CHAPTER XIII

STRUGGLE FOR LEYTE

Activation of Sho Operation No. 1

In the growing light of dawn on 17 October, the Japanese naval radar station and lookout post on Suluan Island, lying athwart the entrance to Leyte Gulf, suddenly discovered the presence of an enemy task force standing inshore.1 At 0719 an urgent warning was flashed to all Navy headquarters, reporting the approach of one enemy battleships, and six destroyers. This was followed an hour later by a second terse report: "Enemy elements have begun landing". Then the Suluan radio ceased transmitting.

Admiral Toyoda, Commander-in-Chief of the Combined Fleet, was still at Shinchiku, Formosa, when these reports were received.2 Promptly interpreting the landing as preliminary to an invasion, he issued an order at 0809 alerting the entire Combined Fleet for Sho Operation No. 1.3 This was followed at 0928 by an order directing Vice Adm. Kurita's First Striking Force to advance at once from Lingga anchorage to Brunei Bay, North Borneo, in preparation for a sortie against the enemy invasion fleet. A further order issued at noon directed the Task Force Main Body, under Vice Adm. Ozawa, to prepare for a coordinated sortie from home waters to facilitate the attack of the Kurita Force.4

Meanwhile, the Fourth Air Army had vainly been endeavoring to clarify the situation in Leyte Gulf. At 0800, the 2d Air Division was ordered to conduct search operations and pre pare to attack any enemy shipping which might be discovered. However, bad weather hampered reconnaissance flights, and the situation remained obscure throughout the morning.5 Lacking confirmation of the enemy landing

[365]

from Army sources, Southern Army headquarters at Manila regarded the Suluan reports with some suspicion in view of the earlier false landing scare at Davao.

In the early afternoon, however, corroborative evidence began to appear. At 1230 naval reconnaissance planes from Legaspi, favored by a brief break in the weather over the gulf, spotted the enemy task force off Suluan. The First Air Fleet immediately ordered an attack, but by the time the attack group of 13 planes reached the scene, the weather had closed in again, and the enemy ships were invisible. Enemy carrier aircraft had meanwhile launched attacks, beginning shortly after 0800, on air bases in the Manila area, at Legaspi and on Cebu, clearly indicating that hostile surface forces were operating off the Philippines.

These developments convinced Army headquarters by the afternoon of 17 October that the Suluan landing was indeed a fact, but there was still doubt as to whether or not it represented the beginning of a major invasion operation. The scattered enemy air attacks did not for the moment appear to point to imminent invasion,6 and belief persisted that a major enemy venture was unlikely in view of the damage believed inflicted on the enemy's naval forces in the Formosa air battle. Both Southern Army and Fourteenth Area Army thus remained undecided.

By the night of 17 October, however, a more serious view began to prevail. Fourth Air Army headquarters concluded that the carrier air strikes, carried out in the face of extremely bad weather, indicated that some major enemy move was afoot. In addition, intercepts of enemy tactical radio messages gave evidence of unusual activity. Lt. Gen. Kyoji Tominaga, Fourth Air Army Commander, immediately relayed this information to Southern Army headquarters and recommended that steps be taken to activate Sho Operation No. 1.7

Field Marshal Hisaichi Terauchi, Southern Army Commander-in-Chief, now agreed that the weight of evidence pointed to a probable invasion of the Philippines. He therefore sent an immediate recommendation to Imperial General Headquarters for the activation of Sho Operation No. 1 and ordered the Fourth Air Army to launch attacks on the enemy ships off Leyte without delay. Lt. Gen. Tominaga promptly assigned this mission to the 2d Air Division and also ordered the newly-organized 30th Fighter Group to assemble its strength with all possible haste at forward bases in the central Philippines.8

As day broke on 18 October, a violent storm with 65 mile-per-hour winds enveloped the entire Leyte Gulf area, preventing the 2d Air Division from executing its attack orders. During the morning, 16th Division lookout posts along the Leyte coast reported sighting an undetermined number of enemy ships inside the gulf. The division radioed this information to Thirty-fifth Army headquarters on Cebu and also to Fourteenth Area Army headquarters at Manila. The report, however, noted the possibility that the enemy ships might have entered the gulf merely to take temporary refuge from the storm, a hypothesis which was supported by the fact that they had as yet

[366]

taken no hostile action.9

Despite the indecisive nature of the 16th Division report, the Thirty-fifth Army and Fourteenth Area Army commands shared Field Marshal Terauchi's estimate that the enemy was about to begin an invasion. It was still considered premature, however, to assume that the enemy's objective would necessarily be Leyte, though this appeared to be the greatest probability.

Meanwhile, Combined Fleet, in close consultation with the Navy High Command, had hastily drawn up a new battle plan for Sho Operation No. 1 to conform to changes in fleet disposition and carrier air strength resulting from the Formosa Air Battle. This plan, issued to the Fleet at 1110 on 18 October, was considered tentative, to apply only in the event of an immediate enemy invasion attempt at Leyte. Its essential points were as follows:10

1. The enemy's over-all landing plans have not yet been ascertained, but judging from the landing on Suluan Island, the sweeping of Surigao Strait, and the air attacks on Manila and Cebu, the possibility of a landing in the Tacloban area is considered great.

2. In the event such a landing attempt materializes, Combined Fleet surface and air forces will operate as follows:

a. The First Striking Force will advance through San Bernardino Strait and attack the enemy invasion forces.b. In coordination with this attack, the Task Force Main Body will lure the enemy to the north and attack elements of the enemy forces at the most favorable opportunity.11

c. The Second Striking Force will come under the command of Southwest Area Fleet and will cooperate with the Army in executing counter-landings.12

d. The base air forces will concentrate in the Philippines for an all-out attack on the enemy carrier groups.

e. The Advance Submarine Force will attack damaged enemy vessels and amphibious convoys with all forces at its command.

f. The First Striking Force will execute its attack against the enemy invasion forces at the landing point on X-Day. The Task Force Main Body will advance to the area east of Luzon on X-1 or X-2.

g. X-Day will be announced by separate order. It is tentatively set at 24 October.

[367]

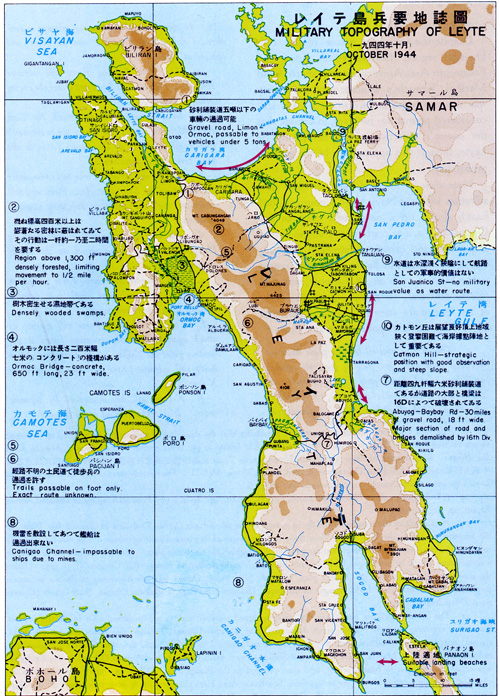

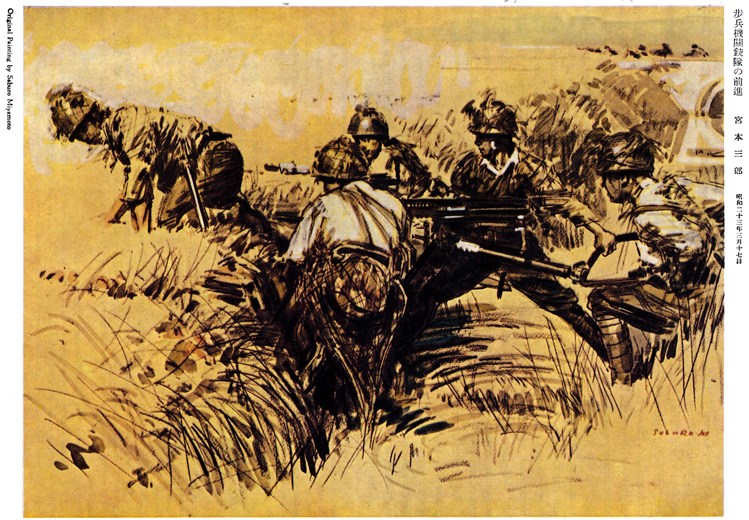

PLATE NO. 87

Military Topography of Leyte

[368]

In Leyte Gulf, events now began to move more rapidly. During the afternoon of 18 October, enemy naval units unleashed a heavy gunfire bombardment of the Dulag, Catmon Hill, and Tolosa sectors, while minesweepers boldly penetrated into the northern part of the gulf and began sweeping operations. Enemy carrier planes meanwhile flew a total of 400 sorties throughout the day against airfields on Luzon and in the Visayas. It was becoming clear that amphibious operations would be launched momentarily.

In Tokyo, the Army and Navy Sections of Imperial General Headquarters had been closely watching developments. Following receipt of Field Marshal Terauchi's message recommending activation of Sho Operation No. 1, the Army Section decided that the situation had become sufficiently clear to warrant such a step. Joint consultations had already been held with the Navy Section to secure coordinated action.

As a result of these consultations, the Navy Section, at 1701 on 18 October, issued a directive to Combined Fleet ordering the execution of Sho Operation No. J.13 This was followed immediately by an Army Section order activating the same operation for all Army forces concerned. The latter order stated:14

1. The Philippines are designated as the area of decisive battle for the Japanese armed forces.

2. The Commander-in-Chief, Southern Army, in cooperation with the Navy, will conduct decisive battle operations against the main strength of the United States forces attacking the Philippines.

3. The Commander-in-Chief, China Expeditionary Army, and the Commander, Tenth Area (Formosa) the Army, will take all necessary action to facilitate above operations.

Simultaneously with its decision to activate the Sho-Go Operation, the Army Section re-examined the existing plan to withhold decisive ground action until the invasion of Luzon. The High Command was now convinced, on the basis of the results believed obtained in the Formosa Air Battle, that conditions had become highly favorable to the conduct of decisive ground operations in the central Philippines.

More than one-half of the American fleet's known carrier strength was still believed to have been destroyed or put out of action in the Formosa Battle. It consequently appeared that the enemy, counting upon the heavy damage he had inflicted on the Japanese air forces, was undertaking the invasion of the Leyte area with seriously reduced carrier strength. Land-based air support would have to come from the distant enemy bases on Palau and Morotai, neither of which was within effective fighter range.

Although Japanese air losses had admittedly been severe, the High Command estimated that these could be replaced with relatively greater speed than the enemy could replenish his carrier forces. The Japanese air forces therefore had good prospects of gaining at least temporary local superiority over the Philippines. This would make possible the safe movement of troop reinforcements and supplies to the Leyte invasion area, thus eliminating the major reason for the original decision to attempt only a delaying action in the central or southern Philippines.

Imperial General Headquarters therefore made the crucial decision to set aside the previous Sho-Go plan and throw all available ground strength into Leyte. The disadvantages inherent in a last-minute change of plan were believed greatly outweighed by the better

[369]

prospects of dealing a crushing defeat to the enemy through simultaneous and concerted commitment of air, sea and ground forces.15

To transmit this decision to the theater command, the Army Section of Imperial General Headquarters decided to dispatch a staff liaison group to Manila. This group, headed by Col. Ichiji Sugita of the Operations Section, left Tokyo by air on the morning of 19 October, stopping at Taihoku, Formosa, to effect necessary liaison with Tenth Area Army. Meanwhile, Field Marshal Terauchi and General Yamashita at Manila continued to shape their plans on the basis of the standing instructions to fight only a strategic delaying action in the central Philippines.16

Southern Army, early on 19 October, had issued an order to Fourteenth Area Army and Fourth Air Army, implementing the Imperial General Headquarters order of the 18th for activation of Sho Operation No. 1. This stated in substance:17

I. Activation of Sho Operation No. 1 has been ordered.

2. The Southern Army, assembling all its fighting power, will seek decisive battle with the main strength of the enemy forces landing in the Philippines.

3. All forces must fulfill their assigned missions by every means at their disposal and must fight this battle to a successful conclusion.

Pursuant to this order, Fourteenth Area Army on the same day directed Lt. Gen. Suzuki, Thirty-fifth Army Commander, to commit maximum strength to Leyte for the execution of the Army's assigned mission of strategic delay in that sector.18 Lt. Gen. Suzuki simultaneously ordered activation of the Suzu No. 2 Operation (Cf. Chapter XI) and directed the 16th Division to repel enemy landing forces and secure the Leyte airfields.

Enemy activity in Leyte Gulf meanwhile was accelerating rapidly. Beaches along the Leyte east coast were aggressively reconnoitered by small landing parties.19 Shore installations were shelled and bombed. Various types of shipping continued to enter the gulf in ever increasing numbers. The main enemy landing effort was obviously imminent.

Despite the optimism of the Army High Command with regard to the prospects of gaining eventual air superiority in the battle area, it was already evident that the air phase of the Sho-Go Operation plans was not working out as intended. Those plans had envisaged mass air attacks against the invading enemy naval forces and troop convoys beginning prior to their arrival at the landing point. Thus, the enemy would suffer severe losses before his troops could hit the invasion beaches.20

The enemy, however, had forestalled these

[370]

plans by striking at Leyte before the planned concentration of Japanese air strength in the Philippines had been completed, and before the Navy's base air forces had time to recover from losses sustained in the Formosa Air Battle and earlier enemy carrier strikes on the Philippines. The First Air Fleet, already in the Philippines, had been reduced to an operational strength of less than 50 aircraft.21 The Second Air Fleet, which had lost half its strength in the Formosa Battle, had not yet begun its redeployment from Formosa to the Philippines.

Although the Fourth Air Army had sustained relatively lighter losses, its strength was widely dispersed. Before it could operate effectively in the Leyte area, it had to concentrate at forward bases in the central Philippines,22 an operation rendered both difficult and dangerous by enemy action, bad weather, and the virtually useless condition of many of the forward fields due to continuous rains. Under such unfavorable conditions, the concentration required a minimum of several days, and in the meanwhile the enemy was able to operate in Leyte Gulf against extremely light air opposition.

On 19 October, when weather conditions finally permitted an air attack against the enemy invasion fleet, no more than five naval and three Army aircraft could be mustered against the steadily increasing concentration of enemy shipping in Leyte Gulf.23

Air reconnaissance during 19 October gave the first clear indication of the size of the invasion force which the enemy was throwing against Leyte. At 0810 only 18 transports were reported in the gulf, together with some 34 naval ships, including six carriers. By 1800 of the same day, the number of transports reported in or near the gulf had increased to 100, and the naval units to 46, including six carriers and ten battleships. At the same time, two covering naval task groups, one with four carriers and the other with two, were reported maneuvering off the east coast of Luzon.24 In the Admiralties and at Hollandia, further large concentrations of invasion shipping were reported in readiness for departure.25

It was evident from these reports that the invading forces would be formidable. The only major combat unit available to counter the first wave of the assault pending the concentration of forces from other sectors of the Philippines was Lt. Gen. Shiro Makino's 16th Division, veterans of the initial Japanese conquest of the Philippines and strongest of the Thirty-fifth. Army's field divisions.

Estimating that enemy landings would most probably occur in the Dulag-Tarragona-Abuyog sector, Lt. Gen. Makino had disposed the bulk

[371]

of his troops in prepared coastal positions between Abuyog on the south and Palo on the north, with the heaviest concentration of strength in the vicinity of Dulag. Construction of a secondary defense line through Tabontabon and Santa Ana and of the projected main line along an axis running through Dagami and Burauen, was still incomplete due to terrain difficulties and guerrilla in terference.26 Division headquarters and rear installations remained in the Tacloban sector, to the north of the main defensive dispositions.27 (Plate No. 88)

Except for minor elements left on Luzon and Samar, Lt. Gen. Makino had at his immediate disposal the full combat strength of the 16th Division, in addition to 4th Air Division ground units in the area, and part of the service forces of Thirty-fifth Army. Elements of the 36th Naval Garrison Unit at Ormoc and Tacloban were to come under his command immediately upon an enemy invasion.28

Tactically the main combat forces were organized in two groups, the first responsible for defense of the right flank sector south of and including Dulag and Burauen, and the second charged with operations in the sector extending from Catmon Hill (inclusive) to Palo (exclusive). The main strength of the division reserve (33d Infantry, less 2d Battalion) was stationed in the Palo sector, with elements at Dagami (1st Battalion, 20th Infantry), Tagungtong (2d Battalion, 33d Infantry), and north of Burauen (7th Independent Tank Company). Artillery

[372]

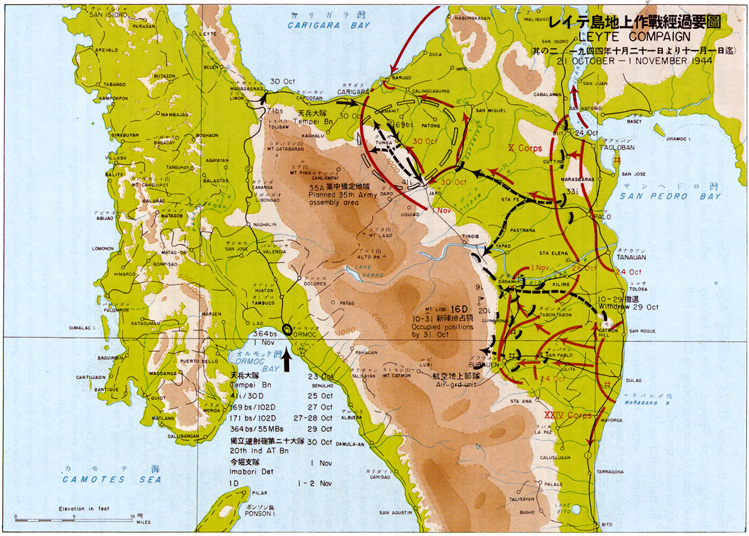

PLATE NO. 88

Disposition of 16th Division-Leyte, 17 October 1944

[373]

retained under division control was emplaced at Catmon Hill, San Jose, and Tolosa. The tactical allocation of units was as follows:29

| Southern Defense Unit: | 20th Inf. (less 1st Bn.) 2d Bn., 22d Arty Regt. (less 6th Co.) |

| Northern Defense Unit: | 9th Inf. (less 2d, 5th, and 7th Cos.) |

| Division Reserve: | 33d Inf. 1st Bn., 20th Inf. 7th Ind. Tank Co. |

| Division Artillery: | 22d Arty. Regt. (less 5 cos.) |

These dispositions remained in effect until 18 October, when the enemy's pre-landing operations in Leyte Gulf afforded Lt. Gen. Makino his first definite clue as to where the invading forces would go ashore. These operations appeared to confirm the previous estimate that the major landing effort would be made in the Dulag area. However, the presence of a large number of enemy ships, as well as minesweeping activity in the northern section of Leyte Gulf also gave ominous indications that the enemy might execute a secondary landing closer to Tacloban, outflanking the main concentration of 16th Division strength and immediately threatening the division headquarters itself.

To meet the completely unexpected threat on the north,30 Lt. Gen. Makino swiftly ordered the 33d Infantry to move its main strength, supported by two batteries of division artillery, into positions in the Palo-San Jose coastal sector.31 Simultaneously, the 2d Battalion of the regiment, which was standing by at Tagungtong in the southern sector, was released from the reserve and assigned to reinforce the Southern Defense Unit. This battalion moved up to Julita to give closer support to the southern flank. The 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry, stationed in reserve at Dagami, was ordered to prepare for rapid motorized movement to any sector where further reinforcements might be required.32 Execution of these orders got under way late on 18 October.

Despite these last-minute moves, Lt. Gen. Makino's forces were ill prepared to meet the overwhelming assault which impended. Defensive works, where they had been completed, were weak and imperfectly disposed.33 Many positions were demolished by the heavy naval gunfire preparation, which continued

[374]

throughout 19 October. The bulk of the 22d Artillery Regiment's guns, with the exception of the battery emplaced on Catmon Hill, were also put out of action by the rain of shells. Effective resistance was further handicapped by a general breakdown in division communications as a combined result of the enemy bombardment and damage wrought by the typhoon of 17-18 October.34

On the morning of 20 October, the enemy finally began his main landing operations. While naval units subjected the shore defenses to a final preparatory bombardment, the enemy's vast transport convoy maneuvered into take-off positions and put more than 200 assault craft into the water. The first waves of the invasion force, now estimated at about three divisions,35 began hitting the beaches at 1130 Japan time (1030 Philippine time).36

The assault was delivered in two main thrusts, one aimed at the Dulag sector, and the other at San Jose, just five miles southeast of Tacloban. (Plate No. 89) As the enemy troops moved ashore, they were subjected to scattered fire from artillery emplacements not destroyed by the naval gunfire and air preparation.37 In the Dulag sector, Col. Keijiro Hokoda's 20th Infantry Regiment put up what initial resistance it could from its shore positions but was unable to prevent the establishment of a small but firm enemy beachhead.

The simultaneous landing near Tacloban was far more critical. The two battalions of the 33d Infantry, which Lt. Gen. Makino had ordered to the Palo-San Jose coastal sector on 18 October, had barely enough time to move into position before the enemy assault began, and the absence of adequate prepared defenses in the area made effective resistance impossible. These elements and the small number of naval troops already in the San Jose sector were forced to fall rapidly back from the beaches. The 1st and 3d Battalions, 33d Infantry, took up strong positions on the heights north and northwest of Palo. The naval troops withdrew northward to Tacloban. By nightfall of 20 October the enemy had overrun Tacloban airfield and penetrated into the outskirts of the town itself.38

Already on the day prior to the enemy landings, Lt. Gen. Makino had decided to establish his command post at Dagami in order to be in a more central location for directing subsequent operations. The division commander and his staff moved out of Tacloban during the night of 19-20 October. Most of the division headquarters and special troops were ordered to

[375]

PLATE NO. 89

Invasion of Leyte, 20-21 October 1944

[376]

follow as soon as possible. The command group was proceeding along the highway west of Palo when reports of the first enemy landings reached them about midday on the 20th.

Immediately perceiving the serious danger to his northern flank as a result of the San Jose landing, Lt. Gen. Makino ordered the division mobile reserve (1st Battalion, 20th Infantry) at Dagami to proceed at once to the Palo-San Jose sector to back up the 33d Infantry. Meanwhile, to bolster the equally hard-pressed forces in the south, the 7th Independent Tank Company was released from division control and ordered to move up from Burt to the Dulag front. Lt. Gen. Makino and his staff continued on to Dagami, arriving early on 21 October.39

The evacuation of Tacloban by the division rear echelon, which began early on 20 October, necessitated the abandonment of permanent wireless installations and resulted in complete severance for forty-eight hours of all contact between the 16th Division and higher headquarters at Cebu and Manila.40 During this critical period, Fourteenth Area Army and Thirty-fifth Army were completely without knowledge of developments on Leyte.

Swiftly exploiting their success on the northern flank, the enemy pushed ahead to occupy Tacloban completely during the night of 20-21 October. The naval garrison elements and 16th Division rear echelon personnel retreated into the hills west of the town. These small forces were all that remained on the extreme north flank, and they now found themselves cut off from the main Japanese forces to the south.

On the southern flank of the San Jose beachhead, the enemy also pressed forward vigorously against the 33d Infantry positions on the heights northwest of Palo. Although enemy elements infiltrated past this strongpoint, the regiment held its positions throughout the 21st and even launched minor counterattacks against the enemy left flank.

In the Dulag area to the south, the enemy forces, after completely occupying Dulag itself, drove on to take the airfield west of the town. They then continued to exert heavy pressure in the direction of Burauen, opposed by the Southern Defense Unit and airfield garrisons of the 34th Air Sector Command. Artillery emplaced on Catmon Hill, which had not yet come under ground assault, shelled the enemy beachhead area, while 9th Infantry elements engaged advancing enemy forces along the northern perimeter of the beachhead above Dulag. Enemy naval bombardment slackened on 21 October, but carrier planes immediately took over the task of supporting the ground forces.

Despite a gradual stiffening of 16th Division resistance, the enemy, by noon of 21 October, had succeeded in extending his northern beachhead from Tacloban south to the mouth of the Palo River, while his southern foothold had been expanded to a roughly semi-circular beachhead about two miles in depth, centered on Dulag.41

Air opposition to the enemy invasion remained on a minor scale as Fourth Air Army and the naval air forces continued the gradual

[377]

concentration of their strength in the Philippines in preparation for the all-out air offensive tentatively set to begin on 24 October.42 On 20 October, 37 Army and Navy planes attacked invasion shipping off Leyte, claiming to have sunk or damaged several enemy craft. The number of attacking planes dropped to 21 on 21 October, and on 22 and 23 October no attacks were carried out.43

Both the 2d Air Division, containing the major combat flying elements of the Fourth Air Army, and the First Air Fleet had undergone command changes just as the enemy invasion of Leyte got under way. Lt. Gen. Isamu Kinoshita took over command of the 2d Air Division from Lt. Gen. Masao Yamase after the latter was wounded in the enemy air strike on Clark Field on 19 October. On the 20th, Vice Adm. Takijiro Onishi relieved Vice Adm. Teraoka as First Air Fleet Commander.44

The assembly of Fourth Air Army strength for the big offensive was proceeding less rapidly than anticipated. Not only was it proving extremely difficult to move already available fighter strength to forward bases, but it appeared unlikely that the transfer from the Homeland and China of the 30th Fighter Group's most powerful units, the 12th Fighter Brigade and tooth Fighter Regiment, could be completed before 22 or 23 October. Second Air Fleet, however, had completed its transfer to Clark and Nichols Fields by the 22d.

Urgent 16th Division dispatches reporting the launching of the enemy invasion reached Thirty-fifth Army headquarters at Cebu and Fourteenth Area Army and Southern Army headquarters at Manila around noon on 20 October. These headquarters tensely waited for further information, but before any detailed reports could come through, the blackout of 16th Division communications drew a cloak of obscurity over the situation on Leyte.

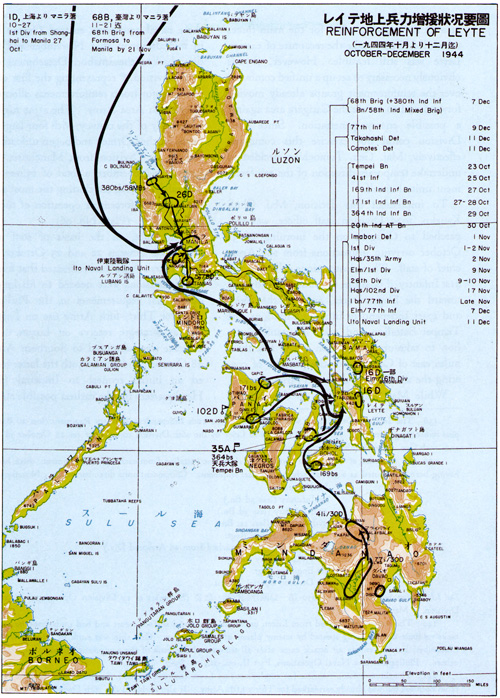

Though handicapped by inadequate information, Thirty-fifth Army took immediate action to move reinforcements to Leyte in accord ance with the Suzu No. 2 Operation plan, which had already been activated on 19 October. Orders were issued during the 20th directing the following units to advance immediately to Leyte, where they were to come under 16th Division command:45

1. 41st Infantry Regiment (less one battalion) of the 30th Division (Army reserve from Mindanao.

2. 169th Infantry Battalion of the I02d Division from the Visayas sector.

3. One infantry battalion of the 57th Independent Mixed Brigade, from Cebu.46

Since Imperial General Headquarters' decision to fight a decisive ground action on Leyte had not yet been transmitted to Southern Army, all Army headquarters in the Philippines were

[378]

still operating on the assumption that only a strategic delaying action would be conducted in accordance with the original Sho-Go plans. The staff mission dispatched by Imperial General Headquarters to transmit this vital decision reached Manila at about 2000 on 20 October, immediately launching into a series of night conferences.47 Developments on Leyte subsequent to the enemy landing remained entirely unknown at this time.48

The High Command directive evoked diametrically opposite reactions from Southern Army and Fourteenth Area Army. Field Marshal Terauchi was entirely in agreement with the decision to wage a decisive ground action on Leyte, since Southern Army headquarters had become increasingly skeptical of the practicability of the original Sho-Go plans.49 Field Marshal Terauchi and his staff held that not only the sea and air forces, but the ground forces as well, must be fully committed in defense of Leyte, since the establishment of an enemy foothold in the central Philippines, involving the acquisition of air bases, would render decisive ground action on Luzon an impossibility.

The reaction of General Yamashita and the Fourteenth Area Army staff, on the other hand, was one of shocked surprise.50 The principal reasons for this doubt on the part of the Area Army command were the following:51

1. Judging from the strength of enemy air attacks in support of the Leyte invasion,52 it appeared highly questionable that the enemy's carrier air strength had been so seriously depleted in the Formosa Air Battle as to assure Japanese ability to gain air superiority. Without such superiority, the movement of large-scale reinforcements to Leyte would be subject to grave risk.

2. The transport of the requisite troop strength to Leyte, and its logistical support, would require shipping far in excess of the amount available to Fourteenth Area Army, and the assembly of shipping from other areas would so delay troop movement as to weigh heavily against the chances of success on Leyte.

3. It was still difficult to determine with certainty whether the invasion of Leyte was the main enemy effort, or whether it would prove to be a limited objective operation preliminary to a quickly following, major attack on Luzon.

[379]

4. Luzon was eventually certain to be invaded by reason of its strategic and political importance to the enemy. Therefore, if Luzon were stripped of troops to reinforce Leyte and, despite this, Leyte were lost, a decisive ground defense of the more strategically important area of Luzon would be seriously prejudiced.

Despite these views, General Yamashita recognized that much depended upon the actual development of the situation on Leyte, and even more upon the outcome of the impending sea and air offensive. He therefore proffered no formal opposition at this time and directed the Area Army staff to begin working out plans to implement the revised operational policy.

Pending the elaboration of these plans, Fourteenth Area Army took steps to obtain Navy cooperation in transporting the 30th Division elements already ordered to Leyte by Thirty-fifth Army. Southwest Area Fleet promptly assented to a request that the 16th Cruiser Division and available naval transports be dispatched to Cagayan, northern Mindanao, by the evening of 24 October to pick up these troops and ferry them to Ormoc, on Leyte.53 Fourteenth Area Army also confirmed Thirty-fifth Army's decision to use the Tempei Battalion and decided, in addition, to make available the 20th Antitank Battalion from Luzon. An Area Army order implementing these arrangements was issued at 1700 on 21 October.54

The following morning Field Marshal Terauchi summoned the Fourteenth Area Army and Fourth Air Army commanders to Southern Army headquarters and transmitted to them a formal order directing compliance with the decision to fight the decisive ground battle on Leyte. This order stated:55

1. The opportunity to annihilate enemy is at hand.

2. The Fourteenth Area Army, in cooperation with the Navy and the Air forces, will muster all strength possible and destroy the enemy on Leyte.

In accordance with this order, General Yamashita promptly ordered the 26th Division, presently on Luzon, to prepare for early shipment to Leyte.56 He also decided that the 1st Division and 68th Brigade, scheduled to reach the Philippines shortly, would be allocated to Thirty-fifth Army as additional reinforcements.57 An urgent dispatch was immediately sent to the Thirty-fifth Army Commander

[380]

notifying him of the vital change in the Army's mission and the reinforcement plans.

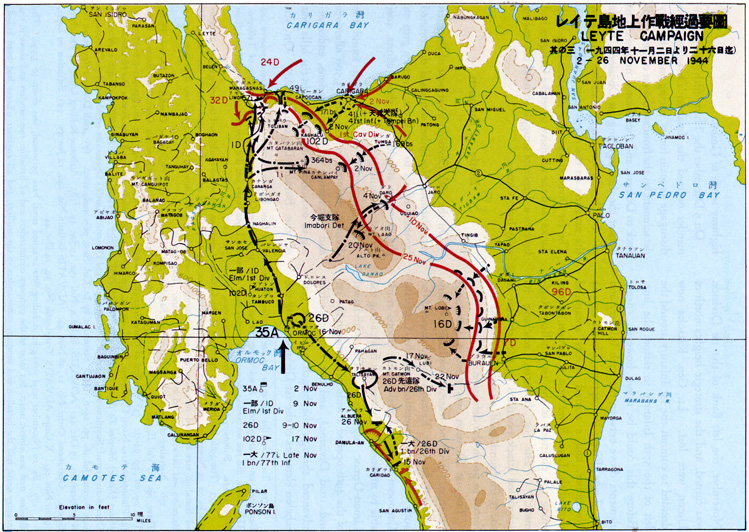

Upon receipt of this dispatch, Lt. Gen. Suzuki and his staff began formulating a new operational plan covering the deployment of forces on Leyte. This plan, completed within the next few days, was essentially as follows:58

1. Operational policy:

a. The Army will act immediately in cooperation with the decisive operations of the naval and air forces.

b. Reinforcements will be concentrated on the plain near Carigara.

c. Enemy troops which have landed near Tacloban and in the Dulag area will be destroyed.

d. The direction of the initial main effort will

be against the enemy in the Dulag area.

e. The general attack will begin on or about 10 November.

2. Allocation of missions:

a. The 16th Div. will hold the Dulag area, Catmon Hill, and the heights west of Tacloban in order to cover the concentration of the main forces of the Thirty-fifth Army.

b. The following units, after landing at the ports indicated, will concentrate on the Carigara plain:

1st Div.-Carigara

26th Div.-Carigara

102d Div. (Hq. and three battalions)-Ormoc

c. After the concentration of the Army's main forces on the Carigara plain and adjacent areas to the southeast, operations will begin with the objective of destroying the enemy in the Dulag and then the Tacloban area.

d. In conjunction with the Army counteroffensive from the Carigara plain, the following units will perform the indicated operations:

(1) 30th Div. (Hq. and three battalions) will land at Albuera or Baybay, advance to the Dulag area, and operate against the enemy's left rear.

(2) If circumstances permit, the 68th Brig. will stage a counterlanding south of Dulag. Failing this, the brigade will land at Ormoc, advance to the Dagami area, and join in the main assault.

3. The headquarters of the Thirty-fifth Army will advance to Leyte.

Owing to the obscurity surrounding the situation on Leyte, the Thirty-fifth Army plan of operations was formulated on the basis of serious miscalculations. First, the enemy invasion force was estimated from the initial intelligence reports at not more than three divisions. Second, it was estimated that the enemy, as in previous instances, would not attempt to advance inland until his Tacloban and Dulag beachheads were joined, thus allowing adequate time for the planned concentration of reinforcements in the Carigara area. Third, even if such an attempt were made, Thirty-fifth Army overconfidently believed that the combat-tested 16th Division would be able to contain the enemy in the eastern part of Leyte long enough to cover the assembly of reinforcements.59

Preparations for Sea-Air Attack

While plans were being made for committing maximum ground strength in the defense of Leyte, the sea and air forces were rushing to complete preparations for the concerted assault on the enemy invasion fleet, which constituted the first phase of the Sho-Go Operations.

At 0813 on 20 October, a few hours prior to the Leyte landings, Admiral Toyoda issued a Combined Fleet order confirming, with minor changes, the tentative battle plan issued two days earlier. The essentials of this order were

[381]

as follows:60

2. The Combined Fleet, in cooperation with the Army, will annihilate the enemy invading the Central Philippines in accordance with the following operational plan

a. The First Striking Force will penetrate to the Tacloban area at dawn on 25 October (X-Day) and destroy the enemy transport group and its covering naval escort forces.

b. In coordination with the attack of the First Striking Force, the Task Force Main Body will maneuver in the area east of Luzon in order to lure the enemy to the north. It will also attack the enemy at the most favorable opportunity.

c. The Southwest Area Force (Southwest Area Fleet) will command all naval air units assembled in the Philippines and will utilize them to destroy the enemy carrier and invasion forces in conjunction with the penetration of the First Striking Force. It will also effect immediate amphibious counterlandings on Leyte in cooperation with the Army.

d. The main strength of the 6th Base Air Force (Second Air Fleet will advance to the Philippines and come under the command of Southwest Area Force. It will execute a general attack against enemy task forces on 24 October (Y-Day).

e. The Advance Submarine Force will continue its previously assigned missions, as will other forces participating in the Sho-Go Operation.

While this order was being disseminated, the surface forces scheduled to participate in the attack were already maneuvering into position. Vice Adm. Kurita's First Striking Force reached Brunei Bay, North Borneo, at noon on 20 October, and began making final preparations. Far to the north, Vice Adm. Ozawa's Task Force Main Body sortied from the Bungo Channel, at the southern entrance to the Inland Sea, on the afternoon of the same day, immediately after receiving the Combined Fleet battle order.

The mission of the Ozawa force was of vital importance to the success of the over-all plan. It was to act as a decoy to draw off the main strength of the enemy naval forces covering the invasion operations in Leyte Gulf, thus allowing the First Striking Force to penetrate to the landing point and smash the enemy's troop and supply ships. To heighten its effectiveness as a lure, the Ozawa Force sortied with all of the 3d Carrier Division, made up of the regular carrier Zuikaku and the light carriers Zuiho, Chitose, and Chiyoda. The total number of aircraft available to put aboard these ships, however, was only 108. These belonged to the poorly trained air groups of the 1st Carrier Division and represented about half the normal complement. In addition to the half-empty carriers, the force comprised two battleships (Ise, Hyuga),61 three light cruisers(Oyodo, Tama, Isuzu) and eight destroyers (31st Destroyer Squadron).62 Vice Adm. Ozawa fully anticipated that his fleet would be completely wiped out, but this sacrifice was deemed essential to achieve the primary objective-destruction of the entire enemy invasion force.63

[382]

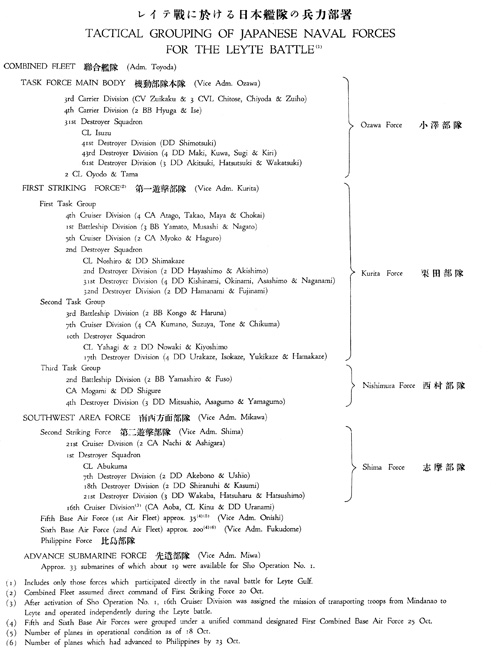

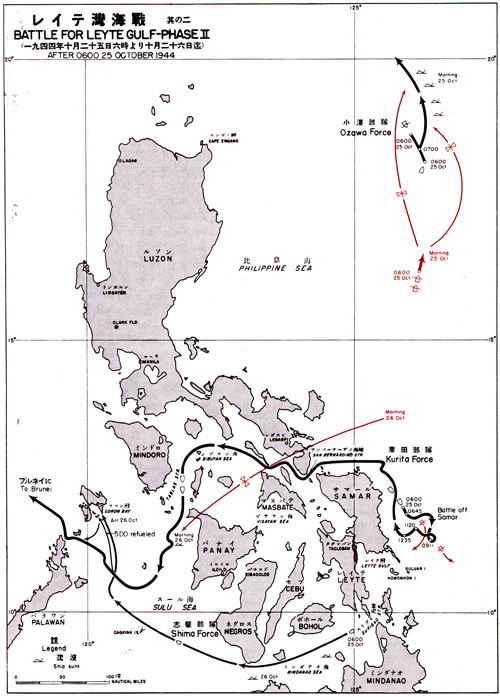

PLATE NO. 90

Tactical Grouping of Japanese Naval Forces for the Leyte Battle

[383]

Vice Adm. Kurita's First Striking Force, by the night of 21 October, had almost completed final preparations for its sortie from Brunei. By order of Admiral Toyoda, it was to operate henceforth under direct Combined Fleet command instead of under Vice Adm. Ozawa, who thus became responsible only for directing the Task Force Main Body.64 Late on 21 October, Vice Adm. Kurita issued to his subordinate commanders a final battle plan calling for twin, coordinated thrusts at Leyte Gulf from north and south. This plan was as follows:65

I. Mission: In accordance with Combined Fleet dispatch order No. 363, this Force, in cooperation with action of the base air forces and the Task Force Main Body, will sortie to the Tacloban area at daybreak on 25 October.66 After destroying enemy naval forces in the vicinity, it will annihilate enemy transports and landing forces.

2. Dispositions and Operational Procedure

a. 1 will personally lead the 1st and 2d Task Groups, starting from Brunei at 0800 22 October. After penetrating through San Bernardino Strait at sunset on 24 October, I will destroy the enemy surface forces in night battle east of Samar and then proceed to the Tacloban area at daybreak on 25 October to destroy the enemy transport convoy and landing forces.

b. The 3d Task Group under command of Vice Adm. Nishimura will leave Brunei at a time fixed by the commander and move up separately. At daybreak on 25 October, this force will sortie to the Tacloban area through Surigao Strait and cooperate with the main body in annihilating the enemy transports and landing forces.

While the Kurita Force was preparing to weigh anchor, the Second Striking Force under Vice Adm. Shima was enroute from the Pes cadores to Manila, where it was to operate with the 16th Cruiser Division in moving troops to Leyte. Since Fourteenth Area Army had indicated that no troops were ready to embark, however, Combined Fleet suggested to Southwest Area Force, now commanding the Second Striking Force, that Vice Adm. Shima's ships be utilized temporarily to support Vice Adm. Kurita's attack. Southwest Area Force concurred and radioed Vice Adm. Shima to take his force to Coron Bay and refuel there from fleet tankers in preparation for a possible sortie through Surigao Strait.67

At 0800 on 22 October, the main body of

[384]

the First Striking Force sortied from Brunei Bay as planned, and seven hours later Vice Adm. Nishimura's 3d Task Group cleared the anchorage en route for Surigao. Far to the north, Vice Adm. Ozawa's imposing but actu ally weak decoy force was due east of Okinawa, heading south into the Philippine Sea. The surface phase of the Sho-Go Operation plan had swung into action.

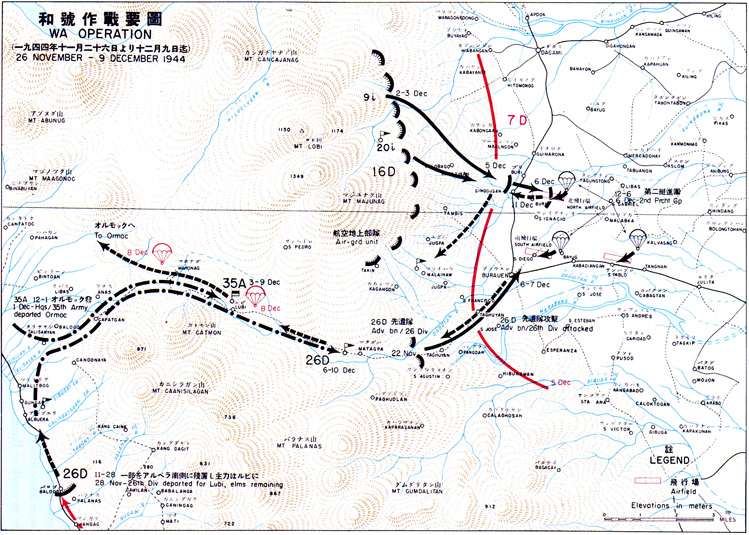

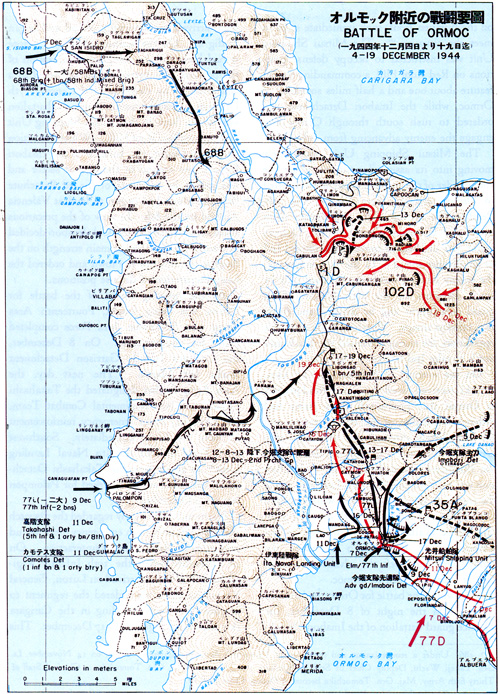

Meanwhile, the Army and Navy air forces were speedily concentrating their strength in the Philippines for the start of the coordinated air offensive on 24 October, one day in advance of the fleet attack. (Plate No. 91) This was essential to the success of the entire plan, both to cover the penetration of Vice Adm. Kurita's attack groups to the landing point and to destroy a portion of the opposing naval strength, particularly carriers, in advance of Kurita's attack.

The Second Air Fleet was assembled in the Manila area (principally Clark Field) with all units expected to reach full operational readiness at their new bases by 23 October. Fourth Air Army, however, was experiencing more difficulty in assembling its scattered forces and barely expected to get them deployed at their battle stations in time. Lt. Gen. Tominaga, Fourth Air Army Commander, nevertheless had issued the following order on 21 October directing final dispositions for the attack:68

1. The enemy is continuing to land on Leyte. The main strength of our Navy has started operations with the objective of destroying the enemy in the waters east of the Philippines.

2. Fourth Air Army will employ its entire strength in an effort to annihilate enemy ships engaged in landing troops in the Leyte Gulf area.

3. Pending concentration of the 30th Fighter Group in the central Philippines, the 2d Air Division will continue attacking the enemy on the present basis. Upon arrival of the 30th Fighter Group, the division will assume command of this unit and launch attacks in force as soon as possible. These attacks will be continued in full strength thereafter.

4. The 30th Fighter Group will deploy in the central Philippines by the evening of 23 October and come under command of the 2d Air Division.

5. Fourth Air Army will establish an advance command post at Bacolod by the evening of 23 October.

The deployment plan of the 2d Air Division, which was to command all Army combat flying elements assembling in the Philippines, envisaged retaining heavy and light bomber units at Clark Field and Lipa, on Luzon. Fighter, fighter-bomber, and reconnaissance units, be cause of their shorter range, were to operate from bases around Bacolod, on Negros Island. As the deployment of the latter progressed, the taxi strips at the Negros bases became so soft and muddy under prolonged rainfall that the useability of the fields was seriously reduced. However, alternate bases were lacking, and time was so short that plans could not be changed.69

In spite of many difficulties, Fourth Air Army succeeded, by late on 23 October, in gathering together the bulk of its widely scattered units and deploying them for the decisive battle. This redeployment operation was as follows:70

[385]

PLATE NO. 91

Air Reinforcement of the Philippines, October-December 1944

[386]

To Bacolod:

16th Fighter Brigade from Clark Field

22d Fighter Brigade from Manila

Fighter complement of the 9th Composite Air Brigade from Celebes

6th Fighter-Bomber Brigade from North Borneo 2d Air Reconnaissance Regt. from Clark Field 10th Fighter Regt. From Formosa

To Manila:

One-half of the 12th Fighter Brigade (30th Fighter Group) from the Homeland and China

To Lipa:

Bomber complement of the 3d Composite Air Brigade from Celebes

3d Light Bomber Regt. (25th Bomber Brigade) from Formosa

To Clark Field:

7th Heavy Bomber Brigade from Malaya

14th Heavy Bomber Regt. (25th Bomber Brigade) from Formosa

On the evening of 23 October, Lt. Gen. Tominaga proceeded from Manila to Bacolod and established the advanced command post of Fourth Air Army. Nearly 400 Army and Navy craft were now poised at Philippine bases in readiness for the decisive air and sea battle.71

Leyte Sea Battle : First Phase

At dawn on 23 October, the main body of Vice Adm. Kurita's powerful surface attack force, speeding northward from Brunei, sustained the first of series of telling blows which ultimately reduced the force of 32 ships to less than half its original strength before it had reached the objective. This initial blow was struck by enemy submarines. (Plate No. 92)

At 0634, as the Force passed up the western side of Palawan, a spread of torpedoes suddenly entered the cruising disposition. Four of these squarely hit the flagship, the heavy cruiser Atago, which sank inside of 19 minutes, the destroyer Kishinami taking off Vice Adm. Kurita and his staff. Two more torpedoes struck the heavy cruiser Takao, inflicting such severe damage that she had to be ordered back to Brunei under destroyer escort.

Twenty-two minutes after the first attack, another spread of torpedoes found its mark on the heavy cruiser Maya, which blew up and sank in four minutes. Within the space of less than half an hour, the Kurita Force had thus lost three major combat units, not counting the destroyers Naganami and Asashimo detached to accompany the crippled Takao back to port. Far more serious, the submarine contact had alerted the enemy two full days in advance of the scheduled assault on Leyte Gulf.

Vice Adm. Kurita's undamaged ships sailed on at high speed after the submarine attacks, not slowing down until 1623, when it was considered safe to effect the transfer of the commander and his staff from Kishinami to the super-battleship Yamato, which he had decided to make his flagship. The force then continued northward, heading into Mindoro Strait during the night.

During the 23d, Vice Adm. Nishimura's southern force (3d Task Group) had meanwhile negotiated Balabac Strait without incident and begun crossing the Sulu Sea. Vice Adm. Shima's Second Striking Force, now under definite orders to penetrate Surigao Strait on the night of 24 October in support of the

[387]

Nishimura group,72 had reached Coron Bay on schedule and was making final preparations to sortie.73 To the north, Vice Adm. Ozawa's decoy force, after refueling its destroyers from larger units about 800 miles east of Formosa, had set a southwesterly course, at the same time opening up a powerful long-wave radio transmitter aboard the flagship in order to attract enemy attention.

At dawn on 24 October, the critical air phase of the battle plan swung into action. At 0630, the full strength of the First and Second Air Fleets-199 planes-took off from Clark Field to sweep the waters east of Luzon.74 This force, after nearly two and a half hours' flying, finally spotted an enemy group with a nucleus of six carriers 160 miles east of Manila and immediately attacked. Action reports claimed one battleship set afire, one carrier and one cruiser damaged, and 32 enemy planes shot down. Japanese losses were heavy, 67 planes failing to return to base.75

While this attack was in progress, a search plane discovered a second enemy group with two carriers about 40 miles to the north, and at 0940 a third group including three carriers was spotted due east of San Bernardino Strait. The importance of knocking out this third group to facilitate the penetration of Kurita's force was fully realized, but the all-out effort of the morning made it impossible to mount another attack until early evening. An attack group of 24 planes then sortied but, unable to locate the enemy force off San Bernardino due to poor visibility, turned north to attack the enemy groups east of Luzon instead. The results of these attacks were not ascertained.76

Army air units had meanwhile launched full-scale attacks against enemy invasion shipping in Leyte Gulf itself. Beginning at 0800, the 2d Air Division mounted three major attacks during the 24th, using 80 planes in the first attack, 38 in the second, and 29 in the final attack at dusk. Results reported, however, were extremely meager. In all three attacks, only one seaplane tender, one cruiser and one landing craft were believed sunk, with five transports and two cruisers damaged.77

The first day of the land-based air offensive had thus failed to achieve one of its most vital objectives, the neutralization of the enemy carrier forces threatening Vice Adm. Kurita's two-pronged thrust toward Leyte Gulf. At the same time, Vice Adm. Ozawa's parallel effort to lure these forces to the north, where they could not interfere with Kurita's advance, had produced no apparent results by late afternoon of the 24th, a failure that was not, however, attributable to lack of persistence on the part of the Task Force Main Body. Indeed Vice

[388]

Adm. Ozawa, convinced that the luring opera tion could only succeed if the enemy were given a physical demonstration of the proximity of his force, had actually closed to within 150 miles of the northernmost enemy task group and sent all his operable aircraft, totalling 56 of all types, to carry out an attack.78 When this attack still drew no enemy retaliation, Vice Adm. Ozawa in mid-afternoon ordered his advance guard (Ise, Hyuga and four destroyers) under Rear Adm. Chiaki Matsuda to break away from the carriers, proceed south, and forcibly divert the enemy by a night attack.79

The combined ineffectiveness of the air offensive and of Vice Adm. Ozawa's decoy operation had meanwhile brought further disaster to the Kurita Force as it headed across the Sibuyan Sea toward San Bernardino Strait. At 0810 on the 24th, enemy scout planes spotted the Force in Tablas Strait, and at 1025 a group of about 30 carrier aircraft swept in for the first attack. The super-battleship Musashi and heavy cruiser Myoko both sustained aerial torpedo hits, and in addition Musashi was hit by a heavy bomb. Damage to the strongly-armored Musashi was negligible, but Myoko, her speed cut to 15 knots, dropped out of formation and was ordered back to Brunei.80

Almost simultaneously with this first attack on the Kurita Force, Vice Adm. Nishimura's 3d Task Group diving across the Sulu Sea was discovered and attacked by 22 enemy carrier planes just south of the Cagayan Islands. The battleship Fuso and destroyer Shigure received bomb hits which caused only superficial damage, and the force raced on toward Surigao Strait,81 followed closely by Vice Adm. Shima's Second Striking Force, which had sortied from

[389]

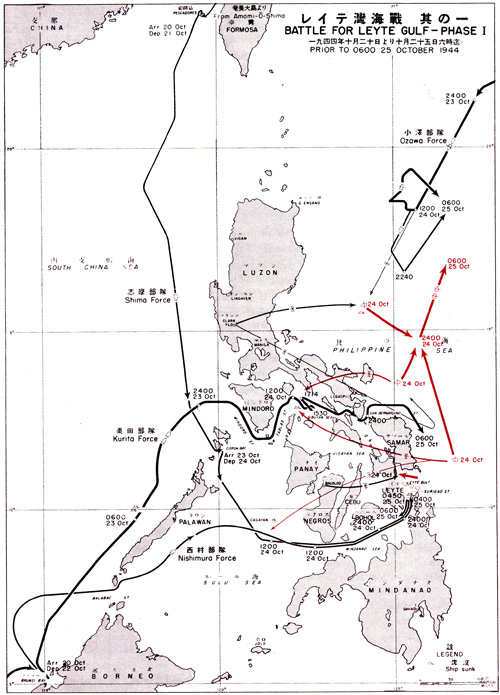

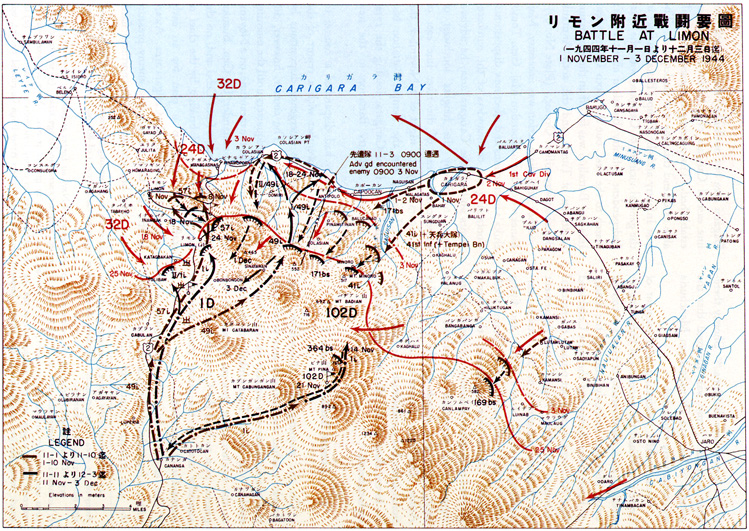

PLATE NO. 92

Battle for Leyte Gulf, Phase I, Prior to 0600 25 October 1944

[390]

Coron Bay at 0400.

Enemy air attacks on the Kurita Force were renewed with deadly intensity on the afternoon of the 24th. At 1207 the second wave of about 30 carrier aircraft attacked, concentrating on Musashi, which took three more torpedoes and two large bombs. The speed of the 64,000-ton battleship was reduced to 22 knots, and the disposition had to slow down to keep her in formation. At 1315, hoping to spur the air forces and the Ozawa Force into more effective action to ease enemy pressure on his group, Vice Adm. Kurita dispatched the following radio to Vice Adm. Ozawa and Southwest Area Force:82

I am receiving repeated torpedo and bomb attacks by enemy carrier aircraft. Request urgent information concerning situation as regards attacks on, or contacts with, the enemy by your forces.

Immediately after the dispatch of this message, a third enemy attack wave swept in to inflict new damage. Five more aerial torpedoes struck Musashi, while four bomb hits shattered her superstructure. Down badly at the head, the huge ship lost further speed and fell slowly astern of the disposition. Vice Adm. Kurita's flagship Yamato also received a torpedo hit, but damage was superficial. A fourth attack one hour later resulted in further slight damage to Yamato and to the battleship Nagato.

With Musashi too badly damaged to continue, Vice Adm. Kurita at 1452 ordered the destroyer Kiyoshimo to escort her back to Mako in the Pescadores. Just as the retirement was getting under way, however, the fifth and heaviest air attack of the day began, enemy carrier aircraft completing the destruction of Musashi with 11 more torpedoes and ten large bombs.83 A bomb also hit the escorting Kiyoshimo, reducing her speed to 20 knots.

Vice Adm. Kurita was now convinced that to continue would risk the destruction of his entire force before it could reach the objective.84 He therefore decided to execute a temporary retirement and, at 1530, ordered his force to reverse its course to the northwest. At 1600 he originated a dispatch to Combined Fleet reporting this action and indicating that he deemed it best "to withdraw temporarily outside the range of enemy planes while awaiting the results of our other operations and standing by to cooperate as developments warrant "85.

For an hour and a half the force continued to retire until approaching nightfall brought safety from further air attacks. Vice Adm. Kurita was now expecting fresh instructions from Combined Fleet in response to his message of 1600, but since the retirement had put his force dangerously behind schedule in case Combined Fleet ordered execution of the attack as planned, he ordered his ships at 1714 to put about once more and head for San Bernardino.

[391]

The force was already one hour along on its new heading when, at 1815, the following message, addressed to all naval units engaged in the Sho-Go Operation, was received from the Commander-in-Chief, Combined Fleet:86

All forces will dash to the attack, trusting in divine assistance.87

Now committed to carry out the attack, Vice Adm. Kurita studied the situation in the light of meager reports received from the Ozawa and Nishimura Forces. A dispatch from Vice Adm. Ozawa, which had been received at 1603, confirmed the conclusion which Vice Adm. Kurita had drawn from the fierce air attacks on his force, namely that the decoy operation had not yet taken effect, and disclosed Ozawa's plan to divert enemy attention forcibly by a night attack.88 Actually, less than three hours after this dispatch was sent, a search plane from the enemy's northernmost task group had finally spotted Ozawa's carriers, starting a chain of reactions that soon brought the decoy plan into belated but effective operation.

From the Nishimura Force, now well into the Mindanao Sea, Vice Adm. Kurita received a dispatch at 2020 indicating that the force expected to penetrate through Surigao Strait into Leyte Gulf by 0400 on 25 October. This was much earlier than his own force, delayed by its retirement, could possibly reach the objective, and a revision of the coordinated timetable was clearly necessary. Vice Adm. Kurita therefore sent off a dispatch at 2145 modifying the attack plan as follows:89

1. The main body of the First Striking Force will pass through San Bernardino Strait at 0100, 25 October, and will then proceed southward down the east coast of Samar, reaching Leyte Gulf at about 1100.

2. The 3d Task Group will penetrate into Leyte Gulf as scheduled and will then join the main body at a rendezvous point ten miles northeast of Suluan Island 0900, 25 October.

Less than three hours later, the Kurita Force sped through San Bernardino Strait slightly ahead of schedule, debouching into the Philippine Sea at approximately 0035 on 25 October. Vice Adm. Kurita now headed around the northeastern tip of Samar, expecting to encounter enemy surface opposition at any moment. In fact, far less was in opposition than he knew, for the bulk of the enemy naval forces covering the northern approaches to Leyte Gulf was already speeding to attack the Ozawa group.90 The lure had begun to work.

Now, however, sudden disaster enveloped the southern prong of the attack. The Nishimura Force, ignored by enemy aircraft since the morning of the 24th, entered Surigao Strait at 0130 on the 25th, immediately becoming the target of continuous torpedo attacks by enemy PT boats. His ships maneuvering sharply to

[392]

avoid being hit, Vice Adm. Nishimura pressed on, making brief contacts at 0300 and 0315 with small enemy destroyer groups, which retired as the Japanese force opened fire.

At about 0320, a heavy torpedo attack struck the formation from both flanks, setting fire to the flagship Yamashiro, badly damaging the heavy cruiser Mogami, and sinking the destroyers Yamagumo and Michishio outright. Another destroyer, Asagumo, received heavy damage and dropped out of formation, sinking a few hours later.91 Yamashiro and Mogami, though damaged, moved on with the formation.

With the destroyer Shigure in the van, Yamashiro, Fuso and Mogami pressed on through the strait, dodging spread after spread of enemy torpedoes. At 0350 shells from heavy enemy surface units at the northern end of the strait began crashing into the formation. In five minutes, Mogami, heavily hit and afire, was forced to withdraw. The flagship Yamashiro sank a few minutes later under a hail of shells, and Fuso followed her to the bottom at about 0410. Shigure, well out in front, had sped on, toward the enemy until 0403, when she turned back to find that the rest of the force had vanished. Her commander decided to retire, and the destroyer ran south to become the sole survivor of the Nishimura Force.92

Vice Adm. Shima's Second Striking Force had meanwhile entered Surigao Strait at 0300, approximately two hours behind the 3d Task Group. Aboard his flagship, the heavy cruiser Nachi, Vice Adm. Shima overheard Vice Adm. Nishimura giving orders by radio-telephone for evasive action against torpedo attack, and before long enemy PT boats were attacking his own formation. At 0321 the light cruiser Abukuma was suddenly hit and fell out of formation. The rest of the force plunged on through heavy smoke drifting down from the battle ahead, and at 0420 the burning Mogami was sighted off the starboard bow.

At this juncture enemy targets were identified by radar off the port. Nachi and the heavy cruiser Ashigara immediately swung to starboard to fire torpedoes, and in executing this maneuver Nachi collided with the crippled Mogami, receiving underwater damage which reduced her speed.93 From Mogami, Vice Adm. Shima learned that both Yamashiro and Fuso had been sunk.94 Rather than sail into the evident enemy trap, he decided to execute a temporary withdrawal from the strait in order to regroup his strength. Laying a smoke screen, the force put about at 0450 and ran south.

Actually, the Surigao battle was now at an end. Vice Adm. Shima's Force, after safely emerging into the Mindanao Sea,95 underwent

[393]

two enemy air attacks, which indicated that a renewed penetration attempt in daylight would almost certainly risk destruction.96 All ships were running short of fuel, and the situation of Vice Adm. Kurita's main striking force remained unknown. At 0900, therefore, Vice Adm. Shima finally abandoned all thought of penetrating Surigao.97

The task of destroying the enemy invasion fleet in Leyte Gulf now rested solely on the shoulders of the Kurita Force, already heavily engaged off the coast of Samar.

Daybreak on 25 October found Vice Adm. Kurita's battle formation speeding south toward Leyte Gulf, now less than 100 miles away. At 0623 Yamato's radar screen suddenly showed the presence of enemy aircraft, and Vice Adm. Kurita ordered the force to shift to antiaircraft cruising disposition. The signal for this maneuver was being.sent out from the flagship when, at 0644, lookouts in her crow's nest spotted the masts of enemy ships on the horizon to the southeast. One minute later the contact was identified as a group of about six carriers in the act of launching their planes.

Since the enemy ships were erroneously identified as Fleet carriers, Vice Adm. Kurita believed that he had surprised an element of Admiral Halsey's fast carrier Task Force and was thus presented with an opportunity to strike a telling blow at the enemy's main carrier strength.98 He immediately decided to attack and ordered his ships to deploy for action. (Plate No. 93)

With the wind from the northeast, Vice Adm. Kurita set the mean course of deployment at 110 degrees so as to bring his force around to the north of the enemy group. This was to permit the attack to be delivered downwind, forcing the enemy carriers to run in that direction and preventing them from launching more of their aircraft. The maneuver, however, had the effect of partially nullifying the advantage in speed which Kurita's ships possessed and lengthening the time required to close.

The order to engage was given at 0658. Yamato opened fire with her 18-inch batteries, marking the first and only time in naval history that guns of this caliber were used in surface action. The enemy carriers, with their screening ships, began fleeing eastward, engaging in evasive action and laying down heavy smoke.99 The smoke and scattered rain squalls gave effective concealment, and Kurita's ships had to cease firing temporarily for want of targets.

[394]

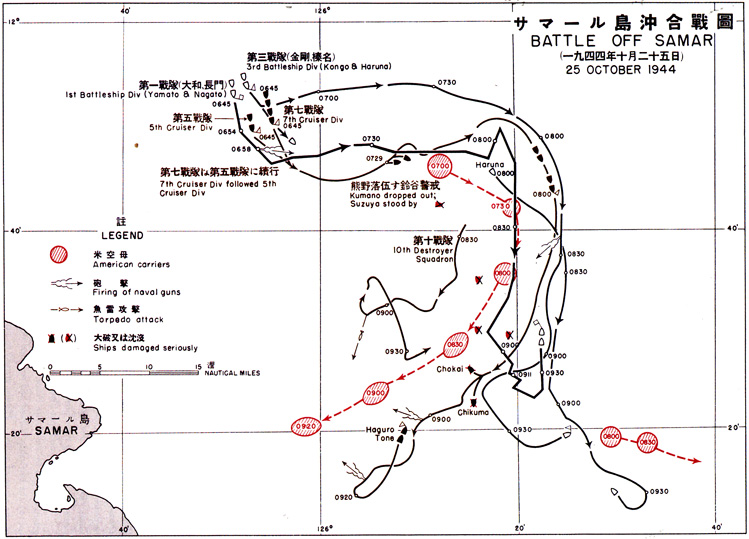

PLATE NO. 93

Battle off Samar, 25 October 1944

[395]

At 0710 planes from the enemy carriers began scattered attacks, causing superficial damage to some of the Japanese ships. Enemy escort vessels simultaneously dashed through the smoke and rain making torpedo runs. At 0725 Yamato drew first blood when she brought her main battery to bear on an enemy ship believed to be a cruiser, sinking her in two minutes. Almost immediately, however, an enemy torpedo caught the heavy cruiser Kumano, causing her to lose speed and fall behind the formation. At 0729 Vice Adm. Kurita released his cruisers, ordering all ships to pursue the enemy at full speed.

Still receiving intermittent air and torpedo attacks, the Kurita force gradually closed on the fleeing enemy ships, the direction of the pursuit swinging from east to south. At 0754 Yamato and Nagato were forced to maneuver to evade a spread of six torpedoes and fell several miles astern of the lead ships-the fast battle ships Haruna and Kongo and four heavy cruisers: Chikuma, Chokai, Tone and Haguro. The latter drove on at top speed, narrowing the range to about ten miles and gradually maneuvering the enemy into position for a torpedo attack by the 10th Destroyer Squadron.

At 0826 Kongo reported that she had knocked out one of the enemy carriers, and fifteen minutes later Yamato sank another ship believed to be a cruiser. From about 0830 enemy planes again began attacking in increasing numbers, concentrating on the cruisers which were leading the Japanese pursuit. Chikuma and Chokai were both hit and put out of action by 0900. At 0902 Kongo reported that she had sunk an enemy destroyer attempting a torpedo run on the outside of the formation.

Leaving the crippled Chikuma and Chokai astern, Tone and Haguro pressed on, closing the range to about six and a half miles by 0910.

The enemy ships were now running southwest, with Tone and Haguro taking them under fire from off the port beam and the 10th Destroyer Squadron attacking with torpedoes from the starboard.100 The complete destruction of the enemy appeared imminent.

Yamato's evasive maneuvers under torpedo attack had meanwhile put her still farther astern of the lead cruisers and battleships. Between the flagship and the scene of action lay rain squalls and several curtains of smoke, which made direct observation of the progress of the battle impossible. Due to overloaded battle circuits, radio reports from the ships engaged were fragmentary, and attempts at air observation by means of spot planes launched from Yamato netted little additional information due to enemy fighter interference.101 Vice Adm. Kurita consequently did not know that, beyond

[396]

the smoke and rain, his cruisers and destroyers had barely begun the destruction of a virtually helpless enemy.

Although ignorant of the situation in the van, Vice Adm. Kurita was forced both by events and by consideration of the basic mission to make a rapid decision concerning his next move. At this point enemy air attacks, steadily mounting in frequency, had inflicted considerable damage to the First Striking Force. In addition-and even more important-there was a danger that further continuation of the fight would exhaust the fuel needed for execution of the primary mission-a penetration into Leyte Gulf. Vice Adm. Kurita still labored under the misapprehension that he was pitted against a group of Admiral Halsey's fast carriers and that it would be impossible to close the enemy with his main battle strength. All these considerations impelled the First Striking Force commander to seek an early opportunity to disengage.

The moment now seemed propitious. Knowing that the 10th Destroyer Squadron had already launched its heavy torpedo attack on the fleeing carriers and estimating that the cruisers out of sight in the van had, after a two hour action, inflicted devastating damage on the hapless enemy, Vice Adm. Kurita decided to reassemble his force for the final penetration attempt. At 0911 the flagship began sending out the order to break off action and reassemble on a northerly course. By 0930 the order had reached all units, scattered over 25 miles of ocean, and the cruisers and destroyers hammering at the fleeing enemy carrier group imme diately put about to the north. The reassembly, carried out under sporadic air attacks, was not completed until 1030.102

Vice Adm. Kurita now had an opportunity to evaluate the results of the battle on the basis of initial reports made by the returning units. Three or four enemy fleet carriers were believed to have been sunk, in addition to two heavy cruisers and a destroyer also sunk and several other units heavily damaged.103 These optimistic figures totaled up to a substantial victory, but the cost had not been light.

The heavy cruiser Kumano and destroyer Hayashimo, both heavily damaged, were retiring independently. Chikuma and Cbokai, mortally wounded by enemy aerial torpedoes and bombs, remained on the scene of action with two destroyers standing by.104 At 1114 the heavy cruiser Suzuya was added to the casualty list when an enemy bomb hit started uncontrollable fires.105 Thus, for the final thrust into Leyte Gulf, Vice Adm. Kurita could muster but 15 of his original 32 ships-four battleships, two heavy cruisers, two light cruisers and seven destroyers.

The regrouping of his units completed, Vice Adm. Kurita at 1120 gave the order to change course to the southwest for the crucial run into the gulf. Some members of his staff, however, were now of the opinion that the penetration attempt should be abandoned, and discussion continued even as the force headed toward its final objective. Vice Adm. Kurita now had to make the most fateful and dramatic decision of the entire Leyte sea battle.

The background against which this decision was finally taken was as follows: Dispatches from Vice Adm. Ozawa reporting that the

[397]

decoy force was under heavy attack by enemy carrier planes had not reached Vice Adm. Kurita, who therefore had no certainty that the luring operation had been effective. On the other hand, enough was now known of the events which had occurred in Surigao Strait to make it plain that the southern prong of the attack had failed, and that any penetration into Leyte Gulf would have to be made by Kurita's depleted force single-handed.

The question of time was of even more vital importance. The engagement off Samar had, in conjunction with the time consumed in regrouping his scattered force, so retarded Vice Adm. Kurita's advance toward the gulf that it would be mid-afternoon before he could reach the objective. With ample warning of his approach, it seemed highly probable that the enemy would have evacuated his transports and supply ships from the gulf.

There were also indications that the enemy was mustering strong forces for the defense of the gulf. Radio intercepts revealed not only that enemy carrier aircraft were concentrating on Tacloban airfield, but that powerful enemy surface reinforcements would reach the Leyte area within about two hours. Without any visible support by friendly air forces,106 it seemed likely that a thrust into the gulf would therefore be not only fruitless but suicidal.

Reports had meanwhile been received from Southwest Area Force to the effect that an enemy carrier task force had been spotted northeast of Samar. Vice Adm. Kurita and the majority of his staff, increasingly dubious of the prospects of success in a thrust into Leyte Gulf, estimated that a more effective blow could be struck by running north to deliver a surprise attack on the newly-reported enemy carrier force.107

At 1236, with the entrance to Leyte Gulf only 45 miles away, Vice Adm. Kurita made his definitive decision. Ordering his force to put about to the northwest, he radioed Combined Fleet and all other naval commands concerned that the penetration of Leyte Gulf had been abandoned, and that he was proceeding north to seek battle with an enemy task force, after which he would retire through San Bernardino Strait.108

Enemy carrier planes continued to harass the formation during the afternoon but inflicted no serious damage. Just before sunset, Vice Adm. Kurita's ships reached the area in which the enemy task force had been reported, only to find that the force had vanished.109 With nothing to attack and his destroyers beginning to run short of fuel, Vice Adm. Kurita ordered his force to turn west and run for San Bernardino.

The message communicating Kurita's last-minute decision to abandon the penetration of Leyte Gulf caused disappointment and indignation in Combined Fleet headquarters. To Admiral Toyoda and his staff, Kurita's action, especially after the success reported in the battle off Samar, seemed tantamount to throwing away an excellent opportunity. With the First Striking Force rapidly steaming north, it was recognized that a fresh order to execute the attack

[398]

PLATE NO. 94

Battle for Leyte Gulf, Phase II, after 0600 25 October 1944

[399]

as planned could probably not be carried out. Nevertheless, hoping to spur Vice Adm. Kurita into a more positive course of action, Admiral Toyoda at 1647 originated the following dispatch order:110

1. If the opportunity arises, the First Striking Force will tonight attack and destroy remnants.111 Other forces will cooperate with this attack.

2. If no opportunity presents itself, the Task Force Main Body and the First Striking Force will return to their supply bases, such movement to be carried out as ordered by the respective commanders.

By the time this message was received by Yamato at 1925, the First Striking Force was about to begin its run through San Bernardino Strait. Vice Adm. Kurita, since he had failed to make contact with the reported, but actually non-existent, enemy task force northeast of Samar, now saw no hope of carrying out a night attack, and the fuel situation of his ships was becoming steadily more critical. He therefore decided to continue on to Brunei.

Vice Adm. Kurita steamed away from the scene of battle unaware that the naval air forces,112 resuming their offensive on the morning of the 25th, had actually scored results which would have facilitated his penetration into Leyte Gulf. Kamikaze units of the First Air Fleet, in the first real demonstration of their effectiveness, had heavily hit one enemy carrier group to the east of Surigao Strait,113 following this up with a damaging attack on the group with which the Kurita Force had just broken off action east of Samar.114 Second Air Fleet units based at Legaspi also flew repeated regular sorties throughout the day, but these achieved little or no success.115

Vice Adm. Kurita also did not know that the Ozawa Force had so effectively fulfilled its sacrifice mission that it had lost a total of seven ships, including all four of its carriers, during 25 October. At 0630 of the fateful day, Vice Adm. Ozawa, after rendezvousing with Rear Adm. Masuda's advance guard, turned his force northward and ran away from the Philippines at top speed in order to lure the enemy after him. At 0815, just at the height of the critical battle off Samar, planes from Admiral Halsey's fast carriers, which had sped northward during the night, began attacking Vice Adm. Ozawa's

[400]

ships in the last dramatic act of the battle for Leyte Gulf.

Between o815 and 1700 wave after wave of enemy planes drove in to pound the empty Japanese carriers and their protecting units. In the first attack the carrier Chitose and destroyer Akitsuki were sunk, the light cruiser Tama seriously damaged,116 and minor damage received by other ships, including Vice Adm. Ozawa's flagship, the regular carrier Zuikaku. During this action, Vice Adm. Ozawa radioed to Vice Adm. Kurita that the decoy force was under attack by huge numbers of enemy carrier planes, but this message was never received.

By noon the light carrier Chiyoda had received such heavy damage that she had to be abandoned.117 Meanwhile, communications on the Zuikaku had broken down due to bomb damage, and at 1100 Vice Adm. Ozawa transferred his flag to the light cruiser Oyodo. Zuikaku, the last surviving carrier which had taken part in the raid on Pearl Harbor, went down under heavy enemy attack at 1414. Zuiho followed her to the bottom at 1527.

Having knocked out all of Vice Adm. Ozawa's carriers, enemy planes now began concentrating their attacks on the battleships Ise and Hyuga. Both ships were rocked by scores of near misses but escaped with only minor damage. Darkness finally brought respite, and the battered remnants of the decoy force, leaving three destroyers behind to pick up survivors, withdrew northward.118

The main action in the historic battle for Leyte Gulf was now ended, but still further losses were sustained by the retiring forces as they made their way back to base under continuing enemy air attacks.119 These losses brought the total destruction suffered by the Fleet to four carriers, three battleships, six heavy cruisers, three light cruisers and nine destroyers, representing almost half the participating tonnage and 34.4 percent of Japan's total naval surface tonnage at the start of the Leyte battle.120

Exaggerated estimates of the losses inflicted on the enemy served, temporarily at least, to obscure the disastrous nature of the setback suffered in the Leyte battle.121 It nevertheless

[401]

was soon apparent that the sea-air phase of the Sho-Go plan to crush the enemy invasion of the Philippines had failed of its objective.

Deterioration on Eastern Leyte

On Leyte itself, the ground situation had deteriorated rapidly during the period of the vital sea and air operations. In the northern beachhead, although the 33d Infantry continued to hold its key hill positions west and northwest of Palo, blocking an enemy thrust inland over the Palo-Carigara highway, the enemy on 22 October began driving in the makeshift Japanese defenses west of Tacloban and at the same time pushed south from Palo to widen the beachhead to the Binahaan River. In the south, a powerful enemy thrust from Dulag toward the Burauen airfields was simultaneously gaining momentum, the spearhead of the attack reaching a point three miles west of Dulag by 22 October. (Plate No. 95)

Watching these developments from his com mand post at Dagami, Lt. Gen. Makino decided on the night of the 22nd that an immediate realignment of the southern sector forces was imperative. Since commitment of the main strength of these forces in frontal resistance to the enemy drive along the Dulag-Burauen road would leave the flank of the 9th Infantry in the Catmon Hill-Tanauan coastal sector

dangerously exposed, he ordered the 2oth Infantry to disengage along the road and shift its main strength northward to the Hindang area, where it was to occupy prepared positions and make ready for a possible counterattack on the enemy flank. One element of the regiment was to be left at San Pablo to join ground personnel of the 34th Air Sector command in defending the Burauen group of airfields.122

Swift developments, however, soon rendered this plan ineffective. Weakened by the shift of the 20th Infantry's main strength, the right-flank positions on the Dulag-Burauen road gave way under heavy enemy assault, and by 24 October the easternmost of the three Burauen airfields, near San Pablo, had been overrun. At the same time, the main body of the 20th Infantry, moving into its new positions in the Hindang sector, was suddenly hit and driven into retreat by enemy elements which had infiltrated inland, by-passing the 9th Infantry strongpoint on Catmon Hill.123

Lt. Gen. Makino now recognized that the loss of the eastern coastal plain could not be averted and laid plans to pull back the division main strength to rear-line positions in the mountains west of Dagami and Burauen, with the 33d Infantry to continue covering the divi sion left flank north of the Binahaan River.124 Orders for the execution of the withdrawal were transmitted to the 9th and 20th Infantry Re-

[402]

PLATE NO. 95

Leyte Campaign, 21 October-1 November 1944

[403]

giments-the latter already retreating from Hindang-on 26 October. The 9th Infantry was directed to start evacuating its Catmon Hill positions after the 27th.125

In the meantime the situation throughout the southern sector had deteriorated still further. By 27 October, enemy forces pushing on from San Pablo had taken both North and South Burauen airfields, as well as Burauen itself, placing all five major airfields on eastern Leyte in enemy hands.126 Other enemy elements were hammering at the 9th Infantry's secondary positions at Tabontabon, three miles northwest of Hindang, while on the coast a juncture of enemy forces in the vicinity of Tanauan had linked the northern and southern beachheads.