CHAPTER XVII

TOKKO "SPECIAL-ATTACK"

The resort to suicide weapons and tactics on an organized and ever-increasing scale in the battle for the Philippines was grim evidence of Japan's mounting desperation in the struggle to halt General MacArthur's penetration of the inner defenses of the Empire. Such methods reflected the strong determination of the Japanese High Command and fighting services to overcome, at any cost, the growing disparity in material fighting power.1 This type of warfare à outrancé, which so vividly expressed the ardent patriotism of the Japanese soldier, was termed tokko, or " special-attack", a generic name covering all suicide operations on land, sea, and in the air.2

Although special-attack methods had been seriously discussed by Army and Navy field commanders as early as the fall of 1943, they were not employed to any significant extent until the American invasion of Leyte in October 1944. By the end of the Philippines campaign, however, suicide attack, particularly in the air, had become a major combat technique which later played an even more prominent role in the battle for Okinawa and in the defense plans for the Homeland.

The concept of suicide attack developed gradually under the impact of the Army's successive reverses in the Solomons and in New Guinea between 1942 and 1944 and the Navy's inability to halt the enemy's offensive across the Central Pacific. By the time of the invasion of Leyte, the war situation had become so critical that the Japanese High Command was finally forced to sanction and then actively to push the organization of tokko units as virtually the last effective means of stemming the Allied tide.

"Special-attack" found partial expression during the Papuan Campaign in the winter of 1942-43, when raider squads were thrown into night assaults in a desperate attempt to stall the Allied drive on Buna.3 The ground troops

[561]

PLATE NO. 137

Airborne Raiding Unit on Leyte

[562]

resorted to this type of offense when weakness in numbers and weapons rendered conventional methods of attack ineffectual. These raider units, however, were not suicide forces in the strict sense; they were hit-and-run "commando" groups which were ordered out with the possibility and expectation that at least some would return. The compelling reason for their employment was nevertheless the same as that which later produced the Kamikaze-the necessity of achieving maximum results at a minimum cost in materiel and men.

By early 1943, the Japanese Air forces had lost their initial superiority. Slowly weakened by irreplaceable losses in skilled pilots, they found themselves increasingly incapable of effective opposition. The air war over New Guinea underlined the ever-widening difference in the strengths of the opposing forces, and emphasized the superiority of American aircraft and combat training. Before the end of 1943, the Air forces were definitely on the defensive,4 and the Japanese found it impossible to resume the initiative at any point.

Under these conditions, front-line airmen who were under constant Allied assault began to feel that orthodox combat tactics were futile against the enemy's more powerfully built and more heavily armed aircraft, particularly the B-17 "flying fortress." Pilots arrived at the conclusion that, barring the unlikely development of a radically new scientific weapon, a superior fighter plane, or a novel defensive technique, the only solution lay in reliance on suicide tactics.5

Influenced by this widespread feeling of desperation at the front, the Army Section of Imperial General Headquarters, in May 1944, initiated informal discussions on the subject of organizing a special-attack corps within the Army Air force. At the same time, however, technical studies were begun with a view to devising improved combat techniques and ordnance, and every effort was made to perfect the use of existing weapons.

Following the disastrous Philippine Sea Battle of 19-20 June 1944, Navy Air force officers also began to study special-attack techniques more seriously. This stunning defeat not only cut heavily into the reservoir of skilled fliers which the Navy was trying to rebuild but also gave a fresh demonstration of the weakness of the Japanese air arm. An increasing number of pilots, and on one occasion a flag officer, urged the Navy High Command to consider the adoption of suicide-attack methods, but their recommendations were not acted upon at that time.6

[563]

Experimentation with Tokko Tactics

With the formulation of the Sho-Go Operation plans in July 1944, the Army quietly moved ahead with blueprints for the creation of special-attack air units. By early August plans covering the organization, training, and tactics of such units were completed. Volunteers were being recruited from Army air schools to receive instructions at special training centers7 and aircraft especially designed for use by tokko units were in various stages of planning and production.8

The Navy Air forces, meanwhile, continued to adhere to orthodox attack methods. Some Navy fighter pilots were being trained in skip-bombing technique, and the most competent pilots of regular bombing and torpedo attack squadrons were placed in the "T" Attack Force, a newly organized unit designed to carry out attacks on enemy ships at night or under adverse weather conditions.

Beginning in September 1944, the Army and Navy began a series of studies to determine the amount of air power and the type of tactics required to smash an Allied invasion fleet. The Army Air force shortly thereafter began actual tests in home waters. Staff studies were made simultaneously by Army and Navy commanders in the Philippines, where the next enemy blow was expected to fall.

The tests conducted by the Army showed conclusively that flying personnel were inadequately trained to make orthodox high-level bombing an effective means of attack. Actual combat experience had also demonstrated that although skip-bombing obtained far better results, it involved prohibitive losses in planes and pilots because the enemy's naval antiaircraft defenses were so highly perfected. Skip-bombing, moreover, required experienced air crews, of which the Air forces were painfully short.

These studies and experiments supported a growing conviction that suicide or crash attack was the best means of ensuring maximum results at minimum cost in planes and pilots. The effectiveness of this method had already been demonstrated on a number of isolated occasions prior to the summer of 1944.9 Many high staff officers were convinced that it was

[564]

the only solution in view of the insufficient training which most pilots were then receiving. Crash tactics, moreover, required relatively little instruction.10

While these views generally prevailed in lower Army and Navy echelons,11 the employment of suicide techniques on a large scale by the Air forces was not yet officially sanctioned by either the Army or Navy High Commands; as late as mid-October, Imperial General Headquarters had not yet issued any formal orders directing the use of tokko tactics.12

This was the situation when the incursion of an enemy carrier task force into the Ryukyus-Formosa area precipitated the critical air battle off Formosa. On 15 October, in the closing phase of this engagement, Rear Adm. Masabumi Arima, Commander of the 26th Air Flotilla in the Philippines, set an example of suicidal bravery by attempting to crash his torpedo bomber into an enemy carrier.13 This act of self-sacrifice by a high flag officer spurred the flying units in forward combat areas and provided the spark which touched off the organized use of suicide attack in the battle for Leyte.

The underlying compulsion which brought the first organized air special-attack units into being, however, came from the crucial state of unpreparedness in which the enemy invasion of Leyte caught the Air forces in the Philippines. Mass air strikes against the invasion forces had been envisaged under the Sho-Go Operation plans, but the First Air Fleet found itself with fewer than 50 operational aircraft, mostly fighters and a few bombers, as a result of enemy carrier attacks. The Fourth Air Army had less than 100 planes, and its strength was widely dispersed. The Second Air Fleet, which contained the bulk of the Navy's Air forces, had suffered heavy losses in the Formosa air battle and had not yet begun its redeployment to the Philippines.

On 17 October, as the enemy fleet began moving into Leyte Gulf, Vice Adm. Takijiro Onishi arrived in Manila to assume command of the First Air Fleet. On the following day, the Sho No. 1 Operation was activated. Its success hinged on a decisive employment of air power. Determined to secure maximum results

[565]

with the handful of planes at his disposal, Admiral Onishi decided late in the night of 19 October, a few hours before formally assuming command, to create a suicide corps on a volunteer basis within the First Air Fleet.

This corps, christened the Kamikaze Special-Attack Corps, was originally made up of 24 volunteer fliers selected from the 201st (Fighter) Air Group, stationed in the Manila area.14 Assembled at Clark Field, the fliers were organized into four units, each composed of six pilots and bearing a special name designation. The aircraft allotted for their use were Zero fighters stripped of radio equipment, armament, and all but essential flying instruments and fitted to carry a 250-kilogram demolition bomb underneath the fuselage. On attack missions, the suicide units were to be led to the target by guide planes and covered against enemy interception by fighter escort. Crash attacks were to be executed only when reasonably certain of hitting enemy carriers or major task force units.15

The initial sorties of the Kamikaze units on 21 October were largely unsuccessful. Three of the units took off from Mabalacat, near Clark Field, to attack enemy task forces reported operating to the east of Luzon, but were unable to locate the targets. The fourth, which had advanced to a base on Cebu the preceding

day, was preparing to sortie against enemy naval forces in the vicinity of Leyte Gulf when a sudden strike by enemy planes on the morning of the 21st destroyed all six suicide aircraft on the ground. Three reserve fighters were undamaged, however, and it was decided to carry out the mission with these planes. Two of the fighters were unable to execute attacks because of unfavorable weather and were forced to return to their base, but the third was believed to have crash-dived into an enemy warship.16

The first real display of Kamikaze effectiveness was given on 25 October, the second day of the all-out air offensive launched in conjunction with the surface force attack toward Leyte Gulf. One unit flew from Davao to attack an enemy carrier group east of Surigao Strait; another shortly thereafter struck at the same carrier force which had just escaped destruction by Vice Adm. Kurita's warships in the battle off Samar. In the latter strike, four Kamikaze planes were reported to have executed successful crash attacks. On 26 October, an enemy carrier group east of Surigao Strait was the target of yet another suicide attack, in which two carriers were reported hit.17

The small Kamikaze corps organized by Vice Adm. Onishi was originally intended as a temporary expedient to meet an express emergency. The unfavorable trend of the Philip-

[566]

PLATE NO. 138

Departure of Special-attack Unit from Homeland Base

[567]

pines Campaign, however, forced an increasing reliance upon suicide tactics. This tendency was spurred by heavy aircraft losses, an inadequate flow of air replacements, and a steady deterioration in the quality of pilots arriving at the front.

As the original Kamikaze corps was expended, new units were quickly organized in the First Air Fleet with volunteers drawn from regular tactical units and replacement groups.18 Soon any flight of planes on a suicide mission was called a special-attack unit. Usually the planes went out in groups of two or three, accompanied by an equal number of fighter escorts and a single guide plane. They took off at dawn and at other hours when they were the least liable to interception.

By the end of October, special-attack units of the First Air Fleet had carried out twenty separate missions with from one to eight planes participating. Twenty-eight aircraft were credited with having crashed into their objectives, principally enemy naval vessels in the waters east of the Philippines.

The Second Air Fleet, which deployed to the Philippines on the eve of the big air offensive of 24-25 October, at first did not resort to the formation of Kamikaze units, but as combat losses pared down its strength and orthodox methods failed to achieve adequate results, it soon found itself obliged to follow the example of the First Air Fleet. By the end of the first week in November, planes of the Second Air Fleet's 221st Air Group were executing crash attacks on enemy ships in Leyte Gulf. Between 1-15 November, the First and Second Air Fleets-at this time operating together as the First Combined Base Air Force-carried out 21 suicide missions using a total of 71 Kamikaze planes. During this period, 19 aircraft were reported to have crashed successfully into their objectives.19

Although the lead had been taken by the Navy Air forces, the Army was not long in following suit. With the activation of the Sho No. 1 Operation, Imperial General Headquarters ordered to the Philippines the first of the specially trained and equipped Army tokko units which had been organized in the Homeland during the summer of 1944. The Banda and Fugaku units, each with twelve special-attack bombers, reached Philippine bases too late to participate in the 24-25 October air offensive and were held in reserve by Fourth Air Army for use only on the most vital missions.20 They finally went into action for the first time on 12-13 November.

Eighteen additional special-attack units of the same type, with a total of 216 aircraft, were ordered to the Philippines during November. Meanwhile, under High Command authorization given early in November, Fourth Air Army organized provisional tokko units within its regular tactical forces already in the Philippines. The strength and composition of these units were determined by the regimental commanders, and they were to use ordinary fighter and fighter-bomber aircraft with bombs attached to the underfuselage.

Although the appearance of the tokkotai exerted no appreciable effect on the outcome of the battle for Leyte, the reason did not lie in a lack of effectiveness. Reported results for the Leyte campaign showed that 30 per cent of

[568]

the special-attack planes which actually attempted crash attacks hit their objectives, a rate of accuracy far higher than that achieved by orthodox bombing. The ratio of aircraft losses to damage inflicted on enemy ships was also lighter. During the first three weeks, 30 Army tokko planes were lost in attacks which reportedly sank or damaged 23 enemy vessels, as compared with 24 aircraft lost in regular bombing attacks which were reported to have sunk or damaged only 6 Allied ships.21

But even suicide methods, however destructive, could not overcome the enemy's decisive superiority in numbers. His carrier task forces were still able to send preponderant air strength against Japanese bases throughout the Philippines. About one-third of the planes, sent as reinforcements from the Homeland, were destroyed on the ground even before they could go into action.22 Moreover, the element of surprise which heightened the effectiveness of the tokkotai in the initial period of their activity was soon gone. The enemy took prompt steps to strengthen the air cover and antiaircraft defenses of his ships, so that more and more special-attack aircraft and escorting fighters had to be sent out on each mission in order to achieve worthwhile results.

Special-attack nevertheless remained the sole means whereby the Japanese Air forces could pit their inferior strength against the enemy with any degree of success. By 15 December, the day the enemy invaded Mindoro, more than half the air strength deployed in the Philippines was being committed to tokko combat. By the end of the same month, Army special-attack units were frequently flying to the target without fighter escort, and virtually anything that could leave the ground, including trainer aircraft, was being fitted for crash missions.

The tokkotai made their final mass effort of the Philippines Campaign in January 1945 against the enemy's Luzon invasion forces. On 5 January, sixty Army special-attack planes struck the huge invasion convoy as it moved west of Subic Bay and inflicted considerable damage. The effort reached maximum intensity on the following day, when both Army and Navy aircraft joined in day-long attacks on enemy ships moving into Lingayen Gulf. By 7 January, however, the Air forces had sustained such heavy losses that their offensive power was spent.

For a brief period thereafter, a small number of Army suicide planes continued to operate from hidden fields on northern Luzon, sortieing in groups of two or three planes for sporadic attacks on enemy re-supply shipping. By mid January even this meager activity had ceased, and the Japanese air effort in the Philippines came to an end.

During the entire period of the Philippines Campaign, Fourth Air Army sent out about 400 special-attack planes on 61 missions, while Kamikaze of the Navy's First Combined Base Air Force flew 436 planes on 107 missions. The results officially reported for these attacks were 154 vessels of all types hit by Army planes and 105 by naval Kamikaze.23 While the frequent difficulty of ascertaining exact results

[569]

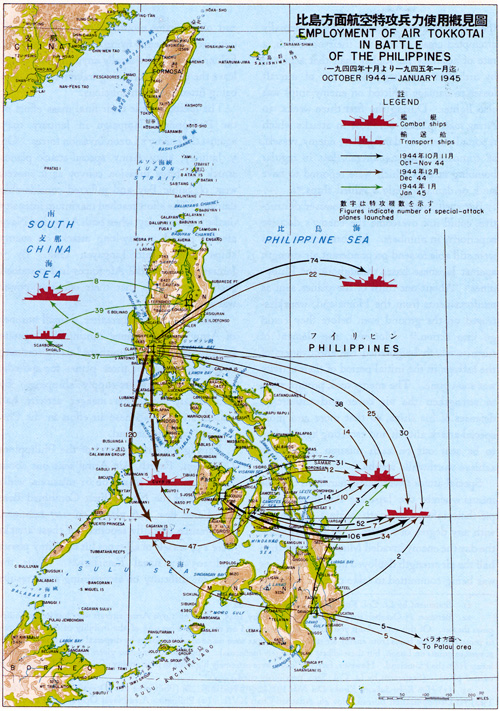

PLATE NO. 139

Employment of Air Tokkotai in Battle of Philippines, October 1944-January 1945

[570]

PLATE NO. 140

Surface Raiding Unit Dares Desperate Ramming

[571]

made these figures subject to unavoidable error, there was no question that the sharp sting of the special-attack forces had hurt the enemy.24 (Plate No. 139)

Air tokko was by far the most spectacular and extensive form of special-attack to emerge during the struggle for the Philippines, but it was not the only manifestation of the suicide technique whereby the Japanese sought desperately to change the tide of battle. Both the Army and Navy resorted to other forms of special-attack, all of which were designed to obtain maximum results with rapidly dwindling resources.

The use of small airborne raiding units in the abortive attempt of November 1944 to regain control of the Burauen airfields on eastern Leyte was the only example of the application of special-attack principles to airborne ground troops during the Philippines Campaign.25 Air force weakness barred further operations of this kind in the battle for Luzon, but the Burauen airborne assault furnished the prototype for a similar suicide operation carried out in May 1945 during the final stage of the Okinawa Campaign.26

The Luzon battle witnessed the first use of another special-attack weapon designed to offset Japan's poverty in regular surface combat forces. This new weapon was the suicide crash boat, a small craft of light plywood construction manned by a single navigator and fitted with depth charges to be dropped directly alongside an enemy vessel or rammed into it without release from the attacking craft.27 Such boats were specially designed for close-in attacks on enemy invasion craft anchored off landing beaches.

Surface raiding units equipped with crash boats were organized and trained by both the Army and Navy during the summer of 1944 in preparation for the defense of the Philippines. Plans formulated in August called for the construction of Navy surface raiding bases at

[572]

Davao and Sarangani Bay on Mindanao, at Tacloban on Leyte, and at Lamon Bay on Luzon.28 The boat units and maintenance personnel began arriving on Luzon early in September, but the projected bases in the southern and central Philippines were not completed in time to permit deployment before the invasion of Leyte. On Luzon the surface raiding forces were concentrated at four main points of anticipated invasion-Lingayen Gulf, Manila Bay, Batangas, and Lamon Bay.29

On only two occasions during the defense of Luzon did these forces go into action on a large scale, and, in both instances, they proved ineffectual. About 70 Army surface raiding boats launched a mass attack against enemy invasion shipping in Lingayen Gulf on the night of 9-10 January 1945, but were unable to disrupt landing operations.30 The Navy's Shinyo boats based in Manila Bay went into action for the first and only time on the night of 15 February against enemy warships anchored in Mariveles Bay, on Bataan Peninsula. All participating craft were expended in both these raids.

Although devised long before the general adoption of special-attack weapons and less suicidal in nature than either the Kamikaze plane or the crash boat, the Navy's midget submarines also fitted naturally into the pattern of tokko warfare.31 Ten of these craft, operating from bases in the central and southern Philippines, harassed northbound enemy convoys in the Mindanao and Sulu Seas during December 1944 and January 1945 until they finally met their doom.

The Navy's Kaiten, a one-man piloted torpedo which was first put into production in September of 1944, was more clearly a full-fledged suicide weapon. These torpedoes were designed to be carried on the deck of a parent submarine, generally four to one parent craft, and released within range of the target. The operator, seated in the center of the torpedo, then steered his explosive missile directly to the objective and certain death. The Kaiten were first thrown into action on 20 November 1944, when 8 were employed in a surprise attack on enemy carriers and battleships at Ulithi Anchorage. In January and February 1945, 28 more were used in operations against enemy naval bases at a number of scattered points in the Central and south Pacific.32

Although about 450 Kaiten were produced,

[573]

including some improved models, the Navy's plans for using them extensively never materialized. Between May 1945 and the end of the war, they had been employed on only eleven occasions, achieving a total of 18 reported hits on enemy vessels.33

The institution of special-attack weapons and methods in air and sea warfare was paralleled by no striking innovations in the field of regular ground combat. Nevertheless, as the Philippines Campaign progressed, there was a tendency toward an increasing reliance on infiltration and raiding tactics of a suicidal nature. During the defense of Luzon, Fourteenth Area Army also employed suicide antitank units which endeavored to destroy enemy armor by close-in attacks with grenades and lunge mines.

The tokkotai came into being during the final phase of the Pacific War because of a compelling necessity to devise some counterweight to the overwhelming enemy superiority in all aspects of military power. The resort to suicide methods on so large a scale, however, would never have been possible but for a single factor-the deeply inculcated spirit of patriotic self-sacrifice which characterized the Japanese soldier and sailor and which was reflected in the psychology of the nation as a whole.

It was this spirit, the product of centuries of religious and moral training, that brought forth in ample number volunteers for every special-attack unit or mission; that led Japanese troops, often starving and cut off from all hope of succor, to fight on rather than surrender; and that spurred the nation to still greater efforts despite successive defeats, mounting hardships and growing doubt of ultimate survival.

Although the tokkotai had not proved equal to the task of turning back the enemy in the Philippines, their heroic example bolstered the determination of the people at home and gave an impetus to the still wider adoption of special-attack methods. These suicide techniques were to play a large role in the subsequent defense of Okinawa, and under plans which the High Command began formulating early in 1945, were to constitute the backbone of the final battle to turn back the anticipated invasion of the Homeland.

[574]

Go to

Last updated 1 December 2006 |