CHAPTER XX The Final Fight To Break Out of the Forest Take a "giant step," First Army's General Hodges had said in effect at the start of the November offensive. By 19 November, the day when Hodges directed commitment of the V Corps, results of the first four days of fighting had indicated that a giant step was not in the books. Certainly not for the moment. (See Map VI.) A regiment of the 104th Division on the VII Corps north wing had had a whale of a fight to capture dominating heights of the Donnerberg and the Eschweiler woods cast and northeast of Stolberg. At the same time a neighboring attack for a limited objective by a combat command of the 3d Armored Division had proved as costly as many a more ambitious armored attack. In the sector of the 1st Division, which was making the corps main effort, getting a toehold on the Hamich ridge and carving out a segment of the Huertgen Forest near Schevenhuette had been laborious tasks. On the corps south wing between the 1st Division at Schevenhuette and the V Corps near Huertgen, the 4th Division still was ensnared in the coils of the forest. The 4th Division stood to benefit most directly from General Hodges' order to the V Corps to join the offensive. General Barton would gain both additional troops and a narrowed sector. The 12th Infantry, which had fought so long and so futilely on the bloody plateau near Germeter, at last was to join its parent division, and the shift northward of the intercorps boundary removed both Huertgen and Kleinhau from 4th Division responsibility. No lengthy wait would be necessary before measuring the effects of the V Corps commitment upon the 4th Division's fight. Having paused to consolidate the limited gains of the first four days, General Barton had ordered renewal of the attack on 22 November, the day after the start of the V Corps offensive.1 Despite alarming casualties, neither assault regiment of the 4th Division before 22 November had penetrated much more than a mile beyond north-south Road W, which follows the Weisser Weh and Weh Creeks and marks the approximate center of the Huertgen Forest. On the north wing, Colonel McKee's 8th Infantry between axial routes U and V still was a thousand yards short of its first objective, forested high ground about the ruined monastery at Gut Schwarzenbroich. Troubled by a right flank dangling naked in the forest, Colonel Lanham's 22d Infantry had progressed little beyond the intersection of axial [464] routes X and Y, still more than a mile away from the objective of Grosshau. To many, the final division objective of the Roer River at Dueren, not quite six miles to the northeast, must have seemed as far away as Berlin.

On the more positive side, a day or so of consolidation had temporarily cased two of the more serious problems the 4th Division faced. First, both regiments now had vehicular supply routes reaching within a few hundred yards of the front. Second, a gap more than a mile wide between the two regiments had been closed. Had General Barton believed that these two problems would not recur and had he been fighting an inanimate enemy incapable of reinforcements or other countermeasures, he might even have entertained genuine optimism. As it was, mud, mines, enemy infiltration, and shelling again might compound the supply situation; and so long as the 22d Infantry drove cast on Grosshau while the 8th Infantry moved northeast more directly toward Dueren, a gap between the two regiments would reappear and expand. As for the enemy, it was true that the 275th Division had incurred crippling losses, as had the 116th Panzer Division's 156th Panzer Grenadier Regiment, a skeleton masquerading as the same regiment which had fought earlier near Germeter and Vossenack.2 But by 21 November, the eve of the renewal of the American attack, the last contingents of the 344th Infantry Division which the Seventh Army had summoned up from the south were arriving. As this division took over, the 116th Panzer Division was pulled out for refitting, and the new division began absorbing nonorganic survivors of the 275th Division. Thus the Americans at this point faced a completely new German unit.3 The closeness of opposing lines and the density of the forest having denied unqualified use of air, armor, and artillery support, both commanders of the 4th Division's assault regiments in their attacks of 22 November turned to deception. Both Colonel McKee and Colonel Lanham directed one battalion to make a feint to the east with every weapon available, including smoke. At the same time, another battalion of each regiment was to make a genuine attack through the woods off a flank of each demonstrating battalion. The Germans reacted exactly as desired. Upon the demonstrators, who were relatively secure in foxholes topped by logs and sod, they poured round after round of artillery and mortar fire. Against the battalions which were slipping through the woods, they fired hardly a shot. On the north wing, the flanking battalion of the 8th Infantry swept through a thousand yards of forest to reach Gut Schwarzenbroich. Only there, in a cluster of buildings about the ruined monastery, did the Germans resist in strength. While this fight progressed, Colonel McKee poured his reserve battalion in behind the main enemy positions opposite his demonstrating battalion. Although the Germans soon deciphered this maneuver and opposed later stages of the advance, the fact that they had been lured from their prepared positions meant that the ruse had succeeded. As night came [465] Colonel McKee's reserve battalion dug in securely about a triangle of roads at the intersection of Road U and the Renn Weg (Point 311.1). From here Colonel McKee might exploit both northeast along Road U and southeast along the Renn Weg.

In one respect the fruits of deception in the sector of Colonel Lanham's 22d Infantry west of Grosshau were even more rewarding. While a battalion on the regiment's north wing demonstrated, the battalion stealing around the enemy's flank met not a suggestion of opposition. Alongside a creek and then along firebreaks, the battalion slipped like a phantom through the thick forest. More than a mile the men marched without encountering a German and at nightfall dug in to cover the junction of Roads V and X near the edge of the forest no more than 700 yards west of Grosshau. Colonel Lanham's reluctance to order this battalion alone and unsupported out of the woods into Grosshau may have stemmed from experience elsewhere in his sector. The enemy remained in strength astride the 22d Infantry's route of communications, as Colonel Lanham's right wing battalion had found while trying to protect the regimental southern flank. Only after incurring the kind of casualties that had come to be associated with fighting in the forest did this battalion succeed in gaining 900 yards to reach a junction of firebreaks between Roads X and Y, still a thousand yards short of the eastern fringe of the forest. The battalion was so understrength and so disorganized from losses among officers and noncommissioned officers that at one point Colonel Lanham had to plug a gap in the line with a composite company of 100 replacements. The problems to be solved before Grosshau might be attacked were serious. Though the 12th Infantry had left the wooded plateau near Germeter on 22 November to begin an attack to secure the 22d Infantry's right flank, this depleted regiment would require several days to do the job. It took, in fact, four days, until 26 November. In the meantime, the 22d Infantry was open to a punishing blow from those Germans who at this point still held Huertgen and Kleinhau. Neither was there a quick solution to eliminating the enemy that had been bypassed in the swift advance or to sweeping Road X of mines and abatis so that an attack on Grosshau might be supported. On 25 November, the day before the 12th Infantry reached the woods line to provide the 22d Infantry a secure flank, Colonel Lanham saw a chance to capitalize on the commitment that day of the 5th Armored Division's CCR against Huertgen. In conjunction with that attack, he ordered an immediate attempt to capture Grosshau. Seeking surprise, Colonel Lanham maneuvered one battalion through the woods to hit the village from the northwest while another battalion converged on it from the southwest. The plan did not work. Delayed four hours while tanks and tank destroyers picked a way over muddy trails and firebreaks, the attack lost every vestige of surprise. When the jump-off actually came at noon, coordination with the armor failed. Only three tanks and a tank destroyer emerged from the woods with the infantry. Antitank gunners in Grosshau quickly picked off the tanks. At the same time violent concentrations of artillery fire drove the infantry back. Men who had yearned for so long to escape the stifling embrace [466] of the forest now fell back on it for refuge. The sad results of this attack prompted the division commander, General Barton, to approve another pause in the 22d Infantry's operations. Colonel Lanham was to consolidate his positions, bring up replacements, and make detailed plans for taking Grosshau. In particular, the regiment was to make maximum use of nine battalions of artillery which were either organic or attached to the division. Here on the edge of the forest the artillery for the first time might provide observed, close-in fires capable of influencing the fighting directly and decisively.

In the meantime, on the division's north wing, Colonel McKee's 8th Infantry on the second and third days of the renewed attack had come to know the true measure of the advantage the regiment had scored. The battalion which on 22 November had reached the junction of Road U and the Renn Weg drove northeast along Road U for more than a mile. Although subjected to considerable shelling, this battalion encountered only disorganized infantry resistance. On 24 November Colonel McKee sent this battalion northward to fill out the line between Road U and the division's north boundary and at the same time to cut behind those Germans who still were making a fight of it at Gut Schwarzenbroich. During the same two days, another battalion moved slowly against more determined resistance southeast along the Renn Weg and on 25 November surged to the regiment's south boundary. The total advance was more than a mile. Colonel McKee's 8th Infantry stood on the brink of a breakthrough that could prove decisive. In four days, the regiment had more than doubled the distance gained during the first six days of the November offensive. The forward positions were almost two miles beyond the line of departure along Road W. Only just over a mile of forest remained to be conquered. Yet how to achieve the last mile? The troops were exhausted. Because the leaders had to move about to encourage and look after their men, they had been among the first to fall. A constant stream of replacements had kept the battalions at a reasonable strength, but the new men had not the ability of those they replaced. For all the tireless efforts of engineers and mine sweepers, great stretches of the roads and trails still were infested with mines. Even routes declared clear might cause trouble. Along a reputedly cleared route, Company K on 23 November lost its Thanksgiving dinner when a kitchen jeep struck a mine. Every day since 20 November had brought some measure of sleet or rain to augment the mud on the floor of the forest. To get supplies forward and casualties rearward, men sludged at least a mile under constant threat from shells that burst unannounced in the treetops and from bypassed enemy troops who might materialize at any moment from the depths of the woods. Again a gap had grown between the 8th Infantry and the 22d Infantry. The gap was a mile and a quarter wide. With the failure of the 22d Infantry at Grosshau on 25 November, the 4th Division commander, General Barton, had at hand an all too vivid reminder of the condition of his units. Much of the hope that entry of the V Corps into the fight might alter the situation had faded with the disastrous results of the unrewarding early efforts of that corps to capture Huertgen. The successes of the 8th and 22d Infantry Regiments in renewing the [467] MEDICS aid a wounded soldier in the woods. attack on 22 November appeared attributable more to local maneuver than to any general pattern of enemy disintegration. General Barton reluctantly ordered both regiments to suspend major attacks and take two or three days to reorganize and consolidate. Unable to strengthen the regiments other than with individual replacements, General Barton turned to a substitute for increased troops—decreased zones of action. Having reached the high ground about Gut Schwarzenbroich, the 8th Infantry now would derive some benefit from a boundary change made earlier by the VII Corps which transferred a belt of forest northeast of Gut Schwarzenbroich to the adjacent 1st Division.4 This reduced the width of the 8th Infantry's zone by some 800 yards. To close the gap between the 8th and 22d Infantry Regiments and enable the 22d to concentrate on a thousand-yard front at Grosshau, General Barton directed that the 12th Infantry prepare to move northward into the center of the division zone. Once the 22d Infantry had taken Grosshau and turned northeastward along an improved [468] road net toward Dueren, the 12th Infantry might assist an attack on Gey, the last major village strongpoint that could bar egress from the forest onto the Roer plain.

For three days, 26 through 28 November, the 4th Division paused. Yet for only one regiment, the 8th Infantry, was there any real rest. Aside from the usual miseries of mud, shelling, cold, and emergency rations, the 8th Infantry engaged primarily in patrolling and in beating off platoon-sized German forays. These augured ill for the future, for indications were clear that the enemy had by 27 November begun to move in the 353d Division to relieve the 344th.5 Having cleared the 22d Infantry's right flank by nightfall of 26 November, the 12th Infantry the next day relinquished its positions to a battalion from the V Corps. Dropping off one battalion as a division reserve, a luxury General Barton had not enjoyed since the start of the November offensive, the 12th Infantry on 28 November attacked to sweep the gap between the 8th and 22d Infantry Regiments. Not until the next day was this task completed. In the meantime, most men of the 22d Infantry were scarcely aware that the division had paused. For two of the three days, the regiment made limited attacks with first one company then another, in order to straighten the line and get all units into position for a climactic attack on Grosshau. One of these attacks inspired an intrepid performance from an acting squad leader, Pfc. Marcario Garcia. Although painfully wounded, Garcia persistently refused evacuation until he had knocked out three machine gun emplacements and another enemy position to lead his company onto its objective.6 Undoubtedly aware that an attack on Grosshau was impending, the Germans concentrated their mortar and artillery fire against the 22d Infantry. In two days of admittedly limited operations, the 22d Infantry suffered over 250 casualties. Despite a smattering of replacements, two companies had less than fifty men each in the line. The subject of replacements was a matter upon which the 4th Division by this time could speak with some authority, for during the month of November the division received as replacements 170 officers and 4,754 enlisted men. Most commanders agreed that the caliber of replacements was good.7 "They had to be good quick," said one platoon leader, "or else they just weren't. They sometimes would take more chances than some of the older men, yet their presence often stimulated the veterans to take chances they otherwise would not have attempted."8 Integrating these new men into organizations riddled by losses among squad and platoon leaders was a trying proposition. "When I get new men in the heat of battle," one sergeant said, "all I have time to do is . . . impress them that they have to remember their platoon number, and tell them to get into the nearest hole and to move out when the rest of us move [469] out."9 That heavy casualties would strike men entering combat under conditions like these hardly could have been unexpected. Indeed, so unusual was it to get a packet of replacements into the line without incurring losses that companies noted with pride when they accomplished it. So short was the front-line stay of some men that when evacuated to aid stations they did not know what platoon, company, or even battalion and sometimes regiment they were in. Others might find themselves starting their first attack as riflemen and reaching the objective as acting squad leaders.

Most of the newcomers were reclassified cooks, clerks, drivers, and others combed from rear echelon units both in the theater and in the United States. Somewhat typical was Pvt. Morris Sussman: From a Cook and Baker's School in the United States, Private Sussman had been transferred for 17 weeks' basic infantry training, then shipped overseas. Docking in Scotland in early November, he found himself in the Huertgen Forest by the middle of the month. At the Service Company of the 22d Infantry someone took away much of what was called "excess equipment." From there Sussman and several other men "walked about a mile to some dugouts." At the dugouts the men received company assignments, and their names and serial numbers were taken down. A guide then led them toward the front lines. On the way they were shelled and saw a number of "Jerry" and American dead scattered through the forest. Private Sussman said he was "horrified" at the sight of the dead, but not as much as he might have been "because everything appeared as if it were in a dream."

At a front line company, Sussman's company commander asked if he knew how to operate a radio. Sussman said no. Handing him a radio, the captain told him: "You're going to learn." Learning consisted of carrying the radio on his back and calling the captain whenever he heard the captain's name mentioned over the radio. For all his ignorance of radios, Sussman felt good. Being a radio operator meant he would stay with the captain and back in the States he had heard that captains stayed "in the rear." Subsequently, Private Sussman said, he "found out different."10 In the kind of slugging match that the Siegfried Line Campaign had become, little opportunity existed, once all units were committed, for division commanders to influence the battle in any grand, decisive manner. That was the situation General Barton had faced through much of the Huertgen Forest fighting. But as of 28 November, matters were somewhat different. Having narrowed his regimental zones of action, Barton had managed for the first time to achieve a compact formation within a zone of reasonable width. Looking at only this facet of the situation, one might have anticipated an early breakout from the forest. Unfortunately, General Barton could not ignore another factor. By this time his three regiments were, in effect, masqueraders operating under the assumed names of the three veteran regiments which had come into the forest in early November. In thirteen days some companies had run through three and four company commanders. Staff sergeants and sergeants commanded most of the rifle platoons. The few officers still running platoons usually were either replace- [470] ments or heavy weapons platoon leaders displaced forward. Most squad leaders were inexperienced privates or privates first class. One company had only twenty-five men, including replacements. Under circumstances like these, command organization hardly could be effective. Men and leaders made needless mistakes leading to more losses and thereby compounded the problem. This was hardly a division: this was a conglomeration. One man summed up the campaign and the situation in a few words: "Then they jump off again and soon there is only a handful of the old men left."11

This was how it was. Yet a job had to be done, and these were the men who had to do it. General Barton issued his orders. His subordinates passed them down the line. "Well, men," a sergeant said, "we can't do a —— thing sitting still."12 He got out of his hole, took a few steps, and started shooting. His men went with him. That was how this weary division resumed the attack. The critical action was at Grosshau, for here was the ripest opportunity to break out of the forest and at last bring an end to these seemingly interminable platoon-sized actions. If Colonel Lanham's 22d Infantry could capture Grosshau, the division finally would be in a position to turn its full force northeastward on Dueren along a road net adequate for a divisional attack. Already commanders at corps and army level were making plans to strengthen the division for a final push. Except for CCR, which was fighting with the V Corps, the entire 5th Armored Division was transferred to the VII Corps and CCA earmarked for attachment to the 4th Division.13 The 22d Infantry commander, Colonel Lanham, intended to attack early on 29 November at the same time the V Corps was striking the neighboring village of Kleinhau. For all their proximity, Grosshau and Kleinhau were different types of objectives. Kleinhau is on high ground, while Grosshau nestles on the forward slope of a hill whose crest rises 500 yards northeast of the village. Appreciating this difference and all too aware of the carnage that had resulted on 25 November when the regiment had tried to move directly from the woods into Grosshau, Colonel Lanham planned a wide flanking maneuver through the forest to the north in order to seize the dominating ridge. Thereupon the enemy in Grosshau might be induced to surrender without the necessity of another direct assault across open fields. German shelling interrupted attack preparations early on 29 November, so that the 5th Armored Division's CCR under the V Corps already was clearing Kleinhau before Lanham's flanking force even began to maneuver. Perhaps because CCR was getting fire from Grosshau, the 4th Division's chief of staff, Col. Richard S. Marr, intervened just before noon in the name of the division commander to direct that Grosshau be taken that day.14 Because Colonel Lanham could not guarantee that his delayed flanking maneuver would bring the downfall of Grosshau immediately, Colonel Marr's instruction meant in effect that he had to launch a direct assault against the village. [471] Too late to recall his flanking force, he had only one battalion left. This was the 2d Battalion under Major Blazzard, which during the attack through the forest had borne responsibility for the regiment's exposed right flank and therefore had sustained correspondingly greater losses than the other battalions. Indeed, at this point, the 2d Battalion, 22d Infantry, was easily as weak as any battalion in the entire 4th Division. To make matters worse, Major Blazzard had only one company in a position to attack immediately.

Quickly scraping together two tanks and a tank destroyer to support this company, Blazzard ordered an attack on Grosshau down the main road from the west. Within an hour after receipt of the chief of staff's directive, the attack jumped off. Within fifteen more minutes, the infantry was pinned down in the open between the woods and the village and the two tanks had fallen prey to German assault guns. Two hours later Major Blazzard assembled eight more tanks of the attached 70th Tank Battalion and sent them around the right flank of the infantry to hit the village from the southwest. Two of these tanks hit mines at the outset. The others could not get out of the woods because of mine fields and bog. The sun was going down on an abject failure when two events altered the situation. In the face of persistent resistance, Colonel Lanham's flanking battalion finally cut the Grosshau-Gey highway in the woods north of Grosshau, and as night came one battalion emerged upon the open ridge northeast of Grosshau, virtually in rear of the Germans in the village. Almost coincidentally, a covey of tanks and tank destroyers took advantage of the gathering darkness to reach Major Blazzard's stymied infantry along the road into Grosshau from the west. Firing constantly, the big vehicles moved on toward the village. The infantry followed. In a matter of minutes, the resistance collapsed. By the light of burning buildings and a moon that shone for the first time since the 4th Division had entered the Huertgen Forest, Major Blazzard's infantry methodically mopped up the objective. More than a hundred Germans surrendered. In a larger setting, Grosshau was only a clearing in the Huertgen Forest, the point at which the 22d Infantry at last might turn northeastward with the rest of the 4th Division to advance more directly toward the division objective of Dueren. During the night of 29 November, General Barton directed the shift. The first step was to sweep the remainder of the Grosshau clearing and to occupy a narrow, irregular stretch of woods lying between Grosshau and Gey. This accomplished, CCA of the 5th Armored Division might be committed to assist the final drive across the plain from Gey to Dueren and the Roer River. To help prepare the way for CCA, General Barton attached the combat command's 46th Armored Infantry Battalion to the 22d Infantry. Colonel Lanham in turn directed the armored infantry to move the next day, 30 November, to Hill 401.3, an open height commanding the entire Grosshau clearing, whose lower slopes the 5th Armored Division's CCR had occupied temporarily in conjunction with the attack on Kleinhau. From Hill 401.3 the armored infantry was to attack into the woods cast of the clearing in order to block the right flank of the 22d Infantry when that regiment turned northeast toward Gey. [472] Colonel Lanham held one battalion of his own infantry in reserve, directed another to attack alongside the Grosshau-Gey highway to gain the woods line overlooking Gey, and ordered Major Blazzard's unfortunate 2d Battalion to cross 800 yards of open ground cast of Grosshau, enter the woods, and then turn northeastward along the right flank of the battalion that was moving on Gey.

The direct move through the narrow stretch of woods to Gey was blessed with success. Behind a bank of crossfire laid down by fourteen tanks and tank destroyers advancing on either flank of the infantry, a battalion of the 22d Infantry by nightfall on 30 November was entrenched firmly at the edge of the woods overlooking the village. Things did not go as well for the rest of the regiment and the attached armored infantry. As men of the 46th Armored Infantry Battalion moved up Hill 401.3, German fire poured down the open slopes. All day long the armored infantry fought for the hill and as night came finally succeeded through sheer determination. Yet in one day this fresh battalion lost half its strength.15 Fire from this same hill and from the edge of the woods east of Grosshau made the attempted advance of Major Blazzard's 2d Battalion, 22d Infantry, just as difficult. The edge of the woods was to have been Blazzard's line of departure. In reality, the battalion fought all day to get to this line. Upon gaining it, the two companies that made the attack had between them less than a hundred men. That this little force could continue northeast through the woods to come abreast of the battalion which had gained the woods line overlooking Gey was a patent impossibility. Early the next day, 1 December, Colonel Lanham reluctantly relinquished his reserve to perform this task. Now that Hill 401.3 was in American hands, the job was easier. A favorable wind that blew a smoke screen across open ground leading from Grosshau to the woods also helped. By nightfall the reserve battalion had reached the woods line overlooking Gey, refused its flank, and dug in. At long last, sixteen days after the start of the November offensive, the 22d Infantry—or what was left of it—was all the way through the Huertgen Forest. Success, yes; but how to maintain it? Every man of the rifle battalions was hugging a foxhole somewhere, yet the line was desperately thin. As a last resort, Colonel Lanham robbed his Antitank, Headquarters, and Service Companies of all men that possibly could be spared to form a reserve. He could not have been more prescient, for early the next morning, 2 December, the Germans counterattacked. In estimated company strength, the Germans struck southeast from Gey, quickly penetrated the line, surrounded a battalion command post, and gave every indication of rolling up the front. Only quick artillery support and commitment of the composite reserve saved the day. Had events followed earlier planning, the 5th Armored Division's CCA now would have joined the 22d Infantry and the rest of the 4th Division for the push across the Roer plain to Dueren. But one look at the condition of the 22d Infantry would have been enough to [473] convince anyone that this regiment could contribute little if anything to a renewed push. And the sad fact was that the 22d Infantry was a microcosm of the entire 4th Division.

In the center of the division's zone, the 12th infantry had been attacking in the woods west of Gey ever since first moving on 28 November to close the gap between the other two regiments. On 30 November the 12th Infantry had swept forward more than a thousand yards to gain the woods line west of Gey, whence the regiment was to make the main effort in an attack against that village. But the 12th Infantry had entered the Huertgen Forest fighting ten days ahead of the rest of the division; after twenty-six days of hell, artillery fire alone against the regiment's woods line position was enough to foster rampant disorganization. On the 4th Division's north wing, the 8th Infantry had attacked on 29 November in conjunction with the general renewal of the offensive. The objective was a road center at the eastern edge of the forest about a settlement called Hof Hardt. One day's action was enough to confirm the worst apprehensions about the enemy's forming a new line during the three-day pause that had preceded the attack. Not until 1 December did Colonel McKee's regiment make a genuine penetration, and then the companies were too weak to exploit it. Company I, for example, was down to 21 men; Company C had but 44 men; and some other companies were almost as weak. Total gains in three days were less than a thousand yards, and the regiment had almost as far again to go before emerging from the forest. Since 16 November the 4th Division had fought in the Huertgen Forest for a maximum advance of a little over three miles. Some 432 men were known dead and another 255 were missing. The division had suffered a total of 4,053 battle casualties, while another estimated 2,000 men had fallen to trench foot, respiratory diseases, and combat exhaustion. Thus the 4th Division could qualify for the dubious distinction of being second only to the 28th Division in casualties incurred in the forest.16 Late on 1 December General Barton spoke in detail to the VII Corps commander, General Collins, about the deplorable state of the division. The 22d Infantry, in particular, he reported, had been milked of all offensive ability. Replacements were courageous, but they did not know how to fight. Since all junior leadership had fallen by the way, no one remained to show the replacements how. General Collins promptly ordered General Barton to halt his attack. As early as 28 November, both the VII Corps and the First Army had noted the 4th Division's condition and had laid plans for relief. On 3 December a regiment of the 83d Division brought north from the VIII Corps sector in Luxembourg was to begin relief of the 22d Infantry. In the course of the next eight days, the entire 4th Division was to move from the Huertgen Forest and arrive in Luxembourg just in time for the counteroffensive in the Ardennes. Though the slowness of the advance through the Huertgen Forest was disappointing, it was to the north, in that [474] region where the forested hills merge with the Roer plain, that the issue of whether the VII Corps had purchased a slugging match or a breakthrough would be decided. Here, in a sector no more than three and a half miles wide, extending from within the forest near Schevenhuette to the Inde River along the south boundary of the Eschweiler-Weisweiler industrial triangle, General Collins was making his main effort. Here he had concentrated an infantry division, the 1st, reinforced by a regiment, the 47th Infantry, and backed up by an armored division, the 3d.

After four days of severe fighting, by nightfall of 19 November, there were limited grounds for encouragement in this sector. Given one or two days of good weather, the corps commander believed, "the crust could be smashed."17 On the 1st Division's left flank, the 104th Division had assisted the main effort by seizing high ground near Stolberg and now could start to clear the adjacent industrial triangle that lay between the 1st Division and the Ninth Army. A combat command of armor had cleared the last Germans from the Stolberg Corridor up to the base of the Hamich ridge, which stood astride the 1st Division's axis of advance. The 1st Division's 16th Infantry had taken the village of Hamich and a dominating foothold upon the Hamich ridge at Hill 232. In holding these gains, the 16th Infantry had decimated the fresh 47th Division's 104th Regiment, which had rushed to the aid of the faltering 12th Division. In the forest near Schevenhuette, the 26th Infantry now stood a stone's throw from the Laufenburg, the castle halfway through this portion of the Huertgen Forest. So fierce had been the conflict to this point that the 1st Division commander, General Huebner, saw now that he could not afford the luxury of withholding reserves for exploitation upon the Roer plain. So obdurate were the Germans and so intractable the weather and terrain that he might need everything he had even to reach the plain. Huebner ordered his reserve regiment, the 18th Infantry, into the center of his line to make what was in effect a new divisional main effort. The fresh regiment was to attack northeastward astride the Weh Creek to clear the road net bordering the creek and seize the industrial town of Langerwehe, the last obstacle barring egress from the forest onto the plain. Originally scheduled to take Langerwehe and the neighboring town of Juengersdorf, the 26th Infantry in the thick of the forest on the division's right wing now was to make a subsidiary effort. This regiment was to take Juengersdorf and a new objective, the village of Merode at the eastern edge of the forest near the boundary with the 4th Division. Having cleared Hamich and Hill 232, the remaining organic regiment, the 16th Infantry, was to advance close alongside the left flank of the newly committed 18th Infantry through broken terrain lying between the forest and the Eschweiler-Weisweiler industrial triangle. This would bring the 16th Infantry to the edge of the plain along the Weisweiler-Langerwehe highway close on the left of the center regiment. A change in plan instituted by the corps commander also affected the 1st Division. Attached to the 1st Division, the 47th Infantry (9th Division) was to continue as originally directed to sweep the Hamich ridge extending northwest [475] from Hill 232. Under the original plan, this regiment then was to have passed to control of the 104th Division for seizing a narrow strip of land just south of the Inde River, lying between two parallel rail lines and embracing the industrial towns of Huecheln and Wilhelmshoehe. Apparently in anticipation of communications problems because of the Inde, General Collins now decided to leave the 47th Infantry under control of the 1st Division until these towns had fallen. He shifted the interdivision boundary accordingly north to the Inde.18

This boundary change effected, the territory left to be cleared by the corps main effort before reaching the Roer plain took the form of a giant fan. The outer rim extended from Nothberg, at the northern tip of the Hamich ridge, a town still assigned to the 104th Division, northeastward through Huecheln to Wilhelmshoehe, thence east to Langerwehe and southeast to Juengersdorf and Merode. At the conclusion of the renewed attack, the 47th Infantry and the 1st Division's three organic regiments would be arrayed along the rim of the fan on the threshold of the plain.19 A battalion of the 18th Infantry gained a leg on the renewed offensive during the afternoon of 19 November by driving on the village of Wenau, less than a mile northeast of Hamich on the route to Langerwehe. Temporarily off balance in the wake of the defeats at Hamich and Hill 232, the Germans could not genuinely contest the move except with mortar and artillery fire. Although this was sufficient to deny occupation of Wenau until early on 20 November, the 18th Infantry then had a solid steppingstone for launching the divisional main effort toward Langerwehe. Capture of Wenau also meant an assist to the 26th Infantry in clearing the Weh Creek highway and thereby gaining an adequate supply route to replace the muddy, meandering firebreaks and trails that had served this regiment during the first four days of attack. Assured of this supply route, the 26th Infantry commander, Colonel Seitz, renewed his drive on 20 November against the Laufenburg and the four wooded hills surrounding the castle. First the regiment had to beat off a counterattack by a battalion of the 47th Division's 115th Regiment, sister battalion to that which had lost heavily in a similar maneuver the day before. In the end, this meant an easier conquest of the castle, for Colonel Seitz sent a battalion close on the enemy's heels before the defenders of the castle could get set. By nightfall Colonel Seitz had pushed a battalion beyond the castle along a forest trail leading east toward Merode. For two more days, through 22 November, the 26th Infantry continued to push slowly eastward through the dank forest with two battalions and to refuse the regimental right flank with the other. The operation was monotonously the same. You attacked strongpoint after strongpoint built around log pillboxes, scattered mines, foxholes, and barbed wire. You longed for tank support but seldom got it. You watched your comrades cut down by shells bursting in the trees. Drenched by cold rain, you slipped and slithered in ankle-deep mud. [476] Every advance brought its counterattack. When dusk approached you stopped early in order to dig in and thatch your foxhole with logs before night brought German infiltration and more shellfire.

The 26th Infantry nevertheless made steady progress. Indeed, by nightfall of 22 November, prospects were bright for sweeping a remaining mile of forest and emerging at last upon the Roer plain at Merode. Arrival of a contingent of the 4th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron on the regiment's right flank to refuse the flank and maintain contact with the 4th Division meant that Colonel Seitz would have the full weight of all three of his battalions for the final push. Only from a regimental viewpoint, however, was the 26th Infantry ready to push out of the forest. In the division picture, General Huebner was concerned lest Colonel Seitz get too far beyond his neighbors. On the left, the 18th Infantry had become heavily engaged in the valley of the Weh Creek; and the 4th Division's 8th Infantry at Gut Schwarzenbroich still was a long way from the eastern skirt of the forest. General Huebner was perturbed particularly that the Germans might push through the 8th Infantry down Road U to Schevenhuette to cut off the entire 1st Division.20 He directed that until further notice Colonel Seitz make only limited attacks, some designed to assist the 18th Infantry. After a relatively painless conquest of Wenau, the 18th Infantry had stepped into hot water. "Shove off as fast as you can," General Huebner had told the 18th Infantry commander, Colonel Smith. "[If you] run into resistance, bypass it and go around."21 This might have worked except for two factors. First, the Germans during the night had hurriedly shored up the depleted 104th Regiment with the 47th Division's 147th Engineer Battalion. The second was the nature of the next objective, the village of Heistern, about 500 yards beyond Wenau. Like Wenau, Heistern is perched on the western slope of the Weh Creek valley. Bypassing it was next to impossible, for by little more than rolling grenades down the slope the Germans in the village could deny movement up the valley toward Langerwehe. From Heistern they enjoyed almost as great an advantage over the 16th Infantry's sector to the west. "We need Heistern," said one officer of the 16th Infantry, "before we can go anywhere . . . ."22 The fight for Heistern might have been as lengthy and as costly as the fight for Hamich except that here the Germans had no Hill 232 from which to pinpoint the slightest movement. Employing artillery and tank fire against fortifications on the fringe of the village, a battalion of the 18th Infantry by nightfall had reached a main road junction in the center of the village. Still the Germans clung like cockleburs to the northern half. During the night, the commander of the enemy's 104th Regiment, Col. Josef Kimbacher, personally led his training and regimental headquarters companies into Heistern to reinforce what was left of the German garrison. At 0330, 21 November, behind damaging concentrations of mortar and artillery fire, Colonel Kimbacher counterattacked. Not until short- [477] ly, before daylight did the Americans beat off the enemy and spill over into the northern half of the village. They took about 120 prisoners, including Colonel Kimbacher, and subsequently counted 250 German dead. Taking both Wenau and Heistern cost the 18th Infantry 172 casualties. As often happened, the Germans in a swift and futile counterattack had wasted the very troops who in a stationary defense might have prolonged the fight considerably.23

Even before the attack for Heistern, the 18th Infantry had sent another battalion on 20 November to cross the Weh Creek and advance on Langerwehe along a wooded ridge marking the east slope of the valley. Having no Heistern to contend with, this battalion moved fast until on 21 November the leading company smacked into a real obstacle, Hill 207. Not quite a mile northeast of Heistern, wooded, and with an escarpment for a southern face, Hill 207 dominates the Weh Creek valley from the east as Heistern does from the west. Pounded by artillery fire in disturbing proportions and raked by small arms fire from atop the escarpment, the first company to test the hill fell back under severe losses. Eschewing another direct assault, the battalion commander the next day attempted to maneuver through the woods to take the hill from a flank. Maneuver in the Huertgen Forest, he soon discovered, was a complex and costly commission. Not for another twenty-four hours, 23 November, was this battalion able to get into position for a vigorous flanking attack that at last carried the hill. Having lost Hill 207, the Germans had no real anchor short of Langerwehe itself upon which to base a further defense along the east slope of the Weh Creek valley. Although they made a try a few hundred yards beyond Hill 207 at Schoenthal, they could hold onto this hamlet only through the night. On 24 November the battalion of the 18th Infantry pushed on northeastward parallel to the valley. Except for minor strongpoints, a wooded door to Langerwehe stood ajar. Like the 26th Infantry deeper within the woods, the battalion of the 18th Infantry could not pursue its advantage. The most elementary caution would proscribe sending an understrength battalion into a town the size of Langerwehe unless a better supply route than muddy firebreaks was available. To the chagrin of the regimental commander, Colonel Smith, that was the supply situation this battalion had to face: the Weh Creek highway could not be used until both east and west slopes had been cleared. On the west slope, another battalion of the 18th Infantry had run into trouble. This was Colonel Smith's reserve battalion, committed through Heistern at midday on 21 November to project the left prong of the regiment's double thrust on Langerwehe. Lying between the reserve battalion and the objective were two obstacles: a rectangular patch of woods covering the western slope of the valley and a dominating height at the northern end of the woods no more than half a mile from Langerwehe, Hill 203. Getting through the woods alone was bad enough. Hill 203 was worse. The critical importance of Hill 203 obviously was not lost on the Germans. Topped by an observation tower and a religious shrine, the hill is bald once the [478] rectangular patch of woods gives out on the southern slope. From the hill the enemy controlled both the Weh Creek highway and another road running from Heistern across the crest of the hill into Langerwehe. Without Hill 203, the Germans could not hope to hold onto Langerwehe. Without Hill 203, the 18th Infantry could not hope to take the town.

Admonished by General Huebner not to commit full strength against Hill 203 because "Langerwehe is where your big fight is",24 Colonel Smith's reserve battalion at first sent only a company against the hill. No sooner had men of this company emerged from the trees toward the crest late on 23 November than small arms and artillery fire literally mowed them down. This was enough to convince Colonel Smith that he had a big fight here, no matter what he might run into later in Langerwehe. "The 1st Battalion," Colonel Smith reported, "will be unable to get to Hill 203 until we get armor."25 Getting tanks forward over roads literally under the muzzles of German guns obviously would be toilsome. Through the night of 23 November and most of the next day, attached tanks of the 745th Tank Battalion tried to reach Hill 203. Slowed by mud, at least two were picked off by antitank guns concealed on the hill. Not until too late in the afternoon to be of any real assistance on 24 November did the tanks gain the woods line. Neither could tactical aircraft help, for the weather was rainy and dismal. Even the contribution of the artillery was limited, because the fighting was at such close quarters. Though Colonel Smith called on the battalion of the 18th Infantry on the other side of the valley to help, that battalion soon had its hands full with a counterattack by contingents of the 47th Division's 115th Regiment. Supported by two tanks, one company in midafternoon of the next day, 25 November, at last began to make some progress against Hill 203. Although the enemy knocked out one of the tanks, a rifle platoon managed to gain a position near the crest of the hill. All through the night and the next day this little band of men clung to the hillside. Yet for all their courage and pertinacity, these men scarcely represented any genuine conquest of Hill 203. It would take more than a platoon to carry this tactical prize. Concurrently with the fight in the forest and along the Weh Creek valley, the 16th Infantry and the attached 47th Infantry had been extending the 1st Division's battle line to the west and northwest. The 47th Infantry was to attack northwest along the Hamich ridge, thence northeast through Huecheln and toward Wilhelmshoehe in a scythelike pattern designed to place the attached regiment eventually on a line with the rest of its foster division. Attacking northeast from Hamich, the 16th Infantry was to serve as a bridge between this operation and the divisional main effort of the 18th Infantry up the Weh Creek valley. The 16th Infantry's first objective was high ground about a castle, the Roesslershof, at the edge of a patch of woods south of the Aachen-Dueren railroad. The sector through which the 16th and 47th Infantry Regiments were to attack [479] took the form of a parallelogram, bounded on the southwest by the Hamich ridge, on the northwest by the Inde River, on the northeast by the Weisweiler-Langerwehe highway, and on the southeast by the Weh Creek. The parallelogram embraced the purlieus of the Huertgen Forest. A nondescript collection of farms, villages, industrial towns, railroads, scrub-covered hills, and scattered but sometimes extensive patches of woods, this region would offer serious challenges to an attacker, particularly during the kind of cold, wet weather late November had brought. Indeed, these troops who would fight here where the Huertgen Forest reluctantly gives way to the Roer plain would experience many of the same miseries as did those who fought entirely inside the forest. Yet they might be spared the full measure of the forest's grimness. Sometimes they could spend a dry night in a damaged house, and most of the time they could see the sky.

Both regiments began to attack during the afternoon of 19 November after the 16th Infantry's decisive victory at Hamich and Hill 232. Like the 18th Infantry at Wenau, the 16th Infantry found that closely following up the defeat of the enemy's 104th Regiment was a good stratagem. By the end of the day the regiment's leading battalion had reached the eastern part of the Bovenberger Wald, a patch of woods lying in the middle of the parallelogram. The next day the 16th Infantry would be ready to advance close alongside the 18th Infantry's left flank to cover the less than two miles to Roesslershof Castle. Given flank protection by the advance of the 16th Infantry, a battalion of the 47th Infantry attacked northwest along the Hamich ridge from Hill 232 with an eye toward Hills 187 and 167, which mark the terminus of the ridge a few hundred yards short of Nothberg. The Germans on Hill 187 were part of the 47th Division's 103d Regiment. Having become embroiled earlier in the fight to keep the 3d U.S. Armored Division out of the villages southwest of Hill 187, the regiment had incurred serious losses. Yet when afforded advantageous terrain like Hill 187 and nearby Hill 167, even a small force was capable of a stiff fight. This the 47th Infantry discovered early on 20 November. Commanded by Lt. Col. James D. Allgood, a battalion attacked Hill 187 repeatedly but without appreciable success. Hill 187, the Germans recognized, was worth defending, for from it they could look down upon three US divisions—the 104th in the Eschweiler-Weisweiler industrial complex, the 3d Armored in the Stolberg Corridor, and that part of the 1st Division in the parallelogram.26 As the fighting stirred again on Hill 187 the next day, 21 November, the 47th Infantry commander, Colonel Smythe, sent another battalion through the Bovenberger Wald to the east of the hill. By taking the settlement of Bovenberg at the northern tip of the woods, this battalion would virtually encircle both Hills 187 and 167 in conjunction with a concurrent attack by a unit of the 104th Division on the town of Nothberg. At the same time, an advance on Bovenberg would pave the [480] way for executing the 47th Infantry's next mission of taking the industrial towns of Huecheln and Wilhelmshoehe, which lie north of Bovenberg.

The idea was good. But it would not work without first wresting from the Germans the dominating observation from Hills 187 and 167. Tanks trying to accompany the infantry along a road skirting the western edge of the trees found the going next to impossible because of felled trees and antitank fire from the hills. In the thin northern tip of the woods, the infantry too was exposed to punishing shellfire obviously directed from the heights. The leading company nevertheless prepared to debouch from the wood to strike a strongpoint in the main building of a dairy farm on the edge of Bovenberg. Despite grazing small arms fire, one platoon actually reached the dairy, only to fall back in the face of hand grenades dropped from second story windows. Protected by thick brick walls, the Germans inside called down artillery fire on their own position. Another platoon which penetrated to a nearby copse could get no farther and could withdraw only by means of a smoke screen. Even then only 6 men emerged unscathed, though they brought with them 15 or 20 wounded. The company lost 35 men killed in a matter of a few hours. All officers except the company commander were either killed or wounded. The company had only 37 men left. In the meantime, Colonel Allgood's battalion was having as much trouble as before with Hill 187. Despairing of taking the hill with usual tactics, the 1st Division commander, General Huebner, turned in midafternoon of 21 November to the same pattern he had used two days before against Hill 232. As soon as Colonel Allgood's men could pull back a safe distance, 1st Division artillery was to fire a TOT. Hearing of this plan, the corps commander intervened. Because he deemed the effort too modest, General Collins directed assistance by all VII Corps artillery and any divisional artillery within effective range. Within ten minutes after the 1st Division's organic 155-mm. howitzer battalion had zeroed in on the hill, the 1st Division's artillery headquarters had transmitted the adjustment to all other firing battalions, At 1615, an awesome total of twenty battalions, including a 240-mm. howitzer battalion and two 8-inch gun battalions, fired for three minutes upon a target area measuring approximately 300 by 500 yards. "It just literally made the ground bounce," said one observer.27 Well it might have; for this ranked among the most concentrated artillery shoots during the course of the war in Europe. For some unexplained reason, Colonel Allgood made no immediate effort to occupy the hill. Instead, the 47th Infantry's Cannon Company interdicted the target through the night. The next morning, 22 November, a patrol that crept up the hill found only enemy dead and about eighty survivors who still were too dazed to resist. Another patrol discovered that the enemy had abandoned Hill 167. Rather than renew the drive on the dairy at Bovenberg and continue along that route to the next objectives of Huecheln and Wilhelmshoehe, the 47th Infantry commander, Colonel Smythe, asked permission to move into the 104th Division's zone at Nothberg and attack [481] from that direction. The 104th Division had occupied Nothberg during the morning of 22 November. Because the route via Bovenberg was more a trail than a road, the 47th Infantry's line of communications eventually would run through Nothberg anyway.28

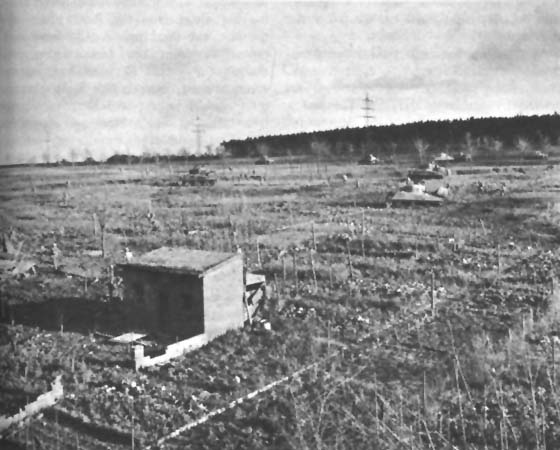

Although granted this permission, Colonel Smythe was reluctant to leave intact a strongpoint like the dairy at Bovenberg. This time the attacking company took a leaf from the successful artillery bombardment of Hills 232 and 187. After an 8-inch gun battalion had scored at least twenty-six hits on the dairy, the riflemen attacked. The artillery alone, they discovered, had been enough. The Germans had fled. To make the main drive between the parallel rail lines toward Huecheln, Colonel Smythe early on 23 November committed his reserve battalion under Lt. Col. Lewis E. Maness. Canalized by the railroads into an attack zone only 500 yards wide, Colonel Maness leaned heavily in his attack upon supporting fires. Artillery fired a ten-minute concentration upon the western edge of Huecheln, 81-mm. mortars laid a smoke screen, a platoon of tanks accompanied the infantry, and tank destroyers and machine guns spewed overhead fire from the eastern edge of Nothberg. Unfortunately, Germans of the 12th Division's 27th Fusilier Regiment had shunned the obvious defensive spot along the fringe of Huecheln in favor of open ground west of the town. Though they had dug an elaborate zigzag trench system protected by mines, not a stray clod of earth betrayed their positions. Dependent upon an observation post in Nothberg, a mile away, Colonel Maness had not accurately determined the enemy's line. Most of the supporting fire was over. The enemy for his part had a towering observation post atop a slag pile in the 104th Division's zone north of the northern railroad. On 23 November Colonel Maness' battalion hardly got past the eastern edge of Nothberg. Renewing the attack the next morning, Maness could detect nothing in the passing of night to alter the picture. Unknown to Colonel Maness, his superiors were concocting a formula which might prove just what this particular problem required. For several days the corps commander, General Collins, had been considering the idea of employing his armored reserve. Although Collins hardly could have entertained any illusions that a breakthrough calling for armored exploitation was near, he did see a possibility that an assist from armor might provide the extra push necessary to get onto the Roer plain. Impressed by unexpected celerity in the 104th Division's fight to clear the Eschweiler-Weisweiler industrial triangle, he had on 22 November increased that division's responsibility beyond the industrial triangle to the Roer. A byproduct of the change was an opportunity—almost a need—for a short, quick thrust by a small increment of armor. In directing the 104th Division to continue to the Roer, General Collins had extended that division's boundary east from Weisweiler to include a crossing of the Inde River along the Aachen-Cologne autobahn. A quick jab by armor through Huecheln and Wilhelmshoehe to the Frenzerburg, a medieval castle crowning a gentle hill a mile beyond Wilhelmshoehe, would enable the armor to control the [482] INFANTRY AND TANKS move through small truck farms near Huecheln. 104th Division's Inde crossing site by fire.29 Shortly before noon on 24 November General Collins attached Colonel Maness' battalion of the 47th Infantry to the 3d Armored Division as the infantry component of a task force to make the thrust to the Frenzerburg. Other components of the task force were a medium tank battalion from the 3d Armored Division's CCA, an armored field artillery battalion, and increments of tank destroyers and armored engineers. All were under the command of Lt. Col. Walter B. Richardson.30 Task Force Richardson's first attack in midafternoon of 24 November ran into trouble at the start. Two medium tank companies in the lead blundered into a mine field. Attempts to find a path around the mines usually ended in tanks [483] bogging deep in mud. One tank actually sank so deep that mud came up on the hull.

As dusk approached, the armored engineers at last managed to clear a path. The enemy's observation severely restricted by gathering darkness, the attack began to roll. Tanks and infantry together stormed across the zigzag trenches into Huecheln. By 2100 (24 November) the town was clear. A hundred Germans were on their way to prisoner cages. Neither Huecheln nor the next town of Wilhelmshoehe are on commanding ground, so that in renewing the attack on 25 November Task Force Richardson strove toward more dominating terrain along the Weisweiler-Langerwehe highway from which to attack the Frenzerburg. The Germans employed fire from self-propelled guns across the Inde at Weisweiler and from small arms and mortars among the houses and factories of Wilhelmshoehe. During the course of the day 200 Germans of the 12th Division's 27th Regiment and the 47th Division's 103d Regiment were captured. So long as tanks and infantry enjoyed the protection of buildings, American losses were moderate; but once in the open, casualties rose alarmingly. An attempt on the right to reach the highway stalled when the bulk of one tank company bogged in the mud. At one time eighteen tanks were immobilized. A thrust on the left ran into intense fire upon emerging from Wilhelmshoehe. German guns knocked out three tanks, and small arms and artillery fire virtually destroyed an infantry company. That company had but thirty-five men left. The infantry commander, Colonel Maness, appealed for reinforcement before striking into the open for the Frenzerburg. The officers of Task Force Richardson had ample justification for concern about moving alone onto the Roer plain. On the left, the task force would have some protection from the Inde River, even though the 104th Division had not yet come abreast; but on the right, the task force would be exposed to counterattack from Langerwehe. Nothing existed at this time (25 November) to indicate that the 1st Division's 18th Infantry soon might push the enemy off Hill 203 and get into Langerwehe. Neither was there any hope that the 1st Division's 16th Infantry soon might come abreast along the Weisweiler-Langerwehe highway between the task force and the 18th Infantry, for on 25 November the 16th Infantry was having trouble holding onto terrain already taken. This was high ground about Roesslershof at the edge of a patch of woods southeast of Wilhelmshoehe. After the paths of the 16th and 47th Regiments had diverged on 19 November in the Bovenberger Wald, the 16th Infantry had delayed its attack until the 18th Infantry had secured Heistern, the village alongside the Weh Creek valley which dominated the 16th Infantry's route of advance. Although able to make a genuine attack on 23 November, the regiment had been handicapped because General Huebner had withdrawn one battalion as a division reserve. Not until near nightfall on 23 November had the 16th Infantry pushed back stubborn remnants of the 47th Division, called Kampfgruppe Elsenhuber, and broken into Roesslershof. From that point the regiment had been involved in repulsing counterattacks and in clearing a patch of woods between the castle and Wilhelmshoehe. None other than a desultory effort had yet been made to cover about 750 yards remaining between [484] Roesslershof and the Weisweiler-Langerwehe highway.31

In response to Colonel Maness' appeal for reinforcement before attacking the Frenzerburg, the 47th Infantry provided Company K, a unit seriously depleted but closer at hand than any other. The regimental commander, Colonel Smythe, also did something about the threat of counterattack from Langerwehe by sending another infantry battalion early on 26 November toward Langerwehe to occupy a rough-surfaced hill only 800 yards short of the town. Colonel Smythe hardly could have anticipated how handsomly his perspicacity in sending a battalion to this hill was to be repaid. Task Force Richardson's plan of attack against the Frenzerburg on 26 November involved two simultaneous thrusts. Infantrymen mounted on tanks were to hit the castle from the south, while the infantry Company K was moving generally eastward alongside the Aachen-Juelich railroad. Hardly had the tanks and infantry reached open, cultivated fields south of the castle when German fire from positions a mile to the east near the village of Luchem knocked out two of the tanks. Scattering quickly, the infantry miraculously escaped injury, but German fire continued in such intensity that Colonel Richardson ordered the composite force to fall back. For all practical purposes, this marked dissolution of Task Force Richardson. The armor assumed a role of long-range fire support, while the full burden of the attack fell upon Colonel Maness' 2d Battalion, 47th Infantry, and Company K. When the Germans spotted the men of Company K sneaking along the Aachen-Juelich railroad, they smothered them with shelling. "It was the heaviest mortar and artillery fire since El Guettar," said 1st Lt. William L. McWaters, the company commander and a veteran of North Africa. Having started his attack with but eighty men, McWaters could ill afford the twenty he lost in this shelling. To the east Lieutenant McWaters could see the towers of the Frenzerburg rising behind tall trees as if the castle stood in the middle of a wood. Wary of turning back over the open route he already had traversed, McWaters saw the concealment of the wood as his only hope. Once among the trees, however, he discovered with chagrin that the wood was no more than a copse. The castle stood full in the open, 300 yards beyond the last trees. Down to sixty men, Lieutenant McWaters hesitated before crossing this open ground to the castle. Yet only a moment's reflection was enough to remind him that his route of withdrawal was even more exposed and that the copse would be a hard place to hold once the Germans discovered his presence. He would attack. His radio destroyed in the earlier shelling, McWaters had no way to solicit supporting fire from other than his own machine guns. These he set up at the edge of the trees to form a base of fire. As the machine guns began to chatter, his riflemen dashed for the castle. They made it. Not to the castle itself but to an open rectangle of outbuildings enclosing a courtyard in front of the entrance. One glance was enough to reveal that getting into the castle was [485] THE FRENZERBURG another proposition altogether. Of modest proportions as medieval castles go, Frenzerburg was nonetheless a formidable bastion to an unsupported infantry force reduced now to some half a hundred men. Denied on all sides by a water-filled moat twenty feet wide, the castle was accessible only by means of a drawbridge guarded by a gatehouse tower built of heavy stone. Although the drawbridge was down, a heavy oak gate blocked passage. A stone wall no more than waist high, bordering the moat near the drawbridge, offered the only protection to a move against the entrance. A lone bazookaman, Pfc. Carl V. Sheridan, dashed from the outbuildings toward the wall. Covered by two riflemen who pumped fire into windows of the gatehouse tower, Sheridan worked his way slowly toward the drawbridge. Unable to fire upon Sheridan because of the wall and the covering fire, Germans in the gatehouse tossed hand grenades from the windows. Somehow they missed. From the corner of the wall on the very threshold of the drawbridge, Sheridan loaded his bazooka, fired at the oak gate, calmly reloaded, and fired again. The heavy gate splintered but did not collapse. Sheridan had one rocket left. Again he loaded the awkward weapon. Ignoring grenades and rifle fire that popped about him, he took careful aim at the hinges of the gate and fired jumping to his feet, he brandished his bazooka, called to the men in the outbuildings behind him to "Come on, let's get 'em!" and charged. [486] The Germans cut him down a few feet from the gate.32

Lieutenant McWaters had no time to capitalize on Private Sheridan's feat before the Germans counterattacked from the gatehouse. They overran a squad in one end of the rectangle of outbuildings, captured the squad, and rescued about forty Germans Company K earlier had captured. In the face of this display of force, Lieutenant McWaters became acutely conscious of his plight. He sent a volunteer, Sgt. Linus Vanderheid, in quest of help. Sergeant Vanderheid had not far to go, for the 2d Battalion commander, Colonel Maness, had traced the route of Company K with four tanks and two rifle companies. This force already had reached the copse. Pointing up the anachronism of this twentieth century fight against a fifteenth century bastion, the tanks blasted the walls of the castle from the edge of the trees. As darkness came, Colonel Maness pushed his tanks and infantry across the open ground. Two tanks bogged down, an antitank gun in the castle set fire to another, and the one remaining blundered into the water-filled moat. Deprived of close support, Colonel Maness made no effort to assault the castle that night. Three hours before daylight the next morning, 27 November, the Germans counterattacked. About sixty paratroopers from the 3d Parachute Division, supported by six assault guns, struck the outbuildings. The Americans kept most of the assault guns at a respectable distance with artillery fire and bazookas, but one broke through into the courtyard. Churning back and forth, the German vehicle systematically shot up the landscape. The outbuildings began to burn. Somehow a section of the castle caught fire. Only as daylight approached did bazookas and hand grenades force the assault gun to retire. The paratroopers also fell back. All through the rest of 27 November American and German riflemen exchanged shots between the outbuildings and the castle, but not until early the next day did any break appear. During the night Colonel Maness brought up three tank destroyers. After the gunners had pummeled the gatehouse with 90-mm. projectiles for several hours, the infantry moved in. The assault itself was an anticlimax. As a final anomaly in this battle, the Germans had slipped away through an underground passage. The presence of sixty German paratroopers in the counterattack at the Frenzerburg marked the first major change in the line-up opposite the VII Corps since the early introduction (18 November) of the 47th Volks Grenadier Division. That no other help had been accorded this part of General Koechling's LXXXI Corps was attributable to the jealous hoarding of the admittedly limited reserves for the Ardennes counteroffensive and to continued German belief that the biggest threat was farther north opposite the Ninth U.S. Army. Indeed, the southern wing of the LXXXI Corps had even provided one small reinforcement for the northern front when on 21 November Kampfgruppe Bayer, which had fought at Hamich, was relieved from attachment to the 47th Division and sent north. Only [487] in artillery had there been any help provided; early on 22 November the partially motorized 403d Volks Artillery Corps had been committed between Dueren and Juelich.33

The presence of the 3d Parachute Division stemmed indirectly from another request made on 22 November for at least one division from the Fuehrer Reserve. While turning down the request flatly, OKW sugared the pill with word that the 3d Parachute Division soon would be shifted from the relatively inactive Holland front. Two days later, when confirming this move, OKW insisted that the parachute division must relieve at least one and preferably two divisions which might be refitted for the Ardennes.34 One division or two made little difference to the LXXXI Corps, so depleted were its units. The 12th Volks Grenadier Division, which had been fighting continuously since mid-September and which recently had been opposing the 104th U.S. Division and the 47th Infantry, finally was finished as a fighting force. The 27th Regiment, for example, had but 120 combat effectives left; another regiment, but 60. After eight days of combat, the "new" 47th Division also had been virtually wiped out. The 104th Regiment had about 215 combat effectives left; the 103d Regiment, 60; and the 115th Regiment, 36.35 On 24 November Fifteenth Army (Gruppe von Manteuffel), the army headquarters superior to the LXXXI Corps, had directed that these two divisions be formed into a single Kampfgruppe under General Engel, commander of the 12th Division. This was the unit, designated Gruppe Engel, which the 3d Parachute Division eventually was to relieve.36 Submergence in a Kampfgruppe was an unhappy fate for a division which had acquitted itself as well as had the 47th. Having walked into a body blow at the start of the November offensive, this division had fought back by throwing every available man into the front lines—headquarters clerks, artillerymen, green replacements, engineers, even veterinarians. Flagging morale and steadily decreasing resolution could have been expected under these circumstances, but somehow the 47th Division had escaped these viruses. The 1st U.S. Division later was to call it "the most suicidally stubborn unit this Division has encountered . . . on the Continent."37 Composed for the most part of boys aged sixteen to nineteen, steeped in Nazi ideology but untested in combat, the 3d Parachute Division began to move into the line the night Of 26 November. The division inherited a front about five miles long extending from Merode northward almost to the boundary between the First and Ninth U.S. Armies.38 As the German commanders soon were to discover, they had waited a day or so too long to act. Staging a relief under fire is risky business even with veteran [488] units. About the only claim the 3d Parachute Division had to experience was the name of the division, but an honorific is hardly a substitute for experience.

The first of the young paratroopers to run into trouble were those scheduled to counterattack at the Frenzerburg. These included a company each of reconnaissance, engineer, and antitank troops attached temporarily to Gruppe Engel and reinforced by assault guns of the newly arrived 667th Assault Gun Brigade.39 The base for the attack was to be the hill along the Langerwehe-Weisweller highway 800 yards west of Langerwehe which a battalion of the 47th Infantry had occupied in order to protect the attack on the castle. No one had told the paratroopers of the 47th Infantry's presence. As the Germans approached the hill, the Americans cut them down almost without effort. The German commander could reassemble only sixty men for the counterattack at the castle. In the meantime, a battalion of paratroopers moved west from Langerwehe to occupy positions at a settlement named Gut Merberich, south of the Weisweiler-Langerwehe highway. Presumably this battalion was to thwart what looked like an impending attack by the 16th Infantry designed to assist a final drive by the 18th Infantry on Langerwehe. No sooner had these paratroopers reached Gut Merberich just after dawn on 27 November when artillery fire began to fall, a prelude to the 16th Infantry's attack. The Germans dived for the cellars. They were still there a few minutes later when the 16th Infantry moved in. This was a prime example of what some of the few experienced noncommissioned officers in the parachute division meant when they said that under artillery fire, "the iron in the hearts of these kids turned to lead in their pants."40 To see two fresh battalions meet a fate like this must have convinced the Germans that they had a new enemy called Coincidence. This view must have been underscored an hour or so later on 27 November when the 18th Infantry renewed its attempt to take Hill 203, which for more than three days had stymied an advance into Langerwehe. Relinquishing the crest of Hill 203, survivors of the 47th Division's 104th Regiment still clung to another position on the reverse slope. To strengthen the new position and then retake the hill, the 3d Parachute Division sent a battalion of the 9th Parachute Regiment. The young paratroopers arrived just in time to catch the preparation fires of a renewal of the 18th Infantry's attack. Like those at Gut Merberich, these Germans had no taste for shellfire. They surrendered in bunches. With Hill 203 out of the way, the industrial town of Langerwehe, gateway to the Roer plain, lay unshielded. Though the paratroopers and what was left of the 47th Division fought persistently to soften the blow, the 18th Infantry and a battalion of the 16th Infantry had swept the last Germans from demolished buildings and cellars by nightfall of 28 November. At the same time the 26th Infantry was sending a battalion into the neighboring town of Juengersdorf. Despite counterattacks by the 5th Parachute [489] Regiment, Juengersdorf too was secure by nightfall on 28 November. On this ignominious note, Gruppe Engel was officially relieved from the front and started rearward for refitting.41

Up to this point the debut of the 3d Parachute Division had been something short of spectacular. In only two more instances were the paratroopers to have an opportunity to make amends. One of these came five days later at Luchem, a village north of Langerwehe which the VII Corps commander, General Collins, ordered the 1st Division to seize in order to form a straight line between Langerwehe and objectives of the 104th Division.42 In a deft maneuver, a battalion of the 16th Infantry slipped into the village before dawn without artillery preparation, and at daylight tanks and tank destroyers raced forward to assist the mop-up. The paratroopers hadn't a chance.43 In the other instance, location of the objective was not so propitious for a swift, unsupported infantry attack. The objective was Merode, a village at the eastern edge of the Huertgen Forest southeast of Juengersdorf. At Merode the young German paratroopers had a chance to discover that war can be an exhilarating experience—when you win. To the 26th Infantry, Merode was no ordinary objective. It was a promise of no more Huertgen Forest. To fulfill that promise, the 26th Infantry had but one battalion, already seriously weakened by thirteen brutal days in the forest. Another battalion was in Juengersdorf. The third had to hold the regiment's right flank in the woods because the adjacent 4th Division had not reached the eastern edge of the forest. Merode lies on a slope slanting downward from the eastern woods line. Although numerous roads serve the village from the Roer plain, only a narrow cart track leads eastward from the forest. Astride this narrow trail across 300 yards of open ground the 26th Infantry had to move. Behind a sharp artillery preparation, the attacking battalion commander, Colonel Daniel, sent two companies toward Merode shortly before noon on 29 November. Despite stubborn resistance from a battalion of the 5th Parachute Regiment in a line of strongpoints along the western edge of the village, Colonel Daniel's men by late afternoon had gained the first houses. Yet no one believed for a moment that the Germans were ready to relinquish the village. Employing numbers of pieces that the 1st Division G-2 estimated to be equal to those of the Americans, German artillery wreaked particular havoc. Despite several strikes by tactical aircraft and several counterbattery TOT's by 1st Division artillery, the German pieces barked as full-throated and deadly as ever. [490] The minute the riflemen gained the first houses, Colonel Daniel ordered a platoon of tanks to join them. Two got through, although one was knocked out almost immediately after gaining the village. Commanders of the other two tanks paused at the woods line, noted the "sharpness" of the enemy's shellfire, and directed their drivers to turn back.44 As they backed up, a shell struck a track of the lead tank. The tank overturned. Because of deep cuts, high fills, and dense, stalwart trees on either side of the narrow trail, no vehicle could get into Merode past the damaged tank.