enemy air activity. The Army and Navy will intensify air operations as they extend their air bases and, when enemy air strength has been neutralized, will seize the opportunity to transport reinforcements to Guadalcanal for the Army's offensive.

2. After these preparations have been completed, the Army, in cooperation with the Navy, will recapture the airfield on Guadalcanal and annihilate the enemy forces on that island. At the earliest opportunity, Tulagi and other key positions in the Solomons will also be occupied.

3. During the operations in the Solomons, the Army and Navy will secure strong operational bases at Lae, Salamaua and Buna, will strengthen air operations by extending and fitting out air bases, and will prepare for future operations. The Army, in cooperation with the Navy, will occupy Madang, Wewak and other strategic areas. Preparations for future operations in the New Guinea area will embrace every feasible plan for the capture of Port Moresby, Rabi, and the Louisiade Archipelago.7

Reaching Rabaul on 22 November after a hasty air journey from Tokyo,8 Lt. Gen. Ima-

[172]

mura swiftly established his headquarters and on 26 November, the date set for the entry into effect of the new command arrangements, issued his first order setting forth the operational objectives of the Eighth Area Army in accordance with the Imperial General Headquarters directive. The order stated:

1. The operational objectives of the Eighth Area Army, in conjunction with the Navy, are to recapture the Solomon Islands and to prepare for future operations in New Guinea by holding intact key strategic positions in that area. For this purpose, elements of the Army will secure strategic points in eastern New Guinea and carry out preparations for later operations, while the main strength of the Army will first secure key positions on Guadalcanal and prepare for an offensive to destroy the enemy forces on that island. The main forces of the Combined Fleet will cooperate in these operations.

2. The Seventeenth Army will expedite preparations for the forthcoming offensive on Guadalcanal, which will commence about the middle of January.

3. The Eighteenth Army, in cooperation with the Navy, will secure key positions in the vicinity of Buna and prepare for future operations. Orders in regard to these preparations will be issued separately.9

Lt. Gen. Adachi, arriving at Rabaul on 25 November to assume command of the Eighteenth Army, immediately established his headquarters and, on 26 November, issued his first message to Eighteenth Army troops:

The eastern New Guinea and Solomon Islands areas are vitally important not only for the immediate protection of the strategic southern areas which we occupied at the beginning of the Greater East Asia War, but also for the security and defense of Japan Proper. Therefore, it is necessary for us to secure these areas as the first line of defense. In addition, these areas are most strategically located, and absolute control of them is necessary to cut lines of communication between the United States and Australia and thus disrupt the enemy's plans. For this very reason, the United States and Great Britain, taking advantage of their abundant resources, have been conducting a full-scale counteroffensive for the past four months in order to recapture these bases. . . .

In view of the over-all war situation, the first objective of the Army is to secure a strong position in eastern New Guinea. However, this is only in preparation for further advances in the future. . . I call upon you men of high fighting spirit to display the tradition of the glorious Imperial Army on the battlefield. Do your utmost to fulfill the trust and meet the desires of His Majesty the Emperor.10

The Eighteenth Army command, now ready to function, turned its immediate attention to the situation at Buna. In the interim, while preparations to effect the new command arrangements were being completed, emergency measures to reinforce the imperilled Buna garrison had temporarily checked the Allied onslaught, but the outlook remained dark and unpromising.

When Allied troops suddenly launched their attack from the coastal sector immediately south of Buna on 19 November, they caught the Japanese forces almost totally unprepared to meet an assault from this new direction. One cause of this unpreparedness was the fact that the swift Australian advance from the Owen Stanleys had forced the South Seas Detachment to throw its full strength into an effort to stop that advance. Another was the failure of Japa-

[173]

nese intelligence to discover the gradual and carefully concealed infiltration of enemy troops up the east coast of Papua.

As early as September, Seventeenth Army headquarters at Rabaul had foreseen the possibility of an Allied amphibious or airborne attack in the Buna area and had consequently ordered the South Seas Detachment, then at the farthest point of its advance on Port Moresby, to readjust its front northward and divert part of its strength to secure Buna. Two battalions of the 41st Infantry had accordingly taken up positions in the Buna-Gona-Giruwa area early in October, but, as the Australians pushed the South Seas Detachment back into the Kokoda area, these units were recalled to the front for the final abortive effort to hold the Australians.11 The entire Buna-Gona area was thus left temporarily unguarded except by approximately 2,500 Army and Navy combat effectives and some 1,200 labor personnel.12

The failure of Japanese intelligence to discover until too late the presence of Allied forces in the coastal area below Cape Endaiadere permitted the enemy to achieve a large measure of tactical surprise.13 The Army and Navy commands in Rabaul obtained their first warning of an impending attack on Buna from the south on 16 November, when a lookout post on the southeast of Buna reported "what appeared to be three masts." This report was immediately interpreted as indicating initial Allied landing operations, and Eleventh Air Fleet headquarters in Rabaul ordered naval aircraft to carry out a strike on the enemy ships the same day in order to check the landings. Thirty-eight planes went out on the sortie, and five of the six ships were reported sunk or set afire. Nevertheless, it was estimated that approximately 1,000 enemy troops had succeeded in getting ashore.14

Aware of the serious weakness of the Japanese forces then available to meet an attack on Buna from the south, Seventeenth Army subordinate staff officers in Rabaul had meanwhile made hasty arrangements with the local Navy command for the immediate transport of reinforcements to Buna.15 The situation was so obviously urgent that the Navy promptly divert

[174]

ed several destroyers from Guadalcanal supply operations, and in three separate transport runs carried out on 17, 18 and 21 November, a total of 2,300 troops, including one battalion of the 229th Infantry Regiment of the 38th Division, was successfully landed at Basabua anchorage, near Gona.16 It was hoped that these reinforcements would be sufficient to assure the holding of the Buna-Gona area, at least temporarily.

Topographically, this area was not favorable to the establishment of a strong defensive perimeter. The coastal plain between Cape Endaiadere and Gona was flat, traversed by belts of jungle swampland which broke up the outer Japanese defense positions into separate compartments and hindered the maneuvering of troops. Transverse movement was limited to the few passable native trails which ran along the coast.

Shortages of personnel and materials had also hampered the construction of defensive fortifications. The strongest of these were improvised cover trenches reinforced with cocopalm logs and oil drums filled with earth. After rains these trenches turned to quagmire, forcing the troops to fight waist deep in water.

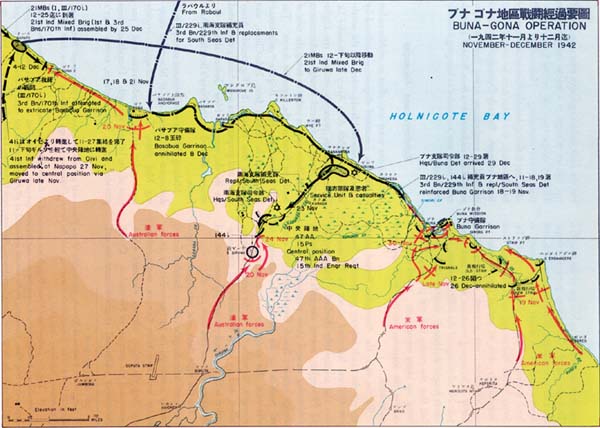

The Japanese defense positions were concentrated principally in three strategic sectors: (1) Gona-Basabua, protecting the anchorage generally used for troop and supply debarkation; (2) Sanananda-Giruwa, constituting the core of the defensive positions; and (3) Buna-Cape Endaiadere, guarding the left flank and the Buna airstrip.17 The Sanananda-Giruwa defenses were laid out in depth, with the rear positions near the coast, a so-called "central position" about two miles inland on the Sanananda-Soputa track, and an outer position about one mile farther inland, at a point identified by the Japanese as South Giruwa, where an east-west trail crossed the Sanananda-Soputa track. In the Buna sector, strong defensive positions in depth were set up southeast of the airstrip, below Cape Endaiadere, and south of Buna village, with secondary positions at Buna Mission and in the headquarters area northwest of the airstrip. (Plate No. 43)

As of 16 November, when the Allied threat to Buna from the south first became known, none of these sectors was strongly manned. In the Buna sector, most immediately threatened, were naval landing troops and an Army antiaircraft battery totalling about 1,000.18 However, by 19 November, when the enemy attack began, these forces had been bolstered by the first reinforcements rushed from Rabaul, i. e., the 3d Battalion (reinf.) of the 229th Infantry (1,000 men) and 500 replacements for the 144th Infantry, South Seas Detachment. Col. Shigenori Yamamoto, who arrived with these reinforcements to take over command of the 144th Infantry, was instead placed in command of all Army forces in the Buna sector, while the naval forces remained under command of Capt. Yoshitatsu Yasuda.19

In the Giruwa sector, Col. Yosuke Yoko

[175]

yama, 15th Independent Engineers Commander and ranking officer in the absence of Maj. Gen. Horii,20 had meanwhile assumed the direction of battle preparations. By 17 November the disorganized remnants of the 144th Infantry, totalling less than 1,000 officers and men, had found their way back from the Oivi battle and were ordered to halt their retreat to reinforce the weakly-manned outer defense position at Southern Giruwa. In the central position to the north were combat elements aggregating about 1,000.21 By 23 November, the latter had been reinforced by 800 fresh South Seas Detachment replacements shipped from Rabaul, and by 29 November most of the surviving strength of the 41st Infantry had moved forward from the Napopo area, northwest of Gona, to further strengthen the central position.22 Almost no combat forces were stationed in the rear area around Sanananda and Giruwa.23

Most weakly defended of the three principal sectors was the Gona-Basabua area on the right flank. This was held only by about 700 service and labor unit personnel, principally engaged in road construction, at the time of the initial Allied attack.24

The enemy assault on the Japanese defenses in the Buna-Gona area began with almost simultaneous thrusts at four points on the outer perimeter both east and west of the Giruwa River. The main weight of the attack appeared to be directed against the left flank in the Buna sector, where one enemy force attacked the Japanese positions between Senimi Creek and the sea on 19 November, followed within a few days by a separate drive against the defenses directly south of Buna guarding the approach along the Buna-Soputa track. To the west of the Giruwa River, the Australian forces, which had closed in from the Oivi area after defeating the South Seas Detachment, simultaneously attacked the Japanese right flank anchor at Gona and the 144th Infantry positions at South Giruwa. (Plate No. 43)

Despite a shortage of heavy weapons,25 the combined Army and Navy force defending the Buna sector successfully repulsed the initial enemy attacks directed at both the perimeter east of Senimi Creek and the strong positions

[176]

one mile south of Buna Village in the so-called Triangle area.26 The naval garrison troops, thus far not engaged in battle, were fresh and commanded by an officer specially trained in land warfare.27 The 3d Battalion, 229th Infantry, which had moved up to the Buna front immediately after its arrival from Rabaul on 17 November, was a crack unit, eager for battle. Occupying positions which took every possible advantage of the difficult terrain, these forces fought stubbornly, further aided by the fact that the enemy had not yet been able to bring up heavy equipment. Until early December the situation on this front remained stalemated.

To the west, the Australian frontal attack against the 144th Infantry positions at Southern Giruwa, launched about 20 November, was also successfully checked. However, on 24 November, enemy elements succeeded in infiltrating around these positions to drive a wedge between South Giruwa and the central position to the north. An attempt to eliminate this wedge by a force of battalion strength, dispatched from the central position, failed, and by early December all communication with the hard-pressed Japanese force in Southern Giruwa had been cut off.

On the right flank, the heterogeneous Japanese force defending the Gona-Basabua sector, hastily reinforced on 19 November by an infantry unit sent from Giruwa, succeeded in repelling Australian advance elements which penetrated the area on 20 November. On 26 November additional reinforcements arrived, but the weak defending forces were soon bottled up, and an attempt at a rescue made by 41st Infantry troops from the central Giruwa position proved unavailing. Hemmed in on all sides and suffering heavily from intense artillery bombardment, the Gona force nevertheless continued to resist. By early December it appeared doomed to annihilation unless fresh attempts to send in reinforcements from Rabaul, then already under way, succeeded in bringing immediate relief.

Upon the entry into effect on 26 November of the new command dispositions ordered by Imperial General Headquarters for the southeast area, Eighth Area Army Commander Lt. Gen. Imamura promptly ordered the Eighteenth Army to dispatch strong reinforcements to the Buna area in order to swing the tide of battle in favor of the Japanese forces. The 21st Independent Mixed Brigade,28 only recently arrived in Rabaul from Indo-China, was assigned this mission by Eighteenth Army order, and preparations were hastily completed for its shipment to New Guinea aboard destroyers allotted by the Navy's Southeast Area Force.

Making the first reinforcement attempt, four destroyers left Rabaul on 28 November carrying Maj. Gen. Tsuyuo Yamagata, brigade commander, with the headquarters and a portion of the brigade strength. Despite air cover provided by six Navy fighters, enemy B-17's

[177]

PLATE NO. 43

Buna-Gona Operation, November-December 1942

[178]

attacked the convoy north of Dampier Strait on the morning of the 29th, and two of the destroyers sustained damage, forcing the convoy to turn back to Rabaul.29

On 30 November a second attempt was launched. The convoy of four destroyers, again carrying the brigade headquarters, the 3d Battalion of the 170th Infantry Regiment, and signal units, totalling in all 720 officers and men, this time took a course skirting south of New Britain, with a reinforced air escort of 13 planes. Despite sporadic enemy air attacks, the convoy safely reached the anchorage near Gona on the evening of 1 December.

At this point, however, Allied planes launched an attack of such intensity that it was impossible for the troops to board landing craft, and the destroyers were obliged to move on to the mouth of the Kumusi River, 18 miles northwest of Gona. Here, with enemy planes still dropping flares, 425 of the troops succeeded in transferring to landing craft, but in the movement to the shore they became dispersed and landed at widely-separated points between the Kumusi River mouth and Gona. The remaining 295 troops could not be landed and returned with the destroyers to Rabaul.30

It was 6 December before Maj. Gen. Yamagata was able to reassemble his scattered forces and move them into a concentration area about two miles west of Gona. From this point he ordered his troops forward in an attempt to break the Australian envelopment of Gona, but the enemy lines held, and the fighting entered a stalemate. With succor so near and yet unable to reach them, the Japanese forces in Gona were finally overwhelmed on 8 December, only a handful of survivors escaping by sea or through the jungle to the Giruwa area.31

Meanwhile, a third reinforcement convoy of five destroyers had set out from Rabaul on 7 December, carrying additional elements of the 21st Independent Mixed Brigade. This time, however, vigilant enemy planes spotted the ships after they had barely emerged from the St. George Channel, a few hours out of Rabaul. Under severe attack, the convoy was forced to put back into port immediately.

With the Japanese defenses in the Buna sector also beginning to crack under intensified enemy pressure, it was now more imperative than ever to move the remaining strength of the 21st Brigade to the battle area without delay. Hence, on 12 December, a fourth and final reinforcement attempt by destroyer was begun. Five ships with an escort of nine fighters left Rabaul on that date, taking a roundabout course to the north of the Admiralty Islands in an attempt at deception. Despite this maneuver, the convoy underwent heavy bombing as it neared its destination.32

With the Gona-Basabua anchorage already under enemy control, the mouth of the Kumusi had been fixed as the landing point. However, already behind schedule due to the intense air attacks, the destroyers put in at the mouth of the Mambare River, 40 miles short of the goal, and disembarked the troops before dawn on 14 December. The 1st Battalion of the 170th Infantry, one company of the 3d Battalion, the regimental gun company and 25th Field Machine Gun Company, aggregating 870 troops, were successfully put ashore.33 Between 18 and 25 December, these troops moved southward along the coast by small craft and

[179]

joined the 21st Brigade units already in the Napapo area west of Gona.

Owing to steadily increasing Allied air domination of the sea approaches to the Papuan coast, no further attempts to dispatch reinforcements to the Buna area by destroyer were undertaken. Only two of the four attempts made between 28 November and 14 December had been halfway successful, and the effort had cost damage to four destroyers of the dwindling naval forces in the southeast area.34

The stalemate which had prevailed on the Buna sector front since the initial enemy attacks in late November finally ended on 5 December, when powerful offensives were launched by the American forces against both the Senimi Creek-Cape Endaiadere position and the Buna Village area. (Plate No. 43) In the former sector, the enemy again failed to breach the strong outer perimeter,35 but, on the right flank, enemy troops which had gradually infiltrated past the Japanese strong points in the Triangle area toward Buna Village succeeded in driving a wedge to the sea between the village and Buna Mission, at the same time capturing some of the positions on the southern perimeter of the village. By 14 December, the small defending force of Army troops and naval construction personnel in Buna Village had been overcome.36

On 18 December the enemy again struck with renewed vigor at the Triangle area on the right flank, and the Senimi Creek-Cape Endaiadere line on the left. The troops in the Triangle area, resisting fierce bombardment by enemy mortars and artillery, again held their positions. However, on the left flank, a powerful assault, spearheaded for the first time by tanks, broke through the Japanese defenses in the coastal sector and drove a salient northward past Cape Endaiadere.37

The Japanese naval unit defending the Senimi Creek bridge-crossing southeast of the airstrip was now forced to pull back to the airstrip defenses, where it prepared to make a suicide stand.38 Enemy tanks were soon brought across the creek to support the ground troops' assault, and the Japanese defenses slowly gave way in heavy fighting. By 26 December the last naval antiaircraft battery emplaced near the central portion of the strip was wiped out after firing its last remaining rounds of ammunition against oncoming enemy tanks.39 Three days later, on the right flank, the Japanese positions in the Triangle area were finally overcome, and enemy elements, in another drive to the sea, cut off the Buna garrison headquarters, northwest of the airstrip, from Buna Mission.

In view of the increasingly critical situation, the Eighteenth Army Commander at Rabaul had already dispatched urgent orders to Maj. Gen. Yamagata on 26 December, directing

[180]

him to move the Zest Brigade troops, still held up west of Gona, to Giruwa by sea and from there launch an attack toward Buna to relieve the Japanese forces cut off in that sector.40 It seemed improbable, however, that Buna itself could be saved. Hence, on 28 December, the Army and Navy commands at Rabaul ordered the withdrawal of all forces from the Buna sector to join in the defense of Sanananda-Giruwa.

Between 27 and 29 December, Maj. Gen. Yamagata with a relief unit of one battalion (reinf.)41 successfully moved from Napapo to Giruwa by small landing craft. After setting up his headquarters at Giruwa, Maj. Gen. Yamagata placed the relief detachment under command of the 41st Infantry regimental commander, Col. Yazawa, and on 31 December ordered it to move up for an attack on the enemy left flank above Buna.42

Even before the relief unit had started, however, Maj. Gen. Yamagata's headquarters received a report from the Buna front to the effect that, on 1 January, enemy troops, spearheaded by six tanks, had penetrated into the isolated headquarters area northwest of the airstrip. There, the Army and Navy commanders of the Buna garrison forces, Col. Yamamoto and Capt. Yasuda, were reported leading the last handful of survivors of the headquarters personnel in a suicide stand.43 (Plate No. 44)

The Yazawa relief unit, still hoping to rescue the Japanese troops holding out in the Buna Mission area, started its movement from Giruwa on 2 January. Upon reaching Siwori Creek on the night of the 4th, the unit was held up by a bloody encounter with about 300 enemy troops, but it pushed on across the creek to a point about one mile west of Buna, where by 8 January it had received a total of a few hundred Army and Navy personnel, the sole survivors of the force which had so ably defended the Buna sector. The relief unit then fell back under constant enemy harassment to the Konombi Creek line, where it occupied positions for the defense of Giruwa.44

While the rescue operation was in progress, the last Japanese positions in the Buna Mission area had fallen to the enemy. The battle for Buna was at an end.

With the final collapse of Japanese resistance in the Buna sector, the full weight of the Allied assault immediately shifted to the front west of the Giruwa River, where the Japanese still clung tenaciously to a five-mile strip of coast extending from Konombi Creek, above Buna, to Garara, west of Cape Killerton. The nerve-center of the Japanese defenses was situated in the vicinity of Sanananda Point and Giruwa, on the coast, protected on the inland side by the already isolated outpost at Southern Giruwa and the so-called central position between Southern Giruwa and the coast.

[181]

PLATE NO. 44

Fate of Yasuda Force on New Guinea Front

[182]

The condition of the Japanese forces holding this area was now desperate in the extreme. The flow of supplies from Rabaul had been stopped with the exception of small amounts of provisions and ammunition brought to the mouth of the Mambare River by submarine and thence moved to Giruwa by small landing craft under cover of night. By the end of the first week in January, all food supplies had been exhausted, and the troops were eating grass and other jungle vegetation. Deaths from tropical diseases exceeded battle casualties. Enemy artillery fire and air bombardment had razed the protective jungle covering around the Japanese bunkers and trenches, and rains flooded these positions as fast as they could be drained.45

Enemy air supremacy over the battle area was virtually complete. During the first phase of the Buna fighting, Japanese naval air units based on New Britain had carried out a series of effective attacks against the enemy advance air base at Dobodura and against Allied supply shipping, but by mid-December control of the air had definitely passed to the Allies. The arrival in Rabaul at about this time of the 6th Air Division, the first Army air unit to be dispatched to the southeast area, came too late to exert much effect.46 Enemy observation craft flew unhindered over the Japanese positions, increasing the effectiveness of artillery fire to a point of deadly accuracy.

By late December, Imperial General Headquarters in Tokyo had reluctantly recognized the inevitable pattern of defeat that confronted the Japanese forces both in eastern Papua and on Guadalcanal. Therefore on 23 December, Imperial General Headquarters modified its 18 November directive and placed the decision of withdrawal from the Buna area to the discretion of the local commander, dependent upon the local situation. However, Imperial General Headquarters placed such great significance on the evacuation of Guadalcanal that it was not until the Imperial conference of 31 December that its final decision was reached. On 4 January, therefore, an order was dispatched to Lt. Gen. Imamura, Commander of the Eighth Area Army, and to Admiral Yamamoto, Commander-in-Chief of the Combined Fleet,47 directing the first major withdrawal of Japanese troops since the start of the Pacific War. The order stated:

1. In the Solomons area, the fight to recapture Guadalcanal will be discontinued, and the Army will evacuate its forces immediately. Henceforth, the Army will secure the northern Solomons, including New Georgia and Santa Isabel, and the Bismarck Archipelago.

[183]

2. In the New Guinea area, the Army will immediately strengthen its bases of operation at Lae, Salamaua, Madam, and Wewak. The strategic area north of the Owen Stanley Range will be occupied, and thereafter preparations will be made for operations against Port Moresby. The forces in the Buna area will withdraw to the vicinity of Salamaua, as required by the situation, and will secure strategic positions there.48

Studying the situation at Rabaul, Lt. Gen. Imamura decided to delay the issuance of implementing orders for two reasons. First, he thought that the situation was not so grave as to warrant an immediate evacuation. Second, it was essential to delay relinquishment of the Giruwa area until reinforcements, then preparing to leave Rabaul, had reached Lae-Salamaua and strengthened that area against possible Allied attack.

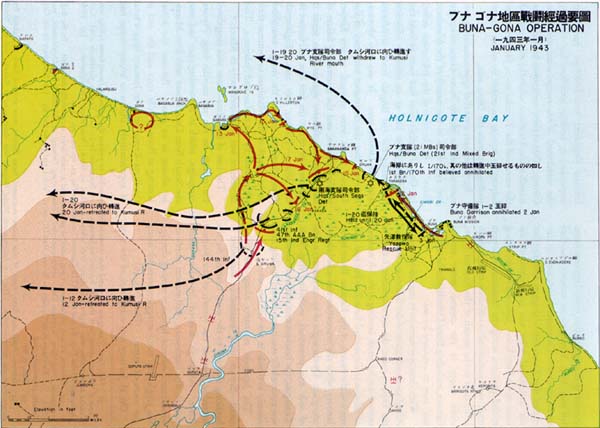

Meanwhile, however, the final disintegration of the Japanese forces on the Giruwa front was already beginning. On 12 January, three days after its last food supplies had been exhausted, the isolated Japanese force in Southern Giruwa, unable to communicate with rear headquarters, launched an independent break for freedom through the enemy lines. Heading southwest into the jungle, the troops found their way to the Kumusi River, and thence retreated northward. A small number of survivors reached the Japanese positions at the mouth of the Kumusi in the latter part of January.

Finding the resistance before them ended, the Australians quickly moved up the SoputaSanananda track and joined the enemy force already blocking the track to the north in an assault on the Japanese central positions. (Plate No. 45) At the same time, elements swung around to the west of these positions in a flanking movement, one force advancing to the coast to capture the Japanese right flank outpost at Garara on 13 January, and another cutting in from the west to split the central positions from South Seas Detachment headquarters near Sanananda Point. The force which took Garara immediately drove eastward along the coast, capturing Wye Point on 15 January.

While the Australians closed in from the south and west, the American forces pushing up the coast from Buna launched an attack on the Japanese forces, left flank along Konombi Creek on 12 January. Here, the remaining strength of the 1st Battalion, 170th Infantry, put up a determined fight which held up the enemy advance until about 20 January.49

On 13 January, following the landing of 51st Division reinforcements at Lae, Lt. Gen. Imamura ordered Eighteenth Army to begin the evacuation of the Japanese forces from Giruwa. In compliance with this order, Lt. Gen. Adachi, Eighteenth Army Commander, dispatched an immediate order to Maj. Gen. Yamagata, commanding all forces in the Giruwa area, directing that the evacuation be carried out as follows:

1. The Buna Detachment Commander will abandon his present positions and divert his troops as follows:

a. Diversion of the main force will commence about 25 January and end about 29 January.

b. The main force of the 21st Independent Mixed Brigade will assemble in the Mambare area, and one element of the brigade in the Zaka-Morobe area.

c. Main strength of other units will be dispatched to Lae, and the remainder to Salamaua.50

Although 25 January was fixed as the starting date of the general evacuation, the rapid closing of the Allied pincers on Giruwa and the

[184]

increasing disorganization of the Japanese forces led Maj. Gen. Yamagata to advance the date to 20 January.51 Communications were so disrupted that it was only with great difficulty that the withdrawal order was transmitted to the units in the front lines. Japanese forces holding inland positions along the Sanananda-Soputa track were instructed to withdraw independently by land to the mouth of the Kumusi River, while troops in the coastal sector around Giruwa, including Buna Detachment headquarters, were to evacuate by sea.

With destroyer movement impossible due to Allied air domination of the Solomons Sea and the Papuan coast, the sea evacuation had to be carried out by small landing craft. A number of these was dispatched from Lae but had only reached the mouth of the Kumusi River by 20 January, when the evacuation was scheduled to take place. On the night of 19-20 January a total of only 250 personnel, including Maj. Gen. Yamagata, the headquarters staff and casualties, was successfully evacuated aboard landing craft already available in the Giruwa area.52

The Japanese remnants along the Sanananda-Soputa track meanwhile succeeded in breaking through to the west, heading for the assembly point at the mouth of the Kumusi River. Although favored by slow enemy pursuit, the battleworn, half-starved survivors experienced extreme hardship moving through the jungle, and many stragglers were left along the route of retreat. (Plate No. 46)

On 18 January two companies of the 102d Infantry Regiment, 51st Division, had been dispatched by landing craft from Lae to cover the withdrawal of the troops evacuated from Giruwa. One of these companies landed at the mouth of the Mambare, while the other reached the mouth of the Kumusi on 24 January, there helping to repulse an attack by enemy troops pushing up from the Gona area.

By 7 February a total of approximately 3,400 survivors of the bloody Buna-Gona campaign had assembled at the mouth of the Mambare River.53 At the time of the evacuation order, Lt. Gen. Adachi's plan had been to hold the Mambare River line as an advance offensive base, using the 21st Brigade forces withdrawn from the Giruwa area. It was now obvious, however, that the decimated remnants of the Giruwa forces were unequal to any further combat mission, and the intervening failure of the Japanese offensive against Wau made it necessary to retract the first line still farther to the Mubo-Nassau Bay area. Eighteenth Army therefore ordered the troops assembled at the mouth of the Mambare to continue their withdrawal by sea to Lae and Salamaua. This movement was completed early in March.54

The loss of the Buna-Gona area rang down the curtain on the six months long Papuan campaign, which in September 1942 had seen the South Seas Detachment with Port Moresby almost in its grasp. Between the initial landing at Buna in July 1942 and the end of the Buna-Gona battle in January 1943, a total of approximately 18,000 to 20,000 troops had

[185]

PLATE NO. 45

Buna-Gona Operation, January 1943

[186]

PLATE NO. 46

Withdrawal from Buna and Wau to Salamaua-Lae, January-March 1943

[187]

been thrown into the Owen Stanleys drive and the subsequent effort to stop the Allied counteroffensive. About 15,000 had been lost in the whole campaign.55 Of this number, the bitter fighting in the Buna-Gona area alone had cost between 7,000 and 8,000 lives, of which over 4,000 were killed in battle and the remainder succumbed to disease.56 Despite this costly effort, Papua had been lost, and with it the strategic area north of the Owen Stanley Range, the key to Port Moresby.

Strengthening of Bases in New Guinea

While the Japanese forces in Papua were still carrying on their stubborn but hopeless fight to retain possession of the vital Buna-Gona area, hasty action was being taken by the Eighth Area Army and the Combined Fleet to reinforce the general Japanese strategic position in New Guinea through the seizure of new bases on the northeast New Guinea coast and on both sides of the Vitiaz Strait.

By its directive of 18 November 1942, Imperial General Headquarters had recognized the necessity of building up the New Guinea flank against General MacArthur's advance by establishing bases in the vacuum areas to the rear of the vulnerable Japanese advance outposts at Lae-Salamaua and Buna. The Eighth Area Army had therefore been ordered, as one of its initial missions, to effect the early occupation of Madang, Wewak and other strategic points.57

By early December, when plans and preparations for execution of this mission were under way, the increasing probability that the BunaGona area could not be held made it doubly essential to effect an immediate strengthening of Japanese defenses to the north. The Eighth Area Army and Southeast Area Fleet commands therefore decided to supplement the occupation of Madang and Wewak with the simultaneous seizure of Finschhafen, on the Huon Peninsula, and Tuluvu, on western New Britain, both of which were considered necessary to safeguard Japanese control of the Dampier and Vitiaz Straits and thus strengthen the defense of Lae-Salamaua.

Although the initial characteristic of these plans was defensive, they were also designed to lay the groundwork for the ultimate resumption of the offensive by the Japanese forces in New Guinea, after the American assault on the Solomons had been successfully parried. Emphasis was placed upon the development of operational air bases at Tuluvu, Wewak and Madang, and Wewak was to be transformed into a big rear supply base for the support of future operations.

On 12 December, Lt. Gen. Imamura, Eighth Area Army Commander, assigned the mission of occupying Madang, Wewak and Tuluvu to the Eighteenth Army, placing under its command for this purpose three newly-arrived infantry battalions of the 5th Division58 and the 31st Road Construction Unit. Under final Eighteenth Army plans, two infantry battalions were allotted to the occupation of Madang, one to Wewak, and the 31st Road Construction Unit (less two companies) to Tuluvu.59 The

[188]

occupation of Finschhafen, by local Army-Navy agreement, was assigned to a small force of special naval landing troops.60

Naval convoys carrying the Madang and Wewak occupation forces sailed from Rabaul on 16 December, while a surface support force including one aircraft carrier headed south from Truk to cover the operation. The Wewak force reached its destination without mishap on 18 December, but the Madang force underwent both air and submarine attack off the New Guinea coast, the escort flagship Tenryu sinking as a result of torpedo hits and one converted cruiser carrying troops receiving bomb damage. Despite these attacks, the convoy continued to Madang and unloaded its troops early on 19 December.61

While the Madang and Wewak operations were in progress, the Tuluvu occupation force completed its movement from Rabaul aboard a single destroyer on 17 December.62 The Finschhafen force left Kavieng, New Ireland, on two destroyers the following day, executing a successful landing on 19 December.63 Work began immediately at the occupied points to prepare airstrips for operational use and set up base installations.

Immediately upon completion of these new occupation moves, the Eighth Area Army turned its energy to the urgent problem of strengthening the defenses of the Lae-Salamaua area, now seriously jeopardized as a result of the deteriorating situation on the Buna-Gona front to the south. This area was tenuously held by a naval garrison force of 1,300 men, which had never been able to do more than secure the immediate vicinities of Lae and Salamaua against enemy guerrilla forces. At Wau, 30 miles southwest of Salamaua, the Allied forces possessed a strategically located base of operations, with an airfield capable of accommodating at least light planes.

On 21 December, Lt. Gen. Imamura ordered the Eighteenth Army to strengthen its strategic position for future operations "by securing important areas to the west of Lae and Salamaua."64 A further order on 28 December directed the immediate dispatch of troops to the Lae-Salamaua area, and on 29 December Lt. Gen. Adachi, Eighteenth Army Commander, ordered the Okabe Detachment, composed of one reinforced infantry regiment of the 51st Division,65 to proceed from Rabaul to Lae. The missions assigned to the detachment were specified as follows:

1. The detachment, in cooperation with the Navy, will land in the Lae area, and a portion of its strength will secure that area.

2. The main strength will immediately advance to Wau, and elements to Salamaua, in order to secure those areas and establish lines of communication.

3. The detachment will thereafter be responsible for the land defense of the Lae-Salamaua area, and

[189]

it will also carry out preparations for offensive operations against the Buna area.66

Five transports carrying the Okabe Detachment sailed from Rabaul on 5 January with a surface escort of five destroyers. On 6 January, enemy B-17's spotted the convoy as it proceeded through the Bismarck Sea, and the transport Nichiryu Maru, carrying most of the 3d Battalion, 102d Infantry Regiment, caught fire and sank after receiving a direct bomb hit.67 Though badly battered, the remainder of the convoy proceeded on to Lae, where it arrived on 7 January and began discharging troops and supplies under continuous Allied air attack.

Despite efforts to break up the enemy air assault by fighters which had moved forward from Rabaul on 7 January to operate from Lae, bombing of the anchorage became so severe on the 8th that unloading had to be discontinued and those ships which were still navigable sent back to Rabaul.68 With the exception of the troops aboard the Nichiryu Maru, all personnel of the Okabe Detachment had been put ashore, but only half of the supplies had been safely unloaded.69

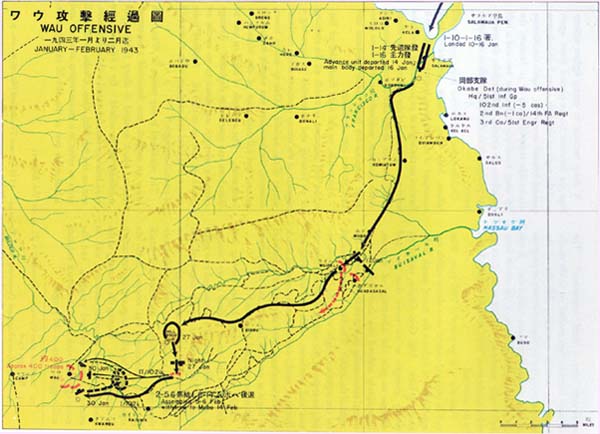

Notwithstanding this initial setback, Maj. Gen. Okabe decided to proceed according to plan and immediately ordered the detachment to prepare to move against Wau. The general plan of attack called for the main strength of the detachment to move by landing craft to Salamaua, and from there advance on Wau via Mubo, Waipali, and the mountain track through Biaru. (Plate No. 47) This route was chosen in preference to the easier track leading from Mubo along the Buisaval River Valley, which offered little cover against enemy air attack.70

Amphibious movement of the detachment from Lae to Salamaua was completed between 10 and 16 January. Two days before its completion, on 14 January, the advance echelon of the attack force, composed of the 1st Battalion, 102d Infantry (reinf.), had already moved out of Salamaua on the first leg of its advance toward Wau. Maj. Gen. Okabe, with detachment headquarters and the main body of the attack force, followed on 16 January. Total effective strength of the force as it started out from Salamaua was approximately 3,000 officers and men.71

First enemy ground reaction developed as the advance echelon moved south from Mubo on 16-17 January. In the vicinity of Waipali, a small enemy force of about 40 men, equipped with mortars, offered light resistance, retiring

[190]

PLATE NO. 47

Wau Offensive, January-February 1943

[191]

southward after a brief encounter.72 The advance echelon then pushed on to the southwest, the steadily increasing difficulty of the mountainous terrain slowing its rate of progress at times to less than three miles a day. It was 27 January before all units of the attack force had finally assembled at Hill 5500, about six miles northeast of Wau, whence the attack was to be mounted.

From the vantage point of Hill 5500, Wau and its adjacent airfield were clearly visible and appeared to be within a few hours' march of the assembly area. Maj. Gen. Okabe, estimating enemy strength at no more than 400 and anxious to gain the advantage of surprise, immediately ordered the 102d Infantry regimental commander to launch the attack on the night of the 27th.73 The final attack plan called for the regiment's right wing (2d Battalion, reinf.) to strike at the airfield defenses from the east and northeast, while the left wing (1st Battalion, reinf.) was to launch the main attack from the southeast. Both attacks were scheduled to begin at 0100, 28 January, and all objectives were to be occupied by dawn.74

Right and left wings began moving into position for the attack at dusk on 27 January. A small enemy patrol encountered two miles south of Hill 5500 was rapidly dispersed, but progress through the unknown jungle terrain in darkness was so slow that, even by dawn, neither force had reached its scheduled attack position. Movement was stopped until late afternoon of the 28th to guard against attack by enemy aircraft. During the evening, as the advance resumed, a further encounter with an enemy elements delayed progress, and the morning of the 29th found the attack columns still bogged down in the jungle.

A sharp increase in enemy fighter activity kept the Japanese troops pinned down again until the night of the 29th, when both columns pressed forward once more. Again the advance was so slow that, by dawn of 30 January, the left wing force was still about two and a half miles from the airfield. Meanwhile, the enemy was profiting from the delay to fly in reinforcements.

Deciding that any further delay might spell failure, Maj. Gen. Okabe personally took command of the left wing force and ordered it forward on the night of 30 January to attack the southwest perimeter of the airstrip. The attack failed, however, as the assault units, moving up in the darkness, suddenly ran into fierce automatic weapons fire from enemy positions and were thrown into confusion.

Meanwhile, on the right flank, the 2d Battalion had launched an attack on the morning of 30 January and succeeded in capturing a segment of the enemy positions at the northeast corner of the airfield. Due to severe losses, however, the battalion was unable to hold its ground and fell back east of the airfield to reorganize. The strength of both 1st and 2d Battalions was now badly depleted. Average company strength was down to 50 in the 1st Battalion, and 40 in the 2d. Artillery units were at one-third and engineer units at one-half of normal strength.75

The reinforced enemy troops in Wau, with heavy air support, now launched a counteroffensive, which resulted in sharp fighting just southeast of the airfield. By 4 February, the 102d Infantry was threatened with encirclement, and on the 6th Maj. Gen. Okabe ordered all units to retire to a concentration area two and a half miles east of the airfield to reorganize.

[192]

On the same day, ten Japanese fighter planes sent from New Britain attacked the Wau airfield in an effort to curb enemy air activity, but the effort could not be maintained and consequently failed to improve the situation appreciably.76

On 12 February, Maj. Gen. Okabe ordered a further withdrawal to a provisions storage dump about a mile and a half to the rear. The troops, on short rations since an early stage of the advance from Salamaua, had exhausted their food supplies during the protracted campaign and were now existing on wild potatoes (taros) and a small amount of captured enemy provisions.

With its hopes of taking Wau completely shattered, the Okabe Detachment on 13 February received orders from the Eighteenth Army command at Rabaul to abandon the attempt and withdraw its forces to Mubo and the Nassau Bay area. The withdrawal began on the 14th and was completed in ten days without enemy pursuit. Out of 3,000 troops which had set out from Salamaua for the Wau offensive, only 2,200 survivors returned to Mubo. More than 70 per cent of these, moreover, were suffering from malaria, malnutrition, dysentery and other diseases, and were unfit for combat duty.77

The failure of the attempt to take Wau had serious consequences for the Japanese situation in New Guinea. Not only had the major strength of the Okabe Detachment been expended in futile fighting, but the Eighteenth Army's plans to strengthen the flank defenses of the Lae-Salamaua area were seriously unhinged.

While the Eighteenth Army in New Guinea was being forced to pull back its front line to the Lae-Salamaua area following the loss of Papua and the failure of the Wau offensive, a withdrawal on a much larger scale and of considerably greater difficulty was being carried out from Guadalcanal, in the Solomons, under the Imperial General Headquarters directive of 4 January.78

Following the collapse of the second general offensive on Guadalcanal in late October 1942, the Seventeenth Army and Southeast Area Naval Force had continued efforts to move in reinforcements for a new offensive planned for January.79 Initial elements of the 38th Division were successfully transported by destroyers from the Shortland Islands in early November, but the main reinforcement effort in mid-November met disaster when Allied planes sank or set afire all but four of eleven transports en route from Bougainville.80 In a series of accompanying surface actions between 11 and 15 November, moreover, the Japanese naval forces lost two battleships, one cruiser and three destroyers,

[193]

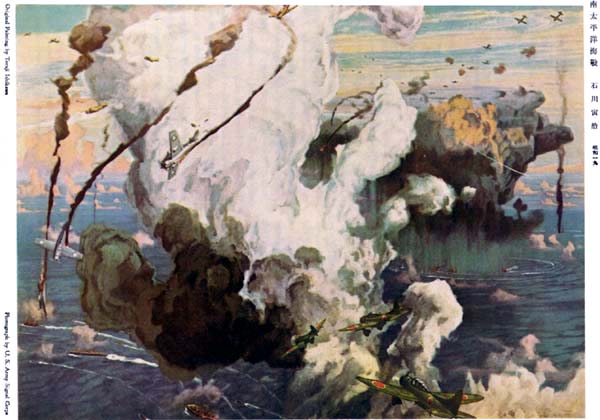

PLATE NO. 48

Sea Battle in South Pacific

[194]

PLATE NO. 49

Suicide Unit Bidding Farewell to Commanding General Sano

[195]

with three cruisers and three destroyers heavily damaged.81

With aerial supremacy over the southern Solomons already in Allied hands and the combat effectiveness of the naval forces reduced by ship losses, Imperial General Headquarters reluctantly decided that the fight to retake Guadalcanal must be abandoned and all Japanese forces withdrawn.82 The directive of 4 January accordingly ordered the Eighth Area Army and Combined Fleet to make immediate preparations for the withdrawal.

Evacuation of approximately 18,000 troops still exchanging fire with the enemy from the immediate vicinity of an enemy airfield was a formidable task which required careful planning and preparation. Land-based naval air units on New Britain were weakened by extended combat. Carrier aircraft strength, seriously depleted in the Santa Cruz sea battle, had not yet been replenished, and the withdrawal operation involved risking virtually all the remaining destroyer forces of the Combined Fleet.

Despite these handicaps, the Eighth Area Army and Southeast Area Fleet jointly worked out plans which called for the employment of all available aircraft in a sustained offensive designed to neutralize enemy air and sea strength long enough to permit seaborne evacuation operations. Following a preliminary series of night raids, mass daylight attacks were to begin from about 28 January. The ground forces were to begin gradual withdrawal to embarkation points from 25 or 26 January, and the evacuation itself was to be effected by destroyers in three separate runs on the nights of 31 January, 3 and 6 February.83 The plans called for participation of 212 Navy and 100 Army aircraft, predominantly fighters, while 22 destroyers and several submarines were made available by the Navy.84

Night raids by small numbers of Navy aircraft on Henderson Field began on 21 January and continued almost without interruption until the end of the month. The first mass daylight attack was staged on 25 January by 91 Navy planes, followed on the 27th by Army fighters of the 6th Air Division. On 29 January naval aircraft reported inflicting heavy damage on an enemy naval force, including cruisers and battleships, between San Cristobal and Rennell Islands.85

Due to the appearance of the enemy naval force, the evacuation schedule was retarded one day, the first evacuation taking place on the night of 1-2 February. Eighteen destroyers drew in at Kaminbo, on the northwestern tip of Guadalcanal, and successfully took aboard 4,940 troops who were put ashore the following day in the Shortland Islands. One destroyer sank upon hitting an enemy mine near Kaminbo, while another was damaged by air attack and had to withdraw.

On 2 February 56 Navy planes carried out another heavy strike on Henderson Field to keep enemy air power neutralized. The second evacuation followed on the night of the 4th, when 17 destroyers took aboard and carried to the Shortland Islands 3,902 troops. In this operation one destroyer was hit by an enemy bomb and forced out of action.

In the final evacuation on 7 February, 1,730 troops were removed from the island, bringing

[196]

the total number of troops evacuated to 10,572.86 Including damage sustained by one destroyer in this operation, total naval losses for the whole evacuation amounted to only one destroyer sunk and three damaged.87

With the termination of the fight for Guadalcanal, the Solomons area entered a period of temporary quiescence, during which both sides prepared for the next phase of battle. The Japanese front line was withdrawn to New Georgia and Santa Isabel Island. These were only lightly garrisoned by about three infantry battalions and a few antiaircraft units, and airfields were still in process of construction. To remedy this situation, the Southeast Area Fleet, in the latter part of February, directed the Eighth Fleet to move two units of the 8th Combined Special Naval Landing Force to Munda as a preliminary reinforcement measure.88 In April these were augmented by elements of two infantry regiments (13th Inf. Refit., 6th Division, and 229th Inf. Regt., 38th Division), and on 3 May all Army forces in the New Georgia area were combined in a newlyactivated Southeast Detachment under the operational command of the Eighth Fleet.89

Ground defense of the northern Solomons was left in the hands of the Seventeenth Army. Army headquarters was established on Bougainville, and the 6th Division, already moved to Bougainville in January, was newly placed under Seventeenth Army command. The battered units evacuated from Guadalcanal were gradually moved back to Rabaul, where the 38th Division was reorganized for defense of New Britain. The 2d Division and 35th Infantry Brigade were transferred to other theaters.90

Various factors were responsible for the parallel setbacks suffered by the Japanese forces in Papua and the Solomons, but the most important of these was the gradual loss of air supremacy over the areas of battle to the Allies.

At the time of the American invasion of the Solomons in mid-summer of 1942, the outcome of the battle for aerial supremacy still hovered in the balance. Japanese naval aircraft based at Rabaul, chiefly Zero fighters and land-based medium bombers, were still able to operate with a certain degree of effectiveness over Papua and the Solomons, where the Allies did not yet possess superiority in numbers of aircraft.

However, Allied plane strength in the southeast area soon began to increase at a rate with which the Japanese could not keep pace. Numerical superiority passed to the hands of the enemy, and in addition, his ability swiftly to construct and expand forward bases increased the effectiveness of his air forces. Similar Japanese efforts to develop forward air bases, though they made some progress, were retarded by shortages of manpower and equipment, with the result that sorties were still being flown chiefly from Rabaul in the fall of 1942. The distances involved seriously curtailed the effectiveness of the air effort over Papua and the

[197]

Solomons.91

In the Solomons, it was primarily the enemy's expanding carrier-borne air forces which captured control over the Guadalcanal battlefield and thwarted Japanese reinforcement attempts. In the battle for Papua, a major factor was the long-range B-17 bomber. From the autumn of 1942, these powerful craft intensified their attacks on Japanese troop and supply shipping in the Solomon and Bismarck seas, and by December were carrying out regular night raids on Rabaul itself.

In an attempt to elude B-17 attack, Japanese vessels on transport and supply missions began moving as much as possible at night or in bad weather, but enemy radar equipment made even such movement risky. Japanese destroyers, despite their speed and maneuverability, often could not elude the extremely accurate bombing of the B-17's, and escort fighters offered little protection.92 The Zero fighter, armed with two 20-millimeter automatic cannon, was then a relatively powerful craft, but repeated engagements indicated that two or three Zeros still were no sure match for a single B-17.93 Attempts to develop new fighter types capable of combatting the B-17's were only partially successful.94

The gradual loss of the air campaign over the Solomons and eastern New Guinea underlined the urgent necessity of infusing fresh air strength into the southeast area. This in turn demanded accelerated mass production of aircraft and training of air crews in the homeland. During the bitter battle for Guadalcanal, the Navy had poured in a large portion of its available land-based air strength, but this had been so rapidly expended that the Japanese air potential in the southeast area actually showed little or no increase.95 The Army's 6th Air Division, though activated in November to reinforce the naval air forces in the southeast area, did not begin operating from Rabaul until late in December, when both the Guadalcanal and Buna campaigns were already virtually lost.

To alleviate one of the major handicaps which had reduced the effectiveness of the Japanese Air forces in these campaigns, the Army and Navy commands at Rabaul began early in 1943 to concentrate special effort on the construction of new air bases and the reinforcement of air defenses in northeast New Guinea and western New Britain. At Wewak, Madang and Tuluvu, lack of airfield construction personnel and equipment neces-

[198]

PLATE NO. 50

Troops at Work, Southern Area

[199]

sitated imposing this task on infantry troops equipped only with picks and shovels.

As of the beginning of March 1943, Japanese first-line air strength in the southeast area aggregated approximately 200 Navy and 100 Army planes.96 These were operating mainly from three airfields in the Rabaul area, from Buin on southern Bougainville, and from Kavieng on New Ireland. There were two Japanese airstrips at Kavieng, four in the Solomons, three in northeast New Guinea, and two (besides the Rabaul strips) on New Britain.

At this same period, Japanese intelligence estimated enemy air strength in the Guadalcanal area at about 230 first-line planes, chiefly of small types, and about 200, including a large proportion of heavy bombers, operating in Papua.97 Allied aircraft were believed operating from five or six airstrips on Guadalcanal, two at Milne Bay, four or five in the Buna area, and six at Port Moresby.

Although the Imperial General Headquarters decision of 4 January to abandon Guadalcanal did not formally state that, henceforth, New Guinea would be considered the decisive battlefront, it had, in fact, already begun to shift the major Army effort to New Guinea.

On 23 December, a week prior to the Imperial conference decision to evacuate Guadalcanal, Imperial General Headquarters had ordered the transfer of two fresh divisions-the 20th from Korea and the 41st from North China-to the southeast area front, principally for use in the Solomons.98 Before either division had sailed, however, the evacuation decision intervened, and plans were immediately altered to move both divisions to New Guinea under Eighteenth Army command.99

In addition to the 10th and 41st Divisions, Imperial General Headquarters between January and April 1943 ordered the dispatch to New Guinea of large numbers of service-troop reinforcements, principally antiaircraft, engineer, road construction, shipping and land transport units.100 The 6th Air Division, already in the Rabaul area, was to deploy part of its strength to New Guinea and was to be strengthened by the dispatch of additional planes and air crews, together with airfield construction units, base personnel and large amounts of materiel. The total number of troops to be moved to New Guinea under the reinforcement program amounted to about 100,000.101

On the basis of this projected augmentation of forces, the Eighteenth Army drew up new

[200]

operational plans which called for immediate strengthening of the Lae-Salamaua area against anticipated Allied attack, and also for long-range measures to develop rear bases and transport routes in preparation for future offensive operations. The principal steps envisaged were:102

1. Dispatch of the main strength of the 51st Division from Rabaul to the Lae-Salamaua area as soon as possible, with the 10th Division to go to Madang, and the 41st Division to Wewak.

2. After its arrival at Madang, the 20th Division to move toward Lae, constructing a supply road via the Finisterre Range, the Ramu and Markham River valleys. The 41st Division to advance from Wewak to Madang at a later date.

3. Special emphasis to be placed on building up troop strength and materiel in the Lae-Salamaua area, rapid construction of an intermediate base at Madang, and development of land and sea communications linking Lae-Salamaua with Madang and rear supply bases at Wewak and in the Palau Islands.

For Japan's heavily taxed naval and shipping resources, the movement from Japan Proper, the Continent and other distant areas of the large volume of troops and materiel newly allotted to New Guinea was a big undertaking and could not be accomplished overnight. However, by the end of February 1943, the major strength of the 20th and 41st Divisions had been safely transported to Wewak,103 and remaining elements of the 20th Division and various supporting troops were moved to the Hansa area during the succeeding months of March, April and May. After March, Allied air attacks on Japanese ships unloading or at anchor, especially night bombing raids, interfered increasingly with transport operations.

Although the movement of the bulk of Eighteenth Army's newly-assigned strength to rear areas in New Guinea was thus successfully accomplished, efforts to carry out the more urgently required reinforcement of the LaeSalamaua area proved extremely costly. Eighth Area Army and Southeast Area Fleet headquarters fully realized the risk involved in attempting to ship troops directly to Lae in view of Allied air preponderance over the Dampier Strait area. Nevertheless, it was finally decided that this risk must be taken since an alternate plan of shipment to Madang and subsequent movement by land or by landing craft along the coast to Lae would run the greater risk of failing to get the troops to Lae in time to meet expected Allied attack.

Preparations were therefore completed in the latter part of February for the immediate shipment from Rabaul of the main strength of the 51st Division,104 elements of which (Okabe Detachment) were already in the Lae-Salamaua area. Lt. Gen. Adachi, Eighteenth Army Commander, decided to accompany the movement in order to establish the Army command post at Lae. To lessen the danger of enemy air interference, plans were made to carry out preliminary neutralization strikes against Allied

[201]

air bases in the Buna and Port Moresby areas, but these were prevented by adverse weather. Despite this upset in plans, the Army and Navy commands at Rabaul decided that movement of the 51st Division could not be postponed, and consequently the convoy of eight troops transports, with a surface escort of eight destroyers, sailed from Rabaul on the night of 28 February.105 About 100 Army and Navy planes were assigned to provide air escort.

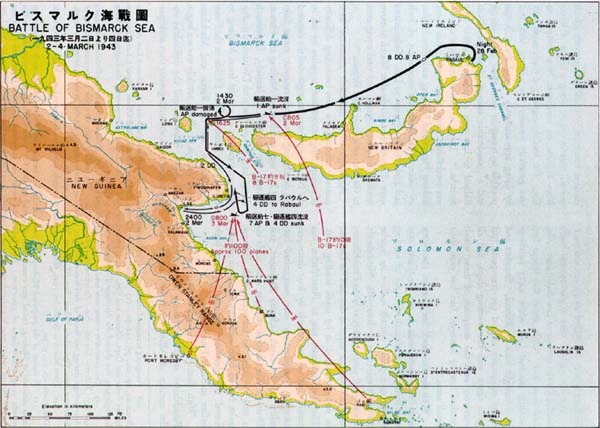

Moving at its best speed of seven knots,106 the convoy was passing through the Bismarck Sea north of Cape Hollman on 1 March, when it was spotted by large enemy planes. (Plate No. 51) These did not attack but observed the convoy's movements, and at 0805 the following day about ten B-17's launched the first strike on the slow-moving ships. The Kyokusei Maru, with about 1,500 troops aboard, was set afire by a direct hit and had to be abandoned, later sinking at a point northeast of Cape Gloucester. About 800 troops were safely transferred aboard the destroyers, Yukikaze (carrying the 51st Division Commander, Lt. Gen. Hidemitsu Nakano) and Asagumo, which proceeded toward Lae ahead of the convoy. After safely disembarking the survivors at Lae, these destroyers sped back and rejoined the convoy early on 3 March.

Meanwhile, the rest of the convoy, after changing its course for a brief period during the afternoon of 2 March, again headed for Lae, receiving a further attack during the evening, in which the naval transport Nojima sustained slight damage. The convoy negotiated the Vitiaz Strait during the night and had reached a point 30 nautical miles southeast of Cape Cretin, on the Huon Peninsula, when about 40 B-17's and 60 other enemy aircraft attacked at 0800 on 3 March. The convoy fighter escort numbered 26 planes at the start of the attack and was later reinforced by 14 additional planes.

The Japanese fighters, anticipating a highaltitude attack, were flying at considerable height and were taken by surprise when the enemy bombers swept in from all directions to deliver their attacks low over the water. Enemy medium bombers employed a new skip-bombing technique of deadly effectiveness. The Japanese ships, thinking that they were under torpedo-plane attack, attempted evasive action without success, and after about an hour of severe bombing, all seven remaining transports were afire and sinking, as well as three escort destroyers. One of these destroyers, the Tokitsukaze, had aboard the Eighteenth Army commander and part of his staff.107

Four of the five remaining destroyers, after picking up as many survivors as possible before afternoon of the 3rd, withdrew northward in order to escape further attack. In this movement, contact was lost with the fifth destroyer, which presumably lagged behind and was sunk by enemy bombs. As soon as darkness fell, three of the four destroyers which had retired northward returned to the scene of battle and continued rescue operations until just before dawn of the 4th, when they headed back to Rabaul and Kavieng. The Bismarck Sea battle, as serious a defeat for the Japanese as it was a

[202]

PLATE NO. 51

Battle of Bismarck Sea, 2-4 March 1943

[203]

brilliant victory for Allied air power, was over. Out of slightly over 6,900 troops badly needed for the defense of Lae-Salamaua, 3,664 had been lost. Only about 800 troops had actually reached Lae, while 2,427 survivors were brought back to Rabaul. Supplies and heavy equipment aboard the transports had gone down with the burning ships, and all survivors with the exception of those which reached Lae by destroyer had lost even their small arms.108

With the Bismarck Sea disaster, the Army and Navy commands in the southeast area were forced to relinquish all hope of sending troops or supplies directly to Lae by regular transport vessels or by destroyers. Henceforth, ships could proceed only as far as Finschhafen, whence troops or supplies destined for Lae had to move overland or by small landing craft. The first transport run to Finschhafen was carried out on 20 March by four destroyers carrying approximately one reorganized battalion of the 115th Infantry Regiment, 51st Division. Two further attempts were made on 2 and 10 April to transport 66th Infantry units, but on both occasions enemy air attacks forced the destroyer convoys to turn back before reaching Finschhafen.

With destroyer movement even as far as Finschhafen rapidly becoming perilous under the menace of Allied air power, resort was made to transport by small landing craft, which moved only at night along a chain of bases from Tuluvu, on northwest New Britain, to Lae. The loading capacity of these small craft was generally between five and ten tons, but by using approximately 200 of them, it was possible to transport more than 3,000 troops and a considerable amount of supplies from Rabaul to Lae over a period of about four months.109 Later, a similar transport system was established along the New Guinea coast linking Hansa and Madang with Finschhafen in order to facilitate the movement of 20th and 41st Division troops to Lae. Submarines were also used extensively after March to move medical supplies, rations, and vital equipment to the Lae area from New Britain.110

Although these makeshift measures were partially effective, the ever increasing difficulty of transporting troops and supplies by sea in the New Guinea area strengthened the demand for developing overland transport routes linking Lae with rear bases at Madang and Hansa. Already at the end of January, Eighteenth Army had ordered the 20th Division to undertake construction of a road from Madang to Lae via the Mintjim-Faria Divide in the Finisterre Range, and the Ramu and Markham River Valleys.111 Work actually was not begun until April, however, and the difficulties encountered were so much greater than anticipat

[204]

Ed that by July the road had been completed only as far as Mablugu, 40 miles from Madang. Allied aircraft also hampered the project by bombing the supply base at Erima and bridges to the south.

The virtually complete destruction in the Battle of the Bismarck Sea of the 51st Division forces counted upon to hold the Lae-Salamaua area against anticipated Allied attack shocked Imperial General Headquarters into realization of the extremely tenuous situation on the Japanese right flank in the southeast area. This served as a decisive reason for a vital revision of joint Army-Navy operational policy, whereby first priority was definitely shifted from the Solomons area to New Guinea.

The terms of the revised policy were stipulated in a new Army-Navy Central Agreement on Southeast Area Operations, issued by Imperial General Headquarters as an operational directive to the Eighth Area Army and Combined Fleet on 25 March 1943. This directive stated:112

1. Operational Objective: To establish a strong strategic position by occupying and securing key points in the southeast area.

2. Operational Plan:

a. Army and Navy forces, acting in complete coordination, will concentrate their main effort on operations in New Guinea and will secure operational bases in that area. At the same time, defenses will be strengthened in the Solomon Islands and the Bismarck Archipelago, key points will be secured, and future enemy attacks will be crushed at the opportune time.

b. New Guinea Operations:

(1) Strategic points in the Lae-Salamaua area will be held against enemy airborne, ground or sea attack. The Army and Navy will take all necessary measures to maintain supplies to this area and increase the combat strength of the forces there.

(2) Air operations will be intensified, and enemy air strength destroyed as far as possible. Every effort will be made to check increased enemy transport, especially along the east coast of New Guinea, and at the same time to provide thorough protection of our own supply routes.

(3) Army and Navy forces will cooperate in immediately strengthening air defense installations, air bases and supply transport bases in New Guinea and New Britain. Efforts will also be made, principally by Army forces, to complete the construction of necessary roads and speed the accumulation of military supplies. New operational bases will be developed in New Guinea and western New Britain.

(4) Troop strength in the Lae-Salamaua area will be reinforced, and various military installations improved. Preparations will subsequently be made for the resumption of operations against Port Moresby.

3. Air Operations:

a. In order to facilitate general operations, the Army and Navy will speedily reinforce their air strength and expand air operations on a large scale.

b. Special effort will be made to increase the effectiveness of these operations by close cooperation between Army and Navy Air forces.

Under further stipulations governing air operations, missions of the Army Air forces were restricted principally to the New Guinea area, while the Navy Air forces, in addition to supporting New Guinea air operations, remained primarily responsible for defense of the Bismarck Archipelago and solely responsible for air operations in the Solomons. Army air strength in the southeast area was to be stepped up to 240 aircraft of all types by September 1943, and Navy air strength to 357 planes, exclusive of carrier-borne aircraft, by the end of June.113

[205]

To implement the Imperial General Headquarters directive, Lt. Gen. Imamura, Eighth Area Army Commander, summoned a conference at Rabaul on 12 April, attended by the commanders of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Armies, the 6th Air Division, and units under direct Area Army command. At this conference, the following Area Army order was issued, specifying the missions of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Armies and 6th Air Division:114

1. In cooperation with the Navy, the Area Army will endeavor to achieve the following objective: In the New Guinea area, to consolidate its strategic position and carry out preparations for subsequent offensive operations. In the Solomons and Bismarck Archipelago, to consolidate and strengthen present positions.

2. The Seventeenth Army, in cooperation with the Navy, will conduct operations in the Solomons area in accordance with the following:

a. The Army will assume responsibility for the defense of the northern Solomons. It will consolidate and, as far as possible, strengthen existing positions.

b. In matters pertaining to operational preparations, the Army will direct Army units operating under Navy command in the zone of naval responsibility in the central Solomons. . . .

3. The Eighteenth Army, in cooperation with the Navy, will conduct operations in the New Guinea area in accordance with the following:

a. The Army will first secure the strategic sectors of Lae and Salamaua, and by assuring the flow of supplies to these sectors, establish a firm basis for strengthening the Army's strategic position. To facilitate these objectives, the Army will speedily formulate plans for the establishment of overland and coastal supply routes linking Madang and western New Britain with the Lae areas.

b. To strengthen transport and supply operations, line of communications and naval transport bases will be established and improved at important points along the eastern New Guinea coast west of Madang. Air bases will also be established as required.

c. Along with the consolidation of the Army's strategic position as outlined above, all positions will be strengthened and preparations made for future operations.

4. The 6th Air Division will gradually advance its bases of operation to eastern New Guinea and, in cooperation with the Navy, will undertake the following missions. . . .:

a. Destruction of enemy air power in the eastern New Guinea area.

b. Provision of direct air cover for water transport in this area.

c. Direct support, when required, of Army ground operations.

d. Constant reconnaissance of enemy land and sea communication routes in the eastern New Guinea area, and attacks on these lines whenever opportune.

e. Defense of Rabaul.

f. Ferrying of supplies to the front by air, whenever necessary.

Although the Imperial General Headquarters directive of 25 March and Eighth Area Army's implementing order clearly shifted the weight of the Japanese military effort in the southeast area to New Guinea, actually this shift was difficult to accomplish. By 12 April when the Area Army order was issued, transport by destroyer from New Britain to Finschhafen had already become impossible, and the only means of moving men and supplies to Lae was slow and arduous transport by submarine and small craft. Moreover, the combat effectiveness of Japanese forces already stationed in sectors of New Guinea within range of Allied air power was gradually being worn down even before these forces were engaged in actual fighting.

Under these circumstances only the air forces were capable of taking offensive action on the New Guinea front. In order to deter the buildup of enemy strength and to assist the attempts to reinforce advance positions, Admiral Yamamoto, Commander-in-Chief of the Combined Fleet, promptly ordered the Navy Air forces to launch an all-out offensive directed principally at enemy bases in Papua. In addition to 72

[206]

land-based medium bombers, 27 carrier dive-bombers and 86 fighters of the Eleventh Air Fleet, the Third Fleet was ordered to participate in the operation with 54 carrier divebombers, 96 fighters and a number of carrier torpedoplanes.115

The offensive began under the command of Admiral Yamamoto on 7 April with a powerful strike by 71 dive-bombers and 157 fighters against enemy naval and transport shipping at Guadalcanal, in the Solomons. Air action reports claimed damage to one cruiser, one destroyer and 8 transports, in addition to 28 enemy planes shot down. Japanese losses were 21 planes.