CHAPTER XIX

Potsdam Germany

The occupation entered the quadripartite phase shortly after noon on 30 July 1945 when the Allied commanders in chief assembled in the conference room of the U.S. Group Control Council headquarters in Berlin for their first meeting as the Control Council. At the same time, Truman, Stalin, and Clement Attlee, who had replaced Churchill two days earlier, were about to begin their final meetings at the Cecilienhof in Potsdam. Because the conclusion of the Potsdam Conference had been delayed somewhat by the change in the British government and by an illness of Stalin's, the Control Council could not yet transact any significant business. The Russians had tacitly made their participation in the four-power body dependent on a satisfactory -for them- outcome of the talks among the heads of state; and Zhukov, even at this late date, would agree only to set a schedule for future meetings (on the 10th, 20th, and 30th of each month) and to establish a rotating chairmanship, with Eisenhower taking the chair for the first month. When Eisenhower proposed activating the control machinery, which was composed of the Co-ordinating Committee (formed by the deputy military governors) and the directorates, the bodies that would do the day-to-day work of running Germany, Zhukov demurred. He would have to get his government's ratification, he said.

The Potsdam Conference protocol, signed on 1 August, gave the Control Council its charter and it missions. The commanders in chief, individually in their own zones and jointly as members of the Control Council, would exercise supreme authority in Germany. They would also, as directed by their governments, lie responsible for developing occupation policies; the European Advisory Commission would be dissolved.1 In addition to administering and observing agreed policies, such as demilitarization, decentralization, and denazification, the Control Council received two missions: one was crucial from the US point of view, the other from the Soviet point of view. The first mission, which President Truman had put before the conference at its opening session, was to administer Germany as an economic unit.2 Truman, no advocate of the Morgenthau Plan, had accepted Secretary of the Treasury Morgenthau's resignation on 5 July after refusing to have him at Potsdam.3 The President's own thinking was closer to that of Stimson, who had written to him the day before the conference opened, "The problem which presents itself . . . is how to render Germany harmless as a potential aggressor, and at the

[342]

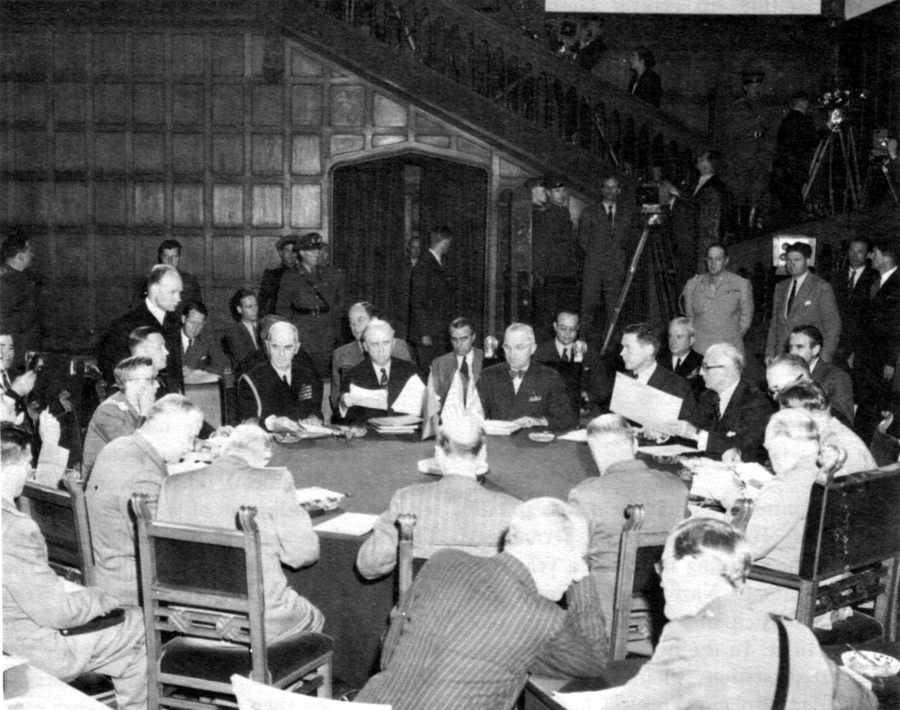

SESSION AT POTSDAM. President Truman is at the far side of the table with Secretary Byrnes and Admiral Leahy on his right.

same time enable her to play her part in the necessary rehabilitation of Europe." 4 To accomplish both purposes, Stimson had urged treating Germany as an economic unit and stimulating her peacetime production while eliminating her war potential. The President, no doubt, wished also to avoid the political consequences of a divided Germany as well as the economic consequences to the American taxpayer of having to maintain a zone that had no prospect of being able to support itself. As an earnest of US commitment to the principle of economic unity, he was willing to assume a share in financing supply imports for all four zones on a basis to be determined by the Control Council; and on 29 July, he assigned the procurement and financing responsibility for such a program to the War Department.5 The conference protocol accepted economic unity as a principle and charged the Control Coun-

[343]

cil with setting up central German departments for finance, transport, communications, foreign trade, and industry. The predominant -possibly exclusive- Soviet concern was with reparations, not from its own zone where it was already collecting on a scale to suit itself but from the western zones. After long, frequently sharp debate, the conference gave the Control Council the second mission of establishing a level of industry for Germany, that is, determining how much of its existing productive capacity the country would need to subsist without being able to threaten the peace again. Any excess would become available for reparations, with 25 percent from the western zones going to the Soviet account.6

The Control Council held its second meeting on 10 August in its permanent quarters, the building in which a year earlier the infamous Nazi People's Court had tried the participants in the 20 July plot against Hitler. In the high-ceilinged, newly redecorated sessions chamber where the Nazi judge, Roland Freisler, had handed down his sentences, the military governors, flanked by their deputies, political advisers, and secretaries, took seats around a large oval table. Interpreters sat behind each delegation, and recorders occupied tables in the corners of the room. The resolution activating the control machinery was quickly adopted, and the meeting proceeded in an atmosphere of great personal amiability; but when the responsibilities acquired as a result of the Potsdam Conference came under consideration, the French member, Gen. Pierre Joseph Koenig, announced that he would have to "reserve his position" with regard to the Potsdam decisions.7

The subsequent meetings were conducted, in the words of one observer, with "few dissensions, all things considered," but with "a tone of fatality." 8 France, not having been represented at Potsdam, did not regard itself as bound by the agreements made there; and in the Control Council, General Koenig vetoed the proposed central economic agencies one by one as they came up, eventually including also a proposal to establish a post office department and a law allowing German trade unions to organize nationally. In early October, Gen. Charles de Gaulle told the French press: "France has been invaded three times in a lifetime. I do not want ever to see the establishment of a Reich again." 9 The Russians seemed to want to see the economic agencies created, but when the War and State Departments authorized Clay, in October, to enter into a trizonal arrangement, neither the Russians nor the British would agree.10 The US representatives returned then for almost another year to the futile task of trying to secure economic unification on quadripartite terms; and the Control Council remained, as Clay predicted it would, a negotiating rather than a governing body, capable of enacting legislation but completely dependent on the separate zonal authorities for enforcement.

While the French attitude alone was enough to cripple the Control Council, it in fact only masked a fundamentally more formidable obstacle to the treatment of Germany as an economic unit, namely, the

[344]

Soviet insistence at Potsdam that, as McCloy put it, "anything anybody captured does not count as reparations." In other words, the Russians proposed to take whatever they liked out of their zone without regard for the level of industry and without including their acquisitions in the total of their reparations account; thus, eastern Germany could become an economic desert capable of endlessly soaking up economic assistance for the exclusive benefit of the Soviet Union. President Truman, McCloy told the members of the US Group Control Council, was adamant against allowing the United States to be put in the position of financing reparations for the Soviet Union.11 Hope of reasonable Soviet co-operation in administering Germany as an economic unit dimmed further after September when work began in the Control Staff on the level of industry plan. Determined to have the maximum capital assets from the western zones made available for reparations, the Russians were ready to strip the whole German economy to the lone and, in attempting to do so, plunged the negotiations into a tangle of conflicting statistics.12

Since JCS 1067 and its expansion by USFET into a military government directive (issued on 7 July 1 945) were held under security classification until the end of the first week in August, the Potsdam Communiqué of 2 August was the first official knowledge the German people had of the Allied plans for their country and for their own future under the occupation. For them, the news was a stunning blow. The territory east of the Oder and Neisse Rivers was lost; factories would be dismantled for reparations; and with what was left of its land and economy, the country would have to support added millions of Germans about to be expelled from Poland, Czechoslovakia, Austria, Hungary, and Rumania. An allusion in the communiqué to "primary emphasis" on "the development of agriculture and peaceful domestic industries" appeared to echo the Morgenthau Plan; the main purpose of the occupation seemed to be to convince the Germans of their "total military defeat" and leave them to endure the "chaos and suffering" they had brought upon themselves.13

The austere program and hard language of the Potsdam Communiqué was not new to the U.S. occupation authorities. Much of it had also appeared in JCS 1067 and was taken almost verbatim from the Summary of US Initial Post Defeat Policy Relating to Germany of 23 March 1045.

To military government, however, the Potsdam decisions signaled the beginning of a positive program for the occupation. Although the tone of the 23 March summary emerged strongly from the Potsdam Communiqué, the content was significantly altered in the document that the President presented to the conference as the US proposal for initial control policy in Germany and was further modified in the version approved by the conference. The decision to administer Germany as an economic unit and another to provide uniform treatment for the German population appeared to eliminate dismemberment as a possible

[345]

Allied aim. More important for current military government operations, Potsdam opened the way for a political rehabilitation of Germany that would enable the Germans "in due course to take their place among the free and peaceful peoples of the world" and "allowed and encouraged" democratic political parties, local self-government (to be extended up to the Land level "as rapidly as may be justified"), and free trade unions. Harsh as the economic provisions of Potsdam appeared to be to the Germans, they were more moderate than some proposed and existing US policies. Whereas JCS 1067 put the ceiling on the German standard of living at the lowest level among the neighboring nations, Potsdam set it at the average of the European countries, excluding Britain and the Soviet Union.14 Potentially, then, the Germans could become eligible for relief at a level considerably above the disease and unrest formula.

The President, the JCS, and Eisenhower also made individual decisions in July that would be as important to the Germans in the US zone as the provisions of Potsdam. In one decision, while assigning responsibility to the War Department for procuring and financing imports to Germany, the President specified that the authorization would remain in force "whether or not an agreed program is formulated and carried out by the Control Council." He thereby opened the way for a separate relief program in the US zone.15 In another decision, accepting the conclusions of the Potter-Hyndley Mission, the JCS ordered Eisenhower as a member of the Control Council to advocate the export of 25 million tons of German coal during the period ending April 1946, although recognizing that "this may delay industrial resumption [in Germany, cause unemployment, unrest, and dissatisfaction among Germans of a magnitude which may necessitate firm and rigorous action." 16 In a third decision, Eisenhower, at a USFET G-5 conference on 19 July, stressed the need to help the Germans prepare for the coming winter and authorized the use of Army trucks and military drivers to bring in the harvest.17

On 6 August, Eisenhower became the first prominent Allied figure to talk directly to the Germans by radio. After three months, he said, the occupation and denazification had progressed enough to allow him to speak to them about plans for the future. The months ahead would be hard. There would be food and transportation shortages and no coal for heating during the coming winter. Damaged houses would have to be repaired. The Army was providing transportation, but otherwise the Germans would have to solve these problems themselves. They would have to work and help each other. As a token of a brighter future to come, he told them that they would be allowed to form trade unions and engage in local politics when they showed readiness for healthy exercise of these privileges." 18 Bleak as the message was, it was a first -some would later think

[346]

a false- ray of hope. The war, at last, was over. The enemy commander had become a concerned and responsible administrator.

Berlin in the summer of 1945, though only tenuously restored as the capital, was more than representative of the nation's woes. Divided, occupied by foreign troops, and isolated, the city was an island of 3 1/4 million people in a country for which it had once been the economic as well as political hub. For most of July, until the rail road bridge on the Elbe River at Magdeburg was repaired, food and coal trains from the western zones had to be unloaded at the river and reloaded onto Soviet-manned trains on the other side. The first U.S. train did not arrive in Berlin until would not resume until November.19 In the US sector, as in the others, the Russians cent of the industrial machinery. What was left was buried under rubble or was useless owing to lack of coal and electricity to run it and raw materials with which to work. The first firm to operate in Tempelhof, in the US sector, sharpened used razor blades. In the fall a radio manufacturer began turning out a maximum dozen sets a day, and several metal fabricators, on orders from military government, started making stoves and cooking utensils out of salvaged materials.20 The most visible part of the work force in the summer and fall -and for many months to come- were the Truemmerfrauen, women who scavenged usable bricks and other building materials from the rubble.

Bombing, destruction of bridges in the final battles, and the breakdown of the transportation system had reduced the city to a sprawling cluster of villages, each a block or two of habitable or nearly habitable buildings in which possibly a store or two remained open. In daylight the residents sallied out on foot in search of black market goods and firewood. Few went out after dark. Nighttime was the Russians' favorite time for picking up political suspects, as it had been with the Nazis, and they were not particular about sector boundaries or about whom they victimized.21 Ruined as the city was, it still attracted German refugees from east of the Oder River and from Czechoslovakia. More than three-quarters of them were women and children; they came by the thousands in the summer of 1945, sometimes bringing disease with them. Disease was nothing new in Berlin, however, which in the first months of the occupation was swept by waves of dysentery, typhoid fever, and diphtheria, all spread by sewage leaking into the water system from fractured sewer pipes. Usually the adults and older children survived, but the first wave of dysentery, which the Berliners called hunger typhoid, killed 65 percent of the newborn babies. 22

Clay described Berlin as "the world's largest boarding house, with all of the population on relief. " 23 After the bridge at Magdeburg was reopened and the food trains began running into the city regularly, the daily civilian ration rose gradually from

[347]

WOMEN SALVAGE BRICKS

less than 800 calories supplied in July to 1,250 calories, which the Russians had set as the maximum ration for normal consumers before the Western Allies arrived. The 1,250-calorie ration was more than the Germans in the western zones were getting; but the Germans in these zones, even those who lived in the large cities such as Frankfurt and Munich, could sometimes forage in the countryside, trading personal belongings to the farmers for potatoes, eggs, or meat. Berlin was an island, cut off from the outside, and the Berliners had to live on the ration, or on the black market. Col. M. D. Jones of Clay's Redeployment Co-ordinating Group reported what he saw on a visit to Berlin in September:

A typical meal consisted of 1 serving spoonful of canned stew, 2 or 3 boiled

potatoes the size of golf balls, 1 handful of hardtack crumbs, 1 cup black coffee

made from leftover grounds from US messes, and 1 spoonful of watery gravy. [Jones

was describing the meals served to a relatively small and fortunate group, those

who had jobs with the Army.]

A meal two maids were eating in the billet I occupied, which they claimed was

their only food for the day besides the meal described above, consisted of 11/2

thin slices of bread, 2 small half-green tomatoes, 21/4 small

[348]

BERLINERS RECEIVE BREAD RATION FROM A TRAILER because there is no transportation to business areas.

potatoes, and 1 onion half the size of one's thumb.

On several occasions I saw children and old people gathering grass in a park,

they said for food.

Although many children looked healthy, I also saw many covered with sores.

The sores, I was told, were the result of an inadequate diet-the slightest

bruise would fester.

I saw no fresh vegetables in the markets and was told there were none in the

US Sector. Only 3 out of 15 meat markets I visited had any meat at all. One

lead 20lbs. which was rationed 1/3 lb. to the customer.24

Artists and entertainers, especially the latter, lived better than almost anyone else. Out of respect for "culture," the Russians had put them in the highest ration category, 2,500 calories per day; such a ration was otherwise restricted to very heavy workers. As a result, the normal consumers in Berlin were well entertained if poorly fed. Next lest off were the manual laborers on essential jobs, who could thus qualify for increased rations. Public officials worked under the eve of military government for presurrender salaries and stood near the bottom on the ration scale. On the black market, of course, after the Ameri-

[349]

cans came everything could be had: butter, Spam, cheese, canned meats, and liquor. The prices in marks ran into the thousands for small quantities. Among the Germans, American cigarettes were the preferred currency, because they had an intrinsic value. A carton of any American brand, which cost the U.S. soldiers 50 cents in the PX, was worth 150 marks, $15 at the US rate of exchange, and in Berlin could bring several hundred dollars in marks. Matches were the small change.25

In the US zone proper, the military government economic specialists watched for small sparks of life in the industrial machine that had enabled Germany to wage war for six years against half the world. Out of their wartime profits, factory owners could afford to clean up and put their plants in order; but afterwards all they could do was wait for coal, electricity, and materials. In July, military government allocated coal to run one newsprint paper mill and in September enough coal to reopen a rolling mill to make sheet metal for cooking and heating stoves. The first window glass was produced in Bavaria in September, and a month later one chemical plant in Wuerttemberg-Baden began making soda ash needed for glass and soap, while another started to produce calcium Cyanamid for nitrogen fertilizer. The plants were using leftover and scavenged materials, however, and when these were exhausted they would have a hard time getting new stocks.26 Of the whole industrial establishment in the US zone about 15 percent was in working condition in August and was running at about 5 percent of capacity. Output was meager. All the soap produced in July, for instance, amounted to no more than an ounce and a half per person.27 One-time sales of a spool of thread per person and, with the use of ration coupons, of 10 German-made cigarettes (or 2 1/2 cigars) were events covered in the newspapers. 28

Coal was the key. In July and August, the output was 15 percent of the 1935-1936 monthly average. Every industry restarted increased the shortage. The amounts that arrived were always smaller than those shipped. Of 120 carloads consigned to Nuremberg, 70 carloads arrived. Another 1,000 tons of coal disappeared completely en route from Munich to Nuremberg.29 In his 6 August radio speech Eisenhower told the Germans to cut wood for the coming winter because there would be no coal for heating, and during the late summer and fall military government embarked on a wood-cutting program throughout the zone. The Army supplied power saws and axes and military trucks to haul the wood in areas the German trucks could not reach. Woodcutting progress became a required subject of military government detachment reports, but many detachments found that the idea did not really catch on with the Germans until after the first spell of cold weather in October.

The Transportation Corps' Military Railway Service, supervising the German Reichsbahn, had 90 percent of the first-line railroad track in the zone open by Septem-

[350]

ber and had a through train running from Frankfurt to Paris. But except for city and suburban lines, which were essential to get the German civilians back and forth to work, the railroads carried only US troops, DPs, and military supplies. The cars ran with leaking roofs and broken windows because new glass and tar paper always disappeared on the first run.30 Civilian goods, mostly farm produce and firewood, moved by truck; and the 100,000 trucks and busses in the zone had been so diminished by requisitioning of both the Wehrmacht and the US forces that less than a quarter of them were operable. In September, the Army released 12,500 surplus military trucks for sale to the German authorities.

Even without transportation, as the travel restrictions within the zone gradually eased and finally were abolished altogether in August, the Germans became a restlessly mobile people. By truck, by horse and wagon, or on foot carrying their possessions on their backs, they crisscrossed the countryside looking for relatives or for places to live. For the city dwellers, periodic trips into the country with spare pairs of shoes, rugs, or other household furnishings and pieces of clothing to trade for food were becoming necessary to survival.31

When the US Group Control Council took a survey during September in Frankfurt, Nuremberg, Kassel, and Stuttgart, the Germans most frequently mentioned food and housing as their main worries. A check of the inhabited dwellings showed that three-quarters needed repairs. More than half had no windows; a third had damaged roofs, and a quarter unsound walls. 32 In Frankfurt alone, 173,000 persons lived in basements, shacks, and ruins that would not be habitable in winter. Although military government ordered homeowners to rent out spare rooms and promoted programs for salvaging building materials from the debris of the bombing, continuing requisitions for troop and DP billets actually decreased the living space available to the Germans. In Wuerttemberg-Baden, a fifth of the population was inadequately housed, even by prevailing German standards. In Wuerzburg, Bavaria, one of the most heavily bombed cities, the 55,000 population were nearly all living in ruins. In Bremen, 62,000 persons lived in the basements of bombed-out houses; others lived in flimsy shacks, in air raid bunkers without light or ventilation, and in rooms without doors, windows, or roofs. When cold weather approached in October, military government initiated a forced exodus to the country districts of 30,000 people from Heidelberg, 10,000 from Wuerzburg, and similar numbers from other cities.33

Although, contrary to SHAEF G-5's earlier prediction, the Germans were not starving in the summer of 1945, malnutrition was undoubtedly a contributing cause of some deaths, particularly in Berlin. The US Group Control Council interrogators concluded that the Germans were not as undernourished as they looked; on the other hand, military government in Bavaria believed the Germans looked better physically than they should have, considering the

[351]

MANY LIVED IN SHACKS AND RUINS

rations they were getting. At the end of August, the USFET Chief Surgeon, Maj. Gen. Morrison C. Stayer, reported that nutritional survey teams had found that 60 percent of the Germans were living on a diet that would inevitably lead to diseases caused by malnutrition. Surveys, he said, already showed vitamin deficiencies and weight loss in both adults and children. Because the issued ration, which varied downward from 1,150 calories per day, was not enough to sustain life, and the additional 400 to 500 calories that the average German was assumed to be getting from cellar stocks, home gardens, and the black market were not enough to sustain productive labor, Stayer recommended raising the ration to 2,000 calories per day. In September, Clay applied to the Combined Food Board in Washington for an import allotment for Germany, expecting "to get our share but not at all sure it will be enough to supply the 2,000 calories recommended by the health officer." 34 Clay said he could not ask the Food Board "to accept as a

[352]

TROOPS SEARCH LUGGAGE; FOR BLACK MARKET GOODS

premise that food should be supplied to Germany on a scale equal to or greater than that supplied to other countries of the world who have suffered from but did not initiate aggressive war." 35 Moreover, the requirements for Germany would be large. The total agricultural output of the US zone from November 1945 to September 1946 would only be enough to supply 938 calories per day to the normal consumer. An increase to 1,500 calories would require 543,000 tons of imported food, and an increase to 2,000 calories would require nearly twice as much.36

On the black market, in the zone as in Berlin, all kinds of goods were available at astronomical prices in marks and often only in exchange for items of value, such as cigarettes, sugar, butter, and coffee-all of which functioned more as currency than as consumable commodities. The "banker" for one large black market ring was carry-

[353]

ing nearly $300,000 in diamonds when he was arrested. The DPs, because of their privileged status, and the US troops, UNRRA employees, and Red Cross workers, because of their access to US goods, figured prominently in the black market. The Germans partly depended on it for their subsistence and partly used it as a means for converting their money into material goods as a hedge against inflation. Because search operations like TALLYHO consistently failed to turn up sufficient evidence, USFET and the military districts for several months persuaded themselves that the black market was nothing to worry about. In September, on the apparent assumption that the people involved were mostly soldiers wanting to trade cigarettes or chocolate bars for souvenirs and Germans wanting to oblige them, USFET opened officially sponsored barter markets in Stuttgart and Frankfurt-thus contributing to the further undermining of confidence in the currency. In the fall, certain by then that a black market existed, USFET began to concern itself with the professional operators who were definitely criminals and might also be Nazis using the black market to support themselves in the underground and who dealt heavily in US goods and supplies pilfered from Army dumps; by the end of the year an average of $10,000 worth of supplies a day was disappearing from the Quartermaster depot at Ludwigsburg alone. In October, military police searched two passenger trains coming into Bremen and confiscated a truckload of illegal goods, mostly Army property and black-market slaughtered meat.

Certainly the most numerous and probably the most successful black marketeers were not the professionals but the farmers. They were required by law to deliver all their produce, except subsistence allowances for themselves and their families, at fixed prices to authorized distributors. Under the Nazi regime the Reich Food Estate had kept records on the productivity of every farm down to the last egg and quart of milk; but in the many places where these records had not survived the war, military government had a much looser hold on production. In Bavaria in the fall of 1945, the legal butchering of hogs was 50 percent below normal, and six sugar beet processing plants had to be closed down because the farmers had diverted the beets to the black market. The farmers argued that they in turn had to barter to get tools and equipment, but the people in the cities widely suspected that most were well on the way to acquiring enough property to be able to carpet and furnish their cow barns like parlors if they wanted.37

Except for black marketeering, some thefts of food and firewood, and petty violations of military government ordinances, the German civilian crime rate was low, sometimes almost disconcertingly low for the Army agencies charged with ferreting out and suppressing resistance. In October, after five months of occupation, Seventh Army G-2 believed Germany to be a "simmering cauldron of unrest and discontent" and claimed to have detected a "mounting audaciousness in the German population"; but as concrete evidence G-2 could only cite some illicit traffic in interzonal mail (then still prohibited), a "strongly worded"

[354]

Werwolf threat to one military government officer in the Western Military District, and a protest against denazification from the Evangelical Church of Wuerttemberg.38 Patrols occasionally found decapitation wires stretched across roads, ineptly it would seem, since no deaths or injuries resulted from them. Military government public safety officers from scattered locations reported various anti-occupation leaflets and posters, some threats against German girls who associated with US soldiers, and isolated attacks on soldiers. Although not a single case was confirmed, possibly the most talked about crimes against the occupation were the alleged castrations of US soldiers by German civilians. When the commanding officer of Detachment E3B2, in Erbach, Hesse, was asked to investigate one such rumor, he reported that not only had there been no castration but that there had not been a single attack on US military personnel in over four months of occupation.39 The most pressing concern of public safety officers was often with getting the German police out of their traditional nineteenth century Prussian drill sergeant uniforms and into American styles, usually modeled on the uniforms of the New York City police. Wherever troops were stationed, especially in towns and smaller cities, prostitutes and camp followers were a moral problem, placed added strain on food supplies, housing, and medical facilities (frequently also on jails), and raised mixed feelings of disgust and jealousy among the other civilians. In quarrels with other civilians and with the police, the prostitutes did not hesitate to call on their soldier friends.40

The Germans attributed all violent crimes to the DPs; and military government reluctantly came close to agreeing with them. Of 2.5 million DPs originally in the US zone, all but 600,000 had been sent home by the end of September, and General Wood reported the repatriation problem "substantially solved." 41 But those who stayed were becoming a special problem, being a hard core of largely nonrepatriable stateless persons. About half were Poles, for years the most mistreated of the Nazi forced laborers and now torn between their desire to go home and their apprehension about the future awaiting them in Communist Poland. The rest were Balts, non-German Jews, eastern Europeans other than Poles, and -although many fewer than there had been- Soviet citizens, most of whom tried to claim special status as Ukrainians. USFET policy made repatriation entirely voluntary for all DPs except those who came from within the pre-1939 boundaries of the Soviet Union; many had legitimate reasons for not wanting to return, principally fear of political or religious persecution. As the total number of these displaced persons de-

[355]

TANKS MOVE IN to keep order in Yugoslav DP camp.

clined, however, the percentage of doubtful types among those who remained, such as criminals and Nazi collaborators, constantly increased, as did their influence on the others. A questionnaire, similar to the Fragebogen used for the Germans, tried on 240 DPs in a camp at Regensburg, Bavaria, revealed that 40 percent, if they had been Germans, would have been in the mandatory removal category, that is, unemployable in responsible positions and possibly subject to arrest.42

Among all categories of DPs, uncertainty about the future, free rations and lodging without having to work for them, privileged status under the occupation, and virtual immunity from the German police bred indolence, irresponsibility, and organized criminality. Their access to Army, UNRRA, and Red Cross supplies made them potent operators in the black market; the camps provided havens for black market goods and bases for criminal gangs; and the Army-issue clothing that most of them wore was excellent camouflage for the criminal elements and an effective

[356]

means of intimidating the Germans.43 The 100,000 or more DPs who did not live in camps or who drifted in and out of them at will constituted the nucleus of a kind of Army-sponsored underworld. Even the former concentration camp inmates were becoming an annoyance. Many persisted in wearing their convict uniforms and were willing to regale any newspaper reporter who would listen with supposed new atrocities being inflicted upon them by the Army. Some were trying to make their privileged status permanent by having official-looking documents drawn up and badges made.

At the same time, stories about the DPs in US newspapers were making them objects of particular public and official sympathy. In the summer the US representative on the Intergovernmental Committee on Refugees, Earl G. Harrison, visited the camps as President Truman's special emissary and recommended setting up separate camps for Jews. Later, after Saul S. Elgart of the American Joint Distribution Committee surveyed the Jewish camps, UNRRA undertook to distribute Red Cross packages to the Jews, thereby raising their ration to over 3,000 calories a day. In September, Eisenhower personally inspected several DP camps and announced that general officers would inspect all camps. Although the inspections showed the camps in general to be adequate and the larger ones often excellent with kindergartens, chapels, medical facilities, electric lights, flush toilets, and average food rations above 2,100 calories a day, the press and public concern did not abate. In late September, Eisenhower ordered the military government and military authorities to requisition housing for DPs from the Germans without any hesitancy, prohibited any restrictions on the DPs' freedom of movement, and made food and sanitation in the camps a concern of all responsible officers.44 As a consequence, the Office of Military Government for Bavaria reported later, "there were so many inspections by generals, public health officers, correspondents, and other privileged emissaries of interested organizations that the objects of scrutiny themselves cried for a respite." 45

Upon hearing of the order to let the DPs come and go as they pleased, the detachment in charge of 15,000 in a camp at Wildflecken, Bavaria, observed that considering the marauding and looting which had taken place when only 1 percent a day were allowed to leave, it looked to the future "with great concern." 46 The detachment's apprehension was not unfounded. DP depredation was the chief reason for rearming the German police in September; until then, they had only, carried nightsticks. Military government recorded 1,300 DP raids against Germans in Bavaria during one week in October, and in some country districts people were afraid to leave

[357]

their houses even in the daytime. Many farm communities found a new use for old air raid sirens: to warn of approaching DP bands. In Munich, DPs constituted 4 percent of the population but were responsible for 75 percent of the crimes. Military government courts in Bavaria held 2,700 trials between 1 June and 30 October in which displaced persons were accused of serious crimes, such as murder, robbery, and looting; and in Bremen, a DP population of 6,000-3,500 of them males over fourteen years of age committed 23 murders, 677 robberies, 319 burglaries, and 753 thefts. Organized gangs armed with pistols and automatic weapons operated out of the Bremen camps. When an eight-man gang murdered thirteen Germans during one night in November, soldiers of the 115th Infantry raided the camp from which they had come and uncovered large quantities of illegally slaughtered beef and US property. Afterward, in protest, the DPs flew black flags and placed large signs at the camp entrance reading "American Concentration Camp for Poles." 47

Next to the black market and the DPs, German youths were military government's most worrisome concern. Many children were completely adrift, orphaned by the war, unable to find their families, or simply abandoned. All were idle. Schools were closed; youth organizations, other than a few sponsored by the US forces, were prohibited; and entertainment and recreation facilities were requisitioned for the US troops. The worst off'-and most dangerous in the eyes of military government-were those in their late teens. Although too young to have served in the Wehrmacht and experienced the sobering effects of defeat in the field, they were old enough to have absorbed Nazi attitudes. The Freikorps and the Nazi storm troops had found many recruits among a similar group after World War I. Under the occupation, these young people were becoming sidewalk loafers. They could not continue their educations or learn trades, and the only jobs being offered involved cleaning up rubble, which was not enticing in either the short or the long run. So they gathered out of the sight of the Americans, made up bawdy verses about the behavior of the US soldiers and German girls, at times threatened to shear the hair of girls who had soldier friends, and sometimes, military government officers suspected, rigged decapitation wires or attempted acts of sabotage. Their activities were all quite amateurish but might not remain so once enough young, lout more experienced, prisoners of war returned home.48

In the summer, though far from ready to democratize the German educational system and by no means certain how to go about it anyway, the detachments worked under USFET orders to get the schools open and the children and teenagers off the streets. Grades one through eight opened on 1 October with slightly more students than in 1939, but with about half the teachers and buildings. Since the teachers were as politically pure as military government and the CIC could get them, they

[358]

PRINTERS ASSEMBLE DENAZIFIED TEXTBOOKS

were consequently often persons who had been away from the profession a long time or who were the products of crash courses in pedagogy that the detachments ran when too many professionals in their districts turned in unsatisfactory Fragebogen. The average age of the teachers in Munich was fifty-seven, and the pupil-teacher ratio was eighty-nine to one. Secondary schools were the most difficult to staff and did not begin opening until November and December. Although "pep talks" on democracy always accompanied the openings, the education officers' subsequent visits to the schools were more frequently in the interest of discipline. Nazi textbooks had been rigorously screened out, but their replacements, relics from the Weimar Republic, were sometimes not really antidotes to militarism and nationalism. The fifth-year reader contained items such as Frederick the Great's speech to his troops before the battle of Leuthen ("Let us heat the enemy, or let us be buried by his batteries . . . ." ) ; a contemplation entitled "At the Funeral of My Friend Lieutenant Wurche, Killed in Action, 1915" ; and Liliencron's "Ballad of the Battle of Kolin." The seventh-year arithmetic looks used the economic and territorial losses under the Treaty of Ver-

[359]

sailles as problems. On the flyleaves, USFET included the disclaimer, "The fact of reprinting does not imply, seen from the educational and other points of view, that this book is absolutely without objection." 49

The newspapers, as the following extracts from the Weser Bote, published in Bremen, demonstrate, mirrored a dark Germany:

3 October

Children under 18 and pregnant women will get an additional pound of apples

or pears in their rations.

5 October

Count Bernadotte will arrive on Monday with General Eisenhower's permission

to arrange for setting up soup kitchens to feed German children during the

winter.

10 October (want ads)

Request information about D. Luerssen, last a member of the replacement

battalion at Riga-Strand (Latvia).

Opera singer wants a piano, to buy or on loan for a man's suit.

13 October

Lida Barova, Czech movie actress who collaborated with the Nazis has been

arrested and turned over to the Czech authorities.

Last night the street sign on Friedrich Ebert Street [recently renamed after

the first president of the Weimar Republic] was painted over, and the newspaper

kiosk at the main post office was smeared with Nazi slogans and swastikas.

16 October

General Clay said the American occupation would stay in Germany for many

years. Asked if it could be as long as a generation, he said it could well be.

Who can give information concerning Corporal Claas Mueller?

Who can give information concerning Flak Auxiliary Gisela Slomberg?

30 October

Monika yon Dittmar, daughter of General Kurt yon Dittmar, Nazi radio

commentator, was picked up wet and hungry on a street in Oberammergau. After her

arrest she tried to commit suicide by jumping from a window.

In Bremen, SS General Count George Hennig yon Bassewitz-Behr was arrested. He

had been police chief of Hamburg and a friend of Heinrich Himmler.

The first Liberty Ship, William F. Cody, entered Bremen harbor.

3 November

Beer brewing has been stopped in Bavaria because the barley must be used to make

flour.50

JCS 1067 established as one of military government's basic objectives "the preparation for an eventual reconstruction of German political life on a democratic basis." Concerning politics, however, the directive instructed Eisenhower, "No political activities of any kind shall be countenanced unless authorized by you," and added, "You will assure that your military government does not become committed to any political group." Although the first sentence seemed faintly to affirm a controlled resumption of political activity, the second echoed a more fundamental premise, namely, that military government should be nonpolitical. FM 27-5, as published two years earlier, read, "Neither local political personalities nor organized political groups should have any part in determining the policies of military government." 51 SHAEF G-5, there-

[360]

fore, had assumed all along that the best way to keep military government out of politics was not to allow its practice and had planned to prohibit political activity, not to revive it.

The prohibition was almost totally effective in Germany after the surrender, no doubt because the twelve Nazi years had left little with which to renew political activity. No party, other than the Nazi party, had existed legally -or even illegally in any organized fashion- in Germany since 1933. The Communist and Social Democratic party leaders had either been jailed or had emigrated, and the leadership of the other parties had either been assimilated into the Nazi system or, with the help of the Gestapo where needed, reduced to complete impotence. The German people, never notably enthusiastic about party politics, remembered what had happened to the Marxist and bourgeois parties under Hitler and what was happening to the Nazis under the occupation. Consequently, when SHAEF G-2 undertook to investigate German political activity in early July 1945 it could not find any "in the traditional sense of the term . . . . Normal political issues," it concluded, were relegated "to the status of academic questions," the subject of low key discussion among a few scattered survivors of the old parties.52

On the other hand, in the field, military government had been learning since Aachen that politics was more than just parties and party rivalries. German appointees invariably represented social, religious, economic, and -with or without party labels- political outlooks. The absence of a positive political program meant only, as the G-5 field survey pointed out in March, that political directions were determined by special interests such as the Church or by individuals and cliques. Hence, military government, willingly or not, was involved in politics, and most dangerously so because it would have to bear the entire responsibility for the political consequences of the acts and character of its supposedly nonpolitical appointees. General Clay, who had missed the Aachen affair, had his own lesson in June when a wilder storm broke over the appointment of the first postwar Minister President of Bavaria, Fritz Schaeffer (see below, pp. 384--86) . Seeing military government in Bavaria trapped in a crossfire of press and public recriminations, Clay wrote to McCloy, "The experience in Bavaria seems to me to indicate the desirability of relaxing the lean on political activities as promptly as possible." 53

The Potsdam decision to allow and promote democratic political parties in Germany was, therefore, not unwelcome to the U.S. occupation authorities; and the day after his 6 August speech, in which he told the Germans they would be permitted to engage in local political activities, Eisenhower instructed the military districts to begin licensing parties at the military districts to begin licensing parties at the Kreis level.54 The public reacted, the Western Military District reported, with "stunning apathy." A few survivors of the pre-Nazi parties, mostly Communists and Social Democrats, asked desultory questions about licensing procedures, which the military government officers could not answer because there were none. Representatives of would-be

[361]

movements occasionally drifted into detachment offices. In Munich, for instance, a group calling itself the League of German Culture proposed to rally politically the devotees of art and culture. The vast majority of the Germans, the detachments agreed, were occupied with other things, such as food, housing, and the other problems of existence in a defeated and devastated country. These Germans took Eisenhower's offer as evidence of approval, which they craved, but were willing to let the issue drop there, feeling that politics had brought on all their troubles in the first place. Those who had been pro-Nazi without having joined the party were congratulating themselves on a narrow escape and were not willing to risk another even remotely. In Kurhessen, the regional detachment put the majority of the farmers in the latter category and saw only the urban workers as expecting to benefit in any way from restored unions and political parties.55 The torpid public response at least saved military government much of the embarrassment of not being able to actually license political parties. Neither USFET nor the military districts had worked out the procedures and, therefore, they had to put a freeze on the whole program for nearly two months.56

In the interim, although in no way evincing a ground swell of democratic enthusiasm, a party-political pattern began to emerge. In a limited sense, the Soviet zone provided the model. Already on 10 June, the Soviet Military Administration in the zone had granted permission to organize "all anti-fascist parties." 57 By the end of the month, four parties with national potential had secured licenses: the Communist party, the Social Democratic party, the Christian Democratic Union, and the Liberal Democratic party. Although the Soviet authorities would not have objected, none except the Communist party regarded itself as headquartered in the Soviet zone. All had roots reaching back into the pre-Nazi period and, except for the Communist party, were just beginning to feel their way into the new era. By being licensed in the Soviet zone, they acquired corporate existences but not much more.

The first parties on the scene in the US zone were the Communists and the Social Democrats, in that order. They shared one big advantage: neither bore the Nazi taint. The Social Democrats could claim the distinction of having been the only one of the old parties (the Communists had been outlawed by then) to have voted against the granting of dictatorial powers to Hitler in March 1933. The Communists, while their record under the Weimar Republic showed them to be almost as lacking in respect for democracy as the Nazis, had been the party most ruthlessly persecuted by the Nazis; and since they were protégés of one of the victorious powers, they were also by definition democratic. In the US zone, the Communists and the Social Democrats also had two common problems: the opposition of the Catholic Church and the absence of a working class majority. The Communists also had to contend with the negative effects of "rumors and reports from the Soviet Zone"; the Social Democrats had to deal with a left wing attracted by a So-

[362]

viet-sponsored Communist bid for unity of the working class parties.58

Of the pre-Nazi middle class parties, the two showing strongest signs of life were the (enter Party and its Bavarian counterpart, the Bavarian People's party. Traditional ties with the Catholic Church helped them to dissociate themselves from nazism, although their members were not always successful in doing so as individuals. US military government, with some misgivings, had been relatively generous in appointing their potential leaders to administrative posts under the occupation, most notably Dr. Adenauer as Oberbuergermeister of Cologne and Fritz Schaeffer as Minister President of Bavaria. But these parties hesitated to enter postwar politics in their old Catholic stance, partly because their more progressive leadership wanted to give them a broader base of voter appeal and partly because -in the case of the Bavarian People's party especially- their actions under the Weimar Republic were not above reproach, but mostly because they were afraid they would not be able to compete against the Communists and Social Democrats. For this last reason, they would just as soon have seen the prohibition on political activity prolonged, and they were furthermore spurred to break with the past and take the lead in promoting "Christian" parties as soon as the Social Democrats and Communists began to organize.

The idea of a Christian party or parties uniting all confessions through their common opposition to Marxist atheism, after being written into a formal program in Adenauer's Cologne in March 1945, took hold more or less independently in all parts of Germany. Advocates of such a party in the Soviet zone gave it a name, Christian Democratic Union, on 25 June when they secured a license to form it. In the US zone the name Christian Social People's party was more frequently used until September, when Christian Democratic Union (CDU) came into general use in the Laender of the Western Military District and Christian Social Union (CSU) was adopted in Bavaria. By the time they emerged in the US zone, the CDU and CSU were, in the words of one observer, "a banquet for political gourmets." The CDU in particular attempted to embrace all elements opposed to communism or social democracy for religious or any other reasons, and even some that were not opposed. Its right wing catered to industrialists, big businesses, and large landowners, while its left wing looked for support from civil servants, small shopkeepers, and farmers and, in working class areas, endorsed socialization of some industries. The CSU additionally presented itself as a defender of the Bavarian way of life and as a staunch ally of the Catholic Church. Both parties also let it be known, to the marked annoyance of military government, that they were prepared to welcome repentant Nazis to their ranks, and both endorsed the view that denazification should be limited to the "real" Nazis, the small numbers in the top leadership. The rest they dismissed as Mussnazis, Nazis by compulsion.

The Liberal Democratic party, licensed in the Soviet zone in June, was a revival of the old German Democratic party. Similar offshoots of the German Democrats in the US zone went by several names, most prominently the Democratic People's party. 59 Having a nineteenth century lib-

[363]

eral outlook and being both defenders of private enterprise and private property and nonsectarian, they were closer to the average American's idea of a political party than the others. Their weaknesses were an appeal limited to the middle class and the need to find a middle ground between the Social Democrats and the CDU-CSU -both of whom stretched their programs so as to leave them practically no common ground. The Democratic People's party had a minor stronghold in Wuerttemberg-Baden, where one of its founders, Dr. Reinhold Maier, was the Land Minister President appointed by military government.60

Military government political analysts worried about the paucity of leadership talent in all parties. Too many good men, they believed, had either been killed, broken, or driven out of the country by the Nazis or were too old. Except for the few who had survived the concentration camps or other forms of Nazi persecution, those who were left had apparently been, at best, "political office boys," too insignificant to have attracted the Nazis' attention. However, the one major new political figure to appear in the US zone, Dr. Josef Mueller, leading founder of the CSU, nonplussed the Americans. A prominent lawyer and member of a Munich patrician family, Mueller had the attributes of a typical Bavarian, including a double chin. He was also suspected of being an intriguer and a "double-triple-crosser." He cultivated good relations with the Americans but reportedly told his followers that, "in a pinch," it might be necessary to go over to the Soviet side. He gave information to US intelligence agencies but was thought also to have contacts with Russians. While professing to reject the rightist outlook of the old Bavarian People's party, he argued for leniency toward nominal Nazis and accepted them into the CSU. His membership in the Abwehr (counterintelligence) during the war would ordinarily have been enough to put him in the mandatory removal, if not automatic arrest, category under the occupation; however, he had spent the last months of the war in a concentration camp, he had the confidence of the Catholic hierarchy in Bavaria, and he had a supportable claim to have been a go-between with the Vatican for the German resistance while he was in the Abwehr.61 Perhaps, as the summer of 1945 wore on, Mueller's best attribute in the eyes of military government was that compared to his strongest rival, Minister President Schaeffer (see below, p. 385), he was beginning to look like a sterling champion of democracy.

Ready or not, however, the Germans in the US zone were going to taste democracy soon-sooner than anyone expected. They were not going to get it because they wanted it or because they deserved it but because General Clay believed in learning by doing and -probably as much as for any other reason- because the end of the war in the Pacific inspired him to convert necessity into virtue. After V-J Day, USFET G-5 records showed that 40 percent of the officers and 50 percent of the enlisted men in military government would

[364]

be eligible for discharge by the end of 1945.62 With this information in mind, on 16 September, Clay wrote to McCloy that he had worked out a program for local elections in the US zone. He continued:

The Potsdam Agreements call for restoration of local self government as rapidly as consistent with the purposes of the occupation. If the Germans are to learn democracy, I think the best way is to start off quickly at the bottom. Besides, this will help us reduce the personnel needed for military government. With many officers returning to the US in the coming months, we will not be able to staff a large number of local detachments. Yet, we can hardly withdraw the detachments until officials appointed by us have been replaced by others selected by the Germans.63

Four days later, orders went out to German Land governments to write election codes and to the military districts to prepare for elections in January 1946 in communities (Gemeinde) of less than 20,000 people, to be followed in March and May by elections in Landkreise and communities with 20,000 to 100,000 people. Elections, as it turned out, were announced ahead of the procedures for licensing political parties. The procedures did not reach the detachments until the first week of October.64

Apart from Clay and his staff', the consensus of the Americans and Germans was that the plan for elections was premature, dangerous, and potentially disastrous. Clay, in fact, told McCloy that some of his own advisers were urging him to postpone the elections.65 Doctrinally, Clay's decision appeared to be flaming heresy to most of military government. Although no such program existed, it had been a fundamental assumption of military government that the Germans would be subjected to an extensive period of education and training in democracy. President Roosevelt, after all, had talked in terms of a whole generation. To hold elections after eight months and without the German character having been remolded in any significant way could only be judged frivolous or cynical. Furthermore, as a practical matter, early elections appeared to offer nothing but disadvantages. At the end of October, local parties had been approved in only six of the Bavarian Kreise. In the important Munich Stradtkreis, the second party, the Social Democrats (the Communists were first), was not licensed until 17 November. In some Kreise not a soul showed up even to talk about founding a party. And USFET's rules did not exactly encourage would-be politicians or promote speed in the granting of licenses. The names of twenty-five sponsors were required on each application; and each sponsor had to submit a personal Fragebogen, which brought him to the attention of Special Branch and CIC investigators. The people, the politicians, and the military government detachments all wanted the elections postponed. When Louis P. Lochner, Chief of the Berlin Bureau, Associated Press, toured Bavaria in the second week of October, he reported that public and military government opinion was preponderantly against early elections. A quarter of those responding in a poll taken in Munich stated categorically

[365]

that they would not vote in any election. Even Adalbert von Wittelsbach, pretender to the Bavarian throne, vacant since 1918, indicated that he proposed to wait a while before attempting to revive the monarchist cause. The parties that had been licensed seemed to be campaigning against the elections as much as against each other. None of them wanted to risk their fledgling organizations in a test of strength; and since many of the prospective candidates were already military government appointees, they did not want to risk their jobs.66 In mid-October, Clay himself told the CAD:

"Except for [four] cities mentioned above and some smaller cities where political parties are in the process of formation, complete political apathy is reported from nearly every section of [the] American Zone . . . . There is significant unanimity in reports from Military Government in stressing this fact and in observing that [the] German masses are entirely unready for self-government and ignorant of democratic processes and responsibilities." 67 Nevertheless, in a USFET directive of 23 November, he ordered the Land military governments to set firm dates for the Gemeinde elections in January and authorized them to license parties at Land level, a harbinger of more important elections to come.

[366]

Return to the

Table of Contents